Abstract

The mosquito Aedes aegypti is the major vector of arboviruses like dengue, Zika and chikungunya viruses. Attempts to reduce arboviruses emergence focusing on Ae. aegypti control has proven challenging due to the increase of insecticide resistances. An emerging strategy which consists of releasing Ae. aegypti artificially infected with Wolbachia in natural mosquito populations is currently being developed. The monitoring of Wolbachia-positive Ae. aegypti in the field is performed in order to ensure the program effectiveness. Here, the reliability of the Matrix‑Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization‑Time Of Flight (MALDI‑TOF) coupled with the machine learning methods like Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to detect Wolbachia in field Ae. aegypti was assessed for the first time. For this purpose, laboratory reared and field Ae. aegypti were analyzed. The results showed that the CNN recognized Ae. aegypti spectral patterns associated with Wolbachia-infection. The MALDI-TOF coupled with the CNN (sensitivity = 93%, specificity = 99%, accuracy = 97%) was more efficient than the loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), and as efficient as qPCR for Wolbachia detection. It therefore represents an interesting method to evaluate the prevalence of Wolbachia in field Ae. aegypti mosquitoes.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Bioinformatics, Genetic techniques, Mass spectrometry

Introduction

Dengue, Zika and chikungunya diseases are globally emerging as a major public health problem in the world. These diseases attracted interest in recent years due to their increasing incidence and their expanding geographical range. Dengue fever is endemic in several countries with 390 million infections estimated per year1. Zika and chikungunya outbreaks also affected several regions and were responsible for high rates of morbidity and mortality2–4.

These diseases are caused by arboviruses that are transmitted to humans by vector mosquitoes, which one of the most widespread is Aedes aegypti. To date, no specific antiviral treatments are available. In addition, no vaccines for Zika and chikungunya are commercially available and the recently licensed dengue vaccine has limitations for its uses 5,6. Efforts to reduce the dengue, Zika and chikungunya incidence therefore rely on Ae. aegypti control. As mosquito control strategies are weakened due to the increase of insecticide resistances, the implementation of alternative and efficient strategies for arboviruses control are required7.

Recently, biocontrol strategy using Wolbachia, an endosymbiotic bacterium, was developed by various research groups8–10. This strategy is based on the ability of Wolbachia to reduce viral replication in Ae. aegypti and consists of releasing mosquitoes artificially infected with Wolbachia in natural Ae. aegypti populations. The World Mosquito Program (WMP; https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/) has implemented this strategy in several countries11–14, including New Caledonia (NC)15, which had released mosquitoes carrying Wolbachia across the main city of Noumea since 2019. Efficiency of this strategy relies on several features of the bacterium including: (1) maternal-inheritance infections resulting in Wolbachia maintain in progeny, (2) cytoplasmic incompatibility mechanism which contributes to uninfected mosquito population reduction and (3) significant inhibition of arboviruses transmission16.

However, for effective arboviruses control, Wolbachia infections should remain at high frequencies in Ae. aegypti populations17. Thus, the monitoring of infected Ae. aegypti through diagnostic testing remains an ongoing requirement to ensure the proper implementation and the effectiveness of the program.

In NC, two methods are currently used to diagnose Wolbachia infection in Ae. aegypti: the TaqMan™ quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) and the LAMP assay. The qPCR remains the reference method18, this technic has the advantage of being sensitive and specific. Furthermore, it allows simultaneously: (1) Ae. aegypti species verification, (2) Wolbachia infection detection and (3) Wolbachia density quantification19. However, no information concerning the mosquito species is obtain in situations where Ae. aegypti internal control is not amplified (i.e., specific primers). In addition, the method is expensive and requires technical expertise.

The LAMP technique was described as suitable for high throughput application due to its good sensitivity and specificity18,20. Compared to qPCR, the result interpretation is more accessible, and the technique allowed a rapid screening of samples. Nevertheless, the main disadvantage of LAMP method is the use of a single target nucleic acid test, allowing only the detection of Wolbachia. In some situations, especially when samples are degraded by the trapping method, a confusion with another Aedes species can occur at the identification step, this can lead to a false-negative interpretation and an underestimation of the Wolbachia frequency.

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has recently emerged for identification tool in medical entomology using mass spectra databases. This technique allows simultaneous arthropod species identification and pathogens detection in a single experiment21–23. In 2015, Yssouf et al. showed the ability of MALDI-TOF MS to identify the tick species and to detect the presence of Rickettsia pathogen, an intracytoplasmic bacterium, in a single assay24. In addition, in terms of required expenses, MALDI-TOF MS is much cheaper than the qPCR and LAMP techniques.

Current advances in machine learning approaches could complement and enhance performance of the MALDI-TOF MS to analyze mosquito spectra. For example, it was used to recognize MALDI-TOF MS spectral patterns associated with Anopheles ages, blood-feeding and Plasmodium infection25. Machine learning methods is a domain includes all supervise classification methods. Particularly, we use deep learning method like convolutional neural network (CNN) for field-mosquitoes recognition which is a method based on neural network. CNN26,27 is an architecture of artificial neural network based on multilayers perceptron. These are usually fully connected neural networks. Each neuron of a layer is connected to all neurons of the next layer.

To our knowledge, no studies have investigated CNN application on Wolbachia detection in mosquitoes. Therefore, the aim of this work was to investigate the use of MALDI-TOF MS and the CNN for Wolbachia detection, in the context of implementing an arbovirus control strategy based on the use of this endosymbiotic bacterium. Our ultimate goal was to develop this tool for a rapid and reliable monitoring of Wolbachia infection rate in Ae. aegypti collected from the field.

Methods

Biological material

During this study, laboratory-reared Ae. aegypti were used, including mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia (wMel-strain) and uninfected specimens (Wild Type-strain, or WT). They were raised in insectarium until adult stage, with a temperature of 28 °C ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 80% ± 10%. Adult mosquitoes were subsequently harvested.

In addition, males and females Ae. aegypti collected from the field were also used during this study. Field sampling was conducted in Noumea, NC, from December 2019 to April 2020 (Supplementary Table S1) using BG-sentinel® traps (Biogents, Regensburg, Germany). This sampling was assessed during the first phase of releases in Noumea (i.e., September 2019 to June 2020). A maximum trapping duration of 24 h was set to avoid mosquito proteins degradation as previously described28.

All mosquitoes were killed by freezing at − 20 °C and were morphologically identified to the species level using morphological keys29–32. Then, Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (males and non-blood fed females) were dissected into two body parts: (1) head and thorax (without legs and wings), and (2) abdomen, then preserved at − 80 °C between 6 and 72 days before MALDI-TOF analyses. Preservation at − 80 °C prevents protein degradation and guarantees good mass spectra acquisition even after long storage durations28.

qPCR and LAMP analysis

DNA extracts was carried out, using abdomen, for both laboratory and field mosquitoes. Extraction was performed using DNA blood and tissues kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

DNA extracted was subsequently amplified by multiplex qPCR using specific primers targeting Ae. aegypti house-keeping Rps17 and Wolbachia specific wsp genes, as previously described18. Briefly, qPCR conditions were: 0,25 µM each of forward and reverse primers, 0,1 µM each of probes, 1X Lightcycler 480 Probes Master reaction mix, 1 µL of target DNA in a total reaction volume of 10 µl. Thermal cycling was performed using Roche LightCycler 480 (Roche Life Science, USA), with 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min for pre-incubation, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 1 s for amplification followed by a final cooling step of 40 °C for 10 s18. In addition, Wolbachia density in mosquitoes, which are an indication of the ratio of Wolbachia DNA relative to Ae. aegypti DNA in each mosquito, were calculated using relative quantification algorithm in the LightCycler 480 software19.

For each field-mosquito, extracted DNA were also subjected to LAMP assay. For this experiment, three pairs of primers were used as described by Gonçalves et al.18. Samples were amplified at 65 °C for 30 min and held at 12 °C until scoring18. LAMP technic provides a drop of pH when DNA amplification occurs, modifying the color of the mix: pink indicates negative, orange indicates equivocal and yellow indicates positive sample. Results were interpreted by direct observation and photos were taken with a tablet computer for data storage.

Protein extraction protocol

For each mosquito, protein extraction was performed using head and thorax according to the protocol previously published28. Abdomen was excluded from analysis in order to increase the reproducibility and quality of spectra and reduce the bias caused by the midgut microbiota33. Briefly, these were put into individual microtubes and rinsed with 1 mL of 70% ethanol for 60 s, followed by 1 mL of distilled water for 60 s. The remaining water was then eliminated using a micropipette and left to evaporate. Three metal beads, 15 µL of acetonitrile (50%) and 15 µL of formic acid (70%) were subsequently added to the microtube. Each sample was subsequently homogenized (automated method) using a MagnaLyser, version 1.1 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with 3 cycles of 30 s at a frequency of 3000 rpm. After homogenization, 1 µL of sample was deposited directly on a steel MALDI plate (Bruker Daltonics, Wissembourg, France) and allowed to dry before adding another 1 µL of the same sample over the first spot28. To create the reference main spectrum pattern (MSP), a total of 8 spots were spotted of the same sample28. Conversely, each sample intended to be queried against these reference spectra were deposited in duplicate, as suggested by previous work28. Matrix solution was also loaded in duplicate onto each MALDI-TOF plate in order to control matrix quality.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis

For MALDI-TOF MS analysis, 12 independent experiments were realized. For each experiment, the MALDI-TOF plate contained mosquitoes belonging to the two categories, wMel and WT. The mass spectrometer Microflex LT/SH (Bruker, France), with sample throughput of 200 samples per hours, was used for analysis. Measurements were performed with flexControl software, version 3.3 (Bruker) with detection in the linear positive-ion mode at a laser frequency of 60 Hz and laser power between 40 and 50%. Each spectrum obtained, ranging from 2000 to 20,000 Da, corresponds to an accumulation of 240 laser shots from the same spot performed in 6 regions.

During this study, laboratory reared Ae. aegypti were used to create the MSPs. Specifically, a total of 10 MSPs were created, comprising 5 wMel MSPs and 5 WT MSPs (Table 1). The created mass spectra library was evaluated for mosquito species identification and Wolbachia detection during a blind test, using Bruker Daltonics algorithm.

Table 1.

Overview of mosquitoes used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

| MSPs creation | Blind testing [number of spectra obtained] | |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory strain wMel | 5 | 30 [60] |

| Laboratory strain WT | 5 | 30 [60] |

| Field-mosquito wMel | – | 56 [102] |

| Field-mosquito WT | – | 138 [249] |

| Total | 10 | 254 [471] |

For the blind test analysis, laboratory mosquitoes including 30 wMel-strain and 30 WT-strain were analyzed. In addition, 194 mosquitoes from the field were included in analyses (Table 1). For this, the spectra acquired from the duplicate of each sample was compared to the created MSPs. Then, the MALDI Biotyper Compass software version 3.1 (Bruker Daltonics) calculates Log-score value (LSV) ranging from zero to three, reflecting the similarity between sample spectra and MSP. As previously stated, a LSV ≥ 1.8 support the mosquito species identification28,34.

To find biomarkers of Wolbachia infection, all laboratory and field-mosquito spectra were imported into the FlexAnalysis software (Bruker Daltonics). These were visually inspected in order to compare protein profile of the wMel and WT mosquitoes.

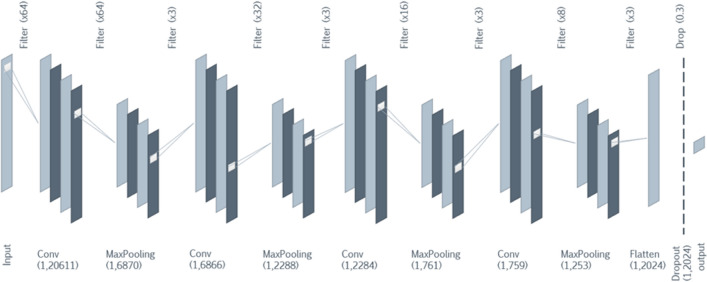

CNN training for mass spectra classification

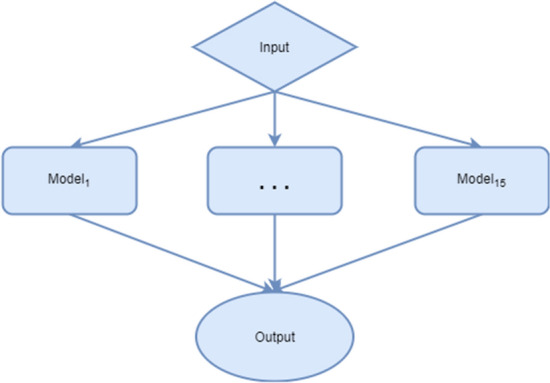

All spectra of field and laboratory mosquitoes generated during this study were exported from the FlexAnalysis software (Bruker Daltonics). The spectra used are the pre-processed spectra (smoothing by baseline subtraction), then they have been normalized so that the values vary in the same ranges. In addition, the architecture only accepts signals of the same size (length). A dimension upscaling of all the spectra was performed by adding null values at the end of each signal for those that had a size smaller than the largest spectra. The architecture26 of the CNN model used is composed of 4 pairs of layers alternating Convolution and Maxpooling layers and ends with a Flattening layer connected to a Fully Connected layer, Dropout, and finally the Output layer (Fig. 1). An ensemble learning architecture was achieved to improve the performance of the classification (Fig. 2). The ensemble learning architecture is composed of 15 CNN as described previously, each and every model has been trained on different parts of the data with random initialization, which help generalize and make robust classification. We store the performance indicators of every model. Then, a voting system is set up based on a newly developed equation which gives the final classification. This process improves the overall performance of the classification.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the convolutional neural network used for Wolbachia detection in Ae. aegypti.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the ensemble learning used during analysis.

Each spectrum acquired from the duplicate of one mosquito, was considered as a single input (considered as data augmentation). For 37 mosquitoes, only one spectrum was obtained from the duplicate. Thus, a total of 471 spectra were included in the analysis. This consisted of 120 spectra of laboratory-mosquitoes and 351 spectra of field-specimens. In order to avoid biases, multiple scenarios have been considered. Firstly, to avoid overfitting and to generalize the model, we use the k-fold cross-validation35,36 technique. This consists in randomly dividing the dataset into k subgroups (here, k = 5). One group (i.e., test dataset) was used for the model validation, while the k − 1 groups (i.e., training dataset) were dedicated to training the model. Then, K-fold results were then averaged to produce a single estimate of the performance indicators (accuracy, precision, recall, etc.). Furthermore, to overcome the unbalanced class problem, an upsampling of the minority classes has been carried out.

Finally, based on the output of the test dataset, we performed a quantitative evaluation of the ensemble learning performance to recognize Ae. aegypti spectral patterns associated with Wolbachia infection. Then, Sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive values (NPV) and classification accuracy were computed.

Feature extraction

The CNN is a deep learning model based on an artificial neural network with several layers connected to each other. Each layer (which operates as a black box) receives and processes information from the previous layer. This information contains the features calculated at each layer that allowed the discrimination of classes. So, each layer improves its learning by refining the features previously calculated. To extract the features, we therefore calculate the frequency of a given peak carried out through the layers (using the feature maps given by the CNN of each layer). Thus, features were extracted in order to identify the spectra region used by CNN to discriminate infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti. The data containing the major mass points within the spectra used by the CNN to discriminate infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti, and their corresponding intensities were exported. This was analyzed with R software (R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Comparison of performances of LAMP, MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling and MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN

The performance of LAMP and MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling to detect Wolbachia in field-mosquitoes was compared to the reference qPCR analysis performance. For this, sensitivity (Se), Specificity (Sp), Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV) and classification accuracy were computed. We also performed a quantitative evaluation of the classification performance of CNN when using MALDI-TOF MS spectra. This was based on the rates of correctly classified spectra in the positive and negative labelled classes, according to the qPCR reference technique.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Mosquito collection authorization was granted by authorities from the South Province of New Caledonia (ordinance No. 1415–2019/ARR/DENV).

Results

Mosquito species confirmation and Wolbachia detection with the reference qPCR method

During this study, the morphological identification of field and laboratory-mosquitoes was confirmed using qPCR technic. The Rps17 gene was correctly amplified for all samples, confirming that they belonged to the Ae. aegypti species.

In addition, Wolbachia screening was realized on the laboratory-strain using qPCR method. The Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia (wMel-strain) showed amplification of the wsp gene. The mean Wolbachia density was of 15 (95% CI 12–19) copies of wMel per copy of the Rps17 gene. Conversely, no amplification of wsp gene was observed for the WT mosquitoes.

A total of 194 Ae. aegypti from the field were analyzed with the qPCR technic. All were positive for Rps17 gene. Results showed 56 Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes. The mean of Wolbachia density was of 30 (95% CI 19–41) copies of wMel per copy of the Rps17 gene. Conversely, qPCR result showed that 138 field-Ae. aegypti were not infected by Wolbachia.

Wolbachia detection with LAMP technic

All mosquitoes from the field were also analyzed using LAMP method. Among the 56 Wolbachia infected mosquitoes (results obtained with the reference qPCR), the bacterium was detected in 45 individuals. Equivocal and negative results were obtained for 4 and 145 mosquitoes, respectively.

MALDI-TOF MS results

During the query of the reference mass spectra library, 98% (n = 60) and 90% (n = 194) of respectively laboratory-reared and field mosquitoes were correctly identified at species level (LSV ≥ 1.8). For Wolbachia detection, we observed mismatches. Indeed, 47% (95% CI 28–66%) and 70% (95% CI 56–81%) of respectively wMel laboratory-reared and field-collected mosquitoes incorrectly matched with WT MSPs. Similarly, 27% (95% CI 12–46%) and 16% (95% CI 10–23%) of respectively WT laboratory-reared and field mosquitoes incorrectly matched with wMel MSPs.

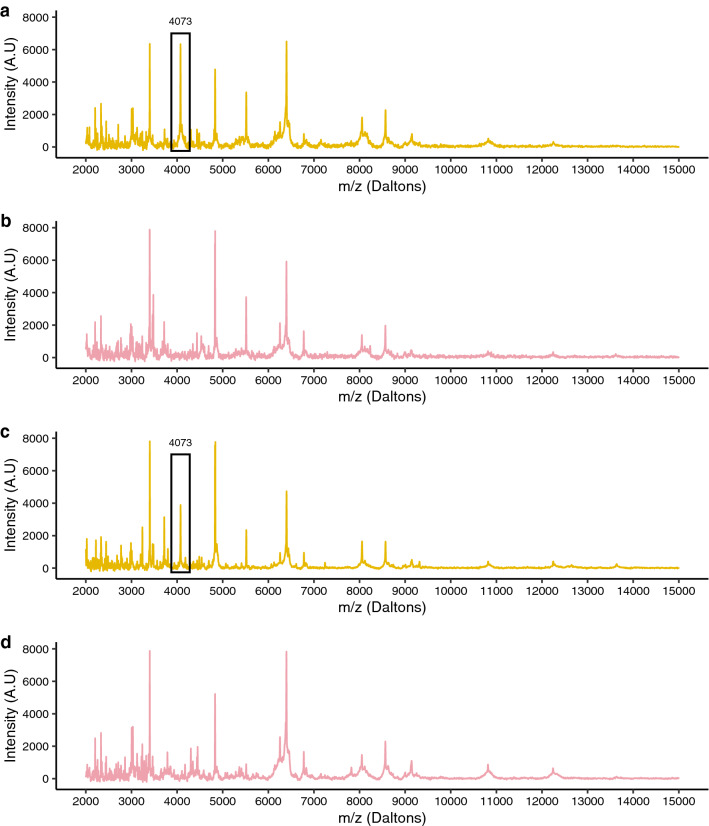

Using protein profiling, a peak at 4073 ± 3 Da and high intensity (i.e., > 2000 a.u) was detected in 100% of wMel laboratory Ae. aegypti spectra. Conversely, this peak was considered as absent in all WT laboratory-mosquito spectra (Fig. 3). When observing the spectra of field-specimens, the peak at 4073 ± 3 Da was also detected in 43 mosquito spectra among the 56 Wolbachia infected field-mosquitoes and was present in the spectrum of one WT-mosquito (qPCR results). This peak was considered as absent in the other 150 field-specimen spectra.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the spectra of Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia and Ae. aegypti uninfected using FlexAnalysis software. (a): spectra of infected Ae. aegypti from the laboratory. (b): spectra of uninfected Ae. aegypti from the laboratory. (c): spectra of infected Ae. aegypti from the field. (d): spectra of uninfected Ae. aegypti from the field. Abbreviations: A.U, arbitrary unity; m/z, mass-to-charge ratio.

Distinction between spectra of Wolbachia infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti with CNN

With the architecture of the proposed CNN model, we first used a dataset of 471 spectra in order to train and validate the model (one or two spectra per specimen, depending on the number of spectra obtained for the two deposits per specimen on the MALDI-TOF plate). For the laboratory-strain, the results showed 55 Wolbachia-infected spectra and 65 uninfected spectra. A discordance between the results within the duplicate was observed for 3 mosquitoes. Regarding the result of field-mosquitoes, 100 infected spectra and 251 uninfected spectra were found. For 6 mosquitoes, a discordance between the results within the duplicate was also observed. Moreover, when using the CNN, the bacterium was detected in 9 of 11 mosquitoes with low Wolbachia densities.

The performance of the CNN to discriminate spectra of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected mosquitoes was also evaluated using laboratory-reared and field specimens. We report the confusion matrices provided by the CNN separately for laboratory-strain and field mosquitoes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Confusion matrices of field and laboratory mosquitoes’ classification with CNN on MALDI-TOF MS spectra.

| Laboratory mosquitoes | Predicted positive | Predicted negative | Field mosquitoes | Predicted positive | Predicted negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Positive | 27 | 3 | Actual Positive | 52 | 4 |

| Actual Negative | 0 | 30 | Actual Negative | 2 | 136 |

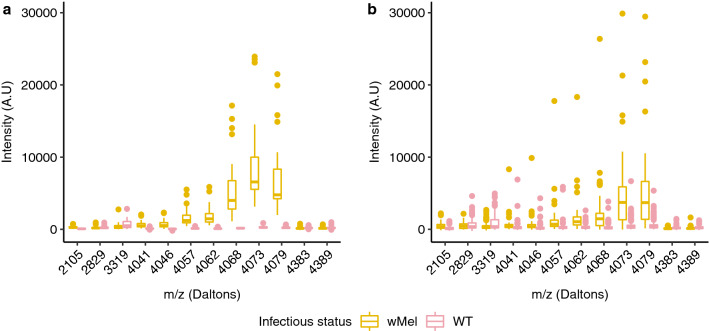

Analysis of Ae. aegypti spectra profiles according to CNN results

For spectra profiling, using the features extracted from the CNN, arbitrary thresholds are defined to help with discrimination. This allows us to make a comparison between the calculation made manually and what the CNN allows us to do automatically. We can see that the CNN finds other possibilities to discriminate between the spectra representing infected or uninfected mosquitoes when the important peaks do not have the same intensity range. This confirms the robustness of the CNN model. Feature extraction allowed to observe a total of 60 mass points (i.e., biomarkers) within the spectra which were over 80% used by the CNN to discriminate the spectra of Wolbachia infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti (Supplementary Fig. S1). The observation of the result showed that the single peak visually observed when using the FlexAnalysis software (Bruker Daltonics) was a set of mass points forming a bell curve around 4073 ± 3 Da. Regarding the spectra areas used at more than 85% by the CNN, a total of 12 mass points within the spectra were used, including 7 points located in the 4073 ± 3 Da region for the laboratory and field mosquito spectra (Fig. 4a,b, respectively).

Figure 4.

Boxplot showing the 12 mass points of distinct m/z (Daltons) considered over 85% by the CNN to discriminate Ae. aegypti infected and uninfected with Wolbachia. (a): results obtained for laboratory-reared mosquitoes (wMel: n = 30; WT: n = 30). (b): results obtained for field mosquitoes (wMel: n = 56; WT: n = 138). The boxplot colors correspond to the infection status of the mosquitoes determined by qPCR (yellow: wMel; pink: WT). Abbreviations: A.U, arbitrary unity; m/z, mass-to-charge ratio.

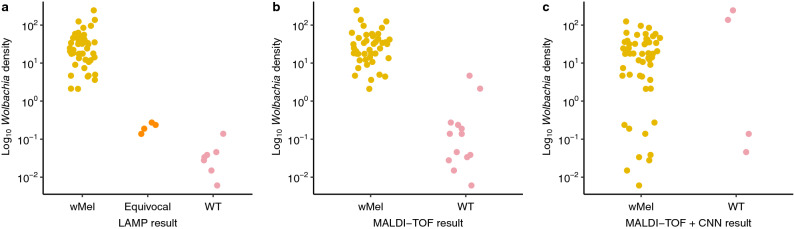

Comparison of performances of LAMP, MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling and MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN

Relative to the qPCR reference method, no LAMP false positive was observed when analyzing field-mosquitoes. Conversely, false negatives results (i.e., equivocal and negatives) were observed for 11 mosquitoes. For these mosquitoes, low wMel densities (i.e., < 1) were found (Fig. 5a). According to these results, a sensitivity of 80% (95% CI 69–90%), a specificity of 100% (95% CI 97–100%) and an accuracy of 94% (95% CI 90–97%) were achieved for LAMP method (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Classification of field wMel Ae. aegypti according to their Wolbachia density by LAMP, MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling, and MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN. (a): results obtained with LAMP assay. (b): results obtained with MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling. (c): results obtained with MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN. Each dot represents one field Ae. aegypti detected as positive for Wolbachia by qPCR (n = 56). Y axis corresponds to the decimal logarithm of Wolbachia density according to the qPCR results. In the X-axis, wMel corresponds to the true positive results, equivocal (only for LAMP) and WT correspond to the false negative results.

Table 3.

Comparison of LAMP, MALDI-TOF MS profiling, and MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN performances when analyzing field-mosquitoes (n = 194).

| Technic | Se [95% CI] | Sp [95% CI] | PPV [95% CI] | NPV [95% CI] | Accuracy [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP | 80% [68–90] | 100% [97–100] | 100% | 93% [88–95] | 94% [90–97] |

| MALDI-TOF | 77% [64–87] | 99% [96–100] | 98% [86–100] | 91% [87–94] | 93% [88—96] |

| CNN on MALDI-TOF | 93% [89–96] | 99% [97–100] | 96% [94–99] | 97% [95–99] | 97% [94–99] |

Abbreviations: Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

The performance indicators were calculated in comparison to the results of the gold standard qPCR technique.

Concerning the MALDI-TOF technic, when we consider the presence of the peak at 4073 ± 3 Da as an indicator of Wolbachia presence in Ae. aegypti, one false positive result was observed for field-mosquitoes, while 13 false negatives were found. With the exception of two specimens, low wMel densities (i.e., < 1) were observed for these false negative specimens (Fig. 5b). With only a visual analysis of the spectra, a sensitivity of 77% (95% CI 64–87%), a specificity of 99% (95% CI 96–100%) and an accuracy of 93% (95% CI 88–96%) were obtained (Table 3).

For the MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN, based on the results obtained for one spectrum per mosquito, two false positive results were observed for field-mosquitoes. In contrast, the number of false negatives was greatly reduced compared to MALDI-TOF alone, with only four false negatives results. Indeed, most mosquitoes with a low density of Wolbachia (i.e., < 1) were better classified by the CNN (Fig. 5c). The result showed a sensitivity of 93% (95% CI 89–96%), a specificity of 99% (95% CI 97–100%) and an accuracy of 97% (95% CI 94–99%).

Discussion

The release of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes artificially infected with the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia in the field is one of the most promising ongoing intervention against arboviruses. The World Health Organization has recently published that this strategy demonstrates public health value against dengue virus37. However, in order to evaluate the effectiveness of this program, the prevalence of Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia must be assessed through screening trapped mosquitoes. In this study, we present the first assessment of the accuracy of the MALDI-TOF MS and artificial intelligence to detect the presence of Wolbachia in field Ae. aegypti.

In Ae. aegypti artificially infected with Wolbachia, the bacterium is localized throughout most tissues such as the fat body, midgut, muscle, nervous tissue and Malpighian tubules38. The bacterium is also present in the salivary glands, which are located at the anterior portion of the thorax, and is more abundant in their ovaries, located in the abdomen9. During this study, the abdomen was not used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis to reduce bias caused by potential traces of blood-meal and microbiota in the spectra34. This part of the body was used for qPCR and LAMP assays, while the head and thorax were tested for MALDI-TOF analysis. In parallel, the legs of these mosquitoes were also tested on MALDI-TOF but did not allow good classification of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected mosquitoes (Raw Data are provided in Supplementary Table S1).

The result of MALDI-TOF analysis showed that the routine analysis, using the MALDI-compass software (Bruker Daltonics), consisting in comparing the mosquito spectra with the reference spectra (i.e., MSPs), did not allow a successful distinction between Wolbachia-infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti. Indeed, mismatches between mosquito’ infectious status were found. Previous work consisting in the detection of filariae in Ae. aegypti has shown a variation of correct identification rates according to the compartment tested when querying of a reference database22. In contrast, other works have shown the 100% reliability of the MALDI-TOF database queries to detect the presence of bacterium such as Rickettsia in tick legs and haemolymph24,39. These contradictory results suggest that care should be taken when using only database query for microorganism detection in arthropods.

The observation of the spectral profile of laboratory reared Ae. aegypti allowed to visually detect a peak at 4073 Da in 100% of wMel mosquitoes, which was absent in WT specimens. When considering this peak as specific biomarker of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, the performance of the MALDI-TOF MS to detect the bacterium in field-mosquitoes was evaluated. Results showed a sensitivity of 77% and most false-negative samples observed had low Wolbachia densities, with the exception of two field Ae. aegypti. These findings highlighted that despite the sensitivity of 77% of the MALDI-TOF MS when using only the FlexAnalysis software, this method allows the detection of Wolbachia in the field-mosquitoes when the density of the bacteria is high (> 1); these mosquitoes could have strong pathogen blocking and could show a complete cytoplasmic incompatibility and maternal transmission7,16,40.

When analysing the MALDI-TOF spectra with the CNN, an improvement of the performance was found. Indeed, the results showed a sensitivity of 93%, a specificity of 99%, and an accuracy of 97%. In addition, among the 11 mosquitoes with low Wolbachia density, 9 mosquitoes were considered as positive with the CNN. It should be noted that mismatches were observed in CNN results between the duplicate of six individuals from the field, regardless of their infectious status (4 WT and 2 wMel-mosquitoes according to qPCR results). Despite this, results demonstrated that the CNN could recognize the spectral pattern of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti, allowing a robust classification according to their infectious status. Similarly, other authors have shown the ability of artificial intelligence to predict Anopheles aging, their blood feeding status and Plasmodium infection when using MALDI-TOF MS spectral profile25. These proofs of concept extend the field of applications of MALDI-TOF MS coupled with artificial intelligence in medical entomology. As performant as the reference qPCR, this technique represents an interesting complementary method for the monitoring of Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia in the field.

Furthermore, the results obtained during the feature extraction showed that the set of mass points forming a bell curve around 4073 Da stood out from the other mass points considered for the classification. These mass points could correspond to Wolbachia-specific proteins. These could also correspond to a response of the mosquitoes to the bacterial infection. Indeed, previous work has shown that some proteins such as defensin A, an antimicrobial peptide could be implicated in dengue virus inhibition when analyzing the haemolymph of transgenic strains of Ae. aegypti41. Interestingly, according to other authors, the estimated mass of defensin A was of 4075 Da42. Thus, this could correspond to the bell curve (i.e., around 4073 Da) considered by the CNN during our study. However, complementary experiments are needed to test this hypothesis.

The performance of MALDI-TOF protein profiling and coupled to CNN to detect Wolbachia in field-mosquitoes was compared to the reference qPCR method. However, as the LAMP technique is currently used to monitor the progress of the wMel Wolbachia establishment in Noumea, NC, we also compared the MALDI-TOF and LAMP performance. Results showed a robustness of the LAMP technique, with a sensitivity of 80% which was similar than the sensitivity of MALDI-TOF protein profiling, but lower than the MALDI-TOF coupled with the CNN. When comparing our results with those from a previously reported assay18, our study showed a lower LAMP sensitivity value. However, in this previous paper, equivocal samples have been excluded from their analysis18. In our case, equivocal mosquitoes were considered as negative samples to allow the comparison of the three techniques. Moreover, we also found that the false-negative and equivocal samples observed during LAMP analysis corresponded to field-specimens with low Wolbachia density. Previous works have shown that the reduction of Wolbachia density in mosquito result in a weakness of cytoplasmic incompatibility and maternal transmission7,40 and potentially reduced arbovirus blockage16. Thus, the LAMP false-negatives and equivocal can be considered as uninfected mosquitoes due to the potential loss of traits necessary for the strategy success.

All these findings suggest that the MALDI-TOF coupled to CNN is reliable for Wolbachia detection in Ae. aegypti from the field. Unlike the LAMP technique, it allows Ae. aegypti species verification. This information on mosquito species is crucial to avoid a false-negative or false-positive interpretation in case of non-Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. Moreover, the cost of reagents and consumables required for MALDI-TOF MS is about ten times cheaper than for qPCR and LAMP (Supplementary Table S2). While the initial cost of the MALDI-TOF instrument is high, the cost savings on reagents can offset the expenditure within a few years. Finally, in our study, with experienced personal, MALDI-TOF MS analysis (starting from protein extraction to spectra acquisition) can be realized in about 2h30min for one plate (i.e., 96 samples), which is shorter than the time required for qPCR and LAMP analysis (more than 6 h and 5 h, respectively, starting from DNA extraction to DNA amplification).

Our overall results also underlined the need to include field-mosquitoes in analysis to ensure the application of this new tool through field studies. Indeed, we found a higher mean of Wolbachia density in field-mosquitoes compared to laboratory strain, but with a higher variability (Supplementary Table S1). Conversely, the variation of intensities of peaks considered by CNN of field-mosquitoes was less important compared to the profile of laboratory mosquitoes. This could be related to the higher variability of field mosquitoes or a slight degradation of proteins due to trapping28.

This study has potential bias and limitations. The possible limitation of this work was the unavailability of information on the identity and functions of the proteins corresponding to the mass points used by the CNN during analysis. However, the distinction between spectra of Wolbachia-infected and uninfected Ae. aegypti was completed despite the non-identification of these peaks. It will be interesting in the future to carry out analysis using high-end mass spectrometers such as LC–MS/MS systems or MALDI-TOF/TOF in order to have more information on the proteins corresponding to these mass points.

In addition, if the features used by the CNN to classification are consistent with a mosquito's response to Wolbachia infection, it is possible that this response changes slightly depending on the genetic background of the mosquito population tested. It would therefore be important to verify the effectiveness of this CNN in another country implementing this strategy.

The current CNN has good results for the classification between Wolbachia-infected and non-infected mosquitoes, but it does not return any information on Wolbachia density. As mentioned above, mosquitoes with a low Wolbachia density (i.e., < 1) lose partially their ability to block viral replication16. In the future, in order to better monitor the implementation of Wolbachia-based strategies with MALDI-TOF, it would be useful to develop a multi-class CNN that would allow the distinction between uninfected, low Wolbachia density and high Wolbachia density mosquitoes.

Finally, as previously shown, a trapping duration of more than 24 h could lead to protein degradation and alter the MALDI-TOF results28. The daily sampling of traps in the field represents a particular challenge for the use of this tool to detect Wolbachia in field Ae. aegypti adults. To circumvent this limitation, Wolbachia detection could be assessed using eggs or larvae mosquitoes collected by ovitraps or in their breeding site. In the future, the accuracy of MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN for Wolbachia detection in larvae mosquitoes should be therefore tested.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the MALDI-TOF MS coupled to CNN is a reliable tool for the field-monitoring of Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia. It allows detection of the bacterium, with high sensitivity and specificity. The use of artificial intelligence in MALDI-TOF MS spectra analysis is an emerging approach in medical entomology. It will be interesting to apply this tool in other entomological fields such as the pathogen detection in arthropod vectors or determination of the age structure of field-mosquito population.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Direction des Affaires Sanitaires et Sociales de la Nouvelle-Calédonie and the Mairie de Nouméa for their contribution during mosquito sampling. We also thank to the University of Monash and the WMP for providing LAMP protocol and reagents. We are grateful to Thomas Crossay for the conversation about data analysis. We thank to Morgane Pol for the English proofreading.

Author contributions

A.R., V.R., M.D.R., N.S.F. and N.P. designed the study. A.R. and V.B. collected mosquitoes. A.R., V.B., M.K., M.M. and J.C. performed the experiments. A.R., C.C., V.B. and N.P. analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The project leading to this publication received funding from the French Fund for Economic, Social, Cultural and Scientific cooperation in the Pacific (“Pacific Fund”) and the Institut Pasteur of New Caledonia. AR obtained a scholarship from the Institut Pasteur International Network (Bourse Calmette & Yersin).

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-00888-1.

References

- 1.WHO. Dengue and Severe Dengue. Published online 2020.

- 2.Cao-Lormeau V-M, Musso D. Emerging arboviruses in the Pacific. Lancet. 2014;384:1571–1572. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61977-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Failloux AB. Lessons learned on Zika virus vectors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(6):15–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey LL, Failloux A, Weaver SC. Chikungunya virus–vector interactions. Viruses. 2014;6:4628–4663. doi: 10.3390/v6114628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas SJ, Yoon IK. A review of Dengvaxia®: Development to deployment. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019;15(10):2295–2314. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1658503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswal S, et al. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381(21):2009–2019. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1903869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ant TH, Herd CS, Geoghegan V, Hoffmann AA, Sinkins P. The Wolbachia strain wAu provides highly efficient virus transmission blocking in Aedes aegypti. Viruses. 2018;14(1):e1006815. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xi Z, Dobson SL. Characterization of Wolbachia transfection efficiency by using microinjection of embryonic cytoplasm and embryo homogenate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71(6):3199–3204. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3199-3204.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker T, et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476(7361):450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann AA, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476:454–459. doi: 10.1038/nature10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anders KL, et al. Update to the AWED (Applying Wolbachia to Eliminate Dengue) trial study protocol: A cluster randomised controlled trial in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Trials. 2020;19(302):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutra HLC, et al. From lab to field: The influence of urban landscapes on the invasive potential of Wolbachia in Brazilian Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen TH, et al. Field evaluation of the establishment potential of wmelpop Wolbachia in Australia and Vietnam for dengue control. Parasit. Vectors. 2015;8(563):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pocquet N, et al. Assessment of fitness and vector competence of a New Caledonia wMel Aedes aegypti strain before field-release. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15(9):e0009752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu P, Bian G, Pan X, Xi Z. Wolbachia induces density-dependent inhibition to dengue virus in mosquito cells. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6(7):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross PA, et al. Heatwaves cause fluctuations in wMel Wolbachia densities and frequencies in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(1):e0007958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonçalves DDS, et al. Detecting wMel Wolbachia in field-collected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes using loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) Parasit. Vectors. 2019;12(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SF, White VL, Weeks AR, Hoffmann AA, Endersby NM. High-throughput PCR assays to monitor Wolbachia infection in the dengue mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and Drosophila simulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78(13):4740–4743. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00069-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jasper ME, et al. A LAMP assay for the rapid and robust assessment of Wolbachia infection in Aedes aegypti under field and laboratory conditions. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Hamzaoui B, et al. Detection of Bartonella spp. in fleas by MALDI-TOF MS. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12(2):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tahir D, et al. Assessment of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for filariae detection in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11(12):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laroche M, et al. MALDI-TOF MS as an innovative tool for detection of Plasmodium parasites in Anopheles mosquitoes. Malar J. 2017;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1657-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yssouf A, et al. Detection of Rickettsia spp. in Ticks by MALDI-TOF MS. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9(2):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nabet C, et al. Prediction of malaria transmission drivers in Anopheles mosquitoes using artificial intelligence coupled to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(11379):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68272-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012;25:1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakotonirina A, et al. MALDI-TOF MS: Optimization for future uses in entomological surveillance and identification of mosquitoes from New Caledonia. Parasit. Vectors. 2020;13(359):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belkin JN. The Mosquitoes of the South Pacific (Part B) (University of California Press, 1962).

- 30.Belkin, J. N. The Mosquitoes of the South Pacific (Diptera, Culicidae). Vol 1. (University of California Press, 1962).

- 31.Rueda LM. Pictorial keys for the identification of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) associated with Dengue Virus Transmission. Zootaxa. 2004;589:1–60. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.589.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee DJ et al. The Culicidae of Australian Region. Volume 4. Australian (1987).

- 33.Yssouf A, Almeras L, Raoult D, Parola P. Emerging tools for identification of arthropod vectors. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:549–566. doi: 10.2217/fmb.16.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yssouf A, et al. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization—time of flight mass spectrometry: An emerging tool for the rapid identification of mosquito vectors. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berrar, D. Cross-validation. In (eds. Ranganathan, S, Gribskov, M., Nakai, K., Schönbach, CBT-E of B and CB) 542–545 (Academic Press, 2019). 10.1016/B978-0-12-809633-8.20349-X

- 36.Refaeilzadeh, P., Tang, L. & Liu, H. Cross-validation BT—Encyclopedia of database systems. In (eds. Liu, L. & Özsu, M. T.) 532–538 (Springer, US, 2009). 10.1007/978-0-387-39940-9_565

- 37.WHO. Thirteenth Meeting of the WHO Vector Control Advisory Group. (2020).

- 38.Moreira LA, et al. A Wolbachia Symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139(7):1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yssouf A, et al. Identification of tick species and disseminate pathogen using hemolymph by MALDI-TOF MS. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6(5):579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross PA, et al. Wolbachia infections in Aedes aegypti differ markedly in their response to cyclical heat stress. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(1):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan X, et al. Wolbachia induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of the Toll pathway to control dengue virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109(1):E23–E31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116932108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kokoza V, et al. Blocking of Plasmodium transmission by cooperative action of Cecropin a and Defensin a in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(18):8111–8116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003056107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.