Abstract

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with inv(3)(q21;q26) or t(3;3)(q21;q26), a translocated GATA2 enhancer drives oncogenic expression of EVI1. We generated an EVI1-GFP AML model and applied an unbiased CRISPR/Cas9 enhancer scan to uncover sequence motifs essential for EVI1 transcription. Using this approach, we pinpointed a single regulatory element in the translocated GATA2 enhancer that is critically required for aberrant EVI1 expression. This element contained a DNA binding motif for the transcription factor MYB which specifically occupied this site at the translocated allele and was dispensable for GATA2 expression. MYB knockout as well as peptidomimetic blockade of CBP/p300-dependent MYB functions resulted in downregulation of EVI1 but not of GATA2. Targeting MYB or mutating its DNA-binding motif within the GATA2 enhancer resulted in myeloid differentiation and cell death, suggesting that interference with MYB-driven EVI1 transcription provides a potential entry point for therapy of inv(3)/t(3;3) AMLs.

Keywords: AML, EVI1, MYB, hijacked enhancer, CRISPR/Cas9

Introduction

Next-generation sequencing has greatly improved our knowledge about the location, distribution and frequency of recurrent gene mutations in cancer (1,2). The focus has previously been on the identification and understanding of mutations in protein coding regions. However, many mutations are found in intergenic regions as well (3), which now receive broad attention (4–8). Those studies demonstrate that malignant transformation does not only rely on coding mutations in proto-oncogenes, but may also depend on aberrant regulation of oncogene expression. Well-described mechanisms of aberrant gene activation include generation of novel enhancers by nucleotide substitution, focal amplification of enhancers, loss of boundaries between topologically associated domains (TAD) or enhancer hijacking by chromosomal rearrangements (9–15).

Chromosomal inversion or translocation between 3q21 and 3q26 (inv(3)(q21;q26) or t(3;3)(q21;q26)) in AML result in the aberrant expression of the proto-oncogene EVI1 located at the MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM) at 3q26 (16–19). Our group and others reported that hyper-activation of EVI1 is caused by a GATA2 enhancer translocated from chromosome 3q21 to EVI1 on chromosome 3q26 (12,20). Upon translocation, this hijacked GATA2 enhancer appears to behave as a super-enhancer and is marked by a broad stretch of H3K27 acetylation (12,20). In the current study, we aimed to unravel the mechanism by which the hijacked GATA2 super-enhancer leads to EVI1 activation. We generated a model to study EVI1 regulation in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML cells by inserting a GFP reporter 3’ of endogenous EVI1 and introduced an inducible Cas9 construct. To uncover important elements in this hijacked enhancer, we applied CRISPR/Cas9 scanning and identified motifs essential for driving EVI1 transcription. We demonstrated a single regulatory element in the translocated GATA2 enhancer that is critical for the regulation of EVI1 expression, with an essential role for MYB through binding to the translocated enhancer. Treatment of inv(3)/t(3;3) AML cells with peptidomimetic MYB:CBP/p300 inhibitor decreased EVI1 expression, and induced leukemia cell differentiation and cell death.

Results

Expression of EVI1 in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML is reversible

In inv(3)/t(3;3) AMLs the GATA2 super-enhancer is translocated to MECOM, driving expression of EVI1 (12,20). We investigated whether GATA2 enhancer-driven transcription of EVI1 in inv(3)/t(3;3) is reversible in leukemia cells. In primary inv(3)/t(3;3) AML, immature CD34+CD15− cells can be discriminated from more mature CD34−CD15− and CD34−CD15+ cells (Figure 1A, left and Figure S1A,B, left). Whereas EVI1 is highly expressed in CD34+CD15− cells, mRNA and protein levels decline in the CD34−CD15− fraction and are almost completely lost in CD34−CD15+ cells in inv(3)/t(3;3) primary AML as well as in MUTZ3 cells, an inv(3) AML model (Figure 1A,B, right, Figure 1C, Figure S1A,B, right). Since 3q26 rearrangements are present in all fractions, as determined by three-colored Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) (Figure S1C), we conclude that transcription of EVI1 can be reversed in AML cells despite the presence of a 3q26 rearrangement. In vitro culture of sorted MUTZ3 cells revealed that only the EVI1-expressing CD34+CD15− cells were competent to proliferate (Figure S1D), in agreement with previous observations showing that EVI1 depletion results in loss of colony formation and induction of differentiation (12). Thus, although AML cells with inv(3)/t(3;3) depend on EVI1, transcription of this gene remains subject to regulation and can be repressed, with major consequences for cell proliferation and differentiation.

Figure 1.

Expression of EVI1 in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML is reversible.

A. Flow cytometric analysis of CD34- and CD15-stained inv(3;3) primary AML cells (AML-1) (left) and intracellular EVI1 staining in the gated fractions (right).

B. Flow cytometric analysis of MUTZ3 cells stained with CD34 and CD15 (left) and intracellular EVI1 staining in the gated fractions (right).

C. Bar plot showing relative expression of EVI1 in Transcripts Per Million (TPM) in sorted fractions of MUTZ3 cells. Error bars represent standard deviation of two biological replicates.

Generation of an EVI1-GFP inv(3) AML model

Our findings indicate that interference with EVI1 transcription may be an entry point to specifically target inv(3)/t(3;3) AMLs. To study the molecular mechanisms of EVI1 transcriptional activation by the hijacked GATA2 enhancer, we introduced a GFP reporter 3’ of EVI1 at the translocated allele, which is the only allele expressed in MUTZ3 cells. A T2A self-cleavage site was introduced in between EVI1 and GFP separating the two proteins (Figure 2A, Figures S2A and S2B). Knockdown of EVI1 using two unique EVI1-specific shRNAs (Figure 2B) resulted in a reduction of the GFP signal (Figure 2C). Subsequently, a construct with tight doxycycline (Dox) controlled expression of Cas9 was introduced into MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells (Figure S2C–D) and used to target the translocated GATA2 enhancer and study EVI1 regulation. Deletion of approximately 1000 bp in the −110 kb (−77 kb in mouse) distal GATA2 enhancer (21,22) using two specific sgRNAs (Table S1) resulted in a severe decrease in GFP expression upon Dox treatment (Figure 2D). We sorted the GFP expressing cells into three fractions and observed that enhancer deletion was most pronounced in the GFPlow FACS-sorted cells (Figure 2E lower band). The GFPlow fraction also contained the lowest GFP and EVI1 mRNA levels (Figure 2F–G). Cells from the GFPlow fraction, which showed reduced EVI1 expression, formed less colonies than GFPhigh cells in methylcellulose (Figure 2H). Only colonies obtained from the GFPhigh fraction consisted of cells able to multiply when placed in liquid culture (Figure S2E). Immunophenotyping of the colonies revealed that GFPhigh fractions predominantly consisted of immature CD34+CD15™ cells, while in contrast the GFPlow fraction contained the highest number of differentiated CD15+CD34− cells (Figure S2F). Together, this established a Dox-inducible Cas9 expressing inv(3)/t(3;3) AML model (MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP) for studying the transcriptional control of EVI1 via a GFP reporter.

Figure 2.

Generation of an EVI1-GFP inv(3) AML model.

A. Schematic representation of EVI1-GFP knock-in with a T2A self-cleavage site in the MUTZ3 cells at the endogenous translocated EVI1 locus.

B. Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular EVI1 after shRNA-mediated knockdown of EVI1 using two different shRNAs. The effects on EVI1 protein were measured 48 hours after transduction. Scrambled shRNAs were used as control.

C. Flow cytometric analysis of GFP in the same experiment indicated in (B).

D. Representative flow cytometric plot showing the effect of the −110kb GATA2 enhancer deletion in MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells (Δ enhancer). Cas9 was induced with Dox 24h before nucleofection of two sgRNAs. The effect on EVI1 was measured by GFP levels using flow cytometric analyses. Cells were sorted 48h after nucleofection of subsequent sgRNAs into three fractions: GFPlow, GFPmid and GFPhigh.

E. Genotyping PCR showing a wild type (WT) band (1500 bp) or a band for the enhancer deleted(Δ) (900 bp), either in bulk (before sorting) or in sorted fractions. Control (Ctrl) represents PCR after nucleofection of the sgRNAs without Dox induction.

F. Bar plot showing relative GFP expression of bulk and sorted fractions analyzed by qPCR. The expression levels of PBGD, a housekeeping gene, were used as control for normalization. Relative expression is calculated as fold over Ctrl (nucleofection of the sgRNAs without Dox). Error bars represent standard deviation of two biological replicates.

G. Bar plot showing relative EVI1 expression of MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP bulk and sorted fractions analyzed by qPCR. For details see Figure 2F legend.

H. Bar plot showing the number of colonies grown in methylcellulose from each sorted fraction. Colonies were counted 1.5 weeks after plating. Error bars represent standard deviation of three plates.

Unbiased CRISPR/Cas9 enhancer scan reveals a specific 1 kb region as essential for EVI1 activation

The minimally translocated region of the GATA2 super-enhancer is 18 kb long (12). In MUTZ3 and MOLM1, which are both inv(3) AML models, this highly H3K27 acetylated region (Figure 3A; yellow) contains four loci of open chromatin determined by ATAC-seq (Figure 3A; orange), of which two show strong p300 occupancy (Figure 3A; red). To identify, in an unbiased fashion, which elements of the 18 kb translocated region control EVI1 transcription, we employed a CRISPR/Cas9-based enhancer scanning approach (Figure 3A). We constructed a lentiviral library containing 3239 sgRNAs covering the 18 kb translocated region (Figure 3A, Table S2) and transduced it into MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells at a low multiplicity of infection. After neomycin selection and cell expansion, the cells were treated with Dox to induce Cas9 expression and cells displaying reduced GFP reporter expression (GFPlow) were selected by flow cytometric sorting at day 5 and day 7. The sgRNAs were amplified from genomic DNA and deep-sequenced to identify the sgRNAs that were enriched in the GFPlow fraction. The log2fold change of 3 independent experiments were combined as shown in Figure 3B, which demonstrated a strong correlation between the sgRNAs enriched in GFPlow cells at day 5 and day 7 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Unbiased CRISPR/Cas9 enhancer scan reveals one 1 kb region to be essential for EVI1 activation.

A. ChIP-seq to determine H3K27Ac pattern and p300 binding as well as open chromatin analysis using ATAC-seq in MUTZ3 and MOLM1 cells. The locations of the >3200 sgRNAs targeting the enhancer are indicated as vertical blue lines. A schematic overview of the enhancer scanning strategy is depicted below.

B. Scatter plot of enrichment of sgRNAs in sorted GFPlow fractions at day 5 and day 7 upon Dox induction. The average of three independent experiments for each dot is depicted. For every sgRNA detected in the GFPlow fractions the log2fold change (LFC) of the +Dox relative to –Dox was calculated. Five sgRNAs targeting EVI1 were added to the sgRNA library as positive controls and are indicated in blue. The sgRNAs selected for further validation are indicated in green. The fitted linear regression and corresponding R-squared and p-value are indicated.

C. The LFC enrichment at day 7 of all sgRNAs and of sgRNAs with >2, >3 or >5 fold enrichment of sgRNAs in the GFPlow fractions at the 18 kb region of the GATA2 super-enhancer in MUTZ3 cells is depicted. The H3K27Ac pattern, p300 binding, open chromatin (ATAC) and location of all sgRNAs are indicated to visualize which sgRNAs were enriched in the GFPlow fraction. The −110 kb distal GATA2 enhancer is indicated.

D. Scatter plot showing enrichment of sgRNAs in sorted GFPlow fractions at day 7 compared to %GFPneg cells at day 7 for individually validated sgRNAs (based on two independent biological experiments). The sgRNAs used for validation are indicated by dots. The fitted linear regression and corresponding R-squared and p-value are indicated.

E. Zoom-in of the −110 kb GATA2 enhancer (chr3:128322411-128323124) showing H3K27Ac pattern, p300 binding and open chromatin (ATAC), LFC enrichment of sgRNAs at day 7 and the %GFPneg cells at day 7 of the individually validated sgRNAs. Mutations in motifs for known transcription factors identified in the individually validated sgRNAs are indicated.

Five sgRNAs targeting EVI1 were the top scoring hits in the GFPlow fraction (indicated in blue), whereas sgRNAs targeting the safe harbor AASV1 locus (in red) were not enriched, emphasizing the specificity and sensitivity of the assay (Figure S3A). sgRNAs with a minimum of 3-fold enrichment in the GFPlow fraction all clustered in a small region of approximately 700 bp (Figure 3C). This region is a known p300-interacting region, which belongs to the −110 kb distal GATA2 enhancer (21,22). This p300-interacting region is occupied by a heptad of transcription factors (SCL, LYL1, LMO2, GATA2, RUNX1, FLI1 and ERG) that regulate gene expression in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) (23,24) (Figure S3B). Approximately 40 sgRNAs within this region, with at least a 2-fold enrichment in the GFPlow fraction, were selected and cloned into a lentiviral construct with iRFP720 for individual testing. The loss of GFP signal at day 7 in the iRFP+ fraction (gating strategy, see figure S3C) highly correlated with the enrichment of those 40 sgRNAs in the GFPlow fraction as observed in the enhancer scan (Figure 3D). An efficiently cutting sgRNA that was not enriched in the enhancer scan did not affect GFP signal upon Dox exposure (Figure S3D,E). Deep amplicon sequencing of the −110 kb enhancer region upon targeting by 36 individual sgRNAs revealed frequent mutations in motifs for MYB, GATA, RUNX-, MEIS-, XBP- and ETS- binding sites, which were among the highest conserved (Figure 3E, Figure S3F, Table S3).

A MYB binding motif is essential for EVI1 rather than for GATA2 transcription

Four sgRNAs, i.e. # 3, 8, 11 and 16, generating the highest GFPneg (EVI1neg) fraction in the single guide validation experiments, all targeted the same region containing a potential MYB-binding motif (Figure 4A). The strong reduction of GFP expression, as tested for three of those guides (Figure 4B), was accompanied by loss of EVI1 protein (Figure 4C) and mRNA (Figure 4D). EVI1 loss was accompanied by differentiation into CD34−CD15+ cells in the sgRNA8-targeted GFPlow fraction (Figure 4E), in line with the findings in primary AML cells (Figure 1A,B, left and Figure S1A,B, left). Strikingly, sgRNA8-directed mutations within the enhancer did not affect GATA2 protein (Figure 4C) or mRNA levels (Figure 4D). Western blot analysis on sorted fractions of sgRNA8-treated cells revealed a strong reduction of EVI1 but not of GATA2 in GFPlow cells (Figure 4F). Amplicon-seq within the GFPlow sorted fraction of sgRNA8-treated cells revealed that almost 97% of the aligned sequences, including the translocated and non-translocated allele, were mutated (Figure 4G). In approximately 86% of all aligned sequences, the MYB motif was mutated. In 14%, a 20 bp deletion fully eliminated the predicted MYB DNA-binding motif (Figure 4H). We carried out pulldown experiments in which equal amounts of MUTZ3 nuclear lysates (Figure S4A) were exposed to beads with immobilized 100 bp enhancer DNA fragments representing WT or MYB-motif mutant enhancer DNA, as defined in Figure 4H. Western Blot analysis confirmed MYB binding to the 100 bp WT enhancer fragment (Figure 4I). MYB binding to the M1 or M2 mutants was severely reduced, but it was preserved in the M3 mutant, in which the MYB DNA-binding motif was retained (Figure 4I). We conclude that in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML transcription of EVI1 depends on the presence of a MYB DNA-binding motif in the translocated enhancer. Strikingly, this MYB motif appears less relevant for the transcription of GATA2 in the non-translocated allele.

Figure 4.

A MYB binding motif is essential for EVI1 rather than for GATA2 transcription.

A. Nucleotide sequence of the region targeted by sgRNAs 3,8,11 and 16, as well as other nearby sgRNAs, with the corresponding MYB DNA binding motif highlighted in purple. Colors of sgRNAs represent differences in percentage of recovery in the GFPneg fraction. sgRNAs indicated in red are the most highly enriched in the GFPneg fraction.

B. Flow cytometric analysis of MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells upon sgRNA treatment. GFP signal shifts are shown upon transduction with lentivirus containing sgRNAs 3, 8, 11 or an EVI1-specific sgRNA. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 7 days after induction of Cas9.

C. Western blot using EVI1- and GATA2-specific antibodies upon transduction with lentivirus containing sgRNAs 3, 8, 11 or an EVI1 specific sgRNA (EVI1.4) analyzed 7 days after induction of Cas9. Actin was used as loading control.

D. Bar plot showing relative expression of EVI1 and GATA2 in transcripts per million (TPM) in MUTZ3-EVI-GFP cells treated with sgRNAs 3, 8 or 11, −Dox or +Dox. The cells treated with sgRNAs 3, 8, or 11 were considered replicates and standard deviation is shown.

E. CD34/CD15 flow cytometric analyses of MUTZ3 EVI1-GFP cells transduced with sgRNA8 (+Dox), sorted for GFPlow or GFPhigh and analyzed two weeks after sorting.

F. EVI1 and GATA2 western blot upon treatment with sgRNA 8, sorted into GFPlow or GFPhigh fractions, 7 days after induction of Cas9. Actin was used as loading control.

G. Editing frequency in the GFPlow fraction of sgRNA8-treated cells. Modified reads exhibited variations with respect to the reference human sequence. The percentages of reads that align to each allele were determined based on a heterozygous SNP in the sequenced region.

H. Visualization of the distribution of mutations identified around the sgRNA8 target site in the GFPlow sorted fraction. The sgRNA8 target site is indicated (GGGGGCAAGTAACGGATGC) as well as the MYB binding motif (black rectangle).

I. Western blot using anti-MYB antibody in MUTZ3 cell lysates following pulldowns using WT, mutated M1, M2 or M3 100bp DNA fragments.

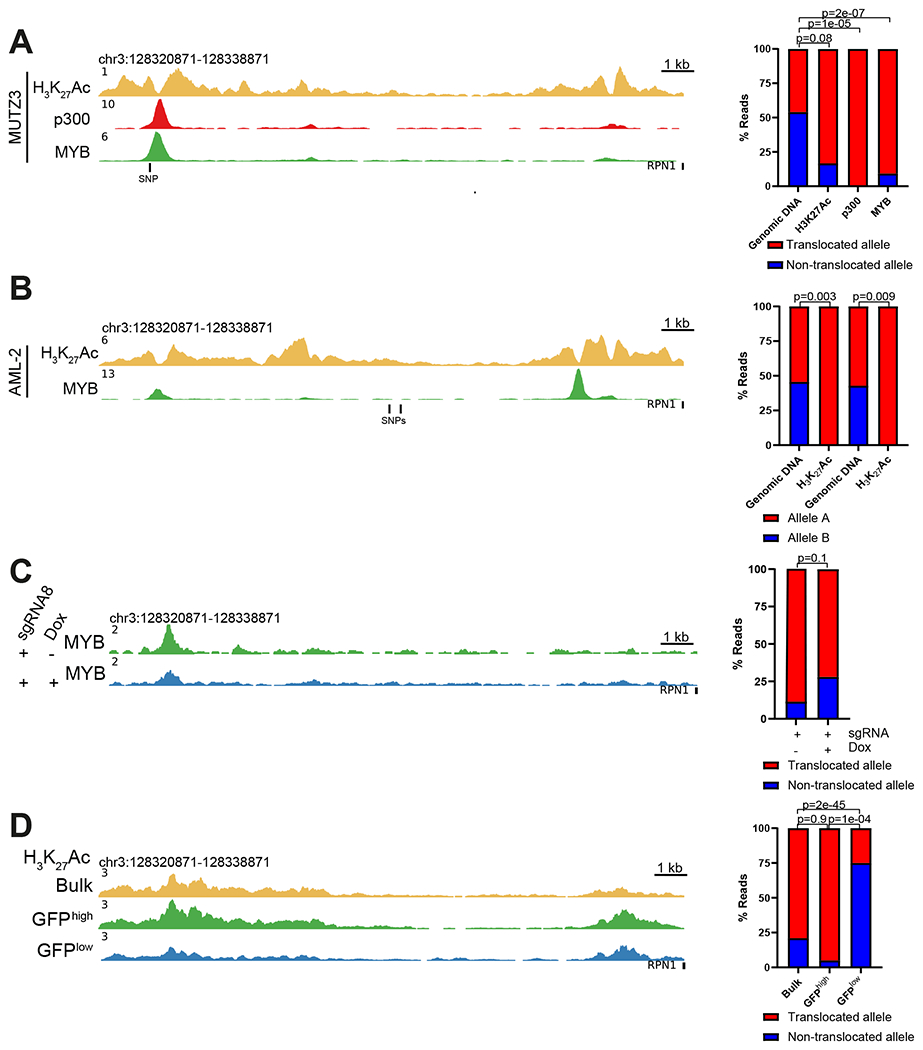

Differential MYB binding and H3K27 acetylation at the hijacked GATA2 enhancer

ChIP-seq revealed MYB occupancy at the −110 kb GATA2 enhancer in MUTZ3 and in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML patient cells (Figure 5A,B, green tracks). MYB also occupied the −110 kb GATA2 enhancer in CD34+ cells (Figure S4B, green track). Based on a heterozygous SNP in the −110 kb GATA2 enhancer in MUTZ3, the translocated allele (EVI1) can be discriminated from the non-translocated (GATA2) allele (12). We found approximately 7 times more MYB occupancy at the translocated allele (Figure 5A, right), in agreement with the finding that p300 occupancy (Figure 5A, red track) was also detected predominantly at the translocated enhancer (Figure 5A, right). Furthermore, H3K27Ac signal (Figure 5A, right) and open chromatin (ATAC) (Figure S4C) were 5 times more prevalent at the translocated enhancer. No SNPs were present in primary AMLs to discriminate MYB binding to the different alleles. However, based on two SNPs in the 18 kb region (Figure 5B, left), we observed a strong H3K27Ac allelic skewing of the primary inv(3)/t(3;3) AML, predicted to be biased to the translocated allele (Figure 5B, right). These data suggest that MYB and p300 interact with the −110 kb enhancer preferentially at the translocated allele. In sgRNA8-treated MUTZ3 cells (+Dox) MYB binding to the −110 kb site was significantly decreased compared to control (−Dox) cells (Figure 5C). This loss was GATA2 enhancer-specific, since genome-wide MYB chromatin occupancy, which includes the MYB target gene BCL2, did not change in +Dox cells (Figure S4D and S4E). Importantly, the decrease of MYB-binding at the −110 kb enhancer upon sgRNA8 treatment was greater within the translocated allele (Figure 5C, right). Using Cut&Run we demonstrated that H3K27Ac was severely decreased at the enhancer in GFPlow sorted cells (Figure 5D, blue track) compared to GFPhigh sorted cells (Figure 5D, green track) following sgRNA8 treatment. Moreover, SNP analysis revealed that the remaining H3K27Ac at the enhancer in GFPlow cells occurred predominantly at the non-translocated allele (GATA2) (Figure 5D, right). These data demonstrate that mutating the MYB binding motif at the translocated −110 kb enhancer decreases MYB binding, thus inactivating the enhancer and reducing EVI1 transcription.

Figure 5.

Differential MYB binding and H3K27 acetylation at the hijacked GATA2 enhancer.

A. H3K27Ac, p300 and MYB ChIP-seq profiles of the 18 kb super-enhancer region in MUTZ3 cells (left). Bar plot showing allelic bias towards the translocated allele for H3K27Ac, p300 and MYB occupancy by ChIP-seq analysis based on a SNP (rs553101013) (right). Previous sequencing showed that G represents the translocated allele and A the wild type allele (12). P-values were calculated using a χ2 test.

B. H3K27Ac and MYB ChIP-seq profiles of the 18 kb super-enhancer in an AML patient with inv(3) (AML-2) (left). Bar plot showing discrimination between H3K27Ac at the two GATA2 enhancer alleles based on two SNPs (rs2253125 and rs2253144) (right). P-values were calculated using a χ2 test.

C. MYB ChIP-seq profile of the 18 kb super-enhancer in sgRNA8-treated MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells plus or minus Dox treatment (left). Bar plot showing allelic distribution of MYB binding in sgRNA8 treated MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells plus or minus Dox treatment (right). P-values were calculated using a χ2 test.

D. H3K27Ac profile of the 18 kb super-enhancer in sgRNA8-treated MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells, determined by Cut&Run in bulk, in GFPhigh and in GFPlow sorted fractions (left). Bar plot showing allelic bias for H3K27Ac in the bulk, GFPhigh and GFPlow fractions (right). P-values were calculated using a χ2 test.

MYB interference downregulates EVI1 but not GATA2

MYB is expressed in MUTZ3 cells, regardless of their differentiation status (Figure S4F). To study whether MYB is important for EVI1 expression, MYB-specific sgRNAs were introduced into MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP cells. At day 3 and 6 post-Dox induction, loss of MYB expression was evident, which was accompanied by a decrease of EVI1 protein (Figure 6A). In contrast, in line with the effects of mutating the MYB binding motif, knockout of MYB did not decrease GATA2 protein expression (Figure 6A). This suggests that MYB is not functioning upstream of GATA2 via this motif in inv(3) cells. When we either knocked out MYB or mutated the MYB DNA-binding motif with sgRNAs in K562 cells (Figure S4G), a model without a 3q26 rearrangement, we also did not see an effect on GATA2 protein levels (Figure S4H).

Figure 6.

MYB interference downregulates EVI1 but not GATA2.

A. Western blot for MYB, EVI1 and GATA2 in MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP upon sgRNA-mediated MYB knockout (MYB.30) at indicated days after induction of Cas9. Actin was used as loading control.

B. Western blot for MYB, EVI1 and GATA2 in untreated cells (−) or cells treated for two days with 20 μM of TG3 or MYBMIM (MM). Actin was used as loading control.

C. Colony forming units (CFU) of MUTZ3 cells cultured without peptide or treated with 20 μM TG3 or MYBMIM for two days and subsequently plated in methylcellulose. Error bars show standard deviation across three plates. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA test.

D. Flow cytometric analysis of MUTZ3 cells stained with CD34 and CD15. Cells studied by flow cytometry were either untreated or treated with 20 μM TG3 or MYBMIM for two days and subsequently grown for nine days in methylcellulose.

E. Colony forming units (CFU) of MUTZ3 cells with pMY-FLAG-Evi1-IRES-GFP (Evi1) or empty vector (EV) cultured without peptide or treated with 20 μM MYBMIM for two days and subsequently plated in methylcellulose. Error bars show standard deviation across three plates. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA test.

F. Flow cytometric analysis of MUTZ3 cells with Evi1 or EV, stained with CD34 and CD15. Cells studied by flow cytometry were either untreated or treated with 20 μM MYBMIM for two days and subsequently grown for eight days in methylcellulose.

G. p300 and MYB ChIP-seq profiles of the 18 kb region in MUTZ3 cells treated with either 20 μM TG3 or MYBMIM for 48 h.

H. Cell-viability test of inv(3)/t(3;3) AML primary cells determined by CellTiter-Glo three days after culturing the cells in a 96-well plate with 20 μM TG3 or MYBMIM. Error bars show standard deviation across four biological replicates. P-values were calculated using a one-way ANOVA test.

I. Western blot for MYB, EVI1 and GATA2 in untreated AML cells or in AML cells treated with 20 μM TG3 or MYBMIM for 48h. Actin was used as loading control.

J. Western blot for MYB, EVI1 and GATA2 in cultured CD34+ cells untreated or treated with 20 μM TG3 or MYBMIM for 48h. Actin was used as loading control.

The activity of MYB can be repressed using the peptidomimetic inhibitor MYBMIM, which impairs the assembly of the MYB:CBP/p300 complex (25). In MUTZ3 cells, treatment with 25 μM MYBMIM caused a 50% reduction of viable cells, whereas the inactive MYBMIM analog TG3 showed no effect (Figure S4I). Treatment of MUTZ3 cells with 20 μM MYBMIM strongly reduced EVI1 protein levels (Figure 6B) without impacting MYB levels (Figure 6B). Consistent with the MYB knockout experiment (Figure 6A), MYBMIM treatment did not alter GATA2 protein levels (Figure 6B). A two-day exposure of MUTZ3 cells to MYBMIM reduced the number of colonies in methylcellulose (Figure 6C). Flow cytometric analysis of MYBMIM-treated colony cells revealed increased maturation (CD34−CD15+ cells) in comparison with TG3-treated controls (Figure 6D). We next introduced a FLAG-Evi1 retroviral construct (26) allowing for constitutive murine Evi1 expression in MUTZ3 cells (Figure S4J). Loss of colony formation upon MYBMIM treatment was partly rescued by Evi1 overexpression (Figure 6E). Similarly, the mild effect of MYBMIM on differentiation of MUTZ3 cells (Figure 6F, MYBMIM-EV) was reduced (Figure 6F, MYBMIM-Evi1). This indicates that the effect of MYB interference on MUTZ3 cells is at least partly mediated via EVI1. Moreover, whereas MYBMIM treatment did not reduce MYB protein, it decreased MYB occupancy at the GATA2 enhancer (Figure 6G). p300 occupancy also decreased, but to a lesser extent than MYB (Figure 6G). MYB binding was reduced at several sites, including the BCL2 enhancer (Figure S4K). MYBMIM, but not TG3, reduced viability of inv(3)/t(3;3) AML patient cells (n=3) (Figure 6H), and treatment of AML primary cells with MYBMIM reduced EVI1 protein levels without affecting levels of MYB or GATA2 (Figure 6I). Finally, MYBMIM affected neither GATA2 nor EVI1 levels in normal CD34+ cells (Figure 6J), suggesting that MYB has no effect on the GATA2 enhancer or on EV1 in normal HSPCs. In contrast to MUTZ3 cells, MYBMIM did not reduce the number of CD34+ colonies in methylcellulose (Figure S4L). Thus, targeting MYB represents a promising therapeutic possibility in the context of inv(3)/t(3;3) AMLs with EVI1 overexpression.

Discussion

Although multiple examples of hijacked enhancers causing uncontrolled expression of proto-oncogenes have been reported in various types of cancer (8,10,12,27,28), insight into their altered biological function remains limited. Elucidating these functions could provide opportunities for tailored interference and tools for therapeutic exploitation. Our unbiased CRISPR/Cas9 scan of the translocated 18 kb region in inv(3)/t(3;3) AMLs revealed a single region of approximately 1 kb essential for EVI1 activation and leukemogenesis. This distal GATA2 enhancer contained several conserved transcription factor DNA binding motifs, including an element preferentially occupied by MYB at the translocated allele (Figure 7, top). Strikingly, mutating this MYB binding motif in the enhancer at both alleles strongly decreased the expression of EVI1, but not of GATA2. GATA2 was also not affected in another leukemia line or in normal HSPCs. Together, these findings support a unique role for MYB in driving EVI1 expression via the translocated enhancer, and suggest a potential vulnerability in inv(3)/t(3;3) AMLs. Indeed, peptidomimetic inhibition of MYB:CBP/p300 assembly in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML cells reduced EVI1 but not GATA2 protein levels, causing myeloid differentiation and cell death (Figure 7, bottom). This strengthens the hypothesis that interfering with EVI1 expression via MYB may constitute a new entry point for targeting these AMLs. The fact that targeting MYB specifically compromises EVI1 expression compared to GATA2 points to the possibility of selectively targeting leukemia cells while sparing GATA2 in normal HSPCs (Figure 6J), in which GATA2 is a vital regulator.

Figure 7.

Mechanism by which MYB drives oncogene activation in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML. A CRISPR/Cas9 scan of the GATA2 translocated enhancer pinpointed a single regulatory element containing a MYB-binding motif critical for EVI1 expression (top). MYB preferentially occupies the translocated enhancer driving EVI1 expression. Inference with MYB downregulates EVI1 but not GATA2 levels (bottom).

Although MYB encodes a transcription factor essential for normal hematopoiesis (29), there is also overwhelming evidence that it plays a critical role in malignant transformation. MYB was first discovered as an oncogene (v-myb) within the avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) genome which generated myeloid leukemias in chickens (30,31). Its critical involvement in super-enhancer activity was previously shown in human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (9,32). Mutations in non-coding regions near TAL1 or LMO2 create de novo binding sites for MYB, leading to the formation of new MYB-bound super-enhancers which drive uncontrolled transcription of those target genes. Furthermore, MYB binds to a translocated super-enhancer driving MYB expression in adenoid cystic carcinoma, creating a positive feedback loop sustaining its own expression (28). MYB is also frequently overexpressed in human myeloid leukemias (33,34) and AML cells can be addicted to high levels of MYB and thus be more vulnerable to MYB inhibition than normal hematopoietic progenitor cells (35). However, the mechanisms whereby MYB drives transformation to AML are not fully understood. To our knowledge, our results in this study represent the first example of a mechanism by which MYB drives oncogene activation in AML (Figure 7).

MYB occupies the translocated GATA2 enhancer at a level considerably higher than the non-translocated enhancer. This may reflect increased chromatin accessibility as determined by H3K27Ac ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq. The mechanisms driving this open chromatin pattern at the translocated locus remain a focus of future studies. However, translocation of the enhancer to a new location places it in proximity to distinct promoters and regulatory elements which may ultimately impact chromatin accessibility and MYB binding. In support of this hypothesis, mutating the MYB DNA binding site or interference with MYB function causes reduced expression of EVI1 but not GATA2.

The coactivators CBP and p300 are major mediators of MYB transcriptional activity (36,37). Therefore, specifically targeting the MYB:CBP/p300 interaction has been the focus of most small molecules seeking to inhibit MYB activity (25,38–41). Experiments using the peptidomimetic inhibitor MYBMIM, which blocks the formation of MYB:CBP/p300 complex, showed a severe loss of EVI1 activity. As reported by Ramaswamy et. al., (25), we also observed that MYBMIM caused loss of MYB binding to the enhancer, with largely preserved total cellular levels of MYB. Concurrently, we observed that MYBMIM treatment did not inhibit p300 occupancy at the enhancer to the same extent as MYB occupancy. This partially retained p300 binding could be explained by the presence of other transcription factors bound at the GATA2 enhancer that also recruit CBP/p300 (Figure S3B). MYBMIM reduced MYB binding at multiple sites which may be relevant in other leukemias in which MYB is essential (33–35). Therefore, it is not surprising that other AML cell lines (25,42) respond to MYBMIM as well. While initial results with MYBMIM peptide treatment of inv(3)/t(3;3) AML cells are a promising proof of concept, MYBMIM peptide is very unstable in vivo (personal communication A.K.). Thus, development of small molecules with improved bioavailability that interfere with MYB:CBP/p300 complex will be required to investigate the relevance of MYB inhibition in vivo.

Our CRISPR/Cas9 scan identified one p300-interacting region containing a MYB DNA binding motif to be important for EVI1 expression. Although mutations in the MYB DNA-binding motif had the biggest impact on EVI1 expression, other mutations also reduced EVI1 levels. These included mutations in consensus DNA binding sites for GATA-, RUNX-, MEIS-, XBP- and ETS-factors. Interestingly, some of these factors have been demonstrated to occupy the −110 kb enhancer in CD34+ cells, including RUNX1, ERG and GATA2 (24). MYB binding and activity at the −110 kb GATA2 enhancer most likely occur in conjunction with p300 as well as transcription factors like RUNX1 and ERG. This is in accordance with other studies showing co-localization and potential cooperation between these factors and MYB (25,43,44). Therefore, combinatorial targeting of MYB and other transcription factors may synergistically impact EVI1 expression. This knowledge provides a rationale to develop new compounds to treat inv(3)/t(3;3) AML, which can be tested in our newly developed model.

Our findings provide important insight into the mechanisms of oncogenic enhancer-driven gene activation in AML. The selective MYB motif requirement for enhancer function at the translocated but not the normal allele constitutes a novel paradigm in which chromosomal aberrations reveal critical motifs that are non-functional at their endogenous locus. In principle, this paradigm may be extrapolated to other enhancer-driven cancers and even non-malignant pathologies.

Methods

Data and Code Availability

Cell line sequence data generated in this study have been deposited at the EMBL-EBI ArrayExpress database (ArrayExpress, RRID:SCR_002964) under accession numbers E-MTAB-9939 (RNA-seq), E-MTAB-9949 (ATAC-seq), E-MTAB-9946 (Cut&Run-seq), E-MTAB-9945 (Amplicon-seq), E-MTAB-9948 (CRISPR enhancer scan) and E-MTAB-9959 (ChIP-seq). ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data derived from donors or patients have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (The European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), RRID:SCR_004944) under the accession number EGAS00001004839. This study did not generate any unique codes. All software tools used in this study are freely or commercially available.

Cell culture

The MUTZ3 cell lines (DSMZ Cat# ACC-295, RRID:CVCL_1433) were cultured in αMEM (HyClone) with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 20% conditioned 5637 medium. The 293T (DSMZ Cat# ACC-635, RRID:CVCL_0063) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% FCS. K562 (DSMZ Cat# ACC-10, RRID:CVCL_0004) was cultured in RPMI (Gibco) with 10% FCS. All cell lines were supplemented with 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Viable frozen AML cells and viable (frozen) bone marrow or cord blood CD34+ cells were thawed and suspended in IMDM medium supplemented with: 20% BIT medium (StemCell Technologies), 1x β-mercaptoethanol (1000x Life technologies), 6 μg/ml LDL (Sigma Aldrich), human IL6, IL3, G-CSF, GM-CSF at 20 ng/ml and FLT3, SCF at 50 ng/ml (Peprotech). Cell lines were obtained from DSMZ and regularly confirmed to be mycoplasma-free by the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, #LT07-318) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of model lines

The repair template was generated using Gibson Assembly (NEB). Both homology arms were PCR amplified from MUTZ3 genomic DNA using Q5 polymerase (NEB). The first homology arm consists of a part of the intron and last exon of EVI1 minus the STOP codon. The second homology arm consists of part of the 3’UTR with the PAM sequence of sgRNA omitted. The T2A-eGFP was PCR amplified from dCAS9-VP64_2A_GFP (RRID:Addgene_61422). All fragments were cloned using Gibson assembly into the PUC19 (Invitrogen) backbone. sgRNA sequence AGCCACGTATGACGTTATCA was cloned into pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9. Cells were nucleofected with pX330 vector (RRID:Addgene_42230) containing the sgRNA and Cas9 and the repair template using the Nucleofector 4D (Lonza) with Kit SF and program DN-100. GFP+ cells were sorted using a FACS AriaIII (BD Biosciences). In a second sorting round, GFP+ cells were single cell sorted and tested for proper integration. Clone 1A5 was transduced with lenti pCW-Cas9 (RRID:Addgene_50661), puromycin selected (1 μg ml−1) and subsequently single cell sorted based on GFP positivity and tested for inducible Cas9 expression. Clone 3E7 was used for the screen, which we called MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP.

Patient material

Samples of the selected patients presenting with AML were collected from the Erasmus MC Hematology Department biobank (Rotterdam, the Netherlands). The karyotype of AML patients used in this study was as follows; AML-1: 45,XX,inv(3)(q2?1q26),-7, AML-2: 45,XY,inv(3)(q22q26),-7 and AML-3: 45,XX,t(3;3)(q21;q26),-7. Leukemic blast cells were purified from bone marrow or blood by standard diagnostic procedures. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus MC has approved usage of the patient rest material for this study.

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCL, 138 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1% Triton, 10% glycerol, 2 mM NA-vanadate) containing Complete protease inhibitors (CPI, Roche #4693159001). Protein levels were detected using antibodies against EVI1 (Cell Signaling, Cat# 2265, RRID:AB_561424), MYB (Millipore Cat# 05-175, RRID:AB_2148022), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# F3165, RRID:AB_259529), B-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# A5441, RRID:AB_476744), GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-25778, RRID:AB_10167668), CAS9 (Biolegend Cat# 844301, RRID:AB_2565570) or GATA2 (kind gift of E.H. Bresnick, Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology, Madison, WI). Proteins were visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor).

Flow cytometric analysis

Cell Sorting was performed using the FACS Aria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, RRID:SCR_013311) into a 96-well plate format or into batch culture. Flow Cytometric analysis on MUTZ3 cells was done with GFP/RFP or antibody stainings for CD34-PE-CY7 (BD Biosciences Cat# 348811, RRID:AB_2868855) and CD15-APC (Sony, #2215035) or CD15-BV510 (BioLegend Cat# 323028, RRID:AB_2563400). Intracellular stainings with EVI1 (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2256, RRID:AB_561017) or Rabbit (DA1E) mAb IgG XP® Isotype Control (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 3900, RRID:AB_1550038) were performed using Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (00-5523-00, eBioscience). Cells were measured on a BD Canto or BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data was analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, RRID:SCR_008520).

DNA pulldown

Nuclear lysates for pulldown experiments were prepared as described (45). Oligo nucleotides for affinity purification were ordered as custom-synthesized oligos from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) (see Table S4). DNA pulldown was performed as described by Karemaker and Vermeulen with minor changes. Essentially, per DNA pulldown, 500 pmole of annealed oligos were diluted to 600 μL in DNA binding buffer (DBB: 1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% NP40) and incubated with washed beads (10 uL Streptavidin Sepharose High performance bead slurry (GE Healthcare #17511301), washed once with PBS + 0.1% NP-40 and once with DBB) for 30 minutes at 4°C while rotating. After washing once with 1mL DBB and twice with 1 mL protein incubation buffer (PIB: 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.25% NP40, 1 mM DTT with Complete protease inhibitors (CPI, Roche #4693159001)) the immobilized oligos on beads were combined with 500 μg nuclear extracts in a total volume of 600 μL PIB with 10 μg competitor DNA (5 μg poly-dldC (Sigma #81349_500ug) and 5 μg poly-dAdt (Sigma #P0883_50UN)) and incubated for 90 minutes at 4°C while rotating. Beads were washed three times with 1mL PIB and twice with 1 mL PBS. To elute proteins from the oligo probes, beads were resuspended in 20 uL 1x western blot protein sample buffer and incubated at 95°C for 15 minutes while shaking. The beads were spun down and the eluate was loaded on a protein gel. A 40 μg nuclear extract sample was prepared directly from the nuclear lysate as input sample for western blot.

Peptide treatment of cells

MUTZ3, primary AMLs or CD34+ cells were cultured in medium as described above, plus MYBMIM or control peptide TG3 at indicated concentrations. For measuring viability of MUTZ3 or primary AMLs, cells were seeded in an opaque colored 96-well plate at 15.000 cells/well in a total volume of 100 μl medium containing MYBMIM or control peptide TG3 at indicated concentrations (20 μM MYBMIM or control peptide TG3 for primary AMLs). Cell viability was assessed 72 hours after treatment using CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay according to manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Luminescence was measured on the Victor X3 plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Rescue experiments in MUTZ3 cells were performed by retroviral overexpression of murine pMY-FLAG-Evi1-IRES-GFP or an empty vector (EV) control. The pMY vectors were kind gifts of T. Sato (26) in which FLAG was inserted 5’ of Evi1. Evi1 or EV overexpressing cells were cultured in the presence of 20 μM MYBMIM for 48 hours. For colony cultures following peptide treatment, 2000 MUTZ3 cells or 500 CD34+ cells were plated in MethoCult (StemCell technologies) with 100U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. For protein lysates and ChIP experiments cells were cultured containing 20 μM MYBMIM or control peptide TG3 and harvested after 48 hours of peptide treatment.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was performed and reported according to standard protocols based on the International System of Human Cytogenetics Nomenclature (2016) (46). MECOM FISH was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the MECOM t(3;3); inv(3)(3q26) triple-color probe (Cytocell, LPH-036).

Genome editing

The sgRNAs (Table S1) were either cloned into pLentiV2_U6-IT-mPgk-iRFP720 (J.Z.) using BsmBI restriction sites, px330 using BbsI or were in vitro transcribed using the T7 promoter. Lentiviruses were prepared by transfecting 293T cells with lentiviral packaging constructs pSPAX2/pMdelta2.G and sgRNA cloned into pLentiV2_U6-IT-mPgk-iRFP720. Transfections were performed using Fugene 6 (Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For in vitro transcribed sgRNAs oligo’s containing the T7 promoter, target sequence and the Tail annealing sequence were annealed, filled in and transcribed using the Hi-scribe T7 kit (NEB). Turbo DNAse (Invitrogen) was added and sgRNAs were cleaned up using RNA clean&concentrator kit (Zymo). Concentration of sgRNAs was estimated using Qubit (Invitrogen). RNP complexes were formed incubating sgRNA and Cas9 (IDT) for 20-30 at RT before nucleofection using the Neon (Thermofischer) with buffer R with settings 1500V, 20ms, 1 pulse for MUZT3 or 1350V, 10ms, 4 pulses for K562. Genomic DNA was extracted at indicated timepoint after transfection using Quick Extract buffer (Epicenter) PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen) and checked for targeting by PCR using Q5 polymerase (NEB) or amplicon-sequencing.

Pooled sgRNA Enhancer scanning

To design a high-resolution sgRNA library for the enhancer scan, we considered all possible sgRNA target sites containing a canonical Cas9 PAM site (NGG) on both strands of the minimal 18 kb translocated region. sgRNAs containing a G in positions 1-3 of the 20nt target site were trimmed at this position to favor 20-, 19- or 18-mers (in this order of priority) containing a natural G at the 5’end as previously described (47). For all other sgRNAs, a G was added to the 5’end (resulting in a 21-mer). Subsequently, all sgRNAs showing (1) a high number of target sites in the human genome (>5 with no mismatch, or >20 with 1 mismatch), (2) a BsmBI site (interfering with cloning), or (3) a polyA signal (interfering with packaging) were filtered out. In addition, we added a number of negative controls (82 sgRNAs targeting the AAVS1 region) as well as positive controls (5 sgRNAs targeting EVI1 as well as 313 sgRNAs covering 5 kb of the breakpoint in MUTZ3 cells). The final library of 3239 sgRNAs (Table S2) was synthesized with overhangs for PCR amplification and cloning as one oligo pool (Twist Bioscience) and cloned into the lentiviral vector sgETN (J.Z.) as previously described (47). The pool of 3239 sgETN-sgRNAs was transduced in triplicate into MUTZ3-EVI1-GFP. For each replicate, a total of 120 million cells were infected with 3-4% transduction efficiency to ensure that each sgRNA is represented predominantly as a single lentiviral integration in >1000 cells. After neomycin drug selection (1 mg ml−1) for 7 days, T0 samples were obtained (5 million cells per replicate), and cells were subsequently cultured in the presence of 1 μg ml−1 doxycycline (Dox). Culture medium was exchanged every 2 days. After 5 days (T5) and 7 days (T7), about 1 million sgRNA-expressing (GFPlow) cells were sorted for each replicate using a FACS AriaII (BD Biosciences). Genomic DNA from T0, T5 and T7 samples was isolated by two rounds of phenol extraction using PhaseLock tubes (5PRIME), followed by isopropanol precipitation. Deep-sequencing libraries were generated by PCR amplification of sgRNA guide strands using primers that tag the product with standard Illumina adapters and a 4 bp sample barcode in a 2 step-PCR protocol. For each sorted sample, all DNA was used as template in multiple parallel 50-μl PCR reactions, each containing 250-500 ng template, 1x AmpliTaq Gold buffer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.3 μM of each primer and 1U AmpliTaq Gold (Invitrogen), which were run using the following cycling parameters: 95 °C for 10 min; 28 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products (367 bp) were combined for each sample and Ampure purified. For the T0 samples and a DNA-pool sample the amount of input DNA necessary to get a 1000x coverage was used as input in the PCRs. For the second PCR 10ng of input was used per PCR using the following cycling parameters: 95 °C for 10 min; 8 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products (448 bp) were combined for each sample and Ampure-purified. Libraries were sequenced equimolarly on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina) by the Next Generation Sequencing Facility at Vienna BioCenter Core Facilities (VBCF), member of the Vienna BioCenter (VBC), Austria. Multiple experiments (different time points and sorted fractions) were sequenced simultaneously, each identified by a unique barcode. Sequencing data were processed by converting unaligned BAM files into FASTA using bam2fastx. Experiment-specific barcodes (positions 7-10) were extracted together with the sgRNA sequence (positions 31-) into a new FASTA file, which was subsequently reverse-complemented with seqtk seq. Next, the barcodes were used to demultiplex the FASTA file into experiment-specific files with ngs-tools split-by-barcode, using parameters −s 4 −d 1, i.e. barcode size 4 and maximum 1 mismatch. For each of these files, we counted the number of identical sgRNA sequences with fastx_collapser and we assigned them to their known identifiers. These counts were employed for downstream data analysis. To provide a sufficient baseline for detecting sgRNA enrichment in experimental samples, we aimed to acquire >1000 reads per sgRNA in the sequenced sgRNA pool to compensate for variation in sgRNA representation inherent in the pooled plasmid preparation or introduced by PCR biases. Reads were normalized to the total number of library-specific reads per lane for each condition. To ensure a proper sgRNA representation in the initial plasmid pool, we used a cutoff of more than 10% average reads/sgRNA sequenced in the Plasmid-Pool (resulting in passing of 3050 out of 3239 sgRNAs). Enrichment analyses were performed using MAGeCK (48).

ChIP sequencing

H3K27Ac and p300 ChIP-seq data from the inv(3) cell line MOLM1 as well as p300 ChIP-seq data from MUTZ3 were previously generated by our group and are available at ArrayExpress E-MTAB-2224 (12). H3K27Ac (Abcam Cat# ab4729, RRID:AB_2118291) ChIPs were performed according to the standard ChIP protocol from Upstate. ChIP with antibodies direct against MYB (Millipore Cat# 05-175, RRID:AB_2148022) or p300 (Diagenode, #C15200211) were performed by first crosslinking for 45 minutes with DSG before formaldehyde crosslinking. ChIP samples were processed according to the Illumina TruSeq ChIP Sample Preparation Protocol (Illumina) or Diagenode Library V3 preparation protocol (Diagenode) and either sequenced single-end (1x 50 bp) on the HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina) or paired-end (2x100 bp) on the Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina). Briefly, reads were aligned to the human reference genome build hg19 with bowtie (49) for single-end runs and bowtie2 (50) for paired-end runs, and bigwig files were generated for visualization with bedtools genomecov (51) and UCSC bedGraphToBigWig (52). Peaks were determined using the MACS2 program with default parameters (53). The tracks were normalised per million reads (RPM) and visualized as genome browser profiles using the Fluff package (54).

Cut&Run

H3K27Ac (Abcam Cat# ab4729, RRID:AB_2118291) Cut&Run libraries for the MUTZ3 bulk and sorted fragments were generated with an input of 200.000 cells. The protocol described by the Henikoff group was used to generate these tracks (55), using a 0.04% Digitonin buffer and with the addition of cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) and 1M Sodiumbutyrate (Sigma Aldrich) to all the buffers. Isolation was done according to the standard Phenol Chloroform protocol. Cut&Run samples were processed according to the protocol described by the Fazzio group (56) and sequenced paired-end (2x100 bp) on the Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina). Reads were aligned similarly to ChIP-seq.

ATAC sequencing

Open chromatin regions were mapped by the ATAC-seq method as described (57) with a modification in the lysis buffer (0.30 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% NP40, 0.15 mM Spermine, 0.5 mM Spermidine, 2 mM 6AA) to reduce mitochondrial DNA contamination. ATAC-seq samples were sequenced paired-end (2x 50 bp) on the HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina) and aligned against the human genome (hg19) with bowtie2, allowing for a maximum 2000 bp insert size. Mitochondrial reads and fragments with mapping quality below 10 were removed.

RNA sequencing

RNA was isolated either using Trizol or the Qiagen Allprep DNA/RNA kit and protocol (Qiagen, #80204). cDNA synthesis was done using the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by using primers (Table S4) as described previously (15) on the 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For RNA sequencing, sample libraries were prepped using 500 ng of input RNA according to the KAPA RNA HyperPrep Kit with RiboErase (HMR) (Roche) using Unique Dual Index adapters (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.). Amplified sample libraries were paired-end sequenced (2x100 bp) on the Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina) and aligned against the human genome (hg19) using STAR version 2.5.4b. Salmon (58) was used to quantify expression of individual transcripts, which were subsequently aggregated to estimate gene-level abundances with tximport (59). Human gene annotation derived from RefSeq (60) was downloaded from UCSC (61) (RefGene) as a GTF file. Transcript-level abundances were normalized to transcripts per million (TPM) for visualization.

Amplicon sequencing

For amplicon sequencing we used a PCR-based NGS library preparation method in combination with the TruSeq Custom Amplicon index kit (Illumina). The first PCR for target selection (Table S4) was performed using Q5 polymerase (NEB), the second nested PCR, to add the index-adapters, with KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready mix (KapaBiosystems). Libraries were sequenced paired-end (2x 250 bp) on the MiSeq platform (Illumina). Reads were trimmed with trimgalore (Trim Galore, RRID:SCR_011847) to remove low-quality bases and adapters, and subsequently aligned to the human reference genome build hg19 with BBMap (BBmap, RRID:SCR_016965) allowing for 1000 bp indels. Mutations introduced by genome editing were analysed and visualised using CRISPResso2 (62). Mutated sequences consisting of up to 5% of sequenced reads were next analysed for differential binding with CIS-BP (63).

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

We show a novel paradigm in which chromosomal aberrations reveal critical regulatory elements that are non-functional at their endogenous locus. This knowledge provides a rationale to develop new compounds to selectively interfere with oncogenic enhancer activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleague Michael Vermeulen and the Bioptics Facility at IMP for flow cytometric sorting. We are thankful to Tobias Neumann for help with the design of the enhancer scanning strategy as well as to the Zuber group at the IMP for their help with the enhancer scanning CRISPR/Cas9 experiments. We thank the Vermeulen group at the Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences for assistance in the DNA-pulldown experiments. Furthermore, we acknowledge Berna Beverloo and the department of Clinical Genetics for the FISH analysis, and colleagues from the bone marrow transplantation group and the molecular diagnostics laboratory of the Department of Hematology for storage of samples and molecular analysis of the leukemia cells. This work was funded by a fellowship from the Daniel den Hoed, Erasmus MC Foundation (L.S.), the Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (R.D., R.M., S.O., and T.G.), the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK68634 (E.H.B), Carbone Cancer Center P30 CA014520 (E.H.B), the National Institutes of Health T32 HL07899 (D.R.M.) and FWF-SFB grant F4710 of the Austrian Science Fund (J.Z). Research at the IMP is generously supported by Boehringer Ingelheim and the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (Headquarter grant FFG-852936).

Financial support

Daniel den Hoed Erasmus MC Foundation, the Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds grant Dutch Cancer Society, the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK68634, Carbone Cancer Center P30 CA014520, the National Institutes of Health T32 HL07899 and FWF-SFB grant F4710 of the Austrian Science Fund, Boehringer Ingelheim and the Austrian Research Promotion Agency Headquarter grant FFG-852936.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

A patent application related to MYBMIM has been submitted by A.K. to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office entitled “Agents and methods for treating CREB binding protein-dependent cancers” (application PCT/US2017/059579). A.K. received personal fees from Novartis and from Rgenta during the conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Garraway LA, Lander ES. Lessons from the cancer genome. Cell 2013;153(1):17–37 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr., Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013;339(6127):1546–58 doi 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurano MT, Humbert R, Rynes E, Thurman RE, Haugen E, Wang H, et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science 2012;337(6099):1190–5 doi 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khurana E, Fu Y, Chakravarty D, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Gerstein M. Role of non-coding sequence variants in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17(2):93–108 doi 10.1038/nrg.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu H, Uuskula-Reimand L, Isaev K, Wadi L, Alizada A, Shuai S, et al. Candidate Cancer Driver Mutations in Distal Regulatory Elements and Long-Range Chromatin Interaction Networks. Mol Cell 2020;77(6):1307–21 e10 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman S, Mansour MR. The role of noncoding mutations in blood cancers. Dis Model Mech 2019;12(11) doi 10.1242/dmm.041988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredriksson NJ, Ny L, Nilsson JA, Larsson E. Systematic analysis of noncoding somatic mutations and gene expression alterations across 14 tumor types. Nat Genet 2014;46(12):1258–63 doi 10.1038/ng.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bresnick EH, Johnson KD. Blood disease-causing and -suppressing transcriptional enhancers: general principles and GATA2 mechanisms. Blood Adv 2019;3(13):2045–56 doi 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansour MR, Abraham BJ, Anders L, Berezovskaya A, Gutierrez A, Durbin AD, et al. Oncogene regulation. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science 2014;346(6215):1373–7 doi 10.1126/science.1259037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herranz D, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Palomero T, Schnell SA, Belver L, Wendorff AA, et al. A NOTCH1-driven MYC enhancer promotes T cell development, transformation and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med 2014;20(10):1130–7 doi 10.1038/nm.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hnisz D, Weintraub AS, Day DS, Valton AL, Bak RO, Li CH, et al. Activation of proto-oncogenes by disruption of chromosome neighborhoods. Science 2016;351(6280):1454–8 doi 10.1126/science.aad9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gröschel S, Sanders MA, Hoogenboezem R, de Wit E, Bouwman BAM, Erpelinck C, et al. A single oncogenic enhancer rearrangement causes concomitant EVI1 and GATA2 deregulation in leukemia. Cell 2014;157(2):369–81 doi S0092-8674(14)00218-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northcott PA, Lee C, Zichner T, Stutz AM, Erkek S, Kawauchi D, et al. Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature 2014;511(7510):428–34 doi 10.1038/nature13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Affer M, Chesi M, Chen WG, Keats JJ, Demchenko YN, Roschke AV, et al. Promiscuous MYC locus rearrangements hijack enhancers but mostly super-enhancers to dysregulate MYC expression in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2014;28(8):1725–35 doi 10.1038/leu.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ottema S, Mulet-Lazaro R, Beverloo HB, Erpelinck C, van Herk S, van der Helm R, et al. Atypical 3q26/MECOM rearrangements genocopy inv(3)/t(3;3) in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2020;136(2):224–34 doi 10.1182/blood.2019003701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani S, Erpelinck C, van Putten WL, Valk PJ, van der Poel-van de Luytgaarde S, Hack R, et al. High EVI1 expression predicts poor survival in acute myeloid leukemia: a study of 319 de novo AML patients. Blood 2003;101(3):837–45 doi 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lugthart S, Gröschel S, Beverloo HB, Sabine K, Peter JMV, Shama Lydia van Z-B, et al. Clinical, Molecular, and Prognostic Significance of WHO Type inv(3)(q21q26.2)/t(3;3)(q21;q26.2) and Various Other 3q Abnormalities in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010;28(24):3890–8 doi 10.1200/jco.2010.29.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lugthart S, van Drunen E, van Norden Y, van Hoven A, Erpelinck CAJ, Valk PJM, et al. High EVI1 levels predict adverse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: prevalence of EVI1 overexpression and chromosome 3q26 abnormalities underestimated. Blood 2008;111(8):4329–37 doi 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morishita K, Parganas E, William CL, Whittaker MH, Drabkin H, Oval J, et al. Activation of EVI1 gene expression in human acute myelogenous leukemias by translocations spanning 300-400 kilobases on chromosome band 3q26. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992;89(9):3937–41 doi 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamazaki H, Suzuki M, Otsuki A, Shimizu R, Bresnick EH, Engel JD, et al. A remote GATA2 hematopoietic enhancer drives leukemogenesis in inv(3)(q21;q26) by activating EVI1 expression. Cancer Cell 2014;25(4):415–27 doi S1535-6108(14)00076-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grass JA, Jing H, Kim SI, Martowicz ML, Pal S, Blobel GA, et al. Distinct functions of dispersed GATA factor complexes at an endogenous gene locus. Mol Cell Biol 2006;26(19):7056–67 doi 10.1128/MCB.01033-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KD, Kong G, Gao X, Chang YI, Hewitt KJ, Sanalkumar R, et al. Cis-regulatory mechanisms governing stem and progenitor cell transitions. Sci Adv 2015;1(8):e1500503 doi 10.1126/sciadv.1500503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson NK, Foster SD, Wang X, Knezevic K, Schutte J, Kaimakis P, et al. Combinatorial transcriptional control in blood stem/progenitor cells: genome-wide analysis of ten major transcriptional regulators. Cell Stem Cell 2010;7(4):532–44 doi 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck D, Thoms JA, Perera D, Schutte J, Unnikrishnan A, Knezevic K, et al. Genome-wide analysis of transcriptional regulators in human HSPCs reveals a densely interconnected network of coding and noncoding genes. Blood 2013;122(14):e12–22 doi 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramaswamy K, Forbes L, Minuesa G, Gindin T, Brown F, Kharas MG, et al. Peptidomimetic blockade of MYB in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):110 doi 10.1038/s41467-017-02618-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimi A, Goyama S, Watanabe-Okochi N, Yoshiki Y, Nannya Y, Nitta E, et al. Evi1 represses PTEN expression and activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR via interactions with polycomb proteins. Blood 2011;117(13):3617–28 doi 10.1182/blood-2009-12-261602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loven J, Hoke HA, Lin CY, Lau A, Orlando DA, Vakoc CR, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell 2013;153(2):320–34 doi S0092-8674(13)00393-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drier Y, Cotton MJ, Williamson KE, Gillespie SM, Ryan RJ, Kluk MJ, et al. An oncogenic MYB feedback loop drives alternate cell fates in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat Genet 2016;48(3):265–72 doi 10.1038/ng.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakamoto H, Dai G, Tsujino K, Hashimoto K, Huang X, Fujimoto T, et al. Proper levels of c-Myb are discretely defined at distinct steps of hematopoietic cell development. Blood 2006;108(3):896–903 doi 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beug H, von Kirchbach A, Doderlein G, Conscience JF, Graf T. Chicken hematopoietic cells transformed by seven strains of defective avian leukemia viruses display three distinct phenotypes of differentiation. Cell 1979;18(2):375–90 doi 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weston K, Bishop JM. Transcriptional activation by the v-myb oncogene and its cellular progenitor, c-myb. Cell 1989;58(1):85–93 doi 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman S, Magnussen M, Leon TE, Farah N, Li Z, Abraham BJ, et al. Activation of the LMO2 oncogene through a somatically acquired neomorphic promoter in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2017;129(24):3221–6 doi 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen N, Vishwakarma BA, Oakley K, Han Y, Przychodzen B, Maciejewski JP, et al. Myb expression is critical for myeloid leukemia development induced by Setbp1 activation. Oncotarget 2016;7(52):86300–12 doi 10.18632/oncotarget.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8(7):523–34 doi 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuber J, Rappaport AR, Luo W, Wang E, Chen C, Vaseva AV, et al. An integrated approach to dissecting oncogene addiction implicates a Myb-coordinated self-renewal program as essential for leukemia maintenance. Genes Dev 2011;25(15):1628–40 doi 10.1101/gad.17269211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasper LH, Boussouar F, Ney PA, Jackson CW, Rehg J, van Deursen JM, et al. A transcription-factor-binding surface of coactivator p300 is required for haematopoiesis. Nature 2002;419(6908):738–43 doi 10.1038/nature01062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandberg ML, Sutton SE, Pletcher MT, Wiltshire T, Tarantino LM, Hogenesch JB, et al. c-Myb and p300 regulate hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Dev Cell 2005;8(2):153–66 doi 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Best JL, Amezcua CA, Mayr B, Flechner L, Murawsky CM, Emerson B, et al. Identification of small-molecule antagonists that inhibit an activator: coactivator interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(51):17622–7 doi 10.1073/pnas.0406374101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uttarkar S, Dukare S, Bopp B, Goblirsch M, Jose J, Klempnauer KH. Naphthol AS-E Phosphate Inhibits the Activity of the Transcription Factor Myb by Blocking the Interaction with the KIX Domain of the Coactivator p300. Mol Cancer Ther 2015;14(6):1276–85 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uttarkar S, Piontek T, Dukare S, Schomburg C, Schlenke P, Berdel WE, et al. Small-Molecule Disruption of the Myb/p300 Cooperation Targets Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15(12):2905–15 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walf-Vorderwulbecke V, Pearce K, Brooks T, Hubank M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Zwaan CM, et al. Targeting acute myeloid leukemia by drug-induced c-MYB degradation. Leukemia 2018;32(4):882–9 doi 10.1038/leu.2017.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takao S, Forbes L, Uni M, Cheng S, Pineda JMB, Tarumoto Y, et al. Convergent organization of aberrant MYB complex controls oncogenic gene expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Elife 2021;10 doi 10.7554/eLife.65905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roe JS, Mercan F, Rivera K, Pappin DJ, Vakoc CR. BET Bromodomain Inhibition Suppresses the Function of Hematopoietic Transcription Factors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Mol Cell 2015;58(6):1028–39 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diffner E, Beck D, Gudgin E, Thoms JA, Knezevic K, Pridans C, et al. Activity of a heptad of transcription factors is associated with stem cell programs and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013;121(12):2289–300 doi 10.1182/blood-2012-07-446120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karemaker ID, Vermeulen M. ZBTB2 reads unmethylated CpG island promoters and regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation. EMBO Rep 2018;19(4) doi 10.15252/embr.201744993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGowan-Jordan J, Simons A, Schmid M. ISCN : an international system for human cytogenomic nomenclature (2016). Basel ; New York: : Karger; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michlits G, Jude J, Hinterndorfer M, de Almeida M, Vainorius G, Hubmann M, et al. Multilayered VBC score predicts sgRNAs that efficiently generate loss-of-function alleles. Nat Methods 2020;17(7):708–16 doi 10.1038/s41592-020-0850-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W, Xu H, Xiao T, Cong L, Love MI, Zhang F, et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biology 2014;15(12):554 doi 10.1186/s13059-014-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 2009;10(3):R25 doi 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012;9(4):357–9 doi 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010;26(6):841–2 doi 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kent WJ, Zweig AS, Barber G, Hinrichs AS, Karolchik D. BigWig and BigBed: enabling browsing of large distributed datasets. Bioinformatics 2010;26(17):2204–7 doi 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 2008;9(9):R137 doi 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Georgiou G, van Heeringen SJ. fluff: exploratory analysis and visualization of high-throughput sequencing data. PeerJ 2016;4:e2209 doi 10.7717/peerj.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skene PJ, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. Targeted in situ genome-wide profiling with high efficiency for low cell numbers. Nat Protoc 2018;13(5):1006–19 doi 10.1038/nprot.2018.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hainer SJ, Boskovic A, McCannell KN, Rando OJ, Fazzio TG. Profiling of Pluripotency Factors in Single Cells and Early Embryos. Cell 2019;177(5):1319–29 e11 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods 2013;10(12):1213–8 doi 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 2017;14(4):417–9 doi 10.1038/nmeth.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res 2015;4:1521 doi 10.12688/f1000research.7563.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Leary NA, Wright MW, Brister JR, Ciufo S, Haddad D, McVeigh R, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(D1):D733–45 doi 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karolchik D, Hinrichs AS, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Sugnet CW, Haussler D, et al. The UCSC Table Browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32(Database issue):D493–6 doi 10.1093/nar/gkh103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clement K, Rees H, Canver MC, Gehrke JM, Farouni R, Hsu JY, et al. CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37(3):224–6 doi 10.1038/s41587-019-0032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weirauch MT, Yang A, Albu M, Cote AG, Montenegro-Montero A, Drewe P, et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell 2014;158(6):1431–43 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Cell line sequence data generated in this study have been deposited at the EMBL-EBI ArrayExpress database (ArrayExpress, RRID:SCR_002964) under accession numbers E-MTAB-9939 (RNA-seq), E-MTAB-9949 (ATAC-seq), E-MTAB-9946 (Cut&Run-seq), E-MTAB-9945 (Amplicon-seq), E-MTAB-9948 (CRISPR enhancer scan) and E-MTAB-9959 (ChIP-seq). ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data derived from donors or patients have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (The European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), RRID:SCR_004944) under the accession number EGAS00001004839. This study did not generate any unique codes. All software tools used in this study are freely or commercially available.