Abstract

Objective/Background:

Obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for stroke. This study sought to assess the relationship between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and wake-up strokes (WUS), that is, stroke symptoms that are first noted upon awakening from sleep.

Patients/methods:

In this analysis, 837 Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project participants completed an interview to ascertain stroke onset during sleep (WUS) versus wakefulness (non-wake-up stroke, non-WUS). A subset of 316 participants underwent a home sleep apnea test (HSAT) shortly after ischemic stroke to assess for OSA. Regression models were used to test the association between OSA and WUS, stratified by sex.

Results:

Of 837 participants who completed the interview, 251 (30%) reported WUS. Among participants who underwent an HSAT, there was no significant difference in OSA severity [respiratory event index (REI)] among participants with WUS [median REI 17, interquartile range (IQR) 10, 29] versus non-WUS (median REI 18, IQR 9, 30; p = 0.73). OSA severity was not associated with increased odds of WUS among men [unadjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.011, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.995, 1.027] or women (unadjusted OR 0.987, 95% CI 0.959, 1.015). These results remained unchanged after adjustment for age, congestive heart failure, body mass index, and pre-stroke depression in men (adjusted OR 1.011, 95% CI 0.994, 1.028) and women (adjusted OR 0.988, 95% CI 0.959, 1.018).

Conclusions:

Although OSA is a risk factor for stroke, the onset of stroke during sleep is not associated with OSA in this large, population-based stroke cohort.

Keywords: Wake-up stroke, Sleep-disordered breathing, Ischemic stroke, Home sleep apnea test, Obstructive sleep apnea

1. Introduction

The increased risk of stroke among patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [1–3] has been hypothesized to result from endothelial activation promoting thrombus formation, paradoxical embolism during apneas causing right-to-left shunt in patients with patent foramen ovale, increased sympathetic activity causing surges in blood pressure, and increased risk of atrial fibrillation [4,5]. Given the propensity for stroke to occur in the morning hours towards the end of nighttime sleep or shortly after awakening, a direct link between the presence of OSA and the occurrence of stroke during sleep has been proposed [4]. Such a relationship, if confirmed, may have important therapeutic implications, as OSA treatment may have a direct impact on preventing strokes during sleep. When symptoms of stroke during sleep are first noticed upon awakening, this phenomenon is commonly referred to as wake-up stroke (WUS). Wake-up stroke has been associated with a higher prevalence of moderate or severe OSA in a few prior studies [6], especially in men [7]. Our group has previously reported that WUS was not associated with OSA in women [8]. The goal of this study is to expand the previous findings in a new, larger cohort and to compare results between male and female participants with recent ischemic stroke.

2. Materials and methods

The Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project in Nueces County, Texas, is a population-based study of adults 45 years of age or older with stroke. Methods have been described in detail elsewhere [9]. Only ischemic stroke participants screened between November 11, 2016 and March 13, 2020 who themselves completed a baseline interview, including a question about whether the stroke occurred during sleep, are included in the current analysis. Pre-stroke OSA risk was assessed with the Berlin Questionnaire [10]. Demographic information, initial NIH stroke scale score (NIHSSS), and co-morbidities were ascertained from medical records. BASIC participants who were not using supplemental oxygen, mechanical or positive pressure ventilation, and who were not pregnant were eligible for OSA screening with a home sleep apnea test (HSAT, ApneaLink Plus, Resmed Inc.) during their hospitalization or shortly after discharge (median 12 days, interquartile range 6, 21). HSATs with <2 h of valid data were excluded. Apneas were defined as nasal pressure decrease ≥80% from baseline for ≥10 s, and hypopneas as nasal pressure decrease ≥30% compared to baseline, lasting for ≥10 s and associated with a ≥4% drop in oxygen saturation. If oximetry data were missing, hypopneas were defined by nasal pressure decrease ≥50% for ≥10 s [11]. The respiratory event index (REI) was defined as the sum of all apneas and hypopneas divided by hours of recording. A registered polysomnography technologist reviewed automated scoring and made corrections where necessary [12]. OSA was defined as REI ≥10/hour, a cut-off at which the ApneaLink’s sensitivity and specificity compared to in-lab polysomnography are 0.98 and 1.0, respectively [13]. Although obstructive sleep apnea is more common than central sleep apnea after stroke [14,15], central apneas detected with ApneaLink Plus® also have been shown to be very highly correlated with central apneas detected on gold-standard, in-lab polysomnography (r = 0.94, p < 0.001) [16]. Mild-to-moderate OSA was defined as REI 10‒30/hour, severe OSA as REI ≥30/hour. Chi-square, Fisher exact, and t-tests were used to compare characteristics of study participants by WUS and non-WUS subgroups. Logistic regression models were used to test the association between OSA and WUS stratified by sex. We assessed the crude association, and the association adjusting for age (continuous), congestive heart failure, BMI (continuous), and pre-stroke depression. These potential confounders were selected a priori. Pre-stroke depression was considered a potential confounder due to the relationship between depression and short sleep duration [17–19], which we have previously confirmed in the BASIC cohort [20] and which could decrease the likelihood of stroke onset during sleep compared to wakefulness. Logistic regression models were also used to assess the association between WUS and OSA as a categorical variable (absent versus present, or as absent versus mild-moderate versus severe; the latter analysis was only performed as an unadjusted model due to sample size limitation). We confirmed the appropriate functional form of the continuous variables (age and BMI) in each sex-stratified model via the link test [21]. Written informed consent was provided by all participants. The University of Michigan and Corpus Christi hospital systems Institutional Review Boards approved this project.

3. Results

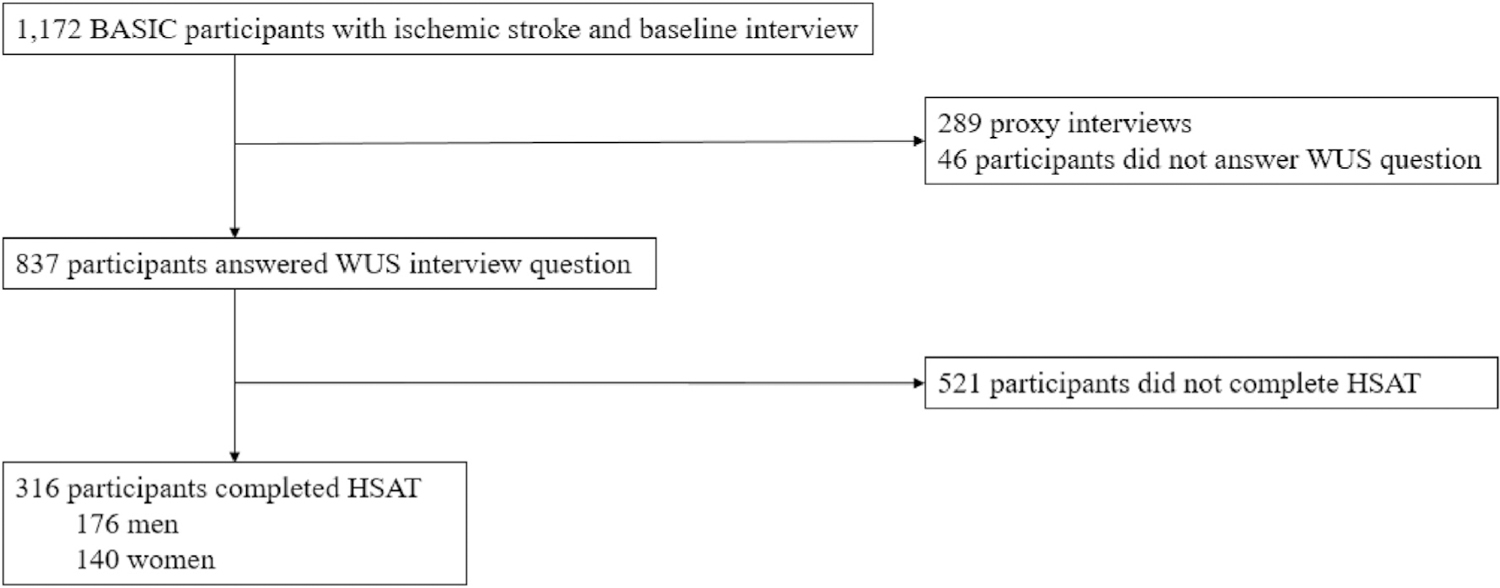

Of 883 BASIC participants who completed the baseline patient interview, 837 provided information regarding the timing of stroke symptom onset (Fig. 1). WUS occurred in 251 (30%) of these participants. Participants with WUS did not differ from non-WUS participants with regards to demographics, traditional stroke risk factors, BMI, NIHSSS, or prestroke risk of OSA (all p-values > 0.13, see supplemental material). A subset of 316 participants (102 WUS and 214 non-WUS) completed an HSAT and was comparable to the larger cohort with regards to baseline characteristics. In this subset, no difference was identified in demographics, NIHSSS, or medical co-morbidities between participants with and without WUS (Table 1). Among participants who underwent HSATs, 25% did not have OSA, 49% had mild-to-moderate OSA, and 26% had severe OSA. Distribution of OSA severity did not differ between individuals with WUS and non-WUS (p = 0.77).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants who completed HSATs.

| Entire cohort n = 316 |

WUS n = 102 |

Non-WUS n = 214 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic information | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 63.0 (55.0, 70.0) | 61.0 (53.0, 70.0) | 64.0 (55.0, 70.0) | 0.2287 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 176 (55.7%) | 56 (54.9%) | 120 (56.1%) | 0.8444 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.4048 | |||

| Mexican American | 199 (63.0%) | 59 (57.8%) | 140 (65.4%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 88 (27.9%) | 30 (29.4%) | 58 (27.1%) | |

| African American | 24 (7.6%) | 11 (10.8%) | 13 (6.1%) | |

| Other | 5 (0.6%) | 2 (2.0%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 279 (88.6%) | 92 (90.2%) | 187 (87.8%) | 0.5306 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 177 (56.2%) | 54 (52.9%) | 123 (57.8%) | 0.4212 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 166 (52.7%) | 56 (54.9%) | 110 (51.6%) | 0.5878 |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 17 (5.4%) | 4 (3.9%) | 13 (6.1%) | 0.4226 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 78 (24.8%) | 21 (20.6%) | 57 (26.8%) | 0.2350 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 25 (7.9%) | 8 (7.8%) | 17 (8.0%) | 0.9662 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 85 (26.9%) | 32 (31.4%) | 53 (24.8%) | 0.2156 |

| Alcoholic drinks per week | 0.9557 | |||

| None | 65 (20.6%) | 21 (20.6%) | 44 (20.6%) | |

| <1 | 147 (46.5%) | 46 (46.5%) | 101 (47.2%) | |

| 1–14 | 87 (27.5%) | 30 (29.4%) | 57 (26.6%) | |

| >14 | 17 (5.4%) | 5 (4.9%) | 12 (5.6%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 29.9 (26.5, 34.7) | 29.7 (26.4, 33.8) | 30.1 (26.5, 34.8) | 0.6075 |

| History of prior stroke/TIA, n (%) | 95 (30.2%) | 31 (30.4%) | 64 (30.1%) | 0.9502 |

| Prestroke depression, n (%) | 119 (37.7%) | 45 (44.1%) | 74 (34.6%) | 0.1018 |

| Prestroke sleep duration | ||||

| Total hours, median (IQR) | 7.0 (5.5, 8.0) | 6.5 (5.0, 8.0) | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 0.3168 |

| Short (≤6 h), n (%) | 147 (46.5%) | 51 (50.0%) | 96 (44.9%) | 0.6359 |

| Normal (7‒8 h), n (%) | 129 (40.8%) | 40 (39.2%) | 89 (41.5%) | |

| Long (≥9 h), n (%) | 40 (12.7%) | 11 (10.8%) | 29 (13.6%) | |

| Prestroke high risk of sleep apnea,a n (%) | 216 (68.3%) | 65 (64.7%) | 150 (70.9%) | 0.3357 |

| NIHSSS, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 0.9717 |

| Sleep apnea test results | ||||

| REI, median (IQR) | 18.0 (9.0, 30.0) | 17.0 (10.0, 29.0) | 18.0 (9.0, 30.0) | 0.7290 |

| Sleep Disordered Breathing Severity, n (%) | 0.7694 | |||

| REI < 10 | 80 (25.3%) | 24 (23.5%) | 56 (26.1%) | |

| REI 10‒30 | 155 (49.1%) | 53 (52.0%) | 102 (47.7%) | |

| REI ≥ 30 | 81 (25.6%) | 25 (24.5%) | 56 (26.2%) | |

| Oxygen Desaturation Index (median, IQR) | 10.0 (5.0, 20.0) | 10.0 (5.0, 20.0) | 10.5 (5.0, 20.0) | 0.7313 |

| Central Apnea Index (median, IQR) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.5) | 0.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.2287 |

| Lowest desaturation, (median, IQR) | 84 (79, 89) | 85 (78, 89) | 84 (79, 89) | 0.9591 |

HSAT ‒ home sleep apnea test, OSA ‒ obstructive sleep apnea, NIHSSS ‒ National Institute of Health Stroke Scale score, BMI ‒ body mass index, REI ‒ respiratory event index.

Note, prestroke high risk of sleep apnea was based on Berlin Questionnaire score as described in the methods section. Lowest desaturation refers to the lowest oxygen saturation value within all desaturations.

In unadjusted analysis, REI was not associated with WUS in women {odds ratio [OR] 0.987 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.959, 1.015]} but was almost significant in men [OR 1.011, (95% CI: 0.995, 1.27)]. Results were similar after adjustment for age, congestive heart failure, BMI and pre-stroke depression [men: OR 1.011 (95% CI: 0.994, 1.028); women: OR 0.988 (95% CI: 0.959, 1.018)]. Similarly, in unadjusted analysis, binary OSA was not associated with WUS in men [OR 1.664 (95% CI: 0.728, 3.802)] or in women [OR 0.833 (95% CI: 0.389, 1.783)]. Results were similar in men after adjustment for age, congestive heart failure, BMI and pre-stroke depression but attenuated in women [men: OR 1.702 (95% CI: 0.709, 4.086); women: OR 0.963 (95% CI: 0.44, 2.108)]. Furthermore, in unajusted analysis, among men, neither mild/moderate OSA [OR 1.763 (95% CI: 0.735, 4.225)] nor severe OSA [OR 1.526 (95% CI: 0.599, 3.886)] was associated with WUS. Similarly, in unadjusted analysis, among women, neither mild/moderate OSA [OR 0.882 (95%CI: 0.397, 1.958)] nor severe OSA [OR 0.700 (95% CI: 0.238, 2.056)] was associated with WUS, although the point estimates were in the opposite direction from that observed among men.

4. Discussion

In this sizeable population-based study of individuals with recent ischemic stroke, 30% of participants reported WUS. Prevalence and severity of OSA in a studied subsample did not differ by WUS status overall, or among men or women specifically, with or without adjustment for confounders. Moreover, without adjustment, even severe OSA was not associated with WUS status.

The overall prevalence of WUS in our cohort was consistent with six previous reports on OSA and WUS [7,8,22–25]. Our group previously reported no association between WUS and OSA in a subcohort of female BASIC participants enrolled before May, 2016 [8]. The present report confirms our earlier findings, now in both men and women, in a separate BASIC subcohort of participants recruited after November, 2016. Our current results are also in line with one additional study that did not find an association between WUS and OSA [24].

In contrast, four out of a total of six previously published studies identified an association between WUS and OSA [22,23,25], though this relationship was restricted to men with severe OSA in one of these studies [7]. Given this sex-specific finding, we performed predefined analyses stratified by sex and, post-hoc, examined OSA as a categorical variable. The point estimates by sex were in the opposite direction for the categorical OSA predictor, with an increased OR for WUS in men with OSA and decreased OR in women with OSA, but this result did not reach statistical significance. The lack of significant associations seems unlikely a result of insufficient sample size, as our cohort is the largest overall, has the largest number of male participants, and the second largest number of participants with severe OSA among all published studies. Of note though, it is possible that the magnitude of the association is smaller in our population-based cohort compared to previous hospital-based cohorts, and therefore our study may be relatively underpowered despite its large number of study participants.

The difference between our results and some of those published by others may be explained by differences in study cohorts: the current data were derived from a population-based study, and assessment of WUS was based only on systematic interview of participants. Previous studies included data ascertained from family members or chart abstraction [7,22,23] and none was population-based [7,22–24]. Race and ethnicity of participants also likely differed significantly among studies, as the majority of our participants were Mexican American. Previous reports recruited stroke patients from Taiwan [22], Slovakia [23], Brazil [24], China [25], as well as Connecticut and Indiana [7], which likely resulted in different racial/ethnic composition of participants, though this demographic information was not always included in the publications. In contrast, populations were relatively comparable in terms of age, BMI, NIHSSS, and OSA severity. Timing of sleep apnea testing after stroke was also comparable to that reported in previous studies [22–24], with the exception of one report in which all participants were tested within seven days of stroke [25], and one study in which most participants were tested more than one month after stroke [7].Publication bias may have contributed to the higher proportion of studies that reported significant differences between groups.

The strengths of our study include the assessment of WUS in a large, ethnically diverse, population-based cohort. The large sample size allowed for sex-stratified analyses with adjustment for multiple potential confounders. We directly queried WUS using a systematically administered question, which included the assessment of WUS during non-nocturnal sleep periods.

Limitations of this study include assessment for OSA by use of HSATs, which may underestimate its severity. However, ApneaLink has a high sensitivity and specificity, and recordings were manually reviewed by a technologist [12]. Since the same type of HSAT device was used in patients with and without WUS, HSAT is an unlikely source of bias. Our exclusion of BASIC participants who could not answer WUS interview questions may have introduced selection bias, perhaps differentially by sex, but also likely provided the most accurate data on stroke onset timing through avoidance of proxy responses. This study did not address the relationship among etiologic stroke subtype, WUS and OSA as reported on by others [7,26,27]; however ischemic stroke subtype is not differentially associated with post-stroke OSA [28]. Information about patent foramina ovalia [7,29] was not available. Owing to the study’s design as a population-based surveillance study of stroke patients, information about pre-stroke sleep apnea test results is not available, and therefore we cannot rule out that some of our participants developed sleep apnea after stroke. Data on stroke treatment were not available, though stroke treatment may have an impact on HSAT results. Furthermore, due to the limitations of home sleep apnea testing, hypopneas were not classified as obstructive versus central, which precludes a separate analysis of participants with central versus obstructive sleep apnea. Lastly, stroke severity was relatively mild, which limits the generalizability of the results.

In short, WUS was not associated with OSA prevalence or severity in our large, ethnically diverse cohort of male and female participants with recent ischemic stroke. However, these results do not replicate previous reports of increased risk of WUS in OSA, in particular among men and those with severe OSA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was performed at Corpus Christi Medical Center and CHRISTUS Spohn hospitals, CHRISTUS Health system, Corpus Christi, Texas.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01HL098065, R01NS070941, R01HL126700, and R01NS038916].

Abbreviations:

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- HSAT

Home Sleep Apnea Test

- NIHSSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score

- Non-WUS

Non-Wake-up stroke

- OSA

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- WUS

Wake-up stroke

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sonja G. Schütz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Lynda D. Lisabeth: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition. River Gibbs: Methodology, Formal analysis. Xu Shi: Methodology, Formal analysis. Erin Case: Investigation, Project administration. Ronald D. Chervin: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Devin L. Brown: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Chervin had several disclosures.

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.010.

References

- [1].Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2034–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:269–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kendzerska T, Leung RS, Atzema CL, et al. Cardiovascular consequences of obstructive sleep apnea in women: a historical cohort study. Sleep Med 2020;68:71–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Peter-Derex L, Derex L. Wake-up stroke: from pathophysiology to management. Sleep Med Rev 2019;48:101212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ciccone A, Proserpio P, Roccatagliata DV, et al. Wake-up stroke and TIA due to paradoxical embolism during long obstructive sleep apnoeas: a cross-sectional study. Thorax 2013;68:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xiao Z, Xie M, You Y, et al. Wake-up stroke and sleep-disordered breathing: a meta-analysis of current studies. J Neurol 2018;265:1288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Koo BB, Bravata DM, Tobias LA, et al. Observational study of obstructive sleep apnea in wake-up stroke: the SLEEP TIGHT study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;41: 233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brown DL, Li C, Chervin RD, et al. Wake-up stroke is not associated with sleep-disordered breathing in women. Neurol Clin Pract 2018;8:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Sanchez BN, et al. Persistent ischemic stroke disparities despite declining incidence in Mexican Americans. Ann Neurol 2013;74:778–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, et al. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].ApneaLink TM systems clinical guide [online]. Available at: www.resmed.com.

- [12].Brown DL, Chervin RD, Hegeman G 3rd, et al. Is technologist review of raw data necessary after home studies for sleep apnea? J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10: 371–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ng SSSCT-O, To K-W, Ngai J, et al. Validation of a portable recording device (ApneaLink) for identifying patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Intern Med J 2009;39:757–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seiler A, Camilo M, Korostovtseva L, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing after stroke and TIA: a meta-analysis. Neurology 2019;92:e648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schutz SG, Lisabeth LD, Hsu CW, et al. Central sleep apnea is uncommon after stroke. Sleep Med 2020;77:302–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].ApneaLink Plus white paper. Australia: Bella Vista; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Furihata R, Uchiyama M, Suzuki M, et al. Association of short sleep duration and short time in bed with depression: a Japanese general population survey. Sleep Biol Rhythm 2014;13:136–45. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sun Y, Shi L, Bao Y, et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep duration and depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly individuals: evidence from a longitudinal study. Sleep Med 2018;52:221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008;10:473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dong L, Brown DL, Chervin RD, et al. Pre-stroke sleep duration and post-stroke depression. Sleep Med 2020;77:325–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pregibon D Goodness of link tests for generalized linear models. Appl Statist 1980;29:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hsieh SW, Lai CL, Liu CK, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea linked to wake-up strokes. J Neurol 2012;259:1433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Siarnik P, Kollar B, Carnicka Z, et al. Association of sleep disordered breathing with wake-up acute ischemic stroke: a full polysomnographic study. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12:549–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barreto PR, Diniz DLO, Lopes JP, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and wake-up stroke - a 12 Months prospective longitudinal study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020;29:104564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fu X, Li J, Wu JJ, et al. Reduced cortical arousability to nocturnal apneic episodes in patients with wake-up ischemic stroke. Sleep Med 2020;66: 252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Park J, Yeo M, Kim J, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and wake-up stroke: a differential association depending on etiologic subtypes. Sleep Med 2020;76: 43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tanimoto A, Mehndiratta P, Koo BB. Characteristics of wake-up stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;23:1296–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Brown DL, Mowla A, McDermott M, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype and presence of sleep-disordered breathing: the BASIC sleep apnea study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Man H, Xu Y, Zhao Z, et al. The coexistence of a patent foramen ovale and obstructive sleep apnea may increase the risk of wake-up stroke in young adults. Technol Health Care 2019;27:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.