Abstract

It has been reported that dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibition protects against acute lung injury (ALI). Anagliptin is a novel selective inhibitor of DPP4 but its role in ALI has not been studied. The present study aimed to investigate the effects of anagliptin on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell (HPMVEC) injury, as well as its underlying mechanism. HPMVECs were exposed to LPS in the presence or absence of anagliptin co-treatment. MTT assay was used to evaluate cell viability and nitric oxide (NO) production was detected using a commercial kit. DPP4 and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression levels, apoptosis and migration were assessed via reverse transcription-quantitative PCR, western blotting, TUNEL staining and wound healing assay, respectively. Western blot analysis was performed to assess expression levels of proteins involved in NF-κB signaling, cell apoptosis and migration, as well as high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)/receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). LPS decreased cell viability and NO production, but elevated expression of DPP4 in HPMVECs. LPS promoted pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, NF-κB activation and cell apoptosis, but inhibited cell migration and phosphorylated-AKT/endothelial NO synthase expression. Anagliptin co-treatment significantly restored all of these effects. Mechanistically, the upregulation of HMGB1/RAGE expression induced by LPS was markedly blocked by anagliptin. In conclusion, anagliptin alleviated inflammation, apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction in LPS-induced HPMVECs via modulating HMGB1/RAGE expression. These data provide a basis for use of anagliptin in ALI treatment.

Keywords: anagliptin, apoptosis, dipeptidyl peptidase-4, lung injury, inflammation

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a diffuse inflammatory reaction in the lung caused by various internal and external pathogenic factors, such as sepsis, pneumonia and trauma (1,2). ALI, which is characterized by respiratory distress, refractory hypoxemia and respiratory failure, is the primary cause of death in critically ill patients with sepsis at present (3). Bacterial infection, shock, severe trauma, sepsis and other factors induce the occurrence of ALI (4). Although the rapid development of medical technology has provided better treatment of ALI, the specific mechanism underlying its pathogenesis has not been fully elucidated and there is a lack of effective drug treatments in clinical use (5,6).

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4), also known as CD26, is a widely expressed serine membrane-anchored peptidase that exists on the surface of various types of cell (7). Its expression level varies from cell to cell (8,9). In different organs and tissues (such as lung, muscle and heart), DPP4 activity is associated with its presence in the microvasculature (10). Clinical and experimental research over the past 30 years has demonstrated the involvement of DPP4 in various physiological processes and diseases of immune system (11,12). Recent experimental studies have shown that DPP4 inhibition protects the lungs against severe injury and relieves associated respiratory disease, including COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) caused by MERS coronavirus (13-17), suggesting that DPP4 inhibitors may be used to decrease LI. A previous study proposed that the DPP4 inhibitor Saxagliptin attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis (18). Another DPP4 inhibitor, vildagliptin, has been demonstrated to alleviate pulmonary fibrosis in LPS-induced LI by inhibiting endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) (19).

Anagliptin, a novel selective inhibitor of DPP4, was licensed for clinical treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in 2012(20). Anagliptin has been shown to alleviate inflammation and endothelial cell injury. For example, anagliptin prevents H2O2-induced apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (21). Anagliptin ameliorates high glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction via suppression of NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome activation (22). Anagliptin inhibits neointimal hyperplasia via endothelial cell-specific modulation of superoxide dismutase-1/Ras homolog family member A/JNK signaling in the arterial wall (23). Recent comprehensive review articles indicated that DPP4 inhibitors (anagliptin, vildagliptin and sitagliptin) developed and marketed for their beneficial effects display multipotency in the management of various types of pulmonary disease (14,24). Seys et al (17) demonstrated that anagliptin displays a stronger anti-inflammatory action than sitagliptin. Another study suggested that anagliptin improves LI in mice under chronic stress, potentially by mitigating vascular inflammation (25). However, whether anagliptin relieves LPS-induced human (H)PMVEC injury remains to be elucidated.

In the present study, the effect of anagliptin on viability, inflammation, apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction of HPMVECs exposed to LPS, along with its underlying mechanism, were investigated. The present study aimed to provide a basis for the use of anagliptin in ALI treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

HPMVECs were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (cat. no. CRL-3244) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 37˚C with 5% CO2. For LPS stimulation, cells were exposed to 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 37˚C for 24 h. For anagliptin treatment, cells were exposed to various concentrations of anagliptin (1, 10, 50 or 100 µM; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 37˚C for 24 h. For LPS and anagliptin co-treatment, cells were sequentially exposed to 100 ng/ml LPS plus designated concentrations of anagliptin (10, 50 or 100 µM) at 37˚C for 24 h.

Cell viability assessment

MTT assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was utilized to detect cell viability. Briefly, HPMVECs were seeded into 96-well plates (5x104 cells/well) and incubated at 37˚C to 90% confluence. Subsequently, cells were exposed to various concentrations of anagliptin (1, 10, 50 or 100 µM) or LPS ± anagliptin for 24 h. Then, 50 µl MTT solution was added to each well and maintained for 3 h at 37˚C. Cells were exposed to 150 µl DMSO and shaken on an orbital shaker for 15 min, then absorbance of each well was measured at 590 nm.

Measurement of NO production

The generation of NO in culture medium was measured using an NO assay kit (cat. no. S0023; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) in accordance with manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cultured cells were harvested and centrifuged at 8,000 x g for 15 min at room temperature. The culture supernatant of cells was added to 96-well plates (50 µl/well). After samples were incubated with 50 µl Griess Reagent for 3 min at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm.

Western blot analysis

HPMVECs were lysed using RIPA buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) containing cocktail inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and quantified using a Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay kit (Abcam). Samples (40 µg per lane) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to 0.45 µM PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). After being blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1.5 h at room temperature, samples were probed with primary antibodies overnight at 4˚C and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. 7074P2; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at room temperature for 2 h. Bands were visualized using ECL (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and quantified with ImageJ software (Version 6.0; National Institutes of Health). The following antibodies from Abcam or Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., were used (all at a dilution of 1:1,000): Anti-DPP4 (cat. no. ab215711); anti-p65 (cat. no. ab32536), anti-Lamin B (cat. no. 17416S), anti-phosphorylated (p)-IκBα (cat. no. 2859T), anti-total (t)-IκBα (cat. no. 4812S), anti-Bcl-2 (cat. no. 4223T), anti-Bax (cat. no. 5023T), anti-apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (APAF-1; cat. no. 8969T), anti-cleaved-caspase3 (cat. no. 9664T), anti-caspase3 (cat. no. 9662S), anti-AKT (cat. no. 4691T), anti-p-AKT (cat. no. 4060T), anti-endothelial NO synthase (eNOS; cat. no. 32027S), anti-inducible (i)NOS (cat. no. 20609S), anti-high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1; cat. no. 6893S), anti-receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE; cat. no. 6996S) and anti-GAPDH (cat. no. 5174T).

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 5 µg RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using TaqMan One-Step RT kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Amplification was performed using SYBR Green PCR kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd) and ABI Prism 7500 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The following thermocycling conditions were used for qPCR: Initial denaturation for 10 min at 95˚C; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 15 sec and annealing/extension at 55˚C for 45 sec. The primers were as follows: DPP4 forward, 5'-TCTGCTGAACAAAGGCAA TGA-3' and reverse, 5'-CTGTTCTCCAAGAAAACTGAGC-3'; tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α forward, 5'-CATCCAACCTT CCCAAACGC-3' and reverse, 5'-CGAAGTGGTGGTCTTGT TGC-3'; IL-1β forward, 5'-GAGCTCGCCAGTGAAATG ATG-3' and reverse, 5'-TAGTGGTGGTCGGAGATTCG-3'; IL-6 forward, 5'-GTCCAGTTGCCTTCTCCCTG-3' and reverse, 5'-CTGAGATGCCGTCGAGGATG-3'; C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) forward, 5'-AGATCTGTGCTGAC CCCAAG-3' and reverse, 5'-GGAGTTTGGGTTTGCTTG TCC-3'; and GAPDH, forward, 5'-GCAACCGGGAAGGAAAT GAATG-3' and reverse, 5'-CCCAATACGACCAAATCAG AGA-3'. Results were normalized to GAPDH expression and 2-ΔΔCq was used to calculate the relative change in gene expression (26).

TUNEL staining

TUNEL assay was used to detect the apoptosis of HPMVECs. Briefly, after cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, apoptosis was detected using a TUNEL assay kit (cat. no. QIA33; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions; 50 µl TUNEL reaction mixture was added for 1 h at 37˚C. The cells were treated with DAPI (2 µg/ml) to stain the nucleus at 37˚C for 2-3 min. After washing twice with PBS, images were captured from three fields of view using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation; x200 magnification).

Wound healing assay

HPMVECs were cultured in 6-well plates (5x105 cells/well) to 70-80% confluence. The cell surface was scratched with a 100-µl pipette tip to create an artificial wound, and medium was replaced with serum-free RPMI-1640 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing LPS ± anagliptin and cultured for 24 h at 37˚C. Images were captured at 0 and 24 h using an inverted light microscope (magnification, x100; Olympus Corporation). The cell migration rate was calculated as follows: (Width at 0 h-width at 24 h)/width distance. The relative migration rate was obtained by normalizing to the untreated group.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed with SPSS 21.0 software (IBM Corp). All experiments were performed in triplicate. An unpaired Student's t-test was used for comparisons between two groups. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

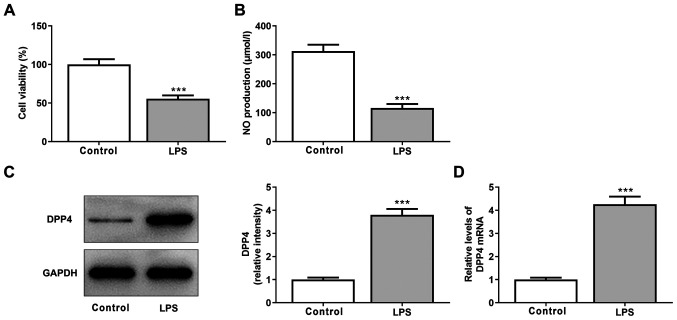

DPP4 expression is increased following LPS stimulation in HPMVECs

HPMVECs were exposed to 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h to simulate ALI in vitro. Viability and NO production of cells significantly decreased following LPS stimulation, indicating that LPS induced HPMVEC damage (Fig. 1A and B). Furthermore, both protein and mRNA expression levels of DDP4 were significantly increased following LPS treatment of HPMVECs, suggesting that DDP4 expression is increased in LPS-induced HPMVEC injury (Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1.

LPS impairs cell viability and NO production and upregulates DPP4 expression in HPMVECs. (A) HPMVECs were cultured in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h, then cell viability was measured using MTT assay. (B) NO production was tested by NO assay kit. DPP4 (C) protein and (D) mRNA expression levels were detected by western blotting and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR, respectively. ***P<0.001 vs. control. HPMVEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell; NO, nitric oxide; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4.

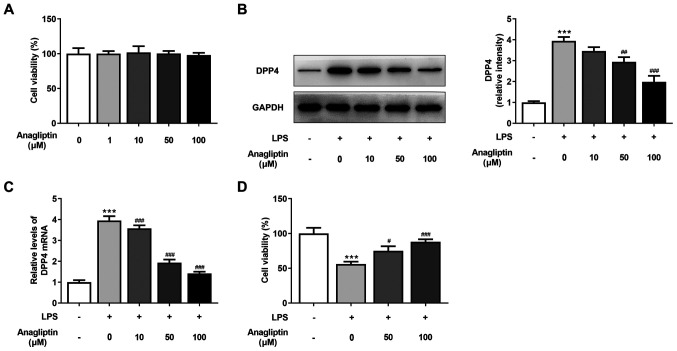

DPP4 inhibitor anagliptin inhibits LPS-induced decrease in HPMVEC viability

Cells were stimulated with different concentrations of anagliptin (0, 1, 10, 50 and 100 µM) for 24 h. Cell viability was not altered following stimulation using different doses of anagliptin (Fig. 2A). RT-qPCR and western blot analysis were performed to detect DDP4 expression. The results revealed that anagliptin (10 µM) decreased mRNA and protein expression levels of DPP4, but this was not significantly different compared with the LPS-alone group (Fig. 2B and C). Additionally, 50 or 100 µM anagliptin significantly decreased DPP4 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2B and C) when compared to the LPS-alone group. The LPS-induced impaired cell viability was rescued by co-treatment with 50 and 100 µM anagliptin (Fig. 2D). These results reveal that the DPP4 inhibitor anagliptin suppressed the LPS-induced decrease in HPMVEC viability.

Figure 2.

Anagliptin recovers LPS-induced decreased cell viability and DPP4 expression in HPMVECs. (A) HPMVECs were exposed to different concentrations of anagliptin, then cell viability was measured using MTT assay. HPMVECs were co-treated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of different concentrations of anagliptin for 24 h, then DPP4 (B) protein and (C) mRNA expression levels were detected by western blotting and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR, respectively. (D) Cell viability was measured using MTT assay. ***P<0.001 vs. untreated cells; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. LPS alone. HPMVEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4.

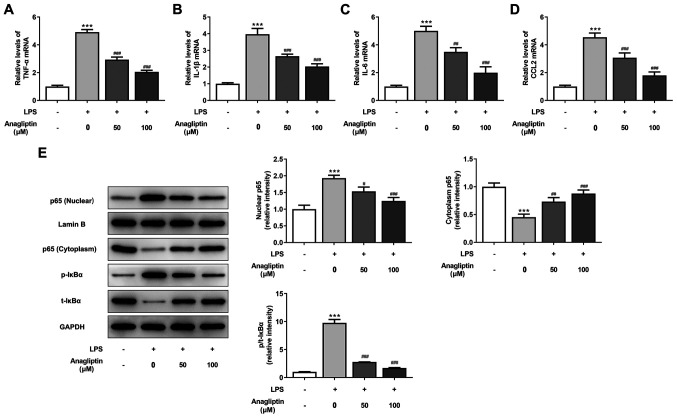

DPP4 inhibitor anagliptin inhibits LPS-induced inflammation and NF-κB activation in HPMVECs

LPS resulted in a significant increase in the expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and CCL2, but 50 and 100 µM anagliptin significantly decreased the expression of these cytokines (Fig. 3A-D). Activation of NF-κB signaling induces the inflammatory response (27). Following LSP treatment, NF-κB signaling was activated, as demonstrated by the significant increase in nuclear p65 expression and p/t-IκBα and the decrease in cytoplasmic p65 in HPMVECs (Fig. 3E). However, following stimulation with 50 or 100 µM anagliptin, nuclear p65 expression and p/t-IκBα expression were effectively suppressed, while the expression of cytoplasmic p65 was upregulated (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Anagliptin inhibits LPS-induced inflammation and NF-κB p65 activation in HPMVECs. HPMVECs were co-treated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of different concentrations of anagliptin for 24 h, then mRNA levels of (A) TNF-α, IL-(B) 1β, (C) IL-6 and (D) CCL2 were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (E) Protein expression of nuclear and cytoplasmic p65 and p/t-IκBα was measured by western blotting. ***P<0.001 vs. untreated cells; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. LPS alone. HPMVEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; p-, phosphorylated; t-, total.

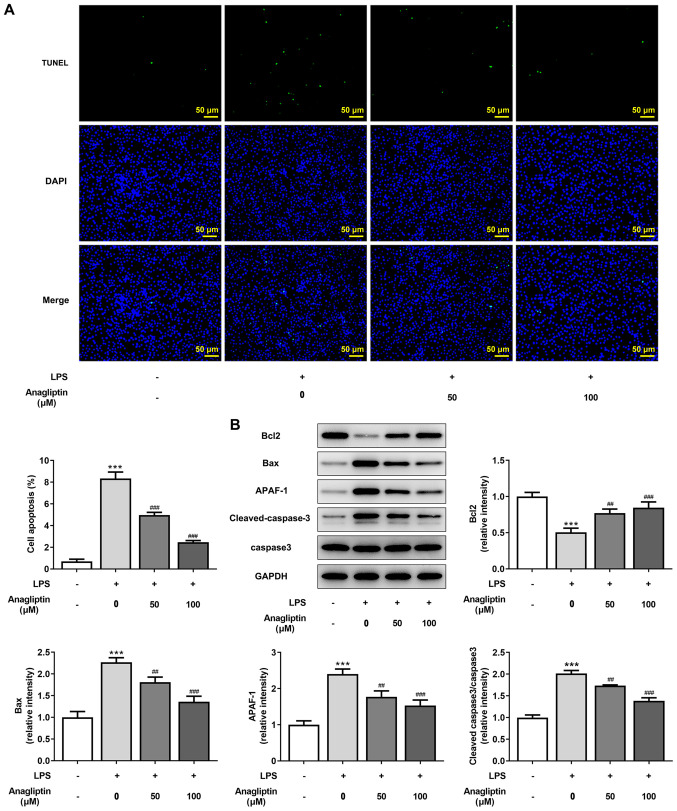

DPP4 inhibitor anagliptin inhibits LPS-induced apoptosis in HPMVECs

TUNEL staining was used to assess cell apoptosis. The number of apoptotic cells was significantly increased following LPS treatment, whereas 50 and 100 µM anagliptin significantly decreased this (Fig. 4A). Consistently, LPS resulted in lower Bcl2 and higher Bax, APAF-1 and cleaved-caspase-3/caspase-3 expression compared with the untreated cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, 50 and 100 µM anagliptin enhanced Bcl2 but decreased Bax, APAF-1 and cleaved-caspase-3/caspase-3 expression levels (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that the DPP4 inhibitor anagliptin inhibited LPS-induced apoptosis in HPMVECs.

Figure 4.

Anagliptin inhibits LPS-induced apoptosis in HPMVECs. (A) HPMVECs were co-treated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of anagliptin for 24 h, then TUNEL staining was performed to observe cell apoptosis. (B) Protein expression levels of Bcl2, Bax, APAF-1 and cleaved caspase3/caspase3 were detected by western blotting. ***P<0.001 vs. untreated cells; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. LPS alone. HPMVEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; APAF-1, apoptotic protease activating factor-1.

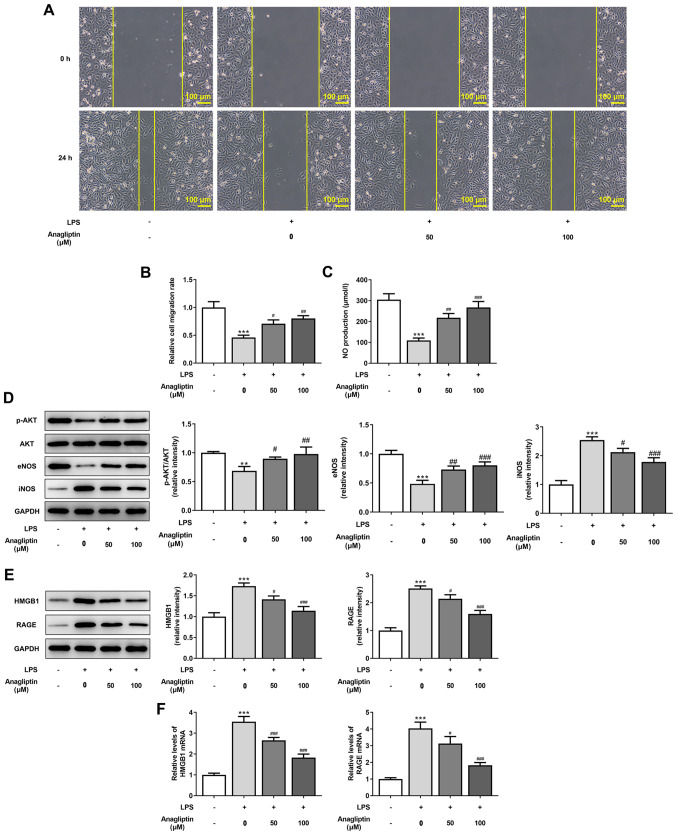

DPP4 inhibitor anagliptin rescues migration and endothelial function and decreases HMGB1/RAGE expression in LPS-treated HPMVECs

Impaired endothelial cell migration and NO production are primary causes of endothelial dysfunction (28). LPS led to a significant decrease in cell migration and NO production, which were effectively rescued by treatment with 50 and 100 µM anagliptin (Fig. 5A-C). Moreover, 50 and 100 µM anagliptin significantly upregulated the decreased expression levels of p-AKT/AKT and eNOS and downregulated the increased expression levels of iNOS induced by LPS (Fig. 5D). The enhanced protein and mRNA expression levels of HMGB1 and RAGE induced by LPS exposure were also significantly downregulated by 50 and 100 µM anagliptin, indicating the inhibitory effect of anagliptin on HMGB1/RAGE expression levels (Fig. 5E and F).

Figure 5.

Anagliptin rescues cell migration and inhibits HMGB1/RAGE expression in LPS-induced HPMVECs. HPMVECs were co-treated with 100 ng/ml LPS in the presence or absence of different concentrations of anagliptin for 24 h. (A and B) Wound healing assay was utilized to assess cell migration. (C) NO production was tested by NO assay kit. (D) Protein expression levels of p-AKT/AKT, eNOS and iNOS and (E) HMGB1 and RAGE were detected by western blotting. (F) mRNA levels of HMGB1 and RAGE were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. untreated cells; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. LPS alone. HPMVEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products; NO, nitric oxide; p-, phosphorylated; eNOS, endothelial NO synthase; i, inducible.

Discussion

The alveolar capillary unit formed by PMVECs is the basic structure that maintains ventilation-perfusion balance, and is susceptible to harmful external stimuli, such as LPS (29). LPS is one of the pathogenic factors leading to abnormal microcirculation in ALI (30,31). In the present study, HPMVECs were exposed to LPS. The results showed that LPS impaired cell viability, NO production and cell migration and induced inflammation, NF-κB signaling activation and apoptosis. However, anagliptin effectively protected HPMVECs against LPS-induced injury, indicating that anagliptin may be used in the treatment of ALI.

Uncontrolled inflammation is the primary pathophysiological basis of ALI (32). The activation of NF-κB signaling induces inflammatory response (27). The present study verified that LPS induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activation of NF-κB signaling, suggesting that inflammatory responses resulted from LPS in HPMVECs. Additionally, the mechanism of ALI is associated with increased vascular endothelial apoptosis and recovery of endothelial cell viability is reported to improve ALI (33). The present study demonstrated an increase in apoptosis ratio and Bax, APAF-1 and cleaved-caspase-3 expression levels, as well as a decrease in Bcl2 expression in LPS-induced cells. As a key molecule in the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, APAF-1 leads to caspase-3 cleavage (34). Therefore, the impaired cell viability caused by LPS may induce inflammation and cell apoptosis. LPS decreased NO production and cell migration along with p-AKT and eNOS expression, but increased iNOS expression. Decreased NO, which is produced by eNOS, and impaired endothelial cell migration are linked to endothelial dysfunction, which results in an imbalance in vascular homeostasis, leading to a prothrombotic and proinflammatory condition (35,36). The AKT/eNOS pathway serves a key role in endothelial mobilization and migration (37). The present results showed that LPS caused endothelial dysfunction of HPMVECs in vitro.

Anagliptin is a novel selective inhibitor of DPP4(38). DPP4 inhibition has been reported to prevent systemic inflammation, vascular dysfunction and end-organ damage in mice with endotoxemia (39). In the study of ALI, DPP4 inhibitor saxagliptin has been reported to decrease LPS-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis (18). Another DPP4 inhibitor, vildagliptin, ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis in LPS-induced LI by inhibiting endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in PMVECs (19). Whether anagliptin inhibits LI is still unknown. The present study demonstrated that anagliptin recovered DPP4 expression, rescued cell viability, inhibited NF-κB activation-mediated inflammation and Bcl2/Bax/APAF-1/caspase3-meditaed apoptosis in LPS-treated HPMVECs. Furthermore, NO production and AKT/eNOS pathway-mediated cell migration, which were impaired by LPS, were all markedly rescued by anagliptin. These data indicated that anagliptin protected HPMVECs against LPS-induced injury.

HMGB1 is a typical damage-associated molecular pattern protein that exerts its biological activity primarily by binding to RAGE. Anagliptin has been verified to suppress HMGB1 expression (40,41). Notably, LPS binds to HMGB1 to serve a key role in endothelial dysfunction (42). The present results showed that LPS significantly upregulated HMGB1 and RAGE expression levels, but anagliptin effectively inhibited this effect. As a result, it was speculated that anagliptin may exert its beneficial role in LPS-induced HPMVEC injury via inhibiting LPS-mediated HMGB1/RAGE upregulation.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the effects of anagliptin on LPS-induced ALI. Anagliptin alleviated LPS-induced HPMVEC injury by the decreasing inflammation, apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction via inhibiting LPS-mediated HMGB1/RAGE upregulation. However, the specific mechanisms involved in the action of anagliptin need to be clarified in subsequent experiments. In addition, safety evaluation and pharmacokinetic studies of anagliptin should be performed in future. These are limitations of the present study and comprehensive and in-depth analysis will be conducted in future to provide further evidence for the treatment of ALI using anagliptin.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author's contributions

JZ and LL contributed to study conception and design and acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. JZ drafted the manuscript. LL revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript. JZ and LL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dushianthan A, Grocott MP, Postle AD, Cusack R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:612–622. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2011.118398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali H, Khan A, Ali J, Ullah H, Khan A, Ali H, Irshad N, Khan S. Attenuation of LPS-induced acute lung injury by continentalic acid in rodents through inhibition of inflammatory mediators correlates with increased Nrf2 protein expression. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;21(81) doi: 10.1186/s40360-020-00458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butt Y, Kurdowska A, Allen TC. Acute Lung Injury: A Clinical and Molecular Review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:345–350. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0519-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes KT, Beasley MB. Pulmonary Manifestations of Acute Lung Injury: More Than Just Diffuse Alveolar Damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:916–922. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0342-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Q, Wang Q, Han C, Yang Y. Sufentanil attenuates inflammation and oxidative stress in sepsis-induced acute lung injury by downregulating KNG1 expression. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22:4298–4306. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt GA. Managing Acute Lung Injury. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piao L, Li Y, Narisawa M, Shen X, Cheng XW. Role of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Humans and Animals with Chronic Stress. Int Heart J. 2021;62:470–478. doi: 10.1536/ihj.20-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yip HK, Lee MS, Li YC, Shao PL, Chiang JY, Sung PH, Yang CH, Chen KH. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 deficiency effectively protects the brain and neurological function in rodent after acute Hemorrhagic Stroke. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:3116–3132. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.42677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee M, Shin E, Bae J, Cho Y, Lee JY, Lee YH, Lee BW, Kang ES, Cha BS. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor protects against non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice by targeting TRAIL receptor-mediated lipoapoptosis via modulating hepatic dipeptidyl peptidase-4 expression. Sci Rep. 2020;10(19429) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75288-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klemann C, Wagner L, Stephan M, von Hörsten S. Cut to the chase: A review of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase-4's (DPP4) entanglement in the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;185:1–21. doi: 10.1111/cei.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y. CD26 in autoimmune diseases: The other side of ‘moonlight protein’. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;75(105757) doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Ke J, Zhu YJ, Cao B, Yin RL, Wang Y, Wei LL, Zhang LJ, Yang LY, Zhao D. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitor sitagliptin alleviates liver inflammation of diabetic mice by acting as a ROS scavenger and inhibiting the NFκB pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(236) doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00625-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki T, Chen W, Htwe YM, Tatsumi K, Dudek SM. DPP4 inhibition by sitagliptin attenuates LPS-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315:L834–L845. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00031.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solerte SB, Di Sabatino A, Galli M, Fiorina P. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibition in COVID-19. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57:779–783. doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01539-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strollo R, Pozzilli P. DPP4 inhibition: Preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or progression of COVID-19? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(e3330) doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou H, Zhu N, Li S. The emerging role of dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 as a therapeutic target in lung disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2020;24:147–153. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1721468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seys LJM, Widagdo W, Verhamme FM, Kleinjan A, Janssens W, Joos GF, Bracke KR, Haagmans BL, Brusselle GG. DPP4, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Receptor, is Upregulated in Lungs of Smokers and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:45–53. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo K, Jin F. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor saxagliptin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via regulating the Nrf-2/HO-1 and NF-κB pathways. J Invest Surg. 2021;34:695–702. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2019.1680777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki T, Tada Y, Gladson S, Nishimura R, Shimomura I, Karasawa S, Tatsumi K, West J. Vildagliptin ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury by inhibiting endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Respir Res. 2017;18(177) doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0660-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roussel R, Duran-García S, Zhang Y, Shah S, Darmiento C, Shankar RR, Golm GT, Lam RLH, O'Neill EA, Gantz I, et al. Double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of continuing or discontinuing the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin when initiating insulin glargine therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: The CompoSIT-I Study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:781–790. doi: 10.1111/dom.13574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Sun J, Chen Y, Su W, Shan H, Li Y, Wang Y, Zheng N, Shan H, Liang H. lncRNA PFAR Promotes Lung Fibroblast Activation and Fibrosis by Targeting miR-138 to Regulate the YAP1-Twist Axis. Mol Ther. 2018;26:2206–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang T, Jiang D, Zhang L, Ding M, Zhou H. Anagliptin ameliorates high glucose- induced endothelial dysfunction via suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediated by SIRT1. Mol Immunol. 2019;107:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Zhang M, Xuan L, Liu Y, Chen C. Anagliptin inhibits neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury via endothelial cell-specific modulation of SOD-1/RhoA/JNK signaling in the arterial wall. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;121:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pantanetti P, Cangelosi G, Ambrosio G. Potential role of incretins in diabetes and COVID-19 infection: A hypothesis worth exploring. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:779–782. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02389-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang S, Li P, Xin M, Jin X, Zhao L, Nan Y, Cheng XW. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition prevents lung injury in mice under chronic stress via the modulation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Exp Anim. 2021;21-0067 doi: 10.1538/expanim.21-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12(86) doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcelo KL, Goldie LC, Hirschi KK. Regulation of endothelial cell differentiation and specification. Circ Res. 2013;112:1272–1287. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan X, Xu S, Zhou Z, Wang F, Mao L, Li H, Wu C, Wang J, Huang Y, Li D, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 alleviates the capillary leakage and inflammation in sepsis. Mol Med. 2020;26(108) doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00221-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T, Yegambaram M, Gross C, Sun X, Lu Q, Wang H, Wu X, Kangath A, Tang H, Aggarwal S, et al. RAC1 nitration at Y32 IS involved in the endothelial barrier disruption associated with lipopolysaccharide-mediated acute lung injury. Redox Biol. 2021;38(101794) doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Wang D, Zhang X, Lv M, Liu G, Gu C, Yang F, Wang Y. Effect and mechanism of phospholipid scramblase 4 (PLSCR4) on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced injury to human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(159) doi: 10.21037/atm-20-7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Lin Z, Lin L. miR-490 alleviates sepsis-induced acute lung injury by targeting MRP4 in new-born mice. Acta Biochim Pol. 2021;68:151–158. doi: 10.18388/abp.2020_5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Chen H, Li H, Zhang J, Gao Y. Effect of angiopoietin-like protein 4 on rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells exposed to LPS. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:568–576. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakeri R, Kheirollahi A, Davoodi J. Apaf-1: Regulation and function in cell death. Biochimie. 2017;135:111–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cyr AR, Huckaby LV, Shiva SS, Zuckerbraun BS. Nitric Oxide and Endothelial Dysfunction. Crit Care Clin. 2020;36:307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng X, Zhang W, Wang Z. Simvastatin preparations promote PDGF-BB secretion to repair LPS-induced endothelial injury through the PDGFRβ/PI3K/Akt/IQGAP1 signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:8314–8327. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Everaert BR, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Hoymans VY, Haine SE, Van Nassauw L, Conraads VM, Timmermans JP, Vrints CJ. Current perspective of pathophysiological and interventional effects on endothelial progenitor cell biology: Focus on PI3K/AKT/eNOS pathway. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:350–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang SM, Jung HS, Kwon MJ, Lee SH, Park JH. Effects of anagliptin on the stress induced accelerated senescence of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(750) doi: 10.21037/atm-21-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steven S, Jurk K, Kopp M, Kröller-Schön S, Mikhed Y, Schwierczek K, Roohani S, Kashani F, Oelze M, Klein T, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signalling reduces microvascular thrombosis, nitro-oxidative stress and platelet activation in endotoxaemic mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:1620–1632. doi: 10.1111/bph.13549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Y, Wang J, Wang C, Zhang Q, Xu Y, Liu H, Xiang X, Ma J. DPP-4 inhibitor anagliptin protects against hypoxia-induced cytotoxicity in cardiac H9C2 cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:3823–3831. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1652624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato A, Suzuki S, Watanabe S, Shimizu T, Nakamura Y, Misaka T, Yokokawa T, Shishido T, Saitoh SI, Ishida T, et al. DPP4 Inhibition Ameliorates Cardiac Function by Blocking the Cleavage of HMGB1 in Diabetic Mice After Myocardial Infarction. Int Heart J. 2017;58:778–786. doi: 10.1536/ihj.16-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Z, Wang J, Xing W, Peng Y, Quan J, Fan X. LPS binding to HMGB1 promotes angiogenic behavior of endothelial cells through inhibition of p120 and CD31 via ERK/P38/Src signaling. Eur J Cell Biol. 2017;96:695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.