Abstract

This study examines antibody durability in individuals who received an mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection vs those without infection.

Waning serum antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 have raised questions about long-term immunity. Lower antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein are associated with breakthrough infections after vaccination, prompting consideration of booster doses.1,2 Prior infection may enhance protection from vaccination, stimulating inquiry about hybrid immunity.3 Our objective was to examine SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG antibodies in a longitudinal cohort, comparing antibody durability in individuals who received an mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine with or without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

A convenience sample of 3500 health care workers from the Johns Hopkins Health System were enrolled starting June 2020 and followed up through September 3, 2021. Participants provided serum samples longitudinally, separated by at least 90 days. SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results and vaccination dates (inside and outside the health system) were collected from electronic health records. Included participants had a serum sample collected at least 14 days after receiving the second dose of an mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined by the date of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results prior to first vaccine dose. IgG antibody measurements were obtained using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Euroimmun), estimating optical density ratios with a lower threshold of 1.23 and upper threshold of 11.00 based on assay saturation.4,5 Linear regression models for log-transformed postvaccination antibody measurements were used to compare absolute and relative differences in median antibody measurements among health care workers with or without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection at 1, 3, and 6 months and health care workers with PCR-confirmed prior SARS-CoV-2 infection less than or equal to 90 days and greater than 90 days before receipt of the vaccine at 1 and 3 months, after adjusting for vaccine type, age, and sex. Statistical significance was defined as a 95% CI that did not include 1.00 for the relative adjusted median and a 95% CI that did not include 0 for the absolute difference in adjusted median. Analyses were performed in R software, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation).

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University with verbal consent.

Results

Of the 1960 health care workers who provided serum samples at least 14 days after receipt of the second vaccine dose, 73 (3.7%) had evidence of previous infection (41 with positive PCR results ≤90 days before vaccination and 32 with positive PCR results >90 days before vaccination). Of these 1960 participants, 80% were women, 95% were non-Hispanic/Latino, and 80% were White. The median age of participants was 40.4 (IQR, 32.6-52.1) years.

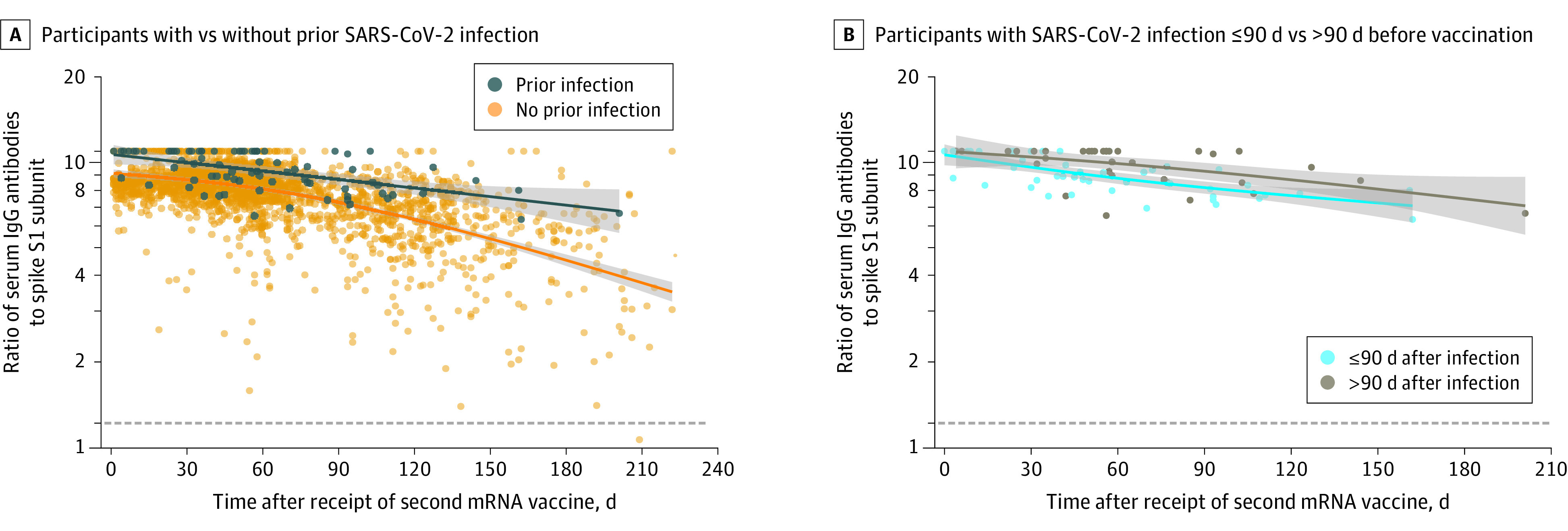

Among participants without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, the adjusted median antibody measurements were 8.69 (95% CI, 8.56-8.80) at 1 month, 7.28 (95% CI, 7.15-7.40) at 3 months, and 4.55 (95% CI, 4.16-4.91) at 6 months after vaccination (Figure, A, and Table). Compared with participants without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, those with prior infection maintained higher postvaccination adjusted median antibody measurements by an absolute difference of 1.25 (95% CI, 0.86-1.62) (relative difference, 14% [95% CI, 10%-19%]) at 1 month, 1.42 (95% CI, 0.98-1.86) (relative difference, 19% [95% CI, 13%-26%]) at 3 months, and 2.56 (95% CI, 1.66-4.08) (relative difference, 56% [95% CI, 35%-94%]) at 6 months. Individuals with PCR-confirmed infection more than 90 days before vaccination had higher postvaccination adjusted antibody measurements compared with those with PCR-confirmed infection less than or equal to 90 days before vaccination, of 10.52 (95% CI, 10.13-11.00) (absolute difference, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.28-1.48]; relative difference, 9% (95% CI, 3%-16%]) at 1 month and 9.31 (95% CI, 8.47-9.98) (absolute difference, 1.09 [95% CI, 0.17-1.92]; relative difference, 13% [95% CI, 2%-24%]) at 3 months (Figure, B, and Table).

Figure. Waning IgG Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 After Vaccination in Health Care Workers With or Without Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection.

Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results prior to receipt of the first dose of the mRNA vaccine. The dotted lines represent the positive IgG threshold, at an antibody measurement of 1.23, the lines represent the unadjusted median antibody measurements as a function of days following mRNA vaccination, based on natural cubic splines (2 degrees of freedom) for each group, and shaded areas represent 95% CIs for the unadjusted median antibody measurements.

Table. Adjusted Antibody Measurements Over Time After 2 Doses of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Health Care Workers With or Without Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection.

| Interval | Participant IgG measurement, adjusted median (IQR) | Difference in adjusted median (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With prior infection (n = 73; 80 samples) | Without prior infection (n = 1887; 2235 samples) | Relative | Absolute | |

| 1 mo | 9.94 (9.58-10.29) | 8.69 (8.56-8.80) | 1.14 (1.10-1.19) | 1.25 (0.86-1.62) |

| 3 mo | 8.70 (8.27-9.12) | 7.28 (7.15-7.40) | 1.19 (1.13-1.26) | 1.42 (0.98-1.86) |

| 6 mo | 7.12 (6.29-8.64) | 4.55 (4.16-4.91) | 1.56 (1.35-1.94) | 2.56 (1.66-4.08) |

| Intervalb | Vaccination >90 d after prior SARS-COV-2 infection (n = 32; 34 samples) | Vaccination ≤90 d after prior SARS-COV-2 infection (n = 41; 46 samples) | Relative | Absolute |

| 1 mo | 10.52 (10.13-11.00) | 9.65 (9.24-10.02) | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) | 0.86 (0.28-1.48) |

| 3 mo | 9.31 (8.47-9.98) | 8.22 (7.81-8.63) | 1.13 (1.02-1.24) | 1.09 (0.17-1.92) |

Adjusted median IgG measurements were estimated from linear regression models of log-transformed antibody measurements as a function of time (natural cubic spline with 2 degrees of freedom), group, interaction of time, and group adjusting for vaccine type, age, and sex. The 95% CIs for adjusted median IgG and relative median were constructed via the percentile bootstrap procedure using 1000 bootstrap samples of health care workers to account for clustering of serum samples within health care workers.

Adjusted median IgG measurements and relative median at 6 months were not estimated for health care workers with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection ≤90 days and >90 days prior to first vaccine dose separately due to few data points (n = 3) beyond 150 days.

Discussion

Health care workers with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection followed by 2 doses of mRNA vaccine (3 independent exposures to spike antigen) developed higher spike antibody measurements than individuals with vaccination alone. Consistent with work comparing extended vaccine dosing intervals, the study showed that a longer interval between infection and first vaccine dose may enhance the antibody response.6

Limitations of the study included defining SARS-CoV-2 infection by positive PCR test results (potentially misclassifying participants with unconfirmed prior infection), the use of convenience sampling, and a small proportion of included participants with infection prior to vaccination. The study also did not examine neutralization titers or reinfection. Generalizability may be limited by a majority female, White, middle-aged population.

Further investigation is warranted to determine whether increased postvaccination antibody durability in previously infected individuals is attributable to number of exposures, interval between exposures, or the interplay between natural and vaccine-derived immunity. Studies are needed to elucidate how serological testing can inform optimal vaccine timing and need for booster doses.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205-1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, et al. Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1474-1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Rutkowska M, et al. High genetic barrier to SARS-CoV-2 polyclonal neutralizing antibody escape. Nature. 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04005-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caturegli G, Materi J, Howard BM, Caturegli P. Clinical validity of serum antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 : a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(8):614-622. doi: 10.7326/M20-2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debes AK, Xiao S, Colantuoni E, et al. Association of vaccine type and prior SARS-CoV-2 infection with symptoms and antibody measurements following vaccination among health care workers. JAMA Intern Med. 2021. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parry H, Bruton R, Stephens C, et al. Extended interval BNT162b2 vaccination enhances peak antibody generation in older people. MedRxiv. Preprint posted May 17, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.15.21257017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]