Abstract

Sequence blocks within the core region were swapped among RNA polymerase II promoters to explore effects on transcription in vitro. The pair of blocks flanking TATA strongly influenced general transcription, with an additional effect on promoter activation. These flanking elements induced a change in the ratio of activated to basal transcription, whereas swapping TATA and initiator sequences only altered general transcription levels. Swapping the flanking blocks influenced binding by general transcription factors TBP and TFIIB. The results suggest that the architecture of the extended core sequence is important in determining promoter-specific effects on both general transcription levels and the tightness of regulation.

Accurate initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase II (pol II) requires the formation of a large, multiprotein complex at the gene promoter (reviewed in references 11, 26, and 29). A typical core promoter is approximately 60 bp long and extends to just downstream of the transcription start site. Recognition elements include the TATA box element located 25 to 30 bp upstream of the start site and an initiator (Inr) element spanning the start site (reviewed in references 11 and 33). These two elements, either singly or in combination, are thought to be sufficient to drive basal levels of transcription (11, 19, 33, 34). Sometimes a downstream promoter element exists just beyond the core (2). Virtually all cellular promoters are thought to be associated with binding sites for activator proteins. These activators can be constitutive or inducible and typically bind upstream to help recruit the transcription machinery to the core promoter elements (27, 35). The core promoter region contains the interaction sites for several of the general transcription factors (11, 33). A weak, sequence-specific TFIIB binding site exists immediately upstream of the TATA box element (21). Other factors collectively contact nearly the entire extent of the core promoter sequences (5, 20, 22, 23, 28). With the possible exception of the upstream TFIIB site, which may influence basal transcription levels, these non-TATA and non-Inr sequences have not been implicated in control of transcription. The sequences between the TATA box and transcription start site are thought only to provide appropriate spacing (11).

Although activation determinants have recently been found within Inr (3), the specificity of activation has been largely associated with distal regions. That is, removal of activation sites leads to core promoters that function in basal transcription with RNA levels depending on the “strength” of TATA and/or Inr (11, 27, 35).

Nonetheless, prior studies are consistent with a role of the core sequences in setting the quantitative response to activators. This is suggested most prominently by comparing properties of the two prototype adenovirus promoters, the major late (ML) and the E4. Both in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that ML is the stronger basal promoter while E4 is more responsive to activators (7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15–17, 37). One possibility is that this is a simple consequence of activators compensating for the low basal transcription specified by the “weaker” E4 TATA and Inr sequences. Both promoters resemble the consensus TATA and Inr elements, with ML displaying a superior match to the consensus. Inspection of the core sequences (see Fig. 1) shows that the two promoters are by far the most different outside the TATAAAA and pyrimidine-rich Inr elements. Remarkably, only 5 of 39 positions have an identical base pair in these other promoter regions. The nucleotides of the ML promoter closely resemble sequences that appear most often in promoters collected in the EPD database (see Fig. 1, majority). The influence of these similarities and differences is not known.

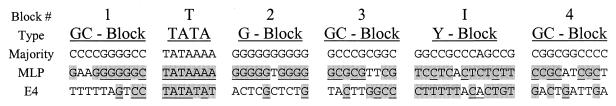

FIG. 1.

The majority sequence and promoter blocks. The majority sequence is shown divided into blocks according to base composition. The adenovirus type 2 ML and E4 promoters are aligned to these blocks by their TATA boxes. Bases in ML and E4 which match the composition (type) of the majority promoter are shaded. Bases which match the majority sequence by position are further underlined.

In this report, we explore the influence of the entire core promoter on the level of basal transcription and on the response to activation. The approach involves swapping sequence blocks between the ML and E4 promoters and between these and several promoters of human origin. Transcription studies are then used to define the influence of individual blocks of sequences on both basal and activated transcription. The results indicate that the nature of the sequence blocks surrounding the TATA element has a very significant effect on how responsive a promoter is to activation. This leads to the view that one must consider the architecture of the core promoter as a whole in understanding how promoters are designed to produce appropriate levels of RNA before and after induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Promoter alignments.

Promoter sequences were obtained from the Eukaryotic Promoter Database (http://www.epd.isb-sib.ch/seq_download.html). A “representative set of not closely related sequences” was requested. The 180 human promoters in this set were loaded into MegAlign (DNAStar, Inc.). TATA-less promoters were eliminated, and the remaining 122 promoters were manually aligned by their TATA boxes. “Consensi” were defined per instructions.

Nucleic acids, cloning, and proteins.

Promoters were cloned as described previously (37). Oligonucleotides (Operon) were made such that they were complementary at their 3′ ends. They were annealed and the ends were filled with Klenow enzyme. The ends were trimmed with EcoRI and BamHI and then ligated into a pSP72 vector (Promega) that had two Gal4 binding sites cloned into the BglII site. Ligation mixtures were transformed into strain DH5α, and the DNA sequences were verified. TBP (40) and TFIIB (14) were purified as previously described. Gal-AH and Gal-VP16 were kind gifts of Michael Carey (University of California, Los Angeles). All promoters were in an identical sequence context outside of the nucleotides indicated in the figures.

Human promoter sequences were obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Accession numbers are as follows: thymidine kinase (TK), M13643 (31); lymphotoxin (tumor necrosis factor beta [TNF-β]), X02911 (25); immunoglobin H (IgH), L07386 (36); dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), K01612 and M10235 (4); and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), S70315 (1). The α1 subunit of the Na/K-ATPase promoter is not on deposit. The sequence was obtained from Kawakami et al. (18).

In vitro transcription.

In vitro transcription was performed as previously described (37). Generally, 100 ng of supercoiled plasmid was mixed with 20 μl of HeLa nuclear extract (6 mg of protein/ml [see reference 6], 8 mM MgCl2, 500 ng of pGEM as carrier, and a 500 mM concentration of each nucleoside triphosphate [NTP]) in a total of 40 μl. Reactions were performed for 30 min at 30°C. A 100-μl volume of stop buffer (10 mM EDTA, 0.3 M sodium acetate [pH 5.5], 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 μg of yeast tRNA/ml, 20 μg of proteinase K) was added followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. RNA was isolated and copied by using reverse transcriptase (Promega) extension of 5′-32P-labeled Inr primer (37). The labeled cDNA products were resolved on urea–6% polyacrylamide gels (19:1 ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide, 8 M urea) and visualized and quantitated by using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Gal-AH was included where indicated.

For single-round assays (37, 39), the above protocol was modified as follows: only 25 ng of plasmid was used, NTPs were omitted in the first step, and preinitiation complexes were formed on the DNA for 45 min. NTPs were then added at a final concentration of 500 mM each. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 2 min. Human promoters were transcribed as follows: single-round assays were performed as described above by using 500 ng of supercoiled template. The activator Gal-VP16 was included where indicated.

Band shifts.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed essentially as previously described (40). Probes were made from supercoiled plasmids by PCR amplification using Inr (37) and T7 promoter (Promega) primers. Deep Vent (NEB) polymerase was used to generate blunt ends. The PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels, purified by using Qiagen columns, and end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and [γ-32P]ATP (NEN). A 0.5-fmol amount of labeled probe was mixed with 2 ng of TBP, 8 ng of TFIIB, 12 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 12% glycerol, 60 mM KCl, 0.12 mM EDTA, 0.6 mM dithiothreitol, 8 mM MgCl2, 5 μg of poly(dG:dC) (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml, and 50 μg of bovine serum albumin (Sigma) per ml. Mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min and resolved on 5% polyacrylamide (59:1 ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide)–2 mM MgCl2–0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gels (30). Gels were run at 400 V for approximately 30 min in Bio-Rad Mini-Protean II tanks by using prechilled running buffer (0.5× TBE, 2 mM MgCl2) submerged in ice. The inner tank was checked every 10 to 15 min, and the buffer was changed upon reaching 30°C. The gels were dried and exposed to PhosphorImager plates (Molecular Dynamics). The unbound DNA runs off the bottom of these gels. For quantitation, 10% of the amount of probe used in binding reactions was run on a parallel gel. These probes are unbound and run only halfway though the gel.

RESULTS

Promoter alignments and swaps.

Alignment of 122 TATA-containing promoters was done as described in Materials and Methods. The only positions at which a strong consensus emerged was the TATAAAA sequence, which was retained with 75 to 95% conservation in every position except the final A (41% conserved). Outside of this consensus, no nucleotide was conserved at even the 40% level. Each non-TATA position was identified with a majority base that appeared most often, typically only with very weak 30 to 35% conservation. Figure 1 shows that the non-TATA majority sequence consists of 51 GC pairs and a single AT pair within the start site region. The analysis shows that the majority promoter architecture consists of a GC-rich background interrupted by two AT-rich elements: the heptanucleotide TATA box and a single base pair near the start site.

We divided the promoter into blocks based on inspection of the majority sequence. Blocks 1 and 2 were taken as 10-bp sequences, i.e., one full turn of the helix, on either side of the TATA box. The remaining blocks were taken as downstream segments of 9 to 13 bp. Block 2 is distinctive, as it consists entirely of G's on the nontemplate strand of the majority. The Inr block was designed to be slightly longer to accommodate the swapping of the entire pyrimidine-rich nontemplate strand surrounding the ML promoter initiator. Blocks 3 and 4 are not clearly distinctive except that they consist entirely of GC pairs in the majority promoter.

The adenovirus ML and E4 promoters were aligned to these blocks (Fig. 1). These two promoters are quite different in their agreement with the sequences of the majority blocks. The ML promoter agrees very closely in composition with the majority sequence in all blocks. It has 22 of 29 GC pairs in blocks 1, 3, and 4; 9 of the 10 G's in block 2; all 12 pyrimidines in the Inr block; and a perfect match to the TATA region. The E4 promoter matches well only in the TATA and Inr blocks, with only 12 of 29 base pairs being GC in blocks 1, 3, and 4 and only 2 of 10 nucleotides being G in block 2. The figure shows the block segments that were swapped in the experiments described below.

E4 TATA and Inr elements influence general transcription but not response to activator.

In order to determine the roles these sequences may play in transcription, a series of “block-swapped” promoters was constructed. We started with the wild-type ML promoter and systematically substituted the corresponding E4 sequences block by block. This series of promoters was inserted into a vector containing two Gal4 sites upstream of the cloning site and subjected to standard in vitro transcription assays (6, 9, 12, 37–40).

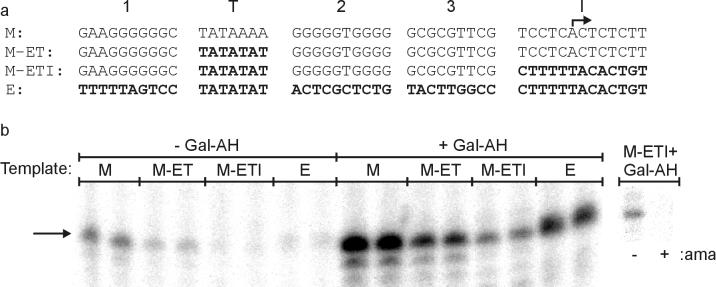

We began by swapping the E4 TATA and Inr block sequences into the ML promoter both singly and in combination (Fig. 2A). These elements are usually thought to determine the level of basal transcription and would be expected to make the ML promoter weaker. We are interested in confirming this and in learning whether the elements are also associated with the known greater response of the E4 promoter to activators (see also Table 1).

FIG. 2.

TATA and Inr control total transcription. (a) The promoters used in this experiment are shown. ML sequences are in normal type and E4 sequences are in bold. The transcription start site is indicated by an arrow. (b) In vitro transcription was performed with 100 ng of supercoiled plasmid containing the indicated promoter sequence. The activator Gal-AH was present where indicated. The primary transcript is indicated with an arrow. 5′-end analyses (not shown) confirm that these transcripts initiate at the +1 adenosine, as indicated in panel a. Lanes M-ETI+Gal-AH, activated transcription from 100 ng of M-ETI with (+) and without (−) α-amanitin (1 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Effects of TATA and block I swaps on ML transcriptiona

| Template | Relative level of transcription

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Activated | Ratio of activated to basal | |

| M | 1 | 5.6 | 5.6 ± 1.0 |

| M-ET | 0.3 | 1.7 | 6.4 ± 1.1 |

| M-ETI | 0.14 | 0.7 | 4.7 ± 1.8 |

| E | 0.18 | 2.3 | 14.7 ± 3.4 |

Values for basal and activated transcription are normalized to wild-type ML basal level. Data are averages of four trials and are rounded. Standard deviations (not all shown) are less than 40% of the average.

These promoters were transcribed in both the presence and the absence of the activator Gal-AH as shown in Fig. 2b. Each of the four promoters was transcribed in duplicate, and the bands were quantified with ImageQuaNT software (Molecular Dynamics). For weaker basal signals, the bands were more easily identified by using higher contrast settings. The values obtained for both basal and activated data were corrected for background and averaged over several trials (Table 1). Alpha-amanitin controls (example in Fig. 2b, right) showed transcription to be at least 98% pol II specific. Transcription was normalized to basal levels of the parent ML promoter.

Swapping the TATA box alone or in conjunction with the Inr block led to a reduction in both basal and activated transcription (compare M with M-ET and with M-ETI in Table 1; see below for a similar effect of the M-EI initiator swap). The reductions were approximately 2.5- to 5-fold. However, these reductions were equivalent in basal and activated transcription, leading to no change in the activation ratio of approximately 5.

The data show that for these promoters the TATA and Inr blocks influence the basal transcription level but not the response to activators. Substitution of the E4 TATA and Inr into ML weakens the promoter in general. The basal level of transcription from M-ETI is nearly identical to E4 (Table 1), yet the E4 promoter has a much greater response to activator: E4 is stimulated 15-fold while ML and M-ETI are stimulated only 5-fold (Table 1). We infer that this enhanced response to activator in the E4 promoter requires core sequences outside of the identical TATA and Inr sequences in the E4 and M-ETI promoters. These other blocks were tested individually, as described below.

E4 blocks flanking TATA influence both general transcription and the tightness of regulation.

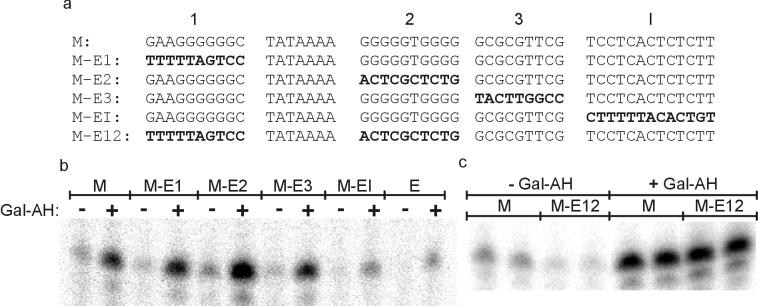

Non-TATA E4 blocks 1, 2, 3, and I were swapped individually into the ML promoter (Fig. 3a). Both basal and activated transcription were assayed (Fig. 3b). Each swap produces a distinctive effect, with the most obvious ones associated with swapping the I block and block 2. I-block substitution strongly reduces both basal and activated transcription, which is reasonable as it contains the initiator sequence (compare M-EI with M). The most interesting of the non-TATA non-Inr swaps was due to E4 block 2. Its substitution for the ML block 2 sequence strongly increases activated transcription (compare M-E2 with M). This increase is attained without any significant change in the level of basal transcription (see Table 2 for the average of several experiments). We infer that the sequences within E4 block 2 can selectively mediate enhanced levels of activated transcription.

FIG. 3.

E4 sequences alter the transcription properties of the ML promoter. (a) The promoters used in these experiments are shown as in Fig. 2a. (b and c) Representative transcription gels using the E4-swapped ML promoters. Transcription was performed as in Fig. 2. Gal-AH was included as indicated (+).

TABLE 2.

Effects of E4 swaps on ML transcriptiona

| Template | Relative level of transcription

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Gal-AH | Gal-AH-to-basal ratio | CREB | CREB-to-basal ratio | |

| M | 1 | 5.5 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 5.4 | 5.4 ± 0.2 |

| M-E1 | 0.6 | 6.5 | 10.9 ± 2.4 | 8.4 | 12.6 ± 2.4 |

| M-E2 | 1.0 | 10.4 | 9.8 ± 1.8 | 9.8 | 9.3 ± 2.3 |

| M-E3 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 16.4 ± 4.0 | ||

| M-EI | 0.2 | 1.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | ||

| M-E12 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 12.0 ± 1.6 | ||

| E | 0.15 | 2.3 | 14.9 ± 2.2 | ||

Each value shown is the average of at least two trials. Values for basal and activated transcription are normalized to the wild-type ML basal level and are rounded. Values for basal transcription include all data from Gal-AH and CREB experiments. Standard deviations (not all shown) are less than 30% of the average except for M-E3 basal (50%).

The quantitative analysis of these data is presented in Table 2. Each of the block substitutions has some effect on transcription, either basal, activated, or both. Taken together with the data of Table 1, a common pattern can be seen that distinguishes blocks 1, 2, and 3 from the TATA and Inr blocks. Substitution of the E4 TATA or Inr blocks led to comparable reductions in basal and activated transcription, leaving the activation ratio unchanged (compare M with M-EI in Table 2 or with M-ET in Table 1). In contrast, substitution of E4 blocks 1, 2, and 3 always leads to an increase in activation ratio (compare M with M-E1, M-E2, and M-E3 in Table 2). Similar effects were seen whether continuous transcription or single-round assays were used (data not shown). These effects were consistently strongest with substitution of blocks 1 and 2. They were not specific to the activator used as comparable increases in activation ratio were seen with CREB-mediated activation (Table 2). We constructed a double substitution involving these E4 blocks and assayed for basal and activated transcription (Fig. 3c). This promoter has an activation ratio that approached, but did not quite reach, that of the parent E4 promoter (compare M-E12 with E). We infer that blocks 1 and 2 of the E4 promoter have a very strong influence on the promoter activation ratio. This result is in strong contrast to that obtained with the double substitution of the TATA and Inr blocks (Table 1). In that case (M-ETI), both basal and activated transcription were reduced drastically, leading to no change in the tightness of regulation as judged by an unchanged activation ratio. It appears that one pair of blocks, TATA and Inr, functions to direct general transcription levels, whereas the other pair, blocks 1 and 2, can function to direct the tightness of regulation.

The flanking ML blocks also influence transcription regulation.

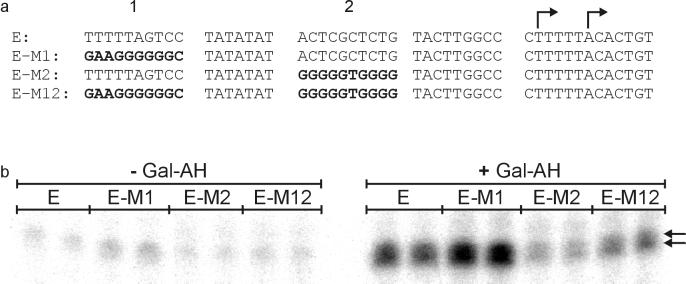

The data have shown that replacing blocks 1 and 2 of the adenovirus ML promoter with corresponding sequences from the adenovirus E4 promoter can alter the tightness of regulation. Next, the reciprocal swaps of these ML blocks into the E4 promoter were investigated. These blocks are shown in Fig. 4a, with their transcription shown in Fig. 4b. They include both the single and double swaps.

FIG. 4.

ML sequences alter the properties of the E4 promoter. (a) The promoters used in these experiments are shown as in Fig. 2a and 3a, except that E4 sequences are in normal face and ML sequences are in boldface. The expected E4 transcription start sites are indicated by arrows. (b) A representative transcription gel. The major transcripts are indicated by arrows. 5′-end mapping confirms that these transcripts initiated at the expected sites (not shown).

The results are consistent with expectations. The double swap of ML sequences reduces the E4 activation ratio from 11 to 3 (Table 3) and increases basal transcription. This activation ratio is comparable to that exhibited by the parental ML promoter (5.5-fold). Each individual block swap also reduces the ratio, although to a lesser extent than the double swap. Thus, ML blocks 1 and 2 are associated with a low activation ratio whether in the context of the E4 or ML promoter. As shown above, this is analogous to the E4 promoter blocks but with the expected opposite effect; E4 blocks are associated with high activation ratios whether in the context of the E4 or ML promoter. It appears that these two sequence blocks play a critical role in setting the activation ratio, independent of ML or E4 context.

TABLE 3.

Effects of ML swaps on E4 transcriptiona

| Template | Relative level of transcription

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Activated | Ratio of activated to basal | |

| E | 1 | 10.9 | 10.9 ± 1.7 |

| E-M1 | 1.9 | 16.0 | 8.3 ± 0.6 |

| E-M2 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 3.5 ± 1.3 |

| E-M12 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

Values shown are averages of two trials each. Transcription values are normalized to the wild-type E4 basal level and are rounded. Standard deviations (not all shown) are less than 35% of the average.

Response of human promoters to block 1 and 2 swaps.

We wished to learn if these block 1 and 2 sequences could affect a wide variety of promoters. Few promoters have been tested systematically in vitro, and their sensitivity to activation is rarely known. Six human promoters were chosen based on their being widely studied in the literature. The set represents a wide diversity of sequences throughout the promoter region (Fig. 5). Four contain clear TATA elements with matches to the consensus ranging from four of seven for α1 to six of seven for TNF-β. Two promoters usually considered to be TATA-less (DHFR and TdT) were included (32, 33).

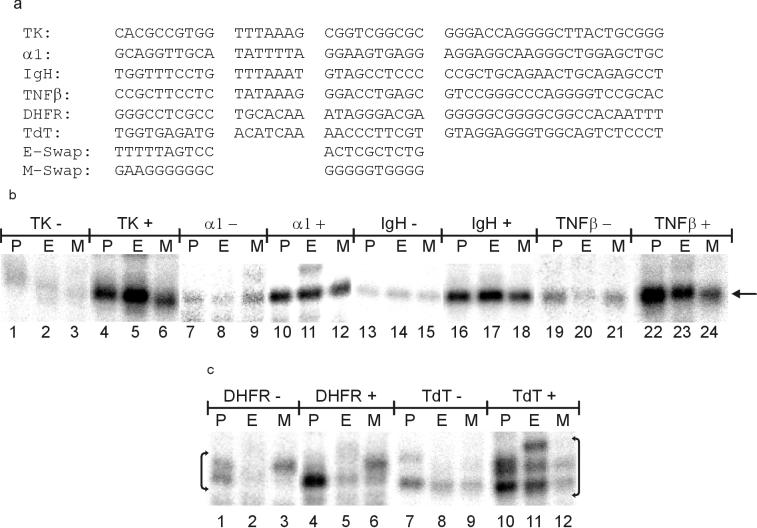

FIG. 5.

Block swaps affect many promoters. (a) The set of six human promoters used are shown divided into blocks. E-swap and M-swap illustrate which blocks were substituted in each promoter. (b) Examples of transcription from TATA-containing promoters. P, parent promoter; E, E-swapped promoter; M, M-swapped promoter. The parent of each set is indicated: −, no Gal-VP16; +, Gal-VP16 added. The single transcript from each promoter is indicated by an arrow and corresponds to a start site predicted from ML transcription. (c) Transcription from TATA-less promoters. The multiple start sites indicated are clustered around the site predicted from ML transcription.

Each of the six core promoter regions was cloned into the same vector used above. Each promoter was also constructed in two swapped versions. In one set, E4 blocks 1 and 2 replaced the two equivalent wild-type blocks, and in another set, the two ML blocks were substituted (Fig. 5a). This yields a set of 18 promoters: six parents and two double swaps of each. Because in vitro transcription of these promoters had not always been optimized previously, conditions were altered slightly from those described above (see Materials and Methods).

Figure 5 shows transcription from the TATA-containing promoters (Fig. 5b) and the TATA-less promoters (Fig. 5c). The TATA-containing promoters (parents shown in lanes P) all initiated predominantly at a single site and yielded transcripts of the expected length (Fig. 5b). The TATA-less promoters (Fig. 5c) initiated at several sites clustered around the predicted start site. We observe that in the context of the TATA-less promoters, the swaps can alter the start site preference (Fig. 5c, compare lane 1 to lane 3 and lane 10 to lane 11). The source of this phenomenon is not clear, and so all the bands indicated in Fig. 5c were collectively quantified.

Inspection of the autoradiographs shows two consistent effects of the block 1 and 2 swaps. First, at all six promoters, replacement of the wild-type blocks with the ML blocks reduced the amount of activated transcription (lanes M versus P in each of the six activated comparisons). Second, in five of six cases (IgH was the exception), the E4 swaps decreased the amount of basal transcription (lanes E versus P in each of the six unactivated comparisons). We infer that blocks 1 and 2 can influence the level of transcription in a wide variety of contexts.

These substitutions also had the effect on the activation ratio predicted from the experiments with the adenovirus parents (Table 4). The ML double swap reduced the activation ratio of all six human promoters, reflecting the low activation ratio of the ML parent. The E4 double swap increased the activation ratio in five of six cases (again, the exception was IgH), reflecting the high activation ratio of the E4 parent. These are the same effects seen in the adenovirus contexts, demonstrating that blocks 1 and 2 can influence the tightness of regulation in the context of a wide variety of promoters.

TABLE 4.

Effects of E4 and ML swaps on transcription from human promotersa

| Promoter | Relative level of transcription

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal

|

Activated

|

Ratio of activated to basalb

|

|||||||

| Parent | E swap | M swap | Parent | E swap | M swap | Parent | E swap | M swap | |

| TK | 1 | 0.6 (−) | 0.6 (−) | 4.9 | 6.9 (+) | 2.3 (−) | 4.9 | 11.7 (+) | 3.9 (−) |

| α1c | 1 | 0.6 (−) | 1.6 (+) | 10.2 | 8.8 (−) | 8.9 (−) | 10.2 | 16.4 (+) | 5.2 (−) |

| IgH | 1 | 1.5 (+) | 1.5 (+) | 9.7 | 13.9 (+) | 5.6 (−) | 9.7 | 9.4 | 3.8 (−) |

| TNF-β | 1 | 0.3 (−) | 1.0 | 8.8 | 3.9 (−) | 2.7 (−) | 8.8 | 12.8 (+) | 3.0 (−) |

| DHFR | 1 | 0.1 (−) | 0.9 | 5.7 | 2.0 (−) | 2.1 (−) | 5.7 | 24.1 (+) | 2.2 (−) |

| TdT | 1 | 0.5 (−) | 0.6 (−) | 3.6 | 3.4 | 1.2 (−) | 3.6 | 7.5 (+) | 2.0 (−) |

Each value is the average of two to four trials. Transcription data for each promoter are normalized to the wild-type basal level for that promoter. Significant changes from the parental values are indicated by (+) and (−).

Shown are the averages of the ratios obtained in each individual experiment.

α1, α1 subunit of the Na/K-ATPase promoter.

Altered factor assembly levels by sequence blocks flanking TATA.

In these human promoters, the E4 block 1 and 2 substitutions have reasonably consistent effects on basal transcription and on the activation ratio. The source of the effect on the activation ratio could be quite complex, as the interactions between perhaps dozens of polypeptides need to be considered. However, basal transcription may rely on a more simple set of interactions, perhaps primarily on the association of TBP and TFIIB with the DNA. Thus, we explored whether the substitutions alter the assembly of these components by using an EMSA.

In this experiment, the ML promoter was used as the parent. Substitution of E4 blocks 1 and 2 yields a 2.5-fold reduction in basal transcription (see above; Table 2). The EMSA results (Fig. 6 and Table 5) show that assembly of the TBP-TFIIB-DNA complex is also reduced 2.5-fold by this substitution. The source of this reduction is a lessening of binding by TBP alone, which accounts for most or all of the effect. We infer that blocks 1 and 2 can influence TBP binding strongly and that this is a likely influence on basal transcription levels.

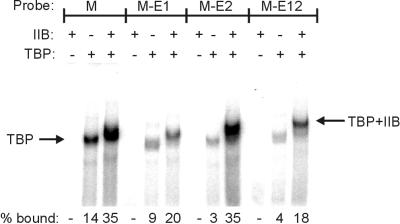

FIG. 6.

Gel mobility shift assay: representative gel shift result. The presence (+) or absence (−) of TBP and TFIIB is indicated. Retarded complexes are indicated by arrows. The unbound DNA ran off the bottom of the gel. The numbers below the figure indicate the percentage of total probe that is present in the bound complexes (see Materials and Methods).

TABLE 5.

Results of gel mobility shift assays

| Probe | Relative level

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TBP | TBP-TFIIB | TXNa | |

| M | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| M-E1 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.60 |

| M-E2 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| M-E12 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

TXN, basal transcription (see Table 2).

We also tested the ability of each block individually to influence assembly. The data show that either E4 block 1 or 2 acting alone reduces TBP binding. In the case of the block 1 substitution, this reduction is not cured by adding TFIIB, as the TBP-TFIIB-DNA complex level is comparably reduced. In the case of the block 2 substitution, addition of TFIIB can restore TBP-TFIIB-DNA complex formation to wild-type levels. This is probably explained by the tighter TFIIB binding ability of the parent block 1 sequences that are retained only in this construct.

Overall, there is an excellent correlation between levels of basal transcription and levels of TBP-TFIIB-DNA complex formation. The surprising aspect is that an important contribution to this is made by controlling TBP binding. Thus, the data indicate that the sequences flanking the TATA box can have a strong influence on TBP binding, which appears to carry through to transcription in the appropriate context.

DISCUSSION

In addition to providing core recognition sites for assembly of transcription complexes, promoters need to include signals specifying the responsiveness to activators and the level of mRNA. In general, the activation signals lie in distal regions, typically upstream (11, 27, 35). The downstream core contains signals that contribute to promoter strength. These include the well-known TATA and initiator (Inr) elements. The TATA and Inr elements make this contribution via recruitment of preinitiation complexes (11, 24, 37), with the TATA box playing an additional role in specifying the rate of continuous transcription (39, 40). In this paper, we find that sequences flanking the TATA element are important for promoter strength, for TBP binding, and for mediating the response to upstream activators. The last result is particularly unexpected and contributes to a model in which the architecture of the promoter as a whole determines both the responsiveness to activators and the strength of the transcription.

The origin of the work lies in the differential responsiveness of the adenovirus ML and E4 promoters to activation (7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15–17, 37). The former has high unactivated, basal transcription, whereas the latter is more responsive to activation. By swapping sequences between these two promoters, we were able to identify core promoter regions that contributed to these properties. The swaps showed that the sequence blocks flanking TATA played a role distinct from that of the TATA and Inr blocks; only the flanking blocks contributed to the responsiveness to activation. That is, substitution of E4 sequences into ML increased its activator responsiveness, whereas substitution of ML sequences into E4 had the opposite effect. Increases in responsiveness were not solely due to reductions in basal transcription, implying a more complex role for these blocks that flank the TATA element. Moreover, swapping the TATA and Inr blocks between the promoters altered general transcription levels without having significant effects on activator responsiveness.

It is important to note that these TATA and Inr swaps are very conservative. In particular, both the ML Inr and E4 Inr match the degenerate consensus perfectly (YYAN[T/A]YY, where Y is a pyrimidine and the underlined A is the transcription start site; see reference 33). However, another study has shown that more dramatic changes in the Inr can affect the activation ratio (3). Thus, we cannot conclude that TATA and Inr play no role in activator responsiveness. In the context of these adenovirus promoters, however, the conservative differences in these elements do not alter activator responsiveness.

In order to assess the general significance of these observations, we first compared the sequences of these blocks to those in the Eukaryotic Promoter Database. Alignment of 122 TATA-containing promoters produced no consensus outside of TATA but did reveal an unusual property of the core promoter region. With the exception of a single nucleotide near the start site, all non-TATA positions were most often GC base pairs (Fig. 1). That is, this majority promoter consists of an AT-rich TATA box embedded in a sea of GC base pairs. This majority promoter resembles the ML promoter in this regard and is antithetical to the E4 promoter, which is unusual in being largely AT-rich.

Although promoters tend to be GC-rich, they exhibit considerable diversity. We chose a series of six human promoters and substituted either the GC-rich ML blocks or the AT-rich E4 blocks to see the effects on transcription (Fig. 5). Transplanting the GC-rich ML sequences into human promoters had the general effect of decreasing the responsiveness of the promoter to activation; including the E-M12 swap, this effect occurred in seven out of seven cases (Tables 3 and 4). This decrease in responsiveness was not due to increased basal strength, as such an increase occurred in only three of the seven promoter swaps. Remarkably, the level of activated transcription decreased in all seven cases.

As expected, the transplantation of the AT-rich E4 flanking blocks into human promoters increases the activation ratio, occurring in five of the six promoters (and six of seven when the ML parent promoter is included [Tables 2 and 4]). This increase in responsiveness correlates with a decrease in the level of basal transcription in six out of seven cases. The single exception is the IgH promoter, for which basal transcription does not decrease and responsiveness does not increase. This indicates that the E4 sequences do not universally induce tight regulation. Whether consensus sequences exist or depend strongly on promoter context remains to be seen. However, these data show that the two blocks flanking TATA play a dominant role in regulating the tightness of control. In 13 out of 14 cases, activator responsiveness correlates directly with the types of sequences present in these blocks.

We note that these effects are consistent with the physiological roles of the ML and E4 promoters during the adenovirus life cycle (7, 8). The ML promoter is primarily activated by an increase in genome copy number. Thus, it is designed to be a strong basal promoter, weakly responsive to activators. In contrast, the E4 promoter is turned on in response to protein activators when the copy number is low. The above data suggest that the sequences of the blocks flanking TATA contribute to these characteristics in a very important manner. We expect that the diversity of sequences within these blocks of human promoters will also contribute to the physiological design of the promoters in terms of responsiveness to regulators.

There remains the question of how these sequence blocks function. We consider this question from the point of view of substituting the two AT-rich E4 blocks, which have a poor resemblance to the majority promoter. This substitution consistently decreases the level of basal transcription, regardless of promoter context. The data show that these substitutions reduce the level of TBP binding (Fig. 6 and Table 5). Thus, the sequences surrounding TATA contribute both to TATA recognition and to basal transcription levels. TATA recognition is optimal when the element is made most distinctive by surrounding it with GC-rich sequences and suboptimal when the surrounding regions are AT-rich. The typical promoter is diverse but more like the GC-rich ML sequence, implying that it is important to generally have a distinctive TATA sequence and the capacity to direct some basal transcription. The band shift experiments support the idea that the block upstream from TATA may contribute to basal transcription (Table 5) through interaction of a GC-rich sequence with TFIIB (21).

The data do not indicate the source of the effects on activated transcription. They simply suggest that the core promoter becomes more responsive as the sequence diverges from the majority sequence. Activation is a very complex process involving the interplay of a large number of proteins, both activators and general transcription factors (see the introduction). The activated transcription complex assembles over the blocks that flank TATA so the blocks are in a position to influence assembly, but in a manner as yet unknown. The challenge is to understand how the diverse sequences within the promoter core interact to create an architecture that is appropriate to the unique physiological function of each promoter.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by USPHS grant GM49048 (J.D.G.) and USPHS National Research Service Award GM07185 (B.S.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhaumik D, Yang B, Trangas T, Bartlett J S, Coleman M S, Sorscher D H. Identification of a tripartite basal promoter which regulates human terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15861–15867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke T W, Willy P J, Kutach A K, Butler J E, Kadonaga J T. The DPE, a conserved downstream core promoter element that is functionally analogous to the TATA box. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:75–82. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalkley G E, Verrijzer C P. DNA binding site selection by RNA polymerase II TAFs: a TAF(II)250-TAF(II)150 complex recognizes the initiator. EMBO J. 1999;18:4835–4845. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M J, Shimada T, Moulton A D, Cline A, Humphries R K, Maizel J, Nienhuis A W. The functional human dihydrofolate reductase gene. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:3933–3943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulombe B, Li J, Greenblatt J. Topological localization of the human transcription factors IIA, IIB, TATA box-binding protein, and RNA polymerase II-associated protein 30 on a class II promoter. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19962–19967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fessler S P, Young C S. Control of adenovirus early gene expression during the late phase of infection. J Virol. 1998;72:4049–4056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4049-4056.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginsberg H S. The adenoviruses. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gralla J D. Global steps during initiation by RNA polymerase II. Methods Enzymol. 1996;273:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)73009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hai T W, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Green M R. Analysis of the role of the transcription factor ATF in the assembly of a functional preinitiation complex. Cell. 1988;54:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hampsey M. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcriptional machinery. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:465–503. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.465-503.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawley D K, Roeder R G. Functional steps in transcription initiation and reinitiation from the major late promoter in a HeLa nuclear extract. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3452–3461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoopes B C, LeBlanc J F, Hawley D K. Contributions of the TATA box sequence to rate-limiting steps in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:1015–1031. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hori R, Pyo S, Carey M. Protease footprinting reveals a surface on transcription factor TFIIB that serves as an interface for activators and coactivators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6047–6051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horikoshi M, Hai T, Lin Y S, Green M R, Roeder R G. Transcription factor ATF interacts with the TATA factor to facilitate establishment of a preinitiation complex. Cell. 1988;54:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Y, Yan M, Gralla J D. Abortive initiation and first bond formation at an activated adenovirus E4 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27332–27338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y, Yan M, Gralla J D. A three-step pathway of transcription initiation leading to promoter clearance at an activated RNA polymerase II promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1614–1621. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakami K, Masuda K, Nagano K, Ohkuma Y, Roeder R G. Characterization of the core promoter of the Na+/K(+)-ATPase alpha 1 subunit gene. Elements required for transcription by RNA polymerase II and RNA polymerase III in vitro. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0440k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Killeen M, Coulombe B, Greenblatt J. Recombinant TBP, transcription factor IIB, and RAP30 are sufficient for promoter recognition by mammalian RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9463–9466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim T K, Lagrange T, Wang Y H, Griffith J D, Reinberg D, Ebright R H. Trajectory of DNA in the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12268–12273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagrange T, Kapanidis A N, Tang H, Reinberg D, Ebright R H. New core promoter element in RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription: sequence-specific DNA binding by transcription factor IIB. Genes Dev. 1998;12:34–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagrange T, Kim T K, Orphanides G, Ebright Y W, Ebright R H, Reinberg D. High-resolution mapping of nucleoprotein complexes by site-specific protein-DNA photocrosslinking: organization of the human TBP-TFIIA-TFIIB-DNA quaternary complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10620–10625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Hahn S. Model for binding of transcription factor TFIIB to the TBP-DNA complex. Nature. 1995;376:609–612. doi: 10.1038/376609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maldonado E, Ha I, Cortes P, Weis L, Reinberg D. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: role of transcription factors IIA, IID, and IIB during formation of a transcription-competent complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6335–6347. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nedwin G E, Naylor S L, Sakaguchi A Y, Smith D, Jarrett-Nedwin J, Pennica D, Goeddel D V, Gray P W. Human lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor genes: structure, homology and chromosomal localization. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:6361–6373. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.17.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pugh B F. Mechanisms of transcription complex assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert F, Forget D, Li J, Greenblatt J, Coulombe B. Localization of subunits of transcription factors IIE and IIF immediately upstream of the transcriptional initiation site of the adenovirus major late promoter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8517–8520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauve G J, Lipson K E, Chen S T, Baserga R. Sequence analysis of the human thymidine kinase gene promoter: comparison with the human PCNA promoter. DNA Seq. 1990;1:13–23. doi: 10.3109/10425179009041343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slansky J E, Farnham P J. Transcriptional regulation of the dihydrofolate reductase gene. Bioessays. 1996;18:55–62. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smale S T. Transcription initiation from TATA-less promoters within eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1351:73–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smale S T, Baltimore D. The “initiator” as a transcription control element. Cell. 1989;57:103–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stargell L A, Struhl K. Mechanisms of transcriptional activation in vivo: two steps forward. Trends Genet. 1996;12:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun Z, Kitchingman G R. Analysis of the imperfect octamer-containing human immunoglobulin VH6 gene promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:850–860. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.5.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolner B S, Gralla J D. Promoter activation via a cyclic AMP response element in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32301–32307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yean D, Gralla J. Transcription activation by GC-boxes: evaluation of kinetic and equilibrium contributions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2723–2729. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.14.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yean D, Gralla J. Transcription reinitiation rate: a special role for the TATA box. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3809–3816. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yean D, Gralla J D. Transcription reinitiation rate: a potential role for TATA box stabilization of the TFIID:TFIIA:DNA complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:831–838. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]