Abstract

Ancient sublineage of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype is endemic and prevalent in East Asia and rare in other world regions. While these strains are mainly drug susceptible, we recently identified a novel clonal group Beijing 1071-32 within this sublineage emerging in Siberia, Russia and present in other Russian regions. This cluster included only multi/extensive drug resistant (MDR/XDR) isolates. Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the available WGS data, we identified three synonymous SNPs in the genes Rv0144, Rv0373c, and Rv0334 that were specific for the Beijing 1071-32-cluster and developed a real-time PCR assay for their detection. Analysis of the 2375 genetically diverse M. tuberculosis isolates collected between 1996 and 2020 in different locations (European and Asian parts of Russia, former Soviet Union countries, Albania, Greece, China, Vietnam, Japan and Brazil), confirmed 100% specificity and sensitivity of this real-time PCR assay. Moreover, the epidemiological importance of this strain and the newly developed screening assay is further stressed by the fact that all identified Beijing 1071-32 isolates were found to exhibit MDR genotypic profiles with concomitant resistance to additional first-line drugs due to a characteristic signature of six mutations in rpoB450, rpoC485, katG315, katG335, rpsL43 and embB497. In conclusion, this study provides a set of three concordant SNPs for the detection and screening of Beijing 1071-32 isolates along with a validated real-time PCR assay easily deployable across multiple settings for the epidemiological tracking of this significant MDR cluster.

Subject terms: Evolution, Genetics, Diseases

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis was initially regarded as a highly homogeneous population, yet, recent data demonstrated that this species is more genetically and functionally diverse than previously appreciated with diverging clinical significance associated with some of its phylogenetic clades, genetic families, or clonal complexes1. Studies carried out in the previously unexplored geographical regions and reanalysis of the available M. tuberculosis strains were able to pinpoint clinically and/or epidemiologically significant genotypes emerging in different world regions. In-depth analysis of such genotypes allows for detection of their specific markers associated with pathobiologically significant features such as drug resistance, hypervirulence, or transmissibility.

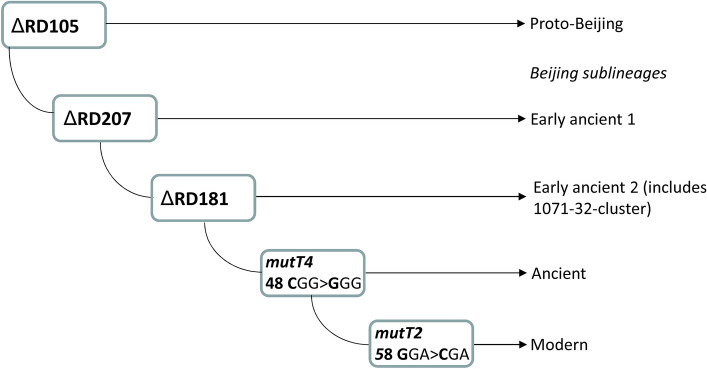

The Beijing genotype remains the most studied genetic family of M. tuberculosis. It can be robustly subdivided into phylogenetically ancient/ancestral and modern sublineages. Initially, subdivision was based on IS6110-RFLP typing, with ancient strains having classical spoligotypes and atypical IS6110-RFLP profiles2. Further studies had identified additional markers, mostly SNP and large sequence polymorphisms, that allowed some degree of discrimination within the ancient sublineage3,4 (Fig. 1). To date, WGS and high-resolution MIRU-VNTR analysis have proven useful for the identification of epidemic clusters but mostly within the globally dispersed modern Beijing sublineage5–9. In contrast, strains of the ancient Beijing sublineage circulate mainly in East Asia (K-strain in Korea is a known example10) and are rarely isolated elsewhere. Consequently, these strains are less studied, their epidemic impact is underestimated and their emergence in locations beyond East Asia is unexpected and needs further attention.

Figure 1.

Simplified evolutionary pathway of the M. tuberculosis Beijing genotype. Digital profile of the 1071-32-cluster: 244231342644425173353923 (loci are listed in clockwise order on chromosome).

Modern Beijing strains are dominant in the former Soviet Union, the most notorious clusters being the Russian epidemic strain B0/W1488 and Central Asia Outbreak clade9. Both genotypes have been described in other countries and in some studies they were shown to circulate outside immigrant communities, highlighting their potential to spread to the autochthonous population11–13. Ancient Beijing strains in Russia were much less studied because they accounted for only 2% of the local M. tuberculosis populations2. Interestingly, a recent study in the Omsk province in Western Siberia detected a relatively elevated 10% prevalence of the ancient Beijing sublineage14. Most of those isolates belonged to the 1071-32-cluster (according to the MIRU-VNTRplus.org MLVA MtbC15-9 classification scheme) and also formed a monophyletic cluster within the WGS-based phylogenetic tree15. All Russian isolates of this cluster (from St. Petersburg, Omsk, and Samara) were multi-drug resistant (MDR) due to the specific signature of six mutations in rpoB, rpoC, katG, rpsL and embB. It was complemented in most isolates with additional mutations in pncA, gyrA, rrs, or eis thus leading to pre-XDR or XDR phenotype. Most of those mutations were high-confidence, high resistance-level mutations according to the WHO guidelines16.

WGS/NGS is becoming less expensive and more available and while NGS technologies are not always accessible especially in remote areas, this could be remedied by centralization of WGS services17. However, it is unrealistic to implement NGS for routine TB diagnostics and surveillance in the high burden countries such as Russia given a large size of the country and 50/100,000 incidence i.e., 72,000 new cases in 2019 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD?locations=RU). This highlights the importance and interest in the development of methods for detection of epidemic clusters, ideally less time-consuming than 24-loci VNTR typing but with an equivalent turn-around time and less expensive than WGS.

Here, we identified in silico the SNP markers specific for the Beijing 1071-32-cluster and developed a real-time PCR-based procedure to reliably detect this genotype. We evaluated the specificity of these SNPs on a geographically and genetically diverse collection of isolates from East Asia and the former Soviet Union in which the Beijing genotype is endemic or epidemic.

Materials and methods

Study collections

The study samples included M. tuberculosis DNA collected between 1996 and 2020 either convenience samples or from prospective or cross-sectional studies. Samples were not biased with regard to drug resistance, comorbidities or other patient related characteristics.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology (protocol 31.2 of February 27, 2017) and St. Petersburg Pasteur Institute (protocol 41 of December 14, 2017).

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from cultured M. tuberculosis isolates using the CTAB-based method18 (Russian isolates from northwestern Russia and Omsk, isolates from Belarus, Kazakhstan, Japan, China, Vietnam, and Brazil), DNA-Sorb-B kit (Interlabservis, Russia) (Russian isolates from Irkutsk, Buryatia, Yakutia), «Express-tub» kit (Syntol, Russia) (Russian isolates from Yekaterinburg and Yamalo-Nenets), incubation at 98ºC and sonication for 15 min (isolates from Greece), three cycles of hot-freeze cell disruption (isolates from Albania), GenoLyse® kit (Hain Lifescience) (isolates from Estonia). One microliter of the DNA extracted using sonication, boiling method or commercial kits and 10–20 ng of DNA extracted using CTAB method was used for PCR.

Spoligotyping and 24 loci MIRU-VNTR typing were performed according to standard protocols19,20.

TB Profiler database (http://tbdr.lshtm.ac.uk/) was used for genotypic detection of drug resistance. MDR, pre-XDR and XDR phenotypes were defined according to the World Health Organization definitions: MDR are strains resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin; XDR—resistant to isoniazid, rifampicin, fluoroquinolone, and a second-line injectable agent; pre-XDR—resistant to isoniazid, rifampicin and either a fluoroquinolone or a second-line injectable agent.

Bioinformatics and phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of the ancient Beijing strains based on the WGS data obtained in our laboratory or retrieved from SRA NCBI, was described previously15 and the list of the accession numbers of the analyzed genomes is provided in the same publication. In brief, short sequencing reads were mapped to the reference genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (NC_000962.3) by using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner v. 0.7.1221. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling was performed by SAMtools v.0.1.1922. Variable call format (vcf) files were annotated by BSATool v.0.123. Graphical presentation of the trees was done using TreeGraph (http://treegraph.bioinfweb.info) and iTOL v3 (http://itol.embl.de). Obtained VCF files were used for analysis. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with quality scores ≥ 20 were used for phylogenetic analysis with IQTREE software (http://www.cibiv.at/software/iqtree) by using ModelFinder (http://www.iqtree.org/ModelFinder) with the GTR2 + FO + G4 substitution model and 1,000 rapid bootstrap replicates. SNPs located in repetitive genome regions and in PE and PPE genes were removed from the analysis due to possible misalignments.

To assess the significance of amino acid substitutions, we used 4 parameters: Tang U-index, Grantham D-distance, BLOSUM62 distance, and Dayhoff log odds. They were calculated using in-house scripts, in particular, the snpMiner2 program24.

Real-time PCR

Three SNPs at genome positions 170505, 451510 and 398918 specific of the Beijing 1071-32 cluster were tested by real-time PCR assays that were run under the same cycling conditions. Oligonucleotide primers and FAM and HEX labeled probes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides primers and labeled probes used for detection of three synonymous SNPs specific of the Beijing 1071-32-cluster.

| Gene, codon | Position in gene | Position in genome | Primer, probe, and sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rv0144 74GCC/GCT | 222 C>T | 170505 C>T |

170505F 5′-CCAACGGTAGGTACCAAGC 170505R 5′-GCTTCCGAGTCTCATCTGCT 170505C wt 5′-[HEX]GTTCAATGTCGCTCACGGC[C-LNA]G[BHQ1] 170505 T mut 5′-[FAM]GTTCAATGTCGCTCACGGC[T-LNA]G[BHQ1] |

| Rv0373c 98CCG/CCA | 294 G>A | 451510 C>T |

451510F 5′-CGCATCGATGTGACTGCC 451510R 5′-CACGGCTTGTACGTCGTTG 451510G wt 5′-[HEX]GCCTGGCTTGGATGCC[G-LNA]ACA[BHQ1] 451510A mut 5′-[FAM]GCCTGGCTTGGATGCC[A-LNA]ACA[BHQ1] |

| Rv0334 87GCG/GCA | 261 G>A | 398918 G>A |

398918F 5′-GAGTGAACATCAGCTACGC 398918R 5′-GGCCGTAGAAGATGTTGTC 398918G wt 5′-[HEX]TCAGCCTGACGGTCTGGC[G-LNA]CA[BHQ1] 398918A mut 5′-[FAM]TCAGCCTGACGGTCTGGC[A-LNA]CA[BHQ1] |

wt, wild type; mut, mutant; LNA, locked nucleic acid.

PCR mix (25 µl) contained 3 mM MgCl2, 1 unit of hot start Taq DNA polymerase, 200 μM each of dNTP, and primers (8 pmol each) and probes (4 pmol each). RotorGene6000 (Corbette Research) and CFX96 (Biorad) thermal cyclers were used with the following cycling conditions: 95 °C, 10 min; followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C, 30 s; 60 °C, 10 s, 72 °C, 20 s (signal detection at 60 °C at wavelength 510 nm for FAM and 555 nm for HEX). No difference was found between results obtained in different thermal cyclers.

Detection of drug resistance mutations

Six drug resistance mutations were previously shown to be specific for Beijing 1071-32-cluster15: KatG Ser315Thr, KatG Ile335Val, RpoB Ser450Leu, RpoC Asp485Asn, EmbB Gln497Arg, RpsL Lys43Arg. To detect these mutations we used different methods, some of which were previously described, as follows.

Rifoligotyping reverse hybridization assay was used to detect mutations in the rpoB hot-spot region25. Other mutations were detected using allele-specific PCR or PCR–RFLP assays followed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis (Table 2). All methods were initially tested and optimized using DNA samples of Beijing 1071-32 isolates with available WGS data and H37Rv as wild type control.

Table 2.

Molecular assays used for detection of six drug resistance/compensatory mutations specific of the Beijing 1071-32-cluster.

| Gene | Genome position | Method of detection | Primers and RE (in case of PCR–RFLP) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KatG 315 AGC/ACC | 2155168 | PCR–RFLP |

Fw 5′-GCAGATGGGGCTGATCTACG Rev 5′-AACGGGTCCGGGATGGTG RE: MspI |

26 |

| KatG 335 ATC/GTC | 2155109 | PCR–RFLP |

Fw 5′-GCAGATGGGGCTGATCTACG Rev 5′-AACGGGTCCGGGATGGTG RE: AvaII |

This study |

| RpoB 450 TCG/TTG | 761155 | Rifoligotyping |

Fw 5′-GTCGCCGCGATCAAGGA Rev 5'-[Biotin]ACGTCGCGGACCTCCA |

25 |

| RpoC 485 GAT/AAT | 764822 | Allele-specific PCR |

Fw 5′-CTGGAGCTGTTCAAGCCGTTC RevWT 5′-CGATGACCTCTTCGAGCACAGC RevMut 5′-CGATGACCTCTTCGAGCACAGC |

This study |

| EmbB 497 CAG/CGG | 4248003 | PCR–RFLP |

Fw 5′-TGTGCAGCCCACCGGCCTGA Rev 5′-TGTGCAGCCCACCGGCCTGA RE: MspI |

This study |

| RpsL L43 AAG/AGG | 781687 | PCR–RFLP |

Fw 5'-CAGCCCGCAGCGTCGTGGTG Rev 5'-GCTGCGTGCCTGTTTGCGGTTCTT RE: MboII |

This study |

RE, restriction endonuclease.

Allele-specific PCR was used to specifically detect rpoC 485 GAT>AAT mutation; primers were selected using WASP online tool at https://bioinfo.biotec.or.th/WASP/home. Both allele-specific primers contained mismatch at − 1 position at 3′-end to increase instability during annealing and increase specificity. Two separate PCR reactions were performed for each strain at the same PCR conditions and using the same forward primer and allele-specific mutant primers. PCR products for both reactions are identical 130 bp and are subjected to gel-electrophoresis in adjacent lanes for each strain for easier comparison.

katG315 AGC>ACC mutation was detected using PCR–RFLP assay as described26. This mutation creates an additional site for MspI and the main digestion bands have a size of 153 and 132 bp in the case of wild type and mutant alleles, respectively.

katG335 ATC>GTC mutation was detected using PCR–RFLP assay. This mutation creates an additional site for AvaII and the main digestion products have sizes 378 and 285 bp in the case of wild type and mutant alleles, respectively.

rpsL43 AAG>AGG was detected using PCR–RFLP assay. This mutation occurs within the only MboII site in the PCR product in case of the wild type allele. The main MboII digestion products are 210 and 60 bp in case of wild type allele and 270 bp in case of mutation.

embB497 CAG>CGG was detected using PCR–RFLP assay. This mutation creates an additional site for MspI and the main digestion products have sizes 170 and 135 bp in the case of wild type and mutant alleles, respectively.

Results

Identification of Beijing 1071-32-cluster specific SNPs

Phylogenetic analysis of 184 WGS samples of ancient Beijing sublineages demonstrated that all isolates with Beijing 1071-32 VNTR profile were also grouped within a monophyletic branch on the WGS tree15 (Fig. S1). This branch included only Russian isolates (Omsk region in Siberia, St. Petersburg in Northwestern Russia, Samara in Central Russia). For the purposes of the present study, we reanalyzed the genome variation data underlying this tree and identified SNPs that were specific for this branch that we termed “Beijing 1071-32-cluster”, i.e. 1071-32 and its single/double locus variants (Fig. S2). In total, 121 SNPs were identified: 15 in intergenic regions and 106 in the coding sequences. These latter included 56 nonsynonymous (2 nonsense and 54 missense) and 39 synonymous mutations. In silico based assessment of the significance of the amino acid substitutions revealed three synonymous mutations in Rv0144, Rv0373c, and Rv0334 with null significance score by all four tested parameters (Tang U-index, Grantham D-distance, BLOSUM62 distance, and Dayhoff log odds). We used these three SNPs for the development of real-time PCR assays (Table 1). The synonymous SNPs reflect a neutral evolution non-influenced by selection pressure and unlikely to independently occur in different and unrelated phylogenetic groups. Moreover, Rv0334 codes for a thymidylyltransferase from the lipopolysaccharide biosynthetic pathway deemed essential by analysis of saturated Himar1 transposon libraries27 and therefore unlikely to be affected by genomic deletion events.

We evaluated in silico the specificity of these SNPs by search in the M. tuberculosis genome diversity GMTV database28. They were not detected in the non-Beijing isolates and were detected only in 6 Beijing isolates from Samara, Central Russia included in the above WGS analysis i.e. isolates of this Beijing 1071-32-cluster itself.

Real-time PCR: optimization, validation and screening

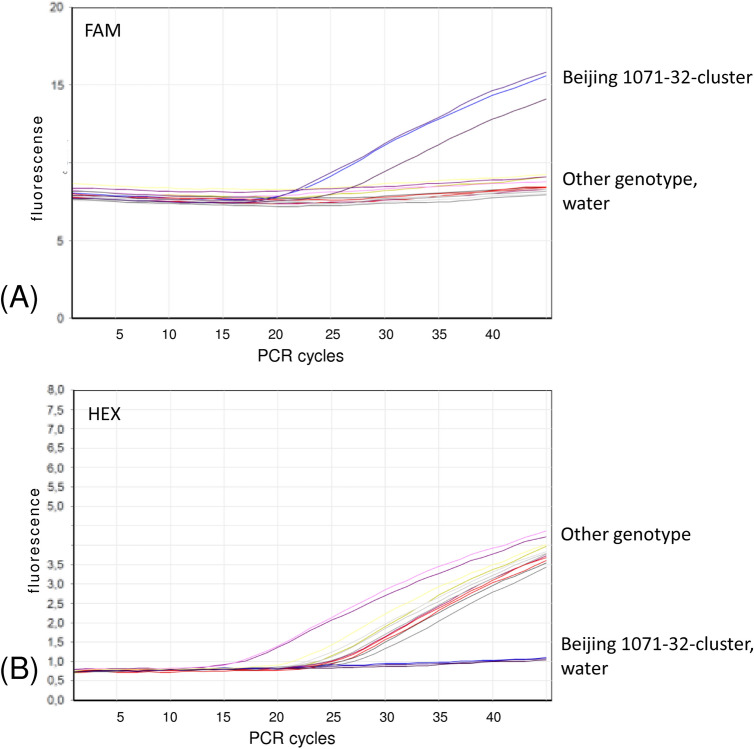

Three SNPs were targeted by three separate real-time PCR reactions run simultaneously under the same cycling conditions. Initial optimization was performed with DNA samples with available WGS and VNTR data that represented different VNTR clusters of the Beijing genotype and H37Rv reference strain. Clear discrimination between wild type and mutant alleles was observed for all three tested SNPs (see an example for one SNP in Fig. 2). The DNA used for analysis was extracted from cultured bacteria using different methods but this did not affect the performance of the assay.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence curves of a real-time PCR assay targeting Rv0144 SNP. (A) Beijing 1071-32 specific signal (FAM channel, 510 nm); (B) other genotype-specific signal (HEX channel, 555 nm). Water serves as negative control sample.

The three RT-PCR assays were further applied to the 675 Beijing genotype isolates that represented different Beijing sublineages and had different VNTR profiles. These validation collections included isolates from Russia (n = 378), Kazakhstan (n = 109), China (n = 45), Vietnam (n = 37), Japan (n = 71), Albania (n = 5), Greece (n = 19), Brazil (n = 11). This analysis demonstrated that all 48 Beijing 1071-32-cluster isolates had these three mutations. In contrast, all other 627 isolates with other VNTR profiles had wild type alleles in these genome positions. Thus, this method has 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity to detect Beijing 1071-32-cluster.

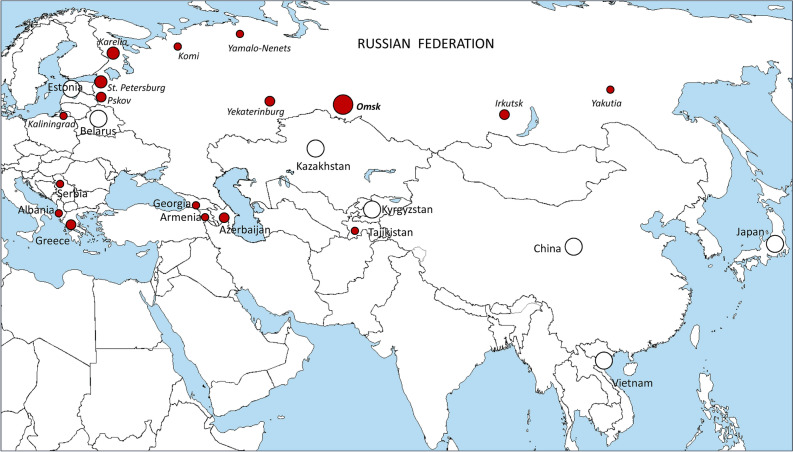

We further applied these RT-PCR assays to screen all available DNA collections from Russian regions and other countries. Results summarizing the above validation and screening analysis based on the total of 2375 isolates are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

Table 3.

Detection of the Beijing 1071-32-cluster by the developed PCR assay in local collections.

| Country, region, years | Beijing | Beijing 1071-32 |

|---|---|---|

| Russia, Northwest, CПб 1996–2020 | 835 | 22 |

| Russia, Northwest, Karelia, 2014 | 43 | 6 |

| Russia, Northwest, Pskov, 2015, 2018 | 85 | 3 |

| Russia, Northwest, Kaliningrad, 2015 | 46 | 1 |

| Russia, Northwest, Komi, 2017 | 73 | 1 |

| Russia, Northwest, Vologda, 2018 | 51 | 0 |

| Russia, Northwest, Murmansk, 2017 | 32 | 0 |

| Russia. Siberia, Omsk, 2008–2019 | 372 | 37 |

| Russia, Siberia, Irkutsk, 2014–2015 | 147 | 2 |

| Russia, Ural, Yamalo-Nenets, 2017 | 101 | 1 |

| Russia, Ural, Yekaterinburg, 2019–2020 | 85 | 2 |

| Russia, Far East, Yakutia, 2012 | 67 | 1 |

| Albania, 2007–2011 | 5 | 1 |

| Greece, 2008–2011 | 19 | 3 |

| Estonia, 1999 and 2014 | 91 | 0 |

| Belarus, 2004 | 50 | 0 |

| Kazakhstan, 2010 | 109 | 0 |

| China, 2004 | 45 | 0 |

| Vietnam, 2005 | 37 | 0 |

| Japan, 2003–2005 | 71 | 0 |

| Brazil, 2001–2007 | 11 | 0 |

| Total | 2375 | 80 |

Beijing genotype was detected using spoligotyping, or PCR targeting dnaA-dnaN::IS6110 (Mokrousov et al., 2014) or based on VNTR-clustering. Beijing 1071-32-cluster was detected by real-time PCR analysis of SNPs in Rv0144, Rv0373c, and Rv0334 as described in this study.

Geographic locations are shown on Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the Beijing 1071-32-cluster isolates identified in this study. Circle size roughly correlates with the proportion of identified isolates of this cluster (the smallest dots depict single isolates). Absence of these isolates in the local populations is shown by white circle. No Beijing 1071-312-cluster isolates were detected in Brazil (not shown on the map), Free map: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_large_blank_world_map_with_oceans_marked_in_blue.PNG.

Drug resistance mutational signature in the Beijing 1071-32-cluster

Under the previous WGS analysis, the isolates of the Beijing 1071-32-cluster were shown to have multiple mutations in drug resistance genes and, in particular, were characterized by the specific signature of 6 mutations katG 315AGC/ACC, katG 335ATC/GTC, rpoB 450TCG/TTG, rpoC 485GAT/AAT, embB 497CAG/CGG, rpsL 43AAG/AGG15.

We screened the above-identified Beijing 1071-32-cluster isolates for the presence of these mutations. As a result, all Beijing 1071-32-cluster isolates harbored these six mutations.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to develop a practical approach to robust detection and prospective surveillance of the MDR/pre-XDR cluster within M. tuberculosis Beijing genotype emerging in Russia14. WGS-based analysis of the Russian and global datasets demonstrated that this Beijing 1071-32 cluster also presents a separate branch on the WGS-based tree15. In terms of large-scale sublineages, this cluster belongs to the early ancient Beijing sublineage characterized by deleted RD181 and wild type mutT2-58 and mutT4-48 codons (Fig. 1). In terms of drug resistance, it bears a characteristic signature of six drug resistance mutations associated with resistance to the four first-line drugs15. Additional mutations in different genes were also present in most isolates of that branch and were associated with resistance to one or more second-line drugs, leading to pre-XDR or XDR genotype (Fig. S2). Most noteworthy and alarmingly, this cluster included only MDR isolates. For example, even the notorious Russian epidemic B0/W148-cluster reportedly included not only MDR but polyresistant isolates resistant to STR and RIF or INH8,29,30.

On the whole, based on the VNTR analysis, Beijing 1071-32-cluster isolates were mostly detected in Russia with clearly increasing prevalence in Omsk, Siberia but these isolates were also present in other Russian regions and FSU countries in Central Asia and Transcaucasia (Fig. 3). In the large Beijing genotype VNTR dataset31, this VNTR profile 1071-32 was identified in the isolates from Armenia (1 isolate) and Abkhazia (5 isolates). When we additionally searched for the three neutral SNPs and six resistance mutations in the large Beijing genotype WGS dataset previously compiled and described in Perdigão et al.13, 5 more isolates that harbored these mutations were detected. They originated from the FSU countries Azerbaijan (n = 3), Georgia (n = 1) and Tajikistan (n = 1).

Outside FSU, the Beijing 1071-32 isolates were described in Serbia31, Albania32 and Greece33. These are Balkan countries but whether this fact reflects an already local circulation of this strain rather than independent importations from FSU is presently unknown. DNA from Albania and Greece were available for this study and we confirmed that they harbored all 9 targeted mutations i.e., 3 neutral SNPs and 6 resistance mutations. The three isolates from Greece were one from an immigrant from Georgia (FSU) and the remainder two from local Greek patients33. Moreover, Beijing genotype is extremely rare in Albania32 and it was previously speculated that these isolates in Albania could be linked to neighboring Greece. A large European multicenter study of drug resistant TB in the EU ten years ago identified the Beijing 1071-32 isolates and designated them as European resistant cluster ECDC_1034. This additionally highlights the presence of Beijing 1071-32 MDR strains in the EU and, given its association with MDR-TB, the relevance of their tracing on a more global scale not limited to Russia and other FSU countries.

Re-analysis of the different typing data available in our laboratory revealed that VNTR 1071-32 profile was detected in Russian strains isolated in 1996–1999 and these strains had a characteristic IS6110-RFLP profile designated as P0 in the in-house database29 (Fig. S3). Although the former gold standard IS6110-RFLP typing is almost never used anymore, this knowledge may be helpful to trace these isolates in the historical collections with IS6110-RFLP profiles available, e.g. RIVM database (Bilthoven, The Netherlands) or PHRI database (New Jersey, USA), thereby providing backward compatibility with more modern typing methods and WGS. We have also noticed that all Beijing 1071-32 isolates had 1 copy in the MIRU10 locus. This marker may serve for preliminary detection of these isolates among those assigned to the ancient sublineage of the Beijing genotype.

A strategy to target a limited number of SNPs (at least two) was recommended and applied to identify specific strains or clones by PCR based assays11,35–37 which definitely increases the robustness of identification. Thus, application of the entire set of the three targeted SNPs can be seen as the most robust method to detect the Beijing 1071-32-cluster. Nonetheless, detection of particular clusters/genotypes based on use of a single marker is an acceptable and parsimonious approach, provided that such marker was proven specific and sensitive in the validation studies and this concerns both detection of the particular clusters and families and the development of the SNP-barcode system6,9,38,39. In this view, since analysis of the three SNPs showed completely concordant results, testing of any of them appears the most practical and time-saving approach to trace this clinically significant MDR Beijing 1071-32-cluster.

Enigmatically, no fully susceptible or mono/polyresistant strains of this MDR cluster were identified yet, and circumstances of its origin remain unknown. Given that only 13 isolates with NGS data from three locations in Russia were analyzed in our previous paper15, we could not rule out that isolates with partial resistance profile could be identified in the large and geographically diverse collection in this study. However, no such isolates were detected and the fact that all geographically diverse isolates of this cluster bear the same 6–mutation drug resistance signature is remarkable. This variant included only MDR isolates and this finding favors the hypothesis of dissemination exclusively driven by primary resistance, rather than independent acquisition of resistances.

A Russian origin of this cluster is the most plausible scenario since it includes isolates from remote parts of Russia and some of the analyzed local collections in this study date back to 1996 (St. Petersburg). All identified strains of Beijing 1071-32, regardless of their origin, had all 6 resistance mutations. Given the geographic diversity of the isolates, this probably reflects the distant time of origin of this resistance mutation signature. Phylogenomic analysis suggested an origin of this Russian resistant cluster in the 1970s15 when RIF was first included in anti-TB chemotherapy40. This scenario finds parallel situations across Portugal and South Africa where M/XDR-TB endemic strains of the LAM lineage (e.g. Lisboa3 or KZN, respectively) are predicted to evolve to MDR following the introduction of RIF41,42.

The assay showed a good performance with diluted DNA extracted using simplified boiling procedure and we believe it may also work with DNA extracted from clinical samples using commercial kits. Such rapid detection would be especially useful also to reliably predict the MDR pattern since all isolates of this cluster were shown to be quadruple resistant.

In conclusion, this study provides a set of three concordant SNPs for the detection and screening of Beijing 1071-32 isolates along with a validated real-time PCR assay easily deployable across multiple settings for the epidemiological tracking of this important MDR cluster. Application of the entire set of the three targeted SNPs can be seen as the most robust method to detect the Beijing 1071-32-cluster. However, since analysis of these three SNPs showed concordant results, testing of any of them appears the practical and time-saving approach to trace this clinically significant emerging cluster. This assay may be especially useful in high MDR-TB burden and/or resource-limited countries of the former Soviet Union and in many world regions that receive migration flows from the FSU countries.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Russian Science Foundation (Grant 19-14-00013).

Abbreviations

- MDR

Multidrug resistance

- XDR

Extensive drug resistance

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- MIRU

Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units

- VNTR

Variable number of tandem repeats

Author contributions

I.M. designed the experiment, conducted data analysis and wrote the main manuscript text. A.V., A.G., S.Z., T.U., S.T., P.S. conducted genotyping. V.S., O.O., P.K., J.P. conducted genome analysis and oligonucleotide probe selection. P.I., W.W.J., D.P., O.P., N.R., A.S., Y.S., N.S., N.V., I.Y., D.V., V.Z. cultivated mycobacteria and performed drug susceptibility testing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, I.M., upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-00890-7.

References

- 1.Coscolla M, Gagneux S. Consequences of genomic diversity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol. 2014;26:431–444. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokrousov I, et al. Phylogenetic reconstruction within Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype in northwestern Russia. Res. Microbiol. 2002;153:629–637. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(02)01374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebrahimi-Rad M, et al. Mutations in putative mutator genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains of the W-Beijing family. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9:838–845. doi: 10.3201/eid0907.020803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kremer K, et al. Definition of the Beijing/W lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on the basis of genetic markers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:4040–4049. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4040-4049.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bifani PJ, Mathema B, Kurepina NE, Kreiswirth BN. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millán-Lou MI, et al. Rapid test for identification of a highly transmissible Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing strain of sub-Saharan origin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:516–518. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06314-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schürch AC, et al. Mutations in the regulatory network underlie the recent clonal expansion of a dominant subclone of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokrousov I. Insights into the origin, emergence, and current spread of a successful Russian clone of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013;26:342–360. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00087-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shitikov E, et al. Simple assay for detection of the central Asia outbreak clade of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57:e00215–e219. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00215-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hur YG, et al. Host immune responses to antigens derived from a predominant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. 2016;73:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez-Lago L, et al. Urgent implementation in a hospital setting of a strategy to rule out secondary cases caused by imported extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains at diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54:2969–2974. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01718-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghebremichael S, et al. Drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis of the Beijing genotype does not spread in Sweden. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perdigão J, et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis of the Beijing lineage in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau: a snapshot of moving clones by whole-genome sequencing. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2020;9:1342–1353. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1774425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mokrousov I, et al. Early ancient sublineages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype: unexpected clues from phylogenomics of the pathogen and human history. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25(1039):e1–1039.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mokrousov I, et al. Genomic signatures of drug resistance in highly resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains of the early ancient sublineage of Beijing genotype in Russia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;56:106036. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organisation . The Use of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies for Detection of Mutations Associated with Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex: Technical Guide. World Health Organisation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikolayevskyy V, et al. Role and value of whole genome sequencing in studying tuberculosis transmission. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:1377–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Embden JDA, et al. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: Recommendations for a standardized methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokrousov I, Rastogi N. Spacer-based macroarrays for CRISPR genotyping. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1311:111–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2687-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Supply P, et al. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:4498–4510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinkov, V. vsink/bsatool: First beta pre-release (Version 0.1). 10.5281/zenodo.3352204 (2019)

- 24.Sinkov, V., snpMiner2: vcf files annotation tool. https://github.com/vsink/snpminer2 (2016)

- 25.Morcillo N, et al. A low cost, home-made, reverse-line blot hybridisation assay for rapid detection of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2002;6:959–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mokrousov I, et al. High prevalence of KatG Ser315Thr substitution among isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from northwestern Russia, 1996 to 2001. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1417–1424. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1417-1424.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeJesus MA, et al. Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. MBio. 2017;8:e0213316. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02133-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chernyaeva EN, et al. Genome-wide Mycobacterium tuberculosis variation (GMTV) database: A new tool for integrating sequence variations and epidemiology. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narvskaya O, Mokrousov I, Otten T, Vishnevsky B. Molecular markers: application for studies of Mycobacterium tuberculosis population in Russia. In: InL Read MM, editor. Trends in DNA Fingerprinting Research. Nova Science Publishers; 2005. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vyazovaya A, et al. Increased transmissibility of Russian successful strain Beijing B0/W148 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Indirect clues from history and demographics. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2020;122:101937. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2020.101937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merker M, et al. Evolutionary history and global spread of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing lineage. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:242–249. doi: 10.1038/ng.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tafaj S, et al. Peculiar features of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis population structure in Albania. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;78:104136. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ioannidis P, et al. Multidrug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Greece: predominance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes endemic in the Former Soviet Union countries. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017;23:1002–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Beer JL, et al. Molecular surveillance of multi- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis transmission in the European Union from 2003 to 2011. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20742. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.11.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stucki D, et al. Tracking a tuberculosis outbreak over 21 years: strain-specific single-nucleotide polymorphism typing combined with targeted whole-genome sequencing. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;211:1306–1316. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genestet C, et al. Expanded tracking of a Beijing Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain involved in an outbreak in France. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021;17:102167. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martínez-Lirola M, et al. Integrative transnational analysis to dissect tuberculosis transmission events along the migratory route from Africa to Europe. J. Travel Med. 2021;28:taab054. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taab054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homolka S, et al. High resolution discrimination of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains based on single nucleotide polymorphisms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Napier G, et al. Robust barcoding and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lineages for epidemiological and clinical studies. Genome Med. 2020;12:114. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00817-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iseman MD. Tuberculosis therapy: Past, present and future. Eur. Respir. 2002;36:87s–94s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00309102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perdigão J, et al. Using genomics to understand the origin and dispersion of multidrug and extensively drug resistant tuberculosis in Portugal. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:2600. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59558-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen KA, et al. Evolution of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis over four decades: Whole genome sequencing and dating analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from KwaZulu-Natal. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, I.M., upon request.