Abstract

Purpose of review:

Though gut dysbiosis can hasten disease progression in end-stage liver disease and contribute to disease severity, morbidity, and mortality, its impact during and after transplant needs further study.

Recent findings:

Changes in the microbiome are associated with hepatic decompensation. Immune homeostasis is further disrupted during transplant and with immunosuppressants required after transplant. There is increasing evidence of the role of microbiota in peri-and post-transplant complications.

Summary:

Though transplant is highly successful with acceptable survival rates, infections, rejection, disease recurrence, and death remain important complications. Prognostication and interventions involving the gut microbiome could be beneficial.

Keywords: Microbiome, liver transplantation, gut dysbiosis

Introduction:

Microbiome is a term used to described intestinal microbes and their genes. The human microbiome has 10-100 trillion bacteria, viruses and fungi that are critical in maintaining homeostasis [1]. This homeostasis is disrupted in patients with cirrhosis. Although many theories exist, the prevailing thought is that intestinal permeability and gut dysbiosis promote an environment where pathogenic bacteria thrive [2]. Dysbiosis suggests changes in the normal microbiome, such as a decrease in symbionts and an increase in pathobionts, that lead to changes in physiologic function. In cirrhosis, elevated portal pressures affect intestinal wall structure by vascular congestion, edema, and loss of tight junction integrity.

In end stage liver disease, the only treatment option is liver transplantation. Although survival rates after transplant at five years are excellent and exceeds 75%, host factors, operative factors, and factors related to post-transplant care can affect survival rates to different degrees. Changes in the gut microbiome that favor relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria is a common theme seen throughout the transplantation process, with the possibility of partial recovery after transplant. Infection prevention should be at the forefront of cirrhosis management. An infection at any stage can result in an inflammatory response, endotoxemia and increase mortality. In the post-transplant period, infections can lead to graft failure, multi-organ failure, and death. Therefore, although complex, the interplay between the gut microbiome and liver transplantation warrants attention.

In this review, we present current data on the impact of the gut microbiome pre, peri, and post-liver transplant.

Pre-transplant changes:

The gut microbiome plays an important role in the liver-gut axis by way of lipid, choline, and bile acid metabolism. Bacteria are responsible for mucosal barrier integrity by way of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) binding to pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and indirectly through production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as butyrate. PAMPs (like lipopolysaccharide, LPS) active innate immune cells and lead to inflammation and fibrosis. SCFAs facilitate neutrophil chemotaxis and induction in endothelial cells, thus play an important role in hepatic immunity. Dietary choline is converted to trimethylamine (TMA) by gut bacteria which is then converted to TMA-N-oxide (TMAO) after entering the portal circulation. TMAO has been implicated in increasing hepatic steatosis by way of triglyceride production.

In chronic liver disease there is decreased conversion to secondary fecal bile acids which normally regulate peptide production and help to maintain gut mucosal integrity. Thus, this creates a milieu conducive to SIBO and leads to functional changes with increased intestinal permeability. Patients with cirrhosis have an imbalanced microbiome as well, with less Bacteroidetes (potentially beneficial), and more Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria (potentially pathogenic) compared to control groups [4].

Any disruption leading to dysbiosis can impact the liver-gut axis (Figure 1). Dysbiosis occurs in the setting of a decrease in the number of taxa and their distribution in a single community (alpha-diversity) or homogeneity amongst community samples (beta-diversity). Shannon diversity index (SDI) is a qualitative marker of the richness (number of bacterial species) and evenness (relative abundance of a species) in an ecosystem. In cirrhosis, alpha-diversity indices like SDI can characterize diversity in an ecosystem (microbiome in cirrhosis) with higher values indicating a large number of taxa with an even distribution of abundance.

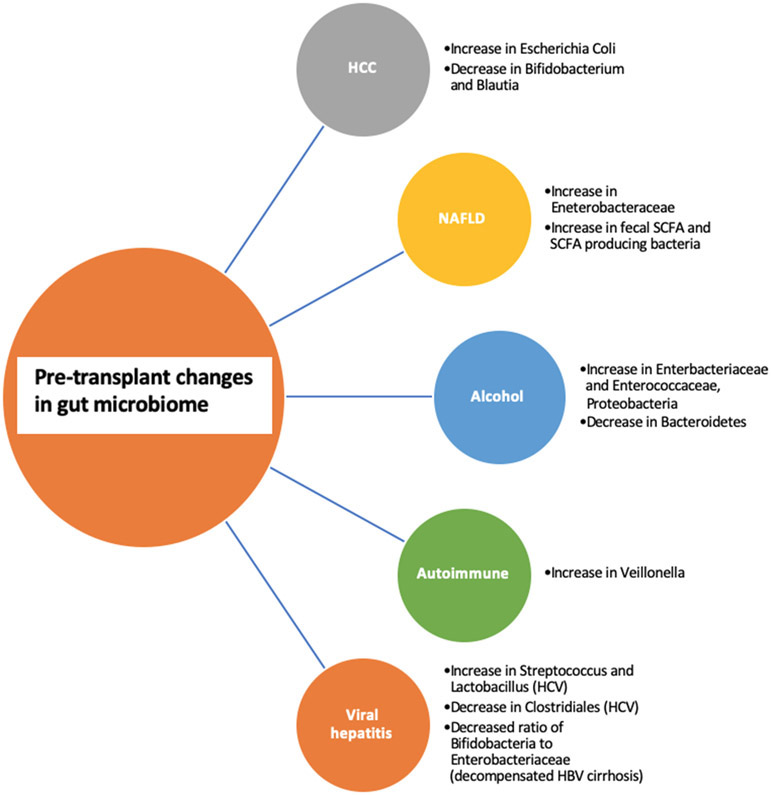

Figure 1.

Pre-transplant changes based on etiology of liver disease

HCC:

In a study by Grat et al. of thirty patients (fifteen with and fifteen without HCC), stool culture analysis found higher Escherichia Coli concentrations in those with HCC [5]. A similar study found that in NAFLD-HCC patients there was a decrease in Bifidobacterium and Blautia compared to those with NAFLD and no HCC [6]. These bacteria may be protective, and the microbiome may play a role in carcinogenesis.

NAFLD:

Although the link between NAFLD and the microbiome has been studied extensively, it is challenging to elucidate if the differences noted are from liver disease or the co-existing conditions of the metabolic syndrome. Most studies have demonstrated a relative increase in stool Enterobacteriaceae [7]. As steatosis progresses to cirrhosis, changes in short chain fatty acid concentrations are observed, although results are conflicting. This is likely because SCFAs can be either pro or anti-inflammatory based on its concentration. Though limited by a small sample size of 35 patients (17 of whom were controls), Jin et al. found that compared to controls, patients with cirrhosis had significantly altered microbiome diversity, lower stool SCFAs and less butyrate production [8]. In contrast, in a study of NASH patients, compared to controls, these patients had higher fecal SCFA and higher levels of SCFA-producing bacteria. These functional changes were associated with T-cell differentiation and features of disease progression [9].

Alcohol:

Bacteria metabolize ethanol into acetaldehyde and acetate via aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). Because Enterobacteriaceae are rich in ALDH, increased levels lead to more acetaldehyde which cause immune activation, inflammation and further disrupt the mucosal barrier [10-11]. Changes in bile acids have been observed in alcohol related liver disease patients, as well as decreased bacterial diversity and increases in potentially pathogenic bacteria such as, Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcaceae. Alcohol in and of itself can lead to hepatotoxicity by way of gut derived bacterial endotoxins [12-13]. Mutlu et al. reported dysbiosis using colonic biopsy samples (lower median abundances of Bacteroidetes and higher Proteobacteria) that correlated with high levels of endotoxin [14]. Interestingly, duration of sobriety did not affect the presence of dysbiosis, therefore suggesting that the effects of chronic alcohol consumption are long-lasting [14].

Autoimmune:

A cross-sectional study of treatment naïve PBC patients reported a decrease in microbial diversity compared to controls [15]. The authors then followed patients prospectively and reported partial improvement in gut dysbiosis after 6 months of UDCA treatment. Another cross-sectional study of patients with treatment naïve autoimmune hepatitis reported lower alpha-diversity compared to controls [16]. Disease severity showed positive correlation with pathogenic taxa such as Veillonella. Though limited by its study design and sample size, the authors enforced the link between compositional and functional gut microbiome changes and the evolution of autoimmune liver disease.

Viral hepatitis:

The studies on the relationship between the gut microbiome and viral hepatitis provide mixed results. Some studies report lower bacterial diversity in chronic HCV individuals compared to healthy controls with a decrease in Clostridiales and an increase in Streptococcus and Lactobacillus [17]. Similarly, a cross-sectional study of HCV patients with and without cirrhosis found that with increasing fibrosis, there was observed significant differences in overall microbial communities as well as decreased alpha diversity [18]. Perhaps this relationship is a result of the HCV itself or modulated by changes in the innate immune system. A study of Chinese patients with chronic HBV proposed use of the Bifidobacteria/Enterobacteriaceae (B/E) ratio as a measure of dysbiosis since this ratio significantly decreased as patients progressed from the asymptomatic carriage phase to decompensated cirrhosis [19].

Complications of cirrhosis such as hepatic encephalopathy:

In the pre-transplant period, focus on prevention of hepatic decompensations cannot be emphasized enough. The mechanism of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is multifactorial but high levels of ammonia and inflammation related to dysbiosis is a prevailing theory [20]. In a sample of inpatients and outpatients with cirrhosis, there was a lower cirrhosis dysbiosis ratio (CDR) defined by Lachnospiraceae + Ruminococcaceae + Veillonellaceae / Enterobacteriaceae + Bacteroidaceae, and higher levels of Enterobacteriaceae, which predicted development of HE.

Ammonia-associated astrocyte swelling was negatively correlated with Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, and positively correlated with potentially pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae [20]. HE patients have worse cognitive function, higher ammonia levels and significantly increased inflammation and dysbiosis.

These changes further impair cognition and promote systemic inflammation. An open-label RCT found that FMT from a rationally selected donor leads to restoration of normal microbiota, reduced hospitalizations and improved cognitive testing in those with recurrent HE.

Still, there are risks associated with FMT such as the potential for bacteremia in immunocompromised patients to consider, however this was not observed in this small randomized trial [21], nor was there a transmission of antibiotic-resistance genes from the donor [22].

Therefore, in the pre-transplant setting, underlying liver disease severity and etiology, medications such as PPI use, host genetics, diet, comorbidities, active alcohol use, all work in concert and contribute to the microbiome composition and function [23].

Peri-operative changes:

The complexities of OLT include a long operative time that necessitates multiple blood products, can involve episodes of hypotension and possible post-operative bleeding. Lu et al. studied 12 patients with only HBV cirrhosis to determine the relationship between changes in fecal microbiome peri-operatively and the risk of infection, using DGGE (denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis) technique [24]. 8 patients had decreased microbiome diversity, and of these 8, 5 had infections within 30 days of surgery. The remaining patients that demonstrated stability in their microbiome had shorter lengths of stay, suggesting an interplay between the microbiome and clinical outcomes.

Infections, rejection, GVHD, recurrence of disease are feared complications of liver transplantation. Although immunosuppressant medications such as Tacrolimus and Mycophenolate Mofetil are key to preventing rejection, their effect on the immune system increases the risk of complications post-transplant. Tacrolimus has been associated with a decrease in microbiota diversity by a relative lower abundance of butyrate-producing organisms [25]. In turn, structural changes to the microbiome can ultimately affect pharmacodynamics of immunosuppressants [26]. There is a link between long-term tacrolimus use, opportunistic infections, increased endotoxin levels and gut permeability.

Early post-liver transplant period:

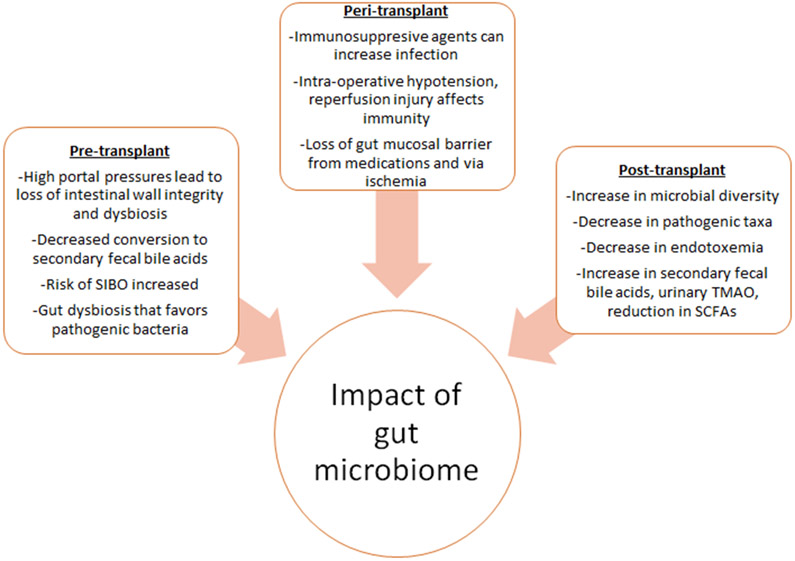

Factors related to the surgery including intra-operative hypotension, ischemia and reperfusion injury followed by use of these immunosuppressants can affect the humoral and cellular immunity profile (Figure 2). Most studies report a decrease in diversity immediately post-transplant with eventual near full recovery of the microbiome in the late post-transplant period. However, many factors can affect the outcomes of these studies. For instance, protocols for microbial analysis, analysis at different timepoints, transplant type and technique, medications administered, are some of the factors that should be considered when interpreting these studies.

Figure 2.

Impact of gut microbiome during liver transplant

Despite these variations, it is well-known that restoration of the microbiome composition and function, coupled with enriched dietary changes can improve overall health and quality of life. One study followed patients after transplant using cognitive testing using psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score (PHES), health related QOL, and stool microbiota analyses. They concluded that after transplant, there was an increase in microbial diversity, improvement in QOL and PHES scores, with a decrease in pathogenic taxa, as compared to pre-transplant. However, in patients with persistent cognitive impairment after transplant, there was a relative increase in Proteobacteria but less Firmicutes [27]. An extension of this study found that after transplant there was an increase in microbial diversity, decrease in pathogenic taxa and reduced endotoxemia, higher ratio of secondary to primary fecal bile acids, increase in urinary TMAO (trimethylamine-N-oxide) and reduction in short chain fatty acids [28]. OLT led to improvements in microbiota diversity and favorable functionality changes implicating recovery of the gut microbiome up to one-year post-transplant.

Effect of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria:

Gut bacteria are major reservoir of antibiotic-resistance genes, that are high in patients with cirrhosis and could lead to multi-drug resistant infections [29] . Annavajhala et al. prospectively studied 177 patients using 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples from pre-LT and throughout the one-year post-LT follow-up period [30]. This group reported that MDR bacteria colonization could predict decreased alpha-diversity irrespective of etiology of liver disease or prior exposure to antibiotics. Irrespective of diagnosis, there were significant changes in alpha and beta diversity of the gut microbiome in the peri-operative (week 1-3), early post-transplant (month 1-3) and late post-transplant (month 6-12) period compared to pre-LT. Low alpha-diversity was a marker for CRE colonization after LT. E. casselflavius and L. zeae could be markers for suboptimal microbiome health as these were higher in pre-LT patients with high MELD and CTP scores, and in those with VRE colonization. The loss of protective taxa such as F. prausnitzii, Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Bacteroidaceae, and an increase in pathogenic taxa such as Enterococcus and Enterobacteriaceae, were also described. Post-operative bleeding within a week of LT, bile leak and biliary stricture were independently associated with decreased diversity at the peri and post-LT phases. Furthermore, at different phases during the transplantation process, certain MDR predicted lower alpha diversity. CRE and VRE colonization, cephalosporin-resistant Enterococcus, CRE colonization alone, and VRE colonization alone, were associated with lower diversity in the pre, peri, early post, and late post-transplant period, respectively. Therefore, MDR colonization contributes to post-operative complications and may be predictive of decreased microbial diversity throughout the transplant timeline.

Effect of microbiome on rejection:

After transplant, there exists the possibility of rejection. Some of our understanding of the impact of microbiome on liver transplant is based on rat models [31]. After LT there are fewer Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in the feces, but Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcus were higher in rats that did not receive a transplant [32-34].

Patients with acute cellular rejection (ACR) had a higher relative abundance of Bacteroides, Enterobacteriaceae, Streptococcaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae, whereas Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Clostridiaceae, Ruminococcaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae were increased in none-ACR patients. Similarly, Ren and his colleagues [35] established rat OLT models to describe microbial profiles as potential biomarkers for ACR. The richness of species such as Firmicutes was decreased during ACR, whereas Bacteroidetes was significantly increased. This group also found a significant difference in microbiome composition at post-op day 3 and 7 in those with ACR compared to those without. All post-LT rat models had lower SDI, but there was a trend toward decreased microbiome diversity in ACR rats at day 7 compared to controls, specifically, less beneficial bacteria Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Lactobacillus, with an increase in Clostridium bolteae. Thus, dysbiosis can potentiate ACR and microbiome targeted interventions could be key to ACR prevention.

Interplay between the microbiome, infections, and probiotics:

Nearly two-thirds of orthotopic liver transplantations are complicated by infection, with bacterial infection being the most common and reported to range from 20-80% of all cases, with a high mortality rate of 13-36% [36]. Specific to bacteremia, higher levels of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecium, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus gallinarum have been implicated.

Two longitudinal studies of gut dysbiosis post-liver transplant describe conflicting results. A study by Sun et al. in 8 patients, at 3 months post-transplant did not see a difference in alpha diversity, but in terms of bacterial taxa there were notable increases in the taxonomic groups that had beneficial bacteria, and less pathogenic bacteria [37]. In contrast to this, Kato et al. found a decrease in the mean diversity index of 38 patients at 21 days after transplant but reported a gradual recovery of diversity at 2 months after surgery [38]. This group did not highlight specific microbiota changes but did correlate low SDI to ACR and blood stream infections.

Another study of 45 LT patients reported no differences in SDI at 6 months post-LT. However, they reported a reduction in pathogenic family Enterobacteriaceae and increases in potentially beneficial families Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae (Clostridiales cluster XIVa) [27]. 40 of these patients were analyzed separately in a follow-up study [27] and correlated SDI improvement with a reduction in endotoxin levels, increased conversion from primary to secondary bile acids creating an anti-inflammatory state.

Therefore, if improvement in diversity indices could reduce systemic inflammation and likelihood of infection, perhaps probiotics be potentially beneficial. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of patients receiving a four-strain probiotic preparation reported a significantly lower 30-day post-operative mortality rate and 90-day infection rates when compared to placebo [39]. This was further supported by two other studies, one using perioperative probiotics, and the other, probiotics with fiber [40-41]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of four studies exploring the impact of probiotics reported lower rates of infection, 7% in the probiotic group, compared to 35% in controls and decreased length of ICU stay by 1.41 days [42]. Lactobacillus was used in all probiotic formulations, while two used Bifidobacterium. This point was further corroborated by another study reporting an infection rate of 4.8% (probiotic) vs. 34.8% (control) p =.02, after administration of probiotics containing: Lactobacillus lactus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium bifidum. Probiotics may decrease endotoxemia, restore the gut barrier, and decrease ischemia-reperfusion injury [42-44]. However, at this stage, there is no formal recommendation to initiate probiotics post-transplant.

Impact on disease recurrence:

Though changes to the gut microbiome play a key role in the pathogenesis of specific etiologies of liver disease, less is known about its impact on disease recurrence after transplant. Many studies are observational, thus limiting their generalizability [46-50]. Further analyses are needed.

Future directions:

Microbial diversity and dysbiosis indices could serve as biomarkers to predict and prevent complications surrounding the liver transplantation period. Studies have offered probiotics, long-chain fatty acid supplementation, and even fecal microbial transplant (FMT) as potential interventions. Early microbiome-based interventions could prevent infection, rejection, disease recurrence, and improve overall survival. There could also be a role for increasing bacteria that convert short-chain fatty acids as well as primary to secondary bile acids. Dysbiosis leads to a decreased bile acid pool, increases gram-negative organisms, and ultimately increasing the burden of LPS and inflammation. Activation of bile acids via FXR can decrease ischemia-reperfusion injury. Administration of FXR agonists could be explored in the future.

To establish causality, data from the microbiome, structural and functional data need to be integrated, which remain difficult in human studies. Future comprehensive, multi-center studies using metagenomics are needed to create models that incorporate our existing knowledge with microbiome data to prognosticate, predict and prevent complications post-LT. Future research is needed to determine if compositional changes in microbiome are causative of post-LT complications or simply an association [51-52].

Conclusions:

The human microbiome consists of trillions of organisms that affect gut homeostasis. Metabolism of various substances including lipids, choline, and bile acids all contribute to hepatic immunity. Host adaption to the physiologic changes associated with cirrhosis, maladaptive stress responses to surgery and recovery in the post-transplant period, intersect with the gut microbiome in a highly complex and interdependent fashion.

Microbiome targets can improve outcomes of liver transplant and may serve as a surrogate marker of complications. As our knowledge continues to expand, we will be able to hopefully achieve personalized medicine with optimal outcomes.

Key points:

The interplay between the host and gut microbiota before, during and after liver transplantation is complex.

Improved understanding of this interplay will allow for microbiome-based targeted therapies that will prevent post-transplant complications and improve survival.

Emphasis should be placed on both functional and compositional microbiome changes in order to ultimately transfer this knowledge to the clinical setting.

Financial support and sponsorship:

Partly supported by VA Merit Review 2I0CX001076 and NCATS R21TR003095 to JSB

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

None

References:

- 1:Acharya C, Bajaj JS. Altered microbiome in patients with cirrhosis and complications. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019;17(2):307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2:Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, et al. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications. J Hepatol 2014;60:940–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3:Wu ZW, Ling ZX, Lu HF, et al. Changes of gut bacteria and immune parameters in liver transplant recipients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012;11:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4:Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, et al. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5:Grat M, Wronka KM, Krasnodebski M, et al. Profile of gut microbiota associated with the presence of hepatocellular cancer in patients with liver cirrhosis. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:1687–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6:Ponziani FR, Bhoori S, Castelli C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with gut microbiota profile and inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2019;69(1):107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7:Boursier J, Mueller O, Barret M, Machado M, Fizanne L, Araujo-Perez F, et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology 2016;63:764–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8:Jin M, Kalainy S, Baskota N, et al. Faecal microbiota from patients with cirrhosis has a low capacity to ferment non-digestible carbohydrates into short-chain fatty acids. Liver Int. 2019;39(8):1437–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9:Rau M, Rehman A, Dittrich M, et al. Fecal SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria in gut microbiome of human NAFLD as a putative link to systemic T-cell activation and advanced disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(10):1496–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10:Bajaj JS, Kakiyama G, Zhao D, Takei H, Fagan A, Hylemon P, et al. Continued alcohol misuse in human cirrhosis is associated with an impaired gut-liver axis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2017;41:1857–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11:Llopis M, Cassard AM, Wrzosek L, Boschat L, Bruneau A, Ferrere G, et al. Intestinal microbiota contributes to individual susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2016;65:830–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12:Llorente C, Jepsen P, Inamine T,Wang L, Bluemel S,Wang HJ, et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat Commun 2017;8:837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13:Pinzone MR, Celesia BM, Di Rosa M, Cacopardo B, Nunnari G. Microbial translocation in chronic liver diseases. Int J Microbiol 2012;2012:694629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14:Mutlu EA; Gillevet PM; Rangwala H; Sikaroodi M; Naqvi A; Engen PA; Kwasny M; Lau CK; Keshavarzian A Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2012, 302, G966–G978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15:Tang R, Wei Y, Li Y, Chen W, Chen H, Wang Q, et al. Gut microbial profile is altered in primary biliary cholangitis and partially restored after UDCA therapy. Gut 2018;67:534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16:Wei Y, Li Y, Yan L, et al. Alterations of gut microbiome in autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2020;69(3):569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17:Inoue T, Nakayama J, Moriya K, Kawaratani H, Momoda R, Ito K, et al. Gut dysbiosis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18:Heidrich B, Vital M, Plumeier I, Doscher N, Kahl S, Kirschner J, et al. Intestinal microbiota in patients with chronic hepatitis C with and without cirrhosis compared with healthy controls. Liver Int 2018;38:50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19:Lu H,Wu Z, Xu W, Yang J, Chen Y, Li L. Intestinal microbiota was assessed in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Intestinal microbiota of HBV cirrhotic patients. Microb Ecol 2011;61:693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20:Ahluwalia V, Betrapally NS, Hylemon PB, White MB, Gillevet PM, Unser AB, et al. Impaired gut-liver-brain axis in patients with cirrhosis. Sci Rep 2016;6:26800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21:Bajaj JS, Kassam Z, Fagan A, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant from a rational stool donor improves hepatic encephalopathy: A randomized clinical trial: Bajaj et al. Hepatology. 2017;66(6):1727–1738.Il [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bajaj JS, Shamsaddini A, Fagan A, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant in cirrhosis reduces gut microbial antibiotic resistance genes: analysis of two trials. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5(2):258–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23:Qin N, Yang F, Li A, Prifti E, Chen Y, Shao L, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014;513:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24:Lu H, He J, Wu Z, et al. Assessment of microbiome variation during the perioperative period in liver transplant patients: a retrospective analysis. Microb Ecol. 2013;65:781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25:Toral M, Romero M, Rodriguez-Nogales A, et al. Lactobacillus fermentum improves tacrolimus-induced hypertension by restoring vascular redox state and improving eNOS coupling. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:e1800033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang J-W, Ren Z-G, Lu H-F, et al. Optimal immunosuppressor induces stable gut microbiota after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(34):3871–3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27:Bajaj JS, Fagan A, Sikaroodi M, et al. Liver transplant modulates gut microbial dysbiosis and cognitive function in cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2017;23(7):907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28:Bajaj JS, Kakiyama G, Cox IJ, et al. Alterations in gut microbial function following liver transplant. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:752–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29:Shamsaddini A, Gillevet PM, Acharya C, et al. Impact of antibiotic resistance genes in gut microbiome of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(2):508–521.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30:Annavajhala MK, Gomez-Simmonds A, Macesic N, et al. Colonizing multidrug-resistant bacteria and the longitudinal evolution of the intestinal microbiome after liver transplantation. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31:Wang W, Xu S, Ren Z, Jiang J, Zheng S. Gut microbiota and allogeneic transplantation. J Transl Med. 2015;13(1):275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32:Yu MH, Yu XL, Chen CL, Gao LH, Mao WL, Yan D, Chen Y, Sheng JF, Li LJ, Zheng SS. The change of intestinal microecology in rats after orthotopic liver transplantation. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;46:1139–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33:Lu H, He J, Wu Z, et al. Assessment of microbiome variation during the perioperative period in liver transplant patients: a retrospective analysis. Microb Ecol. 2013;65:781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34:Jiang JW, Ren ZG, Cui GY, Zhang Z, Xie HY, Zhou L. Chronic bile duct hyperplasia is a chronic graft dysfunction following liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1038–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35:Ren Z, Jiang J, Lu H, Chen X, He Y, Zhang H, Xie H, Wang W, Zheng S, Zhou L. Intestinal microbial variation may predict early acute rejection after liver transplantation in rats. Transplantation. 2014;98:844–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36:Mu Jingzhou, Chen Qiuyu, Zhu Liang, Wu Yunhong, Liu Suping, Zhao Yufei & Ma Tonghui (2019) Influence of gut microbiota and intestinal barrier on enterogenic infection after liver transplantation, Current Medical Research and Opinion, 35:2, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37:Sun LY, Yang YS, Qu W, et al. Gut microbiota of liver transplantation recipients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38:Kato K, Nagao M, Miyamoto K, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the intestinal microbiota in liver transplantation. Transplant Direct. 2017;3:e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39:Grat M, Wronka KM, Lewandowski Z, et al. Effects of continuous use of probiotics before liver transplantation: a randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr 2017;36:1530–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40:Rayes N, Seehofer D, Theruvath T, et al. Supply of pre- and probiotics reduces bacterial infection rates after liver transplantation—a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Transplant 2005;5:125–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41:Zhang Y, Chen J, Wu J, et al. Probiotic use in preventing postoperative infection in liver transplant patients. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2013;2:142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42:Sawas T, Al Halabi S, Hernaez R, et al. Patients receiving prebiotics and probiotics before liver transplantation develop fewer infections than controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1567–1574.e1563; quiz e1143–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43:Ali JM, Davies SE, Brais RJ, et al. Analysis of ischemia/reperfusion injury in time-zero biopsies predicts liver allograft outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44:Xing HC, Li LJ, Xu KJ, et al. Protective role of supplement with foreign Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in experimental hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45:Ren Z, Cui G, Lu H, et al. Liver ischemic preconditioning (IPC) improves intestinal microbiota following liver transplantation in rats through 16s rDNA-based analysis of microbial structure shift. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46:Xie G, Wang X, Liu P, et al. Distinctly altered gut microbiota in the progression of liver disease. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19355–19366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47:Dapito DH, Mencin A, Gwak GY, et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48:Schrumpf E, Kummen M, Valestrand L, et al. The gut microbiota contributes to a mouse model of spontaneous bile duct inflammation. J Hepatol. 2017;66:382–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49:Kummen M, Holm K, Anmarkrud JA, et al. The gut microbial profile in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis is distinct from patients with ulcerative colitis without biliary disease and healthy controls. Gut. 2017;66:611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50:Zhang J, Ren FG, Liu P, et al. Characteristics of fecal microbial communities in patients with non-anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8217–8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51:Andrade-Oliveira V, Amano MT, Correa-Costa M, et al. Gut bacteria products prevent AKI induced by ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1877–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52:Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB, et al. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]