Abstract

Background

The duration and magnitude of the coronavirus (COVID-19) posed unique challenges for nursing students, whose education was altered because of the pandemic.

Purpose

To explore the perceptions and experiences of nursing students whose clinical rotations were abruptly interrupted by COVID-19's initial surge in the United States.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted at a midwestern, academic medical center to elicit senior nursing students' experiences. An online survey was administered with eight open-ended questions asking about: initial impressions of the pandemic; experiences of being a senior nursing student; sources of stress and coping mechanisms; preparing to work as a registered nurse; and views on the nursing profession.

Results

Among the 26 students who completed the survey, the majority were female (92%), aged 28 ∓ 4.1 years. A total of 18 subcategories emerged with four main themes identified as: a) breakdown of normal systems, b) feeling alone and the inability to escape, c) protective factors/adaptability, and d) role identify and formation.

Conclusions

Findings indicate students implemented a variety of strategies while adapting to the abrupt interruption of in-person clinical rotations, mandated restrictions, and social unrest. The cascading themes illustrate the enormity of sudden changes and their significant impact on daily life.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Nursing students, Perceptions & experiences, Clinical rotations, Social unrest

Introduction

Nursing is the largest segment of the healthcare profession and responsible for providing the majority of direct care to patients in acute, ambulatory, and long-term care settings (AACN, 2019). Nurses have been at the forefront of responding to the current coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic as well as other global infectious disease outbreaks (Goni-Fuste et al., 2021). While literature has emerged describing healthcare providers' experiences during these infectious outbreaks (Honey & Wang, 2013; Kim, 2018; Liu et al., 2019), the COVID-19 pandemic poses unique challenges for nurses because of the duration and magnitude of responding to this health crisis (Sun et al., 2020). Of particular importance is the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on nursing students, the next generation of healthcare providers.

Review of the literature

A few studies have emerged describing nursing students' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lovrić, Farčić, Mikšić, and Včev (2020) provided one of the first qualitative studies describing the perceptions and experiences of 33 undergraduate Croatian nursing students who were studying as the pandemic erupted. Nursing students expressed an understanding of why the mode of education delivery was changed, felt grateful to school staff, fearful of infection, dismayed by society's dismissal of needed precautions, and looked to the importance of the nursing field. Casafont et al. (2021) interviewed 10, fourth-year nursing students whose clinical placement was interrupted by the national lockdown in Spain and who were contracted to work as healthcare aids. These nursing students expressed ambivalent emotions in terms of excitement for the new experience and to help out, but uncertainty and fear at the beginning with not knowing what to expect or do. They also conveyed a sense of adaptation by adjusting to new safety protocols, normalizing routines, and adjusting to the stress of providing care for infected patients. Another qualitative study explored the perceptions of 62 senior nursing and medical students in Spain, many of whom (85.5%) volunteered to join the healthcare system workforce as part of the government's measured response efforts to the pandemic (Collado-Boira et al., 2020). The semi-structured interviews revealed students' negative emotions, such as fear, anxiety and concern of transmitting the disease to their family. Martin-Delgado et al. (2021) analyzed 40 reflective journals that were required for final-year Spanish nursing students when traditional clinical placement was altered, and many of whom joined the healthcare workforce early during the COVID-19 outbreak. Students conveyed a willingness to help out along with a sense of growth and learning, but they also expressed being overwhelmed, fearful, and isolated.

Clinical practical experience is required and an essential component for nursing students and can be a challenging time while learning new critical skills, integrating into the healthcare team, and navigating one's professional identity. The COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted clinical placements and experiences for nurses worldwide (Goni-Fuste et al., 2021). While a number of recent European studies have examined student experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lovrić et al., 2020; Martin-Delgado et al., 2021; Monforte-Royo & Fuster, 2020), we are aware of one qualitative and two cross-sectional reports specifically focusing on United States (U.S.) nursing students (Keener, Hall, Wang, Hulsey, & Piamjariyakul, 2021; Rosenthal et al., 2021; Wallace, Schuler, Kaulback, Hunt, & Baker, 2021). To understand the experiences of transitioning to remote learning, Wallace et al. (2021) interviewed 11 junior and senior nursing students enrolled in a baccalaureate program in the Pacific Northwest, the geographical region of the first confirmed travel-related case of coronavirus in January 2020 (CDC, 2020). Students expressed challenges with technology and professors unfamiliar/struggling with delivering content online. Students also conveyed a sense of isolation and concerns about finances and family dynamics. Some students relayed a sense of resilience during remote learning by being self-directed, resourceful, and recognizing one's strengths and time for self-care. In a cross-sectional study involving 152 nursing students in the Appalachian region, resilience, having previous online learning experience, and being well prepared for online learning were associated with four quality of life domains (physical health, psychological, social relationship and environment) (Keener et al., 2021). Cultivating resilience and promoting students' quality of life may improve academic success. Another cross-sectional study examined the impact of COVID-19 among 222 graduate level nursing students' stress and mental health (Rosenthal et al., 2021). While the majority of students scored within normal levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, the abrupt discontinuation of clinical rotations was noted as a contributing source of anxiety and concern among masters and doctor of nursing practice students. These studies highlight the importance of understanding students' mental health and well-being as external stressors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the enormous demands of nursing school can manifest underlying challenges.

In March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was escalating in the Midwestern U.S., colleges and universities transitioned to remote learning and halted in-person clinical practicum experiences. A recent literature review exploring new nurses' readiness to practice found that clinical practicum experiences were the key factor in feeling prepared to transition and practice as a registered nurse (RN) (AlMekkawi & El Khalil, 2020). Therefore, this study explored the perceptions and experiences of nursing students whose clinical rotations were abruptly interrupted by COVID-19's initial surge in the U.S.

Methods

Design, setting, and sample

This descriptive, qualitative study was conducted at a midwestern, urban academic medical center to elicit perceptions and experiences of nursing students' during the COVID-19 pandemic. A purposeful sample was eligible if they were Generalist Entry Masters (GEM) nursing students whose final year occurred during 2020, with convocation dates in summer and fall (referred to as Cohort A and Cohort B, respectively). The GEM program is a direct entry master's program for students who already have a bachelor's degree in another field and want to pursue a career in nursing. Exclusion criteria included nursing students who were not in their final year after March 2020 or did not complete their graduate studies at the medical centers' university. This study received institutional review board approval from Rush University Medical Center.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete demographic questions related to age, gender, previous work experience, and for the recently graduated nurses, if they had registered to take or completed the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX), and employment status. Open-ended questions were written to encourage participants to express their perceptions and experiences. There were eight open-ended questions specifically asking: initial thoughts about the pandemic; impressions since the pandemic was declared in March 2020; experiences of being a nursing student during the pandemic; sources of stress; stress alleviators and coping mechanisms; preparing to start working as a RN; and view of the nursing profession (Table 1 ). These eight questions were reviewed by a qualitative expert (RH) for face and content validity.

Table 1.

Open-ended survey questions.

| 1. | Describe your initial thoughts about the Covid-19 pandemic. |

| 2. | Tell me about how your impressions of Covid have changed since the pandemic was declared in March. |

| 3. | Tell me about your experience of being in the final months of nursing school during the Covid pandemic. Can you share an example of a particularly meaningful experience? |

| 4. | 2020, the year you planned to graduate, has been one full of stressors. Can you describe some of the biggest sources of stress during this time? |

| 5. | What helped alleviate stress? |

| 6. | What made it harder to cope? |

| 7. | Tell me about what's helped you feel ready or prepared to start working as a nurse. |

| 8. | Describe how the pandemic has impacted your view of the nursing profession and how you envision your role as a nurse. |

Procedures for data collection

To follow social distancing recommendations and COVID-19 related restrictions, nursing students from Cohorts A (n = 71) and B (n = 74) were recruited to participate via email. An invitation email was written by the investigators and sent to the GEM program director who then forwarded it to nursing students, ensuring that only members of the 2020 cohorts in their final clinical rotations would be recruited. The email invitation contained general study information, the waiver of consent, and if a student/nurse was interested in participating, there was a direct link to gain access to the study.

Data were collected using an online survey through REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based platform to support data capture, such as managing online survey data (Harris et al., 2009, Harris et al., 2019). This online platform granted eligible participants confidentiality as responses remained anonymous and sufficient time to thoughtfully respond to questions in writing rather than being interviewed. Furthermore, to minimize biases and to encourage neutrality, investigators were not directly involved with study participants. The survey was available to students from late November 2020 to mid-January 2021. The survey was open for this length of time to account for the holiday season as well as the imposing second surge of COVID-19. One email reminder was sent to students by the GEM program director. In addition, one student from Cohorts A and B offered to post in the cohort-specific Facebook groups a notice to reference the reminder email; the link was not included in this post to ensure that only students with access to the original email would be able to respond.

Data analysis

A method of inductive content analysis was used to describe the phenomenon of nursing students' experiences (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). At the time of developing this study, very little was known and reported concerning perceptions and experiences among senior nursing students since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic which posed challenges to select a theoretical framework to guide this study. Therefore, using a conventional inductive content analysis approach enabled the investigators to move data from the specific to the general, thereby providing a means of describing the phenomenon and to generate knowledge.

Inductive content analysis includes open coding, creating categories, and data abstraction. As part of the initial step of analysis, two investigators independently reviewed the data to create codes, sub-categories, and main categories. The second step of analysis was to review the respective codes, jointly discuss the coded data, and establish a consensus of data organization. In our study, rigor was met by independent coding (by BAS & KD) followed by an additional independent review (by RH), which revealed substantial consistency between the two code sets. Next, the three authors conferred and developed a consolidated set of codes that best reflected the data. Creating categories rendered an understanding of the phenomenon and data abstraction provided a means to generate and name categories. Saturation was established by hearing similar stories across the substantial sample of 26 participants. Trustworthiness was reflected by the precision of the process used in collecting the data, the collection tool of REDCap maintaining a secure and consistent data collection process, and a predetermined coding process used by both coders.

Results

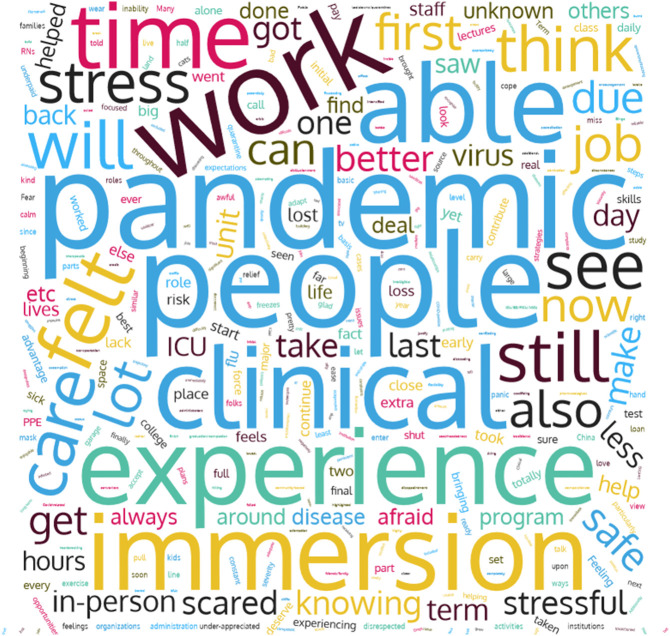

Thirty-five students responded to the survey and confirmed reading the informed consent (24%), however nine were excluded from analysis because of substantially incomplete data. Among the 26 students who completed the survey (18%), the majority were female (92%), aged 28 ∓ 4.1 years, and nearly evenly split between Cohort A (42%) and B (58%) (Table 2 ). Among the Cohort A students who had graduated just prior to responding to this survey (n = 11), the majority completed NCLEX (73%) and nearly half were employed (46%). A total of 18 subcategories emerged with four main themes identified: a) breakdown of normal systems, b) feeling alone and the inability to escape, c) protective factors/adaptability, and d) role identify and formation (Table 3 ). Illustrative quotations are provided and noted with corresponding identification numbers in parentheses. Additionally, students' perceptions and experiences are highlighted in the word cloud image shown in Fig. 1 . This word cloud image captures frequent words expressed by students as they described their experiences. Word cloud images are useful as a visual representation of qualitative data.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Students who completed consent only | 35 (100) |

| Students who fully completed survey | 26 (74.2) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 24 (92.3) |

| Other | 2 (7.6) |

| Age | |

| Mean | 28 |

| SD | +/−4.13 |

| Cohort membership | |

| Cohort A – convocation August 2020 | 11 (42.3) |

| Cohort B – convocation December 2020 | 15 (57.7) |

| Previous career before entering GEM program | 18 (69.2) |

| Additional question for Cohort A | 11 (100) |

| NCLEX completed | 8 (72.7) |

| NCLEX scheduled | 1 (9.1) |

| NCLEX not yet taken or scheduled | 2 (18.2) |

| Currently employed | 5 (45.5) |

Data displayed as n (%).

GEM = general entry masters.

NCLEX = National Council Licensure Examination.

Table 3.

Overview of main themes and subcategories.

| Main theme | Subcategory | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Breakdown of normal systems | 1. |

|

| 2. |

|

||

| 3. |

|

||

| 4. |

|

||

| II. | Feeling alone & inability to escape | 5. |

|

| 6. |

|

||

| 7. |

|

||

| 8. |

|

||

| III. | Protective factors/adaptability | 9. |

|

| 10. |

|

||

| 11. |

|

||

| 12. |

|

||

| 13. |

|

||

| 14. |

|

||

| IV. | Role identify & formation | 15. |

|

| 16. |

|

||

| 17. |

|

||

| 18. |

|

||

NA = nursing assistant.

Fig. 1.

Word cloud image highlighting student perceptions and experiences.

Breakdown of normal systems

The first theme that emerged reflects students' overall fears, concerns, and disappointments and how they perceived the unfolding events of the pandemic as a breakdown of normal activity. Students expressed feelings of shock as the pandemic altered daily activities. One student described, “initially I was scared and shocked by knowing that we needed to stop going to classes immediately (and we've been going for a couple weeks after the outbreak started in the U.S.)” (S13). Students also expressed fears, coming from a variety of sources, as one noted, “When it initially started to spread, I realized how serious it was…I was very afraid for my family. There were so many unknowns that it made me afraid” (S21). Additionally, many students expressed feeling disheartened and concerned, especially by the perceived absence of leadership, as noted by the following: “COVID-19 is a deadly disease and the lack of leadership or intelligible, prudent, and unified plan based on the best evidence to protect the public and essential workers has been disheartening” (S7). There was an underlying sense of disappointment expressed by several students and compounded by the magnitude of social unrest occurring simultaneously as reported by the following: “The election. The complete mismanagement of a pandemic and social uprising …. at the same time” (S19). Another student conveyed, “Since March, I've oscillated between a real solid belief in our abilities to collectively curb COVID transmission yet disillusionment with social and political factors that set us back” (S18). Other students' comments revealed disappointment stemming from shifting attitudes about the people around them. “My impressions of American society have changed. I'm horrified that most people don't care unless it affects them personally” (S1). Many students described a 180-degree shift in their own understanding of the pandemic. One student recalled thinking the initial response was “embellished” and “exaggerated,” and that the “livelihood of the public was more important” to later shifting to “I have realized that the initial response was essential in lowering cases” (S16). Another student described an initial impression as “a bit naive in thinking that it wouldn't cause as much havoc” to further morphing into being “terrified” (S20).

Students were also affected by their learning environment being abruptly altered as one conveyed, “I was anxious about what would happen with my education and career” (S21). Student perceptions of the school's administrative response varied, with some recounting a negative experience as one expressed:

“Feeling disrespected by the university really made this last term difficult. I felt the messages of ‘flexibility’ and ‘patience’ were used to keep us from questioning a lot of what happened. I understand major changes were needed due to the precautions, but students lost everything they paid for and were forced to accept it.”

(S15)

Some students cited the school's messaging as a source of distress, explaining, “the lack of communication from the college of nursing. No one really knew what was going on and what plans would change each day, but they rarely acknowledged the stress that it was causing us” (S16). However, others disagreed and found the administration's handling supportive, saying: “my faculty, colleagues and unit leadership reinforced this sense of comfort because our communication remained clear and proactive as we adapted to rapidly changing information and increased knowledge about the pandemic” (S18). The barrage of evolving information, and the distorted facts that often accompanied them were also sources of distress for many students, with one explaining, “I had to delete my Facebook profile because the constant stream of misinformation and woe was negatively affecting my mental health” (S1).

Feeling alone and inability to escape

A second theme that emerged pointed to a pervasive sense of being alone and how students characterized the confluence of stressors as being unable to escape from the situation. Students found the isolation stressful and felt confined, as illustrated by one describing: “feeling totally isolated and trapped inside my apartment” (S7). Students also revealed missing relationships and socializing with others as contributing factors to feeling alone, as illustrated by:

“Being a hazard to be around others and not being able to see family because I am frequently exposed to COVID in my line of work…not being able to meet new people or spend time with a lot of my friends that are not in my bubble.”

(S19)

A loss of boundaries and the way the pandemic infiltrated home-life was apparent as one student identified a source of stress as: “sharing a space with a partner who also has to be on Zoom all day…and navigating our schedules” (S10). Echoed another student, “It was a huge adjustment of doing everything over Zoom at home because I always made it a point to separate stress from work and school from being at home…I wanted my apartment to be a ‘stress-free’ place” (S13). Students conveyed a sense of loneliness and isolation that ensued as one described:

“It has been brutal. This is a very tough program and to go through it without the in-person support and study time with peers has been very difficult. It also made clinical experiences more challenging, as the nurses we were working with were exhausted, overworked, underpaid, and burnt out.”

(S10)

Another student shared an acute sense of loss, as noted: ‘Loss of what a “normal” end of program would've been and loss of valuable experience through my immersion externship’ (S15). The loss of typical experiences was cited frequently, as another student revealed:

“I feel like my cohort is particularly close, and not being in person with each other to support each other or help each other learn was very tough. We tried our best in online learning and online clinical, but there was still this disconnect.”

(S21)

Students felt constantly reminded of the stressful situation with no clear path for relief, as illustrated by:

“All of my usual coping mechanisms have been inaccessible in this time. It feels like there has been no escape from current events and the state of the world. Trying to focus on learning while it feels like the world is burning around us has been hard, distracting, and has often felt hopeless.”

(S7)

Another student explained, “COVID's effects on my colleagues and patients were everywhere…my patients' chief complaints were acute medical emergencies associated with their grief for loved ones lost due to covid, intensified by poverty and isolation in lockdown” (S18). Students' comments reflected the long-term uncertainty during this time, “I also just thought it would last maybe a month, then we would have it figured out like other outbreaks we have had. When a month went by and things were worse, I felt a lot of anxiety about how long this was really going to take” (S13).

Protective factors and adaptability

A third theme that emerged illuminates strategies adopted by students to help alleviate the stressors associated with the pandemic. It was important for some students to identify things to do, such as hobbies, and to address self-care needs like staying connected and talking with others. Many students described engaging in physical activities, practicing yoga and meditation, and being outside as techniques to cope with the stress and disruption ensued by the pandemic. For example, one student explained walks were beneficial and that “the summer was a huge stress relief since it was easier to be outside and still be safe” (S13). Communities of support were meaningful as one student described, “Zoom and FaceTime with loved ones saved me from feeling really isolated” (S15). Another student conveyed, “my roommate and I became really close and he got me through the stress of missing people” (S13). “Having a good support system and friends that were going through the same things' along with leadership and mentorship were important” (S25). One student stated: “having a great capstone mentor alleviated most of my project stress” (S15). Interestingly, some students found working to be helpful and indicated that “going to work or clinical where it feels like I can contribute in some way” (S7) helped manage/lessen stress. While some students developed specific strategies to alleviate stress, others expressed a different perspective. One student stated: “I don't think anything really alleviated stress I just got better at accepting that this is how life is now” (S19).

Role identify and formation

Role identify and formation was the fourth and final theme that emerged from the data. Many students stated that in-person clinical was valuable for their education. As one student described: “Being able to do my immersion (our last clinical rotation, where we are on a unit with a preceptor) in-person was very meaningful to me” (S1). Another student stated: “this final immersion is most important before starting as a RN” (S16). Additionally, working as a nursing assistant was beneficial to gain patient care experience as one student explained: “I had many more meaningful experiences as a nursing assistant during COVID, such as assisting patients to talk to their loved ones, provide end-of-life care, and contribute to the emotional support of employees” (S16). While students expressed the importance of in-person clinicals, they also voiced concerns of missed opportunities and losing expected milestones along their educational trajectory. One student stated “I hated logging into clinical, I felt we were being robbed” (S20). Another student described:

“It was stressful because the final months were supposed to be spent gaining a lot of direct patient care hours. Since those were cut short due to COVID … I felt nervous that I would not feel prepared as a new grad RN. During the amount of hours we were able to complete, I had many patients tell me that the work nurses were doing was meaningful and appreciated. It made me feel I was ready to graduate and become a nurse during this time.”

(S22)

Students expressed a range of concerns about their educational formation, as noted: “Not being able to have the same experiences and feeling less prepared to enter the workforce. Not having the same job opportunities because hospitals are hiring at lower rates due to income loss from pausing elective surgeries” (S19). Many students expressed how the pandemic brought to light the nursing profession. One student conveyed, “the pandemic has immensely impacted the nursing profession, widespread awareness occurred where people saw the true role of the nurse. I hope to contribute to my community as a future nurse” (S14). While admiration and respect for the nursing profession was noted, some students voiced concerns about how hard nurses work and at times being underappreciated, as noted:

“If you dig beneath the surface of the ‘Heroes Work Here’ rhetoric, you will find nurses are very much disrespected and taken advantage of by major healthcare institutions. Nurses ultimately are expendable. The horror stories coming out about lack of PPE, dangerous staffing ratios, no hazard pay, forcing nurses to comply or risk termination, these are things that have come out of this pandemic.”

(S15)

For some students, witnessing the working environment during the pandemic highlighted the importance of advocacy as a critical role embedded in nursing, as illustrated by:

“I think nurses are often taken advantage of, and expected to do a great deal with less than ideal resources because they can and have. As a nurse, I hope to advocate for my patients and my coworkers to ensure that care is being delivered long-term without compromising immediate safety.”

(S2)

Discussion

The intent of our study was to explore the perceptions and experiences of nursing students whose clinical rotations were abruptly interrupted by COVID-19's initial surge in the U.S. While literature has emerged describing the experiences of healthcare providers during the pandemic, little has been reported among U.S. nursing students. We observed several findings that may be important considerations as we continue to prepare future generation of nurses.

First, a breakdown of normal systems was identified as a backdrop for these students' realities, including: home life being altered, academic paths becoming unclear, witnessing a healthcare system brought to the brink, a political system that undermined scientific experts, being challenged by calls for racial justice, a political election season filled with conflicting information/misinformation, all while having to choose between isolation to ensure safety and the need to work in an environment with a high risk for infection. While a few recent qualitative and quantitative studies have reported students' perceived emotions and stressors during COVID-19 (Lovrić et al., 2020; Rosenthal et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2021), our study reveals the added complexity nursing students experienced confronting the pandemic which was further heightened by the tumultuous political landscape and turmoil that accompanied actions against social injustices. In a qualitative study (Nelms Edwards, Mintz-Binder, & Jones, 2019) conducted during the Ebola outbreak, nursing students in Texas expressed a similarly “charged” atmosphere in the community, though it was not as pervasive as the one associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and rise for social justice. Our students described the co-existence of both positive and negative emotions which has been reported in other infectious disease outbreaks (Goni-Fuste et al., 2021). For instance, while working and wanting to help others was viewed as a positive experience, there was a fear of unsafe conditions, lack of resources, and possibly spreading the infection to others.

Second, students' accounts of feeling alone and the inability to escape were identified as key experiences during the initial lockdown and abrupt disruption of in-person clinical rotations. Students described the difficult challenges and rigor of the GEM program, and how they had anticipated being able to lean on peers and depend on in-person educational experiences, especially to finish the most important work of their final clinical rotations. This sense of physical isolation was compounded by the blurring of boundaries between schoolwork and home and became acute as students described being handed loss after loss. For some students, there was no ‘stress-free” place as school was being conducted virtually in the confines of their homelife. There was also an expression of loss ranging from the missed opportunities of celebrating milestones with peers and seeing loved ones, to feeling robbed of typical coping mechanisms, such as engaging in daily activities like working out or visiting with family and friends. Feeling alone and isolated were similarly reported by other studies (Martin-Delgado et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2021).

Third, protective factors and adaptability were important facilitators for nursing students to cope with emotions and stressors they experienced. Students developed strategies and techniques to help manage and/or alleviate stress. Consistent with our findings, other studies have reported how students developed a sense of resilience and identified the need for self-care through physical activities, reading, and meditation (Casafont et al., 2021; Keener et al., 2021; Rosenthal et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2021). Some students reflected on the process of adapting to the pandemic, others accepted the situation as a new normal. These perceptions are similar to other recent qualitative studies describing Spanish nursing students' experiences during the first surge of the pandemic (Casafont et al., 2021; Martin-Delgado et al., 2021). Additionally, implementing strategies such as support groups and reflective journaling, and providing additional weekly tutorials were important for nursing students to develop a sense of community as they adjusted to the evolving pandemic. Our findings, along with other recent studies (Martin-Delgado et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2021) demonstrate how nursing students coped and adapted to the sudden disruption of in-person education, particularly clinical rotations. The fact that students in our study already had a bachelor's degree and some life experiences likely impacted how they individually coped with their situation during the pandemic. However, because their backgrounds are so varied it is not possible to make any statements as to how their previous experiences helped or hindered their coping.

Last, role identity and formation were identified as considerable aspects of nursing students' experiences, especially during their senior year clinical rotations. Students described fears, concerns, and anxiety with respect to lack of hands-on experiences when clinical rotations were abruptly halted and/or shortened. Our findings are similar to other studies (Nelms Edwards et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020) in which the acquisition of knowledge and clinical skills is critical for the scholarly formation and professional development of nursing students even in the face of new learning environments resulting from emergent situations. Interestingly, Lovrić et al. (2020) reported students expressing fear about attending in-person clinical, which differs from our findings in which not being able to be physically present evoked feelings of anxiousness, rather than being fearful of the situation. This may, in part, be because the Lovric study occurred days after the lockdown was implemented in Croatia, whereas our study asked students to reflect after they had time to process those initial fears, and turn their anxieties toward what a future without hands-on clinical experience would look like.

Another interesting finding not highlighted in other studies, illustrates how our students envisioned themselves as future nurses. For instance, students expressed a desire to become advocates of the profession, especially after bearing witness to a breakdown of normal systems (the first theme), and encountering the way nurses were both greatly appreciated, but at times left unprotected. This is further supported by students envisioning how to advocate for better conditions rather than expressing a desire to leave the profession. Unlike Ulenaers, Grosemans, Schrooten, and Bergs (2021), in which students were questioning their decision to become a nurse, our findings did not see a preponderance of students dwelling on leaving the profession. This finding is particularly relevant as it will be important to determine whether the duration of the pandemic has impacted students over the long-term as they have transitioned from study-to-work responsibilities.

Limitations

While our study presents several interesting findings, there are limitations to note. First, study participants self-selected and their responses reflected experiences attending a midwestern, urban, academic medical center college of nursing during an emerging pandemic. Second, the students and newly graduated nurses who elected to participate may have felt ready to process and share their perceptions and experiences, and therefore may not be generalizable beyond this group of students. While we did reach data saturation among given responses, there may be perceptions and experiences extending beyond those captured from students and newly graduated nurses who chose not to participate or were uncomfortable sharing information.

Implications for nursing education

As with past disasters and infectious disease outbreaks, nursing students' perceptions and experiences reflect a range of emotions, including fear, worry, uncertainty, isolation, loss, and missed opportunities looming in the context of plans for graduation and future employment. Our findings are consistent with recent studies describing nursing students ‘experiences, however we provide an added dimension as students were grappling with the pandemic compounded by the social unrest and call for justice occurring in many U.S. cities. Students sensed the unease and conflict of our society at large and this compounded their sense of absent leadership in the country and lack of clarity for their own futures in nursing. As nurse educators, it is imperative to support students' needs, offer alternative learning opportunities, and communicate clearly and often so students have positive learning environments. In addition, both faculty and their students should have access to resources for emotional and physical well-being during crisis situations, like natural disasters, infectious disease outbreaks, and social issues. Despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, opportunities for colleges of nursing have emerged such as: engaging students in creative and alternative forms of learning, strengthening relationships among students and faculty, and fostering greater awareness and sensitivity of one another's needs to promote a sense of community.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that students implemented a variety of strategies while adapting to the abrupt interruption of in-person clinicals, mandated restrictions, and social unrest. The enormity of sudden changes and their significant impact on daily life was illustrated with the following cascading themes: a) breakdown of normal systems, b) feeling alone and the inability to escape, c) protective factors/adaptability, and d) role identify and formation. These experiences were not independent of each other but created an ongoing experience of change, uncertainty, fear, adaptation, and loss. This study begins to provide the nuances of student life in a pandemic that upended normal daily activities for over a year.

Funding

This work was supported by the Center for Clinical Research and Scholarship at Rush University Medical Center and the Rush Nurse Research Fellowship program.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AlMekkawi M., El Khalil R. New graduate nurses' readiness to practice: A narrative literature review. Health Professions Education. 2020;6(3):304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.hpe.2020.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) (April 1, 2019). AACN Nursing fact sheet. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Fact-Sheets/Nursing-Fact-Sheet#:~:text=Fact%20Sheets-,Nursing%20Fact%20Sheet,84.5%25%20are%20employed%20in%20nursing.

- Casafont C., Fabrellas N., Rivera P., Olivé-Ferrer M.C., Querol E., Venturas M.…Zabalegui A. Experiences of nursing students as healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A phenomenological research study. Nurse Education Today. 2021;97 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) First travel-related case of 2019 novel coronavirus detected in United States. January 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html

- Collado-Boira E.J., Ruiz-Palomino E., Salas-Media P., Folch-Ayora A., Muriach M., Baliño P. "The COVID-19 outbreak"-an empirical phenomenological study on perceptions and psychosocial considerations surrounding the immediate incorporation of final-year Spanish nursing and medical students into the health system. Nurse Education Today. 2020;92 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni-Fuste B., Wennberg L., Martin-Delgado L., Alfonso-Arias C., Martin-Ferreres M.L., Monforte-Royo C. Experiences and needs of nursing students during pandemic outbreaks: A systematic overview of the literature. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2021;37(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., McLeod L., Delacqua G., Delacqua F., Kirby J., Duda S.N., REDCap Consortium The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey M., Wang W.Y. New Zealand nurses perceptions of caring for patients with influenza A (H1N1) Nursing in Critical Care. 2013;18(2):63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keener T.A., Hall K., Wang K., Hulsey T., Piamjariyakul U. Relationship of quality of life, resilience, and associated factors among nursing faculty during COVID-19. Nurse Educator. 2021;46(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control. 2018;46(7):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wang H., Zhou L., Xie H., Yang H., Yu Y., Sha H., Yang Y., Zhang X. Sources and symptoms of stress among nurses in the first Chinese anti-Ebola medical team during the Sierra Leone aid mission: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2019;6(2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovrić R., Farčić N., Mikšić Š., Včev A. Studying during the COVID-19 dandemic: A qualitative inductive content analysis of nursing students' perceptions and experiences. Educational Sciences. 2020;10(7):188. doi: 10.3390/educsci10070188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Delgado L., Goni-Fuste B., Alfonso-Arias C., de Juan M., Wennberg L., Rodríguez E.…Martin-Ferreres M.L. Nursing students on the frontline: Impact and personal and professional gains of joining the health care workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monforte-Royo C., Fuster P. Coronials: Nurses who graduated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Will they be better nurses? Nurse Education Today. 2020;94 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms Edwards C., Mintz-Binder R., Jones M.M. When a clinical crisis strikes: Lessons learned from the reflective writings of nursing students. Nursing Forum. 2019;54(3):345–351. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, L., Lee, S., Jenkins, P., Arbet, J., Carrington, S., Hoon, S., Purcell, S. K., & Nodine, P. (2021). A survey of mental health in graduate nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Educator, 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001013. Advance online publication. doi:10.1097/NNE.0000000000001013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun N., Wei L., Shi S., Jiao D., Song R., Ma L., Wang H., Wang C., Wang Z., You Y., Liu S., Wang H. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control. 2020;48(6):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulenaers D., Grosemans J., Schrooten W., Bergs J. Clinical placement experience of nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Education Today. 2021;99 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, S., Schuler, M. S., Kaulback, M., Hunt, K., & Baker, M. (2021). Nursing student experiences of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Forum, 10.1111/nuf.12568. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/nuf.12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]