Abstract

The extra sex combs (ESC) and Enhancer of zeste [E(Z)] proteins, members of the Polycomb group (PcG) of transcriptional repressors, interact directly and are coassociated in fly embryos. We report that these two proteins are components of a 600-kDa complex in embryos. Using gel filtration and affinity chromatography, we show that this complex is biochemically distinct from previously described complexes containing the PcG proteins Polyhomeotic, Polycomb, and Sex comb on midleg. In addition, we present evidence that ESC is phosphorylated in vivo and that this modified ESC is preferentially associated in the complex with E(Z). Modified ESC accumulates between 2 and 6 h of embryogenesis, which is the developmental time when esc function is first required. We find that mutations in E(z) reduce the ratio of modified to unmodified ESC in vivo. We have also generated germ line transformants that express ESC proteins bearing site-directed mutations that disrupt ESC-E(Z) binding in vitro. These mutant ESC proteins fail to provide esc function, show reduced levels of modification in vivo, and are still assembled into complexes. Taken together, these results suggest that ESC phosphorylation normally occurs after assembly into ESC-E(Z) complexes and that it contributes to the function or regulation of these complexes. We discuss how biochemically separable ESC-E(Z) and PC-PH complexes might work together to provide PcG repression.

The Drosophila homeotic proteins encoded by the Antennapedia and bithorax complexes are transcription factors required for anterior-posterior (A-P) body patterning (30, 36). These proteins are each expressed in spatially restricted regions along the A-P axis that correspond to their domains of developmental function (7, 8, 29, 67). The expression of homeotic proteins is controlled by two sets of repressors: the gap proteins, such as hunchback and Krüppel, act early in embryogenesis to set the limits of homeotic gene expression (46, 52, 53, 68), and the Polycomb group (PcG) proteins maintain homeotic gene repression throughout the remainder of development (for reviews, see references 45 and 54). In PcG mutants, homeotic genes are expressed outside of their normal A-P domains (39, 56, 59).

Approximately 15 PcG genes have been identified. Several lines of evidence indicate that this large set of repressors works together in multimeric protein complexes. The majority of the PcG proteins that have been cloned and characterized contain conserved domains that function in protein-protein interactions (2, 5, 12, 22, 28, 37, 42, 48, 55). Multiple pairwise interactions between different PcG members have been described for both Drosophila and mammalian PcG proteins (1, 14, 21, 23, 26, 35, 43, 50, 62, 65). Moreover, a PcG complex estimated at 2 MDa in size (17), which contains the Polycomb (PC), polyhomeotic (PH), and Posterior sex combs (PSC) proteins, has been characterized from Drosophila (35, 51, 61). A similar complex has also been identified in mammals (1, 21, 23).

Although a PC-PH-PSC complex is likely to be a key component in homeotic gene repression, several lines of evidence indicate that the PcG proteins do not function as members of a single large complex. First, the phenotypes of different PcG mutants are distinct; for example, ph mutants show an epidermal defect not seen with other PcG mutants (16). Second, the PcG proteins colocalize at numerous loci on polytene chromosomes but their distributions are not identical. In particular, the PC, PH, and Polycomblike distributions completely overlap whereas PSC and Additional sex combs are also found at distinct chromosomal sites (12, 17, 37, 38, 47, 57). Finally, immunoprecipitation assays on in vivo cross-linked chromatin show differential distributions of PC, PH, and PSC on regulatory sequences of the invected gene (61). These observations suggest that there is division of labor among the PcG proteins and that they function in multiple, distinct complexes.

PcG repression begins at about 3 to 4 h of embryogenesis and continues throughout the subsequent embryonic, larval, and pupal stages. Consistent with this, most of the PcG proteins are required and expressed continuously during these stages. The PcG member extra sex combs (esc) is distinct, however, in that its function is most critical during early embryogenesis (55, 60) and that esc mRNA is expressed primarily during early embryonic stages (18, 48, 55). The early requirement for esc function has led to the hypothesis that it may play a role in the molecular transition between gap protein and PcG protein repression (22, 48, 55).

The majority of the ESC protein is composed of seven WD repeats, a motif involved in protein-protein interactions (22, 48, 55). Homology modeling to another WD repeat protein, the G-protein β subunit, indicates that ESC folds into a circular structure known as a β-propeller (40, 66). The β-propeller acts as a scaffold that displays variable loops on the protein surface for interactions with other proteins. The predicted ESC β-propeller contains two large surface loops that are highly conserved in evolution (40). Clustered alanine substitutions introduced into these loops disrupt esc function in transient-rescue experiments (40), indicating that these loops are important for esc function in vivo.

The ESC protein binds directly to another PcG protein, Enhancer of zeste [E(Z)] (26, 62). The ESC interaction domain in E(Z) has been mapped to an N-terminal 33-amino-acid region. In addition, mutations in the ESC surface loops that impair function in vivo also disrupt ESC-E(Z) interactions in vitro (26). ESC-E(Z) association in vivo is demonstrated by the coimmunoprecipitation of the proteins from embryo extracts (26, 62) and their colocalization on polytene chromosomes (62). Taken together, these results establish a molecular partnership between ESC and E(Z) and suggest that this relationship is important for homeotic gene repression.

The ESC-E(Z) partnership shows striking evolutionary conservation. Mouse homologs of ESC and E(Z), i.e., EED and EZH1 or EZH2, respectively, interact directly and coimmunoprecipitate from cell extracts (14, 26, 50, 65). In addition, Caenorhabditis elegans homologs of ESC and E(Z) have been identified; these homologs are encoded by the maternal effect sterile genes mes-6 and mes-2 (25, 33). The spatial distributions of the MES-6 and MES-2 proteins are identical, and mutations in either gene disrupt the nuclear accumulation of the other protein (25, 33). These results are consistent with MES-6/MES-2 physical association. Furthermore, these MES proteins function as transcriptional repressors during germ line development (31). Although this reflects a distinct developmental role from the somatic function of ESC and E(Z) in flies, the partnership between the two proteins as repressors at the level of chromatin appears to be conserved.

Intriguingly, homologs of the other PcG proteins have not been identified in database searches of the C. elegans genome (33). This implies that ESC and E(Z) may function together as gene repressors through a mechanism independent of other PcG proteins. If this is the case, ESC-E(Z) complexes in Drosophila may be biochemically distinct from complexes containing other PcG proteins. Although PC-PH-PSC complexes in fly embryo extracts have been described (17, 51, 61), little is known about the nature of ESC-E(Z) complexes. To address possible biochemical separability and to begin analysis of ESC-E(Z) molecular function, we have examined ESC-E(Z) complexes from embryonic nuclear extracts. We report that ESC and E(Z) coassociate in stable complexes of about 600 kDa and that these complexes are distinct from those containing the PcG protein PH. In addition, we found that ESC is covalently modified in vivo. Multiple lines of evidence from biochemical, mutational, and developmental expression studies correlate ESC modification with function in vivo. We present evidence that this posttranslational modification is phosphorylation and that it occurs after incorporation of ESC into ESC-E(Z) protein complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Developmental Western blot analysis.

Staged embryos, larvae, and pupae were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then pulverized using a mortar and pestle. An equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM ammonium molybdate was added, and the extract was sonicated for 30 s, heated at 95°C for 5 min, and centrifuged for 10 min to remove particulate material. Relative protein concentrations were determined by Coomassie blue staining of proteins after SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Immunodetection of HA-ESC protein was performed with mouse monoclonal HA.11 antibody (1:1,000) (Covance) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:20,000) (Jackson Laboratories). Immunodetection of E(Z) protein was performed with rabbit polyclonal anti-E(Z) antibody (1:1,000) (6) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000) (Bio-Rad). Signals were developed with an ECL detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Phosphatase assays.

Total embryonic extracts (see Fig. 4A) were prepared from 0- to 24-h HA-esc transgenic embryos as described previously (15). Nuclear extracts (see Fig. 4B) were also prepared from 0- to 24-h HA-esc transgenic embryos as follows. Embryos were homogenized in nuclear isolation buffer (37.5 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 0.05 mM spermine, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 7.4], 20 mM KCl, 0.5% thiodiglycol, 0.05% Empigen BB, 0.1 mM PMSF, 2 μg of aprotinin per ml) using a Dounce homogenizer and A and B pestles. Nuclei were filtered through Miracloth (Calbiochem) and pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm in a JS13.1 rotor (Beckman). The nuclei were washed twice in nuclear isolation buffer, then resuspended in 1 ml of nuclear extraction buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 360 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 4 μg of aprotinin per ml, 0.2 mM PMSF, 5 μg each of leupeptin, antipain, pepstatin A, and chymostatin per ml) per 5 g of embryos, and incubated for 30 min at 4°C with gentle agitation. Extracts were centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 1 h in a Beckman SW60 rotor. The supernatant was then flash-frozen and stored at −70°C.

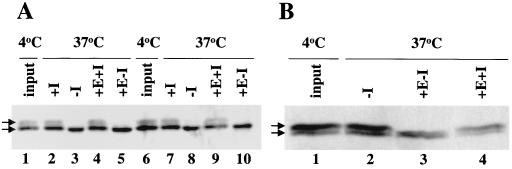

FIG. 4.

Tests for ESC phosphorylation. Wild-type HA-esc extracts were treated with phosphatases and detected by immunoblotting. I, phosphatase inhibitors; E, enzyme. The arrows indicate the two ESC forms. (A) Phosphatase treatments of total embryonic extracts. The enzyme used for lanes 4 and 5 was potato acid phosphatase, and the enzyme used for lanes 9 and 10 was calf alkaline phosphatase. Lanes 1 and 6 show untreated extracts. (B) Calf alkaline phosphatase treatments of nuclear extracts.

Samples were treated with either 1 U of calf alkaline phosphatase (Roche) per μl or with 2 U of potato acid phosphatase (Sigma) per μl. Alkaline phosphatase assays were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5)–0.1 mM EDTA–1 mM PMSF–2 μg of aprotinin per ml–1 μg of leupeptin per ml; acid phosphatase assays were performed in 10 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) (pH 6.1)–2 mM MgCl2–0.05% Triton X-100–100 mM NaCl–1 mM PMSF–2 μg of aprotinin per ml–1 μg of leupeptin per ml. Samples were treated at 37°C for 40 min in the presence or absence of the phosphatase inhibitors NaF (10 mM) and ammonium molybdate (1 mM).

Generation and purification of PH antibodies.

A 0.8-kb XhoI-StuI fragment encoding amino acids 86 to 340 of the proximal PH protein was inserted into pGEX-BgRP3i (26). The resulting glutathione S-transferase (GST)-PH fusion protein was purified on glutathione-agarose beads, subjected to preparative SDS-PAGE, and used as an immunogen in rabbits. Crude sera that tested positive for immunogen reactivity were affinity purified against the GST-PH immunogen coupled to the Actigel ALD affinity chromatography resin (Sterogene Bioseparations). Antibodies were bound and eluted from the Actigel column as specified by the manufacturer. Specificity of the antibody for PH was demonstrated by (i) detection of bands at the predicted molecular mass (170 kDa) on Western blots of embryo extracts, (ii) depletion experiments that show loss of this immunoreactivity on Western blots after preincubation of the antibody with the PH immunogen, and (iii) immunostaining of polytene chromosomes at sites previously shown to accumulate PH (12).

Gel filtration analysis.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from 0- to 24-h HA-esc transgenic embryos as described above, with the addition of phosphatase inhibitors. The extracts were fractionated using a 24-ml Superose 6 gel filtration column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) on a BioLogic chromatography system (Bio-Rad). Molecular mass standards (thyroglobulin [670 kDa], apoferritin [450 kDa], catalase [240 kDa], and bovine serum albumin [68 kDa]) were used to calibrate the column. Fractions were eluted in column buffer (45 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 360 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ammonium molybdate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, 5 μg each of leupeptin, antipain, pepstatin A, and chymostatin per ml), and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. For the experiment in Fig. 2, top, 150 μl of each fraction was precipitated with 8 volumes of acetone, resuspended in SDS sample buffer, and separated by SDS-PAGE. For the experiment in Fig. 2, bottom, 20 μl of each fraction was run on an SDS-containing gel. For the experiment shown in Fig. 8, 100 μl of each fraction was precipitated with 8 volumes of acetone, resuspended in SDS sample buffer, and separated by SDS-PAGE. The HA-ESC and E(Z) proteins were detected on Western blots as described above. PH protein was detected using rabbit polyclonal anti-PH antibody (1:1,000) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:10,000) (Bio-Rad).

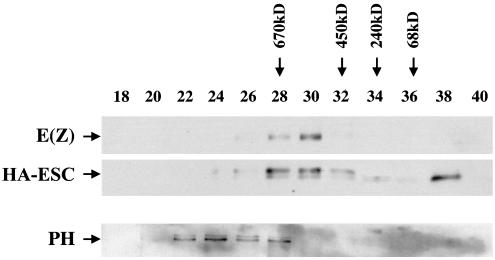

FIG. 2.

Gel filtration analysis of embryo extracts from HA-esc transformants. Nuclear extracts were fractionated by Superose 6 chromatography. Fraction numbers are indicated at the top. The elution positions of molecular mass standards are indicated by arrows. (Top) Detection of HA-ESC and E(Z) by immunoblotting. (Bottom) Detection of PH by immunoblotting.

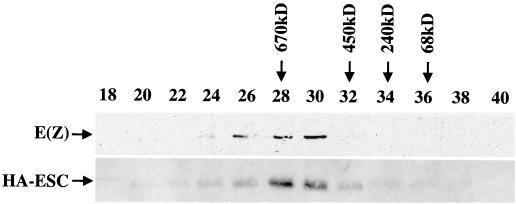

FIG. 8.

Gel filtration analysis of mutant HA-ESC. Nuclear extract from embryos expressing HA-ESC with the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA mutation was fractionated by Superose 6 chromatography. Fraction numbers are indicated at the top. Elution positions of molecular mass standards are indicated by arrows. HA-ESC and E(Z) proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-E(Z) antibodies, respectively.

Immunoaffinity chromatography.

Nuclear extracts (15 mg) prepared from 0- to 24-h HA-esc transgenic embryos were incubated with anti-HA.11 resin (100 μl; Babco) at 4°C for 16 h with rotation. The resin was then packed into a column and washed at room temperature with 50 column volumes of nuclear extraction buffer (described above). Bound proteins were eluted with five 100-μl aliquots of nuclear extraction buffer plus 1 mg of HA peptide (YPYDVPDYA; Babco) per ml for 45 min each. Aliquots of the nuclear extract, unbound flowthrough, final column wash, and peptide-eluted material (HA) were analyzed on immunoblots. HA-ESC, E(Z), and PH were detected as described above. Sex comb on midleg (SCM) and pleiohomeotic (PHO) were detected using rabbit affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies (3, 19) at 1:2,000 and 1:750, respectively.

Generation and testing of mutant HA-esc germ line transformants.

The site-directed esc mutations have been described previously (40). A 0.6-kb genomic EcoRI fragment containing each mutation was isolated and used to replace the wild-type EcoRI fragment in cep420, which is a germ line transformation construct that contains an influenza virus HA epitope-tagged genomic copy of esc (26). The resulting constructs were identical to cep420 except for the mutations. Germ line transformants were generated in a y Df(1)w67c23 genetic background. For each mutant construct, three independent transformants with HA-esc gene inserts on the X or third chromosome were tested for rescue of esc function as described previously (55). This standard rescue assay generates embryos from females bearing a single copy of the transgene to be tested. One transformant line for each construct was also tested in assays with females bearing two copies of the transgene. None of the mutant lines tested rescued esc embryonic lethality in either case.

To examine transgene expression levels, 6- to 12-h-old embryos were collected from three independent lines for each of the wild-type and three mutant constructs. The embryos were dechorionated in 50% bleach and homogenized in an equal volume of SDS sample buffer with 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 mM ammonium molybdate, and 10 mM sodium fluoride. The samples were sonicated for 30 s, heated at 95°C for 5 min, and then centrifuged for 10 min to remove particulate material. Western blots were performed as described above. Levels of wild-type and mutant proteins were quantitated using a Bio-Rad GS-700 imaging densitometer and were analyzed with Molecular Analyst v.2.1 software (Bio-Rad). Data were obtained from at least four independent trials for each of the three mutant lines measured.

Analysis of HA-ESC and E(Z) levels in E(z) mutant embryos.

Transformant lines homozygous for an HA-esc transgene on the X chromosome and either E(z)28 or E(z)61 on the third chromosome were generated. Embryos that were 12 to 24 h old were collected from these HA-esc; E(z) lines reared at 20°C, and embryos that were 4 to 8 h old were collected from the lines reared at 29°C. The embryos were aged for different times at the permissive and restrictive temperatures to adjust for different rates of development under these conditions. Total-embryo extracts were prepared and immunoblots were performed as described above.

RESULTS

Expression of ESC during development.

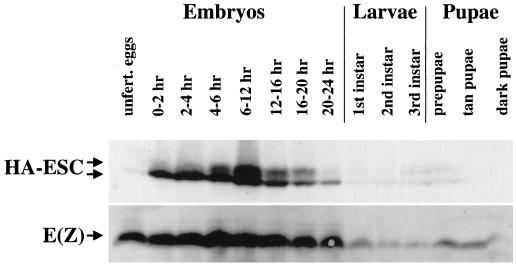

Previous experiments have suggested that esc function is required most critically early in development (55, 60). To examine the timing of ESC protein expression during development, we used transformants that express an epitope-tagged version of ESC. These transformants produce HA-tagged ESC from a genomic construct under control of the normal genomic promoter (26). This HA-ESC protein provides full esc function in vivo (26). Total-protein extracts were prepared from HA-esc transformants at different developmental stages, and relative levels of HA-ESC were assessed on immunoblots. Figure 1 shows that HA-ESC is expressed most abundantly during embryogenesis, with peak levels at about 6 to 12 h of development (top panel). This is consistent with previous studies showing that esc mRNA is most abundant during early embryogenesis (18, 48, 55). The level of HA-ESC is severely reduced by the end of embryogenesis and remains very low during early larval stages. HA-ESC is also detected in a second peak during the third-instar larval and early pupal stages, albeit at much lower levels than in embryos. Although esc function is not required for viability at this stage, genetic studies have shown that this late expression of ESC reflects function in imaginal disc development (58, 63). HA-ESC is also present at very low levels in unfertilized eggs. Since levels of esc mRNA in ovaries and early embryos are similar (18, 55), this protein profile indicates that the bulk of maternal esc product is in the form of mRNA. In contrast to the ESC developmental profile, several other PcG proteins show more uniform expression during development (3, 11, 38).

FIG. 1.

Expression of ESC and E(Z) during development. Detection of HA-ESC and E(Z) proteins by immunoblotting of wild-type HA-esc extracts from the indicated embryonic, larval, and pupal stages. Approximately equal amounts of total protein were loaded per lane. The two ESC forms are indicated by arrows.

The bottom panel of Fig. 1 shows the developmental profile for the E(Z) protein, detected with an affinity-purified polyclonal anti-E(Z) antibody (6). The E(Z) profile is similar to that of HA-ESC, with the highest expression levels observed during embryogenesis and lower levels detected later in development. These results suggest that the most critical time for ESC-E(Z) functional partnership is during embryogenesis. During pupal stages, E(Z) levels rebound to a greater degree than do HA-ESC levels. This is consistent with a role for E(Z) in cell proliferation late in development (44), which apparently does not involve ESC.

Figure 1 also shows that HA-ESC is detected as a doublet at specific developmental stages. In contrast to the lower band, which is relatively constant during the first half of embryogenesis, the upper species increases in abundance between 2 and 6 h. This corresponds to the developmental time during which ESC is first required for homeotic gene repression (55, 56, 60). The upper species is also a major component of the HA-ESC detected in larval and pupal stages (Fig. 1). These results show that alternative forms of ESC are present in vivo. Since there is no evidence for alternative splicing of fly esc mRNA from Northern blot and cDNA analyses (18, 55), the alternative forms most likely result from posttranslational modification.

ESC-E(Z) complexes in fly embryo extracts.

To gain insight into the nature of ESC-E(Z) protein complexes in vivo, we fractionated nuclear extracts from 0- to 24-h-old HA-esc embryos by size exclusion chromatography on a Superose 6 column. The fractions were assayed for HA-ESC and E(Z) by immunoblotting (Fig. 2). We found that HA-ESC and E(Z) cofractionate in complexes of about 600 kDa (fractions 28 to 30). The coincidence of the HA-ESC and E(Z) peaks is consistent with the previously described in vivo association of the two proteins (26, 62) and implies a stable ESC-E(Z) association rather than a transient interaction. Furthermore, the lack of free E(Z) indicates that embryonic E(Z) exists primarily in the complexed form.

Figure 2 also shows that there is differential fractionation of the multiple forms of HA-ESC. We find that the upper species of the HA-ESC doublet is preferentially associated in the high-molecular-weight complex with E(Z), whereas the bulk of the lower HA-ESC species elutes in fractions corresponding to free ESC monomer (Fig. 2, compare fractions 28 and 30 to fraction 38). Thus, ESC modification correlates with its association in the 600-kDa complex, which is likely the molecular species that functions in gene repression.

The ESC-E(Z) complex is biochemically separable from other PcG complexes.

Multimeric complexes containing the PcG proteins PH and PC and 10 to 15 other protein components have been described previously (17, 51). The size of these PH-PC complexes was estimated at about 2 MDa (17). To investigate the biochemical relationship between PH-containing complexes and the ESC-E(Z) complex, we determined the elution profile of PH under the same gel filtration conditions used to identify the ESC-E(Z) complex. PH was detected on immunoblots using an affinity-purified polyclonal anti-PH antibody generated against an N-terminal portion of PH (see Materials and Methods). Figure 2, bottom, shows that PH is detected in a separate peak corresponding to complexes significantly larger than the ESC-E(Z) complex. This result indicates that the 600-kDa ESC-E(Z) complex and PH-containing complexes are biochemically distinct.

To further investigate the biochemical separability of PcG proteins, we used affinity chromatography to test for coenrichment of multiple PcG proteins with HA-ESC. Nuclear extract from 0- to 24-h HA-esc embryos was incubated with anti-HA antibodies covalently coupled to Sepharose beads. After binding, the affinity column was washed extensively and bound proteins were eluted under native conditions with HA peptide. Figure 3 shows immunoblot detection of PcG proteins in the starting material (nuclear extract samples) and in the peptide-eluted fractions (HA samples). HA-ESC and E(Z) are coenriched in this affinity chromatography test, consistent with their association in the 600-kDa complex. In contrast, PH is not coenriched, which agrees with its separability from ESC and E(Z) by gel filtration (Fig. 2).

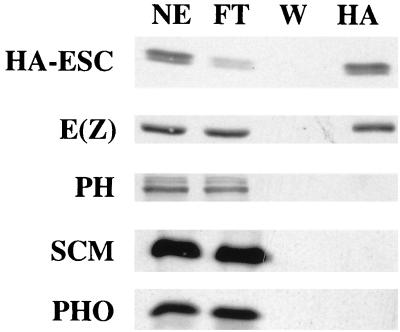

FIG. 3.

Tests for coenrichment of PcG proteins with HA-ESC by immunoaffinity chromatography. Immunoblots to detect the indicated PcG proteins are shown. NE, nuclear extract starting material; FT, flowthrough containing unbound material; W, final wash of affinity column; HA, material eluted with HA peptide. The HA lanes on the E(Z), PH, SCM, and PHO blots contain sixfold more material loaded than for the corresponding lane on the HA-ESC blot.

We also tested for coenrichment of two additional PcG proteins, SCM and PHO, using affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against these proteins (3, 19). A fraction of the SCM present in fly embryos copurifies with PRC1, a PH-PC-PSC complex (51). Consistent with SCM association in complexes distinct from ESC and E(Z), we found that SCM is not coenriched (Fig. 3). PHO is the sole fly PcG protein characterized to date that has sequence-specific DNA-binding activity (4). It has been hypothesized to play a role in recruiting PcG complexes to target DNA sites. The lack of PHO coenrichment (Fig. 3) suggests that, like PH and SCM, PHO is not a stable component of ESC-E(Z) complexes. Taken together, the gel filtration and affinity chromatography results show that members of the functionally related family of PcG repressors sort into distinct biochemical entities.

Evidence for ESC phosphorylation.

We reasoned that the posttranslational modification on ESC might be phosphorylation, especially since ESC is rich in serine and threonine residues. We therefore used phosphatase assays to test if HA-ESC is phosphorylated in embryo extracts. Total-protein extracts were prepared from 0- to 24-h-old HA-esc embryos, and the extracts were treated with either calf alkaline phosphatase or potato acid phosphatase (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 10). These treatments eliminate the slower-migrating ESC species seen in the input lanes. When the phosphatase inhibitors sodium fluoride and ammonium molybdate were included in the enzyme treatments, the loss of this upper species was prevented (lanes 4 and 9), suggesting that ESC is phosphorylated. We found that this band was similarly eliminated in samples incubated at 37°C without the addition of exogenous enzyme (lanes 3 and 8), which implies that whole-embryo extracts contain endogenous activities that can remove the ESC modification. Addition of phosphatase inhibitors also prevents the loss of the upper band under these conditions (lanes 2 and 7). Similarly, an endogenous phosphatase in fly embryo extracts that removes modifications from the transcription factor dorsal has been described previously (20).

To substantiate the results obtained with crude extracts, we sought conditions where conversion of HA-ESC to the faster-migrating species depends upon the addition of purified, exogenous phosphatase. To do this, we performed phosphatase assays on nuclear extracts prepared from 0- to 24-h-old HA-esc embryos. Figure 4B shows that the control sample incubated at 37°C without added phosphatase retains the slower-migrating HA-ESC species (lane 2). This indicates that the nuclear extract lacks the endogenous activity seen with total embryonic extracts (Fig. 4A). Treatment of the nuclear extract with exogenous calf alkaline phosphatase removes the slower-migrating species (Fig. 4B, lane 3), and addition of phosphatase inhibitors to the enzyme reaction mixture prevents the loss of this species (lane 4). These results provide evidence that ESC is phosphorylated in vivo and that this modification is present in the cellular compartment where ESC functions as a repressor.

The gel filtration data (Fig. 2) show that modified ESC is preferentially found in ESC-E(Z) complexes. Although the high-molecular-weight fractions (fractions 28 to 30) primarily contain the upper, modified HA-ESC species, these fractions also consistently contain detectable levels of the unmodified species. Since the gel filtration was performed in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors, we do not believe that this lower species is generated during fractionation. Taken together, these results are consistent with incorporation of unmodified ESC into ESC-E(Z) complexes followed by ESC phosphorylation upon complex assembly. If this is correct, the levels of modified ESC might depend upon the function of ESC binding partners and the ability of ESC to interact productively with these partners.

ESC modification is influenced by E(z) function.

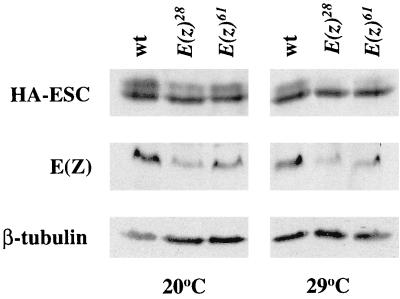

To test if ESC modification depends on its E(Z) partner, we examined ratios of modified to unmodified HA-ESC in embryos bearing loss-of-function E(z) mutations. Since the production of embryos with significant E(z) loss of function requires impairment of both the maternal and zygotic E(z)+ products, we used the E(z)28 and E(z)61 temperature-sensitive mutations (27, 44). E(z)28 and E(z)61 are missense changes in two different evolutionarily conserved E(Z) domains distinct from the ESC-binding domain (6, 26). For both alleles, homozygous mutants are viable at 20°C but are embryonic lethal with strong homeotic phenotypes at 29°C. In agreement with the phenotypes, the uniform A-P distribution of homeotic proteins in E(z)61 mutant embryos (56) shows that PcG regulation is severely disrupted.

Fly lines were constructed that are homozygous for either E(z)28 or E(z)61 and for an X-linked HA-esc transgene. Embryos were collected from these two E(z) mutant lines, and from the wild-type HA-esc control line, at permissive and restrictive temperatures. Figure 5 shows immunoblots to detect HA-ESC and E(Z) in extracts prepared from these embryos. At the permissive temperature, both mutant and wild-type extracts showed accumulation of modified ESC. However, at the restrictive temperature, the ratio of modified to unmodified ESC was substantially reduced in both E(z) mutants compared to wild-type. Overall levels of E(Z) also appeared reduced in the two mutants at restrictive temperature, consistent with the loss-of-function character of these alleles. Since the molecular roles of the mutated E(Z) domains are not known, it is not clear if the loss of function is due primarily to effects on E(Z) activity or on stability or both. In either case, these results show that levels of ESC modification depend on E(z) function.

FIG. 5.

Expression of HA-ESC and E(Z) in temperature-sensitive E(z) mutant embryos. Immunoblots to detect HA-ESC and E(Z) from embryos collected at permissive (20°C) and restrictive (29°C) temperatures are shown. Embryo genotypes: wt, wild-type; E(z)28 or E(z)61, homozygous for the indicated temperature-sensitive E(z) mutation. Blots were reprobed with antibodies to β-tubulin as a control for amounts of total protein loaded per lane.

Mutant ESC proteins show reduced levels of modification in vivo.

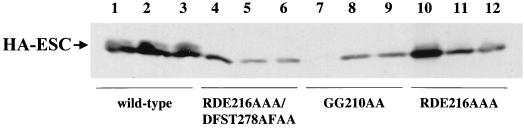

We have previously generated clustered alanine substitutions in highly conserved predicted surface loops of ESC (40). These mutant ESC proteins show reduced binding to E(Z) in vitro (26), and they fail to rescue the lethality of esc null embryos in a transient mRNA injection rescue assay (40). To further examine the effects of these mutations on ESC function and modification in vivo, we produced germ line transformants that express HA-tagged versions of the mutants RDE216AAA and GG210AA, as well as the double mutant RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA (40). These transformants contain transgene constructs that are identical to the wild-type, rescuing, HA-esc construct except for the mutations. None of these three mutant proteins provides esc function when expressed in stable germ line transformants, as demonstrated by their failure to rescue the lethality of esc null embryos (see Materials and Methods). We compared expression levels of these mutant HA-ESC proteins to that of wild-type HA-ESC in crude embryonic extracts. Three independent lines were tested for each of the wild-type and mutant constructs. All lines were homozygous for the respective transgenes and behaved genetically as lines with single transgene insertions. Figure 6 shows that the transgenic lines express different levels of HA-ESC depending on the line. The failure of these mutant proteins to provide esc function is not due simply to lowered overall expression levels, since several of the nonrescuing lines accumulate mutant HA-ESC at levels similar to those in the wild type. Mean expression levels (n ≥ 4) determined from densitometric analyses are 83, 54, and 126% of wild-type levels for the nonrescuing lines shown in Fig. 6, lanes 4, 9, and 10. Moreover, doubling the dosage of maternally provided mutant ESC in the standard rescue test (see Materials and Methods) did not alter the lack of rescue. The failure to rescue here also parallels results obtained in mRNA injection rescue experiments (40), where the amounts of in vitro-transcribed esc mRNA injected far exceed endogenous levels of the gene product.

FIG. 6.

Expression of mutant HA-ESC proteins. Immunoblot detection of wild-type (lanes 1 to 3) and the indicated mutant (lanes 4 to 12) HA-ESC proteins from 6- to 12-h total-embryo extracts is shown. Three independent lines were used for each transgene construct. All lines were homozygous for the transgene. Approximately equal amounts of total protein were loaded per lane.

Although not optimized to resolve the ESC forms, the blot in Fig. 6 suggests that levels of modified HA-ESC are specifically reduced in the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA and GG210AA mutants. Consequently, we examined this more precisely by testing a single line bearing each transgenic construct under gel conditions that improve the separation of the two ESC forms. Extracts were prepared from 6- to 12-h staged embryos, which contain peak levels of modified wild-type HA-ESC (Fig. 1). Figure 7A shows that the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA and GG210AA mutant lines accumulate the faster-migrating ESC species but that the relative amount of modified ESC is dramatically reduced. Thus, ESC mutant proteins with impaired E(Z) binding in vitro show reduced levels of modification in vivo.

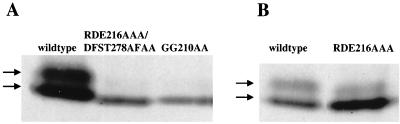

FIG. 7.

Effect of ESC surface loop mutations upon ESC modification. Immunoblot detection of wild-type and mutant HA-ESC proteins from 6- to 12-h embryo extracts is shown. Arrows indicate the two ESC forms. Mutants in panel A show severe loss of esc function in vivo, and the mutant in panel B shows moderate loss of function in vivo.

In contrast to the mutant results in Fig. 7A, the RDE216AAA mutant shows a more subtle reduction in the relative levels of modified to unmodified ESC (Fig. 7B). Intriguingly, the two ESC mutants with severe loss of the modified species behave as null mutants in the transient esc rescue assay whereas the mutant with more subtle reduction retains some residual activity (40). This correlation provides another link between esc function and modification in vivo.

Association of mutant ESC in complexes.

We wished to determine why the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA and GG210AA ESC mutants failed to function in vivo. We have identified two molecular defects; their direct binding to E(Z) in vitro is disrupted (26), and they fail to accumulate wild-type levels of modification (Fig. 7A). One explanation, given the E(Z) binding defect, is simply that these mutant ESC proteins are unable to assemble into the 600-kDa ESC-E(Z) complexes. To address this question, we prepared nuclear extracts from 0- to 24-h embryos homozygous for the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA mutant HA-esc transgene and fractionated the extracts on a Superose 6 column. Figure 8 shows that the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA protein associates in complexes with an apparent molecular mass similar to that of the complex containing wild-type ESC (compare fractions 28 and 30 in Fig. 8 to the same fractions in Fig. 2). Similarly, analysis of the GG210AA mutant protein shows that it also is present in complexes of about wild-type size (data not shown). It is possible that the resolution of these gel filtration experiments is insufficient to distinguish ESC complexes that contain or lack the 87-kDa E(Z) component. However, coimmunoprecipitation experiments performed on RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA mutant extract detect an association of E(Z) with the mutant ESC (data not shown). The simplest interpretation is that these mutant ESC proteins are incorporated into complexes that are rendered functionally defective. In addition, the combined results for in vitro binding and in vivo complex assembly suggest that contacts between ESC and other partner proteins besides E(Z) contribute to ESC association in the 600-kDa complex.

DISCUSSION

Expression and modification of ESC protein.

esc mRNA is expressed primarily during early development, with the highest levels being found before 4 h of embryogenesis (18, 55). This early expression has prompted the hypothesis that esc functions in the transition between initiation of homeotic gene repression by gap proteins, such as hunchback, and maintenance of this repression by PcG proteins (22, 48, 55). This transition occurs at about 4 h, when gap gene products decay. In this study we have shown that ESC protein is expressed at peak levels at 6 to 12 h (Fig. 1), after esc mRNA has decayed to low levels. In addition, ESC is detected until the end of embryogenesis. The presence of substantial levels of ESC in mid- to late-stage embryos suggests that ESC may play a greater role than simply in the transition between gap protein and PcG protein repression. In addition, a second peak of ESC protein is detected during larval and pupal stages, consistent with its nonessential function in imaginal discs (58, 63).

We show evidence that ESC protein is modified by phosphorylation in embryos and that the modified species accumulates at about 2 to 6 h, when esc function is first required (55, 60). In addition, site-directed ESC mutants that have impaired function in vivo accumulate reduced levels of modified ESC. Although reduced modification of the RDE216AAA DFST278AFAA mutant could result from removal of phosphorylated Ser or Thr residues, the GG210AA mutation does not affect commonly phosphorylated residues and causes a similar reduction in the level of phospho-ESC. Taken together, the data establish a correlation between ESC modification and function in vivo.

The predicted ESC structure (40) identifies two surface-accessible regions likely to contain the phosphorylation sites: the highly charged N terminus and the surface loops of the β-propeller. We have not mapped the ESC phosphorylation sites, which will first require purification of ESC from embryo extracts. However, we predict that ESC is serine/threonine phosphorylated, because many of the Ser and Thr residues are surface accessible. In particular, the N-terminal tail is very rich in Ser and Thr residues (35%), a feature which has been conserved in ESC during evolution (40, 49). A scan of the accessible ESC regions for consensus kinase recognition motifs identifies numerous possible modification sites and is therefore not particularly instructive.

An intriguing candidate for an ESC kinase is the female sterile homeotic [fs(1)h] gene product, which is closely related to a human nuclear kinase (13, 24) and is the only known kinase implicated in homeotic gene regulation. However, FS(1)H belongs to the trithorax group of proteins, which is involved in activation of homeotic genes (for a review, see reference 32). The fs(1)h mutant phenotype thus corresponds to homeotic gene loss-of-function. This suggests that FS(1)H is not the ESC kinase, since our results predict that mutations in the kinase would disrupt ESC function and cause ectopic expression of homeotic genes.

The ESC-E(Z) complex and molecular partnership.

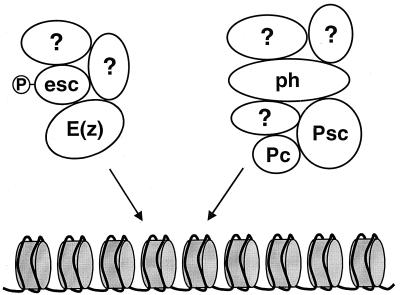

In vitro binding assays and coimmunoprecipitations have established that ESC and E(Z) are direct molecular partners (26, 62). Our gel filtration experiments (Fig. 2) show that this partnership reflects ESC-E(Z) association in a complex of about 600 kDa in embryo extracts. Given that the monomer molecular masses for ESC and E(Z) are 48 and 87 kDa, respectively, this size suggests that ESC and E(Z) do not bind as simple heterodimers in embryos but, rather, that they are components of a multimeric complex (Fig. 9). The low level of ESC protein in unfertilized eggs (Fig. 1) indicates that assembly of the ESC-E(Z) complex is a zygotic process.

FIG. 9.

Division of labor in the PcG. The model shows two biochemically separable PcG complexes with components based on this work and previous studies (17, 26, 35, 51, 61, 62). Members of each complex and established direct interactions between these members are indicated. Question marks indicate that there are likely additional components in these complexes to be identified. Arrows indicate that the complexes work through a common regulatory target in chromatin.

Our gel filtration experiments also show that modified ESC is found preferentially in the ESC-E(Z) complex while unmodified ESC behaves predominantly as unassociated monomer. Interestingly, mutant ESC proteins with reduced levels of modification also associate in complexes with the same apparent molecular mass as the wild-type complex. This suggests that ESC modification is not required for its stable association in complexes. Consistent with this idea, we reproducibly detected low levels of unmodified wild-type ESC in the 600-kDa complex (Fig. 2). Based on these data, we favor a model in which ESC modification contributes to function rather than to assembly of the complex. The finding that E(Z) function is required for wild-type levels of ESC modification (Fig. 5) further suggests that this modification occurs after ESC has complexed with its partners.

The mutant ESC proteins described here show reduced ESC-E(Z) binding in vitro (26). Therefore, we were surprised to find that these mutants assemble into complexes of apparently wild-type size. We suggest that ESC may bind to multiple protein partners in the ESC-E(Z) complex (Fig. 9), such that specific disruption of ESC-E(Z) interaction still allows complex assembly. In support of this idea, β-propeller proteins have been shown to make simultaneous contacts with multiple partners (66). Another possibility is that mutant ESC is brought into complexes through homotypic interactions with endogenous wild-type ESC. This seems unlikely, however, since in vitro binding assays do not detect self-association of ESC (A. Peterson and J. Simon, unpublished data). Moreover, the majority of ESC is occupied by the β-propeller domain, and β-propellers do not typically function as homodimers.

If the ESC mutants assemble into 600-kDa complexes, why do they fail to function in vivo? One possibility is that disruption of direct ESC-E(Z) contact renders the complex unable to adopt an active conformation. Another possibility is that E(Z) is required to produce or maintain ESC phosphorylation, which could be key for function of the complex. This is an attractive model, since E(Z) contains a motif known as the SET domain (28), which has been shown to bind proteins that act as phosphatase inhibitors (10).

Division of labor in the PcG.

The PcG proteins PC and PH are associated in a complex estimated to be 2 MDa (17). In addition, PC and PH coimmunoprecipitate and interact with another PcG protein, PSC (35, 61). Here, we have shown that the ESC-E(Z) complex is biochemically distinct from complexes containing PH (Fig. 2 and 3). In agreement with this, a PH-PC-PSC complex recently purified from fly embryos does not contain E(Z) (51). Taken together, these results support a model (Fig. 9) in which there are at least two distinct PcG complexes in vivo, one containing ESC and E(Z) and the other containing PH, PC, and PSC. Consistent with this idea, the mammalian ESC and E(Z) homologs, EED and EZH2, fail to coimmunoprecipitate with the mammalian PH, PSC, and PC homologs (50, 64, 65). In addition, EED and EZH2 do not colocalize with mammalian PH, PSC, and PC within nuclei of osteosarcoma cells (50, 65). Furthermore, the patterns of pairwise interactions among Drosophila PcG proteins are reiterated among their mammalian counterparts (1, 14, 21, 23, 26, 35, 43, 50, 62, 65), which suggests that this division of labor in the PcG (Fig. 9) has been conserved in evolution.

Although the existence of at least two different PcG complexes has been established, the complete spectrum of PcG protein interactions has not yet been elucidated. There appears to be further division among PH-PC-PSC complexes, which have different compositions at different target genes (61). In addition, multiple complexes containing the mammalian PH, PC, and PSC proteins have been detected (23). Moreover, there are additional PcG proteins, such as ASX, PCL, and PHO, whose in vivo associations have yet to be described. Some of these proteins may correspond to as yet unidentified components of ESC-E(Z) or PH-PC-PSC complexes (Fig. 9), or they may sort into additional distinct complexes. In particular, complexes containing PHO, the only known DNA-binding member of the PcG (4), may be important for targeting other PcG complexes to sites of action. We note that PHO is not detected as a stable member of either the ESC-E(Z) (Fig. 3) or PH-PC-PSC complexes (51).

Despite the presence of biochemically separable PcG complexes, the similar mutant phenotypes and genetic interactions of PcG genes indicate that they work together at some level. Any model for PcG repression must therefore accommodate both the biochemical separability and functional synergy of PcG complexes. One possibility is that repression requires multiple chromatin-modifying events by the different PcG complexes. This would be similar to the in vivo synergy between the chromatin-modifying SWI-SNF and SAGA complexes, which are both required for maintenance of HO expression in yeast (9, 34). An alternative possibility is that one PcG complex directly modifies chromatin while the other complex counteracts trithorax group activation by inhibiting the chromatin-remodeling activity of the brahma complex (41, 51). Indeed, the first evidence that a PcG complex may covalently modify chromatin is provided by the recent report of histone deacetylase activity associated with mammalian homologs of ESC and E(Z) (64).

These mechanisms are inconsistent with an esc role limited to the transition from gap repressors to PcG repressors (22, 48, 55). Instead, we suggest that ESC is more globally involved in chromatin regulation and that this involvement is most critical early in fly development. Consistent with a global role, EED mRNA is expressed in many tissues during mouse development (49). Furthermore, the C. elegans homolog of ESC, MES-6, is a transcriptional repressor that functions in germ line development (31, 33). MES-6 in worms therefore plays a distinct developmental role from ESC in flies. This suggests that ESC participates in a general repression mechanism that has been adapted for use in different cell lineages, rather than in the specific transition between gap protein and PcG protein repression.

If ESC-E(Z) complexes function as general chromatin regulators, the early requirement for ESC in Drosophila must be reconciled with the need for long-term PcG repression during development. One possibility is that another protein replaces ESC in the ESC-E(Z) complex at late developmental stages, when ESC is no longer critically required. Alternatively, E(Z) may associate with a completely different set of PcG proteins to supply the biochemical function provided by ESC-E(Z) complexes during embryogenesis. To address these possibilities, the nature of E(Z) complexes at postembryonic stages will have to be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ellen Miller, Doug Bornemann, and Aidan Peterson for helping to generate and characterize the PH antibody, and we thank Rick Jones for providing E(Z) antibody and Judy Kassis for providing PHO antibody. We thank Ophelia Papoulas, Mary Porter, Zhaohui Shao, Osamu Shimmi, Steve Johnson, and Natalie Coe for advice on gel filtration experiments. We are grateful to Laura Mauro for useful discussions about protein phosphorylation. We also thank Ophelia Papoulas, Mike O'Connor, Tom Hays, and members of the Simon laboratory for discussions, input and critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM49850 to J.S., and J.N. was supported in part by NIH training grant HD07480.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkema M J, Bronk M, Verhoeven E, Otte A, van't Veer L J, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Identification of Bmi1-interacting proteins as constituents of a multimeric mammalian Polycomb complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11:226–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornemann D, Miller E, Simon J. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene Sex comb on midleg (Scm) encodes a zinc finger protein with similarity to polyhomeotic protein. Development. 1996;122:1621–1630. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bornemann D, Miller E, Simon J. Expression and properties of wild-type and mutant forms of the Drosophila Sex combs on Midleg repressor protein. Genetics. 1998;150:675–686. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J L, Mucci D, Whiteley M, Dirksen M L, Kassis J A. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene pleiohomeotic encodes a DNA binding protein with homology to the transcription factor YY1. Mol Cell. 1998;1:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunk B P, Martin E C, Adler P N. Drosophila genes Posterior sex combs and suppressor two of zeste encode proteins with homology to the murine bmi-1 oncogene. Nature. 1991;353:351–353. doi: 10.1038/353351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrington E C, Jones R S. The Drosophila Enhancer of zeste gene encodes a chromosomal protein: examination of wild-type and mutant protein distribution. Development. 1996;122:4073–4083. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll S B, Laymon R A, McCutcheon M A, Riley P D, Scott M P. The localization and regulation of the Antennapedia protein expression in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1986;47:113–122. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celniker S E, Keelan D J, Lewis E B. The molecular genetics of the bithorax complex of Drosophila: characterization of the product of the Abdominal-B domain. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1424–1436. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosma M P, Tanaka T, Nasmyth K. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle- and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell. 1999;97:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui X, De Vivo I, Slany R, Miyamoto A, Firestein R, Cleary M L. Association of SET domain and myotubularin-related proteins modulates growth control. Nat Genet. 1998;18:331–337. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeCamillis M, Brock H W. Expression of the polyhomeotic locus in development of Drosophila melanogaster. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1994;203:429–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00188692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeCamillis M, Cheng N, Pierre D, Brock H W. The polyhomeotic gene of Drosophila encodes a chromatin protein that shares polytene chromosome-binding sites with Polycomb. Genes Dev. 1992;6:223–232. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denis G V, Green M R. A novel, mitogen-activated nuclear kinase is related to a Drosophila developmental regulator. Genes Dev. 1996;10:261–271. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denisenko O, Shnyreva M, Suzuki H, Bomsztyk K. Point mutations in the WD40 domain of Eed block its interaction with Ezh2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5634–5642. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dingwall A K, Beek S J, McCallum C M, Tamkun J W, Kalpana G V, Goff S P, Scott M P. The Drosophila snr1 and brm proteins are related to yeast SWI/SNF proteins and are components of a large protein complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:777–791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dura J-M, Randsholt N B, Deatrick J, Erk I, Santamaria P, Freeman J D, Freeman S J, Weddell D, Brock H W. A complex genetic locus, polyhomeotic, is required for segmental specification and epidermal development in D. melanogaster. Cell. 1987;51:829–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franke A, DeCamillis M, Zink D, Cheng N, Brock H W, Paro R. Polycomb and polyhomeotic are constituents of a multimeric protein complex in chromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1992;11:2941–2950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frei E, Bopp D, Burri M, Baumgartner S, Edström J E, Noll M. Isolation and structural analysis of the extra sex combs gene of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:127–134. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritsch C, Brown J L, Kassis J A, Muller J. The DNA-binding polycomb group protein pleiohomeotic mediates silencing of a Drosophila homeotic gene. Development. 1999;126:3905–3913. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillespie S K, Wasserman S A. Dorsal, a Drosophila Rel-like protein, is phosphorylated upon activation of the transmembrane protein Toll. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3559–3568. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunster M J, Satijn D P E, Hamer K M, den Blaauwen J L, de Bruijn D, Alkema M J, van Lohuizen M, van Driel R, Otte A P. Identification and characterization of interactions between the vertebrate Polycomb-group protein BMI1 and human homologs of polyhomeotic. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2326–2335. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutjahr T, Frei E, Spicer C, Baumgartner S, White R A, Noll M. The Polycomb-group gene, extra sex combs, encodes a nuclear member of the WD-40 repeat family. EMBO J. 1995;14:4296–4306. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto N, Brock H W, Nomura M, Kyba M, Hodgson J, Fujita Y, Takihara Y, Shimada K, Higashinakagawa T. RAE28, BMI1 and M33 are members of heterogeneous multimeric mammilian Polycomb group complexes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:356–365. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynes S R, Mozer B A, Bhatia-Dey N, Dawid I B. The Drosophila fsh locus, a maternal effect homeotic gene, encodes apparent membrane proteins. Dev Biol. 1989;134:246–257. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holdemann R, Nehrt S, Strome S. MES-2, a maternal protein essential for viability of the germline in Caenorhabditis elegans, is homologous to a Drosophila Polycomb group protein. Development. 1998;125:2457–2467. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones C A, Ng J, Peterson A J, Morgan K, Simon J, Jones R S. The Drosophila esc and E(z) proteins are direct partners in Polycomb group-mediated repression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2825–2834. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones R S, Gelbart W M. Genetic analysis of the enhancer of zeste locus and its role in gene regulation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1990;126:185–199. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones R S, Gelbart W M. The Drosophila Polycomb-group gene enhancer of zeste contains a region with sequence similarity to trithorax. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6357–6366. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karch F, Bender W, Weiffenbach B. abdA expression in Drosophila embryos. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1573–1587. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufman T C, Lewis R, Wakimoto B. Cytogenetic analysis of chromosome 3 in Drosophila melanogaster: the homeotic gene complex in polytene interval 84A-B. Genetics. 1980;94:115–133. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly W G, Fire A. Chromatin silencing and the maintenance of a functional germline in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1998;125:2451–2456. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennison J A. Transcriptional activation of Drosophila homeotic genes from distant regulatory elements. Trends Genet. 1993;9:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korf I, Fan Y, Strome S. The Polycomb group in Caenorhabditis elegans and maternal control of germline development. Development. 1998;125:2469–2478. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krebs J E, Kuo M H, Allis C D, Peterson C L. Cell cycle-regulated histone acetylation required for expression of the yeast HO gene. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1412–1421. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyba M, Brock H W. The Drosophila Polycomb group protein Psc contacts ph and Pc through specific conserved domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2712–2720. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis E B. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature. 1978;276:565–570. doi: 10.1038/276565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lonie A, D'Andrea R, Paro R, Saint R. Molecular characterization of the Polycomblike gene of Drosophila melanogaster, a trans-acting negative regulator of homeotic gene expression. Development. 1994;120:2629–2636. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin E C, Adler P N. The Polycomb group gene Posterior sex combs encodes a chromosomal protein. Development. 1993;117:641–655. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKeon J, Brock H W. Interactions of the Polycomb group of genes with homeotic loci of Drosophila. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1991;199:387–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01705848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng J, Li R, Morgan K, Simon J. Evolutionary conservation and predicted structure of the Drosophila extra sex combs repressor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6663–6672. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papoulas O, Beek S J, Moseley S L, McCallum C M, Sarte M, Shearn A, Tamkun J W. The Drosophila trithorax group proteins BRM, ASH1 and ASH2 are subunits of distinct protein complexes. Development. 1998;125:3955–3966. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paro R, Hogness D S. The Polycomb protein shares a homologous domain with a heterochromatin-associated protein of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:263–267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson A J, Kyba M, Bornemann D, Morgan K, Brock H W, Simon J. A domain shared by the Polycomb group proteins Scm and ph mediates heterotypic and homotypic interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6683–6692. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips M D, Shearn A. Mutations in polycombeotic, a Drosophila Polycomb group gene, cause a wide range of maternal and zygotic phenotypes. Genetics. 1990;125:91–101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/125.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pirrotta V. PcG complexes and chromatin silencing. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian S, Capovilla M, Pirrotta V. Molecular mechanisms of pattern formation by the BRE enhancer of the Ubx gene. EMBO J. 1993;12:3865–3877. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rastelli L, Chan C S, Pirrotta V. Related chromosome binding sites for zeste, suppressors of zeste and Polycomb group proteins in Drosophila and their dependence on Enhancer of zeste function. EMBO J. 1993;12:1513–1522. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sathe S S, Harte P J. The Drosophila extra sex combs protein contains WD motifs essential for its function as a repressor of homeotic genes. Mech Dev. 1995;52:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00392-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schumacher A, Faust C, Magnuson T. Positional cloning of a global regulator of anterior-posterior patterning in mice. Nature. 1996;383:250–253. doi: 10.1038/383250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sewalt R G A B, van der Vlag J, Gunster M J, Hamer K M, den Blaauwen J L, Satijn D P E, Hendrix T, van Driel R, Otte A P. Characterization of interactions between the mammalian Polycomb-group proteins Enx1/EZH2 and EED suggests the existence of different mammalian Polycomb-group protein complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3586–3595. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shao Z, Raible F, Mollaaghababa R, Guyon J R, Wu C T, Bender W, Kingston R E. Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell. 1999;98:37–46. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimell M J, Peterson A J, Burr J, Simon J A, O'Connor M B. Functional analysis of repressor binding sites in the iab-2 regulatory region of the abdominal-A homeotic gene. Dev Biol. 2000;218:38–52. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimell M J, Simon J, Bender W, O'Connor M B. Enhancer point mutation results in a homeotic transformation in Drosophila. Science. 1994;264:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.7909957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon J. Locking in stable states of gene expression: transcriptional control during Drosophila development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:376–385. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simon J, Bornemann D, Lunde K, Schwartz C. The extra sex combs product contains WD40 repeats and its time of action implies a role distinct from other Polycomb group products. Mech Dev. 1995;53:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon J, Chiang A, Bender W. Ten different Polycomb group genes are required for spatial control of the abdA and AbdB homeotic products. Development. 1992;114:493–505. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sinclair D A R, Milne T A, Hodgson J W, Shellard J, Salinas C A, Kyba M, Randazzo F, Brock H W. The Additional sex combs gene of Drosophila encodes a chromatin protein that binds to shared and unique Polycomb group sites on polytene chromosomes. Development. 1998;125:1207–1216. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.7.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Struhl G. A gene product required for correct initiation of segmental determination in Drosophila. Nature. 1981;293:36–41. doi: 10.1038/293036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Struhl G, Akam M. Altered distributions of Ultrabithorax transcripts in extra sex combs mutant embryos of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1985;4:3259–3264. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Struhl G, Brower D. Early role of the esc+ gene product in the determination of segments in Drosophila. Cell. 1982;31:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strutt H, Paro R. The Polycomb group protein complex of Drosophila melanogaster has different compositions at different target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6773–6783. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tie F, Furuyama T, Harte P J. The Drosophila Polycomb group proteins ESC and E(Z) bind directly to each other and co-localize at multiple chromosomal sites. Development. 1998;125:3483–3496. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tokunaga C, Stern C. The developmental autonomy of extra sex combs in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1965;11:50–81. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Vlag J, Otte A P. Transcriptional repression mediated by the human polycomb-group protein EED involves histone deacetylation. Nat Genet. 1999;23:474–478. doi: 10.1038/70602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Lohuizen M, Tijms M, Voncken J W, Schumacher A, Magnuson T, Wientjens E. Interaction of mouse Polycomb-group (Pc-G) proteins Enx1 and Enx2 with Eed: indication for separate PcG complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3572–3579. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wall M A, Coleman D E, Lee E, Iniguez-Lluhi J A, Posner B A, Gilman A G, Sprang S R. The structure of the G protein heterotrimer Giα1β1γ2. Cell. 1995;83:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White R A H, Wilcox M. Distribution of Ultrabithorax proteins in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1985;4:2035–2043. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang C-C, Bienz M. Segmental determination in Drosophila conferred by hunchback (hb), a repressor of the homeotic gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7511–7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]