Abstract

The cases of human infections caused by Serratia fonticola are relatively rare. The few cases that have been reported primarily describe skin and soft tissue, urinary, and biliary tract infections. We describe a case of a 59-year-old man with infected bilateral lower extremity wounds who developed endocarditis due to S fonticola confirmed with transesophageal echocardiogram. The patient was treated with 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy and had an uneventful recovery. After a thorough review of the literature using PubMed and Google Scholar, we concluded that this is the first reported case of endocarditis caused by S fonticola.

Keywords: Serratia fonticola, endocarditis, Enterobacteriaceae, septic shock

Introduction

The Enterobacteriaceae, Serratia fonticola, was first described as a new species in 1979 after isolation from freshwater and soil. 1 Following the discovery of environmental strains of S fonticola, human clinical specimens were isolated from wounds, yet the clinical significance was unknown. 2 The first documented human infection caused by S fonticola was identified from a leg abscess in France in 1991. 3 The cases of human infections associated with S fonticola are relatively uncommon with a prior publication inquiring whether the organism is a pathogen itself or simply a bystander. 4 Although there have been cases of biliary and urinary infections with S fonticola, there have not been any associated cardiac presentations.5,6 After extensive review of literature using PubMed and Google Scholar, we concluded that this is the first reported case of endocarditis caused by S fonticola.

Case Report

The patient of interest is a 59-year-old man with history of ascending aortic aneurysm, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction, bilateral lower extremity venous stasis ulcers, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, and multinodular goiter. The patient was brought to the emergency department by ambulance following a ground-level fall while ambulating in his home. At the time of the fall, the patient stated he felt his heart racing, but denied dyspnea, chest pain, or loss of consciousness. The patient noted the deterioration of his health in the prior month during which time he stated that he was unable to properly care for his bilateral lower extremity wounds. The patient frequently attempted to clean his wounds with water and a washcloth during his daily bandage changes.

On presentation to the emergency department, he was found to be in septic shock with blood pressure of 84/53 mm Hg, heart rate of 124 beats per minute, and lactate of 3 mg/dL. His physical examination was remarkable for 3 lower extremity ulcers below the knee. On the right extremity, the patient had 2 medial ulcers measuring 8 × 5 cm (depth to the muscle tissue) and 6 × 3 cm. On the left extremity, he had 1 medial ulcer measuring 8 × 5 cm (depth to the muscle tissue). All 3 ulcers had necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue manifested with maggots.

Initial laboratory values were also significant for C-reactive protein (CRP) of 6.97 mg/L, creatinine of 3.54 mg/dL, elevated troponin of 0.06 ng/mL (which subsequently increased to 9.8 ng/mL), and elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 14.8 × 103 cells per mL with 83.6% neutrophils. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. Chest X-ray showed an enlarged heart with a tortuous aorta. X-ray imaging of the tibia and fibula was negative for osteomyelitis but showed bilateral areas of subcutaneous gas formation suspicious of a gas-forming organism.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of septic shock and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. Sepsis bundle was initiated with careful fluid resuscitation due to his heart failure and vasopressor support with norepinephrine. On admission, 2 sets of blood cultures from separate sites and a urine culture were obtained prior to the initiation of antibiotic treatment. He was then started on broad-spectrum antibiotics for focused coverage of skin and soft tissue infection with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated given the patient’s elevated troponins along with amiodarone for treatment for chronic atrial fibrillation refractory to digoxin. The patient was subsequently taken to the operating room for debridement of bilateral lower extremity necrotic skin and soft tissue. Thorough debridement demonstrated that muscle tissue was not involved.

On the first set of blood cultures, both the aerobic and anaerobic bottles grew gram negative rods and gram positive cocci resembling Staphylococcus species which were ultimately identified as S fonticola and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Of the second set of blood cultures, only the aerobic bottle grew gram negative rods resembling enterics which were ultimately identified as S fonticola. S fonticola was resistant only to amoxicillin/clavulanate (Table 1). Urine culture was unremarkable. On completion of blood culture susceptibility results, on the fourth day of hospitalization, vancomycin was discontinued and piperacillin/tazobactam was de-escalated to ceftriaxone.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial Susceptibilities, based on Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), for Serratia fonticola and Staphylococcus aureus From Blood Culture Set.

| Antibiotic | MIC (mg/L) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Serratia fonticola from blood culture | ||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | >32 | Resistance |

| Cefepime | <1 | Sensitive |

| Ceftazidime | <1 | Sensitive |

| Ceftriaxone | <1 | Sensitive |

| Ciprofloxacin | <0.25 | Sensitive |

| Gentamicin | <1 | Sensitive |

| Meropenem | <0.25 | Sensitive |

| Pipperacillin/tazobactam | <4 | Sensitive |

| Tobramycin | <1 | Sensitive |

| Trimethoprim/sulfa | <20 | Sensitive |

| Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Staphylococcus aureus from blood culture | ||

| Clindamycin | <0.25 | Sensitive |

| Oxacillin | <0.25 | Sensitive |

| Vancomycin | 1 | Sensitive |

| Trimethoprim/sulfa | <0.10 | Sensitive |

Cardiac echocardiogram demonstrated dilation of all cardiac chambers with mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. Left ventricular systolic function was severely depressed with an estimated ejection fraction of 15% to 20%. Diastolic function was unable to be assessed due to atrial fibrillation. The patient was also noted to have abnormal septal motion secondary to bundle branch block with abnormal regional wall motion due to underlying coronary acute disease and myocardial infarction. The right ventricle was noted to be moderately dilated with mild to moderate reduced right ventricular systolic function with systolic pressure of 45 mm Hg and moderate tricuspid regurgitation.

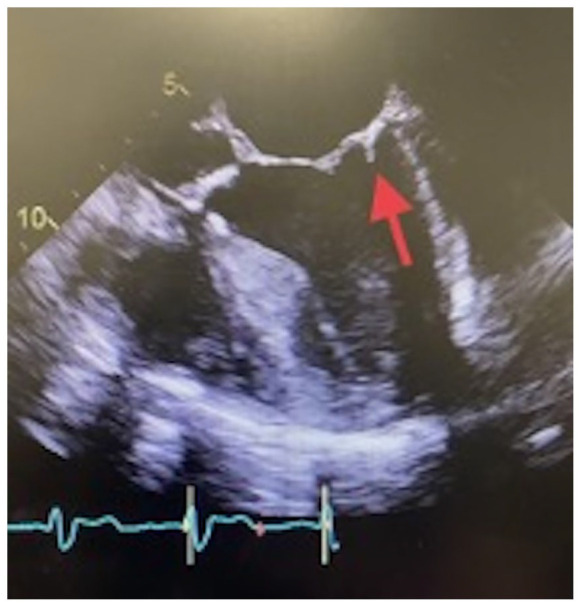

On improvement and transfer from ICU to regular unit, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was performed which demonstrated severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 15% to 20% and severe low-flow low-gradient aortic valve stenosis. In addition, TEE demonstrated a mitral valve vegetation measuring less than 1 cm attached to the posterior annulus (Figure 1). A mobile echo density measuring 0.8 × 1.6 cm consistent with a thrombus was also seen in the left atrium. The source of infection leading to the infective endocarditis was determined to be the patient’s chronic bilateral lower extremity skin infection. The patient also underwent cardiac catheterization which revealed severe 2 vessel coronary artery disease.

Figure 1.

transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) image demonstrating a less than 1 cm vegetation attached to the posterior annulus of the mitral valve.

In consultation with infectious diseases, ceftriaxone was changed to cefepime in the milieu of infective endocarditis, due to increased incidence of inducible amp-C beta-lactamase production among Serratia species with use of ceftriaxone. 7 For effective treatment of infective endocarditis, the duration of cefepime treatment was determined to be 6 weeks due to low suspicions of coinfection with MSSA.

The patient was discharged to a skilled nursing facility to complete intravenous antibiotic therapy and obtain appropriate wound care. The patient had an uneventful recovery after completing 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy. Further outpatient management included a multidisciplinary approach with cardiology, nephrology, and infectious disease in addition to primary care.

Discussion

Although human infections are relatively uncommon, recent publications illustrated cases related to the biliary and urinary tracts, in addition to skin and soft tissue. Serratia fonticola has been a known isolate from both freshwater and soil, but there have been recent postulations that this organism may also be part of the gastrointestinal microbiota and biliary tract.4,5 However, all known human cases of S fonticola bacteremia have been related to injuries or foreign bodies. Both injury and introduction of foreign bodies to the intestinal mucosa, urinary tract, or skin and soft tissue may serve as methods of introduction for S fonticola, especially in patients with underlying health conditions and weakened immune systems.3-5,8 In this particular case, the extent and severity of this patient’s chronic bilateral lower extremity wounds were ultimately determined to be the source of the patient’s endocarditis. The patient’s prolonged history of improper wound care by daily use of the same washcloth for cleanings with water explains the source of aquatic transmission of S fonticola.

This case demonstrates the conveyance of S fonticola from environmental source to human infection. This occurred first through colonization then progressed into a local infection before hematogenously spreading to the endocardium. There have been reports of different β-Lactamase producing S fonticola such as AmpC β-lactamase, FONA (a minor Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase), oxyimino cephalosporin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, and Sfh-I, a subclass B2 metallo-beta-lactamase.9-11 Therefore, careful attention to susceptibility testing and choice of antibiotics should be made due to potential emergence of resistance during treatment of S fonticola. In this case, outcome was favorable due to effective source control with resection of all infected skin and necrotic tissues, presence of a susceptible organism, and completion of extended course of antibiotic. Despite a chance of coinfection with Staphylococcus aureus, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of mitral valve endocarditis caused by S fonticola.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: An abstract of this case report was presented at the 2021 Western Regional Research Conference.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from the Kern Medical Institutional Review Board (IRB # 20032).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Arash Heidari  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1091-348X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1091-348X

References

- 1. Gavini F, Ferragut C, Izard D, et al. Serratia fonticola, a new species from water. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1979;29(2):92-101. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farmer JJ, III, Davis BR, Hickman-Brenner FW, et al. Biochemical identification of new species and biogroups of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21(1):46-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bollet C, Gainnier M, Sainty JM, Orhesser P, De Micco P. Serratia fonticola isolated from a leg abscess. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(4):834-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aljorayid A, Viau R, Castellino L, Jump RL. Serratia fonticola, pathogen or bystander? A case series and review of the literature. IDCases. 2016;5:6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hai PD, Hoa LTV, Tot NH, et al. First report of biliary tract infection caused by multidrug-resistant Serratia fonticola. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;36:100692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stock I, Burak S, Sherwood KJ, Gruger T, Wiedemann B. Natural antimicrobial susceptibilities of strains of “unusual” Serratia species: S. ficaria, S. fonticola, S. odorifera, S. plymuthica and S. rubidaea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(4):865-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rupp ME, Fey PD. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae: considerations for diagnosis, prevention and drug treatment. Drugs. 2003;63(4):353-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gorret J, Chevalier J, Gaschet A, et al. Childhood delayed septic arthritis of the knee caused by Serratia fonticola. Knee. 2009;16(6):512-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanimoto K, Nomura T, Hashimoto Y, Hirakawa H, Watanabe H, Tomita H. Isolation of Serratia fonticola producing FONA, a minor extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), from imported chicken meat in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2021;74:79-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Péduzzi J, Farzaneh S, Reynaud A, Barthélémy M, Labia R. Characterization and amino acid sequence analysis of a new oxyimino cephalosporin-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase from Serratia fonticola CUV. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1341(1):58-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fonseca F, Arthur CJ, Bromley EHC, et al. Biochemical characterization of Sfh-I, a subclass B2 metallo-beta-lactamase from Serratia fonticola UTAD54. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(11):5392-5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]