Abstract

Tuberculosis incidence in the United States is declining, yet projections indicate that we will not eliminate tuberculosis in the 21st century. Incidence rates in regions serving the rural and urban poor, including recent immigrants, are well above the national average. People experiencing incarceration and homelessness represent additional key populations. Better engagement of marginalized populations will not succeed without first addressing the structural racism that fuels continued transmission. Examples include:(1)systematic underfunding of contact tracing in health departments serving regions where Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) live;(2) poor access to affordable care in state governments that refuse to expand insurance coverage to low-income workers through the Affordable Care Act;(3) disproportionate incarceration of BIPOC into crowded prisons with low tuberculosis screening rates; and(4) fear-mongering among immigrants that discourages them from accessing preventive health services. To eliminate tuberculosis, we must first eliminate racist policies that limit essential health services in vulnerable communities.

Keywords: structural racism, vulnerable populations, social determinants, health insurance, rural health

Current projections indicate the US is unlikely to eliminate tuberculosis this century. We elucidate the role of structural racism in maintaining tuberculosis disparities. Interventions that address structural racism are more likely than incremental adjustments within current structural constraints to reduce the burden of tuberculosis.

For most residents of the United States, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection invokes a problem from a different epoch, conjuring images from The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, Giacomo Puccini’s opera La Bohème, or Charles Dickens and the Victorian era. Tuberculosis incidence in the United States has been on the decline since a surge in the 1980s–1990s, down to 2.8 cases per 100 000 in 2018 from nearly 10 cases per 100 000 in 1993. However, the case rates in California, New York City, Washington, DC, Louisiana, and Texas are well above the national average [1]. Tuberculosis in the United States continues to threaten vulnerable populations.

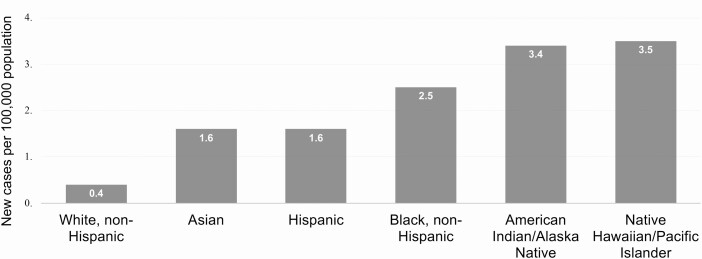

Within the context of an overall low annual incidence, TB rates can vary more than 4-fold between regions in low-incidence countries, with higher rates where homelessness, overcrowding, and recent immigrant communities are prevalent [2]. Tuberculosis is accurately termed a socially determined disease that reflects economic, racial/ethnic, and health disparities in the United States (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

New cases of tuberculosis per 100 000 population in the United States in 2019, by race and ethnicity. Source: US Department Health and Human Services/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/pdfs/mm6911a3-H.pdf.

Structural racism is the cumulative effect of discriminatory historical, economic, political, and interpersonal systems, patterns, and practices that result in persistent poor health, social, economic, and other conditions for racial minorities [3]. The role of structural racism on disproportionately poor healthcare access, treatment, and outcomes is receiving renewed attention in light of the burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and amid global protests against anti-Black police violence [4]. A long history of scholarship can be highlighted as to the role of structural racism, and a related concept, anti-Blackness, on the health of vulnerable communities [5–8]. Anti-Blackness is contempt towards and the acceptance of structural and/or literal violence against Black people [9, 10]. It posits violence against Black people as normative to social order, manifesting in the United States through chattel slavery, Jim Crow policies and violence, and mass incarceration. These underscore a belief, whether conscious or subconscious, that white supremacy is normative. Anti-Blackness begins to explain the staggering disparities in health and other social experiences of Black people. It is important to, where relevant, be specific about which structurally marginalized racial group is at risk because sometimes racism alone may not be fully explanatory [11].

While racial disparities in US TB incidence have been previously described and rightly attributed to the social meaning of race rather than to biological differences [12], there are growing calls for disentangling race from racism. By moving beyond associations between BIPOC identities and disease, we can investigate the impact of structural racism and intersecting forms of oppression on infectious-disease incidence, outcomes, and other health disparities [13].

The final hurdles for TB elimination are daunting, as they involve reaching, engaging, and supporting diagnosis, treatment, and prevention in structurally marginalized populations [14]. In the United States, these populations-of-interest include people living in underserved rural communities, those who have been incarcerated, people experiencing homelessness, and recent immigrant communities. We highlight the elements of structural racism in exclusionary policies and deliberate government choices that functionally deny access to TB-prevention services to structurally marginalized populations.

RURAL POVERTY AND HEALTH SERVICES

A case study is informative. In 2016, the Alabama Public Health Department reported 47 cases of TB in Perry County [15]. Between 2014 and 2016, Marion, Alabama (population ~3300), within rural Perry County (population of ~9200), experienced a TB outbreak resulting in at least 3 deaths [16]. At the height of the epidemic, Marion had an incidence of 253 cases per 100 000, rivaling the rates of TB infection in some of the world’s highest-burden countries [17].

Marion’s population is 63% Black and characterized by generations of poverty and limited access to healthcare [17]. Life expectancy in Perry County is less than the national average by more than 7 years; only 1 clinic in the city provides X-rays [17]. Eighteen hospitals in Alabama have closed since 2000, most in rural areas. When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted in 2010, the Alabama state government chose not to expand Medicaid, leaving many working poor and BIPOC residents without health insurance, continuing limited access to affordable healthcare [15]. Turning away the federal support to expand Medicaid is a first example of structural racism at the state government level that afflicts BIPOC populations disproportionately; racial bias in the failure to expand Medicaid is consistent with a demonstrated history of racial bias in social welfare allocation [18]. States with higher population proportions of Black residents and where White support for the ACA (nicknamed Obamacare) has been low were found to be significantly less likely to expand Medicaid, whereas Black support for the ACA was not found to correlate with likelihood of expansion [18]. States that did not expand Medicaid have higher proportions of Black people compared with states that chose to expand Medicaid [19]. As a result, low-income BIPOC working families are less likely to be insured where White political leaders, with support from White voters, have chosen not to accept the federal support to expand Medicaid eligibility [18, 19].

In the beginning of the TB epidemic in 2016, Marion’s Black residents delayed seeking care; a commonly cited reason was a desire to keep others from “knowing [their] business” [15]. Marion is 110 miles west of Tuskegee, the venue of the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in the impoverished “black belt” agricultural region of Alabama [20]. While Marion residents did not cite the Tuskegee experiments, they invoked their wariness of medical professionals, passed on through generations of family members, for their delays in seeking TB care. Residual mistrust of medical professionals lingers from memories of deliberate withholding of care for BIPOC, as with the penicillin therapy denial for syphilis-infected Black men in the Tuskegee study. Marion, Alabama, illustrates how a distrustful relationship between community members and health officials, endemic poverty, and limited access to quality healthcare services nurtures TB transmission even within a “low burden” country. Fractured relationships between communities and health officials are legacies of denial of services, exploitation of research subjects, and modern-day failures to ensure health insurance access through the ACA for the working poor. These represent structural racism inhibiting TB control and prevention.

INCARCERATION AND HOMELESSNESS

Correctional facilities are another setting where TB incidence remains relatively high. More than 2 million persons have been incarcerated in the United States; our nation has the highest per-capita incarceration rate in the world (698 per 100 000 adults in 2018) (Table 1) [21]. In 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the criminal justice system oversaw almost 2.3 million people (down ~200 000 by July due to COVID-19) in 1833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, 80 Indian Country jails, military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and carceral venues in the US territories such as Puerto Rico [22]. Further, Black persons are 5.9 times, Hispanic/Latinx persons 3.1 times, and Native Americans 4.0 times more likely to be incarcerated compared with White people [23, 24]. Black neighborhood residence correlates with an increased likelihood of arrest [11, 25]. Racism is the plausible reason why possession of powdered cocaine, favored by White people, carries a lower penalty than crack cocaine, favored by Black people. Across the board, once arrested, Black people are given harsher sentences than White people for the same crimes [23].

Table 1.

Countries With the Highest Number of Prisoners per 100,000 People

| Country | No. per 100 000 Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | United States | 639 |

| 2. | El Salvador | 565 |

| 3. | Turkmenistan | 552 |

| 4. | Palau | 522 |

| 5. | Rwanda | 511 |

| 6. | Cuba | 510 |

| 7. | Maldives | 499 |

| 8. | Thailand | 498 |

| 9. | Northern Mariana Islands (US) | 482 |

| 10. | Virgin Islands (UK) | 447 |

Source: World Prison Brief, Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research https://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-tolowest/prison_population_rate?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All.

Nearly 40% of all diagnosed TB cases in the United States were among individuals who interacted with a jail, prison, juvenile detention facility, or other carceral venues [22]. The population at risk for infection includes inmates as well as prison staff and visitors from the community [26]. Latent TB is a major driver of the epidemic in low-incidence countries. However, prisoners with latent TB are significantly less likely than those with active TB to have their follow-up care arranged prior to their release [22]. Prisoners are also frequently relocated during their imprisonment and are not always tested when they arrive at a new facility, contributing to the 1990s TB outbreak in a New York State prison [22].

The Alabama Correctional System experienced a TB outbreak in 2014. All cases in this outbreak were linked to the St Clair Correctional Facility, which at the time housed 300 more individuals than it was built to hold [27]. This was the most severe outbreak that had taken place in an Alabama prison within the 5 previous years, and followed a legal battle in which the Alabama Department of Corrections had been accused of inadequate care of sick and injured inmates. Given chronic crowding and underfunding of Alabama prisons with disproportionately large Black carceral populations, TB spread is another consequence of structural racism.

Beyond the biology of TB, social and behavioral factors play a role in the high incidence of TB in correctional facilities compared with the general US population. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) incidence in carceral settings is about 5 times higher than in the general population [28]. Before improvements in access to antiretroviral treatment, HIV-related immunosuppression was an important driver of TB infection in the United States [29]. There is also a connection between injection drug use and TB infection [30]. HIV infection and subsequent immunosuppression may account for some of this intersection, alongside housing and food insecurities [30]. Further, people who smoke cigarettes have twice the risk of both TB infection and active disease [30]. Social and behavioral issues associated with drug use contribute to poor adherence and therefore poor TB outcomes for people with histories of incarceration and/or HIV coinfection [31].

Homelessness is an important risk factor for incarceration. The rate of recent homelessness among adult incarcerated people was 7.5 to 11.3 times higher than in the general population [32]. The complex interaction of mental illness, substance use, and inadequate stocks of affordable housing all contribute to the relationship between homelessness and incarceration. Further, Black people are more likely to experience homelessness than White people across all 50 states [33].

We know that 70% of Black individuals without a high school diploma will be incarcerated by their mid-30s [31]. A review of TB cases from 2004–2012 found that, for recently transmitted disease, Black people had an average incidence rate 25 times greater than White people, after controlling for place of birth, sex, and age [12]. The distribution of TB incidence in the community and in carceral facilities reproduces social inequality and threatens to further entrench health disparities in the United States.

IMMIGRATION

A further manifestation of the role that social marginalization and structural racism play in the epidemiology of TB in low-incidence settings is the contribution of immigration to TB. California is our most populous state and it has the nation’s largest share of TB. Of the 2133 cases of TB in California in 2016, 79% originated from activated latent TB, while only 14% were attributable to transmission within the state [34]. Latent TB among migrant populations or “non–US-born” residents of California is thought to explain much of the state’s TB incidence [35, 36].

Latent TB is an important driver of TB incidence in other settings with large non–US-born populations as well including New York, Texas, and Florida [35, 36]. The majority of non–US-born Americans who develop TB are thought to be previously infected with the bacteria from a contact in their home country, and their latent disease becomes activated at some future point upon settling in the United States. Immigrants applying for permanent residency are screened for TB, but screening requirements for those traveling on tourist or student visas or immigrants who are undocumented are less rigorous [35].

Hostility and policy restrictions targeting undocumented immigrants also spill over to legal immigrants [37]. This xenophobia has deleterious consequences for accurate contact-tracing and disease-prevention efforts as it entrenches an adversarial relationship between state actors and immigrant communities, not dissimilar to what contributed to a glacially paced response to the outbreak of TB in Marion, Alabama. Anti-immigrant sentiment and policies restricting healthcare access are yet another example of structural racism.

MAKING PROGRESS TOWARDS TUBERCULOSIS ELIMINATION

There are several possible approaches to the elimination of or reduction in the burden of TB among persons within key populations most likely to become infected. They range from overall poverty alleviation and more equitable expansion of healthcare access in rural areas to global health investments in the high-burden origin countries of non–US-born Americans. Attending to the role of structural racism, anti-Blackness, and xenophobia in creating differential risk is critical to ameliorating the social determinants that shape TB burden in the United States.

Racist policies are underlying causes of ongoing TB transmission in the United States through marginalization, exclusion, incarceration, and insurance disenfranchisement of BIPOC and immigrant populations. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, screening those who may have latent TB should be accompanied by TB-screening efforts in groups at higher risk for TB, namely persons with diabetes, with alcohol-use disorders, living with HIV, who inject or otherwise use drugs, who are experiencing homelessness, and who live in correctional settings or were recently released [38]. While a sense of individual risk is a helpful start for screening, transformative intervention necessitates a systems view. There are biological components to the immunological risk from diabetes, substance-use disorders (SUDs), and HIV infection; however, socioeconomic factors, racism, and access to care for SUDs and mental health underlie correctional facility residence, homelessness, and racial disparities in frequency and consequences of diabetes, SUDs, or HIV disease [39, 40]. Structural approaches that attend to disease risk in the context of broader social, economic, and political vulnerability have also been proposed in HIV-prevention efforts [13]. As there are undeniable structural factors that shape the risk profile of these populations, in our view a systems view of TB incidence illuminates several possible points of intervention.

Structural racism is the antecedent to the following major systems drivers of TB, in contrast to individual risk factors: (1) denial of Medicaid expansion to the working poor via the ACA and cutbacks in public health services has affected BIPOC disproportionately; (2) historic exploitation of BIPOC communities in health research has generated mistrust; (3) mass incarceration of BIPOC is accompanied by, in most settings, attendant overcrowding, inadequate healthcare, and poor linkage to community health service upon release; (4) underinvestment in jobs training, low-cost housing, and mental health and substance-use treatment services fails to remediate homelessness and unemployment; and (5) anti-immigrant sentiment and punitive policies towards healthcare insurance coverage for the working poor or for undocumented immigrants deny preventive and curative services to persons needing them the most. Table 2 illustrates the relationship between the challenges we identify and the possible structural solutions we propose both proximally and distally.

Table 2.

Tuberculosis Drivers Influenced by Structural Racism and Proximal and Distal Solutions

| TB Drivers | Proximal Solution | Distal Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to access healthcare due to income, immigration status, or residence in a state which refused to expand the Affordable Care Act | Provide formerly standard health department services to all rural and urban areas with higher TB incidence rates, including enhanced capacities in testing, contact tracing, and ability to provide directly observed therapy | Universal healthcare |

| Historic exploitation of BIPOC communities in health research | Engage community members from study conception and design—well before participant recruitment | Pipeline programs for BIPOC to study medicine, biomedicine, nursing, and public health |

| Mass incarceration of BIPOC | Screening for latent TB at the point of mid-detention facility transfer or release | Decarceration and provision of community mental health, substance-use services, and job training and placement |

| Homelessness | Housing assistance upon release and needed health services for those experiencing homelessness | Affordable housing creation and establishment of accessible mental health and substance-use services |

| Lack of safety net supports for undocumented people | Health fairs in immigrant communities that screen without respect to immigration status | Decriminalizing immigration; enabling all residents of the United States to access preventive public health services |

Abbreviations: BIPOC, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color; TB, tuberculosis.

Systems-level change should ensure adequate health department services to all rural and urban areas with higher TB incidence rates, including enhanced capacities in testing, contact tracing, and ability to provide directly observed therapy. Further, critical transformations key to addressing TB in the United States include optimized care in prisons along with decarceration policies and housing assistance upon release. Health services for the homeless with social services for substance use, mental health, job training, and subsidized housing can help reduce TB risks. Universal healthcare insurance, whether through existing options like the ACA or more expansive programs, can remove barriers to effective primary care and prevention. Immigrant-friendly universally available TB services are critical to reducing the incidence of TB in the United States. Ultimately, health policies must be responsive to the concentration of poverty and limited access to health careers that continues to entrench health disparities in rural Black and other BIPOC communities across the United States.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number P30 MH062294 to S. H. V.).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. Both authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data & statistics: TB. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm. Accessed 17 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ali M. Treating tuberculosis as a social disease. Lancet 2014; 383:2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017; 389:1453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barber S. Death by racism. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geronimus AT. The effects of race, residence, and prenatal care on the relationship of maternal age to neonatal mortality. Am J Public Health 1986; 76:1416–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mullings L. Resistance and resilience: the sojourner syndrome and the social context of reproduction in central Harlem. Transform Anthropol 2005; 13:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health 2010; 100(Suppl 1):S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000; 90:1212–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross KM. Call it what it is: anti-blackness . The New York Times. June 4, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/04/opinion/george-floyd-anti-blackness.html. Accessed 8 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dumas MJ. Against the dark: antiblackness in education policy and discourse. Theory Pract 2016; 55:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lett E, Asabor EN, Corbin T, Boatright D. Racial inequity in fatal US police shootings, 2015–2020. J Epidemiol Community He alth 2020. doi: jech-2020-215097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noppert GA, Wilson ML, Clarke P, Ye W, Davidson P, Yang Z. Race and nativity are major determinants of tuberculosis in the U.S.: evidence of health disparities in tuberculosis incidence in Michigan, 2004–2012. BMC Public Health 2017; 17:538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doshi RK, Bowleg L, Blankenship KM. Tying structural racism to HIV viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 2015; 45:928–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder A. In Rural Alabama, a longtime mistrust of medicine fuels a tuberculosis outbreak. The New York Times. January 17, 2016. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/18/us/in-rural-alabama-a-longtime-mistrust-of-medicine-fuels-a-tuberculosis-outbreak.html. Accessed 19 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barrett P. News release Alabama Department of Public Health. Available at: www.adph.org. Accessed 19 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouyang H. Report: Where health care won’ t go. Harper’s Magazine. Available at: https://harpers.org/archive/2017/06/where-health-care-wont-go/. Accessed 19 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grogan CM, Park SE. The racial divide in state Medicaid expansions. J Health Polit Policy Law 2017; 42:539–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samantha A, Kendal O, Anthony D. Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lichtenstein B, Pettway T, Weber J. Sharecropper’s tuberculosis: pathologies of power in a fatal outbreak. Med Anthropol 2018; 37:499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prison Policy Initiative. States of incarceration: the global context 2018. Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2018.html. Accessed 17 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viglianti EM, Iwashyna TJ, Winkelman TNA. Mass incarceration and pulmonary health: guidance for clinicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15:409–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Sentencing Project. Report to the United Nations on racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system. Available at: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/. Accessed 27 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rich JD, Wakeman SE, Dickman SL. Medicine and the epidemic of incarceration in the United States. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2081–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hinton E, Brief VE.. An unjust burden: the disparate treatment of Black Americans in the criminal justic e system. Brooklyn, New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis in prisons. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins SPK. Alabama prisons are facing a record-breaking tuberculosis outbreak. ThinkProgress. Available at: https://thinkprogress.org/alabama-prisons-are-facing-a-record-breaking-tuberculosis-outbreak-c8bb38f2f4c5/. Accessed 17 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bose S. Demographic and spatial disparity in HIV prevalence among incarcerated population in the US: a state-level analysis. Int J STD AIDS 2018; 29:278–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis trends—United States, 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6410a2.htm. Accessed 19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deiss RG, Rodwell TC, Garfein RS. Tuberculosis and illicit drug use: review and update. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet 2017; 389:1464–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59:170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Alliance to End Homelessness. New data on race, ethnicity and homelessness. Available at: https://endhomelessness.org/new-data-on-race-ethnicity-and-homelessness/. Accessed 19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goodell AJ, Shete PB, Vreman R, et al. Outlook for tuberculosis elimination in California: an individual-based stochastic model. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0214532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Menzies NA, Hill AN, Cohen T, Salomon JA. The impact of migration on tuberculosis in the United States. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2018; 22:1392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shrestha S, Hill AN, Marks SM, Dowdy DW. Comparing drivers and dynamics of tuberculosis in California, Florida, New York, and Texas. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196:1050–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Immigration Council. The criminalization of immigration in the United States. Available at: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/criminalization-immigration-united-states. Accessed 19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends 2019: data & statistics: TB. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/statistics/tbtrends.htm. Accessed 28 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Reports 2002; 117(Suppl 1):S135. Available at: /pmc/articles/PMC1913691/?report=abstract. Accessed 28 October 2020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hill J, Nielsen M, Fox MH. Understanding the social factors that contribute to diabetes: a means to informing health care and social policies for the chronically ill. Perm J 2013; 17:67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]