Abstract

Background:

Dimethandrolone (DMA) and 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone (11β-MNT) are two novel compounds with both androgenic and progestational activity that are under investigation as potential male hormonal contraceptives. Their metabolic effects have never been compared in men.

Objective:

Assess for changes in insulin sensitivity and adiponectin, and compare the metabolic effects of these two novel androgens.

Materials/Methods:

In two clinical trials of DMA undecanoate (DMAU) and 11β-MNT dodecylcarbonate (11β-MNTDC), oral prodrugs of DMA and 11β-MNT, healthy men received drug or placebo for 28 days. Insulin and adiponectin assays were performed on stored samples. Mixed model analyses were performed to compare the effects of the two drugs. Student’s t-test, or the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate, was used to evaluate for an effect of active drug versus placebo.

Results:

Class effects were seen, with decrease in HDL-C and SHBG, and increase in weight and hematocrit, with no statistically significant differences between the two compounds. No changes in fasting glucose, fasting insulin, or HOMA-IR were seen with either compound. There was a slight decrease in adiponectin with DMAU that was not seen with 11β-MNTDC. An increase in LDL-C was seen with 11β-MNTDC but not with DMAU.

Discussion:

There were no significant changes in insulin resistance after 28 days of oral administration of these novel androgens despite a mild increase in weight. There may be subtle differences in their metabolic impacts that should be explored in future studies.

Conclusion:

Changes in metabolic parameters should be carefully monitored when investigating androgenic compounds.

Keywords: Androgen, progestin, male hormonal contraception

Introduction

Male hormonal contraceptives reduce spermatogenesis by suppressing gonadotropin secretion from the pituitary gland; however, gonadotropin suppression also reduces endogenous testosterone production so administration of testosterone or another androgen is required to prevent symptomatic hypogonadism. Spermatogenesis can be suppressed to levels that reduce the chance of pregnancy to levels comparable to that of female oral contraceptives [1, 2]. The addition of a progestin to the androgen has been shown to improve the rapidity and reliability of sperm suppression, and decrease the dosage of androgen required for effective contraception [3–6].

Questions have been raised regarding the potential metabolic effects of androgen-progestin combinations used in male hormonal contraception studies and the potential for long term consequences on cardiovascular health [7], including the development of the metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, central obesity) or type 2 diabetes [8, 9]. Testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men has been shown in some studies to improve insulin sensitivity; the effects of testosterone on metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in men are less consistent [10–12]. Androgens decrease HDL-C, but their effects on LDL-C are generally neutral when administered intramuscularly or transdermally [13–15]. Progestins have been shown to worsen insulin sensitivity in healthy men, with improvement once testosterone is added [16]. The effects of progestins on LDL-C are not as well studied, but one trial in men showed that LDL-C declined by 6–7% in participants receiving the androgenic progestin levonorgestrel with testosterone [17]. Accordingly, combined androgen-progestin male contraceptives might be expected to reduce HDL-C, and have no effect on, or possibly reduce, LDL-C.

Adiponectin, produced by adipose cells, improves insulin sensitivity [18]. Counter-intuitively, adiponectin levels are lower with increased body mass index (BMI) [19]. Furthermore, it is thought that low adiponectin levels contribute to insulin resistance and the increased cardiovascular risk associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome [20]. However, meta-analyses of multiple studies have shown that elevated adiponectin levels are associated with increased mortality [21, 22]; thus the contribution of adiponectin to overall health remains unclear. Suppression of testosterone in men increases adiponectin levels [23], and exogenous testosterone suppresses adiponectin levels at least in part due to impaired secretion of high molecular weight adiponectin [24]. The effects of androgen-progestin combinations on adiponectin levels are not well established.

Dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU, 7α,11β-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone undecanoate) and 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone dodecylcarbonate (11β-MNTDC) are oral prodrugs of two synthetic androgens with progestational activity. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that their active metabolites, DMA and 11β-MNT, have high androgen receptor binding affinity (several times higher than that of testosterone) and have progesterone receptor binding affinity lower than that of progesterone [25, 26]. These two 19-nortestosterone derivatives are not aromatizable and thus do not have estrogenic activity in vitro [27]. Phase 1 studies of oral DMAU and 11β-MNTDC in healthy men have demonstrated safety and tolerability when taken daily for 28 days [28, 29].

The effects of DMAU and 11β-MNTDC on weight and lipid profile were previously reported as safety information [28, 29], but never directly compared in a combined analysis. The effects of these two compounds on insulin resistance and adiponectin have never been examined in men. As male contraceptive regimens may be given to young and middle-aged men over prolonged periods, it is important to be cognizant of any changes in metabolic parameters with these hormones to help guide the choice of an androgen for further contraceptive development. This study analyzes and directly compares the effects of these novel compounds on metabolic parameters after 28 days of daily dosing in healthy men.

Research Participants and Methods

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in healthy men were previously performed to assess the safety and tolerability of DMAU and 11β-MNTDC taken orally for 28 days [28, 29]. The parent studies were conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Contraceptive Clinical Trials Network at The Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA and the University of Washington, Seattle, WA. The protocols for both studies were very similar. In brief, healthy men 18 – 50 years old with BMI ≤ 33 kg/m2 without clinical or laboratory evidence of any medical conditions were recruited (See Supplemental File [30]). All participants provided written informed consent before any study procedures. Most participants also consented to storage of samples and to future analyses of stored samples. Both studies were approved by the respective institutional review boards and a central IRB. The DMAU study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01382069 and the 11β-MNTDC study as NCT03298373.

Investigational drug

Dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU) was manufactured by Evestra Inc. (San Antonio, TX) or Ash Stevens, LLC (Riverview, MI). 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone dodecylcarbonate (11β-MNTDC) was manufactured by Ash Stevens, LLC. The oil capsules of both compounds were formulated as capsules containing 100 mg of active drug in castor oil/benzyl benzoate (70:30) under Good Manufacturing Practices by SRI International (Menlo Park, CA). Matching placebo capsules in castor oil/benzyl benzoate were manufactured by SRI International for both studies.

Study Design and Procedures

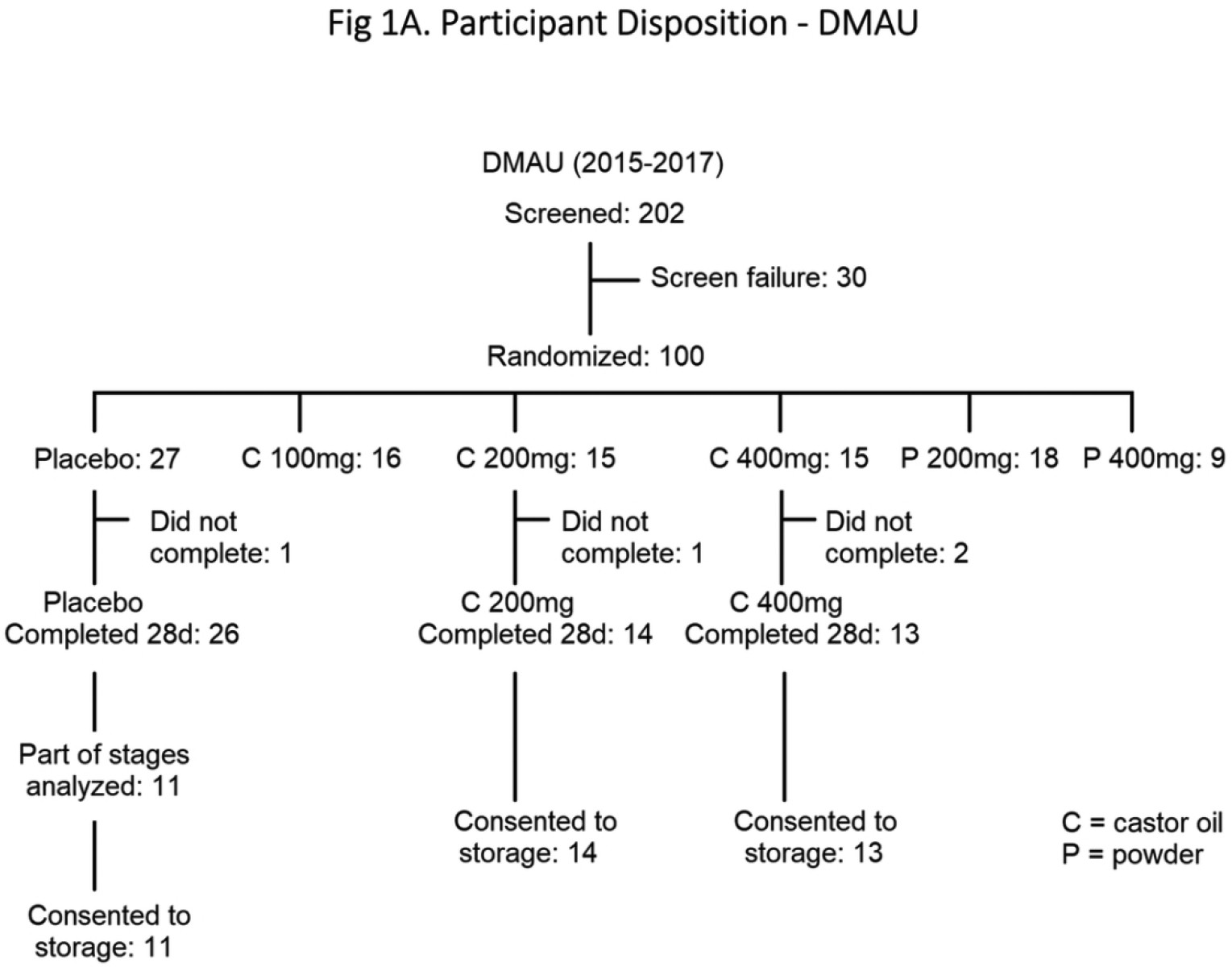

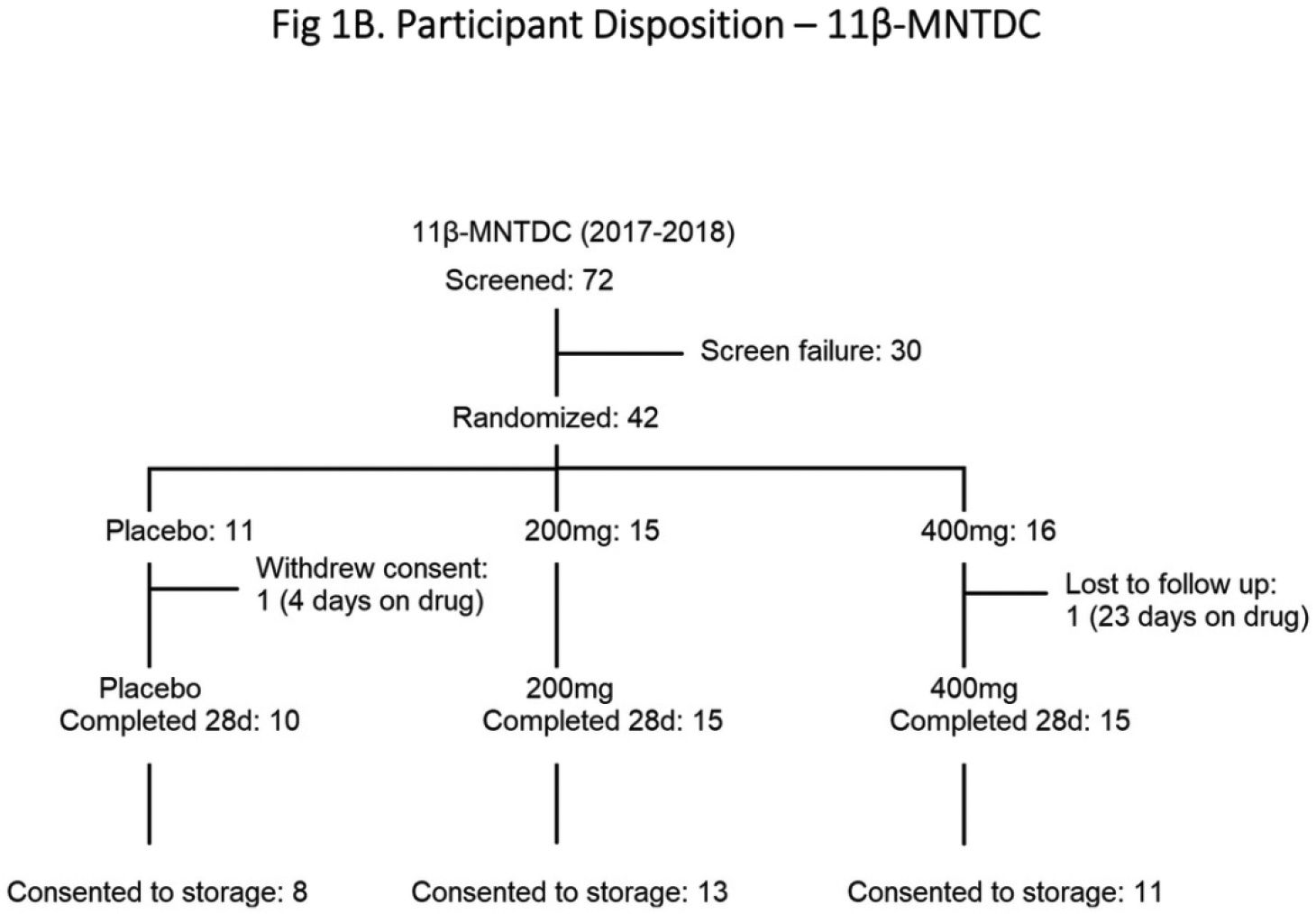

In the DMAU 28 day study (Fig. 1A), men were randomized to receive placebo or DMAU in a powder formulation (200 mg or 400 mg) or in castor oil:benzyl benzoate capsules (100 mg, 200 mg, or 400 mg). In the 11β-MNTDC 28 day study, men were randomized to receive placebo or 11β-MNTDC (200 mg or 400 mg) daily for 28 days (Fig. 1B). Randomization was performed by the data coordinating center, Health Decisions, using a 3:1 ratio (active: placebo), using a fixed block size and stratified by site. For each dosage group, 5 men received placebo and 15 men received active drug. They were instructed to take the pills with a glass of water immediately after a breakfast containing 25–30 g fat. Daily diaries were maintained by the participants, including the time of medication administration and the type of food consumed at breakfast. Participants were recruited in a stepwise manner, with safety assessments performed midway through each dosage group before finishing the dosage group and proceeding to the next higher dosage. Participants were seen twice weekly between days 1 and 28 for safety assessments, drug accountability, and blood draws. Participants exited the study when all safety parameters were within normal reference ranges.

Fig. 1.

Participant Disposition: (A) DMAU, (B) 11β-MNTDC

Insulin and adiponectin assays were performed on Day 1 and Day 28 serum samples stored at −20°C on the subset of participants who consented to future analyses of their samples.

Analytical methods

Serum DMAU, DMA, 11β-MNTDC, 11β-MNT, testosterone (T), estradiol (E2), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations were quantified by the Endocrine and Metabolic Research Laboratory at The Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center using validated methods [28, 29]. This same central laboratory also measured insulin and adiponectin concentrations in stored study samples. Safety laboratory assessments, which included fasting glucose and lipids, were measured locally at the respective licensed clinical laboratories.

Fasting insulin levels in stored samples were measured via electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay using a Roche platform (Cobas e411). The intra-assay variation was <11% and interassay variation <9%. The LLOQ was 0.2 mIU/L. Two participants who had highly discrepant insulin concentrations were excluded based on biological implausibility of fasting insulin levels > 75 mIU/L in the context of their other normal fasting insulin levels [31]. Adiponectin was measured by ELISA (EMD Millipore) using a Wallac Victor 2, 1420 Multilabel Counter. The intra-assay variation was <8% and interassay variation <9%. The LLOQ was 0.2 ng/mL. Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the formula (Fasting insulin mIU/L)*(Fasting glucose mg/dL) / 405 [32].

Outcomes Assessed In This Analysis

The main objective of this study is to assess the effects of active drug (either DMAU or 11β-MNTDC) versus placebo on selected metabolic parameters. We examined the effects of these compounds on fasting glucose, fasting insulin, insulin resistance, and adiponectin in men. We also sought to compare the impacts of the two drugs (DMAU versus 11β-MNTDC) on fasting cholesterol and weight. To be analogous to the 11β-MNTDC study, these analyses included the placebo, 200 mg oil capsules, and 400 mg oil capsules from the DMAU study, omitting the powder and 100 mg DMAU groups. The following metabolic parameters were assessed: fasting glucose; fasting insulin; HOMA-IR; adiponectin; body weight; LDL-C; HDL-C; triglycerides; and total cholesterol. Changes in hematocrit and SHBG were also compared as parameters affected by androgens. Adherence to breakfast dietary fat requirements for each day were assessed qualitatively via the participants’ food diaries.

Statistical analyses

The sample sizes (15 per dosage group) in both studies were proposed to provide a probability of at least 80% to detect serious adverse events or grade 3 adverse events occurring in 20% of men [30]. Post hoc power calculations showed that in this secondary analysis, we estimated a >80% power to see differences larger than an effect size (ANOVA f) of 0.4 with dosage group, and a >80% power to see differences larger than an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.7 with drug (DMAU or 11β-MNTDC). The changes in each outcome parameter from Day 1 to Day 28 were calculated for each participant; participants with missing data on Day 28 were excluded. Medians and interquartile ranges (25th, 75th percentiles) were provided for all parameters. Mixed linear regression models were used to compare the effects of the two drugs by evaluating the main effects of androgen type (DMAU or 11B-MNTDC), dosage group (0, 200, or 400 mg in castor oil), and dosage-drug interaction (example: while the two drugs may have similar effects in the placebo group, they might have different effects in the 400 mg group) on the various outcome parameters. When the dosage main effect was statistically significant, post hoc testing with Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (Tukey’s HSD) adjustment was performed on pairwise comparisons of interest (0–200, 0–400, 200–400). Student’s t-test, or the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate, was used to evaluate for an effect of active drug (200 mg or 400 mg) compared to placebo for DMAU and 11β-MNTDC. The residuals were checked to ensure they followed a normal distribution. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of extreme values, defined as over 2 interquartile ranges (IQR) below the first quartile or above the third quartile. Both unadjusted and adjusted modeling was performed; covariates used were 1) weight at baseline and 2) change in weight from baseline to day 28. The association of dietary fat adherence with trough DMA and DMAU concentrations and changes in weight and LDL-C were assessed via Wilcoxon rank sum test.

All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Participant Demographics

A total of 78 men (38 DMAU, 40 11β-MNTDC) were included in the analyses, based upon participation in the selected dose groups and consent for long term storage of their samples for future research (Figs. 1A & 1B). In the DMAU study, one subject did not have glucose and lipid profile data on Day 28 and he was excluded from those analyses. The baseline demographics of participants in the two studies were not significantly different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics of All Treated Participants

| 11β-MNTDC | DMAU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=11) | 200mg (n=15) | 400mg (n=16) | Placebo (n=11) | 200mg (n=15) | 400mg (n=15) | |

| Age (year) | 25 (21, 33) | 33 (26, 36) | 27 (22, 36) | 35 (29, 40) | 29 (25, 36) | 30 (25, 37) |

| Weight (kg) | 74.0 (66.6, 87.5) | 86.8 (75.8, 92.8) | 77.5 (67.4, 86.6) | 76.8 (66.6, 86.6) | 81.5 (76.7, 95.7) | 74.5 (67.5, 80.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.2 (21.1, 26.5) | 25.6 (23.8, 29.3) | 25.5 (24.2, 27.8) | 24.0 (22.5, 27.0) | 26.0 (24.0, 29.5) | 24.0 (22.0, 27.0) |

| Serum T (ng/dL) | 445 (369, 557) | 457 (395, 570) | 532 (434, 600) | 527 (446, 595) | 575 (448, 717) | 534 (497, 656) |

| Sperm concentration (million/mL) | 71.4 (41.0, 133.8) | 47.3 (32.9, 59.0) | 50.5 (29.4, 136.1) | 67.8 (44.6, 123.6) | 40.5 (28.2, 63.0) | 62.9 (37.7, 123.0) |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 7 |

| Black | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Asian | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 8 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 15 |

Numerical data reported as median (25th, 75th inter-quartile range)

Adherence to the dietary fat requirement was high; 89% of the participants were adherent to the recommended diet for at least 90% of the 28 days. Adherence to dietary fat requirement was not associated with trough concentrations of DMAU or DMA, nor changes in weight or changes in LDL.

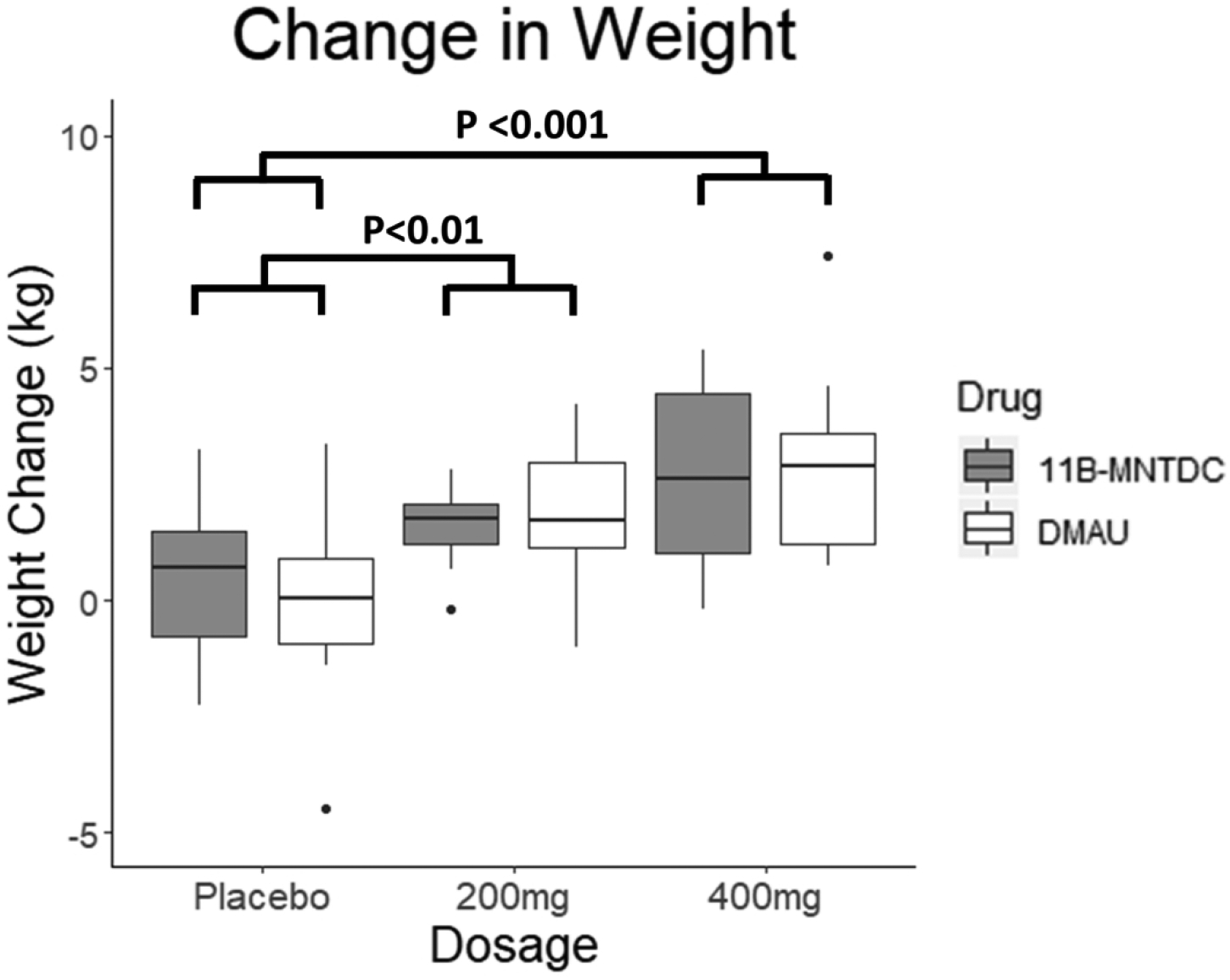

Weight: Increased

There was a significant increase in weight with dosage group when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed linear regression model analyses (p<0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 2). There were no significant effects of androgen type (p=0.82) or dosage-drug interaction (p=0.79) (Table 2). Post hoc testing showed that the differences were between the placebo and 200 mg groups (p<0.01), as well as the placebo and 400 mg groups (p<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between the 200 mg and 400 mg groups (p=0.06). Adjusting for baseline weight and for weight change did not affect any of the conclusions for all metabolic parameters (Tables 4 & 5). There was also a significant increase in weight in the analyses comparing active drug [200 mg, 400 mg] against placebo for DMAU (p<0.01) and for 11β-MTDC (p<0.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mixed Model Analyses: Changes in Parameters from Day 1 to Day 28

| Placebo | 200mg | 400mg | P Values | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11β-MNTDC (n=10) | DMAU (n=11) | 11β-MNTDC (n=15) | DMAU (n=14) | P value vs Placebo | 11β-MNTDC (n=15) | DMAU (n=13) | P value vs Placebo | P value vs 200mg | Overall Effect of Dosage Group | Effect of Androgen Type | Dosage × Drug Interaction | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.7 (−0.8, 1.5) | 0.1 (−0.9, 0.9) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.1) | 1.7 (1.1, 3.0) | 0.005** | 2.6 (1.0, 4.5) | 2.9 (1.2, 3.6) | <0.001*** | 0.06 | <0.001*** | 0.82 | 0.79 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) # | 2.0 (−1.5, 3.0) | 1.0 (−4.0, 5.0) | −1.0 (−5.0, 4.5) | −6.0 (−7.0, 2.0) | NS | 0 (−8.0, 3) | −7.0 (−10.0, −1.0) | NS | NS | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.69 |

| Fasting Insulin (mIU/L) # | 1.2 (0.0, 4.0) | −0.1 (−1.0, 1.8) | −0.7 (−2.0, 1.9) | −1.8 (−3.1, 0.1) | NS | −1.1 (−2.7, 2.3) | −0.9 (−2.6, −0.2) | NS | NS | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.88 |

| HOMA-IR # | 0.2 (0.1, 1.0) | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.4) | −0.0 (−0.5, 0.4) | −0.4 (−0.8, 0.07) | NS | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.6) | −0.3 (−0.5, −0.1) | NS | NS | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.90 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) # | −1.5 (−1.7, −0.9) | 1.4 (−0.4, 1.9) | −0.4 (−1.9, 0.2) | −1.8 (−3.0, −1.3) | NS | −1.4 (−1.9, 0.1) | −1.3 (−3.6, 0.1) | NS | NS | 0.28 | 0.94 | 0.06 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 1.0 (−5.3, 4.5) | 0.0 (−1.0, 5.5) | −11.0 (−15.0, −8.0) | −13.0 (−19.0, −8.0) | <0.001*** | −16.0 (−23.0, −10.0) | −11.0 (−15.0, −7.0) | <0.001*** | 0.96 | <0.001*** | 0.40 | 0.22 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | −10.5 (−20.8, −5.0) | 2.0 (−4.5, 8.5) | 11.0 (2.5, 22.0) | 4.0 (−2.0, 10.0) | 0.12 | 20.0 (13.0, 31.5) | 8.0 (0.0, 46.0) | <0.001*** | 0.09 | <0.001*** | 0.98 | 0.24 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) # | 7.5 (−9.8, 24.3) | −9.0 (−12.0, 9.0) | −10.0 (−17.0, −6.0) | 8.0 (−33.0, 15.0) | NS | −1.0 (−12.0, 24.0) | −6.0 (−23.0, 4.0) | NS | NS | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.99 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) # | −10.0 (−15.0, −1.0) | −1.0 (−8.0, 23.0) | 2.0 (−9.0, 8.5) | −12.0 (−22.0, 6.0) | NS | 13.0 (−6.0, 23.5) | 2.0 (−20.0, 33.0) | NS | NS | 0.13 | 0.93 | 0.22 |

| Hematocrit (%) | −2.1 (−4.5, 0.8) | 0.0 (−1.6, 0.7) | 1.0 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.0 (−0.5, 1.8) | <0.001*** | 1.0 (−0.5, 1.5) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | <0.001*** | 0.98 | <0.001*** | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | −1.0 (−6.5, 2.8) | −1.4 (−6.3, 3.7) | −21.2 (−26.9, −8.9) | −16.4 (−23.9, −14.8) | <0.001*** | −23.4 (−29.8, −11.8) | −16.8 (−24.9, −10.1) | <0.001*** | 0.93 | <0.001*** | 0.77 | 0.48 |

Median (25th, 75th percentiles). Participants missing Day 28 data were excluded from the individual analyses. Fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, and adiponectin were assessed in a subset of participants as follows: Placebo, 11β-MNTDC (n=8), DMAU (n=11); 200 mg, 11β-MNTDC (n=12), DMAU (n=14); 400 mg, 11β-MNTDC (n=11), DMAU (n=13)

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001;

NS = non-significant

Post-hoc testing to assess for differences between the individual dosage groups was only performed if the overall p value for dosage group was p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Changes in weight from Day 1 to Day 28. There was a significant dosage group effect seen (p<0.001). Post-hoc testing showed the differences were between the placebo and treatment arms. There was no significant effect of androgen type or dosage-drug interaction. (For this and subsequent figures: The median is displayed; the hinges of the box are the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers display the smallest and largest values at most 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) of the hinge. Values more than 1.5 IQR are shown as specific points in the graph.)

Table 4.

Mixed Model Analyses – P Values Adjusted for Baseline Weight

| Placebo vs 200mg | Placebo vs 400mg | 200mg vs 400mg | Overall Effect of Dosage Group | Effect of Androgen Type | Drug-Dosage Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 0.012* | <0.001*** | 0.049* | <0.001*** | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.73 |

| Fasting Insulin (mIU/mL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.90 |

| HOMA-IR # | NS | NS | NS | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.92 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.06 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | 0.92 | <0.001*** | 0.40 | 0.21 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 0.20 | <0.001*** | 0.06 | <0.001*** | 0.99 | 0.26 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.23 | 0.17 | 1.00 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.26 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 0.002** | <0.001*** | 0.92 | <0.001*** | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | 0.99 | <0.001*** | 0.79 | 0.44 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001;

NS = non-significant

Post-hoc testing to assess for differences between the individual dosage groups was only performed if the overall p value for dosage group was < 0.05.

Table 5.

Mixed Model Analyses – Adjusted for Change in Weight

| Placebo vs 200mg | Placebo vs 400mg | 200mg vs 400mg | Overall Effect of Dosage Group | Effect of Androgen Type | Drug-Dosage Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.65 |

| Fasting Insulin (mIU/mL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.89 |

| HOMA-IR # | NS | NS | NS | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.90 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.59 | 0.95 | 0.07 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | <0.001*** | 0.003** | 0.79 | <0.001*** | 0.44 | 0.18 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 0.053 | <0.001*** | 0.046* | <0.001*** | 0.98 | 0.27 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) # | NS | NS | NS | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.99 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.88 | 0.03^ | 0.03^ | 0.02^ | 0.86 | 0.27 |

| Hematocrit (%) | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | 0.88 | <0.001*** | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | <0.001*** | <0.001*** | 0.83 | <0.001*** | 0.82 | 0.28 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001;

NS = non-significant

Post-hoc testing to assess for differences between the individual dosage groups was only performed if the overall p value for dosage group was < 0.05.

With removal of extreme values (sensitivity analysis), results are no longer significant (overall effect of dosage group p=0.05)

Table 3.

Median Changes in Parameters from Day 1 to Day 28 – Comparing Active Drug and Placebo

| 11β-MNTDC | DMAU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n) | Active (n) | P Value | Placebo (n) | Active (n) | P Value | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.7 (10) | 1.9 (30) | 0.02* | 0.1 (11) | 2.1 (27) | 0.005** |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 2.0 (10) | −0.5 (30) | 0.46 | 1.0 (11) | −6.5 (26) | 0.13 |

| Fasting Insulin (mIU/L) $ | 1.2 (7) | −1.1 (23) | 0.12 | −0.1 (11) | −1.3 (27) | 0.19 |

| HOMA-IR $ | 0.2 (7) | 0.0 (23) | 0.15 | −0.1 (11) | −0.3 (26) | 0.14 |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) $ | −1.5 (8) | −0.4 (23) | 0.62 | 1.4 (11) | −1.7 (26) | 0.006** |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 1.0 (10) | −12.0 (30) | <0.001*** | 0.0 (11) | −11.0 (26) | <0.001*** |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | −10.5 (10) | 16.0 (30) | <0.001*** | 2.0 (11) | 5.0 (26) | 0.07 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) $ | 7.5 (10) | −10.0 (30) | 0.26 | −9.0 (11) | −4.0 (26) | 0.43 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) $ | −10.0 (10) | 4.5 (30) | 0.03^* | −1.0 (11) | −5.0 (26) | 0.31 |

| Hematocrit (%) | −2.1 (10) | 1.0 (30) | 0.011* | 0.0 (11) | 1.0 (27) | 0.04* |

| SHBG (nmol/L) $ | −1.0 (10) | −22.3 (30) | <0.001*** | −1.4 (11) | −16.6 (27) | <0.001*** |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001; NS = non-significant

With removal of extreme values (sensitivity analysis), results are no longer significant (p=0.06).

The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

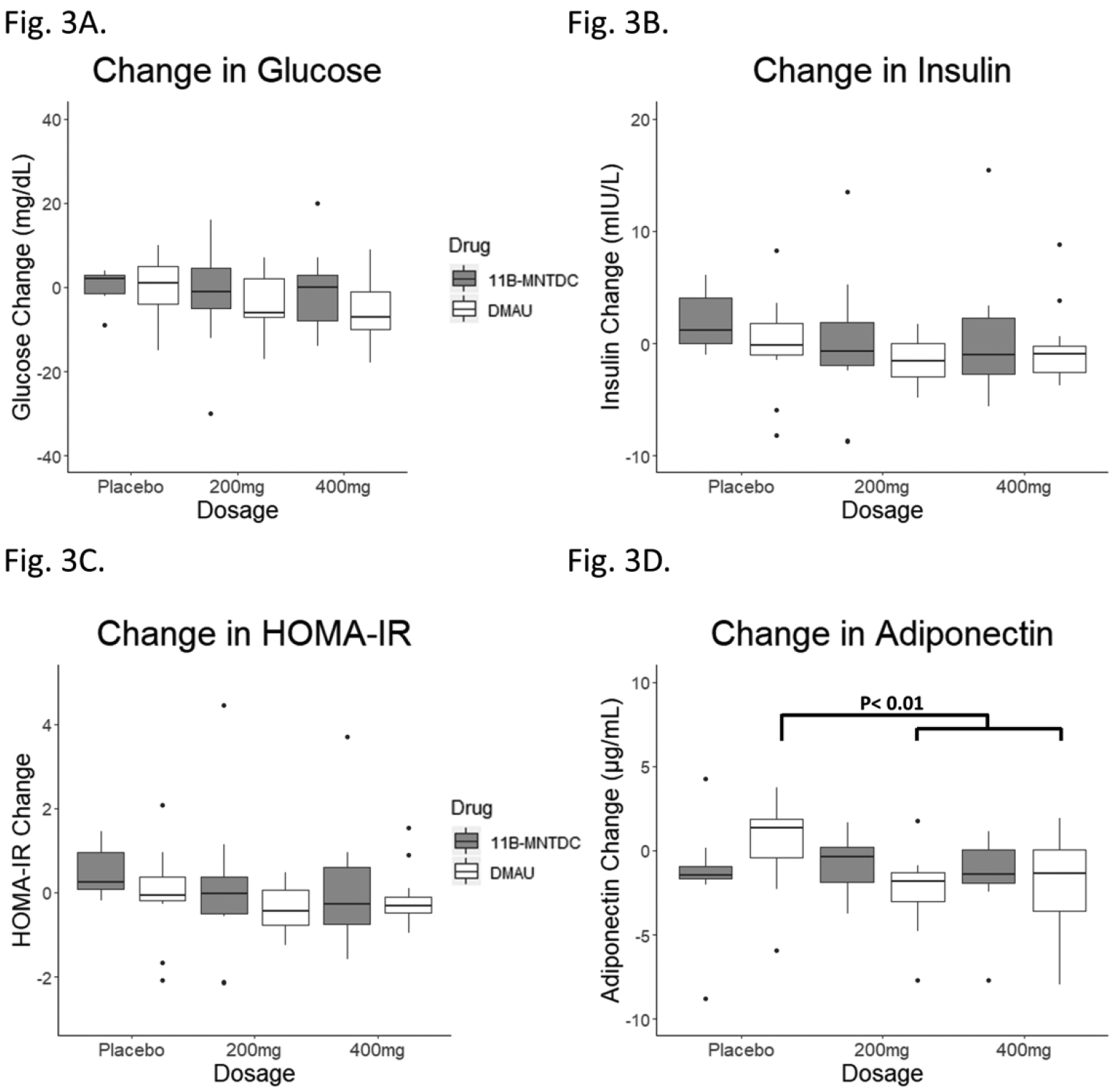

Insulin Resistance: No Change

Fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and HOMA-IR did not change with administration of either drug compared to placebo, by mixed model analyses (Table 2, Fig. 3). For all three parameters, there were no significant effects of dosage, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. Sensitivity analyses with removal of extreme values did not affect the results. There were also no significant differences between active DMAU and placebo, nor active 11β-MNTDC and placebo (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Changes in metabolic parameters from Day 1 to to Day 28. (A) Fasting glucose: There was no significant effect of dosage group, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. (B) Fasting insulin: Two participants with biologically implausible insulin levels were excluded. There was no significant effect of dosage group, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. (C) Fasting insulin resistance as calculated by HOMA-IR. Two participants with biologically implausible insulin levels were excluded. There was no significant effect of dosage group, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. (D) Adiponectin: There was no significant effect of dosage group, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. There was a decrease in adiponectin in participants receiving DMAU active drug compared to placebo (p<0.01) but there was no significant change in adiponectin in participants receiving 11β-MNTDC active drug compared to placebo.

Adiponectin: Decreased with DMAU But Not 11β-MNTDC

There was no significant difference in changes in adiponectin with dosage group when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed model analyses (p=0.28). The difference between androgens was not significant (p=0.94); this term compares all participants who were in the DMAU study against all participants who were in the 11β-MNTDC study, including participants on placebo. Nor was there a significant dosage-drug interaction (p=0.06), even after adjusting for weight change (Table 2; Fig. 3). Presence of a dosage-drug interaction would suggest that the two drugs affect adiponectin to different degrees (i.e. a decrease in adiponectin as dosage increases). However, in the analyses of active drug versus placebo, there was a statistically significant decrease in adiponectin levels in the DMAU active treatment group compared to placebo (placebo, 1.4 μg/mL; active treatment, −1.7 μg/mL; p < 0.01) but not with 11β-MNTDC (placebo, −1.5 μg/mL; active treatment, −0.4 μg/mL; p = 0.62) (Table 3). The placebo group in the 11β-MNTDC study had a median decrease in adiponectin which was not seen in the DMAU placebo group, but the decrease in adiponectin in the DMAU active treatment group was also slightly greater than that in the 11β-MNTDC active treatment group, despite similar increases in weight (Table 3).

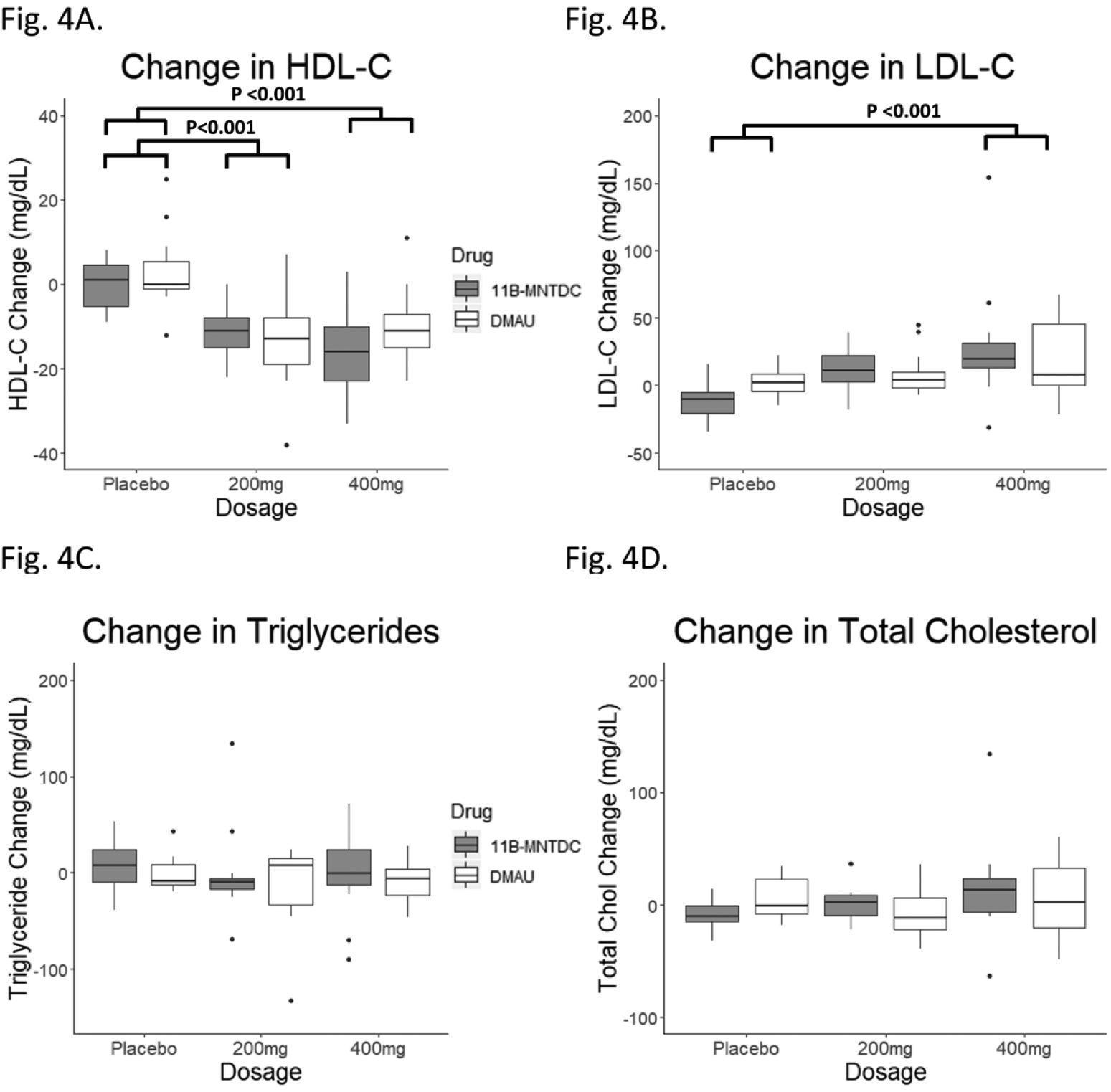

HDL-C: Decreased

There was a significant decrease in HDL-C with dosage group when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed model analyses (p<0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 4). There were no significant effects of androgen type (p=0.40) or dosage-drug interaction (p=0.22). Post hoc testing showed that the differences were between the placebo and 200 mg groups, as well as the placebo and 400 mg groups (p<0.001 for both). There was no statistically significant difference between the 200 mg and 400 mg groups (p=0.96). Sensitivity analyses with removal of extreme values did not affect the results. The decrease in HDL-C was also significant in active DMAU compared to placebo, and active 11β-MNTDC compared to placebo (p<0.001 for both) (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Changes in lipids from Day 1 to Day 28. (A) HDL-Cholesterol: There was a significant dosage group effect seen (p<0.001). Post-hoc testing showed the differences were between the placebo and treatment arms. There was no significant effect of androgen type or dosage-drug interaction. (B) LDL-Cholesterol: There was a significant dosage group effect seen (p<0.001). Post-hoc testing showed the differences were between the placebo and treatment arms. There was no significant effect of drug androgen type or dosage-drug interaction. (C) Triglyceride: There was no significant effect of dosage group, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. (D) Total cholesterol: There was no significant effect of dosage group, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction.

LDL-C: Increase More Pronounced with 11β-MNTDC Than DMAU

There was a significant increase in LDL-C with dosage group when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed model analyses (p<0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 4). There were no significant effects of androgen type (p=0.98) or dosage-drug interaction (p=0.24). Post hoc testing showed that the differences were between the placebo and 400 mg group only (p<0.001); there was no significant difference between the placebo and 200 mg group (p=0.12) nor the 200 mg and 400 mg groups (p=0.09). While most participants had changes in LDL-C of less than 50 mg/dL, one participant receiving 11β-MNTDC 400 mg had an increase in LDL-C of 150 mg/dL. Sensitivity analyses with removal of extreme values did not affect the results (p<0.001 dosage group effect). Analyses of active drug compared to placebo demonstrated a significant increase in LDL-C with 11β-MNTDC (p<0.001) but was not statistically significant with DMAU (p=0.07) (Table 3).

Triglycerides: No Change

Triglycerides did not change with administration of either drug compared to placebo, when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed model analyses (Table 2, Fig. 4). There were no significant effects of dosage, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. Sensitivity analyses with removal of extreme values did not affect the results. There were also no significant differences between active DMAU and placebo, nor active 11β-MNTDC and placebo (Table 3).

Total Cholesterol: No Change Overall

There was no statistically significant change in total cholesterol when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed model analyses (Table 2, Fig. 4). There were no significant effects of dosage, androgen type, or dosage-drug interaction. In the analyses of active drug compared to placebo, there was no change in total cholesterol with DMAU (p=0.31), but there was a statistically significant increase in total cholesterol with 11β-MNTDC (p<0.05); this effect disappeared after removal of extreme values in the sensitivity analysis (p=0.06) (Table 3).

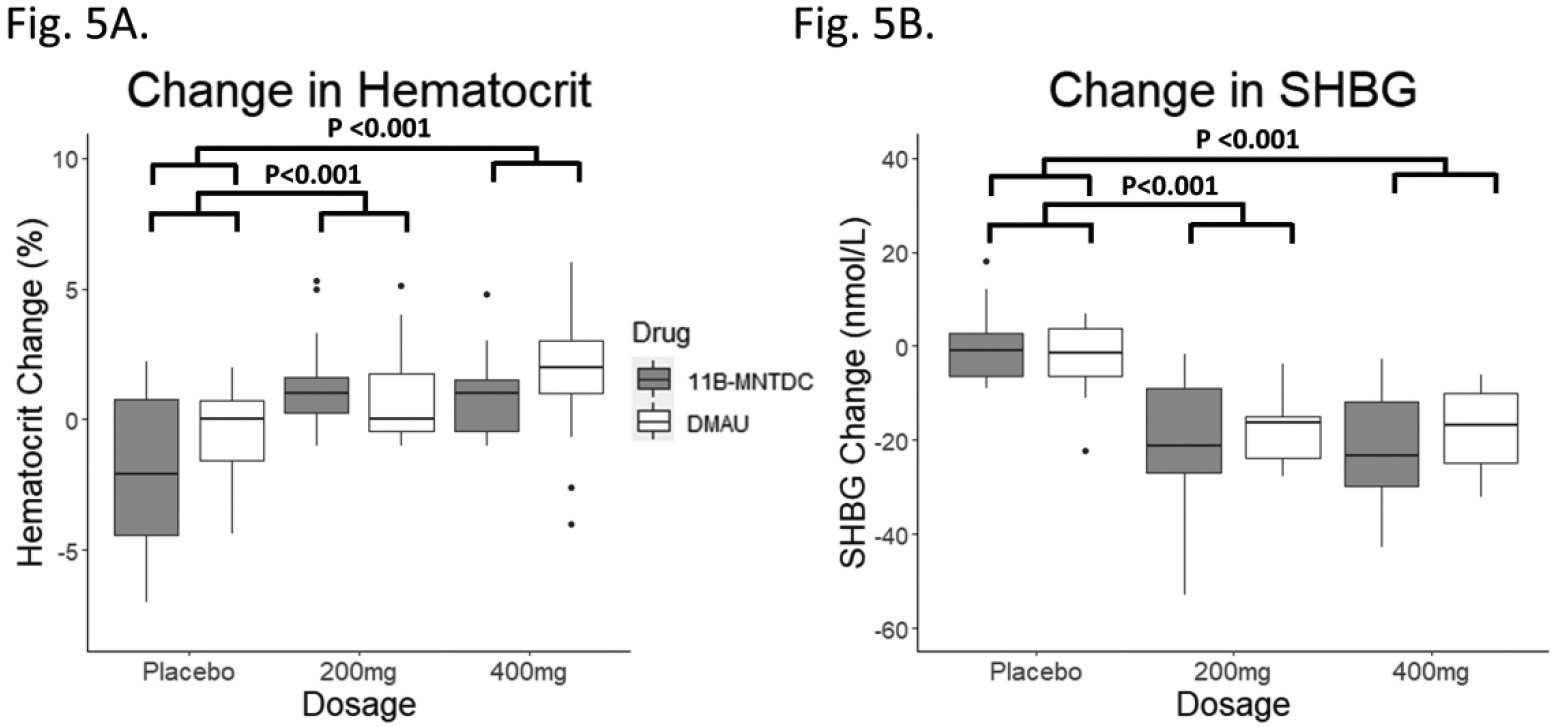

Hematocrit: Increased

There was a significant increase in hematocrit with dosage group when the compounds were analyzed by mixed model analyses (p<0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 5). Post hoc testing showed that the differences were between the placebo and 200 mg groups (p<0.001) as well as the placebo and 400 mg groups (p<0.001). There was no significant difference between the 200 mg and 400 mg groups (p=0.98). There were no significant effects of androgen type (p=0.31) or dosage-drug interaction (p=0.28). The increase in hematocrit was also significant in active DMAU compared to placebo, and active 11β-MNTDC compared to placebo (p<0.05 for both) (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Changes in parameters affected by androgens from Day 1 to Day 28. (A) Hematocrit: There was a significant dosage group effect seen (p<0.001). Post-hoc testing showed the differences were between the placebo and treatment arms. There was no significant effect of androgen type or dosage-drug interaction. (B) Sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG): There was a significant dosage group effect seen (p<0.001). Post-hoc testing showed the differences were between the placebo and treatment arms. There was no significant effect of androgen type or dosage-drug interaction.

Sex Hormone Binding Globulin: Decreased

There was a significant decrease in SHBG with dosage group (p<0.001) when the two drugs were analyzed by mixed model analyses (Table 2, Fig. 5). Post hoc testing showed that the differences were between the placebo and 200 mg groups (p<0.001) as well as the placebo and 400 mg groups (p<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between the 200 mg and 400 mg groups (p=0.93). There were no significant effects of androgen type or dosage-drug interaction. Neither adjusting for weight at baseline nor adjusting for weight change affected the results (Tables 4 & 5). The decrease in SHBG was also significant in active DMAU compared to placebo, and active 11β-MNTDC compared to placebo (p<0.001 for both) (Table 3).

Effect of Weight Change and Baseline Weight on Metabolic parameters

Adjusting for baseline weight and weight change did not affect the conclusions for any of the metabolic parameters (Tables 4 & 5). After adjusting for baseline weight, there was now a statistically significant difference between the change in weight in the 200 mg and 400 mg groups (p=0.049) (Table 4). After adjusting for weight change, the increase in total cholesterol was statistically significant (p=0.03), with post hoc testing showing the difference was between the placebo and 400 mg groups; this effect again disappeared after removal of extreme values in the sensitivity analysis (p=0.05) (Table 5). Of note, adjusting for weight change did not affect the results of the adiponectin analyses; the decrease in adiponectin in the DMAU active group compared to placebo remained statistically significant (p=0.03) and there was again no significant change in adiponectin in the 11β-MNTDC active group compared to placebo (p=0.49).

Discussion

Young adult men may choose to use a male hormonal contraceptive for prolonged periods of time to prevent pregnancy; thus, small changes in important metabolic surrogates over an extended period of time may be clinically meaningful but may not become apparent until much later in life. Such therapy is likely to comprise of a combination of androgenic and progestational agents since the combination is more effective than androgens alone in suppressing gonadotropins (LH and FSH) and sperm counts. An alternate approach is to examine single compounds with both androgenic and progestational properties. Though studies suggest that these androgen-progestin regimens are relatively safe in the short term (<3 years) [7], the potential metabolic effects over longer periods are relatively unknown.

We present data comparing the effects of DMAU and 11β-MNTDC on insulin, insulin resistance, and adiponectin in men. In addition, this is the first comparison in men of the effects of DMAU and 11β-MNTDC on several metabolic endpoints, through this combined analysis.

Analysis of the metabolic effects of these two compounds in our subset of participants agreed with previously published results [28, 29]. The combined analyses did not show significant differences between these two progestational androgens. Both drugs increased body weight compared to placebo, with a median weight increase of 3 kg in the 400 mg groups. Weight gain could be secondary to increases in muscle mass, fat mass, or sodium and water retention [33, 34]. In hypogonadal men, testosterone therapy increases lean body mass and decreases fat mass [35]. Sex hormones are known to have effects on fluid retention, possibly via the reninangiotensin system [36]. In prior studies on male hormonal contraception, weight gain of approximately 3–5 kg is a commonly noted finding [1, 2, 4, 6]. The etiology of weight gain remains to be clarified in future studies, i.e. ones including body composition measurements.

There was no change detected in fasting insulin, fasting glucose, or HOMA-IR despite an increase in weight. As progestins have been shown to worsen insulin sensitivity in some studies [16], and as insulin resistance has been linked with the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, it is reassuring that, in these relatively short studies in healthy men with normal BMI, there was no change detected in insulin resistance.

Adiponectin did not decrease with dosage group in the mixed model analyses of the two drugs, nor was there a significant difference between the two drugs (p = 0.06 for dosage-drug interaction). In the analyses of participants on active drug compared to placebo, adiponectin decreased with DMAU but not with 11β-MNTDC. All changes in adiponectin were small; prior studies of adiponectin have found fluctuations of similar magnitudes in lean healthy men as well as elderly men in the placebo group [23, 37]. Testosterone administration decreases adiponectin levels by suppressing its secretion from adipose cells [23, 24, 38]. Meta-analyses of multiple studies have shown that elevated adiponectin levels are associated with increased mortality [21, 22]; thus the contribution of adiponectin to overall health, and the long-term effects of decreasing adiponectin, remains unclear. Subtle differences in the effects of DMAU and 11β-MNTDC may be due to differences in androgenicity [39]. Despite the slight decrease in adiponectin, there were no changes in insulin levels or insulin resistance. Given the short duration of the study (28 days) and the modest number of participants, future studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions about the effects of either androgen on adiponectin.

There was a clear decrease in HDL-C seen with oral administration of both androgens, with a median decrease in HDL-C of −28% in the 400 mg groups. There was also a 23% increase in LDL-C in the combined 400 mg groups (13% in the DMAU 400 mg group, 25% in 11β-MNTDC 400 mg group). The increase in LDL-C in the DMAU active drug group compared to placebo was not significant but was significant in the 11β-MNTDC active drug group. Androgen administration is known to decrease HDL-C; oral androgen administration appears to lead to greater decreases in HDL-C (~20–30%) [40, 41] compared to transdermal androgen administration (~10%) [42, 43]. Prior male contraception studies using testosterone-progestin combinations reported this decrease in HDL-C but did not observe any increase in LDL-C [17, 44]. Most trials in eugonadal and hypogonadal men show no significant change or a decrease in LDL-C with parenteral or transdermal testosterone [45–49]. Several, but not all, studies of oral androgens suggest that LDL-C may increase with oral administration [41, 50, 51]. Oral androgens undergo first-pass metabolism in the liver and thus may affect hepatic lipases more strongly. Also, DMA and 11β-MNT are not aromatized; estrogenic compounds increase HDL-C and decrease LDL-C [27, 50]. Both compounds have progestational activity, and progestins also affect HDL-C and LDL-C [52]. It is unclear what the long term consequences of changes in HDL-C would be, especially as recent studies have shown it is HDL functionality which improves cardiovascular risk, rather than HDL-C total levels [53, 54]. High LDL-C is a well-recognized risk for future cardiovascular disease [55], so increases in this metric need to be monitored closely in longer-term studies.

The metabolic effects of these two novel androgens in men appears to be a class effect and includes decreased HDL-C and SHBG and increase in hematocrit and weight; many of these effects are known to occur with androgen administration. A strength of the current analyses is that the study design is similar in the two studies and many of the key endpoints were measured in the same laboratory. This secondary analysis is limited by the fact that these studies were Phase 1 studies involving small numbers of participants for a limited exposure time of 28 days. The original sample sizes were chosen to detect safety abnormalities in 20% of men, and these studies were not powered to detect small changes in these metabolic outcomes. All of the reported analyses are exploratory and are intended to direct future research. Although it is not possible to exclude the presence of a small difference between the two compounds, this study excludes large differences. Participants received the study agent for 28 days; the effects of longer-term administration will need to be evaluated in future studies.

Conclusion

This study reports an analysis of serum samples from 28-day studies of two novel oral androgenic compounds with progestational activities and compares the effects of the two compounds on a number of metabolic markers and parameters traditionally affected by androgens. Class effects include increase in weight and hemoglobin, and decrease in HDL-C and SHBG. There were no significant changes in insulin resistance after 28 days of oral administration of these novel androgens despite the mild increase in weight. There may be subtle differences in their metabolic impacts (i.e. LDL-C, adiponectin) that should be explored in future studies, including studies of longer duration, and studies in men who are less metabolically healthy at baseline. Selection of products will ultimately depend on the ideal combination of efficacy, optimal dosage and minimal potential adverse effects to assure acceptable safety to users.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Min S. Lee, PhD in the Contraceptive Development Program, NICHD and Toufan Parman, PhD, Jia-Hwa Fang, PhD, and Jennie Wang, PhD at Stanford Research Institute International for manufacture of DMAU, 11β-MNTDC, and placebo capsules. We thank our research coordinators, Xiao-Dan Han, Elizabeth Ruiz, Isabel Payan, Michael Massone, Kathy Winter, and Kathryn Torrez-Duncan, for their assistance with the study. We thank the staff of the Endocrine and Metabolic Research Laboratory at The Lundquist Institute and the University of Washington Center for Research in Reproduction and Contraception, and most importantly we thank our research participants.

Funding Information

The study was conducted in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Contraceptive Clinical Trials Network under contracts with The Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (formerly LA BioMed) (HHSN27520130024I, Task Order HHSN27500006 and HHSN2800004), University of Washington (HHSN275201300025I, Task Order HHSN27500005) and Health Decisions (HHSN2752012002). FY is supported by NICHD F32 HD097932. PYL is supported in part by NHLBI K24 HL138632. STP is supported in part by the Robert McMillen Professorship in Lipid Research. The Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and University of Washington receive support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences for Clinical and Translational Science Institutes (UL1TR0001881, UL1TR000423). Assays were performed using a voucher UCLA CTSI Grant UL1TR0001881.

Disclosures

FY, AT, FAF, PYL, L Hull, RB, and STP have no disclosures. RSS is a consultant for Clarus Therapeutics and RSS received research support from: Clarus Therapeutics; TRT Manufacturers Consortium; and Chugai Pharmaceuticals. CW receives research support from TesoRX and Clarus Therapeutics. JEL and DLB are employees of the US Government.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Western Medical Regional Conference (WMRC) 2020, Carmel, CA and the 102nd Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society (ENDO) 2020, San Francisco, CA

Clinical Trial Number: NCT01382069 and NCT02754687

References

- 1.World Health Organization Task Force on the Regulation of Male Fertility. Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in normal men. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(4):821–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu YQ, Wang XH, Xu D, Peng L, Cheng LF, Huang MK, Huang ZJ, Zhang GY. A multicenter contraceptive efficacy study of injectable testosterone undecanoate in healthy Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(2):562–8. Epub 2003/02/08. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Handelsman DJ, Conway AJ, Howe CJ, Turner L, Mackey MA. Establishing the minimum effective dose and additive effects of depot progestin in suppression of human spermatogenesis by a testosterone depot. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(11):4113–21. Epub 1996/11/01. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebb RA, Anawalt BD, Christensen RB, Paulsen CA, Bremner WJ, Matsumoto AM. Combined administration of levonorgestrel and testosterone induces more rapid and effective suppression of spermatogenesis than testosterone alone: a promising male contraceptive approach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(2):757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Christenson PD, Handelsman DJ, Wang C. Rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. Lancet. 2006;367(9520):1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner L, Conway AJ, Jimenez M, Liu PY, Forbes E, McLachlan RI, Handelsman DJ. Contraceptive efficacy of a depot progestin and androgen combination in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(10):4659–67. Epub 2003/10/15. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zitzmann M Would male hormonal contraceptives affect cardiovascular risk? Asian J Androl. 2018;20(2):145–8. Epub 2018/02/01. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_2_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Chávez A, Chávez-Fernández JA, Elizondo-Argueta S, González-Tapia A, León-Pedroza JI, Ochoa C. Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease: A Health Challenge. Arch Med Res. 2018;49(8):516–21. Epub 2018/12/12. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tune JD, Goodwill AG, Sassoon DJ, Mather KJ. Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl Res. 2017;183:57–70. Epub 2017/01/29. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapoor D, Goodwin E, Channer KS, Jones TH. Testosterone replacement therapy improves insulin resistance, glycaemic control, visceral adiposity and hypercholesterolaemia in hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154(6):899–906. Epub 2006/05/27. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naharci MI, Pinar M, Bolu E, Olgun A. Effect of testosterone on insulin sensitivity in men with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(6):629–35. Epub 2007/10/24. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corona G, Torres LO, Maggi M. Testosterone Therapy: What We Have Learned From Trials. The journal of sexual medicine. 2020;17(3):447–60. Epub 2020/01/14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.11.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monroe AK, Dobs AS. The effect of androgens on lipids. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(2):132–9. Epub 2013/02/21. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835edb71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thirumalai A, Rubinow KB, Page ST. An update on testosterone, HDL and cardiovascular risk in men. Clin Lipidol. 2015;10(3):251–8. Epub 2015/08/11. doi: 10.2217/clp.15.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zgliczynski S, Ossowski M, Slowinska-Srzednicka J, Brzezinska A, Zgliczynski W, Soszynski P, Chotkowska E, Srzednicki M, Sadowski Z. Effect of testosterone replacement therapy on lipids and lipoproteins in hypogonadal and elderly men. Atherosclerosis. 1996;121(1):35–43. Epub 1996/03/01. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zitzmann M, Rohayem J, Raidt J, Kliesch S, Kumar N, Sitruk-Ware R, Nieschlag E. Impact of various progestins with or without transdermal testosterone on gonadotropin levels for non-invasive hormonal male contraception: a randomized clinical trial. Andrology. 2017;5(3):516–26. Epub 2017/02/12. doi: 10.1111/andr.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anawalt BD, Amory JK, Herbst KL, Coviello AD, Page ST, Bremner WJ, Matsumoto AM. Intramuscular testosterone enanthate plus very low dosage oral levonorgestrel suppresses spermatogenesis without causing weight gain in normal young men: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Andrology. 2005;26(3):405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohashi K, Ouchi N, Matsuzawa Y. Anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic properties of adiponectin. Biochimie. 2012;94(10):2137–42. Epub 2012/06/21. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(3):439–51. Epub 2005/05/18. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigro E, Scudiero O, Monaco ML, Palmieri A, Mazzarella G, Costagliola C, Bianco A, Daniele A. New insight into adiponectin role in obesity and obesity-related diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:658913. Epub 2014/08/12. doi: 10.1155/2014/658913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menzaghi C, Trischitta V. The Adiponectin Paradox for All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality. Diabetes. 2018;67(1):12–22. Epub 2017/12/22. doi: 10.2337/dbi17-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sook Lee E, Park SS, Kim E, Sook Yoon Y, Ahn HY, Park CY, Ho Yun Y, Woo Oh S. Association between adiponectin levels and coronary heart disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1029–39. Epub 2013/06/07. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page ST, Herbst KL, Amory JK, Coviello AD, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ. Testosterone administration suppresses adiponectin levels in men. J Androl. 2005;26(1):85–92. Epub 2004/12/22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu A, Chan KW, Hoo RL, Wang Y, Tan KC, Zhang J, Chen B, Lam MC, Tse C, Cooper GJ, Lam KS. Testosterone selectively reduces the high molecular weight form of adiponectin by inhibiting its secretion from adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(18):18073–80. Epub 2005/03/12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attardi BJ, Hild SA, Reel JR. Dimethandrolone undecanoate: a new potent orally active androgen with progestational activity. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6):3016–26. Epub 2006/02/25. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu S, Yuen F, Swerdloff RS, Pak Y, Thirumalai A, Liu PY, Amory JK, Bai F, Hull L, Blithe DL, Anawalt BD, Parman T, Kim K, Lee MS, Bremner WJ, Page ST, Wang C. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Single-Dose Novel Oral Androgen 11beta-Methyl-19-Nortestosterone-17beta-Dodecylcarbonate in Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(3):629–38. Epub 2018/09/27. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Attardi BJ, Pham TC, Radler LC, Burgenson J, Hild SA, Reel JR. Dimethandrolone (7alpha,11beta-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone) and 11beta-methyl-19-nortestosterone are not converted to aromatic A-ring products in the presence of recombinant human aromatase. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2008;110(3–5):214–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thirumalai A, Ceponis J, Amory JK, Swerdloff R, Surampudi V, Liu PY, Bremner WJ, Harvey E, Blithe DL, Lee MS, Hull L, Wang C, Page ST. Effects of 28 Days of Oral Dimethandrolone Undecanoate in Healthy Men: A Prototype Male Pill. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(2):423–32. Epub 2018/09/27. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuen F, Thirumalai A, Pham C, Swerdloff RS, Anawalt BD, Liu PY, Amory JK, Bremner WJ, Dart C, Wu H, Hull L, Blithe DL, Long J, Wang C, Page ST. Daily Oral Administration of the Novel Androgen 11beta-MNTDC Markedly Suppresses Serum Gonadotropins in Healthy Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3). Epub 2020/01/25. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuen F, Thirumalai A, Swerdloff RS, Liu PY, Pak Y, Hull L, Blithe DL, Long J, Page ST, Wang C. Short term Metabolic Effects of Two Novel Oral Androgens, Dimethandrolone Undecanoate and 11β-MNTDC - Supplemental File. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13489203.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson JL, Duick DS, Chui MA, Aldasouqi SA. Identifying prediabetes using fasting insulin levels. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(1):47–52. Epub 2009/10/01. doi: 10.4158/EP09031.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–9. Epub 1985/07/01. doi: 10.1007/bf00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhasin S, Taylor WE, Singh R, Artaza J, Sinha-Hikim I, Jasuja R, Choi H, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. The mechanisms of androgen effects on body composition: mesenchymal pluripotent cell as the target of androgen action. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(12):M1103–10. Epub 2003/12/20. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.12.m1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johannsson G, Gibney J, Wolthers T, Leung KC, Ho KK. Independent and combined effects of testosterone and growth hormone on extracellular water in hypopituitary men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):3989–94. Epub 2005/04/14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Traish AM, Haider A, Doros G, Saad F. Long-term testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men ameliorates elements of the metabolic syndrome: an observational, long-term registry study. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(3):314–29. Epub 2013/10/17. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed AH, Gordon RD, Taylor PJ, Ward G, Pimenta E, Stowasser M. Effect of contraceptives on aldosterone/renin ratio may vary according to the components of contraceptive, renin assay method, and possibly route of administration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(6):1797–804. Epub 2011/03/18. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yildiz BO, Suchard MA, Wong ML, McCann SM, Licinio J. Alterations in the dynamics of circulating ghrelin, adiponectin, and leptin in human obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(28):10434–9. Epub 2004/07/03. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403465101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishizawa H, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Maeda N, Kuriyama H, Nagaretani H, Matsuda M, Kondo H, Furuyama N, Kihara S, Nakamura T, Tochino Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Androgens decrease plasma adiponectin, an insulin-sensitizing adipocyte-derived protein. Diabetes. 2002;51(9):2734–41. Epub 2002/08/28. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Attardi BJ, Hild SA, Koduri S, Pham T, Pessaint L, Engbring J, Till B, Gropp D, Semon A, Reel JR. The potent synthetic androgens, dimethandrolone (7alpha,11beta-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone) and 11beta-methyl-19-nortestosterone, do not require 5alpha-reduction to exert their maximal androgenic effects. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2010;122(4):212–8. Epub 2010/07/06. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin AY, Htun M, Swerdloff RS, Diaz-Arjonilla M, Dudley RE, Faulkner S, Bross R, Leung A, Baravarian S, Hull L, Longstreth JA, Kulback S, Flippo G, Wang C. Reexamination of pharmacokinetics of oral testosterone undecanoate in hypogonadal men with a new self-emulsifying formulation. Journal of Andrology. 2012;33(2):190–201. Epub 2011/04/09. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jockenhovel F, Bullmann C, Schubert M, Vogel E, Reinhardt W, Reinwein D, Muller-Wieland D, Krone W. Influence of various modes of androgen substitution on serum lipids and lipoproteins in hypogonadal men. Metabolism. 1999;48(5):590–6. Epub 1999/05/25. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schleich F, Legros JJ. Effects of androgen substitution on lipid profile in the adult and aging hypogonadal male. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151(4):415–24. Epub 2004/10/13. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenny AM, Prestwood KM, Gruman CA, Fabregas G, Biskup B, Mansoor G. Effects of transdermal testosterone on lipids and vascular reactivity in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(7):M460–5. Epub 2002/06/27. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.m460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mommers E, Kersemaekers WM, Elliesen J, Kepers M, Apter D, Behre HM, Beynon J, Bouloux PM, Costantino A, Gerbershagen HP, Gronlund L, Heger-Mahn D, Huhtaniemi I, Koldewijn EL, Lange C, Lindenberg S, Meriggiola MC, Meuleman E, Mulders PF, Nieschlag E, Perheentupa A, Solomon A, Vaisala L, Wu FC, Zitzmann M. Male hormonal contraception: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2572–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uyanik BS, Ari Z, Gumus B, Yigitoglu MR, Arslan T. Beneficial effects of testosterone undecanoate on the lipoprotein profiles in healthy elderly men. A placebo controlled study. Jpn Heart J. 1997;38(1):73–82. Epub 1997/01/01. doi: 10.1536/ihj.38.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bagatell CJ, Heiman JR, Matsumoto AM, Rivier JE, Bremner WJ. Metabolic and behavioral effects of high-dose, exogenous testosterone in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(2):561–7. Epub 1994/08/01. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.2.8045977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meriggiola MC, Marcovina S, Paulsen CA, Bremner WJ. Testosterone enanthate at a dose of 200 mg/week decreases HDL-cholesterol levels in healthy men. Int J Androl. 1995;18(5):237–42. Epub 1995/10/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saad F, Gooren L, Haider A, Yassin A. An exploratory study of the effects of 12 month administration of the novel long-acting testosterone undecanoate on measures of sexual function and the metabolic syndrome. Arch Androl. 2007;53(6):353–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Greco EA, Gianfrilli D, Bonifacio V, Isidori A, Lenzi A, Fabbri A. Effects of testosterone on body composition, bone metabolism and serum lipid profile in middle-aged men: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63(3):280–93. Epub 2005/08/25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedl KE, Hannan CJ, Jr., Jones RE, Plymate SR. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol is not decreased if an aromatizable androgen is administered. Metabolism. 1990;39(1):69–74. Epub 1990/01/01. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swerdloff RS, Wang C, White WB, Kaminetsky J, Gittelman MC, Longstreth JA, Dudley RE, Danoff TM. A New Oral Testosterone Undecanoate Formulation Restores Testosterone to Normal Concentrations in Hypogonadal Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020. Epub 2020/05/10. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosano GM, Sarais C, Zoncu S, Mercuro G. The relative effects of progesterone and progestins in hormone replacement therapy. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2000;15 Suppl 1:60–73. Epub 2000/08/06. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.suppl_1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hernaez A, Soria-Florido MT, Schroder H, Ros E, Pinto X, Estruch R, Salas-Salvado J, Corella D, Aros F, Serra-Majem L, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fiol M, Lapetra J, Elosua R, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Fito M. Role of HDL function and LDL atherogenicity on cardiovascular risk: A comprehensive examination. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218533. Epub 2019/06/28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahdy Ali K, Wonnerth A, Huber K, Wojta J. Cardiovascular disease risk reduction by raising HDL cholesterol--current therapies and future opportunities. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(6):1177–94. Epub 2012/06/26. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, Grundy SM, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1289–97. Epub 2016/09/28. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.