Abstract

GATA2 deficiency is a heterogeneous multi-system disorder characterized by a high risk of developing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and myeloid leukemia. We analyzed the outcome of 65 patients reported to the registry of the European Working Group (EWOG) of MDS in childhood carrying a germline GATA2 mutation (GATA2mut) who had undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). At 5 years the probability of overall survival and disease-free survival (DFS) was 75% and 70%, respectively. Non-relapse mortality and relapse equally contributed to treatment failure. There was no evidence of increased incidence of graft-versus-host-disease or excessive rates of infections or organ toxicities. Advanced disease and monosomy 7 (−7) were associated with worse outcome. Patients with refractory cytopenia of childhood (RCC) and normal karyotype showed an excellent outcome (DFS 90%) compared to RCC and −7 (DFS 67%). Comparing outcome of GATA2mut with GATA2wt patients, there was no difference in DFS in patients with RCC and normal karyotype. The same was true for patients with −7 across morphological subtypes. We demonstrate that HSCT outcome is independent of GATA2 germline mutations in pediatric MDS suggesting the application of standard MDS algorithms and protocols. Our data support considering HSCT early in the course of GATA2 deficiency in young individuals.

Subject terms: Stem-cell therapies, Paediatrics

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in young individuals consists of a heterogeneous group of hematopoietic disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, peripheral blood cytopenia, cellular dysplasia and a high risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In contrast to older adults, in whom MDS is associated with age-related somatic mutations, MDS in young patients is often associated with genetic syndromes predisposing to myeloid neoplasia. Next to the well-known inherited bone marrow failure syndromes like Fanconi anemia, Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, severe congenital neutropenia, or dyskeratosis congenita, a slew of predisposition syndromes involving genes like GATA2, SAMD9/SAMD9L, RUNX1, ANKRD26, ETV6, SRP72, ERCC6L2, and others have recently been uncovered [1–4].

Among these new genetic entities, GATA2 deficiency resulting from heterozygous germline mutations in the gene encoding the zinc-finger transcription factor GATA2 appears to be the most common predisposing condition for MDS in childhood [5, 6]. Although some patients with germline mutations in GATA2 (GATA2mut) have a positive family history, de novo germline mutations have been reported in a majority of children with GATA2mut MDS [6]. Despite the observation that the loss of B-cells is a common feature of GATA2 deficiency [7], children with GATA2 germline mutations often present as MDS without prior infections. In contrast, young adults often display a history of opportunistic infections, slowly progressing bone marrow failure, and subsequent transformation to AML.

The prevalence of myeloid neoplasia in GATA2 deficiency has been estimated to be 75%, with a median age at diagnosis of 19.7 years [8]. Studying a series of 79 GATA2mut patients, Donadieu described that more than 80% of patients had developed a hematological malignancy by the age of 40 years; progression from MDS to AML was observed in 16% [5]. Examining a cohort of over 600 individuals with MDS enrolled in the registries of the European Working Group of MDS in Childhood (EWOG-MDS), our group reported a prevalence of GATA2mut in 7% of all primary MDS and 15% in advanced primary MDS. GATA2 germline disease was associated with more advanced MDS type and often accompanied by monosomy 7 [6].

Allogeneic HSCT is the only curative therapy for hematological complications of GATA2 deficiency, and has been shown to eradicate clonal malignancy, restore normal hematopoiesis, clear underlying infections and improve pulmonary function. As GATA2 deficiency is a newly defined disease, HSCT strategies, as well as outcome, have yet to be fully elucidated. In particular, it is unclear whether applying guidelines for HSCT in pediatric MDS results in similar outcome. Most published reports refer to single-patient case studies, small series of primarily adult patients, or patients with immunodeficiency in the absence of clonal disease [9–15]. We have previously observed that 34 individuals with MDS, monosomy 7 and GATA2mut had a similar outcome compared to their counterparts with wildtype GATA2 (GATA2wt) [6]. Here we expand the analysis to an enlarged cohort with longer follow-up and provide a detailed review of HSCT in young individuals with GATA2 deficiency.

Methods

Study population

We identified 66 patients with MDS and GATA2 germline mutation prospectively enrolled for MDS in the EWOG-MDS registries (EWOG-MDS 98 #NCT00047268, EWOG-MDS 2006 #NCT00662090) who had undergone HSCT at an age of <20 years between 01/1997 and 11/2018. One patient was excluded from the analysis due to missing data. Genetic and/or clinical data from 50 patients had partially been included in previous publications [6, 16]. HSCT procedures had been performed in accordance with EWOG-MDS recommendations (www.ewog-mds-saa.org). MDS was classified based on the 2016 WHO classification for pediatric MDS, and included refractory cytopenia of childhood (RCC), MDS with excess blasts (MDS-EB), MDS-EB in transformation (MDS-EBt), and MDS-related acute myeloid leukemia (MDR-AML) [17]. One patient with myelofibrotic MDS and increased BM blasts was classified as MDS-EBt. Cytogenetic analysis was performed according to standard procedures and described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Karyotypes with sole monosomy 7, and monosomy 7 with one or two additional random aberrations were classified as monosomy 7 and analyzed in one group [18].

Molecular studies to identify GATA2 mutations were conducted as previously described [6, 16]. In patients enrolled before 2013 GATA2 testing was performed retrospectively, thereafter the diagnosis of MDS prompted GATA2 testing independent of the clinical presentation. For the analyses comparing GATA2mut to GATA2wt patients, we identified 404 GATA2wt MDS patients without known underlying predisposition (including SAMD9/L) who otherwise fulfilled the study criteria (Supplementary Fig. 1).

All studies were approved by the institutional ethics committees of the respective institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or patients’ guardians. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from HSCT to death or last follow-up, disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from HSCT to death, disease recurrence, or last follow-up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival rates, and the two-sided log-rank test was used to evaluate the equality of the survivorship functions in different subgroups. Time-to-event outcome for relapse and non-relapse mortality (NRM) were estimated using cumulative incidence curves, using relapse and NRM as the respective competing risks [19, 20]. Differences in the cumulative incidence functions among groups were compared using Gray’s test [21].

For the analyses comparing GATA2mut with GATA2wt patients the χ2 test was used to examine the statistical significance of the association between GATA2 status and categorized factors. Fisher’s exact test was calculated for 2 × 2 contingency analyses. Nonparametric statistics were used to test for differences in continuous variables in terms of mutational status (Mann–Whitney U test).

For multivariate analysis, a cause-specific Cox model was fitted, including all variables with P less than 0.1 in the univariate analysis for DFS [22]. The model included the GATA2 status, karyotype, and highest WHO-type. All P values were two-sided, and values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Software packages SPSS for Windows 25.0.0 (IBM Corp, New York, NY) and NCSS 2004 (NCSS, Kaysville, UT) were used.

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

The 65 children and adolescents with GATA2 deficiency had been diagnosed with RCC (n = 36), MDS-EB (n = 22), MDS-EBt (n = 6) or MDR-AML (1) at a median age of 12.8 (4.4–18.6) years. Karyotypes included monosomy 7 (n = 44), der (1;7) (n = 4), trisomy 8 (n = 4), random aberration (n = 1) or a normal karyotype (n = 12). Forty patients (71%) had additional non-hematological features of GATA2 deficiency (Table 1). Prior to HSCT, 16 patients had progressed to a more advanced stage of MDS and five had received AML-type chemotherapy, resulting in a BM blast count of <5% at the time of HSCT.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and transplantation procedure.

| Item | Specification | At diagnosis/prior to HSCT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||

| Patients | 65 | 100 | ||

| Gender | Male | 34 | 52 | |

| Female | 31 | 48 | ||

| Age at diagnosis of MDS | Years, median(range) | 12.8 (4.4–18.6) | ||

| GATA2 Type of mutation | Truncating | 43 | 66 | |

| Missense | 14 | 22 | ||

| Non-Coding Intron 4 | 4 | 6 | ||

| Synonymous | 3 | 5 | ||

| Whole gene deletion | 1 | 2 | ||

| MDS subtype at diagnosis | RCC | 36 | 55 | |

| MDS-EB | 22 | 34 | ||

| MDS-EBt/ MDR-AML | 6 /1 | 11 | ||

| Karyotype | Monosomy 7 | 44 | 68 | |

| Der (1;7) | 4 | 6 | ||

| Trisomy 8 | 4 | 6 | ||

| Normala | 12 | 19 | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||

| Non-Hematological features | Any | 40 | 71 | |

| Immunedeficiencyb | 24 | |||

| Lymphedema/ hydrocele | 13 | |||

| Deafness/hearing impairment | 8 | |||

| Urogenital malformations | 10 | |||

| Neurocognitive/ behavioral problems | 10 | |||

| Highest MDS subtype | ||||

| (prior to HSCT) | RCC | 27 | 42 | |

| MDS-EB | 23 | 35 | ||

| MDS-EBt/ MDR-AML | 10/5 | 23 | ||

| At HSCT | ||||

| Age at HSCT | Years, median (range) | 13.5 (4.6-19.9) | ||

| Interval MDS to HSCT | Months, median (range) | 5.6 (1.4 – 67) | ||

| Therapy prior to 1st HSCT | No therapy | 55 | 85 | |

| AML-type | 5 | 8 | ||

| other | 5 | 8 | ||

| BM blasts at HSCT | < 5% | 34 | 56 | |

| 5–19% | 19 | 31 | ||

| ≥ 20% | 8 | 13 | ||

| No data | 4 | |||

| HSCT procedure | ||||

| Donor | MSD | 17 | 26 | |

| MUD (10/10)/(9/10) | 24/6 | 46 | ||

| UD (6/6)/(5/6)/(8/10)c/ incomplete typing | 1/2/6/1 | 15 | ||

| MMFD | 8 | 12 | ||

| Stem cell source | BM | 37 | 57 | |

| PBSC | 19 | 29 | ||

| PBSC (T-cell depleted) | 8 | 12 | ||

| CB | 1 | 2 | ||

| Conditioning regimen | Busulfan- based | 35 | 54 | |

| Treosulfan-based | 21 | 32 | ||

| TBI-based | 5 | 8 | ||

| Other | 4 | 6 | ||

| GvHD prophylaxis | MSD (17) | CSA | 7 | |

| CSA/MTX | 7 | |||

| ATG/CSA/MTX | 3 | |||

| (M)UD (40) | ATGd/CSA/MTXe | 36 | ||

| ATG/CSA | 2 | |||

| ATG/tacrolimus | 1 | |||

| CSA/MTX | 1 | |||

| MMFD (8) | ATG | 6 | ||

| ATG/MMF | 1 | |||

| Muromonab (OKT3) | 1 | |||

HSCT Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, MDS Myelodysplastic syndrome, RCC Refractory cytopenia of childhood, MDS-EB MDS with excess blasts, MDS-EBt MDS with excess blasts in transformation, MDR-AML MDS-related acute myeloid leukemia, MSD matched sibling donor, MUD matched unrelated donor, UD unrelated donor, MMFD mismatched family donor, BM bone marrow, PBSC peripheral blood stem cells, CB cord blood; TBI total body irradiation, ATG/ALG anti-thymocyte/lymphocyte globuline, CSA cyclosporine, MTX methotrexate, MMF Mycophenolate mofetil.

aIncluding two patients without sufficient metaphases and exclusion of monosomy 7 and trisomy 8 by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

bDefined as frequent infections and/or laboratory evidence of immune deficiency.

cIncluding one patient with an 8/10 HLA matched sibling donor.

dIncluding one patient with alemtuzumab instead of ATG as serotherapy.

eIncluding two patients with MMF instead of MTX.

Patients had undergone HSCT from a matched sibling donor (MSD; n = 17), unrelated donor (UD; n = 40) or mismatched family donor (MMFD; n = 8) at a median age of 13.5 (4.6–19.9) years (Table 1). Stem cell source was BM (n = 37), peripheral blood (n = 27) or cord blood (n = 1). Patients were prepared with a busulfan-based (n = 35), treosulfan-based (n = 21), total body irradiation-based (n = 5) or an alternative conditioning regimen (n = 4). Graft-versus-host-disease (GvHD) prophylaxis included cyclosporine ± methotrexate for the majority of MSD-HSCT and additional anti-thymocyte globulin in UD-HSCT.

Engraftment and GvHD

All patients achieved initial engraftment. Secondary graft failure occurred in four patients (Supplementary Table 1) following MMFD-HSCT (n = 2) or MUD-HSCT (n = 2) resulting in death in two patients.

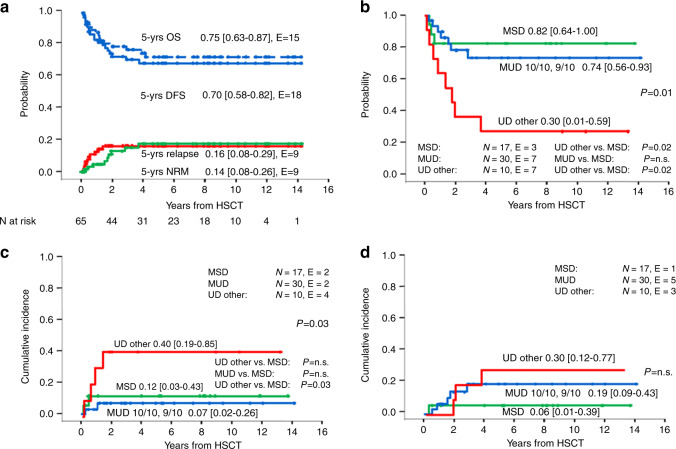

The cumulative incidence of acute GvHD (aGvHD) at day 100 was 0.34 [95% CI 0.24–0.48] for grade II–IV and 0.12 [0.06–0.24] for grade III–IV (Fig. 1A). Following MSD-HSCT two patients developed grade III–IV aGvHD (12%), while six patients grafted from an UD experienced grade III–IV aGvHD (15%). None of the patients transplanted from a MMFD had grade II–IV aGvHD (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1. Incidence of acute and chronic GvHD.

A Cumulative incidence of day 100 grade II–IV and III–IV acute GvHD. B Cumulative incidence of chronic GvHD in the 62 patients at risk. N numbers, E events.

Fifteen of the 62 patients at risk (24%) developed chronic GvHD (cGvHD), which scored limited in 11 cases and extensive in the remaining four. The cumulative incidence of overall and extensive cGvHD was 0.25 [0.16-0.39] and 0.08 [0.03-0.20], respectively (Fig. 1B). Among the 16 patients at risk grafted from a MSD, four (25%) developed cGvHD, while nine of 39 patients at risk (23%) developed cGvHD following UD-HSCT. Of the patients transplanted with a MMFD, two out of seven patients at risk developed limited cGvHD (Suppl. Table 1).

Infections and toxicity

Evaluating the frequency of infections post-HSCT, 49 patients were noted to develop any infection. Forty-one had viral infections, 16 bacterial infections, and 9 patients fungal disease (7 aspergillosis, one candidiasis, one unknown). The most common viral infections were CMV and EBV in 16 and 10 patients, respectively; one patient each developed CMV disease and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (Table 2). Adenovirus infection was recorded in four patients.

Table 2.

Infectious disease post-HSCT.

| Type of infections | Number of patients (N) |

|---|---|

| None | 16 |

| Bacterial | 16 |

| Fungal | 9 |

| Viral | 41 |

| Type of viral infections | Number of patients (N) |

|---|---|

| CMV reactivation | 16 |

| CMV disease | 1 |

| EBV reactivation | 10 |

| PTLD | 1 |

| Adenovirus | 4 |

| Other virus infection | 22 |

EBV Epstein–Barr virus, CMV cytomegalovirus, PTLD post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

With respect to non-infectious complications, the rate of complications resulting in toxicity of grade 3 or more according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events was 43%. Thirteen patients had ≥1 non-infectious complication. Hepatobiliary (16, including 3 veno-occlusive disease) and pulmonary (13) toxicity was most common (Table 3). Four patients experienced neurologic complications, three of which were described as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Table 3.

Non-infectious complications post-HSCT.

| Type of complications | Number of patients (N) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary toxicity | 13 | |

| Liver complications | 13 | |

| VOD | 3 | |

| Renal complications | 6 | |

| Neurological complications | 4 | |

| Gastrointestinal complications | 3 | |

| Cardiac complications | 2 | |

| Transplant-related microangiopathy | 3 | |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 1 | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 |

| Number of complications | Number of patients (N) | % |

|---|---|---|

| None | 37 | 57 |

| 1 Complication | 15 | 23 |

| 2 Complications | 9 | 14 |

| 3 Complications | 2 | 3 |

| 4 Complications | 0 | |

| 5 Complications | 2 | 3 |

VOD veno-occlusive disease, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Overall outcome

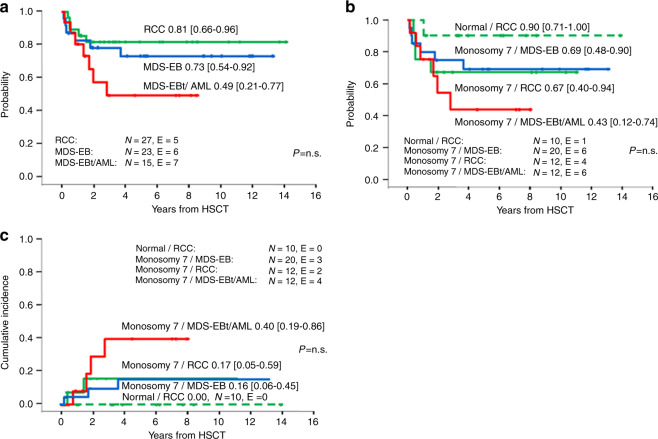

Fifty patients were alive 5 years after HSCT, resulting in a Kaplan–Meier estimate of 5-year OS of 0.75 [0.63–0.87] (Fig. 2A). The probability of DFS was 0.70 [0.58–0.82] (Fig. 2A). The cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) was 0.16 [0.08–0.29] and of NRM 0.14 [0.08–0.26]; Fig. 2A. Nine patients died of transplant-related causes. DFS was comparable for patients transplanted from MUD (0.74 [0.56–0.93]) versus MSD (0.82 [0.64–1.00]), whereas patients transplanted from mismatched UD (UD other) had a significantly lower DFS (0.30 [0.01–0.59]; p = 0.01) (Fig. 2B). The latter was primarily due to a significantly higher NRM for UD other of 0.40 [0.19–0.85] compared to 0.12 [0.03–0.43] for MSD and 0.07 [0.02–0.26] for MUD, p = 0.03; (Fig. 2C) whereas there was no significant difference in the CIR according to type of donor (Fig. 2D). Of note, of the eight patients transplanted from a MMFD, only one died after secondary graft failure, while the other seven patients are alive and disease-free. In univariate analysis, none of the other transplantation procedure-related variables such as year of HSCT, conditioning regimen, time from diagnosis to HSCT, stem cell source or donor and recipient sex had a significant impact on DFS, NRM, and CIR (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2. Overall outcome and outcome according to type of donor.

A Overall and disease-free survival and cumulative incidence of relapse and non-relapse mortality for 65 patients with MDS and GATA2 germline mutation undergoing HSCT. B Disease-free survival, C non-relapse mortality and D relapse according to type of donor. In the group of eight patients grafted from a mismatched family donor (MMFD) only one non-relapse mortality was observed (data not shown). MSD matched sibling donor, MUD matched unrelated donor (9/10 or 10/10), UD other other unrelated donor, N numbers in subgroup, E events.

Outcome according to MDS type and karyotype

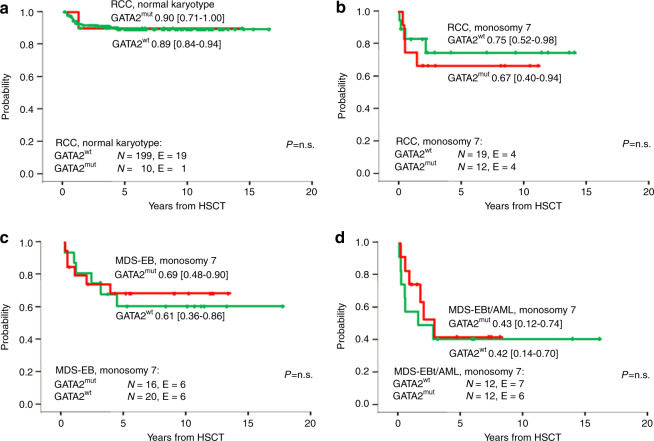

Patients with a BM blast percentage of >20% at any time prior to HSCT showed a trend toward inferior DFS (0.49 [0.21–0.77]) compared to patients with 5–19% BM blasts (0.73 [0.54–0.92]) or with <5% blasts (0.81 [0.66–0.96]) (p = 0.15; Fig. 3A). Similarly, there was a trend toward a higher CIR and NRM (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Outcome from HSCT according to MDS subtype and karyotype.

A Disease-free survival according to most advanced MDS type prior to transplantation, B Disease-free survival, and C cumulative incidence of relapse according to most advanced MDS type stratified by karyotype. RCC refractory cytopenia of childhood, MDS-EB MDS with excess blasts, MDS-EBt MDS with excess blasts in transformation, AML MDS-related acute myeloid leukemia, N numbers in subgroup, E events.

We next assessed the association between karyotype and morphologic diagnosis. Normal karyotype was associated with RCC (10/12 patients with normal karyotype had RCC) and monosomy 7 was associated with advanced MDS (32/38 advanced MDS patients had monosomy 7) (Supplementary Table 3). Thus, we performed a stratified analysis combining MDS type and karyotype. Patients with RCC and normal karyotype showed a superior DFS (0.90 [0.71–1.00]) compared to patients with monosomy seven independent of disease status (RCC 0.67 [0.40–0.94], MDS-EB 0.69 [0.48–0.90], MDS-EBt/MDR-AML 0.43 [0.12–0.74]) (Fig. 3B). While none of the patients with RCC and normal karyotype relapsed, patients with MDS-EBt/MDR-AML and monosomy 7 karyotype showed the highest relapse rate (0.40 [0.19–0.86]) (Fig. 3C).

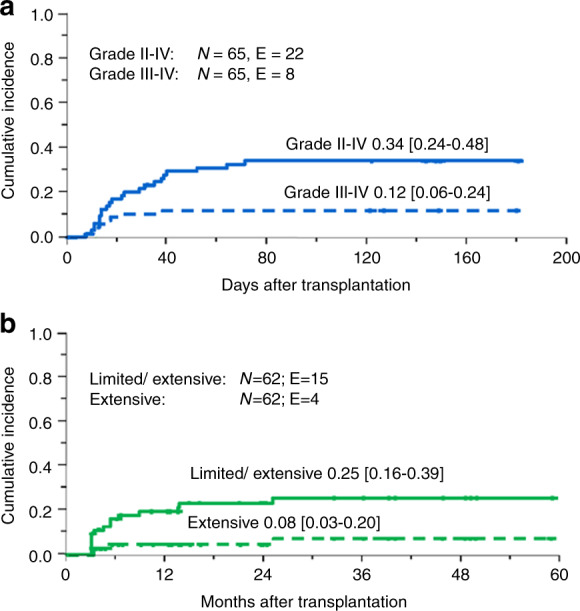

Comparison of outcome to MDS without known underlying predisposition syndrome

Next, we performed an analysis comparing the HSCT outcome of 65 GATA2mut patients with a cohort of 404 GATA2wt patients registered in EWOG-MDS and transplanted during the same time period (Supplementary Table 3). As expected, GATA2mut patients were slightly older, had more advanced disease, and carried a monosomy 7 karyotype more frequently (Supplementary Table 3). At 5 years there was no significant difference in OS (GATA2wt 0.82 [0.78–0.86] vs GATA2mut 0.75 [0.63–0.87]) and DFS (GATA2wt 0.78 [0.74–0.82] vs GATA2mut 0.70 [0.58–0.82]). Comparing the outcome of RCC patients with normal karyotype with respect to the presence or absence of a germline GATA2 mutation, both groups showed nearly identical probabilities of DFS of 90% and 89%, respectively (Fig. 4A). Similarly, there was no significant difference in DFS among patients of any MDS type with monosomy 7 with respect to the presence or absence of GATA2 deficiency (Fig. 4B–D).

Fig. 4. Outcome from HSCT comparing GATA2mut and GATA2wt patients.

Disease-free survival in GATA2mut vs GATA2wt cohorts for patients A with RCC and normal karyotype, B RCC and monosomy 7, C MDS-EB and monosomy 7 and D MDS-EBt/AML and monosomy 7. RCC refractory cytopenia of childhood, MDS-EB MDS with excess blasts, MDS-EBt MDS with excess blasts in transformation, AML MDS-related acute myeloid leukemia, N numbers in subgroup, E events.

In multivariate analysis of variables predicting DFS (including age, karyotype, highest MDS subtype and GATA2 status), the most important factors were karyotype (monosomy 7 vs. normal; p < 0.01) and most advanced MDS type (RCC vs MDS-EBt/MDR-AML; p < 0.01, Table 4). GATA2 mutation status was not significantly associated with DFS.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of variables predicting Disease-free-survival (DFS) in a cohort of 65 patients with GATA2 deficiency and 404 patients without known predisposition syndrome.

| Relative risk | 95 CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at HSCT | |||

| ≥12 yrs. vs. <12 yrs. | 1.1 | [0.7–1.6] | n.s. |

| GATA2 mutated | |||

| yes vs. no | 0.7 | [0.4–1.3] | n.s. |

| Karyotype | |||

| Monosomy 7 vs. normal | 22 | [1.2–3.9] | <0.01 |

| Other vs. normal | 1.6 | [0.8–3.8] | n.s. |

| Other vs. monosomy 7 | 0.7 | [0.4-1.3] | n.s. |

| Most advanced MDS type prior to HSCT | |||

| MDS-EB vs. RCC | 1.9 | [1.0–3.4] | 0.04 |

| MDS-EBt/ MDR-AML vs. RCC | 3.7 | [2.2–6.3] | <0.01 |

| MDS-EBt/MDR-AML vs. MDS-EB | 2.0 | [1.2–3.4] | 0.01 |

CI confidence interval, MDS myelodysplastic syndrome, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, MDS-EB MDS with excess blasts, MDS-EBt MDS with excess blasts in transformation, RCC refractory cytopenia of childhood, MDR-AML MDS-related acute myeloid leukemia, yrs years.

Discussion

We present a comprehensive analysis of pediatric patients with GATA2 deficiency undergoing HSCT for MDS. Patients with inherited bone marrow failure disorders frequently demonstrate increased transplant-related toxicity and mortality upon undergoing HSCT, but whether this is true for pediatric patients with GATA2 deficiency has remained unclear. Several studies on HSCT in GATA2 deficiency reported small numbers of patients and/or patients of varying ages and heterogeneous disease characteristics [23]. For example, Parta reported the HSCT outcome of 22 patients with GATA2 deficiency conditioned with a busulfan-based regimen [10]. Although the results are encouraging, only four patients were under the age of 20 years, and infection was the indication in approximately half of the patients, rendering it difficult to interpret the results for pediatric GATA2-deficient patients with MDS.

In our study, patients with GATA2 deficiency transplanted for MDS had a similar outcome as compared to GATA2wt patients. In multivariate analysis MDS type and karyotype but not GATA2 mutational status were significant variables for DFS, suggesting that the presence of the GATA2 mutation is not a relevant risk factor.

We did not observe an unusually high rate of NRM or atypical non-infectious complications in GATA2mut patients. A recent study reported a surprisingly high incidence of neurologic toxicities in 40% of transplanted GATA2mut patients [24]. Here, we observed neurologic complications in four patients. Hofmann also noted an increased rate of thrombotic events. Although we did not observe a high incidence of thrombotic complications, several patients experienced transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy, and three of the four neurologic events were posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. This observation might indicate a defined endothelial vulnerability in GATA2mut patients, consistent with the known role of GATA2 in the regulation of vascular integrity [25].

Interestingly, no mycobacterial infections were reported in this cohort. We did observe, however, a relatively high rate of fungal infections. HSCT performed in the past with limited surveillance and anti-fungal prophylaxis/treatments may have contributed to these findings. Overall, the frequency and distribution of different types of infections were consistent with general expectations in HSCT, with viral infections by far the most common complication.

Similar to organ toxicity, the rate of GvHD was not unusually high. In particular, cGvHD was observed in only 15 patients (24%).This is in contrast to the study by Parta [10] reporting cGvHD in 46% of patients, and points towards lower rates of GvHD in pediatric GATA2mut patients.

EWOG-MDS HSCT recommendations stratify pediatric patients with MDS according to disease stage, karyotype and hematological presentation including bone marrow cellularity (Supplementary Figure 2). HSCT with a myeloablative regimen such as busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan is recommended for patients with increased blast count [26]. Patients with RCC and abnormal karyotype are also offered HSCT soon after diagnosis; we currently recommend a preparative regimen of thiotepa, treosulfan, and fludarabine. For patients with RCC and a normal karyotype, the decision to transplant depends on the hematological presentation. Transfusion dependent or neutropenic patients with RCC and hypocellular bone marrow are offered HSCT following a reduced toxicity regimen such as treosulfan and fludarabine, while in the absence of cytopenias patients with stable disease are generally offered a watch-and-wait strategy. The HSCT data presented here, in particular the highly similar outcome in GATAmut as compared to GATAwt patients with respect to OS, DFS, NRM and relapse, support the hypothesis that the currently recommended EWOG-MDS algorithm for therapy of pediatric MDS can also be applied to children with GATA2 deficiency. Although our series includes a limited number of patients with MDS and >20% blasts, the dismal outcome of this group with a high risk of relapse indicates the urgent need for evaluation of novel strategies including cytoreduction with modern agents such as CPX351 or venetoclax, and/or post-HSCT therapy with preemptive azacytidine and donor lymphocyte infusions.

The excellent outcome of HSCT in patients with GATA2 germline disease, RCC morphology and normal karyotype raises the question whether these children should be offered HSCT once they have been diagnosed irrespective of their hematological presentation. The probability for progression to more advanced MDS is considerable, and early HSCT will spare patients cumbersome surveillance as well as the risk of inferior outcome of HSCT in more advanced disease. A similar issue arises for patients with GATA2 deficiency presenting with mild to moderate signs of immunedeficiency. Although the analysis presented here is limited to patients with MDS, the lack of evidence of increased transplant-related toxicity inherent to the GATA2 germline mutation indicates that in young individuals with GATA2 deficiency the indication for HSCT can be based on the expected clinical course. Thus, preemptive HSCT might be an acceptable strategy. Our current approach is to perform a donor search as soon as GATA2 deficiency is diagnosed. In the absence of cytopenia, karyotypic abnormalities, increase in bone marrow blasts or clinically relevant immunedeficiency, we monitor the patient closely and consider a well-matched HSCT even without severe disease manifestations. Transplanting patients with GATA2 deficiency prior to the acquisition of severe infections or secondary organ damage, such as progressive pulmonary disease, is likely to increase long-term survival of adult patients with GATA2 deficiency.

One limitation of our study is that the presence of secondary mutations was unknown. It has previously been demonstrated that somatic ASXL1 or RAS pathway mutations lead to leukemic transformation and inferior outcome [6, 27, 28]. In future prospective trials, secondary mutations need to be analyzed because they may serve as prognostic markers predicting the risk of relapse, and thus be crucial in guiding HSCT strategy.

In summary, our results indicate that pediatric patients with GATA2 deficiency are not at higher risk for HSCT-related complications or mortality compared to MDS patients without GATA2 germline mutations. Overall, the relatively low rates of GvHD, infections, and organ toxicities suggest that standard HSCT protocols can be recommended. Considering the high mortality of untreated GATA2 deficiency and the high likelihood of developing MDS/AML, these data support a strategy of early preemptive HSCT in all pediatric patients with GATA2 deficiency.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the European Working Group of MDS in Childhood (EWOG-MDS) who contributed to this effort by performing reference pathology, reference cytogenetics, reference molecular genetics, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or other forms of patient care. This work was generated within the European Reference Network for Paediatric Cancer (PAEDCAN). It was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) 01GM1911A “MyPred - Network for young individuals with syndromes predisposing to myeloid malignancies” to BS, CMN, GG, ME, AY, MW, Fritz-Thyssen Foundation 10.17.1.026MN, ERAPERMED 01KU1904, Deutsche Krebshilfe 109005, and Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung DKS2017.03 to MW. The authors acknowledge the contribution of the Center of Inborn and Acquired Blood Diseases at the Freiburg Center for Rare Diseases, and the Hilda Biobank at the Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Freiburg, Germany. The authors thank Maria Siskou-Zwecker and Wilfried Truckenmüller for excellent technical assistance and data management.

Author contributions

RBo, BS, and CMN conceived and designed the study; all authors collected clinical data; RBo, GG, BS, MW and CMN analyzed and interpreted the data; PN provided statistical analysis; RBo, BS, and CMN wrote the manuscript and all authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of members and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41409-021-01374-y.

References

- 1.Kennedy AL, Shimamura A. Genetic predisposition to MDS: clinical features and clonal evolution. Blood. 2019;133:1071–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-844662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babushok DV, Bessler M, Olson TS. Genetic predisposition to myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia in children and young adults. Leuk lymphoma. 2016;57:520–36. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1115041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastor VB, Sahoo SS, Boklan J, Schwabe GC, Saribeyoglu E, Strahm B, et al. Constitutional SAMD9L mutations cause familial myelodysplastic syndrome and transient monosomy 7. Haematologica. 2018;103:427–37. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.180778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahoo SS, Kozyra EJ, Wlodarski MW. Germline predisposition in myeloid neoplasms: unique genetic and clinical features of GATA2 deficiency and SAMD9/SAMD9L syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2020;33(3):101197. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2020.101197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donadieu J, Lamant M, Fieschi C, de Fontbrune FS, Caye A, Ouachee M, et al. Natural history of GATA2 deficiency in a survey of 79 French and Belgian patients. Haematologica. 2018;103:1278–87. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.181909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wlodarski MW, Hirabayashi S, Pastor V, Stary J, Hasle H, Masetti R, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of GATA2-related myelodysplastic syndromes in children and adolescents. Blood. 2016;127:1387–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-669937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novakova M, Zaliova M, Sukova M, Wlodarski M, Janda A, Fronkova E, et al. Loss of B cells and their precursors is the most constant feature of GATA-2 deficiency in childhood myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2016;101:707–16. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.137711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wlodarski MW, Collin M, Horwitz MS. GATA2 deficiency and related myeloid neoplasms. Semin Hematol. 2017;54:81–86. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Gea-Banacloche J, Freeman AF, Hsu AP, Zerbe CS, Calvo KR, et al. Successful allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for GATA2 deficiency. Blood. 2011;118:3715–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-365049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parta M, Shah NN, Baird K, Rafei H, Calvo KR, Hughes T, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for GATA2 deficiency using a busulfan-based regimen. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:1250–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossman J, Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Gea-Banacloche J, Zerbe C, Calvo K, Hughes T, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for GATA2 deficiency. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1940–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallhi K, Dix DB, Niederhoffer KY, Armstrong L, Rozmus J. Successful umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric patients with MDS/AML associated with underlying GATA2 mutations: two case reports and review of literature. Pediatr Transplant. 2016;20:1004–7. doi: 10.1111/petr.12764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramzan M, Lowry J, Courtney S, Krueger J, Schechter Finkelstein T, Ali M. Successful myeloablative matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a young girl with GATA2 deficiency and emberger syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol/Oncol. 2017;39:230–2. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rastogi N, Abraham RS, Chadha R, Thakkar D, Kohli S, Nivargi S, et al. Successful nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplant in a child with emberger syndrome and GATA2 mutation. J Pediatr Hematol/Oncol. 2018;40:e383–e388. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saida S, Umeda K, Yasumi T, Matsumoto A, Kato I, Hiramatsu H, et al. Successful reduced-intensity stem cell transplantation for GATA2 deficiency before progression of advanced MDS. Pediatr Transplant. 2016;20:333–6. doi: 10.1111/petr.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozyra EJ, Pastor VB, Lefkopoulos S, Sahoo SS, Busch H, Voss RK, et al. Synonymous GATA2 mutations result in selective loss of mutated RNA and are common in patients with GATA2 deficiency. Leukemia. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0899-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann INC, Bennett, JM. Childhood myelodysplastic syndrome. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, revised 4th edn. Lyon: International Agency of Reaearch on Cancer (IARC); 2017. p. 116–20.

- 18.Gohring G, Michalova K, Beverloo HB, Betts D, Harbott J, Haas OA, et al. Complex karyotype newly defined: the strongest prognostic factor in advanced childhood myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2010;116:3766–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein JP, Andersen PK. Regression modeling of competing risks data based on pseudovalues of the cumulative incidence function. Biometrics. 2005;61:223–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2005.031209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pepe MS, Mori M. Kaplan-Meier, marginal or conditional-probability curves in summarizing competing risks failure time data. Stat Med. 1993;12:737–51. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780120803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–54. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176350951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonis A, Fux M, Nair G, Mueller NJ, Haralambieva E, Pabst T, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with GATA2 deficiency-a case report and comprehensive review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1961–73. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann I, Avagyan S, Stetson A, Guo D, Al-Sayegh H, London WB, et al. Comparison of outcomes of myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation for pediatric patients with bone marrow failure, myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia with and without germline GATA2 mutations. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:1124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spinner MA, Sanchez LA, Hsu AP, Shaw PA, Zerbe CS, Calvo KR, et al. GATA2 deficiency: a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity. Blood. 2014;123:809–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Locatelli F, Strahm B. How I treat myelodysplastic syndromes of childhood. Blood. 2018;131:1406–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-765214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodor C, Renneville A, Smith M, Charazac A, Iqbal S, Etancelin P, et al. Germ-line GATA2 p.THR354MET mutation in familial myelodysplastic syndrome with acquired monosomy 7 and ASXL1 mutation demonstrating rapid onset and poor survival. Haematologica. 2012;97:890–4. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.054361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West RR, Hsu AP, Holland SM, Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Hickstein DD. Acquired ASXL1 mutations are common in patients with inherited GATA2 mutations and correlate with myeloid transformation. Haematologica. 2014;99:276–81. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.090217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.