ABSTRACT

Background

Post-traumatic headache (PTH) is a commonly experienced symptom after mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). Blast injury– or blunt injury–related mechanisms for mTBI in veterans can also affect musculoskeletal structures in the neck, resulting in comorbid neck pain (NP). However, it is unknown whether the presence of comorbid NP may be associated with a different pattern of headache symptoms, physical functioning, or emotional functioning compared to those without comorbid NP. The purpose of this study is to examine the role of comorbid NP in veterans with mTBI and PTH.

Design and Methods

This was a cross-sectional investigation of an existing dataset that included 33 veterans who met inclusion criteria for PTH after mTBI. Standardized measures of headache severity and frequency, insomnia, fatigue, mood disorders, and physical and emotional role function were compared between groups with and without comorbid NP.

Results

The majority of participants with PTH reported comorbid NP (n = 22/33, 67%). Those with comorbid NP experienced more headache symptoms that were severe or incapacitating, as compared to mild or moderate for those without NP (φ = 0.343, P = .049); however, no differences in headache frequency (φ = 0.231, P = .231) or duration (φ = 0.129, P = .712) were observed. Participants with comorbid NP also reported greater insomnia (d = 1.16, P = .003) and fatigue (d = 0.868, P = .040) as well as lower physical functioning (d = 0.802, P = .036) and greater bodily pain (d = 0.762, P = .012). There were no differences in anxiety, depression, mental health, emotional role limitations, vitality, or social functioning between those with and without comorbid NP (d ≤ 0.656, P ≥ .079).

Conclusions

A majority of veterans with mTBI and PTH in our sample reported comorbid NP that was associated with greater headache symptom severity and physical limitations, but not with mood or emotional limitations. Preliminary findings from this small convenience sample indicate that routine assessment of comorbid NP and associated physical limitations should be considered in veterans with mTBI and PTH.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 1.7 million people in the United States require medical attention for traumatic brain injury (TBI) yearly, with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) being most prevalent.1 Common symptoms of mTBI include headaches, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, mood and sleep disturbances, and cognitive impairments. These symptoms are refractory to treatment in nearly half of those who sustain an mTBI, developing into a chronic postconcussive syndrome (PCS) that can persist for years after the traumatic injury.2 Persistent post-traumatic headache (PTH), defined as a head injury–induced headache lasting for greater than 3 months,3 is the most common symptom of PCS, with prevalence rates averaging 55%-60% across studies.4,5

Military service members and veterans have a high risk of exposure to TBI, and nearly 40% of those with TBI report PTH.6,7 While blunt injuries are more frequent in nondeployment settings, blast-related injuries are the most common cause of TBI because of high exposure to combat and artillery.8 One often overlooked feature of blast injury– or blunt injury–induced TBI is concurrent damage to surrounding tissues such as cervical musculoskeletal structures, which in many ways resembles whiplash injury.9 In fact, neck injury is one of the leading causes of medical evacuation of military personnel from U.S. operations.10 Although little is known about the relationship between neck injury and PTH in mTBI veterans, the negative impact of concurrent neck injury and headache symptoms has been well established in non-TBI civilian populations.11 For example, the presence of comorbid neck pain (NP) with migraine has been shown to be a significant predictor of disability and is associated with increased headache frequency, intensity, and duration.12 In addition, those experiencing migraine or PTH report higher rates of concurrent NP than those without.10,13 The veteran population is particularly unique in this regard given the high operational stressors both physically and psychosocially that may impact symptomology and subsequent treatment.

One clinical barrier to recovery in those with PTH is that high-quality evidence to guide specific interventions is lacking. For example, treatments for both PTH and migraine headaches include a wide spectrum of interventions including pharmacological management, nerve blocks, neurostimulation, physical therapy, injections, and even surgery.9 Clinically, PTH often resembles migraine in its presentation and is therefore managed similarly despite differing mechanisms.14 As such, it is not surprising that clinical outcomes of PTH treatment are highly variable and suboptimal.10

Investigating the influence of comorbid NP on physical and emotional functioning among veterans with PTH is necessary to inform clinical management of PTH and fills an important gap in the literature addressing the military population. In this study, we aim to compare the severity and functional impact of PTH in U.S. veterans with and without comorbid NP following mTBI. We hypothesize that those with PTH and comorbid NP will present with greater headache impairments and reduced physical and emotional functioning as compared to those without NP.

METHODS

Participants

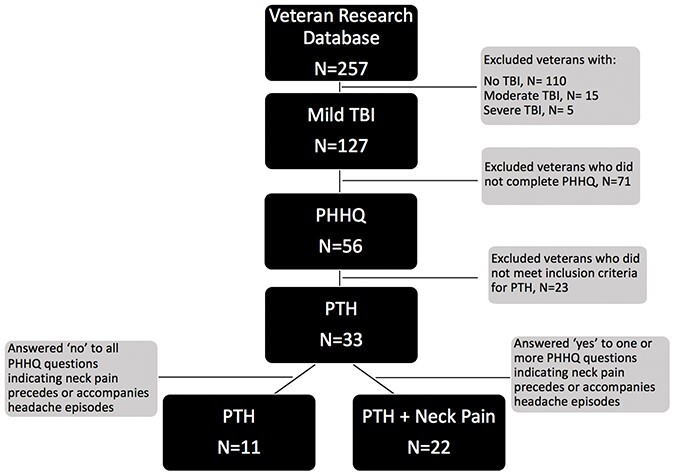

This was a cross-sectional secondary analysis of a database from a prior study.15,16 The database included 257 military veterans with and without TBI who were recruited between 2010 and 2018 from the VA San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS) and surrounding community. The participants included in this database were on average 31.9 (7.9) years old, 80.8% male, and had predominantly served in Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, including Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn. Of this database, 145 participants reported a history of TBI (87.5% mild, 9.6% moderate, and 2.7% severe), with the majority of those participants (55.7%) having experienced a blast-related mechanism of injury. Since the current analyses represent a retrospective subsample of those with PTH after mTBI, sample size was determined by the number of individuals who met a priori inclusion criteria for the present study based on presence of mTBI (n = 127) and completion of questionnaires of interest (n = 56) (Fig. 1). The VASDHS institutional review board approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

FIGURE 1.

Selection criteria for PTH and PTH + NP study groups sampled from existing veteran research database. NP, neck pain; PHHQ, Patient Headache History Questionnaire; PTH, post-traumatic headache; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

An eligibility screening was conducted on all participants before study enrollment.17 Participant demographics, relevant military and medical history, were collected in a clinical interview. Details regarding head injuries were obtained using a modified version of the VA Semi-Structured Clinical Interview for TBI.18 For those reporting one or more TBIs, information was gathered about the number of TBIs, months since most recent TBI, and mechanism of each TBI injury (i.e., blunt vs. blast). Participants with both mechanisms of injury were included in the cohort. Participants were excluded if they had a current or previous diagnosis of a severe mental disorder (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder); were actively suicidal and had a history of significant neurological medical conditions such as epilepsy or multiple sclerosis; or reported current substance abuse or dependence as determined by initial diagnostic clinical interview and verified by a Rapid Response 10-drug Test Panel and toxicology screening.

Participants were included in the present study only if they met the following self-report criteria for mTBI as defined by the DVA and DoD17: (1) loss of consciousness ≤30 minutes, (2) alteration of consciousness ≤24 hours, and/or (3) post-traumatic amnesia ≤24 hours. Participants were further included if they reported headaches after experiencing an mTBI in the clinical interview and completed the Baylor Health Patient Headache History Questionnaire (PHHQ).19 This clinical questionnaire collected information on headache severity, frequency, duration, and location as well as associated NP symptoms. Participants in the cohort were split into two groups based on the presence (PTH + NP) or the absence (PTH) of comorbid NP. Individuals with both PTH and comorbid NP (PTH + NP) were identified based on an affirmative response to one or more of the following questions on the PHHQ: “My headaches occur in my neck,” “When I have a headache I also experience pain down the front or side of my neck,” and/or “I have pain in my neck.” Patient demographics included age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, years of education, military branch, and employment status.

Outcome Measures

Headache Impairment Measures

Headache characteristics were assessed using individual survey items from the PHHQ. Owing to the small sample size and large number of response options for individual items in this clinical questionnaire, responses were collapsed into dichotomous (nominal) outcomes for headache severity, frequency, and duration and described in terms of frequency. Severity of headaches was assessed by the PHHQ question “My headaches if I don’t treat them effectively are usually…” with response options of (1) mild or moderate or (2) severe or incapacitating. Frequency of headaches was assessed by the PHHQ question “My headaches usually occur…” with response options of (1) daily or weekly or (2) less frequent than weekly. Duration of headaches was assessed by the PHHQ question “My headaches if I don’t take medication will usually last…” with response options of (1) less than 1 day or (2) more than 1 day. Headache location was assessed as an ordinal variable by the PHHQ question “My headaches occur…” with response options of (1) only on one side at a time, (2) as a band around my head, or (3) over my entire head.

Physical Health Measures

Mean (SD) measures of physical health and function included insomnia, fatigue, general health, bodily pain, physical functioning, and physical role limitations. Insomnia was measured using the Insomnia Severity Index, which is a seven-item questionnaire quantifying insomnia severity that has been validated in veterans with a history of TBI.20 Insomnia Severity Index scores range from 0-28 points, with ≥11 points indicating clinically significant insomnia.20 Fatigue was measured using the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, which is a 29-item questionnaire ranging from 0-84 points that assesses the impact of fatigue on cognitive, physical, and psychosocial functioning and has been validated in veterans with mTBI.21 A threshold of ≥29 points has been suggested to represent clinically significant fatigue.21 Physical health was measured using the physical functioning and physical role limitations subscales of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 is a 36-item quality of life survey that determines patient health status with physical health (general health, bodily pain, physical functioning, and physical role limitations) and mental health (vitality, social functioning, and emotional role limitations) subscales. Each of the eight subscales are scored separately and range from 0-100, with higher scores indicating better health and lower scores indicating more limitation.22

Emotional Health Measures

Emotional health metrics assessed depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, mental health, vitality, social functioning, and emotional role limitations. Depression and anxiety were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), respectively. The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report questionnaire with good reliability and validity that is scored on a scale from 0-63 points and has been recommended for evaluation of depression in the TBI population.23 Established score ranges for interpreting the severity of depression are as follows: 17-20 points indicates borderline clinical depression, 21-30 points indicates moderate depression, and over 40 points indicates severe depression.24 The BAI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire with excellent reliability and validity.25 It is scored on a scale of 0-63 points, with scores over 36 points indicating high levels of anxiety.25 The presence and severity of PTSD were measured using the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M). The PCL-M is a 17-item self-report measure that is scored on a scale from 0-85 points, with scores above 50 points indicating clinically significant PTSD symptoms.26 Mental health, vitality, social functioning, and emotional role limitations were calculated from the mental component subscales of the SF-36 as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Independent two-tailed t-tests were used to compare means between PTH and PTH + NP groups for continuous variables. Chi-square or fisher exact tests were used to compare proportions between groups for ordinal or dichotomous variables. P values of <.05 were considered significant. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d for independent t-test comparisons, phi (φ) coefficient for dichotomous chi-square comparisons, and Cramer’s V for ordinal comparisons. All data were examined for outliers and checked for normality. All statistical analyses were performed on SPSS software version 26.0.0 (IBM Corp., 2019).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

A total of 33 participants met inclusion criteria for this study, with the majority (n = 22/33, 66.7%) reporting concurrent NP. Participant characteristics are detailed in Table I. The majority of participants were Caucasian (n = 19/33, 57.6%), with no significant difference in the ethnic distribution between groups (V = 0.371, P = .196). The veteran cohort was predominantly male (n = 28/33, 84.8%), with no significant difference in sex between groups (φ = 0.299, P = .144). The PTH + NP group tended to have more Navy veterans as compared to the PTH group with a moderate effect size (V = 0.403, P = .069). Just over half of the cohort was employed (n = 17/33, 51.5%), with no differences in marital status (φ = 0.224, P = .197), education (d = 0.063, P = .792), or employment status between groups (V = 0.043, P = .805). The PTH + NP group tended to report a greater number of mTBIs compared with the PTH group with a moderate effect size (d = 0.709, P = .071), and no differences in time since injury (d = 0.298, P = .371), injury mechanism (φ = 0.163, P = .181), or mTBI diagnostic criteria characteristics (φ = 0.129, P = .458).

TABLE I.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| PTH | PTH + neck pain | P-value | Effect size | ||

| Age | Years | 34.3 (8.0) | 34.6 (7.9) | .902 | 0.046 |

| Sex | Male | 11 (100.0%) | 17 (77.3%) | .144 | 0.299 |

| Female | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (22.7%) | |||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 4 (36.4%) | 15 (68.2%) | .196 | 0.371 |

| African American | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (4.5%) | |||

| Hispanic | 5 (45.5%) | 5 (22.7%) | |||

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.5%) | |||

| Military branch | Navy | 1 (9.1%) | 11 (50.0%) | .069 | 0.403 |

| Army | 5 (45.5%) | 6 (27.3%) | |||

| Marines | 5 (45.5%) | 5 (22.7% | |||

| Marital status | Single | 3 (27.3%) | 12 (54.5%) | .197 | 0.224 |

| Married/cohabitating | 7 (63.6%) | 10 (45.5%) | |||

| Education | Years | 14.3 (2.1) | 14.1 (2.0) | .792 | 0.063 |

| Employment status | Employed | 6 (54.5%) | 11 (50.0%) | .805 | 0.043 |

| Unemployed | 5 (45.5%) | 11 (50.0%) | |||

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | Points | 17.9 (16.3) | 23.1 (12.9) | .326 | 0.357 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | Points | 13.1 (17.0) | 13.5 (9.0) | .928 | 0.030 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist | Mean score | 42.6 (22.4) | 46.4 (16.5) | .587 | 0.191 |

| Number of mTBIs | Count | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.3) | .071 | 0.709 |

| Time since most recent mTBI | Months | 94.5 (79.5) | 75.7 (40.2) | .371 | 0.298 |

| mTBI mechanism | Blast | 6 (54.5%) | 17 (77.3%) | .181 | 0.163 |

| Blunt | 5 (45.5%) | 5 (22.7%) | |||

| mTBI criteria | Loss of consciousness | 7 (63.6%) | 11 (50.0%) | .458 | 0.129 |

| Alteration of consciousness | 4 (36.4%) | 11 (50.0%) |

Values reported as mean (SD) or n (% group total).

Abbreviations: PTH, post-traumatic headache; TBI, mild traumatic brain injury.

Headache Impairments

Headache severity was greater in the PTH + NP group than the PTH group with a moderate effect size (φ = 0.343, P = .049); the majority of participants with concurrent NP reported severe or incapacitating headaches, whereas those without NP reported only mild or moderate headaches. There were no differences in headache duration (φ = 0.129, P = .712) or frequency (φ = 0.231, P = .231) between groups, and no clear pattern emerged for differences in headache location (V = 0.247, P = .596) between those with and without concurrent NP (Table II).

TABLE II.

Headache Characteristics in Participants With and Without Concurrent Neck Pain

| PHHQ questions | Response category | PTH | PTH + Neck pain | P-values | Effect size |

| Headache severity My headaches if I don’t treat them effectively are usually |

Mild or moderate Severe or incapacitating |

8 (72.7%) 3 (27.3%) |

8 (36.6%) 14 (63.6%) |

.049 | 0.343 |

| Headache frequency My headaches usually occur |

Daily or weekly Less frequent than weekly |

3 (27.3%) 5 (45.5%) |

13 (59.1%) 7 (31.8%) |

.231 | 0.231 |

| Headache duration My headaches if I don’t take medication will usually last |

<1 day ≥1 day |

7 (63.6%) 4 (36.4%) |

11 (50.0%) 11 (50.0%) |

.712 | 0.129 |

| Headache location My headache occurs |

Only on one side at a time As a band around my head |

2 (18.2%) 5 (45.5%) |

5 (22.7%) 4 (18.2%) |

.596 | 0.247 |

| Over my entire head | 3 (27.3%) | 6 (27.3%) |

Values reported as mean (SD) or n (% group total).

PTH, post-traumatic headache.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Physical Health Measures

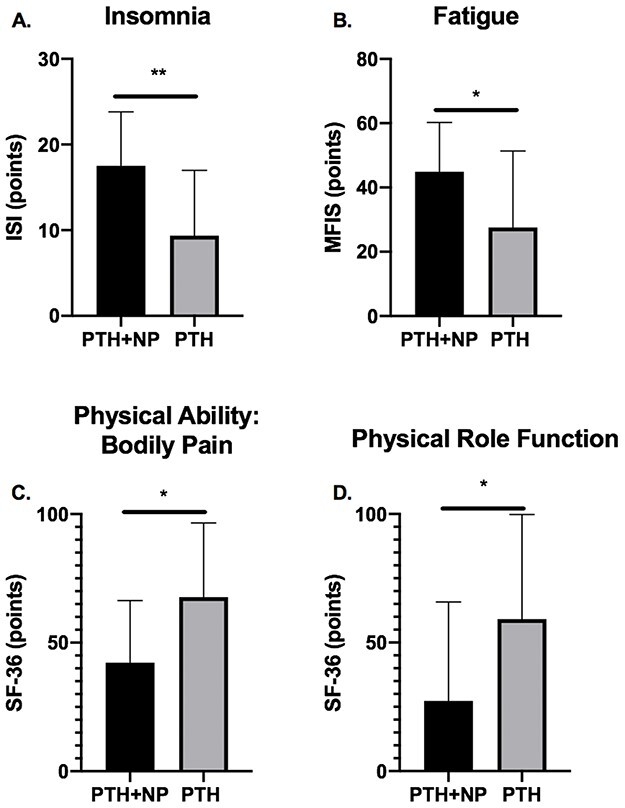

The majority of physical health measures differed significantly between groups with large effect sizes. PTH + NP participants reported clinically relevant insomnia (17.5 ± 6.3) compared with PTH only participants (9.4 ± 7.6; d = 1.16, P = .003, Fig. 2A), who reported subclinical insomnia. Similarly, fatigue in the PTH + NP group exceeded the threshold for clinically relevant fatigue (44.8 ± 22.3) and was significantly higher than in the PTH group (21.2 ± 35.7; d = 0.868, P = .040, Fig. 2B). The PTH + NP group reported lower physical function because of bodily pain (42.2 ± 24.2) than the PTH group (67.7 ± 28.8; d = 0.762, P = .012, Fig. 2C), and lower physical health–related role function (27.3 ± 38.5) than the PTH group (59.1 ± 40.7; d = 0.802, P = .036, Fig. 2D). SF-36 general health (d = 0.337, P = .389) and physical functioning (d = 0.701, P = .084) did not differ between groups.

FIGURE 2.

Bars indicate mean (SD) scores for the PTH with NP (PTH + NP, n = 22) and PTH with no NP (PTH, n = 11) groups. (A) Insomnia Severity Index scores range from 0-28, with higher scores indicating increased insomnia severity. (B) Modified Fatigue Impact Scale Scores range from 0-84, with higher scores indicating increased fatigue. (C) SF-36 Bodily Pain domain scores, with lower scores indicating lower physical ability because of bodily pain. (D) SF-36 Physical Role Function domain scores, with lower scores indicating lower physical role functioning. **P < .01, *P < .05. MFIS, Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; NP, neck pain; PTH, post-traumatic headache; SF-36, 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Emotional Health Measures

There were no significant differences in depression (BDI-II, d = 0.357, P = .326), anxiety (BAI, d = 0.357, P = .928), or PTSD (PCL-M, d = 0.191, P = .587) between groups. Similarly, there were no group differences in the SF-36 mental health (d = 0.279, P = .429), emotional role limitations (d = 0.349, P = .343), or vitality (d = 0.523, P = .151) subscales, but there was a trend for reduced social functioning in the PTH + NP group (d = 0.646, P = .079).

DISCUSSION

The majority of veterans with mTBI and PTH in our sample experienced concurrent NP that was associated with more severe headaches, insomnia, and fatigue, as well as greater physical limitations because of bodily pain and reduced physical role functioning compared with those without NP. Importantly, these physical limitations occurred despite similar mood profiles and emotional functioning between groups. Overall, these findings support our hypothesis that veterans with PTH and comorbid NP experience more severe headaches and subsequent physical limitations, but are contrary to our hypothesis regarding the relationship between comorbid NP and emotional functioning. This is the first study to show that comorbid NP is associated with more severe headache symptoms and poor physical health and role functioning in veterans with PTH following mTBI.

Despite the limited size of our cohort, the prevalence rate of 66.7% for comorbid NP is consistent with prevalence rates of 38%-67% for NP reported in larger veteran and civilian mTBI samples.4,27–29 These rates mirror the prevalence of NP in primary headache disorders, such as migraine, which range between 40% and 76%.12,30 To our knowledge, no previously published study reporting NP prevalence rates in individuals with mTBI has compared health or function between those with and without this common comorbidity.

The relationship between NP and headache impairments has not been well elucidated in the mTBI population. Existing studies suggest that the majority of individuals with mTBI experience daily headaches of moderate severity, with average pain rating scores ranging from 4-6 on a 10-point scale.4,27 Our results indicate that the majority of individuals with comorbid NP reported severe or incapacitating headaches compared with only mild or moderate severity in those without, suggesting that NP significantly compounds headache symptom intensity in this population, although the effect size was only moderate for this variable. Despite this difference, we found no association between NP and headache frequency or duration, which is in contrast to studies of migraine reporting positive associations between NP and headache frequency.12,30,31

One interesting finding of our study was that the location of headache was nonspecific in our PTH population and did not differ between groups. Primary and cervicogenic headaches are often closely tied to NP. Cervicogenic headache typically presents with unilateral symptoms and is by definition caused by a disorder of the cervical spine and its component bony, disc, and/or soft tissue elements.3,32 A similar presentation in the PTH + NP group would suggest that similar treatment approaches targeting cervical pain generators may be indicated for both PTH and cervicogenic headaches. However, the variation in phenotype observed here suggests the need for a different clinical approach and perhaps supports the current clinical practice to treat PTH similarly to migraine headaches, which are thought to be centrally mediated. Elevated fatigue and insomnia in the PTH + NP group further support the hypothesis that comorbid NP may result from heightened central sensitivity in some individuals with mTBI and PTH.33 Although there is some evidence that impaired descending pain modulation may contribute to PTH,34 future studies are needed to identify the relative contribution of peripheral and central mechanisms to greater symptom severity among those with PTH and comorbid NP.

Comorbid NP is associated with headache impairments related to overall physical health, including sleep, fatigue, mobility, and strength, and mirrors findings from studies in other headache populations.30,31,35–42 For example, in mTBI, sleep disturbances are common, occurring in nearly half of individuals with effects lasting from months to years after the original injury and increasing with injury severity.36,37,43 Similar relationships exist in individuals with persistent headaches,38,39 and even chronic NP.44 Fatigue is another common symptom among those with mTBI, which is strongly associated with disability and can persist for months or years following the injury.36,45 Those with NP of any source tend to report higher levels of fatigue when compared to their asymptomatic counterparts.41 As such, it is not surprising that our results reflect that a combination of mTBI, PTH, and NP is characterized by a more severe phenotype than any given symptom in isolation. Moreover, the presence of NP has been shown to be associated with physical impairments (e.g., mobility and strength)42 as well as disability in individuals with migraine headaches,30,31 although other research has failed to demonstrate a significant relationship with participation restrictions such as missing days of work or social events.42 Although these data are largely limited to populations that have not experienced traumatic mechanisms of injury, the trend in the literature toward increased the physical disability among those with NP coincides with our findings of overall reduced ability on the SF-36 physical health subscales.

Interestingly, our measures related to mood and emotional health did not distinguish between groups. This was surprising and contrary to our initial hypothesis that comorbid NP would heighten emotional distress in those with PTH. The similarity of mood and emotional health ratings between groups suggest that differences observed in headache severity and physical health domains were not confounded by differences in emotional health or a tendency of the PTH + NP group to endorse greater distress generally.

Study Limitations

A limited number of veterans met a priori inclusion criteria for PTH after mTBI in this secondary analysis. However, the small sample size is comparable to other studies of PTH in mTBI populations evaluating impairment-based measures and physical health, and effect sizes were large for variables related to physical function. Although preliminary, findings from this small convenience sample indicate that routine assessment of comorbid NP and associated physical limitations should be considered in veterans with mTBI and PTH. Another limitation was the restriction of our retrospective analysis to variables of interest that were collected in the original study. As such, our operational definition of NP was based on a small set of questions from the PHHQ, which limited our ability to characterize the nature and severity of NP symptoms. Finally, as typical of cross-sectional designs, our study cannot determine causality. Future research is needed to prospectively evaluate the mechanisms and impact of comorbid NP on headache impairments, physical, and emotional health in this population.

CONCLUSION

Neck pain is a common comorbidity of PTH and has several functional implications. In this sample of veterans with mTBI and PTH, those with comorbid NP experienced greater headache severity and poorer physical health and role functioning, despite no differences in emotional health compared with those without comorbid NP. Awareness of these associated impairments may be a valuable contribution to direct future research and clinical practices. Further research that prospectively investigates the mechanisms and impact of comorbid NP on headache impairments and physical and psychosocial functioning is needed in this population, specifically with regard to directing assessment and treatment approaches for PTH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would also like to acknowledge Lisa Delano-Wood PhD for her contribution in generating data and funding for the original database used for this analysis.

Contributor Information

Bahar Shahidi, PT, PhD, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA.

Robyn W Bursch, BS, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Jennifer S Carmel, BS, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Ashleigh C Carranza, BS, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Kelsey M Cooper, BS, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Jayme V Lee, BS, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Colleen N O’Connor, BS, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Scott F Sorg, PhD, Veterans Association San Diego Healthcare System, Research Service, San Diego, CA 92161, USA; Veterans Association San Diego Healthcare System, Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health, San Diego, CA 92161, USA.

Katrina S Maluf, PT, PhD, Department of Physical Therapy, San Diego State University, School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences, San Diego, CA 92182, USA.

Dawn M Schiehser, PhD, Veterans Association San Diego Healthcare System, Research Service, San Diego, CA 92161, USA; Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA.

FUNDING

Funding from the following sources contributed to this project: National Institutes of Health R21NS109852; VA Clinical Science Research & Development Career Development Award (IK2CX001508 & 2-065-10S), and Department of Defense Award W81XWH-10-2-0169.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflicts are declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Theeler B, Lucas S, Riechers RG II, Ruff RL: Post-traumatic headaches in civilians and military personnel: a comparative, clinical review. Headache 2013; 53(6): 881-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwab K, Terrio HP, Brenner LA, et al. : Epidemiology and prognosis of mild traumatic brain injury in returning soldiers: a cohort study. Neurology 2017; 88(16): 1571-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2013; 33(9): 629-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. King PR, Beehler GP, Wade MJ: Self-reported pain and pain management strategies among veterans with traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Mil Med 2015; 180(8): 863-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nampiaparampil DE: Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. JAMA 2008; 300(6): 711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larsen EL, Ashina H, Iljazi A, et al. : Acute and preventive pharmacological treatment of post-traumatic headache: a systematic review. J Headache Pain 2019; 20(1): 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lazarus R, Helmick K, Malik S, Gregory E, Agimi Y, Marion D: Continuum of the United States military’s traumatic brain injury care: adjusting to the changing battlefield. Neurosurg Focus 2018; 45(6): E15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenfeld JV, McFarlane AC, Bragge P, Armonda RA, Grimes JB, Ling GS: Blast-related traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12(9): 882-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conidi FX: Interventional treatment for post-traumatic headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2016; 20(6): 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen SP, Kapoor SG, Nguyen C, et al. : Neck pain during combat operations: an epidemiological study analyzing clinical and prognostic factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35(7): 758-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bogduk N, Govind J: Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8(10): 959-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calhoun AH, Ford S, Millen C, Finkel AG, Truong Y, Nie Y: The prevalence of neck pain in migraine. Headache 2010; 50(8): 1273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lampl C, Rudolph M, Deligianni CI, Mitsikostas DD: Neck pain in episodic migraine: premonitory symptom or part of the attack? J Headache Pain 2015; 16(80): 566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Capi M, Pomes LM, Andolina G, Curto M, Martelletti P, Lionetto L: Persistent post-traumatic headache and migraine: pre-clinical comparisons. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(7): 2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bomyea J, Lang AJ, Delano-Wood L, et al. : Neuropsychiatric predictors of post-injury headache after mild-moderate traumatic brain injury in veterans. Headache 2016; 56(4): 699-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schiehser DM, Delano-Wood L, Jak AJ, et al. : Validation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015; 30(2): 116-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group : VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009; 46(6): Cp1-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vanderploeg RD, Groer S, Belanger HG: Initial developmental process of a VA semistructured clinical interview for TBI identification. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012; 49(4): 545-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Center BN: Patient Headache History Questionnaire. 2012. Available at https://www.baylorhealth.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/Documents_Dallas/Headache%20Center/Patient%20Headache%20History%20Questionnaire.pdf; accessed 2019.

- 20. Kaufmann CN, Orff HJ, Moore RC, Delano-Wood L, Depp CA, Schiehser DM: Psychometric characteristics of the Insomnia Severity Index in veterans with history of traumatic brain injury. Behav Sleep Med 2019; 17(1): 12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schiehser DM, Delano-Wood L, Jak A, et al. : Validation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015; 30(2): 116-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ware JE Jr, Gandek B: Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51(11): 903-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaninotto AL, Vicentini JE, Fregni F, et al. : Updates and current perspectives of psychiatric assessments after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 2016; 7: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beck A, Steer R, Brown G: Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II); 1996, San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA: An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56(6): 893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McDonald SD, Calhoun PS: The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD checklist: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30(8): 976-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lahz S, Bryant RA: Incidence of chronic pain following traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77(9): 889-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Uomoto JM, Esselman PC: Traumatic brain injury and chronic pain: differential types and rates by head injury severity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74(1): 61-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. King PR, Wade MJ, Beehler GP: Health service and medication use among veterans with persistent postconcussive symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 2014; 202(3): 231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ford S, Calhoun A, Kahn K, Mann J, Finkel A: Predictors of disability in migraineurs referred to a tertiary clinic: neck pain, headache characteristics, and coping behaviors. Headache 2008; 48(4): 523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Florencio L, Chaves T, Carvalho G, et al. : Neck pain disability is related to frequency of migraine attacks: a cross-sectional study. Headache 2014; 54(7): 1203-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biondi D: Cervicogenic headache: a review of diagnostic and treatment strategies. J Am Osteopathic Assoc 2005; 105(4 Suppl 2): 16S-22S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ruff RL, Blake K: Pathophysiological links between traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic headaches. F1000Res 2016; 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Defrin R, Riabinin M, Feingold Y, Schreiber S, Pick CG: Deficient pain modulatory systems in patients with mild traumatic brain and chronic post-traumatic headache: implications for its mechanism. J Neurotrauma 2015; 32(1): 28-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Afshar S, Shahidi S, Rohani AH, Komaki A, Asl SS: The effect of NAD-299 and TCB-2 on learning and memory, hippocampal BDNF levels and amyloid plaques in streptozotocin-induced memory deficits in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018; 235(10): 2809-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schiehser DM, Delano-Wood L, Jak AJ, et al. : Predictors of cognitive and physical fatigue in post-acute mild-moderate traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2017; 27(7): 1031-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hj Ja O, Gregory AM, Colón CC. et al. : Sleep disturbance, psychiatric, and cognitive functioning in veterans with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Sleep Disord Treat Care 2015; 4(2): 2. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tkachenko N, Singh K, Hasanaj L, Serrano L, Kothare SV: Sleep disorders associated with mild traumatic brain injury using sport concussion assessment tool 3. Pediatr Neurol 2016; 57(46-50): e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jaramillo CA, Eapen BC, McGeary CA, et al. : A cohort study examining headaches among veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan wars: associations with traumatic brain injury, PTSD, and depression. Headache 2016; 56(3): 528-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Juengst S, Skidmore E, Arenth PM, Niyonkuru C, Raina KD: Unique contribution of fatigue to disability in community-dwelling adults with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94(1): 74-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takasaki H, Treleaven J: Construct validity and test-retest reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale in people with chronic neck pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94(7): 1328-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bragatto MM, Bevilaqua-Grossi D, Benatto MT, et al. : Is the presence of neck pain associated with more severe clinical presentation in patients with migraine? A cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia 2019; 39(12): 1500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aoun R, Rawal H, Attarian H, Sahni A: Impact of traumatic brain injury on sleep: an overview. Nat Sci Sleep 2019; 11(11): 131-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim SH, Lee DH, Yoon KB, An JR, Yoon DM: Factors associated with increased risk for clinical insomnia in patients with chronic neck pain. Pain Physician 2015; 18(6): 593-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Juengst S, Skidmore E, Arenth P, Niyonkuru C, Raina K: Unique contribution of fatigue to disability in community-dwelling adults with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94(1): 74-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]