Abstract

Work is a key social determinant of population health and well-being. Yet, efforts to improve worker well-being in the United States are often focused on changing individual health behaviors via employer wellness programs. The COVID-19 health crisis has brought into sharp relief some of the limitations of current approaches, revealing structural conditions that heighten the vulnerability of workers and their families to physical and psychosocial stressors.

To address these gaps, we build on existing frameworks and work redesign research to propose a model of work redesign updated for the 21st century that identifies strategies to reshape work conditions that are a root cause of stress-related health problems. These strategies include increasing worker schedule control and voice, moderating job demands, and providing training and employer support aimed at enhancing social relations at work.

We conclude that work redesign offers new and viable directions for improving worker well-being and that guidance from federal and state governments could encourage the adoption and effective implementation of such initiatives. (Am J Public Health. 2021;111(10):1787–1795. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306283)

Work is a key social determinant of population health and well-being. Work directly and indirectly shapes inequities in health and well-being by providing opportunities for economic attainment, access to benefits (including health care in the United States), and physical and social environments that profoundly shape health-relevant exposures. It is the place where most adults spend the majority of their waking hours.1 Substantial research documents the health benefits of work, including not only income but also engagement, personal growth, opportunities for learning, and having a sense of purpose and meaning.2

However, the COVID-19 crisis has sharply reminded the public that workplaces are sources of many important exposures that can harm health, including not only viruses, contaminants, and other physical risks but also significant psychosocial stressors. As COVID-19 reveals in painful detail, such exposures are not trivial and how work is designed and organized matters enormously. Moreover, work contributes to the long-observed social gradient in health in the United States, with unhealthy work conditions being more common (and health-enhancing conditions less common) among socially disadvantaged populations.3,4 During the pandemic, workplace COVID-19 outbreaks have occurred primarily among low-wage workers and migrant populations in industries ranging from agriculture to food processing and manufacturing. Research conducted before and during COVID-19 has consistently demonstrated that exposure to adverse workplace conditions (e.g., job insecurity, long hours) leads to poorer physical and mental health for individual workers and their families and communities.5

Despite the importance of work as a social determinant of health, our current ways of pursuing worker well-being are limited. Recent discussions related to improving worker health have focused largely on health promotion or “corporate wellness” programs, which use workplaces as venues for facilitating individual behavior change (e.g., increased exercise, practicing mindfulness). Such programs are problematic for several reasons. For example, they largely overlook the fundamental role of the work environment itself in shaping health. Also, they rest on the assumption that employees can and should manage stressful work conditions by engaging in personal wellness activities, thereby suggesting that employee stress is self-imposed.

Beyond these concerns, such approaches seem to be ineffective, with recent rigorous research revealing small or null effects for these programs on a wide range of employee health outcomes, medical expenditures, and productivity measures.6,7 These findings, together with an understanding that the social organization of work directly and indirectly influences worker health and well-being, suggest that it is time for a new perspective.8

In an important commentary, Schulte et al.9 identified organizational conditions of the workplace as critical determinants of workforce well-being and argued for a broader definition of worker well-being beyond the traditional scope of occupational health. Recent National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) initiatives drawing on the Total Worker Health paradigm explicitly recognize that workplace conditions affect worker health, safety, and well-being through multiple pathways and that organizational environments may act synergistically with other health promotion efforts.10–12 Guidelines and frameworks from Total Worker Health highlight how workplace factors affect worker well-being and identify successes with interventions derived from this approach.10 Here we propose a work redesign approach that builds on these perspectives but explicitly shifts the focus from asking workers to adapt to their work environment regardless of how work is organized to reshaping work conditions and environments in ways that support employee well-being and improve population health.

Our redesign approach promotes identification of work conditions that affect well-being and is informed by (1) an understanding of the changing demographics of workers and working families and (2) an expanded view of health considering the full spectrum of well-being, including both negative and positive dimensions. This approach orients analyses to the everyday organization of work, with dual aims of enabling individuals to work productively and promoting health and well-being. An organizational approach to changing worker well-being is not new. A major focus on the health effects of psychosocial work environments emerged in the 1970s.13 Since then, the “job strain model” has become highly influential in occupational health, linking the combination of high work demands with low job control and low social support to poor health and greater stress.14 Although these ideas continue to be important, dramatic changes in the day-to-day organization of work, workforce demographics, and the relationship between labor and capital occurring in recent decades are less well accommodated by the original model.

Technological advances, global competition, and employers’ strategic responses to pressures from financial markets have radically transformed the nature of work in many organizations. For example, new technologies present employers with increased capacities to monitor and “control” the pace of work, simultaneously creating less discretion for workers in decision making. With the dominance of shareholder-centric business models and the declining power of unions in recent decades, employers have achieved greater flexibility and reduced labor costs through organizational restructuring, downsizing, outsourcing, and a shift to “nonstandard” employment contracts (i.e., temporary, contingent, and gig work).15–17 These changes have eroded the more stable working conditions of the mid-20th century. Furthermore, many workplaces are increasingly diversified according to race, gender, ethnicity, and age.5 In light of these changes, updating and renewing existing models of work and health is essential.

Three key dimensions of the job strain model—job demands, control, and social support—remain highly relevant to worker well-being. By considering these dimensions in light of current workplace conditions, we develop a more refined understanding of ways in which demands, control, and support influence worker well-being today. For instance, the job strain model defines control in terms of having the freedom to decide how to perform and organize tasks. However, less emphasized is where and when people work. With technology and other changes in the nature of work, where people work (home or workplace) and when have become more variable, and therefore new areas related to control must be addressed.

In addition, this model focuses primarily on psychosocial conditions in the workplace. It does not address other key features of the work environment that also significantly affect worker well-being (e.g., physical hazards, wages and benefits) or the ways in which the organization affects systems outside of the workplace (e.g., community or environment). Thus, efforts to understand the effects of work conditions on worker well-being must look beyond even an updated job strain model.

Here we present a work design for health framework and highlight evidence-based work redesign strategies focused on organizational and group-level changes to improve worker well-being. Although highly valuable, we did not consider individual- or leader-level interventions because they are less clearly focused on primary prevention and changing workplace conditions. Our framework is informed by key findings from a systematic review of experimental research on work redesign for worker well-being8 and by a review of relevant nonexperimental research.

UPDATING THE JOB STRAIN MODEL

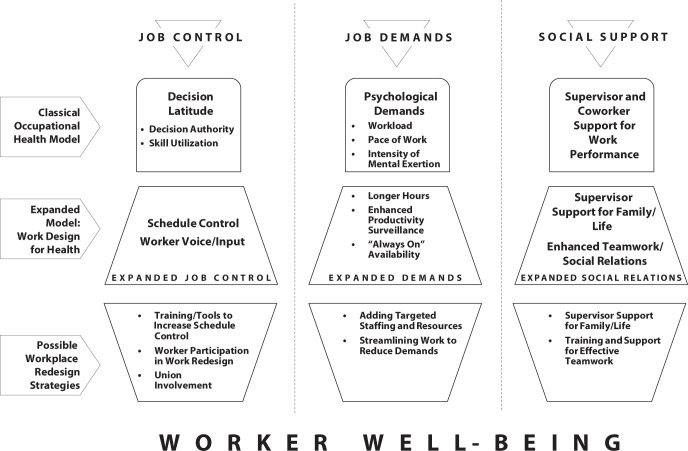

Figure 1 provides an overview of the original job strain model, our proposed updates to each of its three dimensions (i.e., the work design for health model), and examples of evidence-based workplace redesign strategies that effectively target expanded aspects of the framework.

FIGURE 1—

Work Design for Health: Updating the Classical Occupational Health Model

Source. Authors’ update and expansion of the classical occupational health model.

Job Control: Expanding to New Forms

The level of discretion workers exercise over daily work tasks (i.e., job control) is a powerful lever for enhancing health and well-being.14 The job strain model defines job control as the level of autonomy workers have over how they do their work, including autonomy in task-related decisions (“decision authority”) and opportunities to use a wide range of job skills (“skill utilization”). Schedule control, or autonomy over when and where work happens, is also important. One aspect of schedule control is schedule flexibility, or the extent to which workers can vary their working time (e.g., start and end times, time off) and work location (i.e., office or home) to manage the work–life balance more effectively. Recent surveys document unmet needs for schedule flexibility among workers, with the strongest needs among single mothers and those with primary caregiving responsibilities.15 Stress associated with managing the needs of both work and family has well-documented health consequences, including hypertension, sleep difficulties, and other health problems.18

A second aspect of schedule control is schedule predictability. Particularly relevant for low-wage workers, predictability provides stable schedules (i.e., quantity or timing of hours worked), making it possible to coordinate the demands of work with life outside of work and to have a more predictable income. Employers in service industries are increasingly using scheduling software to make “just-in-time” adjustments to workers’ shifts, with hours cut or extended at a moment’s notice. These practices purportedly save labor costs but can harm workers, as they are associated with adverse mental and physical health and poor family functioning.16

Worker voice is another important element of job control. Worker voice goes beyond task autonomy and captures the broader ability of employees to influence their work conditions. Alternative channels for worker voice are needed given the relatively weak nature of US federal labor policies and the fact that union membership has shrunk by about half since the 1980s, to 11% of US workers.19 In a recent national survey, nearly 50% of nonunion workers reported that they would vote for a union, suggesting a sizable gap between workers’ desired and actual voice in US workplaces today.20

Job Demands: Expanding to Reflect Intensification

Significant and broad-based intensification of work has occurred since the 1970s. Individuals are working faster and harder and are more likely to say they have “too much work to do everything well.”15(p157) Whereas the original job strain theory characterized demands according to how fast work needs to be done and how difficult it is,14 intensification of work is accompanied by a proliferation of new kinds of demands.

First, some employees are working longer hours than ever before, primarily driven by expanding workloads. The upswing in “overwork” among some workers largely results from downsizing and lean staffing trends among white-collar professionals;21 however, because of employers’ increased use of mandatory overtime, some blue-collar and low-wage service workers are working longer as well.22 Long work hours are associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and heightened work–family conflicts.18,23

Second, low-wage blue-collar and service workers are experiencing intensified time pressure as a result of the enhanced surveillance made possible by new technologies. For example, technology for tracking productivity increases the pressure to work quickly by gathering information on individuals’ performance in real time.24

Third, work demands have become increasingly unbounded by time and place. New communication technologies permit constant connectivity, and, combined with lean staffing trends, employers often expect white-collar workers to be available for work anywhere at any time.21 For lower-wage workers, just-in-time scheduling creates a similar unbounded effect, with unpredictable schedules and increased pressure to be available at any time.16 If work redesign efforts are to be effective, they must tame excessive work demands and increase worker autonomy and support.

Social Support: Expanding to Social Relations

Social networks and the resources that flow from them are essential to health and well-being;25 however, workplace relationships are less commonly seen as sources of support. Relationships between managers and employees, among employees acting in teams, and between employees and clients affect health and well-being independently and can buffer stressful conditions.25,26 Social support was incorporated as a key component in the job strain model, with research demonstrating improved well-being among workers receiving managers’ and coworkers’ support.14 However, given the growing number of workers who are also primary caregivers, the updated framework identifies new types of social resources needed to support employees’ personal or family life more broadly.26,27

Beyond social support, informational, financial, and skill-related resources also flow through networks.25 A recent study suggests that quality of interpersonal collaboration affects employee engagement more strongly than employee sense of purpose.28 Moreover, because of the growth of the health care and service sectors, an increasing proportion of jobs require substantial interdependence among workers and between workers and their patients or customers. For example, health care workers’ strong focus on patient care and teamwork can be rewarding but can also provide more opportunities for negative interactions.29 As workforces become increasingly diverse, more opportunities for subtle bias arise, and diversity requires deliberate work to build close and productive teams. Thus, in our updated framework, we move beyond an emphasis on individual-level social support to emphasize a relational focus for group-level task coordination.

PROMISING WORK REDESIGN STRATEGIES

Following our model refinements and drawing on the strongest evidence available, we have identified promising organizational change strategies to improve worker health.

Enhancing Job Control

Training and tools to facilitate increased schedule control

With growth in the service sector and technology pushes for around-the-clock availability, workers need more control over schedules and location. Several rigorous studies have shown that this approach improves worker health.

For example, the Work, Family and Health Network conducted randomized controlled trials in two industries, an information technology division of a US Fortune 500 firm and a long-term care industry. The intervention aimed to increase employees’ control over when they did their work and, in the information technology division, where work was done. Information technology workers in treatment groups reported better outcomes 18 months postrandomization, not only with regard to lower turnover but also across a number of health-related factors, including reductions in cardiometabolic risk.21,27,30 In the long-term care setting, the intervention improved cardiometabolic risk and organizational engagement; however, results across other outcomes were more mixed, perhaps because there was less latitude to alter scheduling within a highly structured setting.31 Taken together, these findings highlight the promise of increasing schedule flexibility but also point to the importance of tailoring interventions to occupational contexts.

Two other high-quality studies evaluating schedule interventions in lower-income workforces revealed positive effects.32,33 For instance, Garde et al. found that a self-rostering system in which employees chose their own work schedule within certain parameters led to decreased distress. Several studies have shown promising effects of interventions aiming to increase schedule predictability. For example, a randomized controlled trial in Gap stores evaluated changes in multiple aspects of scheduling.34,35 Among other practices, the treatment included increasing the consistency of associates’ shifts and offering part-time employees a soft guarantee of 20 or more hours a week. Treatment group employees had more schedule stability and better sleep quality, and parents and second job-holders reported decreased stress. Notably, the new practices were good for business, resulting in better retention of experienced employees, a 7% boost in median sales, and a 5% increase in labor productivity.

Worker participation and union involvement in work redesign

Increasing worker voice is another promising strategy for improving worker well-being. Several studies have evaluated participatory approaches in which employees engage in a facilitated process of problem identification and implementation of workplace changes. Both experimental and observational research demonstrates that structured interventions incorporating a participatory process are particularly effective.8 For example, some organizations are implementing “unit-based teams,” in which union representatives and management jointly lead workers through a participatory change process designed to identify and test solutions to workplace problems in which all parties have a common interest. Preliminary evidence is promising, showing that team members are more likely than nonmembers to feel that they can influence their work environments.36

Taming Job Demands

Adding targeted staffing and other resources

Work demands have intensified in part as a result of lean staffing. Although employers may be reluctant to increase staffing for fear of compromising profit margins, emerging evidence suggests that strategically growing staff could be good for both business and worker well-being. Operations scholar Ton37 has found that slack staffing (i.e., staffing with enough labor hours to meet demand at peak times), along with other operational strategies that fully engage workers, boosts profits and worker morale. The Gap study provides compelling experimental evidence for positive effects; a key intervention component was adding staff in a targeted manner. This change contributed to increased sales and labor productivity and outweighed added labor costs, producing a positive return on investment.34,35

Adding workplace resources strategically can also ease work demands and improve well-being. Several rigorous interventions in health care settings have alleviated staff demands by improving training and support for new hires, increasing primary care visit times, and adding support staff and a new prescription telephone line to free up nurses’ time. At follow-up, clinicians in intervention groups showed reductions in psychosocial and physical demands, improvements in mental health, and reductions in intention to leave.38,39

Streamlining work to reduce demands

Making work processes more efficient can reduce workloads and may improve worker well-being. The health care interventions just described38,39 included strategies to remove bottlenecks to patient care, such as standardizing certain clinical processes so that nurses could act independently of doctors. A study of Danish postal workers showed that Kaizen—a continuous improvement strategy that focuses on reducing unnecessary tasks in work processes—predicted higher job satisfaction and better mental health when it was used in promoting productivity and worker well-being.40 However, when employing “lean management” practices, it is critical to orient toward worker well-being as a goal and to build in time for healthy socializing and some staffing slack to adjust to seasonal or other variations in work demands; otherwise, these practices can easily increase work pressure and reduce well-being.41

Enhancing Workplace Social Relations

Supervisor support for family and personal life

Several intervention studies that enhanced manager support for employees’ family life showed promising effects on worker well-being.27,30,31 For example, a study with supermarket workers revealed that family-supportive supervisor behaviors predicted improved job satisfaction and physical health among employees with high levels of work–family conflict. In the intervention, employees and managers discussed work–family concerns and managers were encouraged to develop new, more explicitly supportive habits.42

Training and support for effective teamwork

The growth of highly interdependent jobs in the 21st century has spawned work environments where employees must frequently interact with clients or patients and coordinate with each other. Experimental evaluations of initiatives designed to improve relational and team dynamics are generally promising. The ARC (Availability, Responsiveness, and Continuity) intervention improves teamwork and communication by fostering collaboration within and across related social service organizations, thereby developing trust and support. Teams work together to identify and implement processes that will improve organizational climate, reduce turnover rates, and improve the quality of client services. In randomized controlled trials conducted in two different settings, Glisson et al.43,44 found that the study intervention led to improvements in numerous factors related to well-being and productivity, including employee morale, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment, as well as reductions in employee turnover, emotional exhaustion, and role overload.

A quasi-experimental study of health care workers revealed that various strategies designed to build teamwork and enhance communication improved employee mental health. Tactics included establishing overlapping nursing schedules to improve communication about patient conditions, revising information and messaging systems to address communication gaps between management and nurses, and instituting team meetings to discuss problems and solutions to relational issues.39 Another line of work has identified “relational coordination” as a promising approach to improving teamwork dynamics through facilitated interventions aimed at fostering high-quality communication, shared goals, and mutual respect.29 Although experimental work is warranted, numerous observational studies have linked training for teamwork, creating shared accountability, and coordinating information systems with multiple positive performance and well-being outcomes.29

REFLECTIONS

As vividly demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, work conditions can have a significant impact on health. It is time for a more creative and courageous approach to improving workers’ health and well-being, one that aspires not only to mitigating misery but also to fostering positive mental health. As noted by Schulte et al.9 and outlined in the Total Worker Health approach even before the pandemic, maintaining worker well-being and paying attention to the mental and physical health consequences of work environments must be a priority, both for public policy and for employers. Work redesign points to the possibility of moving upstream to address conditions of work that contribute to ill health and foster health inequities.

Workplace intervention studies consistently demonstrate that the current organization of work is malleable and real improvements are feasible. Documented benefits of redesigning work with regard to control, job demands, and social relationships are substantial, including reduced cardiometabolic risks, improved mental health and job satisfaction, and productivity-related benefits such as reduced employee turnover.8 That said, a key limitation of this growing field is that redesign research has tended to focus on certain industries (e.g., health care, social services) and groups of workers (e.g., higher wage, white collar); there is less research on small businesses, although emerging observational evidence suggests that useful approaches can be applied.45,46

Although the model should be broadly relevant, additional research is needed to be confident in stating which redesigns will be most effective for workers from different income groups or occupational contexts. Moreover, research on improving the health of individuals whose workplaces are less “fixed,” such as temporary or gig workers, is missing altogether, a significant gap given the growth of this workforce. Accordingly, NIOSH Total Worker Health now recognizes nonstandard work arrangements as a priority area for future research.47 Furthermore, contingent workforces may require public policies that more fully incorporate them into companies as employees if redesign strategies are to gain traction.

Despite some limitations, the evidence base is sufficient to motivate action. Employers can do more than pay for new wellness programs with questionable impact. Executives and managers can look carefully at how their organizational processes and practices affect the health and well-being of workers and their families. Work redesign may be less expensive, in terms of upfront costs to a firm, than wellness initiatives. These costs usually involve a vendor and financial incentives paid to participating employees; spending on wellness programs now averages more than $700 per employee.48 By contrast, existing staff can and do operate redesign initiatives with little or no costs incurred from vendor support. Even with outside consultants and all labor time included, one extensive redesign initiative cost $340 per employee.49

However, a redesign approach requires openness to scrutinizing current practices and day-to-day operations. Effective initiatives require managers’ willingness to foster participation from the bottom up, in a collective process of constructive change. Although the prospect of work redesign may seem daunting, employers should weigh its promise against the often unrecognized costs of business as usual. Such costs include reduced productivity, higher absenteeism and turnover, and higher health care expenses from stress-induced erosion of employee health.

Motivating employers to do what is right for the health and well-being of their workers will require support from federal and state governments. In one recent article, it was concluded that the United States has limited awareness of the detrimental health effects of job strain and few coordinated governmental actions to reduce it.50 By contrast, over recent decades EU governments have initiated various effective actions, some of which could be easily adopted by US public agencies (e.g., NIOSH, state health departments), to help organizations reduce workplace stressors and create nonbinding standards for managing psychosocial workplace risks.50 Although NIOSH has a leadership role to play in this effort, effective implementation requires public–private partnerships between federal regulatory agencies (Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Office of Management and Budget, US Department of Health and Human Services) and businesses, unions, and other voluntary organizations to develop incentives for sustaining these changes. The private sector has also begun to recognize these issues through such declarations as the Business Roundtable statement on investing in employees and communities.51

We will need to develop clear, publicly available tools (e.g., business case studies, toolkits, briefs) that target communications to a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including business leaders, unions, and worker advocacy groups. For the most enduring effects on worker health, voluntary work redesign initiatives must be complemented by updated labor regulations that ensure healthy workplace protections for all, such as paid family and medical leave and “fair work week laws” granting workers greater scheduling control in jobs with unpredictable hours.

CONCLUSIONS

Decades of research have documented persuasively that work is a critical social determinant of health. Now evidence is mounting that work redesign adapted for the 21st century is an important lever to improve worker well-being and health equity in this country. Leveraging an updated model—Work Design for Health—we propose a range of concrete strategies that can significantly enhance worker well-being. The need for action is ever more imperative. Although more research is needed to confirm the value of these strategies, in the meantime we can build networks of experts, labor advocates, and employers to facilitate shared learning and look to other countries and “high road” employers for effective models. In these ways, we can begin to prioritize the most promising approaches to redesigning work for well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work on this article was supported by pioneer grant 74575 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

We thank Kimberly E. Fox of Bridgewater State University for her contributions to the aforementioned grant, including the systematic review of experimental research on work redesign for worker well-being on which this paper is partially based. We also thank Nicole Goguen of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies for developing the graphic in Figure 1.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this research because no human participants were involved.

Footnotes

See also Hammer, p. 1784.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulte P, Vainio H. Well-being at work—overview and perspective. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36(5):422–429. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clougherty JE, Souza K, Cullen MR. Work and its role in shaping the social gradient in health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):102–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh J, Pfeffer J, Zenios S. Exposure to harmful workplace practices could account for inequality in life spans across different demographic groups. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1761–1768. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparks K, Faragher B, Cooper CL. Well-being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2001;74(4):489–509. doi: 10.1348/096317901167497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones D, Molitor D, Reif J. What do workplace wellness programs do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study. Q J Econ. 2019;134(4):1747–1791. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjz023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rongen A, Robroek SJW, van Lenthe FJ, Burdorf A. Workplace health promotion: a meta-analysis of effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox KE, Johnson ST, Berkman LF, et al. Organisational- and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: a systematic review. Work Stress. 2021;0(0):1–30. 10.1080/02678373.2021.1969476 [DOI]

- 9.Schulte PA, Guerin RJ, Schill AL, et al. Considerations for incorporating “well-being” in public policy for workers and workplaces. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e31–e44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feltner C, Peterson K, Palmieri Weber R, et al. The Effectiveness of Total Worker Health interventions: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):262–269. doi: 10.7326/M16-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M, Hudson H, Richards R, Chang C, Chosewood L, Schill A. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2017-112/default.html

- 12.Tamers SL, Goetzel R, Kelly KM, et al. Research methodologies for Total Worker Health®: proceedings from a workshop. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(11):968–978. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker SK, Morgeson FP, Johns G. One hundred years of work design research: looking back and looking forward. J Appl Psychol. 2017;102(3):403–420. doi: 10.1037/apl0000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karasek R, Theorell T.Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalleberg A.Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider D, Harknett K. Consequences of routine work-schedule instability for worker health and well-being. Am Sociol Rev. 2019;84(1):82–114. doi: 10.1177/0003122418823184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weil D. The future of occupational safety and health protection in a fissured economy. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(5):640–641. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King RB, Karuntzos G, Casper LM, et al. Work-family balance issues and work-leave policies Gatchel RJ, Schultz IZ, Gatchel RJ.Handbook of Occupational Health and Wellness. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; 2012323–339.. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhouse S.Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kochan TA, Yang D, Kimball WT, Kelly EL. Worker voice in America: is there a gap between what workers expect and what they experience? Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2019;72(1):3–38. doi: 10.1177/0019793918806250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly EL, Moen P.Overload: How Good Jobs Went Bad and What We Can Do About It. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golden L, Wiens-Tuers B. Mandatory overtime work in the United States: who, where, and what? Labor Stud J. 2005;30(1):1–26. doi: 10.1177/0160449X0503000102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603838 individuals. Lancet. 2015;386(10005):1739–1746. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramioul M, Van Hootegem G.Relocation, the restructuring of the labour process and job quality Drahokoupil J.The Outsourcing Challenge: Organizing Workers Across Fragmented Production Networks. Brussels, Belgium: ETUI; 201591–115.. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berkman LF, Krishna A.Social network epidemiology Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour M.Social Epidemiology. 2nd edOxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2014234–289.. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kossek EE, Pichler S, Bodner T, Hammer LB. Workplace social support and work–family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers Psychol. 2011;64(2):289–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moen P, Kelly EL, Fan W, et al. Does a flexibility/support organizational initiative improve high-tech employees’ well-being? Evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network. Am Sociol Rev. 2016;81(1):134–164. doi: 10.1177/0003122415622391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cross R, Edmondson A, Murphy W. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/a-noble-purpose-alone-wont-transform-your-company

- 29.Gittell JH, Logan C, Cronenwett J, et al. Impact of relational coordination on staff and patient outcomes in outpatient surgical clinics. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;45(1):12–20. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly EL, Moen P, Oakes JM, et al. Changing work and work-family conflict: evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network. Am Sociol Rev. 2014;79(3):485–516. doi: 10.1177/0003122414531435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kossek EE, Thompson RJ, Lawson KM, et al. Caring for the elderly at work and home: can a randomized organizational intervention improve psychological health? J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24(1):36–54. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloom N, Liang J, Roberts J, Ying ZJ. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q J Econ. 2015;130(1):165–218. doi: 10.1093/qje/qju032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garde AH, Albertsen K, Nabe-Nielsen K, et al. Implementation of self-rostering (the PRIO project): effects on working hours, recovery, and health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38(4):314–326. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams JC, Lambert SJ, Kesavan S, et al. https://worklifelaw.org/projects/stable-scheduling-study/report

- 35.Williams JC, Lambert SJ, Kesavan S, et al. https://worklifelaw.org/projects/stable-scheduling-study/stable-scheduling-health-outcomes

- 36.Kochan T. https://nanopdf.com/download/the-kaiser-permanente-labor-management-partnership-2009-2013_pdf

- 37.Ton Z.The Good Jobs Strategy: How the Smartest Companies Invest in Employees to Lower Costs and Boost Profits. Boston, MA: New Harvest/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourbonnais R, Brisson C, Vézina M. Long-term effects of an intervention on psychosocial work factors among healthcare professionals in a hospital setting. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(7):479–486. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Thiele Schwarz U, Nielsen KM, Stenfors-Hayes T, Hasson H. Using kaizen to improve employee well-being: results from two organizational intervention studies. Hum Relat. 2017;70(8):966–993. doi: 10.1177/0018726716677071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker SK. Longitudinal effects of lean production on employee outcomes and the mediating role of work characteristics. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(4):620–634. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Anger WK, Bodner T, Zimmerman KL. Clarifying work-family intervention processes: the roles of work-family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2011;96(1):134–150. doi: 10.1037/a0020927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Atkinson S, Williams NJ. Randomized trial of the Availability, Responsiveness, and Continuity (ARC) organizational intervention with community-based mental health programs and clinicians serving youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(8):780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glisson C, Dukes D, Green P. The effects of the ARC organizational intervention on caseworker turnover, climate, and culture in children’s service systems. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30(8):855–880. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLellan DL, Williams JA, Katz JN, et al. Key organizational characteristics for integrated approaches to protect and promote worker health in smaller enterprises. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(3):289–294. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohlman DS, Campo S, Hall J, Robinson EL, Kelly KM. What could Total Worker Health® look like in small enterprises? Ann Work Expo Health. 2018;62(suppl 1):S34–S41. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Total Worker Health in Action. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/newsletter/twhnewsv9n3.html

- 48.Milligan S. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0917/pages/employers-take-wellness-to-a-higher-level.aspx

- 49.Barbosa C, Bray JW, Brockwood K, Reeves D. Costs of a work-family intervention: evidence from the work, family, and health network. Am J Health Promot. 2014;28(4):209–217. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.121108-QUAN-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goh J, Pfeffer J, Zenios SA. Reducing the health toll from US workplace stress. Behav Sci Policy. 2019;5(1):1–13. doi: 10.1353/bsp.2019.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Business Roundtable. https://opportunity.businessroundtable.org/ourcommitment