Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous population of adult stem cells, which are multipotent and possess the ability to differentiate/transdifferentiate into mesodermal and nonmesodermal cell lineages. MSCs display broad immunomodulatory properties since they are capable of secreting growth factors and chemotactic cytokines. Safety, accessibility, and isolation from patients without ethical concern make MSCs valuable sources for cell therapy approaches in autoimmune, inflammatory, and degenerative diseases. Many studies have been conducted on the application of MSCs as a new therapy, but it seems that a low percentage of them is related to clinical trials, especially completed clinical trials. Considering the importance of clinical trials to develop this type of therapy as a new treatment, the current paper is aimed at describing characteristics of MSCs and reviewing relevant clinical studies registered on the NIH database during 2016-2020 to discuss recent advances on MSC-based therapeutic approaches being used in different diseases.

1. Introduction

In general, stem cells refer to a population of undifferentiated cells that are potent for proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal [1]. With regard to potency, stem cells belong to one of four types including unipotent, multipotent, pluripotent, and totipotent cells [2]. Stem cells are defined as unipotent if they maintain the ability to just self-renew and can only differentiate into cell types of a single tissue layer. Stem cells are defined as multipotent if they differentiate into several different cell types within a single germ layer. If they differentiate into cell types from all three germ layers, namely, ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm, and functional gametes, they are called pluripotent stem cells [3]. Totipotent stem cells can form all cell types of the adult organism as well as extraembryonic tissues [4, 5]. Based on the origin of the tissue, stem cells are also categorized to embryonic and adult. A new type of stem cells called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has been introduced in recent years [6]. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which are derived from the inner cell mass of the preimplantation blastocysts are defined as pluripotent stem cells [7, 8]. Adult stem cells are present in adult tissues and replenish senescent cells and subsequently regenerate damaged tissues. These cells, including mainly hematopoietic, neural crest-derived, and mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs), are also known as multipotent stem cells [9–12].

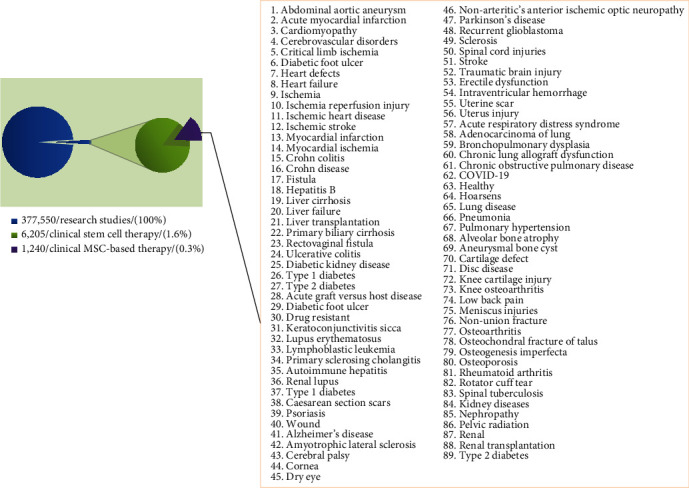

The aforementioned features of stem cells extensively have attracted attention of experts in stem cell biology, developmental biology, biomaterial sciences, tissue engineering, and other relevant fields for restoring damaged cells and tissues to a condition as close to its normal structure and function as possible. In other words, stem cells have developed a new and surprising scenario in regenerative medicine. Nowadays, stem cell therapy not only stands at the forefront of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine but also is increasingly developed in other medical fields such as gene and drug delivery systems [13, 14]. According to the U. S. National Library of Medicine (https://clinicaltrials.gov), a total number of 6205 clinical trials on stem cell therapy worldwide were registered till 5/18/2021. Between them, 1240 of which are related to MSC therapy.

ESCs and MSCs have a number of advantages and disadvantages in their use [15–17]. The reason for this greater tendency to MSCs than other stem cell types can be understood by comparing the advantages and disadvantages of them. Strauer and Kornowski note ESCs as highly expandable and pluripotent but limited by risk of rejection, difficult isolation, risk of malignancy, and ethical objection. They contrast that MSCs are easily obtained, expanded, compatible, and are socially acceptable [15].

Following the discovery of novel treatments for diseases in laboratory and animal models, clinical trials are essential to find treatments that work properly in humans. As abovementioned, the interest of scientists to the MSC-based therapy has increased in recent years. Therefore, the current review paper is aimed at describing characteristics of MSCs and the recent advances on MSC-based therapy.

2. Method

This review is aimed at answering the questions “Which characteristics of MSC has attracted the attention of scientists to apply it as a therapy?”, “How many clinical trials have been reported on the NIH database over a 5-year period of 2016-2020 and how many of them are related to completed and active trials?”, and “For which diseases have no MSC-based therapy clinical trials been reported?”. The clinical trials of MSC therapy were searched through the U. S. National Library of Medicine (https://clinicaltrials.gov) using keywords of “mesenchymal + therapy.” The period of trials was limited to 2016-2020. The result of the search showed 1240 trials. The criteria for selecting articles were their status. The completed, active, and recruiting trials were selected. Accordingly, 290 of which were selected to summarize their available data in Tables 1–3. Data summarized in Table 4 were obtained by searching key words of “mesenchymal+ therapy” and omitting diseases listed in Tables 1–3 through the PubMed database. The purpose of presenting Table 4 was to find conditions that have been treated in preclinical experiments with MSCs but are yet to be translated into clinical trials.

Table 1.

Completed clinical trials on mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapy during 2016-2020 (U. S. National Library of Medicine).

| Organ system | Disease/syndrome | Phase | Date | Country | Source | Transplantation | CT code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Cardiomyopathy | 1 | 2019 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT02509156 |

| Cardiovascular | Graft versus host disease | 1 and 2 | 2016 | Pakistan | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02824653 |

| Cardiovascular | Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02501811 |

| Gastrointestinal | Cirrhosis | 4 | 2020 | India | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04243681 |

| Gastrointestinal | Xerostomia | 2 | 2017 | Denmark | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02513238 |

| Gastrointestinal | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Vietnam | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03343782 |

| Immune | Discordant immunological response in HIV | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Spain | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT02290041 |

| Immune | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 | 2018 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03171194 |

| Integumentary | Atopic dermatitis | 1 | 2017 | Korea | ND | Autotransplant | NCT02888704 |

| Integumentary | Caesarean section scars | 2 | 2018 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02772289 |

| Integumentary | Chronic ulcer | 1 | 2020 | Indonesia | Conditioned medium Wharton's jelly |

Allotransplant | NCT04134676 |

| Integumentary | Chronic venous ulcer | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Germany | Skin | Allotransplant | NCT03257098 |

| Integumentary | Diabetic foot ulcer | 2 | 2016 | Korea | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT02619877 |

| Integumentary | Diabetic neuropathic ulcer | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Germany | Skin | Allotransplant | NCT03267784 |

| Integumentary | Gingival recession | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Belarus | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04434794 |

| Integumentary | Perianal fistula | 1 | 2019 | United States | ND | Autotransplant | NCT02589119 |

| Integumentary | Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04520022 |

| Integumentary | Rectovaginal fistula | 1 | 2019 | Russia | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03643614 |

| Integumentary | Skin scar | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Poland | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03887208 |

| Integumentary | Skin wound | 1 | 2019 | Pakistan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04219657 |

| Integumentary | Surgical leak fistula | 1 | 2019 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02807389 |

| Integumentary | Ultrafiltration failure | 1 and 2 | 2017 | Iran | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT02801890 |

| Nervous | Alzheimer's disease | 1 and2 | 2019 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03117738 |

| Nervous | Brain death | 1 | 2020 | India | ND | ND | NCT02742857 |

| Nervous | Cerebral infarction | 1 and 2 | 2017 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02378974 |

| Nervous | Corneal ulcer Corneal disease Corneal dystrophy |

1&2 | 2019 | Belarus | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04484402 |

| Nervous | Motor neuron disease | 1 | 2016 | Brazil | ND | Autotransplant | NCT02987413 |

| Nervous | Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 2019 | Canada | ND | Autotransplant | NCT02239393 |

| Nervous | Multiple sclerosis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Jordan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03326505 |

| Nervous | Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 2018 | Israel | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02166021 |

| Nervous | Multiple sclerosis | 1 and2 | 2017 | Spain | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02495766 |

| Nervous | Ocular corneal burn | 2 | 2017 | China | Bone marrow | ND | NCT02325843 |

| Nervous | Parkinson's disease | 1 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02611167 |

| Nervous | Refractory epilepsy | 1 | 2019 | Russia | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03676569 |

| Nervous | Retinitis pigmentosa | 3 | 2019 | Turkey | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT04224207 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Jordan | Bone marrow Adipose tissue |

Autotransplant | NCT02981576 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02481440 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 2 | 2017 | Spain | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02570932 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injury | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Spain | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03003364 |

| Reproductive | Atrophic endometrium | 2 | 2019 | Russia | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03166189 |

| Reproductive | Erectile dysfunction | 1 | 2018 | Korea | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02344849 |

| Reproductive | Erectile dysfunction | 1 | 2018 | Jordan | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT02945449 |

| Reproductive | Erectile dysfunction | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Jordan | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03751735 |

| Reproductive | Fistula vagina | 1 | 2020 | United States | ND | Autotransplant | NCT03220243 |

| Reproductive | Ovarian cancer | 1 | 2019 | United States | ND | Autotransplant | NCT02530047 |

| Reproductive | Premature ovarian failure | 1 and 2 | 2018 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02644447 |

| Respiratory | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02804945 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 and 2 | 2016 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02381366 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04355728 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 Prophylaxis |

1 | 2020 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04573270 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04288102 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | China | Exosome Adipose tissue |

Allotransplant | NCT04276987 |

| Respiratory | Laryngotracheal stenosis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Belarus | Olfactory mucosa | Autotransplant | NCT03130374 |

| Respiratory | Noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis | 1 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02625246 |

| Respiratory | Pneumoconiosis | 1 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02668068 |

| Skeletal | Bone fracture | 1 and 2 | 2020 | India | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04340284 |

| Skeletal | Dental implant therapy | 1 and 2 | 2017 | Greece | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03070275 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 2 | 2018 | United States | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02958267 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Canada | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02351011 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 2 | 2018 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02674399 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 1 | 2018 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT02641860 |

| Skeletal | Osteonecrosis | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Spain | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT01605383 |

| Skeletal | Osteoporosis Spinal fractures |

1 | 2016 | Spain | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02566655 |

| Skeletal | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 2018 | Iran | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03333681 |

| Skeletal | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03691909 |

| Urinary | Stress urinary incontinence | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Belarus | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04446884 |

| Urinary | Stress urinary incontinence | 3 | 2016 | Egypt | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02334878 |

ND: no data.

Table 2.

Active clinical trials on mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-based therapy started during 2016-2020 (U. S. National Library of Medicine).

| Organ system | Disease/syndrome | Phase | Date | Country | Source | Transplantation | CT code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 1 and 2 | 2018 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03525418 |

| Gastrointestinal | Cystic fibrosis | 1 | 2016 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02866721 |

| Gastrointestinal | Diabetes | 1 and 2 | 2017 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT02886884 |

| Gastrointestinal | Inflammatory bowel | 1 and 2 | 2017 | Jordan | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03299413 |

| Gastrointestinal | Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 1 and 2 | 2017 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03516006 |

| Gastrointestinal | Xerostomia | 1 | 2019 | Denmark | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT03874572 |

| Immune | Graft versus host disease | 1 and 2 | 2016 | Spain | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02687646 |

| Immune | Graft versus host disease | 1 | 2018 | United States | Umbilical cord Wharton's jelly |

Allotransplant | NCT03158896 |

| Integumentary | Epidermolysis bullosa | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Spain | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04153630 |

| Integumentary | Epidermolysis bullosa | 1 and 2 | 2019 | United Kingdom | Skin | Allotransplant | NCT03529877 |

| Integumentary | Inflammation | 1 and 2 | 2018 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03059355 |

| Integumentary | Psoriasis | 1 and 2 | 2017 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT03265613 |

| Nervous | Alcoholism | 1 and 2 | 2018 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT03265808 |

| Nervous | Alzheimer's disease | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04228666 |

| Nervous | Alzheimer's disease | 1 | 2016 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02600130 |

| Nervous | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 3 | 2017 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03280056 |

| Nervous | Cerebral palsy | 1 and 2 | 2016 | Jordan | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03078621 |

| Nervous | Cerebral palsy | 2 | 2017 | Iran | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03795974 |

| Nervous | Cerebral palsy | 1 and 2 | 2018 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03473301 |

| Nervous | Huntington disease | 2 | 2018 | Brazil | Dental pulp | Allotransplant | NCT03252535 |

| Nervous | Huntington disease | 1 | 2017 | Brazil | Dental pulp | Allotransplant | NCT02728115 |

| Nervous | Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 2018 | United States | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03355365 |

| Nervous | Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 2019 | United States | ND | Autotransplant | NCT03799718 |

| Nervous | Multiple system atrophy | 1 | 2018 | Korea | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04495582 |

| Nervous | Nervous injury | 1 and 2 | 2017 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03291366 |

| Nervous | Parkinson's disease | 2 | 2017 | Belarus | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04146519 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injury | 1 | 2017 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03308565 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Spain | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04366323 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04362189 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04349631 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | France | Umbilical cord Wharton's jelly |

Allotransplant | NCT04333368 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2019 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04043819 |

| Skeletal | Lateral epicondylitis | 2 | 2018 | Korea | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT03449082 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 2 | 2017 | Korea | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03509025 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 3 | 2019 | Korea | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03990805 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 1 | 2016 | Jordan | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03067870 |

| Urinary | Fistula | 1 | 2017 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02808208 |

| Urinary | Kidney injury | 1 and 2 | 2017 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03015623 |

| Urinary | Nephrosis | 2 | 2016 | China | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02966717 |

ND: no data.

Table 3.

Recruiting clinical trials on mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-based therapy started during 2016-2020 (U. S. National Library of Medicine).

| Organ system | Disease/syndrome | Phase | Date | Country | Source | Transplantation | CT code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 1 | 2016 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT02846883 |

| Cardiovascular | Acute myocardial infarction | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Indonesia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04340609 |

| Cardiovascular | Acute myocardial infarction | 1 | 2019 | Taiwan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04056819 |

| Cardiovascular | Cardiomyopathy | 1 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02962661 |

| Cardiovascular | Cerebrovascular disorders | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Iran | Exosome | Allotransplant | NCT03384433 |

| Cardiovascular | Critical limb ischemia | 1 | 2020 | Korea | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04661644 |

| Cardiovascular | Critical limb ischemia | 2 | 2020 | France | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03968198 |

| Cardiovascular | Diabetic foot ulcer | 3 | 2020 | Korea | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04569409 |

| Cardiovascular | Diabetic foot ulcer | 1 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04464213 |

| Cardiovascular | Heart defects | 1 and 2 | 2017 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT03079401 |

| Cardiovascular | Heart failure | 1 | 2016 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02408432 |

| Cardiovascular | Heart failure | 2 and 3 | 2018 | Poland | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03418233 |

| Cardiovascular | Ischemia | 1 | 2017 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02685098 |

| Cardiovascular | Ischemia reperfusion injury | 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04388761 |

| Cardiovascular | Ischemic heart disease | 1 and 2 | 2018 | China | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03397095 |

| Cardiovascular | Ischemic stroke | 1 | 2020 | Taiwan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04434768 |

| Cardiovascular | Ischemic stroke | 1 | 2019 | Taiwan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04097652 |

| Cardiovascular | Myocardial infarction | 1 | 2019 | Spain | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03798353 |

| Cardiovascular | Myocardial infarction | 2 and 3 | 2017 | Poland | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03404063 |

| Cardiovascular | Myocardial ischemia | 2 | 2016 | France | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT02462330 |

| Digestive | Crohn colitis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04548583 |

| Digestive | Crohn disease | 1 | 2018 | United States | ND | Autotransplant | NCT03449069 |

| Digestive | Crohn disease | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Belgium | ND | ND | NCT03901235 |

| Digestive | Fistula | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04519671 |

| Digestive | Fistula | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04519684 |

| Digestive | Hepatitis B | 1 | 2018 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03826433 |

| Digestive | Liver cirrhosis | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Singapore | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03626090 |

| Digestive | Liver cirrhosis | 2 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03945487 |

| Digestive | Liver cirrhosis | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Indonesia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04357600 |

| Digestive | Liver failure | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Germany | Skin | Allotransplant | NCT03860155 |

| Digestive | Liver transplantation | 1 | 2017 | Germany | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02957552 |

| Digestive | Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Vietnam | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04522869 |

| Digestive | Rectovaginal fistula | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04519697 |

| Digestive | Ulcerative colitis | 1 and 2 | 2018 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT03609905 |

| Digestive | Ulcerative colitis | 1 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04312113 |

| Digestive | Ulcerative colitis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04543994 |

| Endocrine | Diabetic kidney disease | 1 | 2019 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03840343 |

| Endocrine | Type 1 diabetes | 1 | 2017 | Jordan | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT02940418 |

| Endocrine | Type 1 diabetes | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Sweden | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03973827 |

| Endocrine | Type 2 diabetes | 1 and 2 | 2016 | Indonesia | Bone marrow Umbilical cord |

Autotransplant Allotransplant |

NCT04501341 |

| Endocrine | Type 2 diabetes | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04441658 |

| Immune | Acute graft versus host disease | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Malaysia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03847844 |

| Immune | Diabetic foot ulcer | 1 | 2019 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04104451 |

| Immune | Drug resistant | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04544215 |

| Immune | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca | 2 | 2020 | Denmark | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04615455 |

| Immune | Lupus erythematosus | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Belarus | Olfactory mucosa | Allotransplant | NCT04184258 |

| Immune | Lymphoblastic leukemia | 2 | 2017 | United States | Umbilical cord | Autotransplant | NCT03096782 |

| Immune | Primary sclerosing cholangitis Autoimmune hepatitis |

1 and 2 | 2018 | United Kingdom | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02997878 |

| Immune | Renal lupus | 2 | 2019 | Chile | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03917797 |

| Immune | Type 1 diabetes | 1 | 2020 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04061746 |

| Immune | Type 1 diabetes | 1 and 2 | 2017 | Sweden | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03406585 |

| Integumentary | Caesarean section scars | 2 | 2020 | China | Perinatal tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04034615 |

| Integumentary | Psoriasis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT03392311 |

| Integumentary | Wound | 1 | 2019 | China | ND Conditioned medium |

ND | NCT04235296 |

| Nervous | Alzheimer's disease | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04388982 |

| Nervous | Alzheimer's disease | 1 | 2019 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04040348 |

| Nervous | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 2 | 2017 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03268603 |

| Nervous | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Poland | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT04651855 |

| Nervous | Cerebral palsy | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Indonesia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04314687 |

| Nervous | Cornea | 1 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04626583 |

| Nervous | Dry eye | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord Exosome |

Allotransplant | NCT04213248 |

| Nervous | Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy | 2 | 2018 | Spain | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03173638 |

| Nervous | Parkinson's disease | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Jordan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03684122 |

| Nervous | Parkinson's disease | 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04506073 |

| Nervous | Recurrent glioblastoma | 1 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03896568 |

| Nervous | Sclerosis | 1 | 2016 | Jordan | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03069170 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 1 and 2 | 2016 | Spain | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT02917291 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04520373 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 1 | 2017 | Jordan | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04288934 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 2 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03521336 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 2 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03521323 |

| Nervous | Spinal cord injuries | 2 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03505034 |

| Nervous | Stroke | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Netherlands | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03356821 |

| Nervous | Traumatic brain injury | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04063215 |

| Reproductive | Erectile dysfunction | 2 | 2020 | Korea | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04594850 |

| Reproductive | Intraventricular hemorrhage | 2 | 2017 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02890953 |

| Reproductive | Uterine scar | 1 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03181087 |

| Reproductive | Uterine scar | 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT02968459 |

| Reproductive | Uterus injury | 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03386708 |

| Respiratory | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Spain | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04289194 |

| Respiratory | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 2 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03818854 |

| Respiratory | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04524962 |

| Respiratory | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 1 and 2 | 2019 | United Kingdom | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03042143 |

| Respiratory | Adenocarcinoma of lung | 1 and 2 | 2019 | United Kingdom | ND | Allotransplant | NCT03298763 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow Exosome |

Allotransplant | NCT03857841 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 2019 | Spain | ND | ND | NCT02443961 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 and 2 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03645525 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 2018 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03873506 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 and 2 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03774537 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 2018 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03558334 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 2 | 2018 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03392467 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 2 | 2019 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04003857 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 2018 | Taiwan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03631420 |

| Respiratory | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 1 | 2019 | Vietnam | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04062136 |

| Respiratory | Chronic lung allograft dysfunction | 2 | 2017 | Australia | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02709343 |

| Respiratory | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | 2020 | United States | ND | ND | NCT04047810 |

| Respiratory | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Vietnam | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04433104 |

| Respiratory | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | 2020 | Taiwan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04206007 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Mexico | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04611256 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Belgium | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04445454 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Canada | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04400032 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Pakistan | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04444271 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Spain | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04361942 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Sweden | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04447833 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04397796 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 3 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04371393 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04629105 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | United States | Cord blood | Allotransplant | NCT04565665 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT04399889 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Dental pulp | Allotransplant | NCT04336254 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Indonesia | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04535856 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Mexico | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04416139 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Spain | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04615429 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04466098 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Brazil | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04525378 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 and 3 | 2020 | Iran | ND Exosome |

ND | NCT04366063 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT04524962 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Ukraine | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04461925 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Germany Israel |

Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04614025 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04389450 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04339660 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Indonesia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04457609 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Spain | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04366271 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04494386 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 2 | 2020 | Pakistan | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04437823 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04252118 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Turkey | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04392778 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 | 2020 | Jordan | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT04313322 |

| Respiratory | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Spain | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT04390139 |

| Respiratory | Healthy | 1 | 2020 | China | Adipose tissue exosome | Allotransplant | NCT04313647 |

| Respiratory | Hoarseness | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Sweden | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04290182 |

| Respiratory | Lung disease | 1 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT03929120 |

| Respiratory | Pneumonia | 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04269525 |

| Respiratory | Pulmonary hypertension | 1 and 2 | 2019 | China | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04055415 |

| Skeletal | Alveolar bone atrophy | 3 | 2020 | Spain | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT04297813 |

| Skeletal | Aneurysmal bone cyst | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Jordan | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03066245 |

| Skeletal | Cartilage defect | 1 | 2018 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant Allotransplant |

NCT03672825 |

| Skeletal | Disc disease | 2 | 2017 | Indonesia | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04499105 |

| Skeletal | Disc disease | 1 | 2019 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04104412 |

| Skeletal | Knee cartilage injury | 1 and 2 | 2018 | China | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03955497 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 2 | 2020 | China | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04208646 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Taiwan | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT03943576 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Poland | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03869229 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2017 | Jordan | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02966951 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Ukraine | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04453111 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Korea | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04240873 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2018 | United States | Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03477942 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2019 | Chile | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03810521 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2019 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04037345 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2020 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04339504 |

| Skeletal | Knee osteoarthritis | 1 | 2017 | Jordan | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT02963727 |

| Skeletal | Low back pain | 1 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04410731 |

| Skeletal | Meniscus injuries | 2 | 2019 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT04274543 |

| Skeletal | Nonunion fracture | 3 | 2017 | France Germany |

Bone marrow | Autotransplant | NCT03325504 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 2 | 2016 | France | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02838069 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 1 | 2016 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT02805855 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 1 | 2018 | United States | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03608579 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 3 | 2019 | United States | Bone marrow Adipose tissue |

Autotransplant | NCT03818737 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03383081 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2020 | Indonesia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04314661 |

| Skeletal | Osteoarthritis | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Poland | Wharton's jelly | Allotransplant | NCT03866330 |

| Skeletal | Osteochondral fracture of talus | 3 | 2019 | Chile | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03905824 |

| Skeletal | Osteogenesis imperfecta | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Sweden | Fetal liver | Allotransplant | NCT03706482 |

| Skeletal | Osteoporosis | 2 | 2020 | Indonesia | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04501354 |

| Skeletal | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 2017 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT03186417 |

| Skeletal | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 and 2 | 2018 | Korea | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT03618784 |

| Skeletal | Rotator cuff tear | 2 | 2020 | Brazil | ND | ND | NCT03362424 |

| Skeletal | Spinal tuberculosis | 2 | 2017 | Indonesia | ND | ND | NCT04493918 |

| Urinary | COVID-19 | 1 and 2 | 2020 | United States | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT04445220 |

| Urinary | Kidney diseases | 1 and 2 | 2019 | Bangladesh | Adipose tissue | Autotransplant | NCT03939741 |

| Urinary | Kidney diseases | 1 and 2 | 2017 | Ireland Italy United Kingdom |

Bone marrow | Allotransplant | NCT02585622 |

| Urinary | Nephropathy | 1 | 2020 | Japan | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04342325 |

| Urinary | Pelvic radiation | 2 | 2019 | France | ND | ND | NCT02814864 |

| Urinary | Renal | 1 | 2020 | United States | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | NCT04392206 |

| Urinary | Renal transplantation | 1 | 2018 | United States | ND | Allotransplant | NCT03504241 |

| Urinary | Renal transplantation | 2 | 2016 | United States | ND | Autotransplant | NCT03478215 |

| Urinary | Type 2 diabetes | 1 and 2 | 2020 | China | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | NCT04216849 |

ND: no data.

Table 4.

Diseases can be tested clinically for treatment with mesenchymal stromal/stem cells in human based on the successful in vivo model studies.

| Organ system | Disease/syndrome | Source | Transplantation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Myelodysplastic syndromes | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | [114] |

| Gastrointestinal | Hepatic failure | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | [115] |

| Nervous | Epilepticus | Exosome | Allotransplant | [117] |

| Nervous | Glioblastoma | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | [118] |

| Nervous | Glioblastoma | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | [119] |

| Nervous | Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy | Umbilical cord | Allotransplant | [120] |

| Nervous | Loss of retinal ganglion cells | Bone marrow-derived exosomes | Allotransplant | [121] |

| Nervous | Nerve regeneration | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | [122] |

| Reproductive | Azoospermia | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | [123] |

| Reproductive | Azoospermia | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | [124] |

| Reproductive | Mammary adenocarcinoma | Adipose tissue | Allotransplant | [116] |

| Skeletal | Bone formation | ND | Allotransplant | [125] |

| Skeletal | Calvarial defects | Bone marrow Adipose tissue |

Allotransplant | [126] |

| Skeletal | Periodontal defects | Exosome | Allotransplant | [127] |

| Urinary | Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | Bone marrow | Allotransplant | [128] |

| Urinary | Nephron generation in kidney cortices | ND | Allotransplant | [129] |

ND: no data.

3. MSCs

Friedenstein et al. first described MSCs as a population of fibroblast-like cells in the bone marrow [18]. According to the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) definition, to be classified as MSCs, the cells must satisfy four minimal criteria: (i) specific surface antigen expression (>95%) including CD73, CD90, CD105, CD44, CD71, Stro-1, CD106, CD166, CD29, and ICAM-1, (ii) do not express hematopoietic markers (CD45, CD34, CD14, and CD11), endothelial (CD31), and costimulatory markers (CD80, CD86), (iii) adherence to the plastic plate surface, and (iv) capability to differentiate into osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages [19].

Some studies have demonstrated that MSCs are able to transdifferentiate into nonmesenchymal cells (hepatic, renal, cardiac, neural, and Schwann cells) [20–25]. These cells express pluripotency-associated factors including OCT-4, SOX-2, and NANOG [26]. However, their expression depends on the type of MSCs and their niche [27]. The niche of MSCs is the subject of much debate and has not been fully understood yet. Nonetheless, three factors may play a critical role in the residing of MSCs: (i) expression of the receptors and adhesion molecules in MSCs [28], (ii) interaction with endothelial cells [29], and (iii) expression of signalling molecules from injured tissue [30]. However, factors such as delivery method, the age of MSCs, passage number, the population of MSCs, and the source and culture condition of MSCs can alter their residing efficacy [31].

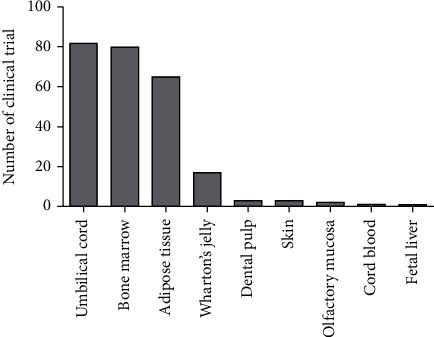

4. Cell Sources of MSCs

MSCs can be easily isolated from several tissues and can be effectively cultured in vitro. As the major sources of MSCs in clinic trials are umbilical cord, bone marrow, and adipose tissues, MSCs derived from these tissues are discussed below (Figure 1). Adult bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) comprise only 0.01% to 0.001% of the bone marrow cell population and can be isolated from osseous biopsies [32, 33]. BM-MSCs are multipotent and capable of differentiating into mesodermal, ectodermal, and endodermal cell lineages. Previous studies have reported that BM-MSCs are a potential source of stem cells with capability in differentiation into male germ cells [34]. It is also shown that these possess high proliferation rate and their immunomodulatory properties act through paracrine mechanisms [35–39]. Accordingly, BM-MSCs can be useful for solving some genetic and immunological problems as well as repairing damaged tissues [40]. Moreover, it has been proved that BM-MSCs secrete cytokines and growth factors and can facilitate engraftment in organs [41–43]. Adipose tissues can be considered as a suitable source for MSCs, as its harvesting is relatively noninvasive. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells (AT-MSCs) can be extracted by liposuction and isolated from the stromal vascular fraction of homogenized adipose tissues [44, 45]. These cells were first identified as MSCs by Zuk and colleagues in 2001 [46]. AT-MSCs can be isolated in high numbers, because of their abundance in the human body [47]. They express MSC markers (CD90, CD44, CD29, CD105, CD13, CD34, CD73, CD166, CD10, CD49e, and CD59) while hematopoietic and endothelial markers (CD31, CD45, CD14, CD11b, CD34, CD19, CD56, and CD146) are downregulated in this cell population [48]. More genetic and morphologic stability in long-term cultures, higher proliferation, and other characteristics give AT-MSCs a distinct advantage over BM-MSCs [49, 50]. However, their proliferation rate depends on various factors such as donor's age, fat tissue type (white or brown), location of the harvest (subcutaneous or visceral), culture conditions, cell culture density, and media formulation [51]. The human umbilical cord is a conduit between the developing embryo/fetus and the placenta. It contains two arteries and a vein surrounded by mucosa connective tissue called Wharton's jelly [52]. The umbilical cord has five various compartments including amniotic epithelium membrane, cord lining, intervascular Wharton's jelly, and perivascular and mixed cord. There is also a population of stem cells called umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) that can be isolated from the umbilical cord. Human UC-MSCs draw attention since they are derived from a noncontroversial source, and there are no ethical concerns in harvesting and using them for treatment purposes. Human UC-MSCs are more potent possessing more proliferation potential and differentiation capacity compared to adult tissue-derived MSCs. MSCs population in Wharton's jelly is higher than the other parts of the umbilical cord [53]. In 1991, McElreavey et al. [54] isolated fibroblast-like cells from Wharton's jelly of the human umbilical cord for the first time. Wharton's jelly-derived MSCs (WJ-MSCs) express high level of MSC markers as well as some pluripotency markers [55].

Figure 1.

Frequency of mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC) source contributions in clinical trials on MSC therapy during 2016-2020 (U. S. National Library of Medicine).

5. Therapeutic Application of MSCs

Different types of MSC-based therapy have been studied and discussed for treating of a wide range of diseases such as graft-versus-host-disease [56–58], Crohn's disease [59, 60], type 1 diabetes [61, 62], multiple sclerosis (MS) [63, 64], lupus [65, 66], cardiovascular diseases [67, 68], liver disorders [69], respiratory disorders [70, 71], spinal cord injury [72, 73], kidney failure [74, 75], skin diseases [76, 77], Alzheimer's disease [78], and Parkinson disease [79].

6. Therapeutic Mechanisms of MSCs

Diverse therapeutic mechanisms have been suggested for MSCs. Exploring these mechanisms are essential to help scientist to select the suitable dosage, administration route, and best engraftment time of MSCs [85]. Several mechanisms can be involved in the therapeutic effects of MSCs on a specific disease, as described below.

The therapeutic potential of MSCs can be attributed to their secretory and immunomodulatory properties. Immunomodulatory responses are dependent on the cell-to-cell interaction mechanisms and releasing secretory factors [80, 81]. MSCs secrete a wide range of bioactive molecules including growth and antiapoptotic factors including VEGF, HGF, IGF-1, TGF-β, bFGF, and stanniocalcin-1 [82]. MSC-derived secretory factors induce cell proliferation and angiogenesis and limit the injury site. When the tissue is injured, molecules such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-12, TNF-α, and INF-γ produce inflammatory responses at the injury site [83]. This response prevents the regenerating process by progenitor stem cells [83]. The secretion of PGE-2, iNOS, iDO, HLA-G5, and LIF from MSCs leads to reduced inflammation and subsequent regulation of immune system cells' function [84].

Homing is a feature of MSCs referring to their tendency to home to injured tissues. This ability in MSCs, which was first identified by Saito et al. [86], is effective in treating diseases. Moreover, homing of MSCs to damaged tissues following transplantation suggests them as very promising drug carriers. MSC homing can be affected by several factors including the transplantation time and quantity, pretreatment, the method of culture, and the transplantation approach of MSCs [87, 88].

Another possible therapeutic mechanism is the differentiation of MSCs. As above-mentioned, these cells have the ability to differentiate into different cells such as adipocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, myoblasts, and neuron-like cells. This ability has resulted in successful application of MSCs in tissue and scaffold engineering [89–91].

Producing trophic factor is another mechanism, as MSCs have ability to play a role as a pool of trophic factor. Following the homing MSCs in injured areas, local stimuli simulate MSCs to secrete growth factors, which have a role in tissue regeneration, angiogenesis, and preventing cell apoptosis [92–94].

7. Approaches for Applying MSCs

In general, eight administration methods have been proposed for applying MSCs. These methods include intravenous injection (IV) [95, 96], intra-arterial injection (IA) [97, 98], intrathecal injection (IT) [99, 100], intracardiac injection (IC) [101], intra-articular injection (IAT) [102, 103], intramuscular injection (IM) [104], intraosseous injection (IO) [105], and implant for cells incorporated into a matrix or an implanted device [106, 107]. According to the study on the clinical trials of MSCs over 2014-2018, the most common administration method used in clinical trials was IV. The next common methods were IT, IAT, IC, IM, and IO in order of applications [107].

8. Clinical Use of MSCs

Although MSCs offer remarkable potentials, which made them a favorable candidate for treating a large number of diseases, an overview on statics obtained from the U. S. National Library of Medicine shows that 6205 out of 377,550 research studies are related to clinical stem cell therapy (1.6%) and only 1240 of which are related to MSC-based therapy (0.3%) (Figure 2). Still, there are several concerns regarding the cell dosage and the proper administration route and timing [108–110] that limit the use of MSCs in clinical practice.

Figure 2.

An overview on statics relating to MSC-based therapy clinical trials obtained from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

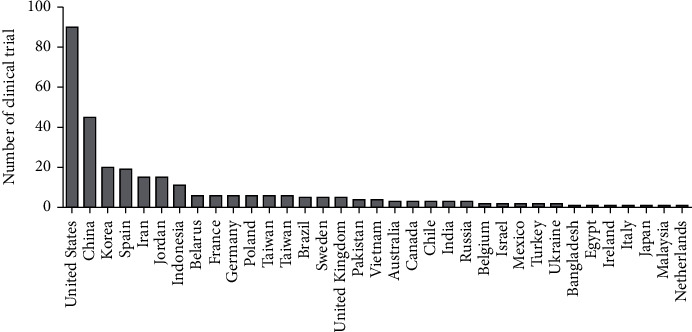

Some completed clinical trials in this field (all phases except early phase 1 and not applicable) over 2016-2020 have been listed in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 show active recruiting clinical trials on MSC therapy during 2016-2020 (U. S. National Library of Medicine). According to this table, the potential of MSCs has been studied in treating numerous diseases including myocardial infarction, diabetes, spinal cord injury, and systemic lupus. Taking an overall view on these three tables, it has been found completed or active clinical tr ials were mostly related to the nervous system diseases while recruiting clinical trials were mostly related to respiratory diseases. In general, respiratory diseases have been mostly attracted researchers worldwide because of the pandemic COVID-19. In addition, the United States is ranked the first in terms of clinical trials on MSC therapy (Figure 3). Five of these studies (NCT01909154, NCT03473301, NCT02013674, NCT02958267, and NCT02509156) whose results were available have been reviewed in terms of morality rate, adverse effects, and successfulness.

Figure 3.

Frequency of country contributions in clinical trials on mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-based therapy during 2016-2020 (U. S. National Library of Medicine).

NCT01909154 conducted on 12 participants to examine the safety and the impact of the local administration of autologous BM-MSCs in damaged nervous tissue. No mortality was reported in this trial. Adverse effect of urinary tract infection (12/12 or 100%), general pain and back pain (4/12 or 33.33%), myalgia and hyperthermia (3/12 or 25.00%), nasopharyngitis, nausea, muscle contracture, and headache (2/12 or 16.67%), and iron deficiency anemia, diarrhea, saline extravasation, local edema, perineal abscess, infectious mononucleosis, subcutaneous seroma, high level of cholesterol in blood, high level of alkaline phosphatase in blood, thoracic pain, intercostal neuralgia, anxiety, urinary discomfort, pressure ulcer, hemorrhoidectomy, hypertension, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension (1/12 or 8.33%) were reported. Applying this therapy on 52 patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) showed that administration of BMSCs is safe and may increase the life quality of patients suffering from SCI [111].

NCT03473301 (A Study of UCB and MSCs in Children With CP) was conducted on a total number of 91 participants in three groups of allogeneic umbilical cord blood (AlloCB, n = 31), cord tissue MSCs (MSC, n = 29), and natural history (n = 31). The mortality rate was reported zero in this trial. Adverse effect including gastritis, bronchitis viral, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus infection, dehydration, hypoacusis, constipation, diarrhoea, vomiting, fatigue, anaphylactic reaction, influenza, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection, infusion related reaction, arthropod bite, tooth avulsion, dehydration, facial paresis, partial seizures, strabismus correction, dental operation, orchidopexy, suture insertion, and tongue tie operation (1/31 or 3.23%), seizure, pyrexia, otitis media, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, and fall, laboratory test abnormal and pyrexia (2/31 or 6.45%), and surgery (3/31 or 9.68%) were observed in the AlloCB group. Upper respiratory tract infection (8/29 or 27.59%), infusion-related reaction, and rash, (4/29 or 13.79%), pyrexia (3/29 or 10.34%), otitis media, rash maculopapular, urticaria, and hospitalisation (2/29 or 6.90%), and tonsillitis, drug hypersensitivity, varicella, fall, disturbance in attention, insomnia, henoch-Schonlein purpura, orchidopexy, adenoidectomy, sleep disorder, anaemia, influenza-like illness, infusion site rash, injection site reaction, and drug hypersensitivity (1/29 or 3.45%) were reported in the MSC group. Seizure (5/31 or 16.13%), strabismus correction, hospitalization, and pyrexia (2/31 or 6.45%), and respiratory tract infection viral, otitis media, fall, fracture, adenotonsillectomy, surgery, thrombocytopenia, bradycardia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bronchitis, and enterocolitis infectious (1/31 or 3.23%) were observed in the natural history group. Hospitalization (2/27 or 7.41%) and bronchitis, enterocolitis infectious, cough, rash, seizure, respiratory failure, cyclic vomiting syndrome, toothache, and pyrexia (1/27 or 3.70%) were observed in AlloCB after natural history. No article has been published using the results of this trial to discuss about the success of this therapy.

The clinical trial NCT02013674 was a phase II study for gaining additional safety and efficacy assessments among two-dose levels previously studied in a phase I setting. Participants included 30 patients suffering from chronic ischemic left ventricular dysfunction secondary to MI scheduled to undergo cardiac catheterization. Two groups of 20 million allogeneic hMSCs (group1, n = 15) and 100 million allogeneic hMSCs (group 2, n = 15) were designed for this trial. The mortality rate was reported 0.00% (0 l15) and 13.33% (1/15) for group 1 and group 2, respectively. Cardiac failure congestive, cardiac failure (6/15 or 60.00%), hematoma, hypotension (2/15 or 13.33%), and sinus arrest, vertigo, vision blurred, fatigue, gait disturbance, pyrexia, hordeolum, rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, fall, dehydration, spinal column ste, headache, pollakiuria, and asthma (1/15 or 6.67%) were reported in group 1. Cardiac failure congestive, hematuria (3/15 or 20.00%), arteriosclerosis, squamous cell carcinoma, dyspnoea (2/15 or 13.33%), eye pruritus, eye swelling, dysphagia, nausea, chest pain, urinary tract infection, prostatic specific antigen, gout, inguinal mass, pain in extremity, prostatitis, breast mass, cough, epistaxis, alopecia, stasis dermatitis, cardioversion, implantable defibrillator replacement, and tooth extraction (1/15 or 13.33%) were observed in group 2. The results of this study showed the effectiveness of both dosages of cells on reduction of scar size. However, only the 100 million dosages enhanced ejection fraction [112]. Investigation of MSC-therapy for treating osteoarthritis of the knee (NCT02958267) was performed on 32 participants in two groups of BMAC injection and PRP injection (n = 17) and Gel-One® hyaluronate injection (n = 15). This clinical trial report a mortality rate of zero for all groups and adverse effects of nausea and vomiting (1/17 or 5.88%) for the BMAC injection and PRP injection groups. No data is available about the success of this therapy.

The purpose of the clinical trial NCT02509156 was to examine the safety, feasibility, and therapeutic efficacy of allogeneic human-MSCs delivered through transendocardial injection to cancer survivors with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction secondary to anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy (AIC). 37 subjects in two groups of Allo-MSCs (n = 20) and placebo (n = 17) were examined in terms of the adverse effect of this trial. A mortality rate of 5.00% and 0% was reported for Allo-MSCs and placebo groups. Serious adverse events including cardiac disorders, sudden cardiac death, procedural pneumothorax, hyperglycaemia, osteoarthritis, transient ischaemic attack, acute kidney injury, and hypotension were reported for the Allo-MSCs group with a total rate of 25.00%. Serious adverse events of cardiac, gastrointestinal, and hepatobiliary disorders, infections and infestations, fall, hyponatraemia, syncope, product issues (lead dislodgement and device lead damage), acute kidney injury, menorrhagia, and hypotension were reported for the placebo group with a total rate of 64.71%. The article published according to the results of this trial does not mention that this therapy is safe or not. The author of this trial stated that if the therapy will be safe and feasible, we will conduct a larger phase II/III trial to examine its therapeutic efficacy [113].

9. Future Prospective

The large number of trials focusing on MSCs therapy shows the importance of this therapy from point of view of scientists, and if these trials will be successful, they will change human life positively. Despite the increasing rate of development in MSCs therapy, it has not been commonly used by clinicians because of challenges such as the timing and optimum dosage of MSC administration. There are some conditions that have been treated in preclinical experiments with MSCs but are yet to be translated into clinical trials. Some of these disorders are epilepticus, glioblastoma, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, loss of retinal ganglion cells, nerve regeneration, azoospermia, and nephron generation in kidney cortices (Table 4). Therefore, it is encouraged to study the possibility of clinical trials of MSC therapy for such disease in the future. The potential of MSCs brings to mind the idea that the medicine of tomorrow can treat some of the incurable diseases including those related to aging.

Acknowledgments

This study has been financially supported by the Allame Tabatabaei Post-Doc Fellowship Program from Iran's National Elites Foundation (INEF).

Contributor Information

Reza Shirazi, Email: rshirazi@swin.edu.au.

Amin Tamadon, Email: amintamaddon@yahoo.com.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Disclosure

The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

R.S., A. T., and I. N. conceived and designed the format of the manuscript. M. R. K., N. B., S. F. M., M. B., V. N., Z. S., and A. K. collected the data and drafted and edited the manuscript. N. B., R. S., and A. T. drew the figures and tables. All the authors reviewed the manuscript, and all of them contributed to the critical reading and discussion of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Mohammad Reza Kouchakian, Neda Baghban, Seyedeh Farzaneh Moniri, and Mandana Baghban contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Mendonca L. S., Onofre I., Miranda C. O., Perfeito R., Nobrega C., de Almeida L. P. Stem cell-based therapies for polyglutamine diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology . 2018;1049:439–466. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71779-1_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabansky I., Stern J. N. Basics of stem cell biology as applied to the brain. Stem Cells in Neuroendocrinology. . 2016:11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobhani A., Khanlarkhani N., Baazm M., et al. Multipotent stem cell and current application. Acta Medica Iranica . 2017;55:6–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahla R. S. Stem cells applications in regenerative medicine and disease therapeutics. International journal of cell biology . 2016;2016:24. doi: 10.1155/2016/6940283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosseinkhani M., Shirazi R., Rajaei F., Mahmoudi M., Mohammadi N., Abbasi M. Engineering of the embryonic and adult stem cell niches. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal . 2013;15:83–92. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamanaka S. Induced pluripotent stem cells: past, present, and future. Cell stem cell . 2012;10(6):678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yachie‐Kinoshita A., Onishi K., Ostblom J., et al. Modeling signaling‐dependent pluripotency with Boolean logic to predict cell fate transitions. Molecular systems biology . 2018;14(1, article e7952) doi: 10.15252/msb.20177952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva M. C., Haggarty S. J. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived models and drug screening in CNS precision medicine. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences . 2019 doi: 10.1111/nyas.14012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lengler J., Bittner T., Munster D., Gawad Ael D., Graw J. Agonistic and antagonistic action of AP2, Msx2, Pax6, Prox1 AND Six3 in the regulation of Sox2 expression. Ophthalmic Research . 2005;37:301–309. doi: 10.1159/000087774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greco S. J., Liu K., Rameshwar P. Functional similarities among genes regulated by OCT4 in human mesenchymal and embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells . 2007;25:3143–3154. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matic I., Antunovic M., Brkic S., et al. Expression of OCT-4 and SOX-2 in bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells during osteogenic differentiation. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences . 2016;4:9–16. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2016.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han S. M., Han S. H., Coh Y. R., et al. Enhanced proliferation and differentiation of Oct4- and Sox2-overexpressing human adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells. Experimental & Molecular Medicine . 2014;46, article e101 doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altanerova U., Jakubechova J., Benejova K., et al. Prodrug suicide gene therapy for cancer targeted intracellular by mesenchymal stem cell exosomes. International Journal of Cancer . 2019;144:897–908. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu H.-H., Zhou Y., Tabata Y., Gao J.-Q. Mesenchymal stem cell-based drug delivery strategy: from cells to biomimetic. Journal of Controlled Release . 2019;294:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauer B. E., Kornowski R. Stem cell therapy in perspective. Circulation . 2003;107:929–934. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057525.13182.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segers V. F., Lee R. T. Stem-cell therapy for cardiac disease. Nature . 2008;451:937–942. doi: 10.1038/nature06800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herberts C. A., Kwa M. S., Hermsen H. P. Risk factors in the development of stem cell therapy. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2011;9:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedenstein A. J., Chailakhjan R. K., Lalykina K. S. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell and Tissue Kinetics . 1970;3:393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1970.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominici M., Le Blanc K., Mueller I., et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy . 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhadlaq A., Mao J. J. Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation and therapeutics. Stem Cells and Development . 2004;13:436–448. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashani I. R., Golipoor Z., Akbari M., et al. Schwann-like cell differentiation from rat bone marrow stem cells. Archives of Medical Science . 2011;7:45–52. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.20603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong S.-Y., Dai H., Leong K. W. Inducing hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in pellet culture. Biomaterials . 2006;27:4087–4097. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li K., Han Q., Yan X., Liao L., Zhao R. C. Not a process of simple vicariousness, the differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells to renal tubular epithelial cells plays an important role in acute kidney injury repairing. Stem Cells and Development . 2010;19:1267–1275. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatzistergos K. E., Quevedo H., Oskouei B. N., et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Circulation Research . 2010;107:913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Y., Zeng Y.-M., Wan M.-R., Lu X.-F. Induction of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into neural-like cells using cerebrospinal fluid. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics . 2011;59:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s12013-010-9130-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai C. C., Hung S. C. Functional roles of pluripotency transcription factors in mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Cycle . 2012;11:3711–3712. doi: 10.4161/cc.22048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heo J. S., Choi Y., Kim H. S., Kim H. O. Comparison of molecular profiles of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, placenta and adipose tissue. International Journal of Molecular Medicine . 2016;37:115–125. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitzsche F., Müller C., Lukomska B., Jolkkonen J., Deten A., Boltze J. Concise review: MSC adhesion cascade—insights into homing and transendothelial migration. Stem Cells . 2017;35:1446–1460. doi: 10.1002/stem.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge Q., Zhang H., Hou J., et al. VEGF secreted by mesenchymal stem cells mediates the differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells into endothelial cells via paracrine mechanisms. Molecular Medicine Reports . 1667-1675;2018:p. 17. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusuma G. D., Carthew J., Lim R., Frith J. E. Effect of the microenvironment on mesenchymal stem cell paracrine signaling: opportunities to engineer the therapeutic effect. Stem Cells and Development . 2017;26:617–631. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohni A., Verfaillie C. M. Mesenchymal stem cells migration homing and tracking. Stem Cells International . 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/130763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittenger M. F., Mackay A. M., Beck S. C., et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science . 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Challen G. A., Boles N., Lin K. Y. K., Goodell M. A. Mouse hematopoietic stem cell identification and analysis. Cytometry Part A: The Journal of the International Society for Advancement of Cytometry . 2009;75:14–24. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghasemzadeh-Hasankolai M., Batavani R., Eslaminejad M. B., Sedighi-Gilani M. Effect of zinc ions on differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to male germ cells and some germ cell-specific gene expression in rams. Biological Trace Element Research . 2012;150:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosseinkhani M., Mehrabani D., Karimfar M. H., Bakhtiyari S., Manafi A., Shirazi R. Tissue engineered scaffolds in regenerative medicine. World journal of plastic surgery . 2014;3:3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirazi R., Zarnani A. H., Soleimani M., Nayernia K., Ragerdi Kashani I. Differentiation of bone marrow-derived stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 positive pluripotent stem cells into male germ cells. Microscopy Research and Technique . 2017;80:430–440. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirazi R., Zarnani A. H., Soleimani M., Abdolvahabi M. A., Nayernia K., Ragerdi Kashani I. BMP4 can generate primordial germ cells from bone-marrow-derived pluripotent stem cells. Cell Biology International . 2012;36:1185–1193. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashani I. R., Zarnani A. H., Soleimani M., Abdolvahabi M. A., Nayernia K., Shirazi R. Retinoic acid induces mouse bone marrow-derived CD15(+), Oct4(+) and CXCR4(+) stem cells into male germ-like cells in a two-dimensional cell culture system. Cell Biology International . 2014;38:782–789. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang M., Yuan Q., Xie L. Mesenchymal stem cell-based immunomodulation: properties and clinical application. Stem Cells International . 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3057624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maumus M., Guérit D., Toupet K., Jorgensen C., Noël D. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies in regenerative medicine: applications in rheumatology. Stem Cell Research & Therapy . 2011;2:1–6. doi: 10.1186/scrt55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X., Duan B., Cheng Z., et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 axis modulates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis, migration and cytokine secretion. Protein & Cell . 2011;2:845–854. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traktuev D. O., Merfeld-Clauss S., Li J., et al. A population of multipotent CD34-positive adipose stromal cells share pericyte and mesenchymal surface markers, reside in a periendothelial location, and stabilize endothelial networks. Circulation Research . 2008;102:77–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soleymaninejadian E., Pramanik K., Samadian E. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells: cytokines and factors. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology . 2012;67:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bora P., Majumdar A. S. Adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction in regenerative medicine: a brief review on biology and translation. Stem Cell Research & Therapy . 2017;8:p. 145. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0598-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider S., Unger M., Van Griensven M., Balmayor E. R. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from liposuction and resected fat are feasible sources for regenerative medicine. European Journal of Medical Research . 2017;22:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40001-017-0258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zuk P. A., Zhu M., Mizuno H., et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Engineering . 2001;7:211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuji W., Rubin J. P., Marra K. G. Adipose-derived stem cells: implications in tissue regeneration. World journal of stem cells . 2014;6:312–321. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mildmay-White A., Khan W. Cell surface markers on adipose-derived stem cells: a systematic review. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy . 2017;12:484–492. doi: 10.2174/1574888X11666160429122133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choudhery M. S., Badowski M., Muise A., Pierce J., Harris D. T. Donor age negatively impacts adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion and differentiation. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2014;12:p. 8. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaim M., Karaman S., Cetin G., Isik S. Donor age and long-term culture affect differentiation and proliferation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Annals of Hematology . 2012;91:1175–1186. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchell J. B., McIntosh K., Zvonic S., et al. Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell–associated markers. Stem Cells . 2006;24:376–385. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benirschke K., Burton G. J., Baergen R. N. In Pathology of the Human Placenta . Springer; 2012. Anatomy and pathology of the umbilical cord; pp. 309–375. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conconi M. T., Di Liddo R., Tommasini M., Calore C., Parnigotto P. P. Phenotype and differentiation potential of stromal populations obtained from various zones of human umbilical cord: an overview. The Open Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Journal . 2011;4:6–20. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McElreavey K. D., Irvine A. I., Ennis K. T., McLean W. H. Isolation, culture and characterisation of fibroblast-like cells derived from the Wharton's jelly portion of human umbilical cord. Biochemical Society Transactions . 1991;19:p. 29S. doi: 10.1042/bst019029s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davies J. E., Walker J. T., Keating A. Concise review: Wharton's jelly: the rich, but enigmatic, source of mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells Translational Medicine . 2017;6:1620–1630. doi: 10.1002/sctm.16-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munir H., McGettrick H. M. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for autoimmune disease: risks and rewards. Stem Cells and Development . 2015;24:2091–2100. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Polymeri A., Giannobile W. V., Kaigler D. Bone marrow stromal stem cells in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Hormone and Metabolic Research . 2016;48:700–713. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-118458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muroi K., Miyamura K., Okada M., et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (JR-031) for steroid-refractory grade III or IV acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II/III study. International Journal of Hematology . 2016;103(2):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s12185-015-1915-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dalal J., Gandy K., Domen J. Role of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in Crohn’s disease. Pediatric Research . 2012;71:445–451. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X. M., Zhang Y. J., Wang W., Wei Y. Q., Deng H. X. Mesenchymal stem cells to treat Crohn's disease with fistula. Human Gene Therapy . 2017;28:534–540. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vija L., Farge D., Gautier J.-F., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: stem cell therapy perspectives for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes & Metabolism . 2009;35:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu H., Mahato R. I. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for type 1 diabetes. Discovery Medicine . 2014;17:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karussis D., Karageorgiou C., Vaknin-Dembinsky A., et al. Safety and immunological effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Archives of Neurology . 2010;67:1187–1194. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen J. A. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences . 2013;333:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun L., Wang D., Liang J., et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism . 2010;62:2467–2475. doi: 10.1002/art.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cras A., Farge D., Carmoi T., Lataillade J.-J., Wang D. D., Sun L. Update on mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy in lupus and scleroderma. Arthritis Research & Therapy . 2015;17:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0819-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hare J. M. Translational development of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for cardiovascular diseases. Texas Heart Institute Journal . 2009;36:p. 145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo Y., Yu Y., Hu S., Chen Y., Shen Z. The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death & Disease . 2020;11:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2542-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gazdic M., Arsenijevic A., Markovic B. S., et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-dependent modulation of liver diseases. International Journal of Biological Sciences . 2017;13:p. 1109. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.20240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taghavi-farahabadi M., Mahmoudi M., Soudi S., Hashemi S. M. Hypothesis for the management and treatment of the COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome and lung injury using mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Medical Hypotheses . 2020;109865 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu H., Xiong Y., Xia Y., et al. Therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in acute lung injury mice. Scientific Reports . 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep39889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee K. H., Suh-Kim H., Lee B. H., et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell transplantation promotes functional recovery following acute spinal cord injury in rats. 2007. pp. 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Cheng H., Liu X., Hua R., et al. Clinical observation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in treatment for sequelae of thoracolumbar spinal cord injury. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2014;12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0253-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choi S. J., Kim J. K., Hwang S. D. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for chronic renal failure. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy . 2010;10:1217–1226. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2010.500284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Koppen A., Joles J. A., van Balkom B. W., et al. Human embryonic mesenchymal stem cell-derived conditioned medium rescues kidney function in rats with established chronic kidney disease. PLoS One . 2012;7, article e38746 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Golchin A., Farahany T. Z., Khojasteh A., Soleimanifar F., Ardeshirylajimi A. The clinical trials of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in skin diseases: an update and concise review. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy . 2019;14:22–33. doi: 10.2174/1574888X13666180913123424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shin T.-H., Kim H.-S., Choi S. W., Kang K.-S. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for inflammatory skin diseases: clinical potential and mode of action. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2017;18:p. 244. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]