Abstract

This study investigates the role of sense of community in harnessing the wisdom of the crowd and creating collaborative knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also explores the impact of collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in such crises. PLS-SEM was used to analyze the data and test the research model. The results show that sense of community has a significant role in harnessing the wisdom of the crowd and creating collaborative knowledge. The results confirm a significant impact of sense of community, the wisdom of the crowd, and collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords: Sense of community, Wisdom of the crowd, Collaborative knowledge, Social media crowdsourcing, Perceived value

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has sparked alarm around the world, isolating people from the physical world that surrounds them. Countries have raced to stop the rapid transmission of the virus. Governments have enforced different forms of lockdowns, quarantines, and isolation measures, while closing institutions, limiting travel, and canceling social gatherings. The world’s cities have been deserted, with citizens having to stay indoors, either by choice or by government rule, leaving deep social, economic, and political scars. According to Lacalle (2020), the world faces a global crisis of unprecedented impact and high uncertainty. In one of the most sweeping viral outbreaks in recent history, social cohesion, sense of community, collaboration, and mutual support have become powerful catalysts for building resilience and adapting to the unprecedented pressures, risks, and changes that COVID-19 brings.

One of the biggest challenges during pandemics is ensuring an efficient, stable, and timely communication platform to build resilience to the shocks these crises cause (Huang et al., 2020, La et al., 2020). Thanks to social computing, the explosive growth of social media has provided powerful platforms and a new horizon to explore and exploit the possibility of collaborative work during crises and emergencies. There has been a remarkable shift in individual and collective social behaviors due to the widespread adoption of social media and the constant development of its applications and uses. As COVID-19 continues to affect everyone’s lives and consumer behaviors, the digital transformation process has experienced unprecedented growth that may not abate, even when the pandemic has passed (Kim, 2020). Social media has introduced new platforms that enable collaborative massive-scale interaction, providing novel, effective ways to create, share, integrate, and use knowledge in times of public health crisis (Gui et al., 2017, La et al., 2020).

Boyd and Martin (2020) confirmed that COVID-19 exposes people to novel thinking about a sense of community responsibility in the crisis. The tools of social media are novel and offer the preferred platforms to communicate, collaborate, and convey a sense of unity to large audiences, especially in times of crisis (Gui et al., 2017, Abdulhamid et al., 2020). These platforms have created renewable opportunities to bring individuals and groups together, building crowdsourcing communities that go beyond people’s sense of the self. In the COVID-19 crisis, social media have played an unprecedented role. At the beginning of the pandemic, risk perceptions and communication intensity increased due to the global dimension of the crisis and the sense of community that all citizens shared (Yu et al., 2020). According to Lev-On (2012), sense of community, which refers to individuals’ subjective feelings of attachment and belongingness to a social structure, represents the primary driver of crowdsourcing in crises. The literature (e.g., Howell and Taylor, 2011, Yates and Partridge, 2015, Abdulhamid et al., 2020) confirms the role of sense of community and the advances in social media in promoting the concept of crowdsourcing during crises and emergencies.

According to Boyd and Martin (2020), COVID-19 has proved that a sense of community is a pivotal responsibility to reduce the impact of pandemics. A sense of community gives individuals the feeling that they are not alone in the crisis and that others are experiencing similar hardships and difficulties. What has become apparent during past crises is that although there is a range of reasons for people to become involved in social media crowdsourcing, the overwhelming driver is sense of community (Howell & Taylor, 2011). Thus, the wisdom of the crowd is unleashed as a major outcome of crowdsourcing. According to Sethi (2017), the benefit of crowdsourcing lies principally in the wisdom of the crowd. The collaborative nature of social media allows crowds with diverse knowledge to create, share, and exchange new experiences, opinions, and innovative solutions to seemingly intractable problems and challenges, employing the collective intelligence of the crowd (Lykourentzou et al., 2011, Dissanayake et al., 2019). In the entrepreneurial environment, crisis management solutions are related to collaboration, synergies, and resilience. Innovation, customer-centric strategies, and social media management are recommended practices to overcome the COVID-19 crisis (Kuckertz et al., 2020).

A review of the literature reveals a lack of empirical research on the role of sense of community in social media crowdsourcing during pandemics. It also indicates that collaborative knowledge creation via social media has gained very little attention in the context of crises and emergencies. The research has largely ignored the wisdom of the crowd as a key outcome of crowdsourcing in times of crisis and emergency. There is a lack of scholarly research on the possible impact of sense of community on collaborative knowledge creation, the wisdom of the crowd, and the perceived value of social media at all times in general and during pandemics, such as COVID-19, in particular. While the impact of sense of community on collaborative interaction is clear, additional studies are needed to comprehend how this kind of social connection can be integrated into collaborative knowledge creation, the wisdom of the crowd, and the perceived value of social media, especially during pandemics. Therefore, this study explores the role of sense of community in establishing collaborative knowledge creation and the wisdom of the crowd. Furthermore, this study explores the impact of collaborative knowledge creation and the wisdom of the crowd on the perceived value of social media during pandemics.

The structure of the manuscript is as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on sense of community, social media crowdsourcing, and collaborative knowledge. The research hypotheses are also stated. Section 3 explains the method, data, and questionnaire. Section 4, presents the results. Section 5 compares the existing literature with the results of the study. Finally, Section 6 concludes with some guidelines, recommendations, and future research lines.

2. Theoretical background

This section provides a literature review of the main concepts presented in the introduction. The research model is then presented, along with the research hypotheses.

Throughout history, people have endeavored to share their values and thoughts and relate their feelings with others to sense that they actively belong to a group. This human social instinct or feeling is called sense of community and is described as emotional and behavioral loyalty to one or more social entities (Blanchard & Markus, 2004). In a time of crisis or emergency, a sense of community forms the backbone of trust and reduces anxiety (Fernandez & Shaw, 2020). The literature (e.g., Lev-On, 2012, Yates and Partridge, 2015, Boyd and Martin, 2020) explains that the collective effect of sense of community is a determinant of solidarity, social cohesion, the ability to meet local needs, and collective action among crowds during emergencies and long-term crises.

Social media platforms enable social and emotional support, empowering people to create and sustain virtual relationships and communities, express feelings, and share experiences (Howell and Taylor, 2011, Abdulhamid et al., 2020). The literature (e.g., Liu et al., 2018, Pang, 2020, Schreurs et al., 2020) investigates how social media can strengthen and even build a robust sense of community. Furthermore, studies (e.g., Baruch et al., 2016, Dissanayake et al., 2019) have investigated how crowdsourcing is positively associated with participants’ sense of community and belonging in terms of social media usage.

Crowdsourcing can be defined as a social, collaborative practice that is designed to achieve collective goals, is facilitated by Web 2.0 applications, and is based on an active crowd of volunteers responding to an open call for involvement (Baruch et al., 2016). The literature (e.g., Baruch et al., 2016, Dissanayake et al., 2019) reports that mobilizing and enhancing public participation via social media contributes to the wisdom of the crowd that leverages the value of crowdsourcing and engagement in online communities. Surowiecki (2004) uses the term “wisdom of crowds” to describe the superiority of groups over an individual in generating novel public opinions. The wisdom of the crowd can be viewed as shared memories, the collective mind of a community, and intellectual cooperation to generate wisdom. It also includes a synergy of resources and skills to achieve the common goals of the crowd (Dissanayake et al., 2019). However, it is affected by the personality of individuals. Innovativeness, extraversion and agreeableness are positively related with the impact in the individuals when using crowdsourcing tools (Ali, 2019). Regarding entrepreneurial orientation, it is extremely related with the international performance of individuals and organizations when working towards common objectives (Monteiro et al., 2019).

The literature abounds with research whose central themes revolve around crowdsourcing in crises and emergencies. For example, studies have focused on the role of the public in producing and sharing information through social media (e.g., Goodchild and Glennon, 2010, Munro, 2013, Elsayed, 2020) and crowdsourcing as a means to validate crisis information (e.g., Simon et al., 2015). Scholars (e.g., Qadir et al., 2016, Mulder et al., 2016) have studied motivations, enablers, and barriers of collection and analysis of crowdsourced big crisis data. A considerable number of studies (e.g., Ludwig et al., 2017, Abdulhamid et al., 2020) revolve around motivations, models, classifications, and frameworks of digital volunteer communities. However, the literature largely ignores the wisdom of the crowd as a key outcome of crowdsourcing, especially in times of crisis and emergency.

Despite the key role of sense of community in initiating collaboration, the literature reveals a paucity of studies exploring any potential relationship between collaborative knowledge creation and sense of community. Collaborative knowledge creation is defined as the process whereby people create new knowledge through cooperation and co-creation to develop a better understanding, gain insights, and respond to the changing environment by working together (Alshanty and Emeagwali, 2019, Zhao et al., 2019). Faraj et al. (2011) describe collaborative knowledge creation as the sharing, transfer, accumulation, and co-creation of knowledge. Collaborative knowledge creation is seen as one of the most important aspects of the social media philosophy and a major reason why virtual communities succeed (Zhang et al., 2019, Sweet et al., 2020). However, collaborative knowledge creation via social media has gained very little attention in the context of crises and emergencies.

The perceived value of participating in crowdsourcing efforts is an explanation as to why people join and engage in online crowds and a vital factor of whether social media plays a valuable role in crises and emergencies. According to Rauniar et al. (2014), perceived value is the extent to which users trust that using social media helps to meet their individual needs. It includes users’ general assessment and beliefs of the utility of creating and participating in online crowds based on users’ perceptions of what is required and what is delivered. Many studies (e.g., Rauniar et al., 2014, Annamalai et al., 2014, Vraga and Bode, 2018) have emphasized the idea that perceived value has a powerful role in continued participation in social media crowdsourcing. Research (e.g., Lev-On, 2012, Schimak et al., 2015, Abdulhamid et al., 2020) has widely investigated the motivations of voluntary participation in online crowdsourcing platforms. However, the literature lacks empirical research on the impact of sense of community, wisdom of the crowd, and collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in global crises.

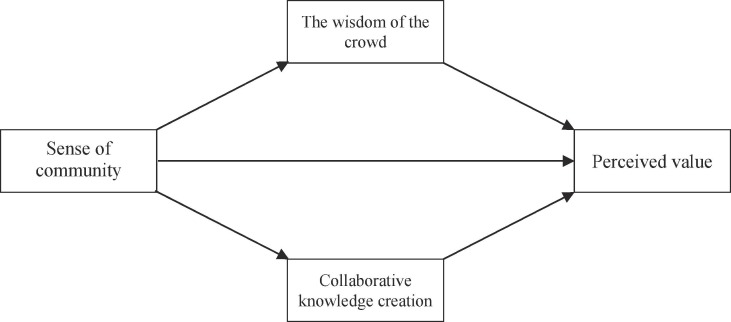

The research model of this study is presented in Fig. 1 . The model suggests that sense of community has a significant impact on the wisdom of the crowd, collaborative knowledge creation, and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

The research model also proposes a significant impact of wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing. Below each construct of the research model is discussed in detail, and in each case, the related hypothesis is then stated.

2.1. Sense of community and the wisdom of the crowd

The wisdom of the crowd is a valuable implication of grouping a large number of judgments to optimize diversity, volume of experience, and knowledge based on a large number of contributors from a wide variety of backgrounds (Görzen, 2019). Heath et al. (2009) suggest that a sense of being part of a community is a critical component of strategic emergency and crisis management, bringing together the collective wisdom that makes the public more fully functioning. Here, individual judgment and behavior become collective. The literature (e.g., Dissanayake et al., 2019, Xia et al., 2019) shows that sense of community is a central intrinsic motivator for active participation in the wisdom of the crowd. However, social scientists emphasize that scientists and professional authorities are not the only potential experts for a given risk or disaster. Wendling et al. (2013) claim that specific categories of the crowd can build experience when they are the victims of an event, such as infection with coronavirus, blurring the boundaries between those who know and those who do not.

The wisdom of the crowd is considered a major application of crowdsourcing based on collective intelligence (Lykourentzou et al., 2011). It is strongly powered by participatory social media platforms. According to Görzen (2019), social media platforms have provided an unprecedented level of citizen engagement in communities, leveraging the power of the wisdom of the crowd. Abdulhamid et al. (2020) also confirmed that social media tools serve as platforms for the collective wisdom of online volunteers who have a high sense of community responsibility in emergencies. The spread of social media has changed the landscape of sense of community, resulting in less dependence on official expertise, a greater sense of participation, and more trust in collaborative problem solving in crises and emergencies (Yates and Partridge, 2015, Conrado et al., 2016). In long-term crises and emergencies, social media have allowed the public to report on events on the ground, discussing opinions and information about risks, sending cautions, developing situational awareness, and even initiating and promoting crowd actions (Simon et al., 2015, La et al., 2020). In the current COVID-19 pandemic, organizations have promoted different ways to assist workers in information management and uncertainty coping (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020). Human resources management practices have also been challenged by this crisis, and social media have played an increasingly prominent role in connecting teams and colleagues to boost informal relationships in organizations. Thanks to these practices and the increase in sense of community, some companies have benefited from fresh synergies among employees (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020). Drawing on the previous discussion, this study tests if the sense of community plays a significant role in harnessing the wisdom of the crowd in responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

2.2. Sense of community and collaborative knowledge creation

Knowledge creation is an outcome of unconstrained collaboration and interaction among networks of people, where participants with different areas, expertise, backgrounds, and resources explore novel opportunities to adapt to existing situations (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). The literature (e.g., Mcfadyen et al., 2009) confirms the role of tie strength in enhancing collaborative knowledge creation. Research on virtual communities (e.g., Yilmaz, 2016, Sensuse and Bagustari, 2019, Lin, 2020) also emphasizes the idea that sense of community is a key factor in knowledge construction and sharing behavior. According to Liu et al. (2018), if people feel they belong to a community or are members of a group, they might contribute to that community more effectively, including by creating new knowledge. Yilmaz (2016) also confirmed that a strong feeling of a sense of community strengthens knowledge exchange and learning support. This social interaction can be achieved online though Internet platforms when face-to-face communication is not possible, as is the case with the COVID-19 crisis. Synchronous and asynchronous fluid communication with technology and social media is important to promote this feeling of community among participants, who may be workers in an organization or citizens in the same city or country, among others (Dwivedi et al., 2020).

The social nature of online collaborative communities provides a framework for tacit knowledge to be shared among members through a process of socially collaborative learning (Zhang et al., 2016, Elsayed, 2020). Such social networking platforms can support collective and collaborative cognition among members, creating novel and renewable knowledge. The literature (e.g., Hernández-Sellés et al., 2019; Lin, 2020) confirms that collaborative learning is a valuable approach to improve knowledge co-generation, helping crowd members to confront situations, where participants express ideas, voice opinions, and share experiences. According to Lin (2020), collaborative learning enables the cognitive process of collaborative knowledge creation. In education, collaborative learning and experience-based apprenticeship increases performance as well (Leal-Rodríguez & Albort-Morant, 2019). Sensuse and Bagustari (2019) emphasize the idea that online collaborative learning leverages active collaboration and interaction for both knowledge seekers and sharers. Recent studies (e.g., Hernández-Sellés et al., 2019; Boyd & Martin, 2020) have confirmed that promoting collaborative learning in communities first requires strengthening the sense of community. Therefore, the present study examines if the sense of community has a significant role in increasing collaborative knowledge creation in responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

2.3. Sense of community and perceived value

Disasters, crises, and emergencies are likely to be characterized by uncertainty and many forms of stress, motivating people to share not only information but also human contact, emotional care, and conversation (Veil et al., 2011). Shared perceived risks and threats have always been pivotal motives for mobilization of social cohesion and solidarity as powerful tools in struggling against new and emerging pandemics and diseases (Boyd & Martin, 2020). The COVID-19 outbreak shows that a sense of community is a central public responsibility in the attempts to mitigate the impact of viral spread (Boyd & Martin, 2020). Social media communication with all stakeholders contributes to building a sense of community that promotes belonging and trust and reduces anxiety (Fernandez & Shaw, 2020). Liu et al., 2018, Pang, 2020 describe social media as a facilitator for building a sense of community, allowing crowds to launch online communities, share feelings and information, and even contribute to the resolution of individuals’ concerns and problems, eventually reducing feelings of loneliness and promoting positive social values.

Sense of community is repeatedly cited as an ideal motivation for volunteers in citizen science (Lev-On, 2012, Yates and Partridge, 2015, Baruch et al., 2016). Sense of community has been found to influence continued social network use and virtual community member participation (Zhou, 2011, Liu et al., 2018). Lev-On (2012) argues that individuals with a strong sense of community feel a close emotional connection to the members of the community who they believe can fill their needs and indeed do so. Moreover, Boyd and Martin (2020) confirmed that a sense of community embodied in membership, shared emotional connections, and other fundamental needs are satisfied by the community context. Zhang et al. (2016) also emphasizes the idea that besides its effect on social networking systems use, sense of community also indirectly affects usage through participants’ satisfaction. In relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, Barnes (2020) affirms that the information management community has an opportunity to continue growing and strongly influence areas such as technology, work practices, politics, entertainment, business, and the economy(Lacalle, 2020). All these areas are important topics in relation to post-COVID-19 information management on social media (Winston, 2020). Based on this discussion, we test if the sense of community has a direct impact on an augmented perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

2.4. The wisdom of the crowd and perceived value

The wisdom of the crowd implies the superiority of groups over individuals in creating novel public opinions (Surowiecki, 2004). The power of the wisdom of the crowd relies on the ability of communities to find a better solution to the same problem and solve more problems than individual members through intellectual collaboration (Bellomo et al., 2016). The wisdom of the crowd has often been cited as collective intelligence and mining ideas from an enormous number of individuals, aggregating individual opinions that perform better than the opinion of experts (Surowiecki, 2004, Lykourentzou et al., 2011). Surowiecki (2004) suggests that groups of people can make a smarter decision than any of their members alone. Dissanayake et al. (2019) also emphasize the idea that diverse groups of individuals working together in synergy are much more effective in resolving complex problems than one individual working alone.

Clauss et al. (2018) claim that social media and Web 2.0 tools are primarily about the wisdom of the crowd, where online information is accessed, and communications spread to reach people collaboratively. In an entrepreneurial context, Martínez-Climent et al. (2020) reports that knowledge spillovers are achieved in society in Internet-based financial platforms such as crowdfunding websites. Thus, entrepreneurs and the crowd share different points of view about the same project and contribute to the success of investments. Christensen & Karlsson (2019) stated that crowdsourcing is an extremely related concept that boosts an organization’s open innovation and increases performance through the participation of the employees (the crowd). In medicine, Dissanayake et al. (2019) describe how the wisdom of the crowd solves medical mysteries, enabling access to diverse medical knowledge that has the potential to evaluate and resolve longstanding medical cases, identify high-quality solutions, and correct erroneous contributions. Recently, Kim and Walker (2020) confirmed that the wisdom of the crowd has been harnessed to improve the discovery of the spreading of misinformation about COVID-19 on social media. Misinformation should be seen from a risk communication perspective, covering aspects such as problems of trust, limits of knowledge, and fact-checking to fight against uncertainty (Krause et al., 2020). There is evidence that the crowd’s ability to distinguish between real and fake information and news is lacking (Mosinzova et al., 2019; Kim & Walker, 2020). However, research (e.g., Sethi, 2017, Mosinzova et al., 2019) has confirmed that crowdsourcing by taking advantage of the wisdom of the crowd is an effective solution to identify misinformation and verify fake news and alternative facts. For example, Vraga and Bode (2018) confirmed the role of volunteer fact-checkers as a valuable platform-governed effort in revising and recasting health misinformation. Based on this discussion, the present study examines if the wisdom of the crowd has a direct impact on an augmented perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

2.5. Collaborative knowledge creation and perceived value

The pooling of knowledge from external and internal crowds has social and individual qualities during crises and emergencies (Buldeo and Gilbert, 2015, Piltch-Loeb et al., 2019). Up-to-date public knowledge reflects not only the public’s perception of risks and threats but also people’s understanding of the benefits of medical countermeasures and protection in epidemic prevention efforts (Huang et al., 2020). In the context of public health crises and pandemics, many studies (e.g., Gui et al., 2017, Schoch-Spana et al., 2018, Huang et al., 2020) have investigated the importance of collaborative knowledge of the suspected risks, the dynamics of risk perception, and risk evaluation. Collaborative creation of knowledge about the pandemic can help to provide a rich understanding of the epidemic, protect people from infection, and assess and cope with unusual situations (Gui et al., 2017). In the context of COVID-19, collaborative knowledge has not only increased but also blurred work-life boundaries. Hoarding, improvisation, and the acceptance of digital technology are behaviors promoted by the pandemic (Sheth, 2020). The collaborative nature of social media empowers the public to play a more central role in all stages of knowledge creation, recombination, purification, and amplification. Accordingly, for public health professionals, it is essential to conduct a feedback circle and monitor online public responses and perceptions during emergencies to evaluate the usefulness of knowledge transformation and translation strategies and provide more effective communications and learning campaigns in the future (Piltch-Loeb et al., 2019, Boyd and Martin, 2020, La et al., 2020).

Research (e.g., Gui et al., 2017, Huang et al., 2020) has identified knowledge uncertainty as a major dilemma in crises, where those experiencing the crisis do not understand or know enough about what is happening and lack knowledge about how to respond. Knowledge creation in a community is a higher-order outcome that supports the public response during disasters, such as the outbreak of infectious diseases (Huang et al., 2020). Studies (e.g., Buldeo and Gilbert, 2015, Piltch-Loeb et al., 2019) have emphasized that accepting health interventions and responding to risk communications depend on acquiring knowledge and having an intention to bring about behavioral change in a social context. Hernández-Sellés et al. (2019) indicate that collaborative learning is a valuable solution to enhance the acquisition and development of new knowledge to help people to face unprecedented situations. In crowdsourcing, it has been revealed that pooling public knowledge from multiple participants increases the likelihood of exploring innovative solutions to complex problems and large-scale social issues (Dissanayake et al., 2019). Therefore, we test if collaborative knowledge creation has a direct impact on an increase in the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

3. Method

The present study was carried out using partial least squares (PLS) path modeling, a type of statistical data analysis. As a form of structural equation modeling (SEM), PLS has much value for examining new causal models and relationships to study social computing and behavior-related fields. Chin (1998) cites PLS as a preferable method for exploratory research, which is the essence of the present study. PLS-SEM is a popular and effective estimation method when theoretical models and paradigms that explain new causal relationships are limited (Chin, 1998), as is the case with the role of sense of community in the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation during pandemics. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), PLS-SEM does not require a large sample and is especially appropriate when data are non-normally distributed.

3.1. Measurement instruments and scales

The scale of each construct in the research model was taken from the literature (see Table 1 ). The scales relate to sense of community, the wisdom of the crowd, collaborative knowledge creation, and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing. Collaborative knowledge creation was measured using four dimensions of knowledge creation that have been emphasized in the literature: socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). The measure focused on the extent of collaboration in these dimensions.

Table 1.

Sources and references for measures.

| Construct | Code | No. items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of community | SC | 7 | Wilkinson, 2007, Al Omoush, 2019; Schreurs et al., 2020 |

| The wisdom of the crowd | WC | 6 | Surowiecki, 2004; Howell & Taylor, 2011 |

| Collaborative knowledge creation | KNC | 8 | Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Kruke and Olsen, 2012; Hernández-Sellés et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019 |

| Perceived value | PV | 8 | Sethi, 2017; Dissanayake et al., 2019; Lin, 2020 |

A pretest was conducted on a small sample of 32 respondents to validate the survey instrument and identify any formatting problems, ambiguities, or difficult questions. The measurement items were refined based on feedback to ensure that the questionnaire was clear and appropriately validated. All items were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). As shown in Table 2 , the questionnaire had 30 items.

Table 2.

Constructs and measurement items.

| Construct | Code | Measurement items |

|---|---|---|

| Sense of community | SC | Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements regarding social media crowds during the COVID-19 pandemic: |

| SC1 | I feel connected with crowds on social media. | |

| SC2 | Interacting with social media crowds gives me a sense that I belong to my community. | |

| SC3 | I have many close friends from the public crowd on social media. | |

| SC4 | I feel loyal to the crowd that I interact with on social media. | |

| SC5 | I agree with most members of my online community about prevention tips, priorities, realism, and events during the pandemic. | |

| SC6 | If I need any advice or help, I can resort to the crowd on social media. | |

| SC7 | I would never think of leaving or stopping interacting with the social media crowd. | |

| SC8 | I would work on something together with other members of the crowd on social media to help the resilience of my community during the pandemic. | |

| The wisdom of the crowd | WOC | Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements regarding the role of social media crowdsourcing during the COVID-19 pandemic: |

| WOC1 | The social media crowd is usually wiser than any given individual. | |

| WOC2 | Relying on crowd judgments is better than depending on only individual information and experience. | |

| WOC3 | Social media crowdsourcing facilitates the combination of individual perceptions into a collective perception. | |

| WOC4 | People tend to believe the online crowd’s opinions, advice, and recommendations rather than official campaigns. | |

| WOC5 | Ratings, reviews, and feedback of crowds leverage the value of participation in social media crowdsourcing. | |

| WOC6 | Social media crowdsourcing enriches the ability of a group to reach a solution that is better than that of any of its individual members. | |

| Collaborative knowledge creation | CKC | To what extent do social media crowds in the COVID-19 pandemic collaborate to: |

| CKC1 | Acquire new knowledge from many diverse sources. | |

| CKC2 | Create, discuss, and evaluate many novel ideas and suggestions collectively, using inductive and deductive thinking to acquire new knowledge. | |

| CKC3 | Use social media platforms for knowledge storage. | |

| CKC4 | Maintain and identify the format and type of knowledge stored on COVID-19 on a social media platform. | |

| CKC5 | Transmit newly created knowledge, experience, solutions, and best practices to the members of the crowd. | |

| CKC6 | Share new values, impressions, and thoughts with other members of the crowd. | |

| CKC7 | Enable the members of the crowd to conduct collective learning, renew knowledge, and put new learning to use. | |

| CKC8 | Help the members of the crowd to locate and access the necessary knowledge. | |

| Perceived value | PV | How important has social media crowdsourcing been to you during the pandemic in each of the following areas: |

| PV1 | Securing and fulfilling my humanitarian needs, such as food, transportation, and medical assistance. | |

| PV2 | Understanding more accurately what is happening and improving my perception of the COVID-19 crisis. | |

| PV3 | Promoting connectivity, cohesion, and social solidarity among people during the crisis. | |

| PV4 | Improving my knowledge about the pandemic when compared with traditional media. | |

| PV5 | Identifying misinformation and false rumors about COVID-19. | |

| PV6 | Discussing sensitive issues and complex information about COVID-19 with health professionals. | |

| PV7 | Sharing emotional support and checking on the status of family and friends, especially in affected areas. | |

| PV8 | Generally using social media actively during the COVID-19 crisis. |

3.2. Sampling and questionnaire distribution

Given the unprecedented situations and countermeasures against COVID‐19 and due to the nature of this study, an electronic questionnaire-based survey offered a suitable way to target the population and collect data. Facebook was employed as a public platform for social media crowdsourcing. The members of Facebook groups and pages were urged to answer the questionnaire. The participants were invited to call on more respondents and share the link to the survey. Thus, the snowball sampling method was adopted. The link to the online questionnaire was shared through WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and Jordanian Facebook pages to recruit more participants. These pages and groups usually have many participants from all the countries of the Arab world. The questionnaire was designed in English and translated into the Arabic language by a professional translator to ensure that respondents fully understand the survey questions. Another bilingual professional translated the questionnaire back from Arabic to English to confirm that both versions had the same linguistic interpretations with no semantic discrepancies.

A total of 379 responses were received and inspected, of which 22 were removed from further analysis. As a result, 357 usable questionnaires were retained for analysis. Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics.

| Sample characteristic | No. respondents | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 218 | 61 |

| Female | 139 | 39 | |

| Total | 357 | 100 | |

| Age | < 25 | 96 | 27 |

| 25–34 | 83 | 23 | |

| 35–44 | 67 | 19 | |

| 45–54 | 62 | 17 | |

| >54 | 49 | 14 | |

| Total | 357 | 100 |

4. Results

The measurement model was tested for convergent validity, internal consistency, and discriminant validity. Factor loadings, composite reliability, and the average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess convergent validity (Hair et al., 2013). An indicator with an outer loading between 0.4 and 0.7 was eliminated only if removing it raised the composite reliability (CR) or AVE above the suggested threshold (Hair et al., 2013). Any item with a low outer loading (<0.4) was removed from the scale.

The vast majority of indicators' outer loadings with their respective construct were greater than 0.4, thus demonstrating validity. However, one item was removed from the sense of community scale (SC7) and one from the collaborative knowledge creation scale (CKC4), due in both cases to a low item loading at level α = 0.05. Cronbach’s alpha, rho A, and CR were used to measure internal consistency. Table 4 lists the measurement model results, indicating that all constructs had acceptable values exceeding the threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2013). Table 4 indicates that all AVE values were greater than 0.5, which shows that all constructs explain more than half of the variance of their measures, suggesting adequate convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981, Hair et al., 2013).

Table 4.

Validity and reliability of research constructs.

| Construct | Cronbach’s alpha | rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of community | 0.906 | 0.947 | 0.923 | 0.632 |

| The wisdom of the crowd | 0.906 | 0.911 | 0.908 | 0,685 |

| Collaborative knowledge creation | 0.927 | 0.931 | 0.943 | 0.704 |

| Perceived value | 0.921 | 0.943 | 0.934 | 0.643 |

The assessment of the discriminant validity of measures was conducted by comparing cross-loadings between constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 5 reveals that the square root of AVE of each construct was greater than the correlations with the other constructs, indicating adequate discriminant validity.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity.

| No. | Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sense of community | 0.795 | |||

| 2 | The wisdom of the crowd | 0.568 | 0.828 | ||

| 3 | Collaborative knowledge creation | 0.487 | 0.447 | 0.839 | |

| 4 | Perceived value | 0.604 | 0.659 | 0.545 | 0.802 |

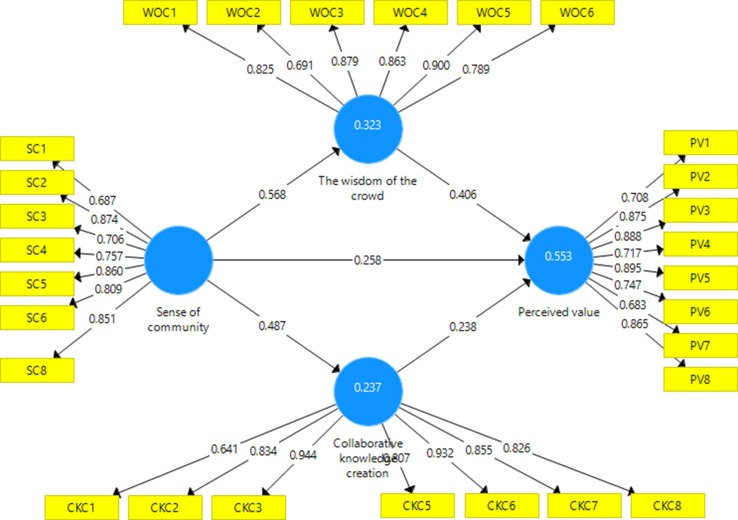

Fig. 2 represents the outcome of the structural modeling analysis, showing the causal relationships between the constructs. The path coefficient (β) and t value for each relationship were used to test the research hypotheses. A rule of thumb is that path coefficients higher than 0.1 with t values higher than 1.96 are significant at the 0.05 significance level (Hair et al., 2013).

Fig. 2.

Path coefficient analysis.

Table 6 summarizes the results of testing the direct relationship hypotheses. The results indicate a significant direct impact of sense of community on the wisdom of the crowd, collaborative knowledge creation, and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing.

Table 6.

Results of the hypothesis testing.

| H | β | t value | Sig. | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.568 | 10.766 | 0.001 | Supported |

| 2 | 0.487 | 6.789 | 0.000 | Supported |

| 3 | 0.258 | 2.997 | 0.003 | Supported |

| 4 | 0.406 | 4.604 | 0.000 | Supported |

| 5 | 0.238 | 3.472 | 0.001 | Supported |

The results also indicate that both the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation have a significant direct impact on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing.

5. Discussion

Social media are novel and popular platforms to communicate, collaborate, and convey a sense of unity. Social media help to build crowdsourcing communities that see beyond each individual’s self, especially in times of crisis and emergency. Although there is a range of reasons for people to become involved in social media crowdsourcing, the overwhelming driver is a sense of community. In global crises such as COVID-19, a sense of community has become a powerful catalyst for building resilience and adapting to the pressures, risks, and changes that the pandemic has caused. However, the literature reveals a lack of empirical studies of how this kind of social connection can be channeled into collaborative knowledge creation, the wisdom of the crowd, and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing, especially in pandemics. This study explores the role of sense of community in establishing collaborative knowledge creation and the wisdom of the crowd and their impact on the perceived value of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of this study reveal a significant role of sense of community in harnessing the wisdom of the crowd in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. These results are in line with the literature (e.g., Dissanayake et al., 2019, Xia et al., 2019), which reports that sense of community is a central intrinsic motivator for active participation in the wisdom of the crowd. The results also support prior research (e.g., Lykourentzou et al., 2011, Schimak et al., 2015, Abdulhamid et al., 2020) that emphasizes the idea that social media have provided an unprecedented level of citizen engagement in their communities by leveraging the power of crowdsourcing. In the context of COVID-19, recent research also confirms this idea (Kim, 2020, Kirk and Rifkin, 2020). Social media platforms have been a fundamental tool to change habits and purchasing behaviors.

The results indicate that sense of community has a significant role in collaborative knowledge creation in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. These findings are compatible with studies (e.g., Yilmaz, 2016, Sensuse and Bagustari, 2019, Lin, 2020) showing that sense of community is a determinant of knowledge construction and sharing behavior. They are also in line with recent studies (e.g., Hernández-Sellés et al., 2019; Boyd & Martin, 2020) that have cited strengthening the sense of community as the main ingredient for promoting collaborative learning in virtual communities.

The findings emphasize the idea that sense of community has a direct impact on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. These results are in agreement with those of studies (e.g., Lev-On, 2012, Yates and Partridge, 2015, Baruch et al., 2016) considering the sense of community itself as an ideal motivation for online volunteers who actively participate in virtual communities. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with recent studies (e.g., Liu et al., 2018, Pang, 2020, Boyd and Martin, 2020) of the role of sense of community in crises and emergencies in terms of providing emotional support, sharing risks and threats, reducing anxiety, building social trust, mobilizing social cohesion and solidarity, and sharing feelings and information.

The results indicate that the wisdom of the crowd has a direct impact on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing. Studies (e.g., Baruch et al., 2016, Dissanayake et al., 2019) have shown that mobilizing and enhancing public participation via social media contributes to the wisdom of the crowd that leverages the value of crowdsourcing and engagement in online communities. These results are also compatible with research (e.g., Sethi, 2017, Kim and Walker, 2020) showing that crowdsourcing takes advantage of the wisdom of the crowd and offers an effective solution to identify misinformation and verify fake news and alternative facts.

Finally, the results confirm the impact of collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. According Huynh (2020), understanding risk perceptions through social media use and personal information management is important to predict and reduce the global threat of the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings are in line with research (e.g., Gui et al., 2017, Huang et al., 2020) indicating that knowledge creation within a community context contributes to improving the public response to emerging infectious diseases. Recent studies (e.g., Dissanayake et al., 2019, Piltch-Loeb et al., 2019, Boyd and Martin, 2020) have revealed that pooling public knowledge from multiple participants increases the likelihood of exploring innovative solutions to complex problems and large-scale social issues. However, these results are also in agreement with those of previous studies (e.g., Gui et al., 2017, Schoch-Spana et al., 2018, Huang et al., 2020) investigating the importance of collaborative knowledge of the suspected risks, as well as the dynamics of risk perception and risk evaluation in public health crises and pandemics.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the role of sense of community in harnessing the wisdom of the crowd, collaborative knowledge creation, and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. Furthermore, the study explores the impact of the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing during the crisis.

The results of the study confirm the role of sense of community responsibility during the pandemic in empowering social media crowdsourcing. The result is feeling connected with crowds, sensing that individuals belong to the community, strengthening, and building close friendship ties among participants. According to these results, a sense of community contributes to finding common ground in cohesion and compatibility, feeling loyal to the crowd in such difficult times, providing mutual support, and promoting collaboration and teamwork to foster the resilience of the community in the face of a pandemic.

The findings of this study reveal that sense of community plays a significant role in harnessing the wisdom of the crowd during pandemics, facilitating the combination of individual perceptions into a collective perception that provides a community that, together, is wiser than its participating individuals. A sense of community inspires and enriches the ability of a crowd to reach a solution that is better than any solution achieved by its members individually. It leverages the value of participation in social media crowdsourcing and trust in the online crowd’s opinions, advice, and recommendations rather than individual experience or even official campaigns.

The results reveal that a sense of community during pandemics has a significant role in evoking the dimensions of collaborative knowledge creation, namely socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization. The sense of being part of a community is a central intrinsic motivator for acquiring new knowledge from diverse sources or creating, discussing, and evaluating novel ideas and opinions collectively to acquire new knowledge. It is a powerful catalyst for transmitting newly created knowledge, experience, solutions, and best practices, as well as for sharing new values, impressions, and thoughts with other members of the crowd. The results also imply that the sense of community enables the members of the crowd to conduct collaborative learning, renew knowledge, and provide help to locate and access the necessary knowledge.

The collective effect of a sense of community during pandemics, which includes individuals’ subjective feelings of attachment and belongingness, promotes connectivity, cohesion, emotional support, and social solidarity among people. It also empowers the crowd to initiate collaboration among participants to secure and fulfill basic humanitarian needs and the need to improve the perception and understanding of what is happening during the crisis. Furthermore, the results indicate that sense of community provides the opportunity to identify misinformation and false rumors and discuss sensitive issues related to the COVID-19 outbreak with health and medical professionals, as well as those who have been infected with the coronavirus.

Finally, the findings reveal that the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation have direct impacts on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. These results imply that the outcomes of sense of community and the resulting collaboration open the way for collective activities and efforts that enhance the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in such crises. They confirm that the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation play pivotal roles in satisfying basic humanitarian needs, gaining knowledge, understanding and learning about COVID-19, and promoting social and emotional support.

The present study makes a valuable contribution to the field of online sense of community, the wisdom of the crowd, and collaborative knowledge creation in pandemics, while enriching the knowledge of academics and practitioners. The world in which social media crowdsourcing and the wisdom-of-the-crowd paradigms emerged had never before encountered a pandemic such as that of COVID-19. The present study opens new opportunities for the empirical exploration of the role of online sense of community in pandemics.

The findings of the study contribute to the ongoing discussion about sense of community, introducing the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation in responding to global pandemics as a new area to predict the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing during such global crises. Seemingly, no previous studies have examined the role of sense of community in harvesting the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation in responding to such crises. Furthermore, no research has empirically investigated the impact of sense of community, the wisdom of the crowd, and collaborative knowledge creation on the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in pandemics. This sense of community and wisdom of the crowd should be promoted by governments and scientific communities, encouraging scientists and academics all over the world to contribute to the community. Learning from others and sharing experiments and results can lead to an enhanced global solution to the health and economic crisis caused by COVID-19 (Chesbrough, 2020, Woodside, 2020).

The findings of the present study contribute to launching a new discussion about the pivotal role of sense of community in enhancing the chances of successful social media crowdsourcing implementation during global pandemics. This study covers the importance of the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing as a performance evaluation measure of sense of community responsibility, the wisdom of the crowd, and collaborative knowledge creation in responding to global pandemics.

The results of this study have several practical implications. They confirm the importance of the sense of community responsibility given que enormous number of online groups and volunteers involved in crowdsourcing efforts during the COVID-19 crisis. Given the effects of the COVID-19 global health crisis, this study illuminates how a sense of community can support individual and collective responses to disease outbreaks through social media crowdsourcing. The findings can help authorities, civil society organizations, online volunteers, and other stakeholders to develop successful social media crowdsourcing initiatives, employing their sense of community responsibly to enhance pandemic management and response strategies. This study highlights the importance of building informational, collaborative, and social contexts using social media crowdsourcing to promote a sense of community responsibility during pandemics.

This study confirms that the perceived value of social media during pandemics can be gained from the collaborative efforts and understanding of how to employ crowdsourcing to harness the wisdom of the crowd and collaboratively create new knowledge that benefits society as a whole. The research model presents a paradigm for understanding the relationships between sense of community and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in pandemics. This study also explores the role of perceived value as a performance evaluation measure of sense of community, the wisdom of the crowd, and collaborative knowledge creation in responding to the coronavirus pandemic. It shows how the power of a sense of community contributes to building and harnessing the wisdom of the crowd and collaborative knowledge creation as predictors of the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in such crises.

This study has some limitations that open up new directions for future research. The sample population invited to participate in this study was just a tiny part of the Facebook user universe and is not representative of the entire population of Facebook users. Data were primarily collected from the Arab world. In other words, if similar studies are carried out in other cultures, they may yield different findings. Consequently, scholars should take caution when generalizing the conclusions and insights to other cultures or geographical areas beyond the Middle East. Future research should focus on larger samples of Facebook users, countries, and regions to verify the results of the study. Although a sense of community is important, many factors included in behavioral theories must be examined in future studies to extend the research model and improve the prediction of the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing in pandemics. Furthermore, the present study ignores the impact of the demographic characteristics of respondents from different backgrounds, areas of expertise, and age groups. Furthermore, sense of community, the wisdom of the crowd, collaborative knowledge creation, and the perceived value of social media crowdsourcing may change over time due to changes in the status of the pandemic or increases in crowd members’ experience and knowledge. Consequently, a longitudinal study could be beneficial for a better understanding of the dynamics of these factors in pandemics.

Biographies

Khaled Saleh Al Omoush is an associate professor of Management Information Systems at the Faculty of business, Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan, where he has been a faculty member since 2008. Al Omoush’s research interests lie in the areas of Web-based collaborative systems, social networking sites, and e-business entrepreneurship. He has published many articles in different journals and international conferences on the critical success factors of Web-based supply chain collaboration, the impact of cultural values on IT adoption, collective intelligence, governance of IT-business relationship quality and performance outcomes, SNSs in Arab world, e-business entrepreneurship, and harnessing mobile-social networking to participate in crisis management in war-torn societies.

Maria Orero-Blat is a Research and Teaching Assistant in Business Organization Department at the Universitat Politècnica de València. She has published in several top-ranked journals such as the Journal of Business Research, the Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, or Economic Research, among others. She is the coordinator of the Chair “Entrepreneurship: From being student to entrepreneur”- Grupo Maicerías Españolas-Arroz DACSA and contributes to the academic scope for ACIEK Conferences.

Domingo Ribeiro-Soriano is a Professor of Business Administration at the Universitat de València, Spain. He has published more than 100 papers in SSCI-ranked journals. Throughout his career, he has edited and contributed to books and conferences. He has also led several EU-funded projects. Before starting his career in academia, he worked as a consultant at EY (formerly Ernst & Young).

References

- Abdulhamid N.G., Ayoung D.A., Kashefi A., Sigweni B. A survey of social media use in emergency situations: A literature review. Information Development. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Al Omoush K.S. Harnessing mobile-social networking to participate in crises management in war-torn societies: The case of Syria. Telematics and Informatics. 2019;41:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ali I. Personality traits, individual innovativeness and satisfaction with life. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2019;4(1):38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Alshanty A.M., Emeagwali O.L. Market-sensing capability, knowledge creation and innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial-orientation. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2019;4(3):171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai C., Koay S.S., Lee S.M. Role of social networking in disaster management: An empirical analysis. Journal of Computation In Biosciences And Engineering. 2014;1(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S.J. Information management research and practice in the post-COVID-19 world. International Journal of Information Management. 2020;102175 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch A., May A., Yu D. The motivations, enablers and barriers for voluntary participation in an online crowdsourcing platform. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;64:923–931. [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo N., Clarke D., Gibelli L., Townsend P., Vreugdenhil B.J. Human behaviours in evacuation crowd dynamics: From modelling to “big data” toward crisis management. Physics of Life Reviews. 2016;18:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard A.L., Markus M.L. The experienced“ sense” of a virtual community: Characteristics and processes. ACM Sigmis Database: The Database for Advances in Information Systems. 2004;35(1):64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd N.M., Martin E.C. Sense of community responsibility at the forefront of crisis management. Administrative Theory & Praxis. 2020:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Buldeo P., Gilbert L. Exploring the Health Belief Model and first-year students’ responses to HIV/AIDS and VCT at a South African university. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2015;14(3):209–218. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2015.1052527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale J.B., Hatak I. Employee Adjustment and Well-Being in the Era of COVID-19: Implications for Human Resource Management. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough H. To recover faster from Covid-19, open up: Managerial implications from an open innovation perspective. Industrial Marketing Management. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G.A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern Methods For Business Research (pp. 295–358). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

- Christensen I., Karlsson C. Open innovation and the effects of Crowdsourcing in a pharma ecosystem. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2019;4(4):240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss T., Breitenecker R.J., Kraus S., Brem A., Richter C. Directing the wisdom of the crowd: The importance of social interaction among founders and the crowd during crowdfunding campaigns. Economics of Innovation and New Technology. 2018;27(8):709–729. [Google Scholar]

- Conrado S.P., Neville K., Woodworth S., O’Riordan S. Managing social media uncertainty to support the decision making process during emergencies. Journal of Decision Systems. 2016;25(1):171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake I., Nerur S., Singh R., Lee Y. Medical Crowdsourcing: Harnessing the “Wisdom of the Crowd” to Solve Medical Mysteries. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2019;20(11):4. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y.K., Hughes D.L., Coombs C., Constantiou I., Duan Y., Edwards J.S.…Raman R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. International Journal of Information Management. 2020;102211 [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed F.E. Social Media Role in Relieving the Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis. New Media and Mass Communication. 2020;87(1):28–48. [Google Scholar]

- Faraj S., Jarvenpaa S.L., Majchrzak A. Knowledge collaboration in online communities. Organization Science. 2011;22(5):1224–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A.A., Shaw G.P. Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. Journal of Leadership Studies. 2020;14(1):39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild M.F., Glennon J.A. Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: A research frontier. International Journal of Digital Earth. 2010;3(3):231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Görzen, T. (2019, January). Can Experience be Trusted? Investigating the Effect of Experience on Decision Biases in Crowdworking Platforms. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 4385-4394.

- Gui X., Kou Y., Pine K.H., Chen Y. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2017. May). Managing uncertainty: Using social media for risk assessment during a public health crisis; pp. 4520–4533. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning. 2013;46(1–2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heath R.L., Lee J., Ni L. Crisis and risk approaches to emergency management planning and communication: The role of similarity and sensitivity. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2009;21(2):123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sellés N., Muñoz-Carril P.C., González-Sanmamed M. Computer-supported collaborative learning: An analysis of the relationship between interaction, emotional support and online collaborative tools. Computers & Education. 2019;138:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Howell G.V., Taylor M. When a crisis happens, who turns to Facebook and why? Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal. 2011;12(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Peng Z., Wu H., Xie Q. A big data analysis on the five dimensions of emergency management information in the early stage of COVID-19 in China. Journal of Chinese Governance. 2020;5(2):213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh T.L. The COVID-19 risk perception: A survey on socioeconomics and media attention. Econ. Bull. 2020;40(1):758–764. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Walker D. Leveraging volunteer fact checking to identify misinformation about COVID-19 in social media. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. 2020;1(3):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kim R.Y. The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumers: Preparing for Digital Sales. IEEE Engineering Management Review. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Kirk C.P., Rifkin L.S. I'll Trade You Diamonds for Toilet Paper: Consumer Reacting, Coping and Adapting Behaviors in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Business Research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N.M., Freiling I., Beets B., Brossard D. Fact-checking as risk communication: The multi-layered risk of misinformation in times of COVID-19. Journal of Risk Research. 2020:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kruke B.I., Olsen O.E. Knowledge creation and reliable decision-making in complex emergencies. Disasters. 2012;36(2):212–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckertz A., Brändle L., Gaudig A., Hinderer S., Reyes C.A.M., Prochotta A.…Berger E.S. Startups in times of crisis–A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Venturing Insights. 2020;e00169 [Google Scholar]

- La, V. P., Pham, T. H., Ho, M. T., Nguyen, M. H., P Nguyen, K. L., Vuong, T. T., ... & Vuong, Q. H. (2020). Policy response, social media and science journalism for the sustainability of the public health system amid the COVID-19 outbreak: The Vietnam lessons. Sustainability, 12(7), 2931.

- Lacalle D. Monetary and Fiscal Policies in the COVID-19 Crisis. Will They Work? Journal of Business Accounting and Finance. Perspectives. 2020;2(3):18. doi: 10.35995/jbafp2030018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Rodríguez A.L., Albort-Morant G. Promoting innovative experiential learning practices to improve academic performance: Empirical evidence from a Spanish Business School. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2019;4(2):97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lev-On A. Communication, community, crisis: Mapping uses and gratifications in the contemporary media environment. New Media & Society. 2012;14(1):98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lin G.Y. Scripts and mastery goal orientation in face-to-face versus computer-mediated collaborative learning: Influence on performance, affective and motivational outcomes, and social ability. Computers & Education. 2020;143:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Shao Z., Fan W. The impact of users’ sense of belonging on social media habit formation: Empirical evidence from social networking and microblogging websites in China. International Journal of Information Management. 2018;43:209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig T., Kotthaus C., Reuter C., Van Dongen S., Pipek V. Situated crowdsourcing during disasters: Managing the tasks of spontaneous volunteers through public displays. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2017;102:103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lykourentzou I., Vergados D.J., Kapetanios E., Loumos V. Collective intelligence systems: Classification and modeling. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Web Intelligence. 2011;3(3):217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Climent C., Mastrangelo L., Ribeiro-Soriano D. The knowledge spillover effect of crowdfunding. Knowledge Management Research & Practice. 2020:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- McFadyen M.A., Semadeni M., Cannella A.A., Jr Value of strong ties to disconnected others: Examining knowledge creation in biomedicine. Organization Science. 2009;20(3):552–564. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro A.P., Soares A.M., Rua O.L. Linking intangible resources and entrepreneurial orientation to export performance: The mediating effect of capabilities. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2019;4(3):179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Mosinzova, V., Fabian, B., Ermakova, T., & Baumann, A. (2019). Fake News, Conspiracies and Myth Debunking in Social Media-A Literature Survey Across Disciplines. Conspiracies and Myth Debunking in Social Media-A Literature Survey Across Disciplines (February 3, 2019), 1-17.

- Mulder F., Ferguson J., Groenewegen P., Boersma K., Wolbers J. Questioning Big Data: Crowdsourcing crisis data towards an inclusive humanitarian response. Big Data & Society. 2016;3(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Munro R. Crowdsourcing and the crisis-affected community. Information Retrieval. 2013;16(2):210–266. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka I., Takeuchi H. Oxford University Press; 1995. The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Examining associations between university students' mobile social media use, online self-presentation, social support and sense of belonging. Aslib Journal of Information Management. 2020;72(3):321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Piltch-Loeb R., Merdjanoff A.A., Bhanja A., Abramson D.M. Support for vector control strategies in the United States during the Zika outbreak in 2016: The role of risk perception, knowledge, and confidence in government. Preventive Medicine. 2019;119:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, J., Ali, A., ur Rasool, R., Zwitter, A., Sathiaseelan, A., & Crowcroft, J. (2016). Crisis analytics: big data-driven crisis response. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 1(1), 1-21.

- Rauniar R., Rawski G., Yang J., Johnson B. Technology acceptance model (TAM) and social media usage: An empirical study on Facebook. Journal of Enterprise Information Management. 2014;27(1):6–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schimak, G., Havlik, D., & Pielorz, J. (2015, March). Crowdsourcing in crisis and disaster management–challenges and considerations. In International Symposium on Environmental Software Systems (pp. 56-70). Springer, Cham.

- Schoch-Spana M., Brunson E., Chandler H., Gronvall G.K., Ravi S., Sell T.K., Shearer M.P. Recommendations on how to manage anticipated communication dilemmas involving medical countermeasures in an emergency. Public Health Reports. 2018;133(4):366–378. doi: 10.1177/0033354918773069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs W., Franjkić N., Kerstholt J.H., De Vries P.W., Giebels E. Why do citizens become a member of an online neighbourhood watch? A case study in The Netherlands. Police Practice and Research. 2020:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sensuse, D. I., & Bagustari, B. A. (2019, August). Collaborative Learning Strategies for Online Knowledge Sharing Tool Within Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review. In 2019 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech) (Vol. 1, pp. 652-657). IEEE.

- Sethi, R. J. (2017, July). Crowdsourcing the verification of fake news and alternative facts. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (pp. 315-316).

- Sheth J. Impact of Covid-19 on Consumer Behavior: Will the Old Habits Return or Die? Journal of Business Research. 2020;117:280–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon T., Goldberg A., Adini B. Socializing in emergencies—A review of the use of social media in emergency situations. International Journal of Information Management. 2015;35(5):609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Surowiecki J. Anchor Books; New York, NY: 2004. The wisdom of crowds. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet K.S., LeBlanc J.K., Stough L.M., Sweany N.W. Community building and knowledge sharing by individuals with disabilities using social media. Journal of Computer Assisted learning. 2020;36(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Veil S.R., Buehner T., Palenchar M.J. A work-in-process literature review: Incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2011;19(2):110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Vraga E.K., Bode L. I do not believe you: How providing a source corrects health misperceptions across social media platforms. Information, Communication & Society. 2018;21(10):1337–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Wendling C., Radisch J., Jacobzone S. The use of social media in risk and crisis communication. OECD Working Papers on Public. Governance. 2013:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D. The multidimensional nature of social cohesion: Psychological sense of community, attraction, and neighboring. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40(3–4):214–229. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston, A. (2020). Is the COVID-19 Outbreak a Black Swan or the New Normal. MIT Sloan Management Review, March.

- Woodside A.G. Interventions as experiments: Connecting the dots in forecasting and overcoming pandemics, global warming, corruption, civil rights violations, misogyny, income inequality, and guns. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H., Østerlund, C., McKernan, B., Folkestad, J., Rossini, P., Boichak, O., ... & Stromer-Galley, J. (2019, January). TRACE: A stigmergic crowdsourcing platform for intelligence analysis. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 440-448.

- Yates C., Partridge H. Citizens and social media in times of natural disaster: Exploring information experience. Information Research. 2015;20(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz R. Knowledge sharing behaviors in e-learning community: Exploring the role of academic self-efficacy and sense of community. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;63:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Li Z., Yu Z., He J., Zhou J. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current Issues in Tourism. 2020:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Shang X., Luan H., Wang M., Chua T. Learning from collective intelligence: Feature learning using social images and tags. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, and Applications (TOMM) 2016;13(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang M., Luo N., Wang Y., Niu T. Understanding the formation mechanism of high-quality knowledge in social question and answer communities: A knowledge co-creation perspective. International Journal of Information Management. 2019;48:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Zhang H., Wu W. Cooperative knowledge creation in an uncertain network environment based on a dynamic knowledge supernetwork. Scientometrics. 2019;119(2):657–685. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T. Understanding online community user participation: A social influence perspective. Internet Research. 2011;21(1):67–81. [Google Scholar]