Abstract

SH2-Bβ has been shown to bind via its SH2 (Src homology 2) domain to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 and strongly activate JAK2. In this study, we demonstrate the existence of an additional binding site(s) for JAK2 within the N-terminal region of SH2-Bβ (amino acids 1 to 555) and the ability of this region of SH2-B to inhibit JAK2. Four lines of evidence support the existence of this additional binding site(s). In a glutathione S-transferase pull-down assay, wild-type SH2-Bβ and SH2-Bβ(R555E) with a defective SH2 domain bind to both tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 from growth hormone (GH)-treated cells and non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 from control cells, whereas the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ binds only to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 from GH-treated cells. Similarly, JAK2 is present in αSH2-B immunoprecipitates in the absence and presence of GH, with GH substantially increasing the coprecipitation of JAK2 with SH2-B. When coexpressed in COS cells, SH2-Bβ coimmunoprecipitates not only wild-type, tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 but also kinase-inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2(K882E), although to a lesser extent. ΔC555 (amino acids 1 to 555 of SH2-Bβ) that lacks most of the SH2 domain binds similarly to wild-type JAK2 and kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E). Experiments using a series of N- and C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ constructs indicate that the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (amino acids 269 to 410) and amino acids 410 to 555 are necessary for maximal binding of SH2-Bβ to inactive JAK2, but neither region alone is sufficient for maximal binding. The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is necessary and sufficient for the stimulatory effect of SH2-Bβ on JAK2 and JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B. In contrast, ΔC555 lacking the SH2 domain, and to a lesser extent the PH domain alone, inhibits JAK2. ΔC555 also blocks JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B in COS cells and GH-stimulated nuclear accumulation of Stat5B in 3T3-F442A cells. These data indicate that in addition to the SH2 domain, SH2-Bβ has one or more lower-affinity binding sites for JAK2 within amino acids 269 to 555. The interaction via this site(s) in SH2-B with inactive JAK2 seems likely to increase the local concentration of SH2-Bβ around JAK2, thereby facilitating binding of the SH2 domain to ligand-activated JAK2. This would result in a more rapid and robust cellular response to hormones and cytokines that activate JAK2. This interaction between inactive JAK2 and SH2-B may also help prevent abnormal activation of JAK2.

Members of the cytokine receptor family do not have any enzymatic activity but instead associate constitutively or ligand inducibly with members of the Janus family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyk2). Upon ligand stimulation, the receptor-associated JAKs are activated. The activated JAKs phosphorylate both the receptors and themselves on multiple tyrosines, generating docking sites for downstream signaling molecules that contain SH2 or other phosphotyrosine-interacting domains. Recruitment of these signaling molecules into the receptor-JAK complexes activates these signaling molecules or enables the activated JAKs to phosphorylate and activate them, thereby initiating a variety of downstream signaling pathways that lead to a wide range of biological responses. One class of well-studied substrates of JAKs is the signal transducers and activators of transcription (Stats). Stats are latent transcription factors present in the cytoplasm. In response to hormones and cytokines, Stats are recruited to receptor-JAK complexes and phosphorylated by JAKs on a conserved C-terminal tyrosine. This phosphotyrosine binds to the SH2 domain in other Stats, thus forming Stat homo- or heterodimers that migrate into the nucleus, bind to their response elements, and regulate expression of their target genes (5, 15). Stats play an essential role in cytokine signaling. For example, Stat1, -3, -4, -5A, -5B, and -6 are required for many of the actions of gamma interferon (2, 19), interleukin-6 (IL-6) (20, 22, 38), IL-12 (40), prolactin (18, 39), growth hormone (GH) (39, 41), and IL-4 (35), respectively.

Activation of JAKs is an obligatory step for cytokine action (13, 14). In the presence of ligands, one or more JAKs bind to a membrane proximal proline-rich region of cytokine receptors (1, 13, 14). It is thought that ligand binding causes homo- or hetero-oligomerization of cytokine receptor subunits. As a result, receptor-associated JAKs are brought into proximity, enabling JAKs to transphosphorylate each other on tyrosines within the kinase domain, resulting in activation (9, 26). Among ligands known to bind to members of the cytokine receptor family, more than two-thirds are known to activate JAK2; these include GH, erythropoietin, leptin, prolactin, gamma interferon, leukemia inhibitory factor, cardiotropin, ciliary neurotrophic factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, thrombopoietin, oncostatin M, IL-2, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-11, and IL-12 (1). Factors other than cytokine receptors also regulate JAK2. For instance, oxidized JAK2 is inactive whereas the reduced form of JAK2 is active (6), suggesting that oxidation is a regulatory mechanism for JAK2. SOCS-1/JAB, a cytokine-inducible protein, binds and inhibits JAK2, thereby serving as a negative feedback regulator of cytokine responses (7, 21, 37).

Recently, we identified SH2-Bβ as a JAK2-interacting protein and a potent activator of JAK2 that is likely to play an important role in signaling by cytokines that activate JAK2 (30, 34). Three isoforms of SH2-B (α, β, and γ) have been described to date (23, 25, 29, 34). They are identical except for the short C-terminal portion after the SH2 domain and are thought to be a result of alternative splicing of a single gene. SH2-B has multiple protein-protein interaction motifs, including an SH2 domain, a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, multiple proline-rich regions, and numerous potential phosphorylation sites. Because of these motifs, SH2-B is thought to be an adapter protein in addition to being an activator of JAK2 (27, 31, 33, 34, 43). Because of the ability of SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2 and presumably mediate additional functions of ligands that activate JAK2, it is important to determine how SH2-Bβ interacts with JAK2. In this work, we provide evidence that SH2-Bβ binds to JAK2 via multiple sites: the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ (amino acids 526 to 620) that binds to one or more phosphotyrosines in JAK2; and one or more sites within amino acids 269 to 555 that bind to JAK2 independent of the kinase activity and tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2. The SH2 domain is necessary and sufficient for SH2-Bβ to stimulate JAK2. In contrast, the N-terminal 555 amino acids of SH2-Bβ inhibit JAK2. We propose a model in which the interaction of the N-terminal region of SH2-Bβ with JAK2 not only increases the subcellular local concentration of SH2-Bβ but also inhibits basal and/or abnormal activation of JAK2. The former enables the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ to bind to JAK2 and enhance JAK2 activity as soon as JAK2 is activated by ligand binding, leading to a more robust cellular response to hormones and cytokines that activate JAK2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Recombinant human GH was a gift of Eli Lilly and Co. Recombinant protein A-agarose was from Repligen. Aprotinin, leupeptin, and Triton X-100 were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. The enhanced chemiluminescence detection system and [γ-32P]ATP were from Amersham Corp. Polyclonal antibodies to rat SH2-Bβ (αSH2-B) were raised against a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing the C-terminal portion of SH2-Bβ as described previously (34) and used at dilutions of 1:100 for immunoprecipitation and 1:15,000 for immunoblotting. Anti-JAK2 antiserum (αJAK2) was raised in rabbits against a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 758 to 776 (36) and was used at dilutions of 1:500 for immunoprecipitation and 1:15,000 for immunoblotting. Monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (αPY) was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology Inc. and used at a dilution of 1:7,500 for immunoblotting. Monoclonal antibody against Myc-tag (9E10; αMyc) and polyclonal anti-Stat5B antibody (αStat5B) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. αMyc was used at dilutions of 1:100 for immunoprecipitation and 1:1,000 for immunoblotting. αStat5B was used at dilutions of 1:100 for immunoprecipitation and 1:5,000 for immunoblotting. Monoclonal anti-phospho-Stat5 (αpStat5) was from Zymed Laboratories Inc. and used at 1 μg/ml in immunoblotting.

Plasmids.

cDNAs encoding both wild-type murine JAK2 [JAK2 (WT)] and mutant murine JAK2(K882E), in which the critical lysine in the ATP binding domain is mutated to glutamate, were previously cloned into a mammalian expression vector and provided by J. Ihle and B. Witthuhn (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital). Plasmid encoding rat Stat5B was from L. Yu-Lee (Baylor College of Medicine). Construction of vectors encoding SH2-Bβ or SH2-Bβ(R555E) (with a defective SH2 domain) with a Myc tag at the N terminus (30) and Stat5B with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag at the N terminus (GFP-Stat5B) (12) has been described previously. To generate a series of N- or C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ, restriction sites were inserted at appropriate positions in SH2-Bβ by using a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The correspondent restriction enzyme was used to delete the N- or C-terminal portion of SH2-Bβ. A detailed protocol will be provided upon request.

Cell culture and transfection.

3T3-F442A cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.25 μg of amphotericin B per ml, and 9% calf serum. COS cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 1 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.25 μg of amphotericin per ml, and 10% fetal bovine serum. COS cells were transiently transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation (4) or FuGENE 6 transfection reagents (Boehringer Mannheim) and assayed 48 h after transfection.

GST fusion protein pull-down assay.

3T3-F442A cells were deprived of serum overnight in DMEM supplemented with 1 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.25 μg of amphotericin per ml, and 1% bovine serum albumin and treated for 10 min with 500 ng of GH per ml. Cells were then rinsed three times with 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4)–150 mM NaCl–1 mM Na3VO4 and solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 10 μg of leupeptin per ml). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Proteins in cell lysates were quantified using the Pierce bicinchoninic assay protein assay reagent and incubated with the indicated immobilized GST fusion protein as described previously (34).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Transfected COS cells were solubilized in lysis buffer. The cell lysates were incubated with the indicated antibody on ice for 2 h. The immune complexes were collected on protein A-agarose (50 μl) during 1 h of incubation at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with washing buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA) and boiled for 5 min in a mixture (80:20) of lysis buffer and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue). The solubilized proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (5 to 12% gradient or 7.5% acrylamide gels). Proteins in the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham) and detected by immunoblotting with the indicated antibody using enhanced chemiluminescence.

In vitro kinase assay.

The in vitro kinase assay was performed as described previously (30). Briefly, JAK2 was immunoprecipitated using αJAK2 from COS cells coexpressing JAK2 and the indicated wild-type and/or mutant SH2-Bβ. After being washed twice with lysis buffer and twice with kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4), αJAK2 immunoprecipitates were incubated at 30°C for 30 min in 50 μl of kinase buffer supplemented with aprotinin (10 μg/ml), leupeptin (10 μg/ml), and 20 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. After the in vitro kinase assay, proteins in the reaction mixture were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and visualized by autoradiography or immunoblotting with αJAK2. In some experiments, the amount of 32P incorporated into JAK2 was quantified. Autoradiographs were scanned using an Agfa or UMAX scanner and Fotolook SA or VistaScan DA software, and results were quantified using the Molecular Analyst image software from Bio-Rad. These values were then normalized for amount of immunoprecipitated JAK2, judged by scanning of αJAK2 immunoblots. Multiple film exposure times were made to ensure that all bands were scanned within the linear range of the film.

Stat5B nuclear localization assay.

3T3-F442A cells were plated on glass coverslips and transfected with Transfast (Promega) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Cells were cotransfected with 1.3 μg of cDNA encoding GFP-Stat5B and either 2.5 μg of control plasmid or plasmid encoding Myc-tagged C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ (amino acids 1 to 555; ΔC555). Following overnight incubation in serum-free medium, cells were stimulated for 40 min with GH (500 ng/ml) where appropriate, fixed (4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] for 15 min at room temperature), and permeabilized (1% Triton X-100 and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature). Nonspecific sites were blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS overnight at 4°C. Myc-tagged truncated SH2-Bβ was visualized by immunostaining using αMyc (1:200) followed by anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-Texas red (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Confocal imaging was performed with a Noran OZ laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a 60× Nikon objective. GFP was excited at 488 nm by a krypton-argon laser, and fluorescence at 500 ± 12 nm was captured. Texas red was excited at 568 nm, and fluorescence above 590 nm captured. The nuclear-to-cytosol GFP fluorescence intensity ratios for 20 cells per condition were calculated as reported previously (12). Data were analyzed using a one-tailed unpaired t test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

SH2-Bβ binds to both active and inactive JAK2.

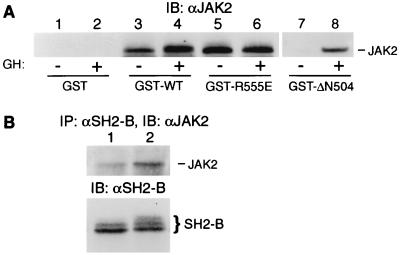

Previous results indicated that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is sufficient for SH2-Bβ to bind to activated JAK2 (34). To examine whether tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 and the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ are required for the interaction between JAK2 and SH2-Bβ, 3T3-F442A cells were treated for 10 min with or without GH (500 ng/ml), a potent stimulator of the activity and tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2. Proteins in cell lysates were incubated with immobilized GST fusion protein containing SH2-Bβ, SH2-Bβ(R555E), which lacks a functional SH2 domain, or the C-terminal 167 amino acids of SH2-Bβ (ΔN504, amino acids 504 to 670), which contain the entire SH2 domain. The bound proteins were eluted and immunoblotted with αJAK2. ΔN504 bound to JAK2 from GH-treated but not control cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 7 and 8), consistent with our previous conclusion that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ binds only to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 present in GH-treated but not control cells (34). Surprisingly, GST–SH2-Bβ bound to JAK2 from both control and GH-treated cells, although it bound less JAK2 from control cells than from GH-treated cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 4). GST–SH2-Bβ(R555E) bound equally well to JAK2 from GH-treated and control cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6), while GST alone did not interact with JAK2 even from GH-treated cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 2). Reprobing the blots with αPY revealed that the JAK2 that bound to GST-ΔN504, GST–SH2-Bβ, or GST–SH2-Bβ(R555E) was tyrosyl phosphorylated in GH-treated cells but not in control cells (data not shown). Consistent with these observations, a small amount of endogenous JAK2 from 3T3-F442A cells coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous SH2-B even in the absence of GH (Fig. 1B). The amount of JAK2 coimmunoprecipitating with SH2-B was substantially increased by GH treatment (Fig. 1B, lane 2). These results indicate that full-length SH2-Bβ can bind to non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 and that at least one site of interaction of SH2-Bβ with non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 most likely lies outside the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ.

FIG. 1.

The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is not required for the interaction of SH2-Bβ with non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. 3T3-F442A cells were stimulated with 500 ng of human GH per ml for 10 min. (A) Cell lysates were incubated with GST or GST fusion protein containing SH2-Bβ (GST-WT), SH2-Bβ(R555E) (GST-R555E), or ΔN504 (GST-ΔN504), as indicated. The precipitated proteins were immunoblotted (IB) with αJAK2. The amount of GST-SH2-Bβ(R555E) used was three times that of GST-SH2-Bβ. (B) Proteins in lysates of cells treated with (lane 2) or without (lane 1) human GH were immunoprecipitated (IP) with αSH2-B and immunoblotted with αJAK2 (top). The blot was reprobed with αSH2-B (bottom).

To obtain further evidence for the existence of a site of interaction between SH2-Bβ and JAK2 that does not involve a functional SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ or phosphorylated tyrosines in JAK2, SH2-Bβ was coexpressed in COS cells with either JAK2 (WT) or kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E). SH2-Bβ was immunoprecipitated with αSH2-B, and the presence of coimmunoprecipitating JAK2 was detected by immunoblotting with αJAK2. As expected, JAK2 (WT) coimmunoprecipitated with SH2-Bβ (Fig. 2, lane 1). Kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) also coimmunoprecipitated with SH2-Bβ, but to a lesser extent (Fig. 2, lane 2). The levels of expression of JAK2 (WT) and kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) were similar, and only JAK2 (WT) was tyrosyl phosphorylated, as assessed by immunoblotting with αJAK2 and αPY, respectively (34) (data not shown). These data suggest that SH2-Bβ interacts with higher affinity with active, tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 than with inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. When SH2-Bβ(R555E) was coexpressed with JAK2 (WT) in COS cells, it coimmunoprecipitated with JAK2 but to a lesser extent than SH2-Bβ (WT) (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). Taken together, our results indicate that in cells, SH2-Bβ binds to both active, tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 and inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. The interaction with active JAK2 most likely involves primarily the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ and phosphorylated tyrosine(s) in JAK2. The interaction with inactive JAK2 most likely involves a site in SH2-Bβ other than the SH2 domain.

FIG. 2.

SH2-Bβ binds more strongly to wild-type, tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 than to kinase-inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2(K882E). COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmid (5 μg) encoding either JAK2 (WT) or kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) (K-E) and plasmid (5 μg) encoding either Myc-tagged SH2-Bβ (WT) or SH2-Bβ(R555E) (R555E). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with αSH2-B and immunoblotted (IB) with αJAK2 (top) or αSH2-B (bottom).

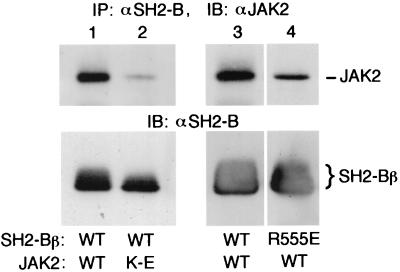

The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is not required for SH2-Bβ to bind to kinase-inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2.

To determine the region(s) of SH2-Bβ responsible for the lower-affinity interaction with non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2, SH2-Bβ was truncated at either the C or N terminus (Fig. 3A) and tagged with a Myc epitope at the N terminus. The SH2-Bβ mutants were individually coexpressed with kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) in COS cells and then immunoprecipitated with αMyc. The immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with αJAK2. ΔN504, which contains the entire SH2 domain and was shown previously to bind to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 (WT) (34), was unable to bind kinase-inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2(K882E) (Fig. 3B, lane 1, top). In contrast, two N-terminal fragments of SH2-Bβ (ΔC631 and ΔC555 [Fig. 3A]) coimmunoprecipitated with JAK2(K882E) (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 3, top). Importantly, the C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ lacking most of its SH2 domain (ΔC555) bound to kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) to a similar extent as ΔC631 that contains the entire SH2 domain (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 3, top). Reprobing the same blot with αMyc revealed that similar amounts of ΔN504, ΔC631, and ΔC555 were expressed and immunoprecipitated by αMyc (Fig. 3B, bottom). These results indicate that an intact SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is neither able to bind to inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 nor required for binding of SH2-Bβ to inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2.

FIG. 3.

SH2-Bβ binds to JAK2 via at least two sites. (A) Schematic representation of SH2-Bβ and various mutants. (B) COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmid (10 μg) encoding kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) (K-E) and plasmid (4 μg) encoding the indicated SH2-Bβ mutant with a Myc tag at the N terminus. Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with αMyc and immunoblotted (IB) with αJAK2 (top). The same blot was reprobed with αMyc (bottom). (C) COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmid (5 μg) encoding ΔC555 and plasmid (5 μg) encoding either JAK2 (WT) or kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) (K-E). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with αMyc and immunoblotted with αJAK2 (top). The same blot was reprobed with αPY (middle) or αMyc (bottom). The positions of migration of JAK2 and SH2-Bβ and SH2-Bβ mutants are noted in panels B and C.

To verify that ΔC555 is able to bind to JAK2 (WT) in addition to kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E), Myc-tagged ΔC555 was coexpressed with JAK2 (WT) or JAK2(K882E) in COS cells. The Myc-tagged ΔC555 was immunoprecipitated with αMyc, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with αJAK2. ΔC555, like SH2-Bβ, coprecipitated with JAK2 (WT) (Fig. 3C, lane 1). When the amounts of JAK2 and JAK2(K882E) coprecipitating with ΔC555 were normalized to levels of expression of ΔC555 (Fig. 3C, bottom), the amounts of ΔC555 coimmunoprecipitating with JAK2 (WT) and kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) were found to be similar. As predicted, JAK2 (WT) but not kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) that coimmunoprecipitated with ΔC555 was phosphorylated on tyrosines (Fig. 3C, middle). Combined with our previous observations (34), these results lead us to conclude that there are at least two binding sites in SH2-Bβ for JAK2. The SH2 domain in the C-terminal region of SH2-Bβ binds phosphotyrosine(s) in JAK2 with a relatively high affinity. A second site, residing in the N-terminal 555 amino acids of SH2-Bβ, binds to JAK2 independent of the kinase activity and tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2.

Multiple regions in SH2-Bβ, including the PH domain, contribute to maximal binding of SH2-Bβ to inactive JAK2.

To identify amino acids in SH2-Bβ responsible for the binding of SH2-Bβ to inactive JAK2, SH2-Bβ mutants with different deletions at the N or C terminus (Fig. 4A) were generated. The SH2-Bβ mutants were tagged with a Myc epitope at their N termini and coexpressed individually with kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) in COS cells. These truncated forms of SH2-Bβ were then immunoprecipitated with αMyc, and immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with αJAK2. Removing the N-terminal 117 (ΔN118) or 268 (ΔN269) amino acids of SH2-Bβ did not decrease their interaction with kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4, top). However, when the PH domain of SH2-Bβ was deleted (ΔN397), the truncated SH2-Bβ lost its ability to interact with JAK2(K882E) (Fig. 4B, lane 5, top), although this mutant SH2-Bβ still retains the entire SH2 domain (Fig. 4A). Further truncation of SH2-Bβ (ΔN504) did not restore binding to JAK2(K882E). This finding is most consistent with maximal interaction between JAK2(K882E) and SH2-B requiring the PH domain. The alternative hypothesis, that truncation of SH2-Bβ alters its three-dimensional structure to a point where it can no longer bind to JAK2 seems less likely, given that ΔN504 is able to bind and activate JAK2 (WT).

FIG. 4.

SH2-Bβ binds to JAK2 via multiple sites. (A) Schematic representation of SH2-Bβ and various mutants. (B) COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmid (10 μg) encoding kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) (K-E) and plasmid (4 μg) encoding the indicated SH2-Bβ mutant containing a Myc tag at the N terminus or the Myc tag alone. Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with αMyc and immunoblotted (IB) with αJAK2 (top). The blots were reprobed with αMyc (bottom). Positions of migration of molecular weight standards (in thousands), JAK2, Myc-SH2-Bβ, and Myc-SH2-Bβ mutants are indicated. Lanes 1 to 6 were from one experiment; lanes 7 to 11 were from a separate experiment. Proteins of approximately 26 kDa detected by αMyc in lanes 3 and 4 are believed to represent proteolytic products of Myc-ΔN118 and Myc-ΔN269, respectively.

To determine whether the PH domain alone is sufficient for binding of SH2-Bβ to kinase inactive JAK2, we determined the effect of deleting C-terminal amino acids on the ability of SH2-Bβ to bind JAK2(K882E). We also tested the ability of the PH domain to bind to JAK2(K882E). Surprisingly, ΔC266 (amino acids 1 to 266), ΔC410 (amino acids 1 to 410), and the PH domain (amino acids 269 to 410) all bound to JAK2(K882E), but to a significantly lesser extent than ΔC555 (amino acids 1 to 555) (Fig. 4B, top). Reprobing the blots with αMyc revealed that similar amounts of the various SH2-Bβ mutants were expressed and immunoprecipitated from the different cells (Fig. 4B, bottom right). Together with results for the N-terminal truncation mutants, these data indicate that the PH domain as well as amino acids 410 to 555 are required for maximal binding of SH2-B to kinase inactive JAK2.

Interestingly, wild-type SH2-Bβ migrated as a diffuse band in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 4B, lane 2, bottom), while two SH2-Bβ mutants migrated as two or more closely migrating but distinct bands (Fig. 4B, lanes 4 and 5, bottom). These different forms of SH2-Bβ are believed to represent different states of phosphorylation, presumably on serines and threonines because they are not recognized by αPY (data not shown). In support of this, treatment with protein phosphatase 2A, which dephosphorylates proteins specifically on serines and threonines, reduced the multiple forms of SH2-Bβ observed in Fig. 4B (lane 2, bottom) to a single form of SH2-Bβ with a faster migration (data not shown).

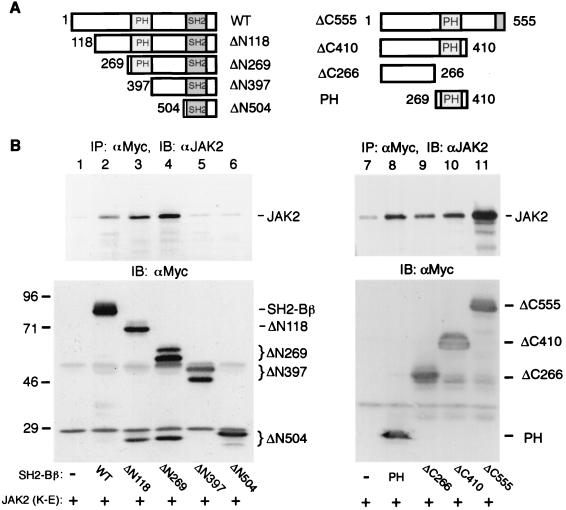

The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is necessary and sufficient for its stimulatory effect on JAK2 and on JAK2-dependent phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699.

We previously reported that SH2-Bβ is a potent activator of JAK2 (30). To identify which region of SH2-Bβ is involved in the activation of JAK2, we examined the stimulatory effect of different truncated SH2-Bβ on JAK2. JAK2 was coexpressed with SH2-Bβ mutants in COS cells, immunoprecipitated with αJAK2, and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay by adding [γ-32P]ATP in Mn2+-containing buffer. JAK2 autophosphorylation has been used previously to measure the kinase activity of JAK2. SH2-Bβ strongly activated JAK2 (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 versus 2, top), consistent with our previous report (23). A similar stimulatory effect on JAK2 was observed for truncated SH2-Bβ lacking N-terminal amino acids 1 to 268 (ΔN269) or 1 to 503 (ΔN504) (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4, top) or C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ lacking amino acids 632 to 670 (ΔC631) (Fig. 5A, lane 5, top). Since only the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ overlaps between ΔN504 and ΔC631 (Fig. 3A), these data suggest that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is sufficient to activate JAK2.

FIG. 5.

The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is sufficient to stimulate JAK2. COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmid (2 μg) encoding JAK2 and plasmid (10 μg) encoding Myc alone (−), Myc-SH2-Bβ (WT), or the indicated Myc-SH2-Bβ mutant. (A) JAK2 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with αJAK2 and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. Proteins in the αJAK2 immunoprecipitates were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose, and visualized by autoradiography (top). The same blot was immunoblotted (IB) with αJAK2 (middle). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoblotted with αMyc (bottom). Note that the bands comigrating with Myc-SH2-Bβ in lane 3, Myc-ΔN269 in lane 4, and Myc-ΔN504 in lane 5 represent a small degree of spillover from the adjacent lane. The dark band migrating just below Myc-Δ504 in lane 3 is believed to be a proteolytic product of Myc-ΔN269 (see Fig. 4B, lane 4). (B) GST-SH2-Bβ (10 μg of protein) was added to αJAK2 immunoprecipitates and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. After the assay, GST-SH2-Bβ was purified using glutathione-agarose beads and visualized by autoradiography.

In contrast, deleting the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ (ΔC555) (Fig. 5A, lane 6, top) or replacing the critical Arg-555 within the FLVR motif of the SH2 domain with Glu abrogated the ability of SH2-Bβ mutants to activate JAK2. Immunoblotting with αJAK2 revealed that similar amounts of JAK2 were used in the individual in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 5A, middle). These results indicate that the SH2 domain is required for the stimulatory effect of SH2-Bβ on JAK2.

To provide additional evidence that SH2-Bβ stimulates the kinase activity of JAK2, we immunoprecipitated JAK2 from COS cells coexpressing JAK2 and various forms of SH2-Bβ. We then assayed the ability of the immunoprecipitated JAK2 to phosphorylate GST-SH2-Bβ in an in vitro kinase assay. GST-SH2-Bβ is unable to active JAK2 by itself in this assay (data not shown). In agreement with the above results assessing JAK2 autophosphorylation, SH2-Bβ (WT) and its mutants with an intact SH2 domain (ΔN269, ΔN504, and ΔC631) (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 to 5) promoted JAK2-induced phosphorylation of GST-SH2-Bβ whereas SH2-Bβ mutants with a defective SH2 domain (ΔC555 and R555E) (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 and 7) did not do so. Thrombin cleavage of the phosphorylated GST-SH2-Bβ revealed that JAK2 phosphorylated SH2-Bβ but not GST under these experimental conditions (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is necessary and sufficient to stimulate the kinase activity of JAK2 and subsequent tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 and other JAK2 substrates.

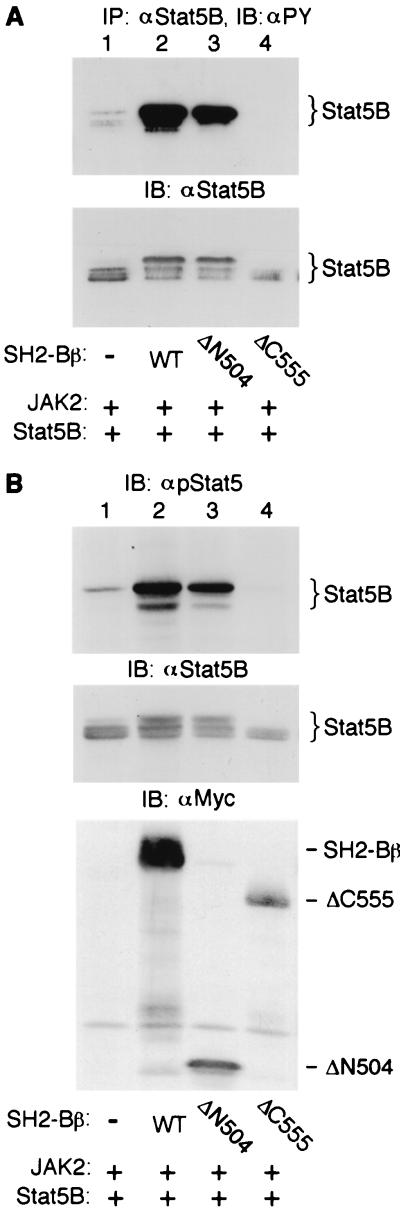

Because the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ plays an obligatory role in activation of JAK2 by SH2-Bβ, we reasoned that the SH2 domain would also play an essential role in SH2-Bβ-promoted tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stats mediated by JAK2. To test this hypothesis, Stat5B and JAK2 were coexpressed with different SH2-Bβ mutants in COS cells. Stat5B was immunoprecipitated with αStat5B and immunoblotted with αPY. Both SH2-Bβ and ΔN504, which have intact SH2 domains, strongly stimulated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 3). In contrast, ΔC555, which lacks the SH2 domain, was unable to stimulate tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B (Fig. 6A, lane 4). Instead, it inhibited tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B (Fig. 6A, lane 4). We have previously shown that SH2-Bβ alone (no JAK2) or SH2-Bβ together with kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E) are unable to stimulate tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B (30). Therefore, the enhancement of tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B by the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is mediated by JAK2.

FIG. 6.

The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is necessary and sufficient for the stimulatory effect of SH2-Bβ on JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B. COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmids encoding JAK2 (0.5 μg), Stat5B (5 μg) and either Myc alone, Myc-SH2-Bβ (WT) (7 μg) or the indicated Myc-SH2-Bβ mutant (7 μg). (A) Stat5B was immunoprecipitated (IP) with αStat5B and immunoblotted (IB) with αPY (top). The same blot was reprobed with αStat5B (bottom). (B) Proteins in cell lysates (40 μg) were immunoblotted with antibody recognizing specifically Stat5 phosphorylated on Tyr-699 (αpStat5; top), αStat5B (middle) or αMyc (bottom).

Tyr-699 in Stat5B is conserved in all Stats and has been shown to be phosphorylated in response to cytokines (5, 11). Phosphorylation of this conserved tyrosine is required for activation of Stats in response to a variety of hormones and cytokines (5). To test whether SH2-Bβ stimulates phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699, an antibody (αpStat5) recognizing specifically Stat5 phosphorylated on Tyr-699 (30) was used for immunoblotting. Stat5B and JAK2 were coexpressed in COS cells with different SH2-Bβ mutants. Proteins in cell lysates were immunoblotted with αpStat5. Both SH2-Bβ and ΔN504 strongly stimulated phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699 (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 to 3, top). In contrast, ΔC555 inhibited phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699 (Fig. 6B, lane 4, top). Reprobing both the αPY blot of αStat5B immunoprecipitates (Fig. 6A) and αpStat5 blot of cell lysates (Fig. 6B) with αStat5B revealed that the expression levels of Stat5B were similar between control cells and cells coexpressing SH2-Bβ or ΔN504 and slightly lower in cells coexpressing ΔC555 (Fig. 6A, bottom; Fig. 6B, middle). Coexpression of SH2-Bβ or ΔN504 also caused an upward shift in the mobility of Stat5B (Fig. 6A, bottom; Fig. 6B, middle), correlating with the increased tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B. Previous work suggests that serine/threonine phosphorylation also contributes to the multiple forms of Stat5B (12) observed in Fig. 6. The ability of different SH2-Bβ mutants to stimulate tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B correlates with their ability to stimulate JAK2 (Fig. 5A). The data in Fig. 6 therefore suggest that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is necessary and sufficient for the stimulatory effect of SH2-Bβ on phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699 mediated by JAK2.

A C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ lacking the SH2 domain acts as a dominant negative mutant to inhibit JAK2 and JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B.

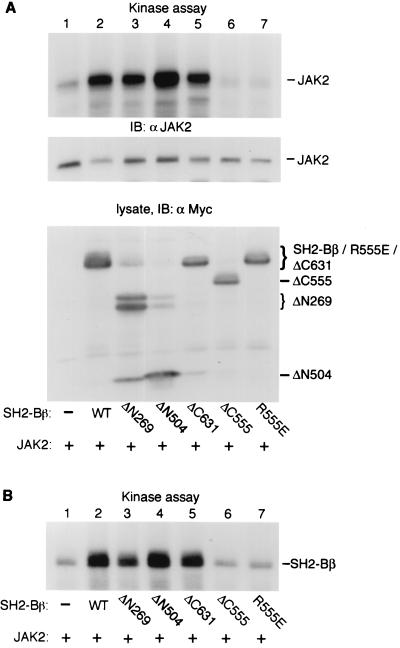

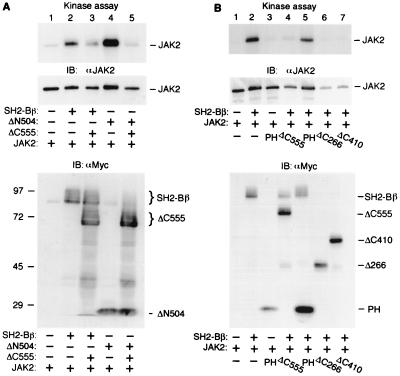

Data in Fig. 5 and 6 raise the possibility that binding to JAK2 of regions in SH2-Bβ other than the SH2 domain inhibits JAK2 activity. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether overexpression of ΔC555, which lacks most of the SH2 domain, interferes with the activation of JAK2 by SH2-Bβ or ΔN504. JAK2 was coexpressed in COS cells with SH2-Bβ or ΔN504 in the presence or absence of ΔC555, immunoprecipitated with αJAK2, and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. Both SH2-Bβ (WT) and ΔN504 stimulated JAK2 (Fig. 7A, lanes 2 and 4, top), consistent with Fig. 5. Overexpression of ΔC555 significantly inhibited the activation of JAK2 induced by SH2-Bβ (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 versus 2, top). When the amount of 32P incorporated into JAK2 was quantified by scanning and normalized to levels of JAK2 immunoprecipitated as judged by αJAK2 immunoblotting, ΔC555 was estimated to inhibit SH2-Bβ by greater than 55% (n = 3). Surprisingly, overexpression of ΔC555 almost abolished the activation of JAK2 by ΔN504 (Fig. 7A, lanes 1, 4, and 5, top). Overexpression of ΔC555 did not change significantly the level of expression of JAK2 (Fig. 7A, middle), SH2-Bβ, or ΔN504 (Fig. 7A, bottom). These results strongly support the conclusion that amino acids 1 to 555 of SH2-Bβ bind and inhibit JAK2.

FIG. 7.

Amino acids 1 to 555 of SH2-Bβ inhibit JAK2. (A) COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmids (2 μg) encoding JAK2 and either Myc-SH2-Bβ, Myc-ΔN504, or Myc alone in the presence of plasmids (10 μg) encoding Myc-ΔC555 or Myc alone. JAK2 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with αJAK2, subjected to an in vitro kinase assay, and visualized by autoradiography (top) or immunoblotting (IB) with αJAK2 (middle) as described for Fig. 5A. Proteins (30 μg) in cell lysates were immunoblotted with αMyc (bottom). (B) COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmids (2 μg) encoding JAK2 and/or Myc-SH2-Bβ or Myc alone in the presence or absence of plasmids (9 μg) encoding Myc-ΔC555, Myc-PH, Myc-ΔC266, Myc-ΔC410, or Myc alone as indicated. JAK2 was immunoprecipitated with αJAK2, subjected to an in vitro kinase assay, and visualized by autoradiography (top) or immunoblotting with JAK2 (middle panel). Proteins (30 μg) in cell lysates were immunoblotted with Myc (bottom). The migration of molecular weight standards (in thousands), JAK2, SH2-Bβ and SH2-Bβ mutants is indicated.

To map further the regions in SH2-Bβ that inhibit JAK2, JAK2 was coexpressed in COS cells with different mutant SH2-Bβs in the presence or absence of SH2-Bβ (WT), immunoprecipitated with αJAK2, and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. Figure 7B (lanes 4 versus 2, top) again illustrates that ΔC555 substantially inhibits the SH2-Bβ-induced activation of JAK2. When results from three separate experiments were normalized to levels of immunoprecipitated JAK2 (Fig. 7B, middle), the PH domain alone was found to inhibit SH2-Bβ-stimulated JAK2 kinase activity by an estimated average of 35%. In experiments not shown, coexpression of the PH domain with JAK2 also inhibited the in vitro kinase activity of JAK2 in cells that did not overexpress SH2-Bβ (WT). When levels of 32P incorporation into JAK2 were normalized to levels of immunoprecipitated JAK2, overexpression of the PH domain was found to inhibit JAK2 activity by an average 35% (four separate experiments). Unfortunately, we were not able to assess the inhibitory effects of amino acids 1 to 266 or 1 to 410 on JAK2 because they decreased expression of JAK2 and blocked expression of SH2-B (WT) (Fig. 7B, lanes 6 and 7, middle and bottom). Taken together, these results indicate that the PH domain may contribute to the inhibitory effect of amino acids 1 to 555 (ΔC555) on JAK2, but that other amino acids are required for a maximal inhibitory effect.

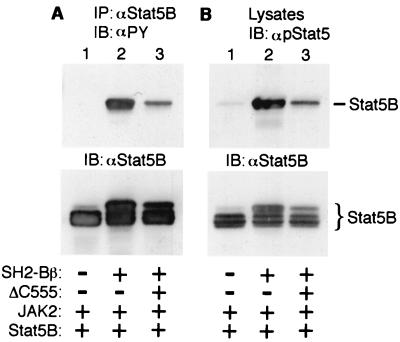

To examine whether ΔC555 inhibits JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B, Stat5B and JAK2 were coexpressed in COS cells with SH2-Bβ in the presence or absence of ΔC555. Stat5B was immunoprecipitated with αStat5B and immunoblotted with αPY. SH2-Bβ dramatically enhanced JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B (Fig. 8A, lane 2), consistent with previous data (30). Overexpression of ΔC555 significantly inhibited tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B (Fig. 8A, lanes 3 versus 2). When proteins in cell lysates were immunoblotted with αpStat5, ΔC555 was observed to reduce significantly the amount of Stat5B phosphorylated on Tyr-699 (Fig. 8B, lanes 3 versus 2).

FIG. 8.

C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ without a functional SH2 domain (ΔC555) inhibits phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699 by JAK2. COS cells were cotransfected transiently with plasmids encoding JAK2 (0.4 μg), Stat5B (5 μg), SH2-Bβ (2 μg), or ΔN504 (2 μg) in the presence or absence of ΔC555 (10 μg) as indicated. (A) Stat5B was immunoprecipitated (IP) with αStat5B and immunoblotted (IB) with αPY (top). The same blot was reprobed with αStat5B (bottom). (B) Proteins in cell lysates (40 μg) were immunoblotted with antibody recognizing specifically Stat5 phosphorylated on Tyr-699 (αpStat5; top). The same blot was reprobed with αStat5B (bottom).

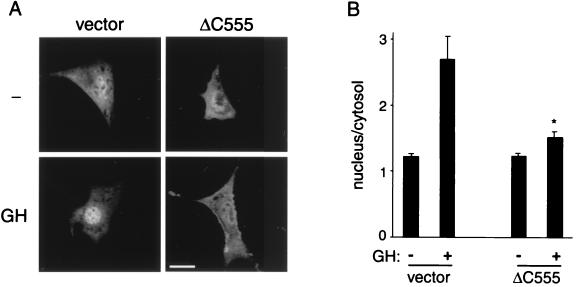

ΔC555 inhibits GH-stimulated nuclear accumulation of Stat5B.

To determine whether ΔC555 acts as a dominant negative mutant to inhibit ligand-stimulated activation of Stat5B mediated by endogenous JAK2, GFP-tagged Stat5B was transiently coexpressed in 3T3-F442A cells with ΔC555 and visualized by confocal microscopy. A GFP tag has been used successfully to monitor the migration of Stat5B in response to GH (12). In control cells, GH stimulated activation and accumulation of GFP-Stat5B in the nucleus (Fig. 9), as reported previously (12). In contrast, overexpression of ΔC555 dramatically inhibited GH-stimulated accumulation of GFP-Stat5B in the nucleus (Fig. 9). These data indicate that ΔC555 inhibits ligand-stimulated activation of Stat5B by endogenous receptor and JAK2.

FIG. 9.

C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ without a functional SH2 domain (ΔC555) acts as a dominant negative to inhibit GH-stimulated nuclear migration of Stat5B. 3T3-F442A cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding GFP-Stat5B (1 μg) and plasmid (2.5 μg) encoding either Myc alone (vector) or Myc-ΔC555. Cells were then treated with or without 500 ng of GH per ml for 40 min. (A) Representative confocal images of cells. Scale bar represents 20 μm. (B) Nucleus-to-cytosol GFP fluorescence intensity ratios. Bars represent the mean ± SEM ratio of 20 cells per condition. ∗, significantly different from GH-treated cells transfected with empty vector (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

We originally identified SH2-Bβ as a JAK2-interacting protein in a yeast two-hybrid assay (34). In the present study, we provide evidence that SH2-Bβ interacts with JAK2 via at least two sites: the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ, which presumably binds to one or more phosphorylated tyrosines within activated JAK2, and a site(s) within or encompassing amino acids 1 to 555 of SH2-Bβ which can bind to non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated, inactive JAK2. We showed previously that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ alone is sufficient to bind to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 (34). Here we extend this earlier observation and establish that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is the primary binding site between SH2-Bβ and tyrosyl-phosphorylated, active JAK2 in cells. In support of this, we showed that GST-ΔN504, which contains only the SH2 domain and C-terminal 49 amino acids of SH2-Bβ, binds only to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. SH2-Bβ coimmunoprecipitates with tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 to a much greater extent than with non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2(K882E). Finally, when the critical Arg-555 within the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is replaced by Glu, the binding of the mutant SH2-Bβ to JAK2 is reduced dramatically.

We also provide substantial evidence showing that in addition to the SH2 domain, SH2-Bβ has another site(s) that binds to JAK2; binding via this additional site(s) is of lower affinity and does not require tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2. First, we show that GST–SH2-Bβ is able to bind to non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2, although to a lesser extent than to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. Second, GST–SH2-Bβ(R555E) with a defective SH2 domain binds similarly to tyrosyl-phosphorylated and non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2, at a level substantially reduced compared to binding of GST-SH2-Bβ to tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. Third, when coexpressed with kinase-inactive JAK2(K882E), both SH2-Bβ and SH2-Bβ(R555E) coimmunoprecipitate with non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2(K882E). Similarly, C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ (ΔC555), which lacks most of the SH2 domain, coimmunoprecipitates similarly with wild-type, tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 and kinase-inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2(K882E). These results clearly demonstrate that in addition to the SH2 domain, SH2-Bβ has one or more additional sites residing within the N-terminal 555 amino acids of SH2-Bβ that bind to JAK2 independent of tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2.

The N-terminal part of SH2-Bβ that contains the additional JAK2 binding site(s) contains a PH domain, multiple proline-rich motifs, and numerous potential phosphorylation sites. Experiments using N-terminal deletion mutants of SH2-Bβ indicated that the PH domain is necessary for binding inactive JAK2 whereas amino acids 1 to 269 are not. They also indicated that amino acids 410 to 638 are not sufficient for binding to inactive JAK2. Experiments using C-terminal deletion mutants of SH2-Bβ and the PH domain alone revealed that the PH domain of SH2-Bβ, the first 269 amino acids of SH2-Bβ, and the first 410 amino acids can bind to inactive, non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. However, all three bind significantly less well than amino acids 1 to 555. Taken together, these data with both sets of mutants indicate that both the PH domain and amino acids 410 to 555 are required for maximal binding of SH2-Bβ to inactive JAK2. PH domains are widely believed to mediate the interaction of signaling molecules containing a PH domain with phospholipids on the plasma membrane and recruit these signaling molecules to the plasma membrane (8, 10, 17). If the interaction of the PH domain of SH2-Bβ with JAK2 observed in this study turns out to be a direct interaction, rather than one mediated via phospholipids, it would represent one of a few examples of PH domain-mediated protein-protein interactions identified to date (3, 16, 28, 42).

We have previously shown that SH2-Bβ is a potent activator of JAK2 (30). In this study, we demonstrate that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is not only required but also sufficient for the stimulatory action of SH2-Bβ on JAK2. Coexpression of SH2-Bβ with JAK2 stimulates the kinase activity of JAK2, as assessed by an in vitro kinase assay of JAK2 autophosphorylation and JAK2 phosphorylation of GST-SH2-Bβ. It also enhances dramatically JAK2-mediated phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699, a physiological cytokine-induced phosphorylation site in cells. When the critical Arg-555 within the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is replaced with Glu, or the SH2 domain is deleted (ΔC555), the resultant SH2-Bβ mutants are unable to activate JAK2 and stimulate JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699. In contrast, two other truncated SH2-Bβ mutants, ΔN504 and ΔC631, both of which contain the entire SH2 domain, are fully capable of activating JAK2 and enhancing JAK2-mediated phosphorylation of Stat5B on Tyr-699. The only region shared by ΔN504 and ΔC631 is the SH2 domain. Therefore, the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ appears to be necessary and sufficient for the stimulatory action of SH2-Bβ on JAK2 kinase activity. Because the SH2 domain is conserved in all three isoforms of known SH2-B (α, β, and γ), we believe that all three isoforms of SH2-B are able to stimulate JAK2 activity.

The mechanism by which SH2-Bβ activates JAK2 is unclear. One possibility is that interaction of SH2-Bβ via its SH2 domain with JAK2 causes a change in conformation of JAK2 that stabilizes JAK2 in an active state. Alternatively, the binding of the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ to a critical phosphorylated tyrosine in JAK2 protects this tyrosine from being dephosphorylated by tyrosine phosphatase(s). Dephosphorylation of this critical tyrosine may lead to inactivation of JAK2. A third possibility is that SH2-Bβ prevents the binding of SOCS-1/JAB or another inhibitory protein to JAK2. SOCS-1/JAB, a member of the SOCS family, has been shown to bind via its SH2 domain to a phosphotyrosine within the activation loop in the kinase domain of JAK2 and inhibit JAK2 (24, 44). The finding that SH2-Bβ has multiple binding sites for JAK2 raises the possibility that SH2-Bβ activates JAK2 by causing dimerization of JAK2 (i.e., one site in SH2-B binds to one JAK2, and a second site in the same SH2-B binds to a second JAK2). However, this latter explanation does not explain why ΔN504, which lacks the site that binds to inactive JAK2, is a potent activator of JAK2.

An interesting finding of this study is that ΔC555, a C-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ that contains the PH domain and several proline-rich domains but lacks most of the SH2 domain, inhibits the kinase activity of JAK2, JAK2-mediated tyrosyl phosphorylation of Stat5B, and JAK2-mediated movement of Stat5B to the nucleus in response to GH. One can envision this dominant negative effect of ΔC555 as a consequence of ΔC555 competing with endogenous SH2-Bβ for binding to the low-affinity site of interaction in JAK2, thereby decreasing the ability of endogenous SH2-Bβ to bind via its SH2 domain to JAK2 and preventing activation of JAK2. Because ΔC555 inhibits the activation of JAK2 not only by SH2-Bβ but also by ΔN504, an N-terminally truncated SH2-Bβ that shares only 51 amino acids with ΔC555, one can also envision binding of the low-affinity site of SH2-B to JAK2 actually inhibiting JAK2. Consistent with this, the PH domain alone inhibits the activity of overexpressed JAK2, in the absence of overexpressed SH2-Bβ.

Based on our data, we propose the following model by which SH2-Bβ regulates JAK2. In the basal state, SH2-Bβ binds via a site(s) in its N-terminal 555 amino acids to non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2 with a relatively low affinity and inhibits spontaneous, abnormal activation of JAK2. This interaction also increases the subcellular local concentration of SH2-Bβ around JAK2. When JAK2 is partially activated and tyrosyl phosphorylated in response to hormones and cytokines, the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is then able to bind rapidly with high affinity to phosphorylated tyrosine(s) in JAK2, thereby rapidly and robustly enhancing JAK2 activity. SH2-Bβ is phosphorylated on tyrosines as well as on serines and threonines in response to a variety of growth factors, cytokines, and hormones (31–34). It is appealing to hypothesize that differential phosphorylation of SH2-Bβ may affect its ability to bind and/or activate JAK2.

In summary, we show that SH2-Bβ binds to JAK2 via at least two sites. One or more sites within the first 555 amino acids of SH2-Bβ binds to JAK2 independent of tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 and inhibits JAK2. The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ binds only to activated JAK2, presumably to phosphorylated tyrosine(s). This latter interaction is necessary and sufficient for SH2-Bβ to stimulate JAK2. The inhibition of JAK2 mediated by the low-affinity interaction of JAK2 with SH2-Bβ or its related molecules may serve as a checkpoint to prevent abnormal activation of JAK2 in the absence of ligand. In addition, the accumulation of SH2-Bβ around JAK2 due to this low-affinity interaction of SH2-Bβ with inactive JAK2 may increase the efficiency with which the SH2 domain is able to bind and activate JAK2. This allows for a more rapid and robust response of cells to hormones and cytokines that utilize JAK2 in their signaling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1-DK34171 and RO1-DK54222. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Biomedical Research Core Facilities, University of Michigan, and supported in part by NIH grants to the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA46592), Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60-DK-20572), and University of Michigan Multipurpose Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases Center (P60-AR20557).

We thank M. Stofega, L. Argetsinger, J. Kouadio, and K. O'Brien for helpful discussions. We thank X. Wang for technical assistance and B. Hawkins for assistance with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Argetsinger L S, Carter-Su C. Mechanism of signaling by growth hormone receptor. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:1089–1107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bromberg J F, Horvath C M, Wen Z, Schreiber R D, Darnell J E., Jr Transcriptionally active Stat1 is required for the antiproliferative effects of both interferon α and interferon γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7673–7678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burks D J, Wang J, Towery H, Ishibashi O, Lowe D, Riedel H, White M F. IRS pleckstrin homology domains bind to acidic motifs in proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31061–31067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darnell J E., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duhe R J, Evans G A, Erwin R A, Kirken R A, Cox G W, Farrar W L. Nitric oxide and thiol redox regulation of Janus kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:126–131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endo T A, Masuhara M, Yokouchi M, Suzuki R, Sakamoto H, Mitsui K, Matsumoto A, Tanimura S, Ohtsubo M, Misawa H, Miyazaki T, Leonor N, Taniguchi T, Fujita T, Kanakura Y, Komiya S, Yoshimura A. A new protein containing an SH2 domain that inhibits JAK kinases. Nature. 1997;387:921–924. doi: 10.1038/43213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falasca M, Logan S K, Lehto V P, Baccante G, Lemmon M A, Schlessinger J. Activation of phospholipase Cγ by PI 3-kinase-induced PH domain-mediated membrane targeting. EMBO J. 1998;17:414–422. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng J, Witthuhn B A, Matsuda T, Kohlhuber F, Kerr I M, Ihle J N. Activation of Jak2 catalytic activity requires phosphorylation of Y1007 in the kinase activation loop. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2497–2501. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke T F, Kaplan D R, Cantley L C. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouilleux F, Wakao H, Mundt M, Groner B. Prolactin induces phosphorylation of Tyr694 of Stat5 (MGF), a prerequisite for DNA binding and induction of transcription. EMBO J. 1994;13:4361–4369. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrington J, Rui L, Luo G, Yu-Lee L-Y, Carter-Su C. A functional DNA-binding domain is required for growth hormone-induced nuclear localization of Stat5B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5138–5145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ihle J N. Janus kinases in cytokine signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 1996;B351:159–166. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ihle J N. The Janus protein tyrosine kinase family and its role in cytokine signaling. Adv Immunol. 1995;60:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ihle J N. STATs: signal transducers and activators of transcription. Cell. 1996;84:331–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Y, Ma W, Wan Y, Kozasa T, Hattori S, Huang X Y. The G protein Gα12 stimulates Bruton's tyrosine kinase and a rasGAP through a conserved PH/BM domain. Nature. 1998;395:808–813. doi: 10.1038/27454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemmon M A, Ferguson K M, Schlessinger J. PH domains: diverse sequences with a common fold recruit signaling molecules to the cell surface. Cell. 1996;85:621–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Robinson G W, Wagner K U, Garrett L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hennighausen L. Stat5a is mandatory for adult mammary gland development and lactogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:179–186. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meraz M A, White J M, Sheehan K C, Bach E A, Rodig S J, Dighe A S, Kaplan D H, Riley J K, Greenlund A C, Campbell D, Carver-Moore K, DuBois R N, Clark R, Aguet M, Schreiber R D. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell. 1996;84:431–442. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minami M, Inoue M, Wei S, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Kishimoto T, Akira S. STAT3 activation is a critical step in gp130-mediated terminal differentiation and growth arrest of a myeloid cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3963–3966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naka T, Narazaki M, Hirata M, Matsumoto T, Minamoto S, Aono A, Nishimoto N, Kajita T, Taga T, Yoshizaki K, Akira S, Kishimoto T. Structure and function of a new STAT-induced STAT inhibitor. Nature. 1997;387:924–929. doi: 10.1038/43219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakajima K, Yamanaka Y, Nakae K, Kojima H, Ichiba M, Kluchi N, Kitaoka T, Fukada T, Hibi M, Hirano T. A central role for Stat3 in IL-6-induced regulation of growth and differentiation in M1 leukemia cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:3651–3658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelms K, O'Neill T J, Li S, Hubbard S R, Gustafson T A, Paul W E. Alternative splicing, gene localization, and binding of SH2-B to the insulin receptor kinase domain. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:1160–1167. doi: 10.1007/s003359901183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson S E, Willson T A, Farley A, Starr R, Zhang J G, Baca M, Alexander W S, Metcalf D, Hilton D J, Nicola N A. Mutational analyses of the SOCS proteins suggest a dual domain requirement but distinct mechanisms for inhibition of LIF and IL-6 signal transduction. EMBO J. 1999;18:375–385. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osborne M A, Dalton S, Kochan J P. The yeast tribrid system—genetic detection of trans-phosphorylated ITAM-SH2-interactions. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:1474–1478. doi: 10.1038/nbt1295-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellegrini S, Dusanter-Fourt I. The structure, regulation and function of the Janus kinases (JAKs) and the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:615–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian X, Riccio A, Zhang Y, Ginty D D. Identification and characterization of novel substrates of Trk receptors in developing neurons. Neuron. 1998;21:1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebecchi M J, Scarlata S. Pleckstrin homology domains: a common fold with diverse functions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:503–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riedel H, Wang J, Hansen H, Yousaf N. PSM, an insulin-dependent, pro-rich, PH, SH2 domain containing partner of the insulin receptor. J Biochem. 1997;122:1105–1113. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rui L, Carter-Su C. Identification of SH2-Bβ as a potent cytoplasmic activator of the tyrosine kinase Janus kinase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7172–7177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rui L, Carter-Su C. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates the association of SH2-Bβ with PDGF receptor and phosphorylation of SH2-Bβ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21239–21245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rui L, Herrington J, Carter-Su C. SH2-B, a membrane-associated adapter, is phosphorylated on multiple serines/threonines in response to nerve growth factor by kinases within the MEK/ERK cascade. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26485–26492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rui L, Herrington J B, Carter-Su C. SH2-B is required for nerve growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10490–10494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rui L, Mathews L S, Hotta K, Gustafson T A, Carter-Su C. Identification of SH2-Bβ as a substrate of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 involved in growth hormone signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6633–6644. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimoda K, van Deursen J, Sangster M Y, Sarawar S R, Carson R T, Tripp R A, Chu C, Quelle F W, Nosaka T, Vignali D A, Doherty P C, Grosveld G, Paul W E, Ihle J N. Lack of IL-4-induced Th2 response and IgE class switching in mice with disrupted Stat6 gene. Nature. 1996;380:630–633. doi: 10.1038/380630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn B, Quelle F W, Cleveland J L, Yi T, Ihle J N. Structure of the murine JAK2 protein-tyrosine kinase and its role in interleukin 3 signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8429–8433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starr R, Willson T A, Viney E M, Murray L J, Rayner J R, Jenkins B J, Gonda T J, Alexander W S, Metcalf D, Nicola N A, Hilton D J. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature. 1997;387:917–921. doi: 10.1038/43206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Yoshida N, Takeda J, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Stat3 activation is responsible for IL-6-dependent T cell proliferation through preventing apoptosis: generation and characterization of T cell-specific Stat3-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:4652–4660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teglund S, McKay C, Schuetz E, van Deursen J M, Stravopodis D, Wang D, Brown M, Bodner S, Grosveld G, Ihle J N. Stat5a and Stat5b proteins have essential and nonessential, or redundant, roles in cytokine responses. Cell. 1998;93:841–850. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thierfelder W E, van Deursen J M, Yamamoto K, Tripp R A, Sarawar S R, Carson R T, Sangster M Y, Vignali D A, Doherty P C, Grosveld G C, Ihle J N. Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature. 1996;382:171–174. doi: 10.1038/382171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Udy G B, Towers R P, Snell R G, Wilkins R J, Park S H, Ram P A, Waxman D J, Davey H W. Requirement of STAT5b for sexual dimorphism of body growth rates and liver gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7239–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldron R T, Iglesias T, Rozengurt E. The pleckstrin homology domain of protein kinase D interacts preferentially with the eta isoform of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9224–9230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Riedel H. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and insulin receptor association with a Src homology-2 domain-containing putative adapter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3136–3139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yasukawa H, Misawa H, Sakamoto H, Masuhara M, Sasaki A, Wakioka T, Ohtsuka S, Imaizumi T, Matsuda T, Ihle J N, Yoshimura A. The JAK-binding protein JAB inhibits Janus tyrosine kinase activity through binding in the activation loop. EMBO J. 1999;18:1309–1320. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]