Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The aim of this study was to leverage human genetic data to investigate the cardiometabolic effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) signalling.

Methods

Data were obtained from summary statistics of large-scale genome-wide association studies. We examined whether genetic associations for type 2 diabetes liability in the GIP and GIPR genes co-localised with genetic associations for 11 cardiometabolic outcomes. For those outcomes that showed evidence of co-localisation (posterior probability >0.8), we performed Mendelian randomisation analyses to estimate the association of genetically proxied GIP signalling with risk of cardiometabolic outcomes, and to test whether this exceeded the estimate observed when considering type 2 diabetes liability variants from other regions of the genome.

Results

Evidence of co-localisation with genetic associations of type 2 diabetes liability at both the GIP and GIPR genes was observed for five outcomes. Mendelian randomisation analyses provided evidence for associations of lower genetically proxied type 2 diabetes liability at the GIP and GIPR genes with lower BMI (estimate in SD units −0.16, 95% CI −0.30, −0.02), C-reactive protein (−0.13, 95% CI −0.19, −0.08) and triacylglycerol levels (−0.17, 95% CI −0.22, −0.12), and higher HDL-cholesterol levels (0.19, 95% CI 0.14, 0.25). For all of these outcomes, the estimates were greater in magnitude than those observed when considering type 2 diabetes liability variants from other regions of the genome.

Conclusions/interpretation

This study provides genetic evidence to support a beneficial role of sustained GIP signalling on cardiometabolic health greater than that expected from improved glycaemic control alone. Further clinical investigation is warranted.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available. The scripts for the analysis are available at: https://github.com/vkarhune/GeneticallyProxiedGIP.

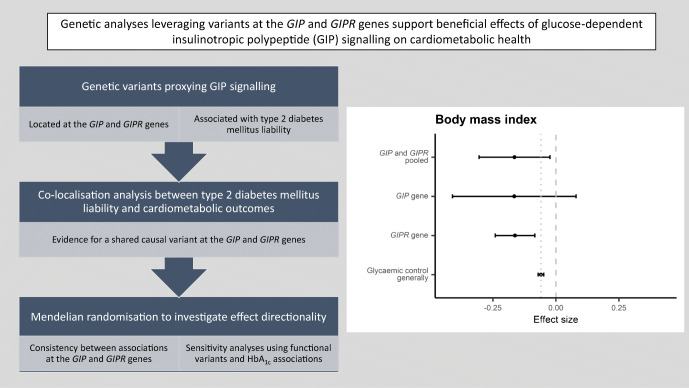

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00125-021-05564-7.

Keywords: Cardiometabolic disease, Co-localisation, Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, Mendelian randomisation, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

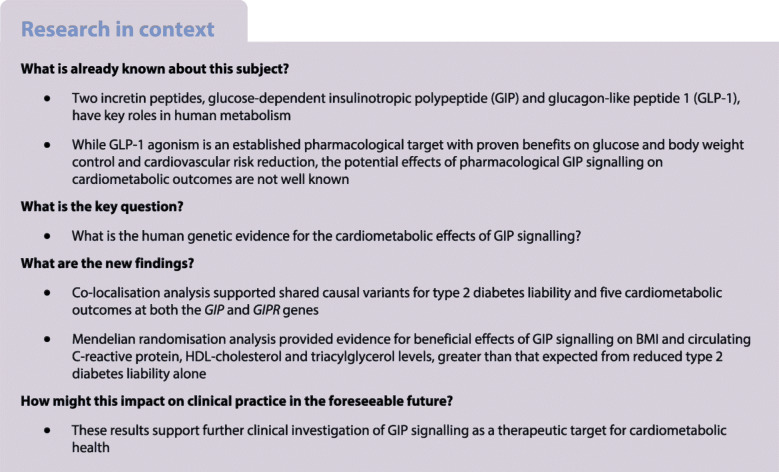

Introduction

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (or gastric inhibitory polypeptide, GIP) is an incretin peptide that stimulates insulin secretion after oral nutrient intake. Both GIP and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) are involved in regulating energy homeostasis [1]. GLP-1 agonism is an established pharmacological target for treating type 2 diabetes and obesity, however it is unclear whether pharmacological GIP agonism represents a similar therapeutic opportunity [2]. Here, we leverage human genetic data to investigate the potential of targeting GIP signalling for the treatment of cardiometabolic disease.

Methods

Overall study design

We investigated whether genetic associations for type 2 diabetes liability co-localised with genetic associations for 11 cardiometabolic outcomes (Table 1) at the GIP and GIPR genes. For those outcomes that showed evidence for co-localisation, we performed Mendelian randomisation (MR) analyses to investigate the association of genetically proxied glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) signalling with the cardiometabolic outcomes, and whether these estimates are greater than that expected from reduced type 2 diabetes liability alone. Further details are given in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) Methods.

Table 1.

Genome-wide association studies used to obtain the summary statistics

| Phenotype | Sample size | Cases | Controls | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposures | ||||

| Type 2 diabetesb | 74,124 | 824,006 | Mahajan et al, 2018 | |

| Type 2 diabetesc | 228,499 | 1,178,783 | Vujkovic et al, 2020 | |

| HbA1c | 344,182 | Neale lab 2020d | ||

| Outcomes | ||||

| Disease outcomes | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 64,164 | 561,055 | Wuttke et al, 2019 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 60,801 | 123,504 | Nikpay et al, 2015 | |

| HF | 47,309 | 930,014 | Shah et al, 2020 | |

| Ischaemic stroke | 34,217 | 406,111 | Malik et al, 2018 | |

| Cardiometabolic traits | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase | 344,136 | Neale lab 2020 | ||

| BMI | 484,680 | Pulit et al. 2018 | ||

| CRP | 343,524 | Neale lab 2020 | ||

| Systolic BP | 745,820 | Evangelou et al. 2018 | ||

| Lipids | ||||

| HDL-C | 315,133 | Neale lab 2020 | ||

| LDL-C | 343,621 | Neale lab 2020 | ||

| Triacylglycerol | 343,992 | Neale lab 2020 | ||

aThe references for the original studies are given in the ESM

bUsed for co-localisation analysis

cUsed for MR analysis

dAll Neale lab 2020 GWAS summary statistics are available at: http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank

LDL-C, LDL-cholesterol

Genetic association estimates

Genetic association estimates for SNPs with type 2 diabetes liability, HbA1c levels and the considered cardiometabolic outcomes were obtained from genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics (Table 1). The individual studies had previously obtained relevant ethical approval and participant consent.

Statistical analyses

We used co-localisation analysis to compare the genetic association signals for type 2 diabetes liability and each cardiometabolic outcome for variants within GIP and GIPR. The ‘coloc’ method applied here examines the likelihood of a shared causal variant for both exposure and outcome [3]. Co-localisation was declared if the posterior probability (PP) for a model with a shared causal variant exceeded 0.8 (ESM Methods). For the outcomes where co-localisation analysis suggested separate causal variants for type 2 diabetes liability and the outcome, co-localisation was re-run after excluding the variants that were in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.2) with the most likely causal SNP for the outcome (ESM Methods).

The outcomes that showed evidence for co-localisation were taken forward for MR analysis. In MR, genetic variants are used as proxies for an exposure (here, GIP signalling) to examine its potential causal effect on an outcome, and the method can be applied to investigate drug effects [4]. Given the known role of GIP signalling on improving glycaemic control in healthy individuals [5], we identified genetic proxies as SNPs located within GIP and GIPR genes that associated with type 2 diabetes liability at p < 5 × 10−6 and also associated with HbA1c levels at p < 0.05 with a concordant direction, and applied clumping by excluding variants with r2 > 0.1 with the lead SNP. Prior filtering of genetic variants was applied based on the co-localisation analysis, so that variants exhibiting potential horizontal pleiotropy were removed (ESM Methods).

The main MR analysis was conducted by pooling the associations of all proxy variants from both the GIP and GIPR genes using the random-effects inverse-variance weighted method. To compare the associations of genetically proxied GIP signalling with improved glycaemic control more generally, we compared the main MR results to that of a general reduction in type 2 diabetes liability and improved glycaemic control using variants across the genome that associated with type 2 diabetes liability at p < 5 × 10−6 and HbA1c levels at p < 0.05 with a concordant direction, excluding variants within GIP and GIPR (ESM Methods). In sensitivity analysis, we performed MR using exposure genetic association estimates for HbA1c levels, rather than type 2 diabetes liability (ESM Methods). As a final sensitivity analysis, we performed MR using functionally relevant variants or expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL, ESM Methods).

Results

Co-localisation analysis showed evidence of a shared causal variant for type 2 diabetes liability and eight outcomes at the GIP gene, and six outcomes at the GIPR gene (PP > 0.8, ESM Table 1). For the five outcomes of heart failure (HF), BMI, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and triacylglycerols, there was evidence for Co-localisation also protects at both GIP and GIPR.

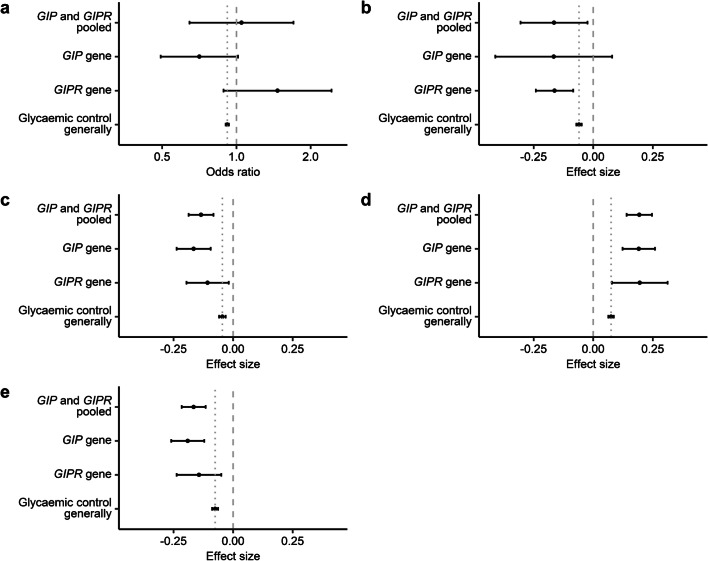

The co-localising outcomes were taken forward to MR analysis, where increased genetically proxied GIP signalling (using variants given in ESM Tables 2–4) was associated with lower BMI (estimate and its 95% CI in SD units per halving the genetically proxied odds of type 2 diabetes = −0.16 [−0.30, −0.02]), CRP levels (−0.13 [−0.19, −0.08]) and triacylglycerol levels (−0.17 [−0.22, −0.12]), and higher HDL-C levels (0.19 [0.14, 0.25]; Fig. 1; ESM Table 4). For these outcomes, the MR estimates were similar when using variants from GIP and GIPR genes separately (Fig. 1; ESM Table 4). The MR estimate for risk of HF was inconclusive (OR per halving the odds of type 2 diabetes [95% CI] = 1.05 [0.65, 1.70]; Fig. 1; ESM Table 4). There was evidence of a larger association of genetically proxied GIP signalling compared with genetically proxied reduced type 2 diabetes liability more generally for CRP, HDL-C and triacylglycerol levels (all p < 0.001), but not strongly for BMI (p = 0.07, ESM Table 4). Similar results were obtained when using variant–exposure associations for HbA1c levels rather than for type 2 diabetes liability (Pearson correlation of the MR β estimates = 0.99; ESM Table 5; ESM Figs 1 and 2), and when using missense variant rs2291725 in GIP or eQTL variant rs12709891 in GIPR (ESM Tables 2 and 6; ESM Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

(a) ORs for risk of HF and (b–e) effect size estimates (MR β coefficients for BMI [b], CRP [c], HDL-C [d] and triacylglycerol levels [e], all in SD units) and their 95% CIs per halving the odds of genetically proxied type 2 diabetes liability. The dashed vertical line represents the null, and the dotted vertical line represents the estimates for glycaemic control generally

For those outcomes that co-localised only at one genomic locus, there was evidence for association between genetically proxied GIP signalling and lower risk of coronary artery disease (OR [95% CI] = 0.51 [0.37, 0.71]), lower alanine aminotransferase (−0.13 [−0.20, −0.07]) and lower systolic BP (−0.18 [−0.25, −0.12]) at the GIP locus, with all these the estimates exceeding those obtained for reduced type 2 diabetes liability more generally (ESM Fig. 4; ESM Table 7).

Discussion

Our genetic analyses using human data provide consistent support for favourable effects of sustained GIP signalling on BMI, CRP, HDL-C and triacylglycerol levels. The MR estimates for CRP, HDL-C and triacylglycerol levels exceeded and were statistically heterogeneous to those obtained for reduced type 2 diabetes liability more generally, suggesting additional mechanisms specific to GIP signalling. The MR results were replicated in analyses restricted to functionally relevant variants.

Although a dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist has shown efficacy for glucose control and weight loss in clinical trials of patients with type 2 diabetes [6, 7], it is not clear how much of the observed effect is specifically attributable to GIP agonism. Preclinical studies have supported that sustained GIP receptor (GIPR) agonism prevents weight gain and enhances weight loss in diet-induced obese mice [8, 9]. Our analyses using human genetic data provide further complementary evidence of the beneficial cardiometabolic effects of sustained GIP signalling.

We observed discrepancy in the MR estimates for HF risk that were generated when considering the GIP gene (lower risk) as compared with the GIPR gene (higher risk). Although a cardiovascular outcomes trial of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibition with saxagliptin found increased hospitalisation rates for HF [10], this was not found for sitagliptin [11]. Further work is required to ascertain whether our findings offer any mechanistic or clinical insight in this regard.

The use of randomly allocated genetic variants to proxy drug effects in the MR paradigm is more robust to environmental confounding that can hinder causal inference in observational studies [4]. We selected the genetic proxies for sustained GIP signalling based on its known biological effects in healthy individuals, namely improved glycaemic control and reduced liability to type 2 diabetes [5]. Previous work selected a variant to proxy GIP signalling based on its relation to fasting GIP levels, and in contrast to our current findings produced MR results to support a detrimental effect of GIP signalling on coronary artery disease risk [12]. Further work is required to clarify how different genetic variants at the GIPR gene might relate to GIP signalling and its consequent downstream metabolic effects.

Our work has limitations. The genetic associations were obtained from GWAS on mainly European ancestry individuals, and these results may not generalise to other ancestries. The findings do not extend to effects of other glucose-lowering medications that indirectly alter GIP signalling, and may not be applicable to individuals with diabetes, in whom the physiological effects of GIP signalling may be altered [13]. Finally, the genetic variants employed as instruments proxy the effect of lifelong alterations in GIP signalling and therefore the MR results should not be directly extrapolated to quantitatively estimate the clinical effect of short-term GIPR agonism [4]. Of relevance, recent evidence has supported that long-term GIPR agonism desensitises adipocyte GIPR activity in a manner resembling acute GIPR antagonism [8].

In conclusion, by leveraging human genetic data, we provide evidence of favourable effects of sustained GIP signalling on BMI, CRP, HDL-C and triacylglycerol levels. These results support further clinical investigation of GIP agonism as a therapeutic target for cardiometabolic disease.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 619 kb)

Acknowledgments

Authors’ relationships and activities

AKO, LBK, WGH and JMMH are employed full-time by Novo Nordisk and own minor employee-based stock. DG is employed part-time by Novo Nordisk. Novo Nordisk markets several GLP-1 based drugs for the treatment of diabetes and/or obesity, and has a GIP based compound in clinical development. The remaining authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Abbreviations

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait loci

- GIP

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GIPR

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- HDL-C

HDL-cholesterol

- HF

Heart failure

- MR

Mendelian randomisation

- PP

Posterior probability

Contribution statement

VK and DG designed the study. VK conducted all statistical analyses. VK and DG drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results, participated in critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. DG and VK take responsibility for the contents of the article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ville Karhunen, Email: v.karhunen@imperial.ac.uk.

Dipender Gill, Email: dipender.gill@imperial.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Gribble FM, Reimann F. Function and mechanisms of enteroendocrine cells and gut hormones in metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(4):226–237. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Incretin hormones: their role in health and disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(S1):5–21. doi: 10.1111/dom.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE, et al. Bayesian test for Colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(5):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill D, Georgakis M, Walker V et al (2021) Mendelian randomization for studying the effects of perturbing drug targets [version 2; peer review: 3 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res 6(16). 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16544.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bailey CJ. GIP analogues and the treatment of obesity-diabetes. Peptides. 2020;125:170202. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2019.170202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J et al (2021) Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 10.1056/NEJMoa2107519 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rosenstock J, Wysham C, Frías JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-1): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):143–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Killion EA, Chen M, Falsey JR, et al. Chronic glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) agonism desensitizes adipocyte GIPR activity mimicking functional GIPR antagonism. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18751-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mroz PA, Finan B, Gelfanov V, et al. Optimized GIP analogs promote body weight lowering in mice through GIPR agonism not antagonism. Mol Metab. 2019;20:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of Sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):232–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jujić A, Atabaki-Pasdar N, Nilsson PM, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality: a prospective study. Diabetologia. 2020;63:1043–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmann NC, Gasbjerg LS, Heimbürger SM, et al. No acute effects of exogenous glucose-dependent Insulinotropic polypeptide on energy intake, appetite, or energy expenditure when added to treatment with a long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist in men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(3):588–596. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 619 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are publicly available. The scripts for the analysis are available at: https://github.com/vkarhune/GeneticallyProxiedGIP.