Abstract

We propose that a major contribution of juvenile and adult hippocampal neurogenesis is to allow behavioral experience to sculpt dentate gyrus connectivity such that sensory attributes that are relevant to the animal’s environment are more strongly represented. This “specialized” dentate is then able to store a larger number of discriminable memory representations. Our hypothesis builds on accumulating evidence that neurogenesis declines to low levels prior to adulthood in many species. Rather than being necessary for ongoing hippocampal function, as several current theories posit, we argue that neurogenesis has primarily a prospective function, in that it allows experience to shape hippocampal circuits and optimize them for future learning in the particular environment in which the animal lives. Using an anatomically-based simulation of the hippocampus (BACON), we demonstrate that environmental sculpting of this kind would reduce overlap among hippocampal memory representations and provide representation cells with more information about an animal’s current situation; consequently, it would allow more memories to be stored and accurately recalled without significant interference. We describe several new, testable predictions generated by the sculpting hypothesis and evaluate the hypothesis with respect to existing evidence. We argue that the sculpting hypothesis provides a strong rationale for why juvenile and adult neurogenesis occurs specifically in the dentate gyrus and why it declines significantly prior to adulthood.

Keywords: adult neurogenesis, hippocampus, memory, dentate gyrus

Introduction

It is widely believed that the hippocampus is responsible for the fast learning of life events (episodic memory) and other declarative memories (Squire, 2004). It is also well known, and a topic of intense current interest, that the granule cells of the hippocampus’s dentate gyrus (DG) are one of a small number of neural populations that continue to be born and develop well after birth (Altman and Das, 1965; Cameron and McKay, 2001; Deng et al., 2010; van Praag et al., 2002). However, there is little understanding of why such extended postnatal neurogenesis should occur specifically within the DG. There are currently three dominant hypotheses. One, which we will call the “Temporal Coding Hypothesis,” specifies that neurogenesis provides a mechanism for linking memories formed around the same time and for distinguishing among memories formed at different times (Aimone et al., 2011). The “Memory Clearance Hypothesis”, suggests that neurogenesis clears memories that are no longer needed from the hippocampus, potentially in coordination with systems consolidation and perhaps providing fresh DG cells that can encode new memories (Akers et al., 2014; Frankland et al., 2013; Kitamura and Inokuchi, 2014). Finally, based on animal behavioral experiments, it is frequently postulated that neurogenesis facilitates hippocampal pattern separation and reduces interference among memories that share common elements (Clelland et al., 2009; França et al., 2017; Nakashiba et al., 2012; Sahay et al., 2011). These ideas have generated interesting experiments yielding important information. However, all of them would predict that ongoing neurogenesis is required to maintain the integrity of hippocampal learning and memory processes. Yet, in fact, hippocampal neurogenesis declines markedly in young adult animals (Fig. 1) without catastrophic deterioration of hippocampus-mediated episodic/declarative learning ability (Cushman et al., 2012; Encinas et al., 2011; Snyder, 2019). Furthermore, in humans there is currently a great deal of controversy as to whether neurogenesis continues at all after the early teens (Bergmann et al., 2015; Kempermann et al., 2018; Kozareva et al., 2019; Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2019; Sorrells et al., 2018). Therefore, we feel that the current theoretical perspectives do not provide a strong account of the functional significance of juvenile and adult neurogenesis. Here we advocate an alternative hypothesis in which juvenile and adult neurogenesis is viewed as having primarily a prospective function. According to this hypothesis, such neurogenesis provides a mechanism through which experience can shape future information processing—in essence, optimizing the hippocampus’ ability to remember the kinds of experiences it is likely to encounter in its current living environment.

Fig. 1. In all species examined, neurogenesis declines before onset of old age.

These data are replotted from Snyder (2019), which synthesized several published data sets to construct these curves. Neurogenesis rates are normalized to the level at birth. See Snyder (2019) for details on methodology.

A distinction is often made between “developmentally born” or “embryonically born” cells on the one hand and “postnatally born” or “adult born” cells on the other. In some species (e.g., rats and mice) almost all granule cells are born postnatally, while in others (e.g., humans and other primates) most are born prenatally (Snyder, 2019). In all species studied, juvenile neurogenesis is considerably higher than neurogenesis in mature adults (Charvet and Finlay, 2018). In lieu of the standard terminology, we will refer to “early-born” and “late-born” cells. Early-born cells are cells born early enough to have had time to develop a significant portion of their innervation prior to weaning and before individuals start to have substantial experience navigating their world. Late-born cells are those that are likely to develop most of their innervation after weaning, while the animal is navigating the world during juvenile and adult experience. The critical distinction between these two populations is that the innervation of early-born cells is assumed to be fairly random, having been established during the initial development of the dentate gyrus, which is characterized by network-wide large-depolarizing potentials that are prominent in the pre-weanling hippocampus (Pedroni et al., 2014). Late-born cells, in contrast, integrate into an already established dentate gyrus and have a greater opportunity for their innervation to be influenced by sensory experience of the free-living individual. As a caveat to this, we don’t rule out the possibility that early-born cells could potentially be sculpted by pre-weaning sensory experience or have some capacity for sculpting by post-weaning experience. The distinction is a matter of the degree of sculpting by post-weaning sensory experience, rather than an absolute cut-off.

Furthermore, because the developmental timing of granule cell genesis and the rate of cell maturation differ among species (Snyder, 2018), and little is known about experiential effects on innervation of granule cells born perinatally, our distinction between early- and late-born cells is necessarily speculative. In the mouse, in which many relevant experiments have been done, granule cell innervation commonly begins at around two weeks of cell age and progresses substantially for over a month (for review see Toni and Schinder, 2016). Because weaning occurs at 3 to 4 weeks postnatally, any environmental influence on the innervation of cells born within a few days of an animal’s birth would be expected to be mostly due to pre-weaning conditions, and we would classify them as “early-born,” whereas the innervation of cells born a week or two after birth would be expected to occur entirely after weaning and would fall into our “late-born” category. But, again, relatively little is known about experiential effects on innervation of granule cells born during embryonic and early postnatal development. Furthermore, behavioral experience can influence the speed of granule cell maturation (Piatti et al., 2011; Van Praag et al., 1999) meaning that the definitions of “early-“ and “late-born” could vary even among individuals of the same species. Thus, our distinction between early- and late-born cells is less a conclusion based on evidence than a hypothesis that will require experimental verification.

Our hypothesis is rooted in a theoretical perspective based on Marr’s Theory of the Archicortex. Marr pointed out that some kinds of learning, such as coming to appreciate causal relationships from many exemplars, should be slow, while others, such as forming memories of one-time events, must occur immediately. Based on neural circuit anatomy, he argued that the hippocampus and its connections to cortex might well be responsible for the fast type of learning. His hypothesis was supported by the then-emerging work of Milner on H.M. (Scoville and Milner, 1957), and he developed a theory of hippocampal circuit function that has been elaborated by a number of subsequent workers (e.g., Hasselmo, 1995; Krasne et al., 2015; Marr, 1971; McClelland et al., 1995; McClelland and Goddard, 1996; McNaughton and Morris, 1987; Treves and Rolls, 1994; Willshaw et al., 2015). Marr’s theory attributed specific functions to the DG, and it seemed reasonable to us to ask whether the reason for extended postnatal neurogenesis might be understood in terms of these functions. This inquiry has led us to realize, as we will explain below, that the storage capacity of the hippocampus would be greatly enhanced if DG cells, rather than being innervated by random sets of EC neurons, were preferentially innervated by EC neurons, and combinations of neurons, that are likely to be used to code for environmental features that an animal is likely to experience. We will refer to such features as the “elementary attributes” of the animal’s particular environment.

The hippocampus encodes individual events that can be drawn from a nearly infinite multisensory space of possible combinations. Within an individual lifespan only a small fraction of the potential combinations is likely to be experienced. Preferential innervation would of course require that the innervation of DG neurons be controlled by neural activity and occur postnatally over a period long enough for an individual to experience a wide range of the stimuli and life events that its particular environment offers. We refer to this as the “Environmental Sculpting Hypothesis” of juvenile and adult DG neurogenesis.

In so far as most of the innervation of a DG granule cell occurs when the cell is young, experience-dependent sculpting of innervation would require that DG cells continue to be born for much of the animal’s juvenile and early adult life. We suggest that addition of new “sculptable” neurons is the primary reason for neurogenesis that continues well beyond weaning. We believe it explains why postnatal neurogenesis continues over an extended period but dramatically declines during the juvenile and early-adult periods (Charvet and Finlay, 2018) when an animal has presumably become familiar with its particular living environment (Figure 1; Snyder, 2019). This said, we do not claim that sculpting of innervation occurs only when granule cells are immature, nor do we claim that sculpting is an exclusive property of the dentate gyrus. We propose that juvenile and adult neurogenesis allows a degree of experience-dependent sculpting that would not be possible in its absence. There is good evidence that substantial dendritic growth can occur even in granule cells that are months old (Cole et al., 2020; Lemaire et al., 2012), and studies have shown dendritic changes in the granule cell population as a whole in response to exercise and food restriction (Andrade et al., 2002; Eadie et al., 2005; Redila and Christie, 2006). Furthermore, a number of studies have shown changes in dendritic spine growth in areas outside the dentate gyrus in response to a number of manipulations such as learning, housing enrichment, and sensorimotor training (Comeau et al., 2010; Gisabella et al., 2020; Greenough et al., 1985b, 1985a; Kolb et al., 2003; Marrone, 2005; Villanueva Espino et al., 2020). Thus, while experience-dependent sculpting may be a more general property of brain function, here we propose how it relates specifically to juvenile and adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus.

The sculpting hypothesis is not entirely new. It incorporates ideas with a long history in the field. From a very general perspective it shares origins with a large literature showing that early life experiences can shape the way animals respond to and learn from adult experiences and conditions (e.g. Hanson and Gluckman, 2014; Low and Fitzgerald, 2012; Van Bodegom et al., 2017; Zalosnik et al., 2014; Zhang and Meaney, 2010; McEwen et al, 2015; McEwen et al 2016). More immediately relevant are a number of papers proposing that continuing neurogenesis in the dentate may help the animal adapt to its environment in ways that promote new learning within that particular environment (Cameron and Schoenfeld, 2018; Cushman et al., 2012; DeCostanzo et al., 2019; Glasper et al., 2012; Gould et al., 1999; Miller and Sahay, 2019; Tashiro et al., 2007; Trinchero et al., 2017; Tronel et al., 2010b; Wiskott et al., 2006; Zhuo et al., 2016). Still more directly relevant is work specifically suggesting that neurogenesis promotes the development of DG granule cell innervation patterns that facilitate the ability of the hippocampus to learn things it is likely to encounter in its specific living environment. Indeed, Tronel et al (2010) specifically hypothesized that “...sculpting of dendritic arbors...may be required for subsequent learning.” Cushman et al, 2012 proposed that neurogenesis “provides a mechanism for early postnatal experience to optimize information encoding in the adult brain.” Miller and Sahay (2019) hypothesized that “adult hippocampal neurogenesis ensures generation of mature adult-born dentate granule cells that are representative of previously encoded experiences.” Trinchero et al, 2019 proposed that late-born cells “act as sensors that transduce behavioral stimuli into major network remodeling.” Our hypothesis perhaps owes its greatest debt to Tashiro et al. (2006), who proposed that activity-dependent selective survival of newborn granule cells mediates “information-specific” circuit formation that enhances representation of previously experienced patterns of stimulation. In our view, these ideas have not received the attention they deserve, and they have not been formalized in a way that generates testable predictions. Our goal here is not to develop an entirely new theory but rather to propose specific mechanisms through which sculpting could operate at the circuit level and could impact hippocampal function. To this end, we present computational simulations demonstrating how environmental sculpting could enhance hippocampal memory, evaluate relevant existing evidence, and describe several novel, testable predictions.

The role of the dentate in the formation and recall of hippocampal memories

According to Marr’s theory of the Archicortex and its more recent derivatives, the hippocampus stores episodic memories in such a way that reactivation of a subset of the neocortical cells that were active at the time of an event causes reactivation of a version of the original, full cortical state, which produces recall of the event. Marr’s theory has been elaborated by a host of workers (e.g., Hasselmo, 1995; Krasne et al., 2015; Marr, 1971; McClelland et al., 1995; Treves and Rolls, 1994). It is generally supposed that the neocortical coding of the to-be-remembered event is abstracted onto a pattern of activity within the population of entorhinal cortex cells that project to the hippocampus (ECin). When homologous cells within the entorhinal layer that receives hippocampus output (ECout) are activated, the full cortical replica of the original event is reproduced, thereby activating an episodic memory.

The essence of Marr’s theory and the models that have followed from it is portrayed in Fig. 2. At the time of event encoding, a small group of the most excited of DG’s huge number of granule cells is allowed to fire and drive one or more of the small number of CA3 cells that it innervates. These cells become the hippocampal representation (henceforth just the “representation”) of the event. When this happens, coactive Hebbian synapses from the active ECin cells to the active DG and CA3 cells become potentiated, as do synapses between one active CA3 cell and another. The consequence of the ECin-DG and ECin-CA3 cell potentiation is that when, on future occasions, a fraction of the original ECin cells fire, they excite the CA3 cells that were active at encoding via the potentiated synapses of the ECin-DG-CA3 and ECin-CA3 pathways, and the most strongly excited CA3 cells fire. Then, as the result of the potentiated recurrent CA3-CA3 connections, the full representation is reactivated. At the time of encoding, ECout homologs of all the ECin cells of the original event also fire, and synapses in the pathway from the active CA3 representation cells to the active ECout cells become potentiated. Consequently, when the representation is activated, so too are the ECout cells corresponding to the original event, and this in turn reactivates a version of the event’s full original neocortical activity pattern.

Fig. 2. The hippocampal model.

Computations were performed using BACON, a simplified version of Marr’s Archicortex model. Episodic and context memory acquisition depends on plasticity at ECin–DG, ECin–CA3, CA3–CA3, and CA3–ECout synapses, which are highlighted in green. A small set of DG cells (of size K) and their corresponding CA3 followers will become the hippocampal representation of an event being stored. The K cells chosen for the representation will be those that are most heavily innervated by the cortical (EC) cells coding the event. To simplify computations the model assumes that each DG cell innervates one dedicated DG follower (rather than a small number), and that each CA3 cell recurrently innervates every other CA3 cell (rather than only a proportion) and directly innervates each ECout cell (instead of doing so via CA1); the rationales for these simplifications are discussed in Krasne et al (2015). For the computations of Fig. 5 we assumed (following O’Reilly and McClelland, 1994) 200,000 ECin and ECout cells, 12,500 of which fully characterized an event (or context), 1 million DG cells, 4,000 ECin inputs to each DG cell, and K=4,000. In BACON, as in the biological hippocampus, EC innervates CA3 both directly and indirectly via the DG, and both pathways appear to be involved during recall [There has been some discussion to the contrary in the literature but we think the weight of both evidence and logic say this is so—see Krasne et al, 2015 for a theoretical discussion and Bernier et al, 2017 for an empirical one]. During encoding, those DG cells that are most richly innervated by the active EC cells, together with their CA3 followers, are selected to become the new representation. Because it is the richness of innervation of the DG cells themselves that is the basis for this selection, they have richer input from the relevant EC cells than do their CA3 followers. Consequently, during recall the indirect pathway provides richer information about the situation/context than does the direct one, and optimal performance is obtained when the indirect pathway is made considerably stronger than the direct one. Because using the indirect pathway alone impairs performance only slightly (see Krasne et al, 2015, Fig. 8), we have used only the indirect pathway to simplify the simulations for Figs. 4 and 5.

For this memory encoding and recall strategy to be successful, there should be relatively little overlap among the representation cells for different events. In addition, hippocampal representation cells should be richly innervated by ECin cells that provide useful information about the events being encoded. If there is excessive overlap among the cell ensembles that represent different events, mixed ECout patterns would be produced during recall, reducing recall accuracy. Both pattern separation and richness of innervation will be greater when representation cells are chosen from a large population of cells. It is believed that this is why DG has such a large population of granule cells. The advantages of a large DG, however, can only be realized if the full DG is used. If, as we suggested in our introduction, an animal’s particular life circumstances recruit only a subset of its EC cells, then the benefits conferred by a large DG would not be fully realized. In that case, there would be great advantage if DG granule cells were preferentially innervated by those ECin cells that had the potential to be activated in an animal’s particular environment. For this reason, we propose that DG cells, rather than being innervated by random sets of the EC neurons, are preferentially innervated by EC neurons, or combinations of neurons, that code for environmental features that may actually occur in a given animal’s living environment, what we call the “elementary attributes” of the animal’s particular environment.

Some calculations

To illustrate the possible merits of environmental sculpting of DG innervation, we have used a simple model of EC, DG, and CA3 that incorporates Marr-like ideas in a simplified form that facilitates computation. The model is a portion of a recently published model of context fear conditioning, the Bayesian Context Fear Algorithm or “BACON” (Bernier et al., 2017; Krasne et al., 2015), that can reproduce a number of features of context fear conditioning. It is believed that the hippocampus works similarly when creating and recalling representations of contexts and life events. We presume that a given animal’s living situation will only allow a modest subset of all possible contexts (or events) to occur. To make simple computations possible, this idea was implemented in our simulations by stipulating that in any given environment only a fraction of the total set of EC cells is actually used and that events that are encoded are random selections of that subset of EC. We then compared the performance of BACON when DG was innervated at a given density by all of ECin versus only by the subset from which our events were constructed. Fig. 3 portrays this simplified conception of the non-sculpted and sculpted circuit used for performing calculations and simulations.

Figure 3. Caricature of sculpting effects in BACON.

Here we show how the sculpting made possible by juvenile and adult neurogenesis might influence dentate innervation. Sculpting leads to enriched innervation of DG by cortical cells that will actually be used to code events. Note that the notion that some EC cells go unused is a simplification made to facilitate the simulations of Figs. 4 and 5. We would expect the reality to be that most EC cells are used in any environment but that sculpting causes late-born cells to become innervated by combinations of EC cells that commonly fire together in a given environment

To clarify the logic behind the benefits of sculpting we consider in Fig. 4 a highly simplified case in which just two similar contexts, A and B, were encoded, and (artificially) small sets of EC and DG cells are imagined. This simulation illustrates that sculpting leads to (1) reduced representation overlap, (2) enriched ECin input to representation cells, and (3) improved recall accuracy.

Fig. 4. Effects of sculpting on context representations in BACON’s DG and CA3.

Graphs display the results of a simulation in which two similar contexts, A and B, were encoded. For simplicity, artificially small sets of EC and DG cells were used. There were 500 EC cells in all, and a given context (or event) was composed of just 6 of them, drawn randomly from a subset of 15 environmentally-relevant EC cells. Each DG cell received input from 10 EC cells. In the non-sculpted case the inputs were chosen randomly from the full set of 500 EC cells, whereas in the sculpted case they were chosen from the subset of 15 environmentally-relevant cells. Representations of each event were composed of the 10 DG cells (and their CA3 followers) that were most richly innervated by the event’s EC cells. After A and B were encoded, the virtual subject was tested with half of event A’s ECin cells active. Top Panel, Excitation of each of 100 DG neurons during encoding in A and B. For each context, the 10 most excited cells became incorporated into the representation. The minimal excitation level (threshold) for incorporation is shown by the broken line; the threshold for A was slightly below that for B, but so close that a single line was drawn. Representation cells are indicated by triangles. Sculpting results in considerably less overlap between the representations of A and B (Rep A and Rep B) and richer innervation by the events’ ECin cells. Bottom Panel, Excitation of CA3 neurons during recall in which a subset of event A’s ECin cells were active. Broken line represents the threshold for action potential firing. Prior to completion of a representation by the CA3 recurrent collateral network, there are substantially more Rep A than Rep B cells active in the sculpted than in the non-sculpted case. Therefore, completion of Rep A rather than B is much better ensured.

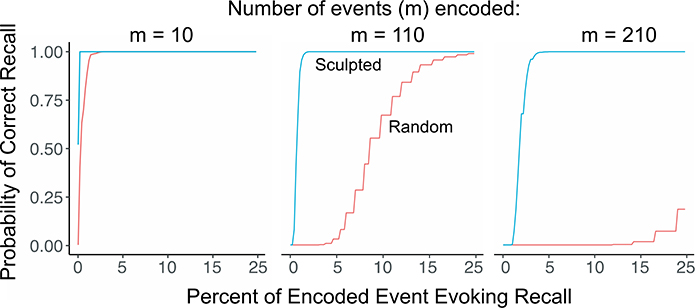

Then, using network parameters commonly assumed for the rat (O’Reilly and McClelland, 1994; Treves and Rolls, 1994), we applied similar logic to calculate the probability of correct recall (i.e., activation of the correct representation) when the circuit is presented with a fraction of the attributes of a stored event (or of a familiar context; Fig. 5). When few contexts or events have been learned, very little of the original needs to be observed for correct recall to occur reliably. However, as more and more contexts are learned, there are more and more representation cells competing to be the most excited, and therefore in both the sculpted and the non-sculpted cases, progressively more of the originally-observed attributes must be seen to ensure correct recall. Performance is always somewhat better in the sculpted than the non-sculpted case, but the advantage of sculpting becomes dramatic as memory load increases.

Fig. 5. Effects of sculpting in BACON simulations with rat-like parameters.

As the number of events encoded (M) increases, the number of event attributes needed for correct recall increases greatly in the random (non-sculpted) network but increases only slightly in the sculpted network. Calculations were performed as described under Fig. 2. It was assumed that 30% of an event’s 12,500 attributes were encoded and that attribute overlap of one event with another was 90%. Events were constructed by drawings at random from a set consisting of 7% of the total possible set of event attributes; in the sculpted case, DG cells were innervated only by the ECin cells coding this attribute set.

Possible mechanisms of sculpting

The goal of sculpting, as we propose it, is to increase the extent to which the limited number of EC cells that innervate each DG cell (about 4K out of 200K EC input cells in the rat (O’Reilly and McClelland, 1994; Squire et al, 1989)) are EC cells that are liable to be active in an animal’s adult living environment. Sculpting of this kind could presumably be achieved either by (1) experience-determined granule cell survival or (2) experience-determined innervation. In so far as both of these mechanisms operate most prominently, though not necessarily exclusively, in younger DG cells, sculpting to the adult environment would be facilitated by juvenile and adult neurogenesis, and we are proposing that this is a major reason for its existence. However, sculpting to the adult environment might also be facilitated by extending the cell age at which either of these processes occurs in developing granule cells, and there is no reason why both mechanisms could not occur together in individuals.

It has long been appreciated that juvenile and adult neurogenesis allows DG innervation to be sculpted via selective survival of newborn neurons (above mechanism 1) (Tashiro et al., 2006). Many new late-born granule cells die before reaching maturity, and their survival does depend, at least in part, on their receiving inputs from active EC inputs. The most direct evidence for this conclusion comes from Tashiro et al. (2006) who showed that knocking out NMDA receptors in a sparse subset of newborn GCs impairs the survival of those cells. This effect on survival was attenuated when NDMA receptors were blocked systemically via injection of an NMDA antagonist drug, suggesting that survival is a competitive process in which the cells most strongly innervated by active EC inputs survive, whereas those that fail to make synapses with active EC inputs die. Because of selective survival, ongoing neurogenesis should increase DG representation of active EC inputs. Consistent with this idea, Olariu et al (2005) found effects of experience on survival of young late-born cells. Possible extension of the period during which perinatally-born cells can be selected for survival is suggested by the observation that about 15% of granule cells born at P6 (though not earlier or later) die between 2 and 6 months of age (Cahill et al., 2017; Ciric et al., 2019) as opposed to very soon after their birth. However, we are aware of no evidence that experience determines which particular cells die at these later times.

Selective innervation (mechanism 2) might be the product of either selective initial establishment of synapses made by active EC cells or pruning of excess inputs that were inactive. There is evidence of both sorts of mechanisms operating during development in other parts of the brain (see Kirischuk et al., 2017; Yamamoto and López-Bendito, 2012 for reviews). Such data as is available for DG cannot distinguish between these alternatives, but there is suggestive evidence that the development of synaptic inputs is affected by experience. Tronel et al. (2010b) found that growth of dendritic arbors of young late-born granule cells was enhanced by water maze experience. This effect could, in theory, reflect learning about the details of a specific maze, but it occurred in cells less than two weeks old, which, at least by some accounts (Denny et al, 2012; Swan et al, 2014) are too young to participate in such learning. Therefore, we are inclined to conclude, in agreement with the study’s authors, that the dendritic growth reflects sculpting of the cells’ pattern of innervation. Kannangara et al. (2014) found dendritic growth of maturing neurons to be depressed in animals whose NMDA GluN2A receptors were deleted, suggesting that the growth requires active glutamatergic inputs. Dendritic growth has been observed even in older late-born cells (Lemaire et al, 2012), though not in older early-born ones, which may suggest a lengthening of the period during which mechanism 2 can operate in DG, at least in late-born cells. Cole et al. (2020) have also reported substantial signs of dendritic growth in late-born but not early-born 7–24 week-old cells, though there was no evidence that this growth was experience-driven. More direct evidence that innervation of late-born granule cells can be modified by experience is provided by experiments using viral labeling of synaptic inputs (Bergami et al., 2015; Vivar et al., 2016). Bergami et al (2015) mapped the presynaptic inputs to granule cells using rabies virus trans-synaptic tracing. Exposure to running or enriched environment dramatically altered the pattern of intra- and extra-hippocampal inputs onto late-born neurons that were 3 to 6 weeks of age at the time of the exposure. The connectivity of fully mature (12–13-week-old) cells was not altered by the exposures. Thus, the rather scant information available provides some evidence suggesting that sculpting by experience-determined growth in both young and older late-born DG cells but not in mature early-born ones. However, it should be noted that there is considerable evidence that at least some amount of dendritic plasticity can occur in early-born cells throughout the brain, including the DG (Greenough, 1985; Kolb, 2003, Marrone 2005; Comeau 2010; Kolb 2015; Gisabella 2020; Villanueva Espino, 2020). Thus, it seems entirely possible that further work will show that sculpting of early-born DG cells may occur to some extent even in the more mature animals.

In summary, the limited information currently available provides evidence that sculpting of the DG could be achieved via both experience-directed cell elimination/survival and experience-directed innervation. Sculpting specifically to the adult environment is facilitated both by having new granule cells continue to be born as animals become familiar with their adult environments and also by extending the cell-age at which sculpting by these mechanisms occurs. Given the paucity of information available, it seems possible that mechanisms such as synaptic pruning and prolonged ability to be sculpted may eventually be found to operate even in perinatally-born granule cells, as has been observed in other brain regions. If so, we speculate that the existence of late neurogenesis would nevertheless enhance the capacity for sculpting beyond what would be possible in its absence.

Predictions

If, as we hypothesize, juvenile and adult neurogenesis enables sculpting of DG such that DG becomes preferentially innervated by environmentally-relevant collections of EC cells, then exposure to particular elementary stimuli during an animal’s postnatal development should have several consequences with respect to later storage and recall of events involving those stimuli.

Specifically, we predict that if an animal is repeatedly exposed during postnatal development to stimuli composed of certain elementary features:

Granule cells that were maturing at the time of exposure should become preferentially responsive to stimuli having those elementary features and, therefore, should be preferentially, though not exclusively, incorporated into new representations involving those features.

Hippocampal representations of events (or complex stimuli) composed of the pre-exposed features will have less overlap with one another than representations of stimuli composed of non-pre-exposed features.

-

The animal will have an enhanced ability to learn, correctly recall, and discriminate stimuli composed of the pre-exposed elementary stimuli.

We predict that effects 2–3 should require that neurogenesis was occurring—and, as a consequence, granule cells were developing—during the period of stimulus pre-exposure. By inference, appropriately-timed suppression of juvenile and adult neurogenesis by experimental or natural means (e.g. aging, stress) should prevent these effects of stimulus pre-exposure. Finally, we predict:

To the extent that the function of extended neurogenesis is to adapt the hippocampus to the particulars of an animal’s environment, then significant changes to the environment or exposure in adulthood to events and situations whose elementary features are novel might be expected to stimulate neurogenesis or increase survival of new cells and renew the capacity for sculpting.

Evidence

The idea that granule cells should become tuned to stimuli experienced while the cells were maturing (Prediction 1) has a long history (Kee et al., 2007; Stone et al., 2011; Tashiro et al., 2007). To test this and most of our other predictions, one would like to see experiments in which a population of late-born cells are labeled (e.g., with BrdU), and, during the maturation of the cells, the animals are given extensive exposure to situations having particular elementary features. Then, once the labeled cohort of neurons had reached maturity, animals should be exposed to events (or stimulus configurations) involving the pre-exposed features. Behavioral testing and recording / imaging of neural activity should be used to assess (1) the animal’s ability to recall the events/stimulus configurations accurately and (2) the extent to which the resulting representations were composed of labeled cells.

It is important to note that we make a distinction between sculpting and memory formation. According to our hypothesis, sculpting establishes a set of cells tuned to particular features of an animal’s environment. These cells can then be incorporated into memory representations involving those features. But there is no requirement that the tuned cells be part of the memory for the specific event that caused the sculpting. Indeed, hippocampal memories are thought to be created very rapidly, perhaps faster than the process of sculpting. Moreover, cells in the process of being sculpted might be prevented from becoming part of a memory representation, because the loss and gain of synapses during sculpting might render cells too unstable for recruitment into a memory. To distinguish experimentally between sculpting and memory formation, animals should be pre-exposed during DG granule cell development to simple stimuli that will later be combined in arbitrary ways to generate configural stimuli for which animals will have to create new representations. One interesting approach would be to use direct electrical or optogenetic stimulation of specific entorhinal cells to generate elementary stimuli and combinations of them. The behavioral effects of pre-exposure could conveniently be evaluated by using the configural stimuli to which representations were made as CS+ and CS− in conditioning experiments, while cell activity could be assessed using IEG responses or, better, Ca++ imaging.

To our knowledge, experiments testing the role of neurogenesis in sculpting per se—as defined above and as distinct from memory formation—have not been conducted. However, attempts have been made to compare incorporation of early- versus late-born cells into new representations. These experiments have typically exposed animals to a novel situation of which they would be expected to form a representation, such as a water maze, enriched environment, or a context in which animals were shocked, and later animals were re-exposed to the same situation and immediate-early gene (usually cFos) responses were evaluated to determine which cells had become part of the representation and hence were activated. In such experiments we would predict that late-born cells would be at a modest advantage for getting incorporated into the new representations, because they would have become sculpted to the elementary aspects of the general adult lab environment, if not also to the elementary attributes particular to the task that was used. Early-born cells, on the other hand, would either be randomly innervated or sculpted to the pre-weaning environment. It is important to point out that the sculpting-mediated advantage of late-born cells that we are proposing here is distinct from the hypothesized advantage that generally motivated these prior studies, which posited that immature, late-born cells were more likely to be incorporated into any new representation, by virtue of their enhanced excitability and/or plasticity (Ge et al, 2007). Several such studies compared labeled late-born cells to the granule cell population as a whole, which would include a mix of perinatally-born cells and late-born ones. Kee et al, 2007 (two experiments) and Stone et al, 2011 (one experiment) found that mature labeled late-born cells were more likely to show cFos responses than was the general granule cell population, which is what we would predict if sculpting to the post-weaning environment confers an advantage. However, it has been pointed out (Stone et al., 2011) that very young cells do not show cFos responses; therefore, if there were sufficient newborn cells at the time cFos was measured (about 3 months of age), late-born cells might show cFos responses more than the general population, not because late-born cells are more likely to become incorporated into representations, but rather because some of the cells of the general population are too young to do so. To avoid this complication, several experiments compared labeled perinatally-born and labeled late-born cells (Stone et al., 2011). In each of these experiments, there was a slight trend favoring late-born cells, but the differences always fell quite short of statistical significance. Thus, while there are some experiments that may be taken to suggest that late-born cells are at an advantage in terms of representation formation, overall the literature does not provide clear support for this prediction of the sculpting hypothesis.

Why were sculpting effects not consistently observed in these experiments? Sculpting can influence which cells become part of the representation of a situation only in so far as the cells have become sculpted to the elementary features of the situation prior to its first being encountered. When the animals in these studies were first exposed to the water maze, for example, the late-born cells would have been at some advantage for inclusion in the to-be-formed representation mainly because they would have become sculpted to animal’s post-weaning living environment—the vivarium, home cage, handling cues, etc.—whereas the perinatally born cell probably would not. But these attributes are but a small portion of those of the overall maze situation, and, therefore, sculpting to them might only confer a small advantage. Moreover, because neurogenesis was ongoing both before and after the time of BrdU labeling, many non-labeled late-born cells would have become sculpted to these same features of the general living environment; therefore, only a small fraction of advantageously sculpted cells would be labeled ones. These factors would tend to decrease the extent to which labeled adult-born cells would be preferentially activated by the relevant experimental manipulations. For these reasons, we argue that the literature does not yet provide a strong test of the prediction that late-born cells should be at an advantage for inclusion in new representations in the manner predicted by the sculpting hypothesis.

A number of other experiments have evaluated how manipulations of juvenile and adult neurogenesis affect representation overlap or discrimination learning ability (Predictions 2 and 3). According to the sculpting hypothesis, suppression of neurogenesis should increase the overlap among representations of similar contexts (Prediction 2). Nibori et al. (2012) used the catFISH technique to determine the overlap between representations of two different contexts to which the animals had been exposed. As we would expect if sculpting had been occurring, suppression of adult neurogenesis increased overlap when the contexts were similar, though not when they were quite different.

The effect of neurogenesis on discrimination learning (Prediction 3 has been evaluated in a number of studies focusing on “behavioral pattern separation” (for review see França et al., 2017). For instance, in the contextual discrimination paradigm mice receive alternating exposures to two similar conditioning chambers, with footshocks administered in one chamber but not the other. Over time, mice acquire the discrimination and exhibit more freezing in the shock chamber than the safe one. Suppression of neurogenesis typically impairs performance in discrimination tasks like these (Nakashiba et al., 2012; Sahay et al., 2011; Tronel et al., 2010a, see Franca et al., 2017 for review). As illustrated in Fig. 4, we would expect that when representations have been created from a set of well-sculpted DG cells, the representations of two similar contexts will overlap less and be more richly innervated than would otherwise be the case. Consequently, with sculpting, there will be fewer errors in which of the two representations is activated, resulting in better differentiation of behavioral responses. Increased accuracy of representation activation would also diminish the chances that the safe context representation would be active in the shock-paired context and get reinforced, which, if it were to happen, would greatly hurt discrimination learning.

There have also been several experiments in which simple generalization of context fear to a similar context has been evaluated. In one of these, animals had been pre-familiarized to two contexts, A and B, prior to fear conditioning context A. In that case, as predicted above, suppressing adult neurogenesis for an extended period prior to the experiment increased generalization of context fear from A to B (Niibori et al., 2012). However, in the several other experiments context B was unfamiliar at the time of the generalization test (Huckleberry et al., 2018; Lemaire et al., 2012; Nakashiba et al., 2012; Sahay et al., 2011). In these studies, suppression of juvenile and adult neurogenesis failed to increase context fear generalization. Our previous BACON simulations (Bernier et al., 2017; Krasne et al., 2015) suggest a possible explanation for why suppression of neurogenesis impairs generalization when the tested context is familiar but not when it is novel. At the start of a generalization test in a novel context B, hippocampus will not yet have created a representation for context B. As a result, any fear expression that occurs will be driven, at least initially, by incorrect activation of the context A representation. Discriminative responding will occur only after the animal has determined that it is not in Context A and it has generated a distinct context B representation. If, as we suspect, neurogenesis-based sculpting has only a modest impact on these processes of context recognition and representation formation, then suppression of neurogenesis would have less of an effect on generalization to a novel context than on generalization to a familiar context. However, because it is difficult to determine whether or when a representation of context B is created in vivo, this account remains speculative. There is also a second factor that may render multi-session discrimination training experiments more sensitive to neurogenesis disruption than tests of spontaneous generalization. Given the extended nature of the training in context discrimination experiments, it is possible that some sculpting might occur during the experiment itself to attributes of the contexts. Neurogenesis-based sculpting would enrich input to representation cells from ECin cells that code an event/context’s attributes and thereby facilitate activation of the correct representation in each context, which would speed development of good discriminative responding.

Possible evidence for Prediction 4, which states that neurogenesis should adaptively increase in response to novel experiences to re-enable sculpting, comes from the findings that behavioral experiences that might, in nature, signal the presence of novelty can modulate proliferation of DG progenitors and promote survival and incorporation of late-born cells into hippocampal circuitry. Voluntary exercise stimulates proliferation (van Praag et al., 1999), as does participating in hippocampus-dependent memory tasks, at least in some cases (Dalla et al., 2007; Gould et al., 1999; Waddell et al., 2011). Environmental enrichment and participation in memory tasks also promote survival of new-born cells (Kempermann et al., 1997; Olson et al., 2006; Tashiro et al., 2007). From our perspective, changes in proliferation and increased survival of very immature (less the 3 weeks) new-born cells could be a mechanism through which sculpting is modulated in correspondence with information processing demands.

It should be noted that the effects of hippocampus-dependent learning tasks on survival of late-born neurons are mixed, with some studies showing that learning enhances survival (Gould et al., 1999; Waddell et al., 2011) and other studies showing no effect (Snyder et al., 2012). We wish to emphasize that the sculpting hypothesis is agnostic about whether learning should increase the net number of surviving cells. This is because, first, the sculpting hypothesis does not require that animals participate in a learning task for sculpting to occur; sculpting is caused by experience, not by learning per se; this means that control treatments, such as apparatus exposure, might influence neuronal survival in the same way as learning. Second, according to the sculpting hypothesis, the major effect of behavioral experience is to determine which cells survive, not the net number that survive. Thus, sculpting could be occurring even if a given experience fails to increase the net number of newborn neurons that survive.

Discussion and Implications

We feel that the environmental sculpting hypothesis provides a framework to account for many outstanding questions regarding the functional significance of juvenile and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. The sculpting hypothesis posits that the function of juvenile and adult neurogenesis is primarily prospective: It prepares the hippocampus to represent the subset of multisensory space that the animal is likely to encounter in its local environment. Conceptually, the juvenile / early-adult period of high neurogenesis can be viewed as a “mnemonic” critical period wherein experience serves to specialize the multisensory inputs to the hippocampus after the closure of the early developmental critical periods for primary sensory areas. This specialized dentate is then able to store a larger number of discriminable memory representations within the animal’s local environment.

The prediction that prior exposure to stimuli should enhance later memory for events or other percepts involving those stimuli may seem counterintuitive given that novelty often enhances learning, whereas familiarity produces latent inhibition, which is an impairment of learning. However, there are situations in which prior exposure enhances memory, particularly when the learning involves complex stimuli that are likely to recruit hippocampal processing. Whereas pre-exposure to simple sensory stimuli produces latent inhibition of fear conditioning to simple cues, in hippocampus-dependent contextual fear conditioning, pre-exposure to the conditioning context enhances subsequent conditioning (Biedenkapp and Rudy, 2007; Fanselow, 1990; Zinn et al., 2020). In humans, experts display enhanced memory for domain-specific information as compared to non-experts (Vicente and Wang, 1998). In conditioning studies, although stimulus pre-exposure reduces associativity, it can also enhance the ability of subjects to discriminate among the pre-exposed stimuli (e.g., Mclaren and Mackintosh, 2000). We do not propose that sculpting of DG inputs explains all of these effects; we cite these examples merely to illustrate that the pre-exposure effects predicted by the sculpting hypothesis are compatible with existing evidence.

The sculpting hypothesis is also compatible with other theoretical accounts of neurogenesis. For example, the memory clearance hypothesis for postnatal neurogenesis (and its associated phenomenon of infantile amnesia) can be viewed as a consequence of sculpting, whereby large numbers of new neurons added in the early postnatal period specialize the dentate network, but this large addition disrupts long term retention/retrieval of previously acquired memories. Thus, network specialization outweighs long-term memory early in life but, eventually, as the number of new neurons drops, the network shifts to long-term memory stability at the expense of further specialization. The enhancement of forgetting by the running wheel-mediated increase in neurogenesis can be seen as an adaptive consequence: large amounts of running would normally indicate that an animal is entering a new environment, and, therefore, a new round of sculpting may be warranted. By the same token, actually entering a new living environment should also produce an increase in sculptability. Indeed, exposure to an enriched environment enhances survival of newborn granule cells (Fabel et al., 2009; Meshi et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2006; Tashiro et al., 2007). The effect of enrichment on survival could, in part, reflect sculpting itself, but it likely also reflects an enhancement in the survival of very young neuroblasts that it is driven by general network activity rather than specific sensory inputs.

Overall, this framework may provide important insights into the translational significance of juvenile and adult neurogenesis in humans and clinical disorders associated with the disruption of neurogenesis (for review see Yun et al., 2016). Some theories propose that impaired neurogenesis leads to a disrupted capacity to distinguish safe from unsafe situations, which leads to overly generalized fears and impaired coping ability (Kheirbek et al., 2012). The sculpting hypothesis provides a novel perspective from which to view sensitive periods of vulnerability to factors that may disrupt neurogenesis, such as stress, inflammation, drugs and environmental exposures, as well as the time-course of when deficits would manifest (Dinel et al., 2014; Kozareva et al., 2019; Lagace et al., 2006; Loi et al., 2014; Snyder, 2019). Disruption of the sculpting process during the juvenile and adolescent periods would produce an adult dentate gyrus that is insufficiently specialized, mis-specialized or, potentially, over-specialized. Owing to the prospective nature of sculpting effects, cognitive and neuropsychiatric impairments may not become evident until sometime after sculpting itself has occurred, perhaps explaining why psychiatric conditions typically manifest in the transition to adulthood (McGorry, 2011). Conversely, treatments that stimulate neurogenesis in adults, such as antidepressant drugs or exercise, might improve outcomes not because of a direct effect of newborn neurons on mood and related psychological processes, but because increased neurogenesis allows re-sculpting of innervation. Such an account may explain why antidepressant drugs more effectively treat depression and other conditions when combined with psychotherapy (Cuijpers et al., 2014) as well as the greater efficacy of physical exercise combined with mental training (Millon and Shors, 2019). Furthermore, the current controversy over whether postnatal neurogenesis extends beyond the juvenile period in humans gains greater clarity with the environmental sculpting hypothesis. If the main function of extended neurogenesis is to sculpt dentate connectivity to the animal’s environment, then its decline in adulthood is not unexpected.

The sculpting hypothesis might also provide insight into the function of cross-species variation in postnatal neurogenesis. Extended postnatal neurogenesis is common among many, if not, all mammalian species, but the levels vary considerably (Amrein, 2015; Amrein et al., 2007, 2004; van Dijk et al., 2019; Wiget et al., 2017). The sculpting hypothesis predicts that higher levels of juvenile and adult neurogenesis should enhance the ability of an individual to adapt hippocampal processing to the specifics of its environmental milieu. If so, then it might be the case that species with higher juvenile and adult neurogenesis are better able to adapt to a variety of environments, broadly defined, than are those with low levels of neurogenesis. For instance, high-neurogenesis species may be those that can be found in diverse habitats, known as generalist species, whereas low-PNN species may be more likely to be confined to a single habitat, known as specialist species. Neurogenesis-based sculpting might facilitate cognitive processes that support adaptability, such as behavioral innovation (Sol et al., 2016).

As we have discussed above, the sculpting hypothesis raises several major questions that will require further research. One pertains to where neurogenesis-based sculpting fits within the larger domain of neuroplasticity. In many brain regions, early-born and fully mature neurons retain the capacity for various types of plasticity—such as synaptic strengthening and weakening, dendritic remodeling and new synapse formation (Comeau et al., 2010; Gisabella et al., 2020; Greenough et al., 1985b, 1985a; Kolb et al., 2003; Marrone, 2005). We have presented some ideas about how neurogenesis might enable experience-dependent modifications to innervation, but it remains unknown to what extent non-neurogenic mechanisms might mediate these same modifications. Another important question pertains to the development and innervation of early- versus late-born granule cells. We predict that late-born granule cells are more likely to become sculpted to the postnatal environment than early-born granule cells. But the extent to which early-born cells might themselves become sculpted is unknown. We speculate that at least some early-born cells are innervated in an experience-independent way, owing perhaps to correlated network phenomena in the developing brain (Pedroni et al., 2014). Other early-born cells might be able to become sculpted to the postnatal environment even though their initial period of innervation is long past. Additional research is needed to understand the development of granule cell innervation and how it might differ between early- and late-born cells.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we feel that the sculpting hypothesis provides a highly plausible explanation for the existence of juvenile and adult neurogenesis. By expanding upon established computational frameworks, the hypothesis provides a direct explanation for why juvenile and adult neurogenesis occurs specifically within the DG. Furthermore, the hypothesis can account for many phenomena that are not readily explained by current models, particularly the large decline in rates of neurogenesis in adult animals and humans. The sculpting hypothesis makes several experimentally-testable predictions; however key experiments required to directly test the sculpting hypothesis have not yet been performed.

Highlights.

We propose that postnatal neurogenesis allows behavioral experience to sculpt dentate connectivity.

Dentate cells become preferentially innervated by environmentally-relevant neocortical input.

Simulations demonstrate that such sculpting can greatly increase storage capacity

Sculpting is needed while animals are becoming familiar with their environment

This explains why neurogenesis declines as animals mature.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and by NIH R01 MH102595 and R01 MH117426 to M.R.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aimone JB, Deng W, Gage FH, 2011. Resolving New Memories: A Critical Look at the Dentate Gyrus, Adult Neurogenesis, and Pattern Separation. Neuron 70, 589–596. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, Yiu AP, De Cristofaro A, Hsiang H-LL, Wheeler AL, Guskjolen A, Niibori Y, Shoji H, Ohira K, Richards B. a, Miyakawa T, Josselyn S. a, Frankland PW, 2014. Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science 344, 598–602. 10.1126/science.1248903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD, 1965. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol 124, 319–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrein I, 2015. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in natural populations of mammals. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 7, 1–20. 10.1101/cshperspect.a021295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrein I, Dechmann DKN, Winter Y, Lipp HP, 2007. Absent or low rate of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus of bats (Chiroptera). PLoS One 2, 1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrein I, Slomianka L, Poletaeva II, Bologova NV, Lipp HP, 2004. Marked species and age-dependent differences in cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of wild-living rodents. Hippocampus 14, 1000–1010. 10.1002/hipo.20018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade JP, Lukoyanov NV, Paula-Barbosa MM, 2002. Chronic food restriction is associated with subtle dendritic alterations in granule cells of the rat hippocampal formation. Hippocampus 12, 149–164. 10.1002/hipo.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergami M, Masserdotti G, Temprana SG, Motori E, Eriksson TM, Göbel J, Yang SM, Conzelmann K-K, Schinder AF, Götz M, Berninger B, 2015. A Critical Period for Experience-Dependent Remodeling of Adult-Born Neuron Connectivity. Neuron 1–8. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann O, Spalding KL, Frise J, 2015. Adult Neurogenesis in Humans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 7, 1–12. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier BE, Lacagnina AF, Ayoub A, Shue F, Zemelman BV, Krasne FB, Drew MR, 2017. Dentate Gyrus Contributes to Retrieval as well as Encoding: Evidence from Context Fear Conditioning, Recall, and Extinction. J. Neurosci 37, 6359–6371. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3029-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedenkapp JC, Rudy JW, 2007. Context preexposure prevents forgetting of a contextual fear memory: implication for regional changes in brain activation patterns associated with recent and remote memory tests. Learn. Mem 14, 200–203. 10.1101/lm.499407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Yu RQ, Green D, Todorova EV, Snyder JS, 2017. Early survival and delayed death of developmentally-born dentate gyrus neurons. Hippocampus 27, 1155–1167. 10.1002/hipo.22760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron H. a, McKay RD, 2001. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol 435, 406–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Schoenfeld TJ, 2018. Behavioral and structural adaptations to stress. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49, 106–113. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvet CJ, Finlay BL, 2018. Comparing adult hippocampal neurogenesis across species: Translating time to predict the tempo in humans. Front. Neurosci 12, 1–18. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciric T, Cahill SP, Snyder JS, 2019. Dentate gyrus neurons that are born at the peak of development, but not before or after, die in adulthood. Brain Behav 9, 1–6. 10.1002/brb3.1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clelland CD, Choi M, Romberg C, Clemenson GD, Fragniere A, Tyers P, Jessberger S, Saksida LM, Barker RA, Gage FH, Bussey TJ, 2009. A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science (80-. ). 325, 210–213. 10.1126/science.1173215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JD, Espinueva DF, Seib DR, Ash AM, Cooke MB, Cahill SP, O’Leary TP, Kwan SS, Snyder JS, 2020. Adult-Born Hippocampal Neurons Undergo Extended Development and Are Morphologically Distinct from Neonatally-Born Neurons. J. Neurosci 40, 5740–5756. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1665-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau WL, McDonald RJ, Kolb BE, 2010. Learning-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology. Behav. Brain Res 214, 91–101. 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, Andersson G, Beekman AT, Reynolds CF, 2014. Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 13, 56–67. 10.1002/wps.20089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman JD, Maldonado J, Kwon EE, Garcia a D., Fan G, Imura T, Sofroniew MV, Fanselow MS, 2012. Juvenile neurogenesis makes essential contributions to adult brain structure and plays a sex-dependent role in fear memories. Front. Behav. Neurosci 6, 3. 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, Bangasser D. a, Edgecomb C, Shors TJ, 2007. Neurogenesis and learning: acquisition and asymptotic performance predict how many new cells survive in the hippocampus. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 88, 143–8. 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCostanzo AJ, Fung CCA, Fukai T, 2019. Hippocampal Neurogenesis Reduces the Dimensionality of Sparsely Coded Representations to Enhance Memory Encoding. Front. Comput. Neurosci 12, 99. 10.3389/fncom.2018.00099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Aimone JB, Gage FH, 2010. New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci 11, 339–50. 10.1038/nrn2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinel A-L, Joffre C, Trifilieff P, Aubert A, Foury A, Le Ruyet P, Layé S, 2014. Inflammation early in life is a vulnerability factor for emotional behavior at adolescence and for lipopolysaccharide-induced spatial memory and neurogenesis alteration at adulthood. J. Neuroinflammation 11, 155. 10.1186/s12974-014-0155-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eadie BD, Redila VA, Christie BR, 2005. Voluntary exercise alters the cytoarchitecture of the adult dentate gyrus by increasing cellular proliferation, dendritic complexity, and spine density. J. Comp. Neurol 486, 39–47. 10.1002/cne.20493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas JM, Michurina TV, Peunova N, Park JH, Tordo J, Peterson DA, Fishell G, Koulakov A, Enikolopov G, 2011. Division-coupled astrocytic differentiation and age-related depletion of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell 8, 566–579. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, 1990. Factors governing one-trial contextual conditioning. Anim. Learn. Behav 18, 264–270. 10.3758/BF03205285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- França TFA, Bitencourt AM, Maximilla NR, Monserrat M, Barros DM, 2017. Hippocampal neurogenesis and pattern separation : A meta-analysis of behavioral data 937–950. 10.1002/hipo.22746 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Frankland PW, Ko S, Josselyn SA, 2013. Hippocampal neurogenesis and forgetting 497–503. 10.1016/j.tins.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gisabella B, Scammell T, Bandaru SS, Saper CB, 2020. Regulation of hippocampal dendritic spines following sleep deprivation. J. Comp. Neurol 528, 380–388. 10.1002/cne.24764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasper ER, Schoenfeld TJ, Gould E, 2012. Adult neurogenesis: Optimizing hippocampal function to suit the environment. Behav. Brain Res 227, 380–383. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Beylin A, Tanapat P, Reeves A, Shors J T, 1999. Learning enhances adult neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci 2, 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough WT, Hwang HMF, Gorman C, 1985a. Evidence for active synapse formation or altered postsynaptic metabolism in visual cortex of rats reared in complex environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 82, 4549–4552. 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough WT, Larson JR, Withers GS, 1985b. Effects of unilateral and bilateral training in a reaching task on dendritic branching of neurons in the rat motor-sensory forelimb cortex. Behav. Neural Biol. 44, 301–314. 10.1016/S0163-1047(85)90310-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, 1995. Neuromodulation and cortical function: modeling the physiological basis of behavior. Behav. Brain Res 67, 1–27. 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00113-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckleberry KA, Shue F, Copeland T, Chitwood RA, Yin W, Drew MR, 2018. Dorsal and ventral hippocampal adult-born neurons contribute to context fear memory. Neuropsychopharmacology 1–10. 10.1038/s41386-018-0109-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee N, Teixeira CM, Wang AH, Frankland PW, 2007. Preferential incorporation of adult-generated granule cells into spatial memory networks in the dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci 10, 355–62. 10.1038/nn1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Gage FH, Aigner L, Song H, Curtis MA, Thuret S, Kuhn HG, Jessberger S, Frankland PW, Cameron HA, Gould E, Hen R, Abrous DN, Toni N, Schinder AF, Zhao X, Lucassen PJ, Frisén J, 2018. Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions. Cell Stem Cell 23, 25–30. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek MA, Klemenhagen KC, Sahay A, Hen R, 2012. Neurogenesis and generalization: a new approach to stratify and treat anxiety disorders. Nat. Neurosci 15, 1613–1620. 10.1038/nn.3262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirischuk S, Sinning A, Blanquie O, Yang JW, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W, 2017. Modulation of neocortical development by early neuronal activity: Physiology and pathophysiology. Front. Cell. Neurosci 11, 1–21. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Inokuchi K, 2014. Role of adult neurogenesis in hippocampal-cortical memory consolidation. Mol. Brain 7, 13. 10.1186/1756-6606-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Gibb R, Gorny G, 2003. Experience-dependent changes in dendritic arbor and spine density in neocortex vary qualitatively with age and sex. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 79, 1–10. 10.1016/S1074-7427(02)00021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozareva DA, Cryan JF, Nolan YM, 2019. Born this way : Hippocampal neurogenesis across the lifespan 1–18. 10.1111/acel.13007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krasne F, Cushman JD, Fanselow M, 2015. A Bayesian Context Fear Learning Algorithm/Automaton 9, 1–22. 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagace DC, Yee JK, Bolaños CA, Eisch AJ, 2006. Juvenile Administration of Methylphenidate Attenuates Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 1121–1130. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire V, Tronel S, Fabre A, Dugast E, Montaron M-F, Abrous DN, 2012. Long-Lasting Plasticity of Hippocampal Adult-Born Neurons. J. Neurosci 32, 3101–3108. 10.1523/jneurosci.4731-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi M, Koricka S, Lucassen PJ, Joëls M, 2014. Age- and Sex-Dependent Effects of Early Life Stress on Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 5, 13. 10.3389/fendo.2014.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D, 1971. Simple memory: a theory for archicortex. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci 262, 23–81. 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone DF, 2005. The morphology of bi-directional experience-dependent cortical plasticity: A meta-analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 50, 100–113. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland JL, Goddard NH, 1996. Considerations arising from a complementary learning systems perspective on hippocampus and neocortex. Hippocampus 6, 654–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland JL, McNaughton BL, O’Reilly RC, 1995. Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: Insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychol. Rev 102, 419–457. 10.1007/978-3-642-11202-7_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, 2011. Transition to adulthood: The critical period for pre-emptive, disease-modifying care for schizophrenia and related disorders. Schizophr. Bull 37, 524–530. 10.1093/schbul/sbr027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaren PL, Mackintosh NJ, 2000. An elemental model ofassociative learning: I. Latent inhibition and perceptual learning. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Morris RGM, 1987. Hippocampal synaptic enhancement and information storage within a distributed memory system. Trends Neurosci 10, 408–415. 10.1016/0166-2236(87)90011-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Sahay A, 2019. Functions of adult-born neurons in hippocampal memory interference and indexing. Nat. Neurosci 22, 1565–1575. 10.1038/s41593-019-0484-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millon EM, Shors TJ, 2019. Taking neurogenesis out of the lab and into the world with MAP Train My Brain™. Behav. Brain Res 376, 112154. 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez EP, Flor-García M, Terreros-Roncal J, Rábano A, Cafini F, Pallas-Bazarra N, Ávila J, Llorens-Martín M, 2019. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med 25, 554–560. 10.1038/s41591-019-0375-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashiba T, Cushman JD, Pelkey K. a, Renaudineau S, Buhl DL, McHugh TJ, Rodriguez Barrera V, Chittajallu R, Iwamoto KS, McBain CJ, Fanselow MS, Tonegawa S, 2012. Young dentate granule cells mediate pattern separation, whereas old granule cells facilitate pattern completion. Cell 149, 188–201. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niibori Y, Yu T-S, Epp JR, Akers KG, Josselyn S. a, Frankland PW, 2012. Suppression of adult neurogenesis impairs population coding of similar contexts in hippocampal CA3 region. Nat. Commun 3, 1253. 10.1038/ncomms2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly RC, McClelland JL, 1994. Hippocampal conjunctive encoding, storage, and recall: Avoiding a trade-off. Hippocampus 4, 661–682. 10.1002/hipo.450040605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson AK, Eadie BD, Ernst C, Christie BR, 2006. Environmental enrichment and voluntary exercise massively increase neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus via dissociable pathways. Hippocampus 16, 250–260. 10.1002/hipo.20157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroni A, Minh DD, Mallamaci A, Cherubini E, 2014. Electrophysiological characterization of granule cells in the dentate gyrus immediately after birth. Front. Cell. Neurosci 8, 44. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatti VC, Davies-Sala MG, Espósito MS, Mongiat LA, Trinchero MF, Schinder AF, 2011. The timing for neuronal maturation in the adult hippocampus is modulated by local network activity. J. Neurosci 31, 7715–7728. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1380-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redila VA, Christie BR, 2006. Exercise-induced changes in dendritic structure and complexity in the adult hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuroscience 137, 1299–1307. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A, Scobie KN, Hill AS, O’Carroll CM, Kheirbek M. a, Burghardt NS, Fenton A. a, Dranovsky A, Hen R, 2011. Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to improve pattern separation. Nature 472, 466–70. 10.1038/nature09817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville WB, Milner B, 1957. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci 12, 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JS, 2019. Recalibrating the Relevance of Adult Neurogenesis. Trends Neurosci 42, 164–178. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JS, 2018. Recalibrating the Relevance of Adult Neurogenesis. Trends Neurosci 0, 1–15. 10.1016/J.TINS.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JS, Clifford MA, Jeurling SI, Cameron HA, 2012. Complementary activation of hippocampal-cortical subregions and immature neurons following chronic training in single and multiple context versions of the water maze. Behav. Brain Res 227, 330–339. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sol D, Sayol F, Ducatez S, Lefebvre L, 2016. The life-history basis of behavioural innovations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 371. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrells SF, Paredes MF, Cebrian-Silla A, Sandoval K, Qi D, Kelley KW, James D, Mayer S, Chang J, Auguste KI, Chang EF, Gutierrez AJ, Kriegstein AR, Mathern GW, Oldham MC, Huang EJ, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yang Z, Alvarez-Buylla A, 2018. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 555, 377–381. 10.1038/nature25975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, 2004. Memory systems of the brain: a brief history and current perspective. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 82, 171–7. 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SSD, Teixeira CM, Zaslavsky K, Wheeler AL, Martinez-Canabal A, Wang AH, Sakaguchi M, Lozano AM, Frankland PW, 2011. Functional convergence of developmentally and adult-generated granule cells in dentate gyrus circuits supporting hippocampus-dependent memory. Hippocampus 21, 1348–1362. 10.1002/hipo.20845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Makino H, Gage FH, 2007. Experience-specific functional modification of the dentate gyrus through adult neurogenesis: a critical period during an immature stage. J. Neurosci 27, 3252–9. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4941-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH, 2006. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature 442, 929–33. 10.1038/nature05028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toni N, Schinder AF, 2016. Maturation and functional integration of new granule cells into the adult hippocampus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 8. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treves A, Rolls ET, 1994. Computational analysis of the role of the hippocampus in memory. Hippocampus 4, 374–391. 10.1002/hipo.450040319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinchero MF, Buttner KA, Sulkes Cuevas JN, Temprana SG, Fontanet PA, Monzón-Salinas MC, Ledda F, Paratcha G, Schinder AF, 2017. High Plasticity of New Granule Cells in the Aging Hippocampus. Cell Rep. 21, 1129–1139. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronel S, Belnoue L, Grosjean N, Revest J-M, Piazza P-V, Koehl M, Abrous DN, 2010a. Adult-born neurons are necessary for extended contextual discrimination. Hippocampus 000. 10.1002/hipo.20895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]