Abstract

Protective behavioral strategies (PBS) are useful skills for reducing the negative consequences of alcohol. The moderating effects of anxiety on the relationship between 3 different types of PBS and negative consequences were examined among students accessing college counseling services. Results revealed a significant interaction between anxiety and strategies while drinking, suggesting that these simple strategies may be particularly beneficial among students who drink heavily and experience high levels of anxiety. Implications for counseling centers are discussed.

Keywords: alcohol use, protective behavioral strategies, anxiety

Rates of heavy episodic drinking (HED) or binge drinking (i.e., four or more drinks in a row for women or five or more drinks in a row for men) in the United States have not declined in more than 15 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010), with 40% to 50% of college students reporting engaging in binge drinking (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). Students seeking counseling services warrant particular research attention, because a large proportion of college counseling center directors (46%) report increases in alcohol abuse problems among their student clients (Gallagher, 2010). Clearly, identifying mental health correlates of heavy drinking along with possible strategies that can be used to temper associated alcohol-related problems among this population would be of benefit to mental health professionals who are in a position to intervene with these students.

The association between alcohol use disorders and mental health challenges, such as anxiety, is well documented (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2005; Goldsmith, Thompson, Black, Tran, & Smith, 2012; Ham, Zamboanga, & Bacon, 2011). According to tension-reduction theory (Conger, 1956), experiences of anxiety can increase the likelihood of alcohol consumption, with tension reduction acting as a significant motivator for alcohol use. Consistent with this theory, the relationship between anxiety and hazardous drinking is mediated by tension-reduction expectancies and coping motives (Goldsmith, Tran, Smith, & Howe, 2009; Ham, Zamboanga, Bacon, & Garcia, 2009). Consuming alcohol as a means to cope with psychological distress or alleviate anxiety appears to be especially risky because it is associated with deficient internal coping mechanisms, poor psychosocial health, and a lack of volitional control over drinking (Carpenter & Hasin, 1999; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). Moreover, college students with an anxiety disorder are more than twice as likely as those without an anxiety disorder to meet the diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence or abuse (Kushner & Sher, 1993). Similarly, students with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are more likely to engage in HED than are those without GAD (Cranford, Eisenberg, & Serras, 2009). Even after controlling for the level of alcohol use, students with anxiety are at greater risk for experiencing the negative consequences of alcohol. For example, among female students, social anxiety is associated with greater personal (e.g., doing regrettable things, putting self in danger) and role consequences (e.g., neglecting household or family responsibilities; missing class, work, or some other important event [Norberg, Olivier, Alperstein, Zvolensky, & Norton, 2011]). For students who believe that alcohol has tension-reduction properties and report low perceived self-efficacy for refusing drinks, higher levels of generalized anxiety are associated with greater alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., feeling guilty about drinking, injury to self or others, neglected responsibilities; Goldsmith et al., 2012).

The association between alcohol use and anxiety is of particular concern considering the increasing prevalence of psychological problems among college students (Gallagher, 2010). A recent report indicated that one in 10 college students sought college counseling services, with 46.3% of students reporting having felt overwhelming anxiety and 9.2% reporting being diagnosed or treated for anxiety in the past 12 months (American College Health Association, 2011). Despite anxiety’s prevalence and its association with alcohol abuse, few studies have addressed strategies that may be particularly useful for reducing the negative consequences of alcohol in this population. The current study extends previous work in this area (LaBrie, Kenney, Lac, Garcia, & Ferraiolo, 2009; LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, 2011; Martens, Martin, Littlefield, Murphy, & Cimini, 2011; Patrick, Lee, & Larimer, 2011; Sugarman & Carey, 2009) by examining the use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS) in college students accessing college counseling services.

PBS

PBS, also referred to as drinking control behaviors (Sugarman & Carey, 2007), are alcohol-specific harm-reduction skills that students can use before, during, or after drinking to reduce the possible negative effects of alcohol use. For example, students can choose to avoid situations where heavy drinking is likely, alternate alcoholic and nonalcoholic drinks, or use a designated driver to reduce the risk of the negative consequences of alcohol. Students’ use of PBS is associated with lower alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol-related negative consequences (LaBrie et al., 2011; Martens et al., 2011; Patrick et al., 2011; Ray, Turrisi, Abar, & Peters, 2009). Furthermore, PBS moderate the relationship between HED and negative consequences in such a way that the association between drinking and negative consequences is weakened among individuals engaging in PBS more frequently (Borden et al., 2011). PBS are routinely and naturally endorsed by college students (Haines, Barker, & Rice, 2006). Perhaps because of these strategies’ intuitive appeal as a way to reduce risks associated with drinking, PBS skills training has become a fundamental feature of many multicomponent brief motivational interventions (BMIs; Larimer, Cronce, Lee, & Kilmer, 2004). Two studies of multicomponent interventions have found that postintervention use of PBS mediated intervention effectiveness (Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007; Larimer et al., 2007). Thus, some of the benefits of PBS are that students appear to use them naturally, students are amenable to PBS skills training within intervention settings, and students who spontaneously use PBS drink less and experience fewer consequences than do peers not using PBS (Benton et al., 2004; Haines et al., 2006; Martens et al., 2004, 2005; Park & Grant, 2005).

Recent data suggest that students with poorer mental health may be less likely to use PBS; however, these studies have focused on measures of overall PBS use (LaBrie, Kenney, & Lac, 2010; LaBrie et al., 2009; Martens et al., 2008). It is not clear whether there are specific types of PBS that are used less frequently in this population. This is an important distinction because students with poorer mental health may have the most to gain from the protective benefits of PBS. Martens et al. (2008) demonstrated that the use of PBS partially mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences, suggesting that students with high levels of depression are less likely to use PBS and more likely to experience a greater number of negative consequences. Furthermore, LaBrie et al. (2009) found that, among college women who reported poorer mental health, the use of PBS was associated with fewer total drinks, HED episodes, and alcohol-related negative consequences. PBS were less effective among students with higher mental health scores. Similarly, among a sample of heavy-drinking college men and women, for those with poorer mental health, the use of PBS was associated with the greatest decrease in alcohol-related negative consequences (LaBrie et al., 2010).

Although previous research has demonstrated the relationship between PBS and alcohol use and consequences, recent data suggest that not all PBS may be equally as effective at reducing alcohol use and, by extension, the negative consequences of alcohol. Sugarman and Carey (2007, 2009) found that selective avoidance and alternative strategies, which involve avoiding drinking or high-risk situations and choosing behaviors other than alcohol use to have fun or reduce negative affect, were associated with lower alcohol consumption; however, the use of strategies while drinking, such as spacing out drinks or eating while drinking, was positively related to alcohol consumption. Sugarman and Carey (2007, 2009) did not, however, examine the relationship between different types of strategies and alcohol-related negative consequences.

Findings by LaBrie and colleagues (2010) suggest that mental health symptoms moderate the relationship between PBS and alcohol-related negative consequences. The current study extends these findings by examining the use of PBS in a sample of students at high risk for alcohol problems (i.e., students who engage in HED and access mental health services), focusing specifically on the role of anxiety as a possible moderator and examining the relationship between three different types of PBS and alcohol-related negative consequences. We expected that PBS would be negatively associated with alcohol-related negative consequences and that individuals with higher levels of anxiety would benefit the most from using PBS as evidenced by lower reports of negative consequences.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 97) were students in a larger intervention study, which was designed to reduce alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences in heavy-drinking students who seek mental services at a campus counseling center. Data from a preintervention baseline survey were used in the current study. The majority of the sample was female (63.9%), and the mean age of the participants was 20.11 years (SD = 1.37). In accordance with National Institutes of Health standards, participants first indicated if they were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (yes or no) and then selected a racial category in a separate question. Approximately one fifth (18.6%) of the participants identified their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino. The reported racial composition of the sample was 70.1% White, 16.5% multiracial, 5.2% Asian, 5.2% other race, 1.0% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 1.0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 1.0% declined to state.

Procedure

Participants responded to recruitment flyers on display at a West Coast private university counseling center. Interested students were invited to telephone the research office and were screened for study eligibility over the phone. Inclusion criteria were as follows: heavy episode of drinking at least once in the past 2 weeks (four or more standard drinks for women, five or more standard drinks for men) and having seen a mental health provider within the past 2 years. After screening into the study, participants met with a research staff member and signed an informed consent form approved by a university institutional review board. Participants then completed a computerized survey. The assessment protocol was homogenous across intervention conditions, and, as an incentive, participants were paid $50 for attending the session. Participants were informed that their responses were confidential and would not be connected to their name or e-mail address. Before students answered questions related to drinking behavior, a standard drink was defined as a drink containing 0.5 ounces of ethyl alcohol (i.e., one 12-ounce beer, one 4-ounce glass of wine, or one 1.25-ounce shot of 80 proof liquor). Pictures of standard drinks accompanied these descriptions.

Measures

Alcohol consumption.

We used the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) to assess students’ alcohol consumption. Participants were asked to consider a typical week within the past 30 days and indicate the number of standard drinks typically consumed each day of the week. Responses were summed to form a measure of total drinks per week. The DDQ has been used in numerous studies of college student drinking and has demonstrated good convergent validity (e.g., r = .50; Collins et al., 1985) and test–retest reliability (e.g., r = .87; Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006).

Participants also completed the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). Example items are “How often during the past year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?” and “How often during the past year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking?” Items were summed to obtain an index of problem drinking (α = .77). In line with Allen, Litten, Fertig, and Babor’s (1997) examination of the specificity and sensitivity of AUDIT cutoff points, we used a cutoff of 8 to identify students who engaged in hazardous drinking.

Alcohol-related negative consequences.

The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (B-YAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) measures alcohol-related negative consequences experienced by college students in the past 30 days. The B-YAACQ contains 24 items that range in severity, and participants were asked to report whether they had experienced each consequence in the past 30 days. Example items are “I have had less energy or felt tired because of my drinking”; “I have neglected my obligations to family, work or school because of drinking”; and “I have felt like I needed a drink after I’d gotten up (that is, before breakfast).” Items were summed to create a composite score that represents the total number of problems participants experienced in the past 30 days, ranging from 0 to 24. The 30-day version of the B-YAACQ has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (.84 < α < .89) and stability (r = .70; Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008).

PBS.

Participants completed the 21-item Strategy Questionnaire (Sugarman & Carey, 2007), which assesses three categories of drinking control strategies: selective avoidance of heavy-drinking activities or situations (Selective Avoidance; seven items; α = .83), strategies used while drinking (Strategies While Drinking; 10 items; α = .73), and alternatives to drinking (Alternatives; four items; α = .75). Selective avoidance strategies involve avoiding high-risk alcohol behaviors (e.g., choosing not to pregame [i.e., drinking alcohol before attending a social event] or do shots). Strategies while drinking include ways to control the rate of alcohol consumption (e.g., spacing drinks over time, eating before or during drinking). Alternative strategies involve choosing approaches other than drinking alcohol to have fun, reduce stress, and be comfortable in social situations. Using a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always), participants indicated how often they had used each of the strategies in the past month. A mean composite for each subscale was created, with higher scores indicating that participants used PBS more frequently.

Anxiety.

We used the seven-item Anxiety subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales–21 (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) to measure students’ anxiety symptoms (α = .69). Participants responded to each item on a scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). The concurrent validity (.55 < r < .85) and internal consistency (.82 < α < .87) of the DASS-21 have been demonstrated in both nonclinical and clinical samples (Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns, & Swinson, 1998; Henry & Crawford, 2005).

Mental Health and Reasons for Accessing Counseling Services

Participants were asked to indicate the reason(s) for accessing mental health services. The majority of students (85.6%) reported more than one reason for accessing services. The most common responses were anxiety (68.0%), relationship or family problems (61.9%), and depression (47.4%). A number of students (19.6%) reported accessing services for substance use concerns. On the basis of participants’ DASS-21 scores, 39.5% of participants reported mild to severe levels of anxiety.

Results

Alcohol Use and Negative Consequences

Prior to statistical analyses, we examined participants’ reports of alcohol use for outliers (i.e., values more than three standard deviations above or below the mean). Following Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2007) recommendations, we recoded these values to one unit above (or below) the next most extreme value. Participants’ typical alcohol consumption ranged from 0 to 51 drinks per week, with students drinking an average of 17.3 (SD = 11.5, Mdn = 15.0) drinks per week and spending approximately 9.90 (SD = 6.20) hours per week consuming alcohol. On the basis of participants’ AUDIT scores, 82.5% of participants reported hazardous patterns of alcohol use in the past year.

On average, participants reported experiencing 8.90 (SD = 5.26) alcohol-related negative consequences in the past 30 days. Some of the most commonly reported negative consequences included hangovers (79.4%) and taking foolish risks (60.8%). Nearly one third of students reported that they had passed out from drinking (28.9%), found it difficult to limit their drinking (29.9%), or had gotten into sexual situations that they later regretted because of their drinking (32.0%).

Use of PBS

Responses to the Strategy Questionnaire were examined to identify the types of PBS that were most often used by the sample. Selective avoidance strategies (M = 2.00, SD = 0.99) were used less frequently than strategies while drinking (M = 2.90, SD = 0.83), t(96) = 11.05, p < .001, and alternative strategies (M = 2.80, SD = 1.07), t(96) = 7.42, p < .001. The most frequently reported strategies while drinking were eating before and during drinking (M = 3.80, SD = 1.13), paying attention to body sensations indicating intoxication (M = 3.80, SD = 1.31), and limiting drinking to certain days of the week (M = 3.80, SD = 1.29). The selective avoidance strategies that were used least often were choosing not to pregame or prebar (i.e., drinking alcohol before going to a bar, pub, or similar drinking establishment; M = 1.40, SD = 1.28) and choosing not to participate in drinking games (M = 1.60, SD = 1.52). On average, students reported using 17 of the 21 strategies at least once in the past month.

Relationship Between Alcohol Use, Negative Consequences, Mental Health, and PBS

We used Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients to examine bivariate relationships between drinking, negative consequences, anxiety, and PBS (see Table 1). The number of alcoholic drinks consumed in a typical week was found to be positively correlated with both anxiety (r = .22, p = .032) and alcohol-related negative consequences (r = .53, p < .001). Higher levels of drinking were associated with less frequent use of all three types of PBS (−.43 < rs < −.48). Alcohol-related negative consequences were positively correlated with anxiety (r = .33, p = .001). Negative consequences were negatively correlated with drinking strategies (−.34 < rs < −.41), indicating that more frequent use of PBS was bivariately associated with fewer negative consequences from drinking. Finally, higher levels of anxiety were associated with less frequent use of strategies while drinking (r = −.30, p = .003) and alternative strategies (r = −.21, p = .035).

Table 1.

Summary of Intercorrelations for Alcohol Use, Negative Consequences, Anxiety, and Protective Behavioral Strategies

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1. Number of drinks per week | — | |||||

| 2. Negative consequences | .53*** | — | ||||

| 3. Anxiety | .22* | .33** | — | |||

| 4. Strategies while drinking | −.43*** | −.41*** | −.30** | — | ||

| 5. Alternative strategies | −.46*** | −.34** | −.21* | .50*** | — | |

| 6. Selective avoidance strategies | −.48*** | −.40*** | −.08 | .58*** | .47*** | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We used a three-step hierarchical multiple regression model to examine the role of anxiety and PBS in predicting alcohol-related negative consequences (see Table 2). At Step 1, number of drinks per week was entered as a covariate to control for the level of alcohol consumption. Step 2 evaluated the main effects of anxiety and the three types of PBS (i.e., selective avoidance strategies, strategies while drinking, and alternative strategies). The interaction terms involving anxiety and each of the types of PBS were entered in Step 3. Predictors were mean centered prior to calculation of interaction terms. Mean centering involves subtracting the mean value from the raw scores and aids in the interpretation of interactions (see Aiken & West, 1991). A moderator effect is shown if the interaction between the moderator (anxiety) and the strategies is significant while the independent effects of each are statistically controlled (see Baron & Kenny, 1986).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences From Anxiety, Protective Behavioral Strategies, and Alcohol Use

| Step and Variable | Step 1 β | Step 2 β | Step 3 β | SE | R 2 | Model F | ΔR2 | ΔF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1 | .29 | 37.82*** | ||||||

| Number of drinks per week | .53*** | .37*** | .36*** | .05 | ||||

| Step 2 | .37 | 10.59*** | .08 | 2.99* | ||||

| Anxiety | .21* | .15 | .08 | |||||

| Strategies while drinking | −.09 | −.13 | .07 | |||||

| Selective avoidance strategies | −.15 | −.16 | .08 | |||||

| Alternative strategies | −.01 | .03 | .13 | |||||

| Step 3 | .42 | 8.02*** | .05 | 2.74* | ||||

| Anxiety × Strategies While Drinking | −.27* | .01 | ||||||

| Anxiety × Selective Avoidance Strategies | .15 | .02 | ||||||

| Anxiety × Alternative Strategies | .13 | .02 | ||||||

Note. Standard errors are reported for the final step of the regression.

p < .05.

p < .001.

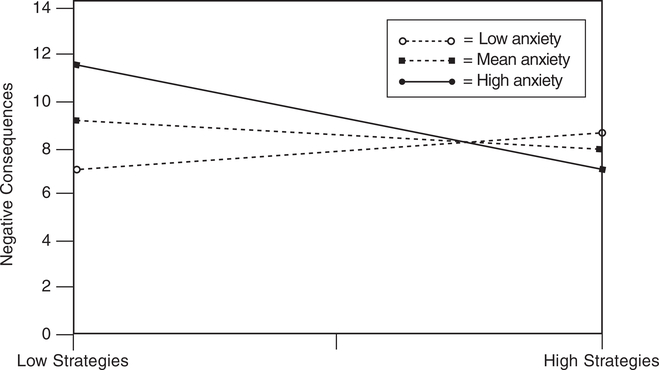

The following predictors uniquely contributed to the prediction of alcohol-related negative consequences: number of drinks per week (β = .53, p < .001), anxiety (β = .21, p = .024), and Anxiety × Strategies While Drinking (β = −.27, p = .014). Following Aiken and West’s (1991) recommendations, we graphed the Anxiety × Strategies While Drinking interaction at one standard deviation below the mean (low anxiety), at the mean, and at one standard deviation above the mean (high anxiety; Figure 1). Simple slope analyses were significant for high anxiety (β = −.42, p = .015) but not for low (β = .16, p = .288) or mean anxiety (β = −.13, p = .247). The significant moderation effect revealed that, among students with high anxiety, the increase in the use of strategies while drinking was associated with fewer alcohol-related negative consequences. Among individuals with low to mean anxiety, there was no relationship between the use of strategies while drinking and experiences of negative consequences.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of Strategies While Drinking on Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences Moderated by Anxiety, While Controlling for Alcohol Consumption

Discussion

The present study extends the work of Sugarman and Carey (2007) by examining the relationship between the three different types of PBS and alcohol-related negative consequences among a sample of a high-risk subpopulation of college students: heavier drinking students accessing college counseling services. Results of the bivariate analysis demonstrated that all three strategies were negatively associated with negative consequences, suggesting that they may potentially be useful for these types of students. Results of the multivariate analysis, however, indicated that anxiety predicted alcohol-related negative consequences over and above the use of PBS and that, for students experiencing high levels of anxiety, some strategies may be more beneficial than others. Among students who used fewer strategies while drinking, those with high anxiety experienced twice as many alcohol-related negative consequences than did those with low anxiety. Among those with high anxiety, using strategies while drinking reduced the number of alcohol-related negative consequences by half. These findings are consistent with previous research using global measures of mental health among general student populations to demonstrate that poorer mental health moderates the effect of PBS on alcohol use and negative consequences (LaBrie et al., 2009, 2010). Furthermore, our findings extend this previous work by demonstrating that this relationship may be true for some types of strategies but not for others.

This study provides useful insight into the types of PBS used by heavy-drinking college students accessing mental health services. Participants reported using the majority of the PBS they were asked about at least once in the past month, highlighting that these strategies appear intuitive to students with poorer mental health. Although the overall prevalence of PBS use was fairly high, the average frequency of use was relatively low, indicating that many students had the possibility of increasing how often they used PBS. For example, participants reported using strategies while drinking (e.g., eating before or during drinking, being aware of body sensations associated with intoxication) more frequently than other types of PBS, although they still typically used these strategies only sometimes to occasionally. Students used selective avoidance strategies less frequently than the other types of PBS. For students with mental health challenges, these strategies may be more difficult to implement because they involve negotiating social interactions with peers, such as refusing drinks or choosing not to participate in drinking games. Participants may lack the resources to cope effectively with these situations or may have a strong desire to fit in, which reduces their motivation to use these types of strategies. Alternatively, students with poorer mental health may be drinking more in less social settings or even by themselves where these strategies are not relevant. However, both selective avoidance and alternative strategies were not associated with reductions in negative consequences in the multivariate model and may not be the most effective strategies among this population. Alternative strategies are likely to involve planning and higher order cognitive functioning. For example, students experiencing psychological distress may find it difficult to use alternative strategies that involve identifying ways to reduce stress or coming up with their own coping strategies for situations where HED is likely to occur. Research addressing barriers that students with mental health challenges face when implementing different types of PBS may be beneficial for further developing alcohol interventions that target this population.

It is important to note that although Sugarman and Carey (2007) reported selective avoidance and alternative strategies to be negatively correlated with drinking, strategies while drinking were positively related to alcohol consumption among student drinkers. In the current study, however, all three types of PBS negatively correlated with alcohol consumption. This finding suggests that, in heavier drinking clinical samples, strategies while drinking, such as spacing drinks and drinking slowly, may be associated with lower levels of alcohol consumption. Therefore, it is likely that, among students who are highly anxious, the protective effects of using strategies while drinking to reduce alcohol problems are directly related to the ability of those strategies to also reduce risky levels of alcohol consumption.

This study also reveals that college students accessing counseling center services may be particularly at risk for high levels of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences compared with their peers. Although our study specifically targeted students who reported binge drinking, these findings are consistent with data suggesting that risky drinking behaviors, particularly HED, appear high among this population. A recently conducted intake of 545 students accessing a college counseling center revealed that most first-time clients (57%) reported HED in the past 2 weeks and that, among drinkers, 75% of men and 78% of women reported HED (LaBrie, 2009). These rates stand in contrast to the 40% to 50% rates of HED reported nationally among college students (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). The high levels of HED are particularly concerning because students experiencing psychological distress may lack the social support and psychological resources that could help prevent the experiencing of negative consequences from drinking. Although the rates of alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences in the current sample were high, less than one in five of the students reported visiting the counseling center for substance use concerns. Even though counseling center clients may not seek services for alcohol use, many students are likely drinking at risky levels and could benefit from screening and brief interventions targeting HED.

Implications for Counseling Practice

The current study has several clinical implications for college counseling staff concerned with alcohol consumption. The results suggest that anxiety was associated with increased alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences and that students who were highly anxious experienced lower levels of negative consequences when strategies while drinking were used more frequently. Students presenting with anxiety issues appear to be a high-risk group who may also benefit the most from PBS skills training to build self-efficacy; students can then use these strategies when they are in drinking situations. Strategies while drinking were the most frequently used strategies by participants in our study, and this familiarity may aid in enhancing their abilities to use them more frequently. Moreover, the fact that anxiety was negatively associated with these strategies suggests that there is the potential for students with anxiety to increase their use of these strategies.

One way in which counselors could incorporate discussions of the utility of PBS among clients who are highly anxious and drink heavily is by focusing on increasing their motivations for using PBS within the context of a BMI. Brief alcohol interventions targeting college students have proved to be well received, cost-effective, and recognized for their ability to reduce risks associated with alcohol use (for reviews, see Larimer & Cronce, 2002, 2007). These interventions are typically based on the styles and techniques of motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI is a nonjudgmental and nonconfrontational clinical approach that brings about behavioral change through the clinician expressing empathy, developing discrepancy with the client’s current behavior and goals, rolling with any resistance, and supporting the self-efficacy of the client to create change. MI has demonstrated effectiveness on a range of addictive behaviors, including alcohol abuse (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Many intervention studies have found lasting reductions in alcohol use after just one or two brief sessions (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2000; Dimeff et al., 1999; LaBrie, Pedersen, Lamb, & Bove, 2006; Seigers & Carey, 2010). Similar protocols could be adapted with the focus on PBS use, which, in the current sample, was negatively related to alcohol use.

In a review of brief interventions with college students, Larimer et al. (2004) asserted that screening for heavy alcohol use and subsequent interventions should be an added feature of normal intake procedures at campus health and counseling centers. Mental health professionals in counseling centers could include a simple screening battery as part of a client’s intake. Although there are numerous ways to design appropriate screening criteria, students could complete a brief assessment that might include as few as 14 items. For example, the battery could include the seven-item Anxiety subscale of the DASS-21, which was used in the current study; three open-ended questions assessing the quantity of alcohol consumed, frequency of alcohol consumption, and peak alcohol use in the past 30 days (Baer, 1993; Marlatt, Baer, & Larimer, 1995); and the four-item CUGE (acronym for cut down, under the influence, guilty, and eye-opener) questionnaire (Van Den Bruel, Aertgeerts, Hoppenbrouwers, Roelants, & Buntinx, 2004), which is a yes-or-no questionnaire that assesses high-risk drinking. Example items from the CUGE are “Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?” and “Have you ever been under the influence of alcohol in a situation where it increased your chances of getting hurt, for example, when riding a bicycle, driving a car, or operating a machine?” Criteria for delivery of a BMI could be high anxiety as measured by the DASS-21 and at least one “yes” response to any CUGE item or endorsement of high-risk quantities of consumed alcohol (i.e., if average quantity consumed or maximum drinks consumed meets the criteria for binge drinking on the basis of the student’s gender). A BMI would then be implemented that focuses on building motivation to use PBS effectively to reduce risks associated with high levels of alcohol use. For example, mental health professionals could use measures such as the Strategy Questionnaire to identify the types of PBS that students are already using, affirm the use of these strategies, examine students’ motivations to try new PBS, and discuss barriers to increasing the frequency of PBS use.

Brief screening and intervention have been shown to be more effective than care as usual (e.g., medical treatment for alcohol-induced injury, a handout on avoiding drinking and driving, a list of local treatment agencies) with young adults in emergency departments (Helmkamp et al., 2003; Monti et al., 1999). In addition, students screened in the waiting room at a health center who received a BMI showed treatment effects when compared with assessment-only controls (Dimeff, 1997). Although there are some ongoing studies of screening and brief interventions for drinking in student health centers, to our knowledge, there is no published research of similar interventions in counseling centers where personnel might be better equipped to intervene successfully with students who engage in problematic drinking. Future research is needed to examine the efficacy of interventions aimed at increasing the use of strategies while drinking among students with anxiety and whether BMIs incorporating PBS skills training could be effectively incorporated into counseling center settings.

Limitations and Conclusion

The current study is not without limitations. The small sample size did not permit further analysis to examine possible gender differences in the moderating effects of anxiety. Previous research has demonstrated that the link between GAD and HED may be stronger for men than for women (Cranford et al., 2009) and that PBS may be more effective for women than for men at reducing alcohol consumption (LaBrie et al., 2011). Because of this study’s cross-sectional design, we are not able to draw conclusions about whether using different types of PBS causes changes in alcohol use and negative consequences. Longitudinal research is needed to examine whether PBS use among individuals experiencing high levels of anxiety leads to fewer future alcohol-related negative consequences. Further research should also address the role of specific types of anxiety. We used a general measure of anxiety, rather than looking at PBS among students diagnosed with a specific anxiety disorder, such as social anxiety disorder. Research examining the effects of different types of anxiety may help to further identify high-risk groups for whom PBS-based interventions may be beneficial.

Nonetheless, the current study draws attention to the concerning levels of alcohol consumption among students accessing college counseling services, provides insight into the types of PBS used most frequently by this population, and helps to identify which strategies may be most beneficial for students experiencing high levels of anxiety. Our study also highlights the importance of examining the effects of different types of PBS, because it appears that some types of PBS may be more beneficial and practical to implement than others among students with mental health challenges. Although more research is necessary, it appears that counseling centers may effectively reduce risks associated with alcohol use in their clients, particularly those who are highly anxious, by teaching and building client efficacy for simpler risk-reduction strategies to use in drinking situations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R21AA020104-02 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Contributor Information

Lucy E. Napper, Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles. Department of Psychology, Lehigh University.

Joseph W. LaBrie, Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles.

Justin F. Hummer, Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles. Department of Psychology, University of Southern California.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, & Babor T (1997). A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 21, 613–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03811.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. (2011). American College Health Association–National College Health Assessment II: Reference group data report fall 2010. Retrieved from http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/ACHA-NCHA-II_ReferenceGroup_DataReport_Fall2010.pdf

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, & Swinson RP (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10, 176–181. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS (1993). Etiology and secondary prevention of alcohol problems with young adults. In Baer JS, Marlatt GA, & McMahon RJ (Eds.), Addictive behaviors across the lifespan (pp. 111–137). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, & Monti PM (2007). Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton SL, Schmidt JL, Newton FB, Shin K, Benton SA, & Newton DW (2004). College student protective strategies and drinking consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Martens MP, McBride MA, Sheline KT, Bloch KK, & Dude K (2011). The role of college students’ use of protective behavioral strategies in the relation between binge drinking and alcohol-related problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25, 346–351. doi: 10.1037/a0022678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, & Carey KB (2000). Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 728–733. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, & Hasin DS (1999). Drinking to cope with negative affect and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders: A test of three alternative explanations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60, 694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Vital signs: Binge drinking among high school students and adults—United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59, 1274–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ (1956). Alcoholism: Theory, problem and challenge: II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 17, 296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Eisenberg D, & Serras AM (2009). Substance use behaviors, mental health problems, and use of mental health services in a probability sample of college students. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, & Chou PS (2005). Psychopathology associated with drinking and alcohol use disorders in the college and general adult populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 77, 139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA (1997). Brief intervention for heavy and hazardous college drinkers in a student primary health care setting (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Washington, Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, & Marlatt GA (1999). Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher RP (2010). National survey of counseling center directors 2010 (Monograph Series No. 8S). Retrieved from American College Counseling Association website: http://www.collegecounseling.org/pdf/2010_survey.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith AA, Thompson RD, Black JJ, Tran GQ, & Smith JP (2012). Drinking refusal self-efficacy and tension-reduction alcohol expectancies moderating the relationship between generalized anxiety and drinking behaviors in young adult drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 59–67. doi: 10.1037/a0024766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith AA, Tran GQ, Smith JP, & Howe SR (2009). Alcohol expectancies and drinking motives in college drinkers: Mediating effects on the relationship between generalized anxiety and heavy drinking in negative-affect situations. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MP, Barker G, & Rice RM (2006). The personal protective behaviors of college student drinkers: Evidence of indigenous protective norms. Journal of American College Health, 55, 69–75. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.2.69-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, & Bacon AK (2011). Putting thoughts into context: Alcohol expectancies, social anxiety, and hazardous drinking. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 25, 47–60. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.25.1.47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Bacon AK, & Garcia TA (2009). Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38, 133–145. doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmkamp JC, Hungerford DW, Williams JM, Manley WG, Furbee PM, Horn KA, & Pollock DA (2003). Screening and brief intervention for alcohol problems among college students treated in a university hospital emergency department. Journal of American College Health, 52, 7–16. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, & Crawford JR (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, & Borsari B (2008). Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 611–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, & Read JP (2005). Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29, 1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000171940.95813.A5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, & Sher KJ (1993). Comorbidity of alcohol and anxiety disorders among college students: Effects of gender and family history of alcoholism. Addictive Behaviors, 18, 543–552. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90070-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW (2009). [Alcohol use among first-time clients at a college counseling center]. Unpublished raw data.

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, & Lac A (2010). The use of protective behavioral strategies is related to reduced risk in heavy drinking college students with poorer mental and physical health. Journal of Drug Education, 40, 361–378. doi: 10.2190/DE.40.4.c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Lac A, Garcia JA, & Ferraiolo P (2009). Mental and social health impacts the use of protective behavioral strategies in reducing risky drinking and alcohol consequences. Journal of College Student Development, 50, 35–49. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, & Mirza T (2011). Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER, Lamb TF, & Bove L (2006). Heads UP! A nested intervention with freshmen male college students and the broader campus community to promote responsible drinking. Journal of American College Health, 54, 301–304. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.5.301-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, & Cronce JM (2002). Identification, prevention, and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 14, 148–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, & Cronce JM (2007). Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM, Lee CM, & Kilmer JR (2004). Brief intervention in college settings. Alcohol Research & Health, 28, 94–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, … Neighbors C (2007). Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, & Lovibond PF (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Psychology Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, & Larimer ME (1995). Preventing alcohol abuse in college students: A harm-reduction approach. In Boyd GM, Howard J, & Zucker RA (Eds.), Alcohol problems among adolescents: Current directions in prevention research (pp. 147–172). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Korbett K, Anderson DA, & Simmons A (2005). Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Hatchett ES, Fowler RM, Fleming KM, Karakashian MA, & Cimini MD (2008). Protective behavioral strategies and the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 535–541. doi: 10.1037/a0013588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Littlefield AK, Murphy JG, & Cimini MD (2011). Changes in protective behavioral strategies and alcohol use among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118, 504–507. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Taylor KK, Damann KM, Page JC, Mowry ES, & Cimini MD (2004). Protective behavioral strategies when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Myers M, … Lewander, W. (1999). Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 989–994. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, & Neil TA (2006). Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 290–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg MM, Olivier J, Alperstein DM, Zvolensky MJ, & Norton AR (2011). Adverse consequences of student drinking: The role of sex, social anxiety, drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (2002). Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 14, 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, & Grant C (2005). Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Lee CM, & Larimer ME (2011). Drinking motives, protective behavioral strategies, and experienced consequences: Identifying students at risk. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 270–273. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AE, Turrisi R, Abar B, & Peters KE (2009). Social-cognitive correlates of protective drinking behaviors and alcohol-related consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption—II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigers DK, & Carey KB (2010). Screening and brief interventions for alcohol use in college health centers: A review. Journal of American College Health, 59, 151–158. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.502199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, & Carey KB (2007). The relationship between drinking control strategies and college student alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 338–345. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, & Carey KB (2009). Drink less or drink slower: The effects of instruction on alcohol consumption and drinking control strategy use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 577–585. doi: 10.1037/a0016580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bruel A, Aertgeerts B, Hoppenbrouwers K, Roelants M, & Buntinx F (2004). CUGE: A screening instrument for alcohol abuse and dependence in students. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 39, 439–444. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, & Nelson TF (2008). What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]