Abstract

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPeM) is a rare but aggressive malignancy with limited treatment options. VEGF inhibition enhances efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors by reworking the immunosuppressive tumor milieu. Efficacy and safety of combined PD-L1 (atezolizumab) and VEGF (bevacizumab) blockade (AtezoBev) was assessed in 20 patients with advanced and unresectable MPeM with progression or intolerance to prior platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy. The primary endpoint of confirmed objective response rate per RECISTv1.1 by independent radiology review was 40% (8/20; 95%CI:19.1–64.0) with median response duration of 12.8 months. Six (75%) responses lasted for >10 months. Progression-free and overall survival at 1-year were 61% (95%CI:35–80) and 85% (95%CI:60–95), respectively. Responses occurred notwithstanding low tumor mutation burden and PD-L1 expression status. Baseline epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene-expression correlated with therapeutic resistance/response (r=0.80; P=0.0010). AtezoBev showed promising and durable efficacy in patients with advanced MPeM with acceptable safety profile and these results address a grave unmet need for this orphan disease.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Atezolizumab, Bevacizumab, Immunotherapy, Peritoneal mesothelioma

Introduction

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPeM) is a rare and lethal cancer with annual incidence of 0·11/100,000 and a 5-year survival lower than 20%.(1,2) MPeM arises from mesothelial cells that line the serosal layer of peritoneum and typically presents with abdominal discomfort, distension and ascites. In contrast to its more familiar analogue, “malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM)”, MPeM is far less frequent (estimated 275 vs. 2458 new cases per year in the United States) and understudied (Figure S1a–b).(2) MPeM has a weaker association with asbestos exposure (attributable-risk: 50% vs. 88%), affects women more frequently (44% vs. 19%), occurs at younger age (median: 63 vs. 71 years) and diagnosed more often with advanced disease (73% vs. 65%) compared to MPM.(1–3) MPeM and MPM also appear to be molecularly dissimilar with copy number gains and BAP1 mutations more common in MPeM.(4,5)

Treatment strategies for MPeM can vary by patient and disease factors.(6) While optimal cytoreductive surgery (CRS) (completeness of cytoreduction score [CCS]-0/1: residual disease <2.5 mm) and hyperthermic intraoperative peritoneal perfusion with chemotherapy (HIPEC) or early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC) results in good outcomes for select patients, a substantial proportion need systemic therapy and have limited survival.(1,6) Despite these recognized clinico-molecular and epidemiological differences, systemic therapy for MPeM is largely based on data extrapolated from MPM or scant retrospective/prospective evidence; hence consensus regarding optimal treatment is lacking.(7,8) National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends first-line platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy for both mesotheliomas, but after failure of this first-line therapy there is no recommended standard or U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved therapy for advanced MPeM and a critical unmet need of novel therapies for this orphan disease, exists.(9,10)

MPeM harbors a complex immune-milieu and a pro-inflammatory microenvironment with 50–60% cases expressing PD-L1 (Programmed death-ligand 1).(11–13) While, immune-checkpoint inhibition (ICI) has shown efficacy in MPM, data in MPeM patients is limited and efficacy is low (Table S1).(14) Key studies of ICI in mesothelioma, such as Checkmate-743 and PROMISE-meso trials were exclusively designed for MPM and excluded patients with MPeM.(15,16) Consequently, the body of evidence and approval for ICI is restricted to patients with MPM. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway is functional in MPeM and VEGF inhibition results in decreased proliferation and metastasis in vivo.(17,18) An active VEGF axis also facilitates immune evasion.(19) VEGF inhibition, by converting an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment to an immunopermissive one through increased infiltration of immune effector cells and better antigen presentation, can augment responses to ICI.(20,21) We hypothesized that combining ICI and antiangiogenic therapy can have synergistic activity in MPeM.

Atezolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) that targets PD-L1, blocks its interactions with PD-1 and B7-1 (CD80) receptors and reverses T-cell suppression. Bevacizumab is a mAb against VEGF-A that inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab (AtezoBev) has shown robust activity in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and is FDA approved for this indication.(21) We conducted this phase 2 trial to assess safety and efficacy of AtezoBev in patients with advanced previously treated MPeM and to identify biomarkers of treatment response.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between March 30, 2017, and February 12, 2019, 20 patients were enrolled and treated with AtezoBev. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Median age was 63 years (range:33–87). Most patient were women (60%) and self-reported no prior asbestos exposure (75%). Biphasic histology was seen in two (10%) patients while remaining were epithelioid. Twelve (60%) of these patients had prior CRS and HIPEC in addition to systemic chemotherapy. All patients had received prior platinum-pemetrexed therapy (only one patient had prior bevacizumab) and 8 (40%) patients had received ≥2 lines of therapy pre-enrollment. The median time from last systemic therapy to trial enrollment was 1.5 months. Seventeen (85%) patients had documented disease progression and 3 (15%) were intolerant to prior platinum-pemetrexed therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline

| Characteristics | Patients (N = 20) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (years) | ||

| Median (range) | 63 (33 – 87) | |

| < 60 years | 6 | 30 |

| ≥ 60 years | 14 | 70 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 12 | 60 |

| Male | 8 | 40 |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance status | ||

| 0 | 12 | 60 |

| 1 | 8 | 40 |

| Tumor histology | ||

| Epithelioid | 18 | 90 |

| Biphasic | 2 | 10 |

| Prior asbestos exposure 1 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 25 |

| No | 15 | 75 |

| Presence of extraperitoneal metastases | ||

| Yes | 6 | 30 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | ||

| Elevated | 4 | 20 |

| Platelet count | ||

| Elevated | 5 | 25 |

| Time to trial since first diagnosis (years) | ||

| Median (range) | 2.2 (0.5 – 10.3) | |

| < 1 year | 8 | 40 |

| ≥ 1 year | 12 | 60 |

| Prior cytoreductive surgery | ||

| Yes | 12 | 60 |

| No | 8 | 40 |

| Number of previous anticancer lines of treatment | ||

| 1 | 12 | 60 |

| 2 or 3 | 8 | 40 |

| Best response to prior platinum-pemetrexed therapy 2 | ||

| Regression | 9 | 45 |

| Stability | 7 | 35 |

| Progression | 4 | 20 |

| Mismatch-repair (MMR)/Microsatellite (MSI) status 3 | ||

| Proficient-MMR/MSS | 19 | 100 |

| Deficient-MMR/MSI-H | 0 | 0 |

| PD-L1 status 2 | ||

| Negative | 4 | 31 |

| 1%−50% | 6 | 46 |

| 50%−100% | 3 | 23 |

| Tumor mutation burden (TMB) (mutation/megabase) 3 | ||

| Median (range) | 0·8 (0·4 – 20·7) | |

| TMB-Low (< 10) | 13 | 93 |

| TMB-High (≥ 10) | 1 | 7 |

Prior asbestos exposure was ascertained using patient reported occupational/exposure history assessment by treating provider documented in electronic medical records.

Response was assessed as per radiologist and treating physician discretion and reported as either disease regression, stability, or progression.

Patients were not evaluable due to missing or poor quality/quantity samples. Proportions in these cases were calculated using patients with available results.

Efficacy Analyses

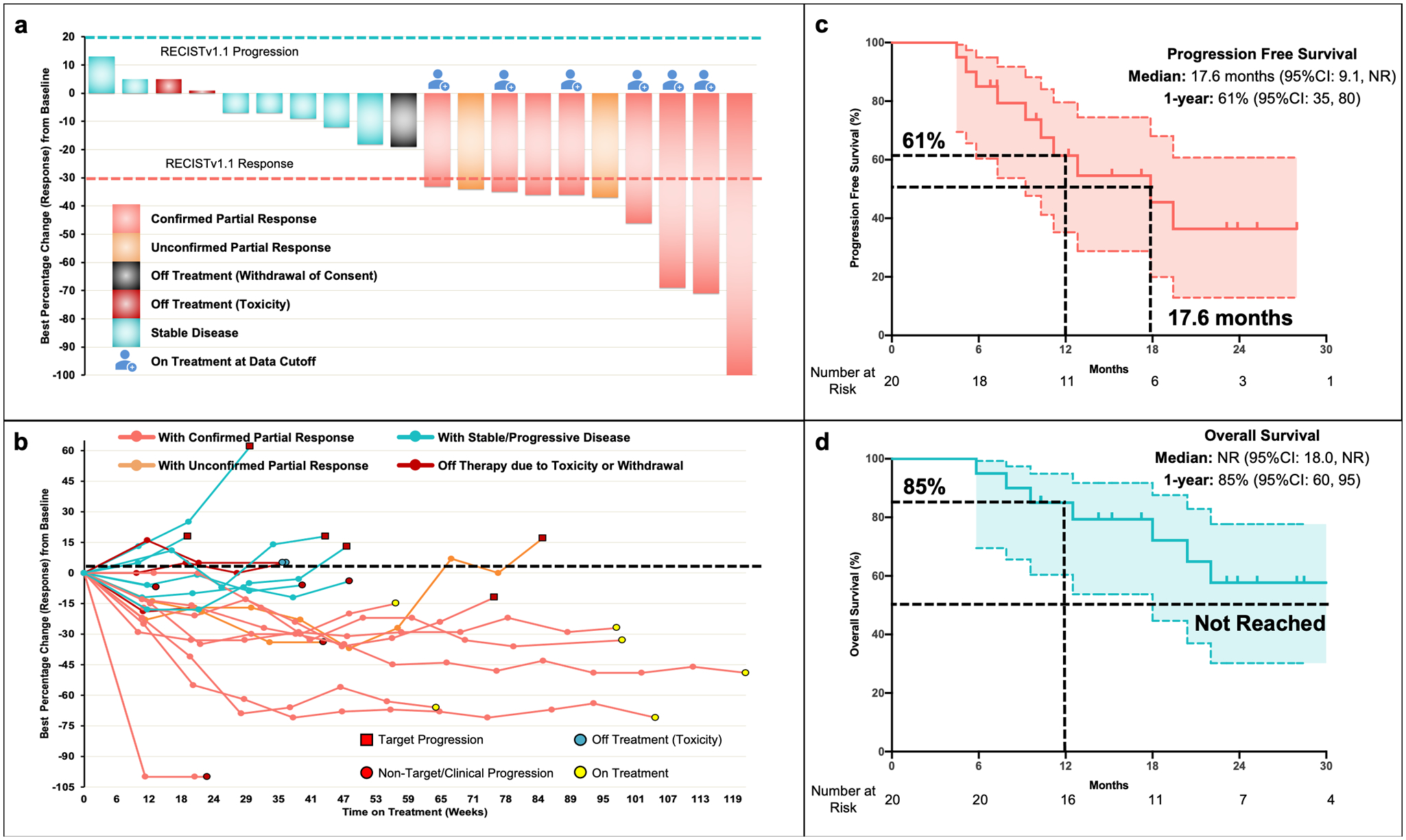

At data cutoff, the median follow-up was 23.5 months (range:10.1–36.1). Patients received a median of 15 (range:4–38) cycles and 6 (30%) patients continued treatment at time of data cutoff. Reasons for treatment discontinuation were disease progression (10 [50%]), toxicity (2 [10%]), death (1 [5%]) and withdrawal of consent (1 [5%]). Among 20 evaluable patients, the primary endpoint of confirmed objective response rate (ORR) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors-version1.1 (RECISTv1.1) by independent radiology review (IRR) was 40% (95%CI:19.1–64.0) (8/20 patients) (Figure 1a). Responses were ongoing in 6 (75%) of these 8 patients at data cutoff. Median duration of response (DoR) was 12.8 months (Figure 1b) in responders. In a post-hoc analysis, similar ORR was observed across key clinical subgroups reflecting patient, disease, and pre-study treatment factors (Figure S2). Disease control at 12 and 18 weeks per RECISTv1.1 was seen in 19 (95%) and 17 (85%) patients, respectively. Figure S3a–d illustrates key responses in patients on study. No pseudo-progression was seen in our cohort. At data cutoff, 10 (50%) progression events and 7 (35%) deaths were seen. Most patients progressed within the peritoneal cavity and two (20%) patients had extraperitoneal progression. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated to be 17.6 months (95%CI:9.1-not reached [NR]) and 1-year PFS was 61% (95%CI:35–80) (Figure 1c). Median overall survival (OS) was not reached at data cutoff. The 1-year OS was 85% (95%CI:60–95) (Figure 1d). Corresponding outcomes per immune-modified RECIST (imRECIST) are shown in Table S2.

Figure 1. Tumor Response and Survival Outcomes on Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab (AtezoBev) in Patients with Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma (MPeM).

Panel a (Waterfall-plot) shows the maximum percent change from baseline in the sum of the longest diameters (short axis in case of lymph nodes) of target lesions in 20 patients who were treated on the current study and underwent radiological evaluation. Tumor measurements and response assessments were performed by independent radiology review according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors - version 1.1 (RECISTv1.1). Partial response (PR) was defined by ≥ 30% decrease in sum of target lesions with the assumption of no new lesions and no progression in non-target lesions. PR was considered as confirmed only if PR was maintained and seen on 2 consecutive scans (in this study scans were done 9 weeks apart). Panel b (Spider plot) shows the change in sum of target lesion diameters over time. Durable responses were observed in patients. Non-target progression was seen in a notable subset of patients since ascites and non-measurable peritoneal disease is common in MPeM. Two patients had discontinuation of therapy due to toxicity (immune-mediated pancreatitis and thrombocytopenia). Panel c and d (KapIan-Meier curves) show progression-free survival and overall survival of patients with advanced previously treated malignant peritoneal mesothelioma who received AtezoBev on study at the time of data cutoff as assessed by independent central review. Progression-free and overall survival was measured from study initiation to disease progression/death and death, respectively. Abbreviations: 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; NR, not reached

We performed an exploratory analysis to assess impact of selection bias pertaining to indolent tumor biology in confounding outcomes by evaluating patient and population dynamics of the study cohort (all 20 patients) prior to enrollment (Supplementary Methods 1). We reviewed their treatment course on platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy prior to study enrollment using electronic medical records. Time to next treatment was defined as the time interval between treatment (platinum-pemetrexed) initiation and commencement of next line of therapy as per treating physician discretion and included time on maintenance pemetrexed, duration of reintroduction and treatment breaks. Disease regression with chemotherapy was seen in 35% patients, similar to the reported response rate with platinum-pemetrexed combination in prior studies for this population.(9) The median time to next treatment on standard of care platinum-pemetrexed treatment prior to enrollment was 8.3 months (95%CI:6.3–10.3) compared to 17·6 months with AtezoBev on study (Figure S4 and S5). Durable responses to AtezoBev were seen regardless of response characteristics on prior chemotherapy (Figure S5).

Safety Analyses

All 20 patients were included in safety analyses and received a median of 15 (range:4–38) cycles of AtezoBev. Mean dose intensity was 99% for atezolizumab and 81% for bevacizumab. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TRAEs) of any grade were reported by 17 (85%) patients (Table 2 and S3). Grade 3 TRAEs occurred in 10 (50%) patients; most common were hypertension (40%) and anemia (10%). No grade 4/5 events occurred. Two (10%) patients had grade 3 immune-related AEs, pancreatitis and thrombocytopenia managed with corticosteroids, required treatment discontinuation. Proteinuria, the only TRAEs that caused dose interruptions (all bevacizumab) occurred in 5 (25%) patients, after a median of 6 cycles. One patient death on-study was attributed to disease progression. TRAEs that occurred in at least 10% and 20% of patients (or grade 3 events) are listed in Table S3 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 2.

Treatment-related Adverse Events

| Adverse Event1 | All Grades (%) | Grade ≥ 3 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 12 (60) | 8 (40) |

| Fatigue | 8 (40) | 1 (5) |

| Anorexia | 6 (30) | |

| Proteinuria | 6 (30) | |

| Constipation | 5 (25) | |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 5 (25) | |

| Nausea | 5 (25) | |

| Pruritus | 5 (25) | |

| Arthralgia | 4 (20) | |

| Diarrhea | 4 (20) | |

| Epistaxis | 4 (20) | |

| Vomiting | 4 (20) | |

| Weight loss | 4 (20) | |

| Abdominal Pain | 3 (15) | 1 (5) |

| Anemia | 2 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Platelet count decreased | 2 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Ileus | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Thromboembolic event | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) listed here include all those that occurred on study in ≥ 20% patients regardless of grade and all grade ≥ 3 events. All TRAEs are coded and graded as per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0. No grade 4 or 5 TRAEs occurred on study.

Biomarker Analyses

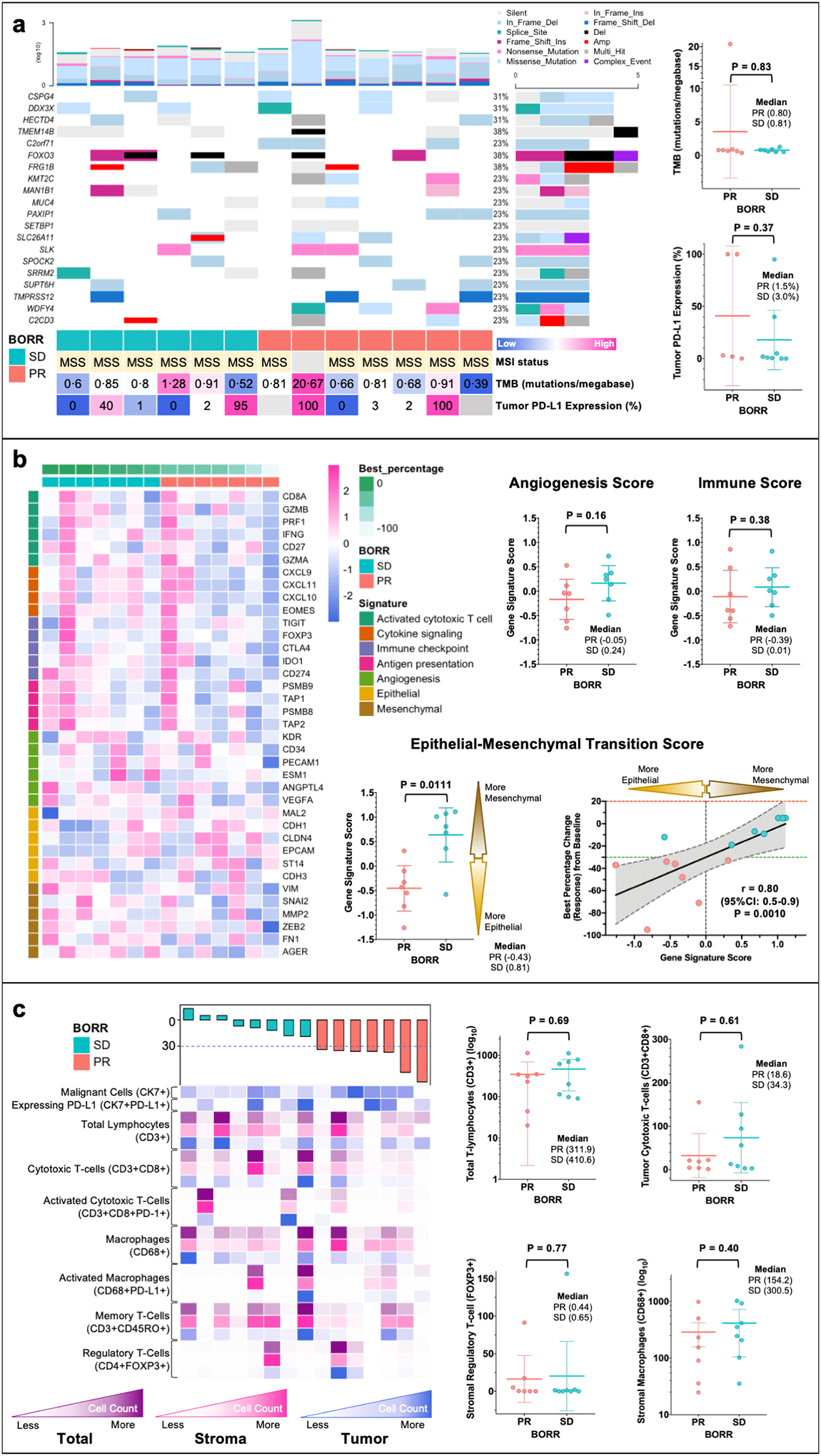

Firstly, we evaluated whether established biomarkers of response to ICI used clinically (microsatellite instability [MSI], PD-L1 and tumor mutational burden [TMB] status) in other tumors predicted response in our MPeM patients treated with AtezoBev on study. PD-L1 and TMB status was determined in 13 (65%) and 14 (70%), respectively. PD-L1 expression of 0%, 1–50% and ≥50% was seen in 4 (31%), 6 (46%), and 3 (23%) patients, respectively. Responses were seen in both PD-L1 positive and negative cases (44.5% vs. 25.0%; odds-ratio (OR) 2.4, 95%CI:0.2–38.0; P>0.99) and median PD-L1 expression did not differ between responders and non-responders (Figure 2a). Median TMB for all patients was 0.8 mutations/megabase (range:0.4–20.7) and one patient had high-TMB (≥10 mutations/megabase) (Figure S6). Median TMB was similar among responders and non-responders (0.8 vs. 0.8; P=0.83) (Figure 2a). Using WES, we did not find any association between response and specific gene alterations (mutations or copy number variations) (Figure 2a and S7).

Figure 2. Exploratory Biomarker Analyses of Pre-treatment Tumor Tissue Samples for Patients with Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma (MPeM) Treated with Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab (AtezoBev) on Study.

Tissue samples underwent immunohistochemistry (IHC), whole-exome (WES) and RNA sequencing (RNAseq) and multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) with rigorous quality check. Mechanistically relevant biomarkers were evaluated and compared between responders (PR) and non-responders (SD) using heatmaps (columns representing patients and rows representing gene/cell type) and scatter dot plots (all plots show each patient with line at mean and whiskers at 95%CI). Panel a shows oncoplot with 20 most common genes altered in patients on trial. Patients are arranged in order of best percentage change (response) in tumor measurements from baseline (from left to right: increase to decrease) as per RECISTv1.1 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors - version 1.1). The color bar at bottom shows response for each patient (PR [responder] and SD [non-responder with stable disease]). The barplot on top and right show number of mutations (log) for each patient and frequency of mutations for each gene in all patients, respectively. Panel b shows pre-treatment tumor gene signature analyses as per gene signatures defining immune biology, angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The figure panel also shows strong correlation between EMT gene signature score and degree of response to AtezoBev per RECISTv1.1. Panel c illustrates the immune milieu (tumor, stroma, and total) of tumors sections at baseline using multiplex immunofluorescence. No specific cell types (key cell types shown in figure) prior to treatment were found to be associated response with AtezoBev.

We then explored plausible biology underlying efficacy of combined PD-L1 and VEGF blockade using transcriptomic profiling in 14 (70%) patients with evaluable pretreatment tumors. Gene expression scores were calculated for each patient using normalized RNA expression fitted to established signatures based on associations with following biology: immune-sensitivity, angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Supplementary Methods 2).(22–24) Heatmap of genes delimiting immune-sensitivity and angiogenesis failed to show any distinct subgroups and median gene-signature scores were similar between responders and non-responders (Figure 2b and S8).(22,23) Conversely, the EMT gene-signature scores were lower (favoring an epithelial over mesenchymal phenotype) in responders (median: −0.4 vs. 0.8) compared to non-responders and correlated with the magnitude of response (spearman r: 0.8; 95%CI:0.5–0.9; P=0.0010) (Figure 2b).(24) High EMT gene-expression was associated with poorer ORR (14% vs. 86%; OR 0.03, 95%CI:0.0–0.6; P=0.029) but no differences were seen with other scores (Figure S9). To identify modulations following treatment we compared change in gene signature scores between baseline and on-treatment samples and found no significant association with response (Figure S10).

To delineate a specific immune-milieu predictive of response to AtezoBev, we examined pre-treatment immune cell subsets across tumor and stroma using multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) in 15 (75%) available patient samples. Density of key immune effector cells (number of cells/mm2) such as total lymphocytes (CD3+), cytotoxic T-cells (CD3+CD8+), and regulatory T-Cells (FOXP3+) and macrophages (CD68+) and ratio of effector/suppressor cells did not differ significantly between responder and non-responders (Figure 2c and S11).

Discussion

MPeM is a life-threatening malignancy with limited treatment options beyond first-line platinum-pemetrexed based chemotherapy. Despite this unmet need, the rarity of MPeM, has hindered attentive research. Dedicated trials are missing as efforts have focused on MPM, creating evidence gaps in how we treat these patients. Our study designed specifically for MPeM, acknowledging differences between MPeM and MPM, is a singular but necessary venture in this rare tumor.(25) In this study, AtezoBev demonstrated a confirmed ORR of 40% in platinum-pemetrexed treated MPeM. These responses were durable with median DoR in excess of 12 months. Notably we observed meaningful PFS and OS of 61% and 85% at 1-year, respectively. Therapy was very well-tolerated with a safety profile consistent with prior reports.(21) Most AEs were grade 1/2 and no grade 4/5 toxicity occurred. Grade 3 AEs were readily manageable and did not require treatment discontinuation barring immune-mediated AEs in two patients.

Although nivolumab and ipilimumab and bevacizumab are available to patients with MPM as standard first-line option based on results of Checkmate-743 and MAPS trials, these are not approved for use in MPeM.(16,26) MPeM and MPM also appear to dissimilar in their expression of PD-L1 and in their response to ICI.(13,14) PD-L1 expression is seen in nearly 50% of patients with MPeM compared to 30% in MPM.(13) In a small study enrolling both MPM and MPeM, pembrolizumab showed an ORR of 20% in pleural (N=56) versus 12.5% in peritoneal (N=8) mesothelioma.(14) The strong therapeutic effect in this study of AtezoBev in patients with MPeM, as measured by a 40% confirmed ORR and 1-year OS of 85% compared to the 1-year OS of 45–56% reported in literature for patients with systemic therapy is notable.(6,9,10) This promising response rate and the totality of evidence (with substantial DoR, PFS and OS) compares very favorably with any therapies available for these patients in clinical practice (Table S4), although prospective data and consensus is lacking for these therapies in MPeM. Responses with therapies in second and subsequent lines occur in 10–25% patients and are often short-lived with limited median PFS (2–7 months) and OS (6–18 months). Since historical data regarding MPeM are scarce, we leveraged real-world evidence to further our evidence of benefit from AtezoBev. We showed that responses to AtezoBev occurred regardless of outcomes with prior platinum-pemetrexed and duration of treatment with AtezoBev was distinctly longer (17.6 vs. 8.3 months) compared to time to next treatment from previous platinum-pemetrexed therapy. The better tolerance of AtezoBev over chemotherapy also allows for this prolonged treatment duration. Notably, our trial population characteristics at baseline and behavior prior to study enrollment were consistent with historical multicenter expanded-access experience in MPeM arguing for a representative cohort.(9) Though, there are limitations to such intrapatient comparisons, such as inability to compare histology subtype or history of asbestos exposure, not been reported in these cohorts, the data presented here has significant clinical implication for this orphan disease. The authors recommend that AtezoBev should be considered a meaningful treatment option for these patients barring clinical trial participation. Although, our study allowed prior bevacizumab, we cannot determine the true efficacy of AtezoBev in patients with prior exposure to anti-VEGF drugs, since only one patient had prior bevacizumab. Notably, this patient did achieve a durable response to AtezoBev.

Integration of pre/on-treatment biopsies in this trial demonstrates the feasibility and value of a translationally driven approach in rare cancers. Using this we demonstrated that strong activity of AtezoBev seen in our patients with MPeM did not correlate with clinically established biomarkers (PD-L1 and TMB) of response to ICI in other tumors, although these are not validated in mesothelioma. All tumors were MSS as expected since this is a rare occurrence in mesothelioma.(27) Responses also occurred in PD-L1 negative patients although a trend towards a higher response rate was seen with PD-L1 positivity. However, PD-L1 staining and interpretation in patients can vary with the assay (Ventana SP263 clone as used in our study versus Ventana SP142 and Dako 22C3), as sensitivity and specificity are different; although good correlation is seen across the assays.(28) Since PD-L1 expression in MPeM may be affected by prior therapy, this is an important consideration in designing future trials in this population. Furthermore, our comprehensive profiling demonstrated EMT phenotype as a resistance mechanism to AtezoBev. EMT gene-signature score has been reported to blunt responses to ICI in lung cancer and have a prognostic impact in MPM.(24,29) In our cohort mesenchymal phenotype (higher EMT gene scores) was associated with poorer PFS on both AtezoBev and prior platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy (Figure S12). To further the validity of this finding we explored a sarcomatoid component (S-comp) and EMT gene signature scores derived from metanalysis of published classifications in MPM in our study cohort.(30) Although S-comp score overall showed no association with response, we found a strong correlation between the two EMT scores (Spearman r: 0.72, P=0.005) and similar trend of responders having lower EMT scores than non-responders (Figure S13).(24,30) Even among patients with epithelioid subtype (after excluding biphasic cases), EMT continued to be a predictor of response (median EMT score in responders vs. non-responders: −0.49 vs. 0.81, P=0.014). These results indicate that transcriptomic mesenchymal differentiation is a predictor of poor outcomes with AtezoBev in MPeM, including epithelioid MPeM (Figure S13).

Clinically, ICI and VEGF blockade individually have demonstrated limited activity with modest response rates as single agents in mesothelioma (Table S1). Clinical trials have shown response rates between 7–20% and 0–6% for ICI and VEGF inhibition, with corresponding median PFS of 2.5–6.2 months and 2.2–4.1 months, respectively. Both response rate and PFS with AtezoBev in our study appears to be much better than would be expected with single-agent activity. Our gene-expression analyses showing lack of any predictive impact of angiogenic, and immune signatures furthers the proof-of-component with AtezoBev and argues that the efficacy of AtezoBev in our cohort is conceivably a result of complex synergistic interactions of dual PD-L1 and VEGF blockade rather than each drug alone. To investigate this, we explored prognostic transcriptomic profiles described in MPM (hot/immune-checkpoint+/angiogenic+, VEGF2+/VISTA+ and cold/angiogenic) in our cohort, but found no clear predictive signatures for AtezoBev in our MPeM cohort (Figure S14).(31) However, since these analyses are limited by size and hypothesis-generating in nature, further investigations are required to elucidate the mechanism of this synergy. Efforts using a comprehensive integrated multiomic analyses aimed at understanding the molecular continuum and heterogeneity in these patients can help uncover this biology. Additionally, although our study offers a much-needed treatment option, a subset of patients fails to derive any benefit with AtezoBev. Trials investigating addition of AtezoBev to chemotherapy and use of novel immune targets and combinatorial immunomodulator strategies are needed. Future collaborative efforts should be considered high priority if we are to benefit more patients.

In conclusion, AtezoBev was well-tolerated and led to robust and durable responses in patients with MPeM who had progressed on or were intolerant to prior platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy with meaningful prolongation of survival. This study establishes a promising treatment option for our patients who suffer from this morbid cancer and represents an unprecedented effort to bridge the gap of dedicated research in this orphan disease.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years old, had histologically confirmed advanced MPeM not amenable to definitive CRS (according to peritoneal-multidisciplinary tumor board) and had progressed on or were intolerant to at least one line of systemic chemotherapy involving platinum-pemetrexed doublet. Prior bevacizumab was allowed (Supplementary Methods 2). Patients were required to have measurable disease according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors-version1.1 (RECISTv1.1), an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1 and normal organ/bone marrow function. Extraperitoneal metastases including pleural and lung metastases were allowed. Key exclusion criteria were any prior immunotherapy, diagnosis of active autoimmune disease or immunodeficiency, concurrent malignancy, any known history of active/untreated central nervous system metastases and ongoing systemic immunosuppressive therapy at time of enrollment. Full eligibility criteria are provided in study protocol (Supplementary-Protocol).

Study Design

This phase 2 single-center study was designed as an open-label, single-stage, multicohort basket trial for evaluation of AtezoBev in a variety of advanced rare cancers, including MPeM. Each cohort of 20 patients had an individual analysis planned and this manuscript reports on the results of the MPeM cohort. Atezolizumab was administered at a fixed dose of 1200mg in combination with bevacizumab at a dose of 15mg/kg intravenously every 21 days until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Dose modifications were not permitted. Dose interruptions were allowed for bevacizumab if a patient had related adverse events and patients were permitted to continue atezolizumab alone. Patients with initial progression could continue therapy if they were clinically well and assessed for pseudo-progression per defined criteria. Details are provided in study protocol (Supplementary-Protocol). The objective of this study was to determine the clinical efficacy and safety of AtezoBev for patients with advanced MPeM who have failed prior systemic treatment with platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy. The primary end point was confirmed objective response rate (ORR) per RECISTv1.1 by independent radiology review (IRR). Key pre-specified secondary endpoints were safety, disease control rate (DCR: percentage of patients who achieved confirmed response or confirmed stable disease), duration of response (DoR: defined as time interval between date of first confirmed response to progression), progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS). ORR, DCR, DoR and PFS were also assessed per immune-modified RECIST (imRECIST) criteria. Exploratory objective was to examine tissue correlates for clinical activity.

The protocol and all amendments were approved by the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Patients provided written informed consent before study enrollment. Full protocol is provided (Supplementary-Protocol) (NCT03074513).

Study Assessments

Tumor assessments were done using either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to include chest, abdomen and pelvis at baseline and every 9 weeks until disease progression. Consistent imaging modality was used for tumor assessment for each patient. Tumor measurements by IRR using RECISTv1.1 were performed by Institutional Quantitative Imaging Analysis Core. Responses, partial (PR) or complete (CR), were confirmed on subsequent scans in 9 weeks (at least 4 weeks as per protocol) after the initial response. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were assessed from the date of initiation of protocol therapy until ≥28 days after last dose. Adverse events (AEs) were classified and graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events-version4.0 (CTCAEv4.0). Baseline (within 7 days prior to treatment initiation) and on-treatment (Cycle 2 Day 1 ± 7 days) tumor specimens were obtained from all patients. Blood was also collected for correlative analyses. Details are provided in study protocol (Supplementary-Protocol).

Biomarker Analyses

Tumor microsatellite-instability (MSI) and PD-L1 expression status was evaluated using immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor slides. All biomarker analyses, except MSI (performed on archived tissue as part of clinical care), were performed on fresh tumor biopsy samples collected pre-treatment (within 7 days prior to treatment initiation) and on-treatment (1 day prior to cycle 2 day 1) per protocol. Pathologists, blinded to clinical data, with expertise in PD-L1 assessment evaluated staining. PD-L1 was assessed using SP263 clone and reported as proportion of tumor cells expressing PD-L1. Tumor mutational burden (TMB), determined by whole-exome sequencing (WES) using standard protocol, was reported as number of somatic mutations per megabase (Mb) of captured region. Details are provided in supplement (Supplementary Methods 2). Fresh frozen tumor blocks with adequate tumor content were used to extract DNA and RNA. Samples meeting prespecified quantity/quality criteria underwent WES and RNA sequencing on Illumina Hi-seq platform. Gene-expression scores were calculated for each patient using normalized RNA expression fitted to established signatures based on associations with following biology: immune-sensitivity, angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).(22–24) Patient were divided into high or low groups based on median gene-signature score for all patients. Multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) on FFPE was performed using an antibody panel to characterize cancer and subsets of tumor-associated immune cells using 10 markers on Opal chemistry and multispectral microscopy Vectra system. Expression of protein markers was examined using infiltrate density scores. Details are provided in supplement (Supplementary Methods 2).

Statistical Analyses

Patient who received at least one dose of AtezoBev were included in the primary safety and efficacy analysis. Data are reported as of April 15, 2020. Descriptive statistics were used. Clopper and Pearson method was used to calculate the exact 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for primary endpoint analysis and other proportions. Time to event outcomes (PFS and OS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Fisher’s-exact test or Chi-squared test (when appropriate) were used for comparing proportions across groups. Unpaired non-parametric Mann-Whitney (Wilcoxon rank sum) test was used to compare means (and medians) between two distinct groups. Details regarding statistical plan are provided in study protocol (Supplementary-Protocol). Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.6.3 (http://www.R-project.org), SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA).

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Efficacy of atezolizumab and bevacizumab vis-à-vis response rates and survival in advanced peritoneal mesothelioma previously treated with chemotherapy surpassed outcomes expected with conventional therapies. Biomarker analyses uncovered epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype as an important resistance mechanism and showcase the value and feasibility of performing translationally driven clinical trials in rare tumors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to first and foremost thank our patients, their families and caregivers for participating in this trial. We thank all site personnel (including Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology (GIMO) research and regulatory team [Alma Delagarza, Christina J. Williams, Kimberly D. Ross, Laurel Deaton, Marily Elopre, Mari Gray, Michelle Escano, Shaelynn Riley, Shanequa Manuel, Tracy Trevino], clinical pharmacists and other clinical staff) for clinical trial support; William Betsy for coordinating trial logistics and regulatory provisions; Arvind Dasari, MD (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, U.S.A.) and Jonathan Loree, MD (BC Cancer, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) for critical review of the manuscript and input, and the Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation whose patient travel grant program assisted some patients with travel and housing costs. This study was supported by the NIH CCSG Award (CA016672 (Institutional Tissue Bank (ITB) and Research Histology Core Laboratory (RHCL)), Adaptive Patient-Oriented Longitudinal Learning and Optimization (APOLLO) Moonshot Program, Strategic Alliances and the Translational Molecular Pathology-Immunoprofiling lab (TMP-IL) at the Department Translational Molecular Pathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. We would like to acknowledge the support staff Grace Mathew, Wenhua Lang (APOLLO); Celia Garcia-Prieto, Liren Zhang, Julia Mendoza-Perez (Strategic alliance); Wei Lu, Jianling Zhou (IHC lab technician); Mei Jiang, Auriole Tamegnon (Multiplex lab technician); Renganayaki Krishna Pandurengan, Shanyu Zhang (Data consolidation) and Beatriz Sanchez-Espiridion, Sandesh Subramanya (TMP-IL) for their support to the translational analyses.

Financial support:

This research was funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech and the NIH CCSG Award (P30 CA016672).

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement:

KR reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, and Seattle Genetics and research support from Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Genentech/Roche, Guardant Health, Lilly, and Medimmune outside the submitted work. MO reports personal fees from Jansen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Abbvie, Medimmune, and Takeda and research support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Nouscom, Medimmune, and Genentech/Roche outside the submitted work. IW reports personal fees from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca/Medimmune, Pfizer, Merck, HTG Molecular, GlaxoSmithKline, Guardant Health, and MSD and research support from Genentech/Roche, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca/Medimmune, HTG Molecular, Guardant Health, Oncoplex, DepArray, Adaptive, Adaptimmune, EMD Serono, Takeda, Amgen, Karus, Johnson & Johnson, Iovance, 4D, Novartis, Oncocyte, Akoya outside the submitted work. SK reports personal fees from Genentech/Roche, Merck, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Amal Therapeutics, Navire Pharma, Symphogen, Holy Stone, Biocartis, Amgen, Novartis, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Biomedical, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Bayer, Pierre Fabre, EMD Serono, Redx Pharma, Jacobio, Natera, Repare Therapeutics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Lutris, Pfizer, Ipsen, and HalioDx outside the submitted work. JY reports grants and personal fees from Novartis outside the submitted work. DH reports research support from Genentech/Roche during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Advanced Accelerator Applications, Ipsen, Lexicon, ITM, Curium, and Abbvie and research support from Tarveda Therapeutics, ThermoFisher Scientific, Novartis, and Advanced Accelerator Applications outside the submitted work. PC, EM, CY, SD, KS, and WD are full-time employees of and have received stock/stock options from F Hoffmann-La Roche/Genentech. SL, AW, MK, SF, AM, SP, RER, CPS, PM, AF, DM, LS, EP, HC, PV, AV, ARM, AKM, KF, SW, and GV have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- 95%CI

95% confidence interval

- AEs

Adverse events

- AtezoBev

Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab

- CCS

Completeness of cytoreduction score

- CR

Complete response

- CRS

Cytoreductive surgery

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTCAEv4.0

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events-version4.0

- DCR

Disease control rate

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- DoR

Duration of response

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EPIC

Early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- HIPEC

Hyperthermic intraoperative peritoneal perfusion with chemotherapy

- ICI

Immune-checkpoint inhibition

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- imRECIST

Immune-modified RECIST

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- IRR

Independent radiology review

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- Mb

Megabase

- mIF

Multiplex immunofluorescence

- MMR

Mismatch-repair

- MPeM

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma

- MPM

Malignant pleural mesothelioma

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MSI

Microsatellite instability

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NR

Not reached

- OR

Odds-ratio

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progressive disease

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- RECISTv1.1

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors-version1.1

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- SD

Stable disease

- Seq

Sequencing

- TMB

Tumor mutational burden

- TRAEs

Treatment-emergent adverse events

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

References

- 1.Rodriguez D, Cheung MC, Housri N, Koniaris LG. Malignant abdominal mesothelioma: defining the role of surgery. J Surg Oncol 2009;99(1):51–7 doi 10.1002/jso.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis CE, Kramer JL, Jemal A. The burden of rare cancers in the United States. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2017;67(4):261–72 doi 10.3322/caac.21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consonni D, Calvi C, De Matteis S, Mirabelli D, Landi MT, Caporaso NE, et al. Peritoneal mesothelioma and asbestos exposure: a population-based case-control study in Lombardy, Italy. Occupational and environmental medicine 2019;76(8):545–53 doi 10.1136/oemed-2019-105826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borczuk AC, Pei J, Taub RN, Levy B, Nahum O, Chen J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of abdominal and pleural malignant mesothelioma with DNA arrays reveals both common and distinct regions of copy number alteration. Cancer Biol Ther 2016;17(3):328–35 doi 10.1080/15384047.2016.1145850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeda M, Kasai T, Enomoto Y, Takano M, Morita K, Nakai T, et al. Comparison of genomic abnormality in malignant mesothelioma by the site of origin. J Clin Pathol 2014;67(12):1038–43 doi 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bijelic L, Darcy K, Stodghill J, Tian C, Cannon T. Predictors and Outcomes of Surgery in Peritoneal Mesothelioma: an Analysis of 2000 Patients from the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27(8):2974–82 doi 10.1245/s10434-019-08138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chicago Consensus Working G The Chicago Consensus on peritoneal surface malignancies: Management of peritoneal mesothelioma. Cancer 2020;126(11):2547–52 doi 10.1002/cncr.32870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusamura S, Kepenekian V, Villeneuve L, Lurvink RJ, Govaerts K, De Hingh I, et al. Peritoneal mesothelioma: PSOGI/EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(1):36–59 doi 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janne PA, Wozniak AJ, Belani CP, Keohan ML, Ross HJ, Polikoff JA, et al. Open-label study of pemetrexed alone or in combination with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with peritoneal mesothelioma: outcomes of an expanded access program. Clinical lung cancer 2005;7(1):40–6 doi 10.3816/CLC.2005.n.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carteni G, Manegold C, Garcia GM, Siena S, Zielinski CC, Amadori D, et al. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma-Results from the International Expanded Access Program using pemetrexed alone or in combination with a platinum agent. Lung cancer 2009;64(2):211–8 doi 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judge S, Thomas P, Govindarajan V, Sharma P, Loggie B. Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: Characterization of the Inflammatory Response in the Tumor Microenvironment. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23(5):1496–500 doi 10.1245/s10434-015-4965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tazzari M, Brich S, Tuccitto A, Bozzi F, Beretta V, Spagnuolo RD, et al. Complex Immune Contextures Characterise Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma: Loss of Adaptive Immunological Signature in the More Aggressive Histological Types. J Immunol Res 2018;2018:5804230 doi 10.1155/2018/5804230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapel DB, Stewart R, Furtado LV, Husain AN, Krausz T, Deftereos G. Tumor PD-L1 expression in malignant pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma by Dako PD-L1 22C3 pharmDx and Dako PD-L1 28-8 pharmDx assays. Hum Pathol 2019;87:11–7 doi 10.1016/j.humpath.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai A, Karrison T, Rose B, Tan Y, Hill B, Pemberton E, et al. OA08.03 Phase II Trial of Pembrolizumab (NCT02399371) In Previously-Treated Malignant Mesothelioma (MM): Final Analysis. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2018;13(10):S339 doi 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popat S, Curioni-Fontecedro A, Dafni U, Shah R, O’Brien M, Pope A, et al. A multicentre randomised phase III trial comparing pembrolizumab versus single-agent chemotherapy for advanced pre-treated malignant pleural mesothelioma: the European Thoracic Oncology Platform (ETOP 9-15) PROMISE-meso trial. Ann Oncol 2020;31(12):1734–45 doi 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baas P, Scherpereel A, Nowak AK, Fujimoto N, Peters S, Tsao AS, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;397(10272):375–86 doi 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards JG, Cox G, Andi A, Jones JL, Walker RA, Waller DA, et al. Angiogenesis is an independent prognostic factor in malignant mesothelioma. Br J Cancer 2001;85(6):863–8 doi 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang ZR, Chen ZG, Du XM, Li Y. Apatinib Mesylate Inhibits the Proliferation and Metastasis of Epithelioid Malignant Peritoneal Mesothelioma In Vitro and In Vivo. Front Oncol 2020;10:585079 doi 10.3389/fonc.2020.585079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, et al. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med 1996;2(10):1096–103 doi 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15(5):325–40 doi 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020;382(20):1894–905 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Escudier B, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med 2018;24(6):749–57 doi 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franzini A, Baty F, Macovei II, Durr O, Droege C, Betticher D, et al. Gene Expression Signatures Predictive of Bevacizumab/Erlotinib Therapeutic Benefit in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients (SAKK 19/05 trial). Clin Cancer Res 2015;21(23):5253–63 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JC, Hwang WT, Davis C, Deshpande C, Jeffries S, Rajpurohit Y, et al. Gene signatures of tumor inflammation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) predict responses to immune checkpoint blockade in lung cancer with high accuracy. Lung cancer 2020;139:1–8 doi 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kindler HL. Peritoneal mesothelioma: the site of origin matters. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting 2013:182–8 doi 10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zalcman G, Mazieres J, Margery J, Greillier L, Audigier-Valette C, Moro-Sibilot D, et al. Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;387(10026):1405–14 doi 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, Miya J, Wing MR, Chen HZ, et al. Landscape of Microsatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer Types. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;1: PO.17.00073 doi 10.1200/PO.17.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsimafeyeu I, Imyanitov E, Zavalishina L, Raskin G, Povilaitite P, Savelov N, et al. Agreement between PDL1 immunohistochemistry assays and polymerase chain reaction in non-small cell lung cancer: CLOVER comparison study. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):3928 doi 10.1038/s41598-020-60950-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Reynies A, Jaurand MC, Renier A, Couchy G, Hysi I, Elarouci N, et al. Molecular classification of malignant pleural mesothelioma: identification of a poor prognosis subgroup linked to the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20(5):1323–34 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blum Y, Meiller C, Quetel L, Elarouci N, Ayadi M, Tashtanbaeva D, et al. Dissecting heterogeneity in malignant pleural mesothelioma through histo-molecular gradients for clinical applications. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):1333 doi 10.1038/s41467-019-09307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alcala N, Mangiante L, Le-Stang N, Gustafson CE, Boyault S, Damiola F, et al. Redefining malignant pleural mesothelioma types as a continuum uncovers immune-vascular interactions. EBioMedicine 2019;48:191–202 doi 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.