Abstract

Background:

The effects of non-physiologic flow generated by continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (CF-LVADs) on the aorta remain poorly understood.

Objectives:

We sought to quantify indices of fibrosis and determine the molecular signature of post-CF-LVAD vascular remodeling.

Methods:

Paired aortic tissue was collected at CF-LVAD implant and subsequently at transplant from 22 patients. Aortic wall morphometry and fibrillar collagen content (a measure of fibrosis) was quantified. In addition, whole-transcriptome profiling by RNA-sequencing and follow-up immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate CF-LVAD-mediated changes in aortic mRNA and protein expression.

Results:

The mean age was 52±12 years, with a mean duration of CF-LVAD of 224±193 (range 45–798) days. There was a significant increase in the thickness of the collagen-rich adventitial layer from 218±110μm Pre-LVAD to 410±209μm Post-LVAD (p<0.01). Furthermore, there was an increase in intimal and medial mean fibrillar collagen intensity from 22±11a.u. Pre-LVAD to 41±24a.u. Post-LVAD (p<0.0001). The magnitude of this increase in fibrosis was greater among patients with longer durations of CF-LVAD support. CF-LVAD led to profound downregulation in expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase-19 (MMP-19) and ADAMTS4, while no evidence of fibroblast activation was noted.

Conclusions:

There is aortic remodeling and fibrosis after CF-LVAD that correlates with the duration of support. This fibrosis is due, at least in part, to suppression of ECM-degrading enzyme expression. Further research is needed to examine the contribution of non-physiologic flow patterns on vascular function and whether modulation of pulsatility may improve vascular remodeling and long-term outcomes.

Keywords: left ventricular assist device, mechanical circulatory support, vascular remodeling, congestive heart failure, aorta, fibrosis

Condensed Abstract

The effects of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (CF-LVADs) on the aorta are unknown. Paired aortic tissue was collected before and after LVAD. Fibrosis was quantified with microscopy, stiffness was measured from stress-strain testing, and the molecular signature was assessed by RNA-sequencing. There was a time-dependent increase in fibrosis and stiffness after CF-LVAD. Transcriptome analysis revealed a unique mechanism for post-CF-LVAD fibrosis. There was no fibroblast activation, but rather a downregulation in extracellular matrix degrading enzyme pathways. Further research is needed to determine if modulation of these pathways may be a therapeutic target to minimize vascular remodeling and improve outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (CF-LVADs) are an increasingly utilized treatment for end-stage heart failure. As a larger number of patients are supported with these devices for longer periods of times, minimization of complications, including those uncovered when vasculature is re-exposed to pulsatile flow after transplant, is of paramount importance. Modern left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) were engineered to deliver continuous-flow with minimal or no bearings and have resulted in devices that have long-term mechanical durability. However, there is non-physiologic flow within the aorta due to the alterations in the normal laminar flow patterns in the ascending aorta as a result of the LVAD outflow graft. There is a growing body of evidence that some common CF-LVAD related complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding, stroke, hypertension, and pump thrombosis may have a pathophysiologic basis in the vasculature’s adaptations to the non-physiologic flow of CF-LVADs.(1) In addition, there is evidence that restoration of pulsatile-flow after a period of non-pulsatile flow can have effects on sympathetic nerve activity and carotid baroreceptor-mediated vascular tone that may contribute to complications such as vasoplegia after CF-LVAD patients undergo cardiac transplantation.(1–3)

We have previously reported in vivo evidence of significantly increased aortic stiffness after placement of CF LVADs in a large cohort of bridge to transplant patients. Echocardiographic assessment revealed subsequent partial reversal of this stiffening with restoration of normal aortic flow patterns after cardiac transplantation.(4) Furthermore, utilizing aortic tissue samples obtained from patients at the time of cardiac transplantation, we have shown there is histologic evidence of adventitial thickening, collagen deposition, and alterations in the elastin to collagen ratio among patients supported with a CF-LVAD prior to transplant compared to those patients without CF-LVAD support.(5) Employing uniaxial mechanical stress-strain testing, there was also direct in vitro evidence of vascular stiffening of the aortic wall samples from patients supported with a CF-LVAD.(5)

However, we have previously been unable to directly assess the effects of CF-LVAD on the aortic vasculature and study the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms for these observed vascular changes from the same patient due to the challenges in obtaining serial aortic tissue samples. Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to study aortic fibrosis directly before placement of a CF-LVAD and again after CF-LVAD exposure at the time of transplant in the same patients. We specifically aimed to describe the histologic structure and composition of the aorta, directly measure vasculature stiffness, and finally study the molecular signature of vascular remodeling using RNA-seq.

METHODS

Patient Selection and Human Aortic Tissue Acquisition

Paired aortic wall tissue samples were collected from 22 consecutive patients with end-stage heart failure undergoing bridge to transplant CF-LVAD during the time period from June 2013 to January 2016 at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The Pre-LVAD sample was the small section of aortic tissue from the ascending aorta that is removed by necessity for the LVAD outflow graft anastomosis. The Post-LVAD sample was the circumferential ring of the proximal ascending aorta above the aortic root that is removed with the failing heart by necessity at the time of heart transplantation. The duration of CF-LVAD support and the timing of when the Post-LVAD sample was obtained was based on clinical conditions (namely whenever a suitable donor was identified). In order to assess for time-related differences in the duration of CF-LVAD support, patients were categorized as short (2–6 months), intermediate (>6–12 months), and long (>12 months) duration of CF-LVAD support.

At the time of collection, a portion of the aortic tissue sample was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen in the operating room and then stored at −80°C for molecular analysis. For the post-LVAD samples (where a larger amount of aortic tissue was available), an additional tissue sample was placed in PBS solution and stored at 4°C for subsequent mechanical stress-strain testing. The remaining portions of the pre-LVAD and post-LVAD samples were placed in histological cassettes, fixed in formalin immediately after explant and processed for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections.

In addition, a trained physician retrospectively reviewed medical records and recorded de-identified clinical variables for each patient in a securely stored REDCap database. The clinical data were collected from the time closest to LVAD implantation and cardiac transplantation and included medications, echocardiography, and hemodynamics. The patient data obtained reflected the LVAD device settings that were clinically indicated at that time for the individual patients. The Colorado Multicenter Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for the collection, storage, and analysis of human tissue.

Aortic Wall Morphology

The pre-LVAD and post-LVAD aorta samples were fixed using 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated by ethanol, and embedded in paraffin in an orientation such that the resulting 4-um aorta sections would include adventitial to intimal layers that were aligned along a transverse aorta cross-section and were perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the ascending aorta. Paired pre- and post-LVAD aorta tissue sections were de-identified and processed for Russel-Movat’s Pentachrome staining in the same batch to differentiate various tissue components including collagen (yellow), elastin fibers (black), mucin (blue), muscle or fibrinous deposits (red) and nuclei (dark blue). Paired Russel-Movat’s Pentachrome-stained slides were available for 20 patients (sections from 2 patients did not properly stain in the same batch for technical reasons) and scanned with the Aperio ImageScope system (Vista) for quantitative analysis. Planimetry was used for general morphometric analysis, including measurements of total wall thickness as well as thickness of the arterial adventitia, media, and intima. Image analysis was performed with Image J software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Measurements of Aorta Collagen Content and Fibrosis

The extent of fibrosis in the aorta samples was measured using second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy as previously described.(6,7) SHG images fibrillar collagen and elastin based on its physical and structural properties in tissues without requiring special stains. Paired pre- and post-LVAD paraffin sections of aorta segments from 22 patients were rehydrated and imaged via multiphoton excitation using a Zeiss LSM780 light microscope equipped with a femtosecond pulsed Ti Sapphire laser (Chameleon Ultra; Coherent, Santa Clara) and ZEN software (2012 SP1 Black Edition). Images were acquired at 1024 × 1024 pixels (708.49 μ x 708.49 μ) using a Zeiss C-Apochromat 20X objective. The excitation source was tuned for 800nm to generate a SHG 400nm signal that was collected via a 390 nm-410 nm emission filter. Besides the SHG signal, the auto-fluorescence corresponding to elastin fibers was also observed via a wide range visible filter (420nm-700nm). The percent area and mean intensity of SHG+ collagen and elastin-fiber autofluorescence in the aorta was measured in four non-overlapping images using Image J 1.47v software (NIH). The relative changes in elastin and collagen were expressed as the ratio of the elastin fiber intensity to collagen SHG intensity. Data analysis compared the mean intensity units of SHG+ collagen and the mean ratio of elastin fiber to collagen intensity for pre-LVAD and post-LVAD samples. Matched samples from individuals were further divided into 3 groups based on the duration of LVAD support for 2–6 months, 6–12 month and >13 months.

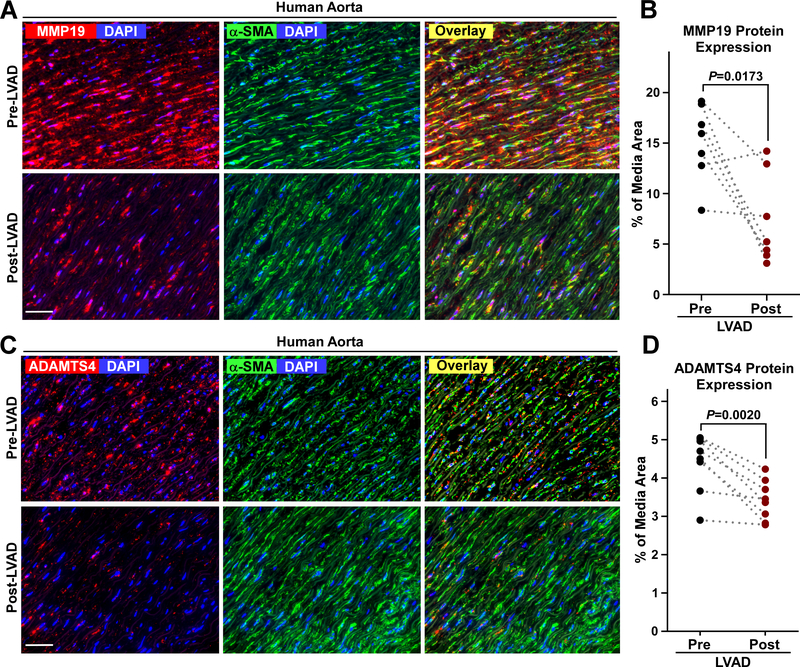

Immunofluorescence Microscopy of MMP19 and ADAMTS4 Abundance

Sections of aorta samples before and after LVAD exposure were deparaffinized, rehydrated and underwent antigen retrieval by heating for 20 minutes at 100°C in a decloaking chamber (Biocare). Adjacent aorta tissue sections were incubated with a primary rabbit polyclonal anti-human MMP19 (1:100, Abcam 135563) or rabbit polyclonal anti-ADAMTS4 (1:100, Abcam 219548). Antigen-antibody complexes were detected after serial incubations with goat anti-rabbit 594 (1:200, Invitrogen A11037) followed by mouse monoclonal anti-α-SMA 488 (1:1000, Sigma C6198) to identify the media layer and delineate the intima and adventitia layers. Sections were imaged using a Keyence BZ-X7100 Series Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence Corp. of America). Multiple non-overlapping color images per aorta sample were captured using DAPI, TRITC, GFP filters and BZ-X Viewer Software. The areas and mean intensity values of positive MMP19 and ADAMTS9 fluorescent signals in the media, intima and adventitia were quantified using Image J 1.47v software (NIH).

Multispectral Fluorescence Immunohistochemistry and Vectra Analysis

Aorta sections were sequentially stained with CD68, CD3, CD8, CD19, FoxP3, α-SMA, and DAPI at the Vectra Cell Phenotyping Core (Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Initiative, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus). Slides were dewaxed with xylene, heat treated in pH 9 antigen retrieval buffer for 15min in a pressure cooker, blocked in Antibody Diluent (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), incubated for 30 minutes with the primary antibody, 10 minutes with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary polymer (anti-mouse/anti-rabbit antibodies, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), and 10 minutes with HRP-reactive OPAL fluorescent reagents (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Slides were washed between staining steps with PBS 0.01% tween 20 and stripped between each round of staining with heat treatment in antigen retrieval buffer. After the final staining round the slides were stained with spectral DAPI and cover slipped with Prolong Diamond mounting media (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Multispectral imaging was performed using the Vectra 3.0 Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System (Akoya Biosciences). Whole slide scans were collected using the 10x objective and 10–15 regions were selected for multispectral imaging with the 20x objective that covered intima, media and adventitia layers of the aorta. The multispectral images were analyzed with InForm software (Perkin Elmer) to unmix adjacent fluorochromes, subtract autofluorescence, and segment the aorta tissues into intima, media, adventitia, and perivascular fat layers. The cells were segmented into nuclear and membrane compartments to phenotype the cells according to morphology and cell marker expression. The cell counts in each layer were tabulated for CD68+ macrophages, CD3+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, FoxP3+ T cells, CD19+ B cells and α-SMA smooth muscle cells. CD4+ cells were calculated as CD3+ minus CD8+ cell counts. The cell densities for each cell type were calculated as the cell counts per area (mm2) of adventitia, media, and intima.

Aortic Wall Uniaxial Stress-Strain Testing

All 22 post-LVAD aortic samples were mechanically tested within 72 hours of collection using an MTS Insight II (MTS Systems, Eden Prairie, MN) equipped with a 25-N load cell and environmental chamber filled with calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate buffered saline to ensure no smooth muscle contribution to the mechanics as previously described.(5,8) Uniaxial extension in the circumferential direction was applied at a constant crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/s, executing 5 successive preconditioning cycles to a prescribed elastin and collagen activation strain. The tensile force and specimen length were continuously recorded, and the final loading cycle of the uniaxial preconditioned sample was analyzed. From the recorded date, stress-strain curves were plotted for each sample and the high-strain elastic modulus (the second linear slope of the stress-strain curve) was calculated for each sample.

Aorta RNA-Sequencing Analysis

In order to study the molecular mechanisms of aortic fibrosis, paired aortic tissue samples were selected for molecular analysis from a subset of 7 patients from the total 22 patient cohort. This subset of 7 patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy had a mean duration of CF-LVAD support of 170±94 days. After reviewing the SHG microscopy data, the rationale for focusing on samples obtained from patients with a shorter duration of CF-LVAD support was to study the cellular mechanisms behind the development of fibrosis as opposed to studying patients with a longer duration of support who had already developed end-stage fibrosis.

RNA was isolated from aortas using modified Trizol extraction. Following addition of chloroform and centrifugation, the aqueous phase was added to ethanol, loaded onto an RNeasy column (Qiagen) and processed according to manufacturer’s instructions with on column DNAse treatment. Complementary DNA libraries for next generation sequencing were prepared using the Ovation RNA Seq V2 system (Nugen). Libraries were submitted to the University of Colorado Cancer Center Genomics and Microarray Shared Resource for sequencing (HiSeq2000).

Raw sequence files will be deposited in the Sequence Read Archive before publication. Single-ended (126 or 150 bp) reads were trimmed with Trim Galore (v.0.3.7 http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore) and controlled for quality with FastQC (v0.11.3, http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) before alignment to the human genome (Hg38/GRCh38 using transcript Gencode release 26 annotations). Reads were aligned using STAR in single-pass mode (v.2.5.2a_modified, https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR)(9), with standard parameters but specifying “--alignIntronMax 100000 --quantMode GeneCounts”. Protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts were processed separately. Reads mapping to chrM were removed before further processing. Raw counts were loaded into R (http://www.R-project.org/) and edgeR(10) was used to perform upper quantile, between-lane normalization, and DE analysis. Transcripts with a median level across all samples < 1 mapped read per million (MMR) were filtered out before differential expression (DE) analysis. Values generated with the cpm function of edgeR, including library size normalization and log2 conversion, were used in figures. Heat maps were generated using pheatmap (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html).

Gene expression values and differentially expressed genes are found in Supplemental Table 1. The core analysis function within Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Qiagen Inc.) was used to further interrogate the differentially expressed mRNAs. Results from canonical pathways, causal networks, diseases and biofunctions, and upstream regulators are found in Supplemental Tables 2–5. The path designer tool was used to prepare Figure 4D. The associated network was displayed and members of the network that did not display altered expression, except extracellular matrix (ECM), were removed and the remaining central network was retained (e.g. if deletion of a network member caused isolation of another member of the network, the isolated member was also deleted regardless of expression change). Multiple ECM related genes/proteins (collagens/elastins) were consolidated to “ECM”. Also, depictions of matrix metalloproteases and metalloproteases were consolidated to “metalloproteases”. Green arrows indicate specific members of the gene/protein family that led to the analysis indicating a particular gene/protein family. Line lengths encode no information. Solid lines indicate direct interaction while dashed lines indicate indirect interaction as determined by the IPA knowledge base.

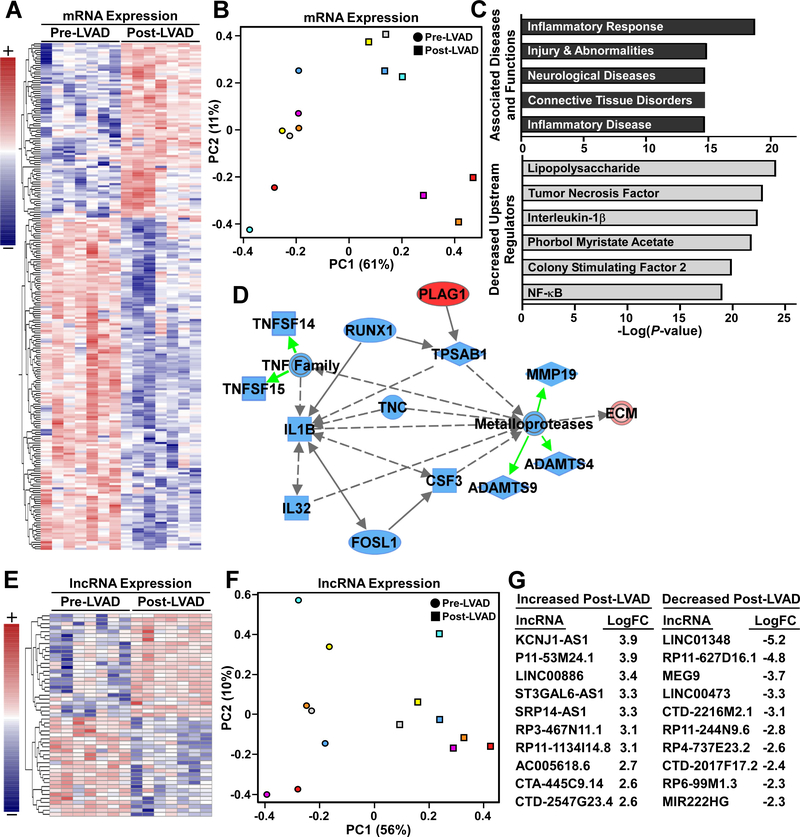

Figure 4. Aorta transcriptome remodeling in response to CF-LVAD implantation.

A, Row normalized heat map for 235 protein coding transcripts that were differentially expressed Pre- versus Post-LVAD. B, Principal component analysis (PCA) of gene expression clearly segregated Pre- versus Post-LVAD, with 61% of variance accounted for by principal component 1 (PC1, x-axis) (color indicates patient and shape indicates LVAD status). C, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), with P-values plotted for representative associated diseases and functions, as well as predicted effect of LVAD on the activity of identified upstream regulators. D, IPA identified suppression of a network that could explain ECM accumulation Post-LVAD. Downregulation of several inflammation associated signals (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-32) was predicted to also reduce expression of specific metalloproteases (ADAMTS4, ADFAMTS9, MMP19) and lead to increased ECM protein half-life and accumulation. E, Heat map of 75 long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) that were differentially expressed. F, Pre- and Post-LVAD samples were separable via PCA of lncRNA differential expression. G, Expression (LogFC values) for the 10 most activated and 10 most inhibited lncRNAs.

To determine genes associated with collagen and ECM biology, for Supplemental Figure 2, a molecule list was created using the IPA knowledge base. The list was generated by searching the Diseases and BioFunctions tab for keywords collagen and ECM (individually) and loading molecules identified with the search results. These covered a wide variety of ECM and Collagen related diseases and biofunctions (including expression, synthesis, modification, trafficking, assembly, and degradation). 972 molecules were identified (included genes and chemicals). A pathway was created with this list and using the pathway “Grow” function, expression information from the core IPA analysis was overlaid. All chemical entities and genes not significantly affected by LVAD status were removed, leaving the genes depicted in Supplemental Figure 2.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using PRISM 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Column statistics and D ‘Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality tests were performed to determine the mean, standard deviation, and normality of the data. For comparisons between pre- and post-LVAD groups, the paired t-test for parametric data and the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test for non-parametric data were used.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

Paired aortic tissue samples and clinical data were obtained from 22 consecutive patients with end-stage heart failure undergoing bridge to transplant CF-LVAD from June 2013 to January 2016. The mean age at the time of CF-LVAD placement was 52±12 years, 16 patients received a HeartMate II device and 6 patients received a HeartWare HVAD device (Table 1). The overall mean duration of CF-LVAD support was 224±193 days. The short duration of CF-LVAD support cohort included 14 patients (mean of 115±40 days), the intermediate duration cohort included 3 patients (mean 247±63 days), and the long duration cohort included 5 patients (mean 517±200 days). As expected there were differences in natriuretic peptide levels, left-sided filling pressures, mean arterial pressure, cardiac index, pulmonary vascular resistance, and some medications after placement of a CF-LVAD as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Clinical characteristics at the time of continuous-flow left ventricular assist device implantation (Pre-LVAD) and at the time of cardiac transplantation (Post-LVAD).

| Patient Demographics | N=22 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52 ± 12 | |

| Female sex | 2 (9%) | |

| Ethnicity/Race | ||

| Caucasian | 13 (59%) | |

| African American | 4 (18%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (14%) | |

| Asian | 2 (9%) | |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 8 (36%) | |

| Nonischemic cardiomyopathy | 12 (54) | |

| HeartMate II device | 16 (73%) | |

| HeartWare device | 6 (27%) | |

| Duration of LVAD support (days) | 224 ± 193 | |

| Pre-LVAD | Post-LVAD | |

| Clinical Characteristics and Hemodynamics | ||

| Brain natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 1933 ± 1168 | 249 ± 184* |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 20 ± 10 | 23 ± 10 |

| Left ventricular diastolic volume (mL) | 249 ± 106 | 172 ± 125* |

| Left ventricular systolic volume (mL) | 204 ± 109 | 138 ± 110* |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 89 ± 19 | 87 ± 17 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 72 ± 6 | 84 ± 12* |

| Right atrial pressure (mmHg) | 11 ± 8 | 8 ± 5 |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure (mmHg) | 36 ± 12 | 23 ± 8* |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mmHg) | 23 ± 10 | 12 ± 7* |

| Cardiac index (L/minute/m2) | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4* |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (Wood units) | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 1.2* |

| Medications | ||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 1 (5%) | 12 (54%)* |

| β-blocker | 2 (9%) | 19 (86%)* |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 17 (77%) | 17 (77%) |

| Hydralazine/nitrates | 8 (36%) | 2 (9%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 3 (14%) | 5 (23%) |

| Diuretic | 15 (68%) | 12 (54%) |

| Digoxin | 9 (41%) | 6 (27%) |

| Intravenous inotrope | 15 (68%) | 0 (0%)* |

P<0.01 for comparison of Pre-LVAD vs. Post-LVAD

ACE=Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ARB=Angiotensin Receptor Blocker

Aortic Adventitial Thickening and Increased Aortic Collagen Deposition and Fibrosis with CF-LVADs

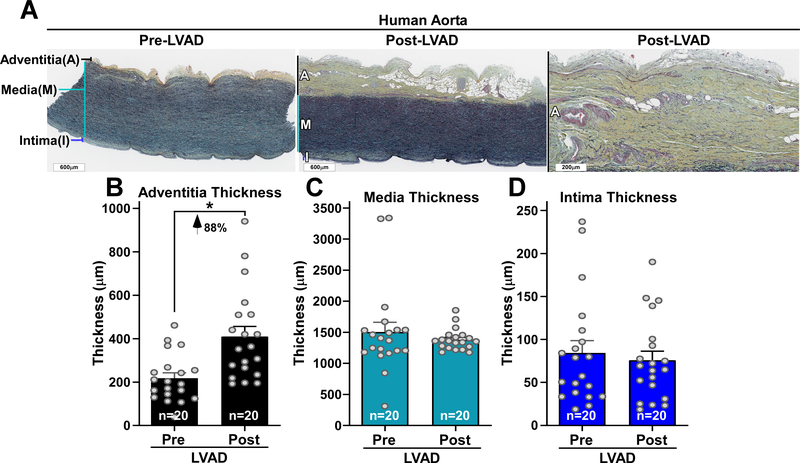

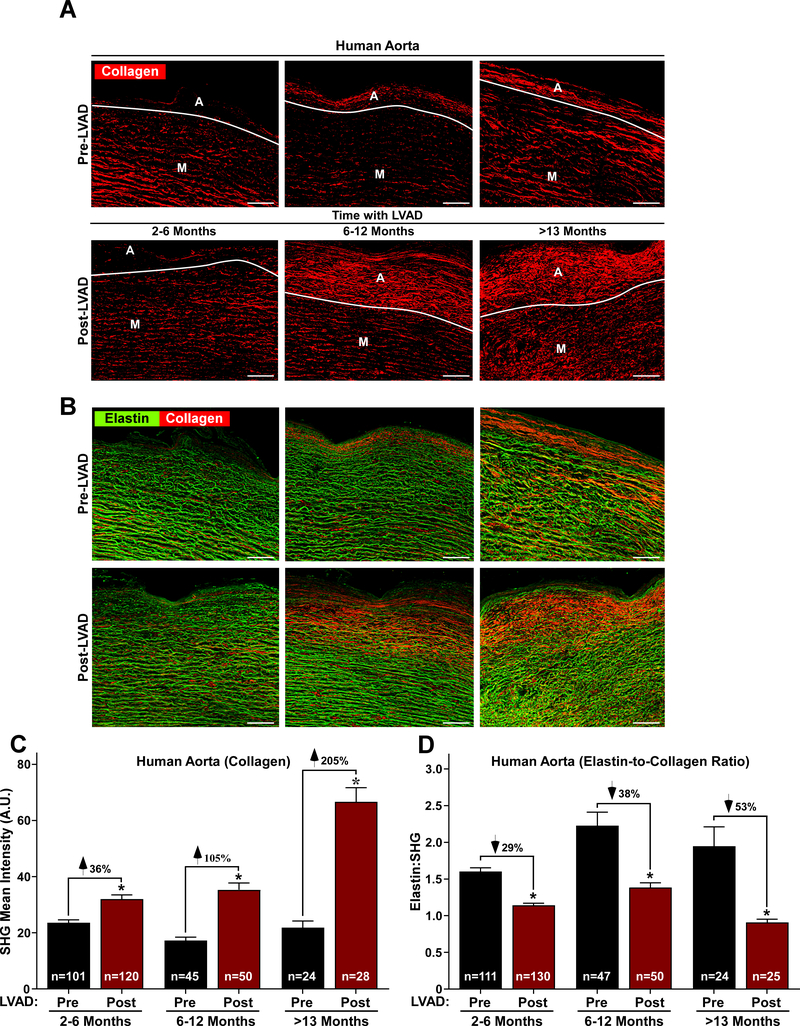

There was a significant increase in aortic adventitial wall thickness after CF-LVAD placement with no changes in the thickness of the media and intima (Figure 1A through 1D). SHG imaging revealed a significant increase in mean fibrillar collagen intensity with a concomitant decrease in vascular elastin abundance (Figure 2A and 2B). Fibrillar collagen increased from 22±11 pre-LVAD to 41±24 a.u. post LVAD (p<0.0001), and this increase in collagen intensity after LVAD placement was more pronounced among patients with a longer duration of LVAD support, as patients with greater than a year of CF-LVAD support having more than a 200% increase in collagen deposition after LVAD placement (Figure 2C). The ratio of elastin to collagen also decreased after LVAD placement, with a proportional larger difference among patients with a greater duration of LVAD support (Figure 2D).

Figure 1. Human aorta is remodeled by continuous-flow LVAD support.

A, Movat’s Pentachrome-stained aorta sections are shown from the same individual before and after LVAD exposure. Scale bars 600 microns. Right panel is higher power image of expanded adventitia layer post-LVAD. Scale bar 200 microns. B through D, Data points represent the mean thickness (microns) of adventitia (B), media (C) and intima (D) layers in the pre-LVAD aorta and post-LVAD aorta collected from N=20 individuals. Values represent means +SEM. *Indicates the paired t-test, two-tailed P-value =0.0018 for the adventitia thickness pre-LVAD compared to post-LVAD aorta.

Figure 2. CF-LVADs increase collagen and reduce elastin in a time-dependent manner.

A and B, Second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy of human aorta sections revealing fibrillar collagen (red) and elastin (green) (scale bar = 50 μm). The boundaries of the adventitia (A) and media (M) are indicated. Quantification of collagen (C) and elastin-to-collagen ratios (D). N indicates the total number of images analyzed from 13 (2–6 months), 5 (6–12 months) and 3 (>13 months) aortas. Values represent means +SEM. P < 0.0005 by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

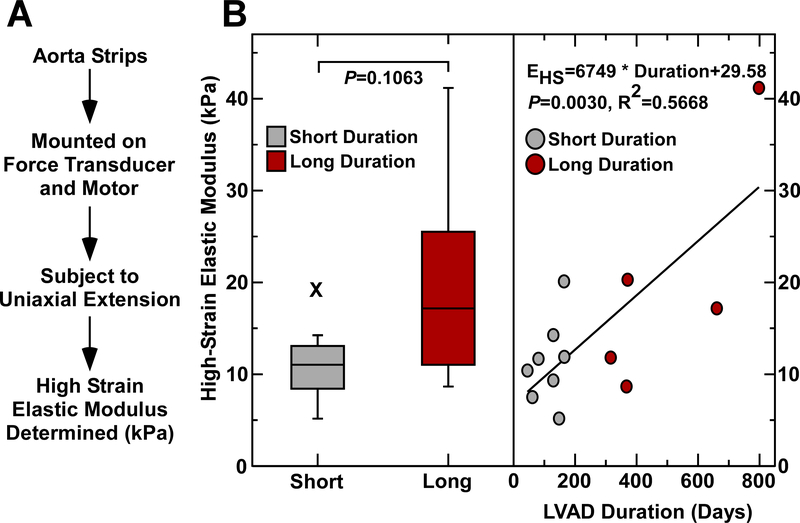

Increased Aortic Modulus with Longer Duration of CF-LVAD Support

Stress-strain curves were analyzed from aortic wall samples obtained after LVAD placement to calculate the high-strain elastic modulus, an in vitro assessment of tissue stiffness (Figure 3A). The high-strain elastic modulus was stratified based on the duration of LVAD support, and there was a positive correlation with high elastic modulus correlating with a greater duration of LVAD support (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Stress-strain testing reveals increased stiffness with longer duration of CF-LVAD.

A, Post-LVAD aortic tissue strips were attached to a motor and force transducer. Uniaxial extension in the circumferential direction was applied and stress-strain curves were generated. The high strain elastic modulus was calculated from these stress-strain curves. B, Stiffening of post-LVAD aortas greater with longer versus shorter duration of CV-LVAD support.

Aorta Transcriptome Remodeling Post CF-LVAD Implantation

To determine potential molecular activators of post CF-LVAD aortic stiffing and adventitial thickening, RNA-Seq analysis was conducted on the same patient paired samples (N=7 patients, 14 samples). This analysis revealed 235 differentially expressed mRNAs (Figure 4A). Principle component analysis of these genes clearly segregated pre- vs post-LVAD samples (Figure 4B). Paradoxically, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) indicated pathways canonically associated with fibrosis and inflammation were suppressed following support with CF-LVADs (Figure 4C, Supplemental Figure 1). Though canonical pathway and upstream regulator analysis could not explain the adverse aortic remodeling, network analysis provided additional insights. Specifically, suppressed tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) signaling, which is typically associated with inflammation and stress, was predicted to also reduce the expression of critical metalloproteases that regulate the extracellular matrix. The specific metalloproteases identified in the network were MMP19, ADAMTS4, and ADAMTS9, all of which were significantly reduced at the mRNA expression level following CF-LVAD placement (Figure 4D). Of >500 genes in the IPA Knowledge Base related to collagen/ECM biology, only 42 genes were differentially expressed, and suggested reduced collagen degradation, as opposed to increased collagen synthesis, in post-LVAD aortas (Supplemental Figure 2). Thus we hypothesized that decreased expression of these metalloproteases lead to increased ECM protein half-life and might explain ECM accumulation in the CF-LVAD aorta.

Seventy-five long non-coding (lnc)RNAs were also differentially expressed following CF-LVAD support (Figure 4E). Reflective of the importance of lncRNA biology, there was clear segregation of the pre- vs post-LVAD samples via principal component analysis differential expression (Figure 4F). The top 10 most upregulated and downregulated lncRNAs in aortas from patients with CF-LVADs are indicated (Figure 4G).

Downregulation of Aortic MMP19 and ADAMTS4 Protein Expression Post CF-LVAD Implantation

To evaluate whether the protein abundances of metalloproteases were suppressed after LVAD-exposure as suggested by the RNA-sequence analysis, we evaluated levels of MMP19 and ADAMTS4 protein expression in paired pre- and post-LVAD samples by immunofluorescence microscopy. The most abundant levels of MMP19 and ADAMTS4 were observed in the media layer and were significantly higher for the pre-LVAD aorta compared to post-LVAD (Figure 5).

Figure 5. MMP19 and ADAMTS4 abundance is reduced after CF-LVAD implantation.

A, Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of MMP19 (red) and alpha smooth muscle cell actin (α-SMA, green) abundance in the aorta media Pre-LVAD (top row) and Post-LVAD (lower row). B, The abundance of MMP19 protein is reported as the mean area of positive MMP19 immunoreactivity per media area. Data points indicate the abundance of MMP19 in Pre-LVAD (black circle) and Post-LVAD (red circle) aorta. C, Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of ADAMST4 (red) and α-SMA (green) protein abundance in the aorta media Pre- and Post-LVAD. D, The abundance of ADAMTS4 protein is shown as the mean area of ADAMTS4 immunoreactivity per media area. Each data point is the mean value from 4–5 non-overlapping high power (400x) images of aorta media per sample. Dashed lines link pairs of pre- and post-LVAD data from the same individual. Scale bar is 50 microns.

Based on reports that inflammatory cells are involved in vascular remodeling and may also release metalloproteases(11), as do media smooth muscle cells, we explored the hypothesis that inflammatory cell infiltrates may be different among a subset of pre- and post-LVAD aorta samples. Multiplex imaging and Vectra analysis and phenotyping of immune cells were evaluated in adventitia, media and intima layers of 5 paired pre- and post-LVAD aortas by Vectra analysis. The most abundant immune cell types, including CD68+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells, were observed in media and adventitia layers as shown in Supplemental Figure 3. There was no consistent change in the cell densities of these immune cell types after LVAD exposure.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that there is time-dependent fibrosis and vascular stiffening within the aorta after CF-LVAD placement. There was evidence of adventitial thickening, collagen deposition, and a decrease in the elastin-to-collagen ratio with CF-LVAD support which are all histologic evidence of vascular fibrosis. This histologic fibrosis was confirmed with ex vivo mechanical stress strain testing revealing a higher elastic modulus from aortic samples from patients with longer durations of LVAD support.

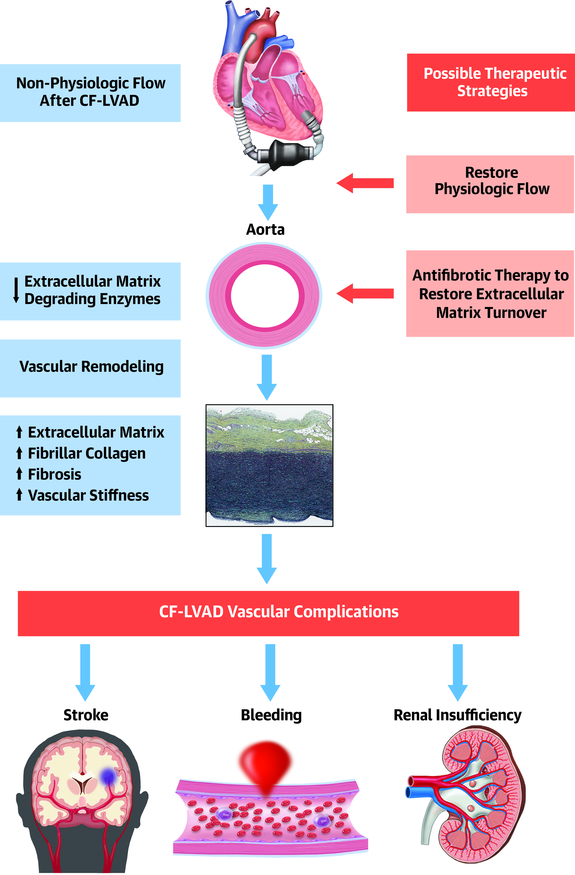

The molecular basis for these vascular changes suggest that there is down regulation of matrix degrading enzymes with subsequent increased accumulation of extracellular matrix as the etiology for the fibrotic deposition of collagen (Central Illustration). This suggests that strategies to prevent the down regulation of matrix degrading enzymes could be potential therapeutic targets to prevent vascular fibrosis. It is unclear if the paradoxical finding of apparently decreased inflammatory and fibrotic signaling in the remodeled aorta is a reflection of restored perfusion and decreased cardiac workload, which blunts cardiac derived stress signals and general systemic catecholamine load,(12) or if continuous flow does in fact lead to direct suppression of inflammatory signals (e.g. TNF and IL-1β). Given that fibroblast activationassociated pathways are already suppressed in this setting, directly targeting the fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation process, a common focus in most organ fibrosis research, is unlikely to provide benefit. Rather, our data suggest post LVAD aortic fibrosis is more likely to be driven by increased ECM protein half-life as opposed to increased deposition. Potential therapeutic strategies could involve targeting the negative regulators of intermediate inflammatory signals (e.g. targeting PLAG1 or KLF15) or directly stimulating metalloprotease expression or activity.

Central Illustration. Continuous-flow LVAD-induced aortic fibrosis and stiffening.

The non-physiologic flow after continuous-flow LVAD placement leads to downregulation of extracellular matrix degrading enzyme expression in the aorta, with resulting accumulation of extracellular matrix and deposition of fibrillar collagen. This aortic fibrosis results in vascular stiffening. We posit that these changes contribute to vascular complications in continuous-flow LVAD patients. Therapeutic strategies based on restoring physiologic blood flow and/or enhancing extracellular matrix turnover are warranted to improve patient outcomes.

We have also included an assessment of lncRNA expression in CF-LVAD exposed aortas. LncRNAs are non-coding RNA species that can regulate gene expression and cellular function through a variety of molecular mechanisms, and several have been shown to be critical in development and plasticity of the heart and vasculature (13). Unfortunately, these molecules have not been characterized sufficiently in the cardiovascular system to facilitate robust network or pathway analysis. For instance, only 2 of the 20 lncRNAs identified in Figure 4G have been studied in contexts relevant to cardiovascular biology. Though no function has been attributed to MEG9, its expression is upregulated in hypoxic endothelium (14). LINC00473 has been more widely studied, though predominantly in cancer biology. Reported as a sponge for well over 10 specific microRNAs, LINC00473 expression can facilitate rapid and broad shifts in gene expression and has been implicated in a number of pathways widely considered master regulators, including those associated with FOXP1, ROBO1, JAK/STAT, β-catenin, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR. Recently, this lncRNA was shown to be up regulated in VSMCs treated with H2O2 and was associated with activation of apoptosis (15). LncRNA analysis is included to help stimulate construction of databases that allow analyses similar to that presented for the protein-coding RNAs, and to provide fuller molecular characterization of post-LVAD remodeling of the aorta.

It is unclear whether the modulation of non-physiologic flow from CF-LVADs itself could be such a therapeutic target. Similar fibrotic changes have been observed in coronary arteries from patients with CF-LVADs.(7) However, it is not known if the molecular adaptions could be reversed by restoration of pulsatility. CF-LVAD-induced fibrosis in the heart has been a matter of debate, although, consistent with our findings, decreased ECM degradation in the LV is a suspected mechanism(16). It is also unclear if conventional pharmacologic agents that effect myocardial remodeling such as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers may have a protective role as the pathways involved in adverse aortic remodeling seem distinct from those central to heart failure. This notion is supported by the observation of increased fibrosis despite increased use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers after LVAD implantation. Thus, it is possible that novel anti-fibrotic pharmacotherapies such as histone deacetylase inhibitors may need to be studied in the prevention of vascular fibrosis after CV-LVAD.(17).

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis. The logistical complexities and longitudinal study follow-up time required to collect paired tissue samples from patients undergoing LVAD implantation followed by cardiac transplantation limited the total sample size—though the 22 paired samples analyzed in this report is larger than similar studies in the field that utilize human samples. Due to patient safety, tissue samples could only be obtained immediately before LVAD implantation and after LVAD explantation (which was determined by when the patient underwent cardiac transplantation), so we were unable to systematically assess for vascular changes at pre-specified intervals of LVAD support. Furthermore, we could not evaluate the reversibility of the observed vascular remodeling after removal of the CF-LVAD with cardiac transplantation. Similarly, tissue samples of aorta were obtained from slightly different locations within the proximal ascending aorta by surgical necessity, and sufficient perivascular tissues were not uniformly available in both pre- and post-LVAD samples for analysis of vascular and lymphatic structures. The patients’ background pharmacologic therapy and LVAD setting were based on clinical needs, and the small number of patients limits the ability to assess for changes based on the etiology of heart failure, sex-based differences, concomitant medications, or LVAD settings. In addition, the potential confounding effect of increased use of β-blockers, decreased use of inotropes, and increased use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers after LVAD implantation towards aortic fibrosis cannot be determined from this analysis. However, this combination of mediation changes are usually associated with a reduction in fibrosis, suggesting that the observed increase in aortic fibrosis after CF LVAD implant occurs due to factors beyond changes in pharmacologic therapy.

Conclusions

There is vascular fibrosis and stiffening within the aorta after CF-LVAD with significant collagen deposition and loss of elastin. The degree of this vascular remodeling correlates with the duration of CF-LVAD support. The molecular mechanisms for the development of aortic fibrosis are unique in that rather than upregulation of traditional inflammatory pathways and subsequent fibroblast activation and fibrosis, there is instead downregulation of matrix degrading enzymes with subsequent fibrosis. Further research is needed to determine if modulation of the non-physiologic flow patterns from CF-LVADs (as some of the newer LVADs do allow some restoration of pulsatility) or pharmacologic treatments could abrogate the vascular fibrosis. In addition, additional studies are needed to determine if prevention of vascular fibrosis may be a strategy to reduce CF-LVAD complications such as stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding from arteriovenous malformations, and to ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspectives.

Competency in Patient Care and Procedural Skills:

Patients with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices (CF-LVAD) may develop aortic fibrosis and stiffening that increase with the duration of CF-LVAD support, potentially contributing to the risks of hypertension, stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, and right ventricular failure.

Translational Outlook:

Since the molecular basis for vascular remodeling during CF-LVAD support involves downregulation of matrix degrading enzymes without fibroblast activation, modulation of matrix degrading enzyme pathways might mitigate vascular remodeling and improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Peter Buttrick, Dr. Michael Bristow, and the University of Colorado’s Division of Cardiology for ongoing maintenance of the human cardiac tissue biobank. In addition, we thank Radu Moldovan and Greg Glazner of the University of Colorado Advanced Microscopy Core Facility for assistance with confocal microscopy. RNA sequencing was performed in the Genomics and Microarray Core and Vectra imaging in the Human Immune Monitoring Shared Resource at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Keyence microscopy was performed in the Consortium for Fibrosis Research & Translation of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

Funding/Support: A.V.A was supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association and by the Boettcher Foundation’s Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Program. T.A.M. was supported by the National Institute of Health by grants HL116848, HL147558, DK119594, HL127240, HL150225, and by the American Heart Association (16SFRN31400013). T.A.M. also received support from the Colorado Office of Economic Development & International Trade (CTGGI 19-3579) through the University of Colorado SPARK Program. M.S.S. was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL126354 and AG056848. M.C.M.W.−0.E was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute NIH Gran Numbers R01 HL121877 and R01 HL123616. REDCap provided by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535. Imaging experiments were performed in the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Advanced Light Microscopy Core supported in part by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR002535. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: T.A.M. is on the scientific advisory board of Artemes Bio, Inc., received funding from Italfarmaco for an unrelated project, and has a subcontract from Eikonizo Therapeutics related to an SBIR grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL154959). The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviation list

- CF-LVAD

Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device

- LVAD

Left Ventricular Assist Device

- SHG

Second Harmonic Generation

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- ECM

Extracellular Matrix

- TNF

Tumor Necrosis Factor

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- lncRNAs

long non-coding RNAs

- MMP-19

matrix metalloproteinase-19

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Purohit SN, Cornwell WK 3rd, Pal JD, Lindenfeld J, Ambardekar AV. Living Without a Pulse: The Vascular Implications of Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e004670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornwell WK 3rd, Tarumi T, Stickford A et al. Restoration of Pulsatile Flow Reduces Sympathetic Nerve Activity Among Individuals With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Circulation 2015;132:2316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandelbaum I, Burns WH. Pulsatile and Nonpulsatile Blood Flow. JAMA 1965;191:657–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel AC, Dodson RB, Cornwell WK 3rd et al. Dynamic Changes in Aortic Vascular Stiffness in Patients Bridged to Transplant With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambardekar AV, Hunter KS, Babu AN, Tuder RM, Dodson RB, Lindenfeld J. Changes in Aortic Wall Structure, Composition, and Stiffness With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices: A Pilot Study. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:944–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Nadiarynkh O, Plotnikov S, Campagnola PJ. Second harmonic generation microscopy for quantitative analysis of collagen fibrillar structure. Nat Protoc 2012;7:654–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambardekar AV, Weiser-Evans MCM, Li M et al. Coronary Artery Remodeling and Fibrosis With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e004491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodson RB, Rozance PJ, Reina-Romo E, Ferguson VL, Hunter KS. Hyperelastic remodeling in the intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) carotid artery in the near-term fetus. J Biomech 2013;46:956–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26:139–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toba H, Cannon PL, Yabluchanskiy A, Iyer RP, D’Armiento J, Lindsey ML. Transgenic overexpression of macrophage matrix metalloproteinase-9 exacerbates age-related cardiac hypertrophy, vessel rarefaction, inflammation, and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2017;312:H375–H383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koerner MM, El-Banayosy A, Eleuteri K et al. Neurohormonal regulation and improvement in blood glucose control: reduction of insulin requirement in patients with a nonpulsatile ventricular assist device. Heart Surg Forum 2014;17:E98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratton MS, Farina FM, Elia L. Epigenetics and vascular diseases. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2019;133:148–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voellenkle C, Garcia-Manteiga JM, Pedrotti S et al. Implication of Long noncoding RNAs in the endothelial cell response to hypoxia revealed by RNA-sequencing. Sci Rep 2016;6:24141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian Z, Sun Y, Sun X, Wang J, Jiang T. LINC00473 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell viability to promote aneurysm formation via miR-212–5p/BASP1 axis. Eur J Pharmacol 2020;873:172935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klotz S, Jan Danser AH, Burkhoff D. Impact of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support on the cardiac reverse remodeling process. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2008;97:479–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuetze KB, McKinsey TA, Long CS. Targeting cardiac fibroblasts to treat fibrosis of the heart: focus on HDACs. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2014;70:100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.