Abstract

Business-to-business (B2B) sales sector is among the business sectors severely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. It is critical to understand how to help the workforce in the B2B sales sector grow resilient through such a crisis. The main aim of this study is to examine the role of employer event communication in fostering B2B salesperson resilience. The data were collected from 447 sales employees from manufacturing firms in an Asian emerging market during the pandemic crisis. The results revealed the positive link between employer event communication and salesperson resilience. Deliberate rumination was detected as a mediator for the relationship between employer event communication and resilience. However, while the significant and negative association was observed between employer event communication and intrusive rumination, the non-significant relationship occurred between intrusive rumination and resilience. Customer demandingness moderated the effects of intrusive and deliberate rumination on salesperson resilience. Discussions on theoretical and practical implications are displayed.

Keywords: Resilience, Communication, Intrusive rumination, Deliberate rumination, Customer demandingness, COVID-19, Vietnam

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has generated unprecedented disruptions to practically every nation's economy and laid bare the vulnerabilities of several industries (Hynes et al., 2020) including manufacturing (Hartmann & Lussier, 2020; Rapaccini, Saccani, Kowalkowski, Paiola, & Adrodegari, 2020). Such disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis have immediately and severely impacted the salesforce in the B2B sales context. Salespeople have faced not only the threat of the pandemic spread and job insecurity (i.e., temporary or permanent dismissal), but also challenges from their work (Cortez & Johnston, 2020; Hartmann & Lussier, 2020). Lockdowns and border closures have caused supply chain breakdowns, inventory shortages, serious supply and demand shifts, product delivery issues, cancellations of crucial events and meetings (e.g., customer meetings conferences, tradeshows), and new work arrangements (e.g., expansion and contraction of roles changes to information flows, virtual selling) (Hartmann & Lussier, 2020; Okorie et al., 2020).

To respond to such disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis, B2B salespeople need to devise wide-ranging solutions that address more complex demands from customers, among other activities. Partially relevant to such activities, resilience is a vital psychological resource (Sharma, Rangarajan, & Paesbrugghe, 2020) that may be of salience for leveraging customer-oriented behaviors, sales performance, and customer satisfaction (Lussier & Hartmann, 2017). Resilience refers to an individual's ability to adapt effectively and restore equilibrium in face of severe adversity (Bonanno, 2004; Sameroff & Rosenblum, 2006). Prior research has linked employee resilience, as a separate construct or part of psychological capital or resources, to employee performance in service domains (Liu, 2018; Nadeem, Riaz, & Danish, 2019), in sales domains (Coomer, 2016; Krush, Agnihotri, Trainor, & Krishnakumar, 2013; Meintjes & Hofmeyr, 2018; Peesker, Ryals, Rich, & Boehnke, 2019), as well as in B2B sales contexts (Bande, Fernández-Ferrín, Varela, & Jaramillo, 2015; Lussier & Hartmann, 2017). These links may result from the fact that resilience can enable individuals to cope with pressure and adversity as well as develop exploratory behaviors (Lussier & Hartmann, 2017).

Regardless of the magnitude of sales employees' resilience in contributing to their sales performance (Coomer, 2016; Lussier & Hartmann, 2017; Meintjes & Hofmeyr, 2018; Peesker et al., 2019), scant scholarly attention has been devoted to how sales employees, particularly in the B2B domain, experienced a pandemic crisis (Hartmann & Lussier, 2020) as well as became resilient and grew through it (Peasley, Hochstein, Britton, Srivastava, & Stewart, 2020). As the review in Table 1 indicates, research on the impacts of crises or epidemics on the B2B industries has tended to assess the resilience of industries, supply chains (Okorie et al., 2020; Remko, 2020), or B2B organizations (Cankurtaran & Beverland, 2020; Rapaccini et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020; Zafari et al., 2020). Hartmann and Lussier (2020) and Sharma et al. (2020) have highlighted the importance of salesperson resilience to the organizational resilience particularly in face of a crisis such as the COVID-19, and called for investigations into resilience among B2B salespersons in a crisis event as well as mechanisms that nurture their resilience.

Table 1.

Summary of relevant studies on resilience under crisis in the B2B/sales context and employee resilience in general business.

| Study | Focus | Context | Methods | Antecedents/outcomes | Mediators/moderators | Underlying theories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | Salesperson resilience | The COVID-19 crisis; B2B firms from mixed industries in an Asian emerging market (Vietnam) | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: employer event communication [research gap] | Mediators: intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination [research gap] | Conservation of resources theory |

| Moderator: customer demandingness [research gap] | ||||||

| Resilience in face of crisis | ||||||

| Peasley et al. (2020) | Salesperson performance (as resilience through the COVID-19 crisis) | The COVID-19 crisis; B2B salespeople from a cross-section of industries | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: salesperson personal (health, relationship, financial) stress | Mediator: salesperson burnout | Job Demands |

| Resources (JD-R) theory, conservation of resources theory | ||||||

| Kimura, Bande, and Fernandez-Ferrín (2018) | Salesperson resilience as a moderator | Stressful circumstances; mixed industries in Spain | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: work overload | Mediator: use of intimidation | Lazarus's (1991) transactional theory |

| Outcome: sales performance | ||||||

| Moderator: resilience | ||||||

| Hartmann and Lussier (2020) | Sales force and organization outcomes (revenue, profitability, customer satisfaction, and margins) | The COVID-19 crisis; B2B organizations | Qualitative (interviews) | Antecedents: environment (exogenous shock: COVID-19 pandemic), sales force variables (human, structure, task, technology) | Socio-technical systems theory (Bostrom & Heinen, 1977), Leavitt's (1965) model of organizational change | |

| Zafari, Biggemann, and Garry (2020) | B2B firm resilience | The COVID-19 crisis; B2B businesses in the Middle East | Qualitative (interviews) | Antecedent: mindful management of relationships | ||

| Rapaccini et al. (2020) | Manufacturing firm resilience | The COVID-19 crisis; industrial firms in Northern Italy | Quantitative (surveys) and qualitative (interviews) | Antecedents: servitization, digital transformation, advanced services | ||

| Okorie et al. (2020) | Manufacturing resilience | The COVID-19 crisis; manufacturing firms and non-manufacturing firms across six continents | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: the barriers and enablers of manufacturing resilience | ||

| Sharma et al. (2020) | Resilience of commercial organizations | The COVID-19 crisis; mixed industries | Qualitative (interviews with sales leaders) | Antecedents: flexibility and adaptiveness in the salesperson functions, adaptiveness of scale, and technology adaptiveness | ||

| Cortez and Johnston (2020) | B2B firms' management of the crisis | The COVID-19 crisis; mixed industries in the U.S., Europe, and Latin America | Qualitative (interviews) | Antecedents: digital transformation, decision-making processes, leadership, and emotions and stress | Social exchange theory | |

| Remko (2020) | Supply chain resilience | The COVID-19 crisis; supply chain executives | Qualitative (interviews) | Antecedents: textbook supply, demand, and control risks in the supply chain | ||

| Employee resilience and contextual levers in general business | ||||||

| Lin and Liao (2020) | Employee resilience | Diverse organizations in Taiwan | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: leader resilience | Moderator: leader's future temporal focus | Social learning theory |

| Fan, Luo, Cai, and Meng (2020) | Employee resilience | Employees from the southeast coastal cities of China | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: leader resilience | Conservation of resources theory | |

| Outcomes: job burnout, organizational citizenship behavior | ||||||

| Franken, Plimmer, and Malinen (2020) | Employee resilience | A large public organization in New Zealand | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: paradoxical leadership | Mediator: perceived organizational support | Social exchange theory |

| Malik and Garg (2020) | Employee resilience | Indian IT organizations | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: learning organization | Fredrickson's (2001) broaden-and-build theory, conservation of resource theory | |

| Outcome: work engagement | ||||||

| Cooper, Wang, Bartram, and Cooke (2019) | Employee resilience | Bank branches in 16 Chinese banks | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: well-being-oriented HRM practices | Mediator: social climate | Social information processing theory |

| Outcome: employee (in-role) performance | ||||||

| Nadeem et al. (2019) | Employee resilience | Service sectors of Pakistan including banking, insurance, telecommunication, airline and hospitality industry | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: high-performance work system (HPWS) | Social exchange theory | |

| Outcomes: employee service performance, their organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) | ||||||

| Khan et al. (2019) | Employee resilience | Pakistan's telecommunications sector | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: four key areas of HR practices – job design, information sharing and flow within an organization, employee benefits (monetary and non-monetary), and employee development opportunities | ||

| Cooke, Cooper, Bartram, Wang, and Mei (2019) | Employee resilience | Chinese banking industry | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: high-performance work systems (HPWS) | Job demands-resources model | |

| Outcome: employee engagement | ||||||

| Cooke, Wang, and Bartram (2019) | Employee resilience | Chinese banking industry | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: supportive leadership, co-worker support | Moderators: performance pressure (workload, working time) | Conservation of resources theory, social cognitive theory |

| Khaksar, Maghsoudi, and Young (2019) | Employee resilience | National Iranian Gas Company | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: social capital | Social capital theory | |

| Outcome: job burnout | ||||||

| Kakkar (2019) | Employee resilience | Three information technology and enabled services organizations in India | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: leader–member exchange (LMX) | Mediators: promotion focus, prevention focus | LMX theory |

| Zhu, Zhang, and Shen (2019) | Employee resilience | Mainland China | Field and experimental studies | Antecedent: humble leadership | Mediators: work-related promotion focus, perceived insider identity | Social information processing theory |

| Salehzadeh (2019) | Employee resilience | Four medium-sized service organizations in Iran that provide services such as electric, gas and telecommunication | Mixed method design (interview and questionnaire) | Antecedents: leaders' attractive behaviors, one-dimensional behaviors, must-be behaviors, and reverse behaviors | Kano model (Kano, 1984), social exchange theory | |

| Tonkin, Malinen, Näswall, and Kuntz (2018) | Personal and employee resilience | A government department and a tertiary education provider in New Zealand | Experimental design and surveys | Antecedent: workplace wellbeing intervention | Trait activation theory, self-determination theory | |

| Malik and Garg (2017) | Employee resilience | Software product and services companies in Delhi, India | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: learning culture, inquiry and dialogue, knowledge sharing structure | Fredrickson's (2001) broaden-and-build theory | |

| Outcome: affective commitment to change | ||||||

| Kuntz, Connell, and Näswall (2017) | Employee resilience | Four medium-sized organizations in New Zealand | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: support from coworkers, performance feedback from job | Moderators: promotion focus, prevention focus | Regulatory focus theory, conservation of resources theory |

| Braun, Hayes, DeMuth, and Taran (2017) | Employee resilience | A random sample of 1659 employees | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: social support, positive relationships, openness to experiences, individual renewal | Moderator: employee agility | |

| Outcome: reduced stress | ||||||

| Meneghel, Borgogni, Miraglia, Salanova, and Martínez (2016) | Employee resilience | One of the largest service companies in Italy | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedent: collective perceptions of social context | Social information processing theory | |

| Outcomes: job satisfaction, job performance | ||||||

| Sommer, Howell, and Hadley (2016) | Employee resilience | Two large hospitals and 17 smaller medical sites in the province of Ontario, Canada | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: transformational leadership, the passive form of management-by-exception (MBE) leadership | Mediators: positive affect, negative affect | Fredrickson's (2001) broaden-and-build theory |

| Hodliffe (2014) | Employee resilience | A finance organization and a civil engineering organization | Quantitative (surveys) | Antecedents: empowering leadership, learning culture | ||

| Outcomes: job engagement, job satisfaction, turnover intention | ||||||

Moreover, the extant resilience literature has focused on the three domains of employee resilience, consisting of employee resilience as openness towards organizational changes (e.g., Kuntz, Näswall, & Malinen, 2016; Wanberg & Banas, 2000), resilience training for promoting employee well-being and performance (e.g., Robertson, Cooper, Sarkar, & Curran, 2015; Tonkin et al., 2018; Vanhove, Herian, Perez, Harms, & Lester, 2016), and career resilience as the capability to bounce back following a career setback (e.g., Arora & Rangnekar, 2014; Mishra & McDonald, 2017). By delving into resilience among salespersons during a pandemic crisis, this study covers the gap on employee resilience from crises in the stream of employee resilience research.

Albeit the three domains of employee resilience in the recent reviews (e.g., Bal, 2020; Hartmann, Weiss, Newman, & Hoegl, 2020) as well as our review (see Table 1) indicate the role of employee-oriented mechanisms as a social support resource for the development of employee resilience, the role of communication in the equation of employee resilience, particularly in a crisis context, has garnered insufficient scholarly attention (Hodliffe, 2014; Kim, 2016; Malik & Garg, 2017). Our study aims to cover this void by unravelling how employer event communication promotes B2B salesperson resilience. Due to the relevance of the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) to human adaptation (Hou, Law, & Fu, 2010) and resilience (Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019), we draw on this theory to expect that the employer's communication of an event such as the COVID-19 may serve as a source of social support resource for employees to grow resilient in face of the impacts of such a crisis. An organization can provide resources for employee resilience by using event communication ecologies to (a) connect with employees, (b) correct inaccurate reports about the organization's event-related policies, and (c) confirm information about employees' situation during the event (Spialek & Houston, 2018).

Since the relationship between employer event communication and resilience of workers in face of a crisis event has not been unravelled in general business as well as in the B2B discipline, it has been unclear about how (i.e., through what mechanisms) and when (i.e., depending on what contingencies) employer event communication is related to salesperson resilience. Cognitive processes were viewed to be engendering positive changes through an event (Calhoun, Cann, & Tedeschi, 2010; Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006). Building on the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) and the impact of social support on cognitive processes (Kelly et al., 2017), our study expects that employer event communication can function as a resource to set in motion two cognitive processes, namely intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination. While intrusive rumination entails individuals' invasive thoughts on the negative consequences of the event (Schmaling, Dimidjian, Katon, & Sullivan, 2002), deliberate rumination is a proactive pursuit of its meaning (Lianchao & Tingting, 2020). By focusing on the negative consequences of the event (Eze, Ifeagwazi, & Chukwuorji, 2020), intrusively ruminative individuals perceive their resources being threatened or lost and tend to protect resources rather than invest resources in adaptive behaviors. Contrarily, by making sense of the event (Lianchao & Tingting, 2020), deliberately ruminative individuals proactively replenish their resource pool and invest resources in resilience.

We furthermore take a contingency perspective to understand when salespersons' ruminative thinking styles exert strong influence on their resilience. Through the COR lens (Hobfoll, 1989), job demand may interfere with pathways from a resource form to another (i.e., resource caravan pathways). Hence, as a form of job demand (Agnihotri, Gabler, Itani, Jaramillo, & Krush, 2017), customer demandingness may play a moderating role for resource caravan pathways from ruminative processes (cognitive resources) to resilience.

Our study contributes to the stream of research on workforce resilience through crises in the B2B context. First, we extend this research stream by investigating employer event communication as a novel social antecedent of salesperson resilience particularly in face of a crisis. Our study not only responds to a call for further investigations into the predicting role of different forms of social support in the equation of resilience (Cooke, Cooper, et al., 2019; Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019) but also fills a gap in general business, wherein, as reflected in our review in Table 1 and the recent narratives of resilience in the workplace (Bal, 2020; Hartmann et al., 2020), worker resilience research has focused heavily on employee-oriented mechanisms such as human resource management (HRM) and leadership.

Second, it proposes sales employees' intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination as mediation mechanisms underlying the nexus between employer event communication and salesperson resilience. Ruminative thinking styles have not been unpacked as mediators to offer a cognitive approach to how social support in general and employer event communication in particular promote resilience among workers. General business research has tended to examine the direct relationship between social support and employee resilience (e.g., Caniëls & Hatak, 2019; Cooke, Cooper, et al., 2019; Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019; Khan et al., 2019) or social mediating mechanisms (e.g., social climate) for such a direct relationship (Cooper et al., 2019). This has thus limited our understanding on how to channel employer event communication into employee resilience.

Third, our study unravels the contingent role of customer demandingness for the translation of salespersons' ruminative processes into their resilience. This is crucial since it improves our understanding regarding when salespersons' different ruminative styles can promote or inhibit the development of their resilience in face of a crisis. Moreover, the finding from this investigation advances our limited understanding of the interaction between job demands (e.g., customer demandingness) and personal resources (e.g., rumination) albeit moderating effects of job resources have been widely examined (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Kimura et al., 2018).

Last, our study provides a contextual insight by testing its model in an Asian context (Vietnam). This is one of the Asian contexts affected by the direct spread of the COVID-19 from China through the border (La et al., 2020). However, compared to China and Western contexts, employee resilience in face of the COVID-19 has been less studied in our research context (Bal, 2020; Mao, He, Morrison, & Andres Coca-Stefaniak, 2020). Further, our research context, which reflects lack of resources and a weak welfare system compared to Western contexts (La et al., 2020), may induce a pattern of salesperson resilience different from the Western one.

2. Hypothesis development

2.1. The conservation of resources (COR) theory

Resources refer to things that individuals value such as object (e.g., material assets), condition (e.g., status), personal (e.g., knowledge, skills, abilities, traits), and energy (e.g., time, effort) resources (Hobfoll, 1989). Resources under the COR theory are hence not limited to financial or material resources but comprise psychosocial resources such as social support (Hobfoll, Johnson, Ennis, & Jackson, 2003). Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl, and Westman (2014) further refined and defined resources as things perceived by individuals as helping fulfil their goals. For instance, salespeople can perceive social support as a resource to help them face the market crisis and achieve as much as they can for sales performance goals.

The fundamental tenet of the COR theory is that individuals are inclined to conserve or protect their current resources (resource conservation) and amass new resources (resource acquisition). From this fundamental tenet emerge some theoretical principles. First, experiencing that their resources are threatened, lost, or not replenished after being expended, or there is a lack of gains from invested resources, individuals may develop a negative psychological state (e.g., stress) (Hobfoll, 1989). Therefore, work-related resource gains will assume greater meaning in face of resource losses (e.g., garnering social support during the market crisis) (Halbesleben et al., 2014). This principle further indicates that individuals are inclined to engage in behaviors that help evade or mitigate resource losses due to such a profound negative impact of resource losses on psychological state (Halbesleben et al., 2014).

The second COR principle is resource investment, which is a way to shield against and recover from resource losses, and accrue further resources (Hobfoll, 2001). Proactive coping entails stemming future resource losses through resource investment (Ito & Brotheridge, 2003). Resource investment is an intricate process activated by resource availability and investment instrumentality (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Individuals with a resource pool to draw from (resource availability) have higher propensity and greater opportunity to invest resources (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Accruing resources, individuals are in a better position to invest and garner more resources (resource gain spiral) (Hobfoll, 2001). Furthermore, they have the inclination to invest resources for future returns on such investments (investment instrumentality) (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2015). With perceptions of resource availability and investment instrumentality, individuals are prone to adopt a proactive, rather than defensive, strategy to invest their current resources to develop a positive psychological state and behaviors above the minimum expectations (e.g., proactive behavior, adaptative behavior, action-focused growth) (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2007; Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2007).

In line with the view of the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) as being related to human adaptation (Hou et al., 2010) and resilience (Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019), our study will adopt this theory to cast light on how event communication from employer functions as a social resource to help salespeople grow resilient through the COVID-19 crisis. Prior studies have used the COR theory to elucidate the role of social support resources such as leader resilience (Fan et al., 2020), supportive leadership (Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019), co-worker support (Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019; Kuntz et al., 2017), and learning organization (Malik & Garg, 2020) in nurturing employee resilience.

2.2. Employer event communication and salesperson resilience

Definitions of resilience share two key components comprising positive adaptation and context of adversity or complexity (Herrman et al., 2011; Malik & Garg, 2020). In line with these facets, in this study, resilience refers to “developable capacity to rebound or bounce back from adversity, conflict, failure, or even positive events, progress, and increased responsibility” (Luthans, 2002, p. 702).

Resilience helps individuals cope effectively with adverse conditions such as traumatic experiences or major life events (e.g., Raghavan & Sandanapitchai, 2019; Waugh, Fredrickson, & Taylor, 2008). Resilient individuals develop positive emotionality such as enthusiastic and optimistic attitude towards life and work (Cooke, Cooper, et al., 2019; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). They are inquisitive and open to new experiences (Cooke, Cooper, et al., 2019) as well as develop proactive learning and growth through conquering challenges (Youssef & Luthans, 2007).

Effective communication in a crisis entails delivering precise information, reshaping individuals' perceptions, remedying negative impacts, and encouraging individuals to undertake appropriate behaviors (Liu-Lastres, Schroeder, & Pennington-Gray, 2019). An organization may utilize event communication ecologies to (a) connect with employees, (b) correct inaccurate reports about the organization's event-related policies, and (c) confirm information about employees' situation during the event (Spialek & Houston, 2018).

Social support is a resource that enables a person to conserve valued resources (Hobfoll, 1989). In comparison with employees without social support, those with such support cope psychologically better (Blustein, Kozan, & Connors-Kellgren, 2013; Milner, Krnjacki, Butterworth, & LaMontagne, 2016). As a form of social support, communicative processes can help alleviate employees' repetitive thoughts on the negative consequences of the event and develop positive attitudes since, through communicative processes, employees can receive care and express their emotions constructively as well as develop clear understanding of their organization's event-related policies (Spialek, Houston, & Worley, 2019). Since resilience requires educating members to enhance their repertoires of understanding and action (Ford, 2018), employer event communication, through education, may enhance employee resilience. Positive emotions and experiences can promote psychological capabilities and thought-action skills, which are a source of resilience (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009; Cooper et al., 2019; Malik & Garg, 2020). Triggering employees' positive emotions and ‘upward-spiral’ can promote their resilience (Cooper et al., 2019; Luthans, Avey, Avolio, Norman, & Combs, 2006).

Communicative processes can enable employees not only to engage with non-negative thoughts about the event, but also to derive potential benefits from the event and adopt a future-oriented perspective (Spialek et al., 2019; Walsh, 2007). Resources that are formed from event communication from the employer may help employees proactively and effectively re-establish cognitive balance and make sense of the event (Lianchao & Tingting, 2020; Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019). This is in tune with the COR perspective that with ample resources, individuals have the propensity to think and act proactively (Halbesleben et al., 2014) such as in the form of adaptation and resilience (Hobfoll et al., 2007).

Furthermore, individuals can develop positive psychological state when their need for personal relationships and social interactions is fulfilled (Bowlby, 1969; Lakey & Orehek, 2011). Hence, sense of community and social contact that employer event communication builds can foster positive psychological state among salespersons facing the COVID-19 crisis, leading them to appreciate life, alleviate perceived risk, and proactively develop resilience (Bonanno et al., 2007; Hobfoll et al., 2007; Masten, 2001). Additionally, high levels of trust that employees have in their organization through employer event communication serve as crucial antecedents to employee resilience (Cooper et al., 2019; Cummings & Worley, 2014). Employees who trust their organizations are inclined to feel supported and proactively seek assistance (Cooper et al., 2019; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). Through employer event communication, dialogue and inquiry offer employees opportunities to articulate their concerns to the organization, which can make them feel valued, leading to the development of their resilience (Malik & Garg, 2017; Purcell, Kinnie, Swart, Rayton, & Hutchinson, 2008). Moreover, well-supported employees are inclined to display networking-oriented resilient behaviors (e.g., proactively seeking support and connecting with others across the areas of expertise), and further build the supportive network to address challenges and develop resilience (Kuntz et al., 2017; Nilakant et al., 2016).

Regardless of no research on the link between employer event communication and employee resilience in face of a crisis, prior research has provided some empirical implications on the relevance of communication to salesperson resilience. For instance, analyzing the data collected from 510 employees from information technology firms in India, Malik and Garg (2017) reported the impact of organizational efforts in inquiry and dialogue on employee resilience. Based on the two samples of 268 employees from an organization in the finance sector and 115 employees from a civil engineering organization in New Zealand, Hodliffe (2014) investigated the predictive role of corporate communication for employee resilience. Kim (2016) conducted a study on 313 employees working in the medium and large firms in the United States to garner evidence for the impact of organizations' symmetrical communication and transparent communication on employee resilience. The above discussion leads us to formulate that:

H1

Employer event communication is positively related to salesperson resilience.

2.3. Mediating mechanism of rumination

2.3.1. Intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination

Rumination refers to a cognitive process in which individuals re-construct their assumptions that guide their understanding and reasoning of life or stressful events as well as their actions (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Albeit salespeople are likely to face stressful events (Kraft, Maity, & Porter, 2019; Miao & Wang, 2017), rumination has been less understood in the sales literature (Dunstan, 2016). Individuals can cognitively process an event in the two forms comprising intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination (Cann et al., 2011). Intrusive rumination is a destructive rumination form in which repetitive thoughts against individuals' volition undermine their control of the situation, while deliberate rumination is a constructive rumination form that reflects individuals' proactive endeavors to regain the control and make sense of the event (Calhoun et al., 2010; Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019; Wu, Zhou, Wu, & An, 2015).

In the few studies that have examined employee rumination in the management literature in general and in the marketing research in particular, rumination has been viewed as a form of introspection dwelling passively on the negative facets of one's current situation (Goussinsky, 2020; Kemp, Borders, & Ricks, 2013). In other words, this research stream has looked at rumination in the form of intrusive thinking rather than both ruminative thinking styles. In Kemp et al.'s (2013) study, salesperson rumination has been found to enhance emotional exhaustion. In a study on service employees, Goussinsky (2020) found that rumination exacerbates the impact of customer aggression on service sabotage. Baranik, Wang, Gong, and Shi's (2017) study on call-center customer representatives revealed that cognitive rumination was negatively related to well-being and job performance and positively related to emotional exhaustion and customer sabotage, as well as functioned as a mediation mechanism for the effect of customer mistreatment on employees' emotional exhaustion, well-being, job performance, and customer sabotage.

2.3.2. Intrusive rumination as a mediator

Individuals may fail to cope psychologically and let their thoughts of negative consequences of an event invade their assumptive world against their volition when they feel their resource pool depleted (Kemp et al., 2013). Negative psychological state as a result of resource depletion (Hobfoll, 1989; Sörensen, Rzeszutek, & Gasik, 2019) may engender cognitive imbalance, leading to intrusive rumination (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). By helping individuals restore their depleted resource pool as well as their cognitive balance (Spialek et al., 2019), event communication from the employer may reduce their repetitive rumination about the negative consequences of the event. Social support has been reported to attenuate anxieties about stressors and leverage problem-focused coping behaviors as opposed to destructive rumination (Kemp et al., 2013). In other words, as a social support resource, employer event communication may exert a negative effect on intrusive rumination, as in the hypothesis that follows:

H2a

Employer event communication is negatively related to salesperson intrusive rumination.

Intrusive rumination tends to be positively linked with psychological distress and negatively linked with well-being (Hill & Watkins, 2017). Further, high in intrusive rumination, individuals are inclined to focus on the negative consequences of the event (Eze et al., 2020). Intrusive rumination may therefore maintain one's negative affects and prolong the negative impacts of stressors (e.g., impacts of the COVID-19 crisis), which may result in reduced self-efficacy and more experiences of negative emotions (Baranik et al., 2017; Denson, Spanovic, & Miller, 2009). These effects of intrusive rumination may prevent individuals from developing the appreciation of life and the confidence to become resilient.

Moreover, since intrusive rumination hampers individuals' recovery and undermines problem-solving ability (Schmaling et al., 2002), individuals who engage in intrusive rumination are less likely to actively seek the meaning of the event as well as new possibilities. Hence, intrusive rumination may undermine the development of resilience among salespersons.

Taken together, we posit that:

H2b

Intrusive rumination is negatively related to salesperson resilience.

H2c

Intrusive rumination mediates the relationship between employer event communication and salesperson resilience.

2.3.3. Deliberate rumination as a mediator

Employer event communication is a source of resources for employees (Spialek et al., 2019; Walsh, 2007). In light of the COR perspective, with resources from the communication from the employer, sales employees are inclined to proactively garner further resources, develop a positive psychological state, and take active coping strategies (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2007; Ito & Brotheridge, 2003). Resources from employer communication may thus help employees proactively re-construct cognitive balance, which activates their deliberate rumination process (Lianchao & Tingting, 2020; Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019). Cognitive balance drives individuals to actively ruminate on the clues of the event and build the meaning from it (Zhou, Wu, Fu, & An, 2015). Expressed differently, employer event communication can represent a resource to nurture deliberate rumination among sales employees during the pandemic crisis:

H3a

Employer event communication is positively related to salesperson deliberate rumination.

Through altering the perception of the event, alleviating event-related negative effects (Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019), and reconstructing the meaning from the event (Zhou et al., 2015), deliberately ruminative employees may develop positive emotions, which may result in the development of personal psychological capabilities (Fredrickson, 2001). Positive emotions contribute to an upward spiral of social, physical, and psychological resources (Fredrickson, 2001). These resources enable individuals to cope with adversity and “un-do” some of the impacts of negative emotions (Richard, 2020), thereby facilitating their resilient growth (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009; Malik & Garg, 2020).

Moreover, when making sense of the event (Zhou et al., 2015), deliberately ruminative sales employees may develop the appreciation of life. Deliberate rumination further fuels individuals' efforts to find a resolution (Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019) and develop problem-solving coping behaviors (Lianchao & Tingting, 2020), which may lead to their engagement in seeking new possibilities and opportunities. Furthermore, by interpreting cues in the context, individuals make sense of it, which in turn rationalizes behavioral development (Wu, Wu, & Yuan, 2019). Hence, by interpreting cues from and making sense of the event through the employer communication, salespersons may proactively look for new life paths through the event. In other words, deliberate rumination may nurture salesperson resilience through the crisis. In juxtaposition with prior reasoning, we can postulate the following:

H3b

Deliberate rumination is positively related to salesperson resilience.

H3c

Deliberate rumination mediates the relationship between employer event communication and salesperson resilience.

2.4. Customer demandingness as a moderator

The last decade has witnessed growing customer demands for organizations and their salespersons (Agnihotri et al., 2017; Banin et al., 2016). Customer demandingness refers to the degree and sophistication of customers' requirements for products' specifications and performance (Li & Calantone, 1998). Customers are also more demanding in respect of experience (O'Hern & Kahle, 2013) and perceived value (Flint, Blocker, & Boutin Jr, 2011). Customer demandingness may signify a gap between a customer’ requirements and the offered product or service, or customer expectations that the organization is unconscious of (Wang & Netemeyer, 2002). The upsurge in customer demandingness is induced by the rising competition between organizations, the enhanced access to information (Itani, Jaramillo, & Paesbrugghe, 2020), and the continuing trend of customer empowerment (Verbeke, Dietz, & Verwaal, 2011). Many companies recognize the salience of customer demandingness as it reflects a synopsis of market trends such as competitors' offerings, customization requirements, and technology advancement (Itani et al., 2020; Wang & Netemeyer, 2002).

Salesperson behaviors can be positively or negatively influenced by customer demandingness (Banin et al., 2016). Customer demandingness may undermine the impact of sales employees' improvisation on their sales performance (Banin et al., 2016). It may also cause stress among salespersons by depleting their resources (Jaramillo, Mulki, & Boles, 2013). Nevertheless, as customers become more demanding, companies may be prompted to learn specific customer needs and bolster their activities to produce needs-satisfying products or services with superior value (Bharadwaj & Dong, 2014; Wheelwright & Clark, 1992). Customer demandingness may drive salespeople to add a new set of value-providing and problem-solving abilities to their traditional portfolio (Jaramillo et al., 2013). Customer demandingness has been reported to have positive effects such as enhancing improvisation (Banin et al., 2016), creativity (Wang & Netemeyer, 2004), and sales efforts (Jaramillo & Mulki, 2008). In this study, we argue that customer demandingness will play a moderating role for the relationship between two ruminative thinking forms and salesperson resilience. This assumption is in line with the resource caravan tenet in the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), which underscores the role of demands (e.g., customer demandingness) in regulating the transfer of a personal resource (e.g., ruminative thinking) to another (e.g., resilience).

As earlier discussed, individuals with intrusive rumination tend to let their repetitive thoughts of the negative consequences of the situation undermine their volition, cognitive balance, and problem-solving ability. Salespeople may perceive excessive pressure imposed by increased workload from increased customer demands (Banin et al., 2016) if their volition and ability to control and cope with the situation are undermined by intrusive rumination (Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019; Schmaling et al., 2002). Therefore, under customer demandingness, salespeople with intrusive rumination may develop further negative thoughts and become less likely to be resilient.

With their focus on negative consequences of the event (Eze et al., 2020), intrusively ruminative salespeople have a depleted resource pool, which may get further depleted by customer demands (Agnihotri et al., 2017). Through the COR lens (Hobfoll, 1989), facing a resource loss, individuals are inclined to develop a negative psychological state and behave defensively rather than proactively invest their limited resources in resilient growth. In other words, the negative relationship between intrusive rumination and salesperson resilience may be further pronounced as intrusively ruminative salespersons' resource pool is further depleted by customer demandingness. The above reasoning leads us to expect the moderating role of customer demandingness:

H4

Customer demandingness moderates the negative relationship between intrusive rumination and salesperson resilience such that this relationship is stronger at a higher level of customer demandingness.

Customer demandingness may drive salespersons to engage in serving customers even beyond their assigned roles (Agnihotri et al., 2017; Banin et al., 2016). This is more likely to occur among deliberately ruminative salespersons during the pandemic crisis, since, focusing on positive aspects of the crisis (Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019), sales employees with high deliberate rumination value any orders from customers and find demands from customers as opportunities to make sense of the crisis. Customer demandingness may indicate a gap between customer requirements and the product offering (Li & Calantone, 1998), which may be greater due to supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis (Hartmann & Lussier, 2020; Okorie et al., 2020). Deliberately ruminative salespeople tend to make sense of such a gap and in turn enhance their activities to close the gap. Such salespeople focus on diagnosing customer requirements and generating a broader array of potential solutions to satisfy customers' complex requirements (Bharadwaj & Dong, 2014) particularly in the crisis. Stated differently, deliberately ruminative sales employees are inclined to make more sense of the crisis and become more resilient if they are further driven by customer demandingness during the crisis.

Moreover, in light of the COR theory, salespersons need to manage internal resources upon facing demands such as increased customer complexity (Agnihotri et al., 2017), which require augmented cognitive demands (Schmitz & Ganesan, 2014). To manage internal resources to address customer demands, salespeople may draw resources that they have planned to dedicate elsewhere or accrue additional resources (Agnihotri et al., 2017). Deliberately ruminative salespeople, who proactively restore the control of the situation and make sense of it (Lianchao & Tingting, 2020; Ogińska-Bulik & Kobylarczyk, 2019), tend to proactively accrue further resources as a way to manage internal resources in response to customer demandingness. Garnering further resources, deliberately ruminative salespeople are inclined to further invest them in resilient growth (Bonanno et al., 2007; Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2007). Expressed differently, in face of customer demandingness, deliberate rumination may further enhance salesperson resilience. Hence, we postulate that:

H5

Customer demandingness moderates the positive relationship between deliberate rumination and salesperson resilience such that this relationship is stronger at a higher level of customer demandingness.

Fig. 1 is the illustration of the construct relationships in our research model.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

3. Research methods

3.1. Sampling

Vietnam reported its first two COVID-19 cases on 23 January 2020, and implemented early response measures relating to health system preparedness and international travel restrictions (Vietnamplus, 2020). With increasing confirmed cases in early March, some districts in some provinces implemented a lockdown. On 1 April 2020, a complete national lockdown was imposed (Vietnamplus, 2020) and still in place at the time of our data collection (between mid-March and mid-May 2020) with relaxations applied according to the severity of the COVID-19 in different provinces.

After the lunar new year holiday, businesses in Vietnam resumed their activities around early February 2020 (Nga, Dao, & Huong, 2020). Businesses and workers had been working for the first quarter targets for few weeks (Nga et al., 2020) when supply chain disruptions commenced to occur mainly due to the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in China on Chinese supplies and consumptions (Majumdar, Shaw, & Sinha, 2020). These disruptions, along with the COVID-19 spread in Vietnam, have impacted workers' attitudes, performance, and job security (ILO in Vietnam, 2020).

Our study utilized the snowball sampling technique, a non-probability sampling approach, to recruit manufacturing companies for targeting salespeople as participants. Via a researcher's connections with five manufacturing companies, we were further connected to other companies. This sampling technique was used due to the lack of availability of the sampling frame, which is a vital requirement for probability sampling approaches (Upadhyay, Khandelwal, Nandan, & Mishra, 2018). Snowballing entails the use of some members of the group of interest to approach other members (Yadav, Dokania, & Pathak, 2016). Its advantage involves garnering responses from a large number of relevant participants (Baltar & Brunet, 2012; Yadav et al., 2016). Since snowballing is capable of providing an understanding of a subject (e.g., a manufacturing company) that has hitherto been concealed by a veil of ignorance (Alder & Clark, 2006), it can partially offset its limitation in data generalization (Hair, Money, Samouel, & Page, 2007). This technique also helps enhance the chance of reaching not only industrial sectors but also individuals in industrial companies and target groups such as salespeople (Yadav et al., 2016). Snowballing has been used to approach salespeople in prior studies (Kooli, Tzempelikos, Foroudi, & Mazahreh, 2019; Nanarpuzha & Noronha, 2016; Upadhyay et al., 2018).

When receiving the support for the surveys from the chief executive or managing director of each company, we approached HR managers for the list of sales employees. Dillman, Smyth, and Christian's (2014) Tailored Design Method was adopted to render the survey process respondent-friendly and enhance the response rate. We first sent salespersons an advance-notice email to introduce the study objectives, warrant the confidentiality and anonymity in participating in the survey, and invite their voluntary participation. Salespeople were offered a financial incentive of Vietnam dong150,000 (= USD6.5) as a reward for completing the online survey. We then sent them the survey link including a covering letter, a questionnaire, and instructions for filling out the survey. The first reminder was sent 1 week after sending the survey link and the second reminder was sent 1 week after the first reminder. Thank-you emails were also sent to survey participants.

Data were collected in the two survey waves with a 6-week time lag (Wang & Huang, 2019). The first wave measurement (T1) harvested the data on employer event communication, intrusive rumination, and deliberate rumination. The data regarding control variables were garnered in this survey wave as well. In the second measurement time (T2), salespersons participating in T1 were invited to provide the data on customer demandingness and salesperson resilience.

The separation of the independent construct variables from the dependent ones through this multi-wave survey process may allay common method variance risk (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). Moreover, mediation paths should be estimated based on the data collected from at least two measurement waves (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). The assessment of the moderator variable (i.e., customer demandingness) at the same time as the outcome variable (i.e., resilience) is of little concern, given that common method variance can produce bias capable of attenuating (rather than inflating) the strength of the parameter estimates in moderation tests (Podsakoff et al., 2012; Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, 2010).

Since our model posits that employees develop deliberate rumination and in turn resilience under the influence of employer event communication, we chose a 6-week time lag, which was long enough to capture a gradual development of deliberate rumination since deliberate rumination tends to occur a while after the event (Eze et al., 2020). However, this time lag was not so long that our postulated relationships might become confounded with the impacts of the COVID-19 control measures in the country.

We removed data from sales departments in which there were under five respondents (Chuang & Liao, 2010) as prior research has reported that with groups of five or more respondents, biases in utilizing aggregate scores dwindle (Bliese, 2000; van Woerkom & Sanders, 2010). Nordén-Hägg, Sexton, Kälvemark-Sporrong, Ring, and Kettis-Lindblad (2010) further indicated that reliable consensus scores can be yielded via the use of five participants as a minimum threshold. After this data removal, participants who completed the two wave surveys consisted of 447 salespersons (response rate: 63.8%) from 46 manufacturing companies (79.3%). The company sample reflected mixed industries as presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Demographic attributes.

| Frequency | % | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.09 | ||

| 18–25 years old | 132 | 29.53 | |

| 26–35 | 148 | 33.10 | |

| 36–45 | 71 | 15.88 | |

| 46–55 | 62 | 13.87 | |

| > 55 | 34 | 7.60 | |

| Gender | 0.43 | ||

| Female | 191 | 42.72 | |

| Male | 254 | 56.82 | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 0.44 | |

| Educational level | 1.75 | ||

| High school degree or lower | 137 | 30.64 | |

| Bachelor's degree or equivalent | 281 | 62.86 | |

| Master's degree or higher | 29 | 6.48 | |

| Organizational tenure | 5.05 | ||

| ˂ 3 years | 141 | 31.54 | |

| 3 – ˂ 5 years | 149 | 33.33 | |

| 5 – ˂ 10 years | 112 | 25.05 | |

| 10 years or over | 45 | 10.06 | |

| Industries | |||

| Automobiles | 3 | 6.52 | |

| Textiles, wearing apparel, and leather products | 5 | 10.86 | |

| Rubber and plastics products and other non-metallic mineral products | 5 | 10.86 | |

| Machinery and equipment | 4 | 8.69 | |

| Wood and paper products and printing | 3 | 6.52 | |

| Basic metals and metal products | 3 | 6.52 | |

| Electrical equipment | 3 | 6.52 | |

| Computer electronic and optical products | 5 | 10.86 | |

| Chemicals and chemical products | 3 | 6.52 | |

| Food products, beverages, and tobacco | 4 | 8.69 | |

| Others | 8 | 17.39 |

In light of Armstrong and Overton's (1977) suggestion, non-response bias was tested through a comparison of the responses from early wave participants and late wave participants in terms of demographic variables. Student's t-tests demonstrated no significant disparities between these two groups of participants. It is hence concluded that the results would not be affected by non-response bias (Dillman et al., 2014).

3.2. Measures

The questionnaire was first constructed in English and then translated into Vietnamese in light of Schaffer and Riordan's (2003) back-translation approach. Measurement items are displayed in Table 3 . Content validity was warranted since the scale items were derived and adapted from the established measures and based on suggestions in terms of clarity, specificity, and representativeness from ten judges including four academics and six practitioners in the field (Dillman, 2000; Haynes, Richard, & Kubany, 1995).

Table 3.

Measurement items.

| Constructs and items | Standardized loading | t Value |

|---|---|---|

| Employer event communication (α = 0.81; CR = 0.81; AVE = 0.62) | ||

| The company corrected rumors about its policies related to the COVID-19 crisis. | 0.79a | |

| The company encouraged us not to spread rumors about the COVID-19 crisis and its policies related to the crisis. | 0.83 | 11.62 |

| The company encouraged us to correct inaccurate information about the COVID-19 crisis and its policies related to the crisis. | 0.80 | 9.95 |

| The company corrected inaccurate information about the COVID-19 crisis and its policies related to the crisis. | 0.77 | 9.58 |

| The manager talked to us to explore how we experienced the crisis. | 0.85 | 11.86 |

| The manager talked to us to see if we were safe. | 0.81 | 10.42 |

| The manager talked to us to confirm whether reports about the COVID-19 crisis were true. | 0.24b | 2.83 |

| The manager talked to us to see if we were OK during the COVID-19 crisis. | 0.78 | 9.67 |

| The manager comforted us during the COVID-19 crisis. | 0.82 | 10.74 |

| The company looked for information to confirm whether we received its crisis-related reports. | 0.84 | 10.78 |

| The company looked for information to find out what was going on for employees during the COVID-19 crisis. | 0.81 | 10.92 |

| The company looked for information to confirm whether we received an event warning. | 0.27b | 3.19 |

| Resilience (α = 0.83; CR = 0.82; AVE = 0.75) | ||

| I know what I want to achieve during my lifetime. | 0.84a | |

| I have a strong determination to achieve certain things in my lifetime. | 0.82 | 10.85 |

| My current work is a step towards achieving certain things in my lifetime. | 0.88 | 12.67 |

| I know what I have to do to achieve my aspirations in life. | 0.83 | 10.51 |

| I am ambitious to achieve certain things during my lifetime. | 0.79 | 9.92 |

| I have a get up and go approach to life. | 0.83 | 11.81 |

| I know what to do in most situations. | 0.81 | 10.34 |

| I have a powerful self-interest in achieving what I want. | 0.86 | 12.75 |

| I enjoy the company of other people most of the time. | 0.80 | 10.19 |

| I have a unique personal brand that I frequently project to others. | 0.76 | 9.63 |

| I always listen to and try to understand what others are talking to me about. | 0.85 | 11.58 |

| I have a curiosity about people. | 0.84 | 11.26 |

| I share my innermost secrets with a selected number of friends. | 0.81 | 10.53 |

| I have a strong relationship with those who can help me achieve what I want. | 0.86 | 12.90 |

| I have got friends to provide me with the emotional support I need. | 0.81 | 10.74 |

| I see myself as self-sufficient. | 0.83 | 11.19 |

| I enjoy challenge and solving problems. | 0.78 | 9.22 |

| I really enjoy exploring the causes of problems. | 0.86 | 12.43 |

| I can solve most problems that challenge me. | 0.82 | 10.71 |

| I help others solve the problems and challenges they face. | 0.80 | 10.08 |

| I like to plan out my day and write down my list of things to do. | 0.83 | 10.57 |

| I plan my holidays well in advance. | 0.25b | 3.94 |

| I tackle big tasks in bite sizes. | 0.84 | 10.86 |

| I review my achievements weekly. | 0.86 | 11.42 |

| I know how to tackle most challenges I face. | 0.82 | 10.18 |

| I like taking the lead. | 0.77 | 9.24 |

| I feel comfortable in new situations. | 0.87 | 12.71 |

| I know I'm a great person. | 0.79 | 9.06 |

| I approach a new situation with an open mind. | 0.82 | 10.65 |

| I am able to adjust to changes. | 0.85 | 11.93 |

| I can easily find ways of satisfying my own and other people's needs during times of change and conflict. | 0.81 | 10.47 |

| I am able to accommodate other people's needs whilst focusing on achieving my own ambitions. | 0.82 | 9.84 |

| I view change as an opportunity. | 0.86 | 11.72 |

| When an unwelcome change involves me, I can usually find a way to make the change benefit myself. | 0.80 | 9.38 |

| I am able to focus my energy on how to make the best of any situation. | 0.75 | 9.21 |

| I believe my own decisions and actions during periods of change will determine how I am affected by the change. | 0.81 | 10.59 |

| Intrusive rumination (α = 0.80; CR = 0.79; AVE = 0.64) | ||

| I thought about the event when I did not mean to. | 0.78a | |

| Thoughts about the event came to mind and I could not stop thinking about them. | 0.81 | 10.42 |

| Thoughts about the event distracted me or kept me from being able to concentrate. | 0.84 | 11.29 |

| I could not keep images or thoughts about the event from entering my mind. | 0.76 | 9.87 |

| Thoughts, memories, or images of the event came to mind even when I did not want them. | 0.79 | 9.23 |

| Thoughts about the event caused me to relive my experience. | 0.85 | 12.36 |

| Reminders of the event brought back thoughts about my experience. | 0.82 | 11.81 |

| I found myself automatically thinking about what had happened. | 0.81 | 10.19 |

| Other things kept leading me to think about my experience. | 0.83 | 10.83 |

| I tried not to think about the event, but could not keep the thoughts from my mind. | 0.80 | 9.75 |

| Deliberate rumination (α = 0.86; CR = 0.86; AVE = 0.72) | ||

| I thought about whether I could find meaning from my experience. | 0.85a | |

| I thought about whether changes in my life have come from dealing with my experience. | 0.82 | 10.27 |

| I forced myself to think about my feelings about my experience. | 0.88 | 12.63 |

| I thought about whether I have learned anything as a result of my experience. | 0.84 | 11.39 |

| I thought about whether the experience has changed my beliefs about the world. | 0.86 | 12.71 |

| I thought about what the experience might mean for my future. | 0.83 | 11.94 |

| I thought about whether my relationships with others have changed following my experience. | 0.81 | 9.25 |

| I forced myself to deal with my feelings about the event. | 0.88 | 12.82 |

| I deliberately thought about how the event had affected me. | 0.84 | 11.29 |

| I thought about the event and tried to understand what happened. | 0.87 | 12.34 |

| Customer demandingness (α = 0.85; CR = 0.84; AVE = 0.67) | ||

| The clients I serve are demanding in regard to product/service quality and reliability. | 0.82a | |

| My clients have high expectations for service and support. | 0.85 | 11.71 |

| My clients require a perfect fit between their needs and our product/service offering. | 0.28b | 3.48 |

| My clients expect me to deliver the highest levels of product and service quality. | 0.87 | 12.16 |

Fixed item.

Excluded item.

Employer communication related to the COVID-19 event was measured using twelve items (1 = never; 5 = always) adapted from Spialek and Houston's (2018) event citizen disaster communication scale. Salesperson resilience was measured utilizing Wang, Cooke, and Huang's (2014) 36-item scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), which have been used in recent resilience works such as Cooke, Cooper, et al. (2019); Cooke, Wang, and Bartram (2019). Intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination were assessed by ten items each from Cann et al. (2011), 1 = not at all; 5 = often). Customer demandingness was gauged via four items from Wang and Netemeyer (2002) (1 = true for none of my clients; 5 = true for all of my clients). This study controlled for employees' gender, age, education, and organizational tenure by virtue of the relevance of these demographic attributes to employee attitudinal and behavioral responses (Augustine, 2014; Fu & Deshpande, 2014).

3.3. Data analysis strategy

Through the lens of Krull and MacKinnon's (2001) typology and Preacher, Zhang, and Zyphur's (2011) suggestion, our model has a 2–1–1 design in which the impact of the level 2 (company level) variable (employer event communication) on the level 1 outcome variable (salesperson resilience) is mediated by the level 1 constructs (salesperson intrusive and deliberate rumination).

As such, our data were hierarchically structured with individuals nested within companies. Hence, as per Preacher et al.'s (2011) suggestion, multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) was implemented using MPlus version 7.2. Following Muthen and Muthen's (1998-2012) view, maximum likelihood estimation was used with robust standard errors. Through MSEM, the variance of level 1 variables is decomposed into within-level and between-level components, which are modelled concurrently and independently at each level. This will reduce the conflation of the level 1 and level 2 relationships and allow a more precise assessment of indirect relationships (Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010).

As proposed by Peccei and Van De Voorde (2019), to verify the appropriateness of multilevel analysis, we estimated between-firm variances by calculating intra-class correlations 1 (ICC1s), ICC2s, and rwg values for all model constructs. ICC1s for employer event communication, intrusive rumination, deliberate rumination, employee resilience, and customer demandingness were 0.24, 0.17, 0.26, 0.22, and 0.19 respectively, while their ICC2s were 0.72, 0.66, 0.75, 0.71, and 0.73 respectively. These values were greater than the median value of 0.12 for ICC1 suggested by James (1982) and Glick's (1985) 0.60 cutoff point for ICC2. The rwg average value was 0.77 [0.73, 0.86] for employer event communication, 0.72 [0.68, 0.83] for intrusive rumination, 0.81 [0.76, 0.90] for deliberate rumination, 0.75 [0.71, 0.87] for salesperson resilience, and 0.74 [0.70, 0.84] for customer demandingness, surpassing Klein et al.'s (2000) cutoff threshold of 0.70. These significant between-firm variances lent support for multilevel modeling.

With 2.94 as the highest value, variance inflation factors (VIF) fell under Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson's (2010) 5.0 threshold value. Along with the tolerance above the 0.3 cutoff point (Hair et al., 2010), these results demonstrated a low concern for multi-collinearity. Multi-collinearity risk was further mitigated by multiplying the mean-centered values of the predictor variables to yield interaction terms (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

3.4. Common method variance (CMV)

CMV risk might be mitigated in this study via ensuring participant anonymity, reducing item ambiguity, and utilizing multi-wave surveys to collect data (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Nonetheless, as all constructs in the current research were estimated through participants' perspectives, and the data were garnered from the same source (i.e., employees), CMV bias might emerge in the data. CMV bias was hence statistically tested using Lindell and Whitney's (2001) marker variable approach. The marker variable “attitude toward social media usage” was added to the survey on account of its theoretical unrelatedness to other constructs. The removal of the marker variable did not affect the significance of the significant zero-order correlations, revealing the low risk of CMV bias. Significant interactional effects lent further credence to this low risk since high CMV bias tends to deflate interactional effects (Siemsen et al., 2010).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic analysis

Demographic attributes, consisting of employees' age, gender, educational level, and organizational tenure, as well as industries are presented in Table 2 with reference to frequency, percentage, and mean of each attribute.

4.2. Measurement models and construct validity

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) unveiled a decent fit between the hypothetical five-factor model and the data (χ2/df = 347.26/179 = 1.94 < 2, TLI = 0.95, IFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, SRMRwithin = 0.043, SRMRbetween = 0.095; RMSEA = 0.048 [0.042, 0.057]). It was a better fit than the fits of alternative models, which were constructed by combining construct variables (see Table 4 ). These results lent credence to discriminant validity among the constructs. Discriminant validity was further attained due to the fact that each construct's correlations with the other constructs were exceeded by the square root of its average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (Table 5 ). Discriminant validity issue was also addressed through the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) (Voorhees, Brady, Calantone, & Ramirez, 2016). For each pair of constructs, the HTMT criteria were calculated on the basis of the item correlations. Further endorsement for discriminant validity of the estimated scales was provided through the computed values, which fell within the range between 0.17 and 0.62, meeting Kline's (2011) 0.85 threshold.

Table 4.

Comparison of measurement models.

| Models | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | TLI | IFI | CFI | SRMR within | SRMR between | RMSEA [90% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical five-factor model | 347.26 | 179 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.043 | 0.095 | 0.048 [0.042, 0.057] | |

| Four-factor model 1: Intrusive rumination and deliberate rumination combined | 382.49 | 183 | 35.23⁎⁎ | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.064 | 0.107 | 0.066 [0.060, 0.075] |

| Four-factor model 2: Event communication and intrusive rumination combined | 409.92 | 183 | 62.66⁎⁎ | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.087 | 0.121 | 0.090 [0.081, 0.096] |

| Three-factor model: Event communication, intrusive rumination, and deliberate rumination combined | 468.75 | 186 | 121.49⁎⁎ | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.106 | 0.138 | 0.104 [0.098, 0.112] |

| Two-factor model: All antecedent variables combined | 510.48 | 188 | 163.22⁎⁎ | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.119 | 0.156 | 0.122 [0.115, 0.131] |

| One-factor model: All variables combined | 602.94 | 189 | 255.68⁎⁎ | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.145 | 0.183 | 0.151 [0.137, 0.159] |

p < .01.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix and average variance extracted.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Employee age | ….. | ||||||||

| 2. Employee gender | −0.02 | ….. | |||||||

| 3. Employee education | 0.05 | 0.03 | ….. | ||||||

| 4. Employees' organizational tenure | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | ….. | |||||

| 5. Employer event communication | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | (0.79) | ||||

| 6. Customer demandingness | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | (0.82) | |||

| 7. Resilience | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.36⁎⁎⁎ | 0.13 | (0.87) | ||

| 8. Intrusive rumination | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.31⁎⁎ | 0.22⁎ | −0.14 | (0.80) | |

| 9. Deliberate rumination | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.38⁎⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎ | (0.85) |

| Mean | 33.09 | 5.05 | 3.59 | 3.65 | 4.24 | 3.02 | 3.91 | ||

| SD | 6.57 | 1.86 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.44 | ||

| CCR | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.86 | ||||

| AVE | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.72 |

CCR = Composite construct reliability, AVE = Average variance extracted.

Values in parentheses exhibit the square root of the average variance extracted.

Standardized correlations reported ⁎p < .05; ⁎⁎p < .01; ⁎⁎⁎p < .001.

Convergent validity of the constructs was warranted since the factor loadings of the scale items surpassed 0.50 in tandem with the t-values exceeding 2.0 (see Table 3) (Hair et al., 2010). Convergent validity was further evidenced as the average variance extracted of all constructs surpassed 0.50 (see Table 3) (Hair et al., 2010).

4.3. Unidimensionality and reliability

First, the unidimensionality of the constructs was ensured through the good model fit in the CFA results discussed above (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). Second, construct unidimensionality was further supported since the first eigenvalues ranged between 2.24 and 2.62, exceeding 1.0 cutoff point (Rencher, 1995), loadings on the target construct surpassed 0.60, and cross-loadings with other constructs did not go beyond 0.40 (Hair et al., 2010; Zaim, Muhammed, & Tarim, 2019).

Construct reliability was tested using Cronbach's α, total-item correlation, and composite reliability. As shown in Table 3, the values for Cronbach's α ranged between 0.80 and 0.86, exceeding 0.75 (Robinson, 2018). The correlations between the items on each scale surpassed 0.50, and the values for composite reliability exceeded 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). These results lent credence to the internal consistency and reliability in the scales.

4.4. Hypothesis testing

As presented in Table 6 , hypothesis H1 on the positive nexus between employer event communication and salesperson resilience was evidenced via the positively significant coefficient (B = 0.34, p < .01). The significantly negative coefficient (B = −0.29, p < .01) provided support for hypothesis H2a regarding the negative relationship between employer event communication and salespeople's intrusive rumination. Nevertheless, hypothesis H2b on the negative effect of intrusive rumination on salesperson resilience was not corroborated due to the non-significant coefficient (B = −0.13, p > .10). Hypothesis H3a postulating the positive link between employer event communication and deliberate rumination was statistically supported due to the positively significant coefficient (B = 0.36, p < .001). The positively significant coefficient (B = 0.42, p < .001) lent credence to hypothesis H3b on the positive effect of deliberate rumination on salesperson resilience.

Table 6.

Findings.

| Hypothesis | Description of path | Path coefficient (Unstandardized) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Event communication → Resilience | 0.34⁎⁎ (0.11) | Supported |

| H2a | Event communication → Intrusive rumination | −0.29⁎⁎ (0.08) | Supported |

| H2b | Intrusive rumination → Resilience | −0.13 (0.05) | Unsupported |

| H3a | Event communication → Deliberate rumination | 0.36⁎⁎⁎ (0.14) | Supported |

| H3b | Deliberate rumination → Resilience | 0.42⁎⁎⁎ (0.10) | Supported |

| H2c | Event communication → Intrusive rumination → Resilience | 0.03 (0.01) [−0.17, 0.04] | Unsupported |

| H3c | Event communication → Deliberate rumination → Resilience | 0.15⁎ (0.07) [0.03, 0.28] | Supported |

| H4 | Intrusive rumination × Customer demandingness → Resilience | 0.24⁎ (0.08) | Supported |

| H5 | Deliberate rumination × Customer demandingness → Resilience | 0.17⁎ (0.06) | Supported |

⁎p < .05; ⁎⁎p < .01; ⁎⁎⁎p < .001. Standard errors are portrayed in parentheses.

The indirect effect of employer event communication on salesperson resilience through the mediating role of intrusive rumination was 0.03 (SE = 0.01, p > .10). The result from the Monte Carlo test indicated that 95% confidence interval (CI) for the coefficient distribution varied from −0.17 to 0.04 with zero residing in the range, which lent no credence to hypothesis H2c on the mediation mechanism of intrusive rumination for the relationship between employer event communication and salesperson resilience. Hypothesis H3c, however, was evidenced on account of the significant indirect effect of employer event communication on salesperson resilience via deliberate rumination as a mediator (0.15 [0.03, 0.28], SE = 0.07, p < .05).

The term of the interaction between intrusive rumination and customer demandingness (hypothesis H4) was positive and significant (B = 0.24, p < .05). The interactional graph, as shown in Fig. 2 , indicated that intrusive rumination reduced salesperson resilience to a greater extent under conditions of high customer demandingness (simple slope = −0.68, p < .05) than under conditions of low customer demandingness (simple slope = −0.16, p < .05). These results provided endorsement for hypothesis H4.

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect of customer demandingness for the relationship between intrusive rumination and salesperson resilience.

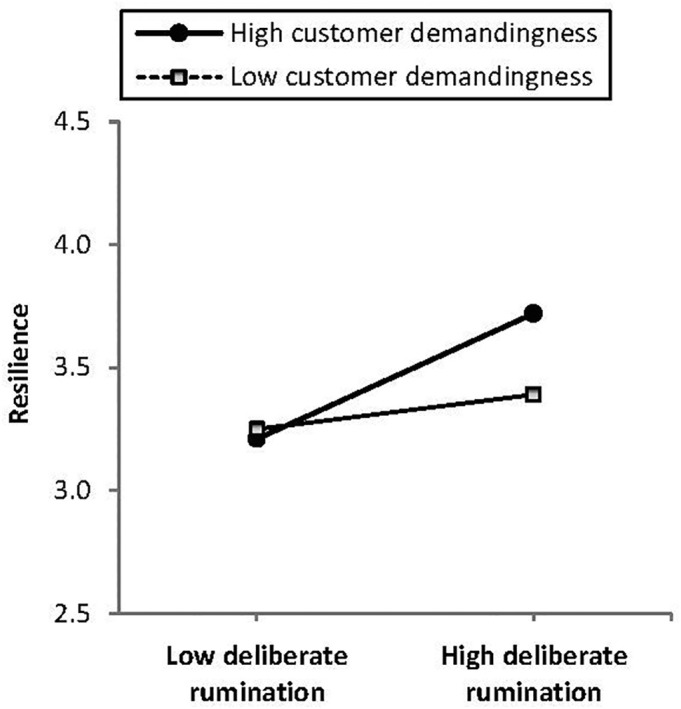

Hypothesis H5 was supported on account of the significantly positive interaction term (B = 0.17, p < .05) for the interactional effect of deliberate rumination and customer demandingness on salesperson resilience. The slope test graph for this interaction (Fig. 3 ) demonstrated that deliberate rumination was more positively related to salesperson resilience at high levels of customer demandingness (simple slope = 0.51, p < .05) than at its low levels (simple slope = 0.14, p < .05).

Fig. 3.

Moderating effect of customer demandingness for the relationship between deliberate rumination and salesperson resilience.

As a supplementary analysis, the squared terms of the independent variables were added to the model. No significant relationships were found between the squared term of employer event communication and intrusive rumination (B = −0.13, p > .10) as well as deliberate rumination (B = 0.16, p > .10). No significant relationships were further found between the squared intrusive rumination term and salesperson resilience (B = −0.08, p > .10) as well as between the squared deliberate rumination term and salespersons resilience (B = 0.15, p > .10). However, the squared term for employer event communication demonstrated a marginally significant and positive relationship with salesperson resilience (B = 0.19, p = .07), which indicates a weak curvilinear relationship between employer event communication and salesperson resilience. The curve reached its minimum point at 3.47, which was slightly below the mean of 3.59 (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Curvilinear relationship between employer event communication and salesperson resilience.

5. Discussions

5.1. Theoretical implications

Our research contributes to the employee resilience literature in five major ways. First, our study extends the stream of research on resilience from a crisis in general and in the B2B sales domain in particular by examining how B2B salespersons grow resilient in face of the COVID-19 crisis. This distinguishes our study from the extant research, as shown in the review in Table 1, which has mainly investigated resilience from crises, including pandemics, at the macro levels such as organizations (Cankurtaran & Beverland, 2020; Rapaccini et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020; Zafari et al., 2020) or industries (Okorie et al., 2020; Remko, 2020). Research has been scarce in terms of resilience among workers during a crisis, particularly in the sales context (Peasley et al., 2020).

Second, our finding provides evidence for the role of employer event communication in predicting salesperson resilience in face of the COVID-19 crisis (hypothesis 1). As reflected in the summary in Table 1, employee resilience research has largely focused on HRM (e.g., Cooke, Cooper, et al., 2019; Cooper et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019; Nadeem et al., 2019) or leader support or leadership (Cooke, Wang, & Bartram, 2019; Franken et al., 2020; Kakkar, 2019; Sommer et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2019). Our study extends this stream of research by adding employer event communication to the growing body of contextual or social antecedents for employee resilience.

Furthermore, communication has been identified as an effective tool and a social support resource to shape workers' attitudinal and behavioral responses (Petrou, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2018), especially in the B2B realm (Jiménez-Castillo, 2016; Reece, 2018; Suzuki, Ando, & Nishikawa, 2019). However, the role of employer communication of the event has not been unravelled in research on sales workforce in the face of crisis events. Our findings highlight the magnitude of employer communication as a resource particularly for individuals who work in areas vulnerable to crises such as B2B sales (Cortez & Johnston, 2020; Hartmann & Lussier, 2020).

The supplementary analysis further indicates that the non-linear relationship could occur between employer event communication and salesperson resilience. This curvilinear relationship denotes that different mechanisms may be responsible for salesperson resilience at both ends of the spectrum of employer event communication. At the high end, the integration of the different resources from employer event communication, including correcting, connecting, and confirming may yield a positive, synergistic impact on salesperson resilience. Contrarily, in response to a low level of employer event communication, employees may be more inclined to rely on themselves to cope with the crisis. This is in line with prior studies reporting that employees may count on their own resources such as self-awareness and self-efficacy to maintain resilience (O'Dowd et al., 2018).