Abstract

Stimuli-responsive, on-demand release of drugs from drug-eluting depots could transform the treatment of many local diseases, providing intricate control over local dosing. However, conventional on-demand drug release approaches rely on locally implanted drug depots, which become spent over time and cannot be refilled or reused without invasive procedures. New strategies to noninvasively refill drug-eluting depots followed by on-demand release could transform clinical therapy. Here we report an on-demand drug delivery paradigm that combines bioorthogonal click chemistry to locally enrich protodrugs at a prelabeled site and light-triggered drug release at the target tissue. This approach begins with introduction of the targetable depot through local injection of chemically reactive azide groups that anchor to the extracellular matrix. The anchored azide groups then capture blood-circulating protodrugs through bioorthogonal click chemistry. After local capture and retention, active drugs can be released through external light irradiation. In this report, a photoresponsive protodrug was constructed consisting of the chemotherapeutic doxorubicin (Dox), conjugated to dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) through a photocleavable ortho-nitrobenzyl linker. The protodrug exhibited excellent on-demand light-triggered Dox release properties and light-mediated in vitro cytotoxicity in U87 glioblastoma cell lines. Furthermore, in a live animal setting, azide depots formed in mice through intradermal injection of activated azide-NHS esters. After i.v. administration, the protodrug was captured by the azide depots with intricate local specificity, which could be increased with multiple refills. Finally, doxorubicin could be released from the depot upon light irradiation. Multiple rounds of depot refilling and light-mediated release of active drug were accomplished, indicating that this system has the potential for multiple rounds of treatment. Taken together, these in vitro and in vivo proof of concept studies establish a novel method for in vivo targeting and on-demand delivery of cytotoxic drugs at target tissues.

Keywords: drug delivery, biorthogonal, stimuli-responsive, photocleavage, click chemistry

INTRODUCTION

Cytotoxic chemotherapy is limited in cancer by severe, sometimes life-threatening, side effects.1,2 Commonly used antitumor drugs often lack selectivity to malignant tissues and affect normal cell survival, eventually leading to unwanted toxicity.3 In recent years, targeted drug delivery and precise control of drug release has rapidly gained attention to deliver the drug with spatiotemporal control to minimize this broad systemic toxicity.

A number of approaches are being explored to selectively deliver therapeutics to tumors, but each has major limitations. Chemotherapeutics can be conjugated to active targeting molecules such as antibodies,4,5 peptides,6,7 or aptamers8,9 that bind to specific targets present on cancer cells. Unfortunately, these active targeting approaches suffer from the limited number of endogenous receptors, heterogeneity of antigen expression on the tumor surface, expression of the receptor antigen by normal tissues, and immunogenicity.10–15 Another approach takes advantage of endogenous tumor-specific stimuli such as lower tumor pH,16 unique redox chemistry,17 and elevated levels of enzymes such as esterases, proteases, and phosphatases18 to provide controlled therapeutics release. However, after successful targeting of therapeutics to the site of action by various approaches, release of “active” agents at the site of action is still a significant challenge because of the heterogeneity in the endogenous stimuli.19,20 Finally, external physical stimuli, including magnetic fields and light21 have been used for site specific drug targeting, which enable pinpoint control over the location and timing of drug presentation.

Recently, on-demand release has been combined with tumor targeting to achieve spatiotemporal delivery of the drugs.22–24 In several applications, light has been used as an ideal external stimulus because it exhibits variable parameters that can be optimized for biological compliance and provides a great advantage to release a drug at an intended time and place.25 One light-mediated drug delivery approaches involves chemical modification of therapeutic drug to less toxic photocaged protodrugs and delivery to cells and tissues, where they are uncaged to their active forms by illuminating with light.22,26,27

Stimuli response release of drugs from local drug-eluting depots could be a game-changer in drug delivery, but a conventional depot’s payload becomes exhausted over time and cannot be reused or refilled without invasive procedures. In order to address these challenges, our lab recently developed refillable drug depots, which enable noninvasive refilling of local depots through systemic circulation.28–32 Refillable depots present several significant improvements over direct injection or implantation of conventional drug-eluting depots. First, drug-eluting depots become useless when spent and cannot be refilled if implanted at inaccessible sites. Refillable depots provide repeated release of drugs, potentially months and years after implantation. Second, refillable depots enable increasing elution times by multiple half-lives without requiring exponential increases in drug concentrations. Third, refillable depots provide for temporal control over drug release, enabling one drug to follow another in sequence over the span of weeks or for the depot to be implanted during a tumor biopsy and only refilled after further analysis. Finally, refillable depots enable the drug identity or drug dose to be changed based on poor disease response or unexpected toxicity. To address the challenge of creating refillable depots intra-tumorally, we recently reported that intratumoral injection of the water-soluble sulfo-NHS activated esters of click chemistry motifs will anchor click groups in the tumor.32,33 In turn, the anchored click motifs create depots that can be targeted by systemically circulating small molecules modified with a complementary click motif.

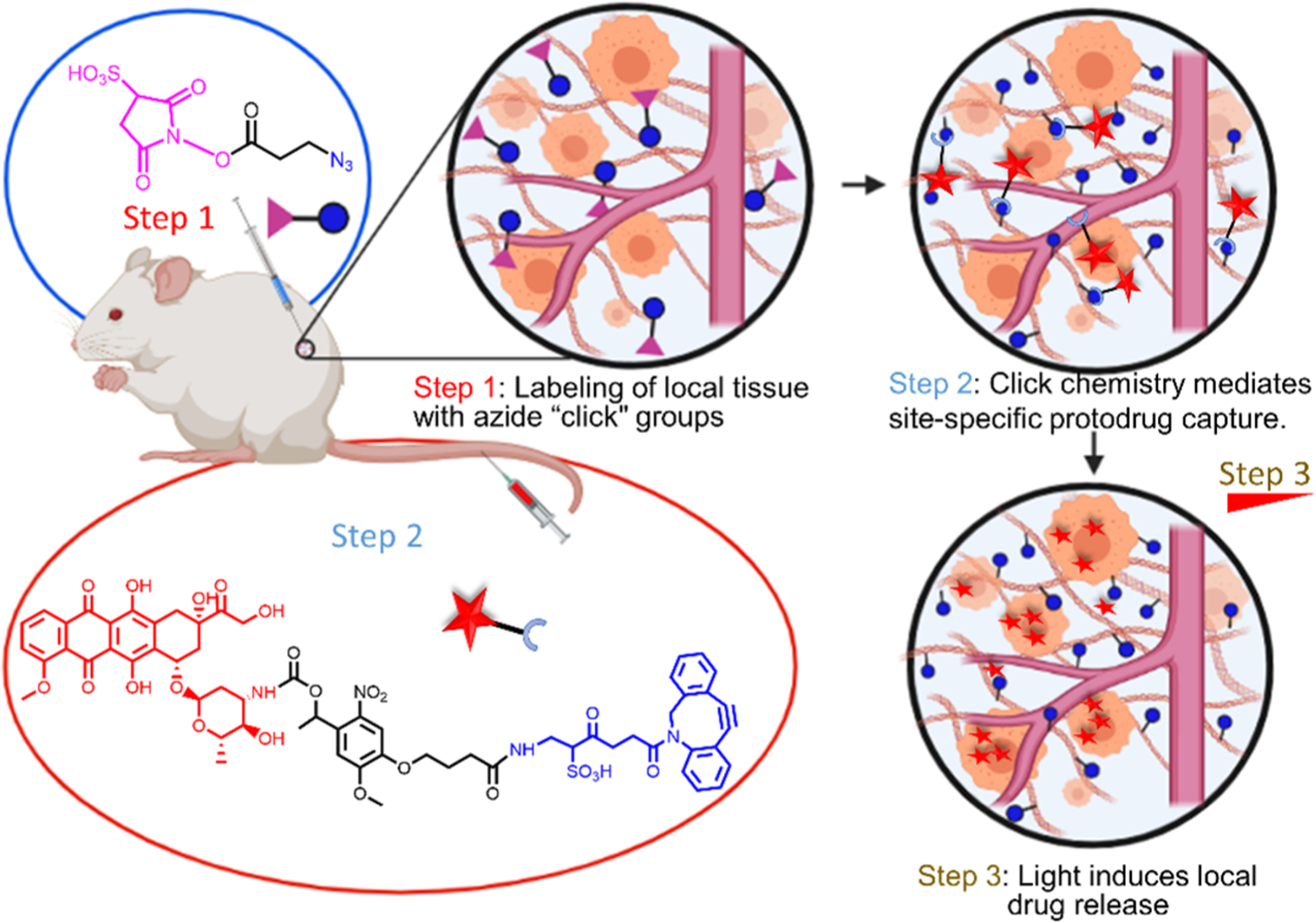

In this study, we exploited the protodrug approach and aimed to develop a protodrug that can chemically react with in vivo injected azide depots and release active drug upon light irradiation. To this purpose, doxorubicin (Dox) was converted into a model protodrug by conjugating doxorubicin to the click partner DBCO through the photo cleavable linker ortho-nitrobenzyl (ONB). ONB has been extensively used in several studies for this purpose.23,24 We utilized strain promoted azide alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) “click” chemistry to achieve site-specific targeting. Our approach is illustrated schematically in Scheme 1, and involves 3 steps: (1) direct injection of azide click (N3) groups to the site of interest to create a targetable depot; (2) systematic administration and capture of the protodrug at the azide injection site by bioorthogonal click chemistry; and (3) light-triggered release of the active drug from the captured protodrug. In this approach, the site-specific targeting is achieved through the chemical reactivity of azides and DBCO and subsequent drug release is mediated by external light stimuli. We demonstrate the synthesis of a doxorubicin-ortho-nitrobenzyl-DBCO (Dox-ONB-DBCO) protodrug. The developed protodrug exhibited excellent in vitro light-mediated drug release properties and cytotoxic effects in U87 glioblastoma cells. Upon systemic injection, the protodrug was captured by the in vivo azide depots via bioorthogonal click chemistry in a site selective manner. In vivo fluorescence imaging showed that the captured protodrug was only released upon light irradiation in vivo and no drug release was observed in the absence of light. Finally, the depot could be refilled and drug released over multiple cycles. We believe that the combination of bioorthogonal click-chemistry-mediated in vivo active targeting strategy and light-triggered release of the active drug from the depot has the potential to achieve the precise targeting and controlled release of the therapeutic drugs without relying on endogenous parameters, thereby reducing off-target toxicity for various applications including cancer therapy.

Scheme 1. Bioorthogonal Click-Chemistry-Mediated Drug Targeting of Tissues and Photo-controlled On-Demand Drug Releasea.

aStep 1: injections of activated NHS esters anchor azide molecules to tissue ECM to create a target depot. Step 2: intravascular administration of photolabile protodrug allows selective capture and display at azide depots by bioorthogonal click chemistry. Step 3: On-demand release of the drug upon light irradiation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Characterization of 6 (Dox-ONB-DBCO).

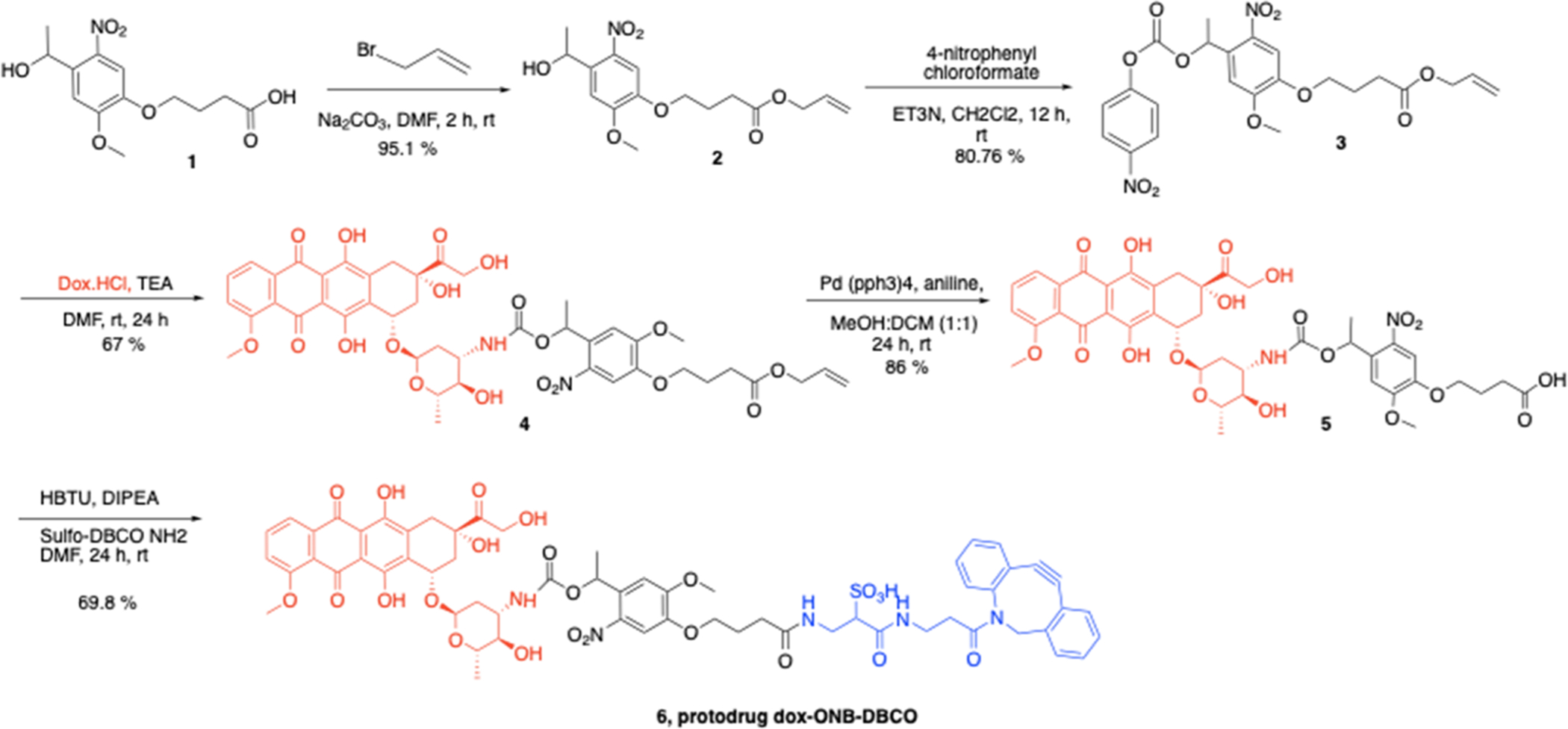

We constructed the Dox-ONB-DBCO protodrug as shown in Figure 1. The synthesis of the protodrug starts with commercially available nitroveratryl carboxylic acid 1. Compound 1 was allylated with allyl bromide to yield the allyl carboxylic ester 2. Compound 2 was converted to the p-nitrophenyl carbonate 3, which was further reacted with doxorubicin to generate photocaged doxorubicin carbamate 4. Cleavage of the allyl protecting groups in compound 4 gave the doxorubicin-ONB-carboxylate 5, which could be coupled with sulfo-DBCO-NH2 to generate the final Dox-ONB-DBCO conjugate (6).

Figure 1.

Synthesis scheme of protodrug 6 (Dox-ONB-DBCO).

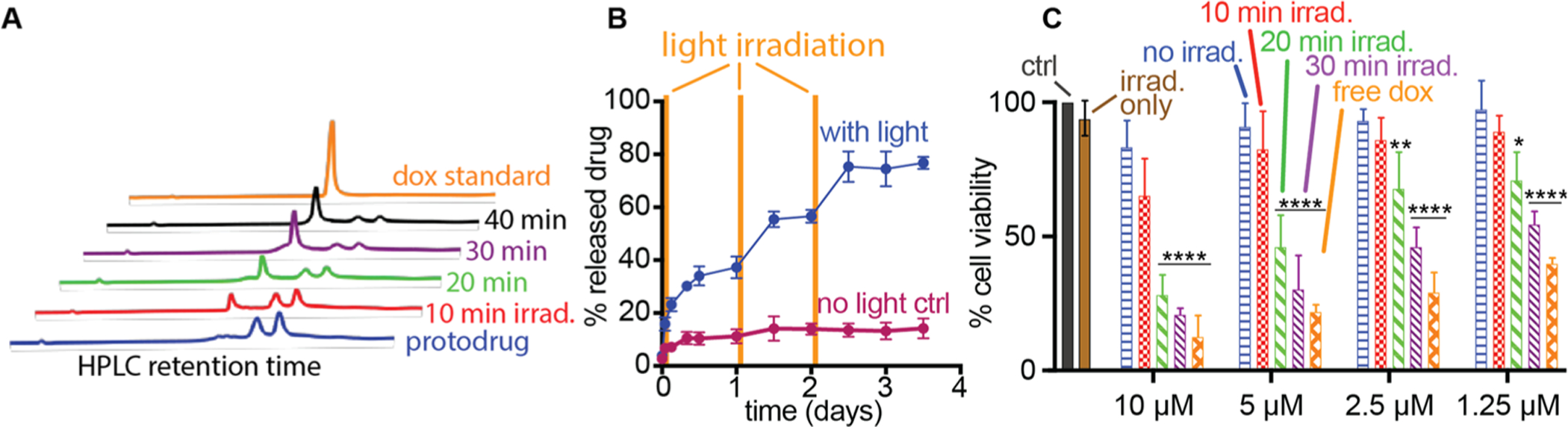

The preliminary assessment of the photolytic conversion of protodrug 6 to “active” Dox was investigated using HPLC under 405 nm light. The peaks corresponding to the Dox-ONB-DBCO conjugate disappeared, with a concomitant increase in the intensity of a peak with the same retention time as doxorubicin. A nearly full conversion of Dox-ONB-DBCO to free doxorubicin was achieved within 30 min of light irradiation (Figure 2A). These results indicate that the active Dox can be released from Dox-ONB-DBCO by light irradiation in a time dependent fashion.

Figure 2.

Doxorubicin protodrug 6 efficiently releases cytotoxic drug with light. (A) Time evolution of the HPLC spectra of a solution of 6 (200 μM in PBS) during photolysis (405 nm, 10 mW/cm2). Free Dox (200 μM), dissolved in PBS, was used to confirm clean photolysis of 6 to release “active” Dox. HPLC spectra were observed by a UV detector at 485 nm and conditions described in the Materials and Methods. (B) In vitro release kinetics of doxorubicin from doxorubicin protodrug covalently conjugated to alginate gels in PBS. No light irradiation (maroon), UV irradiation (blue) with light irradiation at 0, 24, and 48 h (yellow bars). (C) Cell viability (relative percentage) data observed for U87 glioblastoma cells treated with light-irradiated protodrug 6 and compared to no treatment, irradiation without protodrug, and protodrug without irradiation negative controls or free doxorubicin positive control as measured by the MTT assay. Statistical significance signified by * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.0001 against all three negative controls (no treatment, irradiation only, protodrug only) by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons testing. See Supplementary Tables S2–S5 for full statistical significance testing.

To further assess the potential of light-stimulated drug release, doxorubicin protodrugs were conjugated to solid support in the form for calcium-cross-linked azide-displayed alginate gel. The alginate gels conjugated to Dox-ONB-DBCO were placed in dialysis tubes and exposed to 405 nm UV irradiation for 30 min at 0, 24, and 48 h with nonirradiated samples serving as controls. Light irradiation of hydrogels released 37.3 ± 5.8% doxorubicin after the first irradiation, whereas less than 11.2% ± 3.8% doxorubicin was released from nonirradiated gels. After the second and third irradiation, the cumulative drug release increased to 56.60% ± 3.4% and 74.52% ± 9.2%, respectively, while nonirradiated samples barely increased to 13.17% ± 4.53% and 14.79% ± 5.3%, respectively (Figure 2B). These results demonstrated that the release of doxorubicin could be regulated by light irradiation, which enabled on-demand delivery of the active drug at site of interest while minimizing the premature release of the drug.

We next assessed the cytotoxic activity of protodrug 6 with and without light treatment against the human glioblastoma U87 cell line. As anticipated, neither a 30 min laser irradiation nor a 24 h incubation of the protodrug with cells caused cytotoxicity on their own, even at 10 μM protodrug concentrations. In contrast, the positive control, unmodified free doxorubicin, displayed potent cytotoxicity at low concentrations. Irradiation of the protodrug with light for 10, 20, and 30 min demonstrated a well-controlled dose response both in terms of protodrug concentration and irradiation duration with a 30 min irradiation of the protodrug demonstrating similar cytotoxicity to free drug.

Taken together, these results demonstrated that the photolabile doxorubicin protodrug is nontoxic on its own but efficiently releases cytotoxic therapy upon irradiation with light in solution and on a solid support.

In Vivo Targeting and Photocontrolled Release of Active Doxorubicin.

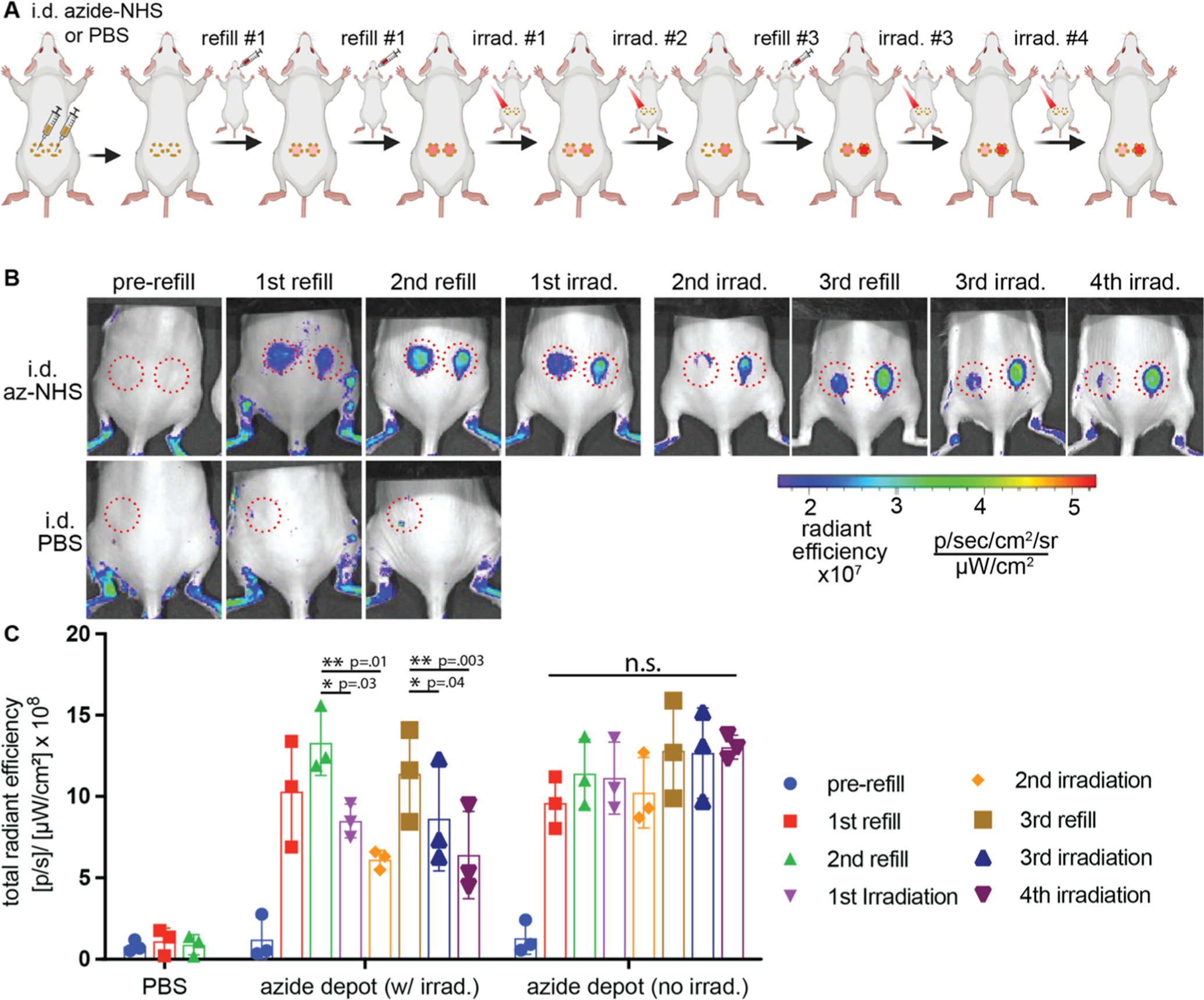

To validate our approach in vivo, we created intradermal depots of azides in both flanks of CD1 through direct intradermal injection of azide-NHS (4.7 μmol).33 Next, Dox-ONB-DBCO was administered i.v. and live animal fluorescence imaging was utilized to track the in vivo targeting of protodrug (Figure 3). As doxorubicin has an inherent fluorescence, we utilized IVIS imaging to validate protodrug capture from the Dox fluorescence observed at the azide-NHS/PBS injection sites. Twenty-four hours after the first refill, IVIS imaging of the animals bearing azide depots showed the Dox fluorescence signal at the site of azide depots. No signal was observed at the site of PBS, demonstrating that accumulation of protodrug was selective at azide depots through click chemistry. Quantification of Dox fluorescent signal at the azide depots resulted in significantly higher protodrug accumulation to PBS injected mice (Figure 3C). A second refill of protodrug resulted in a further increase in the Dox fluorescent signal at the azide depots and while no Dox signal was observed at the PBS injection site.

Figure 3.

Click-chemistry-mediated in vivo targeting of i.v. administered Dox-ONB-DBCO by ECM-anchored azide depots and phototriggered release of Dox. (A) Timeframe of the experimental design. Mice were injected intradermally with azide-NHS (50 μL of 0.1 M) or PBS in both the flanks. After depot formation, successive rounds of refills with protodrug 6 (i.v., Dox-ONB-DBCO, 10 mg/kg dose) and light irradiation (405 nm, 10 mW/cm2, 30 min) were performed and doxorubicin fluorescence was quantified by IVIS imaging. The full experimental timeline can be found in Supplementary Table 1. (B) Representative images and (C) quantitation of click-mediated protodrug capture and light-mediated drug release at intradermal depot sites (red circles). Samples show mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was measured using a paired, one-tailed Student’s t test and represented as *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. N = 3. Full images of all mice can be found im Figure S3. Autofluorescence seen in the leg regions is due to incomplete shaving of the fur.

After successful targeting of the protodrug at the azide depots, as a next step, we validated the light-triggered on-demand release of free Dox from the azide depot. Upon 405 nm light irradiation (10 mW/cm2) on the left flank azide depot for 30 min, the decay of the fluorescence intensity was observed in IVIS imaging after 24 h of photo irradiation. In contrast, no signal decay was observed in a nonirradiated control depot, directly demonstrating the process of the drug release in response to light irradiation. A quantitative analysis of Dox fluorescence decay at the depot was investigated in Figure 3C. The fluorescence signal had a decay of 36% within the first day of first irradiation, and 53% after the second irradiation demonstrating that Dox was released in response to light irradiation in a controlled manner. No fluorescence decrease was observed at nonirradiated azide depots. To evaluate the possibility of photobleaching of the Dox, protodrug in PBS was irradiated with the same conditions as in vivo irradiation. Quantification of the fluorescence signal from the protodrug sample before and after irradiation showed no decay in the fluorescence, demonstrating that the observed decay of the Dox signal in mice is due to actual release of the Dox from the depot and not the photobleaching (Figure S4). This semiquantitative analysis proved that the captured protodrug released active Dox in the depot upon light irradiation in controlled fashion.

To test the efficiency of the azide depot to capture the next rounds of refills and release the active drug, a third refill of the protodrug was administered and an increase in fluorescence was observed at both the azide depots, confirmed by the IVIS imaging. The left flank azide depot was irradiated with light for two rounds of 30 min after a third refill. The third round of irradiation elicited a similar trend of diminishment in Dox signal as seen in the first and second rounds under IVIS imaging. The Dox signal was diminished (25%) after the third round of light irradiation, and this effect was further enhanced (to 44%) with a fourth round of photo irradiation. No significant signal reduction was observed in nonlight treated control right flanks. These experiments demonstrate that the ECM anchored azide depot could serve as a target depot to capture the systemically circulating protodrug up to several refills and release the active drug molecules from the depot with response to light irradiation in a controlled manner. Due to the covalent, nonreversible nature of the click chemistry, a small fraction of the azides is consumed with every refill. In previous studies, intradermal depots captured roughly 2% of the administered dose, while intratumoral sites were more efficient, capturing ~8%. Under these conditions, a 2% (94 nanomoles) capture efficiency capture would provide for 50 refills. However, significant improvements in the theoretical refill numbers could be gained from increasing the azide-sNHS concentration and volume.

In conclusion, we have reported an efficient strategy for in vivo drug targeting and controlled release of the active drug at the target site based on the combination of two approaches: bioorthogonal click chemistry for in vivo targeting and light-triggered drug release at the target site. A photolabile Dox protodrug conjugated to DBCO through a photocleavable linker (Dox-ONB-DBCO) was synthesized. The developed protodrug released active free Dox upon light irradiation and showed excellent cytotoxic effects against U87 cells. Further, in vivo validation of our system demonstrated that i.v. administered Dox-ONB-DBCO localized selectively into the azide depots that were created by intradermal injection of azide-NHS esters as reported previously. These azide depots repeatedly captured systemically circulating protodrug through azide-DBCO “click” chemistry and served a reservoir to hold the drug molecules at the desired site. Finally, upon photo irradiation (405 nm), the “active” drug was released in a controlled fashion from the azide depot. Thus, our system enables in vivo local presentation of therapeutics and light-mediated on-demand delivery at the desired sites without depending on the biological properties which are highly heterogeneous. Although, in this study, we used visible blue light as an external trigger for drug release as a proof of concept, the system could be further modified to be operated at longer wavelengths that are able to penetrate farther into tissues. This methodology opens new ways for the future design of site selective and on-demand drug delivery systems.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the NC State veterinary staff for proper care of animals used in experiments and valuable resources on training. Mass spectrometry data and NMR data were obtained at the NC State Molecular, Education, Technology and Research Innovation Center (METRIC). The project described was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant award number UL1TR002489 and through the National Cancer Institute through grant award number R21CA246414, by the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center’s University Cancer Research Fund, by a Faculty Research and Professional Development Grant from North Carolina State University, and by start-up funds from the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University. Some figures created with Biorender.com.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00535.

Synthetic protocols and details for all compounds; 1H and 13C NMR spectra for compounds; LC–MS traces for compounds; doxorubicin calibration curve; IVIS images of all three mice; photobleaching of doxorubicin; full statistical significance testing of results (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00535

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Sandeep Palvai, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States.

Christopher T. Moody, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States; Comparative Medicine Institute, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States

Sharda Pandit, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States; Comparative Medicine Institute, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States.

Yevgeny Brudno, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States; Comparative Medicine Institute, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, United States; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Schirrmacher V From Chemotherapy to Biological Therapy: A Review of Novel Concepts to Reduce the Side Effects of Systemic Cancer Treatment (Review). Int. J. Oncol 2019, 54 (2), 407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Curigliano G; Cardinale D; Suter T; Plataniotis G; de Azambuja E; Sandri MT; Criscitiello C; Goldhirsch A; Cipolla C; Roila F Cardiovascular Toxicity Induced by Chemotherapy, Targeted Agents and Radiotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol 2012, 23, vii155–vii166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Chidambaram M; Manavalan R; Kathiresan K Nanotherapeutics to Overcome Conventional Cancer Chemotherapy Limitations. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci 2011, 14 (1), 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Alley SC; Okeley NM; Senter PD Antibody–Drug Conjugates: Targeted Drug Delivery for Cancer. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14 (4), 529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Mullard A Maturing Antibody–Drug Conjugate Pipeline Hits 30. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2013, 12 (5), 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ma L; Wang C; He Z; Cheng B; Zheng L; Huang K Peptide-Drug Conjugate: A Novel Drug Design Approach. Curr. Med. Chem 2017, 24 (31), 3373–3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Cox N; Kintzing JR; Smith M; Grant GA; Cochran JR Integrin-Targeting Knottin Peptide-Drug Conjugates Are Potent Inhibitors of Tumor Cell Proliferation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55 (34), 9894–9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Powell Gray B; Kelly L; Ahrens DP; Barry AP; Kratschmer C; Levy M; Sullenger BA Tunable Cytotoxic Aptamer-Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115 (18), 4761–4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Dou X-Q; Wang H; Zhang J; Wang F; Xu G-L; Xu C-C; Xu H-H; Xiang S-S; Fu J; Song H-F Aptamer-Drug Conjugate: Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin in a HER3 Aptamer-Functionalized Liposomal Delivery System Reduces Cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Nanomed 2018, 13, 763–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Teicher BA; Chari RVJ Antibody Conjugate Therapeutics: Challenges and Potential. Clin. Cancer Res 2011, 17 (20), 6389–6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pimm MV Drug-Monoclonal Antibody Conjugates for Cancer Therapy: Potentials and Limitations. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst 1988, 5 (3), 189–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Joubert N; Beck A; Dumontet C; Denevault-Sabourin C Antibody-Drug Conjugates: The Last Decade. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13 (9), 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hafeez U; Parakh S; Gan HK; Scott AM Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2020, 25 (20), 4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chudasama V; Maruani A; Caddick S Recent Advances in the Construction of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Nat. Chem 2016, 8 (2), 114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Allen TM Ligand-Targeted Therapeutics in Anticancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2 (10), 750–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Firestone RA; Willner D; Hofstead SJ; King HD; Kaneko T; Braslawsky GR; Greenfield RS; Trail PA; Lasch SJ; Henderson AJ; Casazza AM; Hellström I; Hellström KE Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of the Immunoconjugate BR96-Dox. J. Controlled Release 1996, 39 (2), 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Erickson HK; Widdison WC; Mayo MF; Whiteman K; Audette C; Wilhelm SD; Singh R Tumor Delivery and in Vivo Processing of Disulfide-Linked and Thioether-Linked Antibody-Maytansinoid Conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem 2010, 21 (1), 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Moldenhauer G; Salnikov AV; Lüttgau S; Herr I; Anderl J; Faulstich H Therapeutic Potential of Amanitin-Conjugated Anti-Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule Monoclonal Antibody against Pancreatic Carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 2012, 104 (8), 622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Rao NV; Ko H; Lee J; Park JH Recent Progress and Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Polymers for Cancer Therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 2018, 6, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zheng Y; Ji X; Yu B; Ji K; Gallo D; Csizmadia E; Zhu M; Choudhury MR; De La Cruz LKC; Chittavong V; Pan Z; Yuan Z; Otterbein LE; Wang B Enrichment-Triggered Prodrug Activation Demonstrated through Mitochondria-Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin and Carbon Monoxide. Nat. Chem 2018, 10 (7), 787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pirmoradi FN; Jackson JK; Burt HM; Chiao M A Magnetically Controlled MEMS Device for Drug Delivery: Design, Fabrication, and Testing. Lab Chip 2011, 11 (18), 3072–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Nani RR; Gorka AP; Nagaya T; Kobayashi H; Schnermann MJ Near-IR Light-Mediated Cleavage of Antibody-Drug Conjugates Using Cyanine Photocages. Angew. Chem 2015, 127 (46), 13839–13842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kong L; Askes SHC; Bonnet S; Kros A; Campbell F Temporal Control of Membrane Fusion through Photolabile PEGylation of Liposome Membranes. Angew. Chem 2016, 128 (4), 1418–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dcona MM; Mitra D; Goehe RW; Gewirtz DA; Lebman DA; Hartman MCT Photocaged Permeability: A New Strategy for Controlled Drug Release. Chem. Commun 2012, 48 (39), 4755–4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fan N-C; Cheng F-Y; Ho J-AA; Yeh C-S Photo-controlled Targeted Drug Delivery: Photocaged Biologically Active Folic Acid as a Light-Responsive Tumor-Targeting Molecule. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51 (35), 8806–8810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Shin WS; Han J; Kumar R; Lee GG; Sessler JL; Kim J-H; Kim JS Programmed Activation of Cancer Cell Apoptosis: A Tumor-Targeted Phototherapeutic Topoisomerase I Inhibitor. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 29018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tamura R; Balabanova A; Frakes SA; Bargmann A; Grimm J; Koch TH; Yin H Photoactivatable Prodrug of Doxazolidine Targeting Exosomes. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62 (4), 1959–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Brudno Y; Pezone MJ; Snyder TK; Uzun O; Moody CT; Aizenberg M; Mooney DJ Replenishable Drug Depot to Combat Post-Resection Cancer Recurrence. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Brudno Y; Silva EA; Kearney CJ; Lewin SA; Miller A; Martinick KD; Aizenberg M; Mooney DJ Refilling Drug Delivery Depots through the Blood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111 (35), 12722–12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Brudno Y; Desai RM; Kwee BJ; Joshi NS; Aizenberg M; Mooney DJ In Vivo Targeting through Click Chemistry. ChemMedChem 2015, 10 (4), 617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Moody CT; Palvai S; Brudno Y Click Cross-Linking Improves Retention and Targeting of Refillable Alginate Depots. Acta Biomater 2020, 112, 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Palvai S; Bhangu J; Akgun B; Moody CT; Hall DG; Brudno Y In Vivo Targeting Using Arylboronate/Nopoldiol Click Conjugation. Bioconjugate Chem 2020, 31 (10), 2288–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Adams MR; Moody CT; Sollinger JL; Brudno Y Extracellular-Matrix-Anchored Click Motifs for Specific Tissue Targeting. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2020, 17 (2), 392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.