Abstract

Background

Hypertension induces systemic inflammation, but its impact on the outcome of infectious diseases like tuberculosis (TB) is unknown. Calcium channel blockers (CCB) improve TB treatment outcomes in preclinical models, but their effect in patients with TB remain unclear.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study, including all patients > 18 years receiving treatment for culture-confirmed, drug-sensitive TB from 2000 to 2016 at the National Taiwan University Hospital, assessed the association of hypertension and CCB use with all-cause and infection-related mortality during the first 9 months of TB treatment, as well as sputum smear microscopy and sputum culture positivity at 2 and 6 months.

Results

Of the 2894 patients, 1052 (36.4%) had hypertension. A multivariable analysis revealed that hypertension was associated with increased mortality due to all causes (hazard ratio [HR], 1.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23–1.99) and infections (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.34–2.6), but there were no statistical differences in microbiological outcomes when stratified based on hypertensive group. Dihydropyridine-CCB (DHP-CCB) use was associated only with reduced all-cause mortality (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, .45–.98) by univariable Cox regression. There were no associations between DHP-CCB use and infection-related mortality (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, .46–1.34) or microbiological outcomes in univariable or multivariable regression analyses.

Conclusions

Patients with hypertension have increased all-cause mortality and infection-related mortality during the 9 months following TB treatment initiation. DHP-CCB use may lower all-cause mortality in TB patients with hypertension. The presence of hypertension or the use of CCB did not result in a significant change in microbiological outcomes.

Keywords: tuberculosis, hypertension, calcium channel blockers, mortality, treatment outcomes

Hypertension is associated with increased all-cause and infection-related mortality during the first 9 months after tuberculosis treatment initiation, with no significant change in microbiological outcomes. Calcium-channel blocker (CCB) use may lower all-cause mortality in tuberculosis patients with hypertension.

Tuberculosis (TB) causes significant mortality worldwide, with approximately 1.5 million TB-related deaths in 2018, and nearly 90% of cases from developing countries [1]. Concurrently, the prevalence of hypertension has increased dramatically in many low- and middle-income countries, accounting for nearly 75% of global hypertension cases [2]. There is considerable overlap in countries with high burdens of TB and hypertension [3].

Patients with TB have a higher proportion of hypertension than controls without TB [4]. Multiple cohort studies have shown an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease following TB [4–6]. Hypertension is associated with systemic inflammation, including increased levels of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-18, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Although higher levels of proinflammatory mediators are associated with tissue destruction in preclinical models [7–9] and with a higher risk of advanced disease in patients with TB [10, 11], the precise effect of hypertension on TB treatment outcomes has not been studied in animal models or in clinical studies.

Calcium channel blockers (CCB) are first-line drugs in the treatment of hypertension. Blockage of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels has demonstrated improved mycobacterial clearance in preclinical studies [12]. Non–dihydropyridine CCBs (non–DHP-CCBs), like verapamil, function as efflux pump inhibitors, decreasing the bacillary load in macrophages and increasing the bactericidal activity of bedaquiline against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mouse models [13–16]. In contrast, dihydropyridine CCBs (DHP-CCBs), such as amlodipine or nifedipine, seemingly lack efflux pump inhibitor activity. The effect of CCB use on TB treatment outcomes in humans is unknown.

In this study, we evaluated the effects of hypertension and CCB use on 9-month all-cause mortality and infection-related mortality, as well as on sputum culture positivity, during standard treatment for drug-susceptible TB in a retrospective cohort in Taiwan.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We included all adults (aged >18 years) treated for drug-susceptible TB from 2000 to 2016 at the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH), a tertiary-care hospital in Taipei city. TB diagnosis was established by culture-based detection of M. tuberculosis in the sputum, using MGIT-960 and Lowenstein–Jensen medium. Repeat sputum cultures were performed at 2 and 6 months after initiating TB treatment [17]. Most patients were treated on an outpatient basis according to ATS guidelines [18]. There were no specific exclusion criteria. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Johns Hopkins University and NTUH. All data were obtained from the NTUH database.

Baseline Characteristics

Data on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, cancer, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, liver disease, autoimmune disease, smoking, alcohol abuse, transplantation (both solid organ and bone marrow transplantation), human immunodeficiency virus status, baseline sputum smear for acid-fast bacilli (AFB; 0 to 4+), cavitary disease on chest radiography, and prior TB history were obtained. Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) results were calculated from the variables obtained from the database [19].

Exposures

The 2 exposures assessed in our study were (1) hypertension, and (2) use of CCB among patients with hypertension. We defined hypertension at TB treatment initiation as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, according to the Joint National Committee–7 and American Heart Association guidelines from 2013 [20, 21]. A minimum of 2 weeks (14 doses) of CCB were taken as the required exposure: for DHP-CCB, this consisted of amlodipine (5 mg), felodipine (5 mg), lercanidipine (10 mg), nifedipine (30 mg), and nicardipine (60 mg); for non–DHP-CCB, it consisted of verapamil (240 mg) and diltiazem (120 mg). CCB exposure was assigned separately for intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses. Exposure for the intention-to-treat analysis was defined as any CCB use for at least 2 weeks in the first month of TB treatment, and for the per-protocol analysis was defined as the use of any CCB for ≥80% of the 9-month period following the initiation of TB treatment (7.2 months), or ≥80% of the duration of follow-up if loss to follow-up or death occurred before 9 months.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes evaluated were all-cause and infection-related mortality during the first 9 months of TB treatment. The latter was a composite outcome of death due to pneumonia, sepsis, or TB. Secondary outcomes included sputum smear and culture positivity at 2 and 6 months after treatment initiation.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics, stratified by hypertension and CCB exposure, were compared using 2-sided t-tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. A Kaplan-Meier analysis and a Cox regression were used to measure the association between hypertension and all-cause and infection-related mortality in separate models. Person-time at risk of outcome, stratified by hypertension status, was calculated from the time of TB treatment initiation until 9 months or loss to follow-up or death, whichever occurred first. The point of loss to follow-up was defined as the last study visit prior to 9 months. Sputum smear and culture positivity at 2 months were analyzed using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. Similarly, using separate univariable and multivariable Cox regression models, we measured the association of CCB use, classified according to the intention-to-treat and per-protocol definitions, and the type of CCB (DHP-CCB or non–DHP-CCB) with all-cause mortality and infection-related mortality. In order to appropriately assign CCB exposure, only patients who survived beyond the first month post-TB treatment initiation were included. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by: (1) including patients who died within the first month of TB treatment; and (2) excluding participants who did not receive the required dose of CCB from the comparison group. Potential confounders for multivariable analyses were identified by literature review and by exploratory univariable data analysis at P < .05 significance, depending on the exposure (hypertension status or CCB use) that was assessed. Confounding factors that are components of the CCI were not adjusted separately if the CCI was included in the multivariable analytical model. Missing data were not imputed if they were comparable between the exposed and unexposed groups. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA/IC 16.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Stratification Based on Hypertension Status

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Comorbidities

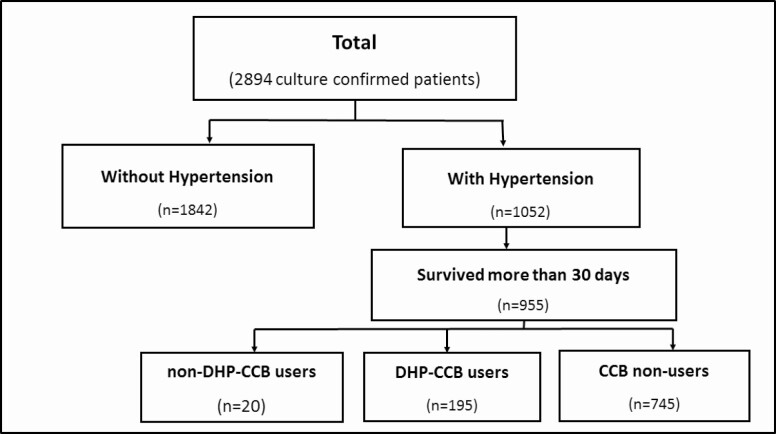

Of the total 2894 culture-confirmed, drug-sensitive pulmonary TB cases, 1052 patients (36.4%) had hypertension (Table 1; Figure 1). The median age was 66.6 years (interquartile range, 49.1–77.8), with a higher proportion of patients aged ≥65 years in the hypertensive group (78.0%) relative to the normotensive group (37.7%; P < .001). Approximately 40% of the total patient population were ever smokers, and 2.8% reported alcoholism, with no significant differences between patients with and without hypertension.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Participants, Stratified by Hypertension Status

| Sl.No | Study Characteristics | Measure | Total, N = 2894 | Without hypertension, n = 1842 | With hypertension, n = 1052 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age, y | Median (IQR) | 66.55 (49.06–77.77) | 56.77 (40.56 – 72.67) | 75.53 (66.55– 82.43) | <.001 |

| 2. | Age > 65 y | n (%) | 1516 (52.4%) | 695 (37.7%) | 821 (78.0%) | <.001 |

| 3. | Male sex | n (%) | 1975 (68.2%) | 1216 (66.0%) | 759 (72.2%) | .001 |

| 4. | BMI | Median (IQR) | 21.1 (18.8–23.4) | 20.6 (18.5 – 22.7) | 22.0 (19.3 – 24.5) | <.001 |

| 5. | Ever smoker | n (%) | 930 (40.5%) | 572 (40.2%) | 358 (41.0%) | .70 |

| 6. | Alcoholism | n (%) | 81 (2.8%) | 60 (3.3%) | 21 (2.0%) | .05 |

N = 2894.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for participant selection. Abbreviations: CCB, calcium channel blocker; DHP, dihydropyridine.

There were higher rates of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular accidents, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cirrhosis among patients in the hypertensive group (Table 2). The normotensive group had greater proportions of patients who were smear positive by microscopy at diagnosis (45.8% vs 37.4%, respectively; P < .001) and had cavitary disease at diagnosis (16.6% vs 10.3%, respectively; P < .001), compared to the hypertensive group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Associated Comorbidities of the Study Participants, Stratified by Hypertension Status

| Sl. No | Study characteristics | Measure | Total, N = 2894 | Without hypertension, n = 1842 | With hypertension, n = 1052 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | DM | n (%) | 533 (18.5%) | 212 (11.5%) | 321 (30.6%) | <.001 |

| 2. | Cancer | n (%) | 459 (15.9%) | 238 (12.9%) | 221 (21.1%) | <.001 |

| 3. | CKD stage ≥ 4 | n (%) | 128/2513 (5.1%) | 24/1519 (1.6%) | 104/994 (10.5%) | <.001 |

| 4. | Cardiovascular disease | n (%) | 352 (12.1%) | 98 (5.3%) | 254 (24.1%) | <.001 |

| CAD | n (%) | 291 (10.0%) | 81 (4.4%) | 210 (19.9%) | <.001 | |

| AMI | n (%) | 111 (3.8%) | 46 (2.5%) | 65 (6.2%) | <.001 | |

| CHF | n (%) | 123 (4.2%) | 28 (1.5%) | 95 (9.00%) | <.001 | |

| PVD | n (%) | 83 (2.9%) | 28 (1.5%) | 55 (5.2%) | <.001 | |

| 5. | Asthma | n (%) | 123 (4.2%) | 69 (3.7%) | 54 (5.1%) | .07 |

| 6. | COPD | n (%) | 451 (15.6%) | 223 (12.1%) | 228 (21.7%) | <.001 |

| 7. | Bronchiectasis | n (%) | 121 (4.2%) | 82 (4.5%) | 39 (3.7%) | .34 |

| 8. | Pneumoconiosis | n (%) | 35 (1.2%) | 22 (1.2%) | 13 (1.2%) | .92 |

| 9. | Autoimmune diseases | n (%) | 115 (4.0%) | 64 (3.5%) | 51 (4.9%) | .07 |

| 10. | Cirrhosis | n (%) | 50 (1.7%) | 29 (1.6%) | 21 (2.0%) | .40 |

| 11. | History of transplant | n (%) | 26 (.9%) | 10 (.5%) | 16 (1.5%) | .007 |

| 12. | HIV | n (%) | 65 (2.3%) | 54 (2.9%) | 11 (1.1%) | .001 |

| 13. | Charlson comorbidity index | Mean (SD) | 3.9 (2.7) | 3.0 (2.4) | 5.4 (2.4) | <.001 |

N = 2894. Denominators are mentioned when they are different from n.

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Tuberculosis Disease Characteristics of the Study Participants

| Sl. No | Study Characteristics | Measure | Total, N = 2894 | Without hypertension, n = 1842 | With hypertension, n = 1052 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sputum smear AFS positive at baseline | n (%) | 1215/2842 (42.8%) | 831/1817 (45.8%) | 384/1025 (37.4%) | <.001 |

| 2. | Sputum smear AFS grade at baseline | |||||

| 0 | … | 1627/2842 (57.3%) | 986/1817 (54.3%) | 641/1029 (39.4%) | <.001 | |

| 1+ | … | 390/2842 (13.7%) | 246/1817 (13.5%) | 144/1029 (14.1%) | ||

| 2+ | … | 318/2842 (11.2%) | 228/1817 (12.6%) | 90/1029 (8.8%) | ||

| 3+ | … | 241/2842 (8.5%) | 164/1817 (9.0%) | 77/1029 (7.5%) | ||

| 4+ | … | 266/2842 (9.4%) | 193/1817 (10.6%) | 73/1029 (7.1%) | ||

| 3. | Prior TB | n (%) | 98/1598 (6.1%) | 65/1040 (6.3%) | 33/558 (5.9%) | .79 |

| 4. | Cavity | n (%) | 413 (14.3%) | 305 (16.6%) | 108 (10.3%) | <.001 |

N = 2894. Denominators are mentioned when they are different from n.

Abbreviations: AFS, acid-fast smear; TB, tuberculosis.

Outcomes

Effect of Hypertension on 9-Month All-cause Mortality

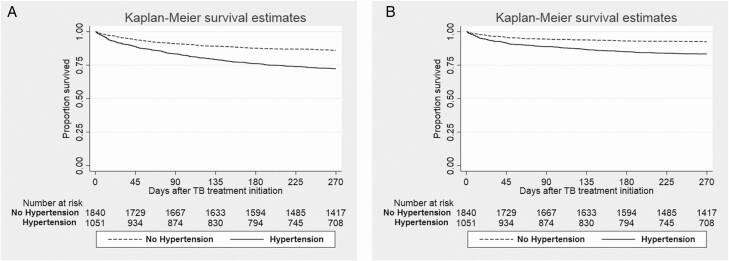

During the first 9 months after TB treatment initiation, there was significantly higher all-cause mortality in the hypertensive group (290/997 patients; 29.1%) than in the normotensive group (254/1670 patients; 15.2%; P < .001; Table 4). The log-rank test of the Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that patients with hypertension had significantly shorter survival compared to patients without hypertension (Figure 2A; P < .001). After adjusting for sex, BMI, sputum acid-fast stain at diagnosis, cavitary disease, past history of transplantation, and CCI, patients with hypertension had a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.57 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23–1.99) for all-cause mortality (Table 5). Other parameters found to be associated with increased 9-month all-cause mortality in the adjusted Cox regression models were male sex, lower BMI, sputum AFB smear positivity, and higher CCI score.

Table 4.

Outcomes in Patients With Tuberculosis, Stratified by Hypertension Status

| Sl. No | Study characteristics | Measure | Total, N = 2894 | Without hypertension, n = 1842 | With hypertension, n = 1052 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | All-cause mortality within 9 mo | n (%) | 544/2667 (20.4%) | 254/1670 (15.2%) | 290/997 (29.1%) | <.001 |

| 2. | Infection-related mortality within 9 mo | n (%) | 303/2667 (11.4%) | 135/1670 (8.1%) | 168/997 (16.9%) | <.001 |

| 3. | Sputum culture positive at 2 mo | n (%) | 265/1640 (16.2%) | 165/1020 (16.2%) | 100/620 (16.1%) | .980 |

| 4. | Sputum AFB smear positive at 2 mo | n (%) | 118/1640 (7.2%) | 81/1020 (7.9%) | 37/620 (6.0%) | .13 |

| 5. | Sputum culture positive at 6 mo | n (%) | 6/1551 (.4%) | 5/978 (.5%) | 1/573 (.2%) | .30 |

| 6. | Sputum AFB smear positive at 6 mo | n (%) | 1/1551 (.1%) | 1/978 (.1%) | 0/573 (0%) | .44 |

N = 2894. Denominators are mentioned when they are different from n.

Abbreviation: AFB, acid-fast bacilli.

Figure 2.

Survival analysis during 9 months of follow-up after TB treatment initiation in patients with and without hypertension. A. All-cause mortality. B. Infection-related mortality. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; TB, tuberculosis.

Table 5.

Crude and Adjusted Hazard Ratios, Based on Cox Regression Model, for All-cause and Infection-related Mortality During 9 Months After Initiation of Tuberculosis Treatment

| Characteristic | 9-mo all-cause mortality | 9-mo infection-related mortality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR | 95%CI | P value | Adjusted HRa | 95%CI | P value | Unadjusted HR | 95%CI | P value | Adjusted HRa | 95%CI | P value | |

| HTN | 2.15 | 1.81–2.54 | <.001 | 1.57 | 1.23 – 1.99 | <.001 | 2.30 | 1.83–2.89 | <.001 | 1.87 | 1.34–2.61 | <.001 |

| Sex | 1.75 | 1.42–2.14 | <.001 | 1.54 | 1.16–2.04 | .003 | 1.53 | 1.17–1.99 | .001 | 1.42 | .98–2.07 | .066 |

| BMI | .90 | .90–.96 | <.001 | .90 | .87–.93 | <.001 | .92 | .88–.96 | <.001 | .89 | .85–.93 | <.001 |

| Initial AFB | 1.03 | .97–1.10 | .294 | 1.11 | 1.03 – 1.21 | .008 | 1.07 | .98–1.16 | .122 | 1.16 | 1.04–1.29 | .007 |

| Cavitary disease | 1.09 | .87–1.38 | .456 | 1.27 | .93 – 1.72 | .129 | 1.12 | .82–1.52 | .496 | 1.26 | .83–1.92 | .272 |

| History of transplantation | 1.47 | .70–3.09 | .344 | 1.84 | .82 – 4.13 | .141 | 1.88 | .78–4.55 | .204 | 2.89 | 1.18–7.06 | .020 |

| CCI | 1.27 | 1.23–1.31 | <.001 | 1.25 | 1.20–1.30 | <.001 | 1.28 | 1.23–1.33 | <.001 | 1.25 | 1.18–1.33 | <.001 |

N = 2894. “Initial AFB” refers to the sputum AFB smear at the time of diagnosis.

Abbreviations: AFB, acid-fast bacilli; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; HTN, hypertension.

Effect of Hypertension on 9-Month Infection-related Mortality

During the first 9 months after TB treatment initiation, a total of 303/2667 patients (11.4%) died of infection-related causes, constituting 55.7% (303/544 patients) of all deaths during the first 9 months of TB treatment (Table 4). Of this group, 43 patients (14.2%) died due to TB-related causes, 124 patients (40.9%) due to pneumonia, and 136 patients (44.9%) due to sepsis. Hypertension had significantly earlier infection-related mortality by the log-rank test of the Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 2B; P < .001). After adjusting for confounders, patients with hypertension had a 1.87 times higher hazard of infection-related mortality during TB treatment (95% CI, 1.34–2.61; P < .001).

Effect of Hypertension on Microbiological Outcomes

Among the 2894 patients included in our study, 265/1640 patients (16.2%) and 6/1551 patients (0.4%) had positive sputum cultures at 2 and 6 months, respectively. There were no differences between hypertensive and normotensive patients in sputum culture positivity either at 2 months (16.1% vs 16.2%, respectively; P = .862) or 6 months (0.2% vs 0.6%, respectively; P = .216; Table 4). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models also showed no significant relationships between hypertension and sputum culture or microscopy positivity at 2 months (Supplementary Table 1A).

Stratification Based on CCB Use

Among the 955 hypertensive patients with follow-up more than 30 days after TB diagnosis, 195 patients (20.4%) received DHP-CCB and 20 patients (2.1%) received non–DHP-CCB, while 5 patients (0.5%) received both DHP-CCB and non–DHP-CCB. Of the 955 patients with hypertension, 54 (5.6%) of these patients were lost to follow-up during the first 9 months of treatment. The results of the per-protocol analyses are in Table 7. Baseline characteristics among CCB users and nonusers were not statistically different, except for a higher percentage of patients with prior TB among CCB users (13.3% vs 5.2%, respectively; P < .01).

Table 7.

Outcomes in Patients With Hypertension, Stratified by Dihydropyridine–Calcium Channel Blocker Use

| Sl. No | Study Characteristics | Measure | Total, n = 959 | All CCB use | DHP-CCB use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without CCB use, n = 745 | With CCB use, n = 210 | P value | Without CCB use, n = 745 | With DHP-CCB use, n = 195 | P value | ||||

| 1. | All-cause mortality within 9 mo | n (%) | 194/905 (21.4%) | 162/701 (23.1%) | 32/201 (16.0%) | .03 | 162/701 (23.1%) | 29/187 (15.2%) | .03 |

| 2. | Infection-related mortality within 9 mo | n (%) | 106/905 (11.7%) | 86/704 (12.3%) | 20/201 (10.0%) | .38 | 86/704 (12.2%) | 18/188 (9.6%) | .11 |

| 3. | Sputum AFB smear positive at 2 mo | n (%) | 36/616 (5.8%) | 32/474 (6.8%) | 4/142 (2.8%) | .08 | 32/474 (6.6%) | 4/131 (3.1%) | .11 |

| 4. | Sputum AFB smear positive at 6 mo | n (%) | 0/569 (0%) | 0/443 (0%) | 0/126 (0%) | - | 0/443 (0%) | 0/117 (0%) | - |

| 5. | Sputum culture positive at 2 mo | n (%) | 99/616 (16.1%) | 75/474 (15.8%) | 24/142 (16.8%) | .76 | 77/474 (15.8%) | 22/131 (16.8%) | .79 |

| 6. | Sputum culture positive at 6 mo | n (%) | 1/569 (.2%) | 0/443 (0%) | 1/126 (.2%) | .59 | 0/443 (0%) | 1/117 (.2%) | .607 |

N = 2894. Denominators are mentioned when they are different from n.

Abbreviations: AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CCB, calcium channel blocker; DHP, dihydropyridine.

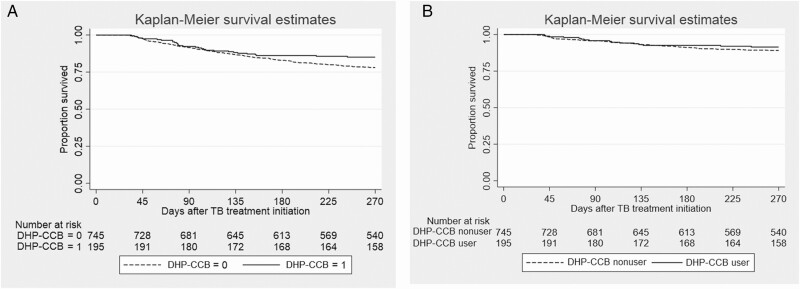

Stratification of Hypertensive Patients Based on CCB Use

Of the total 955 hypertensive patients, 210 patients (77.9%) received the required dose of either CCB type (DHP or non-DHP). Among them, 32/201 patients (16.0%) died of any cause and 29/187 patients (15.4%) died of infection-related causes. Univariable Cox-regression shows an HR of 0.68 (95% CI, .47–.99) for all-cause mortality in patients who received any CCB (Table 8). A multivariable analysis adjusting for sex and history of prior TB did not yield a significant association with all-cause mortality. An intention-to-treat analysis revealed no significant difference in time to all-cause mortality between CCB users and nonusers (Supplementary Table 2). A univariable analysis and multivariable analysis did not yield a significant association for infection-related mortality during the first 9 months of TB treatment. The chi-square test (Table 7) and univariable and multivariable logistic regression (Supplementary Table 1B) revealed no association between CCB use and microbiological outcomes.

Table 8.

Crude and Adjusted Hazard Ratios, Based on Cox Regression Model, for All-cause Mortality and Infection-related Mortality During 9 Months After Initiation of Tuberculosis Treatment Among Patients With Hypertension and Calcium Channel Blocker Use (Per-protocol Analysis)

| Characteristic | All-cause mortality | Infection-related mortality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR | 95%CI | P value | Adjusted HRb | 95%CI | P value | Unadjusted HR | 95%CI | P value | Adjusted HRb | 95%CI | P value | |

| All CCB | ||||||||||||

| CCB use | .68 | .47–.99 | .04 | .62 | .34–1.13 | .10 | .82 | .49–1.37 | .44 | .70 | .29–1.69 | .44 |

| Sex | 1.24 | .90–1.72 | .19 | 1.37 | .84–2.25 | .20 | 1.30 | .80–2.09 | .29 | 1.21 | .57–2.60 | .61 |

| Prior TB | 1.35 | .65–2.80 | .43 | 1.45 | .69–3.01 | .32 | 2.24 | .87–5.77 | .13 | 2.33 | .91–6.16 | .08 |

| DHP-CCB | ||||||||||||

| DHP-CCB use | .66 | .45–.98 | .03 | .67 | .37–1.21 | .19 | .78 | .46–1.34 | .38 | .76 | .31–1.85 | .55 |

| Sex | 1.24 | .89–1.73 | .19 | 1.39 | .85–2.28 | .19 | 1.30 | .80–2.09 | .28 | 1.22 | .57–2.63 | .59 |

| Prior TB | 1.35 | .65–2.80 | .43 | 1.43 | .69–2.97 | .34 | 2.24 | .87–5.77 | .13 | 2.35 | .90–6.12 | .08 |

N = 2894.

Abbreviations: CCB, calcium channel blocker; CI, confidence interval; DHP, dihydropyridine; HR, hazard ratio; TB, tuberculosis.

aWe excluded 97 patients from this analysis, as they had a follow-up time of less than 30 days since TB diagnosis.

bAdjusted for all variables included in the table. The variables were selected because they were significantly different between CCB users and nonusers in Table 6.

Stratification of Hypertensive Patients Based on Non–DHP-CCB Use

There were 20 patients (1.6%) that satisfied the criteria for non–DHP-CCB use. There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality between non–DHP-CCB use (4/15 patients) and CCB nonuse (162/704 patients; 26.67% vs 20.79%, respectively; P = .852). Similarly, no significant difference was found in infection-related mortality between the non–DHP-CCB group (3/15 patients) and the non-CCB group (72/704 patients; 20.0% vs 10.80%, respectively; P = .314).

Stratification of Hypertensive Patients Based on DHP-CCB Use

As shown in Table 6, there were more male patients (P = .03) and patients with a prior history of TB (P < .01) in the group receiving DHP-CCB compared to the group not receiving CCB. Patients receiving DHP-CCB had significantly lower mortality (29/187, 15.2%) compared to those not treated with CCB (162/701; 23.1%; P = .02; Table 7). A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and a log-rank test show that patients treated with DHP-CCB had longer survival compared to patients not receiving DHP-CCB (Figure 3A; P = .041), while multivariate Cox regression showed no significant relationship to all-cause mortality (Table 8). An intention-to-treat analysis revealed no significant difference in time to all-cause mortality between DHP-CCB users and CCB nonusers (Supplementary Table 2). There were no significant differences in 9-month infection-related mortality (Figure 3B) or sputum culture conversion rates at 2 and 6 months of TB treatment among patients with and without DHP-CCB use when a chi-square test (Table 7) and univariable and multivariable logistic regression were used (Supplementary Table 1B).

Table 6.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants With Hypertension, Stratified by Calcium Channel Blocker Use (Per Protocol)

| Sl. No | Study characteristics | Measure | Total, N = 959 | All CCB use | DHP-CCB use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without CCB use, n = 745 | With CCB use, n = 210 | P value | Without CCB use, n = 745 | With DHP-CCB use, n = 195 | P value | ||||

| 1. | Age, y | Median (IQR) | 75.1 (66.4 –82.0) | 75.1 (66.2–82.2) | 75.0 (67.0–80.8) | .36 | 75.1 (66.2–82.2) | 74.7 (66.7– 80.6) | .57 |

| 2. | Male sex | n (%) | 71.94% | 73.4% | 66.7% | .05 | 547 (73.4%) | 128 (65.6%) | .03 |

| 3. | Smoking | n (%) | 332/795 (41.8%) | 262/618 (42.4%) | 70/177 (39.6%) | .49 | 262 (42.4%) | 64 (38.6%) | .37 |

| 4. | Alcoholism | n (%) | 20 (2.1%) | 16 (2.2%) | 4 (1.9%) | .83 | 16 (2.2%) | 3 (1.5%) | .59 |

| 5. | Initial AFB smear | n (%) | 348 (36.7%) | 271 (36.6%) | 77 (36.8%) | .95 | 271 (36.6%) | 72 (37.1%) | .90 |

| 6. | Prior TB | n (%) | 32 (6.8%) | 19 (5.2%) | 13 (13.3%) | <.01 | 19 (5.2%) | 12 (13.0%) | <.01 |

| 7. | Cavitary disease | n (%) | 98 (10.3%) | 75 (10.1%) | 23 (11.0%) | .71 | 75 (10.1%) | 22 (11.3%) | .62 |

| 8. | DM | n (%) | 287 (30.1%) | 220 (29.6%) | 67 (31.9%) | .52 | 220 (29.6%) | 62 (31.8%) | .55 |

| 9. | Cancer | n (%) | 194 (20.4%) | 153 (20.6%) | 41 (19.5%) | .73 | 153 (20.6%) | 40 (20.5%) | .98 |

| 10. | CKD stage ≥ 4 | n (%) | 85 (9.4%) | 65 (9.1%) | 20 (10.5%) | .58 | 65 (9.1%) | 19 (10.8%) | .51 |

| 11. | Cardiovascular disease | n (%) | 213(22.2%) | 166 (22.2%) | 47 (22.3%) | .98 | 166 (22.2%) | 41 (20.9%) | .63 |

| CAD | … | 181 (18.9%) | 142 (19.0%) | 39 (18.5%) | .87 | 142 (19.0%) | 34 (17.4%) | .61 | |

| AMI | … | 54 (5.6%) | 44 (5.9%) | 10 (4.7%) | .53 | 44 (5.9%) | 9 (4.6%) | .48 | |

| CHF | … | 71 (7.4%) | 59 (7.9%) | 12 (5.7%) | .28 | 59 (7.9%) | 10 (5.1%) | .18 | |

| 12. | Asthma | n (%) | 49 (5.1%) | 37 (5.0%) | 12 (5.7%) | .67 | 37 (5.0%) | 9 (4.6%) | .84 |

| 13. | COPD | n (%) | 214 (22.4%) | 157 (21.1%) | 57 (27.1%) | .06 | 157 (21.1%) | 53 (27.2%) | .07 |

| 14. | Bronchiectasis | n (%) | 39 (4.1%) | 26 (3.5%) | 13 (6.2%) | .08 | 26 (3.5%) | 12 (6.1%) | .09 |

| 15. | Pneumoconiosis | n (%) | 13 (1.4%) | 10 (1.3%) | 3 (1.4%) | .93 | 10 (1.3%) | 2 (1.0%) | .73 |

| 16. | Autoimmune disease | n (%) | 44 (4.6%) | 31 (4.1%) | 13 (6.2%) | .22 | 31 (4.1%) | 13 (6.7%) | .14 |

| 17. | Liver cirrhosis | n (%) | 17 (1.8%) | 14 (1.8%) | 3 (1.5%) | .66 | 14 (1.8%) | 3 (1.5%) | .75 |

| 18. | History of transplant | n (%) | 16 (1.7%) | 12 (1.6%) | 4 (1.9%) | .77 | 12 (1.6%) | 4 (2.0%) | .67 |

| 19. | HIV | n (%) | 9 (.9%) | 7 (.9%) | 2 (1.0%) | .99 | 7 (.9%) | 2 (1.0%) | .91 |

| 20. | CCI | Mean (SD) | 5.2 (2.3) | 5.2 (2.3) | 5.4 (2.1) | .25 | 5.2 (2.3) | 5.4 (2.1) | .16 |

N = 2894.

Abbreviations: AFB, acid-fast bacilli; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHP, dihydropyridine; DM, diabetes mellitus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; TB, tuberculosis.

aWe excluded 97 patients from this analysis, as they had a follow-up time of less than 30 days since TB diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Survival analysis during 9 months of follow-up after TB treatment initiation in patients with hypertension based on use or nonuse of DHP-CCB. A. All-cause mortality. B. Infection-related mortality. Abbreviations: CCB, calcium channel blocker; DHP, dihydropyridine; TB, tuberculosis.

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis performed by including patients who died in the first month of TB treatment also showed a lower hazard of all-cause mortality with any CCB use (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, .47–.99) and DHP-CCB use (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, .33–.70). However, multivariable Cox regression revealed no significant association with all-cause mortality, and infection-related mortality in patients with hypertension was not found to be associated with CCB use (Supplementary Table 3A). A sensitivity analysis conducted by excluding participants who did not receive a required dose of CCB did not show any significant association with all-cause mortality or infection-related mortality (Supplementary Table 3B).

Discussion

In our cohort, 821/1516 patients (54.2%) aged more than 65 years had hypertension. This proportion is considerably higher than in a similar population in Japan reported previously by Umeki (35%) [22]. Notably, most patients with hypertension at the time of TB diagnosis do not report a history of hypertension [23]. Therefore, our findings would suggest that hypertension screening is important, especially in elderly patients receiving a new TB diagnosis.

Our major finding is that hypertensive patients had a greater adjusted hazard of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.23–1.99) and, interestingly, infection-related mortality (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.34–2.61) during the first 9 months of TB treatment initiation. In a prior study by Chiang et al [25], hypertension was not an independent predictor of negative outcomes when adjusted for other factors, although hypertension has been associated with an increase in the composite outcome of treatment failure, default, and death [24]. In Chiang et al’s study [25], death constituted a small proportion (17.3%) of negative outcomes, while a much greater proportion was contributed by treatment default (78.2%). Our study is the first to show increased short-term mortality attributable to hypertension in patients receiving TB treatment. We found that hypertension was an independent predictor of 9-month all-cause and infection-related mortality when adjusting for confounders. As age is indirectly adjusted through the CCI, this finding raises the possibility that there could be a direct link connecting hypertension and poor TB outcomes, apart from the age-related comorbidities frequently observed in patients with hypertension.

Hypertension has long been recognized as an inflammatory condition [26]. Increased levels of C-reactive protein, TNF-α, and T-helper cells were observed in patients with hypertension, as compared to normotensive patients [27, 28]. Animal models have shown the association of decreased levels of renin and angiotensin with decreased levels of peripheral T-lymphocytes and interleukins, like IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [29]. Hypertension is also associated with increased oxidative stress [30], and angiotensin-II is known to increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase [31]. The relationship between NADPH oxidase and ROS and sepsis-induced mortality has been shown in a mouse model by Kong et al [32]. The higher risk of infection-related mortality seen in patients with hypertension in our study could be due to the increased levels of interleukins, NADPH oxidase, and ROS in these patients [33].

While a number of infections, such as Aggregatibacter, Prevotella [34], Helicobacter pylori [35], human immunodeficiency virus [36–38], herpes simplex virus–2 [39], cytomegalovirus [40], and Toxoplasmosis gondii [41], have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of hypertension, no prior studies have assessed the outcomes of these infections in patients with hypertension. In our study, the proportions of patients with sputum AFB smear positivity and cavitary disease at diagnosis were higher in the normotensive group compared to the hypertensive group, suggesting a higher baseline bacillary burden in the lungs of patients in the former group. However, at 2 and 6 months after TB treatment initiation, there were no statistically significant differences, by chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression, in rates of sputum AFB smear positivity between the 2 groups. This suggests that hypertension could interfere with mycobacterial clearance.

Blockade of the L-type and R-type voltage-gated calcium channels in macrophages, which are responsible for regulating phagocytic function, has been shown to increase intracellular calcium concentrations [12]. This, in turn, has been demonstrated to increase the killing of intracellular mycobacteria in mouse models [12]. Verapamil, a non–DHP-CCB which blocks mycobacterial efflux pumps, has been shown to reduce the TB treatment time and decrease the minimum inhibitory concentration of bedaquiline and clofazimine in preclinical studies [42]. In addition, verapamil inhibits host cell efflux pumps, and has attracted attention as a potential host-directed therapy [14, 15]. In our study, only 20 patients with hypertension satisfied the criteria for exposure to verapamil and other non–DHP-CCB, with no significant difference in 9-month all-cause mortality during TB treatment (P = .852). A clinical trial with a larger sample is required to further evaluate the potential adjunctive activity of non–DHP-CCB in TB treatment. There have been no previous studies performed using DHP-CCB as an adjunctive therapy. Our study revealed that DHP-CCB use in hypertensive patients surviving more than 30 days following the initiation of TB treatment was associated with a significant decrease in 9-month all-cause mortality. This finding could not be explained by differences in baseline characteristics between patients receiving and not receiving DHP-CCB. Interestingly, there was a non–statistically significant trend towards a lower sputum AFB positivity rate at 2 months in patients who used DHP-CCB (3.1%), compared to those who did not (6.6%), but no statistical difference in the culture conversion rates at 2 and 6 months.

An important limitation of our study is that sputum smear microscopy and microbiological culture results at 2 and 6 months post-TB treatment were not available for nearly 25% of the patients in our cohort. There was a drop-out rate of 9%, which could be a source of bias in our study. Inconsistencies in the reporting of causes of death prevented us from accurately assessing TB-specific mortality. The levels of control of hypertension and other anti-hypertensive drugs were not obtainable from the available data, and could be confounding factors in study. The extraction of blood pressure data as a continuous variable in future studies could permit a dose-response evaluation between these parameters and mortality. However, the large sample size of our cohort enabled the analysis of individual risk factors and their impacts on short-term mortality. Additionally, enrollment of all the study participants from a single center helped to decrease heterogeneity in the clinical management of these patients.

Our study shows that hypertension is an independent predictor of all-cause and infection-related mortality during the first 9 months of TB treatment initiation, after adjusting for confounders. Microbiological outcomes were not significantly different between the hypertensive and normotensive groups, despite a higher incidence of smear-positive and cavitary disease in the normotensive group at baseline. The use of DHP-CCB was associated with improved 9-month all-cause mortality in hypertensive patients with TB. Our study highlights the importance of screening for hypertension in TB, especially in elderly patients receiving a new diagnosis of TB. Prospective studies are warranted to determine the potential beneficial effects of controlling hypertension, and specifically of using CCB, on TB treatment outcomes.

Notes

Author contributions. V. C., A. G., and P. C. K. conceived the study. J.-Y. W. collected the data. V. C. performed the analysis. A. G. and J. E. G. guided in the analysis and the methods. V. C. and A. G. drafted the manuscript. J. E. G., J.-Y. W., and P. C. K. corrected the draft. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/ National Institutes of Health (grant numbers UH3AI122309 and K24AI143447 to P. C. K.) and the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (grant number MOHW-105-CDC-C-114-000103 to J.-Y. W).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2019. World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016; 134:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seegert AB, Rudolf F, Wejse C, Neupane D. Tuberculosis and hypertension—a systematic review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 56:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chung W-S, Lin C-L, Hung C-T, et al. Tuberculosis increases the subsequent risk of acute coronary syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2014. Available at: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2014/00000018/00000001/art00016#. Accessed 24 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. Huaman MA, Kryscio RJ, Fichtenbaum CJ, et al. Tuberculosis and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a propensity score-matched analysis. Epidemiol Infect 2017; 145:1363–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salindri AD, Wang J-Y, Lin H-H, Magee MJ. Post-tuberculosis incidence of diabetes, myocardial infarction, and stroke: retrospective cohort analysis of patients formerly treated for tuberculosis in Taiwan, 2002–2013. Int J Infect Dis 2019; 84:127–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krishnan SM, Sobey CG, Latz E, Mansell A, Drummond GR. IL-1β and IL-18: inflammatory markers or mediators of hypertension? Br J Pharmacol 2014; 171:5589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caillon A, Schiffrin EL. Role of inflammation and immunity in hypertension: recent epidemiological, laboratory, and clinical evidence. Curr Hypertens Rep 2016; 18. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11906-016-0628-7. Accessed 24 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kolloli A, Subbian S. Host-directed therapeutic strategies for tuberculosis. Front Med 2017; 4. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2017.00171/full. Accessed 24 April 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamada G, Shijubo N, Shigehara K, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Abe S. Increased levels of circulating interleukin-18 in patients with advanced tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:1786–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sahiratmadja E, Alisjahbana B, de Boer T, et al. Dynamic changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles and gamma interferon receptor signaling integrity correlate with tuberculosis disease activity and response to curative treatment. Infect Immun 2007; 75:820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gupta S, Salam N, Srivastava V, et al. Voltage gated calcium channels negatively regulate protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS One 2009; 4:e5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Machado D, Pires D, Perdigão J, et al. Ion channel blockers as antimicrobial agents, efflux inhibitors, and enhancers of macrophage killing activity against drug resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS One 2016; 11:e0149326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Srikrishna G, Gupta S, Dooley KE, Bishai WR. Can the addition of verapamil to bedaquiline-containing regimens improve tuberculosis treatment outcomes? A novel approach to optimizing TB treatment. Future Microbiol 2015; 10:1257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adams KN, Szumowski JD, Ramakrishnan L. Verapamil, and its metabolite norverapamil, inhibit macrophage-induced, bacterial efflux pump-mediated tolerance to multiple anti-tubercular drugs. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:456–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Louw GE, Warren RM, Gey van Pittius NC, et al. Rifampicin reduces susceptibility to ofloxacin in rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis through efflux. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184:269–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chien JY, Chen YT, Wu SG, Lee JJ, Wang JY, Yu CJ. Treatment outcome of patients with isoniazid mono-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nahid P, Dorman SE, Alipanah N, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:e147–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chobanian Aram V, Bakris George L, Black Henry R, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jennings Garry LR, Touyz Rhian M. Hypertension guidelines. Hypertension 2013; 62:660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Umeki S. Clinical features of pulmonary tuberculosis in young and elderly men. Jpn J Med 1989; 28:341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whitehouse ER, Perrin N, Levitt N, Hill M, Farley JE. Cardiovascular risk prevalence in South Africans with drug-resistant tuberculosis: a cross-sectional study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2019; 23:587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes. WHO/CDS/TB/2003.313. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chiang YC, Lin YM, Lee JA, Lee CN, Chen HY. Tobacco consumption is a reversible risk factor associated with reduced successful treatment outcomes of anti-tuberculosis therapy. Int J Infect Dis 2012; 16:e130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McMaster WG, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertensive end-organ damage. Circ Res 2015; 116:1022–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Skoumas J, Stefanadis C. Association between prehypertension status and inflammatory markers related to atherosclerotic disease: the ATTICA Study. Am J Hypertens 2004; 17:568–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ji Q, Cheng G, Ma N, et al. Circulating Th1, Th2, and Th17 levels in hypertensive patients. Dis Markers 2017; 2017:7146290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xiao L, Kirabo A, Wu J, et al. Renal denervation prevents immune cell activation and renal inflammation in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res 2015; 117:547–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crowley SD. The cooperative roles of inflammation and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 20:102–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, et al. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 2007; 204:2449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kong X, Thimmulappa R, Kombairaju P, Biswal S. NADPH oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species mediate amplified TLR4 signaling and sepsis-induced mortality in Nrf2-deficient mice. J Immunol 2010; 185:569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miyoshi T, Yamashita K, Arai T, Yamamoto K, Mizugishi K, Uchiyama T. The role of endothelial interleukin-8/NADPH oxidase 1 axis in sepsis. Immunology 2010; 131:331–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aoyama N, Suzuki JI, Kumagai H, et al. Specific periodontopathic bacterial infection affects hypertension in male cardiovascular disease patients. Heart Vessels 2018; 33:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wan Z, Hu L, Hu M, Lei X, Huang Y, Lv Y. Helicobacter pylori infection and prevalence of high blood pressure among Chinese adults. J Hum Hypertens 2018; 32:158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu Y, Chen X, Wijayabahu A, et al. Cumulative HIV viremia copy-years and hypertension in people living with HIV. Curr HIV Res 2020; 18:143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Korem M, Wallach T, Bursztyn M, Maayan S, Olshtain-Pops K. High prevalence of hypertension in Ethiopian and non-Ethiopian HIV-infected adults. Int J Hypertens 2018; 2018:8637101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gazzaruso C, Bruno R, Garzaniti A, et al. Hypertension among HIV patients: prevalence and relationships to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens 2003; 21:1377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun Y, Pei W, Wu Y, Jing Z, Zhang J, Wang G. Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection is a risk factor for hypertension. Hypertens Res 2004; 27:541–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Z, Peng X, Li M, et al. Is human cytomegalovirus infection associated with essential hypertension? A meta-analysis of 11 878 participants. J Med Virol 2016; 88:852–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Han Y, Nie L, Ye X, et al. The association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and hypertensive disorders in T2DM patients: a case-control study in the Han Chinese population. Parasitol Res 2018; 117:689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gupta S, Tyagi S, Almeida DV, Maiga MC, Ammerman NC, Bishai WR. Acceleration of tuberculosis treatment by adjunctive therapy with verapamil as an efflux inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:600–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]