Abstract

Background

Early identification of the occurrence of arrhythmia in patients with acute myocardial infarction plays an essential role in clinical decision-making. The present study attempted to use machine learning (ML) methods to build predictive models of arrhythmia after acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Methods

A total of 2084 patients with acute myocardial infarction were enrolled in this study. (All data is available on Github: https://github.com/wangsuhuai/AMI-database1.git). The primary outcome is whether tachyarrhythmia occurred during admission containing atrial arrhythmia, ventricular arrhythmia, and supraventricular tachycardia. All data is randomly divided into a training set (80%) and an internal testing set (20%). Apply three machine learning algorithms: decision tree, random forest (RF), and artificial neural network (ANN) to learn the training set to build a model, then use the testing set to evaluate the prediction performance, and compare it with the model built by the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk variable set.

Results

Three ML models predict the occurrence of tachyarrhythmias after AMI. After variable selection, the artificial neural network (ANN) model has reached the highest accuracy rate, which is better than the model constructed using the Grace variable set. After applying SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to make the model interpretable, the most important features are abnormal wall motion, lesion location, bundle branch block, age, and heart rate. Among them, RBBB (odds ratio [OR]: 4.21; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.42–7.02), ≥ 2 ventricular walls motion abnormal (OR: 3.26; 95% CI: 2.01–4.36) and right coronary artery occlusion (OR: 3.00; 95% CI: 1.98–4.56) are significant factors related to arrhythmia after AMI.

Conclusions

We used advanced machine learning methods to build prediction models for tachyarrhythmia after AMI for the first time (especially the ANN model that has the best performance). The current study can supplement the current AMI risk score, provide a reliable evaluation method for the clinic, and broaden the new horizons of ML and clinical research.

Trial registration Clinical Trial Registry No.: ChiCTR2100041960.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12911-021-01667-8.

Keywords: Machine learning, Arrhythmia, Acute myocardial infarction

Introduction

Admittedly, AMI is a clinically critical disease [1]. Recent studies have emphasized that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can reduce acute and long-term mortality [2]. However, the 1-year mortality rate for AMI patients reported by the Angiography Registry is still 10% [3]. Arrhythmia accompanying AMI is an important cause of worsening heart function and increased mortality [4–6]. Studies have confirmed that in patients undergoing PCI treatment, arrhythmia that occurred before and after the end of cardiac catheterization was associated with increased mortality [7]. As a result, identifying the risk factors of arrhythmia after AMI and predicting the occurrence of arrhythmia in AMI patients can arouse doctors' alertness and improve the prognosis of patients. In recent years, many studies have been concentrated on the risk factors of arrhythmia after AMI, including the clinical characteristics, coronary angiography results, and laboratory indicators [7–11]. However, the above studies are limited to a small number of factors and lack a comprehensive and multi-dimensional systematic evaluation of patients with arrhythmia in the acute phase of AMI. The GRACE risk score [1] is the most commonly used systematic assessment method for AMI patients, while it is mainly used to predict mortality, and the accuracy of predicting arrhythmia may not remain high. Therefore, establishing a predictive model of arrhythmia after AMI exerts an essential role in assisting clinicians in decision-making. Traditional risk models are usually based on statistical methods, which can only linearly analyze several factors' relationships. Researchers will select variables in advance to artificially cause the loss of potential risk factors. In terms of complex diseases such as acute myocardial infarction, it has higher requirements for dealing with multi-factor and multi-level interactions.

As the most critical subset of artificial intelligence, ML has gradually become an important research method in medicine [12–14]. Through simulating human learning activities, ML automatically obtains information from big clinical data for learning [15, 16], effectively avoiding the limitations of human factors and variables in traditional analysis. ML has been successfully applied in various cardiovascular field aspects, including disease prediction [17–21] and diagnostic classification [22–24]. In recent years, research on ML in AMI has mainly focused on predicting patient mortality [25–28]. In the field of arrhythmia, ML is mainly used for classification [29, 30], but the related ML model of arrhythmia after AMI has not been explored. As a result, this study intends to apply machine learning algorithms, including decision tree, RF, and ANN to establish a model to predict tachyarrhythmia after AMI and compare the performance with the model-based by GRACE risk variable set.

Methods

Patient cohort

We retrospectively studied patients with acute myocardial infarction diagnosed in the cardiac care unit of the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University from January 2014 to January 2019. The guidelines define acute myocardial infarction as elevated Troponin I (TNI) (≥ 0.03 μg/L) or elevated Troponin I (TNT) (≥ 42 ng/L), accompanied by one of the following conditions: (1) Symptoms of myocardial ischemia; (2) New ischemic ECG changes: (3) Development of pathological Q waves; (4) Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality in a pattern consistent with an ischemic etiology; (5) Identification of a coronary thrombus by angiography.

All patients underwent three-dimensional echocardiography, coronary angiography, and 24-h Holter. Outcome events were defined as whether or not tachyarrhythmia occurred. Arrhythmic events include atrial arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and frequent atrial premature), ventricular arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular flutter, ventricular fibrillation, and frequent premature ventricular), supraventricular tachycardia. (All data is available on Github: https://github.com/wangsuhuai/AMI-database1.git).

Variable selection

We selected the risk factors for tachyarrhythmia after AMI identified in the previous study, and added some new risk factors as candidate variables, including demographics, admission baseline characteristics, laboratory characteristics, echocardiographic parameters, and angiography Features, a total of 45 variables (Table 1), all variables were collected immediately after hospitalization and before PCI. As some patients received emergency PCI, the 24-h Holter record includes data before and after PCI. We graded continuous variables and converted them into ordered categorical variables (see Additional file 1).

Table 1.

Variables for machine learning

| Category | Variables |

|---|---|

| Demographics and medical history | Age, sex, smoker, drinker, Pre-hypertension, Pre-diabetes Mellitus, Prior MI, Prior CI, Prior HF, Prior CHD |

| Baseline characteristics of admission | SBP, DBP, HR, Killip, NYHA |

| Laboratory characteristics | Pro-BNP, CRP, Total cholesterol, Triglyceride, HDL, LDL, Cr, K + , TNI, CK-MB, UGLU, DDP |

| Findings on ECG | P-R, QTc, BBB (LAFB, LPFB, LBBB, RBBB) |

| Echocardiographic parameters | LVEF, FS, E/A, Dt, LVEDD, IVST, LVPWT, LA, RA (up and down), RA (right and left), PA, Vpa, Vao, ventricular wall motion |

| Angiographic characteristics | LAD, LCX, RCA, LM, LAD + LCX, LAD + RCA, RCA + LCX, Triple vessels |

MI indicates myocardial infarction; CI, cerebral infarction; HF, heart failure; CHD, coronary heart disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; pro-BNP, pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; DDP, D dimer; Cr, creatinine; TNI, Troponin I; CK-MB, creatine Kinase Isoenzyme; UGLU, urine glucose; P-R, PR interval; QTc, QTc interval; BBB, bundle-branch-block; LAFB, left anterior branch block; LPFB, left posterior branch block; LBBB, left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; FS, fraction shortening; E/A, mitral valve peak velocity early diastolic filling (E wave) to peak velocity of late diastolic filling (A wave) ratio; Dt, E deceleration time; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; IVST, interventricular septum thickness; LVPWT, left ventricular posterior wall thickness; LA, left atrium diameter; RA (up and down), right atrium up and down diameter; RA (right and left), right atrium right and left diameter; PA, pulmonary artery internal dimension; Vpa, Pulmonary peak flow rate; Vao, Peak aortic velocity; LAD, left anterior descending; LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; LM, left main coronary artery

Machine learning

Feature selection

Feature selection is done after fine-tuning the hyperparameters defined as model parameters, which are assigned arbitrary values before the start of the learning process. During training, Random Forest generates several random decision trees, which are applied to a subset of the data. Random forest checks all the binary results of these decision trees and selects their results by majority voting. Based on the ranking of features with reduced Gini impurity, the degree of reduction in Gini impurity predicted when specific features are removed is calculated. This Gini impurity is then compared with the Gini impurity obtained by using all the characteristics, and this difference is regarded as the importance of the specific characteristic: the more the Gini impurity decreases, the more important the characteristic is. The specific parameters can be seen in Table 2. From this, we get the importance ranking of features. In addition, to make the ML model interpretable, we use the SHAP method to show the importance of features. In the end, we selected the top 15 variables, and the cutoff point was selected based on optimizing the predictive performance of the model with the fewest variables (feature importance ranking see Additional file 2).

Table 2.

RF parameters

| Criterion | Gini |

|---|---|

| Random state | 35 |

| Max depth | 3 |

| Min samples leaf | 6 |

| Max features | 40 |

| N estimators | 22 |

Model construction

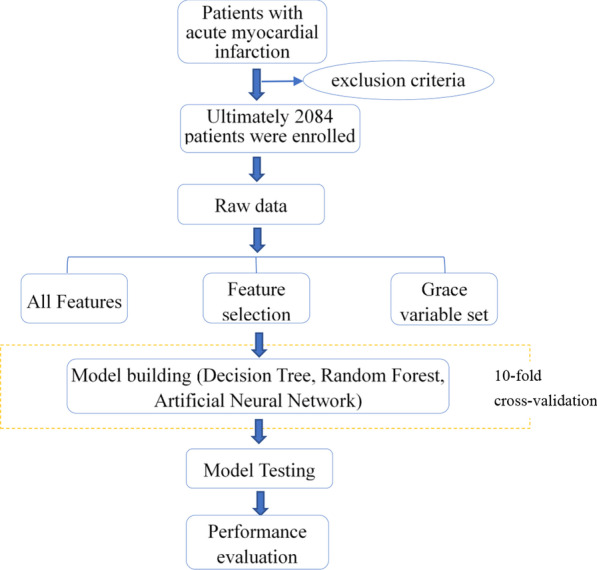

Predictive classifiers were developed based on data from the training set using 3 supervised ML methods: (1) Decision Tree, (2) RF, (3) ANN. We chose 80% as the training set and 20% as the testing set. We use the tenfold cross-validation technique on the training set. The dataset is randomly divided into 10 equal folds, each with approximately the same number of events; 10 validation experiments are then performed, with each fold used in turn as the validation set, and the remaining 9 folds as the training set. Then use the 20% testing set to evaluate model performance (Fig. 1, Additional file 3 describes the detailed data).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the process for evaluating the performance of ML methods

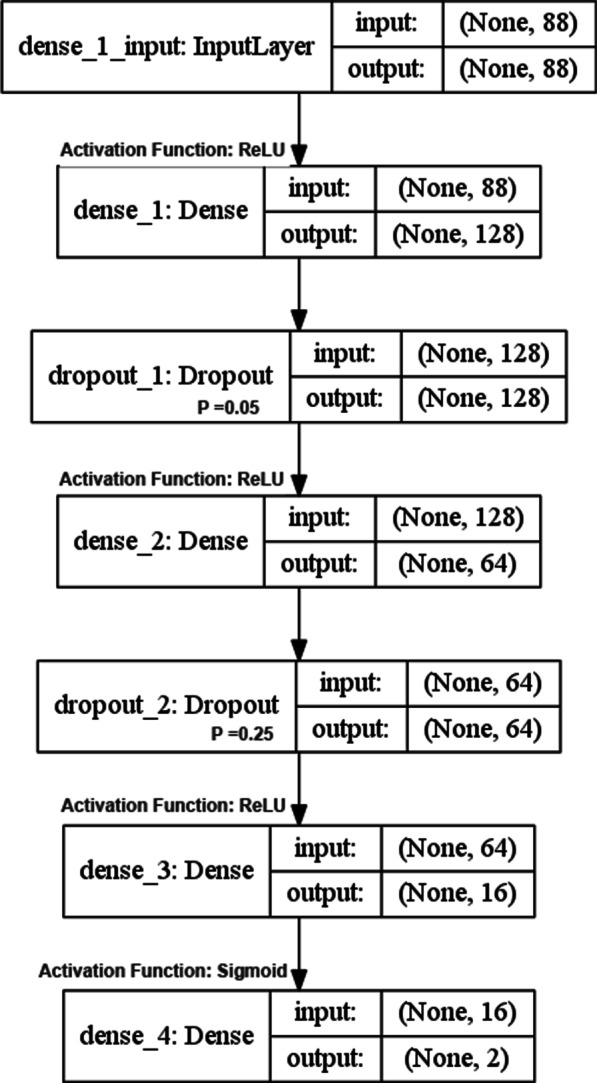

The artificial neural network architecture diagram is shown in Fig. 2. The first dense layer uses ReLU as the activation function, and the probability of dropout is 0.05; the second dense layer uses ReLU as the activation function, and the probability is 0.25; the third dense layer uses ReLU as the activation function, and the fourth dense layer uses Sigmoid As an activation function. The loss function is cross-entropy, and the optimization algorithm is RMSProp.

Fig. 2.

Artificial neural network architecture diagram

First, we feed all the variables into machine learning to build the prediction model. However, considering that it is difficult for doctors to consider all 45 variables in the actual clinical environment. To simplify the ML model for clinical use, a simplified model is derived from the complete model, which includes the top 15 variables selected based on the RF. Finally, to evaluate the ML model's clinical significance, we input the GRACE risk score variables into three ML algorithms for training to build the GRACE variable set model. The overall performance of the prediction model on the test set was assessed by calculation of accuracy, specificity, false-negative rate, false-positive rate, and the area under the curve (AUC) and the associated 95% CI. We drew receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of all models and used the Yoden index to get the best threshold of ROC curves. The ML techniques were implemented in the open-source Python 3.7 environment.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses and comparisons between clinically defined groups were performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (25th and 75th percentiles) and categorical variables as number and percentage. Baseline characteristics of groups were compared using unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney’s U-test for continuous variables and by chi-square test for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to determine the risk of important features of arrhythmia after AMI.A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Excluding patients with incomplete data records and prior arrhythmias, the study included 2084 patients with AMI, of whom 1224 had no arrhythmias and 860 had tachyarrhythmia (611 men and 249 women). Tables 3 and 4 summarizes the differences in demographics, baseline characteristics of admission, laboratory characteristics, echocardiographic parameters, and angiography features between the two groups. (* means P < 0.05, ** means P < 0.01). Details on all 45 features are available in Additional file 4.

Table 3.

Comparison of basic characteristics between the two groups

| Characteristics | Arrhythmia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1224) | Yes (n = 860) | P value | |

| Demographics and history | |||

| Age, years | 57.97 ± 11.38 | 61.68 ± 10.81 | < 0.001** |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 942 (76.96) | 611 (71.05) | 0.002** |

| Prior MI, n (%) | 86 (7.03) | 81 (9.42) | 0.048* |

| At admission | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 75 (66, 86) | 72 (62, 85) | < 0.001** |

| SBP, mmHg | 130 (117 ~ 150) | 127 (112 ~ 144) | < 0.001** |

| DBP, mmHg | 83.84 ± 15.86 | 79.59 ± 16.68 | < 0.001** |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Pro-BNP (pg/mL) | 1003.5 (420.0, 2207.0) | 1202.0 (482.0, 2641.5) | 0.003** |

| TNI (μg/L) | 19.810 (1.1, 50.0) | 30.785 (2.0, 54.0) | 0.001** |

| CK-MB (μg/L) | 74.0 (25.4, 161.6) | 91.5 (33.7, 190.6) | 0.001** |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.95 ± 1.15 | 1.82 ± 1.10 | 0.014* |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 75.88 ± 37.08 | 79.88 ± 42.88 | 0.027* |

| Findings on ECG | |||

| BBB, n (%) | < 0.001** | ||

| LAFB, n (%) | 214 (17.48) | 175 (20.35) | |

| LBBB, n (%) | 22 (1.80) | 19 (2.21) | |

| LPFB, n (%) | 49 (4.00) | 35 (4.07) | |

| RBBB, n (%) | 25 (2.04) | 51 (5.93) | |

| LAFB + RBBB, n (%) | 13 (1.06) | 27 (3.14) | |

| Q-Tc (ms) | 439 (418, 462) | 442 (418, 469) | 0.014* |

* means P < 0.05, ** means P < 0.01

Table 4.

Comparison of the results of echocardiography and PCI between the two groups

| Characteristics | Arrhythmia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1224) | Yes (n = 860) | P value | |

| Echocardiographic | |||

| LVEF (%) | 52.28 ± 9.04 | 51.17 ± 9.20 | 0.006** |

| RA (up and down), mm | 44.0 (42.0, 46.0) | 45.0 (42.0, 46.0) | 0.006** |

| RA (right and left), mm | 34.0 (32.0, 35.0) | 34.0 (32.0, 36.0) | 0.003** |

| Ventricular wall motion abnormal, n (%) | < 0.001** | ||

| ≥ 2 walls | 270 (22.06) | 213 (24.77) | |

| Anterior | 430 (35.13) | 217 (25.23) | |

| Apex | 19 (1.55) | 3 (0.35) | |

| Anteroseptal | 19 (1.55) | 2 (0.23) | |

| Posterior | 148 (12.09) | 135 (15.70) | |

| Inferior | 297 (24.26) | 268 (31.16) | |

| Angiographic | |||

| Lesions vessels, n (%) | < 0.001** | ||

| LAD | 262 (21.41) | 95 (11.05) | |

| LCX | 46 (3.76) | 20 (2.33) | |

| RCA | 78 (6.37) | 112 (13.02) | |

| LM | 38 (3.10) | 35 (4.07) | |

| LAD + LCX | 158 (12.91) | 64 (7.44) | |

| LAD + RCA | 198 (16.18) | 166 (19.30) | |

| RCA + LCX | 66 (5.39) | 60 (6.98) | |

| Triple vessels | 378 (30.88) | 308 (35.81) | |

* means P < 0.05, ** means P < 0.01

ML analysis

Variable selection

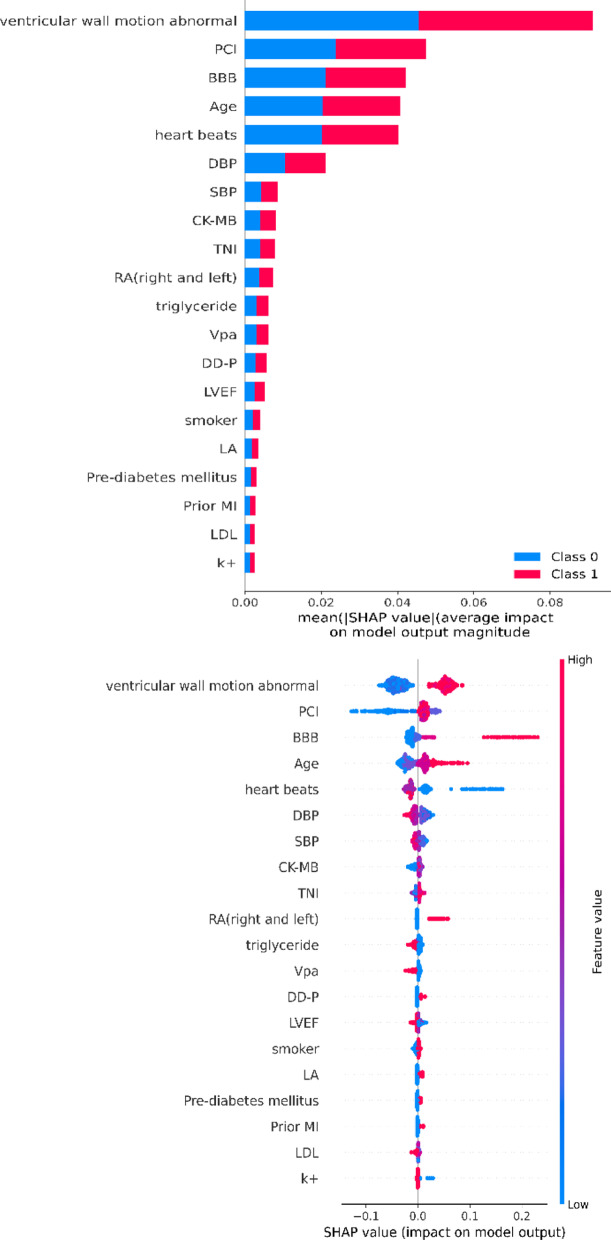

ML extracted top-15 feature-ranking with the random forest for further modeling. After applying SHAP to make the model interpretable, the most important features are abnormal wall motion, lesion location, bundle branch block, age, and heart rate (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Feature importance

Model evaluation and comparison

We use three ML algorithms to build a predictive model of tachyarrhythmia after AMI. Whether it is all variables, 15 important variables, or the GRACE variable set, ANN has better performance than the other two algorithms. The model constructed by the feature selection combined with the ANN algorithm has the best performance, with an accuracy rate of 0.668 (95% CI, 0.621–0.714), which is higher than the Grace variable set model, with an accuracy of 0.644 (95% CI, 0.615–0.673). Table 5 summarizes the accuracy, specificity, false-negative rate, false-positive rate, and the area under the curve (AUC) and the associated 95% CI of each model.

Table 5.

Predictive performance of all machine learning models

| Models | Accuracy | AUC | Specificity | False negative rate | False positive rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All features | |||||

| Decision tree | 0.627 (95% CI, 0.598–0.656) | 0.575 (95% CI, 0.545–0.603) | 0.963 | 0.915 | 0.037 |

| Random forest | 0.646 (95% CI, 0.617–0.675) | 0.596 (95% CI, 0.567–0.652) | 0.869 | 0.755 | 0.131 |

| Artificial neural network | 0.650 (95% CI, 0.607–0.675) | 0.625 (95% CI, 0.579–0.672) | 0.861 | 0.665 | 0.139 |

| Feature selection | |||||

| Decision tree | 0.642 (95% CI, 0.613–0.671) | 0.592 (95% CI, 0.563–0.648) | 0.963 | 0.915 | 0.037 |

| Random forest | 0.648 (95% CI, 0.601–0.695) | 0.605 (95% CI, 0.558 –0.652 | 0.913 | 0.802 | 0.087 |

| Artificial neural network | 0.668 (95% CI, 0.621–0.714) | 0.654 (95% CI, 0.625–0.683) | 0.922 | 0.755 | 0.078 |

| Grace variable sets | |||||

| Decision tree | 0.622 (95% CI, 0.576–0.668) | 0.554 (95% CI, 0.508–0.601) | 0.973 | 0.927 | 0.027 |

| Random forest | 0.627 (95% CI, 0.598–0.656) | 0.575 (95% CI, 0.545–0.603) | 0.966 | 0.904 | 0.034 |

| Artificial neural network | 0.644 (95% CI, 0.615–0.673) | 0.594 (95% CI, 0.565–0.65) | 0.892 | 0.778 | 0.108 |

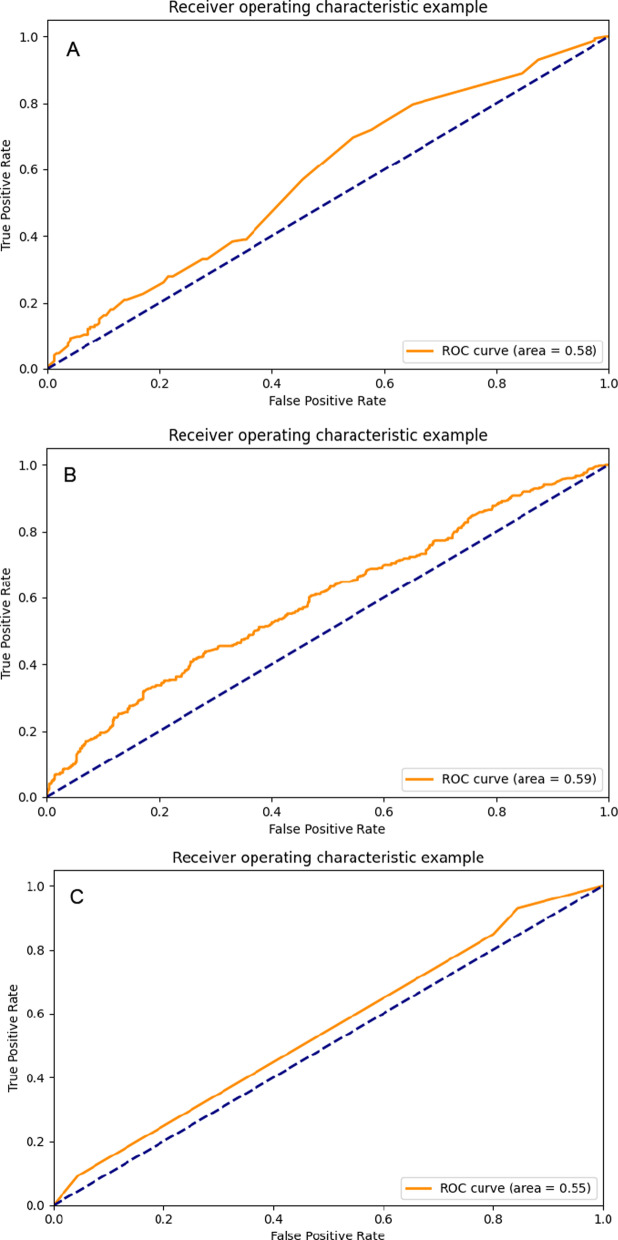

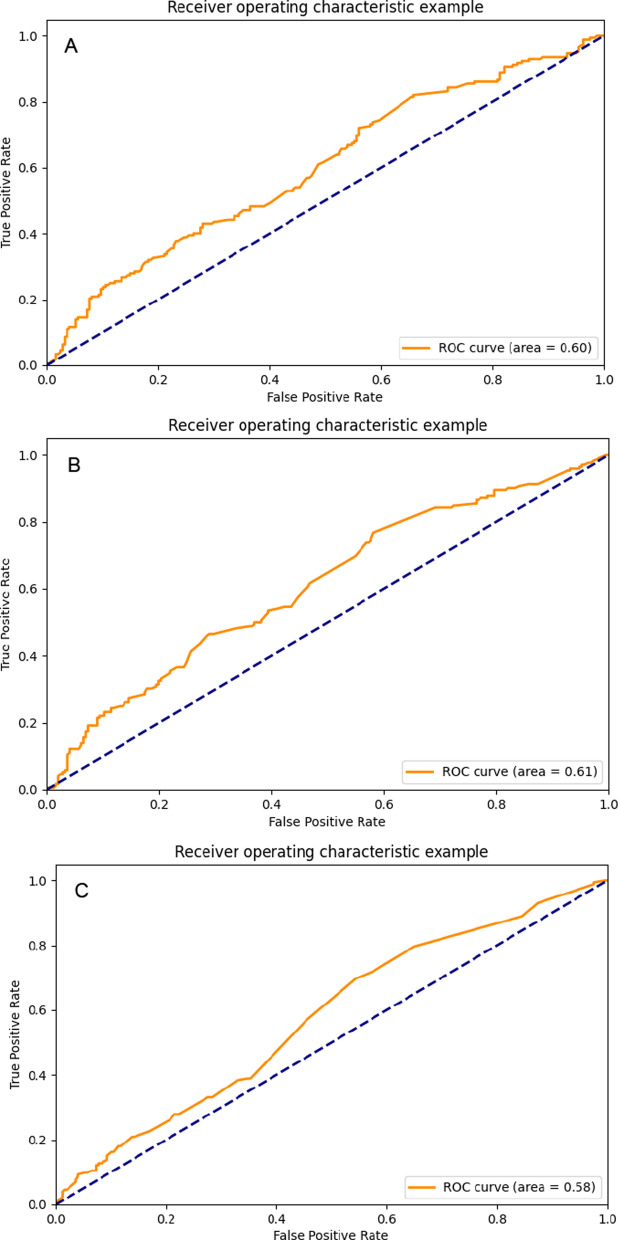

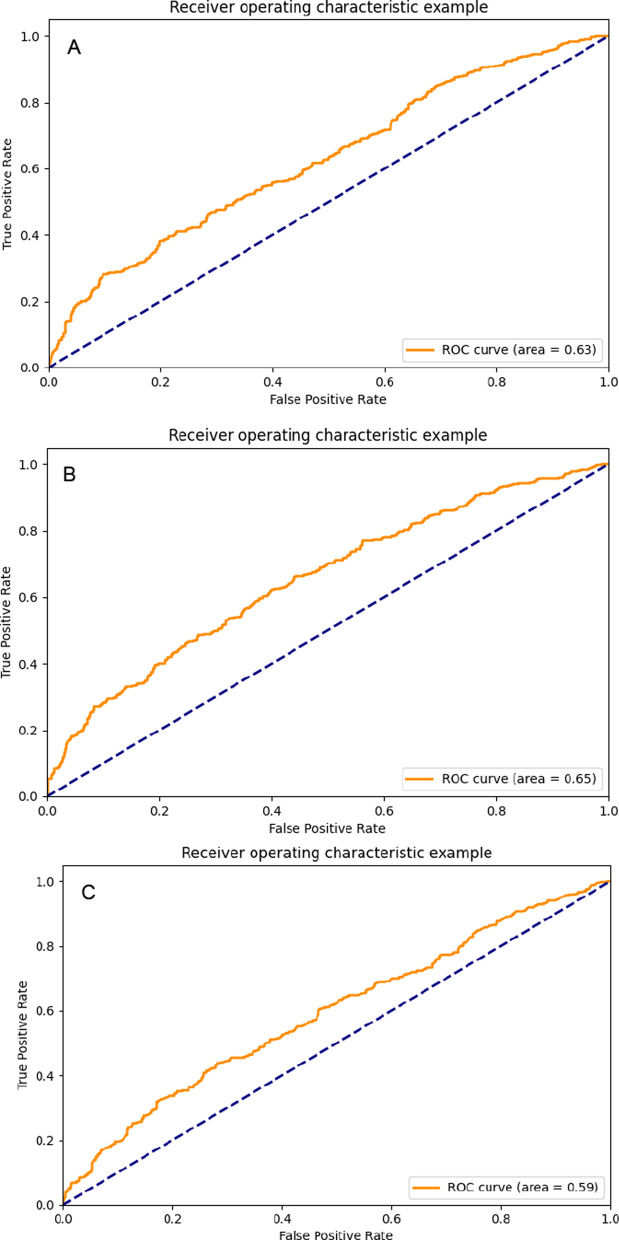

We drew ROC curves of all models. Figure 4 is the ROC curve obtained by the decision tree learning three types of data sets. Figure 5 is the ROC curve obtained by RF learning three types of data sets; Fig. 6 is the ROC curve obtained by ANN learning three types of data sets. We can see that the highest value of the area under the ROC curve of the model constructed by the artificial neural network combined with the feature selection variable set is 0.654 (95% CI, 0.625–0.683).

Fig. 4.

The ROC curves of decision tree models: A decision tree-all feature model; B decision tree-feature selection model; C decision tree-GRACE model;

Fig. 5.

The ROC curves of random forest models: A random forest-all feature models; B random forest -feature selection model; C random forest-GRACE model;

Fig. 6.

The ROC curves of ANN models: A ANN-all feature model; B ANN-feature selection model; C ANN-GRACE model

To further explore the clinical application value of ML, we used logistic regression to analyze the risk of important features of arrhythmia after AMI. The results showed RBBB (OR: 4.21; 95% CI: 2.42–7.02), ≥ 2 ventricular wall motion abnormalities (OR: 3.26; 95% CI: 2.01–4.36), and right coronary artery occlusion (OR: 3.00; 95% CI: 1.98–4.56) are important factors related to arrhythmia after AMI (Table 6).

Table 6.

Odds ratio for important characteristics

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (+ 10-year increments) | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) | < 0.001** |

| Heart rate (+ 20-beat increments) | 1.12 (1.06–1.24) | 0.047* |

| BBB | ||

| None | 1.00 (Dummy variable) | |

| LAFB | 1.33 (1.05–1.68) | 0.018* |

| LBBB | 1.22 (0.63–2.34) | 0.554 |

| LPFB | 1.48 (0.93–2.36) | 0.101 |

| RBBB | 4.21 (2.42–7.02) | < 0.001** |

| LAFB + RBBB | 4.36 (2.17–8.74) | < 0.001** |

| Ventricular wall motion abnormal | ||

| ≥ 2 walls | 3.26 (2.01–4.36) | < 0.001** |

| Anterior | ||

| 1.24 (0.71–2.19) | 0.453 | |

| Apex | 0.32 (0.08–1.23) | 0.980 |

| Anteroseptal | 0.20 (0.04–1.02) | 0.054 |

| Posterior | 1.41 (0.78–2.54) | 0.254 |

| Inferior | 1.21 (1.12–2.24) | 0.013* |

| None | 1.00 (Dummy variable) | |

| Lesions vessels | ||

| LAD | 1.00 (Dummy variable) | |

| LCX | 0.63 (0.33–1.19) | 0.154 |

| RCA | 3.00 (1.98–4.56) | < 0.001** |

| LM | 1.77 (1.03–3.06) | 0.040* |

| LAD + LCX | 0.91 (0.62–1.35) | 0.650 |

| LAD + RCA | 1.86 (1.33–2.60) | < 0.001** |

| RCA + LCX | 1.91 (1.20–3.03) | 0.006* |

| Triple vessels | 1.67 (1.22–2.64) | 0.001* |

* means P < 0.05, ** means P < 0.01

Discussion

AMI is a clinically critical illness, and the mortality rate after PCI can still reach 10% [3]. Arrhythmia after AMI complicates the patient's condition and increases the Incidence of adverse events (including stroke [31], higher use of pacemakers [4], re-infarction, cardiogenic shock, heart failure, asystole [8], and sudden cardiac death [32]). The hospital mortality of patients with arrhythmia [4, 6, 31, 33], 30-day mortality [34, 35], and 1-year mortality [8] are significantly higher than patients without arrhythmia. In addition, studies have found that in patients undergoing PCI treatment, arrhythmias occurring before and after cardiac catheterization are associated with increased mortality [7]. Therefore, it is essential to predict the occurrence of arrhythmia after AMI as early as possible. To this end, a large number of studies have analyzed the risk factors for arrhythmia after AMI [7, 8, 10, 11, 34, 36–41], but there is no systematic risk model. Currently, AMI's clinical risk model is mainly the GRACE risk score recommended by the ACC/AHA guidelines [42]. Still, it is mainly used to assess patients' mortality and may not accurately predict the occurrence of arrhythmia. Besides, the model is constructed using traditional statistical methods and only linearly analyzes the relationship between a few factors, does not explore the potential prognostic value of interactions between several unexpected weaker risk factors and the primary outcome. For complex diseases, multi-factor and multi-level interactions need to be analyzed. In this case, ML can provide a useful alternative when encountering a large number of potentially relevant variables when building a predictive model. In the cardiovascular field, ML has been used in medical image analysis [43–49], disease classification and diagnosis [16, 19, 50, 51], and predictive model construction [21, 25, 28, 52, 53]. At present, researches related to ML and AMI were mainly devoted to the prediction of patient mortality [25, 54], and the ML model of arrhythmia after AMI has not been explored. In this study, we collected big clinical data of 2084 AMI patients and applied the power of ML to develop predictive models of tachyarrhythmia after AMI.

Before ML, we included 45 variables based on the current AMI risk score [1, 35, 55–59] and the risk factors for tachyarrhythmia after AMI identified in previous studies [7–9, 11, 35–38, 60, 61]. First, we applied 3 ML techniques (decision tree, RF, ANN) combined with all 45 variables to assess the risk of tachyarrhythmia after AMI. Our goal is to accurately predict the patient's arrhythmia with as few features as possible, so we further used the top 15 highly predictive variables to build the ML model. We found that compared with other machine classifiers, the ANN algorithm has better predictive ability in the full-variable model, the important variable model, and the Grace variable model. Surprisingly, after feature selection, the ANN model obtained the best prediction performance. Finally, to evaluate the clinical efficacy of ML, we introduced the widely used GRACE risk variable set (including age, heart rate, blood pressure, Killip grade, ECG changes, myocardial enzymes, serum creatinine, and past medical history) to construct the model. The best accuracy obtained is lower than the feature selection-ANN model. It can be seen that the feature selection-ANN model has higher performance in predicting the occurrence of arrhythmia in the acute phase of AMI.

In terms of variable selection, we combine advanced ML algorithms to perform complex nonlinear analysis on important variables with significant predictive capabilities. In addition, to make the ML model interpretable, we use the SHAP method to show the importance of features. The top five are abnormal wall motion, lesion location, bundle branch block, age, and heart rate. Consistent with the results of previous studies, age, heart rate [8], inferior MI, RCA lesions [9], RBBB, and RBBB + LAFB [62] are related to the occurrence of an arrhythmia, proving that ML has a very reliable Clinical practice. More importantly, the lesion location, abnormal wall motion, and bundle branch block not included in the GRACE score rank the top three in ML, which means that the ML model we constructed is more suitable for predicting arrhythmia in the acute phase of AMI. Abnormal wall motion, bundle branch block, age, and heart rate are easily obtained clinically and can be used as key indicators for CCU physicians to monitor AMI patients. As mentioned above, the occurrence of arrhythmia after PCI can also increase the mortality of patients. Even after revascularization, stricter observations should be made based on the location of the lesion after PCI.

Our results show that the overall performance of ML was moderate, and therefore, it probably cannot yet replace diagnostic or risk estimations that further workup can provide. Nevertheless, when results were compared to those of utilizing the sets of variables considered in the Grace models, ML exhibited a higher performance for predicting the occurrence of tachyarrhythmia after AMI. Therefore, the ML model is more suitable for predicting arrhythmia after AMI than the Grace model and can be used to refine and supplement the current AMI risk score to help clinicians perform a more accurate risk assessment and timely treatment.

Limitation

The present study naturally carries the limitations of any observational study. However, this kind of largescale retrospective analysis is the main target of the data-driven approaches of ML. Second, this ML approach still needs further model training, validation, and optimization before clinical application. Patients in this study were enrolled from a single center that included only Chinese patients. Nevertheless, we compared the performance of advanced ML algorithms with the GRACE variable set model. The main finding of the current analysis was that ANN exhibited the highest prediction performance. ML-based prediction model could represent a great supplement in optimizing risk assessment and even clinical alerts of patients after AMI.

Conclusions

In summary, we used advanced ML algorithms to select 15 clinical variables and constructed a prediction model for the occurrence of tachyarrhythmias after AMI. This novel approach proved is superior to the method of the GRACE model. Early prediction of the occurrence of tachyarrhythmias in the acute phase of AMI is critical to clinicians' decision-making. This study highlights the utility of using ML methods for more precise risk assessment.

Perspectives

We established ML-based prediction models in a cohort of patients with AMI. The GRACE variable set model's comparable performance indicates ML approaches' potential value for evaluating complex and multifactorial diseases. There is no doubt that 2020 has been a great year, dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Under these difficult circumstances, most areas of cardiovascular research compromised due to national lockdowns. ML to extract and analyze large volumes of data remotely allowed cardiovascular medicine to continue its evolution. This study is only a small part of this booming field, providing new ideas for what will come to clinical practice in the coming years.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Convert continuous variables to ordinal categorical variables.

Additional file 2. Feature importance ranking.

Additional file 3. ANN 10-fold cross-validation model.

Additional file 4. Differences in all 45 characteristics between the two groups.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Huang Shaobin, Qiu Jiyu, Wang Peng, Yang Shunfan and Jiang Zhengqian from the School of Computer Science, Harbin Engineering University, for providing the assistance of statistics and debugging in Python work.

Abbreviations

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- AMI

Acute Myocardial Infarction

- ANN

Artificial Neural Network

- AUC

Area Under The Curve

- BNP

Brain Natriuretic Peptide

- GRACE

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

- ML

Machine Learning

- TNI

Troponin I

- TNT

Troponin T

Authors' contributions

SW designed and experimented and participated in the data collection, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. JC and SW collected data on patients with AMI, while LZ and SS analyzed data on patients with post-AMI arrhythmias. JL and LS, as corresponding authors, guided the progress of the study throughout the process to ensure the authenticity of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee approved the study of the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, and the right to exempt informed consent was obtained. The Chinese Clinical Trial Registry approved this study (No.:ChiCTR2100041960).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Suhuai Wang, Email: 372063609@qq.com.

Jingjie Li, Email: Circulation9999@163.com.

Lin Sun, Email: drsunlin@sina.com.

Jianing Cai, Email: 601428563@qq.com.

Shihui Wang, Email: 1449454745@qq.com.

Linwen Zeng, Email: 2116705008@qq.com.

Shaoqing Sun, Email: 1359630408@qq.com.

References

- 1.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, ESC Scientific Document Group et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puymirat E, Simon T, Steg P, Schiele F, Guéret P, Blanchard D, Danchin N, et al. Association of changes in clinical characteristics and management with improvement in survival among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2012;308:998–1006. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedersen F, Butrymovich V, Kelbæk H, Wachtell K, Helqvist S, Kastrup J, Jørgensen E, et al. Short- and long-term cause of death in patients treated with primary PCI for STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2101–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SM, Fitzgerald G, Yan AT, Brieger D, Fox KA, Lopez-Sendon J, Goodman SG, et al. High-grade atrioventricular block in acute coronary syndromes: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:976–983. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bang CN, Gislason GH, Greve AM, Bang CA, Lilja A, Torp-Pedersen C, Wachtell K, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation is associated with cardiovascular events leading to death in a first time myocardial infarction population of 89,703 patients with long-term follow-up: a nationwide study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000382. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Page RL, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: Executive Summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017;2018(138):e210–e271. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta RH, Starr AZ, Lopes RD, Hochman JS, Widimsky P, Pieper KS, For the APEX AMI Investigators et al. Incidence of and outcomes associated with ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2009;301:1779–1789. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt J, Duray G, Gersh BJ, Hohnloser SH. Atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review of the incidence, clinical features and prognostic implications. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1038–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta RH, Harjai KJ, Grines L, Stone GW, Boura J, Cox D, Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI) Investigators et al. Sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in the cardiac catheterization laboratory among patients receiving primary percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence, predictors, and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1765–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravn Jacobsen M, Jabbari R, Glinge C, Kjaer Stampe N, Butt JH, Blanche P, Engstrom T, et al. Potassium disturbances and risk of ventricular fibrillation among patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014160. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabbari R, Engstrom T, Glinge C, Risgaard B, Jabbari J, Winkel BG, Tfelt-Hansen J, et al. Incidence and risk factors of ventricular fibrillation before primary angioplasty in patients with first ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a nationwide study in Denmark. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001399. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoudi E, Kamdar N, Kim N, Gonzales G, Singh K, Waljee AK. Use of electronic medical records in development and validation of risk prediction models of hospital readmission: systematic review. BMJ. 2020;369:m958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine learning and the profession of medicine. JAMA. 2016;315:551–552. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1347–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1814259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beam AL, Kohane IS. Big data and machine learning in health care. JAMA. 2018;319:1317–1318. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loring Z, Mehrotra S, Piccini JP. Machine learning in 'big data': handle with care. Europace. 2019;21:1284–1285. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyland SL, Faltys M, Huser M, Lyu X, Gumbsch T, Esteban C, Merz TM, et al. Early prediction of circulatory failure in the intensive care unit using machine learning. Nat Med. 2020;26:364–373. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein BA, Navar AM, Carter RE. Moving beyond regression techniques in cardiovascular risk prediction: applying machine learning to address analytic challenges. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1805–1814. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Than MP, Pickering JW, Sandoval Y, Shah ASV, Tsanas A, Apple FS, On behalf of the MI Collaborative et al. Machine learning to predict the likelihood of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2019;140(11):899. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motwani M, Dey D, Berman DS, Germano G, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah MH, Slomka PJ, et al. Machine learning for prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: a 5-year multicentre prospective registry analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:500–507. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Yuan X, Wang W, Liu K, Qin Y, Sun X, Song L, et al. Value of a machine learning approach for predicting clinical outcomes in young patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;75:1271–1278. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narula S, Shameer K, Salem Omar AM, Dudley JT, Sengupta PP. Machine-learning algorithms to automate morphological and functional assessments in 2D echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2287–2295. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sengupta PP, Kulkarni H, Narula J. Prediction of abnormal myocardial relaxation from signal processed surface ECG. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1650–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bax JJ, Van Der Bijl P, Delgado V. Machine learning for electrocardiographic diagnosis of left ventricular early diastolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1661–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett LA, Payrovnaziri SN, Bian J, He Z. Building computational models to predict one-year mortality in ICU patients with acute myocardial infarction and post myocardial infarction syndrome. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2019;2019:407–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payrovnaziri SN, Barrett LA, Bis D, Bian J, He Z. Enhancing prediction models for one-year mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction and post myocardial infarction syndrome. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;264:273–277. doi: 10.3233/SHTI190226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li YM, Jiang LC, He JJ, Jia KY, Peng Y, Chen M. Machine learning to predict the 1-year mortality rate after acute anterior myocardial infarction in chinese patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:1–6. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S236498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al'aref SJ, Singh G, Van Rosendael AR, Kolli KK, Ma X, Maliakal G, Minutello RM, et al. Determinants of in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: a machine learning approach. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011160. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildirim O, Plawiak P, Tan RS, Acharya UR. Arrhythmia detection using deep convolutional neural network with long duration ECG signals. Comput Biol Med. 2018;102:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luz EJ, Schwartz WR, Camara-Chavez G, Menotti D. ECG-based heartbeat classification for arrhythmia detection: a survey. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;127:144–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Jr, Yancy CW, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;2019(140):e125–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen OD, Abildstrom SZ, Ottesen MM, Rask-Madsen C, Bagger H, Kober L, On Behalf of the TRACE study investigators et al. Increased risk of sudden and non-sudden cardiovascular death in patients with atrial fibrillation/flutter following acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:290–295. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bougouin W, Marijon E, Puymirat E, Defaye P, Celermajer DS, Le Heuzey JY, On Behalf of FAST-MI Registry Investigators et al. Incidence of sudden cardiac death after ventricular fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction: a 5-year cause-of-death analysis of the FAST-MI 2005 registry. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:116–122. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henkel DM, Witt BJ, Gersh BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Meverden RA, Roger VL. Ventricular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction: a 20-year community study. Am Heart J. 2006;151:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jabbari R, Risgaard B, Fosbol EL, Scheike T, Philbert BT, Winkel BG, Engstrom T, et al. Factors associated with and outcomes after ventricular fibrillation before and during primary angioplasty in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gang UJ, Hvelplund A, Pedersen S, Iversen A, Jons C, Abildstrom SZ, Thomsen PE, et al. High-degree atrioventricular block complicating ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Europace. 2012;14:1639–1645. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auffret V, Loirat A, Leurent G, Martins RP, Filippi E, Coudert I, Le Breton H, et al. High-degree atrioventricular block complicating ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in the contemporary era. Heart. 2016;102:40–49. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehta RH, Dabbous OH, Granger CB, Kuznetsova P, Kline-Rogers EM, Anderson FA, Jr, GRACE Investigators et al. Comparison of outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes with and without atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aronson D, Mutlak D, Bahouth F, Bishara R, Hammerman H, Lessick J, Agmon Y, et al. Restrictive left ventricular filling pattern and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1738–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demidova MM, Carlson J, Erlinge D, Platonov PG. Predictors of ventricular fibrillation at reperfusion in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piccini JP, Berger JS, Brown DL. Early sustained ventricular arrhythmias complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2008;121:797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, Jr, AaTF M, et al. AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;2014(130):e344–426. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuncer T, Dogan S, Pławiak P, Acharya UR. Automated arrhythmia detection using novel hexadecimal local pattern and multilevel wavelet transform with ECG signals. Knowl-Based Syst. 2019;186:104923. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.104923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baygin M, Tuncer T, Dogan S, Tan RS, Acharya UR. Automated arrhythmia detection with homeomorphically irreducible tree technique using more than 10,000 individual subject ECG records. Inf Sci. 2021;575:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2021.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tt A, Sd A, Rstb C, Urade F. Application of Petersen graph pattern technique for automated detection of heart valve diseases with PCG signals. Inf Sci. 2021;565:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2021.01.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al'aref SJ, Anchouche K, Singh G, Slomka PJ, Kolli KK, Kumar A, Min JK, et al. Clinical applications of machine learning in cardiovascular disease and its relevance to cardiac imaging. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1975–1986. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ouyang D, He B, Ghorbani A, Yuan N, Ebinger J, Langlotz CP, Zou JY, et al. Video-based AI for beat-to-beat assessment of cardiac function. Nature. 2020;580:252–256. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2145-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dey D, Lin A. Machine-learning CT-FFR and extensive coronary calcium: overcoming the achilles heel of coronary computed tomography angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:771–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saria S, Hae H, Kang S-J, Kim W-J, Choi S-Y, Lee J-G, Park S-J, et al. Machine learning assessment of myocardial ischemia using angiography: development and retrospective validation. PLOS Med. 2018;15:e1002693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sevakula RK, Au-Yeung WM, Singh JP, Heist EK, Isselbacher EM, Armoundas AA. State-of-the-art machine learning techniques aiming to improve patient outcomes pertaining to the cardiovascular system. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e013924. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fries JA, Varma P, Chen VS, Xiao K, Tejeda H, Saha P, Priest JR, et al. Weakly supervised classification of aortic valve malformations using unlabeled cardiac MRI sequences. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3111. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhattacharya M, Lu DY, Kudchadkar SM, Greenland GV, Lingamaneni P, Corona-Villalobos CP, Abraham MR, et al. Identifying ventricular arrhythmias and their predictors by applying machine learning methods to electronic health records in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM-VAr-risk model) Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:1681–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frizzell JD, Liang L, Schulte PJ, Yancy CW, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Laskey WK, et al. Prediction of 30-day all-cause readmissions in patients hospitalized for heart failure: comparison of machine learning and other statistical approaches. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:204–209. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shouval R, Hadanny A, Shlomo N, Iakobishvili Z, Unger R, Zahger D, Beigel R, et al. Machine learning for prediction of 30-day mortality after ST elevation myocardial infraction: an Acute Coronary Syndrome Israeli Survey data mining study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;246:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chowdhary S, Ivanov J, Mackie K, Seidelin PH, Dzavik V. The Toronto score for in-hospital mortality after percutaneous coronary interventions. Am Heart J. 2009;157:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh M, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Spertus J, Rumsfeld JS, Holmes DR., Jr Bedside estimation of risk from percutaneous coronary intervention: the new Mayo Clinic risk scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:701–708. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goriki Y, Tanaka A, Nishihira K, Kawaguchi A, Natsuaki M, Watanabe N, Node K, et al. A novel predictive model for in-hospital mortality based on a combination of multiple blood variables in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. J Clin Med. 2020;9:852. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim HK, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, Kim JH, Chae SC, Kim YJ, Other Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry InvestigatorsKorea Acute Myocardial infarction Registry (KAMIR) Study Group of Korean Circulation Society et al. A new risk score system for the assessment of clinical outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2010;145:450–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schellings DA, Adiyaman A, Dambrink JE, Gosselink AM, Kedhi E, Roolvink V, Van’t Hof AW, et al. Predictive value of NT-proBNP for 30-day mortality in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a comparison with the GRACE and TIMI risk scores. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:471–476. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S117204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim HL, Kim SH, Seo JB, Chung WY, Zo JH, Kim MA, Other Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry KWGOMII et al. Influence of second- and third-degree heart block on 30-day outcome following acute myocardial infarction in the drug-eluting stent era. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1658–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schulze RA, Jr, Humphries JO, Griffith LS, Ducci H, Achuff S, Baird MG, Pitt B, et al. Left ventricular and coronary angiographic anatomy: relationship to ventricular irritability in the late hospital phase of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1977;55:839–843. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.55.6.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong CK, Gao W, Stewart RA, Van Pelt N, French JK, Aylward PE, Hirulog Early Reperfusion Occlusion (HERO-2) Investigators et al. Risk stratification of patients with acute anterior myocardial infarction and right bundle-branch block: importance of QRS duration and early ST-segment resolution after fibrinolytic therapy. Circulation. 2006;114:783–789. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.639039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Convert continuous variables to ordinal categorical variables.

Additional file 2. Feature importance ranking.

Additional file 3. ANN 10-fold cross-validation model.

Additional file 4. Differences in all 45 characteristics between the two groups.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].