Abstract

Violence against American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women, children, two-spirit individuals,1 men, and elders is a serious public health issue. Violence may result in death (homicide), and exposure to violence has lasting effects on the physical and mental health of individuals, including depression and anxiety, substance abuse, chronic and infectious diseases, and life opportunities, such as educational attainment and employment. All communities are affected by some form of violence, but some are at an increased risk because of intergenerational, structural, and social factors that influence the conditions in communities where people live, learn, work, and play. Using a violence prevention public health approach, we discuss the role public health can play in addressing and preventing the prevalence of missing or murdered indigenous persons (MMIP).2 This paper is written as a public health primer and includes a selective overview of public health and Native public health research. It also includes case studies and Native experts’ reflections and suggestions regarding the use of public health knowledge and theory, as well as Native knowledge and cultural practices to combat violence. An effective public health prevention approach is facilitated by complex, contextual knowledge of communities and people, including individual and community risk factors, as well as protective factors in strengthening Native communities and preventing MMIP.

Author Perspective.

Indigenous Framework and Cultural Identity

Indigenous knowledge during responsive cultural practices using ancestral values shows promise in preventing violence and restoring families and communities to balance with solid mental health. Indigenous practices bring ultimate health, healing, wellness, and growth from historical trauma, past and present. Indigenous knowledge is experiential and often called a pathway or journey to self-actualization; many traditional knowledge keepers teach that the longest journey is from your head to your heart. The incidence of MMIP continues to reflect the reality of indigenous persons’ vulnerability and a public health crisis.

Reclaiming rites of passage from birth to grave bring healing to intergenerational trauma. These rites of passage restore beliefs that women are life givers, women are respected, and women are sacred: conducting ceremonies during birthing; naming; first word; first step; transition from girl to womanhood; weddings; motherhood; first grandchild; and other rites of passage for boys, men, and elders that indicate transferring into a solid cultural identity that brings joy and contentment.

Indigenous knowledge is proactive and fortifies the cultural identity of indigenous persons at all ages and becomes a protective factor. Beginning with native language restoration, immersion schools taught with only the language heard while still in diapers, media in the language with English subtitles, sign language, skits in the language, creation stories acted out in the language, colleges taught with bilingual instruction, and acting and drama schools producing historical truths in the language.

Indigenous knowledge brings the teachings of the four seasons, which we mark with ceremonies: equinox solstice, songs to sun and moon rotation, planting, medicinal plant use to treat and prevent illness, water, cleansing, return from war or combat, forgiveness, grief and funeral, gratitude and honoring, traditional and sustainable food, etc.

Indigenous knowledge helps clarify and map out cultural identity with our many community roles: gender, sisterhood, auntie, uncle, grandfather, grandmother, cousin, and other kinship roles that unify the extended family.*

Public health promotes and protects the health of people and the communities where they live, learn, work, and play. To prevent violence, public health seeks to create safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments for all people. MMIP affects communities, families, and loved ones, and its victims may be women and girls, children, men, two-spirit individuals, and elders.

Violence is defined as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.”3 Violence, including adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), has a lasting impact on health, spanning injury, disease outcomes, risk behaviors, maternal and child health, mental health problems, and death.4

This paper serves as a public health primer to prevent MMIP. MMIP context is provided by weaving public health, research, and applied examples from AIAN experts, best practices in public health, and legal approaches using traditional wisdom and culture. Woven throughout the text, author perspectives are provided as applied examples to contextualize and complement the topics raised based on the individual experiences of several authors.

II. Role of public health in primary prevention of violence

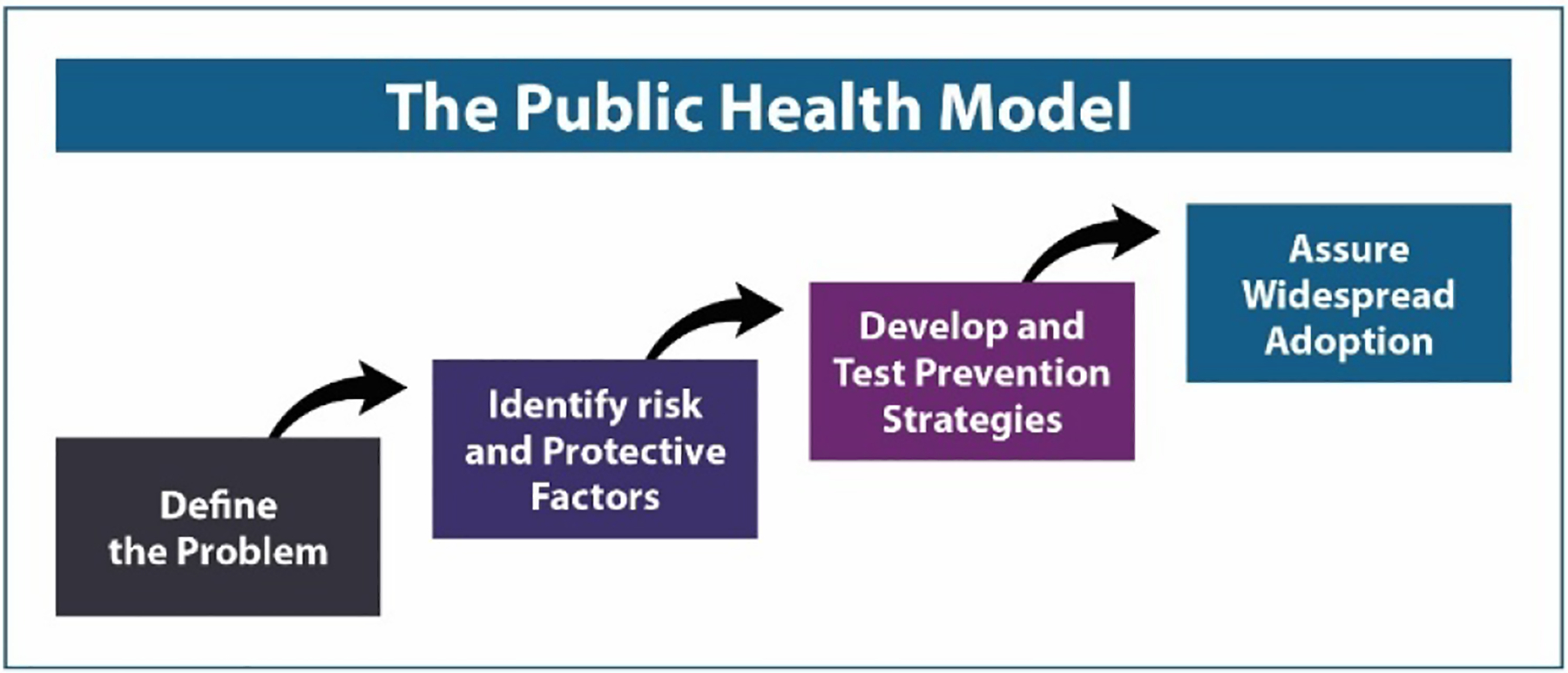

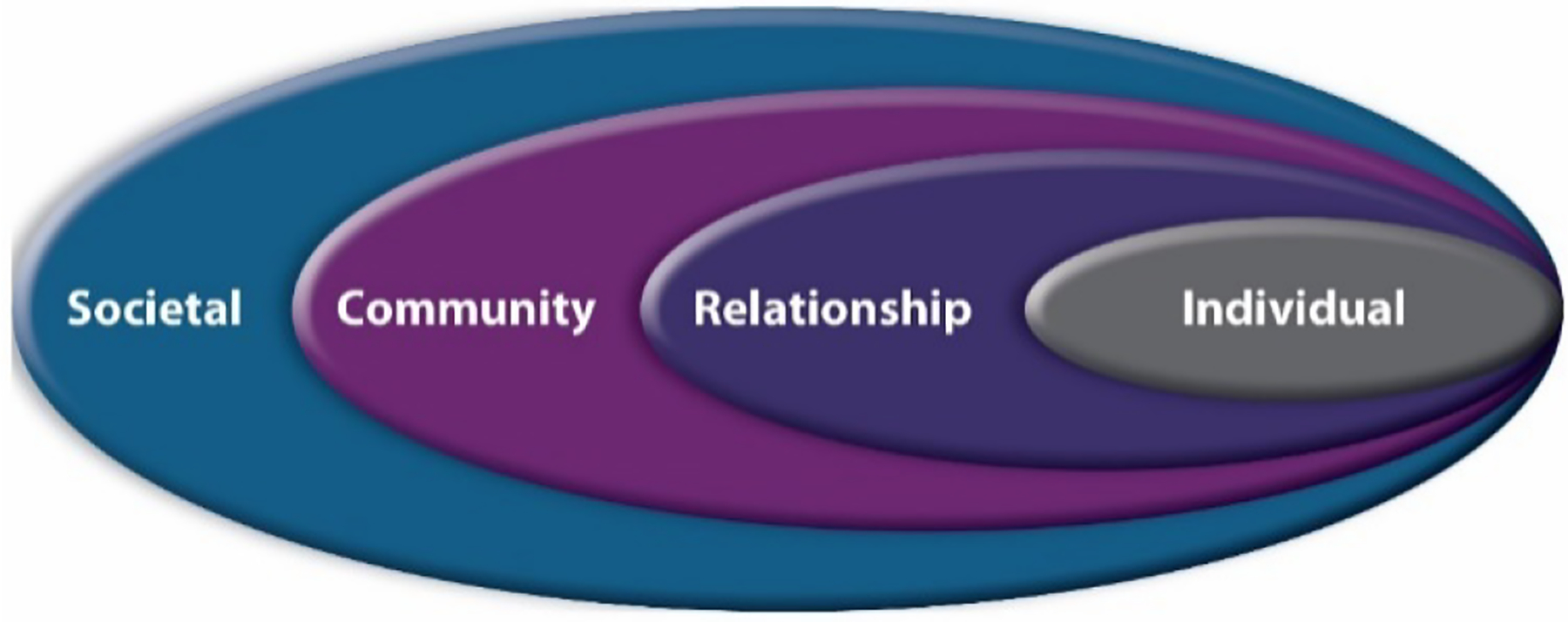

Violence is preventable using a public health approach. Preventing violence from occurring, or primary prevention, may be an effective approach to MMIP. This approach follows a common four-step process (see Figure 1).5 While these four steps may occur sequentially, the process is cyclical, and steps may be revisited at any point. There is also recognition that risk and protective factors (step 2) for one form of violence impact other forms of violence.6 Overall, this public health approach offers a framework for asking and answering questions to build successful violence prevention efforts. Violence prevention efforts are often guided by the Social Ecological Model7 (see Figure 2), which describes how risk factors and opportunities for prevention exist across the social ecology, including at the individual, relationship, community, and broader societal levels.

Figure 1.

A public health approach to violence prevention

Figure 2.

Social Ecological Model of violence prevention

III. Introduction to MMIP data, issues, and complexities

Data are foundational to solving significant public health challenges such as MMIP. This section describes the basic principles of public health data; the most current data available from public health surveillance systems and community-based data advocates; and problems with data, including unique problems experienced only by AIAN, and possible technical solutions to those problems.

There are 574 federally recognized tribes as of August 11, 2020; multiple state-recognized tribes; and urban Indian communities throughout the United States. Contrary to popular belief, about 75% of AIAN live in urban, suburban, and rural settings, not on reservations, in villages, or in Indian country (federal reservation and/or off reservation trust land, Oklahoma tribal statistical area, state reservation, or federal- or state-designated American Indian statistical area).8 AIAN people also live 5.5 years less than the general U.S. population (all races).9 While AIAN people experience broad quality of life issues rooted in structural inequalities, economic adversity, and poor social conditions, AIAN people have persevered and remain resilient.

When we understand the who, what, when, where, and how associated with violence, we can focus on prevention. Data can demonstrate violence frequency, where it occurs, trends, and who the victims and perpetrators are. The data can be obtained from police reports, medical examiner files, vital records, hospital charts, registries, population-based surveys, and other sources.

Step one in a public health model is to define the problem. One primary problem with data for MMIP is that MMIP are underrepresented in statistics, either because they are not counted in the first place (for example, race is not accurately captured in records of missing or murdered persons) or because race is misclassified in data systems (for example, incorrect race data, tabulation issues), which is a common problem in many public health data systems.10

Elected officials and public health decision makers in all jurisdictions need the best data and science for decision making for prioritization and resource allocation.11 While AIAN persons are recognized as a racial minority in the United States, federally recognized tribes are sovereign governmental and political entities.12 This is important for the way we think about supporting public health policy and programming in Indian country and impacts our approaches to data: AIANs need data representation. Describing basic information and dispelling myths about AIAN demographics is important to preventing MMIP.13

The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) datasets from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), and the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) inform MMIP prevention efforts.14 AIAN people experience disproportionate rates of homicide, sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence.15 According to 2018 NVSS data, among those aged 1–44 years, homicide was the third leading cause of death among AIAN males and the sixth leading cause among AIAN females. Interpersonal conflicts are common. For example, NVDRS data from 2015 to 2017 show that homicides among AIAN were most often precipitated by arguments (46%), physical fights between two people (26%), intimate partner violence (18%), and problems with a family member (12%) or a friend or associate (12%). A quarter of AIAN homicides in the NVDRS were related to another serious crime (felony incidents).16 Self-report data collected from adults through the NISVS (2010–2012) indicate that 47.5% of non-Hispanic AIAN women and 40.5% of non-Hispanic AIAN men experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.17 These estimates are likely undercounts of violence AIAN people experience.18

IV. Data issues and complexities

Although data are limited, what we know is that MMIP are a growing and sobering concern for families, tribes, communities, and governments. Collecting and using data is standard public health practice for the United States. Because the AIAN population is small and often clustered in remote areas, it tends to be overlooked in national population surveys and vital statistics. Even when AIAN people are included, the numbers are often too small to provide separate estimates. Therefore, AIAN people can be “statistically invisible,” limiting the ability to identify or address concerns like MMIP.19

The census is the recognized count of AIAN people. The 2010 census found that 5.2 million (1.6%) of the U.S. population reported themselves as being AIAN along with another race, while 2.9 million (0.9%) reported AIAN as their only race. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) reported during that same time that there were nearly 2 million people enrolled in federally recognized tribes, and the Indian Health Service reported their service population was about 2.1 million.20 In 2016, according to the American Community Survey, those who reported AIAN as their only race had the highest poverty rate of any racial or ethnic group (21.7% compared to 10%), were more likely to live in homes with more than one person per room (8.5% to 3.4%), and less likely to have a telephone (6.2% to 3.0%) or motor vehicle (13.4% to 8.7%).21 Lack of electricity and limited access to broadband presents challenges in reporting and preventing MMIP; a 2014 report found that 14% of reservation households did not have electricity,22 and a 2019 report found that 65% had broadband internet coverage.23

MMIP are not confined to reservations. A 2018 report of the Urban Indian Health Institute identified 506 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) in 71 cities from 2010 to 2018.24 Most U.S. MMIP data comes from datasets about violence and crime, which are limited by self-reporting.25 Numbers are often inferred from data sources that measure violence against women and girls, child abuse, exploited girls and women, suicide, and stalking—known risk factors for MMIP. Data consistency would improve how violence is measured and how often data are collected.

Public health data are commonly reported as rates or percentages. Both the numerator (cases reported) and the denominator (population) have to be verified. Even minor changes can affect rates.26 For example, if the numerator for MMIP includes persons who are abducted and voluntarily absent (versus just the number who are abducted), it would inflate the number of MMIP. A denominator that includes the number of AIAN persons nationally produces a vastly different MMIP rate than a MMIP rate based on tribal or local numbers; these different rates could lead to inapt policymaking or public health responses.27 Prevalence over time is also important to consider, as 25 cases in 6 months is different than 25 cases over 10 years. Public health concepts like incidence (the number of new cases) and prevalence (the cumulative number of cases) differ in important ways. Finally, rates are dynamic. Women initially listed as missing may later be found. Numbers and rates need to reflect these changes, along with changes in the local population.

More timely and complete data could help tribes, communities, service providers, law enforcement, and non-profit organizations better address prevention and early intervention approaches for those at risk for and becoming MMIP.28 Because tribes also need data for governance, longitudinal and trend studies are important for guiding action. In this way, we can better describe and target support for MMIP.

Author Perspective.

State-level surveillance and need for Native and other minority data

Federal health surveys provide nationally representative estimates for the U.S. population, but insights on Native populations are limited because of the small number of Native respondents in probability-based sampling frames and non-collection of tribal affiliation. The small sample size leads to data suppression and aggregation of data and racial/ethnic identity tabulation rules that inaccurately capture the Native population—many of whom are multiracial and also identify as Latinx/Hispanic State-level surveillance could raise probability-based representation. California, Arizona, and Oklahoma are states with the largest concentrations of American Indian populations, and Alaska has more than 20% of residents who report at least being partially Native.29 For California, the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), a continuous survey since 2001, can generate data regarding social risk factors at the individual, family, and community levels for Native populations by a multitude of racial/ethnic, non-binary gender, and tribal identities. Using CHIS, women who identify as AIAN report the highest rate (37%) of ever experiencing physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner since age 18.30 State-level surveillance could be a necessary indigenous knowledge investment to more precisely reflect the primary prevention of MMIP.*

Author Perspective.

Tribe-specific public health data are a valid and urgent request. To address critical data gaps, the Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center is dedicating significant resources to provide meaningful data for AIAN tribes, both large and small, through a variety of novel approaches, including oversampling, data linkages, tribally driven surveillance and primary data collection, statistical modeling, geocoding, etc.**

Author Perspective.

Why we need and how we use data

Even with limited, oftentimes unreliable, data, the alarming number of reported MMIW is indicative of the devastating impact of a complex legal framework31 and a failure of systems designed to protect and respond to the intersectionality that Native victims and survivors of violence face. In 2018, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights released the Broken Promises Report, affirming the need for the federal government to fulfill its trust responsibility with appropriate allocations of resources to tribal nations.32

Indian country faces multiple challenges, including but not limited to: (cross)jurisdictional issues (for example, responsibilities, barriers, communication, and planning); (in)action from governmental officials; and limited resources,33 leading to increased risk for violence and MMIP. U.S. Representative Tom Cole (Oklahoma) said it best when he stated, “Hunters know where to hunt, fishermen know where to fish and predators know where to prey. And sadly, a disproportionate number of sexual predators have preyed on Indian Country and Native women.”34 While tribal leaders push for restoration of inherent tribal authority, advocates call for more complete and accurate data to fully understand the MMIW crisis.

Without accurate data, it is difficult to educate Congress about MMIP. With accurate data and implementation of the data directives in Executive Order 13898,35 Congress may better understand the scope of the issue and make informed decisions on what is needed for MMIW prevention.*

V. Shared risk and protective factors

The different forms of violence (for example, intimate partner violence and sexual violence) share similar risk and protective factors that accumulate throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.36 Recall step two of the public health model: MMIP is interconnected to multiple forms of violence, and knowledge is needed to understand how historic and contemporary risk and protective factors affecting AIAN people may contribute to violence prevention efforts.37

Author Perspective.

The situation and condition with respect to MMIW is much greater than we currently know. Across the United States, we live in a society that devalues women. There are a host of historical factors and systemic factors that make this condition much worse in tribal communities for Native women and children.38*

Social determinants of health (SDOH) or the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age affect violence experiences.39 Data show how AIAN people may be at increased risk for violence due to high adverse childhood experience (ACE) scores and applicable SDOH. For example, education attainment, a protective factor, is lower for AIAN; only 72% of AIAN students graduate from high school with a regular four-year diploma—this statistic increases to 82% if GED recipients are included. Only one in five (20%) high school graduates age 18–24 enroll in college.40

Violence risk factors may include reminders of historical trauma experienced by AIAN populations (for example, loss of land, language, traditions, and respect for traditional ways) that contribute to inequities.41 Despite inequities, AIAN communities remain resilient and possess cultural and community assets that can protect against violence, including community-mindedness, connection to tribal leaders, tribal language, participation in tribal ceremonies, and spirituality.42 Effectively identifying and supporting culturally relevant risk and protective factors across varying forms of violence may enhance the public health approach, help develop AIAN programs, and help adapt existing programs for violence prevention.43 The CDC’s violence prevention technical packages are available to help communities make decisions based on the best available evidence.44

VI. Violence risk factors affecting AIAN people

AIAN experience disproportionate risk factors for MMIP, which can be traced to the legacy of violence against Native people rooted in the appropriation of lands, including the forced marches from traditional homelands; the capture, trafficking, and enslavement of men, women, and children;45 and the current struggles of cases being lost within judicial systems.46 The history of the U.S. government’s policies and colonialism’s historical context provide a deeper understanding of the forces at play and the limited resources that tribal communities have for protecting their citizens from violence, rendering these communities more vulnerable to MMIP.

The U.S. government’s ethnocidal policies (for example, federal assimilation, termination, and relocation) and past genocidal policies (for example, military actions, forced relocation) for AIAN people47 led to historical and intergenerational trauma.48 The separation and destruction of families and communities by forcing generations of children (against parents’ will or willingly) to attend Indian boarding schools modeled on authoritarian, military culture was intended to erase indigenous identity.49 Many children at these boarding schools experienced physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and neglect.50 These experiences resulted in the dismantling of Native communities and families and the loss of culture, language, pride, and any sense of safety or belonging. Boarding school and non-AIAN foster family experiences are fundamental contributing factors to historical trauma,51 and their effects (for example, abuse, loss of traditional gender roles, and parenting styles) are not only passed down from generation to generation through stories, but also through epigenetics and role modeling behavior where AIAN people experience higher ACE scores, which leads to increased risk for violence and subsequent adverse health outcomes.52 These experiences lead to intergenerational trauma affecting future generations’ interpersonal relationships, including child abuse and neglect, elder abuse, and violence against women.53

In addition to the historical context placing AIAN people at greater risk for experiencing MMIP, social contexts are operating and influencing risk.

There is an enduring violence generally against women and Native women in society. [MMIP] has been going on for decades or centuries and is not a great secret if you are looking. Other background contexts include, but are not limited to, white privilege, sexual conquest of (Native) women, racism and racial ambiguity, gender bias and stereotyping, and misogyny.54

The connection between historical trauma, intergenerational trauma, and MMIP is a tangled mix of issues that cross the social ecological model. Trauma influences individual behaviors such as substance misuse and mental health-related issues.55 Sexual violence is common, starts early, and is costly.56

One explanation for missing status may be related to the exploitation and victimization of AIAN persons in the sex trafficking industry, which occurs in urban and rural areas and is well established in literature as occurring near border towns and pipeline construction.57 Risks may occur across local, tribal, regional, national, and transnational levels. SDOH, including underhousing and overcrowded housing where AIAN people experience extreme poverty and unsheltered homelessness provide many community-level risk factors.58

At the societal level, structural and institutionalized policies affecting SDOH have led to complicated jurisdictional issues; issues with the foster care system; lack of emergency services; conflict between tribes and local, state, and federal governments; and a lack of communication between agencies like the local police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and tribal police.59 These complex social systems may be more effective when working collectively and in collaboration to prevent MMIP.

AIAN people are at risk to be missing or murdered because they experience the same factors that put any individual at risk for violence, which is compounded by additional risk due to historical trauma, intergenerational trauma and violence experiences, and structural issues rooted in the systemic violence against and devaluation of AIAN.60

VII. Protective factors affecting AIAN people

AIAN tribes are diverse and unique in their ceremonies and practices. AIAN people share a common belief that their traditional wisdom is protective, and they seek to alert public health and social justice officials to the immediate need for programs grounded in traditional knowledge, practice, and ceremony to address the issue of MMIP. This primer aligns with the call to action set forth in the American Indian and Alaska Native Cultural Wisdom Declaration: to honor culturally relevant public health interventions and the inherent self-determination and resilience of Native people.61

Engaging in “strength-based conversations” and connecting to our wisdom teachings enables us to respond to this pressing issue.62 Native American cultural knowledge, spiritual and ancient healing, and health systems have endured the test of time and exist to address the entangled and complex trauma of violence. Wellness, protection, self-determination, and resilience emerge from AIAN teachings.

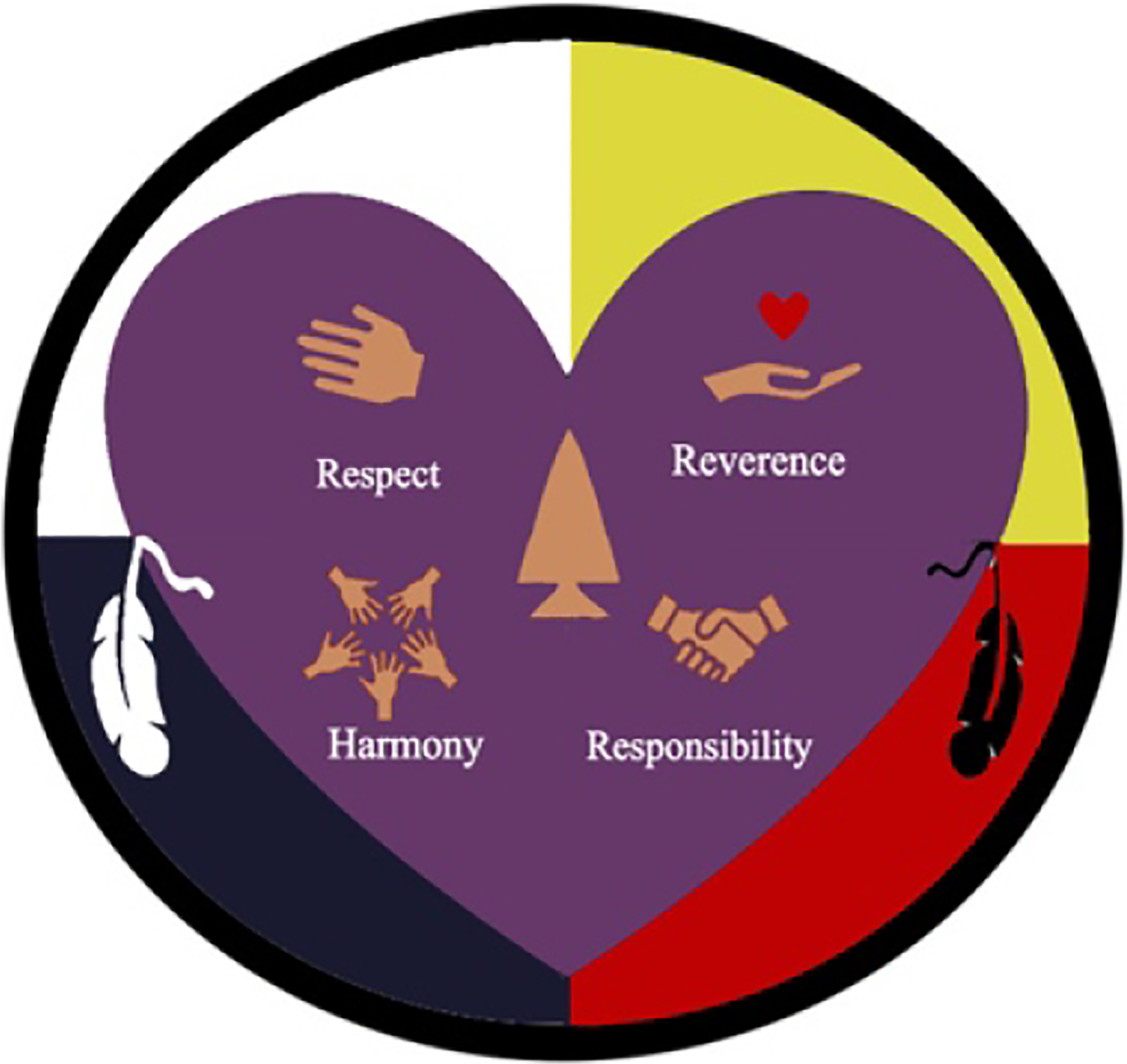

Traditional wisdom is holistic, and the values and practices are relevant across social ecological model levels. The violence prevention solutions are layered and found by aligning the justice and public health systems to AIAN sacred knowledge. Public health approaches have been shown to be more effective when grounded in a relationship that honors trust and includes culturally relevant health and healing interventions, along with social and legal service initiatives that incorporate the traditional values of respect, responsibility, relevance, and harmony (see Figure 3).63

Figure 3.

Four AIAN Traditional Values (artwork courtesy of Miguel Flores, Jr., and Michelle Kahn-John) The circle represents the Medicine Wheel and the four directions. The purple heart represents healing, with the four core values of cultural wisdom in the center. Black and white feathers represent dichotomous thinking and dialectics, as sometimes legal and behavioral health do not see eye to eye.

Author Perspective.

What would violence prevention based on AIAN Traditional Values look like

Respect:

Through our ancient ceremonies and our daily activities, we hand down stories to each generation that teach us to respect ourselves, one another, and our community. The framework for tribal sovereignty and self-determination is built on trust and demonstrated in criminal justice systems by respecting tribal laws and traditional practices.

Reverence:

All of creation is a sacred gift. Life itself is held in great reverence, including elders, women, men, children, and the places from which we emerged, water, land, and air. Interventional approaches would be considerate, kind, and compassionate, and we must be conscious and intentional to avoid re-traumatization as well as offer support.

Responsibility:

All of creation is a sacred gift, and our responsibility is to care for it. This includes creating safe environments, homes, schools, workplaces, and tribal lands. Timely investigations and treating victims, offenders, and their families with respect is an important element of the responsibility to care.

Harmony:

Indigenous solutions return victims and families back to balance. A victim’s non-response is a symptom of trauma. The external forces and the cascading of events is exhaustive and can disable the capacity to respond. Our ceremonies are designed to recover balance that allows for transformation from the effects of trauma.

AIAN have profound knowledge to protect AIAN people, and AIAN know this wisdom is true. The principles of respect, reverence, responsibility, and harmony would be honored, and the sacred needs to align with various intersecting systems. AIAN have survived thousands of years because of this knowledge system. That is why AIAN are still here, why they persevere, and why they endure.*

VIII. Violence Prevention and Public Health Law

To address and prevent violence in AIAN populations,64 we turn to the tools of public health law and policy. Public health law is defined generally as the powers and duties of federal and state governments to advance public health aims across populations, including prevention as previously defined in this article, while protecting individual rights.65 As written in the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, states have “police powers” over health, safety, and welfare to effectuate public health laws on everything from infection control, motor vehicle safety, and prescription drug overdose to violence prevention.66 States also have the authority to delegate these powers to localities.67

Together, these laws can prevent individuals and populations from experiencing violent outcomes, such as going missing or being murdered, but as noted in greater detail in this section, there are gaps.68 These gaps are exacerbated in AIAN communities due to a lack of data that could help identify MMIP, clarify the public health dimension of MMIP, and tailor effective ways to prevent violence.69 As discussed later in this section, our rapid assessment of current federal and state public health laws and policies identified few statutes and regulations that specifically address AIAN people or the specific needs of AIAN communities.

Some people may perceive tribal law as bearing primary responsibility for addressing the interests of AIAN people. Outside of Alaska, where many rural communities are majority AIAN, about three in four AIAN people live outside of reservations, where they are neither subject to tribal law nor likely perceived as key constituents of state and local policymakers who may operate on the presumption that AIAN interests and needs are addressed by tribal authorities.70

Public health law can be used to help prevent the disproportionate impact of violence on AIAN populations, particularly as policymakers consider a coordinated legal approach comprised of federal, tribal, state, and local measures and initiatives to prevent violence in AIAN populations.71

A. Federal law and violence prevention

Federally recognized tribes in the United States, as sovereign nations, operate tribal governments that exercise jurisdiction over their lands and citizens and conduct formal nation-to-nation relationships with the U.S. government. The inherent power of tribes to self-govern is recognized in the U.S. Constitution, as well as in various treaties and case law.72 These legal sources describe a “trust responsibility,” or duty of protection, owed by the U.S. government to tribal nations and their members.73 One critical manifestation of that trust relationship can be federal funding,74 which may have a significant impact on violence prevention activities. Two of several laws allocating such funding are discussed below.

The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) create funding initiatives aimed at preventing violence against women, including “Native women,” as defined in these laws. VAWA was passed by Congress in 1994 and requires the Attorney General to conduct annual consultations with tribal governments about administering its funding and programs.75 VAWA also includes initiatives that strengthen law enforcement services for preventing violence against women, expand recognition of tribal jurisdiction over non-Native perpetrators, and allocate funds to expedite the processing of rape kits and other victim services.76 Additionally, VAWA authorizes the Department of Justice’s Office on Violence Against Women to administer grants through several programs designed to reduce domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking.77 Typically, programs funded under VAWA or other federal grants have a competitive application processes and stringent reporting requirements that can make them inaccessible to some tribes with few resources, limiting their reach and impact in AIAN communities.78

FVPSA is the primary source of federal funding for emergency support and services for victims of domestic violence and their dependents, with funds directed to states, territories, tribes, state domestic violence coalitions, and resource centers.79 FVPSA also supports efforts to prevent repeated victimization through prevention and public awareness initiatives.80 Much of the federal funds intended for tribal services have typically been directed through states first, only some of which ultimately reach tribal communities.81 As of June 2018, however, approximately 10% of FVPSA funds were distributed through tribal formula grants that were earmarked specifically for tribal services.82

Federal grants like these and others to tribal organizations can be used to evaluate and analyze data related to the high prevalence of MMIP, including whether law and policy are effective in preventing violence. Tribal leaders, however, reported during the annual consultation with the Attorney General that current direct funding to tribes is insufficient to implement violence prevention initiatives, including legal and policy analysis activities, within federally recognized tribes.83 This perceived insufficiency is likely compounded when considering non-federally recognized tribes and AIAN women who live outside of tribal lands. Awarding grants to state governments for sub-allocation to tribes or to cover tribes within their boundaries, either due to congressional statute or directives or agency strategy, can make it difficult for tribes to administer service programs for their own citizens if states make funding and programmatic decisions without sufficient input from, and understanding of, needs within tribal communities.84 Competitive grant funding processes may make it more difficult for some tribes to apply and ultimately be awarded funds, thereby potentially perpetuating inequitable access to resources that tribes, instead of states, are best equipped to deploy to address their communities’ needs.85 While this is a burgeoning area of focus, federal and state initiatives point to a recognition that laws and policies can be used to ensure tribes receive adequate funding for violence prevention programs that strengthen AIAN data collection efforts and create culturally relevant and sensitive programming to combat violence against AIAN people and protect AIAN communities.86

B. State violence prevention laws

Some states and localities have also sought to develop public health laws to prevent the downstream effects of violence. With few exceptions, however, these laws are limited in number and scope, do not expressly define primary or secondary prevention, and largely do not specifically address AIAN needs.

Results from a rapid legal assessment indicated that 12 states in the United States have statutes or regulations reflecting legislative or regulatory attention to primary or secondary violence prevention.87 For example, Minnesota authorizes its commissioner of public safety to “award grants to programs that provide sexual assault primary prevention services to prevent initial perpetration or victimization of sexual assault.”88 New York also established a grant to support primary and secondary prevention programs aimed at domestic and family violence and child abuse; it requires annual reporting to the governor and legislature on the effectiveness of their prevention and treatment initiatives.89

None of these laws specifically identify AIAN women as key targets, but some laws have discrete implications for AIAN populations. For example, Washington addresses primary and secondary prevention of domestic violence by prioritizing the development of “culturally relevant and appropriate services” for victims and their children from unserved or underserved populations.90 Because it also establishes a domestic violence prevention account in the state treasury to support such culturally appropriate, community-based services91 and emphasizes secondary prevention of domestic violence in other parts of the public health code related to alcohol and drug treatment,92 the impact of these provisions could be far-reaching for AIAN individuals living in Washington.93

Apart from primary and secondary prevention, a second rapid assessment identified 10 laws in 7 states that address “missing and murdered” AIAN people, all of which focus on law enforcement responses.94 Only one provision, from Utah, mentions prevention.95 Some states, like Oklahoma, established a government entity, such as a task force or commission, to study and implement programmatic initiatives. Oklahoma is exceptional in its inclusion of AIAN women in its Domestic Violence Fatality Board, which draws upon the input of several institutions, including the health department, to examine domestic violence incidents and fatalities, as well as the views of at least one AIAN survivor of domestic violence.96

C. Opportunities for improvements in public health law and policy

As our rapid assessments indicate, the relatively small number of states with laws specifically addressing AIAN individuals suggests a silence in public health law about the phenomenon of missing or murdered AIAN women. Laws establish authorities and priorities for jurisdictions to create and implement policies and programs and are a critical foundation for improving our response to the MMIP crisis. Accordingly, lawyers, judges, advocates, and policymakers can form strategic alliances with public health practitioners at each level of government to address MMIP. Training and capacity building can help build the literacy of the public health workforce in public health law.97 Also vitally important in these efforts is educating lawyers on how to promote primary and secondary violence prevention.

Laws can be valuable tools to fill critical gaps in data collection about missing or murdered people. Laws can, themselves, be a source of instructive data. Using legal epidemiology and policy evaluation, public health practitioners can assess legal strategies for preventing violence.98 Subsequently, data from these studies can be used to develop and more equitably apply policies, such as investigations, to missing or murdered AIAN people. Public health law initiatives, such as medical–legal partnerships or alternative funding mechanisms, can also help support AIAN communities and expand research in violence prevention.99

Legal epidemiological research and policy surveillance can lead to sustained, evidence-informed activities and decision making for improving the difficult social and environmental conditions in which some AIAN people live. It can also inform an often overlooked but crucial area for growth in the legal realm, expanding the awareness of judges and lawmakers of critical gaps in the law and promoting trauma-informed approaches in addressing matters involving MMIP.

Author Perspective.

State of emergency declared—why we wear red

Indigenous women and children suffer a spectrum of violence, including rape, physical assaults, abductions, and murder. Violence began with first contact and continues to escalate with no accountability as reflected in the current MMIW crisis.

As of August 2020, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) system listed 619 missing Alaska Native and American Indian people, 241 of those were from Alaska—the most of any state.100 Many agree there are many more unreported or misclassified deaths that should be included in this number. Over half of Alaska Native women experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime.101 Alaska is reported to have the highest homicide of women by men,102 and Alaska has the highest state violent crime rate (2018).103

Tracking MMIW is difficult because the deaths are often classified as accidents, suicides, or undetermined—even with signs of foul play—meaning investigations do not take place. Reports often go uninvestigated because there is no evidence of a crime or dismissed due to perceived or actual alcohol/drug use. This leaves families and friends to conduct the searches themselves.

Tribal governments have the inherent right and ability to protect their citizens but for the federal and state barriers.

Our tribal governments likely would be in a better position to respond and provide public health prevention, public safety, social services for victims, and justice systems with fewer barriers. Increasing the collaboration and coordination of federal, state, and tribal investigations, prosecutions, and law enforcement would likely lead to improved protocols for intervention and the establishment of an alert system similar to the amber or silver alerts for children and elders.

Mothers, aunties, and grandmas have been put in the position to not prevent violence, but to prepare our daughters how best to survive when they inevitably experience physical or sexual violence.

We wear red for the missing women and for an end to the violence.*

Author Perspective.

The role of prevention in healing intergenerational and historical trauma

Intergenerational and historical trauma represents an imbalance and disharmony that has been the result of years of trauma passed from generation to generation. The repetitive and cumulative effects of this trauma and unresolved grief originated from the loss of lives, land, spirituality, language, and other aspects of AIAN culture as a result of colonization.

Prevention is integral to healing from intergenerational and historical trauma, including understanding the risk and protective factors. The protective factors are key to prevention efforts. Restoring harmony and balance involves developing a sense of who we are in relation to our history, nature, land, time, and our physical and spiritual world. Elders are the carriers of culture and tradition. The wisdom and knowledge of our elders are essential parts of the healing process.

Our history is woven into the very fabric of our daily lives. Our history is the premise of who we are and how we make decisions today. What our ancestors have gone through and what we have gone through is as real as yesterday. It is a history not of mere survival but of resiliency and strength. Our ancestors, elders, and activists before us left us a legacy, and we have the responsibility to pass this legacy on to future generations. Future generations listen and learn and take on this responsibility to restore the harmony and balance to tribal communities.

Tribal people have fought to maintain traditional ways, beliefs, and value systems. Native languages are spoken. Tribal sovereignty remains strong. The interconnected view of the world has survived. The sense of duty and responsibility to others continues, as well as an unwavering ability to not only survive but to succeed and thrive despite all obstacles, and an unwillingness to give up. Current and past activists led the efforts to address MMIP with dignity, strength, and hope that will benefit future generations.*

IX. Conclusion

AIAN people are at increased risk to be missing or murdered because they experience all of the same factors that put any individual at risk for violence, compounded by centuries of structural inequities rooted in systemic violence against AIAN people. AIAN communities survive and, through action, are moving toward collective healing, promotion of health and well-being, and ultimately, to the prevention of MMIP. Violence is preventable. We recommend deploying the public health model—collecting and using data to guide policy and program approaches grounded in traditional Native wisdom.

X. Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and honor victims, families, and communities affected by MMIP today and our ancestors that survived so that we and our allies are able to collaborate on public health today; decades of work by supporters and advocates; and victim service organizations and criminal justice systems. We acknowledge colleagues across the U.S. federal government and the Presidential Task Force on Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives (Operation Lady Justice; see https://operationladyjustice.usdoj.gov/). The authors would like to give special thanks to Dr. Luis Pena for his support of tribal and urban Indian communities for over 30 years, his expertise in education and social ecological theory, and for editing drafts of the paper. We thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Law Program interns, Susannah Gleason, Brianne Schell, Brian Smith, and Rebecca Rieckhoff, for assistance with citation. We especially thank the countless knowledge keepers from Indian country who provided support and expertise. In addition, the authors would like to thank these organizations for their support and/or work to prevent MMIP:

The Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center;

The American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian Coalition of the American Public Health Association;

The American Indian Research Center for Health, Community Advisory Committee at the University of Arizona;

The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women;

Healing Our Nations, Offering Resiliency (HONOR);

The Indigenous Alliance Without Borders;

The National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center;

The Native Research Network, Inc.;

The Sage (Indigenous Critical Thinking) Circle for Healing of Our Indigenous Communities;

The Sovereign Bodies Institute; and

The Urban Indian Health Institute.

About the Authors

Chester Lewis Antone is an enrolled member of the Tohono O’odham Nation. He earned an associate degree in General Studies from Pima Community College in Tucson and a Bachelor of Science in Public Administration from the University of Arizona. Mr. Antone has served for 12 years as a Council Member from the Pisinemo district of the Tohono O’odham as Chairman of the Health Committee. He Chaired the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s Tribal Advisory Committee from 2008 to 2019 and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Tribal Advisory Committee from 2015 to 2019. Mr. Antone led the development of the Cultural Wisdom Declaration adopted by multiple tribes and the National Congress of American Indians published in the National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda.

Teshia G. Arambula Solomon, PhD, is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation and an Associate Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine and University Distinguished Outreach Faculty at the University of Arizona. Dr. Solomon has a distinguished career in community-engaged research with Native American communities and training Native scholars in research. She is a Principal Investigator for the American Indian Research Center for Health in partnership with the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona. She is the Lead Editor and author of the book Conducting Health Research with Native American Communities (2014) and co-author of the Cultural Wisdom Declaration (2016). Dr. Solomon received her Bachelor of Science in Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance from Central State University, her Master of Science in Health, Physical Education, and Leisure Sciences from Oklahoma State University and her doctorate in Kinesiology and Health Education from the University of Texas at Austin.

Elizabeth Carr currently serves as the Senior Native Affairs Advisor at the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center (NIWRC). Before her role with NIWRC, she served as the Associate Director for Tribal Affairs in the Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. She focuses her work on managing and improving federal–tribal relations and is dedicated to the analysis, development, and implementation of federal policy related to tribal governments. Ms. Carr is a member of the Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and holds a Bachelor of Science from Grand Valley State University and a Master of Science from the University of Michigan.

Michele Connolly, an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Nation in Montana, has a Master of Public Health in biostatistics from the University of California, Berkeley. She serves as Co-Chair of the International Group for Indigenous Health Measurement (IGIHM), a four-country group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, under the auspices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Throughout her 32-year-long federal career, she has focused on Indigenous people, health, poverty, aging and disability programs, and policy. Most of her time was spent as a mathematical statistician in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Secretary of Health and Human Services. She worked on Indigenous measures in the censuses and led an interagency effort to develop, implement, and analyze the first national disability survey in the United States. She has also worked at other agencies, including several assignments in the White House, where she did projects on health care reform, welfare reform, HIV/AIDS, and other topics. Most recently, she was a Visiting Professor at the University of Sydney, the editor of a special edition (Measuring Indigenous Identification) in the Journal of the International Association of Official Statistics (JIAOS), wrote articles for that special edition, co-authored an article in Lancet on health and social disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in 23 countries, serves as Indigenous Editor for JIAOS, and performs various projects for the United Nations. During the school year, she works as a Home Hospital Teacher teaching advanced high school math and science to students too ill to attend school.

Felina Cordova-Marks, member of the Hopi Tribe, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Arizona Cancer Center and the Director of Tribal Engagement for the University of Arizona’s COVID-19 Cohort (COVHORT), a College of Public Health Research Study. Her research interests include American Indian women’s health issues such as MMIP, reproductive freedom, cancer (biologic and behavior related), stress and resilience, and caregiving (those providing care to a family member with cancer, chronic disease, are disabled, or are elderly). She received her doctorate in Public Health and Master of Public Health from the University of Arizona College of Public Health.

Kevin English is the director of the Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center (AASTEC). Kevin has worked with tribal communities across the country since 1995 as a researcher, public health practitioner, and a clinical pharmacist. He received a Bachelor of Science in Pharmacy from the University of Iowa in 1995 and a Doctorate in Public Health from Columbia University in 2013. Before becoming the AASTEC Director in 2011, Kevin led the development and implementation of several tribal cancer control and public health capacity development initiatives in collaboration with the seven consortium tribes of the Albuquerque Area Indian Health Board. The overarching theme of all Kevin’s work is to address and ameliorate health disparities experienced among American Indians in the Southwest and throughout the country.

Miguel Flores Jr. is a true patient and community advocate. He works with Native American communities and is a traditional healer and counselor. Mr. Flores is a Licensed Independent Substance Abuse Counselor in the State of Arizona, a Certified Sex Offender Treatment Specialist, National Board of Forensic Counselors. He is a proud member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and Tohono O’odham Nation, a husband, a father, an artist, a healer, a counselor, and a teacher. He is a community leader and chairman of the Community Action Committee for American Indian Research Center for Health and the Arizona Partnership for Native American Cancer Prevention project at the University of Arizona. He serves as a member of the Tribal Advisory Committee for the Tucson Area for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Indian Health Service. He is also a member of National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program, Participant Engagement Board, Research Access Board, Bio Specimen Policy Task Force, Native American Community Board, and an Ambassador for the program.

Patrisia Gonzales is an Associate Professor at the University of Arizona, where she teaches courses on Indigenous medicine and is a co-investigator with the American Indian Research Center for Health Career Development Program. She descends from three generations of traditional healers and has provided traditional care for pregnant women, the chronically ill, and survivors of trauma and torture. She authored Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous Rites of Birthing and Healing (2012) and Traditional Indian Medicine: American Indian Wellness (2017).

Bette Jacobs is a Professor of Health Systems Administration and co-founder and Distinguished Scholar at the Georgetown University O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law. Dr. Jacobs has worked to improve the human condition by creating innovation in a variety of sectors and fields. A member of the Cherokee Nation, she was the 17th American Indian to become a tenured professor. The author of more than 75 publications, her work has a wide range of sponsors. As a former executive for a multinational engineering company, she brought leadership skills to higher education in administrative and advisory roles. She was a Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford 2010–2011 and an invited participant for the 2016 leadership program at the U.S. War College. Presently, Dr Jacobs is a principal for the Health Law Initiative including Global Faith Based Health Systems, Justice in America for Native Americans, MMIW, and Health Services. Dr. Jacobs teaches courses on non-profit governance indigenous people and human rights, and the Ignatius Seminar, Serving the Common Good. She serves on various boards and is a member of the International Group on Indigenous Health Measurement.

Michelle Kahn-John, PhD, is a member of the Diné Nation and is currently a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Arizona. Michelle’s research is on understanding the health benefits of Hózhó, a sacred Diné (Navajo) wellness philosophy in her multifaceted roles as a nurse, a healthcare provider, an American Indian spiritual wisdom keeper, a teacher, a scholar, a scientist, a mentor, a consultant, a leader, and a Diné woman. She received her doctorate in Nursing from the University of Colorado.

Laura M. Mercer Kollar, PhD, is a behavioral scientist with the Division of Violence Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laura’s research interests include sexual violence prevention, community-level violence prevention partnerships, violence prevention in American Indian and Alaska Native communities, health communication, and behavioral interventions. She received her Bachelor of Arts in Social Relations and Master of Arts in Health and Risk Communication from Michigan State University and received her doctorate in Communication Studies from the University of Georgia.

Amanda Moreland is a Public Health Analyst and DRT Strategies contractor for the Public Health Law Program (PHLP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In her role at PHLP, Amanda provides technical assistance to state, tribal, local, and territorial partners and conducts legal epidemiology research and analysis on a variety of topics, including infectious disease control, environmental health, emergency preparedness, and administrative law. Amanda earned her Juris Doctor and certificate in international and comparative law from DePaul University College of Law and earned both her Master of Public Health and Bachelor of Health Sciences from the University of Missouri.

Theda New Breast (Makoyohsokoyi—Blackfoot name) was born and raised on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana, with a relocation experience in the San Francisco Bay area during the civil rights movement, entering UC Berkeley at 17 years old and receiving her Bachelor of Social Work and Master of Public Health in Health Promotion and Prevention. Theda is a founding board member and master trainer/facilitator for the Native Wellness Institute (NWI) 1988–present. She is also a board member of the Sovereign Bodies Institute (SBI), launched in 2019, which builds on Indigenous traditions of data gathering and knowledge transfer to create, disseminate, and put into healing on gender, sexual violence against Indigenous people and MMIWG (Missing Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls). Theda has been a leading authority on Indigenous Cultural Resilience Internationally in Canada, the Lower 48, Alaska, Australia, and New Zealand on proactive healing from historical trauma, post traumatic growth, mental health healing and sobriety/recovery/adult children of alcoholics. She is a co-founder and co-writer of the GONA (Gathering of Native Americans) curriculum, one of the ten effective practices and models in communities of color. Theda is a Khan-nat-tso-miitah (Crazy Dog) Society member and Kaamipoisaamiiksi (owner of a Standup Headdress) Blackfoot Women’s Society. She sundanced with the late Buster Yellow Kidney’s bundle for 10 years. In 2013, The Red Nations Film Festival honored Theda with a humanitarian award for her lifetime of healing work with tribes and with a Red Nations statuette for her documentary short called Why The Women in My Family Don’t Drink Whiskey (free on YouTube). The Blackfeet Tribal Council has recognized her Leadership skills and appointed her unanimously to the Board of Trustees for the Blackfeet Community College for years 2014–2017. She is currently certifying Healthy Relationship Trainers for NWI, which is a curriculum identified as “Best Practice” from ANA (Administration for Native Americans).

Debra O’Gara is the Senior Policy Specialist for the Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center and Pro Tem Judge for the Tlingit and Haida Tribal Court. Debra earned her Juris Doctor from the University of Oregon in 1990 and a Master of Public Administration from the University of Alaska Southeast in 2013. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, researching the traditional Tlingit dispute resolution practices before colonialism. Debra has been a prosecutor, staff attorney, policy director, advocate, and a mediator with a focus on children, families, domestic and sexual violence, and both women and Native rights. Since 2007, she has been a Tribal Court Judge and active in helping develop tribal courts throughout Alaska. Debra is a citizen of the Central Council Tlingit and Haida Tribes of Alaska and is from the Cedar Bark House of the Teeyhittaan Clan of Wrangell, and her Tlingit name is Djik Sook.

Ninez A. Ponce, MPP, PhD, is a professor in the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and the director of its Center for Health Policy Research. She leads the California Health Interview Survey, the nation’s largest state health survey, which is recognized as a model for data collection on American Indian/Alaska Native identities and in oversampling American Indians in urban and rural settings. Dr. Ponce led a study for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation on improving the data capacity of federal population health datasets on American Indians and Alaska Natives. In 2019, Dr. Ponce and her team received the Academy Health Impact award for their contributions to population health measurement to inform public policies. She received her Bachelor of Science in Nutrition and Food Sciences from University of California Berkeley, her Master in Public Policy in International Development from Harvard University, and her doctorate in Health Services from University of California Los Angeles.

Tara Ramanathan Holiday serves as the team lead for research and translation and a public health analyst with the CDC’s Public Health Law Program, where she specializes in state and local government law related to health system transformation, health information technology, and healthcare quality. Ms. Holiday has published over 40 reports and articles and delivered presentations to over 400 people annually on the use of law to address emerging public health issues. She developed many of the core methods and guides for the field of legal epidemiology and co-authored a graduate-level textbook, The New Public Health Law: A Transdisciplinary Approach to Practice and Advocacy (2018), with preeminent lawyers in the field. Ms. Holiday is a licensed member of the State Bar of California. She received her Juris Doctor from Emory University School of Law, her Master of Public Health from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and her Bachelor of Arts from Wellesley College. She began her career in public service as a Peace Corps volunteer supporting rural health programs and community development in Senegal, West Africa.

Delight E. Satter, MPH, is a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Senior Health Scientist for the Office of Tribal Affairs and Strategic Alliances in CDC’s Center for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support. Satter’s primary job functions include providing counsel on issues related to complex tribal research, science, and program integration assignments that reflect the priorities, policies, interests, and initiatives of the agency. Satter’s public service activities include serving as a faculty associate and past director of the American Indian Research Program, UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; a board member-at-large for Native Research Network, Inc; and a member of the Community Advisory Committee, University of Arizona, Native American Research and Training Center. She received her Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology from the University of Washington and her Master in Public Health from the University of Minnesota.

Sharon G. Smith, PhD, is a behavioral scientist in the Division of Violence Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sharon’s research interests include surveillance and survey research, sexual violence, stalking, intimate partner violence, and violence prevention in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Dr. Smith received her Bachelor of Arts in Psychology and Master of Arts and doctorate in Community Psychology from Georgia State University

Antony Stately (Ojibwe/Oneida) received his PhD in clinical psychology from the California School of Professional Psychology at Alliant International University in 1997. Currently, he is the Chief Executive Officer for the Native American Community Clinic in south Minneapolis, which provides primary care, dental care, and behavioral health services to the Twin Cities Native American community. He formerly worked as the Director of Behavioral Health Programs at the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community in Prior Lake, Minnesota. Previously, he was a research scientist and Director for the Center for Translational Research at the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute at the University of Washington-Seattle; Director of Client Services at the AIDS Project Los Angeles; and the founding and inaugural Program Director for Seven Generations Child and Family Counseling Services in Los Angeles. He has taught in clinical graduate programs at the UW School of Social Work, the Antioch University Seattle, the Phillips Graduate Institute, Alliant International University Los Angeles, Antioch University Los Angeles, and Loyola Marymount University. He has served as a consultant and advisor to the CDC, HRSA, SAMHSA, the Native American AIDS Prevention Center (NAAPC), the US–Mexico Border Health Association (PAHO/WHO), and numerous NGOs and non-profits delivering health services to tribal and indigenous communities nationally and internationally.

Rose Weahkee, a member of the Diné Nation, is the Director of the Office of Urban Indian Health Programs, Indian Health Service (IHS). Dr. Weahkee provides oversight of operations related to Title V of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act and health care services provided to American Indians and Alaska Natives who reside in urban areas across the nation. She previously served as the Phoenix Area IHS Director of Field Operations, the IHS Division of Behavioral Health Director, a California Area IHS Behavioral Health Consultant, and the Administrative Clinical Director for United American Indian Involvement. Dr. Weahkee received her Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology from Loyola Marymount University and her masters and doctoral degrees in clinical psychology from the California School of Professional Psychology.

Sam Bent Weber is a Program Analyst through DRT Strategies with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Law Program, which is housed at the Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Support. She specializes in work to improve public health through the development of legal tools for, and the provision of legal technical assistance to, state, tribal, local, and territorial governments, as well as public health officials at the CDC. Sam is also the lead researcher for PHLP’s Health Equity portfolio. Sam is a licensed member of the State Bar of Georgia. She earned her Juris Doctor from Harvard Law School and her Bachelor of Arts from Harvard College in Social Studies and African American Studies. She completed a postdoctoral fellowship with the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Theda New Breast ‘Makoyohsokoyi’ (Amskapipikuni [Blackfeet] from The Blackfoot Confederacy), Master Indigenous Trainer/Facilitator, Native Wellness Institute and Board Member, Sovereign Bodies Institute

Ninez Ponce, Professor of Health Policy & Management & Director, UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, University of California Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health

Kevin English, Director, Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center

Elizabeth Carr (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians), Senior Native Affairs Advisor, National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center

Antony Stately (Ojibwe/Oneida), Chief Executive Officer, Native American Community Clinic

Chester L. Antone (Tohono O’odham Nation), Member, Governing Body, Tohono O’odham Nation Health Care; Felina Cordova-Marks (Hopi), Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Arizona (UAZ), UAZ Cancer Center; Miguel Flores, Jr. (Pascua Yaqui Tribe and the Tohono O’odham Nation), Chief Executive Officer, Holistic Wellness Counseling and Consultant Services and Chairman, UAZ, American Indian Research Center for Health, Community Advisory Committee; Patrisia Gonzales (Kickapoo, Comanche and Macehual), Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, University of Arizona, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Mexican American Studies; Michelle Kahn-John (Diné), Clinical Associate Professor, UAZ, College of Nursing; and Teshia G. Arambula Solomon (Choctaw/Mexican-American), Associate Professor and Distinguished Outreach Faculty, UAZ, College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine

Debra O’Gara (Djik Sook; Cedar Bark House of the Teeyhittaan Clan of Wrangell), Pro Tem Judge, Tlingit and Haida Tribal Court and Senior Policy Specialist, Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center

Rose Weahkee (Diné), Director, Indian Health Service, Office of Urban Indian Health Programs

Contributor Information

Delight E. Satter, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Laura M. Mercer Kollar, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Debra O’Gara ‘Djik Sook’, Alaska Native Women’s Resource Center.

References

- 1.“The use of the term two-spirit has been known to facilitate an individual’s reconnection with tribal understandings of non-binary sexual and gender identities, as well as traditional spiritual or ceremonial roles that two spirits have held, thus reaffirming their identities ….” Elm Jessica H. L. et al. , “I’m in This World for a Reason”: Resilience and Recovery Among American Indian and Alaska Native Two-Spirit Women, 20 J. Lesbian Stud 352, 353 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (citing Walters Karina L. et al. , “My Spirit in My Heart”: Identity Experiences and Challenges Among American Indian Two-Spirit Women, 10 J. Lesbian Stud 125 (2006); [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Walters Karina L. et al. , Sexual Orientation Bias Experiences and Service Needs of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgendered, and Two-Spirited American Indians, 13 J. Gay & Lesbian Soc. Servs 133 (2001); [Google Scholar]; Wilson Alex, How We Find Ourselves: Identity Development and Two-Spirit People, 66 Harv. Educ. Rev 303 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 2. The authors recognize that, while the term MMIP is used, this work is complex and evolving. Other terms commonly used may include, but are not limited to, missing or murdered indigenous women (MMIW) and missing or murdered indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people (MMIWG2S).

- 3.World Health Org., World Report on Violence and Health 4 (Krug Etienne G. et al. , eds., 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Preventing Adverse Childhood Experience: Leveraging the Best Available Evidence 8 (2019); [Google Scholar]; Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Preventing Multiple Forms of Violence: A Strategic Vision for Connecting the Dots 5 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (last reviewed Jan. 28, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/publichealthapproach.html.

- 6.Wilkins Natalie et al. , Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Connecting the Dots: An Overview of the Links Among Multiple Forms of Violence 5 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (last reviewed Jan. 28, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- 8.Norris Tina, Vines Paula L. & Hoeffel Elizabeth M., U.S. Census Bureau, the American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010, at 13 (2012).

- 9.Disparities, Indian Health Serv. (Oct. 2019), https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neel Lisa, IHS Signs New Agreement Supporting Information-Sharing to Tribal Organization, Indian Health Serv. (Aug. 23, 2019), https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/ihs-blog/august2019/ihs-signs-new-agreement-supporting-information-sharing-to-tribal-organization/; [Google Scholar]; Swan Judith et al. , Cancer Screening and Risk Factor Rates Among American Indians, 96 AM. J. Pub. Health 340 (2006); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Burhansstipanov Linda & Satter Delight E., Office of Management and Budget Racial Categories and Implications for American Indians and Alaska Natives, 90 AM. J. Pub. Health 1720 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowing Tribal Health, Ass’n of State and Territorial Health Officials, https://www.astho.org/Programs/Health-Equity/Tribal-Health-Primer/ (last visited Aug. 11, 2020).

- 12.Carrillo Jo, Identity as Idiom: Mashpee Reconsidered, 28 Ind. L. Rev 545 (1995); [Google Scholar]; Mancari Morton v., 417 U.S. 535, 553 n.24 (1974).

- 13.Ponce Ninez et al. , Improving Data Capacity for American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) Populations in Federal Health Surveys 11 (2019).

- 14.National Vital Statistics System, Ctrs. for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/index.htm (last visited Mar. 15, 2021); [PubMed]; National Violent Death Reporting System, Ctrs. for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nvdrs/index.html (last visited Mar. 15, 2021);; The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, Ctrs. for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nisvs/index.html (last visited Mar. 15, 2021).

- 15.Ctrs. for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Works to Address Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native People.

- 16. Id.

- 17.Smith Sharon G. et al. , Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 State Report 3 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan Rachel E. & Oudekerk Barbara A., U.S. Dep’t of Just., Office of Justice Programs, Criminal Victimization, 2018 (2019); [Google Scholar]; Weaver Hilary N. et al. , The Colonial Context of Violence: Reflections on Violence in the Lives of Native American Women, 24 J. Interpersonal Violence 1552 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly Michele et al. , Identification in a Time of Invisibility for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 35 Stat. J. IAOS 71 (2019); [Google Scholar]; Madden Richard et al. , Indigenous Identification: Past, Present and a Possible Future, 35 Stat. J. IAOS 23 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly et al. , supra note 18.

- 21. Id.

- 22.Stone Laurie, Native Energy: Rural Electrification on Tribal Lands, Rocky Mountain Inst. (June 24, 2014), https://rmi.org/blog_2014_06_24_native_energy_rural_electrification_on_tribal_lands/. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Consumer & Gov’t Affairs Bureau, Wireless Telecomm. Bureau & Wireline Competition Bureau, Fed. Commc’ns Comm’n, Report on Broadband Deployment in Indian Country, Pursuant to the Repack Airwaves Yielding Better Access for Users of Modern Services Act of 2018 (2019) (report submitted to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation and House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce).

- 24.Lucchesi Annita & Echo-Hawk Abigail, Urban Indian Health Inst., Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls: A Snapshot of Data from 71 Urban Cities in the United States 6 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan & Oudekerk, supra note 17.

- 26.Connolly et al. , supra note 18; [Google Scholar]; Jacobs Bette, Indigenous Identity: Summary of Future Directions, 35 Stat. J. IAOS 147 (2019); [Google Scholar]; Ponce et al. , supra note 13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly et al. , supra note 18;; Madden et al. , supra note 18.

- 28.Connolly et al. , supra note 18;; Jacobs Bette et al. , At the Intersection of Health and Justice: How the Health of American Indians and Alaska Natives is Disproportionately Affected by Disparities in the Criminal Justice System, 6 Belmont L. Rev 41 (2019); [Google Scholar]; Lucchesi & Echo-Hawk, supra note 23.

- 29.Native Americans and the U.S. Census: How the Count has Changed, USA Facts (updated Jan. 20, 2020), https://usafacts.org/articles/native-americans-and-us-census-how-count-has-changed/.

- 30.See AskCHIS, Cal. Health Interview Survey, http://ask.chis.ucla.edu/AskCHIS/tools/_layouts/AskChisTool/home.aspx#/results (last visited Aug. 11, 2020).

- 31.Exec. Order No. 13,898, 84 Fed. Reg. 66059 (Dec. 2, 2019).

- 32.U.S. Comm’n Civ. Rights, Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans (Cozart Sheryl et al. eds. 2018) [hereinafter Broken Promises]. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Id.

- 34.Combating Domestic Violence, Weekly Columns, Congressman Tom Cole (Oct. 23, 2019), https://cole.house.gov/media-center/weekly-columns/combating-domestic-violence.

- 35.Exec. Order No. 13,898, 84 Fed. Reg. 66059 (Dec. 2, 2019).

- 36.Wilkins et al. , supra note 6.

- 37.Ledesma Rita, The Urban Los Angeles Urban American Indian Experience: Perspectives from the Field, 16 J. Ethnic & Cultural Diversity Soc. Work 27 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waltman Jennifer A., Working with Native American Patients & Clients—The 3 C’s, Minn. Psych. Ass’n (Sept. 30, 2016), https://www.mnpsych.org/index.php?option=com_dailyplanetblog&view=entry&category=event%20recap&id=161:working-with-native-american-patients-clients-the-3-c-s. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Development of the National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2030, Office of Disease Prevention & Health Promotion, HealthyPeople.gov, https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Healthy-People-2030 (last visited Aug. 31, 2020).

- 40.Fast Facts: High School Graduation Rates, Nat’l Ctr. for Educ. Stat, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=805 (last visited Aug. 11, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gone Joseph P. et al. , The Impact of Historical Trauma on Health Outcomes for Indigenous Populations in the USA and Canada: A Systematic Review, 74 Am. Psych 20 (2019); [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bombay Amy et al. , The Intergenerational Effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the Concept of Historical Trauma, 51 Transcultural Psychiatry 320 (2014); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brockie Teresa N. et al. , A Framework to Examine the Role of Epigenetics in Health Disparities Among Native Americans, 2013 Nursing Res. & Prac 1 (2013); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evans-Campbell Teresa, Historical Trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska Communities: A Multilevel Framework for Exploring Impacts on Individuals, Families, and Communities, 23 J. Interpersonal Violence 316 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henson Michele et al. , Identifying Protective Factors to Promote Health in American Indian and Alaska Native Adolescents: A Literature Review, 38 J. Primary Prevention 5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Technical Packages for Violence Prevention: Using Evidence-Based Strategies in your Violence Prevention Efforts, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (last reviewed Dec. 6, 2018), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/technical-packages.html.

- 44. See id.

- 45.See Exec. OrderNo. 13,898, 84 FR 66059 (Dec. 12, 2019);Fisher Linford D., Why shall wee have peace to bee made slaves: Indian Surrenderers During and After King Philip’s War, 64 Ethnohistory 91 (2018); [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Castillo Elias, A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions (2015); [Google Scholar]; Gallay Alan, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeBruyn Lemyra et al. , Child Maltreatment in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities: Integrating Culture, History, and Public Health for Intervention and Prevention, 6 Child Maltreatment 89 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]