Abstract

The bone remodelling process is closely related to bone health. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts participate in the bone remodelling process under the regulation of various factors inside and outside. Excessive activation of osteoclasts or lack of function of osteoblasts will cause occurrence and development of multiple bone‐related diseases. Ca2+/Calcineurin/NFAT signalling pathway regulates the growth and development of many types of cells, such as cardiomyocyte differentiation, angiogenesis, chondrogenesis, myogenesis, bone development and regeneration, etc. Some evidences indicate that this signalling pathway plays an extremely important role in bone formation and bone pathophysiologic changes. This review discusses the role of Ca2+/Calcineurin/NFAT signalling pathway in the process of osteogenic differentiation, as well as the influence of regulating each component in this signalling pathway on the differentiation and function of osteoblasts, whereby the relationship between Ca2+/Calcineurin/NFAT signalling pathway and osteoblastogenesis could be deeper understood.

Keywords: Ca2+ , calcineurin, calmodulin, NFAT, osteoblastogenesis

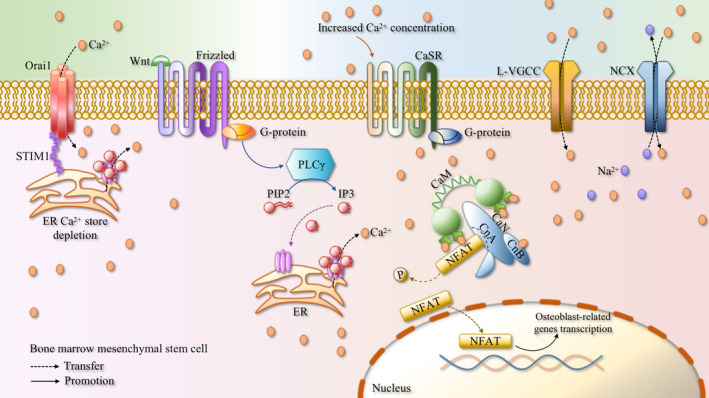

Non‐classical Wnt signalling pathway, Orai1/STIM1, L‐VGCC and NCX can regulate the activity of CaM and CaN by modulating the concentration of Ca2+ in osteogenic precursor cells, thereby affecting the nuclear metastasis of NFAT and the process of osteogenic differentiation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Skeletal system is continuously in the process of dynamic self‐renewal, during that old and damage bone is removed and new bone is generated, this process is also called ‘bone remodelling’. The bone remodelling process will last a lifetime to prevent the accumulation of micro‐damages in bone. Osteoclast‐led bone resorption and osteoblast‐led bone formation are tightly coupled in bone remodelling under various physiological and pathological conditions and can be affected by a variety of inside and outside factors such as hormones, cytokines, mechanical forces, magnetic fields, etc. 1 Excessive activation or lack of function of osteoblasts and osteoclasts is involved in the occurrence and development of various bone‐related diseases, such as osteoporosis, osteopetrosis, periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis, rickets, tumours bone metastases, ankylosing spondylitis and Paget's disease. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

Many signal cascades in cells are activated by the increase of Ca2+ concentration, including calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cell (CaN/NFAT), 6 The Ca2+/calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (Ca2+/CaN/NFAT) signalling pathway was originally discovered in T cells, 7 , 8 which regulates the initiation of T‐cell immune responses and genes expression of immune‐related cytokines. 7 , 8 In subsequent studies, it was found that the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway plays a more significant role in the regulation of cell growth and development, such as regulating cardiomyocyte differentiation, chondrocyte differentiation, myocyte hypertrophy, angiogenesis, myogenesis, skeletal development and regeneration, etc. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Studies have shown that the (Down syndrome critical region 1) DSCR1 gene on chromosome 21 of patients with Down syndrome is overexpressed. DSCR1 gene is highly expressed in myocardium, striated muscle, neuronal cells and T cells, etc., the peptide expressed by this gene regulates CaN through competing with CaN to inhibit the CaN signalling pathway. 16 , 17 The symptom of skeletal dysplasia in Down syndrome patients is thought to be relevant to the overexpression of the DSCR1 gene. 18 Sun et al. 19 discovered that the level of bone formation of mice lacking the CaN Aα subtype was observably reduced and the mice showed osteoporosis. In addition, some studies reported that the activation of CaN was detected in the first batch of bone cells developed at the foetal stage 20 ; acute and rapid bone loss occurred after organ transplantation patients were treated with CaN inhibitors 19 ; mice and rats were treated with equivalent doses of calcineurin inhibitors, and increased bone resorption and bone loss could also be observed. 21 , 22 , 23 A large number of studies have shown that Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway plays an extremely important role in affecting bone resorption, bone formation and bone physiopathological changes. Unlike the role of Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption, which has been thoroughly discussed, the influence of this signalling pathway on osteoblast differentiation still needs to be thoroughly summarized and analysed, besides, the conclusions reached by some studies are also contradictory. Therefore, this review summarizes, analyses and discusses the recent studies on the role of Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway in osteoblast biology, and summarized the different effects of a variety of compounds that have a regulatory effect on the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway in osteogenic differentiation.

2. OSTEOBLASTOGENESIS AND RELATED SIGNALLING PATHWAYS

Osteoblasts are mainly derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (BMSCs). BMSCs have the ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes, many transcription factors participate in the process of inducing BMSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts, such as runt‐related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), β‐catenin and osteoblast‐specific transcription factor (Osterix), etc. 24 After BMSCs are induced to differentiate into osteoblasts, they can secrete an uncalcified bone precursor composed of type I collagen, which is osteoid. 25 Subsequently, mature osteoblasts secrete vesicles, and the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in the vesicles combines with calcium ions to form hydroxyapatite, thereby osteoid calcification is achieved. The cytoplasm of osteoblasts embedded in the osteoid reduces and the osteoblasts then transform into osteocytes. 26 In addition to the bone formation function, osteoblasts can also secrete a variety of cytokines and meet the needs of various physiological and pathological changes in autocrine and paracrine manners. 2 , 27

The differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts is regulated by a variety of signalling pathways, such as wingless‐type MMTV integration site (Wnt), transforming growth factor‐β/bone morphogenetic protein (TGF‐β/BMP), Hedgehogs and fibroblasts growth factor (FGF) signalling pathways. 28 TGF‐β/BMP increase the expression of RUNX2 by activating Smad and mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathways. 29 , 30 , 31 The active fragments of Hedgehogs can bind to the G protein‐coupled receptor Smoothened (Smo), and also caused the increase of RUNX2 expression level by activating Smad. 28 , 32 FGF binds to its receptor to cause receptor dimerization, and promotes osteogenic differentiation by activating its downstream signalling pathways such as MAPK, JNK, PKC and PI3K. 33 In BMSCs, Wnt protein transmits signals through canonical and non‐canonical pathways. 34 The canonical Wnt signalling pathway is mediated by β‐catenin. Under unstimulated condition, β‐catenin in the cytoplasm is phosphorylated by the complex of glycogen synthase kinase‐3β (GSK‐3β), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and Axin, and together form a degradation complex. The complex will be further ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome system. Wnt protein binds to Frizzled and low‐density lipoprotein receptor related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) receptors complex, causing inhibition of GSK‐3β activity, allowing β‐catenin to be released as a monomer and accumulate in the cytoplasm. 35 , 36 Then β‐catenin translocates to the nucleus and induces the expression of its target genes such as RUNX2 and PPARγ. 24 The non‐canonical Wnt signalling pathway also plays an important role in the recruitment, maintenance and differentiation of BMSCs, the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT pathway has been shown to be activated by the non‐canonical Wnt signalling pathway during the differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts. 37 , 38 , 39 The secreted glycoprotein Wnt functions in the form of autocrine or paracrine. Frizzled on the cell membrane belongs to the G protein‐coupled receptor, its N‐terminal can bind to the Wnt protein, and then cause the activation of PLCγ, activated PLCγ increases inositol 1,4,5‐triphosphate (IP3) level, and then promotes the release of Ca2+ from ER into the cytoplasm by activating the IP3 receptor, and activates CaN by activating CaM to promote the nuclear translocation of NFAT. 37 , 40 BMSCs also express calcium‐sensing receptor (CaSR), which activates PLCγ in response to increase in extracellular Ca2+ concentration, thereby producing IP3, promoting the release of Ca2+ from ER and causing the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. 41 Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) can sense the changes in the concentration of Ca2+ in ER. When Ca2+ in ER is depleted, STIM1 aggregates and interact with the Orai1 protein on the cell membrane to open the store‐operated Ca2+ (SOC) channel and accelerate Ca2+ influx, 42 , 43 which further contributes to the activation of CaN and NFAT nuclear translocation. NFAT and Osterix form transcriptional complexes in the nucleus, which subsequently trigger bone morphogenetic protein‐2 (BMP‐2), 44 alpha‐1 type I collagen (ColIα1), 45 osteopontin (OPN), ALP, osteocalcin (OCN) and other osteogenic‐related genes transcription and then promote osteogenic differentiation. 46 Figure 1 exhibits the process of osteoblasts differentiation, which Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway involved in.

FIGURE 1.

Concise schematic diagram of Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway involved in the process of osteoblast differentiation. The combination of Wnt and the N‐terminal of Frizzled causes the activation of PLCγ and increases the level of IP3, which in turn activates the IP3 receptor to promote the release of Ca2+ from ER into the cytoplasm, and activates CaN by CaM to promote the nuclear translocation of NFAT. CaSR activates PLCγ in response to an increase in the extracellular Ca2+ concentration to cause an elevation in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. In addition, the storage depletion of Ca2+ in ER can also lead to Ca2+ influx through Orai1/STIM1. L‐VGCC and NCX all regulate Ca2+ influx, which further results in the activation of the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway. NFAT and Osterix form transcription complexes, which in turn, trigger the transcription of osteoblast‐related genes

3. CA2+/CAN/NFAT SIGNALLING PATHWAY IN OSTEOBLASTOGENESIS

3.1. Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway

Increased intracellular concentration of Ca2+ can activate CaN by interacting with calmodulin (CaM). 47 CaM is dumbbell‐shaped, its C‐terminus and N‐terminus each contain a globular domain, and the two globular domains are connected by a flexible helical joint region. Each globular domain of CaM has a pair of Ca2+ binding sequences, and after binding Ca2+, a hydrophobic surface is exposed. 15 This hydrophobic surface can bind to a variety of CaM target proteins, including CaN. CaN is widely expressed in brain, lung, skeletal muscle, heart valve, myocardium, kidney, spleen, bone and other tissues, 48 , 49 , 50 it is a type of serine/threonine phosphatase, and is a heterodimer, which is structurally composed of catalytic subunits (CnA) and regulatory subunit (CnB). 51 , 52 CnB possesses Ca2+ binding ability, CnA contains multiple domains, the more important of which are the phosphatase domain (catalytic domain), CnB binding domain, CaM binding domain and the self‐inhibitory domain. The CaM binding domain can combine with the hydrophobic surface of CaM, and then be regulated by CaM. 1 Under static state, the self‐inhibition zone covers the phosphatase domain. After Ca2+ binding CnB and CaM/CaM binding CnA, the conformation of CaN alters, the inhibitory zone separates itself from the phosphatase domain, causing CaN to be activated. 53 Activated CaN can dephosphorylate multiple substrates, including NFAT. 44 NFAT contains a few domains, the regulatory domain of which are highly phosphorylated under the inactive state, which covers the nuclear localization sequence and makes the NFAT protein to remain in the cytoplasm. 51 Activated CaN dephosphorylates the serine residues of NFAT regulatory domain, and changes the conformation of NFAT protein, exposing the nuclear localization sequence, which promotes its transfer from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, then NFAT acts as a transcription factor in the nucleus to further cause NFAT‐dependent genes transcription. 9 , 54 , 55 NFAT1‐4 in the NFAT gene family are regulated by CaN and play an irreplaceable role in a variety of biological processes. 8 , 56 Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway.

FIGURE 2.

Brief schematic diagram of Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway. Each globular domain of CaM has a pair of Ca2+ binding sequences, CaM exposes a hydrophobic surface after binding Ca2+. CaN is composed of catalytic subunit (CnA) and regulatory subunit (CnB). CnB is capable to bind Ca2+, CnA contains phosphatase domain (catalytic domain), CnB binding domain, CaM binding domain and autoinhibitory domain, the CaM binding domain can be combined with the hydrophobic surface of CaM and be regulated by it. In the resting state, autoinhibitory domain covers the phosphatase domain, the binding of Ca2+ with CnB and CaM/CaM with CnA make autoinhibitory domain separate itself from phosphatase domain, and CaN is then activated. Activated CaN dephosphorylates the serine residues of the NFAT regulatory domain, exposing the nuclear localization sequence, thereby promoting its transfer from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and acting as a transcription factor in the nucleus to further cause the transcription of NFAT‐dependent genes

3.2. Ca2+ in osteoblastogenesis

Ca2+ participates in a variety of signal transduction processes in cells. It can act as a secondary messenger or as a result of ion channel activation, affecting a variety of cell activities. 57 Ca2+ released during bone resorption will increase the local concentration of extracellular Ca2+, which functions as a coupling factor between osteoclasts and osteoblasts to chemoattractant the migration of osteoblasts through CaSR. 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 Ca2+ plays an important role in the process of osteogenic differentiation. During dentinogenesis, it involves the influx of extracellular Ca2+ and the release of Ca2+ from the intracellular Ca2+ storage. 62

L‐type voltage gated Ca2+ channel (L‐VGCC) participates in the proliferation of human BMSCs, MC3T3‐E1 osteoblasts and human periodontal ligament cells (hPDLCs), and mediates extracellular Ca2+ induced BMP‐2 signalling pathway activation and mineralization. 63 , 64 , 65 It exhibits L‐VGCC dependence in the process of osteogenic differentiation of hPDLCs induced by Ca2+, and the inhibitor of L‐VGCC nifedipine inhibits its osteogenic differentiation. 65

The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) mediates Ca2+ flowing into the cells mainly through reverse exchange, 66 and plays its role on the surface of osteoblasts, regulates the concentration of Ca2+ in osteoblasts and promote bone matrix mineralization. 57 , 67

The CaSR belonging to the G protein‐coupled receptors can sense the extracellular Ca2+ concentration and instantaneously mobilize intracellular Ca2+ flux. 68 Previous studies have shown that CaSR signals mediate the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in vitro and bone formation in vivo, and CaSR agonists can promote the proliferation, differentiation and matrix mineralization of osteoblasts. 41 , 69 , 70 In addition, Ca2+ influx caused by mechanically sensitive channels also promotes osteogenic differentiation 71 ; Orai1 gene knockout leads to impaired osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. 43

Overexpression of Pannexin 3, which is the Ca2+ channel of ER, can increase the intracellular Ca2+ concentration to promote osteogenic differentiation, 72 and the depletion of Ca2+ in the ER induced by IP3 causes STIM1 to accumulate at the junction of the ER and cell membrane, STIM1 interacts with Orai1 protein and activates the SOC channel, causing Ca2+ influx, 73 this process has also been demonstrated to take a part in dental pulp cells (DPCs) osteogenic differentiation and mineralization. 57 , 74

In addition, in the process of Ca2+ regulating osteogenic differentiation, there are also crosstalks between various Ca2+ channels. For example, Ca2+ can affect the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts through the mutual adjustment between CaSR‐L‐VGCC and SOC channel. 57

When supplemented with Ca2+ (1.8–7.8 mM) in the culture medium of BMSCs, the cells exhibited larger area and circumference, as well as enhanced proliferation ability. 64 Extracellular 10–15 mM Ca2+ stimulation can cause the activation of downstream MAPK signalling pathways through Ca2+ influx, thereby promoting the expression of osteogenic differentiation‐related genes such as FGF‐2, BMP‐2, OPN, OCN and RUNX2. 75 , 76 , 77 The study by An et al. revealed that higher concentrations (5.4–16.2 mM) of Ca2+ did not affect the proliferation of DPCs, and did increase the mRNA levels of OCN and OPN, and enhanced their mineralization ability, but the mRNA levels of ALP and COL1A2 in cells decreased, ALP activity was also inhibited. 78 When the extracellular Ca2+ concentration increases to 50 mM, it will hinder the normal adhesion of cells. 79 Therefore, proper concentration of Ca2+ treatment can enhance osteogenic differentiation and mineralization, but excessively high concentrations of Ca2+ may disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis and cause abnormal cell function.

3.3. Calmodulin in osteoblastogenesis

Calmodulin is regulated by intracellular Ca2+ and activates a variety of downstream target proteins after binding Ca2+. It is precisely because there are many types of CaM downstream target proteins, the cell functions that CaM participates in are also diverse, such as inflammation, metabolism, apoptosis and so on. 80 Conversely, CaM can also affect intracellular Ca2+ flux by regulating Ca2+ channels, such as through IP3R and P/Q type calcium channel. 15 CaM participates in the process of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and vitamin D3 in regulating osteoblast differentiation through Ca2+ signals, 81 and Smad1 in the BMP signalling pathway can directly bind to CaM, so that the activity of Smad1 is increased, thereby promoting osteogenic differentiation. 82 Trifluoperazine, a CaM inhibitor, is demonstrated to inhibit the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3‐E1 cells and bone formation in mice, and has a dose‐dependent inhibitory effect on the activity of ALP in rat skull. 83 , 84

3.4. Calcineurin in osteoblastogenesis

The calcium‐sensitive protein CaM can activate calcineurin under the condition of low and continuously increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentration. 85 The activation of CaN can affect a variety of physiological and pathological processes by dephosphorylating various downstream proteins, such as T cell activation, vesicle transport, cell growth and apoptosis and so on. Sun et al. considered that CaN stimulated osteoclast differentiation, whilst inhibiting its bone resorption function, they reported that CaN‐deficient mice showed reduced osteoclastogenesis and increased osteoclast bone resorption activity, these two effects offset the changes in bone mass in mice. They also observed decreased osteoblast differentiation and severe osteoporosis in mice lacking the CaN catalytic subunit, and after TAT sequence was used to introduce CnA into mouse embryonic osteoblast precursor cells (MC3T3‐E1 cells), the expression of osteogenic marker genes RUNX2, ALP, bone sialoprotein (BSP) and OCN increased significantly, so Sun et al. 50 concluded that osteoporosis in CaN‐deficient mice is caused by defects in bone formation. However, Yeo et al. 1 disagree with the above views, they believed that the regulation of CaN signalling pathway in mice not only affected the differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts but also affected the physiological status of endothelial progenitor cells, immune cells, chondrocytes and adipocytes, and all these changes may interfere with osteogenic differentiation. Therefore, Yeo et al. 1 constructed mice model that lacked the CaN regulatory subunit only in osteoblasts, and noticed that the levels of ALP, OCN, and collagen I (Coll I) in vivo rose, osteogenic differentiation degree elevated and bone mass increased. Yeo et al. claimed that low concentrations of cyclosporin A (CsA) (less than 1 μM in vitro, less than 35.5 nM in vivo) could increase the expression of Fos‐related antigen‐2 (Fra‐2), and Fra‐2 acted as a transcription factor to promote OCN and alpha‐2 type I collagen (ColIα2) transcription, thereby promoting osteogenic differentiation and bone formation. 86 , 87 However, high concentrations of CsA (more than 1 μM in vitro and in vivo) inhibited osteogenic differentiation and bone formation. 86 Similar to the effect of CsA, low concentrations of FK506 (less than1 μM in vitro) promoted osteogenic differentiation, 88 whilst even in the presence of BMP‐2, high concentrations of FK506 could reduce the expression of ColIα1 and BSP and other osteogenic‐related genes in vivo and in vitro, then inhibited osteogenic differentiation, and this effect was thought to be exerted by inhibiting the formation of the NFAT‐Osterix‐DNA complex. 45 Sun et al. and Yeo et al., respectively, studied two different subunits of CaN and came to diametrically opposite conclusions. Amongst them, the loss or gain experiments of CnA function in the study of Sun et al. is systemic, whilst the research of Yeo et al. is limited to regulate CnB in mice osteoblasts. Therefore, specifically knockdown or overexpression of CnA in osteoblasts in vivo is necessary, so that it can further analyse its specific influence on osteoblast differentiation. Moreover, when investigating the influence of CaN inhibitors on osteogenic differentiation, researchers used a wide range of CaN inhibitors (from 1 nM to 25 μM) and agreed that high concentrations of CaN inhibitors suppressed osteogenic differentiation, and low concentrations of CaN inhibitors accelerated osteogenic differentiation, but this concentration range of the CaN inhibitor coincides with their concentration that induces osteoblast apoptosis, 89 and it is reported that Endothelin‐1 (ET‐1) activated CaN signalling pathway when acting as an anti‐apoptotic factor for osteoblasts. 90 Therefore, the exact conclusions and specific mechanisms of CaN inhibitors regulating osteoblast differentiation need to be further studied. It is worth noting that many studies have also mentioned the influence of osteoblast function when they reported that osteoblast differentiation is regulated by CaN signalling pathway, and they all claimed that the impacts on osteoblast function are the same as those on osteoblast differentiation, but they did not first culture mature osteoblasts and then regulate CaN signalling pathway, instead, they directly analysed the changes in osteoblast function through the mineralization level of osteoblasts whose differentiation degree has been altered. Therefore, the conclusions about the regulation of osteoblast function by CaN signalling pathway is not precise.

3.5. Nuclear factor of activated T cell in osteoblastogenesis

In the inactive state, NFAT protein localizes in the cytoplasm due to the hyperphosphorylation of its N‐terminal regulatory domain. After Ca2+ activates CaN through CaM, CaN dephosphorylates NFAT and exposes the nuclear localization sequence to cause its nuclear translocation. 91 In the nucleus, NFAT acts as a transcription factor to promote the transcription of target genes and NFATc1 itself. It can be inferred that in the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT pathway, CaN not only regulates the dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of NFAT but also enhances its expression; therefore, NFAT as a transcription factor can cause its own self‐amplification effect. 18 Some previous studies reported that CaN/NFAT had a positive regulatory effect on osteogenic differentiation, and confirmed that the overexpression of NFAT in vivo and in vitro could promote osteogenic differentiation, 45 after expressing the constitutively active variant of NFATc1 in osteoblasts in mice, the mice showed increased bone mass. 92 Similarly, mice lacking NFAT had reduced bone formation and low bone mass, 45 the inactivation of NFATc1 and NFATc2 markedly inhibited the differentiation and function of osteoblasts. 93

Besides, the promoter of the Fra‐2 gene contains three potential NFAT consensus sequences, and the combination of NFAT with Fra‐2 will cause the negative regulation of Fra‐2, 86 Yeo et al. found NFATc1 silencing increased the expression of Fra‐2, then promoted OCN and ColIα2 transcription, and accelerated osteoblastogenesis and bone formation. 86 , 87 Similar to this conclusion, Choo et al. 94 found that the activity of ALP in the osteoblast cell line expressing constitutively active NFATc1 was inhibited, and the protein levels of Osterix and OCN were also reduced. Other studies have exhibited that in the SaOS‐2 human osteosarcoma cell line, NFATc1 inhibits bone formation by negatively regulating oestrogen receptor α (ERα). 95 At present, there are still disagreements on the role of NFAT in the process of osteogenic differentiation, but these studies utilized different treatment methods for NFAT. In in vivo experiments, the constitutive expression or knockout of NFAT in some studies is not limited in the osteoblasts, but systemic. It is known that NFAT regulates a variety of physiological and pathological processes of cells, amongst them, the immune response can also have a certain effect on bone formation. Therefore, these conclusions may be not that accurate. However, the contrary conclusions drawn from the overexpression or knockout of NFAT in in vitro experiments still need to be further verified, and it is also necessary to determine whether it is affected by different types of osteoblast precursor cells, which are used and different transfection methods.

4. DIVERSE CA2+/CAN/NFAT SIGNALLING PATHWAY MODULATING COMPOUNDS, WHICH REGULATE OSTEOGENIC DIFFERENTIATION

Decreased differentiation or dysfunction of osteoblasts will lead to a variety of skeletal diseases. The Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway has been shown to be closely related with the physiological activities of osteoblasts. We have summarized compounds that have a regulatory effect on this signalling pathway and at the same time modulate osteoblastogenesis, aiming to provide new ideas for the exploration of treatment options for osteogenesis‐related diseases. Table 1 exhibits the effect of compounds regulating Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway on the differentiation of osteoblasts.

TABLE 1.

The impact of Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway modulating compounds on osteoblasts

| Targets | Compounds | Osteoblastogenesis | Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | Cell type | Differentiation | Concentration | Cell type | Impact | |||

| Ca2+ | KMUP−1 | 5–10 μM | BMSCs/MC3T3‐E1 | ↑ | 10 μM | RAW264.7 | ↓ | 96, 97 |

| Zinc | 1–50 μM | BMSCs/MC3T3‐E1 | ↓ | 10–30 μM | BMMs | ↓ | 98, 99, 100, 101 | |

| Cyanidin | 50–200 μM | MC3T3‐E1 | ↑ |

80–300 μM 1–100 μg/ml 10 μM 5–10 μM |

Pancreatic β cells PC12 cells C2C12 myoblasts RAW264.7 |

↑ ↑ ↑ ↓ |

102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109 | |

| Harpagoside | 0.032–4 μM | MC3T3‐E1 | ↑ | 100 μM | BMMs | ↓ | 110, 111, 112 | |

| Artesunate | 2.5–10 μM | BMSCs | ↑ |

1.5–2.0 μM 15 µg/ml 16–32 μM 12.5 μM |

ASMCs Erythrocytes HUVECs RAW264.7 |

↑ ↑ ↑ ↓ |

113, 114, 115, 116, 117 | |

| Apocynin | 0.1–1 μM | MC3T3‐E1 | ↑ | 1 μM | BMMs | ↓ | 118, 119 | |

| Amyloid β peptide | 0.5–10 μM | MC3T3‐E1 | ↑ | 1–5 μM | BMMs | ↑ | 120, 121, 122 | |

| CaM | KN−93 |

2 mM 10 μM |

C2C12 cells BMSCs |

↓ ↓ |

2 mM 10 μM |

C2C12 cells BMSCs |

↓ ↓ |

123, 124 |

| Trifluoperazine | 10 μM | Calvarial model of mouse pups | ↓ | 10 μM | Calvarial model of mouse pups | ↓ | 83, 84 | |

| CaN | CsA |

<1 μM >1 μM |

BMSCs/MC3T3‐E1 |

↑ ↓ |

<1 μM >1 μM |

BMSCs/MC3T3‐E1 |

↓ ↓ |

86, 87 |

| FK506 |

<1 μM >1 μM |

BMSCs/MC3T3‐E1 |

↑ ↓ |

<1 μM >1 μM |

BMSCs/MC3T3‐E1 | ↑ ↓ | 45, 88 | |

4.1. KMUP‐1

Xanthine derivative KMUP‐1 (7‐[2‐[4‐(2‐chlorophenyl)piperazinyl]ethyl]‐1,3‐dimethylxanthine) can inhibit phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity, Liou et al. found that 5–10 μM KMUP‐1 can induce osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and MC3T3‐E1 cells and promote mineralization. 96 For the time being, there is no research showing the effect of KMUP‐1 on Ca2+ signal in BMSCs, MC3T3‐E1 cells or osteoblasts, but Liou et al. 97 detected that 10 μM KMUP‐1 in RAW264.7 cells suppressed the RANKL‐induced Ca2+ oscillation and Ca2+ signal activation.

4.2. Zinc

Zinc is essential in the process of skeletal development, 1–50 μM zinc has been shown to inhibit osteoblast apoptosis and promote the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts, 98 and adding zinc (25–200 mg/dl) to the cultured chicken embryo tibia has been demonstrated to lead to a concentration‐dependent increase in tibial ALP activity and an increase in the level of bone formation, 99 physiological concentrations of zinc (25–200 mg/dl) have also been shown to increase bone resorption in tibia of chicken embryos. 100 Similarly, the effect of zinc on Ca2+ in osteoblast‐related cells has not been exhibited, but it has been demonstrated that 10–30 μM zinc inhibited the increase in Ca2+ concentration in BMMs induced by RANKL, and 30–100 μm zinc inhibited the CaN activity of BMMs. 101

4.3. Cyanidin

Cyanidin found in fruits and vegetables is a natural anthocyanin. Some previous studies have found that 50–200 μM cyanidin accelerated the proliferation, osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of MC3T3‐E1 cells. 102 , 103 , 104 In rat pancreatic β cells, 80–300 μM cyanidin activates type I voltage‐dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC) to promote Ca2+ influx, thereby increasing the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, the intracellular Ca2+ level increased the highest level when treated with 100 μM cyanidin. 105 Similarly, 1–100 μg/ml cyanidin activates P2Y receptor‐mediated PLC in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells and causes Ca2+ influx, 106 Toshiya et al. claimed that 10 μM cyanidin could increase the level of intracellular cAMP by inhibiting PDE activity of the mouse C2C12 myoblasts, thereby promoting the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration. 107 However, in colon carcinoma cells, cyanidin inhibited the increase in intracellular Ca2+ level caused by neurotensin, 108 and cyanidin at concentrations of 5–10 μM reduced the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration of RAW264.7 cells induced by RANKL. 109

4.4. Harpagoside

Harpagoside is an iridoid glycoside extracted from harpagophytum procumbens var. sublobatum. Harpagide at concentrations of 0.032–4 μM promotes the osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of MC3T3‐E1 cells in a concentration‐dependent manner. 110 , 111 Kim et al. 112 found that 100 μM Harpagoside inhibits the activation of Syk, Btk and PLCγ2 induced by RANKL in BMMs, further attenuates intracellular Ca2+ oscillations and reduces Ca2+ level.

4.5. Artesunate

Artesunate (ART) is a derivative of artemisinin, which has anti‐viral, anti‐tumour and anti‐malaria functions. Zeng et al. 113 observed that 2.5–10 μM ART inhibited the expression of DKK1 in hBMSCs and increased the protein levels of cyclin D1, β‐catenin and c‐myc in a dose‐dependent manner, thereby promoting the process of osteogenic differentiation. Zeng et al. 114 proved that 12.5 μM ART inhibited the activation of PLCγ1 and the increase of Ca2+ level induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells, and also reduced the protein expression of the catalytic subunit of CaN. However, it is also reported that in airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs), 1.5 and 2.0 mM ART significantly increased the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, 115 Alzoubi et al. 116 also reported that the treatment of 15 µg/ml ART can significantly increase the intracellular Ca2+ level of erythrocytes, Wu et al. 117 found that human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) cultured in Hanks solution containing Ca2+ rapidly increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration under the treatment of 16–32 μM ART.

4.6. Apocynin

The inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, apocynin, is a kind of methoxy‐substituted catechol. When MC3T3‐E1 cells are exposed to antimycin A and resulting in excessive ROS production, 0.01–1 μM apocynin can scavenge ROS, protect MC3T3‐E1 cells and promote their osteogenic differentiation. 118 In BMMs, apocynin reduces Ca2+ influx by blocking Ca2+ channels except the two pore channel 2 (TPC2) and inositol 1,4,5‐triphosphate receptor 1 (IP3R1), causing reduction of intracellular Ca2+ concentration. 119

4.7. Amyloid β peptide

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by the loss of synapses and neurons in the elderly, and the accumulation of amyloid β peptide (Aβ) is its hallmark. Research by Yang et al. 120 showed that 0.5–10 μM Aβ can activate the Wnt signalling pathway by binding to LRP5/6 in MC3T3‐E1 cells, thereby promoting osteogenic differentiation. Aβ induces synaptic dysfunction by activating N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptors (NMDARs) to increase intracellular Ca2+ levels and activate related downstream signals. 121 Besides, Li et al. 122 also found that 1–5 μM Aβ increased intracellular Ca2+ levels and activated the Ca2+ signalling pathway during the process of inducing osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in BMMs.

4.8. KN‐93

In osteoblast precursor cells, after Ca2+ binds to CaM, CaM activates a variety of target proteins, including calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase (CaMK). Choi et al. demonstrated that CaMKII participated in osteogenic differentiation of C2C12 mouse pre‐myoblast cell line induced by BMP‐4, and in the process of osteoblastogenesis, KN‐93 (2 mM), the inhibitor of CaMKII, blocked the osteogenic differentiation process of C2C12 cells induced by BMP‐4. 123 Similarly, the research by Shin et al. 124 reported that 10 μM KN‐93 inhibited the osteogenic differentiation and mineral deposition of hMSCs.

4.9. Trifluoperazine

Trifluoperazine (TFP) can inhibit the activity of CaM and further restrain the activation of CaMKII. 10 μM TFP inhibits osteogenic differentiation, and also shows the ability to reduce the formation and mineralization of osteoblasts in the calvarial model of mouse pups. 83 Komoda et al. 84 also confirmed the inhibitory effect of TFP on ALP activity in rat calvaria and its inhibitory effect on the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3‐E1 cells in vitro.

4.10. Cyclosporin A and FK506

Cyclosporin A and FK506 are CaN inhibitors and are widely used to reduce rejection reaction after organ transplantation. Low concentrations of CsA (less than 1 μM in vitro and 35.5 nM in vivo) have been shown to increase the expression of Fra‐2 to promote the transcription of osteogenic genes, thereby promoting osteogenic differentiation. 86 , 87 High concentrations of CsA (more than 1 μM in vitro and in vivo) inhibit osteogenic differentiation and bone formation. 86 Similarly, low concentrations of FK506 (less than 1 μM in vitro) promote osteogenic differentiation, 88 whilst high concentrations of FK506 can also reduce BMP‐2 induced osteogenic differentiation both in vivo and in vitro. 45 The osteoinhibitory effect of high concentration of CsA and FK506 is believed to be exerted by inhibiting the formation of NFAT‐Osterix‐DNA complex.

5. SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

A variety of existing evidences indicate that the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway, which is an extremely important part of growth and development, is inextricably linked to bone formation. The regulation of each components in the signal pathway, such as activation, inhibition, overexpression, silencing, etc., often resulting in changes in the process of osteoblast differentiation in vivo and in vitro. In the process of osteoblast differentiation, the non‐canonical Wnt pathway triggers the activation of Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway, then NFAT and Osterix form transcription complexes to induce the expression of downstream osteogenic‐related genes. Some research teams studied the effect of CaN on osteogenic differentiation by means of gene deletion or gain‐of‐function but came to diametrically opposite conclusions. The most important differences in the experimental methods of these teams lie in the different CaN subunits they target, and whether the intervention is limited to osteoblasts. In addition, the osteogenic function of NFAT has also been questioned, some studies claimed that it acted as a transcription factor to promote the expression of osteoblast‐related genes, whilst some other studies believed that NFAT inhibited the differentiation of osteoblasts by inhibiting Fra‐2. Most researchers agreed that low‐concentration CaN inhibitors promoted osteogenic differentiation, and high‐concentration CaN inhibitors suppressed the process of osteogenic differentiation, but no specific limit of the concentration of CaN inhibitor and the actual mechanism were given to explain the reason. In connection with the study of CaN inhibitors in osteoclasts, we speculate that immunophilin should also be included in the analysis of its influence on osteogenic differentiation.

A variety of existing compounds have the ability to promote or inhibit osteogenic differentiation, whilst regulating the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway. However, we have found that some compounds positively regulate Ca2+ signal and promote osteogenic differentiation, whilst some compounds negatively regulate Ca2+ signal and promotes osteogenic differentiation as well. The reason for this paradox may lie in the different types of cells used in these studies for Ca2+ signal and the ability to regulate osteogenic differentiation, and the different application concentrations of the compounds, or the signalling pathway involved in the compounds driving osteogenic differentiation is not Ca2+/CaN/NFAT but other signalling pathways. The information we have collected and summarized can be used to investigate the relationship between the Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway and osteogenic differentiation as well as providing some ideas for exploring better treatment options for regulating bone formation‐related diseases, and these remaining uncertain mechanisms require further research.

Over the years, the relationship between Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway and bone metabolism has been explored in many ways, this signalling pathway has a wide range of effects on cell fate, and the mechanisms involved are far‐reaching. There are still many unknown or unexplained relationships between Ca2+/CaN/NFAT signalling pathway and osteoblastogenesis, further exploration in this field is needed to broaden the way for the study of bone formation regulation and bone‐related diseases development.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.X. and R.R. conceived the aims and structure of the review. R.R. and J.G. collected the articles and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Y.C., Y.Z. and L.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript. W.X. acquired the funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82072405 and Nos. 81571816).

Ren R, Guo J, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Chen L, Xiong W. The role of Ca2+/Calcineurin/NFAT signalling pathway in osteoblastogenesis. Cell Prolif. 2021;54:e13122. 10.1111/cpr.13122

Ren and Guo have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All the data are available from the corresponding author by request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yeo H, Beck LH, Thompson SR, et al. Conditional disruption of calcineurin B1 in osteoblasts increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(48):35318‐35327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saint‐Pastou Terrier C, Gasque P. Bone responses in health and infectious diseases: a focus on osteoblasts. J Infect. 2017;75(4):281‐292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baum R, Gravallese EM. Bone as a target organ in rheumatic disease: impact on osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(1):1‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paul Tuck S, Layfield R, Walker J, Mekkayil B, Francis R. Adult Paget's disease of bone: a review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(12):2050‐2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyce BF. Advances in the regulation of osteoclasts and osteoclast functions. J Dent Res. 2013;92(10):860‐867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crabtree GR. Calcium, calcineurin, and the control of transcription. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(4):2313‐2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707‐747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S67‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horsley V, Pavlath GK. NFAT: ubiquitous regulator of cell differentiation and adaptation. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(5):771‐774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de la Pompa JL, Timmerman LA, Takimoto H, et al. Role of the NF‐ATc transcription factor in morphogenesis of cardiac valves and septum. Nature. 1998;392(6672):182‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ranger AM, Grusby MJ, Hodge MR, et al. The transcription factor NF‐ATc is essential for cardiac valve formation. Nature. 1998;392(6672):186‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ranger AM, Gerstenfeld LC, Wang J, et al. The nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) transcription factor NFATp (NFATc2) is a repressor of chondrogenesis. J Exp Med. 2000;191(1):9‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graef IA, Chen F, Chen L, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Signals transduced by Ca(2+)/calcineurin and NFATc3/c4 pattern the developing vasculature. Cell. 2001;105(7):863‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hernández GL, Volpert OV, Iñiguez MA, et al. Selective inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor‐mediated angiogenesis by cyclosporin A: roles of the nuclear factor of activated T cells and cyclooxygenase 2. J Exp Med. 2001;193(5):607‐620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zayzafoon M. Calcium/calmodulin signaling controls osteoblast growth and differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97(1):56‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuentes JJ, Genescà L, Kingsbury TJ, et al. DSCR1, overexpressed in Down syndrome, is an inhibitor of calcineurin‐mediated signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(11):1681‐1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan B, Greenan G, McKeon F, Ellenberger T. Identification of a peptide fragment of DSCR1 that competitively inhibits calcineurin activity in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(37):13075‐13080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun L, Peng Y, Zaidi N, et al. Evidence that calcineurin is required for the genesis of bone‐resorbing osteoclasts. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(1):F285‐F291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun L, Zhu LL, Zaidi N, et al. Cellular and molecular consequences of calcineurin A alpha gene deletion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:216‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erkut A, Tumkaya L, Balik MS, et al. The effect of prenatal exposure to 1800 MHz electromagnetic field on calcineurin and bone development in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2016;31(2):74‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huynh H, Wan Y. mTORC1 impedes osteoclast differentiation via calcineurin and NFATc1. Commun Biol. 2018;1:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cvetkovic M, Mann GN, Romero DF, et al. The deleterious effects of long‐term cyclosporine A, cyclosporine G, and FK506 on bone mineral metabolism in vivo. Transplantation. 1994;57(8):1231‐1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sass DA, Bowman AR, Yuan Z, Ma Y, Jee WS, Epstein S. Alendronate prevents cyclosporin A‐induced osteopenia in the rat. Bone. 1997;21(1):65‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo J, Ren R, Yao X, et al. PKM2 suppresses osteogenesis and facilitates adipogenesis by regulating β‐catenin signaling and mitochondrial fusion and fission. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(4):3976‐3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balcerzak M, Hamade E, Zhang L, et al. The roles of annexins and alkaline phosphatase in mineralization process. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50(4):1019‐1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crockett JC, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP, Hocking LJ, Helfrich MH. Bone remodelling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 7):991‐998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prideaux M, Findlay DM, Atkins GJ. Osteocytes: the master cells in bone remodelling. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;28:24‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, et al. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(7):1128‐1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen G, Deng C, Li YP. TGF‐β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(2):272‐288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kang Q, Song WX, Luo Q, et al. A comprehensive analysis of the dual roles of BMPs in regulating adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18(4):545‐559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deng ZL, Sharff KA, Tang N, et al. Regulation of osteogenic differentiation during skeletal development. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2001‐2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spinella‐Jaegle S, Rawadi G, Kawai S, et al. Sonic hedgehog increases the commitment of pluripotent mesenchymal cells into the osteoblastic lineage and abolishes adipocytic differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 11):2085‐2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jackson RA, Nurcombe V, Cool SM. Coordinated fibroblast growth factor and heparan sulfate regulation of osteogenesis. Gene. 2006;379:79‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Capulli M, Paone R, Rucci N. Osteoblast and osteocyte: games without frontiers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;561:3‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Koide M, et al. The regulation of bone metabolism and disorders by Wnt signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Duan P, Bonewald LF. The role of the wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway in formation and maintenance of bone and teeth. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;77(Pt A):23‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baksh D, Tuan RS. Canonical and non‐canonical Wnts differentially affect the development potential of primary isolate of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212(3):817‐826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu Y, Rubin B, Bodine PV, Billiard J. Wnt5a induces homodimerization and activation of Ror2 receptor tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105(2):497‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tamura M, Nemoto E, Sato MM, Nakashima A, Shimauchi H. Role of the Wnt signaling pathway in bone and tooth. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2010;2:1405‐1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olivares‐Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Hutton DL, et al. Role of non‐canonical Wnt signaling in osteoblast maturation on microstructured titanium surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(6):2740‐2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goltzman D, Hendy GN. The calcium‐sensing receptor in bone–mechanistic and therapeutic insights. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(5):298‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim MS, Yang YM, Son A, et al. RANKL‐mediated reactive oxygen species pathway that induces long lasting Ca2+ oscillations essential for osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):6913‐6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robinson LJ, Blair HC, Barnett JB, Soboloff J. The roles of Orai and Stim in bone health and disease. Cell Calcium. 2019;81:51‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tomita M, Reinhold MI, Molkentin JD, Naski MC. Calcineurin and NFAT4 induce chondrogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(44):42214‐42218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koga T, Matsui Y, Asagiri M, et al. NFAT and Osterix cooperatively regulate bone formation. Nat Med. 2005;11(8):880‐885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Celil Aydemir AB, Minematsu H, Gardner TR, Kim KO, Ahn JM, Lee FY. Nuclear factor of activated T cells mediates fluid shear stress‐ and tensile strain‐induced Cox2 in human and murine bone cells. Bone. 2010;46(1):167‐175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aramburu J, Rao A, Klee CB. Calcineurin: from structure to function. Curr Top Cell Regul. 2000;36:237‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kalkan Y, Tümkaya L, Bostan H, Tomak Y, Yılmaz A. Effects of sugammadex on immunoreactivity of calcineurin in rat testes cells after neuromuscular block: a pilot study. J Mol Histol. 2012;43(2):235‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: form and function. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1483‐1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun L, Blair HC, Peng Y, et al. Calcineurin regulates bone formation by the osteoblast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(47):17130‐17135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17(18):2205‐2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klee CB, Crouch TH, Krinks MH. Calcineurin: a calcium‐ and calmodulin‐binding protein of the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76(12):6270‐6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shibasaki F, Hallin U, Uchino H. Calcineurin as a multifunctional regulator. J Biochem. 2002;131(1):1‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takayanagi H. The role of NFAT in osteoclast formation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:227‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Song I, Kim JH, Kim K, Jin HM, Youn BU, Kim N. Regulatory mechanism of NFATc1 in RANKL‐induced osteoclast activation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(14):2435‐2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Graef IA, Chen F, Crabtree GR. NFAT signaling in vertebrate development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11(5):505‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. An S. The emerging role of extracellular Ca(2+) in osteo/odontogenic differentiation and the involvement of intracellular Ca (2+) signaling: from osteoblastic cells to dental pulp cells and odontoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(3):2169‐2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Aguirre A, González A, Planell JA, Engel E. Extracellular calcium modulates in vitro bone marrow‐derived Flk‐1+ CD34+ progenitor cell chemotaxis and differentiation through a calcium‐sensing receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393(1):156‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Duncan RL, Akanbi KA, Farach‐Carson MC. Calcium signals and calcium channels in osteoblastic cells. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18(2):178‐190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chai YC, Carlier A, Bolander J, et al. Current views on calcium phosphate osteogenicity and the translation into effective bone regeneration strategies. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(11):3876‐3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Breitwieser GE. Extracellular calcium as an integrator of tissue function. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(8):1467‐1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Krebs J, Agellon LB, Michalak M. Ca(2+) homeostasis and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress: An integrated view of calcium signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(1):114‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Catterall WA, Swanson TM. Structural basis for pharmacology of voltage‐gated sodium and calcium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88(1):141‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Barradas AM, Fernandes HA, Groen N, et al. A calcium‐induced signaling cascade leading to osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33(11):3205‐3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Koori K, Maeda H, Fujii S, et al. The roles of calcium‐sensing receptor and calcium channel in osteogenic differentiation of undifferentiated periodontal ligament cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;357(3):707‐718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tsumura M, Okumura R, Tatsuyama S, et al. Ca2+ extrusion via Na+‐Ca2+ exchangers in rat odontoblasts. J Endod. 2010;36(4):668‐674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jung SY, Park YJ, Park YJ, Cha SH, Lee MZ, Suh CK. Na+‐Ca2+ exchanger modulates Ca2+ content in intracellular Ca2+ stores in rat osteoblasts. Exp Mol Med. 2007;39(4):458‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wei WC, Jacobs B, Becker EB, Glitsch MD. Reciprocal regulation of two G protein‐coupled receptors sensing extracellular concentrations of Ca2+ and H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(34):10738‐10743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang X, Meng S, Huang Y, et al. Electrospun gelatin/β‐TCP composite nanofibers enhance osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and in vivo bone formation by activating Ca (2+) ‐sensing receptor signaling. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:507154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yasukawa T, Hayashi M, Tanabe N, et al. Involvement of the calcium‐sensing receptor in mineral trioxide aggregate‐induced osteogenic gene expression in murine MC3T3‐E1 cells. Dent Mater J. 2017;36(4):469‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhou T, Gao B, Fan Y, et al. Piezo1/2 mediate mechanotransduction essential for bone formation through concerted activation of NFAT‐YAP1‐ß‐catenin. Elife. 2020;9:e52779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ishikawa M, Iwamoto T, Nakamura T, Doyle A, Fukumoto S, Yamada Y. Pannexin 3 functions as an ER Ca(2+) channel, hemichannel, and gap junction to promote osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(7):1257‐1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chung WY, Jha A, Ahuja M, Muallem S. Ca(2+) influx at the ER/PM junctions. Cell Calcium. 2017;63:29‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen Y, Ramachandran A, Zhang Y, Koshy R, George A. The ER Ca(2+) sensor STIM1 can activate osteoblast and odontoblast differentiation in mineralized tissues. Connect Tissue Res. 2018;59(suppl 1):6‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kanaya S, Xiao B, Sakisaka Y, et al. Extracellular calcium increases fibroblast growth factor 2 gene expression via extracellular signal‐regulated kinase 1/2 and protein kinase A signaling in mouse dental papilla cells. J Appl Oral Sci. 2018;26:e20170231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li S, He H, Zhang G, Wang F, Zhang P, Tan Y. Connexin43‐containing gap junctions potentiate extracellular Ca²⁺‐induced odontoblastic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells via Erk1/2. Exp Cell Res. 2015;338(1):1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kanaya S, Nemoto E, Ebe Y, Somerman MJ, Shimauchi H. Elevated extracellular calcium increases fibroblast growth factor‐2 gene and protein expression levels via a cAMP/PKA dependent pathway in cementoblasts. Bone. 2010;47(3):564‐572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. An S, Ling J, Gao Y, Xiao Y. Effects of varied ionic calcium and phosphate on the proliferation, osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human periodontal ligament cells in vitro. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47(3):374‐382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Sasaki J, et al. Effect of calcium ion concentrations on osteogenic differentiation and hematopoietic stem cell niche‐related protein expression in osteoblasts. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(8):2467‐2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. O'Day DH. CaMBOT: profiling and characterizing calmodulin‐binding proteins. Cell Signal. 2003;15(4):347‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wong GL. Actions of parathyroid hormone and 1,25‐dihydroxycholecalciferol on citrate decarboxylation in osteoblast‐like bone cells differ in calcium requirement and in sensitivity to trifluoperazine. Calcif Tissue Int. 1983;35(4–5):426‐431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Scherer A, Graff JM. Calmodulin differentially modulates Smad1 and Smad2 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(52):41430‐41438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zayzafoon M, Fulzele K, McDonald JM. Calmodulin and calmodulin‐dependent kinase IIalpha regulate osteoblast differentiation by controlling c‐fos expression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(8):7049‐7059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Komoda T, Ikeda E, Nakatani Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of phenothiazine derivatives on bone in vivo and osteoblastic cells in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34(21):3885‐3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fajardo VA, Watson CJF, Bott KN, et al. Neurogranin is expressed in mammalian skeletal muscle and inhibits calcineurin signaling and myoblast fusion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;317(5):C1025‐C1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yeo H, Beck LH, McDonald JM, Zayzafoon M. Cyclosporin A elicits dose‐dependent biphasic effects on osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Bone. 2007;40(6):1502‐1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bozec A, Bakiri L, Jimenez M, Schinke T, Amling M, Wagner EF. Fra‐2/AP‐1 controls bone formation by regulating osteoblast differentiation and collagen production. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(6):1093‐1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tang L, Ebara S, Kawasaki S, Wakabayashi S, Nikaido T, Takaoka K. FK506 enhanced osteoblastic differentiation in mesenchymal cells. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26(1):75‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Oh YL, Han SY, Mun KH, et al. Cyclosporine‐induced apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(7):2237‐2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Van Sant C, Wang G, Anderson MG, Trask OJ, Lesniewski R, Semizarov D. Endothelin signaling in osteoblasts: global genome view and implication of the calcineurin/NFAT pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(1):253‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sitara D, Aliprantis AO. Transcriptional regulation of bone and joint remodeling by NFAT. Immunol Rev. 2010;233(1):286‐300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Winslow MM, Pan M, Starbuck M, et al. Calcineurin/NFAT signaling in osteoblasts regulates bone mass. Dev Cell. 2006;10(6):771‐782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Canalis E, Schilling L, Eller T, Yu J. Nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 and 2 are required for vertebral homeostasis. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(11):8520‐8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Choo MK, Yeo H, Zayzafoon M. NFATc1 mediates HDAC‐dependent transcriptional repression of osteocalcin expression during osteoblast differentiation. Bone. 2009;45(3):579‐589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Penolazzi L, Zennaro M, Lambertini E, et al. Induction of estrogen receptor alpha expression with decoy oligonucleotide targeted to NFATc1 binding sites in osteoblasts. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(6):1457‐1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Liou SF, Hsu JH, Chu HC, Lin HH, Chen IJ, Yeh JL. KMUP‐1 promotes osteoblast differentiation through cAMP and cGMP pathways and signaling of BMP‐2/Smad1/5/8 and Wnt/β‐catenin. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(9):2038‐2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Liou SF, Hsu JH, Lin IL, et al. KMUP‐1 suppresses RANKL‐induced osteoclastogenesis and prevents ovariectomy‐induced bone loss: roles of MAPKs, Akt, NF‐κB and calcium/calcineurin/NFATc1 pathways. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. O'Connor JP, Kanjilal D, Teitelbaum M, Lin SS, Cottrell JA. Zinc as a therapeutic agent in bone regeneration. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(10):2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Chen D, Waite LC, Pierce WM Jr. In vitro effects of zinc on markers of bone formation. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1999;68(3):225‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Chen D, Waite LC, Pierce WM Jr. In vitro bone resorption is dependent on physiological concentrations of zinc. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1998;61(1):9‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Park KH, Park B, Yoon DS, et al. Zinc inhibits osteoclast differentiation by suppression of Ca2+‐Calcineurin‐NFATc1 signaling pathway. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Hu B, Chen L, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhou B. Cyanidin‐3‐glucoside regulates osteoblast differentiation via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. ACS Omega. 2021;6(7):4759‐4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Jang WS, Seo CR, Jang HH, et al. Black rice (Oryza sativa L.) extracts induce osteoblast differentiation and protect against bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Food Funct. 2015;6(1):265‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Park KH, Gu DR, So HS, Kim KJ, Lee SH. Dual role of cyanidin‐3‐glucoside on the differentiation of bone cells. J Dent Res. 2015;94(12):1676‐1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Suantawee T, Elazab ST, Hsu WH, Yao S, Cheng H, Adisakwattana S. Cyanidin stimulates insulin secretion and pancreatic β‐cell gene expression through activation of l‐type voltage‐dependent Ca(2+) channels. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Perveen S, Yang JS, Ha TJ, Yoon SH. Cyanidin‐3‐glucoside Inhibits ATP‐induced intracellular free Ca(2+) concentration, ROS formation and mitochondrial depolarization in PC12 cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18(4):297‐305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Matsukawa T, Motojima H, Sato Y, Takahashi S, Villareal MO, Isoda H. Upregulation of skeletal muscle PGC‐1α through the elevation of cyclic AMP levels by Cyanidin‐3‐glucoside enhances exercise performance. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Briviba K, Abrahamse SL, Pool‐Zobel BL, Rechkemmer G. Neurotensin‐and EGF‐induced metabolic activation of colon carcinoma cells is diminished by dietary flavonoid cyanidin but not by its glycosides. Nutr Cancer. 2001;41(1–2):172‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Cheng J, Zhou L, Liu Q, et al. Cyanidin Chloride inhibits ovariectomy‐induced osteoporosis by suppressing RANKL‐mediated osteoclastogenesis and associated signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(3):2502‐2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Chung HJ, Kyung Kim W, Joo Park H, et al. Anti‐osteoporotic activity of harpagide by regulation of bone formation in osteoblast cell culture and ovariectomy‐induced bone loss mouse models. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;179:66‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Chung HJ, Kim WK, Oh J, et al. Anti‐osteoporotic activity of harpagoside by upregulation of the BMP2 and WNT signaling pathways in osteoblasts and suppression of Differentiation in Osteoclasts. J Nat Prod. 2017;80(2):434‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Kim JY, Park SH, Baek JM, et al. Harpagoside inhibits RANKL‐induced osteoclastogenesis via Syk‐Btk‐PLCγ2‐Ca(2+) signaling pathway and prevents inflammation‐mediated bone loss. J Nat Prod. 2015;78(9):2167‐2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Zeng HB, Dong LQ, Xu C, Zhao XH, Wu LG. Artesunate promotes osteoblast differentiation through miR‐34a/DKK1 axis. Acta Histochem. 2020;122(7):151601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Zeng XZ, Zhang YY, Yang Q, et al. Artesunate attenuates LPS‐induced osteoclastogenesis by suppressing TLR4/TRAF6 and PLCγ1‐Ca(2+)‐NFATc1 signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(2):229‐236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wang Y, Wang A, Zhang M, et al. Artesunate attenuates airway resistance in vivo and relaxes airway smooth muscle cells in vitro via bitter taste receptor‐dependent calcium signalling. Exp Physiol. 2019;104(2):231‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Alzoubi K, Calabrò S, Bissinger R, Abed M, Faggio C, Lang F. Stimulation of suicidal erythrocyte death by artesunate. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34(6):2232‐2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Wu GD, Zhou HJ, Wu XH. Apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced by artesunate. Vascul Pharmacol. 2004;41(6):205‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Lee YS, Choi EM. Apocynin stimulates osteoblast differentiation and inhibits bone‐resorbing mediators in MC3T3‐E1 cells. Cell Immunol. 2011;270(2):224‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Soares MPR, Silva DP, Uehara IA, et al. The use of apocynin inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Cell Biol Int. 2019;43(5):466‐475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Yang B, Li S, Chen Z, et al. Amyloid β peptide promotes bone formation by regulating Wnt/β‐catenin signaling and the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Faseb j. 2020;34(3):3583‐3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Tu S, Okamoto S, Lipton SA, Xu H. Oligomeric Aβ‐induced synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Li S, Yang B, Teguh D, Zhou L, Xu J, Rong L. Amyloid β peptide enhances RANKL‐induced osteoclast activation through NF‐κB, ERK, and calcium oscillation signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(10):1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Choi YH, Choi JH, Oh JW, Lee KY. Calmodulin‐dependent kinase II regulates osteoblast differentiation through regulation of Osterix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432(2):248‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Shin MK, Kim MK, Bae YS, et al. A novel collagen‐binding peptide promotes osteogenic differentiation via Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II/ERK/AP‐1 signaling pathway in human bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Signal. 2008;20(4):613‐624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available from the corresponding author by request.