Abstract

Background

Although most cases of varicella or zoster are self-limited, patients with certain immune deficiencies may develop severe or life-threatening disease.

Methods

We studied a patient with varicella-zoster virus (VZV) central nervous system (CNS) vasculopathy and as part of the evaluation, tested his plasma for antibodies to cytokines. We reviewed the literature for cases of varicella or zoster associated with primary and acquired immunodeficiencies.

Results

We found that a patient with VZV CNS vasculopathy had antibody that neutralized interferon (IFN)-α but not IFN-γ. The patient’s plasma blocked phosphorylation in response to stimulation with IFN-α in healthy control peripheral blood mononuclear cells. In addition to acquired immunodeficiencies like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or autoantibodies to IFN, variants in specific genes have been associated with severe varicella and/or zoster. Although these genes encode proteins with very different activities, many affect IFN signaling pathways, either those that sense double-stranded RNA or cytoplasmic DNA that trigger IFN production, or those involved in activation of IFN stimulated genes in response to binding of IFN with its receptor.

Conclusions

Immune deficiencies highlight the critical role of IFN in control of VZV infections and suggest new approaches for treatment of VZV infection in patients with certain immune deficiencies.

Keywords: varicella-zoster, immunodeficiency, zoster, chickenpox, interferon

Although numerous primary and acquired immunodeficiencies have been identified that predispose to severe varicella-zoster virus infections, most of these reflect either global defects in cellular immunity or impairment in the interferon signaling pathway.

Although most cases of varicella are mild, patients with certain immunodeficiencies develop severe or life-threatening disease. Similarly, many persons develop at most a single case of zoster in their lifetime without complications; however, some with immunodeficiencies have multiple cases of zoster with severe complications requiring hospitalization. Both varicella and zoster can be complicated by skin and soft tissue infections, encephalitis, pneumonitis, or hepatitis. Highly immunocompromised children may also develop disseminated disease after receiving the live attenuated varicella vaccine. Here, we review the literature and report that variants in several genes critical for interferon (IFN) signaling are responsible for primary immunodeficiencies involving patients with severe varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections. We also review acquired immunodeficiencies linked with serious VZV infection.

PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCIES ASSOCIATED WITH SEVERE VZV DISEASE

Severe VZV infections have been associated with disorders of T and natural killer (NK) cells, which are important for killing virus-infected cells. Patients with severe combined immunodeficiency due to mutations in ADA, RAG1, RAG2, RMRP, PNP, MSN, CORO1A, and IL7R have been reported with disseminated varicella associated with wild-type virus or the varicella vaccine (Table 1, and references in Supplementary Data). Some patients with common variable immunodeficiency have impaired lymphocyte proliferation to mitogens and pathogens and may develop severe herpes zoster [1]. Patients with NK cell deficiencies, including those due to mutations in FCRF3A, GATA2, MCM4, GINS1, and RTEL1 [2] (and other references in Supplementary Data) may have severe or fatal complications associated with varicella. Invariant NKT (iNKT) cells recognize lipid antigens presented by CD1d and are important for T-cell and dendritic cell activation and production of IFN-γ and other cytokines. Patients with low numbers of iNKT cells have had disseminated varicella after receiving the varicella vaccine or have had recurrent zoster [3]; 1 patient had reduced levels of CD1d [4]. Severe varicella has been seen in patients with idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia [5] and with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome [6] who have impaired NK cell function associated with impaired immune synapse formation. Patients with ataxia telangiectasia have reduced lymphocyte proliferation and may also have severe varicella [7].

Table 1.

Genes Associated With Severe or Recurrent Varicella or Zoster

| Gene/Protein | Syndrome | VZV Disease | Other Infections | Other Findings | Immunologic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADA, RAG1, RAG2, PNP, RMRP, MSN, CORO1A, IL-17 | Severe combined immunodeficiency | Severe varicella | Severe EBV, CMV, RSV, HSV, rotavirus, influenza, PIV, PJP, mucocutaneous candidiasis | Absent thymus, tonsils, adenoids | Low T, B, NK cells, low Ig, anergy |

| FCGR3A, GATA2, MCM4, GINS1, RTEL1 | NK cell deficiencies | Severe varicella | Severe CMV, HSV, EBV, HPV | Increased myeloid cancers with GATA2 | Low NK cells, impaired NK cell cytotoxicity |

| Unknown | iNKT cell deficiency | Disseminated varicella vaccine virus, recurrent zoster | Recurrent respiratory infections, RSV pneumonia | Low iNKT or impaired iNKT function; low NKT cells in one patient | |

| WAS | Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome | Severe varicella | Sinopulmonary infections, PJP, molluscum, CMV | Thrombocytopenia, eczema, autoimmune disease, B cell lymphoma | Low T cells, low IgG, elevated IgE and IgA |

| ATM | Ataxia telangiectasia | Severe varicella | Sinopulmonary infections, HPV, Candida esophagitis | Telangiectasias, ataxia, dysphagia, interstitial lung disease, lymphoma, leukemia | Low or absent IgA, low IgG subclasses, lymphopenia, oligoclonal gammopathy, impaired antibodies to polysaccharide containing antigens |

| CTPS1 | Cytidine5’ triphosphate synthase I deficiency | Severe varicella | EBV, CMV, adenovirus, norovirus, encapsulated bacteria | EBV lymphoma | Some with lymphopenia, low IgG2, reduced proliferation of activated T and B cells after antigen receptor-mediated activation |

| PIK3CD | Activated PI3K-δ syndrome 1 | Severe varicella, recurrent zoster | Recurrent sinopulmonary infections, CMV viremia and lymphadenitis, EBV viremia and lymphoma, severe HPV, HSV, molluscum, ADV | Bronchiectasis, EBV lymphoma | Decreased T and B cells, low IgG and IgA, high IgM |

| PIK3R1 | Activated PI3K-δ syndrome 2 | Severe varicella | Recurrent sinopulmonary infections, CMV viremia and lymphadenitis, EBV viremia and lymphoma, measles encephalitis | Bronchiectasis, EBV lymphoma | Decreased T and B cells, low IgG and IgA, high IgM |

| DOCK2 | Autosomal recessive DOCK2 deficiency | Severe varicella | CMV, HHV6, RSV, adenovirus, mumps, parainfluenza, Mycobacterium avium, Klebsiella | Thrombocytopenia, hepatomegaly, colitis | Reduced T, NKT cells, reduced T-cell activation with PHA, reduced antibody production to T-cell–dependent antigens |

| DOCK8 | DOCK8 deficiency | Severe varicella | Recurrent sinopulmonary infections, severe HPV, HSV, molluscum, mucocutaneous candidiasis | Atopic dermatitis, hepatitis, squamous cell carcinoma, T and B cell lymphoma | Decreased T, B, NK cells, reduced NK cell and CD8 cell function, low IgM, high IgE, eosinophilia |

| MAGT1 | XMEN | Severe, varicella, recurrent zoster | EBV viremia, sinopulmonary infections | B cell lymphoma | Low CD4 cells, increased B cells, low IgG |

| STK4 | MST1 deficiency | Recurrent zoster | EBV lymphoproliferative disease, severe HPV, molluscum contagiosum, and Candida | B cell lymphoma, autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Low CD4 cells, naive T cells, and B cells |

| CXCR4 | WHIM syndrome | Severe varicella | Severe HPV, sinopulmonary infections | Squamous cell carcinoma | Low B cells, neutropenia, hypogammaglobulinemia |

| CD70 | CD70 deficiency | Varicella pneumonia | EBV lymphoproliferative disease, sinopulmonary infections | B cell lymphoma | Hypogammaglobulinemia |

| STIM1 | Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) deficiency | Severe varicella | CMV, EBV, KSHV, enterovirus, bacterial sepsis | Lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, hypotonia, iris hypoplasia, defective dental enamel | Usually normal T-cell subsets and variable IgG, impaired T-cell stimulation to PHA and to anti-CD3 antibody |

| IFNGR1 | Autosomal recessive and dominant negative IFN-γ receptor 1 deficiencies | Severe varicella | Disseminated mycobacteria and Salmonella, severe CMV, RSV, PIV, KSHV | Reduced or absent pSTAT1 in response to IFN-γ | |

| STAT1 | Autosomal dominant STAT1 gain-of-function (GOF) disease | Severe varicella, zoster at an early age, recurrent zoster | Mucocutaneous and disseminated fungi, sinopulmonary infections, mycobacterial infections, HSV, CMV, EBV, HPV, molluscum | Inflammatory bowel disease, hypothyroidism, autoimmune cytopenias, squamous cell carcinoma | Lymphopenia, low Ig, reduced NK cell function |

| STAT1 | Autosomal recessive STAT1 loss of function (LOF) deficiency | Severe varicella | CMV, HSV, Salmonella, BCG | Not reported | Impaired activation of ISGs in response to IFN-γ and IFN-λ |

| STAT3 | Autosomal dominant hyperimmunoglobulin E (Job’s) syndrome | Zoster at an early age, recurrent zoster | Staphylococcal and Candida “cold” abscesses, sinopulmonary infections, mucocutaneous candidiasis, Cryptococcus and Coccidioides meningitis, histoplasmosis | Dermatitis, characteristic facies, retention of primary teeth, scoliosis, bone fractures, non-Hodgkin lymphoma | High IgE, eosinophilia |

| STAT5B | STAT5B deficiency | Severe varicella, recurrent zoster | Recurrent respiratory and skin infections, chronic diarrhea, Pneumocystis jirovecii | Growth retardation, eczema, lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis, autoimmunity, EBV lymphoma | Reduced T cells |

| TLR3 | TLR3 deficiency | VZV encephalitis, recurrent zoster ophthalmicus | HSV encephalitis | none | Impaired fibroblast or neuron IFN response to poly I:C |

| POLR3A,C,E,F | RNA polymerase 3 mutations | Severe varicella, VZV encephalitis | none | none | Impaired IFN response to poly A:T |

Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; BCG, bacille Calmette-Guerin; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; Ig, immunoglobulin; ISG, interferon stimulated gene; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NK, natural killer; PIV, parainfluenza virus; PJP, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Mutations in CTPS1 result in impaired proliferation of activated T and B cells after antigen receptor-mediated activation; many of these patients have had severe varicella [8]. Gain-of function mutations in PIK3CD and PIK3R1 can result in hyperactivation of Akt with increased senescent and reduced memory CD8 cells with severe varicella or recurrent zoster [9]. DOCK2 deficiency has been associated with fatal varicella and dissemination of varicella vaccine virus in the context of low numbers of T cells and reduced T-cell activation with mitogens [10]. Mutations in DOCK8 impair lymphocyte migration in the skin and can result in severe varicella, recurrent zoster, and disseminated varicella vaccine virus [11]. MAGT1 mutations result in reduced CD4 cells and have been associated with severe varicella and recurrent zoster [12]. STK4 mutations result in low CD4 T cells, and 1 patient had recurrent zoster [13]. Patients with CXCR4 mutations usually have chronic warts and severe varicella has been reported [14]. CD70 mutations are associated with EBV lymphoma; one patient had varicella pneumonia [15]. STIM1 loss-of-function mutations have been associated with severe varicella and reduced T-cell responses to stimulation with anti-CD3 and PMA/ionomycin [16]. Mutations in IFNGR1 impair the response to IFN-γ and have also been associated with severe varicella [17].

Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STATs) are adapter proteins important for IFN signaling. The largest review of patients with STAT1 gain-of-function (GOF) mutations reported that 7% (18/274) of patients had severe varicella with VZV pneumonitis or cutaneous bacterial superinfections, and 12% (33/274 patients) had zoster during childhood that recurred in 58% of the cases [18]. Patients with STAT1 deficiency caused by loss-of-function (LOF) mutations may have impaired responses to IFN-γ and INF-λ, which has also been associated with severe varicella [19]. Patients with autosomal dominant hyperimmunoglobulin E (IgE) (Job’s) syndrome with dominant negative STAT3 mutations have a 6- to 20-fold increased rate of zoster compared with the general population when matched for age by decade of patients and controls [20]. In this study the mean age of the patients was 27 years, 33% (19/58) had zoster, and 26% (5/19) of the patients with zoster had recurrent disease. Patients seropositive for VZV with autosomal dominant negative STAT3 syndrome had reduced numbers of memory CD4 T cells that responded to VZV antigens. Patients with STAT5b deficiency have impaired responses to interleukin 2 (IL-2), and some have had severe hemorrhagic varicella and recurrent zoster [21].

Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) senses double-stranded RNA in response to virus infection and results in increased production of IFN-α, -β, or -λ. Mutations in TLR3 and its downstream signaling molecules UNC93B1, TRIF, TRAF3, TBK1, and IRF3 have been associated with childhood herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis [22]. A patient with VZV meningoencephalitis had a heterozygous mutation in TLR3, predicted to be damaging to the protein [23]. A patient with recurrent zoster ophthalmicus was found to have a heterozygous TLR3 mutation; stimulation of patient fibroblasts with poly I:C or poly A:U resulted in impaired production of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IL-6 [24].

RNA polymerase 3 transcribes DNA in the nucleus of cells to produce tRNAs, 5S rRNA, and microRNAs; in the cytoplasm RNA polymerase 3 transcribes AT-rich DNAs to RNA adding a 5′ triphosphate group, which results in detection of the RNA by RIG-I and triggering production of IFN-α and β [25]. VZV is the most AT-rich human herpesvirus, so its viral DNA is likely sensed by RNA polymerase 3 in the cytoplasm. Four children with VZV central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, cerebellitis, or pneumonitis had heterozygous mutations in POLR3A or POLR3C, which encode 2 RNA polymerase subunits [26]. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the patients were impaired for production of IFN-α in response to VZV DNA or poly dA:dT. Identical twins with recurrent CNS vasculitis were reported to have heterozygous mutations in POLR3F resulting in reduced IFN-β and TNF-α in response to poly dA:dT and increased VZV replication in PBMCs [27]. Two elderly patients with VZV meningoencephalitis with heterozygous mutations in POLR3A or POLR3E had impaired IFN-β responses to poly dA:dT and increased VZV replication in PBMCs [28]. These abnormal findings were not observed either in patients with VZV CNS disease without mutations in RNA polymerase 3 or in patients with HSV encephalitis. Taken together, these results emphasize the importance of sensing AT-rich sequences in VZV DNA for triggering an IFN response by RNA polymerase 3.

ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCIES ASSOCIATED WITH SEVERE VZV

Children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have an increased risk for severe varicella. A prospective longitudinal study of children with HIV found that only 3% (1/30) of children had severe varicella requiring hospitalization, but that 27% (8/30) with varicella after age 1 developed zoster in childhood [29]. Zoster occurred a mean of 1.9 years after varicella.

One study evaluating HIV patients during the era of antiretroviral therapy (ART) showed that the incidence of zoster was 2.5-fold higher in HIV patients compared with the general population (9.3 vs 3.5 cases per 1000 person-years) [30]. Complications of zoster were observed in 28% of these HIV patients, including 12% with postherpetic neuralgia, 11% with disseminated zoster, 6% with bacterial superinfection, and 6% with ophthalmic zoster. Increased rates of zoster were associated with lower CD4 counts. An increased frequency of zoster was associated with initiating ART [31], presumably due to immune reconstitution with rising CD8 T-cell counts. Patients with HIV can develop chronic mucocutaneous disease due to VZV [32]; in some cases, this presents as verrucous zoster with wart-like lesions often associated with acyclovir-resistant VZV.

VZV CNS VASCULITIS ASSOCIATED WITH ANTI-CYTOKINE ANTIBODIES

An acquired immunodeficiency manifested by anti-cytokine autoantibodies and disseminated nontuberculous mycobacteria, as well as other opportunistic infections, was reported by Browne et al [33]. In the patient group with opportunistic infections, 96% had autoantibodies to IFN-γ, 22% (10/45) had zoster, and 7% (3/45) had disseminated zoster. In a study of patients with zoster with or without postherpetic neuralgia or with pain syndromes not due to VZV, 7% (6/83) of patients with zoster and postherpetic neuralgia had markedly increased levels of antibodies to IFN-α, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, or IL-6 [34]. Neutralizing or partially neutralizing autoantibodies to IFN-α, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, and IL-6 were found in 1 patient each. Patients with zoster without postherpetic neuralgia or other pain syndromes had no or low levels of antibodies to these cytokines. These findings emphasize the importance of cytokines, particularly IFN, in controlling the severity of zoster.

We evaluated a 64-year-old previously healthy man who developed acute incomplete Brown-Sequard syndrome (ipsilateral hemiplegia and contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation due to a spinal cord lesion) at the T3 level, following a spinal cord infarct documented by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (reported previously as an abstract [35]). Physical examination showed 3–4/5 motor strength in the right leg with hyperesthesia and dense sensory loss in the left leg. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed 188 cells/mm3 (normal <1 cell) with B-lymphocyte predominance, absence of red blood cells, protein 242 mg/dL (normal, 15–45 mg/dL), glucose 24 mg/dl (normal 40–70 mg/dL), oligoclonal bands, myelin basic protein, and microbiologic studies were negative (VZV studies were not performed). He was treated with steroids and his right leg strength improved such that he could ambulate using a walker. One week after initiating therapy; however, his weakness progressed to 1/5 strength in the proximal right leg and 2/5 in the proximal left leg. Two days later he had 0/5 strength throughout both legs with full strength in his arms, and he developed encephalopathy, left ptosis, and bilateral ophthalmoplegia. Repeat MRI showed that in addition to the previous spinal infarct, there were new patchy T2 hyperintensities throughout the spinal cord (Figure 1A) with enhancement of the nerve roots. MRI of the brain showed enhancement of the ependyma of the lateral ventricles and meninges and a small cortical bleed in the right posterior parietal lobe. A lumbar puncture showed 661 cells/mm3 (predominantly lymphocytes), protein 183 mg/dL, glucose 21 mg/dL. The CSF had detectable low level EBV (<52 U/mL) and VZV (<278 copies/mL) DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR); VZV IgM in the CSF was positive. He was diagnosed with VZV CNS vasculitis and treated with ganciclovir for 1 week followed by acyclovir for 1 month and methylprednisolone followed by a prednisone taper. Additional clinical laboratory results are in Supplementary data.

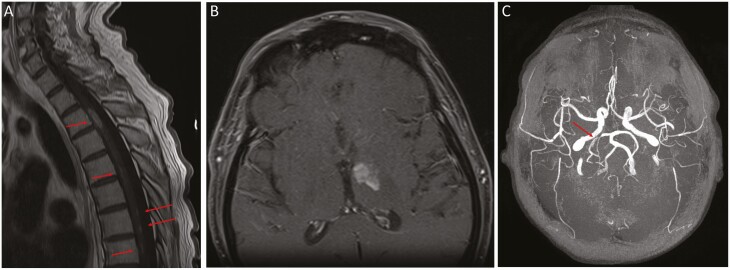

Figure 1.

MRI and MRA findings in a man with VZV CNS vasculitis and neutralizing anti-interferon (IFN)-α antibodies. A, MRI of the spine shows ovoid lesions in T3–T4 (long arrows) and patchy lesions in T5–T11 (short arrows). B, MRI of the of brain shows left anteromedial thalamic enhancing lesion. C, MRA of the brain: arrow shows stenosis of right posterior cerebral artery. Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; IFN, interferon; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

Forty days after the initial presentation, his symptoms stabilized, his encephalopathy improved, but he developed delirium. He was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin without effect. A brain MRI showed a new subacute left thalamic infarct (Figure 1B), enhancement of the left optic tract, and 2 new enhancing lesions in the spinal cord. He received a 5-week course of acyclovir and a 5-day course of steroids. His mental status, cranial neuropathies, and right leg hyperesthesia gradually resolved, and he regained limited motor but not functional strength in his legs. Repeat CSF analysis showed a white blood cell count of 32 cells/mm3 and glucose 9 mg/dL. Repeat MRI of the brain and spine was unchanged.

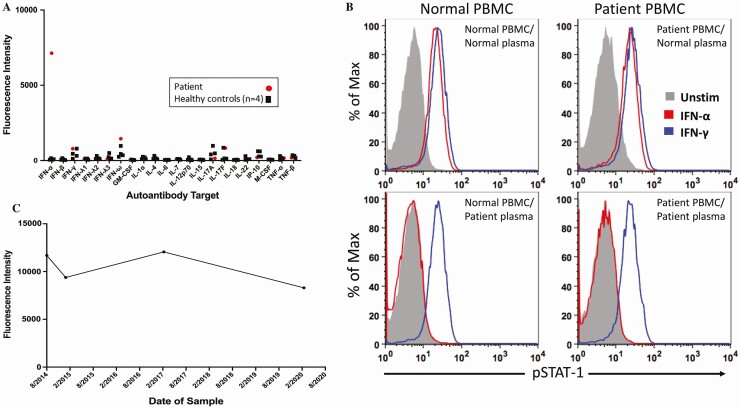

The patient was enrolled onto a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved clinical protocol (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00001355) and signed consent. Human experimentation guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services were followed in the conduct of clinical research. The patient was found to have elevated serum IgG antibody to IFN-α but not to other cytokines (Figure 2A). Further studies showed that his plasma had antibody that neutralized IFN-α but not IFN-γ. Addition of his plasma to PBMCs from a healthy control blood donor blocked the ability of IFN-α to activate and phosphorylate STAT1 (Figure 2B), although no impairment in IFN-γ mediated phosphorylation of STAT1 was observed. Addition of sera from a healthy control blood donor did not block IFN-α mediated phosphorylation of STAT1 in the patient’s PBMCs.

Figure 2.

Neutralizing anti-IFN-α antibodies in a man with VZV CNS vasculitis. A, Levels of serum antibodies to IFN-α and other cytokines. B, Control or patient PBMCs (5 × 105 cells) were incubated with 10% healthy control or patient plasma and then stimulated with IFN-α (1000 U/mL) or IFN-γ (400 U/mL). PBMCs were fixed, permeabilized, stained for phospho-STAT-1, and analyzed by flow cytometry. STAT1 phosphorylation was induced by addition of IFN-α (red) or IFN-γ (blue) to (a) PBMCs from normal control with plasma from normal control (upper left), (b) PBMCs from the patient with plasma from normal control (upper right), (c) PBMCs from normal control with plasma from the patient (lower left), and (d) PBMCs from the patient with plasma from the patient (lower right). pSTAT1 was measured by flow cytometry. C, Level of plasma antibodies to IFN-α over time. See Supplementary Data for additional methods. Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; IFN, interferon; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

Physical examination after the prolonged course of antivirals and corticosteroids showed improved mentation, but he had flaccid paralysis of the right leg with a positive Babinski sign. The CSF showed 28 cells/mm3 (93% lymphocytes) with a protein of 48 mg/dL and glucose of 46 mg/dL; VZV DNA was undetectable. IgG antibody to IFN-α was present in the CSF. The ratio of VZV antibody in the CSF (3.56 optical density units by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) to serum (2.05 optical density units by ELISA) was 1.74, suggesting intrathecal synthesis of VZV antibody in this man with apparent VZV CNS vasculitis. HSV1 and HSV2 antibodies were undetectable in the CSF and serum. MRI of the brain and spine showed degenerative evolution of his prior infarcts and thinning of the thoracic cord but no new lesions. Magnetic resonance angiography, for which there was no prior study for comparison, showed stenosis of the right posterior cerebral artery consistent with vascular involvement by VZV CNS vasculitis (Figure 1C). In addition to VZV CNS vasculitis, this patient had peripheral nervous system disease as evidenced by enhancement of the nerve roots on MRI and EMG findings of a peripheral neuropathy. A sural nerve biopsy showed a neuropathic process but did not show vasculitis. His clinical course, CSF laboratory results, and imaging studies showed a resolving neurologic process; however, his CSF remains intermittently positive for VZV DNA, and his serum IgG antibody to IFN-α remains elevated (Figure 2C). He is currently receiving valacyclovir (500 mg daily) as secondary prophylaxis for VZV. Six years after the initial onset of his disease he has not had a clinical relapse and with physical therapy his strength has improved in his left leg to 4/5 with trace movement in his right lower leg.

Evaluation of 38 additional serum samples from persons with VZV CNS vasculitis did not find other patients with elevated autoantibodies to IFN-α.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

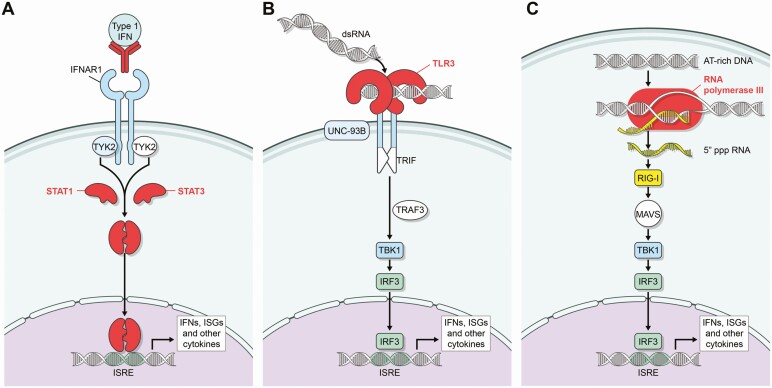

Although multiple genetic abnormalities have been associated with severe varicella or zoster, our review indicates that the cellular immune response, including T cells, NK cells, and iNKT cells are all important for controlling VZV. Recent findings have shown that multiple genetic variants in seemingly disparate genes are important for controlling the severity of varicella and zoster. Many of these gene products involve the IFN pathway either by antibody neutralizing the activity of IFN, mutation of IFNGR1, STAT1, STAT3, or TLR3, or impaired sensing of double-stranded RNA or AT-rich DNA resulting in impaired production of IFN (Figure 3). In contrast to HSV, which encodes multiple genes that block the activity of IFN [36], VZV encodes only 1 gene (IE63) known to block IFN. Thus, VZV may be more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of IFN than HSV.

Figure 3.

Sites at which proteins or antibodies associated with VZV diseases affect IFN signaling pathways. A, IFN binds to its receptor (IFNAR) which activates JAK and TYK2 resulting in phosphorylation of STATs, which translocate to the nucleus to activate ISGs. Antibody to IFN-α and proteins in which mutations are associated with severe VZV infections are indicated in red. B, Double-stranded RNA binds to TLR3, which activates TRIF, TRAF3, TBK1; and IRF3, which translocates to the nucleus to activate ISGs. C, AT-rich DNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase III resulting in 5′triphosphorylated RNA which activates RIG-I and results in IRF3 trafficking to the nucleus and activating ISGs. Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; ISG, interferon stimulated gene; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

IFN therapy has been proposed for patients with TLR3 signaling defects [22] and IFN-α has been used in patients with mutations in IFNGR1 to compensate for the defect in response to IFN-γ [37]. Because IFN-α and IFN-γ both are important for control of VZV, a similar approach might be considered for persons with certain primary immunodeficiencieswith severe VZV infections in which one of the IFN pathways is impaired. In vitro studies show that IFN-α delays the onset of VZV replication and spread, but IFN-γ is more potent than IFN-α to inhibit VZV replication [38]. Although many of the immunodeficiencies reviewed here involve type I IFN signaling pathways, patients with mutations in IFNGR1 or with anti-IFN-γ antibodies have had severe VZV infections [33] or more frequent zoster [39]. The role of rituximab in patients with anti-IFN or anti-cytokine autoantibodies associated with lung or skin infections is currently being studied (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT01842386).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Presented in part: American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 21 April 2016; Colorado Alphaherpesvirus Latency Symposium. Vail, Colorado, 19 May 2016; ID week 2017, San Diego, California, 4 October 2017; Herpes zoster: New Approaches and New Successes, 28 October 2019, Montreal, Canada.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. R. A. B. reports funding from the Veterans Health Administration and NIAID and reports research support from Merck, Tetraphase, VenatoRx, and Entasis for antibiotic resistance research. J. C. reports being issued a patent and royalties for Saer attenuated varicella-zoster virus vaccines with missing or diminished latency of infection. D. G. reports grants from the National Institute on Aging, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol 1999; 92:34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mace EM, Orange JS. Emerging insights into human health and NK cell biology from the study of NK cell deficiencies. Immunol Rev 2019; 287:202–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Novakova L, Lehuen A, Novak J. Low numbers and altered phenotype of invariant natural killer T cells in recurrent varicella zoster virus infection. Cell Immunol 2011; 269:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banovic T, Yanilla M, Simmons R, et al. Disseminated varicella infection caused by varicella vaccine strain in a child with low invariant natural killer T cells and diminished CD1d expression. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:1893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warnatz K, Draeger R, Schlesier M, Peter HH. Successful IL-2 therapy for relapsing herpes zoster infection in a patient with idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia. Immunobiology 2000; 202:204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wade NA, Lepow ML, Veazey J, Meuwissen HJ. Progressive varicella in three patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: treatment with adenine arabinoside. Pediatrics 1985; 75:672–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Crawford TO, Winkelstein JA, Carson KA, Lederman HM. Immunodeficiency and infections in ataxia-telangiectasia. J Pediatr 2004; 144:505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin E, Palmic N, Sanquer S, et al. CTP synthase 1 deficiency in humans reveals its central role in lymphocyte proliferation. Nature 2014; 510:288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen JI. Herpesviruses in the activated phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-δ syndrome. Front Immunol 2018; 9:237. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dobbs K, Domínguez Conde C, Zhang SY, et al. Inherited DOCK2 deficiency in patients with early-onset invasive infections. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2046–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li FY, Chaigne-Delalande B, Su H, Uzel G, Matthews H, Lenardo MJ. XMEN disease: a new primary immunodeficiency affecting Mg2+ regulation of immunity against Epstein-Barr virus. Blood 2014; 123:2148–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dang TS, Wilet JDP, Griffin HR, et al. Defective leukocyte adhesion and chemotaxis contributes to combined immunodeficiency in humans with autosomal recessive MST1 deficiency. J Clin Immunol 2016; 36:117–22.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heusinkveld LE, Yim E, Yang A, et al. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic strategies in WHIM syndrome immunodeficiency. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2017; 5:813–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abolhassani H, Edwards ES, Ikinciogullari A, et al. Combined immunodeficiency and Epstein-Barr virus-induced B cell malignancy in humans with inherited CD70 deficiency. J Exp Med 2017; 214:91–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Picard C, McCarl CA, Papolos A, et al. STIM1 mutation associated with a syndrome of immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1971–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dorman SE, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet 2004; 364:2113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Toubiana J, Okada S, Hiller J, et al. ; International STAT1 Gain-of-Function Study Group . Heterozygous STAT1 gain-of-function mutations underlie an unexpectedly broad clinical phenotype. Blood 2016; 127:3154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chapgier A, Kong XF, Boisson-Dupuis S, et al. A partial form of recessive STAT1 deficiency in humans. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:1502–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siegel AM, Heimall J, Freeman AF, et al. A critical role for STAT3 transcription factor signaling in the development and maintenance of human T cell memory. Immunity 2011; 35:806–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bezrodnik L, Di Giovanni D, Caldirola MS, Azcoiti ME, Torgerson T, Gaillard MI. Long-term follow-up of STAT5B deficiency in three argentinian patients: clinical and immunological features. J Clin Immunol 2015; 35:264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang SY, Casanova JL. Inborn errors underlying herpes simplex encephalitis: from TLR3 to IRF3. J Exp Med 2015; 212:1342–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sironi M, Peri AM, Cagliani R, et al. TLR3 mutations in adult patients with herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus encephalitis. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:1430–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liang F, Glans H, Enoksson SL, Kolios AGA, Loré K, Nilsson J. Recurrent herpes zoster ophthalmicus in a patient with a novel toll-like receptor 3 variant linked to compromised activation capacity in fibroblasts. J Infect Dis. 2019. pii: jiz229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carter-Timofte ME, Paludan SR, Mogensen TH. RNA polymerase III as a gatekeeper to prevent severe VZV infections. Trends Mol Med 2018; 24:904–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ogunjimi B, Zhang SY, Sørensen KB, et al. Inborn errors in RNA polymerase III underlie severe varicella-zoster virus infections. J Clin Invest 2017; 127:3543–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carter-Timofte ME, Hansen AF, Mardahl M, et al. Varicella-zoster virus CNS vasculitis and RNA polymerase III gene mutation in identical twins. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2018; 5:e500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carter-Timofte ME, Hansen AF, Christiansen M, Paludan SR, Mogensen TH. Mutations in RNA polymerase III genes and defective DNA sensing in adults with varicella-zoster virus CNS infection. Genes Immun 2019; 20:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gershon AA, Mervish N, LaRussa P, et al. Varicella-zoster virus infection in children with underlying human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis 1997; 176:1496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blank LJ, Polydefkis MJ, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Herpes zoster among persons living with HIV in the current antiretroviral therapy era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61:203–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Domingo P, Torres OH, Ris J, Vazquez G. Herpes zoster as an immune reconstitution disease after initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection. Am J Med 2001; 110:605–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wauters O, Lebas E, Nikkels AF. Chronic mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus infections. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 66:e217–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Adult-onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:725–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bayat A, Burbelo PD, Browne SK, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies in postherpetic neuralgia. J Transl Med 2015; 13:333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ansari R, Zerbe C, Lisco A, Rosen L, Holland S, Bonomo RA. Varicella-zoster virus neurovasculitis (VZV-NV) in the setting of autoantibodies to Interferon alpha (anti-IFNα). Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4(Suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leib DA. Counteraction of interferon-induced antiviral responses by herpes simplex viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2002; 269:171–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bax HI, Freeman AF, Ding L, et al. Interferon alpha treatment of patients with impaired interferon gamma signaling. J Clin Immunol 2013; 33:991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sen N, Sung P, Panda A, Arvin AM. Distinctive roles for type I and type II interferons and interferon regulatory factors in the host cell defense against varicella-zoster virus. J Virol 2018; 92:e01151–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chi CY, Chu CC, Liu JP, et al. Anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies in adults with disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infections are associated with HLA-DRB1*16:02 and HLA-DQB1*05:02 and the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus infection. Blood 2013; 121:1357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.