Abstract

Regulator-of-G-protein-signaling-5 (RGS5), a pro-apoptotic/anti-proliferative protein, is a signature molecule of tumor-associated pericytes, highly expressed in several cancers, and is associated with tumor growth and poor prognosis. Surprisingly, despite the negative influence of intrinsic RGS5 expression on pericyte survival, RGS5highpericytes accumulate in progressively growing tumors. However, responsible factor(s) and altered-pathway(s) are yet to report. RGS5 binds with Gαi/q and promotes pericyte apoptosis in vitro, subsequently blocking GPCR-downstream PI3K-AKT signaling leading to Bcl2 downregulation and promotion of PUMA-p53-Bax-mediated mitochondrial damage. However, within tumor microenvironment (TME), TGFβ appeared to limit the cytocidal action of RGS5 in tumor-residing RGS5highpericytes. We observed that in the presence of high RGS5 concentrations, TGFβ–TGFβR interactions in the tumor-associated pericytes lead to the promotion of pSmad2–RGS5 binding and nuclear trafficking of RGS5, which coordinately suppressed RGS5–Gαi/q and pSmad2/3–Smad4 pairing. The RGS5–TGFβ–pSmad2 axis thus mitigates both RGS5- and TGFβ-dependent cellular apoptosis, resulting in sustained pericyte survival/expansion within the TME by rescuing PI3K-AKT signaling and preventing mitochondrial damage and caspase activation. This study reports a novel mechanism by which TGFβ fortifies and promotes survival of tumor pericytes by switching pro- to anti-apoptotic RGS5 signaling in TME. Understanding this altered RGS5 signaling might prove beneficial in designing future cancer therapy.

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Tumour angiogenesis

Introduction

Disorganized blood vasculature is a cardinal feature of all rapidly growing solid tumors, contributing to metastasis and resistance to therapy [1–3]. Tumor-resident perivascular cells (i.e., pericytes) exhibit loose attachment with endothelium, resulting in a leaky, chaotic vasculature that limits tissue perfusion and promotes hypoxia within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [4]. Tumor pericytes express high levels of platelet-derived-growth-factor-receptor-β (PDGFRβ), regulator-of-G-protein-signaling-5 (RGS5), neuron-glial-2 (NG2), and low levels of α-smooth-muscle-actin (SMA) representing immature phenotype [5]. Among various molecules, RGS5 has been identified as signature marker of angiogenic tumor pericytes [4, 5].

RGS5 belongs to B/R4 sub-family of RGS-proteins that modulate G-protein-coupled-receptors (GPCRs) signaling by accelerating intrinsic GTPase activity of Gα subunit of heterotrimeric G-protein [6]. RGS5 interacts specifically with Gαi and Gαq via its conserved RGS-domain but not with Gαs/Gα13 and attenuate receptors involved in the development of vascular-systems- such as angiotensin-II, endothelin-1, and sphingosine-1-phosphate [7]. Restricted expression of RGS5 in vascular-smooth-muscle-cells (vSMCs) and pericytes suggest its participation in hemodynamic-regulation, pericytes/vSMCs recruitment, and vessel-maturation; whereas RGS5 deficiency is correlated with pericytes loss in PDGFβ/PDGFRβ knock-out mice [8]. High RGS5 levels have been observed in normal physiological conditions like wound-healing and ovulation and also in abnormal tumor vasculature [5, 9, 10]. Moreover, high RGS5 expression confers immunosuppressive properties to tumor pericytes [11]. Accordingly, RGS5 silencing improves immune-cell infiltration, vascular-morphology, and promotes pericyte-maturation [5].

Although the role of RGS5 in cardiovascular, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and lipid metabolism has been widely studied [12–15]. This molecule has only recently been appreciated for its impact on cancers. Recent in vitro studies from three groups independently suggest RGS5 upregulation facilitates apoptosis in ovarian cancer, lung cancer, and endothelial cells [16–18]. Conversely, other studies showed that increased RGS5 expression is correlated with tumor progression, metastasis, and recurrence [19–23] accompanied by enhanced pericytes’ frequency [5, 24, 25]. Therefore, a confounding paradigm is established in which pericytes that are crucial to tumor neoangiogenesis and progression preferentially express high levels of lethal RGS5 protein, that in principle, expedite their survival within TME.

Herein, we studied the classical RGS5-mediated apoptotic signature in pericytes, which is operational only outside TME. For the first time we demonstrated how the presence of pleiotropic cytokine, transforming-growth-factor-β (TGFβ) within TME converts this pro-apoptotic signal pathway into an anti-apoptotic/pro-survival signal in tumor pericytes. TGFβ signaling is mediated via downstream phosphorylation of R-Smads upon hetero-tetrameric complexes of serine/threonine kinase receptors-TGFβRII (constitutively active) with type-I TGFβRs either ALK1 or ALK5. TGFβ/ALK1 signaling via Smad1/5/8 promotes proliferation and migration whereas TGFβ/ALK5 signaling via Smad2/3 inhibits these events [26]. TGFβ acts as a tumor suppressor by promoting apoptosis via upregulation of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members [27, 28]. Disruptive TGFβ pathway in cancer induces epithelial-mesenchymal-transition, associated with tumor-angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [29, 30]. TGFβ required for endothelial-cells and pericytes association signals via ALK1 and ALK5 expressed on pericytes, having antagonist effects [31]. Bone-morphogenetic-proteins (BMP)-9 and -10, ligands of TGFβ-superfamily inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth via ALK1 [32, 33].

Here, we observed TGFβ-stimulation prevents the interaction between RGS5 and Gα-inhibitor (Gαi) and Gαq and instead promotes RGS5 binding with pSmad2/3, leading to RGS5 nuclear translocation, altering Smad-dependent transcription and enforcing survival and proliferation of RGS5highpericytes within tumors.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Different primary and secondary antibodies used are shown in Supplementary Table I. Mouse recombinant cytokines, PDFGβ, TGFβ, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-10 were procured from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). DMEM with glucoselow/high and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Hi-Media (Mumbai, India). 2,4-Thiazolidinedione (#375004) was procured from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). PI3-kinase inhibitor (#9901S) was procured from Cell Signaling Technologies (MA, USA). RGS5 siRNA (# sc-45815) and TGFβ receptor type I/type II kinases inhibitor (LY2109761) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). TGFβ and RGS5 siRNAs were also synthesized using Silencer® Si-RNA construction kit (Life Technologies, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell lines

C3H10T1/2, Clone 8 (ATCC® CCL-226TM) cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) and National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India in January 2017 and January 2019 respectively. B16-F10 and Lewis lung carcinoma cell lines were purchased from National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS), Pune, India. Cells were cultured at 37 °C, with 5% CO2 and 100% humidity. Since cell lines were purchased from authorized repositories authentication using STR profiling was done in the respective cell banks. Further in vitro growth characteristics, morphological properties, and expression of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) markers (CD90, CD105, and CD106) were checked by flow cytometry. Mycoplasma contamination was checked by PCR using the EZdetectTM PCR kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (#CCK009, Hi-Media, India). Cell lines were frozen down at two passages. C3H10T1/2, B16-F10, and LLC were maintained according to ATCC guidelines and all experiments were performed within 7–10 passages after thawing. C3H10T1/2 cells were maintained in DMEM low-glucose medium, whereas B16-F10 and LLC cells in DMEM high-glucose supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-Glutamine–Penicillin–Streptomycin solution (Hi-Media, Mumbai, India).

Mice and tumor

Wild-type (Wt) female C57BL/6 mice (age, 4–6 weeks, body weight, 20–25 g on average) were obtained and cared at the Institutional Animal Facility as described previously [34] following ARRIVE guidelines with prior approval from Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (IAEC Approval No. 1774/RB-6/2015/19 and 1774/RB-25/2019/03). To establish solid tumors, 2 × 105 B16-F10 cells/mice were inoculated s.c. in the lower right flank of mice. Tumor growth was monitored twice in a week using calipers and size was calculated in mm2 (length × width). Metastatic lung tumors were developed by injecting 3 × 105 B16-F10 or LLC cells through tail-vein as described [35]. Intratumoral administration of TGFβRs inhibitor or siRNAs was performed after tumor size reached 70 mm2. Mice were euthanized with overdose of Ketamine HCl (160 mg/kg) + Xylazine (20 mg/kg) via intra-peritoneal injection and tumors were harvested after reaching the desired/permissible size or when mice showed symptoms of ill health. Mice were randomly assigned after tumor establishment. Investigators were blinded at the time of group allocation before and after tumor development. Thereafter different groups were marked by investigator. Mice with ill health and having tumor size ≥20 mm in any direction were excluded from study, otherwise no mice were excluded from analysis after treatment. Six mice were included in each group after tumor inoculation.

Human tumors

Post-operative tumor samples were taken from invasive breast and oral cancer patients (n = 22), operated at Chittaranjan National Cancer Institute, Kolkata, India, after obtaining informed written consent from patients and approval from Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC Ref # CNCI-IEC-RB-2020-2) under supervision of surgical oncologists. The study was performed following the ethical guidelines of “Declaration of Helsinki”. Tumor samples were categorized according to TNM staging system based on the protocol from American Joint Committee for Cancer [36] depicting tumor size of T4 > T3 > T2. Molecular subtype of ER+PR+Her2−/+ (luminal B subtype) invasive ductal carcinoma and subtype of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (WDSCC) and moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (MDSCC) for oral carcinomas were evaluated from histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis by pathologists. Histopathologically confirmed normal tissues surrounding tumor were considered as control. Information regarding tumor staging and molecular or histological subtyping has been included in Supplementary Table II.

Preparation of tumor supernatant, fragments, and lysate

Tumor supernatants were prepared from media obtained from confluent B16-F10 cell cultures. Media was decanted and subjected to centrifugation at 1500 rpm to eliminate cells’ debris and later used for tumor conditioning of cultured pericytes.

To prepare tumor fragments, B16-F10 tumors were surgically removed from tumor-bearing mice under sterile condition, sliced into smaller pieces and exposed to osmotic shock.

Tumor-lysate was prepared from enzymatic digestion of dissected B16-F10 tumors to make single-cell suspension. Cells (2 × 107) were washed with PBS and subjected to 5–7 cycles of freeze (in liquid nitrogen) and thaw (at 37 °C water bath), followed by sonication and centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Protein content of the supernatant collected was determined by Bradford assay and tumor-lysate (1 μg/ml) was used in in vitro cultures for mimicking TME.

Differentiation and isolation of pericytes

~100% confluent C3H10T1/2 cells were differentiated into pericytes by supplementing 1 ng/ml mrPDGFβ (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) for 48 h in DMEM low-glucose medium as previously described [11] and used as in vitro normal pericytes in this study. Differentiated pericytes were confirmed by upregulation of pericytes’ markers like NG2, desmin, αSMA, and RGS5 as assessed by flow cytometry. Normal pericytes were isolated in vivo from murine kidneys, non-metastatic lungs, and adjacent tissues of human tumors. Tumor pericytes were isolated from s.c. established B16-F10 bearing mice, metastatic murine lungs, and human tumors. Tissues were spliced and digested enzymatically as previously described [37]. Single-cell suspension was prepared by passing the cells through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were stained with CD45-allophycocyanin, CD31-PE, NG2-FITC, and CD140β/PDGFRβ-PerCP. CD45−CD31−NG2+CD140β+ enriched population was sorted using a multicolor fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSAria; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) as previously described [11]. In all cases, cells were >90% pure as determined by flow cytometry. RGS5+ pericytes were sorted from CD45−CD31−NG2+CD140β+ population using RGS5 antibody followed anti-rabbit biotin-IgG and streptavidin particles-DM in BD IMag cell separating system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

In vitro RGS5highpericytes were generated by exposing differentiated pericytes from C3H10T1/2 cells with B16-F10 melanoma supernatant and osmotically fragmented tumor cells for 24 h, followed by replacement with normal-media for next 24 h as previously described [11] and were used for staining, western blotting, immunofluorescence assays, and PCRs.

Cloning and transfection

RNA was isolated from kidneys of C57BL/6 mice and cDNA was synthesized using First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Hanover, MD). Utilizing such cDNA and using primers forward 5′-AAGGTACCATGTGTAAGGGACTGGCA-3′ and reverse 5′-AAGGATCCCTTGATTAGCTCCTTATA-3′, containing restriction sites for BamHI and KpnI, RGS5 (Gene ID: 19737) coding region was amplified. Amplified cDNA was then inserted into pcDNA6.1b cloning vector followed by transformation in E. coli DH5α. Transformed cells were selected against ampicillin. Extracted plasmid DNA (1 μg) was then transfected into in vitro differentiated pericytes (2 × 106 cells) using lipofectamine-2000 reagent (2 µl) (Life Technologies Inc., CA) for 48 h as per manufacturer’s protocol. Gene and protein expression of RGS5 was assessed after 24, 48, or 72 h.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and qPCR

RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) and RT-PCR was carried out for corresponding cDNA as described [34]. Quantitative PCR was performed using LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche, CA, USA) in Applied Biosystem 7500 Real-Time PCR system (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA). Fold change in mRNA expression were calculated from generated Ct values by analyzing ΔΔCt values, keeping β-actin as control gene. Primers used are enlisted in Supplementary Table III.

Cell death analysis

0.4% Trypan blue (Invitrogen, #15250061, MA, USA) was used to determine cell viability as per manufacturer’s protocol and cells were counted with haemocytometer under microscope (Olympus CKX41). Annexin V-PI staining was performed using Annexin V Apoptosis detection Kit (BD Biosciences, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Event acquisition was performed using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA) along with suitable negative controls.

Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation

Protein expression was checked in total cell lysates and in cytosolic or nuclear fractions of cells extracted as previously described [11, 38]. In brief, 50 µg of protein lysates were boiled in Laemmli buffer for 5 min and separated 10–12% of SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Following electrophoresis gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked and incubated with desired primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Dilutions of primary antibodies and secondary antibodies used for western blotting were 1:800-1:1000 and 1:10,000 respectively. Protein bands were developed using ECL Western Blotting Substrate Kit (Advansta, CA, USA). To study the interactions between RGS5 and other proteins, co-immunoprecipitation was performed as described [34]. In brief, 50 µg of protein lysates were pre-cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 10 min, incubated overnight with primary antibodies or control IgG at 4 °C, followed by incubation with protein G Sepharose beads for 2 h. The immune complexes were boiled with SDS-sample buffer, subjected to electrophoresis and co-immunoprecipitated protein were analyzed by western blotting. Intensity of blots was scanned in Quantity One (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

Flow-cytometric staining

Pericytes were stained with RGS5, NG2, CD31, CD45, PDGFRβ, Akt, pAkt (Ser & Thr), Ki-67, survivin and vimentin following the method described [39, 40], with primary antibody dilution range from 1:200 to 1:500. Fluorochrome-tagged secondary antibodies were used in 1:500-1:1000 dilutions. Detection of cellular apoptosis was performed by staining cells with AnnexinV-PI, using FITC-Annexin V apoptosis detection kit I (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). JC-1 (10 μl of 200 µM stock) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) was used as the manufacturer’s protocol to assess the change in mitochondrial-membrane potential. Flow cytometry was performed in FACSCalibur or FACSAria (Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA) as required and was analyzed using Cell Quest (Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA) and FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) softwares.

Immunofluorescence microscopy and analysis

Pericytes were grown on chambered slides. Frozen samples of mice (B16-F10) and human tumors were sectioned in cryostat as previously reported [25]. Tumor-sections (5 μm) or 200 cells/chamber were blocked in 5% BSA for 2 h, then O/N incubated with primary antibodies in dilution range from 1: 200 to 1: 500, followed by incubation with fluorochrome-tagged secondary antibodies. Slides were mounted with Fluoroshield-DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were acquired using Fluorescence-Microscope (Leica, BM 4000B, Germany) and Confocal-Microscope (Carl Zeiss, 63X/1.4 oil DIC Plan-APOCHROMAT objective, Germany).

Fluorescence intensity was analyzed using Fiji-ImageJ software https://imagej.net/Fiji. The corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) has been calculated using the formula: CTCF = Integrated density−(Area of selected area × Mean fluorescence of background readings). Quantification of co-localization between RGS5 and pSmad2/3 was analyzed using Fiji-ImageJ Coloc2 software. 2D intensity histograms were generated from merged images and co-localization coefficient was calculated for each channel as described [41]. A value of <0.2 indicates no co-localization, ~0.4–0.6 represents moderate, ~0.6–0.8 shows strong, whereas >0.8 indicates complete co-localization.

siRNA mediated in vitro and in vivo silencing

Expression of RGS5 was knocked down using commercially available RGS5 siRNA (m) (RGS5 siRNA-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-45815). Further sense, anti-sense and control siRNAs for RGS5 (Gene ID: 19737) and TGFβ1 (Gene ID 21803) were prepared using Silencer® Si-RNA construction kit (Life Technologies, USA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. The oligo sequences were (RGS5 siRNA-2) sense 5′-AAGAGGTGAACATTGACCACTCCTGTCTC-3′ and antisense 5′-AAAGTGGTCAATGTTCACCTCCCTGTCTC-3′, (TGFβ1 siRNA-1) sense oligonucleotides 5′-AACAACGCCATCTATGAGAAACCTGTCTC-3′ and antisense 5′-TTTCTCATAGATGGCGTTGCCTGTCTC-3′, (TGFβ1 siRNA-2) sense 5′-AAGCGGACTACTATGCTAAAGCCTGTCTC-3′ and antisense 5′-CTTTAGCATAGTAGTCCGCCCTGTCTC-3′. In vitro pericytes or B16-F10 cells were transfected with siRNAs of 50 nM final concentration using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, MA, USA). Transfection with non-specific siRNA was used as control.

Intratumoral knockdown of RGS5 and TGFβ1 was achieved by injecting siRNA (10 µg/100 µl) after complexed with in vivo-jetPEI, linear polyethylenimine (Polypus-transfection, Illkirch, France) at a ratio of N/P = 8 according to the manufacturer’s protocol [42]. The first injection was performed on tumor size reaching ~70–90 mm2. siRNAs were administered for three times at an interval of 3 days. Mice were sacrificed following 3 days of last injection.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were conducted following the manufacturer’s protocol (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Briefly, pericytes (1 × 106) were stimulated with mrTGFβ (1 ng/ml) for 1 h and then fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde as described [43]. In brief, fixed pericytes were washed with PBS containing 1 mM PMSF and lysed in SDS-lysis buffer. DNA was sheared by ultrasonication (Hielscher, NJ) at 30 kHz and 10 cycles of 30 s ON/OFF pulse, followed by overnight incubation with anti-Smad2 antibody (5 μg), which was then captured using anti-goat IgG-coated agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Eluted DNA was extracted using phenol/chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. Thirty-five cycles of PCR were performed using promoter specific primers for SMAD Binding Element (SBE) or CAGA box in −147 to −332 of mouse bik gene promoter: sense 5′-AAAGGGAAGCCACAGAAG-3′, antisense 5′-AGTCGTTAGCTTGCAGACAT-3′, and −1055 to −1093 of human bik gene promoter: sense 5′-AACTAGCCGGGCATGGTGG-3′, antisense 5′-TTCCGGGCTCTGGACCTTCT-3′ and analyzed on 2% agarose gels.

Docking of RGS5 with other cytosolic proteins

The crystal structure of human RGS5 (PDB: 2CRP) [44, 45] was downloaded from RCSB Protein Data Bank [46]. This structure only incorporates residues 44–180 of the full-length RGS5 sequence (Uniprot ID: O15539). The missing region (1–43) and the terminal residue (181) were integrated using MODELLER, based on a homology modeling approach [47]. The protein-protein docking of the modeled RGS5 with the phosphorylated form of smad2 protein (PDB: 1KHX) [48] was performed using GRAMMX server [49]. The docked structure containing an optimum number of hydrogen bonds (checked by HBPLUS) [50] and binding energy, was chosen for further analysis. The PDB id of heterotrimeric complex of smad2 and smad4 is 1U7V [51]. Based on ΔGint value, the best heterodimeric complex assembly (designated, AB) was downloaded from EMBL-PISA server [52]. The interface areas between the two heterodimeric complexes of Smad2–Smad4 and RGS5–Smad2 were also determined using PISA. The DNA-binding region in RGS5 was predicted by DNABIND server [53], and the presence of the NLS signal was predicted by NLS Mapper software [54]. The molecular diagrams were made using Pymol [55].

In vitro tube formation assay

B16-F10 melanoma cells were mixed with differently conditioned pericytes in a ratio 5:1 and total 2.5 × 104 cells were suspended in DMEM low-glucose medium and added on Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA). Photographs of three random fields were taken 3 h after seeding at ×20 magnification under microscope (Olympus CKX41).

In vitro invasion and migration assay

CFSE stained serum-starved B16-F10 melanoma cells were mixed with serum-starved differently conditioned pericytes in a ratio 5:1 and total 2.5 × 104 cells were added on the upper chamber of invasion chambers (Corning® Matrigel® Invasion Chamber, NY) and (8.0 μm) transwell membranes (Corning Inc., NY) and invasion/migration was assessed against 15% serum-containing DMEM-high-glucose media, filled in the lower chamber. After 6 h the membranes were mounted with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and the number of invasive/migrated B16-F10 cells and pericytes were observed under Fluorescence-microscope (Leica, BM 4000B, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All reported results represent the mean±SD of data obtained from 3–5 (for in vivo analysis) or 6-8 (for in vitro assays) independent experiments. The number of mice used was estimated using ‘Resource Equation’ described in http://www.3rs-reduction.co.uk/html/6_power_and_sample_size.html, with E value equal or superior to 10. Data distribution was assumed to be normal and variances were assumed to be similar without prior testing. The number of in vitro or in vivo experiments used for each analyses are indicated in each figure legend. Statistical significance was established by two-tailed unpaired t-test, one-way and two-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test with differences between groups attaining p ≤ 0.05 considered as significant and correlations were obtained by Pearson Correlation coefficient using Graphpad Prism 8.1.1 (San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical test used for a particular experiment is mentioned in figure legends.

Results

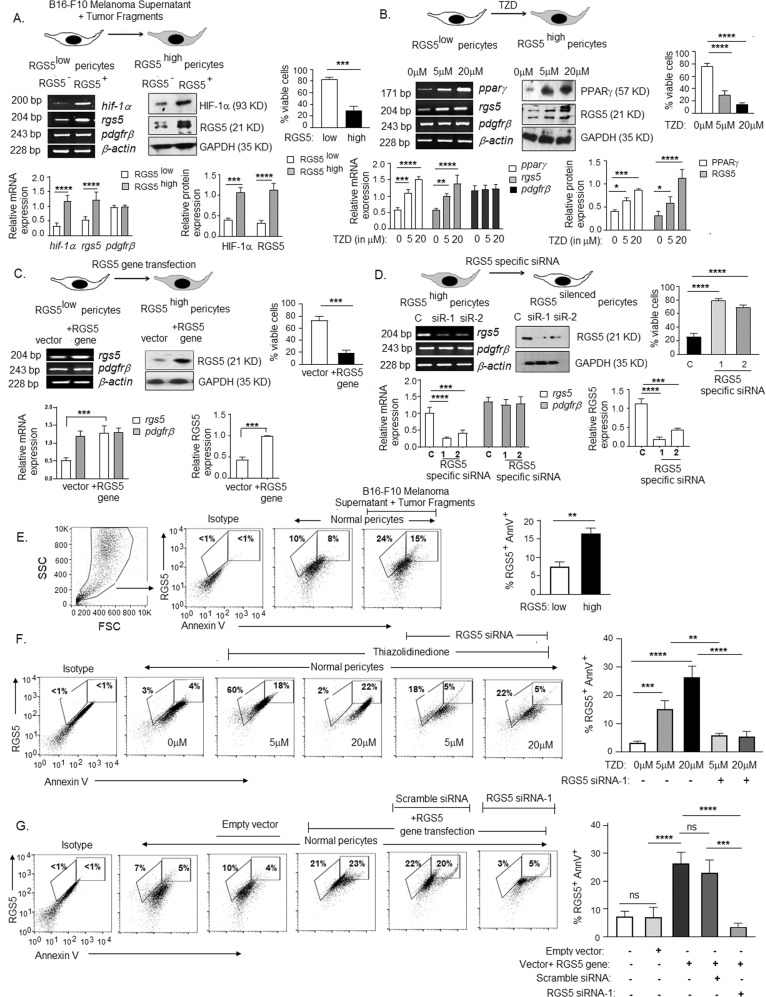

RGS5 over-expression promotes cellular apoptosis

Our previous study demonstrated that RGS5 over-expression in tumor-associated versus normal pericytes is well associated with tumor-angiogenesis, immune suppression, and disease progression [5, 11, 56]. However, three independent studies demonstrated the pro-apoptotic nature of RGS5 in vitro [16–18], providing a conflicting operational paradigm for RGS5highpericytes within TME. To address this issue, we overexpressed RGS5 in pericytes by three different approaches and assessed cell viability. Firstly, in vitro normal/RGS5lowperciytes were exposed to B16-F10-melanoma tumor-supernatant and osmotically fragmented tumor cells for 24 h, followed by replacement with normal-media for next 24 h. With the increase in HIF1α in the presence of tumor-supernatant and tumor-fragments, RGS5 expression was also induced (Fig. 1A). Secondly, RGS5 expression also induced in RGS5lowpericytes upon 12h-treatment with different concentrations of TZD (Thiazolidinedione), a ligand for peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor-γ (PPARγ) (Fig. 1B). Thirdly, RGS5lowpericytes were transfected with murine RGS5 gene (plasmid cDNA) for 48 h to promote RGS5 over-expression (Fig. 1C). Consistent with previous studies, abundant RGS5 decreased percent viable cells from ~75–80% to ~15–25%, irrespective of strategies used (Fig. 1A–C). Whereas transfecting RGS5highpericytes with RGS5-specific siRNAs increase cell viability (Fig. 1D). Further, in the presence of B16-F10 melanoma supernatant+tumor-fragments/TZD/RGS5 transfected-gene, the mean percentage of RGS5+AnnexinV+ events increased from ~5–7% to ~15–27% (Fig.1E–G). Conversely, knockdown of RGS5 using RGS5-specific siRNAs in pericytes treated with TZD (5 μM and 20 μM) or transfected with RGS5-gene ablated RGS5+AnnexinV+ percent, preventing cellular apoptosis (Fig. 1F, G). Our cumulative data, therefore, support the pro-apoptotic nature of RGS5 when overexpressed in pericytes in vitro.

Fig. 1. In vitro upregulation of RGS5 promotes apoptosis in pericytes.

A RT-PCR represent mRNA expression of hif1-α, rgs5 and pdgfrβ and WB data represent HIF1-α and RGS5 expression in RGS5low normal pericytes vs RGS5high pericytes generated by exposing pericytes to B16-F10 melanoma supernatant and tumor-fragments in vitro. Bar diagrams (below) represent relative mRNA and protein expressions, with mean±SD (n = 6). Bar diagram (right) represents percent viable pericytes as observed by trypan blue assay, with mean±SD (n = 6). B RT-PCR data represents mRNA expression of pparγ, rgs5 and pdgfrβ and WB data shows expression of PPARγ, RGS5 in protein levels upon treatment with increasing TZD concentrations. Bar diagrams (below) represent relative mRNA and protein expression with mean±SD from six individual experiments (n = 6). Bar diagram (right) shows percent viable pericytes as observed by trypan blue assay, with mean±SD (n = 6). C rgs5 and pdgfrβ expression were detected by RT-PCR and immunoblot represent RGS5 expression upon transfection with plasmid vector+RGS5 gene, with bar diagrams (below) showing relative mRNA and protein expression of RGS5 levels with mean±SD (n = 6, individual experiments). Bar diagram (right) indicates percent viable pericytes observed by trypan blue assay upon RGS5 gene transfection. D mRNA expression of rgs5 and pdgfrβ as assessed by RT-PCR and immunoblot represent RGS5 expression upon knockdown of RGS5 expression with RGS5-specific siRNA-1 and 2 vs scramble siRNA (denoted as C). Relative mRNA and protein expression were represented with bar diagrams (below) and percent viable pericytes observed by trypan blue assay upon RGS5-silencing is represented as bar diagram (right) with mean± SD (n = 6). β-actin and protein GAPDH were kept as loading control in RT-PCR and WB respectively in each case. Statistical significance was obtained by unpaired t-test and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 are indicated. E–G Expression of RGS5 and AnnexinV in differently treated pericytes was assessed by flow-cytometry analysis and representative dot plots and bars obtained by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test showing mean± SD of five individual experiments are presented. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns: not significant are indicated.

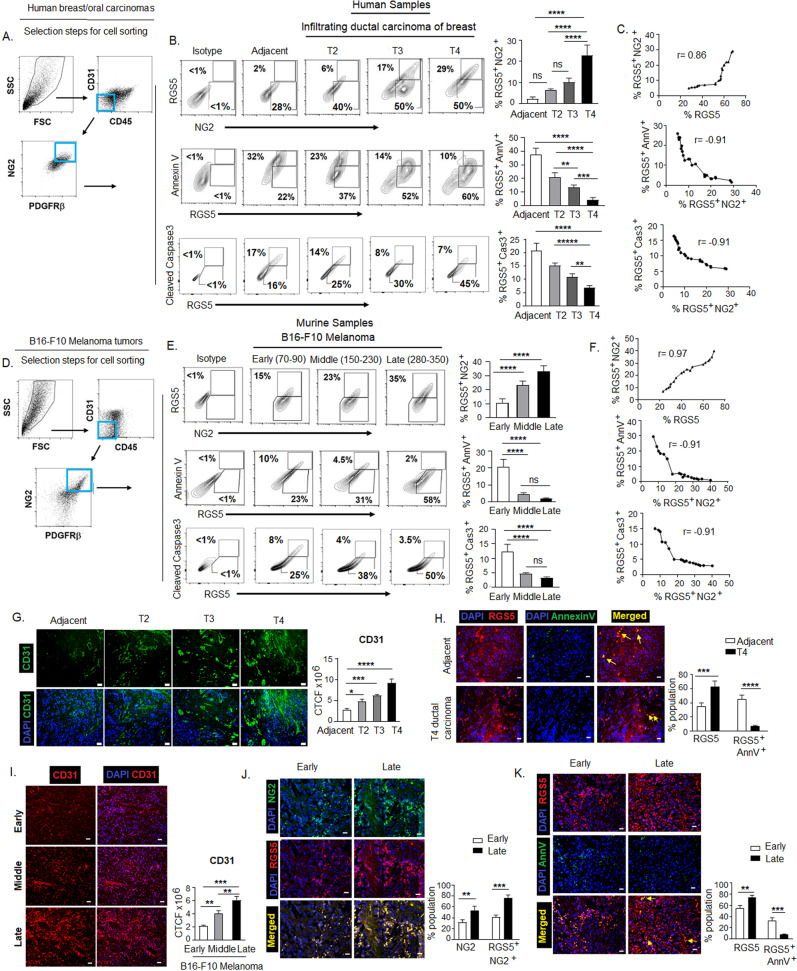

TME-resident RGS5+pericytes resist cellular apoptosis and their proliferation is correlated well with tumor-growth

Given the pro-apoptotic impact of overexpressed RGS5 in in vitro pericytes, we next evaluated the apoptotic status of RGS5+pericytes in vivo within TME of human breast infiltrating-ductal-carcinoma (IDC) (n = 11) and oral-squamous-cell-carcinoma (OSCC) (n = 11) grouped according to growing tumor stage (i.e., T2 < T3 < T4) and compared with their adjacent normal tissues (n = 6). The frequency of RGS5+NG2+pericytes gated on CD31−CD45−NG2+PDGFRβ+ population isolated from enzymatically digested tissues was higher in tumor-tissues than adjacent-normal with a simultaneous decrease in RGS5+AnnV+ and RGS5+Caspase3+ population with the increasing tumor size/stage i. e from T2–T4 stages (Fig. 2A, B). In growing tumor, RGS5+NG2+ population exhibit positive correlation (r = 0.9) with RGS5, while negatively correlated with RGS5+AnnV+ and RGS5+Caspase3+ population in human cancer patients with Pearson-correlation coefficient, r = −0.91 (Fig. 2C). A similar trend was observed in the B16-F10-melanoma tumor model sorted according to increasing tumor sizes (early: 70–90 mm2, middle: 150–230 mm2, and late: 280–350 mm2) at different time points post-tumor-inoculation. With ascending tumor-growth frequency of RGS5+NG2+pericytes increased with RGS5 expression, whereas percent positivity of AnnexinV and cleaved Caspase3 on RGS5+pericytes decreased (Fig. 2D–F). We observed that the abnormality in tumor vasculature as denoted by increased and chaotic expression of CD31 concomitantly increased with the reduction of RGS5+AnnexinV+ cells in human tumor-tissues versus adjacent-normal (Fig. 2G, H). Similarly, with increasing B16-F10 melanoma-size, expression of CD31 and percent population of RGS5+NG2+ pericytes increased with the decrease in RGS5+AnnV+ population (Fig. 2I, K).

Fig. 2. RGS5highpericytes from TME escape cellular apoptosis.

A Dot plots representing selection steps of sorting of pericyte population from human tumor tissues. B Representative contour plots show population of RGS5+NG2+, RGS5+AnnV+, and RGS5+Caspase3+ in CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ pericyte population isolated from sequentially progressed (T2, T3, T4) human breast tumor samples and assessed by flow cytometry (n = 11). Bar diagrams represent mean± SD of RGS5+NG2+, RGS5+AnnV+, and RGS5+Cas3+ population in T2, T3, and T4 breast/oral cancer stages (n = 3 breast carcinomas and n = 3 each stage). Similar experiment was performed with oral tumor samples (data not shown). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 are indicated. C Positive correlation between RGS5+ and RGS5+NG2+ (r = 0.86), negative co-relation between RGS5+NG2+ and RGS5+AnnV+ (r = −0.91) and between RGS5+NG2+ and RGS5+Cas3+ (r = −0.91) in human breast (n = 11) and oral (n = 11) carcinomas are presented with scatter plots. r represents Pearson correlation coefficient. D Dot plots representing selection steps of sorting of pericyte population from B16-F10 melanoma of different sizes. E Representative contour plots show population of RGS5+NG2+, RGS5+AnnV+, and RGS5+Caspase3+ in CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ pericyte population isolated from B16-F10 melanoma of increasing tumor size, denoted as; early: 70–90 mm2, middle: 150–230 mm2 and late: 280–350 mm2. Bars represent mean±SD of RGS5+NG2+, RGS5+AnnV+, and RGS5+Cas3+ percent population (n = 6, in each group). ****p < 0.0001. F Positive correlation between RGS5+ and RGS5+NG2+ (r = 0.97), negative co-relation between RGS5+NG2+ and RGS5+AnnV+ (r = −0.91) and between RGS5+NG2+ and RGS5+Cas3+ (r = −0.91) in B16-F10 melanoma tumors are represented with scatter-plots. r represents Pearson correlation coefficient. G Representative immunofluorescence images of human breast carcinoma show abnormal vascularity as measured by CD31 expression with increasing stages (T2, T3, and T4) of tumors along with adjacent tissue as control, bars demonstrate total cell fluorescence (CTCF) of CD31 *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. H Representative immunofluorescence images represent co-localization of RGS5 (PE-tagged) and AnnexinV (FITC-tagged) in T4 ductal breast carcinoma versus its adjacent tissue sections. Bar diagram represents mean±SD (n = 6) of percent population of RGS5+ and RGS5+AnnV+ co-localized cells in tumor-sections ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. I Representative immunofluorescence images depict vascular abnormality as denoted by CD31 expression increases with tumor growth in B16-F10 melanoma tumor sections from early late. Bars demonstrate total cell fluorescence (CTCF) of CD31. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. J Representative co-localized images of RGS5 (PE-tagged) and NG2 (FITC-tagged) as observed in early versus late B16-F10 melanoma tumor sections by immunofluorescence. Bar diagram represents mean±SD (n = 6) of percent population of NG2+ and RGS5+NG2+ co-localized cells in tumor-sections. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. K Representative co-localized images of RGS5 (PE-tagged) and AnnV (FITC-tagged) as observed in early versus late B16-F10 melanoma tumor sections by immunofluorescence. Bar diagram represents mean± SD (n = 6) of percent population of RGS5+ and RGS5+AnnV+ co-localized cells in tumor tumor-sections. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. G–K Fluorescence was measured by ImageJ software and statistical significance were obtained by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Images acquired in ×20 magnification (Leica, BM 4000B, Germany) and scale bar represents 10 µm.

The results mentioned above are of significance since, unlike in vitro observations, in vivo tumor pericytes have shown resistance to apoptosis and have shown a strong correlation between their proliferation, tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth.

To further confirm the differential apoptotic behavior of RGS5 inside and outside TME, we established different metastatic tumors (B16-F10-melanoma and LLC) in same tissue i.e. lungs and observed reduced RGS5+AnnV+ population in metastatic lungs in comparison to non-metastatic lungs (Fig. 3A). We also assessed RGS5+AnnV+ population in pericytes isolated from different tumors-origin and observed that anti-apoptotic behavior of RGS5highpericytes is independent of tumor nature/origin (Fig. 3B–D). RGS5highpericytes isolated from B16-F10/LLC displayed only rare (~3–6%) AnnexinV positivity, which was in stark contrast to RGS5highpericytes isolated from tumor un-involved kidney or non-tumor tissue microenvironment (~40% AnnexinV+) (Fig. 3C, D).

Fig. 3. RGS5highpericytes survive and proliferate within TME.

A Dot plots representing selection steps of sorting of pericyte population from murine normal and metastatic lungs, established in C57BL/6 mice by inoculation of B16-F10 melanoma and LLC via tail vein. Representative contour plots show RGS5+AnnV+ population in metastatic lungs versus non-metastatic lungs as checked by flow cytometry in CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ gated population. Bar diagrams represent mean± SD (n = 6) of RGS5+AnnV+ cells in murine normal and metastatic lungs. **p < 0.01. B Dot plots representing selection steps of sorting pericyte population from murine kidney, B16-F10 melanoma and LLC. C Representative dot plot show RGS5+pericyte population in normal murine kidney, B16-F10 melanoma and LLC tumors. Histograms on right side representing AnnV+ population in RGS5+ pericytes gated on CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+sorted pericytes from different murine tissue/tumor microenvironment by the procedure described in (B). D Bars indicating mean± SD of percent RGS5low, RGS5high, and RGS5+AnnV+ population in pericytes sorted by the procedure described in (B) from three individual experiments. Statistical significance is attained by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ***p < 0.001,****p < 0.0001. E Representative contour plots show RGS5+AnnV+ population upon exposing RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) to tumor-lysate. F Bars represent mean± SD of percent of RGS5+AnnV+ pericyte population on exposing RGS5highpericytes as generated in Fig. 1A–C to B16-F10 tumor-lysate (n = 6) obtained by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s comparison test. ****p < 0.0001 and ns is not significant. G, H Representative histograms and bars show expression and mean± SD (n = 6) of percent of survivin and Ki-67 as analyzed by flow cytometry in RGS5highpericytes sorted from in vivo B16-F10 melanoma versus murine kidney (as in Fig, 3B) and in vitro RGS5highpericytes exposed to tumor-lysate versus RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A). ****p < 0.0001 as significant.

Furthermore, in line with in vivo observations, in vitro exposure of RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A–C) to tumor-lysate/TME significantly reduced AnnexinV positivity from ~35-40% to ~3-6% in comparison to tumor-supernatant/TZD/RGS5-gene-transfection (Fig. 3E, F). Therefore, the cumulative data suggest that tumor-lysate/TME uniquely protects RGS5highpericytes from apoptosis, presumably to support tumor growth and vascular disorganization.

Further exploration revealed that RGS5highpericytes not only escape apoptosis but exhibit improved potential to proliferate within TME. Expression of survivin (survival marker) and Ki67 (proliferation marker) found to be higher within RGS5highpericytes isolated (as in Fig. 3B) from tumor versus tumor-uninvolved kidney and also within in vitro RGS5highpericytes when cultured with tumor-lysate in comparison to untreated RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 3G, H). Collectively, these results suggest tumor-conditioning of RGS5highpericytes co-ordinately improves cellular vitality and proliferative potential.

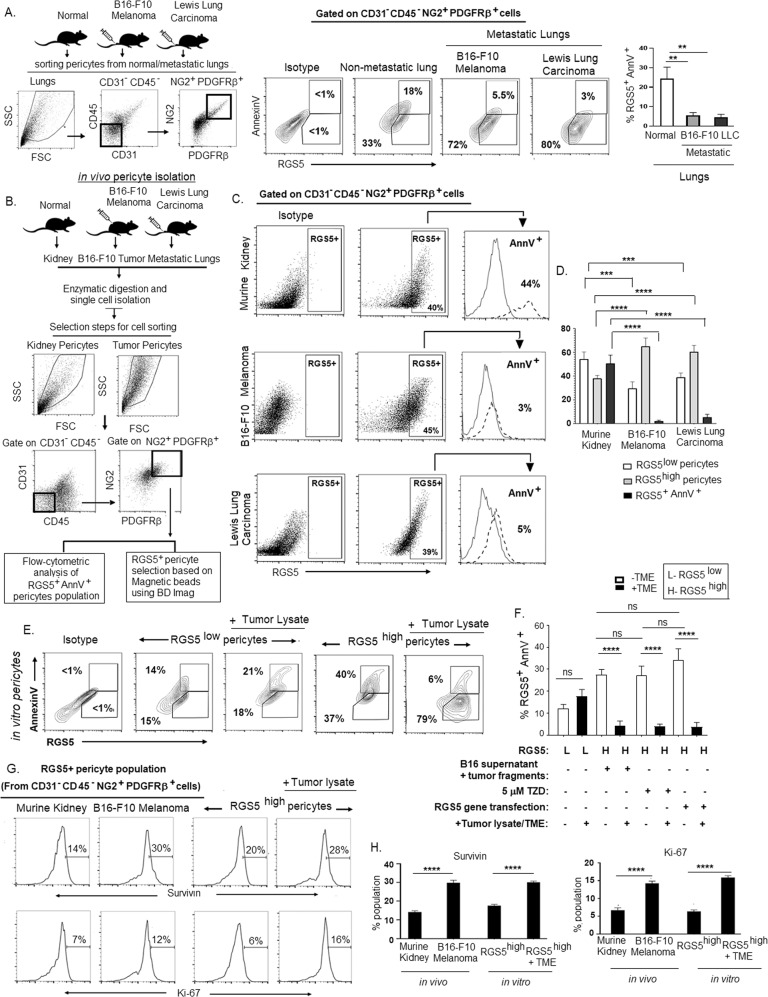

TGFβ antagonizes the pro-apoptotic function of RGS5 in tumor pericytes

Considering the differential apoptotic behavior of RGS5highpericytes inside and outside TME, we next determined how intermittent tumor-conditioning affects the apoptotic status of RGS5highpericytes in vitro. We exposed in vitro RGS5highpericytes (as generated in Fig. 1A) with B16-F10-melanoma tumor lysate for 12 h, followed by withdrawal of tumor stimulation and subsequent re-exposure of tumor-lysate at an interval of 12 h. We observed that removal of tumor-associated stimuli restored the susceptibility of RGS5highpericytes to apoptosis which again abrogated on re-addition of tumor stimuli (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. TGFβ appeared as a critical factor within TME for switching pro- to anti-apoptotic behavior of RGS5highpericytes.

A Microenvironment dependency of RGS5-mediated apoptotic pathway. RGS5highpericytes (generated upon exposure to B16-F10 melanoma tumor supernatant+ tumor fragments (TME)) were subjected to withdrawal of TME for 12 h followed by re-addition of the same. RGS5 and AnnV expression in RGS5+ population was determined by flow cytometry. Representative dot plots show RGS5 expression and their respective histograms for AnnV+ population in RGS5highpericytes. Bars indicate mean± SD (n = 6) of percent of RGS5-expressing pericytes and AnnexinV positivity in RGS5highpericytes. B Determination of responsible factor(s) within TME for the anti-apoptotic switch, RGS5high pericytes were exposed to neutralizing anti-cytokine antibodies for IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TGFβ and recombinant mTGFβ (1 ng/ml). Apoptosis was evaluated by AnnexinV-PI staining followed by flow cytometry. Illustrative dot plots show percentage of AnnexinV. C Bars representing mean± SD (n = 6) of percentage of AnnV+ pericytes upon TGFβ neutralization and rmTGFβ supplementation at different concentrations. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. D Representative dot plots indicating percentage of AnnV+ in RGS5high/RGS5lowpericytes exposed to rTGFβ. Bars represent percent population of RGS5+ and AnnV+ pericytes after supplementation of rTGFβ to RGS5lowpericytes and RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) in vitro.*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. E Bars represent the TGFβ concentration (measured by ELISA) as mean± SD (n = 6) in tumors obtained from human infiltrating breast carcinoma of different stages and B16 melanoma with different tumor sizes as versus adjacent normal tissues and murine kidney respectively. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. F Bars represent fold change in mRNA expression of TGFβRII, ALK1, ALK5, RGS5 in RGS5+ pericytes sorted from CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ pericytes population in murine kidney, early and late B16-F10 melanoma following steps described in Fig. 3B. G Dot plots represent the selection steps of RGS5+ pericytes sorted from CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ population in murine kidney, early and late B16-F10 melanoma. Histograms represent expression of TGFβRII, ALK1, ALK5 analyzed by flow cytometry in sorted RGS5+ pericytes and their fold change in MFI are presented as bar diagram (right) with mean± SD (n = 3). H Bars represent fold change in mRNA expression of TGFβRII, ALK1, ALK5, RGS5 in RGS5low, and RGS5highpericytes generated as described in Fig. 1A, with +/− rTGFβ-stimulation in vitro. I Dot plots represent the selection steps of RGS5+ pericytes in vitro. Histograms represent expression of TGFβRII, ALK1, ALK5 analyzed by flow cytometry in RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes generated as described in Fig. 1A, +/− rTGFβ-stimulation in vitro and their fold change in MFI are represented with bar diagram (right) with mean± SD (n = 3). J, K Bars obtained by one way ANOVA following Tukey’s comparison test represent fold change in mRNA expression Smad2 and Smad3 as determined from Ct values generated by quantitative real-time PCR, keeping β-actin as housekeeping gene in RGS5+ pericytes sorted from CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ pericytes population in murine kidney (K), early (E) and late (L) B16-F10 melanoma and in RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes with +/− rTGFβ-stimulation in vitro. L, M Dot plots represent RGS5+pSmad2/3+ percent population in RGS5+ pericytes sorted from CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ cells in vivo and in RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes +/− rTGFβ-stimulation in vitro. Bar diagrams obtained by two-way ANOVA following Tukey’s comparison test (on right) represent mean± SD percent population of RGS5+ and RGS5+pSmad2/3+ both in vivo and in vitro. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns: not significant.

Progressor TME is rich in various cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, TGFβ, and reportedly, many of these cytokines play decisive roles in survival/death of multiple cell types [57]. To ascertain the relevance of a particular cytokine(s) in the regulation of RGS5-associated pericyte death within TME, RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) were exposed to tumor lysate along with a panel of neutralizing-antibodies against IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, or TGFβ. Notably, tumor-conditioned RGS5highpericytes remained resistant to apoptosis unless TGFβ was neutralized in cultures (Fig. 4B). We subsequently observed the culture of RGS5highpericytes in media supplemented with rmTGFβ for 12 h was sufficient to promote apoptotic resistance in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B–D). Interestingly, in vitro rmTGFβ supplementation in RGS5lowpericytes/RGS5silencedpericytes shows its apoptotic effect with increasing AnnexinV positivity to ~30–40%. Dual presence of extrinsic TGFβ and abundant intrinsic RGS5 results in apoptotic resistance within pericytes (Fig. 4D). On analyzing the mRNA expression of ligands TGFβ and its superfamily BMP9/10, we observed fold change in TGFβ mRNA is relatively higher in late melanoma vs murine-kidney/early melanoma. Whereas mRNA fold change of BMP9 and BMP10 did not increase with B16-F10 melanoma tumor size (Supplementary Fig. S1A–C). Even ELISA revealed high TGFβ concentration in both human and murine tumors compared to normal tissues lysate (Fig. 4E). Therefore, with increasing TGFβ-levels (from early to late tumor), RGS5+ population increased while RGS5+AnnV+ decreased (Supplementary Fig. S1D-E). Given the importance of TGFβ in regulating survival/death of RGS5highpericytes, next we assessed the expression of TGFβ receptors-TGFβRII, ALK1 and ALK5 by qPCR and flow-cytometric analysis. We observed significantly higher mRNA expression, fold change in MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) and percent population of TGFβRs in RGS5highpericytes isolated from late melanoma tumor vs kidney or early tumors (Fig. 4F, G, Supplementary Fig. S2A-B). Moreover, in vitro TGFβ-stimulation significantly upregulates the mRNA expression of TGFβRs and their fold change in the MFI and percent population in RGS5high vs RGS5lowpericytes and TGFβ-unstimulated RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 4H, I, Supplementary Fig. S2C, D). As TGFβ-signaling is mediated mainly via Smads (Smad1/2/3) activation [58], next we looked at the expression and activation of Smads in RGS5low/highpericytes with/without TGFβ-stimulation both in vivo and in vitro. mRNA expression of Smad2 and Smad3 was found to be higher in both tumor-derived (i.e., TGFβ-enriched microenvironment) and TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 4J, K). Increased Smad2/3 mRNA expression correlates with the enhanced RGS5+pSmad2/3+ population in tumor-derived versus normal kidney-derived RGS5highpericytes and in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes versus RGS5lowpericytes as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 4L, M). RGS5highpericytes derived from late tumor or in vitro TGFβ-stimulation of RGS5highpericytes did not show any significant alteration in Smad1 and pSmad1/5/8 (Supplementary Fig S3A–D) for RGS5highpericytes derived from early tumor or TGFβ-unstimulated RGS5highpericytes. However, in vitro treatment of RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) with rmTGFβ modestly increased RGS5 (Fig. 4H, Supplementary Fig. S4) whereas TGFβ-stimulation in presence TGFβRs inhibitors LY2109761 do not increase RGS5 (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B).

Therefore, cumulative data suggest a central regulatory role for TGFβ in switching death and survival signaling in RGS5highpericytes.

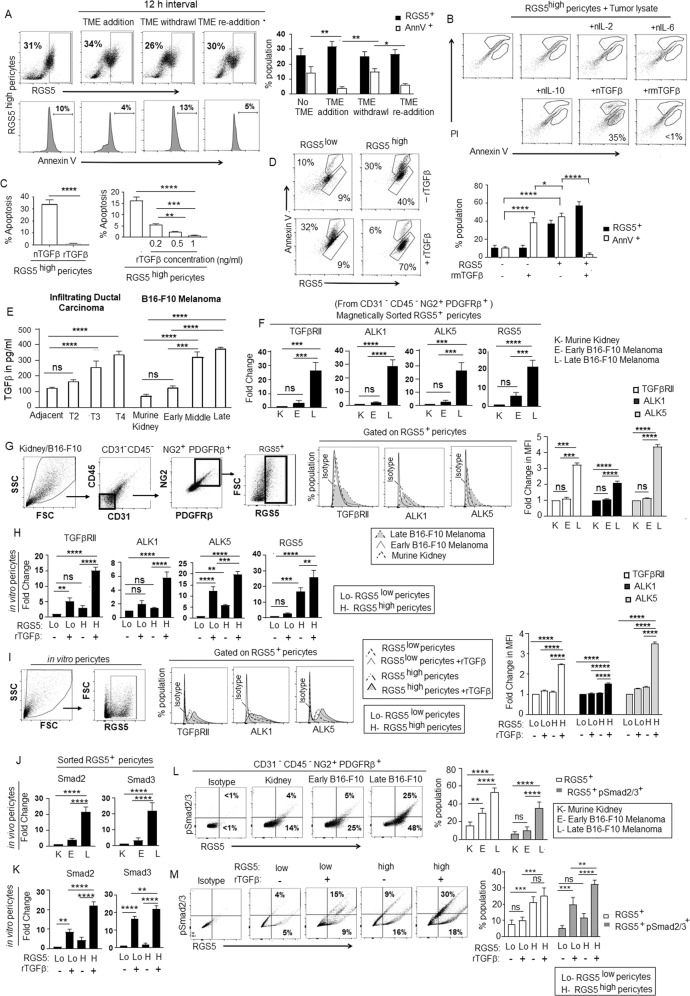

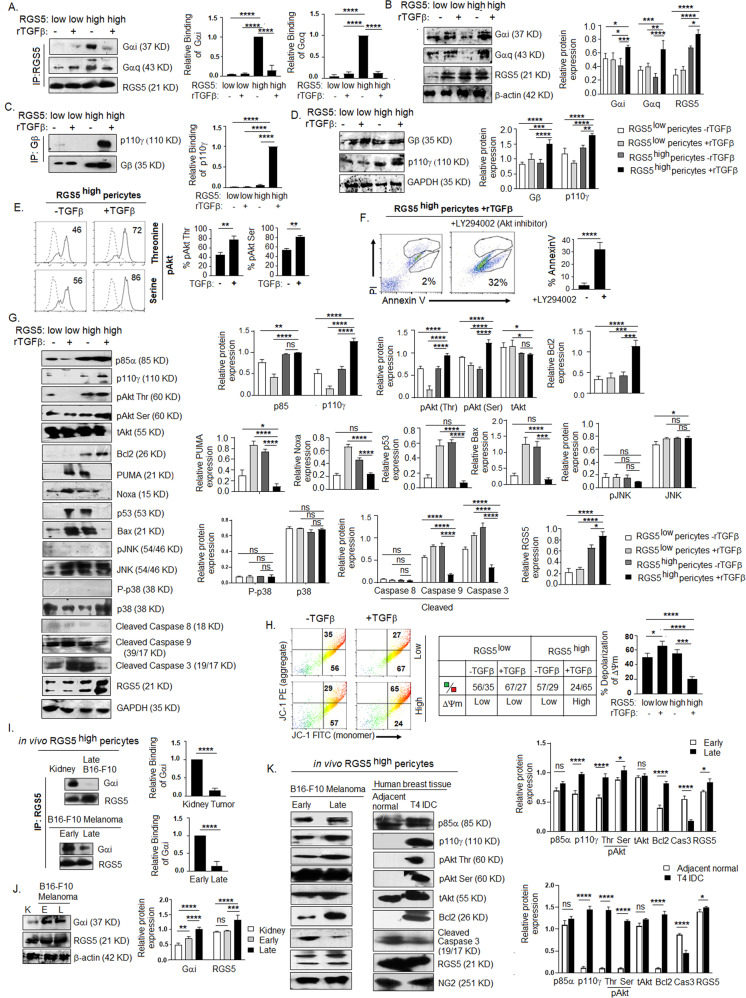

TGFβ interrupts RGS5-dependent apoptotic programming in RGS5highpericytes by targeting RGS5–Gαi binding

Next, to evaluate RGS5-associated downstream interactions in the presence/absence of TGFβ, we treated in vitro RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) with rmTGFβ for 4 h. We observed TGFβ interfered with the binding of RGS5 with Gαi1+2 and Gαq11/14, leading to the termination of subsequent PI3K-mediated pro-survival signaling. Co-immunoprecipitation and subsequent western blotting revealed strong binding between RGS5 and Gαi and/or Gαq/11/14 in RGS5highpericytes in absence of TGFβ, in contrast to RGS5lowpericytes. However, TGFβ treatment significantly reduced pairing of RGS5 with both Gαi and Gαq/11/14 in RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 5A, B), thus downregulating the GTPase activity of Gαi subunit. This prevents the re-association of Gα and Gβγ subunits and therefore initiate PI3K-mediated pro-survival signaling. Further, TGFβ-stimulation in RGS5highpericytes, promotes interaction of Gβ subunit of G-protein with p110γ (Fig. 5C, D). Flow cytometry revealed upregulation of pAkt (Ser/Thr) upon TGFβ-stimulation in RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 5E). Apoptosis of TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes increased on inhibiting PI3K-AKT (by LY294002), suggesting the involvement of PI3K-AKT pathway for survival of RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 5F). Activation of pAkt upon Gβ-p110γ association is confirmed by increased protein expression of p85α (regulatory) and p110γ (catalytic) subunits of PI3K in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 5G). To assess whether PI3K activation is RGS5- or TGFβ- dependent [59], expression of p85α and p110γ was checked following TGFβRs blocking with LY2109761 (10 μmol/ml). TGFβRs inhibition showed no impact on p85α, p110γ and RGS5 in RGS5highpericytes with/wo TGFβ-stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S5A), suggesting TGFβ-TGFβR axis independent activation of PI3K is operational in RGS5highpericytes upon TGFβ stimulation, but downregulates mRNA expression of ALK1, ALK5, TGFβRII, and Smad2/3 (Supplementary Fig. S5B, C)

Fig. 5. TGFβ stimulation inhibits RGS5-Gαi binding and activates downstream PI3K pathway in tumor pericytes.

A In vitro RGS5lowpericytes and RGS5highpericytes (as generated in Fig. 1A) were stimulated with/wo rTGFβ for 4 h. Protein lysates were precipitated with RGS5 antibody and interaction with Gαi/Gαq was assessed by western blotting. Quantification analyses were shown on right (n = 6). ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. B Expression of Gαi, Gαq and RGS5 was checked by immunoblotting with respective antibodies in 10% of total cell lysate (used as input) of RGS5lowpericytes and RGS5highpericytes with/wo rTGFβ-stimulation. Bars represent mean± SD (n = 5) of relative protein expression derived by quantification of respective band intensities using ImageJ software, keeping β-actin as loading control. C RGS5lowpericytes and RGS5highpericytes (as generated in Fig. 1A) were in vitro stimulated with/wo rTGFβ for 4 h followed by precipitation with Gβ antibody. Interaction with p110γ was checked by western blotting. Quantification analyses were shown on right (n = 6) ****p < 0.0001. D Expression of Gβ, and p110γ was checked by immunoblotting with respective antibodies in 10% of total cell lysate (used as input) of RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes with/wo rTGFβ-stimulation. Bars represent mean± SD (n = 5) of relative protein expression derived by quantification of respective band intensities using ImageJ software, keeping GAPDH as loading control. E Representative histogram shows expression of pAkt (serine) and pAkt (threonine) upon +/− rmTGFβ-stimulation as analyzed by flow cytometry. Bars represent mean± SD (n = 5) of percent pAkt (Thr) and pAkt (Ser) positive cells upon +/− rmTGFβ-stimulation. **p < 0.01. F Dot plots represent percentage of AnnexinV+ cells in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes +/− LY294002 (PI3K-Akt inhibitor) treatment. Respective bars obtained by unpaired t-test represent mean± SD (n = 5) of percent of AnnV+ cells in RGS5high pericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) with TGFβ stimulation +/− LY294002 treatment. G Representative figures of protein expression of p85α, p110γ, pAkt (threonine), pAkt (serine) and tAkt, anti-apoptotic Bcl2, apoptotic PUMA, Noxa, p53, Bax, pJNK, P-p38, cleaved-caspase 8, cleaved-Caspase 9, cleaved-Caspase 3 and RGS5 in RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) as examined by western blotting in RGS5high/RGS5low pericytes +/− rmTGFβ-stimulation. Representative data from n = 5 are presented, keeping GAPDH as loading control. Bar diagrams (on right) represent mean± SD (n = 5) relative protein expression calculated by quantification of respective band intensities using ImageJ software. H Involvement of mitochondrial damage or change in mitochondrial-membrane potential was determined by JC-1 staining of RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes w/wo rmTGFβ stimulation and presented with representative flow-cytometric dot plots. Table representing the ratio of JC-1 green: red in pericytes w/wo rmTGFβ stimulation as indicated and bar diagrams represent the percent of depolarization of mitochondrial-membrane potential. *p < 0.5, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. I Protein lysates of RGS5highpericytes isolated from sorted CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ population of murine kidney, early and late B16-F10 melanoma (as in Fig. 3B) were precipitated with RGS5 antibody and interacted with Gαi as checked by western blotting. Quantification analyses were shown on right (n = 6). J 10% of protein lysate was used to assess the expression of Gαi and RGS5 in RGS5highpericytes isolated in vivo, keeping β-actin as loading control. Quantified band intensities are represented with bar mean± SD (n = 6). ****p < 0.0001. K Expression of p85α, p110γ, pAkt (Thr/Ser), tAkt, Bcl2, cleaved caspase-3 and RGS5 in RGS5highpericytes isolated from sorted CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ population (as in Fig. 2A, D) in early versus late solid B16-F10 melanoma and T4 infiltrating ductal carcinoma versus adjacent normal tissue was analyzed by western blot, keeping NG2 as loading control. Bar diagram represents quantified band intensities with mean± SD n = 6 (on right).

We further evaluated the expression of anti-apoptotic/pro-survival protein Bcl2. Notably, RGS5 upregulation in pericytes (in vitro, generated as described in Fig. 1A) resulted in a significant downregulation of Bcl2, whereas TGFβ-treatment in RGS5highpericytes resulted in enhanced expression of Bcl2 (Fig. 5G). Moreover, while assessing mitochondrial-membrane potential, we observed JC-1 primarily exists as green-fluorescent monomer in presence of either RGS5/TGFβ suggesting depolarization of mitochondrial membrane. However, TGFβ-stimulation in RGS5highpericytes showed higher percentage of orange-fluorescent, as JC-1 aggregated within intact mitochondria indicating hyperpolarized membrane potential (supporting cell-proliferation) (Fig. 5H). Furthermore, stimulation with TGFβ prevented the activation of PUMA, Noxa, and p53 in RGS5highpericytes, but not in RGS5lowpericytes, while the absence of TGFβ augmented PUMA and subsequent p53 activation in RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 5G).

PUMA can interact with Bcl2 to release Bax or it may directly activate Bax to promote mitochondrial-membrane permeability [60]. We further observed TGFβ treatment abrogated Bax activation in RGS5high but not RGS5lowpericytes. In absence of TGFβ, RGS5 upregulates Bax, which initiates mitochondrial damage and caspase9/3 activation (Fig. 5G). In contrast, TGFβ prevents caspase 9/caspase 3 activation in RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 5G) without affecting the expression of caspase 8, suggesting an involvement of intrinsic-apoptotic pathway and mitochondrial damage. However, TGFβ-stimulation did not activate non-Smad pathways like JNK or p38-MAPK (Fig. 5G).

As TGFβ levels are higher in late B16-F10-melanoma compared to early B16-F10-melanoma and murine-kidney (Fig. 4E), in vivo tissue pericytes are assumed to be exposed to different TGFβ-levels. Therefore, we isolated RGS5+pericytes from CD31−CD45−NG2+PDGFRβ+ sorted population (as described in Fig. 3B) using BD-Imag and further elucidated that, unlike tumor-uninvolved tissue, altered RGS5-mediated pathway operational only in growing tumors. Co-immunoprecipitation and western blotting showed strong interaction between RGS5 and Gαi in RGS5highpericytes derived from kidney and early B16-F10-melanoma but not in RGS5highpericytes from late tumor (Fig. 5I, J).

Furthermore, increased expression of p85α, p110γ, pAkt (Thr/Ser), and Bcl2 was observed in RGS5highpericytes from late/T4-infiltrating-ductal carcinoma than early tumors/adjacent normal. (Fig. 5K).

Thus our collective data suggest that RGS5, in absence of TGFβ, promotes Gαi/Gαq-βγ association that terminates PI3K-AKT activation and downstream Bcl2, leading to enhanced PUMA/p53/Bax-mediated mitochondrial damage in pericytes. However, in the case of TME, high TGFβ concentrations interrupt RGS5-Gαi binding causing reversal of RGS5-mediated pro-apoptotic programming in RGS5highpericytes.

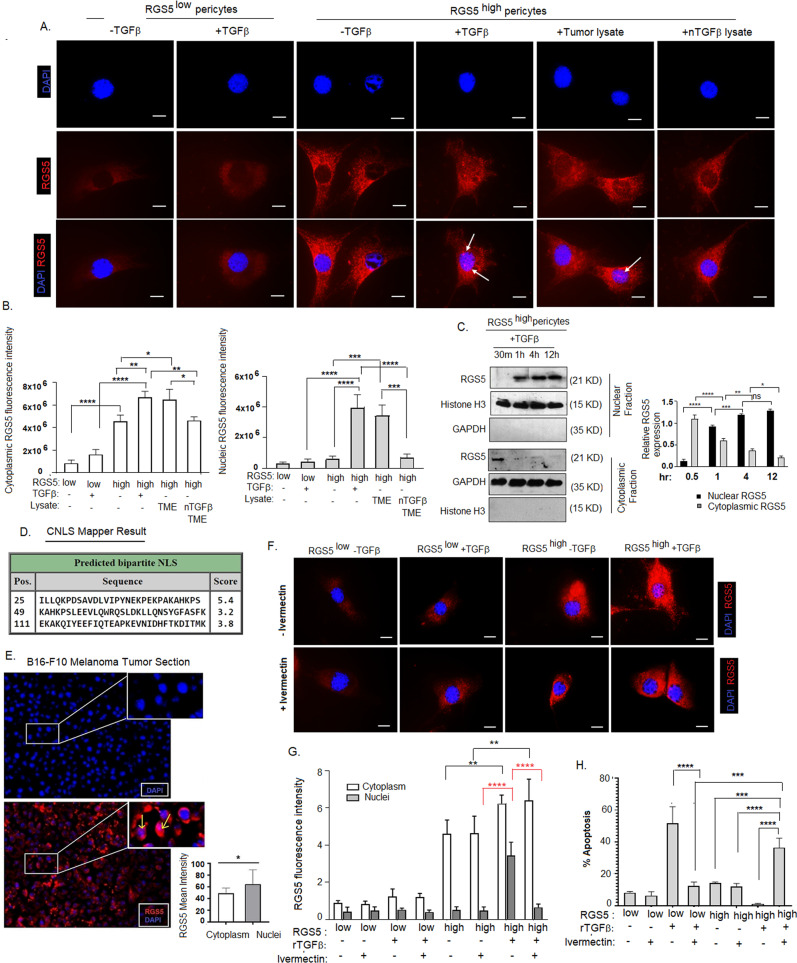

TGFβ promotes rapid nuclear translocation of RGS5 in RGS5hightumor pericytes

As the presence of TGFβ interferes with the binding of RGS5 with Gα, we next investigated the cellular distribution of RGS5 to understand its sub-cellular functions better. Interestingly, nuclear translocation of RGS5 found in RGS5highpericytes exposed to rTGFβ/B16-F10-tumor-lysate in vitro, while in absence of TGFβ, it was localized strictly in the cytosol (Fig. 6A). We observed significantly higher nuclear intensity of RGS5 in TGFβ/tumor-lysate treated RGS5highpericytes compared to RGS5low/highpericytes (Fig. 6B) as measured by ImageJ software. TGFβ-neutralization within TME completely prevented nuclear-localization of RGS5 in RGS5highpericytes. In particular, we observed dominant RGS5 localization in the cytosol of RGS5highpericytes exposed to TGFβ-deplete-media, thus excluding the possibility that RGS5 nuclear-localization occurred as an artifact of forced RGS5 over-expression. Kinetic analyses further suggested that TGFβ promotes nuclear translocation of RGS5 within 30 min, reaching peak at 1 h and maintaining a steady-state till 12 h (Fig. 6C). RGS5 sequence analysis using cNLS Mapper [61] predicted three putative bipartite NLS signals with scores of 3.2, 3.8, 5.4 within the N-terminus of RGS5 (Fig. 6D). Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis of B16-F10-melanomas indicated strong nuclear-localization of RGS5 in the TME (Fig. 6E). Though nuclear localization is a common feature of RGS-proteins [62], the functional ramifications of such trafficking in different cell types remain poorly understood. Treatment of RGS5highpericytes with Ivermectin (a specific inhibitor of importin α/β) [63] prevented nuclear trafficking of RGS5 even with TGFβ-stimulation (Fig. 6F, G) indicating, importin-dependent RGS5 nuclear translocation which subsequently sensitizes RGS5highpericytes to apoptosis (Fig. 6H).

Fig. 6. TGFβ promotes RGS5 nuclear translocation in RGS5highpericytes.

A RSG5low/RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) were cultured in vitro in chamber slides w/wo TGFβ-stimulation, B16-F10 melanoma tumor-lysate and TGFβ neutralized TME as indicated followed by immunostaining with anti-rabbit PE-tagged RGS5 antibody. Nuclei stained with DAPI. Representative images (n = 6) of immunofluorescence are showing cellular distribution of RGS5 in RGS5low/RGS5high pericytes +/− TGFβ stimulation for 4 h. Images were acquired in ×100 magnification with oil immersion. Scale bar represents 50 µm. B Bars obtained by one-way ANOVA following Tukey’s multiple comparison test represent mean +/− SD (n = 5) of cytoplasmic and nuclear RGS5 fluorescence intensity in RGS5low/RGS5highpericytes +/− TGFβ stimulation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001,****p < 0.0001. C Time kinetics for nuclear translocation of RGS5 by western blot at times indicated from nuclear and cytosolic fractions of TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes (as generated in Fig. 1A), keeping GAPDH and Histone H3 as loading controls. Bars obtained by two-way ANOVA following Tukey’s multiple comparison test represent mean +/− SD of quantified band intensity of cytoplasmic and nuclear RGS5 expression (n = 5) of RGS5low/RGS5highpericytes +/− TGFβ stimulation. D cNLS Mapper result generated from RGS5 sequence, indicating RGS5 localization in both cytoplasm and nuclei as score values are greater than 3, 4 and 5. E Fluorescence microscopic analysis of RGS5 (PE-tagged) in B16-F10 melanoma tumor sections, along with DAPI staining in nuclei. Representative figures from n = 6 are presented. Images were taken in ×20 magnification and scale bar indicates 10 µm. A bar diagram acquired by two-tailed unpaired t-test represents RGS5 mean intensity in both cytoplasm and nuclei. *p < 0.05. F Immunofluorescence images of RGS5 in RGS5low/RGS5highpericytes (as generated in Fig. 1A) panel as indicated w/wo ivermectin treatment upon +/− TGFβ stimulation. Nuclei stained with DAPI. Representative data from n = 6 are presented. ×100 magnification with oil immersion were used and scale bar represents 50 µm. G Bars obtained by two-way ANOVA following Tukey’s post hoc test represent mean +/− SD (n = 6) of RGS5 fluorescence intensity both in cytoplasm and nuclei in the panel indicated in (F). **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. H Bar diagram obtained by one-way ANOVA following Tukey’s comparison test represents percent of AnnexinV+ pericytes w/wo ivermectin treatment upon +/−TGFβ-stimulation in RGS5low/highpericytes. ***p < 0.001,****p < 0.0001.

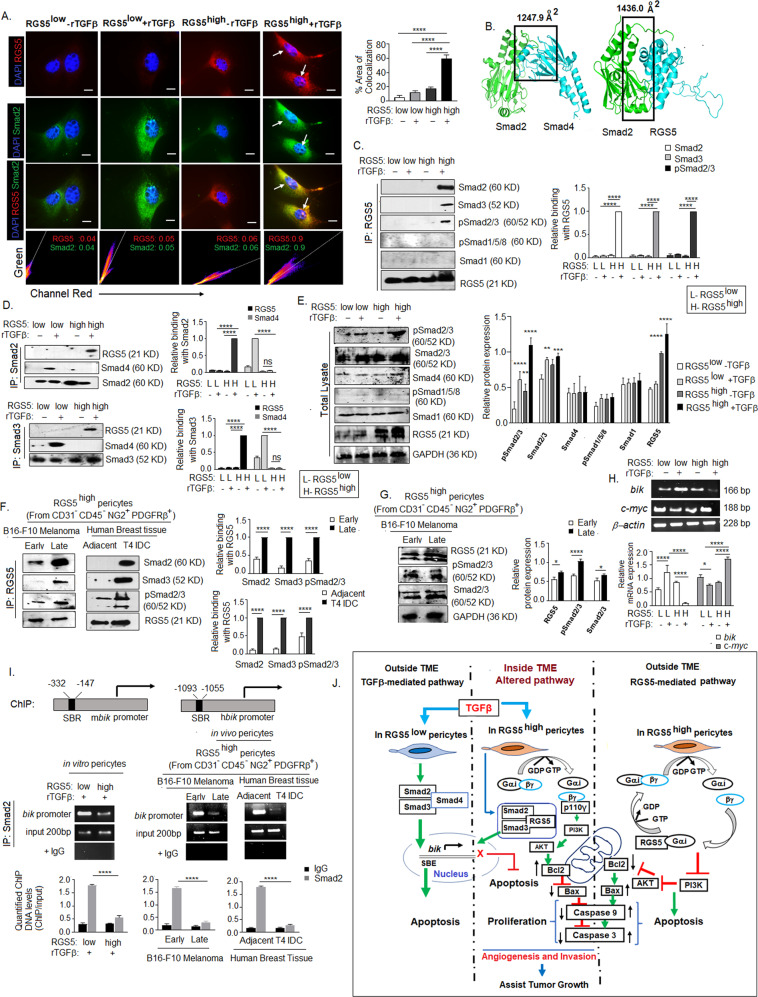

TGFβ differentially regulates apoptotic signaling in RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes

TGFβ induces apoptosis by Smads activation [64]. Phosphorylated R-Smads (Smad1/2/3/5/8) form functional transcriptional complexes with co-Smad (Smad4) upon TGFβ-stimulation, which accumulates in the nucleus and remains maximally nuclear for 4-5 h and initiate specific gene transcription regulating cell death in co-operation with a variety of co-activators [65, 66]. Despite the reported pro-apoptotic nature of TGFβ [67, 68], TGFβ-stimulation prevents apoptosis in RGS5highpericytes, but not in RGS5lowpericytes (Fig. 4D), suggesting an altered pathway. Immunohistochemical studies revealed strong nuclear co-localization of RGS5–Smad2 in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes with Mander’s coefficient value of 0.9 in comparison to TGFβ-stimulated RGS5lowpericytes or unstimulated RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 7A). Moreover, bioinformatic analysis suggests Smad2 shares an identical binding region to interact with RGS5 and Smad4 (Fig. 7F). RGS-domain of RGS5 form complex with MH2 domain of Smad2. In the RGS5–Smad2 complex, the subunits share a larger interface area (1436.0 Å2) compared to the Smad2-Smad4 complex (1247.9 Å2). The common interface residues in Smad2 include Pro360, Gln364-Ala371, Gln389, Leu393, Gln396, Gln400, Phe402-Ala404, Tyr406-Met411, Ala424, Gln429, Pro459, and Val461-Met465. Interestingly, the gain of free energy (ΔiG) upon formation of an interface within the RGS5–Smad2 complex is higher (−14.9 kcal/mol) than that for the Smad2-Smad4 complex (−11.1 kcal/mol) with such interactions hypothetically precluding Smad2/3 and Smad4 association and, their nuclear translocation (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, immuno-precipitation followed by western blotting confirmed interaction between RGS5–Smad2/RGS5–Smad3/RGS5-pSmad2/3 but not with pSmad1/5/8 or Smad1 in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes (Fig. 7C–E). Similarly, interaction between RGS5–Smad2, RGS5–Smad3, and RGS5-pSmad2/3 has been observed in RGS5highpericytes derived from late B16-F10-melanoma and T4 infiltrating-ductal-carcinoma, vs early melanoma and adjacent-normal-tissue (Fig. 7F, G). Formation of RGS5–Smad2 complex prevents interaction between Smad2-Smad4 in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes, thereby perturbing TGFβ-induced apoptotic gene transcription. On assessing the TGFβ-Smads target gene in RGS5highpericytes in presence of TGFβ, we found altered upregulation of c-myc and downregulation of bik in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes vs RGS5lowpericytes, thus ensuring Smad complexes failed to influence the TGFβ-dependent transcription in presence of RGS5 (Fig. 7H). Furthermore, ChIP-assay by Smad2 followed by RT-PCR of Smad-Binding-Region (SBR) present in the promoter of murine and human bik gene (a TGFβ-Smad target gene for cellular apoptosis) suggested that in vitro TGFβ-stimulation in RGS5highpericytes prevent Smad2 binding with SBR of bik promoter resulting suppression of bik transcription, thus preventing TGFβ-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7I). Similar results were observed in RGS5highpericytes derived from late B16-F10-tumors and T4-infiltrating-ductal-carcinoma.

Fig. 7. RGS5 interacts with Smad2 in RGS5highpericytes upon TGFβ stimulation.

A Representative images show co-localization of RGS5 and Smad2 upon +/− TGFβ-stimulation for 4 h in RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes as determined by immunofluorescence microscopy and analyzed by Coloc2 of ImageJ software. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. RGS5 and Smad2 were detected with anti-rabbit PE and anti-goat FITC respectively. Representative 2D intensity histogram shows RGS5 and Smad2 colocalization. Mander’s coefficient close to 1 indicates strong degree of co-localization. Images acquired in ×100 magnification with oil immersion. Scale bar, 50 µm. Bars represent mean+SD (n = 6) percent area of co-localization as analyzed by ImageJ software obtained by one-way ANOVA following Tukey’s comparison test. ****p < 0.0001. B Bioinformatic analysis predicts Smad2 share larger interface area with RGS5 than with Smad4. C, D In vitro RGS5low and RGS5highpericytes (generated as in Fig. 1A) were stimulated with/wo rTGFβ for 4 h. Protein lysates were precipitated with RGS5, Smad2 and Smad3 antibodies followed by western blotting to determine their interactions with co-immunoprecipitated proteins. Quantification analyses were shown on right (n = 6). E 10% of total cell lysate used to assess the expression of pSmad2/3, Smad2/3, Smad4, pSmad1/5/8, Smad1, RGS5 in RGS5low, and RGS5high pericytes upon +/− rTGFβ-stimulation, keeping GAPDH as loading control. Representative data from n = 5 is presented. Quantitative analyses show mean + SD of relative protein expression (right panel). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 or ****p < 0.0001. F Protein lysates from RGS5high pericytes isolated from B16-F10 melanoma (early vs late) and human breast carcinoma (Adjacent-normal vs T4 IDC) were precipitated with RGS55 antibody, followed by western blotting with Smad2, Smad3, and pSmad2/3 antibodies. Quantitative analyses show mean + SD (n = 5) of relative protein expression (right panel). G 10% of total cell lysate used to assess the expression of RGS5, pSmad2/3, Smad2/3. Bars (on right) represented mean +SD (n = 5) of relative protein expression derived by quantification of respective band intensities using ImageJ software, keeping GAPDH as loading control. H mRNA expression of TGFβ target genes bik and c-myc were assessed by RT-PCR, keeping β-actin as loading control. Quantification analyses were shown below (n = 5). I Potential Smad-binding regions (SBR) within mouse and human bik gene promoters. Indicated arrows are for PCR primer positions used in ChIP assay for Smad2 recruitment to the SBE of bik promoter in TGFβ treated RGS5highpericytes. Input was prepared from sheared chromatin prior to immunoprecipitation, with IgG kept as control. Representative RT-PCR following ChIP assay indicated Smad2 binding with SBR of bik promoter. Bars (below) represent mean + SD (n = 5) of quantified ChIP DNA levels with respect to input. J Schematic presentation of the overall pathway discussed. Classical pathway: RGS5 and TGFβ independently induce apoptosis in normal pericytes residing outside tumor microenvironment. Outside TME, RSG5 associates with inhibitory Gαi subunit of G-protein, accelerating GTPase activity, promoting re-association of Gαi subunit with Gβγ subunits thus terminating PI3K-Akt cell survival pathway. TGFβ-dependent apoptosis involves phosphorylation of Smad2/3 following association with co-Smad4 and their nuclear translocation. Activated Smad complexes bind with Smad binding region (SBR) to promote transcription of apoptotic genes (i.e bik) within nucleus. Alternative pathway: Our study showed TGFβ within TME, alters RGS5-dependent apoptosis within tumor-residing pericytes. Under TGFβ influence RGS5 associates with Smad2/3 or pSmad2/3, preventing pSmad2/3-Smad4 complexation. pSmad2/3-RGS5 complex translocate into nucleus preventing recruitment of Smad2 on SBR of bik promoter. Simultaneously, interaction of RGS5–Smad2/3 downregulate GTPase activity of Gα, thereby promote association between Gβγ with p110γ, activating PI3K-Akt survival pathway. Overall the altered pathway facilitates survival and proliferation of tumor-associated pericytes within TME, fostering angiogenesis, invasion and tumor growth.

The overall study describes a differential RGS5-mediated apoptotic pathway outside and inside TME under the influence of tumor microenvironmental TGFβ (Fig. 7J)

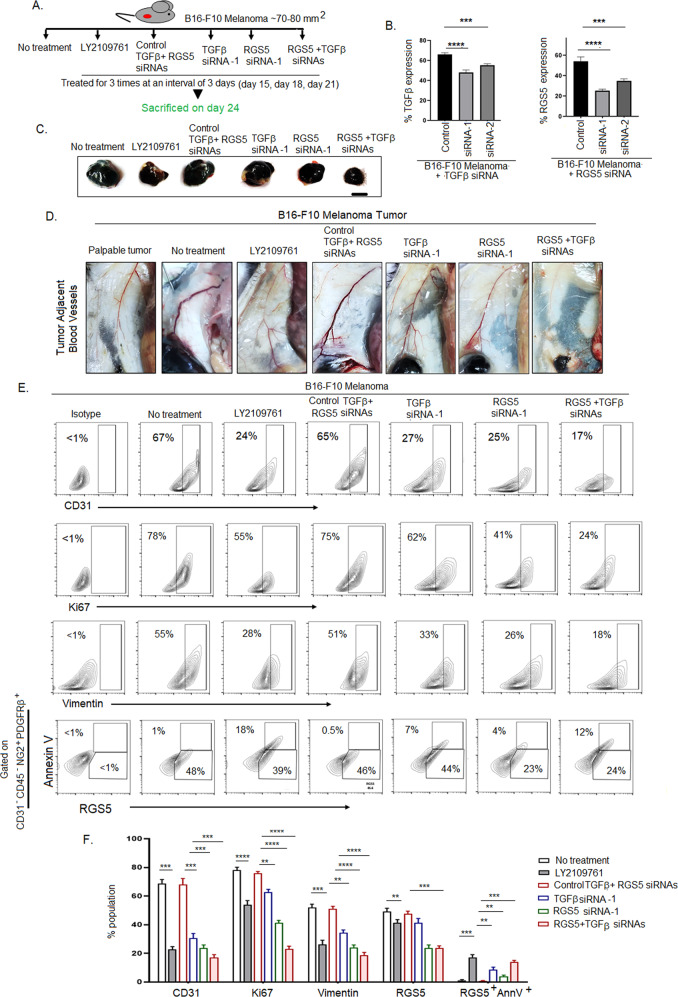

RGS5highpericytes in association with TGFβ contribute to angiogenesis and tumor-growth

Given the strong correlation between the presence of highly proliferative RGS5highpericytes, TGFβ and tumor-growth next we studied the direct impact of these altered-pericytes and the importance of TGFβ-RGS5 axis in tumor. We investigated the in vitro extent of migration, invasion and tube-formation by B16-F10-melanoma cells upon co-culturing with RGS5low and TGFβ-stimulated-RGS5highpericytes (RGS5high + rTGFβ). TGFβ-stimulated-RGS5highpericytes greatly enhance the migration and invasion of CFSE-tagged B16-F10-melanoma and promote early sprouting of tube-like formation (at 3 h) in comparison to RGS5lowpericytes (Supplementary Fig. S6 A–D). Considering the central role of TGFβ in regulation of survival/apoptotic fate in RGS5highpericytes, next we treated B16-F10-melanoma tumor-bearing mice in-situ with TGFβRs inhibitor, LY2109761 (70 µM) (to block downstream effects of TGFβ), RGS5 and TGFβ siRNAs both individually and simultaneously for 3 times at an interval of 3 days (Fig. 8A) using in vivo jetPEI. Intratumoral treatment of B16-F10-melanoma with TGFβ siRNA-1 and RGS5 siRNA-1 efficiently silenced in vivo expression of TGFβ (27%) and RGS5 (54%) respectively in comparison to control siRNA treatment group (Fig. 8B, Supplementary Fig. S7A, B). In vivo short-term knockdown of TGFβ yielded ~35% tumor growth restriction. However, TGFβRs inhibition and RGS5 knockdown alone and with TGFβ restricted tumor-growth significantly, showing ~40%, ~50%, and ~65% reduction, respectively (Fig. 8C, Supplementary Fig. S7C). On analyzing angiogenesis, we observed thinning and a decrease in tumor-adjacent blood vessels and downregulation of CD31 expression in LY2109761 treated and RGS5/RGS5 + TGFβ siRNAs delivered cohorts in comparison to untreated/control siRNAs group (Fig. 8D, E, Supplementary Fig S7D). Similarly, we also observed Ki67 and vimentin (EMT marker) downregulation in LY2109761 treated and RGS5/RGS5 + TGFβ siRNAs delivered cohorts (Fig. 8E, F). These observations showed well-correlation with the enhancement of AnnexinV positivity in RGS5highpericytes gated in CD31−CD45−NG2+PDGFRβ+ sorted cells from tumors (Fig. 8E, F). Therefore, the cumulative data suggest a direct role of RGS5 and TGFβ in promoting the survival of altered-pericytes which might endorse angiogenesis and tumor-growth.

Fig. 8. Targeting RGS5-TGFβ axis restricts tumor growth.

A Pictorial diagram representing the in vivo experimental settings. Each group of mice (n = 6) bearing B16-F10 tumor were intratumorally injected with TGFβRs inhibitor (LY2109761), control RGS5 + TGFβ siRNAs, TGFβ siRNA, RGS5 siRNA, and both RGS5 + TGFβ siRNAs for 3 times at an interval of 3 days. B Bar diagrams representing mean + SD (n = 6) of percent expression of TGFβ and RGS5 upon treatment with respective siRNAs in comparison to control siRNAs by flow cytometry. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. C Representative macroscopic images of tumor (n = 6) as obtained 3 days after last dose of inhibitor/siRNAs as described in (A). Scale bar indicates 5 mm. D Representative figures (n = 6) showing tumor adjacent blood vessels of B16-F10 melanoma tumor bearing mice as treated with inhibitor/siRNAs as described in (A) on day 24. E Illustrative contour plots indicating expression of CD31, Ki67, vimentin along with RGS5+AnnV+ pericyte population gated on CD31-CD45-NG2+PDGFRβ+ population as in Fig. 3B, respectively in tumors derived from (A). F Bars obtained by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test represent mean + SD of percent population of CD31, Ki67, vimentin, RGS5, RGS5+AnnV+ in B16-F10 melanoma tumor following treatment with LY2109761 and RGS5 + TGFβ siRNAs in comparison to no treatment and control siRNAs group respectively. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Tumor stroma along with neo-blood vessels are crucial for cancer progression and simultaneously endorse limited efficacy to chemo- or immunotherapy. Altered interactions and functionality of two important blood-vessel components, e.g. endothelial-cells and pericytes are the major contributors to the creation of chaotic, leaky tumor vasculature in tumor. Substantial evidences suggest chaotic architecture of tumor blood vessels can be reversed by simply manipulating TME without destroying the existing vasculature. Interestingly, a recent work of Ganss group critically pointed RGS5, a member of regulator of G protein superfamily [69, 70] as a prominent marker for angiogenic-vessels, whose downregulation normalizes tumor-vessels [5, 56]. Our previous work along with others also suggested that RGS5 is highly upregulated and enriched in tumor-derived-pericytes causing later to promote several tumor fostering functions including angiogenesis and immune-suppression [5, 11, 56]. Contrastingly, in vitro studies from several groups have shown that induced over-expression of RGS5 in various cell types promote cellular apoptosis [16–18]. In addition to RGS5, other RGS-proteins like RGS3, RGS6, RGS16 can reportedly promote apoptosis as well, supporting a more global anti-proliferative effect for RGS-proteins [71, 72]. However, the frequency of RGS5highpericytes within TME positively correlated with tumor progression [24, 25]. Therefore, an obvious question arises that how RGS5highpericytes persist/flourish within TME despite the known pro-apoptotic tendencies of RGS5.

Our study noticed exposure of RGS5lownormal pericytes to tumor-supernatant+tumor fragments and TZD induced HIF1α and PPARγ dependent RGS5 upregulation respectively [18, 73, 74]. In agreement with previous studies, we found in vitro upregulation of RGS5 promotes cellular apoptosis irrespective of methods used to induce RGS5-expression in pericytes. However, RGS5highpericytes isolated from human/murine tumors expressed comparatively low AnnexinV and cleaved-caspase3 showing resistance towards apoptosis. Interestingly, the expression of RGS5 found to be higher in more advanced form of tumors than early or in situ form in both human and murine tumor models. In corollary mechanistic studies, we determined that interruption of apoptosis in RGS5hightumor-associated-pericytes was solely attributable to extrinsic TGFβ. Elevated TGFβ-levels with tumor progression, which simultaneously resulted in increment of RGS5+AnnV− altered-pericyte population, may be responsible for vascular-abnormality within TME irrespective of tumor nature and anatomical origin.

Our study revealed that outside TME where TGFβ is absent, RGS5 promotes apoptotic death of RGS5highpericytes via a pathway involving the binding of RGS5 with Gαi/q, and subsequent reduction in PI3K/AKT activation [75] and Bcl2 expression [76]. Simultaneously this interaction increases levels of mitochondrial pro-apoptotic proteins; PUMA, Noxa, p53, and Bax, in association with decreased mitochondrial-membrane potential. As a consequence, activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 was observed in RGS5highpericytes. In contrast, within TGFβ-enriched TME, binding of RGS5 with Gαi/q was prevented and subsequently restored RGS5-induced cessation of PI3K-AKT pathway. Moreover, Gβ binds with p110γ, catalytic subunit of PI3K, parallelly contribute to Akt phosphorylation [77]. Consequently, TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericyte express high Bcl2 leading to a blockade of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway [76]. Accumulation of JC1-aggregate within TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes suggests hyperpolarization of mitochondrial-membrane potential [78]. TGFβ interrupts the conventional RGS5-pro-apoptotic signature and ensures the survival of tumor-associated pericytes, whereas TGFβ neutralization in tumor-lysates or inhibiting TGFβ action by blocking its’ receptors resulted in the restoration of apoptosis in RGS5highpericytes. This result is well correlated with tumor-growth prevention upon suppression of TGFβ levels and vascular-normalization [79, 80] within TME by natural immunomodulator [81, 82].

Bioinformatics and protein-protein interaction analysis (using Co-IP and WB) suggested previously unreported interactions between RGS5 and pSmad2/3, downstream functional mediator of TGFβ. Upon TGFβ binding with TGFβ type-II receptor it forms a hetero-tetrameric complex with the TGFβ type-I receptor and phosphorylate R-Smads, which then bind to the co-Smad, Smad4. The resulting hetero-oligomeric Smad2/3/4 complex then accumulates within nucleus to control transcription of gene products associated with cell survival and apoptosis [83]. But in TGFβ-stimulated RGS5highpericytes, Smad2/Smad3 or pSmad2/3 binds with RGS5 with higher affinity using a similar molecular interface uses for binding to Smad4 (in the absence of RGS5). Thus, in presence of intrinsic RGS5, complex formation between Smad2 and Smad4 would become sterically implausible which further restrain the binding of Smad transcription complex to the Smad-Binding-Element (SBE) or CAGA box in bik promoter. ChIP-assays also confirmed that in presence of RGS5, TGFβ-stimulation fails to recruit Smad2 on the SBE of the bik promoter, whereas TGFβ would normally induce transcription of bik [43, 84].

Surprisingly, we also found RGS5 to be translocating into nucleus after TGFβ-stimulation. Whereas an importin α/β inhibitor prevents RGS5 nuclear trafficking and caused retention of this molecule in the cytoplasm, where it sensitizes pericytes to apoptosis. It is reported that RGS3, interacts with MH2 domain of Smad transcription factors (R-Smad2/3/co-Smad4) via a region outside RGS-domain that has no significant homology with other RGS-proteins, abolishing Smad3-Smad4 association. And such RGS3-Smad interaction inhibits TGFβ induced myofibroblast differentiation [85].

However, this is the first report to our knowledge regarding the nuclear translocation of RGS5 and RGS5–Smad2/Smad3 complex. Sequence analysis of RGS5 using cNLS Mapper software predicted bipartite NLS presence in the N-terminus, and bioinformatic studies suggested a high probability (0.94) for DNA binding. However, future studies will be required to further detail the trafficking and consequence of nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttle of RGS5 within the context of cancer and other pathological conditions.

In our model, we briefly tried to analyze the impact of RGS5high functionally altered pericytes in tumor growth. Inhibition of TGFβ-signaling for a short-span of window using TGFβRs inhibitors sensitized RGS5highpericytes to apoptosis, which simultaneously normalize tumor vasculature with a modest shrinkage in tumor-volume. Furthermore, short-term intratumoral knockdown (within 10 days span) of either RGS5 alone or RGS5 and TGFβ simultaneously showed significant tumor-growth restriction compared to only TGFβ knockdown cohort or untreated cohort. In agreement with observations from Ruth Ganss group such tumor-growth inhibition is corroborated with downregulation of angiogenesis, tumor proliferation, and metastatic initiation [5, 56, 86]. Thus TGFβ-RGS5 pathway could serve as a target for vascular normalization or tumor-growth restriction. However, a more detailed study is required to validate the importance of the TGFβ-RGS5 axis in altered-pericytes dependent angiogenesis, metastasis, and tumor progression.