Abstract

Introduction:

Inflammation is important in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) is associated with cardiovascular events and also predicts mortality in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Our goal was to determine the association between IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP on CAC progression and mortality in incident dialysis patients without prior coronary events.

Methods:

A prospective cohort of incident adult dialysis participants had CAC measured by an ECG-triggered multi-slide computed tomography (MSCT) scans at baseline and at least 12 months later. Lipids, mineral metabolism markers, FGF23, and inflammatory markers, such as IL-6 and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), were measured at the baseline visit.

Results:

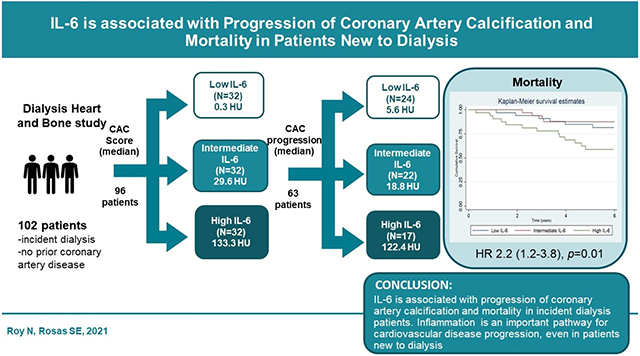

Participants in the high IL-6 tertile had the highest baseline CAC score [133.25 (10.35-466.15)] compared to the low [0.25 (0-212.2)] and moderate tertiles [29.55 (0-182.85)]. More than one-third of the participants with high IL-6 [15 of 32 (46.9%)] experienced progression of coronary artery calcification compared to participants with low [8 of 32 (25%)] and intermediate IL-6 levels [9 of 32 (28.1%)] (p=0.05). Each log increase in IL-6 was associated with increase in death (hazard ratio 2.2, 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.8; p= 0.01). After adjusting for smoking, age, gender, race, diabetes, phosphate and baseline calcium score, IL-6 (log) was associated with 2.2 times (95% CI, 1.1 to 4.6; p= 0.03) increase in death.

Conclusion:

IL-6 is associated with progression of coronary artery calcification and mortality in incident dialysis patients.

Keywords: IL-6, FGF23, hsCRP, Coronary artery calcification, Dialysis

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) can cause death in patients on dialysis. Presence of arterial calcification predicts cardiovascular mortality in stable individuals on dialysis [1]. Coronary artery calcification (CAC) which is highly prevalent in the hemodialysis (HD) population, is associated with inflammation [2], and predicts mortality in long-term hemodialysis patients [3].

Inflammation plays a major role in atherosclerosis. During injury, inflammatory mediators attach to the endothelium, which promotes atherothrombosis [4]. Individuals on dialysis have increased levels of inflammatory markers [5]. Inflammation independently increases the cardiovascular risk and mortality in individuals on chronic hemodialysis [6]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) predicts increased CAC severity [7]. An elevated IL-6 and calcium score were significantly associated with a 5-year risk of all-cause mortality in patients with CKD [8]. Elevated IL-6 was also associated with cardiovascular events and also predicted mortality in dialysis patients [9].

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), as well as inflammatory markers such as high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), and IL-6, have been associated with the presence of CAC [10-12]. We previously found serum FGF23 to be strongly associated with CAC progression [10]. These findings have been confirmed by other studies in CKD and HD populations. [13, 14]. In addition, FGF23 has been associated with increased mortality among incident and long-term dialysis participants [15, 16]. Serum CRP can also contribute to vessel wall calcification in hemodialysis patients and is associated with CAC progression [17]. Recently, IL-6 inhibitors such as ziltivekimab have been shown to reduce biomarkers of thrombosis and inflammation in patients with CKD [18].

We hypothesized that inflammation is the main driver of CAC progression. Our goal was to determine the association between IL-6, FGF23, and hsCRP on CAC progression and mortality in incident dialysis patients without prior coronary events in the Dialysis, Heart, and Bone (DHB) study.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

We investigated 96 participants on incident dialysis who had their CAC scan and IL-6 measured at baseline. Participants were excluded if they weighed more than 350 pounds (for technical reasons), were institutionalized (nursing home or prisoner), unable or unwilling to provide written informed consent, had a prior history of coronary artery disease (CAD) including coronary revascularization procedures, had a life expectancy of less than two years as judged by their primary physician, or had received an organ transplant. Subjects were identified by the investigators at each dialysis facility or by their primary nephrologist. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study, and the institutional review board approved the protocol.

DATA COLLECTION

At the baseline visit, information regarding demographics and medical history was obtained. All medications were recorded. Parathyroid hormone, phosphate, vitamin D, calcium, FGF23, and inflammatory markers (IL-6, hsCRP) were measured at the baseline visit. Lipid profile (HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides) was measured at baseline.

Plasma IL-6 levels was measured using high-sensitivity sandwich ELISA (Quantikine HS; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The samples were stored at −80°C, and assays were performed at the time of initial thawing. The lower detection limits for IL-6 was 0.07 pg/ml and the coefficient of variation was 13%. FGF-23 was measured in duplicate after a single thaw of stored baseline plasma specimens using a second generation C-terminal ELISA (Immutopics). The total inter and intra-assay coefficient of variability was 7.6% at 308 relative units (RU)/ml. The assay detects both intact FGF- 23 and its C-terminal fragments. HsCRP was measured in plasma samples using specific laser-based immunonephelometric methods on the BNII (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL).

For each subject, CAC was measured by an ECG-triggered multi-slide computed tomography (MSCT) scan at the baseline and follow-up visit at least twelve months later and was reported as Agatston score (AS). Sixty three participants had both follow-up scan and IL-6 measured at baseline. Individuals that had a coronary artery procedure, such as bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention prior to the follow-up scan, were, for technical reasons, not eligible for a scan at the follow-up visit. Seven participants had renal transplantation, seven died, and three had coronary revascularization procedures prior to their follow-up visit making them ineligible for the follow-up study CT. CAC was calculated using AS and calcium volume score (VS). CAC progression was measured continuously by the difference in score between CT/time between CT. We also evaluated CAC progression dichotomously using the square root difference (SQRT) in CAC volume at week 48 [19]. Progressors were defined as those with a difference in volume greater than or equal to 2.5 mm3.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For descriptive analyses, we stratified the population according to tertiles of IL-6 levels. IL-6 tertile 1 (<2.24 pg/ml), tertile 2 (2.24- 4.06 pg/ml) and tertile 3 (>4.06 pg/ml). Race was defined as African Americans and non- African Americans. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. We tested the differences in continuous variables between IL-6 tertiles using ANOVA and in categorical variables using the chi-squared test.

We also stratified the population based on IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP tertiles. The participants were divided into 3 groups (low, intermediate and high) based on their IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP levels. We used the Pearson correlation to evaluate the relationship between IL-6, CAC score, and other inflammatory markers. Baseline CAC score was log transformed because of its non-normal distribution. IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP were also natural log transformed to achieve normality when used as continuous variable. We used multivariate linear regression to assess whether IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP at baseline were independent predictors of baseline CAC score and annual CAC progression, defined by both the annual change in Agatston score and the SQRT method. The following covariates were adjusted for in the multivariable model: age, gender, race, diabetes status, phosphate, smoking status, and baseline CAC score.

We used Cox proportional hazard models with backward elimination to determine if IL-6 predicted mortality after adjusting for several a priori risk factors as well as risk factors with a p-value <0.1 in Table 1. The following covariates were included in the final model: smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), and baseline calcium score. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate the cumulative death rate. Differences in survival were analyzed using the log-rank test. Results were considered statistically significant if the corresponding p-value was less or equal to 0.05. We used STATA, version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) to perform the analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic and physiologic characteristics for all participants and by tertiles of serum IL-6

| Characteristic | All Participants (n=96) |

IL-6 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n=32) | Intermediate (n=32) |

High (n=32) | |||

| Demographic | |||||

| Age a (yr) | 50.4 (±12.8) | 46.6 (±13.8) | 50.8 (±12.7) | 53.7 (±11.2) | 0.08 |

| Woman (%) | 31.25 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 37.5 | 0.65 |

| African American (%) | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 0.67 |

| Baseline | |||||

| DM (%) | 52.7 | 50 | 40.6 | 68.9 | 0.08 |

| CVD (%) | 25 | 15.6 | 25 | 34.4 | 0.22 |

| Ever smoker (%) | 52.7 | 53.1 | 59.4 | 44.8 | 0.52 |

| BMI a (kg/m2) | 29.4 (±5.9) | 27.7 (±4.9) | 31.1 (±6.6) | 29.3 (±5.6) | 0.07 |

| SBP a (mmHg) | 136.7 (±20.6) | 139.9 (±19.7) | 135.8 (±22.6) | 134.4 (±19.7) | 0.55 |

| DBP a (mmHg) | 77.8 (±12.1) | 78.3 (±11.4) | 80.0 (±12.5) | 75.1 (±12.2) | 0.25 |

| Laboratory assessment | |||||

| Total Cholesterol a (mg/dl) | 169.3 (37.6) | 179.9 (39.6) | 170 (31.5) | 157.8 (39.1) | 0.06 |

| PTH a (pg/ml) | 251.1 (208.3) | 240.9 (213.0) | 298.2 (272.1) | 214.1 (98.3) | 0.26 |

| Vitamin D a | 25.7 (15.1) | 27.6 (12.9) | 25.6 (16.5) | 23.9 (15.8) | 0.62 |

| Phosphate a (mg/dl) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.4) | 4.3 (1.2) | 0.43 |

| Calcium a (mg/dl) | 8.8 (1.1) | 8.9 (1.1) | 8.9 (1.0) | 8.5 (1.1) | 0.15 |

| Albumin a (g/dl) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.5) | 0.02 |

| Median hsCRP (mg/L) (IQR) | 6.4 (2.7-13.9) | 3.5 (0.6-4.8) | 6.6 (2.7-12.4) | 13.8 (8.1-30.3) | 0.002 |

| Median TNF-α (pg/ml) (IQR) | 4.1 (3.0-5.4) | 3.5 (2.9-4.5) | 3.9 (2.9-4.9) | 4.9 (3.8-6.7) | 0.11 |

| Median FGF-23 (RU/ml) (IQR) | 1195.6 (509.7-2216.9) | 1527.7 (629.0-3565.5) | 810.0 (437.1-1624.9) | 1205.5 (723.9-2240.6) | 0.26 |

| Median Baseline CAC score (IQR) | 43.4 (0-292.4) | 0.3 (0-212.2) | 29.6 (0-182.9) | 133.3 (10.4-466.2) | 0.02 |

| Medications | |||||

| Beta blocker (%) | 65.9 | 60 | 71.9 | 65.5 | 0.61 |

| ACE/ARB (%) | 48.4 | 56.7 | 50.0 | 37.9 | 0.35 |

| Diuretic (%) | 39.6 | 40 | 37.5 | 41.4 | 0.95 |

| CCB (%) | 60.4 | 66.7 | 46.9 | 68.9 | 0.15 |

| Nitrates (%) | 14.3 | 13.3 | 3.1 | 27.6 | 0.02 |

| Alpha Blocker (%) | 25.3 | 16.7 | 28.1 | 31.0 | 0.40 |

| Statins (%) | 35.4 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 31.3 | 0.83 |

| Aspirin (%) | 29.7 | 16.7 | 37.5 | 34.5 | 0.16 |

Note: Due to missing values, total may not always equal 96.

Mean (SD)

RESULT

Table 1 shows the demographic and comorbidities stratified by the IL-6 tertiles. The mean age of participants was 50.4 ± 12.8 years. A third of participants were women, and 62.5% were African Americans. IL-6 correlated directly with hsCRP (r=0.52), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (r=0.23), and fibrinogen (r=0.34) [p<0.05 for each]. Table 2 demonstrates IL-6, FGF-23 and hsCRP analyzed by CAC categories.

Table 2.

IL-6, FGF-23 and hsCRP analyzed by CAC categories.

| CAC category | No (%) | IL-6 (pg/mL) | FGF-23 (pg/mL) | hsCRP (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC score=0 | 34 (35.4) | 2.4 (1.6- 3.9)* | 1436.8 (560.7- 2216.2) | 6.7 (3.0- 11.6) |

| CAC score 1-100 | 24 (25) | 3.3 (2.1- 6.7) | 918.8 (428.9 – 2083.6) | 6.4 (2.1- 15.2) |

| CAC score >100 | 38 (39.6) | 3.9 (2.3- 6.2) | 1124.3 (515.2 – 2267.2) | 6.1 (2.9 – 15.2 |

p < 0.05

Values expressed as Median (IQR)

Coronary artery calcification presence

The baseline median IL-6 level was 3.1 mg/L [interquartile range (IQR), 1.97-5.86] and was associated with baseline CAC [0.45 (0.17), p=0.01] after adjustment for known CAC risk factors, such as age, race, gender, smoking, phosphate, and diabetes mellitus. CAC score increased by IL-6 tertile (p=0.02). Individuals in the high IL-6 tertile had the highest baseline CAC score [133.25 (10.35-466.15)] compared to the low [0.25 (0-212.2)] and intermediate tertiles [29.55 (0-182.85)]. The Pearson correlation between IL-6 and baseline CAC score was 0.19, p = 0.07.

Coronary artery calcification progression

Almost half of the participants with high IL-6 [15 of 32 (46.9%)] experienced progression of coronary artery calcification compared to participants with low [8 of 32 (25%)] and intermediate IL-6 levels [9 of 32 (28.1%)] (p=0.05). Participants in the high IL-6 tertile had the highest absolute annual CAC score change [122.4 (9.4-447.7)] compared to the low [5.6 (0-70.9)] and moderate tertiles [18.8 (0-125.2)] (p=0.02). The Pearson correlation between IL-6 and annual progression of calcium score was 0.51, p<0.001.

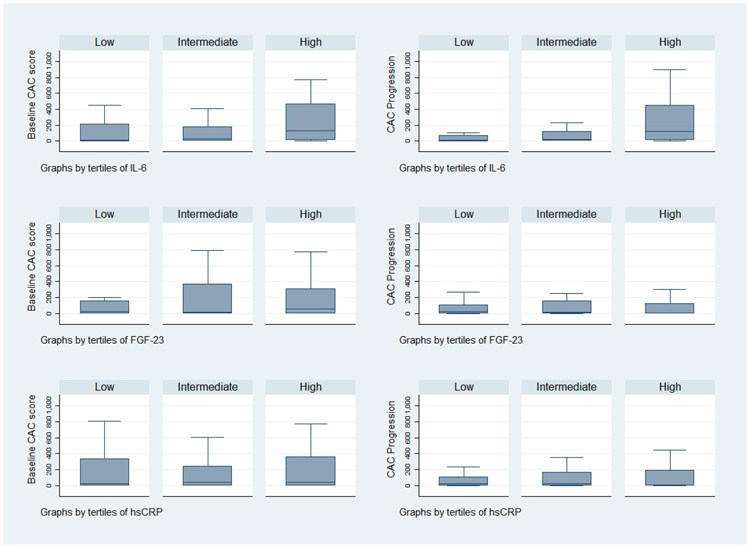

Figure 1 depicts IL-6, FGF23, and hsCRP stratified by baseline and annual progression of CAC score. In multivariable models adjusted for baseline CAC (log), age, smoking, diabetes, race, phosphorus, and gender, IL-6 (log) was an independent risk factor for CAC progression (coefficient 208.77 (91.15); p=0.03). Therefore, there was a 208.77 AU change in CAC score per 1-log change in IL-6 (Table 4). When FGF23 was included in the model, there was only mild modification of the coefficient for IL-6 (178.92 (88.08); p = 0.05). FGF23 (log) was also significant in this model (169.11 (69.27); p = 0.02). Similar results were found using the volume score. When hsCRP (log) was included in the model, IL-6 was not significant. Table 4 demonstrates the association of CAC progression with each log change and tertiles of IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP.

Fig 1.

IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP tertiles stratified by baseline and annual progression of CAC score (HU)

p < 0.05 for IL-6

Table 4.

Association of CAC Progression with different tertiles of IL-6, FGF23 and hsCRP biomarker group.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted a | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC Progressi on |

IL-6 | FGF23 | hsCRP | IL-6 | FGF23 | hsCRP | ||||||||||||

| CE | SE | P value | CE | SE |

P value |

CE | SE | P value | CE | SE |

P value |

CE | SE |

P value |

CE | SE | P value | |

| Annual CAC score change | ||||||||||||||||||

| Continuo us (log) | 271.0 | 84.6 | 0.002 | 98.74 | 66.5 | 0.14 | 84.86 | 42.37 | 0.05 | 208.8 | 91.1 | 0.03 | 188.6 | 70.6 | 0.01 | 79.99 | 42.54 | 0.07 |

| Low | Ref | |||||||||||||||||

| Intermediate (n=32) |

20.9 | 146.3 | 0.89 | 124.8 | 156.3 | 0.43 | 69.9 | 167.0 | 0.68 | −33.1 | 146.9 | 0.82 | 303.8 | 164.5 | 0.07 | 33.8 | 161.3 | 0.84 |

| High | 428.6 | 157.1 | 0.008 | 204.5 | 164.9 | 0.22 | 266.8 | 154.4 | 0.09 | 291.1 | 175.9 | 0.10 | 468.9 | 179.9 | 0.01 | 277.3 | 154.9 | 0.08 |

| Square root difference of volume change | ||||||||||||||||||

| Continuous (log) | 3.2 | 0.9 | 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.18 | 0.87 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.02 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.46 | 0.09 |

| Low | Ref | |||||||||||||||||

| Intermediate | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.68 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.29 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 0.03 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.69 |

| High | 6.4 | 1.7 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.46 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.13 | 4.6 | 1.9 | 0.02 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 0.04 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.16 |

Adjusted for baseline CAC, age, race, gender, smoking status, phosphate and diabetes status

Mortality

Twenty-four percent of the participants died during an average follow-up of 5 (1.5) years. Forty one percent of the participants in the high IL-6 group died as compared to 12.5% and 15.6% participants in the intermediate and low IL-6 groups (p=0.01), respectively. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve stratified by IL-6, FGF-23 and hsCRP tertiles. Each log increase in IL-6 was associated with increase in death (hazard ratio 2.2, 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.8; p= 0.01). After adjusting for smoking, age, gender, race, DM, phosphate, and baseline calcium score, IL-6 (log) was associated with 2.2 times (95% CI, 1.1 to 4.6; p= 0.03) increase in death.

Fig 2-.

Kaplan Meier Survival Curve stratified by IL-6, FGF-23 and hsCRP tertiles

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the relationship between IL-6, FGF23, hsCRP, coronary artery calcification, and mortality in incident dialysis participants without prior coronary artery events. We found that participants with high IL-6 had higher CAC score and CAC progression. Serum IL-6 and FGF23 were independently associated with CAC progression. We also found that an increase in IL-6 was associated with an increase in mortality in this population.

Inflammation and CVD are interrelated, each contributing to the high mortality of dialysis patients and potentially increasing the risk in a stepwise manner [20]. In vitro and animal studies have shown that inflammation leads to the osteochondrogenic transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells and promotes calcification [21].

IL-6 plays a major role in inflammation. IL-6 is a mediator of acute phase response, which is associated with increased blood viscosity and increased number and activity of platelets. CKD is a state of low-grade systemic inflammation [21]. Polymorphism in the IL-6 gene may be causally involved in high cardiovascular (CV) risk in patients with CKD [22] and also acts as a promoter of atherosclerosis [23, 24]. In several studies of HD patients, elevated serum IL-6 levels have been implicated to have a potential role in aortic stiffness and calcification [25, 26]. In another study of 45 ESRD patients, Jogestrand et al. reported that IL-6 is an independent predictor of the progression of carotid atherosclerosis in patients on dialysis for 12 months [27]. Similarly, a study of 43 participants treated on peritoneal dialysis (PD) showed that participants with greater CAC score had significantly greater levels of IL-6 [28], and suggested that their findings may support the role of inflammation in the process of vessel wall calcification.

Our results support inflammation as a risk factor for mortality in new dialysis patients, who do not have a history of prior coronary events. High IL-6 has been associated with mortality in patients on long-term dialysis [9, 22, 29-31]. In a study of 173 ESKD patients near the initiation of dialysis and followed for a mean period of 3.1 years, elevated IL-6 predicted mortality and underlined the importance of inflammation as an unfavorable prognostic factor in ESKD patients [9]. This study also demonstrated that these outcomes were similar in both HD and PD patients.

IL-6 has also been proposed as an indicator of severity of inflammation and death in ESKD patients. IL-6 was the biomarker associated with an increased relative risk for mortality in ESKD patients on dialysis [22, 29]. In individuals with stage 5 CKD on incident dialysis, IL-6 was a strong independent predictor of all-cause mortality (HR 1.79 (95% CI, 1.20 to 2.67) [32]. We demonstrate that individuals with inflammatory milieu are more likely to have CAC progression.

In our previous study, high FGF23 was an independent predictor of CAC progression in incident dialysis participants without a history of CAD [10]. Similar results were reported by Ozkok et al. in their study of 74 HD patients [14]. A study done on peritoneal dialysis patients showed a correlation between CAC and CRP levels [28]. High CRP levels was associated with progression of coronary artery calcification in patients on hemodialysis [33]. Our study did not show similar results.

Medications that are commonly administered in the CKD population have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects and to decrease IL-6 levels [34, 35]. In the CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study) trial, participants with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 randomly allocated to canakinumab which blocks interleukin-1β an inducer of IL-6, reduced adverse cardiovascular events (hazard ratio: 0.82; 95% confidence interval: 0.68 to 1.00; p = 0.05) with the greatest benefit seen among those whose hsCRP levels were below 2 mg/l but did not find any beneficial effects with renal function [36, 37]. Another trial on Ziltivekimab (an anti-interleukin-6 ligand monoclonal antibody) performed on participants with moderate to severe CKD demonstrated a significant reduction in the biomarkers of inflammation and thrombosis [18]. Therefore, there is interest in the outcome of an ongoing 6200 participant trial [Ziltivekimab Cardiovascular Outcomes Study (ZEUS)] addressing whether IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab can improve CV outcomes and slow renal disease progression in patients with stage 3 to 5 CKD [38]. In our study, nitrate users exhibited lower baseline IL-6 concentration. Patients prescribed statins, ASA, and ACE/ angiotension receptor blocker (ARB) inhibitor therapy were more likely to be in the low IL-6 group, but it did not have a statistically significant influence. Different therapeutic approaches that target reduction of IL-6 could be considered in reducing CVD risk and mortality.

Our study has several strengths, such as the use of a well-characterized, multiracial cohort with serial measurements of CAC and the prospective participation of the incident dialysis cohort without CAD history. However, we acknowledge several limitations with our study. Our cohort is relatively small and biomarkers were measured only once. We also had a relatively small percentage of PD participants. Since the study is observational, there are also potentially unknown and unmeasured confounders. Finally, we used all-cause mortality as the primary outcome, as cause of death was not always available. To our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the relationship between IL-6, FGF23, hsCRP, CAC progression, and mortality in incident dialysis participants.

This study demonstrates that inflammation is an important pathway for cardiovascular disease progression, even in patients on dialysis without a history of coronary events. Inflammatory markers can be used in clinical practice for earlier identification of patients at risk for CVD and death. We should find ways to decrease inflammation in our patients that include diet, glucose control, medications, and increased physical activity, among other efforts. In addition, future studies should assess whether curbing inflammation reduces cardiovascular events and improves survival in these high-risk patients.

Table 3.

Association of baseline factors with baseline coronary arterial calcification and progression of calcification by Agatston and calcium volume scores.

| Variable | Baseline CAC | CAC Progression | CAC progression by Calcium Volume Score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient ±SE |

P value | Coefficient ±SE |

P value | Coefficient ±SE |

P value | |

| Age | 0.03±0.02 | 0.11 | 4.98±6.18 | 0.42 | 0.1±0.07 | 0.13 |

| Female sex | −0.06±0.48 | 0.9 | −169.36±123.38 | 0.18 | −2.06±1.34 | 0.13 |

| African Americans | −0.98±0.49 | 0.05 | 128.17±137.22 | 0.36 | 2.15±1.5 | 0.16 |

| Diabetes Status | 1.47±0.48 | 0.003 | 61.35±132.20 | 0.65 | 1.62±1.44 | 0.27 |

| Ever Smoker | 2.03±0.5 | <0.001 | 5.03±149.06 | 0.97 | −1.48±1.62 | 0.37 |

| Baseline CAC (log) | - | - | 41.55±30.09 | 0.17 | 0.50±0.33 | 0.14 |

| Serum phosphate | −0.41±0.19 | 0.04 | −92.14±58.29 | 0.12 | −0.58±0.63 | 0.36 |

| IL-6 (log) | 0.74±0.31 | 0.02 | 177.38±88.97 | 0.05 | 2.01±0.97 | 0.04 |

| FGF-23 (log) | 0.40±0.25 | 0.11 | 174.52±71.96 | 0.02 | 1.86±0.78 | 0.02 |

Models adjusted for age, gender, race, smoking status, diabetes status, serum phosphate, FGF23 and IL-6.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants R21 HL 086971. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the paper for publication. We would like to thank the research coordinators and patients involved in this study. We would like to thank Camille Johansen for language editing and proofreading.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

S.E. Rosas reports attending one scientific advisory board each for Relypsa and Reata for which she was compensated. She has received grant support from NIDDK, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, and is about to start a study with MedImmune Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of AstraZeneca AB; both are clinical trials related to diabetic nephropathy.

N Roy received salary support from the NIDDK, Bayer Pharmaceuticals and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Blacher J, et al. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension, 2001. 38(4): p. 938–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barreto DV, et al. Coronary calcification in hemodialysis patients: the contribution of traditional and uremia-related risk factors. Kidney Int, 2005. 67(4): p. 1576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shantouf RS, et al. Total and individual coronary artery calcium scores as independent predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol, 2010. 31(5): p. 419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willerson JT and Ridker PM, Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. Circulation, 2004. 109(21 Suppl 1): p. II2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobo G, Lindholm B, and Stenvinkel P, Chronic inflammation in end-stage renal disease and dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2018. 33(suppl_3): p. iii35–iii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann J, et al. Inflammation enhances cardiovascular risk and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int, 1999. 55(2): p. 648–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen BA, et al. Adipokines and severity and progression of coronary artery calcium: Findings from the Rancho Bernardo Study. Atherosclerosis, 2017. 265: p. 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaminska J, et al. IL 6 but not TNF is linked to coronary artery calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. Cytokine, 2019. 120: p. 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pecoits-Filho R, et al. Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of mortality in patients starting dialysis treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2002. 17(9): p. 1684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan AM, et al. FGF-23 and the progression of coronary arterial calcification in patients new to dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2012. 7(12): p. 2017–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danesh J, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med, 2004. 350(14): p. 1387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridker PM, Stampfer MJ, and Rifai N, Novel risk factors for systemic atherosclerosis: a comparison of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, homocysteine, lipoprotein(a), and standard cholesterol screening as predictors of peripheral arterial disease. JAMA, 2001. 285(19): p. 2481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scialla JJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular events in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2014. 25(2): p. 349–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozkok A, et al. FGF-23 associated with the progression of coronary artery calcification in hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol, 2013. 14: p. 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez OM, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med, 2008. 359(6): p. 584–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jean G, et al. High levels of serum fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 are associated with increased mortality in long haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2009. 24(9): p. 2792–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brancaccio D, et al. Inflammation, CRP, calcium overload and a high calcium-phosphate product: a "liaison dangereuse". Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2002. 17(2): p. 201–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM, et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet, 2021. 397(10289): p. 2060–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hokanson JE, et al. Evaluating changes in coronary artery calcium: an analytic method that accounts for interscan variability. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2004. 182(5): p. 1327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qureshi AR, et al. Inflammation, malnutrition, and cardiac disease as predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2002. 13 Suppl 1: p. S28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henaut L and Massy ZA, New insights into the key role of interleukin 6 in vascular calcification of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2018. 33(4): p. 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoccali C, Tripepi G, and Mallamaci F, Dissecting inflammation in ESRD: do cytokines and C-reactive protein have a complementary prognostic value for mortality in dialysis patients? J Am Soc Nephrol, 2006. 17(12 Suppl 3): p. S169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphries SE, et al. The interleukin-6 −174 G/C promoter polymorphism is associated with risk of coronary heart disease and systolic blood pressure in healthy men. Eur Heart J, 2001. 22(24): p. 2243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yudkin JS, et al. Inflammation, obesity, stress and coronary heart disease: is interleukin-6 the link? Atherosclerosis, 2000. 148(2): p. 209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desjardins MP, et al. Association of interleukin-6 with aortic stiffness in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Hypertens, 2018. 12(1): p. 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CT, et al. Biomarkers associated with vascular and valvular calcification in chronic hemodialysis patients. Dis Markers, 2013. 34(4): p. 229–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenvinkel P, Heimburger O, and Jogestrand T, Elevated interleukin-6 predicts progressive carotid artery atherosclerosis in dialysis patients: association with Chlamydia pneumoniae seropositivity. Am J Kidney Dis, 2002. 39(2): p. 274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stompor T, et al. An association between coronary artery calcification score, lipid profile, and selected markers of chronic inflammation in ESRD patients treated with peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis, 2003. 41(1): p. 203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honda H, et al. Serum albumin, C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and fetuin a as predictors of malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis, 2006. 47(1): p. 139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao M, et al. Plasma interleukin-6 predicts cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis, 2005. 45(2): p. 324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meuwese CL, et al. Trimestral variations of C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha are similarly associated with survival in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2011. 26(4): p. 1313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun J, et al. Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality Risk in Patients with Advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016. 11(7): p. 1163–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung HH, Kim SW, and Han H, Inflammation, mineral metabolism and progressive coronary artery calcification in patients on haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2006. 21(7): p. 1915–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibas M, et al. Influence of preventive therapy with quinapril on IL-6 level in patients with chronic stable angina. Pharmacol Rep, 2007. 59(3): p. 330–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radaelli A, et al. Inflammatory activation during coronary artery surgery and its dose-dependent modulation by statin/ACE-inhibitor combination. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2007. 27(12): p. 2750–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridker PM, et al. Inhibition of Interleukin-1beta by Canakinumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018. 71(21): p. 2405–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridker PM and Rane M, Interleukin-6 Signaling and Anti-Interleukin-6 Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res, 2021. 128(11): p. 1728–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridker PM Effects of Interleukin-6 Inhibition with Ziltivekimab on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Thrombosis Among Patients at High Atherosclerotic Risk: A Randomized, Double-Blind Phase 2 Trial. 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.