Abstract

Introduction:

Restrictions to do with the COVID-19 pandemic have had substantial unintended consequences on Canadians’ alcohol consumption patterns, including increased emotional distress and its potential impact on alcohol use. This study examines 1)changes in adults’ alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia; 2) whether drinking more frequently during the pandemic is associated with increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness; and 3)whether gender moderatesthis relationship.

Methods:

Participants were drawn from a cross-sectional survey of 2000 adults. Adjusted multinomial regression models were used to assess the association between drinking frequency and increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness. Additional analyses were stratified by gender.

Results:

About 12% of respondents reported drinking more frequently after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and 25%–40% reported increased emotional distress. Increased feelings of stress (odds ratio [OR] = 1.99; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.35–2.93), loneliness (OR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.22–2.61) and hopelessness (OR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.21–3.23) were all associated with drinking more frequently during the pandemic. While women respondents reported higher rates of emotional distress, significant associations with increased drinking frequency were only observed among men in gender-stratified analyses.

Conclusion:

Individuals who report increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to report increased drinking frequency; however, these associations were only significant for men in stratified analyses. Understanding how the pandemic is associated with mental health and drinking may inform alcohol control policies and public health interventions to minimize alcohol-related harm.

Keywords: alcohol drinking, COVID-19 pandemic, emotions, gender, self-medication

Highlights

This study examines how alcohol use and emotional well-being changed among New Brunswick and Nova Scotia adults following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

Since the start of the pandemic, 12.2% of respondents consumed alcohol more frequently than before.

Between 25.3% and 43.5% of respondents reported increased stress, loneliness and hopelessness.

A greater proportion of women reported increased emotional distress since the start of the pandemic.

Significant associations between increased emotional distress and increased alcohol consumption during the pandemic were observed but only among men.

Introduction

The swift and drastic measures implemented to contain COVID-19 resulted in considerable change in Canadians’ daily lives. Widespread closures of schools, workplaces and businesses left many people unemployed. Parents and guardians took on the role of educators as schooling moved online, and access to much-needed health services was cut. These changes resulted in considerable uncertainty and emotional distress.

Emerging studies on the unintended consequences of the social and environmental restrictions imposed to control the spread of COVID-19 report elevated rates of depression, anxiety and stress in some populations, particularly women, younger people and individuals with pre-existing health conditions.1-4 These effects likely stem from the burden and loss of freedom imposed by the restrictions and reduced access to positive coping strategies typically used to manage stress, such as social support, extracurricular activities and even mental health services.5

Individuals may increasingly use alcohol as a coping mechanism during times of stress, seeking the relaxing pharmacological effects of alcohol. This self-medication hypothesis posits that individuals may engage in substance use when under emotional distress and be driven to increase positive affect and decrease negative affect.6 Research has shown that drinking to cope is associated with heavier alcohol use (i.e. greater volume intake) and poses the greatest risk for negative alcohol-related consequences in the short and the long term.7,8 Women are more likely than men to consume alcohol in response to negative emotions; they also have a higher prevalence of comorbid substance use and mental health disorders.7,9,10

Observed increases in post-disaster substance use may reflect a strategy of self-medication to cope with emotional distress.11 In a recent commentary, Rehm and colleagues,12 drawing on the literature from past public health crises,13 suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to a medium- to long-term increase in alcohol consumption, particularly among men. Research on past large-scale disasters has found a strong link between post-disaster emotional distress and increased substance use.5,13,14 Early research on the COVID-19 pandemic reports associations between overall poor mental health and increases in alcohol consumption.15 More generally, Canadians who reported having fair or poor mental health reported greater substance use, and stress was the third most common reason cited by those who increased their drinking (44%).16 Similar associations with increased alcohol use have been observed for overall poor mental health, increased depressive symptoms and lower mental well-being.15 A study from the United States noted that emotional distress related to COVID-19 was associated with increased drinking frequency and heavy drinking for both men and women.17

Alcohol is the most used substance among Canadians18 and the costliest in terms of harms to health.19 Since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, alcohol sales have increased in many jurisdictions.20,21 Recent surveillance surveys suggest that while between 14% and 18% of adult Canadians have increased the amount of alcohol they consume, a similar proportion (9%–12%) have decreased their consumption; for most Canadians (70%), their drinking has remained the same.16,22,23 Comparable patterns have been observed in the United States,24 the United Kingdom,15 Poland25 and Australia.26

Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic has potential long-term social and economic costs for individuals, communities and society.27-30 It has prompted a “need to closely monitor any change in alcohol use.”12,p.303 We need to strengthen our understanding of how, and for whom, specific COVID-19-related stressors are associated with alcohol consumption in order to inform alcohol control policies and public health interventions that can minimize alcohol-related harm. Moreover, because women are more likely than men to consume alcohol in response to negative emotions and have a higher prevalence of comorbid substance use and mental health disorders (as noted earlier),7,9,10 we need to understand gender differences in the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic to develop an appropriate pandemic-related response.31

In light of emerging evidence suggesting that alcohol consumption has increased during the pandemic, this study looks to examine whether changes in mental health and well-being, particularly emotional distress, brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic may be playing a role in changing consumption patterns. To date, research in this area has been sparse, with no population-based Canadian studies. Specifically, we aim to (1) identify changes in drinking patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic among adults in two Atlantic Canadian provinces; (2) examine whether there exists an association between drinking more frequently during the pandemic and increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness; and (3) assess whether gender moderates this relationship.

Methods

Data source

We took data for the present study from the 2020 Alcohol Consumption During COVID-19 (ACDC) Survey, an anonymous, cross-sectional survey of adults 19 years and older residing in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia administered on behalf of the research team by Leger, a Canadian market research company. Like most jurisdictions in Canada, both these provinces deemed alcohol sales an essential service. Alcohol was readily accessible at on-premises locations, as well as through avenues initiated or expanded during the pandemic (curbside pickup, delivery and on-demand) when the survey was run in November/December 2020.

Respondents were sampled in two phases to reach a quota of 1000 respondents in each province. In the first phase, approximately 500 respondents were randomly selected to be surveyed online from a panel of over 400 000, representing Canadians with Internet access, including hard-to-reach target groups.32 The second phase sampled 1500 respondents via telephone and targeted respondents in regions not captured or underrepresented in the online Leger Opinion survey. The sampling frame consisted of a mix of landline and mobile phone numbers provided by ASDE Survey Sampler, an accredited Canadian database-survey sample provider. All phone numbers were compared against the voluntary, market research national “do not call” list, and all matches were removed from the sample before randomization and selection procedures.

The sample was stratified to ensure that all regions of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were represented. Leger developed an Apple and Android application to reach people on their mobile devices and obtain a higher response rate. The response rate for the phone portion was 10% and for the online portion was 14%. Non-response comprised anything affecting survey completion, including phone numbers not in service, no answer, refusals and those who did not complete the survey. These rates align with other phone and online surveys.33-36

Ethics approval was obtained from the Dalhousie University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (REB # 2020-5258).

Measures

Outcome measure

The outcome of interest was the change in drinking frequency after the imposition of measures to contain COVID-19 in March 2020. Respondents were asked to describe their drinking frequency twice during the survey, drawing on a common survey measure of drinking frequency.37

The first assessment was based on responses to the question: “Before the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, how often did you use alcohol? (By alcohol, we mean a drink of beer, wine, liquor or any other alcoholic beverage.)” The second assessment was based on responses to the question: “Currently, how often do you use alcohol? (By alcohol, we mean a drink of beer, wine, liquor, or any other alcoholic beverage.)” Response options to both questions were as follows: “many times a day,” “once a day,” “4 to 5 times a week,” “2 to 3 times a week,” “once a week,” “2 to 3 times a month,” “once a month,” “less than once a month” and “never.”

From these two questions, a measure was constructed to capture changes in drinking patterns with four options: “non-drinker” (respondents who reported not drinking in both questions); “drinking less”; “drinking about the same”; and “drinking more.”

Emotional distress

The primary exposure variables in this study were three measures of emotional distress, namely increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We assessed increases based on responses to the following question: “Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March, have you been experiencing more or less of the following?” The frequency of the response options—“far less,” “slightly less,” “the same,” “slightly more” and “far more”—were recorded on a five-point Likert scale. Responses were dichotomized to capture experiencing more (slightly more, far more) than the same or less of each emotional state. Please note that our study does not examine diagnosable psychiatric or psychological disorders, but forms of emotional distress. While such responses are typically subclinical, it is still important to investigate their public health impact.38

Gender

We determined the respondents’ gender based on responses to the following question: “What is your gender identity?” Response options were “man,” “woman” and “non-binary.” Gender was used as a covariate in adjusted models and for stratification purposes. Given observed gender/sex differences in emotional and mental health and drinking behaviours,39 it is important to consider the potential for gender-specific associations between emotional distress and drinking frequency.

Three respondents identified as non-binary; while they were included in all analyses, we do not report their responses due to the small cell size.

Other covariates

The analyses included covariates known to be associated with drinking. Other than gender, the demographic covariates were ethnicity (collapsed to White, non-White); age (continuous); official language spoken (French, English); living alone (yes, no); completed a bachelor’s degree (yes, no); employment status (employed full/part-time, retired, unemployed/can’t work, other); and province of residence (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia).

We included a covariate assessing overall self-rated mental health to adjust for broad, longer-term mental health and well-being. Responses to the question “In general, how would you rate your emotional/mental health?” ranged from poor to excellent on a standard five-point Likert scale. This measure was dichotomized to capture poor/fair relative to good/very good/excellent mental health, as is commonly described in the literature.40

Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and estimated prevalence rates for the total sample. Separate unadjusted and adjusted multinomial regression models estimated changes in drinking frequency since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic as a function of increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness. All models were repeated, stratified by gender identity and adjusted for other covariates. All analyses used analytic weights to account for study design and participant non-response to reflect the gender, age and regional profiles of adults in the respective provinces. We assessed multicollinearity in our measures using variance inflation factors (VIF); results were within normal ranges. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

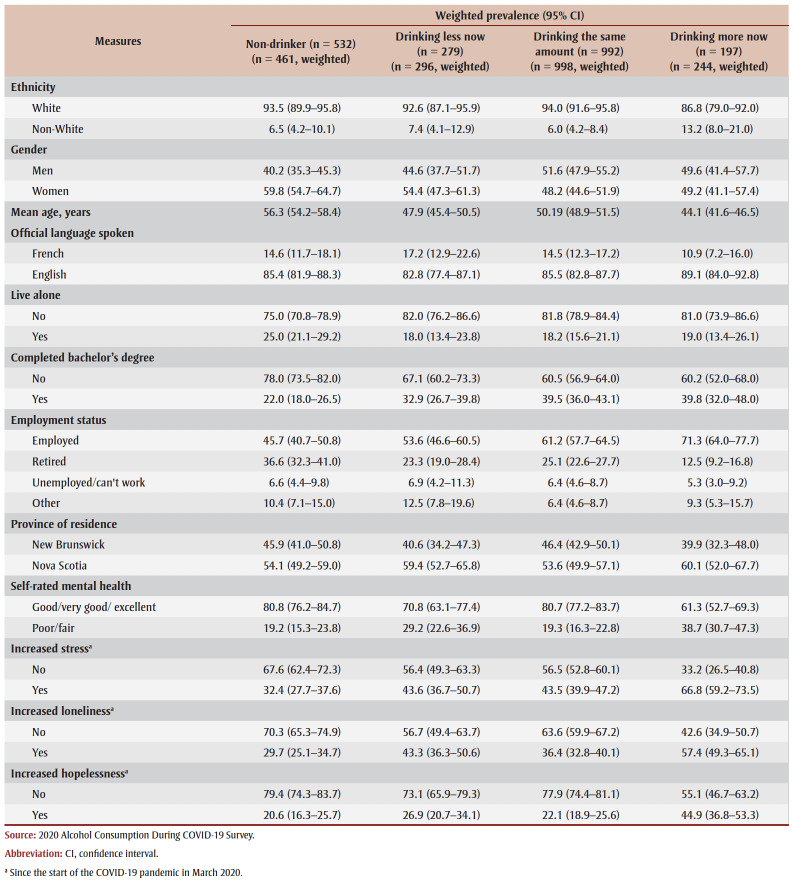

Table 1. Survey respondents’ characteristics, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (N = 2000).

|

To collect data for sensitivity analyses, respondents were asked a separate question about alcohol consumption: “At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, how would you describe your drinking?” Response options were as follows: “I was drinking more often”; “I was consuming a greater number of drinks when I drink”; “I was drinking both more often and in higher amounts”; “I was drinking less often and/or fewer drinks”; “My drinking was about the same as before COVID-19”; and “I don’t drink.” Response options were collapsed to measure drinking more often/higher amounts, drinking the same, drinking less often/fewer drinks and non-drinking.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Of the 2000 participants included in the analysis, 51.9% identified as women; participants’ mean (SD) age was 50.5 (17.2) years (see Table 1). Most respondents were White (92.8%), spoke English (85.5%) and lived with others (80.2%). Just over a third had completed a bachelor’s degree (34.5%). Over a half were employed full- or part-time (57.7%), and 26% were retired and 6.4% unemployed. Over three-quarters reported good to excellent mental health and well-being (76.9%), and the same proportion (76.9%) reported drinking alcohol.

One-eighth of the respondents (12.2%) reported that they had started drinking more frequently since March 2020, 49.9% reported that they were drinking about the same, 14.8% reported that they were drinking less and 23.1% reported that they did not drink. In terms of emotional distress, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 43.5% of respondents reported feeling increased levels of stress, 38.4% reported increased feelings of loneliness and 25.3% reported increased feelings of hopelessness.

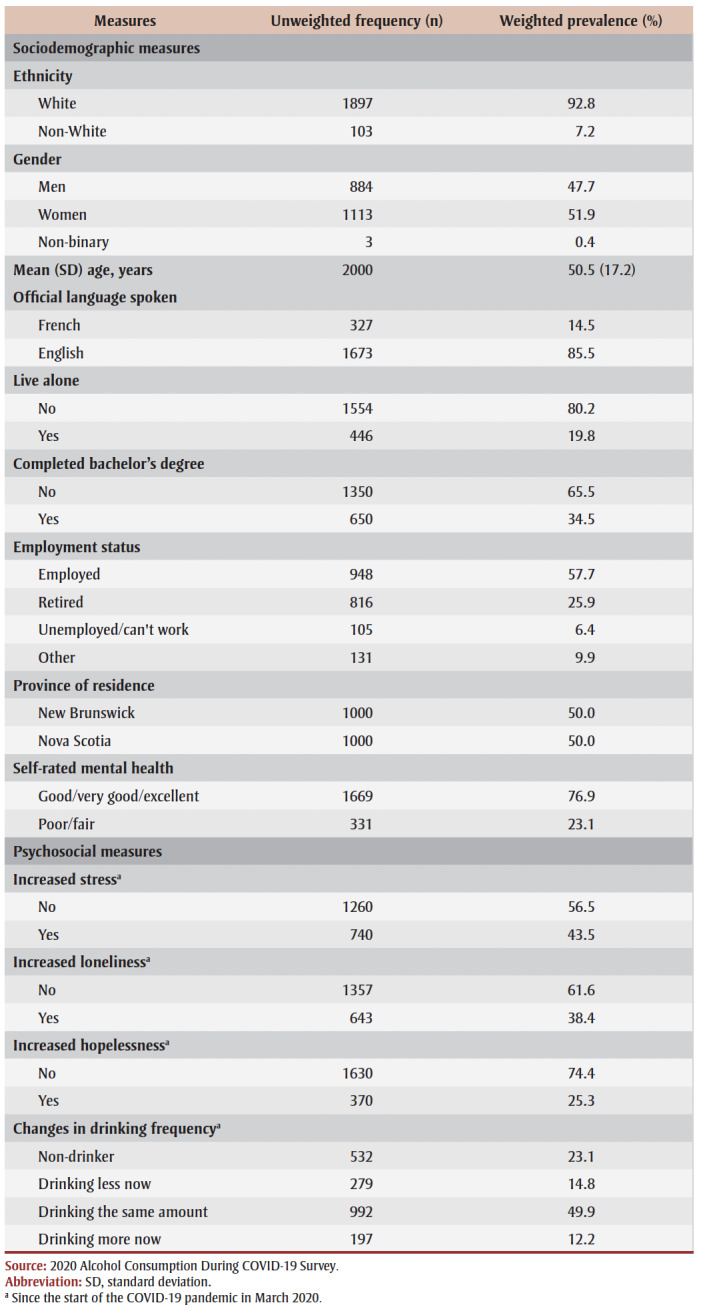

Across sociodemographic and psychosocial covariates, women, respondents without a bachelor’s degree and retirees were more likely to be non-drinkers (see Table 2). Respondents who reported more frequent drinking since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were, on average, younger and more likely to report fair or poor mental health and higher rates of stress, loneliness and hopelessness.

Table 2. Changes in drinking frequency since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic across sociodemographic and psychosocial covariates, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (N = 2000).

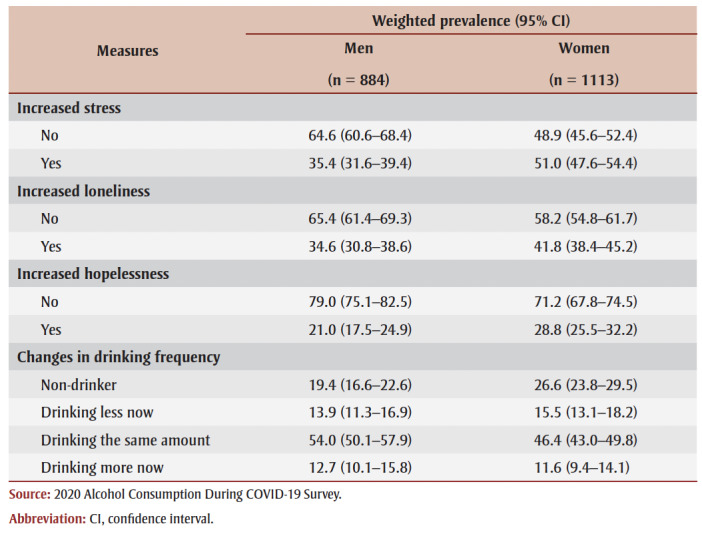

Male respondents were more likely than female respondents to report being drinkers, while female respondents were more likely to report feelings of stress and of hopelessness since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 3).

Table 3. Increased stress, loneliness and hopelessness, and changes in drinking frequency since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, by gender, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (N = 2000).

|

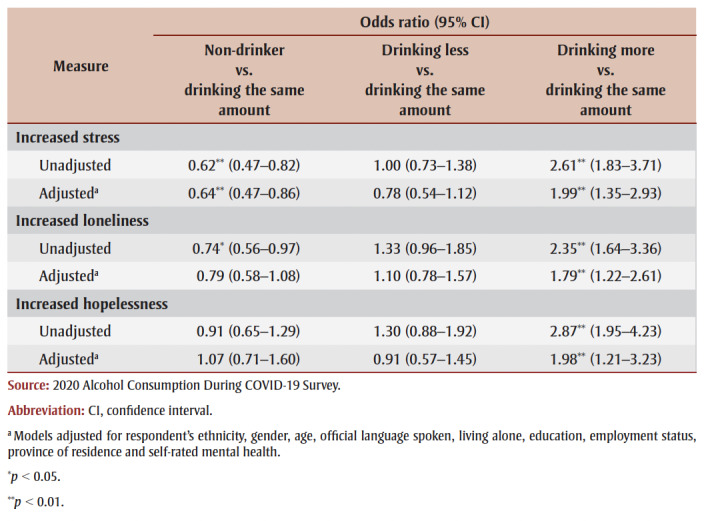

Main effects regression results

Adjusted estimates from multinomial regression models of changes in drinking frequency indicate an association between increased feelings of stress (odds ratio [OR] = 1.99; 95% CI: 1.35–2.93), loneliness (1.79; 1.22–2.61) and hopelessness (1.98; 1.21–3.23) since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and increases in drinking frequency (see Table 4).

Table 4. Unadjusted and adjusted multinomial logistic regression models of changes in drinking frequency and increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (N = 2000).

|

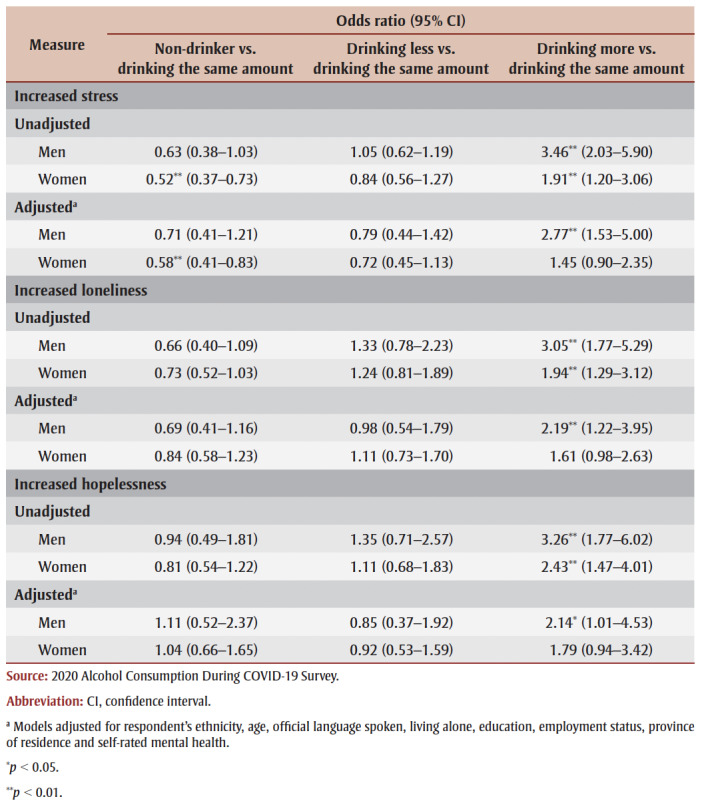

Stratified regression results

In unadjusted multinomial logistic regression models, increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness were associated with drinking more frequently for both men and women. However, after adjusting for ethnicity, age, official language spoken, family status (living alone or not), education, employment status, province of residence and self-rated mental health, these associations remained only for men (see Table 5).

Table 5. Unadjusted and adjusted multinomial logistic regression models of changes in drinking frequency since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic on increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness stratified by gender.

|

Increased feelings of stress (OR = 2.77; 95% CI: 1.53–5.00), loneliness (2.19; 1.22–3.95) and hopelessness (2.14; 1.01–4.53) among men were each associated with drinking more frequently since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in each model, the confidence intervals for male and female respondents overlap, pointing to a lack of moderation by gender. We further assessed the interaction of gender and each measure of emotional distress in our main effects’ models of changes in drinking frequency since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. All gender interaction terms were nonsignificant, which aligns with the results from our stratified models.

Sensitivity analyses

We re-analyzed the main effect models based on collapsed responses to the separate question about alcohol consumption: “At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, how would you describe your drinking?” Adjusted models indicated similar associations between increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness, with increased drinking during the pandemic, though effect size estimates were reduced. (Data available on request from the authors.) To confirm the temporal effects of the association of changes in emotional distress with changes in drinking frequency as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic, we assessed the association of increased feelings of stress, loneliness and hopelessness on sustained heavy drinking (those who reported drinking similar amounts across time periods at a high level—defined as drinking between 4days per week to daily/multiple times per day). For all three measures, stress (p=0.69), loneliness (p=0.097) and hopelessness (p=0.14), there was no association between increased feelings and sustained heavy drinking. This observation further supports the finding that pandemic-related emotional distress may be associated with changes in drinking frequency.

Discussion

This study reveals important associations between drinking behaviour and emotional distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar proportions of adults reported drinking more (12.2%) versus less (14.8%) frequently since the start of the pandemic. This divergent pattern has also been observed in other recent studies16,22 and speaks to the unique ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with alcohol consumption. Rehm and colleagues12 posit that the burden posed by the pandemic pushes some people to self-medicate with alcohol, while pandemic-related restrictions on alcohol access and availability cause others to reduce their consumption. Our interest lies in trying to understand why some people have increased their drinking frequency during the pandemic.15,25

We found that individuals who reported increased levels of stress, loneliness and hopelessness since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to report increased frequency of drinking during this time. While heightened distress is a common response to the uncertain circumstances resulting from disasters and public health crises,38,40-42 some individuals may adopt alcohol consumption as a maladaptive coping strategy.11 The underlying reasons cited typically include uncertainty about employment, financial strain, disruptions in daily life and concerns about the health of loved ones.41,42 Beyond the direct health threat, COVID-19 presents many uncertainties related to quarantine, intermittent restrictions on access to schools, workplaces and other public venues and feelings about social isolation. Since the start of the pandemic, a large proportion of respondents indicated increased feelings of stress (43.5%), loneliness (38.4%) and hopelessness (25.3%), with significantly higher rates reported among women. Sex/gender differences in stress response are well documented.43,44 The differences in stress response may be exacerbated by the pandemic because women are the predominant caretakers of children and make up the higher proportion of frontline health care staff;31 in addition, women’s participation in the workforce dropped more than men’s in the early months of the pandemic.45

While our study only investigates association, rather than causation, our results suggest that some individuals may have used alcohol to cope with pandemic-related emotional distress. The respondents who reported increased feelings of stress, loneliness and/or hopelessness were roughly twice as likely to report drinking more frequently since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This highlights a worrying trend that merits further investigation.

Our findings aligns with those of previous studies on the role of substance use as a form of coping or self-medicating in times of distress, more generally, and in response to acute traumatic events or disasters.6,7,11 This also touches on the comorbid nature of problematic substance use and poor mental health.46 Interestingly, despite the higher rates of stress, loneliness and hopelessness reported by women, gender-stratified analyses found that heightened emotional states were significantly associated with more frequent drinking among men, but not women. Previous research has found that men’s and women’s distress response and coping strategies differ considerably,47 with men more likely to respond to emotional distress with substance use.9 In general, women are more likely to seek social support in times of stress, an option limited by pandemic-related restrictions and reduced access to more adaptive coping strategies.48,49 Conversely, men tend to avoid coping altogether or to externalize their coping response. As such, the observation of an association of distress and increased drinking frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic should come as no surprise.50

Several studies indicate that the psychosocial burden of the COVID-19 pandemic merits increased intervention on societal, community and individual levels.5 A review of jurisdictional approaches to reducing population distress and increasing compliance with pandemic restrictions could be beneficial,51 based on our findings. Alcohol consumption motivated by emotional distress may decline as increased attention is paid to the psychosocial burden of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

First, data for this study were cross-sectional and our key exposure and outcome measures relate to events measured at a single point in time; thus, we cannot infer causal order or effect (e.g. individuals who consume more alcohol during the pandemic may experience increased distress as a result).

Second, responses were drawn from self-reports and therefore subject to response bias, including social desirability bias and recall bias. This may particularly affect assessments of past drinking behaviour and drinking frequency changes, though associations with emotional distress were consistent when we used an alternative measure of changes in drinking. Related to this, the third limitation of this study is the low response rate of 10%–14%, which likely introduces non-response bias. Such low response rates are expected for market research firms as they include all cases where a telephone number or a request to a random panel did not result in a completed questionnaire, including telephone numbers that are no longer in service and numbers for businesses and organizations, all of which inflate the non-response rate. With respect to non-response bias, some categories of people would logically be more likely to complete the survey (i.e. retirees, people working remotely) than others (i.e. essential workers who are less likely to be home to answer the telephone).

While data were weighted to be representative of the age, sex and regional profiles of the adult population in each province, it is likely that our data are not fully representative. However, the association between lower response rates and high bias are generally not supported in the literature.34-36 Fourth, we are unable to examine whether alcohol consumption and emotional distress vary according to sex because the dataset only includes gender expression.

Finally, this study includes only respondents from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, two provinces that have fared relatively well in terms of the COVID-19 caseload and the extent and duration of pandemic-related restrictions imposed. As such, these results may not be generalizable to other regions of Canada.

While recognizing these limitations, this study contributes to a timely and important research area. Our findings demonstrate the need to consider the unintended consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated far-reaching public health measures. This natural experiment suggests that around one in ten people used alcohol as a form of self-medication during this distressing period, meaning that future public health messaging should including warnings against emotionally motivated alcohol consumption and other high-risk drinking behaviours.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial indirect impacts on the health and well-being of Canadians. Pandemic-related restrictions have affected many individuals’ daily lives, shaping their levels of distress and how they are able to cope. These increased levels of distress commonly affected between one-quarter and nearly one-half of respondents, but were disproportionally experienced by women.

This study found that adults who reported feeling increased levels of stress, loneliness and hopelessness since the start of the pandemic consumed alcohol more frequently than they did pre-pandemic and that alcohol use increased among more than one in ten individuals. However, this association was largely restricted to men. Future research should seek to provide a more careful examination of the factors shaping increased alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an aim to implement strategies to shape reduced or less harmful consumption or mitigate the impact of feelings of distress on Canadians’ health. Understanding how the pandemic has affected mental health and associating drinking may help inform alcohol control policies and public health interventions that can minimize alcohol-related harm.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, and a grant from the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation, the New Brunswick Health Research Foundation, and the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency as part of a joint response to fund COVID-19 related research (Grant number COV2020-089). Funders were not involved in the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

MA, KT and DD were involved in the conceptualization of the work and funding acquisition.

MA and TL conducted formal analysis.

MA, KT and KM jointly wrote the original draft.

DD, KM, SB and TL reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- McPhee MD, Keough MT, Rundle S, Heath LM, Wardell JD, Hendershot CS, et al. Depression, environmental reward, coping motives and alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020:574676. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza CA, Ewing L, Heath NL, Goldstein AL, et al. When social isolation is nothing new: a longitudinal study on psychological distress during COVID-19 among university students with and without preexisting mental health concerns. Can Psychol. 2021:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Wu Y, Bonardi O, et al, et al. Comparison of mental health symptoms prior to and during COVID-19: evidence from a living systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv [Preprint] :evidence from a living systematic review and meta–analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Horesh D, Lev-Ari R, Hasson-Ohayon I, et al. Risk factors for psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: loneliness, age, gender, and health status play an important role. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25((4)):925–33. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S, Mota N, Bolton J, Sareen J, et al. Self-medication with alcohol or drugs for mood and anxiety disorders: a narrative review of the epidemiological literature. Depress Anxiety. 2018:851–60. doi: 10.1002/da.22771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Gabhainn SN, Roberts C, et al, et al. Drinking motives and links to alcohol use in 13 European countries. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75((3)):428–37. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntshce E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S, Sher KJ, et al. The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders. Oxford(UK): Motivational models of substance use: a review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco; pp. 375–421. [Google Scholar]

- Peltier MR, Verplaetse TL, Mineur YS, et al, et al. Sex differences in stress-related alcohol use. Neurobiol Stress. 2019:100149–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinle MI, Sinha R, et al. The role of stress, trauma, and negative affect in alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorder in women. Alcohol Res. 2020;40((2)):05–421. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.2.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Kempe T, Rapinda KK, et al, et al. Drinking to cope during COVID-19 pandemic: the role of external and internal factors in coping motive pathways to alcohol use, solitary drinking, and alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44((10)):2073–83. doi: 10.1111/acer.14425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Kilian C, Ferreira-Borges C, et al, et al. Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19: implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39((4)):implications for monitoring and policy–83. doi: 10.1111/dar.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeij MC, Suhrcke M, Toffolutti V, Mheen D, Schoenmakers TM, Kunst AE, et al. How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: a realist systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015:131–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AC, Ward KD, et al. Understanding post-disaster substance use and psychological distress using concepts from the self-medication hypothesis and social cognitive theory. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50((2)):177–86. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2017.1397304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob L, Smith L, Armstrong NC, et al, et al. Alcohol use and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study in a sample of UK adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021:108488–86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Ottawa(ON): 25% of Canadians (aged 35-54) are drinking more while at home due to COVID-19 pandemic; cite lack of regular schedule, stress and boredom as main factors. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Litt DM, Stewart SH, et al. Drinking to cope with the pandemic: the unique associations of COVID-19-related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict Behav. 2020:106532–86. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS): summary of results for 2017 [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary.html. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Ottawa(ON): 2020. Canadian substance use costs and harms: 2015– 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky JS, Stall NM, Silverstein WK, et al, et al. Alcohol sales and alcohol-related emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Intern Med. 2021 doi: 10.7326/M20-7466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Victoria. Victoria(BC): Alcohol consumption in BC during COVID-19 [Internet] Available from: https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/stats/alcohol/index.php. [Google Scholar]

- Rotermann M, et al. Statistics Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canadians who report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic more likely to report increased use of cannabis, alcohol and tobacco. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.pdf?st=B5oO34OM. [Google Scholar]

- Zajacova A, Jehn A, Stackhouse M, Denice P, Ramos H, et al. Changes in health behaviours during early COVID-19 and socio-demographic disparities: a cross-sectional analysis. Can J Public Health. 2020;111((6)):953–62. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00434-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Lucas DA, Dailey NS, et al. Alcohol dependence during COVID-19 lockdowns. Psychiatry Res. 2021:113676–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodkiewicz J, Talarowska M, Miniszewska J, Nawrocka N, Bilinski P, et al. Alcohol consumption reported during the COVID-19 pandemic: the initial stage. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17((13)):E4677–62. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callinan S, Mojica-Perez Y, Wright CJ, et al, et al. Purchasing, consumption, demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with shifts in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021;40((2)):183–91. doi: 10.1111/dar.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74((11)):964–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigo D, Patten S, Pajer K, et al, et al. Mental health of communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65((10)):681–7. doi: 10.1177/0706743720926676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Borah SB, et al. COVID-19 and domestic violence: an indirect path to social and economic crisis. J Fam Violence. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis C, et al. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Ottawa(ON): 2020. Open versus closed: the risks associated with retail liquor stores during COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo PA, Joffe H, teach us, et al. Sex and gender differences in health: what the COVID-19 pandemic can teach us. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173((5)):385–6. doi: 10.7326/M20-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger Opinion | LEO [Internet] Leger. Available from: https://leger360.com/services/legeropinion-leo/ [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair M, O’Toole J, Malawaraarachchi M, Leder K, et al. Comparison of response rates and cost-effectiveness for a community-based survey: Postal, internet and telephone modes with generic or personalised recruitment approaches. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12((1)):132–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendra R, Hill A, et al. Rethinking response rates: new evidence of little relationship between survey response rates and nonresponse bias. Eval Rev. 2019;43((5)):307–30. doi: 10.1177/0193841X18807719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeter S, Miller C, Kohut A, Groves RM, Presser S, Opin Q, et al. Consequences of reducing nonresponse in a national telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2000:125–48. doi: 10.1086/317759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Washington(DC): Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2012/05/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys/ [Google Scholar]

- CCSA. Ottawa(ON): Health and public safety: impacts of COVID-19 on substance use [Internet] Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/Impacts-COVID-19-Substance-Use. [Google Scholar]

- Esterwood E, Saeed SA, Psychiatr Q, et al. Past epidemics, natural disasters, COVID19, and mental health: learning from history as we deal with the present and prepare for the future. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91((4)):1121–33. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper LH, Erikson FF, et al. Gender differences and association between psychological stress and alcohol consumption: a systematic review. J Alcohol Drug Depend. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F, Jhajj AK, Stewart DE, Burghardt M, Bierman AS, et al. Single item measures of self-rated mental health: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14((398)):398–33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew QH, Wei KC, Vasoo S, Chua HC, Sim K, Med J, et al. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population: practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Med J. 2020:350–6. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh KY, Kao WT, Li DJ, et al, et al. Mental health in biological disasters: from SARS to COVID-19. Mental health in biological disasters: from SARS to COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Manuel G, et al. Gender differences in reported stress response to the loma prieta earthquake. Sex Roles. 1994;30((9-10)):725–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kriska M, et al. Neuroendocrine response during stress with relation to gender differences. Neuroendocrine response during stress with relation to gender differences. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Warsz) 1996;56((3)):779–85. doi: 10.55782/ane-1996-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Just the facts: International Women’s Day 2021 [Internet] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-28-0001/2018001/article/00020-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Capasso A, Jones AM, Ali SH, Foreman J, Tozan Y, DiClemente RJ, et al. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: the effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S. Prev Med. 2021:106422–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matud MP, et al. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;37((7)):1401–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek JT, Smith RE, Dodge K, et al. Gender differences in coping with stress: when stressor and appraisals do not differ. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1994;20((4)):421–30. [Google Scholar]

- ndez JC, Mayordomo T, Sancho P, s JM, et al. Coping strategies: gender differences and development throughout life span. Span J Psychol. 2012;15((3)):1089–98. doi: 10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n3.39399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR, et al. Drinking to cope among college students: prevalence, problems and coping processes. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63((4)):486–97. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberoth A, ckli S, et al. Stress and worry in the 2020 coronavirus pandemic: relationships to trust and compliance with preventive measures across 48 countries in the COVIDiSTRESS global survey. R Soc Open Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1098/rsos.200589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]