Abstract

Background:

In a recent individual patient data meta-analysis, acupuncture was found to be superior to sham and non-sham controls in patients with chronic pain. It has been suggested that a subgroup of patients has an exceptional response to acupuncture. We hypothesized the presence of exceptional acupuncture responders would lead to a different distribution of pain scores in acupuncture versus control groups, with the former being skewed to the right.

Methods:

The individual patient data meta-analysis included 39 high-quality randomized trials of acupuncture for chronic headache, migraine, osteoarthritis, low back pain, neck pain and shoulder pain published before December 2015 (n=20,827). Twenty-five involved sham acupuncture controls (n=7,097) and 25 non-acupuncture controls (n=16,041). We analyzed the distribution of change scores and calculated the difference in the skewness statistic – which assesses asymmetry in the data distribution – between acupuncture and either sham or non-acupuncture control groups. We then entered the difference in skewness along with standard error into a meta-analysis.

Findings:

Control groups were more right-skewed than acupuncture groups, although this difference was very small. The difference in skew was 0.124 for non-acupuncture-controlled trials (p=0.047) and 0.141 for sham-controlled trials (p=0.029). In a pre-specified sensitivity analysis excluding three trials with outlying results known a priori, the difference in skew between acupuncture and sham-controlled trials was no longer statistically significant (p=0.2).

Conclusion:

We did not find evidence to support the notion that there are exceptional acupuncture responders. The challenge remains to identify features of chronic pain patients that can be used to distinguish those that have a good response to acupuncture treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Despite increases in the quality and quantity of randomized trials testing treatments for chronic pain conditions such as low back pain and osteoarthritis, available treatments tend to produce, at best, small-to-moderate mean effects1-4. There are several explanations,5, 6 but one that is of particular clinical and research interest is that of patient heterogeneity or variability in response to treatment. Since randomized trials testing chronic pain treatments typically focus on average treatment effects in heterogeneous samples of patients, they obscure the wide range of individual responses to treatments.

A compelling argument for achieving better treatment results is to match patients more systematically to the right treatment, which is termed “stratified care”7, 8. The allure of stratified care is that it might better enable patients to be ‘fast tracked’ to the most appropriate treatment, maximizing treatment-related benefit and healthcare resource allocation8, 9. Chronic pain conditions such as low back pain, neck pain and osteoarthritis are suitable for stratified care, since they include heterogeneous patient populations with variation in prognosis, there are numerous treatment options available, and the sheer numbers of patients make it unsustainable for healthcare systems to offer resource-intensive treatments to all6, 10.Determining which patients with chronic pain benefit from which specific treatments is an important direction for research and clinical practice.

A common non-pharmacological treatment for chronic pain conditions is acupuncture.11-14 In an individual patient data meta-analysis of high quality trials testing acupuncture for back and neck pain, osteoarthritis, chronic headache and shoulder pain, conducted by the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration,15 acupuncture resulted in small effect sizes compared to sham acupuncture (~0.2 standard deviations) and moderate effects compared to non-acupuncture control (~0.5 standard deviations). Acupuncture is currently recommended in several clinical practice guidelines for the management of chronic pain conditions including low back pain16 and chronic tension-type headache and migraine17. These guidelines recommend stepped care that involves first offering the patient advice, education and simple analgesics before considering a course of acupuncture,17 or they recommend acupuncture as one treatment option alongside several others, such as exercise and manipulation therapy16. The language of these guidelines reflects the current uncertainty about which patients are most likely to benefit from acupuncture. Guidelines for other chronic pain conditions, such as osteoarthritis, categorize acupuncture as a treatment of uncertain appropriateness for specific subgroups14 and call for future research to identify treatment effect moderators18 or baseline characteristics that identify subgroups of patients more likely to respond.19, 20

Some clinicians who practice acupuncture believe that certain patients are exceptional responders.21 One study of acupuncture for stress identified ‘profound responders’ who exhibited improved heart rate variability.22 One study showed that acupuncturists’ expectations predicted treatment success23 and qualitative research shows some patients experience considerable benefit whilst others experience worsening of symptoms.24 The concept of an exceptional acupuncture responder needs to be evaluated as part of an attempt to understand patient characteristics that predict patient outcome after acupuncture. For instance, if a small number of patients have substantially greater responses to acupuncture than average, this would lead to different research questions about predictors of acupuncture response compared to if there were a normal distribution of acupuncture outcomes. In this paper, we analyzed the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration dataset to identify subgroups of chronic pain patients who might be particularly responsive to acupuncture compared to control treatments..

METHODS

Included trials

Trials included in these analyses were identified through a systematic literature review that has been previously described.15, 25 The search included randomized trials of acupuncture for chronic pain published prior to 31 December 2015 and included only trials where allocation concealment was determined unambiguously to be adequate. Eligible chronic pain types were non-specific back or neck pain, shoulder pain, chronic headache or osteoarthritis, with the additional criterion that the current episode of pain needed to be of at least four weeks duration for musculoskeletal disorders. This search resulted in the identification of 44 trials. As previously noted, the control arms were heterogeneous, including no additional treatment, care following treatment guidelines without acupuncture and additional care in both groups, such as in a trial comparing physical therapy plus acupuncture to acupuncture alone. Additional details on the systematic review are available in the supplemental materials.

Data acquisition

Individual patient data were obtained from 39 trials. Data on the trial-level characteristics of the acupuncture intervention were obtained directly from trialists; twenty-six trials had a sham acupuncture arm, and 25 trials had a non-acupuncture control group. The number of trials with sham control plus the number with non-acupuncture control was greater than the total number of trials because several trials had a three-arm design. One trial with both sham acupuncture and no acupuncture control arms was excluded from the sham acupuncture analysis due to a high risk of bias due to unblinding.26

Outcome

The primary outcome used for this analysis was that defined by the individual study authors. Where multiple criteria were considered in the primary outcome (e.g. a response defined as either a 33% reduction in pain or a 50% reduction in use of pain medication) or if the primary outcome was inherently categorical, we used a continuous measure of pain measured at the same time-point as the original primary outcome. To make the various outcome measurements comparable between different trials, the primary endpoint of each was standardized by dividing by the pooled standard deviation.

Statistical analyses

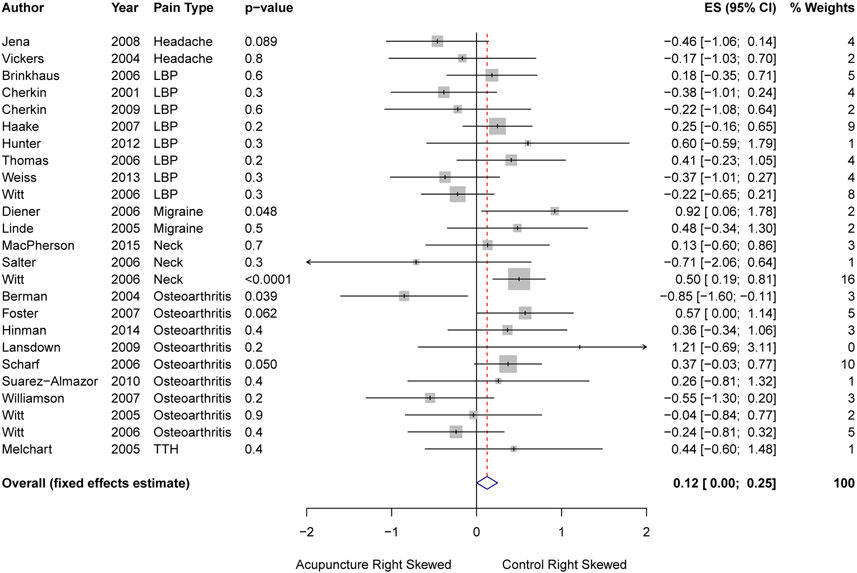

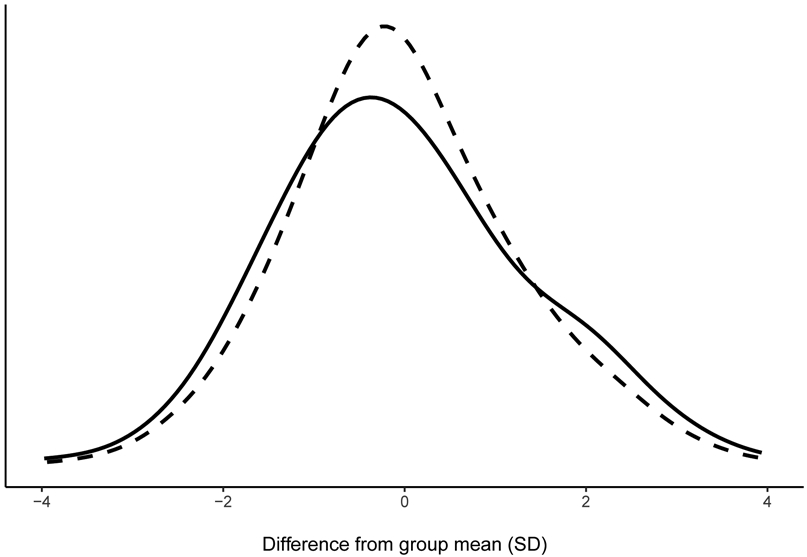

We hypothesised that, if there were a subset of patients who could be classed as exceptional acupuncture responders, the distribution of change scores would be more right-skewed in the acupuncture group than in the control group. This is because the distribution of changes in pain in the acupuncture group would be a mixture of a normal distribution of responses and a small number of patients with very large decreases in pain. We have simulated a graph which shows an example of what the distribution of change scores would look like if there was a subset of exceptional responders in the acupuncture group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simulated figure showing an example of the distribution of change scores in the presence of a subset of exceptional responders in the acupuncture group. The dashed line represents the simulated control group and the solid line represents the simulated acupuncture group.

To test whether the distributions of change scores differed between acupuncture and control, we first calculated standardized change scores for each patient by subtracting their follow-up pain score from their baseline pain score and dividing by the trial-level standard deviation. A positive change score indicates an improvement in pain from baseline, while a negative change score indicates worsening pain from baseline. For each trial, we then calculated the skewness statistic in the distribution of standardized change scores for acupuncture and control groups separately, and computed the difference in the skewness statistic by subtracting the skewness in the acupuncture group from the skewness in the control group. A negative difference in skewness would mean that the acupuncture group was more right-skewed than the control group, which would be the hypothesized result if it were the case that some patients are exceptional acupuncture responders. Using bootstrap resampling, we estimated the standard error for the difference in skewness statistic. The difference in skew and standard error of each trial were then meta-analyzed. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analysis in the sham control arm excluding three trials by Vas et al., which were found in previous analyses to have outlying effect sizes.27-29

Permutation methods were used to test whether there was a difference in skewness in each trial separately. The indicator for group was randomly permuted, and the difference in skew calculated. The p value was calculated as the proportion of 10,000 iterations that the resulting statistic was equal to or greater in absolute size than the skewness calculated for the original data.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 15 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

RESULTS

Distribution of change scores

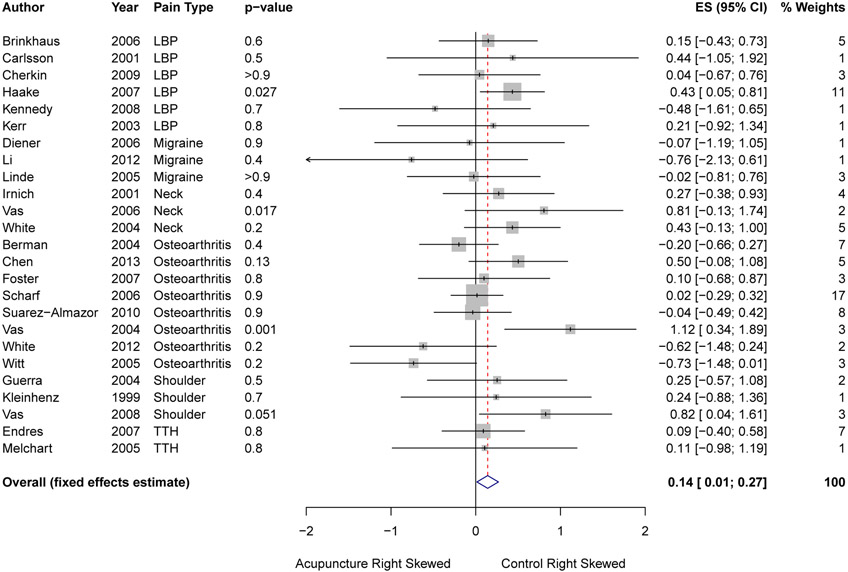

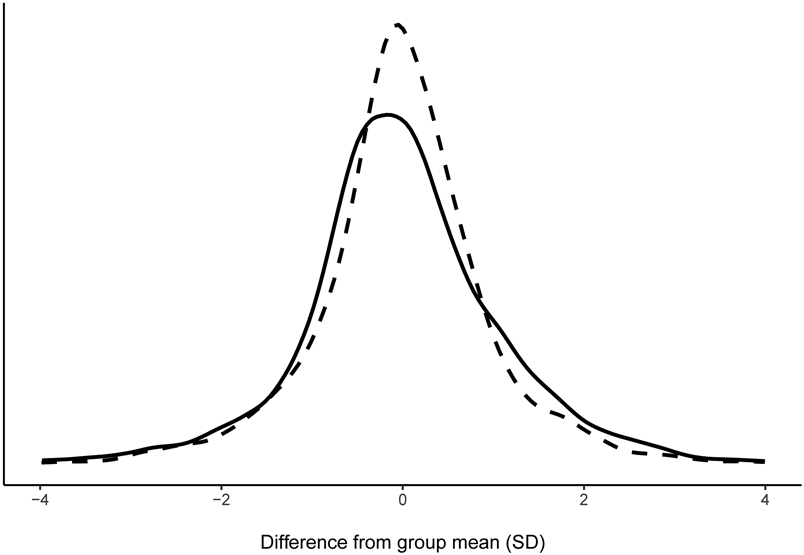

The distribution of change scores for acupuncture and control in trials without sham is shown in Figure 2. The distribution of change scores in the control group was slightly but significantly more right-skewed than the acupuncture group; however, this difference in skewness was very small (difference in skew 0.124, p = 0.047) and likely driven by the large and significant difference in skew in the trial contributing the most weight to the meta-analysis.30 There was significant heterogeneity between trials for the difference in skewness between control and acupuncture groups (p = 0.011). Four of 25 non-acupuncture-controlled trials30-33 (Figure 3) had a significant difference in skew between the acupuncture and control groups. In three of these trials, both the acupuncture and control groups were found to be right-skewed, but the magnitude of skewness in the control group was greater than that in the acupuncture group. In a trial with migraine patients, the skewness in the control group was 1.17, compared to a skewness of 0.25 in the acupuncture group (p = 0.048).31 The control group was offered what was considered standard migraine prophylactic treatment, which included the use of beta blockers and other drugs. While patients in all groups could take drugs for acute pain, the prophylactic drugs were not offered to patients in the acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups. A trial with osteoarthritis patients had a skewness statistic of 0.59 in the control group and 0.22 in the acupuncture group (p = 0.050).33 Similar to the migraine trial,31 this control group received conservative therapy, which involved visits with practitioners and prescriptions for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to be taken as needed. In a neck pain trial, both groups had a positive skew (control group = 1.02, acupuncture group = 0.52, p < 0.0001) and in this trial, control patients were told simply to avoid acupuncture for 12 weeks, and patients in all treatment groups were permitted to use any other conventional treatments for neck pain.30 In another osteoarthritis trial, the acupuncture group was significantly more right-skewed than the control group (p = 0.039), with the control group having a negative skew (−0.47) and the acupuncture group having a positive skew (0.38).32 There was also some evidence that the control group was more right-skewed (0.68) than the acupuncture group (0.11) in an osteoarthritis trial where patients in the control group also participated in an exercise program (difference in skew 0.57, p=0.062).34 Among the other 20 trials, there was no evidence of a significant difference in skewness between acupuncture and control groups.

Figure 2.

Distribution of change scores for non-acupuncture-controlled trials. The solid line represents the acupuncture group and the dashed line represents the non-acupuncture group. The score was calculated for each patient by taking their change from baseline and subtracting the mean change from baseline in the acupuncture or non-acupuncture group depending on the patient’s group assignment.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for difference in skewness between acupuncture and control groups in non-acupuncture controlled trials. A positive difference in skewness means that the acupuncture group was more right-skewed than the control group. P values were calculated by permutation.

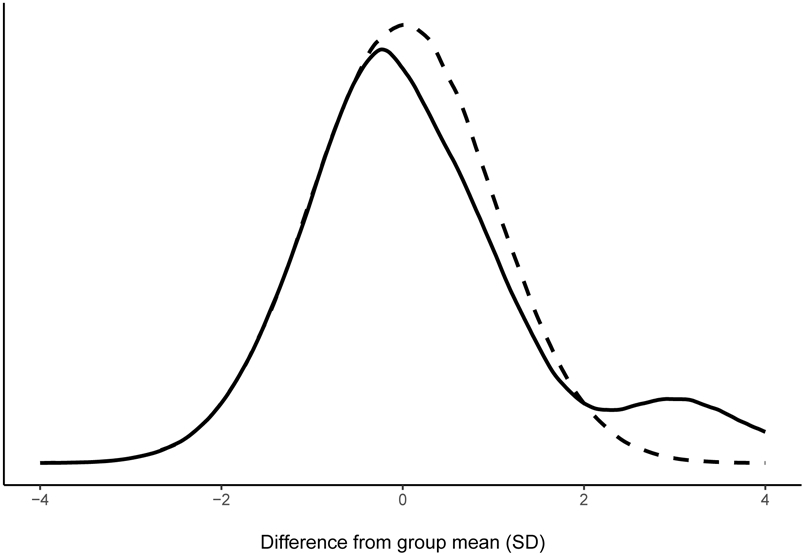

The distribution of pain change scores for acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups in sham-controlled trials is shown in Figure 4. Among sham-controlled trials, the control group was again slightly but significantly more right-skewed than the acupuncture group (pooled estimate of difference in skew = 0.141, p = 0.029). There was insufficient evidence of heterogeneity between sham-controlled trials (p = 0.15, Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Distribution of change scores for sham-controlled trials. The solid line represents the acupuncture group and the dashed line represents the sham acupuncture group. The score was calculated for each patient by taking their change from baseline and subtracting the mean change from baseline in the acupuncture or sham acupuncture group depending on the patient’s group assignment.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of difference in skewness between acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups in sham-controlled trials. A positive difference in skewness means that the acupuncture group was more right-skewed than the control group. P values were calculated by permutation.

In three sham-controlled trials (Figure 5), the control group was significantly more right-skewed than the acupuncture group.27, 28, 35 The largest sham-controlled trial with low back pain patients included 11% of all patients in sham-controlled trials.35 A significant difference (p = 0.027) was found between the left-skewed acupuncture group (−0.24) and the right-skewed sham acupuncture group (0.19). While there was a significant difference, the skewness for both groups in this trial was very small. In addition, sham acupuncture treatment in this trial used penetrating needles, meaning the treatment was more similar to verum acupuncture than sham treatments in other trials. In an osteoarthritis trial, there was also a significant difference in skewness between groups, with the acupuncture group left-skewed (−0.04) and the sham group right-skewed (1.08, p = 0.001).27 Sham acupuncture treatment for this trial consisted of non-penetrating needles applied at traditional acupuncture points. In a neck pain trial by the same group, both the acupuncture (0.28) and sham acupuncture (1.08) groups were right-skewed, although the sham acupuncture group was more right-skewed than the acupuncture group (p = 0.017).28 A disconnected transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machine was used in the sham acupuncture group, and rescue medications were available to all patients. In a fourth trial, on shoulder pain, there was evidence of a difference in skewness between acupuncture (−0.66) and sham acupuncture (0.16) groups in the permutation analysis (p = 0.051) and the 95% confidence interval around the difference in skew calculated in the meta-analysis did not include zero.36 In this trial, there was negative (left) skew in the acupuncture group and positive (right) skew in the sham acupuncture group. As in the neck pain trial by Vas and colleagues,28 a mock TENS machine was used for sham treatment, and rescue medication was available to all patients.

As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded the three trials by the Vas group, since they were found to have much larger effect sizes than average in our main meta-analysis.27-29 After excluding these three trials, the difference in skew between acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups was reduced to 0.08, and this difference was no longer statistically significant (p = 0.2).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of patient-level data from 39 trials, including 20,827 patients, we did not find evidence to support the proposition that some patients are exceptional acupuncture responders. Overall, the distribution of change scores was close to the normal distribution for the acupuncture group, sham acupuncture control group and non-acupuncture control group across the included trials. While the overall difference in skew between acupuncture and control groups showed that control groups were more right-skewed than acupuncture groups, meaning that, if anything, there was more evidence of exceptional treatment responders to the different comparison treatments than to acupuncture, this difference was very small. After excluding three outlying trials, our meta-analysis showed no statistically significant difference in the distribution of change scores between acupuncture and sham acupuncture groups.

Among the set of trials without sham control, those trials with a significant difference in skewness between acupuncture and control groups were mostly those trials with a more active intervention in the control group, for example a physiotherapist-led exercise program34. If a subset of control patients had greater pain reduction from conventional pain treatments, this could have caused the distribution of pain change scores to be more right-skewed in the control group. This would also be the case if control patients were more likely to avail themselves of a treatment (such as prophylactic medication) than patients in the acupuncture group.

Most previous acupuncture literature on patient characteristics has focused on the role of patients’ treatment expectations as predictors of outcome. This literature has reached inconsistent conclusions.37-41 For example, Linde et al. concluded that higher outcome expectations were associated with better outcomes.38 Foster et al. found that those who received the treatment for which they had expressed high baseline expectations of benefit were almost twice as likely to be classified as a treatment responder39. That said, Sherman et al. concluded that pretreatment expectations were not predictive of treatment outcomes40, Thomas et al. found evidence of a reverse effect42 – those with lower expectations did better – and Prady et al. concluded that there was little evidence that preferences cause detectable effects on outcomes in acupuncture trials.41 These different results may be, in part, related to the variation in how treatment expectations were assessed. Several other studies have sought to determine the characteristics of patients with chronic pain who benefit from acupuncture, albeit with much smaller samples. Sherman et al. conducted a secondary analysis of one trial with 638 participants with chronic back pain, and found that the only significant moderator of acupuncture treatment effect in comparison to usual care was higher baseline back-specific disability.43 In an analysis of four trials totaling 9,990 patients with back pain, headache, neck pain, and hip or knee osteoarthritis, Witt et al. found that being female, living in a multi-person household, failing other therapies before the trial of acupuncture and former positive acupuncture experience were all significant treatment effect modifiers.44 Our own prior paper on patient characteristics as treatment effect moderators identified only baseline pain to be a consistent and clinically-relevant moderator of the effect of acupuncture in comparison to other treatments, where patients with higher levels of pain at baseline have a larger response to acupuncture.45

However, these prior papers have attempted to identify specific characteristics associated with acupuncture response (such as baseline pain) rather than directly evaluating the concept of the exceptional acupuncture responder by examining the statistical distribution of outcomes.

Our finding casts doubt on the concept of the exceptional acupuncture responder. Given the approximately normal distribution for pain change scores we report, future research to identify particularly good responders to acupuncture should consider an additive model involving at least some continuous variables. In brief, a normal distribution derives from addition processes – note, for instance, that the distribution of the number of heads thrown on 100 coin flips approximates the normal – whereas skewed distributions often derive from multiplication processes. There are some suggestions in the literature that biological variables, largely as yet unmeasured in clinical trials with chronic pain patients, may help predict acupuncture response, such as β-endorphin and met-enkephalin, descending inhibitory norepinephrine and serotonin46. It remains to be seen whether similar biological variables also might identify responders to other commonly used treatments such as exercise, analgesics or manual therapy. The challenge remains to provide evidence of patient features that consistently identify those who respond to acupuncture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This is a study from the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration, which includes physicians, clinical trialists, biostatisticians, practicing acupuncturists and others. The collaborators within the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration are listed in our primary publications.

Funding:

The Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration was funded by an R21 (AT004189 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to Dr Vickers) and by a grant from the Samueli Institute. Time from Prof Foster, an NIHR Senior Investigator, was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research Professorship award (RP-PG-011-015). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NCCAM, NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health in England. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Data sharing policy: The Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration obtained some data that cannot be publicly deposited as this was a condition of us receiving the data from third parties. All summary data for the trial-level analyses will immediately be made available to investigators on request; requests for individual patient data will be considered on a case-by-case basis depending on the trials involved for the analysis concerned. Such data are fully de-identified.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Contributor Information

Nadine E Foster, Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre, Research Institute for Primary Care and Health Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire, UK.

Emily A Vertosick, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, United States of America.

George Lewith, Faculty of Medicine, Primary Care and Population Sciences, University of Southampton, UK.

Klaus Linde, Institute of General Practice, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany..

Hugh MacPherson, Department of Health Sciences, University of York, UK.

Karen J Sherman, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, United States of America.

Claudia M Witt, Institute for Complementary and Integrative Medicine, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; Institute for Social Medicine, Epidemiology and Health Economics, Charité - Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany.

Andrew J Vickers, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, United States of America.

References

- 1.Patel S, Friede T, Froud R, et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of clinical prediction rules for physical therapy in low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013; 38: 762–769. 2012/November/08. DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827b158f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado LA, Kamper SJ, Herbert RD, et al. Analgesic effects of treatments for non-specific low back pain: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48: 520–527. 2008/December/26. DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 1: Cd005614. 2015/January/30. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005614.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162: 46–54. 2015/January/07. DOI: 10.7326/m14-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pransky G, Buchbinder R and Hayden J. Contemporary low back pain research - and implications for practice. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2010; 24: 291–298. 2010/March/17. DOI: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster NE. Barriers and progress in the treatment of low back pain. BMC medicine 2011; 9: 108. 2011/September/29. DOI: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster NE, Hill JC, O'Sullivan P, et al. Stratified models of care. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2013; 27: 649–661. 2013/December/10. DOI: 10.1016/j.berh.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. Bmj 2013; 346: e5793. 2013/February/07. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.e5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemingway H, Croft P, Perel P, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 1: a framework for researching clinical outcomes. Bmj 2013; 346: e5595. 2013/February/07. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.e5595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter DJ, Schofield D and Callander E. The individual and socioeconomic impact of osteoarthritis. Nature reviews Rheumatology 2014; 10: 437–441. 2014/March/26. DOI: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010: CD001977. 2010/January/22. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001977.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012; 2012: 953139. 2011/December/29. DOI: 10.1155/2012/953139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam M, Galvin R and Curry P. Effectiveness of acupuncture for nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013; 38: 2124–2138. 2013/September/13. DOI: 10.1097/01.brs.0000435025.65564.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2014; 22: 363–388. 2014/January/28. DOI: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 1444–1453. 2012/September/12. DOI: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166: 514–530. 2017/February/14. DOI: 10.7326/M16-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Clinical Guideline C. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Headaches: Diagnosis and Management of Headaches in Young People and Adults. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK) National Clinical Guideline Centre., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2013; 72: 1125–1135. 2013/April/19. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraemer HC, Frank E and Kupfer DJ. Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. Jama 2006; 296: 1286–1289. 2006/September/14. DOI: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fibel KH, Hillstrom HJ and Halpern BC. State-of-the-Art management of knee osteoarthritis. World journal of clinical cases 2015; 3: 89–101. 2015/February/17. DOI: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stux G, Berman B, Pomeranz B, et al. Basics of Acupuncture. Springer, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sparrow K and Golianu B. Does Acupuncture Reduce Stress Over Time? A Clinical Heart Rate Variability Study in Hypertensive Patients. Medical acupuncture 2014; 26: 286–294. 2014/October/30. DOI: 10.1089/acu.2014.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harborow PW and Ogden J. The effectiveness of an acupuncturist working in general practice--an audit. Acupunct Med 2004; 22: 214–220; discussion 220. 2005/January/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopton A, Thomas K and MacPherson H. The acceptability of acupuncture for low back pain: a qualitative study of patient's experiences nested within a randomised controlled trial. PloS one 2013; 8: e56806. 2013/February/26. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic pain: protocol of the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration. Trials 2010; 11: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinman RS, McCrory P, Pirotta M, et al. Acupuncture for chronic knee pain: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 2014; 312: 1313–1322. 2014/October/01. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vas J, Mendez C, Perea-Milla E, et al. Acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. Bmj 2004; 329: 1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Mendez C, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomised controlled study. Pain 2006; 126: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vas J, Ortega C, Olmo V, et al. Single-point acupuncture and physiotherapy for the treatment of painful shoulder: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47: 887–893. 2008/April/12. DOI: ken040 [pii] 10.1093/rheumatology/ken040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for patients with chronic neck pain. Pain 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diener HC, Kronfeld K, Boewing G, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berman BM, Lao L, Langenberg P, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141: 901–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 145: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster NE, Thomas E, Barlas P, et al. Acupuncture as an adjunct to exercise based physiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. Bmj 2007; 335: 436. 2007/August/19. DOI: bmj.39280.509803.BE [pii] 10.1136/bmj.39280.509803.BE [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1892–1898. 2007/September/26. DOI: 167/17/1892 [pii] 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A, et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006: CD002285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, et al. Lessons from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient expectations and treatment effects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001; 26: 1418–1424. 2001/July/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain 2007; 128: 264–271. 2007/January/30. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster NE, Thomas E, Hill JC, et al. The relationship between patient and practitioner expectations and preferences and clinical outcomes in a trial of exercise and acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis. European journal of pain (London, England) 2010; 14: 402–409. 2009/August/12. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Ichikawa L, et al. Treatment expectations and preferences as predictors of outcome of acupuncture for chronic back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: 1471–1477. 2010/June/11. DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c2a8d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prady SL, Burch J, Crouch S, et al. Insufficient evidence to determine the impact of patient preferences on clinical outcomes in acupuncture trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66: 308–318. 2013/January/26. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Ratcliffe J, et al. Longer term clinical and economic benefits of offering acupuncture care to patients with chronic low back pain. Health Technol Assess 2005; 9: iii-iv, ix-x, 1–109. 2005/August/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Ichikawa L, et al. Characteristics of patients with chronic back pain who benefit from acupuncture. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009; 10: 114. 2009/September/24. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witt CM, Schutzler L, Ludtke R, et al. Patient characteristics and variation in treatment outcomes: which patients benefit most from acupuncture for chronic pain? Clin J Pain 2011; 27: 550–555. 2011/February/15. DOI: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31820dfbf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witt CM, Vertosick EA, Foster NE, et al. The effect of patient characteristics on acupuncture treatment outcomes: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of 20,827 Chronic Pain Patients in Randomized Controlled Trials. The Clinical Journal of Pain in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim YK, Park JY, Kim SN, et al. What intrinsic factors influence responsiveness to acupuncture in pain?: a review of pre-clinical studies that used responder analysis. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2017; 17: 281. 2017/May/27. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-017-1792-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.