Abstract

Gillespie syndrome (GLSP) is characterized by bilateral aniridia, cerebellar hypoplasia with ataxia, congenital hypotonia, and varying levels of intellectual disability. GLSP is caused by either biallelic or heterozygous, dominant-negative, pathogenic variants in ITPR1. Here, we present a five-year-old male with GLSP who was found to have a heterozygous, de novo intronic variant in ITPR1 (NM_001168272.1:c.5935-17G>A) through genome sequencing (GS). Sanger sequencing of cDNA from this individual’s fibroblasts showed the retention of 15 nucleotides from intron 45, which is predicted to cause an in-frame insertion of five amino acids near the C-terminal transmembrane domain of ITPR1. In addition, qPCR and cDNA sequencing demonstrated reduced expression of both ITPR1 alleles in fibroblasts when compared to parental samples. Given the close proximity of the predicted in-frame amino acid insertion to the site of previously described heterozygous, de novo, dominant-negative, pathogenic variants in GLSP, we predict that this variant also has a dominant-negative effect on ITPR1 channel function. Overall, this is the first report of a de novo intronic variant causing GLSP, which emphasizes the utility of GS and cDNA studies for diagnosing patients with a clinical presentation of GLSP and negative clinical exome sequencing.

Keywords: ITPR1, Gillespie syndrome, aniridia, spinocerebellar ataxia, genome sequencing

1. Introduction

Gillespie syndrome (GLSP, OMIM: #206700) is a disorder characterized by symmetric uniform aniridia, congenital hypotonia, cerebellar hypoplasia and ataxia, and varying levels of intellectual disability (Gillespie, 1965). GLSP is caused by pathogenic variants in ITPR1, which encodes the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor type 1 (Carvalho, Medeiros, Ribeiro, Martins, & Sobreira, 2018; Dentici et al., 2017; Gerber et al., 2016; McEntagart et al., 2016; Stendel, Wagner, Rudolph, & Klopstock, 2019). ITPR1 is a subtype of the IP3-receptor family that also includes ITPR2 and ITPR3, which collectively form homo- and heterotetrameric Ca2+-release channels in the endoplasmic reticulum that regulate calcium homeostasis (Foskett, White, Cheung, & Mak, 2007; Yule, Betzenhauser, & Joseph, 2010). The subtypes of ITPRs are expressed variably in all tissue types, with ITPR1 especially highly expressed in both human and mouse brain, particularly within the hippocampus, caudate, putamen, and cerebellar Purkinje cells (Consortium, 2013; Furuichi et al., 1993; Nakanishi, Maeda, & Mikoshiba, 1991; Yamada et al., 1994). ITPR1 consists of an N-terminal IP3 binding domain, a central regulatory domain, and a C-terminal transmembrane pore, (Foskett et al., 2007; Yule et al., 2010).

Pathogenic variants in ITPR1 cause a broad phenotypic spectrum that includes GLSP, spinocerebellar ataxia 15 (SCA15), and spinocerebellar ataxia 29 (SCA29) depending on the location and effect of the variant on protein function (Gerber et al., 2016; Hara et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2012; Iwaki et al., 2008; McEntagart et al., 2016). SCA15 is an autosomal dominant, slowly progressive, cerebellar ataxia that commonly presents in adulthood and is caused by heterozygous loss-of-function variants, typically deletions, in ITPR1 (Hara et al., 2008; Iwaki et al., 2008; Storey et al., 2001; van de Leemput et al., 2007). SCA29 is an autosomal dominant, infantile-onset cerebellar ataxia with mild cognitive impairment that is associated with heterozygous missense variants in ITPR1 (Dudding et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2015; Synofzik et al., 2018). GLSP is distinguishable clinically from SCA15 and SCA29 by the presence of aniridia or partial aniridia, which is not present in the other two disorders (Gerber et al., 2016; Hall, Williamson, & FitzPatrick, 2019; McEntagart et al., 2016). Both autosomal recessive loss-of-function and heterozygous dominant-negative variants in ITPR1 cause GLSP, and these variants cluster frequently near or within the C-terminal transmembrane channel domain of ITPR1 (Dentici et al., 2017; Gerber et al., 2016; McEntagart et al., 2016; Stendel et al., 2019).

We present a 5 year old male with clinical features of GLSP who presented to the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) with a previously non-diagnostic evaluation including trio exome sequencing (ES). From our trio genome sequencing (GS), we identified a de novo, heterozygous intronic variant in ITPR1. This novel variant results in the retention of 15 nucleotides of intron 45, which we predict causes an in-frame insertion of five amino acids within the C-terminal transmembrane domain of ITPR1. We predict that this in-frame insertion has a dominant-negative impact on ITPR1 function. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a de novo, heterozygous, intronic variant associated with GLSP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Editorial Policies and Ethical Considerations.

The patient and his parents were enrolled in the UDN site at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM). Informed consent was obtained prior to all research procedures and included consent to publish photographs. This study was approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the BCM IRB.

2.2. Genome sequencing.

Clinical GS was performed from a blood specimen with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-free 550-bp insert size protocol by the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche) and with sequence analysis on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Sequencing reactions were performed to yield 150 bp paired-end reads. The following quality control metrics of the sequencing data were achieved: average sequenced coverage over the genome > 40X, >97.5% target base (digital exome) covered at >20X, SNP concordance to genotype array: >95%. As a quality control measure, the analysis includes a genotyping assay performed on the Fluidigm SNPtype platform with the SNPTrace Panel. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by a custom analytics pipeline. The output data from the Illumina NovaSeq were converted from BCL files to FastQ files according to each sample's specific adapter sequence according to Illumina's recommended procedure. FastQ data were aligned to the human reference genome build GRCh37 on the Illumina Dragen BioIT Platform. The output of the alignment was a BAM file; QC metrics of the map-align process were recorded for quality review. Variant calling on the BAM file was performed by the Illumina Dragen haplotype-based variant calling system and the output was a VCF file. Variant calling for copy number analyses utilized the Illumina Dragen genome wide depth based CNV caller with custom modifications from Baylor Genetics. Structural variant calling was performed with the Illumina Manta Structural Variant Caller. The annotation platform leveraged the GenomOncology Knowledge Management System API and provided annotations from open source data sets such as gnomAD, EVS, and ClinVar and professional resources such as HGMD Pro. This annotation system reported zygosity as well as inference of mutation types including nonsense, nonsynonymous, splicing and frameshift, among others. Synonymous variants, intronic variants not affecting splicing sites, and common benign variants were excluded from interpretation unless previously reported as possibly pathogenic variants. Note that the interpretation of data was based on our current understanding of the gene and variants at the time of reporting according to ACMG guidelines and patient phenotypes (Richards et al., 2015) .

2.3. cDNA studies.

We performed a skin biopsy on each parent and the proband, and established fibroblast cell lines. RNA was isolated from each cell line as previously described (Murdock et al., 2020), and cDNA was synthesized with the SuperScript® III First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), and reactions were amplified by a Roche LightCycler® 96 Instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Primers were designed to amplify ITPR1 and to amplify GAPDH and HPRT1, two housekeeping genes (Supplemental Table 1). For ITPR1, two sets of primers were used to assess both the 5’ (exons 3 to 5) and 3’ (exons 58 to 59) ends of the cDNA, which contains 61 exons (Supplemental Table 1).

For the cDNA sequencing, we designed primers to amplify exons 12 to 16 and exons 45 to 47 (Supplemental Table 1). We performed PCR with GoTaq® Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) with these primers. We purified the PCR products with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and cloned the PCR products into the pGEM-T® Easy vector with the pGEM®-T Easy Vector System (Promega, Madison, WI). DNA was extracted from bacterial colonies using the QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purified plasmid DNA was submitted to Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ) for Sanger sequencing. SnapGene (www.snapgene.com) was used to view the sequencing results.

2.4. Three-Dimensional Modeling of ITPR1.

To model the location of the predicted five amino acid insertion as compared to the location of the previously described heterozygous, dominant-negative, pathogenic variants (McEntagart et al., 2016) in the three-dimensional protein structure, RSDB Protein Data Bank (RSDB PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/) was used (Sehnal, Rose, Kovca, Burley, & Velankar, 2018). The electron cryomicroscopy structure of the tetrameric mammalian type 1 InsP3R channel (Rattus norvegicus) deposited by Fan et al. was utilized for this analysis (PDB ID = 3JAV) (Fan et al., 2015). Similar to previously published methods (Dentici et al., 2017), we converted the rat amino acid positions to human amino acid positions given the high degree of amino acid identity in rat and human ITPR1 sequence (98%).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical presentation.

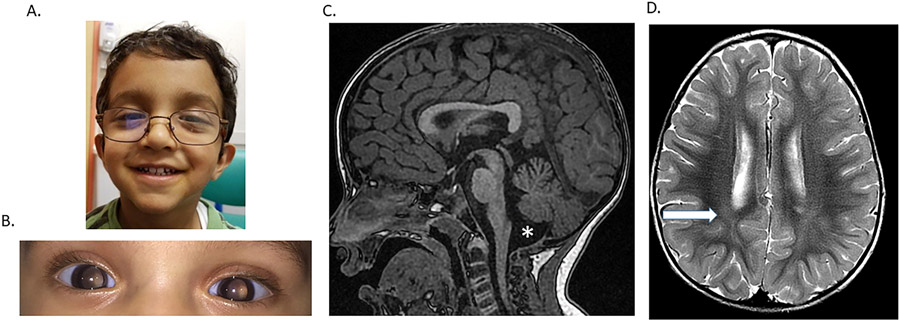

The participant is a 5 year old male who was born full term via vacuum-assisted spontaneous vaginal delivery to a 31 year old G1P0 mother and 32 year old father. Both parents reported Indian ancestry. The pregnancy was complicated only by Hashimoto thyroiditis in the mother that was treated with levothyroxine. Prenatal quadruple screen test and ultrasounds were normal. There were no complications in the immediate postnatal period. However, his pupils were described as fixed and dilated pupils at approximately one month of age (Figure 1). After further ophthalmologic evaluation at age six months, he was diagnosed with bilateral symmetric fixed enlarged pupils with no noticeable scalloping of the iris border. He had persistent pupillary membrane strands extending from a hypoplastic collarette onto the lens and peripheral tunica vasculosa lentis in each eye. At age five years, he was also noted to have a right esotropia in the right eye and moderate hyperopic astigmatic refractive error bilaterally. Otherwise, on repeat examinations over a five-year period, the lens of each eye was clear, retinas appeared normal, and fundus examination was normal with normal foveal light reflex in each eye. He did not have any appreciable nystagmus or signs of glaucoma.

Figure 1.

Patient phenotype. A. Photograph of the proband at 2 years 8 months shows low set and posteriorly rotated ears and possible ocular hypertelorism. B. Photograph of the eye shows aniridia. The eyes were not pharmacologically dilated in this image. C. Sagittal T1-weighted midline image demonstrating mild superior vermian and cerebellar volume loss with associated prominence to the fourth ventricle. D. Axial T2-weighted image at the level of the roofs of the bodies of the lateral ventricles demonstrating increased T2 hyperintensity in the bilateral centrum semiovale (arrow), which is non-specific but has been reported in the literature in association with developmental delays. Myelination is otherwise age appropriate (25 months of age).

At approximately 8 months of age, he was noted to have gross motor delays. He rolled over at 3 months, sat unassisted at 7-8 months, crawled at 15 months, pulled to stand at 15-18 months, stood independently at 24-27 months, and walked with the assistance of orthotics by the age of 2 years 8 months. At 4 years and 11 months of age, his height was at the 71st centile (Z= 0.57), and his weight was at the 34th centile (Z= −0.40) on the Center for Disease Control boys age 2-20 growth curves. His physical examination was notable for low-set and posteriorly rotated ears and apparent ocular hypertelorism (Figure 1). His neurologic examination demonstrated axial and appendicular hypotonia, slight intention tremor, and a wide-based, ataxic gait. Reflexes, muscle bulk, strength, and cranial nerve function were all normal. His speech and language development have always been appropriate for his age, and he performs well in school and has appropriate social skills. Neurocognitive evaluation at age 4 years revealed age-appropriate cognitive functioning although difficulties with fine motor and visual motor skills were noted.

His prior evaluation included a brain MRI at age 25 months of age that showed mild superior vermian and cerebellar volume loss with associated prominence to the fourth ventricle. In addition, there was increased T2 hyperintensity in the bilateral centrum semiovale, (Carvalho et al., 2018) (Figure 1). Laboratory testing included normal CK levels and negative sequencing and deletion/duplication analyses for PAX6, WT1, DCD1, and ELP4. Chromosome analysis, array comparative genomic hybridization, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array, and congenital disorders of glycosylation biochemical analysis (plasma O-glycan profile, carbohydrate deficient transferrin analysis, and N-glycan structural analysis) yielded no abnormalities. He had a non-diagnostic panel for mitochondrial disorders that included mitochondrial genome sequencing and deletion analysis in addition to sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of 319 nuclear genes associated with mitochondrial diseases. Trio ES did not reveal any pathogenic variants. The ES did report a maternally inherited hemizygous variant of uncertain significance in ATP7A, but copper and ceruloplasmin were normal.

3.2. Genome sequencing (GS).

Trio GS revealed a heterozygous de novo intronic variant in ITPR1 (NM_001168272.1:c.5935-17G>A) that was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This variant is not present in gnomAD (Karczewski et al., 2020). In addition, Human Splice Finder predicted a possible impact on splicing (Desmet et al., 2009), and a score of 0.57 in SpliceAI was consistent with a moderate prediction for impact on splicing (Jaganathan et al., 2019). This variant was classified as “likely pathogenic” according to ACMG criteria (Richards et al., 2015). An analysis of the clinical exome sequencing .bam file revealed that this intronic variant was present in the exome data but filtered out during the analysis process. No other rare variants (less than 1% allele frequency in any population in gnomAD) were detected in ITPR1. However, a second heterozygous variant in ITPR1 (NM_001168272.1:c.1435G>A:p.Val479Ile) with allele frequency of 1.063% in the Ashkenazi Jewish population (0.456% overall frequency with six homozygous individuals) in gnomAD was detected (Karczewski et al., 2020). This variant was detected in the mother’s sample and was not detected in the father’s sample. This variant is homozygous in six individuals in gnomAD (Karczewski et al., 2020) and thus was considered likely unrelated to the phenotype of our participant. Analysis of variants in other known genes associated with iris developmental defects revealed no rare variants in PAX6 or FOXC1. However, a homozygous rare variant in the 5’ UTR of PITX2 was detected, but this variant appeared to be homozygous in one unaffected parent. The results of the analysis are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

3.3. Fibroblast cDNA studies.

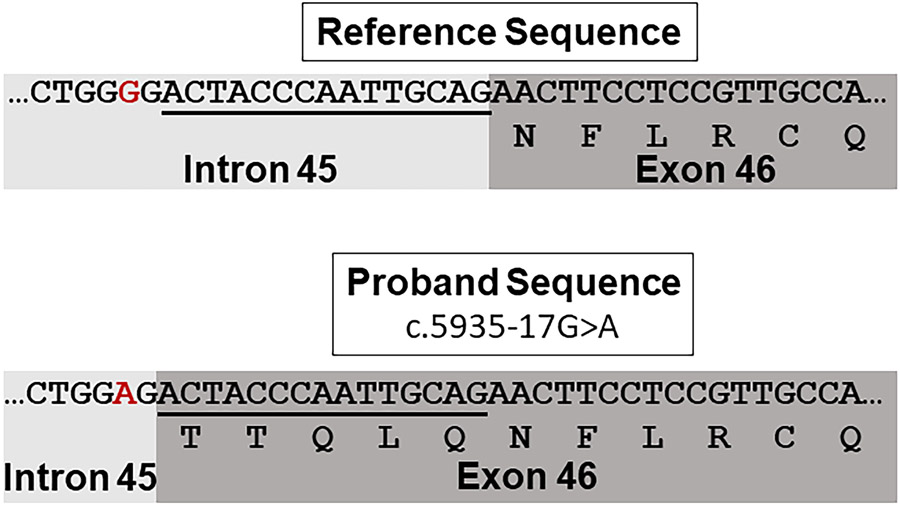

Overall, ITPR1 expression in fibroblasts is low (GTEx TPM = 4.17) and falls below the minimum level (TPM = 10) required to reliably detect statistically significant differences in gene expression using our RNA sequencing pipeline (Consortium, 2013). Thus, to evaluate whether this intronic variant impacts ITPR1 gene expression, we synthesized cDNA from RNA isolated from the fibroblast cell lines derived from the patient and each parent in order to evaluate the impact of the detected variant on ITPR1 expression. qPCR revealed an approximately 50% reduction in ITPR1 gene expression in the patient’s fibroblasts as compared to the parental fibroblasts with primers designed to target both upstream and downstream regions of the transcript (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ITPR1 gene expression is reduced in the proband’s fibroblasts. A. Visual inspection of the RNA-seq alignment (fibroblasts) in IGV demonstrated fewer reads covering exon 46 in the proband compared to controls. B. qPCR was performed using cDNA that was synthesized from RNA isolated from fibroblast cell lines derived from both parents and the proband. Primers were used to amplify exons 3-5 and exons 58-59 of ITPR1 with GAPDH used as a control gene. The studies were repeated with a second control gene (HPRT) with similar results (data not shown). Three technical replicates were run for each individual’s sample.

To determine if the reduction in ITPR1 expression in the patient was associated with reduction from a single or both alleles, we performed cloning and Sanger sequencing of the cDNA to assess for the heterozygous, common, non-synonymous, maternally inherited variant in ITPR1 (NM_001168272.1:c.1435G>A:p.Val479Ile). Detection of both the reference allele and the heterozygous variant in roughly ~50% of clones (5/11 clones) indicated likely balanced biallelic expression of ITPR1 in the patient’s fibroblasts (Supplemental Figure 1).

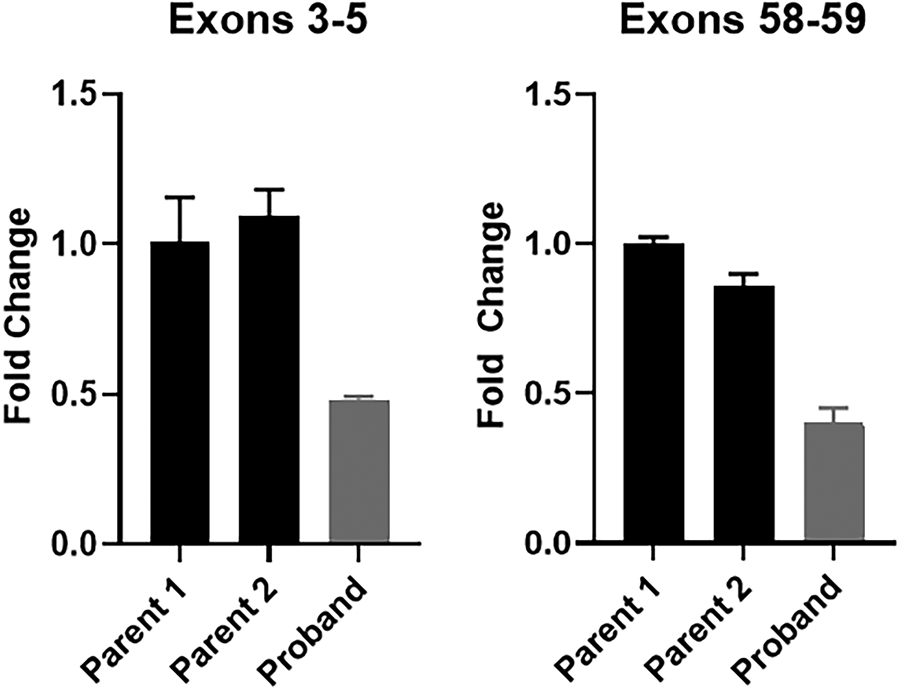

Finally, to determine if the de novo, intronic variant (NM_001168272.1:c.5935-17G>A) affects splicing, cloning and Sanger sequencing was performed with cDNA from the proband’s and each parent’s fibroblast samples with primers located within flanking exons 44 and 48. The Sanger sequencing identified a 15-nucleotide intronic retention in exon 46 in the patient in a subset of clones. This 15-nucleotide intronic retention was not detected in either parent’s sample and is predicted to lead to an in-frame insertion of five amino acids between the glutamine at position 1978 and the asparagine at position 1979 (Supplemental Figure 2, Figure 3). Thus, these results demonstrate that the c.5935-17G>A variant appears to impact splicing and supports its pathogenicity. Moreover, mapping of the amino acid residues at position 1978 and 1979 demonstrate that the predicted amino acid insertion is in close proximity to the glutamic acid at position 2094 in the three dimensional structure of the protein (Supplemental Figure 2). The glutamic acid at position 2094 is the site of two previously reported, dominant-negative, heterozygous variants associated with GLSP (McEntagart et al., 2016).

Figure 3.

The c.5935-17G>A variant impacts splicing. The reference DNA and amino acid sequence is shown above. The patient’s DNA and predicted amino acid sequence with the c.5935-17G>A variant (red) is shown below. Fifteen nucleotides of intron 45 are retained resulting in a predicted in-frame insertion of five amino acids. The transcript used is NM_001168272.1.

4. Discussion

We report a de novo, heterozygous intronic variant in ITPR1 associated with GLSP in a patient with characteristic features of GLSP including ataxia, cerebellar hypoplasia and bilateral symmetric fixed enlarged pupils with persistent pupillary membranes (without scalloped edges which is often observed in GLSP). Variants associated with GLSP are typically biallelic truncating variants or heterozygous, often de novo, variants located near the transmembrane domain which are hypothesized to act in a dominant-negative manner by affecting the assembly of homotetramers (Gerber et al., 2016; McEntagart et al., 2016; Stendel et al., 2019). Heterozygous variants in ITPR1 have also been associated with SCA15 and SCA29, but these variants typically cluster near the 5’ end of the gene affecting the regulatory domain (McEntagart et al., 2016). Moreover, iris abnormalities are not usually reported in SCA15 or SCA29. In addition, Sanger sequencing of cDNA from the patient’s fibroblasts demonstrated the retention of 15 nucleotides from intron 45 within the coding region of ITPR1. This intronic retention is associated with an in-frame insertion of five amino acids near the C-terminal transmembrane domain, which is the typical site for GLSP variants (Gerber et al., 2016; McEntagart et al., 2016; Stendel et al., 2019) (Figure 3). Moreover, the location of the predicted five amino acid insertion between the glutamine at position 1978 and the asparagine at position 1979 is in closely proximal to the site of at least two previously described heterozygous, dominant-negative pathogenic variants in ITPR1 that have been associated with GLSP (Supplemental Figure 3) (McEntagart et al., 2016). We hypothesize that this five amino acid insertion in this key domain of the protein produces a dominant-negative effect consistent with other heterozygous GLSP variants.

An alternative hypothesis is that this individual’s GLSP phenotype is due to biallelic variants in ITPR1 and that he has a second, undetected variant in ITPR1. However, a review of ES and GS data revealed no second rare variant in ITPR1 and no copy number variants associated with this gene. A heterozygous, common variant in ITPR1 was detected (NM_001168272.1:c.1435G>A:p.Val479Ile). This variant has an allele frequency of 1.063% in the Ashkenazi Jewish population in gnomAD and was reported to be homozygous in six individuals in this database (Karczewski et al., 2020). Thus, it seems unlikely that this variant is pathogenic although we cannot completely exclude the possibility of pathogenicity specifically when in trans with the de novo variant detected in our patient.

In addition to the 15-nucleotide insertion, this de novo variant is also associated with reduced expression of ITPR1 when compared to parental samples (Figure 2). This reduced expression was observed when ITPR1 expression was evaluated in fibroblasts by qPCR. Sanger sequencing of the common variant showed that both alleles are represented (Supplemental Figure 1). One possible explanation for these findings is that the intronic ITPR1 variant is producing alternate splice products, some of which undergo nonsense mediated decay (NMD), resulting in reduced expression as these products would not likely be detectable using our methods.

To date, approximately 26 reported cases of genetically confirmed patients with GLSP have been reported (Stendel et al., 2019). All these patients were described to have iris abnormalities, ataxia, and delayed age of walking. However, this patient’s aniridia was atypical for GLSP as there were no scalloped edges of the pupils. Additionally, most of these cases were described with hypotonia and intellectual disability ranging from mild to severe. Our participant has gross motor delay and hypotonia but does not appear to have documented cognitive impairment. Likewise, two other patients with GLSP were also reported to have normal cognitive development, including the most recently reported case (Stendel et al., 2019). Our patient adds to the phenotypic spectrum of cognitive development in patients with GLSP. Additionally, most individuals with GLSP have cerebellar atrophy on brain MRI (Stendel et al., 2019). The patient presented here had mild superior vermian and cerebellar volume loss on brain MRI at age 26 months of age. He also had increased T2 hyperintensity in the bilateral centrum semiovale, a non-specific finding that has been reported in individuals with developmental delay and with GLSP It has been reported previously that patients with GLSP can have normal neuroimaging at a young age and develop cerebellar abnormalities progressively in the first 5 years of life (McEntagart et al., 2016). Therefore, it is possible that his cerebellar abnormalities may become more evident as he grows older. Lastly, while some individuals with GLSP are reported to have dysmorphic features, this patient’s facial features (Figure 1), including apparent hypertelorism, are not consistently found in patients with GLSP and may be unrelated to this underlying diagnosis (Carvalho et al., 2018; Stendel et al., 2019).

Overall, to our knowledge, this is the first report of a de novo, heterozygous intronic variant in ITPR1 resulting in GLSP. This variant is associated with retention of 15 nucleotides from intron 45 leading to a predicted five amino acid insertion near the transmembrane domain of the protein, which, we hypothesize, has a dominant-negative impact on the protein’s function. This case demonstrates the importance of GS together with RNA studies as tools for identifying the pathogenic variant(s) associated with undiagnosed disorders, in this case GLSP, when a prior work-up, including ES, has been unrevealing.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Sanger sequencing of ITPR1 cDNA reveals presence of both the reference allele and the non-synonymous variant inherited from the mother (NM_001168272.1:c.1435G>A:p.Val479Ile) indicating biallelic expression of ITPR1 in the fibroblasts from the patient. A screenshot from the UCSC genome browser shows the reference sequence with variant site marked with a red box at the top of the figure. Sanger sequencing of clones from the patient’s cDNA are shown below. The red box indicates the site of the variant.

Supplemental Figure 2. Sanger sequencing of ITPR1 cDNA from fibroblasts reveals a 15-nucleotide intronic retention (intron 45) in the patient’s sample. This intronic retention was detected in 3 of 5 fully sequenced clones from the patient. This intronic retention was not detected in a total of 12 cDNA clones from the parents’ fibroblasts.

Supplemental Figure 3. Three-dimensional modeling of ITPR1 (homotetramer) demonstrates the close proximity of the site of the predicted five amino acid insertion (indicated by star) neighboring the arginine at position 1979 (light green) and the site of the glutamic acid at position 2094 (light green) in one monomer. Heterozygous, de novo missense variants at position 2094 have been described previously in individuals with GLSP (McEntagart et al., 2016). The homotetramer structure is shown with each monomer as a different color. RCSB PDB (ID = 3JAV) was used to generate this image.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the NIH Common Fund, through the Office of Strategic Coordination/Office of the NIH Director under Award Numbers U01HG007709 and U01HG007942. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. L.C.B. holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. L.K. received support from the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) Newborn Screening Genetics Program as a clinical genetics summer scholar at Baylor College of Medicine. This project was supported in part by the Clinical Translational Core (CTC) of the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC). The BCM IDDRC is supported by P50 HD103555 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the National Institutes of Health. R.M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health T32 GM07526-43. A.V.L is supported by the Adeline Lutz - Steven S.T. Ching, M.D. Distinguished Professorship in Ophthalmology and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. The Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine receives revenue from clinical genetic testing conducted at Baylor Genetics.

Relevant disclosures: The Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine receives revenue from clinical genetic testing completed at Baylor Genetics.

Data Availability Statement.

The genome sequencing data have been deposited in dbGAP (phs001232.v2.p1), and the novel variant in ITPR1 described in this manuscript was deposited in Clinvar (SCV001432135.1). Moreover, details regarding the phenotype and genotype were deposited in Phenome Central (P0008561).

References

- Carvalho DR, Medeiros JEG, Ribeiro DSM, Martins B, & Sobreira NLM (2018). Additional features of Gillespie syndrome in two Brazilian siblings with a novel ITPR1 homozygous pathogenic variant. Eur J Med Genet, 61(3), 134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, T. G. (2013). The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet, 45(6), 580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentici ML, Barresi S, Nardella M, Bellacchio E, Alfieri P, Bruselles A, … Zanni G (2017). Identification of novel and hotspot mutations in the channel domain of ITPR1 in two patients with Gillespie syndrome. Gene, 628, 141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Beroud G, Claustres M, & Beroud C (2009). Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res, 37(9), e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudding TE, Friend K, Schofield PW, Lee S, Wilkinson IA, & Richards RI (2004). Autosomal dominant congenital non-progressive ataxia overlaps with the SCA15 locus. Neurology, 63(12), 2288–2292. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147299.80872.d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Baker ML, Wang Z, Baker MR, Sinyagovskiy PA, Chiu W, … Serysheva II. (2015). Gating machinery of InsP3R channels revealed by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature, 527(7578), 336–341. doi: 10.1038/nature15249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskett JK, White C, Cheung KH, & Mak DO (2007). Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev, 87(2), 593–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi T, Simon-Chazottes D, Fujino I, Yamada N, Hasegawa M, Miyawaki A, … Mikoshiba K (1993). Widespread expression of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 gene (Insp3r1) in the mouse central nervous system. Recept Channels, 1(1), 11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber S, Alzayady KJ, Burglen L, Bremond-Gignac D, Marchesin V, Roche O, … Fares Taie L (2016). Recessive and Dominant De Novo ITPR1 Mutations Cause Gillespie Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet, 98(5), 971–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie FD (1965). Aniridia, Cerebellar Ataxia, and Oligophrenia in Siblings. Arch Ophthalmol, 73, 338–341. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970030340008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HN, Williamson KA, & FitzPatrick DR (2019). The genetic architecture of aniridia and Gillespie syndrome. Hum Genet, 138(8-9), 881–898. doi: 10.1007/s00439-018-1934-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Shiga A, Nozaki H, Mitsui J, Takahashi Y, Ishiguro H, … Onodera O (2008). Total deletion and a missense mutation of ITPR1 in Japanese SCA15 families. Neurology, 71(8), 547–551. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311277.71046.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Chardon JW, Carter MT, Friend KL, Dudding TE, Schwartzentruber J, … Boycott KM (2012). Missense mutations in ITPR1 cause autosomal dominant congenital nonprogressive spinocerebellar ataxia. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 7, 67. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki A, Kawano Y, Miura S, Shibata H, Matsuse D, Li W, … Fukumaki Y (2008). Heterozygous deletion of ITPR1, but not SUMF1, in spinocerebellar ataxia type 16. J Med Genet, 45(1), 32–35. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.053942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaganathan K, Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S, McRae JF, Darbandi SF, Knowles D, Li YI, … Farh KK (2019). Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell, 176(3), 535–548 e524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alfoldi J, Wang Q, … MacArthur DG (2020). The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature, 581(7809), 434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEntagart M, Williamson KA, Rainger JK, Wheeler A, Seawright A, De Baere E, … FitzPatrick DR (2016). A Restricted Repertoire of De Novo Mutations in ITPR1 Cause Gillespie Syndrome with Evidence for Dominant-Negative Effect. Am J Hum Genet, 98(5), 981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock DR, Dai H, Burrage LC, Rosenfeld JA, Ketkar S, Muller MF, … Lee B (2020). Transcriptome-directed analysis for Mendelian disease diagnosis overcomes limitations of conventional genomic testing. J Clin Invest. doi: 10.1172/JCI141500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S, Maeda N, & Mikoshiba K (1991). Immunohistochemical localization of an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, P400, in neural tissue: studies in developing and adult mouse brain. J Neurosci, 11(7), 2075–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, … Committee, A. L. Q. A. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med, 17(5), 405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Ohba C, Iai M, Hirabayashi S, Osaka H, Hiraide T, … Matsumoto N (2015). Sporadic infantile-onset spinocerebellar ataxia caused by missense mutations of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor type 1 gene. J Neurol, 262(5), 1278–1284. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7705-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnal D, Rose AS, Kovca J, Burley SK, & Velankar S (2018). Mol*: Towards a common library and tools for web molecular graphics. MolVA '18: Proceedings of the Workshop on Molecular Graphics and Visual Analysis of Molecular Data, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stendel C, Wagner M, Rudolph G, & Klopstock T (2019). Gillespie's Syndrome with Minor Cerebellar Involvement and No Intellectual Disability Associated with a Novel ITPR1 Mutation: Report of a Case and Literature Review. Neuropediatrics, 50(6), 382–386. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey E, Gardner RJ, Knight MA, Kennerson ML, Tuck RR, Forrest SM, & Nicholson GA (2001). A new autosomal dominant pure cerebellar ataxia. Neurology, 57(10), 1913–1915. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik M, Helbig KL, Harmuth F, Deconinck T, Tanpaiboon P, Sun B, … Schule R (2018). De novo ITPR1 variants are a recurrent cause of early-onset ataxia, acting via loss of channel function. Eur J Hum Genet, 26(11), 1623–1634. doi: 10.1038/s41431-018-0206-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Leemput J, Chandran J, Knight MA, Holtzclaw LA, Scholz S, Cookson MR, … Singleton AB (2007). Deletion at ITPR1 underlies ataxia in mice and spinocerebellar ataxia 15 in humans. PLoS Genet, 3(6), e108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada N, Makino Y, Clark RA, Pearson DW, Mattei MG, Guenet JL, … et al. (1994). Human inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate type-1 receptor, InsP3R1: structure, function, regulation of expression and chromosomal localization. Biochem J, 302 ( Pt 3), 781–790. doi: 10.1042/bj3020781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule DI, Betzenhauser MJ, & Joseph SK (2010). Linking structure to function: Recent lessons from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mutagenesis. Cell Calcium, 47(6), 469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Sanger sequencing of ITPR1 cDNA reveals presence of both the reference allele and the non-synonymous variant inherited from the mother (NM_001168272.1:c.1435G>A:p.Val479Ile) indicating biallelic expression of ITPR1 in the fibroblasts from the patient. A screenshot from the UCSC genome browser shows the reference sequence with variant site marked with a red box at the top of the figure. Sanger sequencing of clones from the patient’s cDNA are shown below. The red box indicates the site of the variant.

Supplemental Figure 2. Sanger sequencing of ITPR1 cDNA from fibroblasts reveals a 15-nucleotide intronic retention (intron 45) in the patient’s sample. This intronic retention was detected in 3 of 5 fully sequenced clones from the patient. This intronic retention was not detected in a total of 12 cDNA clones from the parents’ fibroblasts.

Supplemental Figure 3. Three-dimensional modeling of ITPR1 (homotetramer) demonstrates the close proximity of the site of the predicted five amino acid insertion (indicated by star) neighboring the arginine at position 1979 (light green) and the site of the glutamic acid at position 2094 (light green) in one monomer. Heterozygous, de novo missense variants at position 2094 have been described previously in individuals with GLSP (McEntagart et al., 2016). The homotetramer structure is shown with each monomer as a different color. RCSB PDB (ID = 3JAV) was used to generate this image.

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequencing data have been deposited in dbGAP (phs001232.v2.p1), and the novel variant in ITPR1 described in this manuscript was deposited in Clinvar (SCV001432135.1). Moreover, details regarding the phenotype and genotype were deposited in Phenome Central (P0008561).