Abstract

In many languages, significant numbers of words are used in more than one grammatical category; English, in particular, has many words that can be used as both nouns and verbs. Such ambicategoricality potentially poses problems for children trying to learn the grammatical properties of words and has been used to argue against the logical possibility of learning grammatical categories from syntactic distribution alone. This article addresses how often English-learning children hear words used across categories, whether young language learners might be sensitive to perceptual cues that differentiate noun and verb uses of such words and how young speakers use ambicategorical words. The findings suggest that children hear considerably less cross-category usage than is possible and are sensitive to perceptual cues that distinguish the two categories. Furthermore, in early language production, children’s cross-category production mirrors the statistics of their linguistic environments, suggesting that they are distinguishing noun and verb uses of individual words in natural language exposure. Taken together, these results indicate that cues in the speech stream may help children resolve the ambicategoricality problem.

Language makes “infinite use of finite means” (von Humboldt, 1836/1999) by combining known words into novel sequences. Words are not restricted to linguistic contexts in which they have previously been used, nor may they be used freely in any context. Rather, the potential syntactic contexts in which words may occur are governed by their grammatical categories: noun, verb, adjective, or adverb. Membership in one of these categories defines how a word behaves syntactically. For example, nouns may be subjects of verbs but also objects of verbs, objects of prepositions, indirect objects, and so forth. Knowledge of category membership, in turn, allows speakers to use words productively in contexts that vary from those in which particular words have been heard. In this article, we examine words that can be used in more than one grammatical category. We begin by explaining why such words might pose a problem for learning grammatical categories. Then we consider the nature of these words in the linguistic experience of young children in terms of the frequency with which they are used across category boundaries. We next ask whether infants are sensitive to subtle perceptual properties that distinguish noun and verb uses of the same words. Finally, we examine the nature of these words in children’s productions and the influence of language experience on their usage. Taken together, these three studies improve our empirical understanding of grammatical category ambiguity in early language development.

A central task for language learners is to determine which words in the language belong to which categories. Unfortunately for learners, membership in a category not only defines how a word behaves syntactically but is also defined by the word’s syntactic behavior. Nouns are defined by how they may co-occur with verbs and adjectives; verbs are defined by how they may co-occur with adjectives and nouns; adjectives are defined by how they may co-occur with nouns and verbs, and so on. The circularity of this system poses a particular challenge to learners: What cues can be relied upon for learning category membership if one is learning about the syntax of the language at the same time? Known as the “bootstrapping problem,” this question is central to much of the literature on syntactic acquisition (e.g., Gleitman & Wanner, 1982; Naigles, 1990; Pinker, 1984).

One solution to this problem is that learners may use local co-occurrence cues to learn the categories of words, a process sometimes referred to as distributional bootstrapping (e.g., Höhle, Weissenborn, Kiefer, Schulz, & Schmitz, 2004; Maratsos & Chalkley, 1980; Monaghan, Chater, & Christiansen, 2005). Models of grammatical category learning based on distributional cues in corpora of child-directed speech are reasonably accurate at categorizing words into noun and verb classes (Mintz, 2003; Mintz, Newport, & Bever, 2002; Redington, Chater, & Finch, 1998). However, these models define accuracy as the homogeneity of the output groups in terms of grammatical category. The question of how to account for lexical items that are ambiguous with regard to grammatical category is not considered in these models (but see Cartwright & Brent, 1997, for an interesting exception).

In principle, grammatical category ambiguity could wreak havoc with distributional learning: For such learning to be effective, it must be possible to keep separate those contexts in which nouns and verbs occur. In the optimal case, one set of words will appear in one set of contexts and another, mutually exclusive set of words will appear in a distinct set of contexts. This situation is depicted on the left side of Figure 1. In this case, it is quite simple to separate words into categories, as shown by the dotted line. If, however, a language has words that can appear in more than one grammatical category — and many languages do — keeping these contexts separate becomes more difficult, as depicted on the right side of Figure 1. In this case, it is not clear which words are in which category or, indeed, how many categories there might be.

FIGURE 1.

The diagram on the left represents an idealized situation for category learning, in which sets of words are used in mutually exclusive contexts. The diagram on the right represents a more realistic lexical categorization situation, in which cross-category usage renders the category learning problem much more complicated.

Pinker (1987) gives an example of the sort of problem that could arise for distributional bootstrapping from such ambicategorical words: Children using this learning strategy should take the evidence in (1a–c) and conclude that (1d) is grammatical in English (Pinker, 1987).

-

1

- I like fish.

- I like rabbits.

- John can fish.

- *John can rabbits.

On the basis of distributional evidence alone, learners cannot rule out (1d); by allowing noun and verb contexts to become conflated, ambicategorical words could cause learners to wildly overgeneralize the contexts in which any word might occur. Although one could argue that distributional category learning would capture this ambiguity by indicating that one word is allowed to appear, for example, both after “the” and after “is,” the point of learning grammatical categories is to move beyond specific contexts and predict whether a word will appear in an unattested context on the basis of how other members of its category behave. Children show this kind of linguistic creativity (Akhtar, 1999; Bowerman, 1982; Conwell & Demuth, 2007), suggesting that they represent the syntactic properties of words at a level more general than a specific set of contexts.

Grammatical category ambiguity sometimes arises from derivational processes that do not involve overt morphology, but other times it is the result of historical derivation or pure accident. For example, as Clark and Clark (1979) pointed out, some words are typically nouns but can be used as verbs, as in (2), and vice versa, as in (3). In these situations, ambicategoricality accompanies a semantic relationship. In other cases, homophones may belong to different categories, as in (4) or (5), with no systematic semantic relationship between the forms.

-

2

- The water on the beach stretched to the horizon.

- John should water the flowers in the morning.

-

3

- I will walk to the park tonight.

- Mary takes a walk every day.

-

4

- That dress doesn’t fit you.

- The toddler threw a fit.

-

5

Bears bear bare bears.

Pinker (1987, 1989) used examples such as (1) to argue that children could not possibly rely on syntactic distribution to learn about category membership. Distributional theories of category learning would predict errors such as that in (1d), but this kind of error is almost never attested in children’s speech. Pinker argued, therefore, that children are using something beyond syntactic distribution to learn grammatical categories. Pinker’s own theory of category learning, however, semantic bootstrapping (Pinker, 1984), does not resolve the problem either because it relies on lexical semantics for categorization, and many ambicategorical words refer to the same event or object regardless of their grammatical category, as in (3). It is not clear how lexical semantics would aid learners in such cases.

Ambicategoricality may seem, at first blush, to be a rather limited problem. Certainly, in languages with richer morphology than English, derivational and inflectional affixes may often unambiguously indicate whether phonotactically constant stems are being used as nouns or verbs. However, languages may include homophonous affixes (e.g., English –s serves as either a verbal or a nominal inflection), and not all languages are morphologically rich. Even if English were the only language to exhibit ambicategoricality – it is not1 – whatever capacities learners use to solve this problem must be available to all learners of all languages. The problem of ambicategoricality, therefore, remains a central quandary for most theories of category learning. Despite this, relatively little research has focused on explicating the facts of ambicategoricality, either in language input, or in children’s own productions.

Macnamara (1982) described attempts to teach his son, Kieran, the same word as both a noun and a verb. He reported that, at 17 months of age, Kieran was able to learn the same word to refer to both an object and an action but that he began to introduce phonological distinctions between the noun and verb forms. For example, within two weeks of being taught the nonsense word “bel” to refer to both an action and an unrelated object, Kieran used “bam” to refer to the action and “ban” to refer to the object. In a longitudinal study, Macnamara examined the use of words as both noun and verb in the speech in the Sarah corpus (Brown, 1973). He found that adults did not seem to avoid cross-category use when talking to Sarah but that Sarah failed to use the same word as both a noun and a verb until the age of 30 months. Once she began using the same word in both categories, she primarily used object words to refer to actions characteristically performed with those objects. This study was limited to a single child and it is, therefore, difficult to assess how general the results are.

Nelson (1995) further explored the issue of cross-category usage in speech to children by examining six word types (call, drink, help, hug, kiss, and walk) in 12 corpora of mother/child interactions. These corpora consisted of five recordings per dyad. Each use of the target words was categorized as either noun or verb, and proportional use in each category was calculated. Nelson found that parents do use these words as both noun and verb, but as her analysis focused on only six word types in relatively brief corpora, it is not possible to discern from these results how extensive ambicategoricality might be in children’s linguistic experience. In other words, these six word types might be the only ones that parents use as both noun and verb. If parents use the preponderance of word types only in a single category when speaking to their children, then children might not encounter category ambiguity until their knowledge of language is robust enough to incorporate it.

Barner and colleagues (Barner, 2001; Oshima-Takane, Barner, Elsabbagh, & Guerriero, 2001) examined all denominal verbs and deverbal nouns in nine corpora of mother/child speech. Their analyses focused mainly on the ways in which lexical semantics (e.g., action-denoting vs. object-denoting) affected use of words as both noun and verb. Adults and children in these corpora use some words as both noun and verb but to a lesser extent than they could. Object-denoting words were more likely to be used flexibly as both noun and verb than were abstract words. However, this analysis examined only data from Brown’s (1973) Stage 1. It is possible that the rate of cross-category word use by both caregivers and children might increase with grammatical ability. Furthermore, restricting the analysis to denominal verbs and deverbal nouns neglects the potential contributions of words that are accidental homonyms (e.g., fit, leaves) to the ambicategoricality problem.

In this article, we adopt a multipronged approach to this problem. We begin by examining the incidence of ambicategoricality in early English language input. We tabulate usages of several hundred word types from six longitudinal corpora of caregiver speech to children, providing a more complete picture of the nature of ambicategoricality in early linguistic experience. Unlike previous corpus studies, our analyses consider words for which the cross-category usages are semantically unrelated, as well as those that have a systematic semantic relationship. The longitudinal nature of these corpora also goes beyond that in previous work. Our results show that, although the problem is not as great as it might be, children are exposed to a nontrivial amount of cross-category word use.

The finding that children are indeed exposed to cross-category word usage raises the question of how learners might incorporate ambicategorical words into their developing lexical categories. We next ask whether early language learners are sensitive to perceptual cues to grammatical category that may be present in ambicategorical words. Monaghan, Christiansen, and Charter (2007) suggest that phonotactic cues to noun and verbhood may aid categorization. At first glance, this kind of information might seem irrelevant to the problem of ambicategoricality. After all, the noun and verb forms of a word appear homophonous. However, previous work (Sorenson, Cooper, & Paccia, 1978) indicates that noun tokens of words are reliably longer than verb tokens of the same words in adult-directed speech. Gahl (2008) also argues that apparent homophones, even those that are not ambicategorical, differ in duration as a function of the frequency of each meaning. Given the exaggerated prosody of infant-directed speech (Ferguson, 1964; Fernald et al., 1989; Fisher & Tokura, 1996), these cues should also be available in speech to infants (Kelly, 1992). Recent research further indicates that noun tokens and verb tokens of the same word are, in fact, prosodically differentiated in child-directed Canadian French (Shi & Moisan, 2008) and American English (Conwell & Morgan, 2008; Conwell, 2008). Our habituation study indicates that 13-month-olds are able to categorize noun and verb uses of the same words based on differences in pronunciation alone. We propose that this sensitivity may allow children to separate noun and verb uses of the same word for the purposes of category learning. If learners use this sensitivity to tackle the ambicategoricality problem in a natural language learning environment, words that appear in more than one lexical category should not pose a problem for children.

To assess whether ambicategoricality is actually problematic for young learners, we return to corpus analysis and ask whether children use words across categories in their early combinatorial speech. Previous research on early word learning suggests that they should not. Children are known to prefer to use a single word form for only one linguistic purpose and to avoid homonymy (Casenhiser, 2005; Macnamara, 1982; Nelson, 1995; Slobin, 1973). Children are also highly adept at regularizing variable input, even imposing structure where there is none (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1984; Goldin-Meadow, Butcher, Mylander, & Dodge, 1994; Hudson Kam & Newport, 2005). Such work predicts that children should avoid using words across categories and use words only in their prevalent category. However, if children use information available in the speech stream to distinguish noun and verb uses of the same word, they may learn two distinct, semi-homophonous forms rather than a single word that is ambicategorical. If this is the case, they should use words across categories. Because the statistics of the language children hear is often reflected in their own productions (Demuth, Machobane, & Maloi, 2003; Lieven, Pine, & Baldwin, 1997), children’s cross-category word use should mirror that of their caregivers. Our results show that young speakers not only use words as both nouns and verbs but also that their cross-category usage of particular words is strongly predicted by their caregiver’s usage, a pattern that we would not expect unless children were able to discriminate noun and verb uses of the same word. The results of all three studies, taken together, suggest that the richness of the speech signal helps young English-learning children to resolve the ambicategoricality problem. These findings have significant implications for the question of how children learn about grammatical categories and provide insight into the kinds of information that are incorporated into lexical representations.

STUDY 1

To determine the scope of the ambicategoricality problem for language learners, we examined six longitudinal corpora of child-directed speech. If caregivers regularly use words only in a single category when speaking to young children, the problem of category ambiguity in early acquisition would be rendered moot. If, however, caregivers use some word types as both noun and verb, the problem remains, and we must find a means by which language learners might resolve it. Previous work indicates that mothers do use some words as both noun and verb when talking to their children (Barner, 2001; Nelson, 1995; Oshima-Takane et al., 2001), but that work is of limited scope, examining either only a few word types or a small age range. Examination of more longitudinal corpora will enhance our understanding of cross-category usage in speech to children and allow us to determine the extent to which ambicategoricality is a problem for learners.

Method

Corpora

Six longitudinal corpora of maternal speech were examined. Five of these corpora came from the Providence Corpus (Demuth, Culbertson, & Alter, 2006). The sixth was the Nina corpus (Suppes, 1974) from the CHILDES database (MacWhinney, 2000), which was included to provide evidence that our results generalize beyond the dialect of English spoken in Providence, Rhode Island. The ages and number of recordings for each corpus are presented in Table 1. Children in the Providence Corpus were recorded every other week for two to three years, beginning as soon as they uttered their first words. The Lily corpus is an exception, as a sudden, rapid increase in her language production created a need for weekly recordings approximately a year after recording commenced. For completeness, all of the Lily files are included in this analysis. Nina was recorded approximately weekly. In all of these corpora, the child’s mother is the primary caregiver and interlocutor. This age range (approximately 1–3 years) is of particular interest because it provides a comprehensive view of the child’s productive language development from the very first utterances to complete, well-formed sentences. It also captures any changes in parental speech that may accompany the child’s shift from language receiver to active conversationalist.

TABLE 1.

Descriptions of Corpora Used for This Study

| Child | Sex | Age Range (years; months) | No. of Files |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | M | 1; 5−3; 5 | 52 |

| Ethan | M | 0; 11−2; 11 | 50 |

| Lily | F | 1; 1−4; 0 | 80 |

| Nina | F | 1; 11−3; 3 | 52 |

| Violet | F | 1; 2−3; 11 | 52 |

| William | M | 1; 4−3; 4 | 44 |

Procedure

For each corpus, the number of maternal uses of each word type was counted, with morphologically complex words treated as individual types (e.g., run, runs, and running were each counted separately). Because each corpus contained more than 3,000 word types, it was impractical to examine every single one for cross-category use. Therefore, three frequency ranges were chosen as “core samples” for analysis. High frequency words were those used more than 150 times by the mother, middle frequency words were those used 40–60 times by the mother, and low frequency words were those used 3–10 times by the mother. We used frequency as our sampling criteria to get as broad a picture of ambicategoricality as practically possible. Furthermore, frequency has been shown to affect the reliability of distributional and phonotactic cues to lexical category (Monaghan, et al., 2007) as well as the prosodic properties of words (Gahl, 2008; Zipf, 1965). Within each frequency range, every word type was placed in one of two categories: “noun or verb” and “neither noun nor verb.” Then, all those words that were nouns or verbs were further categorized as potentially ambicategorical or not. Whether or not a word was potentially ambicategorical was based on an analysis of the Brown Corpus (Francis & Kucera, 1983). Words that were used at least once as a noun and at least once as a verb in the Brown Corpus were considered potentially ambiguous.2 For every word type that was potentially ambicategorical, each utterance including one or more tokens of that type was extracted from the corpus, and each token was classified by hand as a noun, a verb, or “other.” Single word utterances, proper nouns and metalinguistic uses were classified as “other.” A token was considered a noun if it was modified by an adjective, appeared as the head of a noun phrase, was an argument of a verb, or could be replaced with a pronoun. A token was counted as a verb if it was modified by an adverb, took noun phrase or prepositional phrase arguments, or could be replaced with a pro-verb (e.g., do). The breakdown of number of types analyzed in each corpus is shown in Table 2. Classification was done by trained coders. For consistency, 5% of all word types were reclassified by a second coder. Reliability between coders was very high (Cohen’s K=.93).

TABLE 2.

Number of types analyzed for each frequency range in each maternal corpus

| No. Noun or Verb Types | No. Potentially Ambicategorical | No. Used Across Categories | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Middle | Low | Total | High | Middle | Low | Total | High | Middle | Low | Total | |

| Alex | 63 | 81 | 780 | 924 | 27 | 36 | 208 | 271 | 9 | 10 | 45 | 64 |

| Ethan | 72 | 101 | 938 | 111 | 28 | 39 | 210 | 277 | 10 | 14 | 40 | 64 |

| Lily | 185 | 179 | 1652 | 2016 | 39 | 46 | 291 | 376 | 17 | 26 | 76 | 119 |

| Nina | 75 | 103 | 677 | 855 | 30 | 45 | 175 | 250 | 6 | 13 | 28 | 47 |

| Violet | 47 | 77 | 1042 | 1166 | 18 | 35 | 266 | 319 | 4 | 13 | 69 | 86 |

| William | 45 | 73 | 717 | 835 | 21 | 32 | 193 | 246 | 8 | 10 | 46 | 64 |

High frequency words are those with >150 tokens, middle frequency words are those with 40–60 tokens and low frequency words are those with 3–10 tokens in the given corpus. The total is the sum of these three ranges.

The total proportion of potentially ambicategorical words that were actually used across category was calculated for each mother as the number of words used at least once as both noun and verb divided by the total number of potentially ambiguous words analyzed. To obtain a better idea of how ambicategoricality relates to frequency of use, for each frequency range for each mother, the same kind of calculation was done on only those word types within a given frequency range. These numbers provide an estimate of how many of the word types that each child heard were used across category boundaries at least once.

Results

Mothers used approximately a quarter of the potentially ambicategorical words across category boundaries. The proportions of ambicategorical use for all types used by a given mother ranged from .19–.32. This overall rate of cross-category usage is comparable to that found by Barner (2001), who finds proportions of ambicategorical use to be .17–.35, depending on the semantics of the word type. Figure 2 shows the results broken over frequency ranges. Because the particular word types within each frequency range are different for each mother, these data cannot be directly compared. In the speech of three of the mothers, words in the middle frequency range were the most likely to be used across category. The other three mothers used words in the high frequency range across category more than words in the other frequency ranges.

FIGURE 2.

For each mother, the proportion of potentially ambicategorical words that are actually used across categories is reported for each of three frequency ranges.

Those words that were used as nouns and verbs were only rarely used equally as both. Many words were only used once or twice in their minority category. Figure 3 shows the proportion noun use of high and middle frequency words. Words used as nouns 100% of the time were unambiguously nouns, while those used as nouns 0% of the time were unambiguously verbs. As noted, such words constituted the majority of potentially ambiguous words in child-directed speech. When it comes to those words that are actually used in both categories, patterns of use across mothers are somewhat consistent. All mothers use very few words equally in both categories. This shows that young children do not hear many words that are perfectly ambiguous between noun and verb. Rather, words tend to appear in a single category the majority of the time with a few uses in the alternate category. For all mothers, verbs are more likely to be occasionally used across category than nouns. This may be due to the high frequency of “light verb” constructions in speech to children (Barner, 2001; Theakston, Lieven, Pine, & Rowland, 2004).

FIGURE 3.

Each point represents a word type, with proportion noun use of that word type given on the y-axis.

We also considered the distribution in time of cross-category usages. It is possible that usages in the nonpredominant category might occur in a handful of clusters, as would happen if, for example, the game of Go were introduced during a particular recording session. To explore this possibility, we examined the high and middle frequency words in the speech of Nina’s mother. For words that had more than one usage in the nonpredominant category, two transitional probabilities were calculated: the likelihood that the previous token of that word was also from the nonpredominant category and the likelihood that the next token was in the nonpredominant category. Because considerable time elapsed between recordings, these calculations were all made within a recording and averaged over the corpus. First and last tokens in a recording had only one value (category of the following token and category of the preceding token, respectively), while all other tokens had two values. Of the 19 high and middle frequency words that Nina’s mother used as both noun and verb, 18 were used more than once in the nonpredominant category. For seven of these words, the tokens in the nonpredominant category generally appeared in clusters set apart from tokens of the predominant category. That is, the tokens following and/or preceding a minority use were more likely than chance (p>.66) to also be from the nonpredominant category. Three of these words showed no such clustering at all; tokens of the nonpredominant category never appeared adjacent to other tokens of that category. The minority tokens of the remaining eight word types were equally likely to follow or precede tokens from either category (.33<p<.66). These mixed results suggest that tokens from the nonpredominant category do not reliably appear in clusters, nor are they evenly interspersed with tokens from the predominant category. Because these data are from a single speaker, they do not necessarily characterize the experiences of all children. However, the mixed nature of the results suggests that, at least for some learners, temporal clustering is not a reliable cue to the lexical category of ambicategorical words.

These findings indicate that cross-category word use is not as prevalent in speech to young children as it might be, given that roughly one quarter to one third of the nouns and verbs they hear can be used across category. Neither, however, is it so rare as to be clearly irrelevant to the problem of language learning. Because mothers do use some words as both noun and verb when speaking to their children, learners must have some means of coping with this source of noise in the data if they are to use distributional cues for learning grammatical categories. If learners are unable to segregate noun and verb uses of the same words, it is not clear how they would form noun and verb categories, given that many of the words they hear appear in both categories (cf., Pinker, 1987).

A variety of cues may indicate the category of a particular word token. Syntactic information is not likely to be useful, as this is what children are trying to learn in the first place. Meaning has been proposed as a way to solve this problem, but meaning may not be useful for distinguishing between noun and verb uses of words such as kiss or smile, which have the same referent regardless of the grammatical category in which they are used. In a morphologically rich language, morphemes may provide evidence regarding the category of a word; unfortunately for English-learning children, their language not only has a somewhat impoverished morphological system, but many of the morphemes themselves are ambiguous with regard to grammatical category (e.g., -s may indicate a plural noun or a third person singular present tense verb). Previous research has demonstrated, however, that noun and verb uses of the same words are prosodically distinct (Sorenson et al., 1978; Shi & Moisan, 2008; Conwell & Morgan, 2008). Perhaps young language learners can use these prosodic or other perceptual cues to differentiate noun and verb uses of the same word. If they do so, they might learn two homophonous forms, one that is a noun and one that is a verb, rather than one word that is used across category. To assess this possibility, we now ask whether infants are able to differentiate noun and verb uses of the same word based only on their prosodic properties.

STUDY 2

We have demonstrated that young language learners hear some word types used as both noun and verb. Now we turn to the question of how children avoid conflating noun and verb categories given this fact about their linguistic experience. If they can differentiate noun and verb tokens of the same word based on their acoustic properties, they might learn two distinct, homophonous forms instead of one.

This idea is supported by work indicating that nouns, on the whole, are longer and have greater pitch change than verbs, even in cases of homophony (Sorenson et al., 1978; Shi & Moisan, 2008; Conwell & Morgan, 2008). In adult-directed speech, this difference is largely a function of the fact that nouns appear at the ends of clauses and phrases more often than verbs do (Sorenson et al.). However, in child-directed speech, these prosodic cues are independent of sentential position (Shi & Moisan). In an analysis of homophonous noun and verb durations in different sentential positions, Conwell (2008) found that sentence-final nouns and verbs did not differ in duration whereas sentence-medial nouns were reliably longer than sentence-medial verbs. The somewhat exaggerated prosodic properties of child-directed speech (Ferguson, 1964; Fernald et al., 1989; Fisher & Tokura, 1996) may make these cues particularly apparent in the language that infants hear (Kelly, 1992).

We use an infant-controlled habituation paradigm to assess infants’ ability to categorize noun and verb tokens of the same words based on perceptual information alone. If infants are sensitive to these differences, they might be able to use this information to differentiate noun and verb uses of the same word, thereby avoiding the problem of ambicategoricality, or at least postponing it until later in acquisition.

In this study, we use minimally edited tokens excised from spontaneous child-directed speech. Naturalistic stimuli allow us to assess infants’ ability to discriminate between noun and verb tokens that are representative of natural experience. These stimuli are as close as possible to exemplars that children are likely to hear in their everyday language exposure. Aside from the excision of the tokens and the normalization of amplitude, we did not manipulate these tokens in any way.

One problem with using such naturalistic stimuli, however, is that the variability of the tokens (both within and between categories) is difficult to control. Previous work examining infants’ ability to form naturally occurring categories has found that differences in within-category variability produce asymmetric behavior in habituation tasks (Quinn, Eimas, & Rosenkrantz, 1993; see also Furrer & Younger, 2006; Mareschal, French, & Quinn, 2000). When habituated to a category with low variability, infants form a narrow category and dishabituate to exemplars from a different but similar category. However, when habituated to a category with high variability, infants form a broad category and fail to recover looking time to exemplars from a different but similar category. Because controlling for variability was not possible with our naturalistic stimuli, we instead conducted a series of acoustic analyses on the stimuli to characterize any differences between the two categories.

Depending on the nature and extent of variability in our stimuli, different predictions might follow:

Prediction A: If infants use perceptual cues to categorize noun and verb tokens of the same words and if the within-category variation in our stimuli is not of the type or degree to affect their categorization, infants should continue to show decreased looking to novel exemplars of the category to which they were habituated, but recover looking to exemplars from the other category. These results should obtain regardless of habituated category.

Prediction B: If infants can distinguish noun and verb tokens but the differences in variation in our stimulus sets are sufficient to affect their categorization, we would expect asymmetric recovery from habituation.

Prediction C: Alternatively, the variability in the natural tokens might be so great that infants are not able to form coherent categories of noun and verb based on perceptual information alone. If that is the case, we would predict no recovery from habituation in any group of infants.

Method

Participants

A total of 36 13-month-old infants from the Providence, Rhode Island, area participated (12 male and 24 female). The mean age was 393 days (range 358–432 days). Previous work has shown that infants at this age are able to categorize words based on distribution (Gómez & Gerken, 1999; Mintz, 2006). If they distinguish between noun and verb uses of the same word at this age, they may be able to use such information in real-world lexical categorization. An additional 23 infants participated in the study but were excluded due to excessive fussiness or squirminess (9), failure to meet minimum looking time requirements on both test trials (8), failure to habituate (1), or a looking time on either test trial that was more than two standard deviations from the group mean (5).

Stimuli

The stimuli for this study were naturalistic noun and verb tokens of seven ambicategorical word types (dance, drink, help, kiss, rest, slide, and swing). These tokens were extracted from the spontaneous child-directed speech of the Lily corpus and were all produced by Lily’s mother. Tokens were extracted on the basis of having little extraneous noise and low co-articulation with surrounding words; tokens of both categories were selected from all sentential positions and from both declarative and interrogative sentences. The audio track for each token was extracted from the video using SoundConverter and edited using PRAAT (Boersma & Weenink, 2008). Amplitude was normalized across tokens.

To characterize the prosodic features of the stimuli, token duration, vowel duration, mean pitch, minimum pitch, maximum pitch and pitch change (in semitones) were measured using PRAAT. To provide a metric of vowel quality, we measured the first and second formant frequencies at the midpoint of the vowel. All measurements were taken for all 28 noun tokens and 28 verb tokens used in this study. The mean and variance for each measure are reported by category in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Prosodic and vowel quality measurements of habituation stimuli

| Nouns | Verbs | t-stat (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Token duration (ms) | 468.5 (192.9) | 366.2 (191.7) | 1.99 (0.05) |

| Vowel duration (ms) | 141.3 (99.0) | 110.2 (86.6) | 1.25 (0.22) |

| Mean pitch (Hz) | 93.3 (6.4) | 96.6 (5.4) | 1.74 (0.088) |

| Minimum pitch (Hz) | 86.5 (8.2) | 90.9 (6.2) | 1.90 (0.063) |

| Maximum pitch (Hz) | 100.2 (7.8) | 100.4 (6.4) | 0.13 (0.90) |

| Pitch change (ST) | 13.7 (9.9) | 9.5 (7.5) | 1.75 (0.086) |

| First formant frequency of vowel (Hz) | 739.6 (143.0) | 687.4 (178.9) | 2.17 (0.038) |

| Second formant frequency of vowel (Hz) | 1839.9 (425.0) | 1833.1 (501.0) | 0.07 (0.946) |

Each value is the mean measurement for that category, with standard deviation in parentheses. The p-value in the final column is based on a two-tailed paired t-test.

Pairwise t-tests found that differences in token duration and the first formant frequency were significantly different between noun and verb tokens (see Table 3 for t statistics and probabilities). Noun tokens showed greater within category variation than verb tokens did on measures of duration and pitch. However, verbs showed greater variation than nouns in terms of vowel quality. Because there are significant differences in the prosodic properties and vowel quality of noun and verb tokens, we predict that learners will be able to discriminate noun and verb tokens of the same word types based on their perceptual properties alone. However, the differences in variation between the two groups suggest that this ability may be affected by the category to which infants are habituated.

Our noun stimuli have greater variation in terms of pitch and duration than do our verb stimuli. If infants’ categorization is based on these features, we would predict that those habituated to verb tokens would form a tight category and dishabituate to noun tokens. However, infants habituated to noun tokens would form a broad category and fail to recover looking to verb tokens. On the other hand, our verb stimuli have greater variation in terms of vowel quality than do our noun stimuli. If infants’ categorization is sensitive to this feature, we would predict that those habituated to verbs would form a broad category and fail to dishabituate to noun tokens, while those habituated to nouns would form a tight category and recover looking to verb tokens.

Procedure

Infants’ ability to distinguish noun and verb uses of the same words was tested via an infant-controlled habituation paradigm. Each infant was seated in a testing room on a caregiver’s lap, while the caregiver listened to masking music over headphones. The infant’s gaze was coded by an experimenter observing via video camera from a separate control room where the audio stimuli could not be heard. At the beginning of each trial, a computer monitor mounted on the wall in front of the infant displayed a flashing yellow ball to attract the infant’s attention. Once the infant oriented toward the monitor, the yellow ball was replaced with a static black and white checkerboard pattern, and the audio stimulus began to play. The audio stimulus was contingent on the infant’s looking and played only when the infant looked at the monitor. Each habituation trial lasted for a minimum of 2.5 seconds and a maximum of 15 seconds or until the infant looked away for at least 2 continuous seconds, whichever came first. The average looking time on the first three habituation trials was the baseline looking time for the infant. The habituation criterion was reached when the average looking time on three sequential trials (not including the baseline trials) declined to less than 65% of the baseline looking time. Two test trials followed the same format as the habituation trials. The dependent measure was the length of time the infant listened to each of the two test trials.

Design

For each of seven monosyllabic word types, four noun tokens and four verb tokens were extracted from the audio recordings of the mother in the Lily corpus. The word types were dance, drink, help, kiss, rest, slide, and swing. Tokens were selected on the basis of having little extraneous noise and low co-articulation with surrounding words. The audio track for each token was extracted from the video using SoundConverter and edited using PRAAT (Boersma & Weenink, 2008). Amplitude was normalized across tokens. Two sets of noun stimuli were created by randomly assigning two noun tokens of each word type to each set. Two sets of verb stimuli were created the same way. All stimulus sets contained unique, isolated tokens of the same word types. Each infant was habituated to one stimulus set. One-quarter of the participants was habituated to each of the four stimulus sets. In each trial, a new ordering of tokens was presented, created by randomly sampling from the stimulus set without replacement. An interstimulus interval of 500 ms was used.

When the infant reached the habituation criterion, two test trials were presented. On the “same” test trial, the infant heard the tokens from the other stimulus set that were of the same grammatical category. On the “switch” test trial, the infant heard the tokens from one of the stimulus sets containing items from the non-habituated category. Importantly, all tokens in both test trials were novel, but in the “same” trial they were tokens of the habituated category and in the “switch” trial, they were tokens of the other category. Order of test trials was counterbalanced across subjects.

Results

There was no difference in total time to habituation between infants habituated to nouns and those habituated to verbs (mean for nouns = 65.7 s, SD = 24.7; mean for verbs = 65.6 s, SD = 31.3, t(17) = 0.01, p = .99). Infants did not display any initial preference for or greater interest in either category of items.

Data from the test trials are presented in Figure 4. Infants listened to “switch” test trials for a mean of 5.6 s (SD = 2.5) and to “same” test trials for a mean of 5.0 s (SD = 2.1). This difference is not significant (t(35) = 1.07, p = .29, two-tailed, d = .25). A 2 (test trial) by 2 (habituated category) by 2 (sex) repeated measures ANOVA revealed a marginal three-way interaction (F(1, 1, 34) = 2.83, p = .10), no interaction of trial by sex (F(1, 34) = 2.08, p = .16) and no interaction of trial by habituated category (F(1, 34) = .73, p = .40). This indicates that our Prediction A was incorrect.

FIGURE 4.

Results of the habituation study indicate that infants do not significantly prefer word usages from a new category over those from the habituated one (t(35) = 1.07, p = .29, two-tailed).

Differences in within-category variability are known to produce asymmetric preferences in infant looking behavior (e.g., Quinn et al., 1993). Specifically, infants habituated to a category with high variability might form a broad category and not dishabituate; those habituated to a category with low variability might form a narrower category and recover looking time on the “switch” trial. Because our naturalistic stimuli contain differing degrees of within-category variability, such an asymmetry would be obscured in the omnibus analysis. Therefore, planned comparisons were performed to compare looking time on test trials by habituated category. Infants habituated to verb tokens listened to “switch” test trials for a mean of 5.0 s (SD = 1.9) and to the “same” test trial for a mean of 5.4 s (SD = 2.1). This difference is not significant (t(17) = .50, p = .63, two-tailed, d = .20). However, those habituated to noun tokens listened significantly longer to the “switch” trial (mean = 6.3 s, SD = 2.9) than to the “same” trial (mean = 4.7 s, SD = 2.2, t(17) = 2.25, p = .038, two-tailed, d = .61). The looking times on test trials by habituated category are presented in Figure 5. These results are consistent with the formation of a broad category of verb tokens and a narrow category of noun tokens.

FIGURE 5.

Results of the habituation study, broken down by habituated category. The interaction is not significant (F(1, 34) = .73, p = .40). However, planned t-tests show a significant preference for the switch trial in infants habituated to nouns (t(17) = 2.25, p = .038, two-tailed, d = .61). The preference for the same trial shown by infants habituated to verbs is not significant t(17) = .50, p = .63, two-tailed, d = .20).

Although infants showed no overall ability to discriminate noun tokens from verb tokens of the same words based on perceptual information alone, those infants habituated to noun tokens were able to make this discrimination while infants habituated to verb tokens were not. This suggests that the noun tokens used in this study were more coherent as a category than were the verb tokens. The differences in vowel quality between the two sets of stimuli account for this difference. The standard deviations of both the first and second formant frequencies from the verb stimuli are greater than those of the formant frequencies of the noun stimuli. Nouns are a more coherent class along these dimensions. This result suggests that the prosodic cues, such as token duration and pitch, were given less weight for the purposes of category formation than vowel quality cues. One explanation for this preference might be that the tokens used in this study were excised from running speech, thereby removing the reference frames that inform judgments of duration and pitch. Vowel quality is known to predict syntactic class in disyllabic words (e.g., REcord and reCORD); however, a full analysis of the reliability these cues in monosyllabic words has not, to our knowledge, been conducted. This opens a potentially interesting path for future work.

Because infants are able to distinguish noun and verb tokens of the same words based only on perceptual cues, it is possible that they could use this information to avoid the problem of ambicategoricality in acquisition. Rather than learning a single word that can be used as both a noun and a verb, they might learn two distinct, semi-homophonous forms, one that appears in noun environments and one that appears in verb environments. Of course, these perceptual cues may be only one source of information that learners use to make this distinction, but they appear to be available to even very young language learners. If children learn perceptually distinct forms, ambicategorical words should pose no problems for language learning. If they do not, however, such words should be more difficult to learn or may be used in only one category. This raises the issue of whether children will use word types in both noun and verb contexts. If they do, this suggests that they are able to distinguish between uses in each category. To address this, we examined the child speech from the six corpora analyzed in Study 1 for cross-category word use.

STUDY 3

Thus far, we have demonstrated that caregivers use some words as both nouns and verbs when talking to their children. Furthermore, infants are able to discriminate noun from verb uses of the same words based only on their perceptual properties. Such sensitivity alone, however, does not mean that learners are able to use those properties in natural language learning situations. If they are not sensitive to these cues in natural settings, they should use a single word only in one category due to the well-documented tendency of children to restrict a single form to a single function (Slobin, 1973) or to regularize irregular language input (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1984; Hudson Kam & Newport, 2005). If, however, children use perceptual information to learn not one word that is ambicategorical but two semi-homophonous forms, one that is a noun and one that is a verb, they should be able to use words across category boundaries in their early productions. While there are many reports of preschool-aged children productively using nouns as verbs (e.g., Bushnell & Maratsos, 1984; Clark, 1982), previous analyses of children’s use of words that are ambicategorical to adults have focused primarily on the ways in which lexical semantics interact with children’s cross-category use (Barner, 2001; Oshima-Takane et al., 2001) or have been restricted either in terms of number of word types (Nelson, 1995) or age range (Barner; Oshima-Takane et al.). The question of how children use words that are ambiguous in the target language has yet to be resolved.

To address this issue, we performed two different corpus analyses. The first assessed whether young children use words across category boundaries at all, and the second compared children’s use of individual ambicategorical words to their mothers’ use of those words. If these children use words across category boundaries, then they must be able to incorporate grammatical category ambiguity into their earliest combinatorial speech. Furthermore, unless children are distinguishing noun and verb uses of the same word, there should be no relationship between their use of a word across category and their caregivers’ use of that word. If their use of ambicategorical words is well-predicted by that of their caregivers, this would suggest that children are able to dissociate noun and verb tokens and that their use of these words as nouns and verbs is a product of the statistics of their linguistic environments.

Method

The child speech from the six longitudinal corpora used in Study 1 was examined. For each corpus, the numbers of child uses of each word type were counted, as in Study 1, with morphologically complex words treated as individual types. Again, three frequency ranges were chosen for analysis. High frequency words are those used more than 150 times by the child, middle frequency words are those used 40–60 times, and low frequency words are those used 3–10 times. Within each frequency range, words were classified as in Study 1. The breakdown of number of types analyzed in each corpus is shown in Table 4. Classification was done by trained coders. To ensure reliability, 5% of all word types were reclassified by a second coder. Reliability between coders was high (Cohen’s K = 0.81).

TABLE 4.

Number of types analyzed for each frequency range in each corpus of child speech

| No. Noun or Verb Types | No. Potentially Ambicategorical | No. Used Across Categories | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Middle | Low | Total | High | Middle | Low | Total | High | Middle | Low | Total | |

| Alex | 22 | 32 | 374 | 428 | 7 | 14 | 96 | 117 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 20 |

| Ethan | 17 | 38 | 646 | 701 | 4 | 15 | 170 | 189 | 3 | 4 | 24 | 31 |

| Lily | 30 | 58 | 718 | 806 | 8 | 22 | 178 | 208 | 3 | 3 | 19 | 25 |

| Nina | 43 | 73 | 563 | 679 | 16 | 31 | 147 | 194 | 3 | 6 | 19 | 28 |

| Violet | 13 | 11 | 460 | 484 | 5 | 6 | 131 | 142 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 |

| William | 15 | 21 | 394 | 430 | 5 | 9 | 108 | 122 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 18 |

High frequency words are those with >150 tokens, middle frequency words are those with 40–60 tokens and low frequency words are those with 3–10 tokens in the given corpus. The total is the sum of these three ranges.

The total proportion of potentially ambicategorical words that were actually used across category was calculated for each child as the number of words used at least once as both noun and verb divided by the total number of potentially ambiguous words analyzed. To obtain a better idea of how ambicategoricality relates to frequency of use, the same kind of calculation was done on only those word types within each frequency range for each child. These numbers provide an estimate of what proportion of the word types used by each child were used across category boundaries at least once.

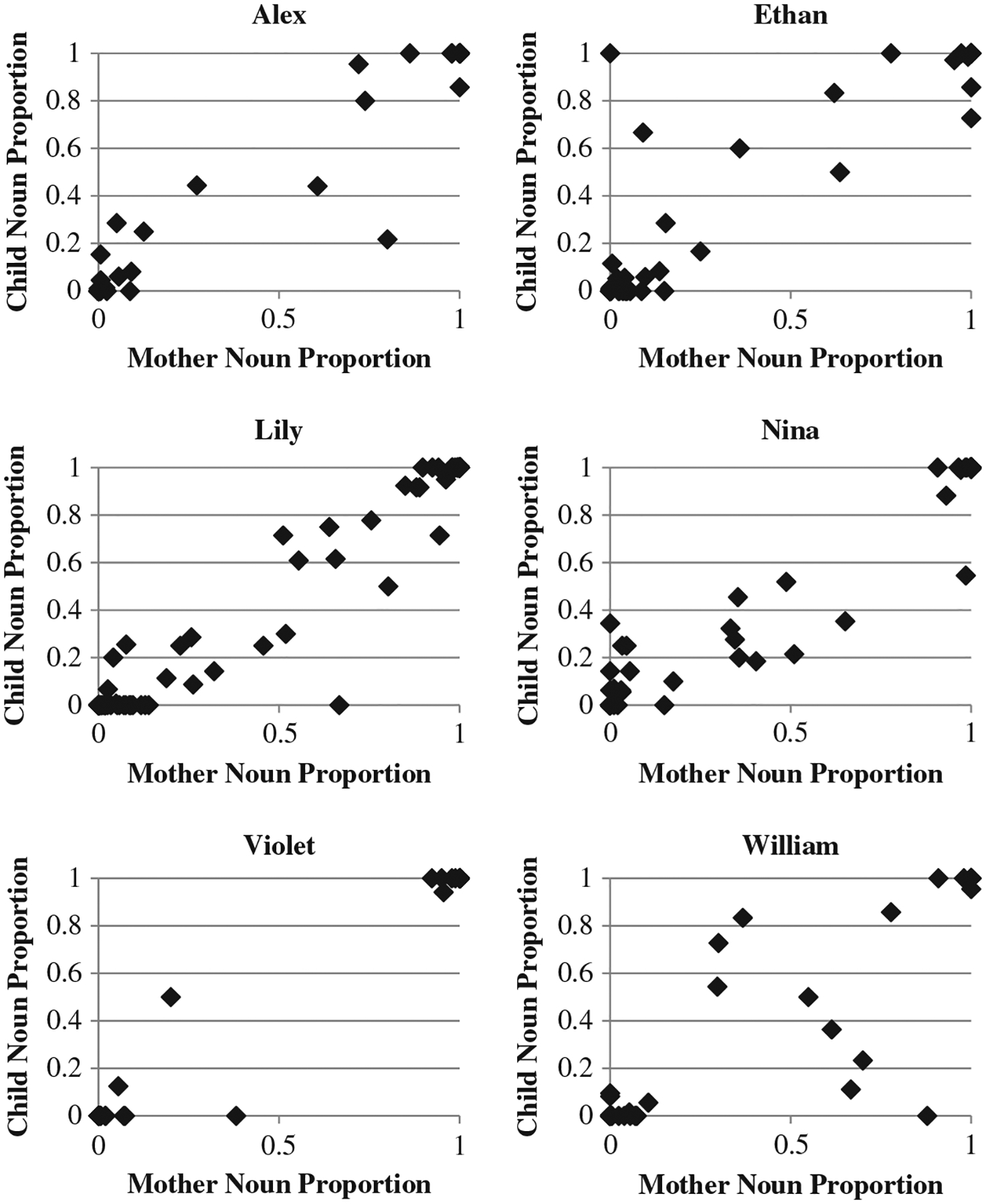

However, because a given frequency range for a particular child does not necessarily contain the same word types as that frequency range for his or her mother, it is not possible to directly compare these data with the data from Study 1. To determine whether a child’s use of a particular word across category boundaries is well-predicted by his or her mother’s use of that word, a second corpus analysis was performed. Within a mother-child dyad, all tokens of each word type in the high and middle frequency ranges for the mother were extracted from the child’s speech and coded as noun, verb or other, as described above. Likewise, all tokens of each word type in the high and middle frequency ranges for the child were extracted from the mother’s speech and coded as described above. This allowed us to calculate the proportion of noun uses of each word type for each speaker. Proportion of noun use for a given word type was calculated as the number of noun uses of that type divided by the total number of noun and verb uses of that word type. If a word was only used as a noun, it would have a proportional noun use of 1. Words used only as verbs would have a proportional noun use of 0. For each word type, this calculation was performed on maternal tokens to obtain maternal proportion of noun use and on child tokens to obtain child proportion of noun use. A correlation analysis on these values within a dyad will reveal the extent to which maternal use of a word in a given category predicts child use in a category.

Results

When all analyzed word types were considered, the proportion of potentially ambiguous words used across category boundaries by the children ranged from .12–.17. This rate is slightly higher than that described by Barner (2001), who found that the proportion of words used as both noun and verb ranged from .04–.11, depending on lexical semantics. The discrepancy may be the result of increased cross-category use with improved grammatical ability; our corpora included speech from children at older ages than those considered by Barner. Figure 6 shows how frequency of use relates to the likelihood that a child will use a word as both noun and verb. Recall that the proportions of ambicategorical use by mothers ranged from .19–.32. The children used a smaller proportion of words across categories than their mothers did, although this may be a function of a smaller number of word types in the children’s speech than in that of their mothers. Like their mothers, these children do not use as many words as they could across category boundaries but do show some cross-category word use. This indicates that children are not strictly adhering to the principle of one-form/one-function but rather flexibly using some words as both noun and verb. These results do not, however, demonstrate that children use the same words across category as their mothers do.

FIGURE 6.

For each child, the proportion of potentially ambicategorical words that are actually used across categories is reported for each of three frequency ranges.

The results of the analysis comparing children’s cross-category use of particular lexical items to that of their mothers are presented in Figure 7. For all children, use of a particular word was well-predicted by their mothers’ use of that word (all R>.93, all p<.01, two-tailed). However, it is possible that because most potentially ambicategorical words were not used across category by either the mother or the child, these words are driving the correlation. That children’s very early utterances do not include spontaneous (as opposed to attested) cross-category use is unsurprising. Overgeneralizations and creative word use often do not appear until the third or fourth year of life (Clark, 1982; Tomasello, 2000). Therefore, an important test of the extent to which maternal use of a word across category boundaries predicts the child’s use of the word is whether these correlations remain strong when only those words that are used as both noun and verb are included in the analysis. To this end, we removed those words that are used in only one category by both the mother and the child and recalculated the correlations. For five of the six children, this had only a small effect on the correlations (all R>.90, all p<.01, two-tailed). However, in the William corpus, the correlation decreased notably, although it remained highly significant (R=.73, p<.01, two-tailed). While it is difficult to tell exactly why William’s cross-category word use was less correlated with his mother’s than that of the other children, it is important to note that, of all the children analyzed, William was the only one with siblings much older than himself. It is possible that the presence of more interlocutors resulted in a more variable linguistic environment for William, which would explain the lower correlation of his word use with that of his mother.

FIGURE 7.

For each ambicategorical word analyzed in each corpus, proportional noun use by the child is plotted against proportional noun use by the mother. All correlations are significant (R>.73, p<.01, two-tailed).

These results may reflect that, due to the conversational contexts in which they are apt to be used, some words are simply more likely to be used more in one category than another by talkers in general. In this case, the high correlation of maternal and child noun use of a given word may not be caused by children learning to use words in this way from their mothers but rather by semantic or pragmatic pressures that apply more or less equally to all mothers and children. To determine whether this is the case, the proportional noun use for each word type for each child was compared to the proportional noun use of each word type used by a different mother. Correlations between maternal and child noun use of the same word types were calculated again, but each child was paired with a new mother. Because there are gender-specific cross-category uses of some words (e.g., dress), children were paired with a mother whose child was of the same sex. The results of these correlations as well as the correlations of each child with his/her own mother are presented in Table 5. For all children, the correlation of noun use of a word with adult noun use of that word decreased when the child was not paired with his/her own mother. However, all of these correlations remain significant (p<.01, two-tailed). To assess the statistical significance of these changes, these data were entered into a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. Child usage was the dependent variable and the usage of another child’s mother was the first independent variable. Then, the usage of words by the child’s own mother was entered into the regression to determine whether it conferred an advantage over and above the baseline provided by the other mother. The R2 values for each model, as well as the changes in F-values and the p-values for those changes, are reported in Table 5. For five of six children, the increase in R2 with the addition of own mother was statistically significant (all F(change)>14.5, all p<.005). William is again the exception to the general pattern (F(change)=1.17, p=.29). All of these analyses only included those words that were used ambiguously by at least one of the speakers being compared.

TABLE 5.

Correlations of child and maternal noun usage of particular word types, as well as the results of the hierarchical multiple regression of child usage with another mother’s usage and his/her own mother’s usage

| Own Mother Correlation | Other Mother Correlation | Other Mother R2 | Own Mother + Other Mother R2 | F (change in R2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | .91** | .67** | .63 | .83 | 19.77** |

| Ethan | .92** | .73** | .64 | .83 | 32.00** |

| Lily | .95** | .87** | .90 | .96 | 87.94** |

| Nina | .91** | .76** | .62 | .83 | 36.09** |

| Violet | .96** | .93** | .83 | .91 | 14.86* |

| William | .73** | .71** | .57 | .59 | 1.19 (n.s.) |

indicates significance at a level of p<.005 and

indicates significance at a level of p<.001.

These results indicate that children’s cross-category use of words that are noun/verb ambiguous is driven partly by speaker-general contextual or cultural factors and partly by speaker-specific patterns of usage in children’s individual experience. Although children’s cross-category use of words correlated with that of different mothers of children of the same sex, the significant improvement in the fit of the regression model with the addition of maternal use indicates a major role of the speech environment in determining how children use particular words. The fact that children not only use words as both noun and verb but also that they do so in a way that mirrors their own mothers’ usage suggests that they can distinguish between verb uses and noun uses of the same words in their everyday experience. These findings cannot directly address the issue of how children make this distinction, but it is not clear how learners would so precisely mirror the statistics of their environment were they not somehow sensitive to the difference between a noun use and a verb use of the same word.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

This article set out to empirically evaluate the potential problem posed to language learners by cross-category word use. If children learn about grammatical categories based on their distribution relative to other words, ambicategorical words could cause learners to conflate category distributions and create categories that contain both nouns and verbs. To address this potential problem, this paper first asked whether children hear words used as both noun and verb. We find that mothers do use words across category boundaries when talking to their children, although not to the fullest possible extent. Secondly, we asked whether infants might be sensitive to cues other than distribution that separate noun from verb uses of the same word, such as perceptual differences between the two categories. Our habituation study shows that they are able to do so. Finally, to assess whether language learners might be able to use this information in natural language learning, we examined children’s use of words across categories, both whether children did so at all and how their use of a given word type was determined by their mothers’ use of that word. We find that children not only use words across category boundaries in their natural productions, but that they also do so in a way that reflects their mothers’ patterns of use. That is, the proportion of the time that a word is used as a noun by a child is closely correlated with the proportion of the time that the child’s mother uses the word as a noun. Taken together, all of these results suggest that cross-category usage need not pose a major problem to language learners because there are cues available to them in the speech signal that allow them to distinguish noun and verb uses of the same word. They may, therefore, effectively learn two words, one that is a noun and one that is a verb, rather than contending with the problem of words that can be used across category boundaries.

The results of our habituation study indicate that children are able to use information available in the speech stream to categorize noun and verb tokens of the same word types. This, in turn, may allow them to avoid conflating noun and verb distributions while they are learning the syntax of their native language. That they themselves are able to use the same word as both a noun and a verb is further evidence that they are not confused by cross-category usage. If cross-category usage were a hindrance to word learning, children’s acquisition of such words would likely be delayed. If children were to restrict the use of ambicategorical words to a single category, this would suggest that they are unable to incorporate cross-category behavior into their developing language system. Neither of these predictions is borne out by the results of our corpus study. However, these results run counter to predictions that would be made given several well-attested phenomena in child language development.

First of all, there is evidence that children prefer to restrict their use of a particular form to a single grammatical function (sometimes called the principle of one-form/one-function; Slobin, 1973). Language learners also tend to resist homonymy3 (Casenhiser, 2005) and prefer to assign a novel word to a referent for which they do not already have a label (e.g., Markman & Wachtel, 1988; Clark, 1988; Golinkoff, Mervis, & Hirsh-Pasek, 1994). For 14-month-old infants, this difficulty may extend to near homophones, as there is evidence that they do not assign a label to novel object if that label is phonetically similar to that of a known object (Stager & Werker, 1997). Given these two tendencies of language learners, it seems surprising that we would observe any cross-category word use at all by young children. Furthermore, children should have great difficulty learning the meanings of words that are applied to more than one referent and their acquisition of these words should be delayed. However, this is not the case.

Children are also reported to regularize irregular input (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1984; Hudson Kam & Newport, 2005). In some learning situations, such as when primary exposure to a language comes from a nonnative speaker, children receive linguistic input that is irregular or where the grammar is inconsistently used. These children tend to produce language with more consistent grammar, indicating that they are regularizing their language rather than reproducing the statistics of their experience (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander). In laboratory studies of artificial language learning, children who receive irregular or inconsistent information appear to derive consistent rules or schema for use in production, rather than learning the frequency patterns of the language (Hudson Kam & Newport). Further work on home-sign indicates that, in the absence of typical input, a child will maintain a separation between nouns and verbs (Goldin-Meadow et al., 1994). These kinds of results appear to be in direct conflict with our findings that young children not only use words across category boundaries, but that they do so in a way that reflects the statistics of their language environments. That is, children do not regularize irregular linguistic experience by restricting a word to a single category. Rather, they reproduce the statistics of the language they hear.

However, our results can be interpreted in such a way that they complement these well-known findings rather than contradict them. Because children are able to differentiate noun from verb tokens of the same word based only on the perceptual cues available in that word, perhaps they are not learning a single word that can be both a noun and a verb. That is, perhaps these words are not homophones for the learner. Instead, they may be learning two words, differentiated by these subphonemic cues, one that appears in noun contexts and one that appears in verb contexts. This strategy would allow them to avoid the problem of ambicategoricality until their knowledge of syntax is robust enough to accommodate cross-category usage of the same word.

The finding that children can discriminate noun and verb tokens of the same word based on their perceptual properties alone bolsters this claim but does not provide unequivocal support for it. The more important finding in support of this hypothesis is that young children will use particular ambicategorical words across category boundaries about as often as their mothers do. This suggests that in real world learning situations children are able to differentiate their mothers’ noun and verb uses of ambicategorical words and that they treat these uses as separate in their interpretation and production of language. They may, therefore, be learning two words rather than one that is used across categories. Further support for this claim might come from a word-learning study in which children are introduced to two uses of a word form that either differ along these perceptual dimensions or are perceptually identical. If children do incorporate these subtle perceptual cues into their lexical representations, the case where the distinct uses are supported by such cues should be easier for young children. Such a study is outside the scope of the current article but presents a very interesting direction for further research. If children do represent ambicategorical words as two distinct, semi-homophonous forms, how (indeed, whether) they eventually collapse these two words into a single word remains an important empirical question.

This study focused on the perceptual cues to grammatical category that children might use to learn about ambicategoricality. These cues might arise because talkers intend to (at some level) distinguish between noun and verb uses of phonemically identical forms or because talkers characteristically produce noun and verb tokens in distinct syntactic contexts and positions. Regardless, particular cues, most notably duration and vowel quality, are associated with noun and verb categories; Study 2 shows that infants can use these cues to distinguish tokens presented in isolation. In context, learners may use these cues for other purposes as well, such as locating phrase, clause, or utterance boundaries (Nazzi, Kemler Nelson, Jusczyk, & Jusczyk, 2000; Soderstrom, Seidl, Kemler Nelson, & Jusczyk, 2003), but there is no principled reason why this should preclude the simultaneous use of such information for inferring grammatical categories of words (see also Monaghan, Chater, & Christiansen, 2005, and Monaghan et al., 2007, for discussion of the combined use of phonological and distributional cues for category learning).

Prosody and vowel quality are only two cues that might be available for helping children solve the ambicategoricality problem. Other sources of information may also be relevant. Meaning may also offer cues that would allow children to distinguish noun and verb tokens of the same word, especially in those cases where the two words are homophonous, rather than derived. How meaning could cue grammatical category in situations where the noun and verb forms of a word refer to the same event or action remains unclear. In languages other than English, derivational morphology may provide information that words are being used across category boundaries. However, the absence of overt morphology for many noun/verb pairs in English may limit the extent to which such cues are useful. Nevertheless, the potential contributions of these two sources of information to the problem of resolving ambicategoricality in acquisition are potential avenues of further research. Also, this paper focused only on words that are ambiguous between noun and verb uses. There are also words that are ambiguous between noun and adjective or adjective and verb uses. The issues of how mothers and children use such words and what cues might be available to children for learning about them remain unaddressed but could also provide fodder for further work in this area.

CONCLUSION

Although mothers do use some words as both nouns and verbs when speaking to their children, the problem of cross-category usage of nouns and verbs for English-learning children is more apparent than real. Instead, even very young children may be able to use subtle perceptual cues, among other sources of information, that are available in the language they hear to differentiate noun and verb uses of the same words without relying on syntactic information. This would allow children to learn and use ambicategorical words in a manner commensurate with the statistics of their linguistic environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant HD-32005 to JLM and the Peder Estrup Graduate Research Fellowship to EC. We wish to thank Katherine Demuth for access to the Demuth Providence Corpus; Mark Johnson for assistance with the Brown Corpus; Rachel Ostrand, David Richardson, David Mittelman, and Sally Grapin for assistance with data coding; Lori Rolfe, Megan Blossom, and Glenda Molina for their help recruiting and running subjects; and Melanie Soderstrom and Katherine White for helpful comments on previous drafts. An earlier version of this work was presented at the 31st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, and the data reported in this article formed part of the first author’s dissertation at Brown University.

Footnotes

In French, for example, the participle form of many verbs may also be used as an adjective.

The Brown Corpus consists of written texts, which limits its accuracy in reflecting typical adult-directed speech, and there are many words that are not used ambicategorically in the Brown Corpus that have very natural cross-category uses in adult speech (e.g., comb). However, there exist no comparably large corpora of spoken adult American English that have been hand-tagged for part of speech. Many corpora (e.g., the CHILDES corpus) have been machine-tagged for part of speech, but automated part of speech taggers make significant errors on ambiguous words.

Interestingly, Casenhiser (2005) also finds that learners are more willing to use a homophonous word if it has a different grammatical category than its homophone. These studies were, however, conducted with school-aged children.

Contributor Information

Erin Conwell, Department of Psychology, North Dakota State University, and Department of Cognitive and Linguistic Sciences, Brown University.

James L. Morgan, Department of Cognitive and Linguistic Sciences, Brown University

REFERENCES

- Akhtar N (1999). Acquiring basic word order: Evidence for data-driven learning of syntactic structure. Journal of Child Language, 26, 339–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barner D (2001). Light verbs and the flexible use of words as noun and verb in early language learning. (Unpublished Master’s thesis). Montreal, Quebec: McGill University. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma P, & Weenink D (2008). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 5.0.15) Available from http://www.praat.org

- Bowerman M (1982). Evaluating competing linguistic models with language acquisition data: Implications of developmental errors with causative verbs. Quaderni di Semantica, 3, 5–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R (1973). A first language: The early stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell EW, & Maratsos MP (1984). “Spooning” and “basketing”: Children’s dealing with accidental gaps in the lexicon. Child Development, 55, 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright TA, & Brent MR (1997). Syntactic categorization in early language acquisition: Formalizing the role of distributional analysis. Cognition, 63, 121–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casenhiser DM (2005). Children’s resistance to homonymy: An experimental study of pseudohomonyms. Journal of Child Language, 32, 319–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EV (1982). The young word maker: A case study of innovation in the child’s lexicon. In Wanner E & Gleitman LR (Eds.), Language acquisition: The state of the art. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark EV (1988). On the logic of contrast. Journal of Child Language, 15, 317–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EV, & Clark HH (1979). When nouns surface as verbs. Language, 55, 767–811. [Google Scholar]

- Conwell E (2008). Resolving ambicategoricality in language acquisition: The role of perceptual cues. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Brown University, Providence, RI. [Google Scholar]

- Conwell E, & Demuth K (2007). Early syntactic productivity: Evidence from dative shift. Cognition, 103, 163–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell E, & Morgan JL (2008). Learning about cross-category word use: The role of prosodic cues. Poster presented at the 16th International Conference on Infant Studies, Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth K, Culbertson J, & Alter J (2006). Word-minimality, epenthesis and coda licensing in the acquisition of English. Language and Speech, 49, 137–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth K, Machobane M, & Moloi F (2003). Rules and construction effects in learning the argument structure of verbs. Journal of Child Language, 30, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CA (1964). Baby talk in six languages. American Anthropologist, 66, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Taeschner T, Dunn J, Papousek M, Boysson-Bardies B, & Fukui I (1989). A cross-language study of prosodic modifications in mothers’ and fathers’ speech to preverbal infants. Journal of Child Language, 16, 477–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C, & Tokura H (1996). Acoustic cues to grammatical structure in infant-directed speech: Cross-linguistic evidence. Child Development, 67, 3192–3218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis WN, & Kucera H (1983). Frequency analysis of English usage: Lexicon and grammar. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer SD, & Younger BA (2006). Beyond the distributional input? A developmental investigation of asymmetry in infants’ categorization of cats and dogs. Developmental Science, 8, 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahl S (2008). Time and thyme are not homophones: The effect of lemma frequency on word durations in spontaneous speech. Language, 84, 474–496. [Google Scholar]

- Gleitman LR, & Wanner E (1982). Language acquisition: The state of the state of the art. In Wanner E & Gleitman LR (Eds.), Language acquisition: The state of the art. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, & Mylander C (1984). Gestural communication in deaf children: The effects and noneffects of parental input on early language development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 49(3/4), 1–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Butcher C, Mylander C, & Dodge M (1994). Nouns and verbs in a self-styled gesture system: What’s in a name? Cognitive Psychology, 27, 259–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]