Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV)–attributable oropharyngeal cancer (HPV-OPC) incidence is increasing in many high-income countries among men. Factors associated with oral HPV persistence, the precursor of HPV-OPC, are unknown. Data from the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study, which followed participants >7 years, were utilized to examine rates of persistence and associated factors.

Methods

Oral gargle samples from 3095 HIM study participants were HPV genotyped using the SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 assay (DDL Diagnostic Laboratory). Oral HPV persistence for individual and grouped high-risk HPV types among 184 men positive for any high-risk HPV at their oral baseline visit was assessed at 6-month intervals. Factors associated with grouped high-risk HPV/HPV16 persistence were examined using logistic regression. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to examine median time to HPV clearance overall, and by selected risk factors.

Results

Among the 7 HPV vaccine types, HPV33 had the longest median duration (7.6 months) followed by HPV16 and HPV45 (6.4 months). 10–30% of oral high-risk HPV infections persisted ≥24 months. Six months’ persistence of oral high-risk HPV infections was positively associated with age and gingivitis and negatively with lifetime number of sexual partners, while 12 months’ persistence was only inversely associated with lifetime number of sexual partners. Oral HPV16 persistence was positively associated with baseline HPV16 L1 antibody status.

Conclusions

Eighteen percent of HPV16 infections persisted beyond 24 months, potentially conferring higher risk of HPV-OPC among these men. Older age appears to be an important factor associated with oral high-risk HPV persistence. More studies among healthy men are required to understand the progression of oral HPV infection to HPV-OPC.

Keywords: oral HPV, HPV persistence, oropharyngeal cancer, HIM study, oral HPV clearance

Among 184 men with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in the HIM study, HPV clearance was associated with younger age, absence of gingivitis, and higher lifetime number of sexual partners; HPV16 clearance was associated with absence of HPV16 L1 antibodies.

The incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)–attributable oropharyngeal cancers (OPCs) among men is on the rise in high-resource countries globally [1, 2]. There is a lack of knowledge about the transition of oral HPV infection to OPC. However, based on HPV natural history at other anatomic sites, it is very likely that oral HPV persistence is an obligate precursor of HPV-attributable OPC [3]. To date, few studies have reported on the natural history of oral HPV infections [4, 5]. In the past decade, factors associated with persistence of prevalent high-risk HPV infections among the population with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and at high risk of HIV was reported, as well as a study examining persistence of oral HPV infection among families [5, 6]. However, there is a lack of long-term prospective studies examining factors associated with oral HPV natural history, especially HPV16, the genotype most commonly found in HPV-attributable OPC, among a general, at-risk population of men. The goal of this study was to describe the percentage of prevalent oral high-risk and HPV16 infections that persist and to examine factors associated with persistence of these infections among healthy men participating in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study.

METHODS

Study Population

The HIM study was a prospective cohort study of men residing in 3 countries: Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Eligibility criteria for enrollment into the study included age between 18–70 years; residing in São Paulo (Brazil), Cuernavaca (Mexico), or Tampa, Florida (USA); no previous diagnosis of penile or anal cancers; no previous reporting of genital or anal warts; no previous participation in an HPV vaccine study; no previous diagnosis of HIV; no current history of penile discharge or burning during urination; no current treatment for sexually transmitted infections; had not been imprisoned or homeless during the past 6 months; had not received drug treatment in past 6 months; did not have plans to relocate for the next 4 years; and were willing to comply with scheduled visits every 6 months for the next 4 years.

Men were recruited according to 3 age groups (18–30 years, 31–44 years, and 45–70 years) from 3 different population sources: general population, universities, and organized healthcare systems. In Brazil, men were recruited from a large genitourinary/HIV/sexually transmitted infection clinic in São Paulo and the general population via advertisements on television and radio and in newspapers. In Mexico, men were recruited from factories and the military via a large healthcare plan in the city of Cuernavaca. In the United States, men were recruited from the University of South Florida and the general community. More details regarding recruitment have been previously published [7]. All study procedures were approved by the human subjects’ research committees of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo; the Centro de Referencia e Tratamento de Doencas Sexualmente Transmissiveis e AIDS, São Paulo; the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico, Cuernavaca, Mexico; and the University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida.

All consenting participants initially underwent a clinical examination approximately 2 weeks before the enrollment visit and every 6 months thereafter. Only men who returned for the enrollment visit were included in the study. Men who provided oral gargle samples at every study visit for more than 2 study visits (n = 3095) were included in this study. Participants who were oral gargle positive for any high-risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68 at their enrollment visit were included in this study of oral HPV persistence (n = 184). At each successive study visit the number of participants with available adequate samples for HPV genotyping were 184, 184, 173, and 161, at visits 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. In addition, all available oral cell specimens archived past visit 5 were HPV genotyped.

Procedures

Methods related to the collection of oral gargle samples, DNA extraction, and purification have been previously described [8]. Human papillomavirus genotyping was performed via the SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 system (DDL Diagnostic Laboratory, Rijswijk, The Netherlands). The SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 system is an in vitro reverse hybridization assay [9]. The LiPA25 targets a 65-base-pair fragment of the L1 region of the HPV genome. This assay requires a 3-step process: (1) quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) that determines sample adequacy; (2) a DNA enzyme immunoassay (DEIA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method that detects 65 HPV types; and (3) an line probe assay (LiPA25)genotyping multiplex PCR that selectively identifies the following HPV types by reverse hybridization: 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 34, 35, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68/73, 70, and 74. All samples that were considered adequate in step 1 were further analyzed via steps 2 and 3.

Statistical Analyses

The distribution of sociodemographic, sexual behavior, and oral health factors was examined. Most of the men in the cohort had a single HPV-type infection at enrollment. Persistence of an individual HPV genotype was defined as detection of the same HPV genotype at 2 or more consecutive study visits scheduled approximately 6 months apart, while grouped (high-risk/low-risk) HPV persistence was defined as the persistence of any individual HPV genotype in that group. Oral HPV persistence at study visits 2 (6-month visit), 3 (12-month visit), 4 (18-month visit), and 5 (24-month visit) was evaluated for each individual high-risk HPV type and grouped high-risk and low-risk HPV types. In rare cases (n = 12 at third visit) where an intervening HPV-negative test occurred between successive study visits where that specific HPV genotype was detected continuously at 2 or more visits, the participant was considered oral HPV persistent for that genotype at that study visit (ie, +–++). Bivariate- and multivariable- adjusted associations between each potential sociodemographic, sexual behavioral, and oral health factors and grouped high-risk HPV and HPV16 persistence at the second and third study visits were examined in logistic regression models. Factors that were significantly or marginally associated with grouped high-risk HPV or HPV16 persistence at the second visit were fit in individual multivariable models adjusting for age at study enrollment and country of residence, as these were study design variables. To assess median time to clearance, Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed for individual HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (the 7 high-risk HPV types included in the nonvalent HPV vaccine) using the exact time of follow-up at which either an HPV infection cleared or the participant was lost to follow-up as the end point. Kaplan-Meier curves were also constructed for grouped high-risk HPV and HPV16 persistence, stratifying by factors significantly associated with their persistence at the second study visit. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival distributions between groups in these Kaplan-Meier curves. All analyses were conducted with R (version 4.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with 2-sided tests.

Role of the Funding Source

The study sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, or analysis. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants were followed for a median of 44.8 months (range: 11.9–98.0 months; interquartile range: 26.1 months; mean: 49.5 months). The mean age of participants at enrollment was 35.8 years (SD: 10.0 years) with relatively even distribution across the age groups. Approximately half of the participants were married or cohabiting, 79% were heterosexual, 38% reported having a lifetime number of sexual partners of more than 19, 27% reported more than 30 days since their last oral sex, 80% reported never having gingivitis, and 74% reported not having any teeth extracted due to gum disease, gingivitis, or decay (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemo graphic Characteristics of Study Participants Testing Oral HPV Positive at First Study Visit

| Characteristic | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 35.8 (10.0) |

| Median (range) | 36.0 (19.0, 72.0) |

| 18–30 years | 59 (32.1) |

| 31–40 years | 68 (37.0) |

| 41–73 | 57 (30.9) |

| Country of residence | |

| Brazil | 65 (35.3) |

| Mexico | 73 (39.7) |

| United States | 46 (25.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 68 (37.0) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 24 (13.0) |

| Married/cohabiting | 91 (49.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| MSW | 145 (78.8) |

| MSWM | 16 (8.7) |

| MSM | 8 (4.4) |

| Never had sexa | 5 (2.7) |

| Missing | 10 (5.4) |

| Lifetime number of sex partners | |

| ≤2 | 32 (17.4) |

| 3–7 | 30 (16.3) |

| 8–19 | 48 (26.1) |

| >19 | 70 (38.0) |

| Refused | 2 (1.1) |

| Missing | 2 (1.1) |

| Lifetime number of female partners | |

| ≤2 | 22 (12.0) |

| 3–7 | 35 (19.0) |

| 8–19 | 46 (25.0) |

| >19 | 59 (32.1) |

| Refused | 20 (10.9) |

| Missing | 2 (1.1) |

| Lifetime number of male partners | |

| ≤2 | 160 (87.0) |

| 3–7 | 4 (2.2) |

| 8–19 | 2 (1.1) |

| >19 | 12 (6.5) |

| Refused | 3 (1.6) |

| Missing | 3 (1.6) |

| Number of new female sexual partners in the past 6 months | |

| 0 | 49 (26.6) |

| 1 | 70 (38.0) |

| 2+ | 58 (31.5) |

| Refused | 6 (3.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) |

| Number of new male sexual partners in the past 6 months | |

| 0 | 163 (88.6) |

| 1 | 6 (3.3) |

| 2+ | 11 (6.0) |

| Refused | 1 (0.5) |

| Missing | 3 (1.6) |

| Number of times oral sex given or received in the past 6 months | |

| 0 | 49 (26.6) |

| 1–6 | 56 (30.4) |

| 7–24 | 41 (22.3) |

| 25+ | 25 (13.6) |

| Refused | 9 (4.9) |

| Missing | 4 (2.2) |

| Number of days since last oral sex (given or received) | |

| Never had oral sex during lifetime | 14 (7.6) |

| >30 | 49 (26.6) |

| >10–30 | 35 (19.0) |

| >3–10 | 32 (17.4) |

| 0–3 | 47 (25.5) |

| Refused | 3 (1.6) |

| Missing | 4 (2.2) |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Never | 69 (37.5) |

| Former | 53 (28.8) |

| Current | 56 (30.4) |

| Missing | 6 (3.3) |

| Pack-years of cigarette smoked | |

| 0 | 77 (41.8) |

| >0–5 | 58 (31.5) |

| >5 | 43 (23.4) |

| Refused | 6 (3.3) |

| Missing | 10 (5.4) |

| Currently chewing tobacco or using snuff | |

| None | 167 (90.8) |

| Sometimes | 8 (4.4) |

| Daily | 7 (3.8) |

| Missing | 2 (1.1) |

| Number of drinks of any alcoholic beverage consumed in the past 1 month | |

| None | 39 (21.2) |

| 1–30 | 73 (39.7) |

| >30 | 64 (34.8) |

| Refused | 5 (2.7) |

| Missing | 3 (1.6) |

| Ever had gingivitis | |

| No | 148 (80.4) |

| Yes | 29 (15.8) |

| Missing | 7 (3.8) |

| Number of teeth extracted due to gum disease, gingivitis, or decay | |

| 0 | 136 (73.9) |

| 1+ | 40 (21.7) |

| Missing | 8 (4.4) |

| Consistent bleeding of gums after brushing or presence of swollen gums | |

| No | 145 (78.8) |

| Yes | 32 (17.4) |

| Missing | 7 (3.8) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. N = 184. Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; MSM, men who have sex with men only; MSW, men who have sex with women only; MSWM, men who have sex with women and men.

aNever had oral, vaginal, or anal sex during their lifetime.

Oral High-Risk HPV Persistence and Median Time to Clearance

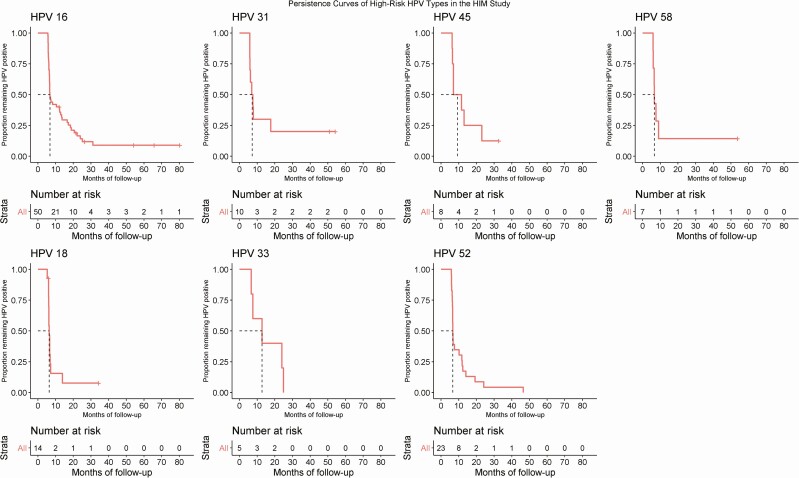

Of the 184 men who tested positive for any high-risk HPV genotype at their baseline visit, 11 men dropped out or their specimens were inadequate and hence HPV data were missing at the fourth visit. An additional 12 men were lost to follow-up at the fifth visit. The median duration of follow-up from study visit 1 to study visits 2, 3, 4, and 5 was 6.4, 12.8, 19.8, and 26.2 months, respectively. Among high-risk HPV types, HPV39 had the highest proportion persisting at the fifth visit (31.8%) followed by HPV31 (30%) and HPV56 (23.5%). Persistence of HPV16 was 18.0% at the fifth visit (month 24). Persistence of high-risk HPV and low-risk HPV at the fifth study visit was 20.1% and 2.9%, respectively (Table 2). The median time to clearance of HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 was 6.4, 6.0, 5.8, 7.6, 6.4, 6.0, and 5.9 months, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Percentage of Men With Persistent Oral HPV Infections at the 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-Month Clinical Visits

| HPV Type | No. of Men Positive at First Visit | Persistence at Second Visit (Month 6) (N = 184), n (%) | Persistence at Third Visit (Month 12) (N = 184), n (%) | Persistence at Fourth Visit (Month 18) (N = 173), n (%) | Persistence at Fifth Visit (Month 24) (N = 161), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 50 | 18 (36.0) | 14 (28.0) | 12 (24.0) | 9 (18.0) |

| 18 | 14 | 2 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.1) |

| 31 | 10 | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) |

| 33 | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| 35 | 8 | 4 (50.0) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| 39 | 22 | 14 (63.6) | 11 (50.0) | 8 (36.4) | 7 (31.8) |

| 45 | 8 | 4 (50.0) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) |

| 51 | 31 | 10 (32.3) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (19.4) | 6 (19.4) |

| 52 | 23 | 7 (30.4) | 3 (13.0) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (8.7) |

| 56 | 17 | 8 (47.1) | 5 (29.4) | 5 (29.4) | 4 (23.5) |

| 58 | 7 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) |

| 59 | 7 | 6 (85.7) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) |

| 68/73 | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| High-risk HPV | 184 | 76 (41.3) | 58 (31.5) | 49 (26.6) | 37 (20.1) |

| Low-risk HPV | 105 | 4 (3.8) | 4 (3.8) | 4 (3.8) | 3 (2.9) |

Any visit without detected HPV but preceded by a visit with positive infection and followed by 2 visits with positive infection was considered positive for a given HPV genotype (ie, +–+ +). Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

Figure 1.

Time to clearance of prevalent detected individuals at high risk of oral HPV infection. Abbreviations: HIM Study, HPV Infection in Men Study; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Factors Associated With High-Risk HPV and HPV16 Oral Infections

In multivariable-adjusted analyses, persistence of grouped high-risk oral HPV at the second visit, scheduled at 6 months, was significantly higher among men reporting recent oral sex (>3–10 days prior to study visit; adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.90; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.26–22.11) and among those reporting having had a diagnosis of gingivitis during adulthood (OR, 2.70; 95% CI: 1.18–6.46). Risk of persistence was significantly lower among men reporting a lifetime number of 8–19 sex partners compared with men reporting 0–2 partners (OR, .32; 95% CI: .12–.82). However, oral high-risk HPV persistence at the third, 12-month, visit was only independently inversely associated with lifetime number of sex partners (8–19 partners vs 0–2 partners; aOR, .24; 95% CI: .08–.67) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Any High-Risk HPV Genotype Persistence at Second (Month 6) and Third (Month 12) Clinical Visits

| Persistence at Second Visit | Persistence at Third Visit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics at Baseline |

OR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) |

| Age | ||||

| 18–30 years | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 31–40 years | 2.53 (1.22, 5.43) | … | 1.75 (.81, 3.89) | … |

| 41–73 years | 2.42 (1.13, 5.33) | … | 1.84 (.82, 4.21) | … |

| P-trendb | .03 | .15 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 2.31 (.90, 6.07) | 1.61 (.58, 4.56) | 2.35 (.89, 6.23) | 2.07 (.72, 6.02) |

| Married/cohabiting | 1.47 (.77, 2.84) | 1.14 (.55, 2.36) | 1.28 (.64, 2.60) | 1.29 (.59, 2.81) |

| Lifetime number of sex partners | ||||

| ≤2 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 3–7 | .59 (.21, 1.60) | .52 (.18, 1.51) | .43 (.14, 1.24) | .48 (.15, 1.45) |

| 8–19 | .36 (.14, .91) | .32 (.12, .82) | .26 (.09, .70) | .24 (.08, .67) |

| >19 | .70 (.30, 1.62) | .69 (.28, 1.65) | .60 (.26, 1.42) | .55 (.22, 1.32) |

| P-trendb | .49 | .48 | .35 | .17 |

| Number of days since last oral sex (given or received) | ||||

| Never had oral sex during lifetime | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| >30 | 2.21 (.64, 8.95) | 3.18 (.89, 13.34) | 1.20 (.31, 5.98) | 1.45 (.36, 7.41) |

| >10–30 | 1.30 (.35, 5.55) | 1.77 (.46, 7.81) | 1.03 (.24, 5.39) | 1.28 (.29, 6.94) |

| >3–10 | 3.65 (.99, 15.74) | 4.90 (1.26, 22.11) | 2.94 (.74, 14.99) | 3.44 (.83, 18.17) |

| 0–3 | 1.06 (.30, 4.38) | 1.40 (.38, 5.99) | 1.72 (.45, 8.48) | 2.14 (.54, 10.97) |

| P-trendb | .65 | .71 | .14 | .11 |

| Diagnosis of gingivitis during adulthood | ||||

| No | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Yes | 2.61 (1.17, 6.09) | 2.70 (1.18, 6.46) | 1.11 (.46, 2.53) | 1.04 (.43, 2.41) |

| Number of teeth extracted due to gum disease, gingivitis, or decay | ||||

| 0 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| ≥1 | 2.25 (1.11, 4.67) | 1.97 (.94, 4.21) | 1.31 (.62, 2.73) | 1.13 (.51, 2.44) |

P values <.05 are shown in bold. Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; OR, unadjusted odds ratio; Ref, reference.

aAdjusted for age at baseline and country of residence.

b P value of ordinal trend in the variable.

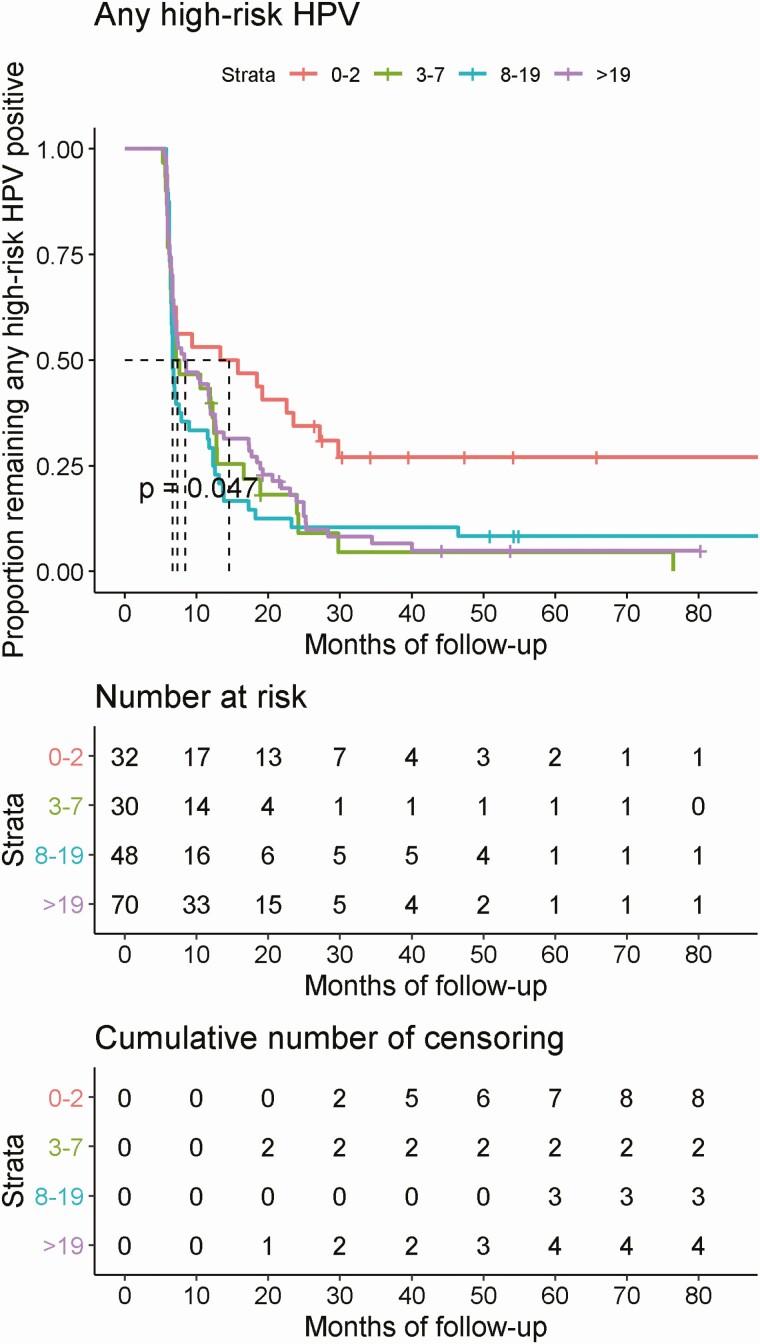

In Kaplan-Meier curves fitted using actual duration of follow-up, median time to clearance of high-risk oral HPV was significantly different by lifetime number of sexual partners (P = .047) (Figure 2) but did not significantly differ by age at enrollment, diagnosis of gingivitis during adulthood, or number of teeth lost due to gum disease, gingivitis, or decay (data not shown). The median time to clearance of grouped oral high-risk HPV was 13.35 months, 7.13 months, 6.67 months, and 5.91 months for number of lifetime sexual partners of 0–2, 3–7, 8–19, and more than 19, respectively.

Figure 2.

Clearance of prevalent detected infection of any high-risk HPV by lifetime number of sex partners. Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

In bivariate- and multivariable-adjusted analyses, persistence of HPV16 at the second study visit was significantly higher among those with detectable HPV16 L1 antibody at enrollment compared with those who were antibody negative (OR, 4.45; 95% CI: 1.12–20.04; aOR, 9.11; 95% CI: 1.67–77.91) (Table 4). No factors were observed to be associated with oral HPV16 persistence at the 12-month time point. As the risk estimate for the association between HPV16 antibody status and oral HPV16 persistence was approximately 2 fold higher after adjustment for age, we examined whether there was effect modification by age. In stratified analyses, the association between HPV16 antibody and persistent oral HPV16 risk was restricted to men ages 31–40 years (OR, 12.0; 95% CI: 1.20–293.63), however, the interaction term was not statistically significant (data not shown).

Table 4.

Factors Associated With HPV16 Persistence at Second (Month 6) and Third Clinical Visits (Month 12)

| Persistence at Second Visit | Persistence at Third Visit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at Baseline | OR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) |

| Age | ||||

| 18–30 years | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 31–40 years | 1.04 (.25, 4.30) | … | 1.77 (.39, 8.52) | … |

| 41–73 years | 3.50 (.81, 16.58) | … | 3.54 (.72, 19.11) | … |

| P-trendb | .12 | .13 | ||

| Lifetime number of sex partners | ||||

| ≤7 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| >7 | .33 (.09, 1.08) | .31 (.07, 1.22) | .61 (.16, 2.27) | 0.58 (.13, 2.53) |

| Number of teeth extracted due to gum disease, gingivitis, or decay | ||||

| 0 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| ≥1 | 3.18 (.84, 12.99) | 2.32 (.50, 10.85) | 1.44 (.32, 5.86) | 1.24 (.22, 6.22) |

| HPV16 antibody | ||||

| Negative (<0.2 OD) | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Positive (≥0.2 OD) | 4.45 (1.12, 20.04) | 9.11 (1.67, 77.91) | 1.93 (.42, 8.27) | 2.94 (.52, 17.05) |

P values <.05 are shown in bold. Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; OD, optical density; OR, unadjusted odds ratio; Ref, reference.

aAdjusted for age at baseline and country of residence.

b P value of ordinal trend in the variable.

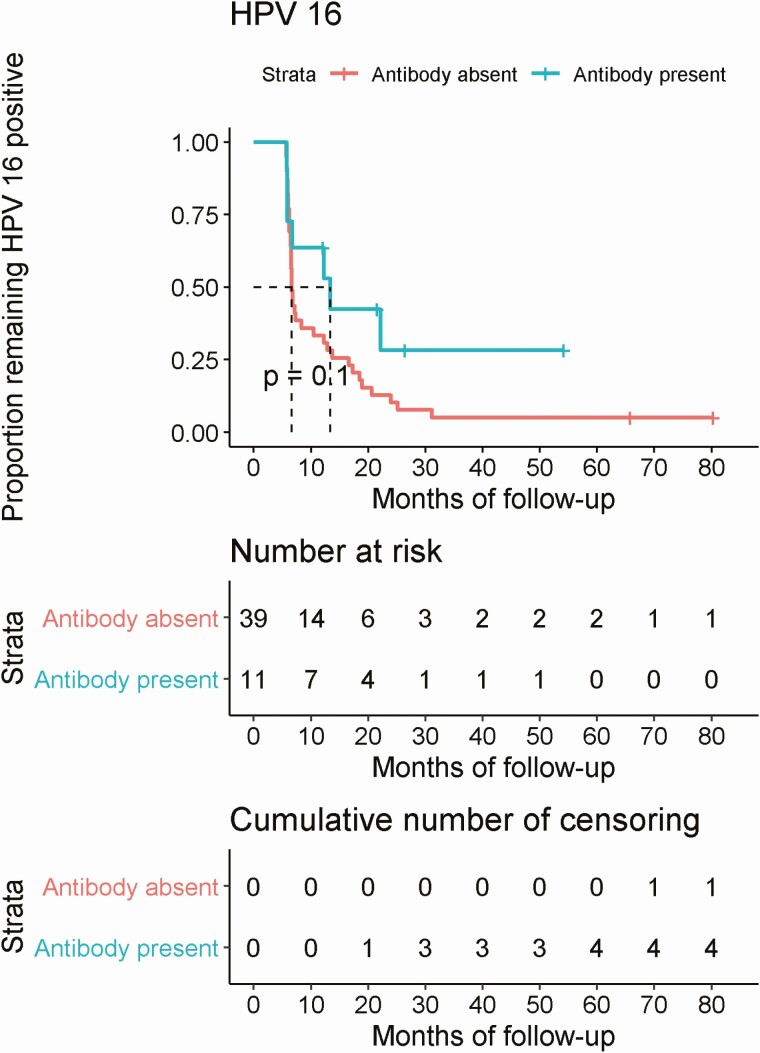

In Kaplan-Meier curves fitted using actual duration of follow-up, median time to clearance of oral HPV16 was marginally significantly different by HPV16 L1 antibody status (P = .1), whereby median time to clearance was 6.64 months among men who were antibody negative and approximately 2-fold higher at 13.35 months among men who were antibody positive (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time to clearance of prevalent detected HPV16 infection by HPV16 antibody status at baseline. Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

DISCUSSION

Among a healthy population of men, most oral high-risk HPV infections cleared within 24 months. However, 10–30% of these infections continued to persist for 24 months or longer, conferring risk for subsequent development of OPC. Short-term persistence of oral high-risk HPV infections was positively associated with gingivitis and inversely associated with lifetime number of sexual partners, but persistence at 12 months or longer was only associated with lifetime number of sexual partners. The only factor associated with oral HPV16 persistence was HPV16 L1 antibody status. Although in bivariate analyses older age was associated with increased risk of oral HPV persistence, age was not associated in multivariable analyses, nor did time to oral HPV clearance vary by age.

Median time to clearance of oral HPV16 was 6.4 months among men in the HIM study compared with 16.8 months, which was reported in a recent study conducted among men at high risk for HIV and men living with HIV [5]. Differences in median duration estimates between studies are likely due to immunosuppression among men with HIV, which results in lower viral clearance and therefore higher persistence at all anatomic sites studied. This higher persistence may explain the 2-fold higher incidence of OPC among men living with HIV compared with HIV-negative men [10]. While the median time to clearance of HPV genotypes 39 and 59 was twice that of HPV16, these HPV types are rarely detected in OPC tumors. The association between these non-HPV16 high-risk genotypes and OPC tumors requires further investigation.

Oral HPV prevalence has consistently been shown to be higher among mid-adult-aged men. As such, several studies have investigated whether older age was also associated with increased risk of acquisition and persistence. We previously observed in the HIM study that age was positively associated with oral HPV acquisition. In this current analysis we did observe a 2-fold higher risk of high-risk oral HPV persistence among mid-adult and older aged men; however, median time to clearance was not different by age. In the persistent oral papillomavirus study (POPS)/Men and women understanding throat HPV study (MOUTH) study of men at high risk of and/or living with HIV, men aged older than 30 years had a high-risk HPV persistence at 6 months compared with men aged 18–30 years [5], consistent with studies of other populations including a preliminary analysis of the HIM study population [11, 12]. When examining oral HPV16 specifically, both 6- and 12-month persistence appeared higher (OR, ~3.5) in the oldest age group of men aged 41–73 years; however, these associations did not reach statistical significance. Clearly, more large studies that allow sufficient power to examine HPV16 separately and inclusive of more diverse populations are needed to clarify the association between age and oral HPV persistence.

In the current study, a higher number of lifetime sexual partners was inversely associated with oral HPV persistence. Previous studies such as the POPS/MOUTH study [5] and the Finnish Family HPV study (married men) [6] did not find an association between sexual behavior and high-risk HPV persistence. In the current study, men reporting a number of 0–2 sex partners had significantly higher persistence compared with men with 8–19 sex partners. This was an unexpected and curious finding that led us to consider that perhaps the high exposure with more sexual partners may have led to the development of a protective antibody. Unfortunately, the HIM study had only previously tested for antibodies against HPV6, 11, 16, and 18, so we were limited in testing this hypothesis to oral HPV16 persistence. In fact, we observed a strong association between antibodies to HPV16 L1 and oral HPV16 persistence. Antibody positivity was associated with higher risk of persistence, not lower risk. Few studies have examined the association between antibody status and HPV risk among men; as such, it is unclear whether antibodies elicited to natural infection are protective or only markers of virus exposure. Previous studies have shown that HPV16 L1 antibodies were not protective against subsequent oral HPV16 infection [13, 14].

This is the first study reporting an association between oral health factors and high-risk oral HPV persistence. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between oral health factors such as chronic periodontitis and oropharyngeal cancer in case-control studies [15, 16]. This study establishes a potential temporal association between oral health, high-risk HPV persistence, and subsequent OPC. One of the major strengths of this study is the inclusion of men from a wide range of sociodemographic and sexual risk strata, enabling us to examine factors associated with oral HPV persistence and clearance among healthy men. The HIM study participants were followed for more than 7 years, which makes this one of the longest prospective studies among a general population of men. Limitations include lack of a sample size to conduct extensive multivariable analyses for either grouped or individual HPV types and lack of HPV viral load data, which other studies have identified as being associated with oral HPV clearance [5].

In conclusion, while most high-risk oral HPV infections among men clear within 2 years, 10–30% remain persistent and therefore at risk for the development of OPC. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of age, lifetime number of sex partners, and HPV L1 antibodies on the natural history of these oral infections and risk of progression to cancer.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 CA214588; to A. R. G.). R. R. R. reports a grant (P30-CA076292) from the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. L. L. V. reports personal consulting fees from Merck & Co, outside the submitted work. A. R. G. reports grants from Merck & Co, Inc, and personal fees (advisory board member and consultant) from Merck & Co, Inc, during the conduct of the study. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:4294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Näsman A, Attner P, Hammarstedt L, et al. Incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) positive tonsillar carcinoma in Stockholm, Sweden: an epidemic of viral-induced carcinoma? Int J Cancer 2009; 125:362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lowy DR, Herrero R, Hildesheim A; Participants in the IARC/NCI Workshop on Primary Endpoints for Prophylactic HPV Vaccine Trials . Primary endpoints for future prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccine trials: towards infection and immunobridging. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:e226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pierce Campbell CM, Kreimer AR, Lin HY, et al. Long-term persistence of oral human papillomavirus type 16: the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015; 8:190–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D’Souza G, Clemens G, Strickler HD, et al. Long term persistence of oral HPV over 7 years of follow-up. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kero K, Rautava J, Syrjänen K, Willberg J, Grenman S, Syrjänen S. Smoking increases oral HPV persistence among men: 7-year follow-up study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 33:123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, et al. The human papillomavirus infection in men study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008; 17:2036–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bettampadi D, Sirak BA, Fulp WJ, et al. Oral HPV prevalence assessment by linear array vs. SPF10 PCR-DEIA-LiPA25 system in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) study. Papillomavirus Res 2020; 9:100199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kleter B, van Doorn LJ, ter Schegget J, et al. Novel short-fragment PCR assay for highly sensitive broad-spectrum detection of anogenital human papillomaviruses. Am J Pathol 1998; 153:1731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frisch M, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92:1500–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. JAMA 2012; 307:693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreimer AR, Villa A, Nyitray AG, et al. The epidemiology of oral HPV infection among a multinational sample of healthy men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20:172–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pierce Campbell CM, Viscidi RP, Torres BN, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) L1 serum antibodies and the risk of subsequent oral HPV acquisition in men: the HIM study. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:45–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beachler DC, Viscidi R, Sugar EA, et al. A longitudinal study of human papillomavirus 16 L1, e6, and e7 seropositivity and oral human papillomavirus 16 infection. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42:93–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tezal M. interaction between chronic inflammation and oral HPV infection in the etiology of head and neck cancers. Int J Otolaryngol 2012; 2012:575242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tezal M, Nasca MS, Stoler DL, et al. Chronic periodontitis− human papillomavirus synergy in base of tongue cancers. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 135:391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]