Abstract

We review the three prevailing approaches—specificity, cumulative risk, and dimensional models— to conceptualizing the developmental consequences of early-life adversity and address fundamental problems with the characterization of these frameworks in a recent Perspectives on Psychological Science piece by Smith and Pollak (2020). We respond to concerns raised by Smith and Pollak about dimensional models of early experience and highlight the value of these models for studying the developmental consequences of early-life adversity. Basic dimensions of adversity proposed in existing models include threat/harshness, deprivation, and unpredictability. These models identify core dimensions of early experience that cut across the categorical exposures that have been the focus of specificity and cumulative risk approaches (e.g., abuse, institutional rearing, chronic poverty); delineate aspects of early experience that are likely to influence brain and behavioral development; afford hypotheses about adaptive and maladaptive responses to different dimensions of adversity; and articulate specific mechanisms through which these dimensions exert their influences, conceptualizing experience-driven plasticity within an evolutionary-developmental framework. In doing so, dimensional models advance specific falsifiable hypotheses, grounded in neurodevelopmental and evolutionary principles, that are supported by accumulating evidence and provide fertile ground for empirical studies on early-life adversity.

Keywords: adversity, early-life stress, threat, deprivation, harshness, unpredictability, experience-driven plasticity

The focus of Smith and Pollak’s (2020) recent paper on early-life adversity showcases many ideas for characterizing the early environment, a vibrant arena of inquiry among developmental scholars. Smith and Pollak make a number of useful points in their review of early-life adversity models. We appreciate the attention they pay to the importance of identifying biologically plausible mechanisms through which early experience shapes development. Especially important is the need to distinguish exposures and experiences. To our way of thinking, exposures capture the probability of something occurring rather than being a direct measurement of what a child actually experiences. Two children may be exposed to the same thing (e.g., parental substance abuse), but may not have the same experience (e.g., harsh punishment). In this case, parental substance abuse is an exposure that increases the likelihood that a child will be harshly punished, whereas harsh punishment is a feature or ingredient of the exposure that the child actually experiences. It is experiences such as harsh punishment that are particularly influential in explaining why children exposed to parental substance abuse are at elevated risk for developing psychopathology. Such experiences, therefore, provide more precise targets for effective intervention, at least at the individual level.

The exposure–experience distinction and the importance of identifying neurodevelopmental mechanisms are profoundly resonant for those of us who have developed dimensional models of early-life adversity, and we applaud the continued focus on them. However, for much of the review Smith and Pollak posit that there is little utility in recently proposed dimensional approaches to understanding the impact of adversity on neurobiology. We disagree with many of the arguments advanced in their paper and respond to these arguments here. First, we clarify distinctions between dimensional models and other conceptualizations of early-life adversity; then, we address four specific criticisms that Smith and Pollak raise regarding dimensional models.

Dimensional Models of Environmental Experience are not Specificity Models

Smith and Pollak frame their argument as “Conceptual Problems with Specificity Models” (pg. 5). In doing so, they recast dimensional models of early experience as “specificity models,” something we regard as a fundamental conceptual misunderstanding. Their paper presents a set of ideas that do not accurately reflect dimensional models. To address this misunderstanding, we first review critical differences between the “specificity models” Smith and Pollak describe and the dimensional models they confuse them with.

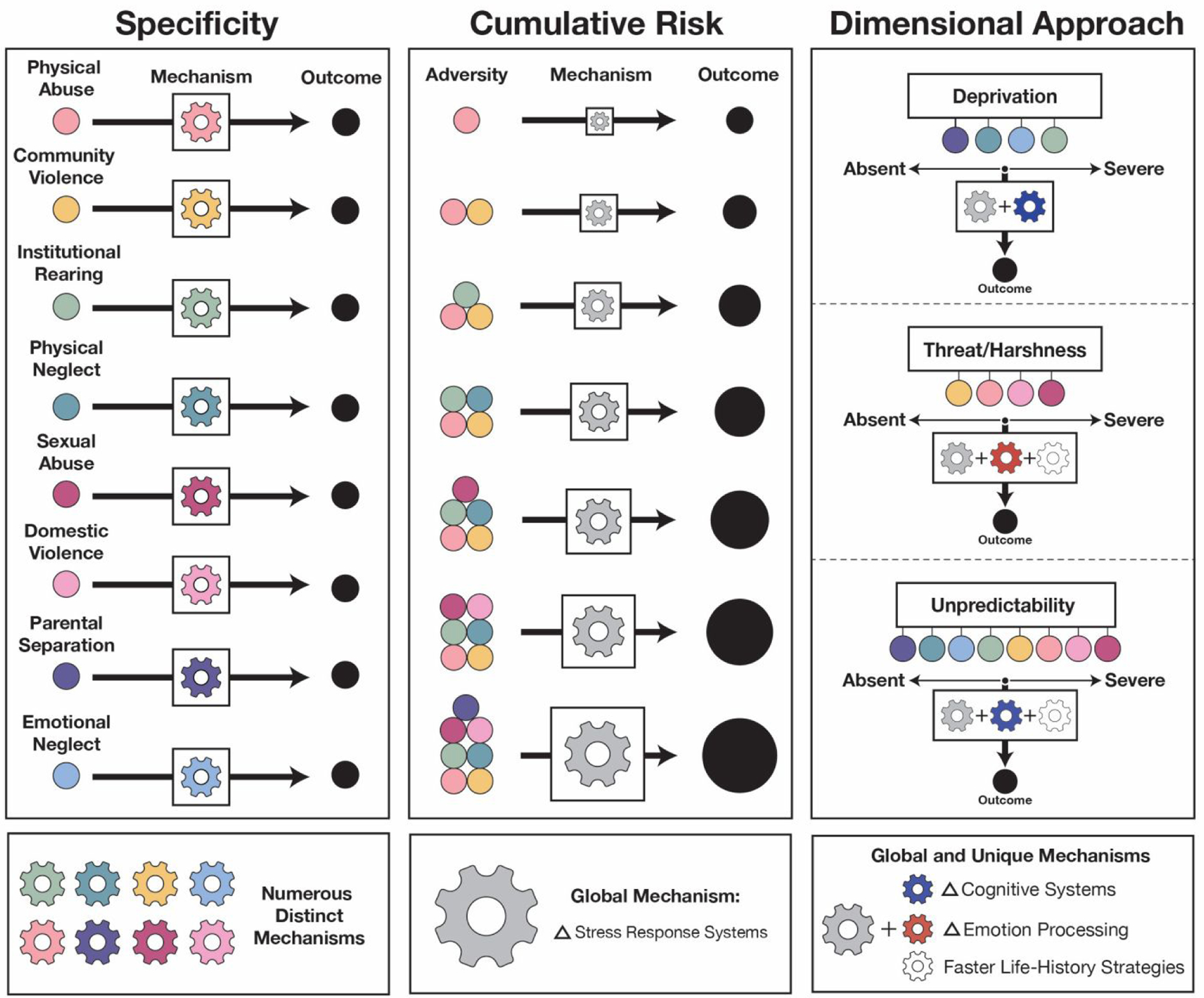

Historically, research on early-life adversity has taken either a specificity or cumulative-risk approach (see Figure 1). Specificity models and the research they stimulated focus on effects of individual adversities, such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, parental death, parental divorce, and chronic poverty. As we have discussed elsewhere (McLaughlin, 2020; McLaughlin, Sheridan, & Lambert, 2014) and as raised by Smith and Pollak, specificity models suffer from several fairly significant limitations. First, they fail to account for adversity co-occurrence—a point we return to later. Because children often experience multiple forms of adversity, studies that only measure a single adversity are unable to determine whether an association between a particular exposure (e.g., parental substance abuse) and developmental outcome (e.g., depression) is truly a consequence of the focal adversity or of other potentially co-occurring experiences (e.g., physical abuse). Second, specificity models assume that the mechanisms linking different adversities with developmental outcomes are distinct (Figure 1). This fails to appreciate that some mechanisms may be similar for different types of adversity that share common features (e.g., physical abuse and witnessing domestic violence may increase the likelihood of anxiety through similar mechanisms involving altered threat-related processing).

Figure 1. Approaches for conceptualizing childhood adversity.

Three distinct approaches have been used for assessing exposure to adversity in childhood and studying the mechanisms through which these experiences influence developmental outcomes. Adversity experiences are depicted in colored circles, developmental mechanisms (i.e., cognitive, emotional, social, and neurobiological processes influenced by adversity) are depicted with a gear symbol, and Δ symbolizes change. Outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety, poor school performance) are depicted in black circles, though we acknowledge that the associations between different forms of adversity and specific outcomes may vary. The specificity approach involves measuring adversity experiences individually (i.e., one at a time), and assumes that developmental mechanisms influenced by different forms of adversity are largely distinct. Cumulative-risk involves counting the number of discrete adversity exposures and experiences, assuming that the effects of distinct adversities on developmental outcomes are equal and additive. Mechanisms through which these adversities influence development are often not specified and implicitly assumed to be general (i.e., shared across adversity types). Dimensional models were developed to address the limitations of specificity and cumulative-risk approaches. These models identify core dimensions of experience that occur in multiple types of adversity that can be assessed continuously as a function of the severity or chronicity of adversity experiences. Dimensional models specify the developmental mechanisms most likely to be influenced by these aspects of experience, including some that are shared across multiple dimensions (e.g., changes in the functioning of stress response systems) and others that are unique to certain dimensions. Experiences of deprivation are posited to relate most strongly to changes in cognitive development, whereas experiences of threat/harshness are most strongly related to changes in emotion processing and faster life history strategies, including earlier pubertal maturation and risky sexual behavior. Unpredictability is related to cognitive schemas that prioritize short-term versus long-term rewards, executive function components involved in monitoring changing environments (e.g., attention shifting), and faster life history strategies.

Appreciation of the co-occurrence of different adversities led to a transition from specificity models to the cumulative-risk approach (Figure 1). Cumulative-risk counts the number of adversity exposures and experiences to create a risk score without regard to the type, chronicity, or severity of the experience. A child who experienced physical abuse, domestic violence, and community violence would have a risk score of three; a child who experienced emotional neglect, physical neglect, and maternal depression would also have a risk score of three. Cumulative-risk assumes that discrete forms of adversity have additive effects on developmental outcomes, and that no single form of adversity is more essential or important than another (Evans et al., 2013). Although this approach has proved productive in illustrating the breadth of health outcomes associated with multiple adversities, the cumulative-risk approach lacks clear specification about the underlying mechanisms through which these disparate experiences might influence diverse features of development. Cumulative-risk approaches have focused largely on disruptions in stress response systems and allostatic load as potential explanatory pathways (Evans & Kim, 2007). In other words, while the cumulative-risk model has proven informative when it comes to prediction, it proves rather lacking when it comes to identifying mechanistic processes that could inform intervention.

Dimensional models were advanced explicitly as alternatives to both specificity and cumulative-risk approaches (Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, 2009; Humphreys & Zeanah, 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2014; Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2014) (Figure 1). These models are based on the notion that it is possible to identify core underlying dimensions of environmental experience that occur across numerous types of adversity that share common features. Rather than placing children into categories of exposure, like parental substance abuse or physical abuse, dimensional models focus on aspects of experience that can be measured along a continuum. In addition, dimensional models are concerned with linking variation in early experiences to specific mechanistic processes, advancing hypotheses about the affective, cognitive, and neurobiological mechanisms that are most likely influenced by particular dimensions of early experience. Finally, dimensional models focus on the functional significance of different aspects of experience in adaptively guiding behavior.

Dimensional models specify several core features of early experience that are likely to shape development. One such model rooted in understanding of experience-driven plasticity distinguishes experiences that involve threat, which encompasses harm or threat of harm to the child, from those reflecting deprivation, which involves an absence of expected inputs from the environment during development, such as cognitive and social stimulation (McLaughlin, Sheridan, & Lambert, 2014; Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2014). These dimensions cut across numerous exposures that involve the core feature of threat or deprivation to varying degrees. For example, threat of harm to the child occurs in physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; witnessing domestic violence; and exposure to other forms of violence. The degree of threat involved in chronic physical abuse is (typically) higher than that involved in occasional exposure to community violence, but both experiences share a core feature of threat of harm to the child. This model makes predictions about domains of affective, cognitive, and neural development that are both similarly and differentially influenced by experiences of threat and deprivation.

A second dimensional model, guided by evolutionary life history theory, differentiates experiences that involve harshness, which encompasses extrinsic sources of morbidity and mortality, from those reflecting unpredictability, which involves stochastic variation in harshness (Ellis et al., 2009). Extrinsic refers to environmentally-mediated causes of morbidity and mortality that cannot generally be attenuated or prevented by the individual (e.g., family or community violence). A core assumption of evolutionary life history models is that development is structured by resource-allocation tradeoffs—such as when increased inflammatory host response to fight infection trades off against lower ovarian function in women or reduced musculoskeletal function in men—and that such tradeoffs coordinate morphology, physiology, and behavior in ways that promote reproductive fitness (or once did) under different environmental conditions recurrently experienced over evolutionary history. These coordinated patterns (instantiated in such characteristics as timing of reproduction, levels of risky and aggressive behaviors, and parenting quality) are referred to as life history strategies. Harshness and unpredictability constitute distinct contextual dimensions that regulate variation in development of life history strategies across and within species.

Each of these models focuses on identifying underlying features of environmental experience that are shared across many adversity exposures and can be measured along a continuum ranging from absent to severe. The conceptualization and empirical study of early experience using these dimensional models is just beginning, and developers of dimensional approaches have frequently noted that initially proposed dimensions are only starting points for characterizing the early environment.

A Response to Smith and Pollak’s Four Problems with Dimensional Models

Dimensional models do not advocate placing children into discrete categories of exposure

The first problem Smith and Pollak raise about dimensional models is that “subtypes of adverse experiences are fuzzy categories” (p. 5). After recasting dimensional models as specificity models, they contend that dimensional approaches advocate for placing children into “separate groups who have had [purportedly] different experiences” (p. 5). This framing fundamentally misrepresents the purpose of dimensional approaches, which seek to move beyond placement of children into single exposure categories as in specificity models and lumping all exposures together as in cumulative-risk. Instead, dimensional models seek to identify the shared mechanisms through which diverse early experiences influence different aspects of development (e.g., see Figure 1 in McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016). Smith and Pollak’s (2020) claim that threat and deprivation reflect “fuzzy categories” fundamentally misrepresents what dimensional models seek to accomplish (irrespective of whether they succeed or not).

Admittedly, numerous challenges exist in defining and operationalizing core underlying dimensions of early experience. This is particularly true for deprivation and unpredictability. Exposure to the dimension of threat/harshness has been operationalized as the number of different types of violence a child has encountered or the overall frequency of violence exposure. Deprivation has been primarily studied as a lack of learning opportunities and stimulation, but it may be useful to consider separate dimensions of cognitive, material, and emotional deprivation, each of which may have unique developmental consequences and mediating processes (Dennison et al., 2019; King, Humphreys, & Gotlib, 2019). Measuring unpredictability presents numerous conceptual and methodological hurdles (Young, Frankenhuis, & Ellis, 2020), such as defining statistical properties of unpredictability in relation to social and non-social environmental factors. New measurement tools informed by dimensional models are sorely needed. Existing assessments were developed to assess the presence of discrete exposures (e.g., parental substance abuse, neglect) rather than dimensions of experience. Moreover, tools that measure children’s experience in their natural environments (e.g., devices that measure the child’s language environment [LENA] and caregiver–child proximity [TotTags]) will be particularly important for capturing variation in experiences of deprivation and unpredictability, which are difficult to assess using only self- or caregiver-reports (King, Querdasi, Humphreys, & Gotlib, 2020).

Contrary to Smith and Pollak’s argument that dimensional models seek to place children into “separate categories” based on different experiences, a central tenet of these models is that it is essential to measure and model multiple dimensions of experience simultaneously (Belsky, Schlomer, & Ellis, 2012; McLaughlin, 2020; McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016). Nevertheless, they are correct in pointing out that in initial studies threat, deprivation, harshness, and unpredictability have sometimes been measured using dichotomous indicators of relevant experiences (e.g., abuse reflecting the presence of threat, neglect reflecting the presence of deprivation). This practice reflects the difficulty of applying recently-developed dimensional models to existing data collected using case-control designs aimed at identifying children with and without particular types of experiences. In such designs, children typically fall into two groups—those exposed to a relatively extreme form of adversity (e.g., abuse) and those who never encountered adversity, posing problems for modeling these experiences continuously. Shifting to a dimensional approach requires sampling strategies that capture not only children with the most severe experiences, but also those in the mild-moderate range. As research on these topics has progressed, experiences of threat, deprivation, and unpredictability have been increasingly measured continuously, consistent with dimensional models (Hein et al., 2020; Goetschius et al., 2020; Lambert et al., 2017; Machlin et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2018; 2020).

In sum, dimensional models seek to identify and measure core features of environmental experience as dimensions that vary along a continuum of severity and occur to varying degrees in diverse forms of adversity (see Supplemental Figure 1). This affords the possibility of evaluating whether, how, and why these underlying aspects of experience shape developmental processes.

Problem 2: Co-occurrence of adversities does not mean that it is impossible to examine differential effects

A second claim of Smith and Pollak is that the co-occurrence of adversity poses a fundamental problem for dimensional models. However, dimensional models are predicated on the understanding that adversities co-occur (Belsky et al., 2012; McLaughlin, 2020; McLaughlin et al., 2014). Without addressing this co-occurrence by assessing multiple dimensions of experience, it would be easy to misattribute variance associated with a particular adversity to another co-occurring one. For this reason, dimensional models stipulate measuring multiple dimensions of adversity simultaneously, and only then examining their associations (distinctly and jointly) with developmental outcomes. Any study examining a single form of adversity alone with no consideration of other aspects of adversity would not be considered to be taking a dimensional approach and would be instead applying a specificity approach.

One fundamental—and widely appreciated—concern about co-occurrence discussed by Smith and Pollak is that it can introduce problems of multi-collinearity in statistical analysis. They present a few examples of adversity studies documenting co-occurrence rates in the moderate range. More comprehensive approaches to examining adversity co-occurrence—including prevalence rates in population-based studies and meta-analyses—detect associations in the small to moderate range (Matsumoto, Piersiak, Letterie, & Humphreys, 2020; McLaughlin et al., 2012). There is debate about the specific thresholds used to determine multicollinearity, but the cutoff most often used for correlations among predictors that is likely to result in problematic variance inflation is strikingly large (.80) and substantially larger than the observed associations among even the most strongly co-occurring adversities. Moreover, a growing number of statistical approaches beyond multiple regression have been implemented to account for adversity co-occurrence when evaluating the associations of multiple adversity types with developmental outcomes. These include latent class analysis (Ballard et al., 2015), network models (Goetschius et al., 2020; Sheridan, Shi, Miller, Salhi, & McLaughlin, 2020), and bifactor models that characterize the unique and shared variance in early experiences of adversity (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2019).

In sum, the overlap between multiple adversities is not sufficiently high that it creates problems for disentangling whether particular aspects of experience have differential associations with developmental outcomes, and there are numerous strategies for handling this co-occurrence. The fact that adversities co-occur is not a reasonable justification for assuming that all adversities are created equal.

Problem 3: Consistent differences in the downstream consequences of different dimensions of early experience have been observed

The third critique advanced by Smith and Pollak is that “It is not clear from extant data that there are consistent and replicable effects associated with different types of early childhood adversities” (pg. 8). We contend that their effort to substantiate this claim empirically is lacking, though we acknowledge that much of the relevant research is relatively recent. Indeed, a number of recent empirical studies designed specifically to evaluate propositions of dimensional models yield evidence consistent with these ideas. This includes work supporting the predicted distinctions between threat and deprivation in their associations with a range of developmental outcomes, such as amygdala reactivity to threat, aversive learning, cognitive control, and even pubertal timing (Goetschius et al., 2020; Hein et al., 2020; Lambert, King, Monahan, & McLaughlin, 2017; Machlin, Miller, Snyder, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, 2019; Miller, Machlin, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, 2020; Miller et al., 2018; Peckins et al., 2020; Rosen, Meltzoff, Sheridan, & McLaughlin, 2019; Sheridan, Peverill, & McLaughlin, 2017; Sheridan et al., 2020; Sumner, Colich, Uddin, Armstrong, & McLaughlin, 2019; Sun, Fang, Wan, Su, & Tao, 2020; Wolf & Suntheimer, 2019). Perhaps the strongest evidence comes from systematic reviews and meta-analyses that document clearly divergent associations of threat and deprivation with neural structure and function (McLaughlin, Weissman, & Bitran, 2019) and measures of biological aging, including pubertal timing and cellular aging (Colich, Rosen, Williams, & McLaughlin, 2020).

Accumulating evidence also supports predicted distinctions between dimensions of harshness and unpredictability. For example, unique associations of environmental harshness and unpredictability with numerous life history traits have been observed, including mating and relationship outcomes, parenting, risk-taking, effortful control, and temporal discounting (Belsky et al., 2012; Griskevicius et al., 2013; Simpson, Griskevicius, Kuo, Sung, & Collins, 2012; Sturge-Apple, Davies, Cicchetti, Hentges, & Coe, 2017; Szepsenwol et al., 2017; Szepsenwol, Simpson, Griskevicius, & Raby, 2015; Szepsenwol, Zamir, & Simpson, 2019). Moreover, multiple studies indicate that young adults growing up in more unpredictable environments display enhanced abilities for flexibly switching between tasks or mental sets and for tracking novel environmental information, particularly when in a mindset of stress/uncertainty (Mittal, Griskevicius, Simpson, Sung, & Young, 2015; Young, Griskevicius, Simpson, Waters, & Mittal, 2018). These results underscore the theoretical claim that developmental exposure to harsh and unpredictable environments not only induces tradeoffs with costs to mental and physical health but also enhances skills for solving problems that are ecologically relevant in such environments (Ellis et al., 2020; Ellis, Bianchi, Griskevicius, & Frankenhuis, 2017). The fact that no such effects emerged among individuals who grew up in harsher environments underscores, again, specificity in developmental consequences of different dimensions of adversity.

Smith and Pollak additionally contend that evidence for any developmental effects shared across adversity experiences somehow invalidates dimensional models. One principle central to dimensional models is that different dimensions of experience will influence children in ways that are at least partially distinct (see McLaughlin, 2020; McLaughlin et al., 2014). As such, dimensional frameworks do not make the same claims as specificity models; namely, that different exposures are associated with effects that are completely unique. Regarding them as such is equivalent to debating a straw man.

To make their case, Smith and Pollak highlight studies that show similar associations of threat and deprivation with stress response system functioning—specifically, the autonomic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, as well as hippocampal structure. These arguments are puzzling, as advocates of dimensional models have long made clear that alterations in these stress response systems are at least one common pathway influenced by many forms of adversity (McLaughlin, 2020; McLaughlin, Sheridan, & Lambert, 2014; McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016). Such alterations include both recurring hyperarousal and hypoarousal of stress response systems, which regulate behavior in distinctive way (Del Giudice, Ellis, & Shirtcliff, 2011). Due to well-established deleterious effects of glucocorticoids on hippocampal neurons, any form of adversity that recurrently upregulates the HPA axis is likely to impact hippocampal structure and function. Indeed, this is borne out in a recent systematic review of the literature (McLaughlin et al., 2019). To emphasize, dimensional models do not stipulate that threat and deprivation exert unique effects on stress response systems—or on all developmental mechanisms. Instead, they argue that some developmental pathways are uniquely influenced by particular dimensions of early experience, but not others.

Problem 4: Stress response systems are not the only biological mechanism through which the environment influences development

Smith and Pollak’s final critique of dimensional models is that different types of adverse early environments are not biologically meaningful. In making this claim, they argue that: a) categories of exposure like abuse and neglect are unlikely to map onto biology; b) stress response systems are not responsive to particular types of experiences; and c) children’s interpretation of events may be more important in shaping neurobiology than the actual experiences.

First, dimensional models do not focus on categories of exposure, but rather on core features of the environment that occur to varying degrees in a range of different exposures and experiences. These models assume that these features of the environment will be associated with some pathways that are shared (i.e., disruptions in stress response systems) and some that are unique to particular types of experiences. For example, the idea that the brain responds in specific and unique ways to the presence of threat is uncontroversial. The ability to identify threats in the environment and mobilize defensive responses to them is essential for survival. Decades of animal and human neuroscience research supports the presence of neural circuits, conserved across species, that respond to environmental threats and orchestrate defensive responses (LeDoux, 2003, 2012; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005). A systematic review demonstrates that early-life experiences of threat are consistently associated with changes in the structure and function of these networks (e.g., reduced amygdala volume, elevated amygdala responses to threat cues) (McLaughlin et al., 2019). These findings are consistent with substantial evidence that children who have encountered threatening early environments exhibit heightened perceptual sensitivity to anger, increased accuracy in identifying angry (but not other) facial expressions, and attentional biases to threat cues—all results that have not been observed in children who experience deprivation (Pollak, Messner, Kistler, & Cohn, 2009; Pollak & Sinha, 2002; Pollak & Tolley-Schell, 2003; Pollak, Vardi, Putzer Bechner, & Curtin, 2005).

Central to dimensional models is the claim that the magnitude of these effects should scale with the intensity and duration of exposure to threat, and existing evidence is consistent with that idea (Ganzel, Kim, Gilmore, Tottenham, & Temple, 2013; Machlin et al., 2019; Marusak et al., 2015; McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves, & Sheridan, 2015). Notably, systematic reviews provide no evidence that an absence of cognitive and linguistic stimulation, for example, influences these same, threat-related neural systems (McLaughlin et al., 2019).

Second, Smith and Pollak present a remarkably narrow view of biological mechanisms through which environmental experiences influence development. They argue that “stress response systems are not sensitive to specific types of experience” and we have already made clear that dimensional models do not presume otherwise, though patterns of hyper- versus hypoarousal do have coherent developmental antecedents (Del Giudice et al., 2011). Further, based on their arguments, one might assume that stress response systems are the only route by which adverse environmental experience influences the brain. This is deeply inconsistent with existing evidence on experience-driven plasticity mechanisms that influence neurodevelopment independent of the stress response system.

Experience-driven plasticity involves several well-established biological mechanisms through which environmental experiences exert relatively specific influences on learning and neurodevelopment, including experience-expectant and experience-dependent learning. These concepts are reviewed in depth elsewhere (Gabard-Durnam & McLaughlin, 2020; McLaughlin & Gabard-Durnam, 2020; Nelson & Gabard-Durnam, 2020). Experience-driven plasticity mechanisms produce substantial changes in behavior and neural circuits through myelination and synaptic pruning that eliminates inefficient and unnecessary connections in response to particular types of environmental inputs, some occurring during specific windows of heightened neuroplasticity known as sensitive periods (Fu & Zuo, 2011; Takesian & Hensch, 2013).

Exposure to the specific environmental experiences is required to initiate the plasticity underlying experience-expectant and -dependent learning, and the timing, quality, and intensity of those experiences determines the amount of learning and plasticity that occur (Kolb & Gibb, 2014; Werker & Hensch, 2015). This has been amply demonstrated in animal models (e.g., an absence of light input to the retina shifting organization of primary visual cortex) (Hubel & Wiesel, 1970) and human studies (e.g., language exposure shaping later phonemic perception) (Kuhl, Tsao, & Liu, 2003). Beyond decades of work in animal models, evidence from human cognitive neuroscience demonstrates that specific types of environmental experiences have specific effects on neural circuits. For example, children’s linguistic experiences (measured observationally in their natural environments) are related to the structure and function of circuits specialized for language processing (e.g., activity in Broca’s area during a language processing task, white matter integrity of the arcuate fasciculus) (Romeo, Leonard, et al., 2018; Romeo, Segaran, et al., 2018). This simple example demonstrates clearly the idea of experience-dependent plasticity in the brain that is specific to neural circuits that process particular types of information. This is difficult to reconcile with Smith and Pollak’s argument that “the nature or type of adverse experiences is not directly tied to a specific neurobiological response or outcome” (pg. 10). While such specificity is unimpeachable in the domains of basic sensory and motor processing and language, much remains to be understood in the domain of higher-order cognition (Rosen, Amso, & McLaughlin, 2019; Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2016). Identifying which inputs are of primary importance for shaping association cortex—at which developmental periods—is a task that requires time and careful scientific inquiry. The importance of a robust and well-characterized scientific theory is that empirical studies can evaluate and refine initial predictions. Dismissing the idea that experience-driven learning and plasticity is a mechanism through which adversity influences neural development and focusing entirely on the stress response system will not advance these important scientific goals.

Finally, Smith and Pollak argue that the way a child interprets their experiences may be more important than the objective experience in shaping neurobiology. This idea is interesting and worthy of empirical investigation, although existing data that speak directly to this issue are sparse and suggest that correlations between appraisals and physiology are small in magnitude (Denson, Spanovic, & Miller, 2009; Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2005). In our view, the way a child construes their experiences may be important in shaping some developmental mechanisms, though certainly not all. The experience-driven plasticity mechanisms thought to underlie many developmental consequences of deprivation have little to do with a child’s interpretation of their experiences. An absence of expected inputs from the environment, such as a lack of exposure to linguistic input early in life, does not need to be interpreted by a child as stressful to have lasting effects on neural architecture, learning, and cognitive abilities any more than an absence of visual input has to be appreciated by the child to affect vision. In sum, extensive evidence supports the notion that specific types of environmental experiences are associated with changes in particular brain circuits and that the neurodevelopmental consequences of early-life adversity are not restricted to stress response systems.

Conclusion

It is difficult to understand and measure something as complex and multifactorial as environmental experience. Despite this complexity, we posit that it is not only possible to identify core dimensions of experience and map their associations with developmental outcomes but that the field has already made important headway towards this goal. Because Smith and Pollak mischaracterize dimensional models and evidence related to them in their recent review, we sought the opportunity to “correct the record.” We hope that this exchange has highlighted conceptual and empirical issues that scholars of early-life adversity should be considering. In that sense, Smith and Pollak’s critique has afforded the field a service by stimulating important debate.

Dimensional models identify underlying aspects of early experience that are likely to influence brain and behavioral development; differentiate adaptive and maladaptive responses to adverse childhood experiences; delineate specific—and sometimes unique—mechanisms through which these experiences exert these influences; and provide falsifiable hypotheses that can be tested in empirical studies. Dimensional models are evolving frameworks. As the predictions of these models continue to be evaluated, these models will be refined and updated based on new evidence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Beyond Bounds Creative and Nessa Bryce for their assistance with the design of the figures in this paper.

References

- Ballard ED, Van Eck K, Musci RJ, Hart SR, Storr CL, Breslau N, & Wilcox HC (2015). Latent classes of childhood trauma exposure predict the development of behavioral health outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. Psychological Medicine, 45, 3305–3316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Schlomer GL, & Ellis BJ (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: Distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48, 662–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Estabrook R, Henry D, Grasso DG, Burns J, McCarthy KJ, … Wakschlag LS (2019). Parsing dimensions of family violence exposure in early childhood: Shared and specific contributions to emergent psychopathology and impairment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 87, 100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M, Ellis BJ, & Shirtcliff EA (2011). The Adaptive Calibration Model of stress responsivity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 1562–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison MJ, Rosen ML, Sheridan MA, Sambrook KA, Jenness JL, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Differential associations of distinct forms of childhood adversity with neurobehavioral measures of reward processing: A developmental pathway to depression. Child Development, 90, e96–e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Spanovic M, & Miller N (2009). Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: A meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 823–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Abrams LS, Masten A, Sternberg RJ, Tottenham N, & Frankenhuis WE (2020). Hidden talents in harsh environments. Development and Psychopathology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Bianchi J, Griskevicius V, & Frankenhuis WE (2017). Beyond risk and protective factors: An adaptation-based approach to resilience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 561–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Figueredo AJ, Brumbach BH, & Schlomer GL (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: The impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20, 204–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Kim P (2007). Childhood poverty and health: Cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychological Science, 18, 953–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, & Zuo Y (2011). Experience-dependent structural plasticity in the cortex. Trends in Neurosciences, 34, 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabard-Durnam L, & McLaughlin KA (2020). Sensitive periods in human development: Charting a course for the future.

- Ganzel BL, Kim P, Gilmore H, Tottenham N, & Temple E (2013). Stress and the healthy adolescent brain: evidence for the neural embedding of life events. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 1), 879–889. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetschius LG, Hein TC, McLanahan SS, Brooks-Gunn J, McLoyd VC, Dotterer HD, … Beltz AM (2020). Association of childhood violence exposure with adolescent neural network density. JAMA Network Open, 3, e2017850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius V, Ackerman JM, Cantú SM, Delton AW, Robertson TE, Simpson JA, … Tybur JM (2013). When the economy falters, do people spend or save? Responses to resource scarcity depend on childhood environments. Psychological Science, 24, 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein TC, Geotschius L, McLoyd VC, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S, Mitchell C, … Monk CS (2020). Childhood violence exposure and social deprivation predict adolescent threat and reward neural function. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, & Wiesel TN (1970). The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. The Journal of Physiology, 206, 419–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, & Zeanah CH (2015). Deviations from the expectable environment in early childhood and emerging psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40, 154–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Humphreys KL, & Gotlib IH (2019). The neglect–enrichment continuum: Characterizing variation in early caregiving environments. Developmental Review, 51, 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Querdasi FR, Humphreys KL, & Gotlib I (2020). Dimensions of the language environment in infancy and symptoms of psychopathology in toddlerhood. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/caqez [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, & Gibb R (2014). Searching for principles of brain plasticity and behavior. Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 58, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Tsao FM, & Liu HM (2003). Foreign-language experience in infancy: Effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 9096–9101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert HK, King KM, Monahan KC, & McLaughlin KA (2017). Differential associations of threat and deprivation with emotion regulation and cognitive control in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 929–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE (2003). The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 23, 727–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE (2012). Rethinking the Emotional Brain. Neuron, 73(4), 653–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machlin L, Miller AB, Snyder J, McLaughlin KA, & Sheridan MA (2019). Differential associations of deprivation and threat with cognitive control and fear conditioning in early childhood. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, Article 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusak HA, Furman DJ, Kuruvadi N, Shattuck DW, Joshi SH, Joshi AA, … Thomason ME (2015). Amygdala responses to salient social cues vary with oxytocin receptor genotype in youth. Neuropsychologia, 79, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Piersiak H, Letterie M, & Humphreys KL (2020). Population-based estimates of associations between child maltreatment type: A meta-analysis. PsyArXiv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Levenson RW, McCarter L, Wilhelm FH, & Gross JJ (2005). The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion, 5, 175–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA (2020). Early Life Stress and Psychopathology. In Harkness KL & Hayden EP (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, & Gabard-Durnam L (2020). Experience-driven plasticity and the emergence of psychopathology: A mechanistic framework integrating development and the environment into the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky A, & Kessler RC (2012). Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 1151–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Peverill M, Gold AL, Alves S, & Sheridan MA (2015). Child maltreatment and neural systems underlying emotion regulation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, & Sheridan MA (2016). Beyond cumulative risk: A dimensional approach to childhood adversity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, & Lambert HK (2014). Childhood Adversity and Neural Development: Deprivation and Threat as Distinct Dimensions of Early Experience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, Machlin L, McLaughlin KA, & Sheridan MA (2020). Deprivation and psychopathology in the Fragile Families Study: A 15-year longitudinal investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, Sheridan MA, Hanson JL, McLaughlin KA, Bates JE, Lansford JE, … Dodge KA (2018). Dimensions of deprivation and threat, psychopathology, and potential mediators: A multi-year longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127, 160–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal C, Griskevicius V, Simpson JA, Sung S, & Young ES (2015). Cognitive adaptations to stressful environments: When childhood adversity enhances adult executive function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 604–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, & Gabard-Durnam L (2020). Early adversity and critical periods: Neurodevelopmental consequences of violating the expectable environment. Trends in Neuroscience, 43, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckins MK, Roberts AG, Hein TC, Hyde LW, Mitchell C, Brooks-Gunn J, … Lopez-Duran NL (2020). Violence exposure and social deprivation is associated with cortisol reactivity in urban adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 111, 104426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, & LeDoux JE (2005). Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: From animal models to human behavior. Neuron, 48, 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Messner M, Kistler DJ, & Cohn JF (2009). Development of perceptual expertise in emotion recognition. Cognition, 110, 242–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, & Sinha P (2002). Effects of early experience on children’s recognition of facial displays of emotion. Development and Psychopathology, 38, 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, & Tolley-Schell SA (2003). Selective attention to facial emotion in physically abused children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(3), 323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Vardi S, Putzer Bechner AM, & Curtin JJ (2005). Physically abused children’s regulation of attention in response to hostility. Child Development, 76, 968–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RR, Leonard JA, Robinson ST, West MR, Mackey AP, Rowe ML, & Gabrieli JDE (2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children’s conversational exposure is associated with language-related brain function. Psychological Science, 29, 700–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RR, Segaran J, Leonard JA, Robinson S, West MR, Mackey AP, … Gabrieli JDE (2018). Language exposure relates to structural neural connectivity in childhood. Journal of Neuroscience, 38, 7870–7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ML, Amso D, & McLaughlin KM (2019). The role of the visual association cortex in scaffolding prefrontal cortex development: A novel mechanism linking socioeconomic status and executive function. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 39, 100699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ML, Meltzoff A, Sheridan MA, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Distinct aspects of the early environment contribute to associative memory, cued attention, and memory-guided attention: Implications for academic achievement. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 40, 100731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, & McLaughlin KA (2014). Dimensions of Early Experience and Neural Development: Deprivation and Threat. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18, 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, & McLaughlin KA (2016). Neurobiological models of the impact of adversity on education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, Peverill M, & McLaughlin KA (2017). Dimensions of childhood adversity have distinct associations with neural systems underlying executive functioning. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 1777–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, Shi F, Miller AB, Salhi C, & McLaughlin KA (2020). Network structure reveals clusters of associations between childhood adversities and development outcomes. Developmental Science, 23, e12934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Griskevicius V, Kuo SI-C, Sung S, & Collins WA (2012). Evolution, stress, and sensitive periods: The influence of unpredictability in early versus late childhood on sex and risky behavior. Developmental Psychology, 48, 674–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, & Pollak SD (2020). Rethinking concepts and categories for understanding the neurodevelopmental effects of childhood adversity. Perspectives on Psychological Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Cicchetti D, Hentges RF, & Coe JL (2017). Family instability and children’s effortful control in the context of poverty: Sometimes a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner JA, Colich NL, Uddin M, Armstrong D, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Early experiences of threat, but not deprivation, are associated with accelerated biological aging in children and adolescents. Biological Psychiatry, 85, 268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Fang J, Wan Y, Su P, & Tao F (2020). Association of early-life adversity with measures of accelerated biological aging among children in China. JAMA Network Open, 3, e2013588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szepsenwol O, Griskevicius V, Simpson JA, Young ES, Fleck C, & Jones RE (2017). The effect of predictable early childhood environments on sociosexuality in early adulthood. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Szepsenwol O, Simpson JA, Griskevicius V, & Raby KL (2015). The effect of unpredictable early childhood environments on parenting in adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 1045–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szepsenwol O, Zamir O, & Simpson JA (2019). The effect of early-life harshness and unpredictability on intimate partner violence in adulthood: A life history perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Takesian AE, & Hensch T (2013). Balancing plasticity/stability across brain development. Progress in Brain Research, 207, 3–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, & Hensch TK (2015). Critical periods in speech perception: New directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 173–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, & Suntheimer NM (2019). A dimensional risk approach to assessing early adversity in a national sample. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 62, 270–281. [Google Scholar]

- Young ES, Frankenhuis WE, & Ellis BJ (2020). Theory and measurement of environmental unpredictability. Evolution and Human Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Young ES, Griskevicius V, Simpson JA, Waters TE, & Mittal C (2018). Can an unpredictable childhood environment enhance working memory? Testing the sensitized-specialization hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114, 891–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.