Abstract

Lung cancer is the second most frequent cancer type in both men and women, and it is considered to be one of the major causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide. However, few biomarkers are currently available for the diagnosis of lung cancer. The aim of the present study was to investigate the function of the immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat (ISLR) gene in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism of its action. The current study analysed ISLR expression in NSCLC tumour and normal tissues using The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort datasets. ISLR expression in NSCLC cell lines was determined using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Cell Counting Kit-8, soft agar colony formation, wound healing, Transwell, flow cytometry and glycolysis assays were performed to determine the effects of ISLR silencing or overexpression on cells. The expression levels of the genes involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), apoptosis and glycolysis were evaluated via western blotting. Transfected cells were exposed to the pathway activator, IL-6, to validate the regulatory pathway. ISLR was overexpressed in NSCLC tissues and cell lines. Overall, patients with high ISLR expression had lower survival rates. In addition, small interfering RNA-ISLR inhibited the proliferation, EMT, migration, invasion and glycolysis of NSCLC cells, and promoted their apoptosis. ISLR overexpression had the opposite effect on tumour progression and glycolysis in NSCLC cells. Gene set enrichment analysis and western blotting results indicated that the IL-6/Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT3 pathway was enriched in ISLR-related NSCLC. Knockdown of ISLR inhibited IL-6-induced proliferation, invasion, migration and glycolysis in human NSCLC cells. In summary, ISLR silencing can inhibit tumour progression and glycolysis in NSCLC cells by activating the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling pathway, which is a potential molecular target for NSCLC diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: ISLR, NSCLC, glycolysis, tumour progression, IL-6/Janus kinase/STAT3

Introduction

Lung cancer, a malignant tumour originating from the bronchial mucosa or gland, has the highest incidence rate of all cancer types (1). Being a major threat to human health and life, lung cancer is the main cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (2). It is estimated that 1.8 million individuals are diagnosed with lung cancer, while 1.6 million die of this disease every year worldwide (3,4). Lung cancer includes non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer. The former accounts for >85% of lung squamous cell carcinomas, lung adenocarcinomas (LUAD) and large cell lung cancer (5). Over the past 20 years, various treatments, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy, have been effective for some patients with advanced NSCLC (6). However, the overall survival (OS) and cure rates of NSCLC remain very low, with a 5-year survival rate of ~15% (7). Thus, there is a need to further study the disease biology and malignant proliferation mechanism to enhance the understanding of NSCLC progression and improve the survival rate.

The human immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat (ISLR) gene (2.4-kb transcript) is located on human chromosome 15q23-q24, which is associated with multiple genetic disorders, as evidenced using linkage analysis (8). In particular, the ISLR protein is involved in various biological events, such as embryonic development (9), Gaucher's disease (10) and replicative senescence of fibroblasts in some organs, including the heart, pancreas and bone marrow (11). ISLR, also known as meflin, is a newly discovered marker of mesenchymal stem cells, which is involved in pathological fibrosis and the cancer microenvironment (12,13). In particular, it has recently been shown that the absence or low expression of ISLR can cause straightening of stromal collagen fibres in mouse and human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissues, respectively; such straightening is a hallmark of aggressive tumours (14). Moreover, ISLR expression is upregulated in the stroma of colorectal cancers and gastric carcinomas; high ISLR expression is considered to be an independent prognostic indicator for disease-free survival of patients (9,15).

However, at present, a detailed understanding of the potential functioning of the ISLR gene in NSCLC is lacking. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the potential molecular mechanisms of action of the ISLR gene and examined whether it could inhibit tumour progression and glycolysis in NSCLC. This knowledge may provide novel prospects for guiding the treatment of NSCLC.

Materials and methods

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data for LUAD

TCGA-LUAD data on ISLR expression in patients with LUAD were retrieved from the UALCAN web tool (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html). The UALCAN web tool was also used to plot the gene expression figures by using 'TCGA Gene analysis' panel (16). The potential effect of ISLR on the OS rates of patients with NSCLC was analysed using the Kaplan-Meier method with Kaplan-Meier Plotter web tools (https://kmplot.com/analysis/) in 'Lung cancer' panel (17,18).

Cell culture

Human NSCLC cell lines (H1299, H23 and A549) and normal immortalised lung epithelial cell lines (16HBE) were obtained from the China Infrastructure of Cell Line Resources, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The 16HBE cells were maintained in DMEM/high glucose medium (HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Moreover, H1299, H23 and A549 cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% FBS and placed in a constant-temperature incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Human recombinant IL-6 (cat. no. I1395-50UG; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was dissolved in PBS to a concentration of 100 µg/ml as a stock solution and stored at temperature of -20°C. The cells were pre-treated with 100 ng/ml IL-6 for 48 h at room temperature.

Cell transfection

ISLR small interfering RNA (siRNA/si) packaged in lentivirus was purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd., and pcDNA3.1-ISLR plasmid was synthesised by Genomeditech Biotechnology. Human NSCLC cell lines were seeded and cultured in 24-well plates for 1 day. After reaching 80% confluency, according to the manufacturer's instructions for Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), A549 cells (1×105 cells) were transfected with si-negative control (NC) or si-ISLR (10 µl; 2×108 TU/ml) to construct the ISLR knockdown cell model, and H1299 cells (1×105cells) transfected with pcDNA3.1-ISLR plasmid (4 µg), vector only (pcDNA3.1-NC) or blank control to construct the ISLR overexpression cell model at 37°C for 48 h. The 24-well plates were then placed in an incubator. After 6 h, the medium in each well was replaced with the fresh RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were used for the subsequent experiments. The following sequences (from 5′→3′) were used: si-ISLR-1, CAGCCACAATCTCATCTCTGACTTT; si-NC-1, CAGACACTAACTTCTGTCCACCTTT; si-ISLR-2, TGCACAACCTCAGTGCCCTCCAATT; and si-NC-2, TGC CAACTCTGACCGCTCACACATT.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted using an RNA kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Then, cDNA was amplified using a real-time PCR kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) in a reaction mixture containing 7 µl dH2O, 1 µl cDNA, 2 µl ISLR primers (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 10 µl SYBR-Green qPCR mix according to the manufacturer's instructions. The conditions for RT were as follows: 25°C for 5 min, 55°C for 20 min and 85°C for 5 min. qPCR was performed using a 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The reaction conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 96°C for 3 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 96°C for 15 sec; annealing and extension, both at 58°C for 30 sec; final extension at 72°C for 50 sec. The final relative expression of ISLR was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (19) and normalised to that of GAPDH. The primers were synthesised by Genomeditech Biotechnology. The sequences (from 5′→3′) of primers of ISLR were TGTTGCTGCAGAGAAGCAGT (forward) and CCTGCATGGTGCCTCCTTCA (reverse); and GAPDH, TCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCGACAC (forward) and CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTC (reverse).

Cell viability

Cell viability was estimated using the Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 assay (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In total, ~104 NSCLC cells were seeded in the 96-well plates with 100 µl medium in each well and incubated at 37°C for 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Then, 10 µg CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Finally, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Thermomax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC).

Soft agar colony formation

Cell proliferation was detected using a colony formation assay. After 48 h of transfection, the cells (500 cells) were seeded in 6-well plates with complete medium for 2 weeks, which was replaced every 3 days. Colonies with >50 cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at 37°C, stained with crystal violet for 10-20 min at 37°C and counted under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×10). Finally, the data obtained from five stochastic fields were used for the statistical analysis.

Wound healing assay

Cell motility was confirmed using a wound healing assay. After 48 h of transfection, A549 and H1299 cells were digested with trypsin, and the cell suspension (50 µl; 4.5×105 cells/ml) was prepared and seeded into each well of a 6-well plate using serum-free medium. When the confluency of cells reached 80%, a horizontal line was drawn on each well with a 200 µl pipette tip, and cells were flushed twice with PBS. Cell movement and migration in the entire wound area were observed using an inverted optical microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×100). Finally, to evaluate healing, the cells were imaged using a microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×100) at 48 h after the scratch. The migration rate was quantified as the average distance travelled by the cells to the original wound surface.

Transwell assay

Cell invasive abilities were evaluated using Transwell chambers with 8-µm porous membranes coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at 37°C for 48 h. According to the manufacturer's protocols, A549 and H1299 cells (5×105 cells/ml) in RPMI-1640 medium without FBS were seeded into the upper chamber of a Transwell insert. RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After 24 h, cells on the upper side of the membrane were removed using a cotton swab, followed by washing with PBS three times. The cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and stained with 0.2% crystal violet (Biotechnology) for 10 min at room temperature. Finally, the images were captured using an inverted microscope (Nikon Corporation; magnification, ×100).

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis

The Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit (BD Biosciences) was used for staining, and flow cytometry was used to detect cell apoptosis. Briefly, the harvested NSCLC cells were flushed with PBS and resuspended in 500 µl conjugate buffer. Then, 10 µl Annexin V-FITC and 10 µl PI (BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences) were added to the buffer at 37°C for 15 min. A FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used to analyse cell apoptosis after 1 h (early + late apoptosis). FlowJo (version 10.6.2; FlowJo LLC) was used to analyse the data.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors for 30 min on ice. The density of all proteins extracted from the supernatant of the cell lysate was detected using a BCA Protein Assay kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). Next, the proteins (40 µg per lane) were separated with 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and the specific proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at 37°C and incubated with primary antibodies (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) against vimentin (cat. no. 5741; 1:1,000), N-cadherin (cat. no. 13116; 1:1,000), E-cadherin (cat. no. 3195; 1:1,000), glucose transporter 1 (Glut-1; cat. no. 73015; 1:1,000), hexokinase 2 (HK-2; cat. no. 2867; 1:1,000), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA; cat. no. 3582; 1:1,000), Bcl-2 (cat. no. 4223; 1:1,000), Bax (cat. no. 2774; 1:1,000), cleaved caspase-3 (cat. no. 9654; 1:1,000), Janus kinase (JAK)2 (cat. no. 3230; 1:1,000), phosphorylated (p)-JAK2 (Tyr1,007/1,008; cat. no. 3776; 1:1,000), STAT3 (cat. no. 12640; 1:1,000), p-STAT3 (Tyr705; cat. no. 9145; 1:1,000) and GADPH (cat. no. 5174; 1:1,000) overnight at 4°C. After three washes with TBS-0.1% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. 7076; 1:3,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 45 min at room temperature. GAPDH served as the control. The intensity of protein expression was measured using an ECL reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). ImageJ software (version 6.0; National Institutes of Health) was used to semi-quantify the protein expression.

Glycolysis analysis

The glucose uptake colorimetric assay, lactate colorimetric assay and ATP colorimetric assay kits (Biovision, Inc.) were used to examine glucose consumption and lactate and ATP production in A549 and H1299 cells, according to the manufacturer's protocols.

ELISA

A human IL-6 ELISA kit (cat. no. PI330; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to detect the concentrations of human IL-6 in the cell supernatant according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cell supernatant was harvested via centrifugation (500 × g; 4°C; 10 min). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured for 48 h, and 200 µl culture supernatant was used for detection.

Tissue samples and immunohistochemistry

Non-tumorous lung tissue and primary lung cancer tissues (2 cm away from the tumour margin) were collected from 38 patients (21 men and 17 women; age range, 27-81 years; median age, 54 years) who underwent surgical resection at The Shandong Second Provincial General Hospital between June 2020 and March 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) None of the patients received neoadjuvant therapy; ii) study patients were diagnosed with lung cancer via histopathology; and iii) diagnosis was confirmed by two independent pathologists. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Lung cancer cases with unconfirmed pathology; ii) lung cancer cases with incomplete data records; and iii) patients receiving chemotherapy and radiotherapy prior to the surgery. The use of patient samples was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Shandong Second Provincial General Hospital (approval no. XYK20200511).

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 25°C for 24 h, dehydrated and made transparent using gradient alcohol, following which they were paraffin embedded. The sections (thickness, 5 µm) separated from lung tissue were soaked in citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) and heated in a 850 W power microwave oven for 10 min to conduct antigen repair. Tissue sections were incubated in 3% H2O2 for 15 min at room temperature and blocked in 10% normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the tissues were incubated with primary antibody against ISLR (cat. no. ab232986; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Next the sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L secondary antibody (1:1,000; Abcam; cat. no. ab150077) at room temperature for 30 min. The sections were stained with haematoxylin at room temperature for 30 sec (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), dried in an oven at 65°C, rinsed in water, then mixed with alcohol (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and xylene (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and naturally dried. Finally, the sections were observed under a stereomicroscope (magnification, ×200; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Bioinformatics analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (20) was performed on TCGA database datasets (LUAD; https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) of ISLR expression using the R package 'clusterProfiler' (21). For GSEA, ISLR expression was treated as a numeric variable. The Pearson correlation coefficients of other genes and ISLR expression were calculated, and the genes were sequenced according to the correlation coefficients. The hallmark gene sets were deposited in the GSEA Molecular Signatures Database resource (h.all. v7.1.symbols.gmt; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp), the differential pathways between the high- and low-ISLR expression specimens were identified. The number of permutations was 1,000. Normalised enrichment score >1 and false discovery rate q-value <0.05 were established as cut-offs for significant enrichment.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analysed using SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS, Inc.). Survival curves were analysed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests. All the experiments were conducted in triplicate, and all data are expressed as the mean ± SD. An unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare differences between two groups, while one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test were used to compare differences between multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

ISLR expression is elevated both in NSCLC tissues and cell lines

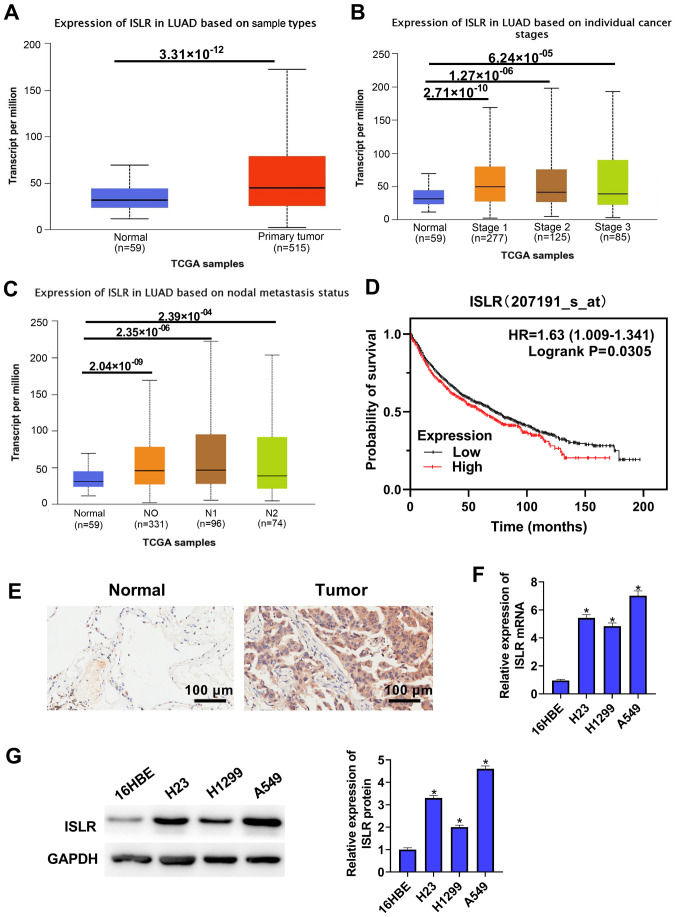

To identify ISLR expression in NSCLC, TCGA-LUAD cohort datasets were analysed and it was found that ISLR expression was upregulated in the NSCLC tumour tissues compared with that in the normal tissues (Fig. 1A). TCGA cohort data-sets showed that ISLR expression in both NSCLC (at different stages) and nodal metastasis cancers were significantly higher compared with those in normal tissues (Fig. 1B and C). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that NSCLC cases with high expression of ISLR had poorer OS compared with patients with low ISLR expression (Fig. 1D). The immunohistochemical results identified that ISLR expression in lung cancer tissues was higher than that in non-tumorous lung tissues (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

ISLR expression is elevated both in NSCLC tissues and cell lines. (A) TCGA-LUAD cohort datasets showed that ISLR expression was higher in tumour tissues than in normal tissues. Analysis of TCGA data showed that ISLR was highly expressed in cancers at (B) different stages and (C) in nodal metastasis cancer. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival plots demonstrated that higher ISLR abundance correlated with poorer OS, as determined using TCGA database. (E) ISLR expression in non-tumorous lung tissues and primary lung cancer tissues was measured via immunohistochemistry. Scale bar, 100 µm. ISLR expression in NSCLC cell lines (A549, H1299 and H23) and normal immortalized lung epithelial cell lines (16HBE) was measured via (F) reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and (G) western blotting. *P<0.05 vs. 16HBE cells. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma.

ISLR expression was also detected in several NSCLC cell lines and normal immortalised lung epithelial cell lines via RT-qPCR and western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1F and G, compared with 16HBE cells, ISLR expression was significantly upregulated in all evaluated NSCLC cell lines, with that in A549 cells being the most pronounced, followed by H23 and H1299 cells exhibiting the least upregulation. These results indicated that the abnormal expression of ISLR may be associated with NSCLC progression. The selection of cell types was determined according to the expression of ISLR. A549 cells expressed relatively high levels of ISLR, whereas H1299 cells expressed relatively low levels of ISLR; therefore, H1299 and A549 cells were used in subsequent experiments with pcDNA3.1-ISLR vectors and siRNA, respectively.

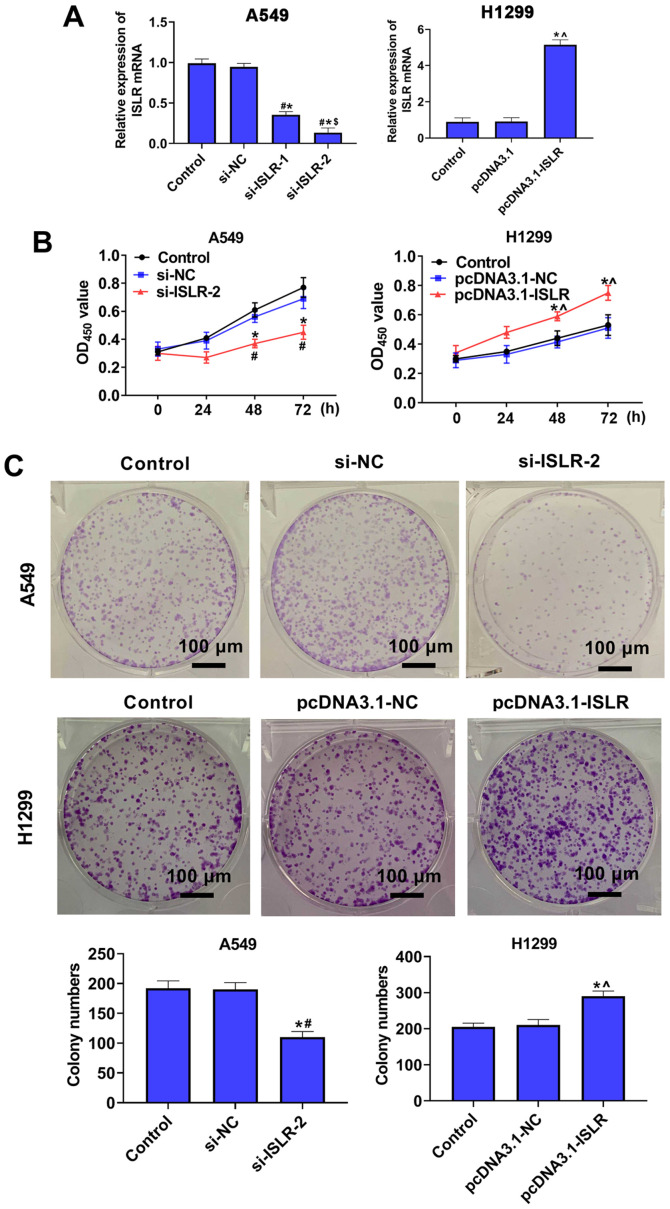

ISLR promotes the proliferation of NSCLC cells

To further investigate the role of ISLR in the progression of NSCLC, A549 and H1299 cells were selected for the follow-up experiments. Subsequently, ISLR was knocked down in A549 cells and overexpressed in H1299 cells, and the expression levels were verified using RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A). Cell viability and proliferation were detected using the CCK-8 and colony formation assays, respectively. The results demonstrated that ISLR knockdown suppressed proliferation and colony number in A549 cells, whereas ISLR overexpression promoted the proliferation of H1299 cells (Fig. 2B and C), suggesting that si-ISLR inhibited the proliferation of NSCLC cells.

Figure 2.

ISLR promotes the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells. (A) ISLR expression was examined in ISLR-silenced A549 cells and ISLR-overexpressed H1299 cells via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (B) Viability and (C) proliferative tendency of A549 cells transfected with si-ISLR or H1299 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-ISLR were evaluated using Cell Counting Kit-8 and colony formation assays, respectively. Scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. si-NC group; $P<0.05 vs. si-ISLR-1 group; ^P<0.05 vs. pcDNA3.1-NC group. ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA; OD, optical density.

ISLR promotes the migration and invasion of NSCLC cells

Wound healing and Transwell assays were performed to investigate the effect of ISLR on cell migration and invasiveness. As shown in Fig. 3A, ISLR knockdown significantly decreased A549 cell adhesion ability and the number of migrated cells; however, ISLR overexpression produced contrary effects on H1299 cells. Moreover, the invasion assays indicated that the ISLR knockdown significantly inhibited the invasion of A549 cells, whereas the opposite effect was observed when ISLR was overexpressed in H1299 cells (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

ISLR promotes the migration and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells. (A) Wound healing and (B) Transwell invasion assays were performed to detect the effect of ISLR silencing in A549 cells and ISLR overexpression in H1299 cells on migration and invasion. (C) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related protein expression levels. Scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. si-NC group; ^P<0.05 vs. pcDNA3.1-NC group. ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA.

The expression levels of proteins involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) were evaluated using western blotting. Compared with the respective control cells, ISLR silencing increased the expression level of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and reduced the expression levels of mesenchymal markers, such as N-cadherin and vimentin, in A549 cells (Fig. 3C). Conversely, ISLR overexpression produced the opposite effect on the EMT-related proteins in H1299 cells. These results indicated that ISLR silencing suppressed the EMT, migration and invasion of NSCLC cells.

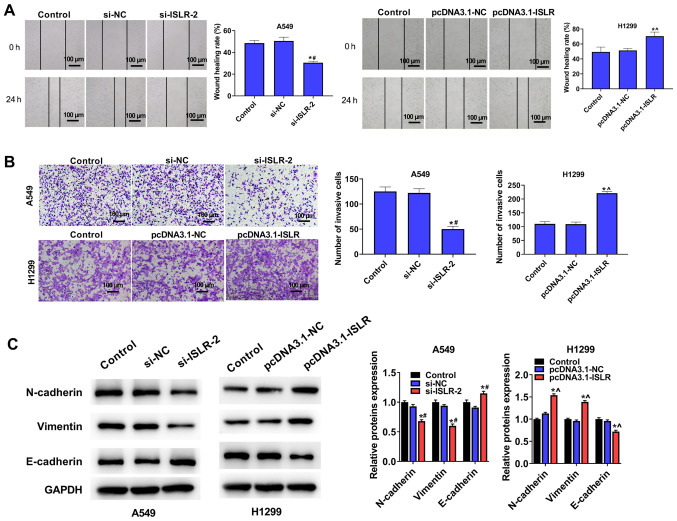

ISLR suppresses the apoptosis of NSCLC cells

The present results demonstrated that ISLR silencing increased the apoptosis of A549 cells, while overexpression of ISLR suppressed the apoptosis of H1299 cells, compared with the corresponding control group (Fig. 4A). To further determine the mechanism involving ISLR in the apoptosis of NSCLC cells, western blotting was performed to detect the expression levels of related genes. Interestingly, ISLR silencing decreased the expression levels of Bcl-2, but increased the expression levels of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 in A549 cells. By contrast, ISLR overexpression exhibited the opposite effect on the expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax and cleaved caspase-3 in H1299 cells (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results demonstrated that ISLR silencing may promote the apoptosis of NSCLC cells.

Figure 4.

ISLR suppresses the apoptosis of NSCLC cells. (A) Apoptosis of transfected A549 and H1299 cells was evaluated using flow cytometry assays. (B) Apoptosis-related protein expression levels. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. si-NC group; ^P<0.05 vs. pcDNA3.1-NC group. ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA.

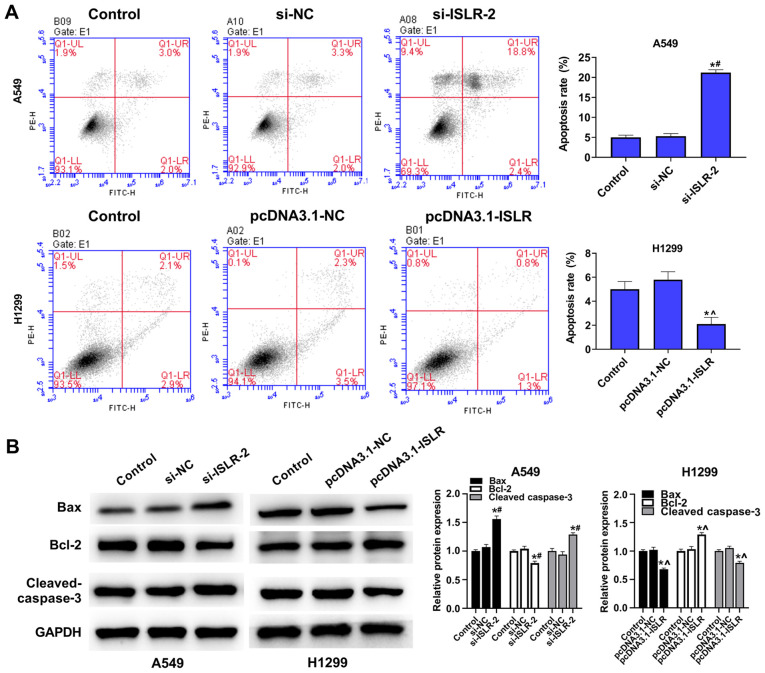

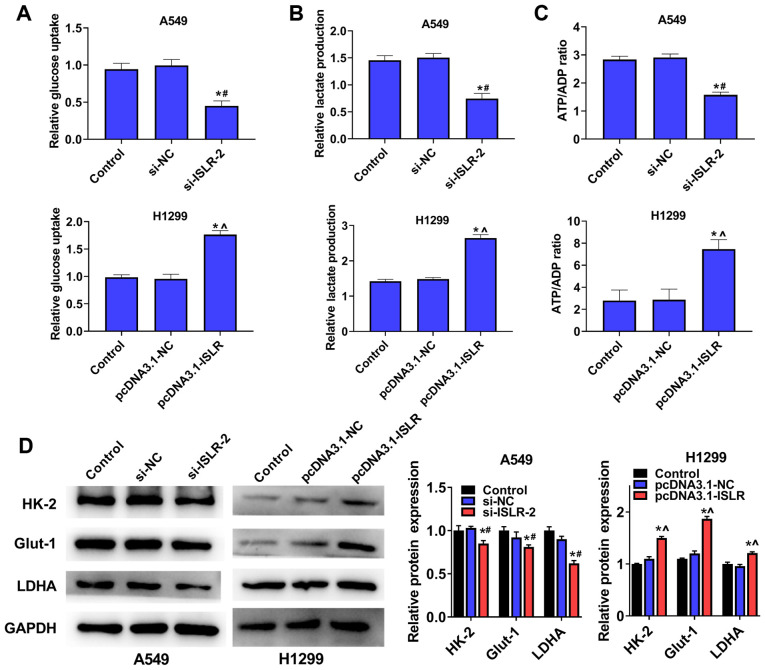

ISLR promotes aerobic glycolysis of NSCLC cells

To examine the potential role of ISLR in NSCLC glycolysis, A549 and H1299 cells were transfected with si-ISLR or pcDNA3.1-ISLR; glucose consumption, lactate production and ATP production were subsequently analysed. The results demonstrated that the silencing of ISLR expression in A549 cells inhibited cellular glucose uptake (Fig. 5A), lactate consumption (Fig. 5B) and ATP/ADP ratios (Fig. 5C), while ISLR overexpression produced the opposite effects on glycolysis progression. The western blotting results indicated that the expression levels of glycolytic target proteins (including HK-2, Glut-1 and LDHA) were downregulated in A549 cells with ISLR knockdown, whereas they were upregulated in H1299 cells with ISLR overexpression (Fig. 5D). Overall, these results indicated that the silencing of ISLR could inhibit aerobic glycolysis in NSCLC cells.

Figure 5.

ISLR suppresses the aerobic glycolysis of NSCLC cells. (A) Glucose uptake (B) lactate production and (C) ATP/ADP ratios were analysed after A549 and H1299 cells were transfected with si-ISLR or pcDNA3.1-ISLR, respectively. (D) Glycolytic target protein expression levels. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. si-NC group; ^P<0.05 vs. pcDNA3.1-NC group. ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA; HK-2, hexokinase 2; Glut-1, glucose transporter 1; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A.

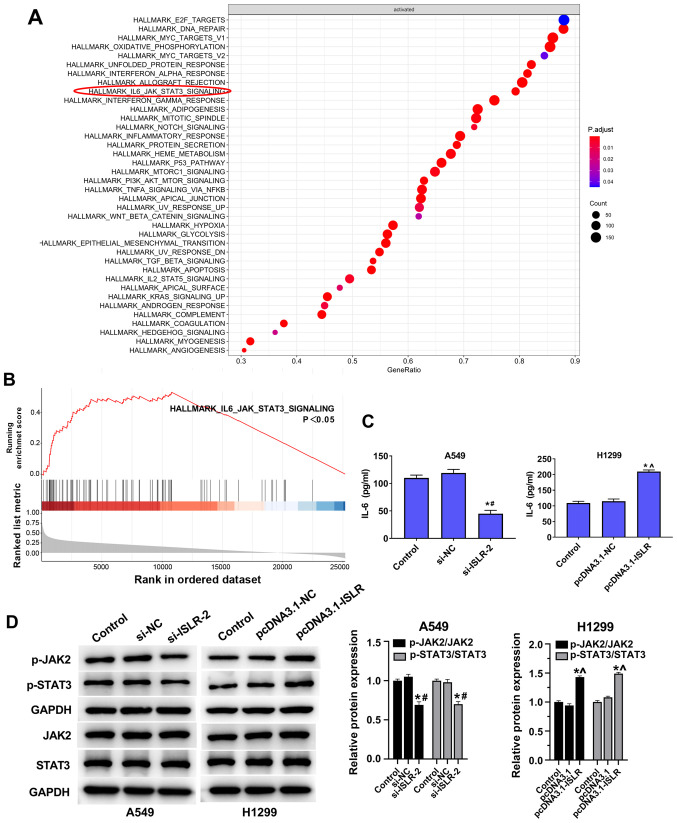

ISLR promotes tumour progression and glycolysis in NSCLC cells by inactivating the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway

The GSEA results suggested that the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway was enriched in ISLR-related NSCLC (Fig. 6A and B). ELISA results demonstrated that IL-6 levels in the culture supernatants of NSCLC cell lines were reduced by knockdown of ISLR (Fig. 6C). The knockdown of ISLR decreased the phosphorylation levels of JAK2 and STAT3, while the overexpression of ISLR increased these phosphorylation levels (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

ISLR promotes tumour progression and glycolysis of NSCLC cells by inactivating the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway. (A and B) Gene set enrichment analysis results showing that the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway was enriched in ISLR-related NSCLC. (C) Effect of ISLR knockdown on the levels of IL-6 in the cultural supernatants of NSCLC cell lines, as measured using ELISAs. (D) Effect of ISLR knockdown and overexpression on the phosphorylation levels of JAK2 and STAT3. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. si-NC group; ^P<0.05 vs. pcDNA3.1-NC group. ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; p-, phosphorylated.

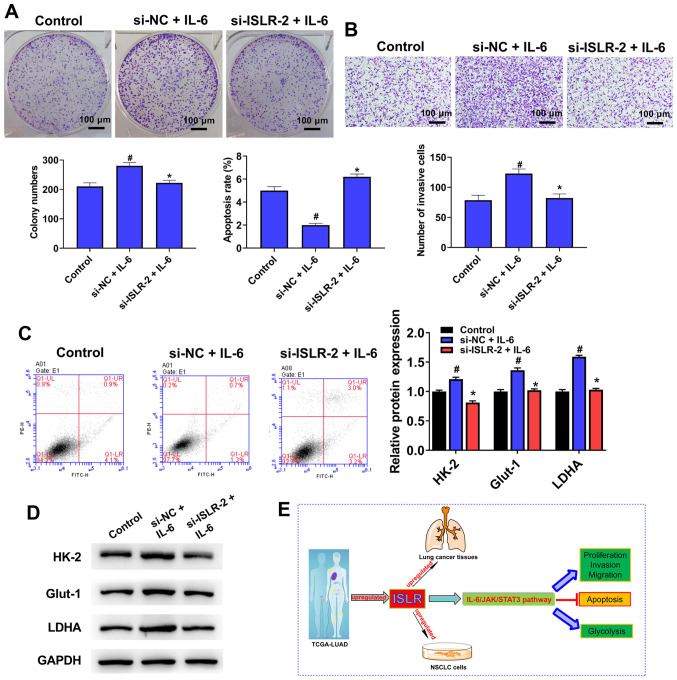

Treatment with IL-6 counteracts the ISLR knockdown-induced facilitation of tumour progression and glycolysis in NSCLC cells

To further determine the molecular mechanism of action of ISLR in the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway, IL-6 (pathway activator) was used to treat si-ISLR-transfected cells. Notably, the knockdown of ISLR reversed the promotion effects on cell proliferation (Fig. 7A), invasion (Fig. 7B), apoptosis (Fig. 7C) and glycolysis (Fig. 7D) caused by IL-6. Collectively, it was suggested that the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling pathway may be involved in the effect of ISLR on NSCLC cell progression (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

Treatment with IL-6 counteracts the ISLR knockdown-induced facilitating effects on the tumour progression and glycolysis of NSCLC cells. After pre-treatment with IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for 48 h, (A) proliferation, (B) invasion, (C) apoptosis and (D) glycolysis were determined colony formation, Transwell, flow cytometry and western blotting assays. (E) A summary figure for this study: ISLR promotes tumour progression and glycolysis of NSCLC cells by inactivating the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway. *P<0.05 vs. si-NC + IL-6 group; #P<0.05 vs. control group. ISLR, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat; NC, negative control; si, small interfering RNA; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; HK-2, hexokinase 2; Glut-1, glucose transporter 1; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; JAK, Janus kinase.

Discussion

There is currently significant interest in furthering the understanding of the genetic changes that drive NSCLC (22). New strategies for molecular diagnosis and targeted therapy of NSCLC are being explored, given the potential operability of numerous molecular-defined subtypes. A large number of molecular markers, such as microRNAs, oncogenic non-coding RNAs and long non-coding RNAs, have been recently proven to regulate various cellular processes, including glycolysis metabolism, proliferation, invasion, apoptosis and differentiation, resulting in the progression and tumorigenesis of NSCLC (23-25). The present study provided evidence on cell proliferation, invasion, apoptosis and aerobic glycolysis to support the effect of ISLR expression on the behaviour of NSCLC, which could be used as a biomarker to guide the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC.

ISLR is a marker of mesenchymal stromal cells, and as a secretory protein, it maintains the undifferentiated features of stromal cells (26). Exogenous ISLR expression in the tumour matrix inhibits the expression of α-smooth muscle actin in cancer-associated fibroblasts, as well as tumour progression. For instance, in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, ISLR inhibits α-smooth muscle actin expression (myofibroblast differentiation) and extracellular matrix remodelling in cancer-associated fibroblasts, which is crucial for cancer progression (14). In recent years, researchers have also confirmed that ISLR is essential for stromal cells to regulate epithelial cell proliferation during intestinal regeneration and tumour development, especially in colorectal cancer (26,27).

However, to the best of our knowledge, the mechanism of action of ISLR in NSCLC had not been previously investigated. To alleviate this gap, the current study characterised the expression pattern and clinical significance of ISLR in NSCLC tissues by utilising publicly available TCGA-LUAD cohort datasets. The results demonstrated that ISLR expression was upregulated in NSCLC with different stages and nodal metastasis, and was associated with poor OS. In further cellular experiments, the silencing of ISLR significantly decreased proliferation, limited migration and invasion, and increased apoptosis in NSCLC cell lines, thus indicating weakened NSCLC cell malignancy. Moreover, the overexpression of ISLR in NSCLC cells had the reverse effect on these cellular processes.

EMT is a key step in intercellular adhesion, invasion and metastasis (28). A hallmark of EMT is the reduced expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin, and elevated expression of mesenchymal markers, such as vimentin and N-cadherin, along with increasing cell migration and invasion (29). Caspase-3 is known as the executioner of apoptosis due to its role in coordinating the destruction of cell structure (30). Bcl-2 belongs to the Bcl-2 family and is one of the important factors regulating apoptosis (31). Therefore, the expression levels of proteins involved in EMT and apoptosis were evaluated using western blotting. The silencing of ISLR increased the expression of E-cadherin and cleaved caspase-3, and reduced the expression of N-cadherin, vimentin and Bcl-2 in NSCLC cells. However, ISLR overexpression had the opposite effect on these proteins in NSCLC cells. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, the present study demonstrated for the first time that ISLR was a vital contributor to NSCLC progression.

Glucose metabolism supplies energy to the cellular processes of normal cells, as well as those of cancer cells. Abnormal acceleration of glucose metabolism can be used to differentiate cancer cells from normal tissue cells (32). The majority of cancer cells employ aerobic glycolysis as an approach to energy production, whether they are under normoxic or hypoxic conditions (33). The inhibition of glucose metabolism is the main subject of clinical treatment for heterogeneous cancer types. In the current study, ISLR silencing inhibited cellular glucose uptake, lactate consumption and ATP/ADP ratios in NSCLC cells, while ISLR overexpression had the opposite effect on glycolysis progression. Glut-1 belongs to one of the dominant members of the glucose transporter family, and it has been shown to be upregulated and to facilitate glucose metabolism in cancer cells (34). Due to its reversible binding to mitochondria, HK-2 is a key regulator of glycolysis in several cancer types, and it can also prevent cancer cells from undergoing apoptosis (35). LDHA, as a redox cofactor, is activated during anaerobic glycolysis in various organisms and promotes glycolysis and cell proliferation (36). The present study identified that the protein expression levels of HK-2, Glut-1 and LDHA were downregulated in A549 cells with silenced ISLR, but were upregulated in H1299 cells with overexpressed ISLR. Collectively, these results indicated that the silencing of ISLR inhibited aerobic glycolysis in NSCLC cells.

IL-6 can also induce cellular oxidative stress, leading to cancer progression (37). IL-6, a proinflammatory cytokine in the tumour microenvironment, has been regarded as the main factor involved in EMT and contributes to tumour growth and metastasis (38). IL-6 leads to activation of the JAK/STAT signalling pathway, particularly STAT3, to promote cancer cell proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, angiogenesis, differentiation and stemness (39). Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 significantly suppresses IL-6-induced EMT, cell migration and invasion in HCC and pancreatic cancer (40,41). Furthermore, monoamine oxidase A promotes tumour cell proliferation via IL-6/STAT3 signalling (42). Lee et al (43) reported that monoamine oxidase A was downregulated as a result of IL-6/IL-6R/STAT3 signalling, and this may be attributed to Epstein-Barr virus infection in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. The present study found that knockdown of ISLR inactivated the JAK/STAT signalling pathway, as well as reversed the NSCLC cell proliferation and glycolysis induced by IL-6, suggesting that ISLR may be involved in NSCLC progression and prognosis.

Limitations of the present study included the sole use of in vitro cell experiments. Therefore, in vivo experiments are required to assess the role of ISLR in NSCLC progression, as well as the underlying mechanism.

In conclusion, ISLR expression was significantly upregulated in NSCLC tissue and cells with different staging and nodal metastasis, and was associated with poor OS. The silencing of ISLR promoted apoptosis and inhibited the proliferation, migration, invasion and glycolysis of NSCLC cells by inactivating the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathway. These factors could be used as molecular targets in crucial applications such as NSCLC diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- Glut-1

glucose transporter 1

- GSEA

gene set enrichment analysis

- HK-2

hexokinase 2

- ISLR

immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat

- LDHA

lactate dehydrogenase A

- LUAD

lung adenocarcinoma

- NC

negative control

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

overall survival

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TGCA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Funding Statement

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

PZ and GY designed the study. PZ, ZL and GY performed the experiments. GY analyzed the data. PZ and GY confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. PZ wrote the paper, while ZL revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Second Provincial General Hospital (approval no. XYK20200511). All patients have signed written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung Cancer 2020: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasim F, Sabath BF, Eapen GA. Lung cancer. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL, Kwon R, Curran WJ, Jr, Wu YL, Paz-Ares L. Lung cancer: Current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 2017;389:299–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coudray N, Ocampo PS, Sakellaropoulos T, Narula N, Snuderl M, Fenyö D, Moreira AL, Razavian N, Tsirigos A. Classification and mutation prediction from non-small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat Med. 2018;24:1559–1567. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0177-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553:446–454. doi: 10.1038/nature25183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhtar-Danesh N, Akhtar-Danseh GG, Seow HY, Shakeel S, Finley C. Trends in survival based on treatment modality in non-small cell lung cancer patients: A population-based study. Cancer Invest. 2019;37:355–366. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2019.1653465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lind L, Sandström H, Wahlin A, Eriksson M, Nilsson-Sojka B, Sikström C, Holmgren G. Localization of the gene for congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type III, CDAN3, to chromosome 15q21-q25. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:109–112. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homma S, Shimada T, Hikake T, Yaginuma H. Expression pattern of LRR and Ig domain-containing protein (LRRIG protein) in the early mouse embryo. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ługowska A, Hetmańczyk-Sawicka K, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Fogtman A, Cieśla J, Purzycka-Olewiecka JK, Sitarska D, Płoski R, Filocamo M, Lualdi S, et al. Gene expression profile in patients with Gaucher disease indicates activation of inflammatory processes. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6060. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42584-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon IK, Kim HK, Kim YK, Song IH, Kim W, Kim S, Baek SH, Kim JH, Kim JR. Exploration of replicative senescence-associated genes in human dermal fibroblasts by cDNA microarray technology. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagasawa A, Kudoh J, Noda S, Mashima Y, Wright A, Oguchi Y, Shimizu N. Human and mouse ISLR (immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat) genes: Genomic structure and tissue expression. Genomics. 1999;61:37–43. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasawa A, Kubota R, Imamura Y, Nagamine K, Wang Y, Asakawa S, Kudoh J, Minoshima S, Mashima Y, Oguchi Y, et al. Cloning of the cDNA for a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily (ISLR) containing leucine-rich repeat (LRR) Genomics. 1997;44:273–279. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizutani Y, Kobayashi H, Iida T, Asai N, Masamune A, Hara A, Esaki N, Ushida K, Mii S, Shiraki Y, et al. Meflin-positive cancer-associated fibroblasts inhibit pancreatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5367–5381. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Zhao W, Sun M. An analysis regarding the association between the ISLR gene and gastric carcinogenesis. Front Genet. 2020;11:620. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SA, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi BV, Varambally S. UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19:649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Győrffy B. Survival analysis across the entire transcriptome identifies biomarkers with the highest prognostic power in breast cancer. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:4101–4109. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Győrffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lánczky A. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonna S, Subramaniam DS. Molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): An update. Discov Med. 2019;27:167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao H, Liang Y, Kang L, Xiao Y, Yu T, Wan R. miR4543p inhibits nonsmall cell lung cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by targeting TGFB2. Oncol Rep. 2021;45:67. doi: 10.3892/or.2021.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Zhang L, Meng G, Wang Q, Lv X, Zhang J, Li J. Circular RNAs: Pivotal molecular regulators and novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2875–2889. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-03045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu H, Li SB. Role of LINC00152 in non-small cell lung cancer. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020;21:179–191. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1900312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Tang Y, Sheng X, Tian Y, Deng M, Du S, Lv C, Li G, Pan Y, Song Y, et al. Secreted stromal protein ISLR promotes intestinal regeneration by suppressing epithelial Hippo signaling. EMBO J. 2020;39:e103255. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi H, Gieniec KA, Wright JA, Wang T, Asai N, Mizutani Y, Lida T, Ando R, Suzuki N, Lannagan TR, et al. The balance of stromal BMP signaling mediated by GREM1 and ISLR drives colorectal carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1224–1239. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milano A, Mazzetta F, Valente S, Ranieri D, Leone L, Botticelli A, Onesti CE, Lauro S, Raffa S, Torrisi MR, et al. Molecular detection of EMT markers in circulating tumor cells from metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients: Potential role in clinical practice. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) 2018;2018:3506874. doi: 10.1155/2018/3506874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu G, Meng L, Yuan D, Li K, Zhang Y, Dang C, Zhu K. MEG3/miR-21 axis affects cell mobility by suppressing epithelial mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;40:39–48. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a008656. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarskog LF, Selinger ES, Lieberman JA, Gilmore JH. Apoptotic proteins in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia: High Bax/Bcl-2 ratio without caspase-3 activation. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:109–115. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun LY, Li XJ, Sun YM, Huang W, Fang K, Han C, Chen ZH, Luo XQ, Chen YQ, Wang WT. LncRNA ANRIL regulates AML development through modulating the glucose metabolism pathway of AdipoR1/AMPK/SIRT1. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:127. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0879-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: Meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zambrano A, Molt M, Uribe E, Salas M. Glut 1 in cancer cells and the inhibitory action of resveratrol as a potential therapeutic strategy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3374. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang F, Ma W, Ma X, Shao Y, Yang W, Chen X, Li L, Wang J. Propranolol inhibits glucose metabolism and 18F-FDG uptake of breast cancer through posttranscriptional downregulation of hexokinase-2. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:439–445. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.121327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao X, Huang X, Ye F, Chen B, Song C, Wen J, Zhang Z, Zheng G, Tang H, Xie X. The miR-34a-LDHA axis regulates glucose metabolism and tumor growth in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21735. doi: 10.1038/srep21735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Yan W, Collins MA, Bednar F, Rakshit S, Zetter BR, Stanger BZ, Chung I, Rhim AD, di Magliano MP. Interleukin-6 is required for pancreatic cancer progression by promoting MAPK signaling activation and oxidative stress resistance. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6359–6374. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1558-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browning L, Patel MR, Horvath EB, Tawara K, Jorcyk CL. IL-6 and ovarian cancer: Inflammatory cytokines in promotion of metastasis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6685–6693. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S179189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bromberg J, Wang TC. Inflammation and cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 complete the link. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Y, Li W, Liu R, Guo Q, Li J, Bao Y, Zheng H, Jiang S, Hua B. Norcantharidin inhibits IL-6-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition via the JAK2/STAT3/TWIST signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;38:1224–1232. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Wang S, Su J, Chu G, You H, Chen Z, Sun H, Chen B, Zhou M. Interleukin-32α inactivates JAK2/STAT3 signaling and reverses interleukin-6-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and metastasis in pancreatic cancer cells. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:4225–4237. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S103581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Pu T, Yin L, Li Q, Liao CP, Wu BJ. MAOA-mediated reprogramming of stromal fibroblasts promotes prostate tumorigenesis and cancer stemness. Oncogene. 2020;39:3305–3321. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee HM, Sia AP, Li L, Sathasivam HP, Chan MS, Rajadurai P, Tsang CM, Tsao SW, Murray PG, Tao Q, et al. Monoamine oxidase A is down-regulated in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6115. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.