Abstract

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has triggered an international pandemic that has led to significant public health problems. To date, limited evidence exists to suggest that drugs are effective against the disease. As possible treatments are being investigated, herbal medicines have shown potential for producing novel antiviral agents for the COVID-19 disease.

Aim

This review explored the potential of Malawi's traditional medicinal plants for the management of COVID-19.

Methods

The authors searched on PubMed and Google scholar for medicinal plants that are used in Malawi and published in openly available peer reviewed journals. Plants linked with antiviral treatment, anti-COVID-19 activity or COVID-19 symptoms management were targeted. These included activity against pneumonia, inflammation, cough, difficulty in breathing, pain/aches, fever, diarrhoea, rheumatism, fatigue, asthma, immunocompromised and cardiovascular diseases.

Results

11 studies were found with 306 plant species. 127 plant species had at least one COVID-19 related pharmacological activity. Of these plant species, the number of herbal entities used for each indication was: pain/aches (87), fever (2), pneumonia (9), breathing/asthma problems (5), coughing (11), diarrhoea (1), immunosuppression (8), blood issues (10), fatigue (2), heart problems (11), inflammation (8), rheumatism (10) and viral diseases (12). Thirty (30) species were used for more than one disease and Azedarachta indica topped the list (6 of the 13 COVID-19 related diseases). The majority of the species had phytochemicals known to have antiviral activity or mechanisms of actions linked to COVID-19 and consequent diseases' treatment pathways.

Conclusion

Medicinal plants are a promising source of compounds that can be used for drug development of COVID-19 related diseases. This review highlights potential targets for the World Health Organization and other research entities to explore in order to assist in controlling the pandemic.

Keywords: traditional medicine, herbal products, corona virus, drug development, screening

Introduction

Viruses are pathogens that cause communicable diseases like flu, AIDS and Ebola and increasing evidence shows that some viruses play a role in the disease mechanism of some non-communicable diseases like cancers, Alzheimer's disease and type 1 diabetes with high morbidity and mortality rates worldwide.1 Most of these diseases have proved hard to cure.2–5 Viruses cause epidemics that emerge and re-emerge and are easily transmitted to different locations due to increased global travel and rapid urbanization. Emergence of novel viruses and rapid mutation of old viruses make drug as well as vaccine development challenging and these are some of the major reasons why there has not been significant development of effective drugs or vaccines against many viruses. Notable viruses that have caused outbreaks with significant public health implications worldwide include dengue virus, influenza virus, measles virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus, and West Nile virus and the recently discovered severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).6–9 The SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus that was discovered in 2019 in Wuhan City of Hubei Province in China and has spread rapidly throughout the world, causing serious health care burden. The virus causes a disease called COVID-19 disease that affects all populations of people, but the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions are at a higher risk of morbidity and mortality.10 Being a novel disease caused by a novel virus, knowledge about the virus and the disease is limited and keeps on developing daily.11

SARS-CoV-2 is a 60 nm to 140 nm diameter, enveloped, positive sense RNA virus (11) belonging to the Coronaviruses (CoVs) that are generally enveloped viruses with single-stranded RNA genome. CoVs have the largest genomes to date among RNA viruses that range from approximately 26 to 32 kilobases. They replicate by genes encoding for viral structural proteins such as nucleocapsids (N), membranes (M), spikes (S), and envelopes (E), which play significant roles in viral integrity.12 However, there are other commonly studied proteins that have been widely targeted for drug development. These include papain-like protease (PLpro), 3c-like protease (3CLpro) and spike protein13–16.

Coronaviruses infections are well known for causing enteric, respiratory and central nervous system diseases in animals and humans.17 The nomenclature of coronaviruses originates from spike-like projections on its surface, which gives it a shape similar to a crown when viewed under an electron microscope.16,18 The gene sequence of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19, suggests that its proteins are similar to those of South Asia Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).19,20 Hence, drugs, compounds and medicinal plants or extracts known to inhibit these proteins in SARS and MERS could be promising leads for COVID-19 drug development.

COVID-19 is transmitted by large water droplets released by infected people (symptomatic or asymptomatic) when they cough and sneeze, and they survive in these droplets that are spread on the surfaces or individual's bodies.21 Higher viral loads can be found in the nasal cavity than the throat.22 People are infected by touching their nose, eyes or mouth after touching surfaces contaminated with SARS-CoV-2.23,24 The virus enters the respiratory mucosa using angiotensin converting enzyme receptor 2 (ACE-2).25 The virus can easily be killed by common disinfectants such as ethanol (preferably ≥ 80%), sodium hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide.23,24

COVID-19 patients can be symptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or asymptomatic.26 Common clinical features are fever, dry cough, sore throat, fatigue, headache, conjunctivitis, myalgia and breathlessness as well as loss of taste or smell.27–29 Some patients also develop pneumonia and respiratory failure and may die within weeks. The latter scenario is associated with an extreme increase in inflammatory cytokines (cytokine storm), especially IL2, IL7, IL10, GCSF, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and TNFα.30 The COVID-19 disease is also associated with complications such as acute lung injury, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), shock, and acute kidney injury.

Currently, there are no approved treatment medicines in use for COVID-19 disease. The disease is being managed by prevention of transmission (face masks and washing hands with soap and water or using hand sanitizer), maintaining hydration and nutrition, controlling fever and cough, provision of oxygen and renal replacement therapy. The use of these interventions varies by availability, access, location and disease severity. Therefore, there is a need to discover, design or develop novel efficacious and cost-effective antivirals as the search for effective vaccines continues.9

Several approaches are being implemented to tackle COVID-19, one of which is the repurposing of widely used conventional and herbal medicines.31 Antiviral drugs (ribavirin, lopinavir-ritonavir based on experience in SARS and MERS), combination therapy of oseltamivir, ganciclovir and lopinavir-ritonavir, and remdesivir (broad spectrum anti-RNA drug developed for Ebola) have been tested. Remdesivir, the only antiviral option showing benefit to date, has shown statistically significant improvements in time to recovery in hospitalized patients in comparison with placebo.32 Short term therapy with low-to-moderate dose corticosteroids (such as dexamethasone) in COVID-19 ARDS, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, arbidol (antiviral drug), interferons, hydroxychloroquine and plasma of patients recovered from COVID-19 have been trialled. Despite preliminary reports showing that dexamethasone may decrease mortality rates among critically ill patients, more evidence about its efficacy and safety, along with other agents, are needed before these treatment options are fully recommended for use.30,33–39

Traditional medicines, especially Chinese herbs, have been tested for use in COVID-19.33 Aanouz et al., (2020) used computational techniques to evaluate the inhibition potential of compounds isolated from plants used in Morocco against COVID-19 virus. Sixty seven (67) compounds isolated from aromatic and medicinal plants were found and selected for molecular docking studies that used energy of interaction between the compound's functional groups and the corona virus (SARS-COV-2 spike protein) as one of the criteria for anti-corona virus effect. Chloroquine was used as a standard (interaction energy of -6 kcal/mol). Eleven (11) molecules showed a good interaction with the target, but the three greatest activities were for Crocin from Crocus sativus L. (-8.2kcal/mol), Digitoxigenin (Nerium oleander L., -7.2 kcal/mol) and β -Eudesmol (Laurus nobilis L., -7.1kcal/mol). Experimental data also showed that they had antiviral activity.40 For example, Crocin was found in vitro to be an inhibitor of the replication of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) before and after virion entry in Vero cells, and its plant/herbal medicine source showed promise for use as an anti-HSV and anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) agent.41 Derivatives of Digitoxigenin are used as antiviral and anticancer inhibitors, while β-Eudesmol has substantial antibacterial and antiviral activity.42–43

Zhang et al., (2020) executed a rational computer-based screening study aimed at identifying Chinese medical herbs and compounds with antiviral activity against respiratory infections and COVID-19. This computer-based study searched through literature for natural compounds and their respective traditional Chinese medicinal plants known to fight against MERS or SARS coronavirus. Docking studies were completed to analyse their potential for direct interaction with SARS-COV-2 protein, followed by biological activity search from literature. Thirteen (13) out of the 115 compounds found in the search of traditional Chinese medicines exhibited potential for anti-COVID-19 activity and 125 screened Chinese herbs contained 2 or more of the 13 compounds. A search for pharmacological activity showed that 26 of the 125 herbs had antiviral activity in respiratory infection, and that they regulated viral infection, immune/inflammation reactions and response to hypoxia.44

Hui et al., (2020) evaluated studies that tested the use of Chinese medicine (CM) as prophylaxis on people exposed to SARS and H1N1 influenza in clinical trials, cohort or other population studies. Results showed that the Chinese medicines performed well as prophylaxis, an effectiveness that has also been recorded in historical practice with CM.45 During the COVID-19 epidemic, several CM products were also tested in humans for prevention of the epidemic effects and selection of the CM was based on historical use and previous experimental results in similar viral epidemics. The CM used in the studies included radix astragali (Astragalus propinquus Schischkin), radix glycyrrhizae (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC.), radix saposhnikoviae (Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk.), rhizoma atractylodis macrocephalae (Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz.), lonicerae japonicae flos (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) and fructus forsythia (Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl.). This study revealed that historical use and previous use of the CM in similar epidemics provided clues for selection of CM use and efficacy in COVID-19.45,46

Plant extracts of Lycoris radiata (L'Hér.) Herb., Artemisia annua L., Pyrrosia lingua (Thunb.) Farw. and Lindera aggregata (Sims.) Kosterm. were also evaluated and found to have anti-SARS activity after a screening exercise of hundreds of CMs.47

Apart from whole plant extracts, phytochemicals have been evaluated and shown potential for activity against COVID-19 disease, including Saikosaponins Types A, B2, C, and D (phytochemicals belonging to naturally occurring triterpene glycosides). For example, Saikosaponins from Bupleurum spp., Heteromorpha spp., Scrophularia scorodonia L. have showed antiviral activity against a human and bat corona virus HCoV-229E, that together with OC43, causes the common cold.34,47

Furthermore, inhibitors of SARS enzymes (nsP13 helicase and 3CL protease) have also been isolated from plants. For example, myricetin is a flavonoid polyphenolic compound that has anti-oxidant properties.48 Scutellarein, a flavone isolated from Scutellaria lateriflora L., has shown activity against SARS.35,49 Phenolic compounds isolated from Isatis tinctoria L., Torreya nucifera (L.) Siebold & Zucc. and a water extract of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. have also exhibited antiviral mechanisms against SARS.50 These water extracts have been particularly known to inhibit viral 3CL protease as well as blocking viral RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase activity.51

Herbal-western medicine combination therapies of lopinavir/ritonavir (anti-HIV medicines), arbidol (broad-spectrum antiviral) and CM Shufeng Jiedu capsule as well as lopinavir/ritonavir and CM Shufeng Jiedu capsule have also been tested clinically. Clinical observations for both herbal-western medicine combination therapies treated patients showed that the TCMs treatments were effective in a majority of the patients that were treated with them, which showed that the TCMs can play a role in treating COVID-19. The Herbal-western medicine combination therapies were very important in the treatment of the viral pneumonia. It was found that more studies were needed to produce conclusive results on the curing capability of the combination therapies on COVID-19.52

In the search for chemotherapy for COVID-19, there are different sources of medicines, one of which is traditional medicines or medicinal plants. In the African region including Malawi, treatment options commonly stem from medicinal plants due to their abundance and untapped potential. 80% of the population in this region relies on medicinal plants as a primary health care option.53

Several studies have already started exploring plants for COVID-19 cure.32,54 There may be other unexplored plants that have potential for producing a cure for the disease or addressing mild to severe symptoms. Therefore, it is important to analyse the plants that have shown potential for COVID-19 activity and study plants with similar attributes. The following section explores the literature on studies that have evaluated the efficacy of medicinal plants on SARS-CoV-2 as well as searching for plants with similar antiviral potential in Malawi. For a plant or its isolated compounds to have potential for use in COVID-19, it should be able to kill or inactivate the virus or alleviate the symptoms and complications caused by coronavirus infection.

Significance of the Study on Medicinal plants with potential for use in COVID-19 in Malawi

The WHO recommends supportive care options such as the use of supplemental oxygen through ventilators but these interventions are too expensive for most low-income countries with under resourced healthcare systems.55,56 Furthermore, there are gaps in trained health care providers for such interventions.57 The majority of biomedical COVID-19 treatment options available lack data to support their effectiveness.55 Options that are showing some clinical promise have soaring prices and frequent stock outs.58 Hence, medicinal plants may be alternatives for individuals in Malawi and other developing countries. Although there have been in-vitro studies that have shown activity for various aspects of COVID-19, there hasn't been a study completed in Malawi to assess the efficacy or toxicity of medicinal plants. Although various medicinal plants have been analysed abroad, these data cannot be extrapolated to the same species in Malawi since geographical differences have been identified in medicinal plants' composition and activity.59 Hence, this study seeks to provide baseline data for use in the discussion of Malawi's medicinal plants use in COVID-19 treatment. Furthermore, it may confirm or refute widely-circulating arguments or fears concerning the use of medicinal plants against COVID-19. This will be achieved by the following specific objectives: To examine published ethnobotanical studies conducted in Malawi in order to identify the medicinal plants with demonstrated activity or potential for activity against COVID-19 disease. To evaluate the literature for reported pharmacological properties of medicinal plants found to have potential for use in COVID-19 disease.

Methods

The authors searched for studies on medicinal plants that are used in Malawi that met the following inclusion criteria: Published in peer reviewed journals that were openly available online between January 1994 and July 2020. Had medicinal plants reported to be found and used in Malawi by at least one ethnobotanical survey as well as being tested in a laboratory.

The plant had been linked with antiviral or anti-COVID-19 use or against the symptoms of COVID-19. The key words that were used on Google Scholar and PubMed were: Ethnobotany, ethnobotanical survey, Malawi, Malawi herbal medicine, Malawi herbalist, Malawi medicinal plant, Malawi phytochemical screening, Malawi herbals and traditional medicine. Eleven (11) studies met the inclusion criteria while over 93 studies were excluded because plants reported were not cited in the ethnobotanical surveys reported in Malawi. All plant extracts that had potential for use in COVID-19 were considered. That potential was shown by its local use on viral infections or antiviral activity (e.g., curative action against pneumonia and inflammation), COVID-19 symptoms (symptom management of cough, difficulty in breathing, pain/aches, fever, diarrhoea, rheumatism and fatigue) and risk factors (high risk comorbidities like asthma, immunocompromise and cardiovascular diseases).

For the plants that met the above criteria, further searches were conducted on Google Scholar and PubMed using key words: scientific or botanical name of the plant, phytochemicals, bioactivity and pharmacological activity to find out if there have been any laboratory studies in Malawi or any other country to evaluate their biological or pharmacological activity on COVID-19 and consequent diseases. Summaries of all the studies and plants were created using Microsoft Excel.

Results

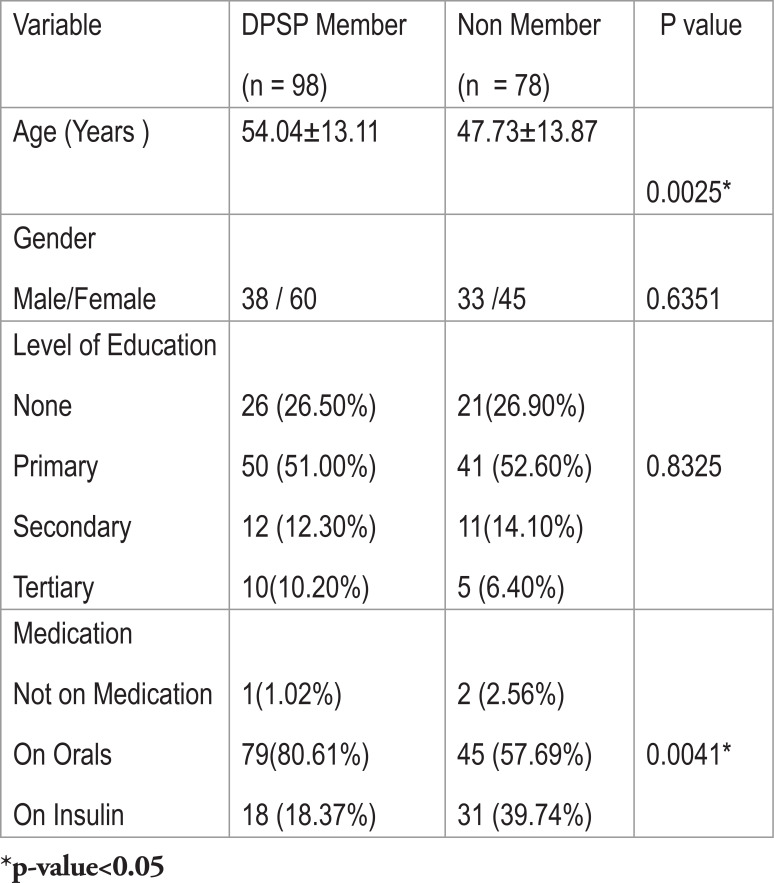

The literature search found a total of 11 studies.60–70 Plant list extraction yielded 306 plant species thereafter removing species that were irrelevant or not identified by a botanist (Additional File 1: Table 1). Of these 306 medicinal plants, 127 plants were found to manage at least one of the symptoms related to COVID-19 or were found to be used for the management of viral infections (Additional File 2: Table 2). Table 3 shows a summary of the results shown in the Additional File 2.

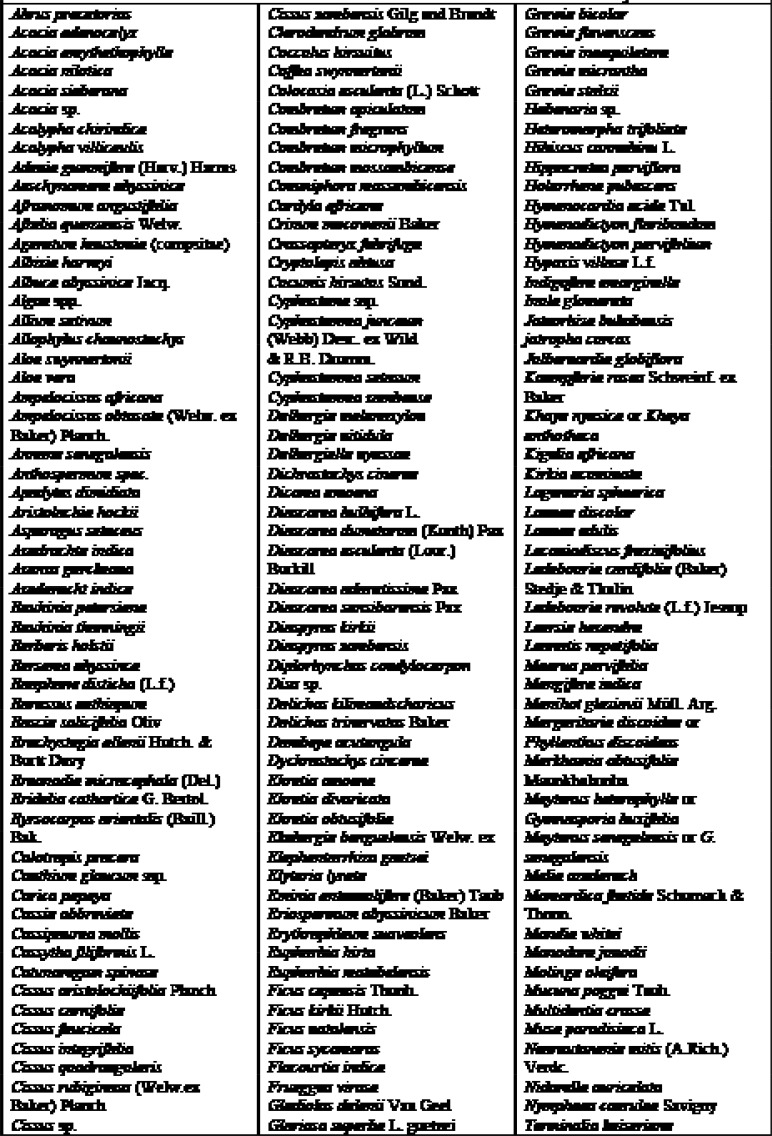

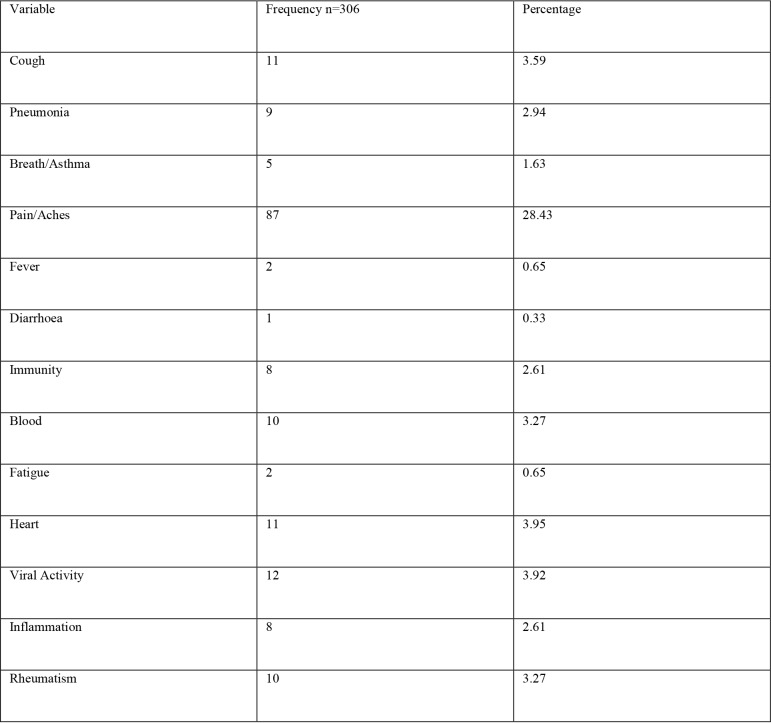

Table 1.

List of Medicinal Plants that were included in the study

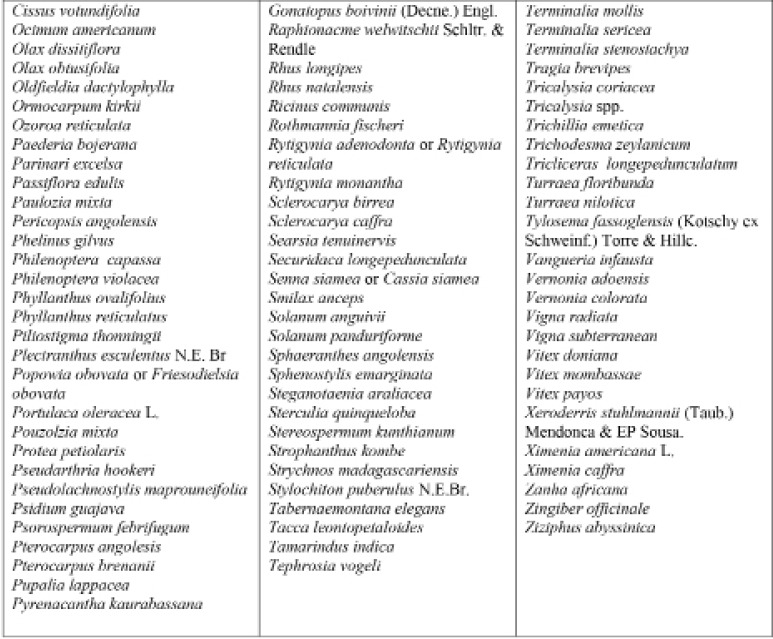

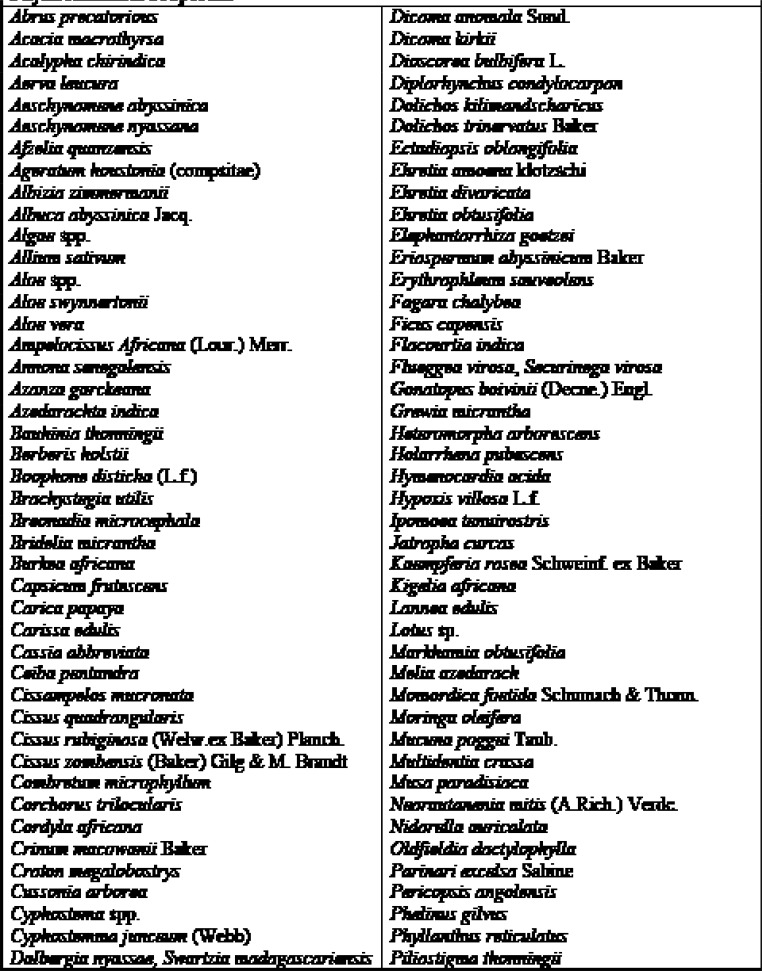

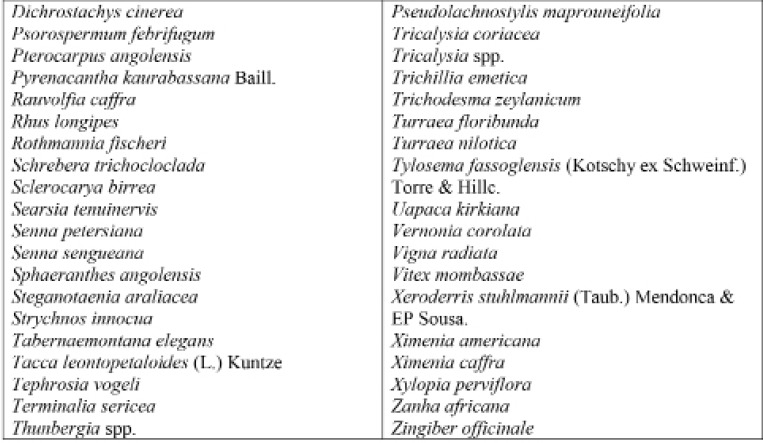

Table 2.

List of Medicinal Plants that were evaluated further for Pharmacological and Physicochemical Properties

Table 3.

Number of plants found to be used for each of the COVID-19 related diseases or symptoms

This study revealed that 87 of 127 medicinal plants could be used for pain or aches management, and two of those for fever management (Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and Pyrenacantha kaurabassana Baill.). Pneumonia is another symptom associated with COVID-19. In this study, we found 9 medicinal plants that are used traditionally to manage pneumonia and 5 that have potential for use in managing breathing or asthma problems. Other diseases associated with COVID-19 for which we identified traditional medicines included coughing (11 plants), diarrhoea (1 plant), immunosuppression (8 plants), blood related issues (10 plants), fatigue (2 plants), heart problems (11 plants), inflammation (8 plants) and rheumatism (10 plants). COVID-19 is a viral infection and any medicinal plant used for viral diseases has potential of being tested on coronavirus. There were 12 plants found to have been used for viral infections or diseases.

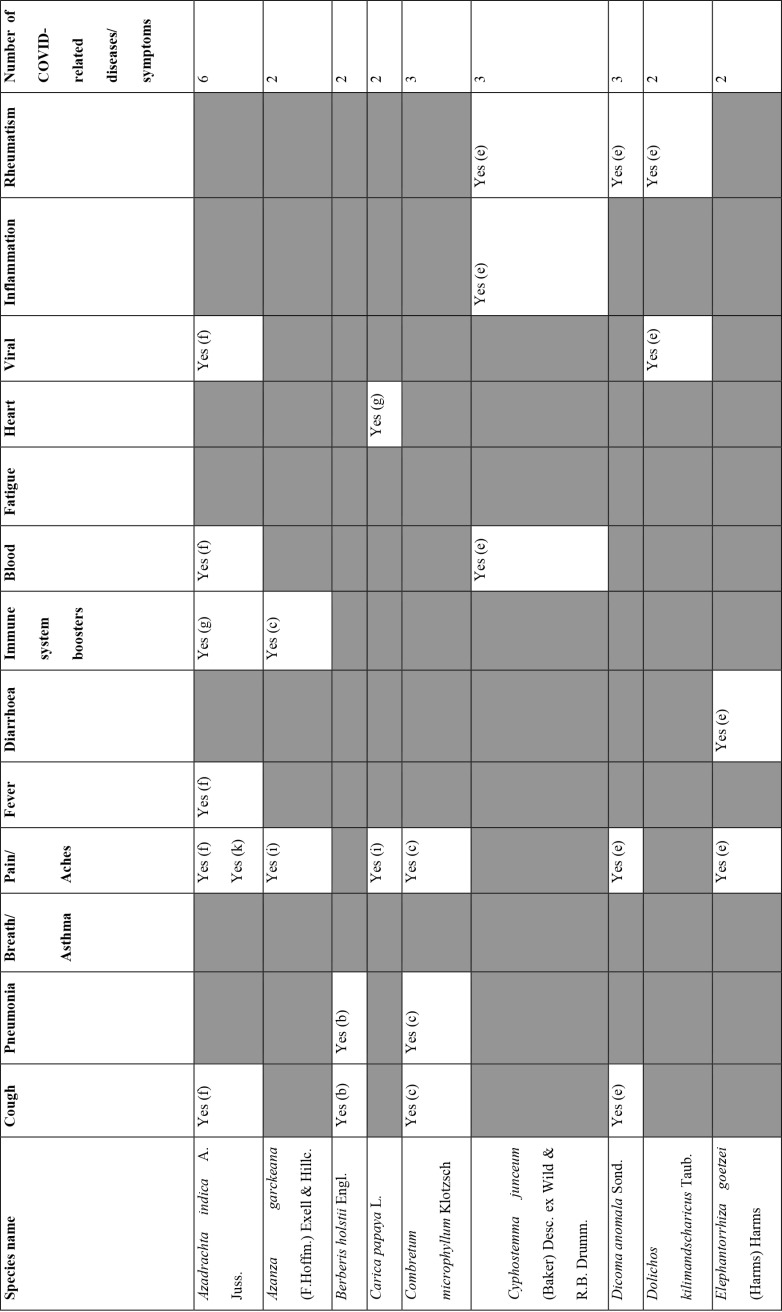

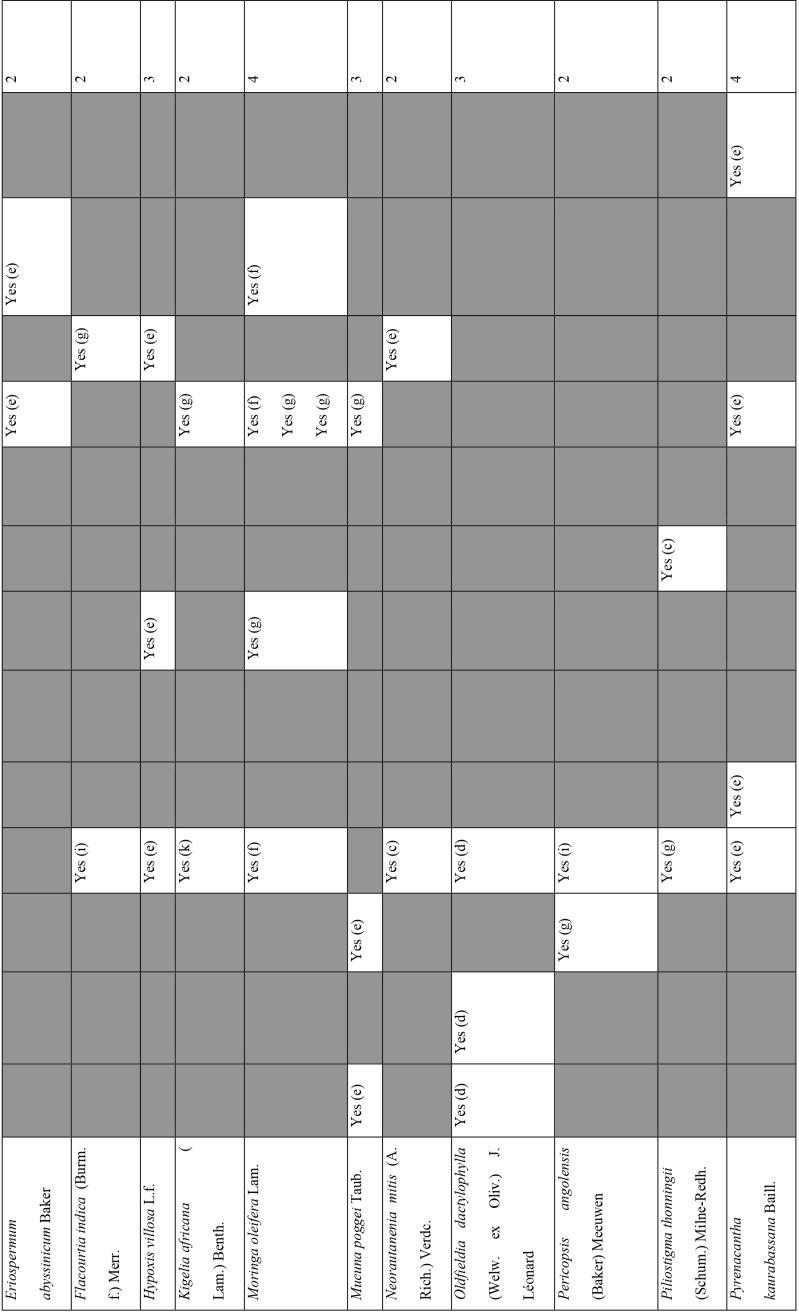

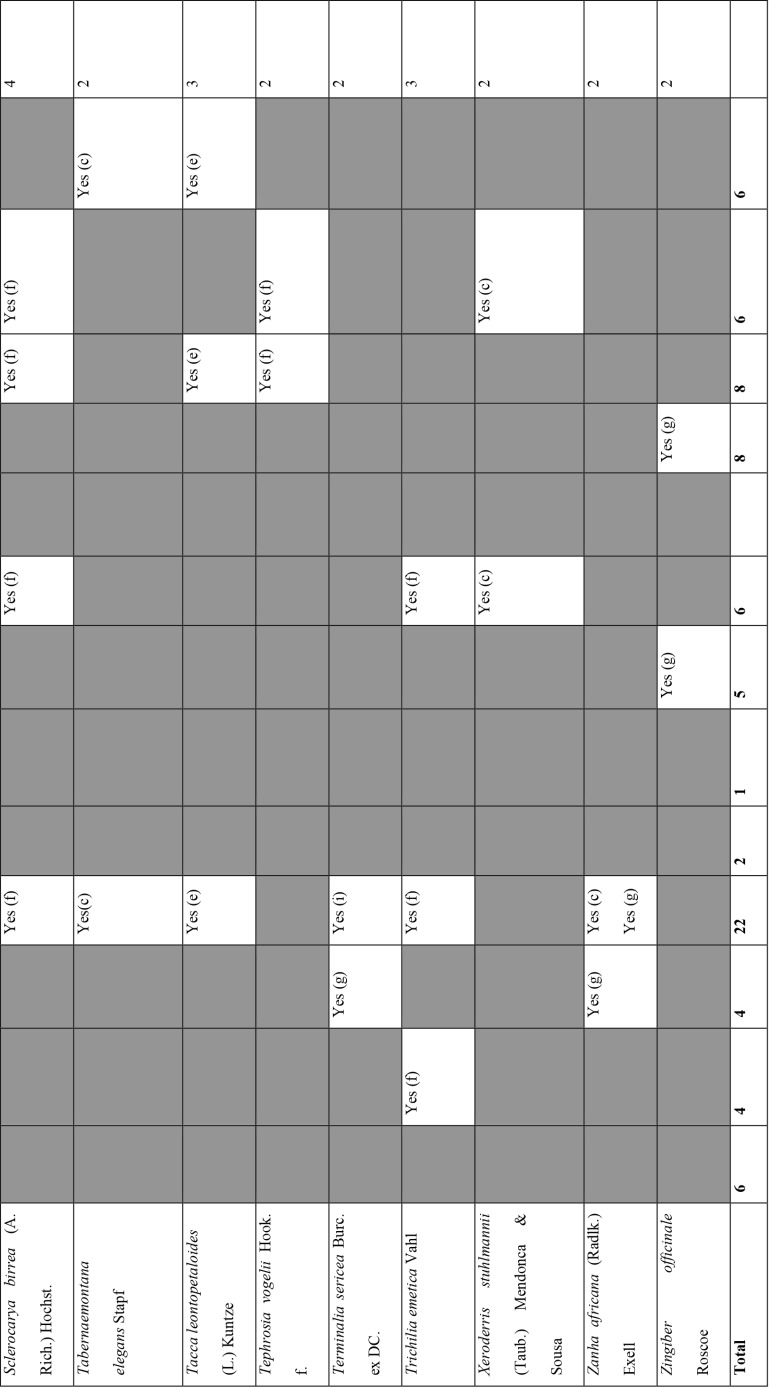

Of the 127 medicinal plants with potential to manage COVID-19 related diseases or symptoms, 30 had more than one disease for which they could be used. Azedarachta indica topped the list with being used for 6 of the 13 COVID-19 related diseases, high risk comorbidities and symptoms followed by Moringa oleifera Lam. Pyrenacantha kaurabassana Baill. and Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Hochst. that could be used on 4 aspects of COVID-19. Analysis of these 30 plants revealed that they covered all types of the diseases except one; fatigue. Table 4 shows the 30 plant species and their associated benefits for COVID-19 management.

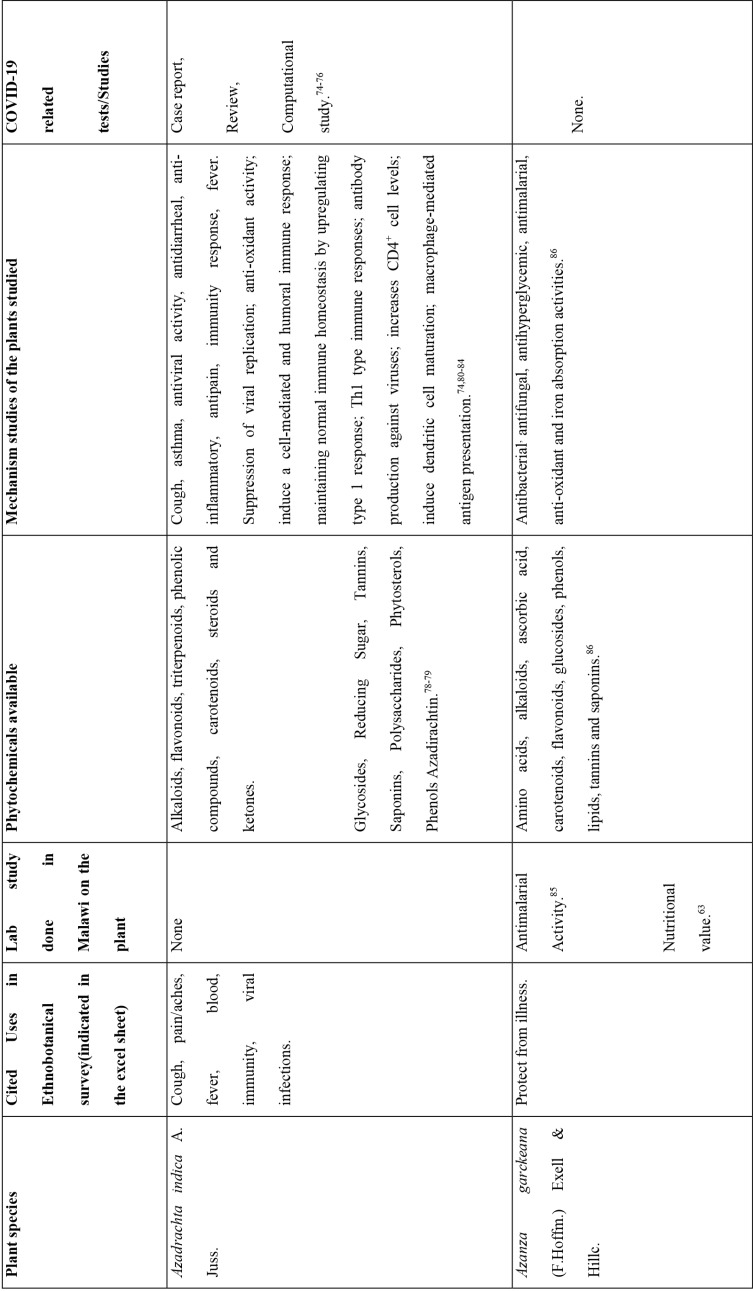

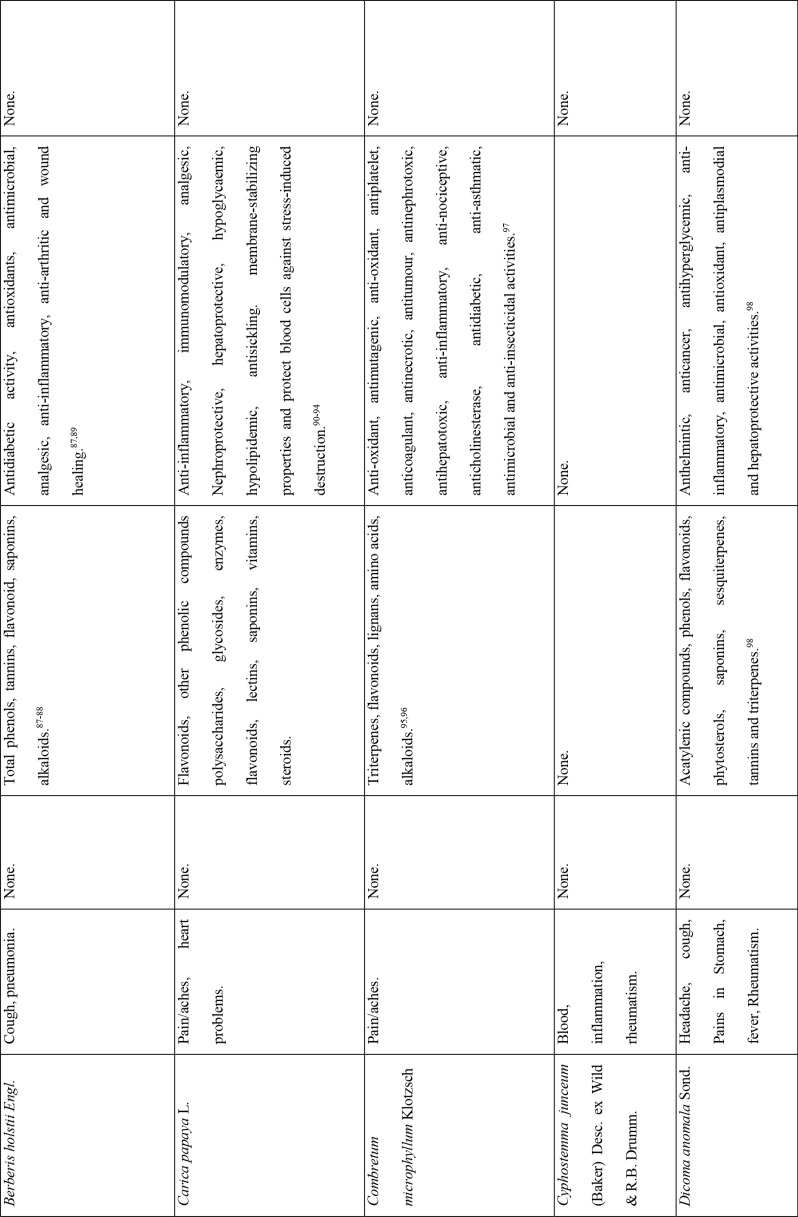

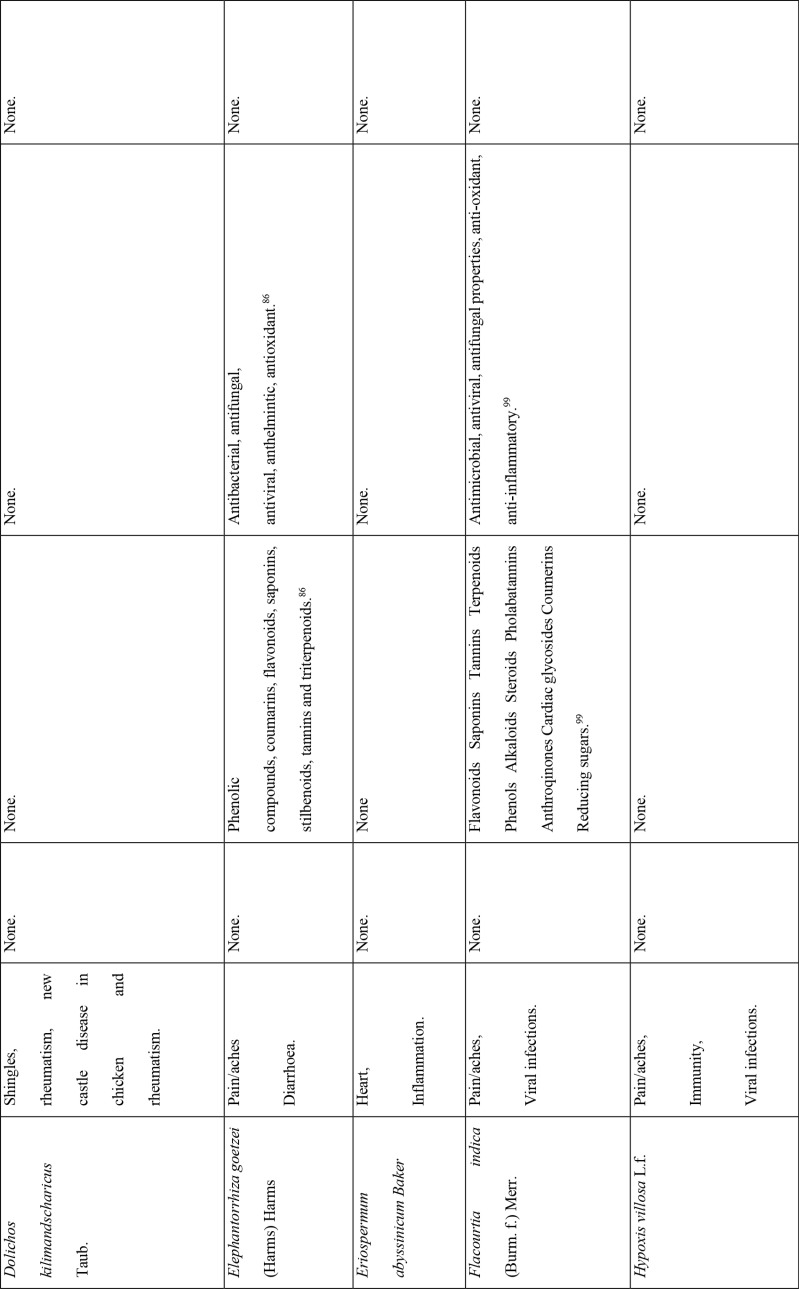

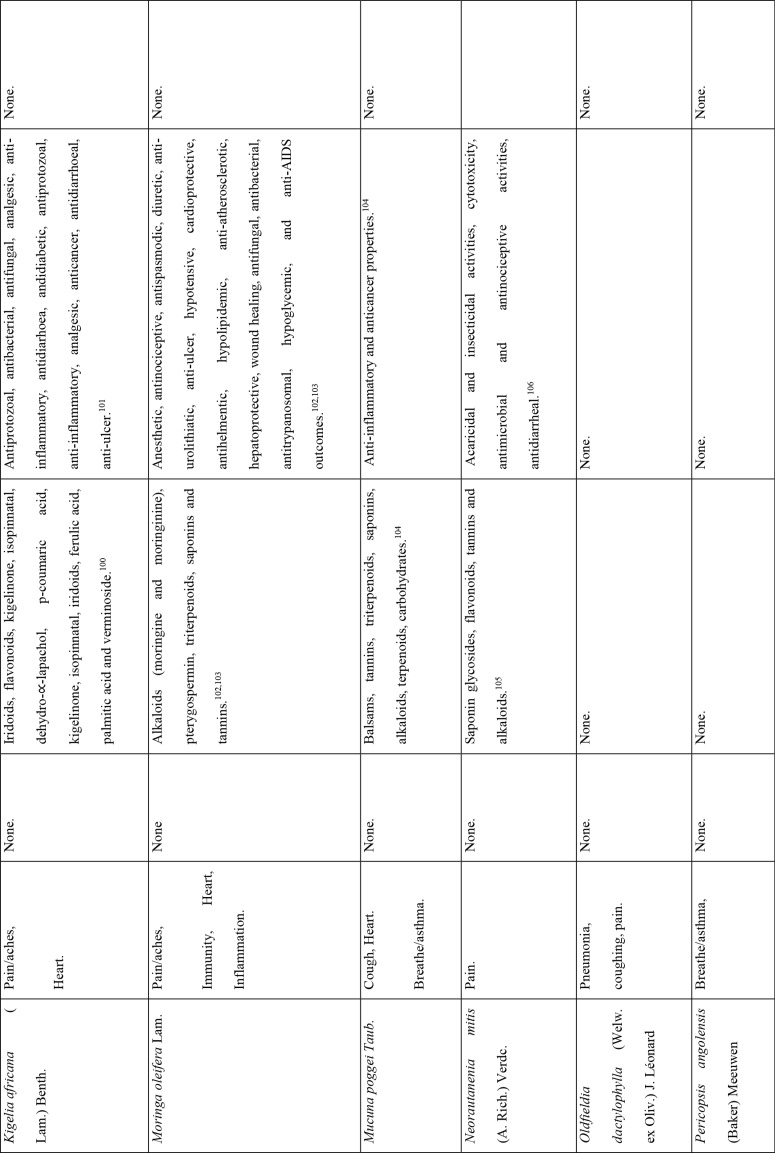

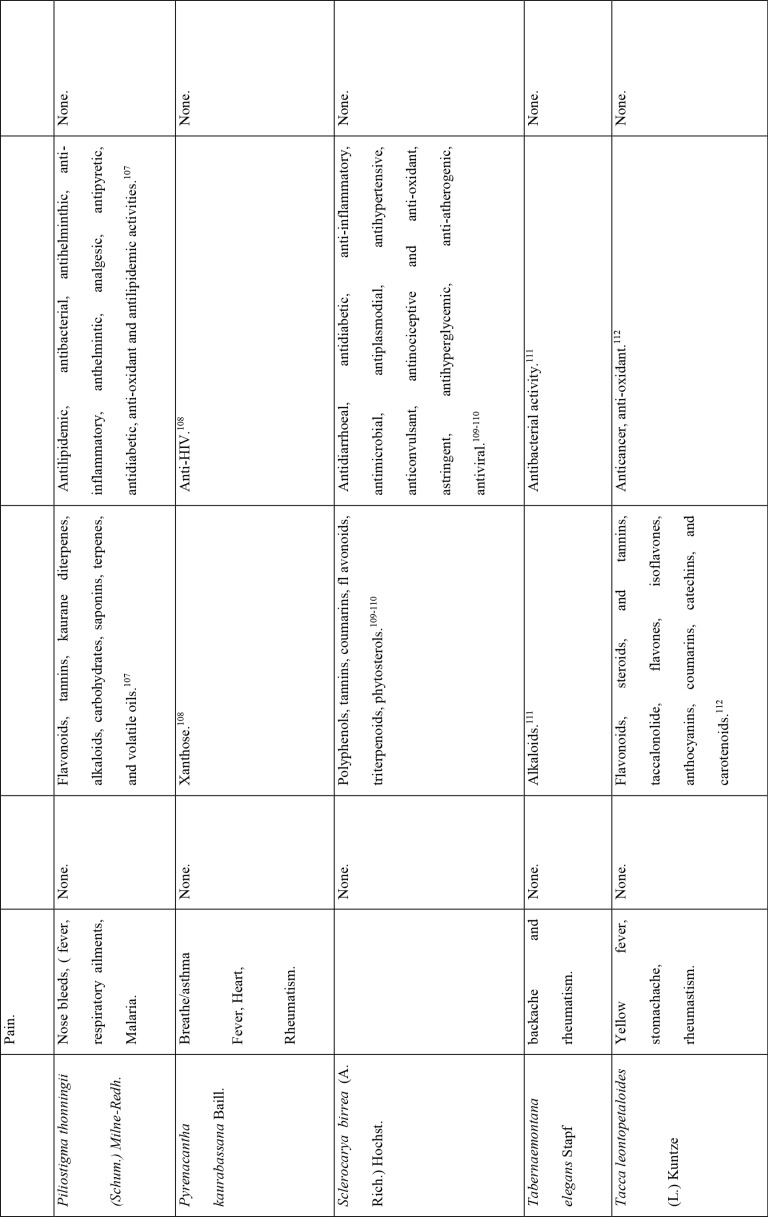

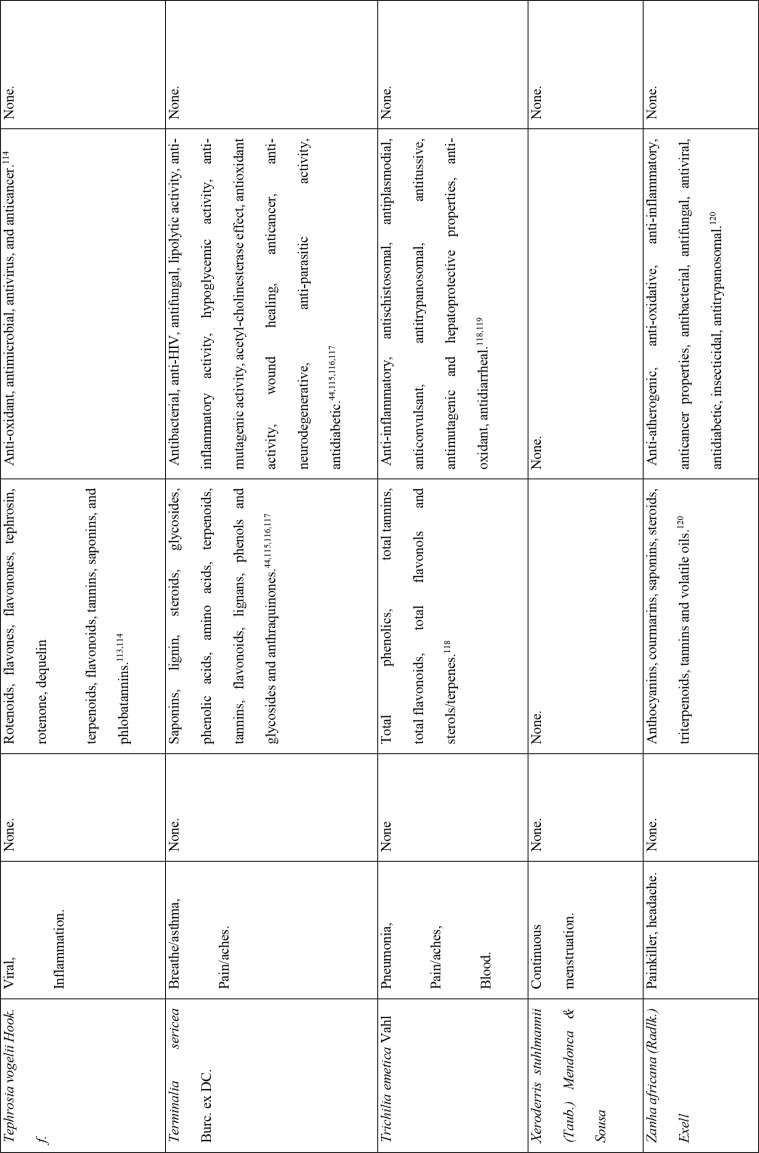

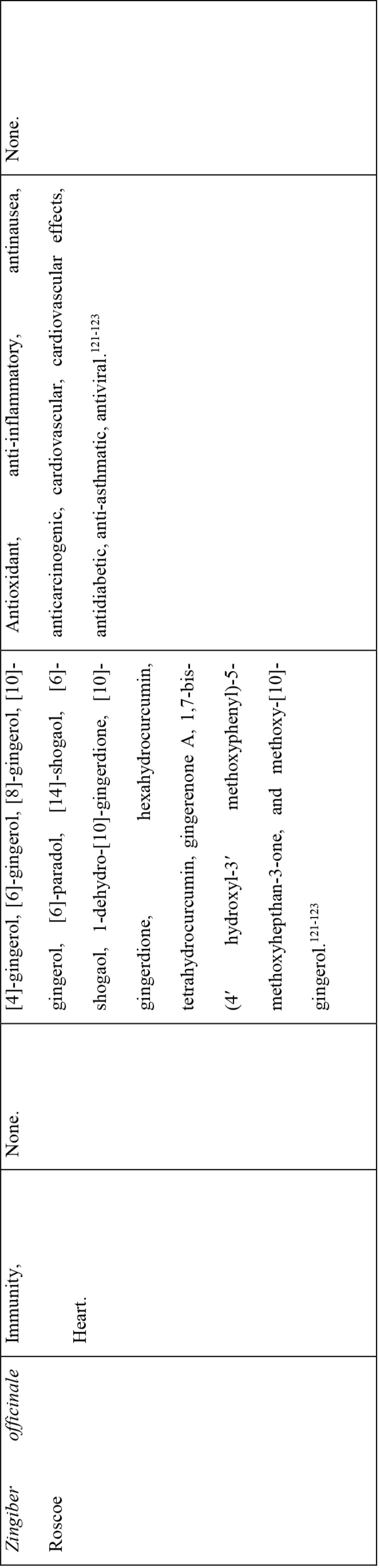

Table 4.

Medicinal plants used on more than one COVID-19 related disease

Pharmacological effects of the plants

The 30 plants with activity against one or more aspects of COVID-19 were considered more user-friendly since one entity can be used for multiple purposes. This may lead to a decreased incidence of toxicity and interactions. However, it should also be pointed out that the use of medicinal plants potentially leads to the administration of multiple active compounds (drug promiscuity), and is dangerous as it risks drug resistance and adverse events from unknown drug-drug interactions. Some of the components therein would be administered to the patient in suboptimal doses and others in overdoses, with chances of drug resistance and toxicity.71

On the other hand, documented evidence exists that suggests that the use of more than one medicinal plant (polyherbalism) improves the efficacy of the products as well as convenience for patients during administration (dose and frequency). Research also suggests that combining medicinal plants with more than one pharmacological effect can provide even greater benefit.72 Therefore, the 30 plants with multiple COVID-19 activities were evaluated further using literature review to determine if any studies had been completed to scientifically confirm their traditional ethnobotanical uses. Table 5 shows a summary of studies done so far on the plants. The table shows that the majority of the medicinal plants had phytochemicals linked to several of their COVID-19 symptoms alleviation capabilities and had demonstrated some mechanism of action related to COVID-19 treatment pathways. A few medicinal plants had no studies conducted to confirm their use.

Table 5.

Literature Reported Pharmacological properties of medicinal plants with potential for use in COVID-19 disease

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that there are multiple medicinal plants in Malawi that are being used for disease state management (Additional File 1: Table 1) and that several of these diseases are symptoms associated with COVID-19 (Additional File 2: Table 2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with mild COVID-19 are recommended to be treated with medicines that manage the presenting symptoms.55

The WHO acknowledges that traditional medicines may be sources of new therapies in the search for potential treatments for COVID-19. This is based on the historical integration of medicinal plants into primary healthcare in many areas of the world and on phytochemicals serving as precursor molecules for several commonly used biomedical drugs.55 This study was completed as a way of supplementing in the search for therapies for COVID-19 since initial selection of potential plant species for plant-derived lead compounds or medicines stems from ethnobotanical surveys. Since the disease is novel, we could not identify a novel medicinal entity with clinically significant SARS-COV-2 activity. However, plants targeting other viruses and associated symptoms might be repurposed in a similar fashion to various conventional medicines.73 However, the WHO warns against the use of traditional medicines without evaluating them first for efficacy, toxicity, and safety. Although WHO recognizes that traditional, complementary and alternative medicines show beneficial effects, and that Africa has a long history of traditional medicine use, medicinal plants can also be toxic and medicinal plants' efficacy may vary due to differences in geographical locations.55,59,73

The majority of the 30 medicinal plants identified contained known phytochemicals (Table 4 and 5). The review of the pharmacological effects of the plants confirms why they have potential for testing in the management of COVID-19 patient symptoms and eliminating the virus. The results, for example on Azadrachta indica, are consistent with the results reported by Roy and Bhattacharyya (2020), Shanmuga (2020), as well as Shanmuga et al., (2020) that also showed the potential of this plant in review, computational work, and clinical case study respectively.74–76 Furthermore, the study results are similar to those of Li et al who describe the Shufeng Jiedu Capsule/Granule (SFJD) containing eight medicinal herbs in China that is reported to have antiviral, antibacterial, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory activities, and have effective protection against lung injury and neuronal loss achieved through enhancement of autophagy and apoptosis reduction in rats with allergic rhinitis.77 It is also reported to improve Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced upper respiratory tract infection by acting on various targets, particularly ERK phosphorylation. When combined with oseltamivir treatment, SFJD reduced IAV-induced airway inflammation and pulmonary virus titres. This suggests that SFJD may be used for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases by regulating various signal pathways.77

This study can assist WHO's efforts to select traditional medicine products that can be investigated for clinical efficacy and safety in COVID-19. The WHO has historically supported clinical trials of traditional medicine products.

Through these previous WHO trials, 89 products have been given market authorisation in 14 countries after meeting international and national requirements for registration. Furthermore, 43 products were included in national essential medicines lists for diseases including malaria, opportunistic infections related to HIV, diabetes, sickle cell disease and hypertension.55 This report recommends that the medicinal plants identified be evaluated as potential sources of COVID-19 management remedies and be prioritized for inclusion in clinical and analytical studies for antiviral activity or management of COVID-19 disease.

Conclusions

Coronaviruses have been in existence for decades and novel strains will continue to emerge. Efforts to find viable, safe and effective treatments in drug discovery pipelines are continuing and will adapt in response to evolving strains. From various community practices across the world, natural products have played a significant role in managing coronavirus related diseases to varying extents. As the aetiology of COVID-19 disease is studied further at the molecular and enzyme levels, a narrower selection can be made for potential hits and leads effective against the disease. Natural products, including plant products, are undoubtedly a promising source of compounds in drug development for possible drug leads and vaccines. It is recommended that multidisciplinary approaches are used to study active phytochemicals with regard to identifying suitable compounds that can be used as they are or developed into possible treatments against Covid-19 and other related coronavirus diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr David Scott for assisting with the editing of the paper.

References

- 1.Parvez MK, Parveen S. Evolution and Emergence of Pathogenic Viruses: Past, Present, and Future. Intervirology. 2017;60(1–2):1–7. doi: 10.1159/000478729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball MJ, Lukiw WJ, Kammerman EM, Hill JM. Intracerebral propagation of Alzheimer's disease: strengthening evidence of a herpes simplex virus etiology. Alzheimers Dem. 2013;9(2):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hober D, Sane F, Jaïdane H, Riedweg K, Goffard A, Desailloud R. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: role of antibodies enhancing the infection with Coxsackievirus-B in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immuno. 2012;168(1):47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:329–337. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrington CS, Coates PJ, Duprex WP. Viruses and disease: emerging concepts for prevention, diagnosis and treatment. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):149–152. doi: 10.1002/path.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christou L. The global burden of bacterial and viral zoonotic infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):326–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cascio A, Bosilkovski M, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Pappas G. The socio-ecology of zoonotic infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grais RF, Strebel P, Mala P, Watson J, Nandy R, Gayer M. Measles vaccination in humanitarian emergencies: a review of recent practice. Confl Health. 2011;5(2):21. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CC, Hsu LT, Lin WC. Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. J Trad complement. 2014;4(1):24–35. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.124335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhal T. A Review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J Paediat. 2020;87(4):281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Chang H. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell. 2020;181(4):914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R, Enjuanes L, Gorbalenya AE, Holmes KV, et al. Family Coronaviridae. In: King AM, Lefkowitz E, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, International Union of Microbiological Societies. Virology Division, author, editors. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Oxford: Elsivier; 2011. pp. 806–1820. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo PC, Huang Y, Lau SK, Yuen KY. Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis. Viruses. 2010;2(8):1804–1820. doi: 10.3390/v2081803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, author. “ICTV Master Species List 2009—v10”. (2010-08-24) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richman DD, Whitley RJ, Hayden FG. Clinical Virology. 4th ed. Washington: ASM Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JL, Ha TKQ, Oh WK. Discovery of inhibitory materials against PEDV corona virus from medicinal plants. The Japanese J Veteri Res. 2016;64:553–563. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xinhua, author. China's CDC detects a large number of new coronaviruses in the South China seafood market in Wuhan. 2020. [Online] https://www.xinhuanet.com/2020-01/27/c_1125504355.htm.

- 19.Kim JM, Chung YS, Jo HJ, Lee NJ, Kim MS, Woo SH, et al. Identification of Coronavirus Isolated from a Patient in Korea with COVID-19. Osong pub health res perspect. 2020;11(1):3–7. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.1.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyama T, Platt D, Parida L. Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation. 2020;98:495–504. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.253591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, Yu J, Kang M, Song Y, Xia J, Guo Q, Song T, He J, Yen HL, Peiris M, Wu JN. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organisation (WHO), author Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC precaution recommendations. 2020. Mar 29, [20/09/2020]. [Online] https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/

- 25.Cheng ZJ, Shan J. 2019 novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know. Infection. 2020;48(2):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furukawa NW, Brooks JT, Sobel J. Evidence supporting transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 while presymptomatic or asymptomatic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):e201595. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.201595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wark P. Here's what we know so far about the long-term symptoms of COVID-19. The Conversation. 2020. Jul 26, [20/09/2020]. www.theconversation.com/heres-what-we-know-so-far-about-the-long-term-symptoms-of-covid-19-142722.

- 28.Harvard Medical School, author. COVID-19 basics; Symptoms, spread and other essential information about the new coronavirus and COVID-19. Harvard Health Publishing; 2020. [23/09/2020]. www.health.havard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-basics. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dell'Era V, Farri F, Garzaro G, Gatto M, Valletti PA, Garzaro M. Smell and taste disorders during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study on 355 patients. Head Neck. 2020;42(7):1591–1596. doi: 10.1002/hed.26288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panyod S, et al. Dietary therapy and herbal medicine for COVID-19 prevention: A review and perspective. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine. 2020;10(4):420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beigel JH, Finberg RW, ACTT-1 Study Group Members . Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. COVID-19 Publications by UMMS Authors. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus [2019-nCoV] infected pneumonia [standard version] Mil Med Res. 2020;7(4) doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L, Liu YJ. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. Med Virol. 2020;92(5):479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Expert consensus on chloroquine phosphate for the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia, author. Multicenter collaboration group, Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province and Health Commission of Guangdong Province, Chloroquine in the treatment of novel corona. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(0):E019. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States., Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team. Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao JP, Hu Y, Du RH, et al. Expert consensus on the use of corticosteroid in patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43:E007. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Covid-19: Demand for dexamethasone surges as RECOVERY trial publishes preprint. BMJ. 2020:369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aanouz I, Belhassan A, Khatabi KE, Lakhlifi T, Idrissi ME, Bouachrine M, Moroccan Medicinal. plants as inhibitors of COVID-19: Computational investigations. J Biomolec Structure and Dynam. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1758790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soleymani S, Zabihollahi R, Shahbazi S, Bolhassani A. Antiviral effects of saffron and its major ingredients. Curr Drug Deliv. 2018;15(5):698–704. doi: 10.2174/1567201814666171129210654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boff L, et al. Potential anti-herpes and cytotoxic action of novel semisynthetic digitoxigenin-derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;167:546–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Astani A, Reichling J, Schnitzler P. Screening for antiviral activities of isolated compounds from essential oils. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang XR, Kaunda JS, Zhu HT, Wang D, Yang CR, Zhang YJ. The Genus Terminalia (Combretaceae): An Ethnopharmacological, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2019;9:357–392. doi: 10.1007/s13659-019-00222-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo H, Tang Q, Shang Y, et al. Can Chinese Medicine Be Used for Prevention of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? A Review of Historical Classics, Research Evidence and Current Prevention Programs. Chinese J Integ Med. 2020;26:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s11655-020-3192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong X, Wang P, Su K, Cho WC, Xing Y. Chinese herbal medicine for coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacological research. 2020;160(105056) doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li SY, Chen C, Zhang HQ, Guo HY, Wang H, Wang L, et al. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antiviral research. 2005;67(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu MS, Lee J, Lee JM, et al. Identification of myricetin and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus helicase, nsP13. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22(12):4049–4054. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mani JS, Johnson JB, Steel JC, et al. Natural product-derived phytochemicals as potential agents against coronaviruses: A review. Virus Res. 2020;284:197989. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryu YB, Jeong HJ, Kim JH, Kim YM, Park JY, Kim D, et al. Biflavonoids from Torreya nucifera displaying SARS-CoV 3CL (pro) inhibition. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18(22):7940–7947. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lau KM, Lee KM, Koon CM, Cheung CS, Lau CP, Ho HM, et al. Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. J ethnopharm. 2008;118(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Chen X, Lu Y, Chen F, Zhang W. Clinical characteristics and therapeutic procedure for four cases with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia receiving combined Chinese and Western medicine treatment. BioSci Trends. 2020;14(1):64–68. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oyebode O, Kandala NB, Chilton PJ, Lilford RJ. Use of traditional medicine in middle-income countries: a WHO-SAGE study. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(8):984–991. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang D, Wu K, Zhang X, Deng S, Peng B. In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. J Integ Med. 2020;18(1):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organisation (WHO), author WHO supports scientifically-proven traditional medicine. 2020. [25/07/2020]. www.afro.who.int/news/who-supp.

- 56.Loayza NV. Costs and Trade-Offs in the fight against the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Developing Country Perspective (English). Research and Policy Briefs. Washington DC: World Bank Group; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gadabu A. Malawi's Response, Risk Factors, and Preparedness for COVID-19. North American Academic Research -NAAR. 2020;3(4) doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3732795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rajagopal D. Hydroxychloroquine becomes a Schedule H1 drug as hoarding leads to shortage. Economics Times. 2020 Mar 27; www.economictmes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/pharmaceuticals/hydroxychloroqine-becomes-a-schedule-h1-drug-as-hoarding-leads-to-shortage/articlesshow/74842650.cms. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nafiu MO, Hamid AA, Muritala HF, Adeyemi SB. Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa. 2017. Chapter 7 - Preparation, Standardization, and Quality Control of Medicinal Plants in Africa; pp. 171–204. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chikowe I, Mnyenyembe M, Jere S, Mtewa AG, Mponda J, Lampiao F. An ethnomedicinal survey of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants in the traditional authority Chikowi in Zomba, Malawi. Current Traditional Medicine. 2020;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mwafongo E, Nordal I, Magombo Z, Stedje B. Ethnobotanical study of Hyacinthaceae and non-hyacinthaceous geophytes in selected districts of Malawi. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2010;8:75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson L, Sclar D, Scaer T. Medicinal Plant Use by Traditional Healers in Malawi: Focus on Neem, Tephrosia, Moringa, Jatropha, Marula and Natal Mahogany. Malawi Agroforestry Extension Project. 2002:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saka JD, Msonthi JD. Nutritional value of edible fruits of indigenous wild trees in Malawi. For Ecol Manage. 1994;64:245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manda L. Status and uses of Oldfieldia dactylophylla (Euphorbiaceae) in Malawi. Uppsala, Sweden: 2007. Uppsala: CBM Master Theses No. 38. Swedish Biodiversity Centre (CBM), SLU, Box 7007, SE-750 07. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maliwichi-Nyirenda CP, Maliwichi LL. Medicinal plants used for contraception and pregnancy-related cases in Malawi: A case study of Mulanje District. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2010;4(20):3024–3030. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gordon CN. People and protected areas: Natural resource harvesting as an approach to support rural communities surrounding Majete Wildlife Reserve, Southern Malawi. South Africa: Stellenbosch University; 2017. Capetown : Masters thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bundschuh TV, Hahn K, Wittig R. The Medicinal Plants of the Woodlands in northern Malawi (Karonga District) Flora et Vegetatio Sudano-Sambesica. 2011;14:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maliwichi-Nyirenda CP. The conservation biology of Berberis holstii engl. in Nyika national park, Malawi. Plymouth: University of Plymouth Research Theses; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kayambazinthu D, Barany M, Mumba R, Anyonge CH. Miombo woodlands and HIV/AIDS interactions: Malawi Country Report. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Forestry Policy and Institutions Working Paper 6. Rome: FAO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chisaka JW. The use of traditional herbal medicines among palliative care patients at Mulanje Mission Hospital, Malawi. Capetown: Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Capetown; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mei Y, Yang B. Rational application of drug promiscuity in medicinal chemistry. Future medicinal chemistry. 2018;10(15) doi: 10.4155/fmc-2018-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parasuraman S, Thing GS, Dhanaraj SA. Polyherbal formulation: Concept of ayurveda. Pharmacogn Rev. 2014;8(16):73–80. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.134229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang Y. Use of herbal drugs to treat COVID-19 should be with caution. The Lancet. 2020;395(10238):395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31143-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roy S, Bhattacharyya P. Possible role of traditional medicinal plant Neem (Azadirachta indica) for the management of COVID-19 infection. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2020;11(SPL1):122–125. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shanmuga SS. Some Compounds from Neem leaves extract exhibit binding affirnity as high as -14.3 kcal/mol against COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro): A Molecular Docking Study. Molecular Biology. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs.2564/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shanmuga SS, Kanitkar PM, Neeta, Shirish K. Neem (Azadirachta Indica) leaves in the treatment of COVID19/SARS-CoV-2 : A Case Report. Figshare. 2020 Figshare. Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li C, Wang L, Ren L. Antiviral mechanisms of candidate chemical medicines and traditional Chinese medicines for SARS-CoV-2 infection [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 24] Virus Res. 2020;286(198073) doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ramadass N, Subramanian N. Study of phytochemical screening of neem (Azadirachta indica) Int J Zoo Studies. 2018;3(1):209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dash SP, Dixit S, Sahoo S. Phytochemical and Biochemical Characterizations from Leaf Extracts from Azadirachta Indica: An Important Medicinal Plant. Biochem Anal Biochem. 2017;6(323) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Arora R, Chawla R, Marwah R, et al. Potential of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Preventive Management of Novel H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu) Pandemic: Thwarting Potential Disasters in the Bud. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/586506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhowmik D, Chiranjib, Yadav J, Tripathi KK, Kumar KPS. Herbal Remedies of Azadirachta indica and its Medicinal Application. J Chem Pharm Res. 2010;2(1):62–72. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hannan A, Khan SA, Choudhry, et al. Antibacterial activity of Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf extracts against wound causing bacteria. Healthmed. 2014;8(6):767–773. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lakshmi T, Krishnan V, Rajendran R, Madhusudhanan N. Azadirachta indica: A herbal panacea in dentistry - An update. Pharmacogn Rev. 2015;9(17):41–44. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.156337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alzohairy MA. Therapeutics Role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and Their Active Constituents in Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7382506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Connelly MP, Fabiano E, Patel IH, Kinyanjui SM, Mberu EK, Watkins WM. Antimalarial activity in crude extracts of Malawian medicinal plants. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90(6):597–602. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maroyi A. Azanza garckeana Fruit Tree: Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Nutritional and Primary Healthcare Applications as Herbal Medicine: A Review. Res J Med Plants. 2017;11:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yusuf AA, Lawal B, Sani S, et al. Pharmacological activities of Azanza garckeana (Goron Tula) grown in Nigeria. Clin Phytosci. 2020;6:27. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Srivastava S, Srivastava M, Misra A, Pandey G, Rawat A. A review on biological and chemical diversity in Berberis (Berberidaceae) EXCLI J. 2015;14:247–267. doi: 10.17179/excli2014-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kimani NL, Njangiru IK, Njagi ENM, Orinda GO. Antidiabetic activity of administration of aqueous extract of Berberis holstii. J Diabetes Metab. 2017;8 11. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pathy K. The Influenza a Virus Subtypes H1N1, H1N2 and H3N2, HDFx: A Novel Immunomodulator and Potential Fighter Against Cytokine Storms in Viral Flu Infections-Carica Papaya Linn. Int J clin Case. 2017;1(8):159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saeed F, Arshad MU, Pasha I, Naz R, Batool R, Khan AA, et al. Nutritional and Phyto-Therapeutic Potential of Papaya (Carica Papaya Linn.): An Overview. International Journal of Food Properties. 2014;17(7):1637–1653. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ahmad N, Fazal H, Ayaz M, Abbasi BH, Mohammad I, Fazal L. Dengue fever treatment with Carica papaya leaves extracts. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1(4):330–333. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Srikanth BK, Reddy L, Biradar S, Shamanna M, Mariguddi DD, Krishnakumar M. An open-label, randomized prospective study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Carica papaya leaf extract for thrombocytopenia associated with dengue fever in pediatric subjects. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2019;10:5–11. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S176712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Priyadarshi A, Ram B. A review on pharmacognosy, phytochemistry and pharmacological activity of Carica papaya (linn) leaf. Int J Pharm Sci & Res. 2018;9(10):4071–4078. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bhatnagar S, Sahoo S, Mohapatra AK, Behera DR. Phytochemical analysis, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic activity of medicinal plant Combretum roxburghii (Family: Combretaceae) Int J Drug Dev & Res. 2012;4(1):193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 96.de Morais LGR, de Sales IRP, Caldas FMRD, et al. Bioactivities of the genus Combretum (Combretaceae): A review. Molecules. 2012;17:9142–206. doi: 10.3390/molecules17089142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Makhafola TJ, Elgorashi EE, McGaw LJ, Awouafack MD, Verschaeve L, Eloff JN. Isolation and characterization of the compounds responsible for the antimutagenic activity of Combretum microphyllum (Combretaceae) leaf extracts. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):446. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1935-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maroyi A. Dicoma anomala sond: A review of its botany, ethnomedicine, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Asian J Pharmaceut Clin Res. 2018;11(6):70. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eramma N, Gayathri D. Antibacterial potential and phytochemical analysis of Flacourtia indica (Burm.f.) Merr. root extract against human pathogens. Indo American J Pharmaceut Res. 2013;3:3832–3846. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Adesina, et al. Plants in Respiratory Disorders II-Antitussives, A Review. BJPR. 2017;16(3):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sunday B, Atawodi E, Olowoniyi OD. Pharmacological and Therapeutic Activities of Kigelia africana (Lam.) Ann Res Rev Bio. 2015;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singh L, Singh J, Singh J. Medicinal and Nutritional Values of Drumstick Tree (Moringa oleifera):A Review. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2019;8(05):1965–1974. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Asnaashari S, Dastmalchi S, Javadzadeh Y. Gastroprotective effects of herbal medicines (roots) Int J Food Prop. 2018;21(1):902–920. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Oko AO, Ekigbo JC, Idenyi JN. Nutritional and Phytochemical Compositions of the Leaves of Mucuna Poggei. J Bio Life Sci. 2012;3(1):232. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vongtau H, Amos S, Hohn-Africa LB. Pharmacological effects of the aqueous extract of Neorautanenia mitis in rodents. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;72(1–2):207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dawurung CJ, Gotep JG, Usman JG, Elisha IL, Lombin LH, Pyne SG. Antidiarrheal activity of some selected Nigerian plants used in traditional medicine. Phcog Res [serial online] 2019;11:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Afolayan M, Srivedavyasasri R, Asekun OT, Familoni OB, Orishadipe A, Zulfiqar F, et al. Phytochemical study of Piliostigma thonningii, a medicinal plant grown in Nigeria. Med Chem Res. 2018;27:2325–2330. doi: 10.1007/s00044-018-2238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Omolo JJ, Maharaj V, Naidoo D, Klimkait T, Malebo HM, Mtullu S, Lyaruu HM, de Koning CB. Bioassay-Guided Investigation of the Tanzanian Plant Pyrenacantha kaurabassana for Potential Anti-HIV-Active Compounds. J Nat Prod. 2012;75(10):1712–1716. doi: 10.1021/np300255r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Russo D, Kenny O, Smyth T, Milella L, Hossain M, Diop M, Rai D, Brunton N. Profiling of Phytochemicals in Tissues from Sclerocarya birrea by HPLC-MS and Their Link with Antioxidant Activity. ISRN Chromatography. 2013:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 110.John AO, Ojewole, Mawoza T, Witness DH, Chiwororo, Peter MO. Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich) Hochst. ['Marula'] (Anacardiaceae): A Review of its Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicology and its Ethnomedicinal Uses. Phytother Res. 2010;24:633–639. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pallant CA, Cromarty AD, Steenkamp V. Effect of an alkaloidal fraction of Tabernaemontana elegans (Stapf.) on selected micro-organisms. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(2):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hapsari BW, Martin AF, Maulana E, Ermayanti TM. Growth, phytochemical properties, and antioxidant activity of in vitro-gamma irradiated Tacca leontopetaloides (L.) Kuntze. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2019:2199. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mkindi AG, Tembo Y, Mbega ER, et al. Phytochemical Analysis of Tephrosia vogelii across East Africa Reveals Three Chemotypes that Influence Its Use as a Pesticidal Plant. Plants (Basel) 2019;8(12):597. doi: 10.3390/plants8120597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yadeta NC, Tessema SS. Phytochemical Investigation and characterisation of the chemical cosntituents from root extracts of Tephrosia vogelli. International Journal of Novel Research in Engineering and Science. 2019;6(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mongaloa NI, McGawa LJ, Segapelod TV, Finniea JF, Van Staden VJ. Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, toxicology and pharmacological properties of Terminalia sericea Burch. ex DC. (Combretaceae) – A review. J Ethnopharm. 2016;194:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Viol DI. Screening of traditional medicinal plants from Zimbabwe for phytochemistry, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral and toxicological activities. School of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, University of Zimbabwe Thesis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cock IE. The medicinal properties and phytochemistry of plants of the genus Terminalia (Combretaceae) Inflammopharmacol. 2015;23(5):203–229. doi: 10.1007/s10787-015-0246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Konate K, Yomalan K, Sytar O, Brestic M. Antidiarrheal and antimicrobial profiles extracts of the leaves from Trichilia emetica Vahl. (Meliaceae)KK. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2015;5(3):242–248. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brigitte KML, Flaurant TT, Emmanuel T. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Protective Effect of Methanol Extract of Trichilia emetica (Meliaceae) Stem and Root Bark against Free Radical-induced Oxidative Haemolysis. EJMP [Internet] 2017;19(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Maroyi A. Zanha africana (Radlk.) Exell: review of its botany, medicinal uses and biological activities. Pharm Sci & Res. 2019;11(8):2980–2985. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bode AM, Dong Z. Chapter 7. The Amazing and Mighty Ginger. In: Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, editors. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chang JS, Wang KC, FengYeh CF, Shieh DE, Chiang LC. Fresh ginger (Zingiber officinale) has anti-viral activity against human respiratory syncytial virus in human respiratory tract cell lines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;145(1):146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Koh EM, Kim HJ, Kim S, et al., editors. Modulation of macrophage functions by compounds isolated from Zingiber officinale. Planta Med. 2009;75(2):148–151. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol. 2013;87(14):7790–7792. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]