Abstract

Introduction

The systematic collection of electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) in the routine care of patients with chronic haematological malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and myelodysplasia syndromes (MDS) can constitute a very ambitious but worthwhile challenge. MyPal is a Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation Action aiming to meet this challenge and foster palliative care for patients with CLL or MDS by leveraging ePRO systems to adapt to the personal needs of patients and caregiver(s).

Methods and analysis

In this interventional randomised trial, 300 patients with CLL or MDS will be recruited across Europe. Patients will be randomly allocated to early palliative care using the MyPal system (n=150) versus standard care including general palliative care if needed (n=150). Patients in the experimental arm will be given access to the MyPal digital health platform which consists of purposely designed software available on smartphones and/or tablets. The platform entails different functionalities including physical and psychoemotional symptom reporting via regular questionnaire completion, spontaneous self-reporting, motivational messages, medication management and a personalised search engine for health information. Data on patients’ activity (daily steps and sleep quality) will be automatically collected via wearable devices.

Ethics and dissemination

The integration of ePROs via mobile applications has raised ethical concerns regarding inclusion criteria, information provided to participants, free and voluntary consent, and respect for their autonomy. These have been carefully addressed by a multidisciplinary team. Data processing, dissemination and exploitation of the study findings will take place in full compliance with European Union data protection law. A participatory design was adopted in the development of the digital platform involving focus groups and discussions with patients to identify needs and preferences. The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of San Raffaele (8/2020), Thessaloniki ‘George Papanikolaou’ Hospital (849), Karolinska Institutet (20.10.2020), University General Hospital of Heraklion (07/15.4.2020) and University of Brno (01-120220/EK).

Trial registration number

Keywords: leukaemia, health informatics, adult palliative care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

MyPal ADULT is a multicentre randomised interventional study in palliative care using an innovative approach based on electronic patient-reported outcome-based systems to improve the quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

This is an international study involving five clinical sites with long-standing expertise in the management of patients with CLL and MDS.

MyPal system developers have interacted extensively with end users from its initial development and will continue until its evaluation, thus putting down the basis for successful user engagement.

Considering the median age of diagnosis of about 70 years for both CLL and MDS, use of eHealth systems might be challenging, requiring comprehensive training and possibly leading to higher than expected attrition rate.

The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed study initiation and might require ad hoc adaptations to data collection processes during the study.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are two of the most frequent haematological malignancies in the Western world usually occurring in older individuals (median age at diagnosis of around 70 years).1 2 These diseases, though generally chronic, are considerably heterogeneous in underlying biology, presentation and clinical course, ranging from relatively indolent to extremely aggressive. Recent scientific advances have revolutionised the therapeutic landscape through the introduction of novel therapies, resulting in improved outcomes, including increased overall survival.3 That said, both CLL and MDS remain essentially incurable and current therapies aim at controlling the disease long term. Due to this, open issues abound regarding the impact of CLL and MDS and their treatment on quality of life (QoL) because of disease-related symptoms, the toxic effects of therapy, and the emotional, socioeconomic, and functional effects of living with an incurable illness, especially considering the likely association with other comorbidities due to advanced age.4

Evidence suggests that patients with CLL have poorer QoL compared with the general population, being significantly bothered by physical symptoms (81% reporting fatigue and 56% sleep disturbances) at treatment initiation.5 Similarly, patients with MDS may suffer from a wide variety of symptoms, including fatigue, anxiety and insomnia, among others, which result in impaired QoL.6 7 This is highly relevant in light of the recent therapeutic shift from fixed duration intravenous chemoimmunotherapy to continuous oral therapies for which patient compliance and treatment adherence are key to obtaining long-lasting disease control. Following this paradigm shift, palliative care, meant as the management of physical symptoms and psychosocial distress throughout the disease course, has come to play a key role.

Changes in the patients’ experience across the illness trajectory can be captured and measured using patient-reported outcomes (PROs). PROs typically refer to the use of standardised, validated self-report questionnaires, and they could be considered the gold standard as far as subjective experiences are concerned.8 9 PROs are typically employed as part of clinical trials, for example, in order to support drug safety studies, and to this end, systematic reporting processes and specific terminologies are actively developed and investigated.10 Furthermore, PROs have a major role in improving the quality of palliative care, like facilitating physician–patient communication and symptom management.11 Their consideration along with clinical and laboratory data within the palliative care clinical setting can help provide patients with the most appropriate support.12 Specifically, in palliative care throughout the disease journey, PROs can: (1) monitor changes in the patients’ health status; (2) facilitate the identification of unmet needs which could have been overlooked (psychological, social, physical, etc); (3) provide information on the evolution of disease and the impact of treatment interventions; (4) promote patient/physician interaction and communication; and (5) aid clinical decision-making.10 13

The process of collecting PROs has progressed along technical advances, in particular through the introduction of the eHealth paradigm, defined as the use of information and communications technology in support of health.14 eHealth interventions might target the active capture of measurements from the patients themselves, as is the case with the electronic implementation of PROs (ePROs). In fact, ePROs have been found to contribute to improved health outcomes in patients with cancer, for example, improvement in physical activity,15 reduction in anxiety and drowsiness,16 lower levels of fatigue, nausea, insomnia17 and pain intensity, as well as significant improvement in emotional and social functioning.18

The systematic collection of ePRO information in routine CLL and MDS practice can constitute a very ambitious but worthwhile challenge. MyPal is a Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation Action aiming to meet this challenge and foster palliative care for patients with CLL and MDS by leveraging ePRO systems to adapt to the personal needs of the patient and his/her caregiver(s). MyPal aspires to empower patients and their caregivers in capturing more accurately their symptoms/conditions, communicate them in a seamless and effective way to their healthcare providers (HCPs) and, ultimately, foster action through advanced methods of identification of important deviations relevant to the patient’s state and QoL. MyPal will evaluate the proposed intervention for adults with CLL and MDS through a carefully designed randomised controlled trial (RCT) that will be conducted in diverse healthcare settings across Europe.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This is a multinational RCT, enrolling patients with CLL or MDS at five clinical sites in Europe. The methodological approach of the study involves patients’ use of a mobile application with a range of functionalities as well as a FitBit smartwatch. Patients will be able to conveniently self-report via the MyPal mobile application using ePROs as outcome measures while the Fitbit will also be collecting data on patients’ physical activity. The main aim of the MyPal ADULT is to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of use of the MyPal ePRO system as a novel, patient-centred, palliative care intervention for patients with haematological malignancies (CLL or MDS).

Objectives and outcome measures

Primary objective

The main objective is to determine whether the MyPal ADULT intervention can lead to improved QoL compared with standard care as evidenced by statistically significant higher scores in the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life QLQ-C3019 General Questionnaire and the Euroqol 5-dimension (EQ-5D).20

Secondary objectives

To determine whether—compared with standard care—the MyPal system intervention can lead to the following outcomes in patients with CLL or MDS:

Improvement in physical and emotional functioning as evidenced by higher scores in the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale (IPOS)21 at prespecified time points (please refer to the Reporting period section).

Increase in satisfaction with care as evidenced by higher scores in the EORTC Patient Satisfaction with Cancer Care questionnaire22 at prespecified time points.

Increase in overall survival as evidenced by longer survival times.

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the MyPal intervention compared with standard care, taking into account the Euroqol EQ-5D data from both groups as well as other parameters such as hospital visits, doctor visits, hospitalisations, medications, treatments and investigations.

To determine whether the MyPal system intervention can lead to the following outcomes in patients with CLL or MDS over time:

Reduced symptom burden as evidenced by lower scores in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)23 at prespecified time points.

Reduced pain score as evidenced by lower scores in the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)24 at prespecified time points.

Reduced emotional distress as evidenced by lower scores in the Emotion Thermometers (ET)25 at prespecified time points.

Increase in patient engagement in care as evidenced by satisfactory adherence to reporting (eg, 70% answered scheduled reports).

Patient recruitment

Patients (n=300) will be recruited from the following five clinical centres across four European countries:

Karolinska Institutet (Sweden).

Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele (Italy).

University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete (Greece).

University Hospital Brno (Czech Republic).

G Papanicolaou Hospital of Thessaloniki (Greece).

All consecutive patients with CLL (as well as small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), a condition equivalent to CLL) or MDS who visit the participating centres will be screened and asked to participate in the MyPal study. Patients should fulfil the eligibility criteria highlighted in box 1 for enrolment. The patient recruitment started in January 2021 (first patient in 04 January 2021) and it is planned to end by December 2021.

Box 1. Eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Adults (≥18 years).

Diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), a condition equivalent to CLL or myelodysplasia syndromes (MDS).

Scheduled to receive any line of treatment for CLL/SLL or MDS or who have been previously exposed to any treatment for CLL/SLL or MDS.

Able to understand and communicate in the respective language.

Users of an internet-connected device (smartphone/tablet).

Exclusion criteria

Patients who are already participating in another interventional study.

Patients needing immediate referral for specialised palliative care.

Any life-threatening illness, medical condition or organ system dysfunction that, in the attending physician’s opinion, could compromise the subject’s safety or put the study outcomes at undue risk.

Life expectancy <3 months.

For the CLL/SLL cohort: patients who have experienced Richter’s transformation.

Randomisation

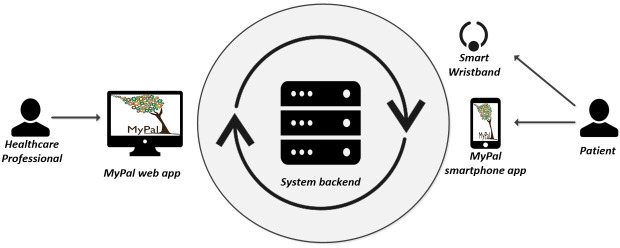

Patients will be randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion to receive early palliative oncology care using the MyPal digital health platform (intervention group) versus standard care which could include general palliative care if needed (control group), stratified by cancer type (ie, CLL/SLL vs MDS), using a computer-generated number sequence, based on blocked randomisation approach.26 The assignment of each patient will be conducted during his/her enrolment phase (figure 1) with no prior knowledge for the enrolling clinicians, in order to avoid biases.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the study design. ePROs, electronic patient-reported outcomes.

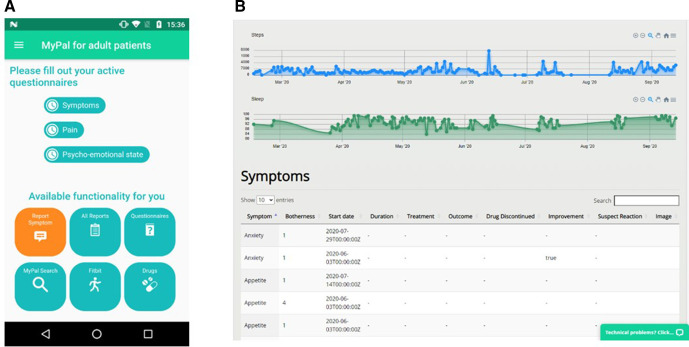

MyPal digital health platform

The intervention consists of the use of the MyPal digital health platform. The system will be used by the patients who participate in the intervention arm of the trial and by the participating HCPs, while patients participating in the control group (the standard arm of the trial) will not use the system. Access to the MyPal digital health platform (figure 2) will be granted to the patients for 12 months of continuous use right after their enrolment in the trial. HCPs will have access to the system until the end of the trial. Patients will be informed that the MyPal eHealth system is not meant to be used as an emergency service and urgent issues have to be reported following standard care procedures.

Figure 2.

Software and hardware modules of the MyPal digital health platform.

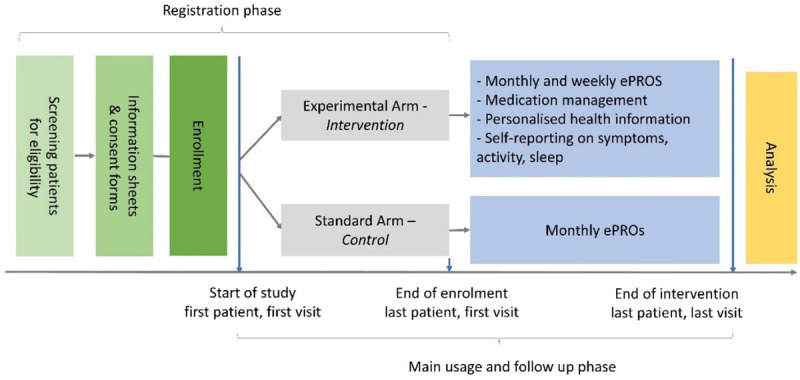

The intervention focuses on the reporting of physical and psychoemotional symptoms by the patient via the MyPal smartphone app installed on his/her personal smartphone or tablet (see sample screen in figure 3A). Furthermore, the reported symptom-related information is immediately delivered to the HCP via the MyPal web app which is the main interface of the HCP to the system (see sample web app page in figure 3B). Finally, the smart wristband, Fitbit Ionic, a commercial activity tracking device that will be employed for monitoring the physical activity and the sleep quality of the patient, will be provided by the site personnel. Despite the fact that the presentation of the technical infrastructure is considered out of this paper’s scope, it should be highlighted that the system backend infrastructure stores the collected data focusing on information security best practices.

Figure 3.

Sample graphical user interfaces of the MyPal eHealth system: (A) screen of the MyPal smartphone app; (B) page of the MyPal web app.

The patient’s perspective

From the patient’s perspective, both system-initiated functionalities (ie, functionalities for which the system decides when they become available to the user) and user-initiated functionalities (ie, functionalities that the user has access to at all times) offered via the MyPal smartphone app can be seen in table 1.

Table 1.

The system-initiated and user-initiated functionalities offered in the MyPal smartphone app

| System-initiated functionality | Description | |

| PS1 | Physical symptom questionnaires | Notifications to complete physical symptom questionnaires are issued once per week. |

| PS2 | Psychoemotional symptom questionnaires | Notifications to complete a psychoemotional symptom questionnaire are issued once per week. |

| PS3 | Screener questionnaires | Notifications to complete a screener questionnaire concerning (1) the patient’s ongoing engagement with the MyPal Study, and (2) the risk of medication non-adherence. Responses will determine the motivational messages that patients will be receiving and the highest priority topics for the discussion guide presented to the HCP (issued at months 0, 3 and 6). |

| PS4 | Motivational messages | Tailored short motivational messages presented to the patient. Their content is determined based on a custom algorithm that receives input from patient responses (issued twice weekly until week 4, then once weekly until week 24). |

| PS5 | Medication reminders | Notifications that remind the patient to take their medication; determined by the patient via the medication management functionality. |

| User-initiated functionality |

Description | |

| PU1 | Spontaneous symptom reporting | A form that is used by the patient to spontaneously report physical or psychoemotional symptoms in a structured or unstructured way. |

| PU2 | Medication management | An editable list of the patient’s medication plan along with the dosage and the frequency of intake. |

| PU3 | Personal health information recommender | A personalised search engine that retrieves health information related to health status of the patient. |

| PU4 | Self-reported information review | A view that presents the patient’s past responses to physical and psychoemotional questionnaires. |

| PU5 | Activity information review | A view that presents past daily step count and sleep quality indicators acquired by the commercial wristband. |

HCP, healthcare provider.

The main phases for the enrolled patients’ point of view include a registration phase, a main usage phase and a follow-up phase, and can be summarised as follows:

Registration phase

This phase is completed the first time the patient uses the MyPal smartphone/tablet app, and aims at (1) registering the patient into the MyPal system, (2) initially setting a number of preferences, (3) collecting via self-reporting the baseline assessment of the patient’s physical and psychoemotional symptoms, and (4) screening for motivational targets and non-adherence risk. The smartphone app guides the patient throughout the entire registration process in a wizard-like fashion. In case needed, the patient might get some help for completing the registration from an HCP (eg, research nurse) participating in the study.

Main usage phase

This phase lasts 6 months (month 1–month 6 of the patient’s participation in the study) and, during this time, the patient is given access to a number of user-initiated and system-initiated ones. Two main types of notifications can be distinguished, namely the intervention notifications (ie, notifications associated with functionalities that are part of the interventions) and the assessment notifications (ie, notifications informing the patient it is time to complete the assessment questionnaires).

Follow-up usage phase

The follow-up usage phase starts immediately after the completion of the main usage phase and it also lasts 6 months (month 7–month 12 of the patient’s participation). During this phase, however, the smartphone app does not issue assessment notification monthly; instead it issues only one such notification at the end of month 12.

The HCP’s perspective

Τhe functionalities offered via the HCP web app are reported in table 2.

Table 2.

Functionalities of the MyPal web app

| Functionality | Description | |

| H1 | Incoming information summary | A central page of the web app which lists the incoming patient information that has not been reviewed yet. The summarised incoming information is automatically prioritised in the system backend with the help of custom algorithms and the pieces of incoming information that are assigned the highest priority and placed on the top of the list. |

| H2 | Individual data dashboard | A page that presents, using a dashboard with modern visualisations, all the information that has been collected for a given patient since the beginning of the trial. The information includes (1) patients’ responses to the symptom questionnaires; (2) the spontaneous symptom reports; (3) the self-reported medication via the smartphone app; (4) the appointment schedule; (5) the daily number of steps and sleep quality as tracked by the commercial smart wristband; (6) relevant clinical information (age, gender, diagnosis, treatment-naïve/relapsed, stage or risk, treatment to be given, info on expected outcome, Karnofsky index at the time of inclusion, comorbidities). |

| H3 | Aggregated data dashboard | A page that presents, using an analytics dashboard with modern visualisations, aggregated and summarised information coming from all patients who participate in the trial (descriptive statistics such a min, max, average and percentiles). |

| H4 | Discussion guide | A page that provides a personalised discussion guide to be used during an appointment with a patient to mitigate potential risk of non-adherence with the intervention. This will be available to the HCP through the web interface before a patient’s visit. The discussion guide is personalised to the patient’s non-adherence risk screener results. |

| H5 | Information recommender repository update | A page used for editing the information that resides in the repository of the personal health information recommender. The HCP can upload documents or specify web resources that contain valid medical information. |

| H6 | HCP response log | A page used for logging potential responses of the HCP to the presented information of a specific patient. The HCP can log in a structured manner any actions taken after visiting individual data dashboard of a patient. |

HCP, healthcare provider.

The HCPs need to follow a simple registration process during their first entry in the MyPal web app. During the main usage of the MyPal web app, the HCPs get access to the data that are collected by (1) the MyPal smartphone app and (2) the commercial smart wristband. The collected data become available to the MyPal web app in a ‘live’ fashion, as soon as they are stored. At an individual level, the HCP is authorised to access only the data of the patients of the associated clinical centre; however, access to aggregated and summarised data coming from all patients (descriptive statistics such as min, max, average and percentiles) will also be provided to all HCPs. HCPs are not actively notified by the MyPal system at any point in order to avoid ‘alert fatigue’-related issues and biases. The individual data of the participating patients of every clinical centre are planned to be reviewed by the associated HCPs at least once every 72 hours. Appropriate actions will be taken according to the HCP’s judgement and medical expertise. These actions will be recorded by the HCPs via the MyPal system, that is, referral for diagnostics, prescription of medication, etc.

As the MyPal eHealth system constitutes a complex intervention comprising of a number of individual elements, the fidelity of the intervention implementation will be evaluated by collecting the information on the web interface (to be completed by the HCPs accessing the system), including review of reported symptoms and questionnaires by HCPs (audit trail) and action taken by HCPs, if any.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection

Data collection will be undertaken by the MyPal digital health platform, which consists of the following modules:

The MyPal smartphone app. This will be used by the patients assigned to the study intervention group in order to report their physical and psychoemotional symptoms either spontaneously or periodically, as well as manage their medication intake, review their own data (eg, symptom trajectory), etc. Additionally, it will serve as the hub for the transfer of activity level and sleep quality data acquired by a commercial activity tracking device.

The MyPal web portal. This will be used by the HCPs participating in the study in order to monitor and periodically review the collected patient data, as well as to register certain data pertaining to a patient (eg, treatment plan, next appointment). The portal will also be used sporadically by the patients assigned to the study control group for answering the assessment ePRO questionnaires.

The MyPal backend and storage module. All patient data collected from the smartphone app and the web portal will be synchronised to the MyPal backend and storage module.

Types of data

Special categories of personal data collected during the study include:

Data collected in both experimental and standard arms:

Demographic (eg, age, gender).

Clinical information, including disease and treatment-related features, frequency of appointments and events occurring during the observation time.

-

PROs for study endpoint assessment (assessment questionnaires) to allow for a comparison:

The EORTC QLQ-C30 which is a 30-item QoL questionnaire, assessing important functioning domains, common cancer symptoms as well as the perceived financial impact of the disease and treatment.

The Euroqol, EQ-5D-3L, a 25-item general measure evaluating patients with regard to the following dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.

The IPOS, a 10-item questionnaire, specific to palliative care, which measures patients’ physical symptoms, psychological, emotional and spiritual, as well as information and support needs.

The Satisfaction with Cancer Care developed by the EORTC group which assesses patients’ perception of the quality of medical and nursing care, as well as the organisation of care and services of an oncology department.

Data collected in the experimental arm only:

FitBit derived (eg, activity and sleep patterns).

Symptoms (through both spontaneous and scheduled reporting).

-

PROs which are part of the intervention (intervention questionnaires) and will be deployed to monitor patient’s condition in MyPal:

The ESAS, a 10-item questionnaire assessing common symptoms experienced by patients with cancer.

The BPI, a nine-item questionnaire designed to assess cancer pain intensity, pain relief treatment or medication as well as pain interference in activities.

The ET, a tool which assesses emotional issues, namely distress, anxiety, depression and anger, as well as patients’ need for help through five visual analogue scales.

Reporting period

After the patients are enrolled in the study, they are asked to complete the assessment ePROs on a monthly basis (both groups) and the intervention/symptom ePROs on a weekly basis (intervention group only) for 6 months (main phase). In the follow-up phase, the patients of the intervention group continue completing the intervention ePROs as before, while both groups complete the assessment ePROs once more in the end of the phase.

Data security

The privacy-by-design paradigm27 has been employed to install appropriate data protection measures as early as possible in the development of the MyPal platform, in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (European Union (EU)) 2016/679.28 To this end, the necessary Data Protection Impact Assessments (n=2) were conducted. The first focusing on the management of data on local clinical sites (mobile apps, etc), and the second focusing on the management of aggregated data for further analysis (anonymisation of data, etc). These were thoroughly reviewed by the respective Data Protection Officers. The data protection security measures include (1) the storage of personally identifiable data only in the premises of clinical sites, (2) role-based data access, (3) password encryption, (4) use of the OAuth protocol (to minimise password-based authentication whenever possible), (5) network data transfer via the secure Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) protocol, etc.

Furthermore, adjusting the system architecture along the privacy-by-design paradigm, a decentralised deployment model of the MyPal platform, has been adopted encompassing one local installation per participating clinical centre in order to host personally identifiable information for all participating study subjects from the clinical centre in its own Information technology (IT) infrastructure. However, one central installation at the site of the study sponsor has also been deployed to host the assessment ePRO responses from all centres after they have been completely deidentified. It should be clarified that the link between the ID of the patient used in the context of MyPal study and the patient identification information (name, address, age, etc) exists, but this link never leaves the local clinical site environment.

Sample size calculation

Assuming relatively acceptable values for the attrition rate (ie, 20%) and the missing data (ie, 30%), the sample size analysis concluded that 300 recruited patients with CLL or MDS at any ratio providing one measure at enrolment (baseline) and seven repeated measures (at months 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 12) are sufficient for the power of the intended statistical testing to be over 90% in all cases, given (a) a 0.05 significance level and (b) an effect size of 0.2; the employed value of the effect size was based on a priori knowledge of the domain.

Data analysis plan

Descriptive statistics will be provided for demographic (gender, age group, origin, etc) and clinical characteristics (diagnosis, disease stage, etc) recorded at baseline. The aim of the analysis will be to evaluate the changes in outcome measures over time (1) in the experimental arm and (2) in the experimental arm in comparison with the standard arm, using one-way and two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (or a non-parametric equivalent), respectively. Post hoc analysis will be applied as appropriate. Subgroup analysis of the outcome measures will also be performed at baseline, month 6 and month 12 of the study using one-way, two-way and three-way ANOVA in order to detect potential differences between specific groups of participants. The grouping variables that will be employed are (a) the clinical centre (origin), (b) the country of residence, (c) the age group, (d) the disease stage and (e) the diagnosis (CLL, MDS). In case an interaction effect is observed, separate subgroup analyses in the CLL and MDS cohorts with repeated measures ANOVA will be performed to assess the effect of intervention on QoL and other outcome measures. The level of significance for all statistical tests is set to a=0.05, in accordance with the power calculations.

Monitoring

The study includes a Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). The DMC will be an independent and multidisciplinary committee consisting of three to four members such as clinicians who have expertise in haematological cancers, ethics and palliative care, and biostatisticians. They will have access to unblinded data and will monitor accumulating trial data at prespecified intervals in terms of safety and efficacy and in particular: quality including completeness and attrition, recruitment across sites and evidence for differences in the main outcome measures between arms. Any reports of serious adverse events such as safety or ethical issues will be brought to the attention of the principal investigators (PIs).

Safety reporting

Although no safety issues are foreseen, the PI will promptly notify all concerned investigators, the ethics committee(s) and the regulatory authorities of possible findings that could affect adversely the safety of patients, impact the conduct of the study, increase the risk of participation or otherwise alter the independent ethics committee (IEC)’s approval to continue the trial.

As the study population consists of individuals facing life-threatening illness, we would not expect it to be an unusual occurrence for patients to be admitted to hospital while taking part in the study. We expect that the most likely serious risk of participating in the MyPal intervention is (serious) distress. It should be noted however that symptom reporting is considered to be part of routine care, and as such, we expect the risks to be limited. Filling in questionnaires about physical and psychological symptoms, and QoL may also be upsetting for patients. However, we expect the risk to be limited as these are validated questionnaires that address issues that are discussed in usual care.

Ethics and dissemination

The integration of ePROs via mobile applications has raised ethical concerns regarding inclusion criteria, information provided to participants, free and voluntary consent, as well as respect for their autonomy. These have been carefully addressed by a multidisciplinary team, including experts in bioethics. Data processing as well as the dissemination and exploitation of the study findings will take place in full compliance with EU data protection law. A participatory design was adopted in the development of the digital health platform involving focus groups and discussions with patients in order to identify needs and preferences. The protocol (V.1.0 dated 16 December 2019, included in the online supplemental material) has received ethical approval from the ethics committee of San Raffaele Hospital (05 February 2020, registry number 8/2020), the ethics committee of General Hospital of Thessaloniki ‘George Papanikolaou’ (20.5.2020, registry number 849), ethics committee of Karolinska Institutet (20.10.2020), ethics committee of the University General Hospital of Heraklion (07/15.4.2020) as well as the ethics committee of the University of Brno (01-120220/EK).

bmjopen-2021-050256supp001.pdf (2.5MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The definition of key research questions was based on thorough search of the literature where communication with the healthcare team and better understanding of health-related information were of paramount importance for informed decision-making by the patient.29 A participatory design was adopted in the development of the digital health platform involving the established instrument of focus groups and discussions with patients in order to identify needs and preferences. In more detail, multiple focus groups have been organised in all MyPal clinical sites and the results analysed by means of established qualitative research methods to main themes/topics concerning the user needs.

Discussion

Digital health technologies offer the potential for rapid and spontaneous reporting of symptoms, facilitating remote monitoring and communication between patients and HCPs. They have been increasingly implemented in routine practice in all areas of healthcare, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, concerns remain about their acceptability to patients, especially older people, and the degree to which they may alter patient–clinician relationships in palliative care contexts.30 Therefore, it is important to rigorously test these interventions using robust research designs, highlighting usability and patient acceptability as top priorities.

The MyPal project aspires to offer a personalised approach for improving the delivery of early palliative care in patients with cancer, including CLL and MDS that typically affect the elderly. This will be achieved by empowering patients and their caregivers to actively participate in the care process through the use of digital health tools for self-reporting symptoms and events, QoL as well as any kind of perceived changes in their daily patterns occurring throughout the disease trajectory. Hence, MyPal has the ambition to formally prove the advantage and substantial improvement of eHealth systems as compared with traditional methods of palliative care for patients with cancer and promote self-control of health. By fostering active participation of patients in disease management, our project may possibly inspire them into a more active participation in society as well. In parallel, through the use of the digital health tools offered by MyPal, HCPs are likely to experience improved communication with patients, more timely and accurate interventions, and an increase in knowledge on effective management of patients with cancer with patients featuring in an empowered role.

The clinical trial reported herein seeks to test the efficacy of the MyPal digital health platform using a newly designed smartphone app together with commonly used wearables to present ePROs to adults with CLL and MDS to determine if it helps communication with their healthcare professionals, compared with standard care. The strengths of this international study include the ability for patients in the intervention arm to spontaneously report on symptoms and concerns, in addition to regular reporting of symptoms when prompted by the app. In addition, this study will provide an opportunity to examine both the advantages and challenges of the MyPal system from the perspectives of the participating healthcare professionals and to assess the extent to which ePRO reporting can facilitate more effective and timely communication, and ultimately benefit patients by improvements in symptom management.

In summary, data from MyPal will be used to (1) identify QoL improvements compared with usual care, (2) provide evidence of improvements in physical and emotional functioning compared with usual care, and (3) give acceptability and usefulness of the MyPal digital health platform for HCPs. We anticipate being able to disseminate our findings by 2023.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

MyPal is coordinated by Dr Kostas Stamatopoulos of the Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece. Other partners are: Fraunhofer Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Germany; Foundation for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece; International Observatory on End of Life Care, Lancaster University, UK; Central European Institute of Technology, Masaryk University, Czech Republic; Karolinska Institute, Sweden; Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Italy; University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece; Hannover Medical School, Germany; University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic; Saarland University, Germany; Promotion Software, Germany; Atlantis Healthcare, UK; European Association for Palliative Care; International Children’s Palliative Care Network; National School of Public Health, Greece. The authors are grateful to the patients who participated into the focus groups, and the clinicians at the clinical study sites who are essential to this study (patient recruitment, symptom assessment and management and data collection). This work is dedicated to Vassilis Koutkias.

Footnotes

Twitter: @julie ling@EAPC_CEO

Contributors: LS, CK, CM, PG and KS designed the study and drafted the study protocol. LS, CK, JD, CPo, CM, PG, SP and KS drafted the manuscript. MD, TG-P, JL, CPa, HΑP, RR, NS and PN contributed to critical revisions of the study protocol and the manuscript. PG, NS, RR, MD and HΑP are the site chief investigators and take overall responsibility for all aspects of the study design, the protocol and the study conduct at the involved clinical study sites.

Funding: MyPal: Fostering Palliative Care of Adults and Children with Cancer through Advanced Patient Reported Outcome Systems is funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union under grant agreement Nr. 825872.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol 2015;90:446–60. 10.1002/ajh.23979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neukirchen J, Schoonen WM, Strupp C, et al. Incidence and prevalence of myelodysplastic syndromes: data from the Düsseldorf MDS-registry. Leuk Res 2011;35:1591–6. 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheffold A, Stilgenbauer S. Revolution of chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapy: the Chemo-Free treatment paradigm. Curr Oncol Rep 2020;22:16. 10.1007/s11912-020-0881-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molica S. Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a neglected issue. Leuk Lymphoma 2005;46:1709–14. 10.1080/10428190500244183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Else M, Smith AG, Cocks K, et al. Patients' experience of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: baseline health-related quality of life results from the LRF CLL4 trial. Br J Haematol 2008;143:690–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steensma DP, Heptinstall KV, Johnson VM, et al. Common troublesome symptoms and their impact on quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): results of a large Internet-based survey. Leuk Res 2008;32:691–8. 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efficace F, Gaidano G, Breccia M, et al. Prevalence, severity and correlates of fatigue in newly diagnosed patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol 2015;168:361–70. 10.1111/bjh.13138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannella L, Caocci G, Jacobs M, et al. Health-Related quality of life and symptom assessment in randomized controlled trials of patients with leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: what have we learned? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;96:542–54. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4249–55. 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluetz PG, Chingos DT, Basch EM. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: measuring symptomatic adverse events with the national cancer institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2016;2016:67–73. 10.1200/EDBK_159514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudgeon D. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcome measures on quality of and access to palliative care. J Palliat Med 2018;21:S-76–S-80. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med 2014;28:158–75. 10.1177/0269216313491619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bausewein C, Daveson B, Benalia H, et al. Outcome measurement in palliative care: the essentials. PRISMA 2011:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening web supplement 2: summary of findings and grade tables. World Health Organization, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright AA, Raman N, Staples P, et al. The hope pilot study: harnessing patient-reported outcomes and biometric data to enhance cancer care. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2018;2:1–12. 10.1200/CCI.17.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire R, Ream E, Richardson A, et al. Development of a novel remote patient monitoring system: the advanced symptom management system for radiotherapy to improve the symptom experience of patients with lung cancer receiving radiotherapy. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:E37–47. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundberg K, Wengström Y, Blomberg K, et al. Early detection and management of symptoms using an interactive smartphone application (Interaktor) during radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:2195–204. 10.1007/s00520-017-3625-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jibb LA, Stevens BJ, Nathan PC, et al. Implementation and preliminary effectiveness of a real-time pain management smartphone APP for adolescents with cancer: a multicenter pilot clinical study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26554. 10.1002/pbc.26554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fayers P, Bottomley A. Quality of life research within the EORTC—the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:125–33. 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00448-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabin R, Gudex C, Selai C, et al. From translation to version management: a history and review of methods for the cultural adaptation of the EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire. Value Health 2014;17:70–6. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: the palliative care outcome scale. palliative care core audit project Advisory group. Qual Health Care 1999;8:219–27. 10.1136/qshc.8.4.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brédart A, Anota A, Young T, et al. Phase III study of the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer satisfaction with cancer care core questionnaire (EORTC PATSAT-C33) and specific complementary outpatient module (EORTC OUT-PATSAT7). Eur J Cancer Care 2018;27:e12786. 10.1111/ecc.12786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. The Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAs): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6–9. 10.1177/082585979100700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap 1994;23:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell AJ, Baker-Glenn EA, Granger L, et al. Can the distress thermometer be improved by additional mood domains? Part I. Initial validation of the emotion thermometers tool. Psychooncology 2010;19:125–33. 10.1002/pon.1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Efird J. Blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:15–20. 10.3390/ijerph8010015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavoukian A. Privacy by design: the 7 foundational principles. information and privacy commissioner of Ontario, Canada, 2009. Available: https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/resources/7foundationalprinciples.pdf

- 28.Regulation P. regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European parliament and of the council. Regulation (EU), 2016. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

- 29.Ernst J, Kuhnt S, Schwarzer A, et al. The desire for shared decision making among patients with solid and hematological cancer. Psychooncology 2011;20:186–93. 10.1002/pon.1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne S, Tanner M, Hughes S. Digitisation and the patient–professional relationship in palliative care 2020:441–3. doi:10.1177%2F0269216320911501 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050256supp001.pdf (2.5MB, pdf)