Abstract

Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation has a wavelength range of 280–315 nm. Plants perceive UV-B as an environmental signal and a potential abiotic stress factor that affects development and acclimation. UV-B regulates photomorphogenesis including hypocotyl elongation inhibition, cotyledon expansion, and flavonoid accumulation, but high intensity UV-B can also harm plants by damaging DNA, triggering accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and impairing photosynthesis. Plants have evolved “sunscreen” flavonoids that accumulate under UV-B stress to prevent or limit damage. The UV-B receptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8 (UVR8) plays a critical role in promoting flavonoid biosynthesis to enhance UV-B stress tolerance. Recent studies have clarified several UVR8-mediated and UVR8-independent pathways that regulate UV-B stress tolerance. Here, we review these additions to our understanding of the molecular pathways involved in UV-B stress tolerance, highlighting the important roles of ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5, BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1, MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 13, MAP KINASE PHOSPHATASE 1, and ATM- and RAD3-RELATED. We also summarize the known interactions with visible light receptors and the contribution of melatonin to UV-B stress responses. Finally, we update a working model of the UV-B stress tolerance pathway.

Recent findings that update our understanding of the molecular pathway for ultraviolet-B radiation stress responses in plants are summarized.

Introduction

Perception of Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation, a component of sunlight, regulates photomorphogenesis, including hypocotyl elongation inhibition, cotyledon expansion, and flavonoid accumulation (Kim et al., 1998; Kliebenstein et al., 2002; Favory et al., 2009; Wargent et al., 2009; Yadav et al., 2020). However, high intensity, continuous full wavelength UV-B damages plants and leads to abnormal plant growth and development, which is called UV-B stress. UV-B stress affects DNA synthesis and DNA replication by forming pyrimidine dimers, resulting in heritable variation (Britt, 1995). In addition to causing direct DNA damage, UV-B forms reactive oxygen species, resulting in oxidative stress and the oxidation of lipids and proteins. Too much UV-B causes cell death, resulting in wilting, yellowing, and abnormal growth. UV-B stress also impairs photosynthesis (Kliebenstein et al., 2002; Frohnmeyer and Staiger, 2003; Favory et al., 2009; Hideg et al., 2013). With longer exposure to UV-B irradiation, the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) decreases continuously (Sztatelman et al., 2015).

ADVANCES

HY5 acts downstream of UVR8 to regulate photomorphogenesis and UV-B stress tolerance.

BES1 and MYB13 are involved in regulating photomorphogenesis and the biosynthesis of flavonoids.

MKP1 and ATR regulate UV-B stress responses.

Blue light photoreceptors CRYs and red/far-red light receptors Phys regulate UVR8 and UV-B stress tolerance.

Endogenous melatonin accumulation positively regulates UV-B signaling and UV-B stress tolerance.

To limit and repair UV-B-induced damage and promote acclimation to high-UV-B conditions, plants sense UV-B and induce protective responses to repair DNA damage, detoxify reactive oxygen species, and reduce cellular exposure to UV-B. Mutant screens in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) have identified many factors that participate in the plant UV-B response. Consistent with UV-B-inducing DNA damage, screens for increased sensitivity to UV-B identified mutants defective in the DNA damage repair pathway, such as uv resistance 1 (uvr1), uvr2, uvr3, and uv hypersensitive 1 (uvh1). Plants prevent or limit UV-B-induced damage by deploying antioxidant defenses and accumulating “sunscreen” flavonoids, including flavanol, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins. Indeed, mutant screens also identified mutants defective in ascorbic acid biosynthesis (vitamin c defective 1, vtc1), or in flavonoid and hydroxycinnamic acid biosynthesis (transparent testa 4 and 5, tt4, and tt5, which are defective in synthesis of flavonoids; uv-sensitive, uvs, which is defective in synthesis of kaempferol; ferulic acid hydroxylase 1, fah1, which is defective in the synthesis of sinapate esters; and uv tolerant 1, uvt1, which has elevated chalcone synthase (CHS) mRNA (Kliebenstein et al., 2002).

An UV-B photoreceptor is required for UV-B responses, including UV-B photomorphogenesis and UV-B stress tolerance (Rizzini et al., 2011; Tilbrook et al., 2013; Jenkins, 2014). Mutant screens identified the Arabidopsis UV-B photoreceptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8 (UVR8) in 2002, and UVR8 was revealed as a UV-B photoreceptor in 2011 (Kliebenstein et al., 2002; Rizzini et al., 2011). UVR8 is composed of 440 amino acids, with seven bladed β-propeller domains arranged to form a ring structure. In the absence of UV-B, the UVR8 monomer can form a salt bridge through electrostatic interactions between charged amino acids at the surface to form a homodimer. There are 13 tryptophan in the core domain of UVR8, 7 of which are located in the homodimeric interface, and Trp 285 and Trp 233 function as the chromophore for UV-B perception (Christie et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012).

UV-B irradiation does not affect UVR8 protein abundance; rather, after UV-B exposure, Trp 233 and Trp 285 of UVR8 will produce electron transfer and destroy the salt bridge of the UVR8 dimer, thus making UVR8 become the active monomer form, which becomes enriched in the nucleus where it activates UV-B responses (Kaiserli and Jenkins, 2007; Rizzini et al., 2011; Christie et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012). UVR8 re-dimerization is promoted by WD40-repeat REPRESSOR OF UV-B PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS (RUPs) proteins (Gruber et al., 2010; Heijde and Ulm, 2013). The transcripts of RUPs are UV-B-induced and RUPs proteins can physically interact with UVR8 and mediate UVR8 re-dimerization, so as to negatively regulate UV-B signal transduction (Gruber et al., 2010; Heijde and Ulm, 2013). CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase and it is central to many of the photomorphogenic pathways regulated by various photoreceptors. The UV-B-dependent interaction between UVR8 and COP1 is not only a key mechanism for UV-B signaling but also essential for the nuclear accumulation of UVR8 in response to UV-B (Favory et al., 2009; Qian et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2016). UVR8 also regulates transcription factors MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 73/77 (MYB73/MYB77), MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 13 (MYB13), WRKY DNA-BINDING PROTEIN 36 (WRKY36), BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR1 (BES1), BES1-INTERACTING MYC-LIKE 1 (BIM1), and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4) and PIF5 to directly regulate transcription and photomorphogenesis (Liang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2019; Qian et al., 2020; Tavridou et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020).

Many reports have revealed the mechanisms of how plants tolerate UV-B stress. These molecular responses include direct regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis by transcription factors such as ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5), BES1, and MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 11/12/13/111 (MYB11/12/13/111; Liang et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2020), the regulation of HY5 transcription and HY5 protein stability (Ulm et al., 2004; Oravecz et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2012; Binkert et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019) and the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and ATM- and RAD3-RELATED (ATR) independent of UVR8 (Gonzalez Besteiro et al., 2011; Gonzalez Besteiro and Ulm, 2013).

Here, we update and summarize current known regulatory mechanisms for UV-B stress tolerance, mostly focusing on work in Arabidopsis, with key examples from crops and other model systems.

HY5 acts downstream of UVR8 to regulate photomorphogenesis and UV-B stress tolerance

HY5 inhibits hypocotyl elongation and promotes flavonoid biosynthesis

In Arabidopsis, the basic leucine zipper transcription factors HY5 and HY5-HOMOLOG (HYH) mediate UV-B-induced changes in gene expression downstream of the photoreceptor UVR8 and the hy5 mutants are hypersensitive to UV-B stress (Ulm et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2005; Oravecz et al., 2006; Brown and Jenkins, 2008; Stracke et al., 2010; Feher et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012). UV-B induces HY5 expression and this is part of the mechanism through which UV-B inhibits hypocotyl elongation. It also promotes the transcription of flavonoid biosynthesis genes to regulate UV-B stress tolerance (Ulm et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2005; Oravecz et al., 2006; Brown and Jenkins, 2008; Stracke et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2012; Binkert et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2018).

The R2R3-MYB transcription factors such as PRODUCTION OF FLAVONOL GLYCOSIDES (PFG1)/MYB12, PFG2/MYB11, and PFG3/MYB111 are specifically involved in regulating flavonol biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Stracke et al., 2007). UVR8 and HY5 promote the transcription of these PFG-MYB genes in response to UV-B and the PFG MYBs work with HY5 to regulate the expression of downstream target genes, including CHS, leading to flavonol biosynthesis (Cloix and Jenkins, 2008; Favory et al., 2009; Stracke et al., 2010).

UV-B stabilizes HY5 protein by inhibiting the function of COP1

Arabidopsis COP1, WRKY DNA-BINDING PROTEIN 36 (WRKY36), and SALT TOLERANCE/B-BOX DOMAIN PROTEIN24 (STO/BBX24) are involved in regulating HY5 expression or HY5 protein abundance in response to UV-B light (Jiang et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2013; Podolec and Ulm, 2018; Yang et al., 2018). COP1 interacts with UVR8 in a UV-B-dependent manner and is important for the nuclear accumulation of UVR8 after UV-B irradiation (Oravecz et al., 2006; Favory et al., 2009; Jenkins, 2009; Cloix et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012, 2014; Yin et al., 2015, 2016). COP1 interacts with SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA (SPA1) and other components of E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes to promote the ubiquitination and degradation of HY5 in the nucleus in the dark. After UV-B irradiation, UVR8 accumulates in the nucleus and interacts with COP1 so that it disengages from the CULLIN4–DAMAGED DNA BINDING PROTEIN 1 (CUL4–DDB1)-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, thus stabilizing HY5 protein (Huang et al., 2013; Podolec and Ulm, 2018). As the negative regulators of UV-B signaling, RUP1 and RUP2 not only promote the re-dimerization of UVR8, but also act together with the CUL4–DDB1-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex to promote the degradation of HY5 in a prolonged response to low light with UV-B. At the same time, COP1 interacts and degrades RUP1/2 proteins, thus stabilizes HY5 (Ren et al., 2019).

WRKY36 represses the expression of HY5

As early as 2014, an article proposed that there might be a transcription factor inhibiting the transcription of HY5 under visible light conditions; UV-B treatment would remove the inhibition (Binkert et al., 2014). In 2018, Yang et al. reported a UVR8-interacting transcription factor, WRKY36, discovered through yeast two-hybrid screening using UVR8 as the bait. WRKY36 is transcriptionally induced by UV-B in a UVR8-independent manner, suggesting that there might be other UV-B photoreceptors responsible for this transcriptional change. WRKY36 directly interacts with the W-box of the HY5 promoter and represses HY5 expression, while UV-B-activated nuclear-localized UVR8 inhibits WRKY36 DNA-binding activity to suppress its inhibition of HY5 expression (Yang et al., 2018).

BBX24 interacts with and antagonizes the function of HY5

Multiple HY5-interacting proteins have been identified and characterized, including HYH, G-BOX BINDING FACTOR1 (GBF1), CALMODULIN7 (CAM7), B-BOX DOMAIN PROTEIN21 (BBX21), BBX22, BBX24, BBX25, BBX28, BBX32, COLD REGULATED 27 (COR27), and COR28. These factors interact with HY5 to positively or negatively regulate HY5 transcriptional activity (Holm et al., 2002; Datta et al., 2006, 2008; Holtan et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2012; Gangappa et al., 2013; Abbas et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). The B-box-type transcription factor STO/BBX24 acts as a negative regulator in red and blue light signaling (Indorf et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2011; Xu, 2020). BBX24 is upregulated by UV-B and inhibits the UV-B response in Arabidopsis roots and stems. BBX24 interacts with COP1 and acts downstream of COP1 in UV-B signaling. BBX24 also interacts with HY5, inhibits UV-B-induced HY5 expression, and thus negatively regulates UV-B-regulated gene expression and photomorphogenesis (Jiang et al., 2012). Other HY5-interacting proteins might also be involved in UV-B stress tolerance as they regulate the activity of HY5. COR27 physically interacts with HY5 to inhibit its transcription and fine-tunes skotomorphogenesis development in the dark and photomorphogenic development in the light (Li et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). The expression of COR27 and COR28 is regulated by blue light, cold temperatures, and the circadian clock; these genes might integrate multiple signals to regulate HY5 and UV-B responses.

BES1 and MYB13 are involved in regulating the biosynthesis of flavonoids

BES1 represses the expression of MYB11/12/111

Through yeast two-hybrid screening of Arabidopsis libraries using UVR8 as the bait, Liang et al. found that UVR8 interacts with the transcription factors BES1 and BIM1 (Liang et al., 2018). BES1 and BIM1 are brassinosteroid (BR) signaling components. BRs are steroid hormones that regulate plant growth and development, such as skotomorphogenesis and photomorphogenesis, and mediate biotic and abiotic stress responses (Clouse, 2011). BRs are perceived by the surface receptor kinase BR-INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1), which initiates a signaling cascade to activate the downstream transcription factors BES1 and BZR1 (BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT 1) and promote the expression of BR target genes (Li and Chory, 1997; He et al., 2002; Nam and Li, 2002). BIM1 interacts with BES1 and they act coordinately to regulate BR-induced gene expression and hypocotyl elongation (Yin et al., 2005). UVR8 mainly interacts with dephosphorylated BES1, the active form in BR signaling and plant development regulation, and BR treatment induces the dephosphorylation of BES1 and the UVR8–BES1 complex formation (Vert and Chory, 2006; Liang et al., 2018).

BR signaling is involved in the UVR8-regulated hypocotyl inhibition (Liang et al., 2018) and negatively affects plant tolerance to UV-B stress. BR-deficient and BR signaling mutants have altered UV-B stress tolerance, and BES1 acts downstream of BRI1 to inhibit UV-B stress tolerance. BES1 binds to the promoters of flavonol biosynthesis-related PFG-MYBs in a BR-enhanced manner to inhibit gene transcription, thus inhibiting flavonol biosynthesis and UV-B tolerance (Liang et al., 2020). The transcription of PFG-MYB genes and the accumulation of flavonol are substantially higher in BR deficient mutants than in the wild-type. Genetic experiments showed that the function of BES1 in regulating flavonol synthesis and resisting UV-B stress was dependent on PFG-MYB genes. UVR8 interacts with BES1 to inhibit BES1’s binding to plant growth-related genes (such as SAUR-AC), repressing their expression and BR-promoted hypocotyl elongation (Liang et al., 2018), but UV-B and UVR8 do not affect BES1 binding to the promoters of PFG-MYBs. UV-B with a wavelength range of 311–313 nm does not affect the expression of BES1, while UV-B treatment with a wavelength range of 280–315 nm significantly inhibits its transcription, indicating different mechanisms regulating different target genes (Liang et al., 2020).

The BES1–PFG-MYB module is regulated by BRs and UV-B stress at different levels. The role of BES1 in UV-B stress tolerance is regulated by BRs, since BES1 binds to PFG-MYBs in a BR-dependent manner and BR promotes the dephosphorylation of BES1 to promote its binding to PFG MYBs. UV-B inhibits the transcription of BES1 in a UVR8-independent manner via an unknown mechanism. Moreover, BES1 is a key factor mediating the tradeoff between plant growth and UV-B stress tolerance. Similar to the results in Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa) and maize (Zea mays), BR-deficient mutants are also more resistant to UV-B stress than wild-type plants, suggesting that the mechanism by which BR regulates flavonol biosynthesis and UV-B tolerance may be conserved in many plants, including crops (Liang et al., 2020).

UVR8 interacts with MYB13 and induces the biosynthesis of flavonoids

The transcription factor MYB13 also regulates the biosynthesis of flavonoids (Qian et al., 2020). Using a dexamethasone-inducible system to specifically activate UVR8 expression in the nucleus allowed examining transcriptomic changes in response to UV-B and UVR8 activation. MYB13 was highly upregulated by nucleus-localized UVR8. MYB13 protein functions as a transcription factor to regulate the expression of genes involved in auxin response and flavonoid biosynthesis through direct binding with their promoters. UVR8 also physically interacts with MYB13. Phenotypic analysis showed that MYB13 plays a positive role in regulating UV-B-induced cotyledon opening and UV-B stress acclimation. MYB13 binds directly to the promoters of CHS, CHALCONE FLAVANONE ISOMERASE (CHI), and FLAVONOL SYNTHASE 1 (FLS) to promote their transcription and flavonol accumulation. The binding of MYB13 to the CHS and CHI promoters is UV-B enhanced and the process is UVR8-dependent (Qian et al., 2020).

BES1 regulates flavonol biosynthesis and UV-B stress tolerance in a UVR8-independent manner, while MYB13 regulates flavonol biosynthesis in a UVR8-dependent manner, demonstrating that plants employ multiple pathways to regulate flavonol biosynthesis and UV-B acclimation.

MAP KINASE PHOSPHATASE 1 and ATR regulate UV stress responses

In addition to UVR8-mediated UV-B signaling, work in Arabidopsis has identified mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways that participate in UV stress tolerance (Ulm et al., 2001, 2002; Ulm, 2003; Kalbina and Strid, 2006). MAPK cascades convert external stimuli into cellular signals by phosphorylating MAPK substrates (Rodriguez et al., 2010). The Arabidopsis MAPK PHOSPHATASE 1 (MKP1) defective mutant mkp1 is more sensitive to UV-B stress than the wild-type. MPK3 and MPK6 act downstream of MKP1 and are activated by UV-B stress; MKP1 promotes plant recovery by inactivating MPK3 and MPK6 after the stress occurs. The mpk3 and mpk6 mutants are, therefore, more tolerant to UV-B stress, and the UV-B stress-sensitive phenotype of mkp1 partially depends on MPK3 and MPK6 (Gonzalez Besteiro et al., 2011).

MKP1 mainly responds to acute UV-B stress and is UVR8 independent, since the phenotype of uvr8 mutants under acute UV-B stress is the same as the wild-type and the mutation of MKP1 does not affect UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis or UV-B-induced flavonoid accumulation. When UV-B-induced secondary metabolites accumulate, or DNA damage repair enzymes are activated, MAPK activation caused by acute UV-B stress is weakened. Knocking out MKP1 in the uvr8 background enhanced UV-B stress sensitivity under simulated sunlight, indicating that MKP1 contributes to UV-B stress resistance in the natural environment, especially when UVR8-regulated UV-B acclimation is insufficient to resist the stress (Gonzalez Besteiro et al., 2011).

UV-B stress damages DNA, forming pyrimidine dimers, and this initiates UV-B-dependent MPK3 and MPK6 activation (Ulm et al., 2002; Gonzalez Besteiro and Ulm, 2013). ATR belongs to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-like kinase family. ATR is important in DNA damage responses and can be activated by DNA damage. The atr mutant is hypersensitive to UV-B and the DNA replication inhibitor hydroxyurea, which inhibits nucleotide reductase, preventing cytidine acid conversion to deoxycytidine and thereby inhibiting DNA synthesis (Culligan et al., 2004; Sancar et al., 2004). When plants are grown vertically on Murashige and Skoog medium plates, UV-B stress significantly inhibits the elongation of atr primary roots, but not above-ground parts that are comparable to the wild type, whereas both above- and below-ground parts of the mkp1 mutant are more sensitive to UV-B stress. The primary root length of atr is sensitive to hydroxyurea, and treatment with hydroxyurea produced more dead cells in prevascular tissue and the stem cell zone of atr primary roots than in the wild-type. In contrast, the root length and number of dead cells in mkp1 is the same as the wild-type under hydroxyurea treatment, indicating that UV-B-induced MAPK activation is not caused by DNA replication stress. In the atr primary root, UV-B-induced CYCB1;1 transcription is higher than the wild-type (Culligan et al., 2004), while UV-B-induced CYCB1;1 transcription in mkp1 is the same. These results indicate that ATR and MKP1 regulate different pathways in response to UV-B stress in roots. In young leaves, UV-B-induced CYCB1;1 transcription was affected in mkp1, but not atr. This is consistent with the observation that UV-B stress causes a leaf bleaching phenotype in mkp1 mutants. MKP1 might control CYCB1;1 transcription to promote UV-B stress tolerance in the above-ground parts of plants (Gonzalez Besteiro and Ulm, 2013).

Other pathways

The signaling pathways for different wavelengths of light interact. For example, blue light signals sensed by the cryptochrome (CRY) blue light photoreceptors regulate UVR8 and UV-B tolerance. The WD40-repeat proteins REPRESSOR OF UV-B PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS 1 (RUP1) and RUP2 negatively regulate the UV-B signaling pathway and directly interact with UVR8 to mediate its re-dimerization (Gruber et al., 2010; Heijde and Ulm, 2013). Blue light upregulates RUP1 and RUP2 transcription, which requires CRY1, CRY2, phytochrome A (phyA), and HY5. RUP2 accumulates and promotes the re-dimerization of UVR8.

UV-B also induces the transcription of BLUE-LIGHT INHIBITOR OF CRY1 (BIC1) and BIC2 in a UVR8- and HY5-dependent manner. BIC1 and BIC2 are negative regulators in blue-light signaling that interact with CRYs to suppress the blue-light-dependent dimerization of CRYs (Wang et al., 2016). CRY1 and CRY2 inhibit UVR8-mediated UV-B responses, and UV-B responses are stronger in the cry1 cry2 double mutant than in the wild-type. CRYs and PHYs also contribute to UVR8-mediated UV-B acclimation and tolerance, as the cry1 uvr8 and phyB uvr8 double mutants are more sensitive to UV-B stress than the uvr8 single mutant (Tissot and Ulm, 2020). uvr8 cry1 cry2 triple mutants cannot survive under natural sunlight, which also indicates photoreceptors are crucial for plant survival (Rai et al., 2019, 2020).

Melatonin (N‐acetyl‐5‐methoxytryptamine) belongs to indole heterocyclic compounds. As an antioxidant, in addition to scavenging free radicals directly, it can also upregulate the production of antioxidant and reduce oxidation-promoting enzymes. (Hardeland and Pandi-Perumal, 2005; Li et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2013). UV-B increases melatonin content by upregulating melatonin biosynthesis-related genes (Yao et al., 2021). In plants, exogenous melatonin reduces peroxide content and the lipid peroxidation end product, malondialdehyde, caused by UV-B. The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) is also higher than in untreated plants and UV-B response genes are upregulated, indicating that melatonin not only acts as an antioxidant, but also regulates gene transcription. Overexpressing melatonin biosynthesis genes in vivo leads to the induction of UV-B response genes and transgenic plants are more UV-B stress tolerant than the wild-type, while the melatonin biosynthesis-defective mutants show the opposite phenotype. This indicates that endogenous melatonin accumulation positively regulates UV-B signaling and UV-B stress tolerance (HaskirLi et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2021).

Conclusion and perspectives

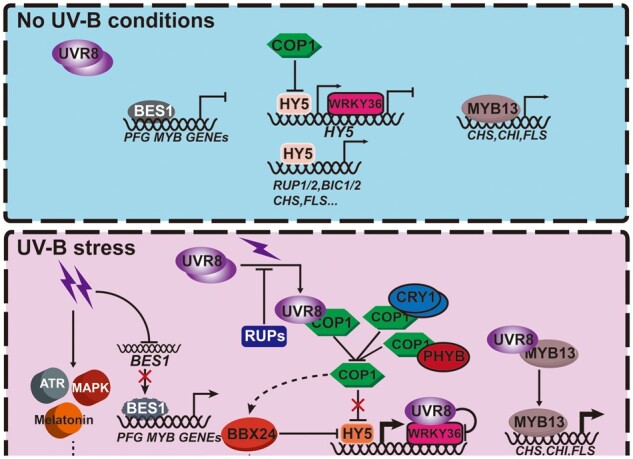

UV-B causes DNA damage, triggers the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and impairs photosynthesis. In response to UV-B stress, plants biosynthesize UV-B-absorbing secondary metabolites as sunscreen and initiate DNA damage repair to reduce oxidative stress and fix the damage. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of how plants respond to UV-B stress (Figure 1). First, UV-B regulates HY5 to promote flavonoid biosynthesis. UVR8 interacts with COP1 to inhibit COP1-mediated HY5 degradation, which stabilizes the HY5 protein; UVR8 interacts with the transcription factor WRKY36 to inhibit its DNA binding activity, thereby removing the transcriptional inhibition of HY5 by WRKY36. STO/BBX24 and other HY5-interacting proteins inhibit or promote the transcription of HY5 and negatively or positively regulate its transcription. Second, BES1 and MYB13 directly bind to the promoters of flavonoid biosynthesis genes to regulate their expression. Full wavelength UV-B relieves BES1-mediated inhibition of PFG-MYB transcription by repressing the transcription of BES1 in a UVR8-independent manner; UV-B also promotes the binding of MYB13 to the promoters of CHS and other flavonoid biosynthesis genes to promote their transcription. Third, MKP1 and ATR regulate UV-B stress response in a UVR8-independent manner. Their activities are induced by DNA damage caused by UV-B stress. In roots, MKP1 and ATR regulate different pathways, while only MKP1 functions in above-ground parts in response to acute UV-B stress. Fourth, the CRY blue light receptors and Phy red/far-red light receptors regulate UVR8 activity through the COP1–HY5–RUPs module and contribute to UV-B tolerance. Finally, UV-B induces the biosynthesis of melatonin, which removes peroxide and functions in regulating UV-B-responsive gene expression.

Figure 1.

Working model of UV-B stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. When plants are grown in white light (top, no UV-B conditions), UVR8 exists as an inactive homodimer. WRKY36 acts as a transcriptional repressor to repress HY5 transcription and COP1 promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of HY5 in the nucleus, thus repressing the transcription of UV-B-responsive genes. MYB13 binds to the promoters of flavonoid biosynthesis genes and promotes their expression; BR signaling activates BES1 to repress the transcription of PFG-MYBs controlling flavonoid biosynthesis. Under UV-B stress (bottom), UVR8 converts to monomers and accumulates in the nucleus. COP1 activity is repressed; thus the HY5 protein is stabilized and induces the transcription of UV-B responsive genes. UVR8 interacts with WRKY36 and inhibits WRKY36 DNA binding at the HY5 promoter. UVR8 enhances the affinity of MYB13 for the promoters of flavonoid biosynthesis genes. UV-B stress inhibits the expression of BES1 in a UVR8-independent manner to suppress the inhibition of PFG-MYBs; UV-B stress also activates ATR and MAPK pathways to increase UV-B stress tolerance. The stabilization of HY5 by UV-B and visible light also induces RUPs and BICs transcription and thus promotes the feedback regulation of UVR8 and Cryptochrome photoreceptor activities. BBX24 is UV-B induced, and COP1 interacts with BBX24 and is required for BBX24 accumulation. BBX24 also interacts with HY5 and antagonizes the function of HY5 in UV-B signaling.

Despite recent findings, many questions about UV-B stress responses remain to be answered. UVR8 accumulates in the nucleus in response to UV-B, then interacts with multiple transcription factors to regulate transcription, thus modulating photomorphogenesis and UV-B stress tolerance. Whether there is a regulatory mode beyond transcriptional regulation is still not known and worth exploring. Moreover, many UV-B responses are independent of UVR8, such as the transcription of WRKY36 induced by UV-B and the transcription of BES1 that is repressed by full wavelength UV-B (Yang et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2020). UV-B induces the accumulation of secondary metabolites (sinapate esters and flavonoids), but the accumulation of sinapate esters does not differ from the wild-type in uvr8 mutants and the accumulation of flavonoids is not completely abolished after UV-B treatment (Kliebenstein et al., 2002). These phenomena suggest that there may be additional UV-B photoreceptors that can sense UV-B signals and regulate these processes. Further exploring these questions will enrich our knowledge of the UV-B signaling pathway and inform efforts to improve plant tolerance to UV-B stress.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31825004, 31721001, 31730009), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB27030000), and the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS

Is there a regulatory mode beyond transcriptional regulation?

Are there additional UV-B photoreceptors that can sense UV-B signals?

C.S. and H.L. wrote the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Hongtao Liu (htliu@cemps.ac.cn).

References

- Abbas N, Maurya JP, Senapati D, Gangappa SN, Chattopadhyay S (2014) Arabidopsis CAM7 and HY5 physically interact and directly bind to the HY5 promoter to regulate its expression and thereby promote photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 26: 1036–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkert M, Kozma-Bognar L, Terecskei K, De Veylder L, Nagy F, Ulm R (2014) UV-B-responsive association of the Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 with target genes, including its own promoter. Plant Cell 26: 4200–4213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt AB (1995) Repair of DNA damage induced by ultraviolet radiation. Plant Physiol 108: 891–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BA, Jenkins GI (2008) UV-B signaling pathways with different fluence-rate response profiles are distinguished in mature Arabidopsis leaf tissue by requirement for UVR8, HY5, and HYH. Plant Physiol 146: 576–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BA, Cloix C, Jiang GH, Kaiserli E, Herzyk P, Kliebenstein DJ, Jenkins GI (2005) A UV-B-specific signaling component orchestrates plant UV protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 18225–18230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Arvai AS, Baxter KJ, Heilmann M, Pratt AJ, O'Hara A, Kelly SM, Hothorn M, Smith BO, Hitomi K, et al. (2012) Plant UVR8 photoreceptor senses UV-B by tryptophan-mediated disruption of cross-dimer salt bridges. Science 335: 1492–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloix C, Jenkins GI (2008) Interaction of the Arabidopsis UV-B-specific signaling component UVR8 with chromatin. Mol Plant 1: 118–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloix C, Kaiserli E, Heilmann M, Baxter KJ, Brown BA, O'Hara A, Smith BO, Christie JM, Jenkins GI (2012) C-terminal region of the UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 initiates signaling through interaction with the COP1 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 16366–16370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD (2011) Brassinosteroids. Arabidopsis Book 9: e0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culligan K, Tissier A, Britt A (2004) ATR regulates a G2-phase cell-cycle checkpoint in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 16: 1091–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Hettiarachchi GH, Deng XW, Holm M (2006) Arabidopsis CONSTANS-LIKE3 is a positive regulator of red light signaling and root growth. Plant Cell 18: 70–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Johansson H, Hettiarachchi C, Irigoyen ML, Desai M, Rubio V, Holm M (2008) LZF1/SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG3, an Arabidopsis B-box protein involved in light-dependent development and gene expression, undergoes COP1-mediated ubiquitination. Plant Ccell 20: 2324–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favory JJ, Stec A, Gruber H, Rizzini L, Oravecz A, Funk M, Albert A, Cloix C, Jenkins GI, Oakeley EJ, et al. (2009) Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J 28: 591–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feher B, Kozma-Bognar L, Kevei E, Hajdu A, Binkert M, Davis SJ, Schafer E, Ulm R, Nagy F (2011) Functional interaction of the circadian clock and UV RESISTANCE LOCUS 8-controlled UV-B signaling pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 67: 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohnmeyer H, Staiger D (2003) Ultraviolet-B radiation-mediated responses in plants. Balancing damage and protection. Plant Physiol 133: 1420–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangappa SN, Crocco CD, Johansson H, Datta S, Hettiarachchi C, Holm M, Botto JF (2013) The Arabidopsis B-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regulating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 25: 1243–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Besteiro MA, Ulm R (2013) ATR and MKP1 play distinct roles in response to UV-B stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J 73: 1034–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Besteiro MA, Bartels S, Albert A, Ulm R (2011) Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1 and its target MAP kinases 3 and 6 antagonistically determine UV-B stress tolerance, independent of the UVR8 photoreceptor pathway. Plant J 68: 727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber H, Heijde M, Heller W, Albert A, Seidlitz HK, Ulm R (2010) Negative feedback regulation of UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 20132–20137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR (2005) Melatonin, a potent agent in antioxidative defense: actions as a natural food constituent, gastrointestinal factor, drug and prodrug. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskirli H, Yilmaz O, Ozgur R, Uzilday B, Turkan I (2020) Melatonin mitigates UV-B stress via regulating oxidative stress response, cellular redox and alternative electron sinks in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 182: 112592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JX, Gendron JM, Yang Y, Li J, Wang ZY (2002) The GSK3-like kinase BIN2 phosphorylates and destabilizes BZR1, a positive regulator of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 10185–10190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijde M, Ulm R (2013) Reversion of the Arabidopsis UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 to the homodimeric ground state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 1113–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hideg E, Jansen MA, Strid A (2013) UV-B exposure, ROS, and stress: inseparable companions or loosely linked associates? Trends Plant Sci 18: 107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm M, Ma LG, Qu LJ, Deng XW (2002) Two interacting bZIP proteins are direct targets of COP1-mediated control of light-dependent gene expression in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 16: 1247–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtan HE, Bandong S, Marion CM, Adam L, Tiwari S, Shen Y, Maloof JN, Maszle DR, Ohto MA, Preuss S, et al. (2011) BBX32, an Arabidopsis B-Box protein, functions in light signaling by suppressing HY5-regulated gene expression and interacting with STH2/BBX21. Plant Physiol 156: 2109–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ouyang X, Yang P, Lau OS, Chen L, Wei N, Deng XW (2013) Conversion from CUL4-based COP1-SPA E3 apparatus to UVR8-COP1-SPA complexes underlies a distinct biochemical function of COP1 under UV-B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 16669–16674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ouyang X, Yang P, Lau OS, Li G, Li J, Chen H, Deng XW (2012) Arabidopsis FHY3 and HY5 positively mediate induction of COP1 transcription in response to photomorphogenic UV-B light. Plant Cell 24, 4590–4606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yang P, Ouyang X, Chen L, Deng XW (2014) Photoactivated UVR8-COP1 module determines photomorphogenic UV-B signaling output in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 10: e1004218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indorf M, Cordero J, Neuhaus G, Rodriguez-Franco M (2007) Salt tolerance (STO), a stress-related protein, has a major role in light signalling. Plant J 51: 563–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GI (2009) Signal transduction in responses to UV-B radiation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 407–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GI (2014) Structure and function of the UV-B photoreceptor UVR8. Curr Opin Struct Biol 29: 52–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Wang Y, Li QF, Bjorn LO, He JX, Li SS (2012) Arabidopsis STO/BBX24 negatively regulates UV-B signaling by interacting with COP1 and repressing HY5 transcriptional activity. Cell Res 22: 1046–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiserli E, Jenkins GI (2007) UV-B promotes rapid nuclear translocation of the Arabidopsis UV-B specific signaling component UVR8 and activates its function in the nucleus. Plant Cell 19: 2662–2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbina I, Strid A (2006) The role of NADPH oxidase and MAP kinase phosphatase in UV-B-dependent gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ 29: 1783–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BC, Tennessen DJ, Last RL (1998) UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 15: 667–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Lim JE, Landry LG, Last RL (2002) Arabidopsis UVR8 regulates ultraviolet-B signal transduction and tolerance and contains sequence similarity to human regulator of chromatin condensation 1. Plant Physiol 130: 234–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wang P, Wei Z, Liang D, Liu C, Yin L, Jia D, Fu M, Ma F (2012) The mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin on salinity-induced stress in Malus hupehensis. J Pineal Res 53: 298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chory J (1997) A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell 90: 929–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu C, Zhao Z, Ma D, Zhang J, Yang Y, Liu Y, Liu H (2020) COR27 and COR28 Are Novel Regulators of the COP1-HY5 Regulatory Hub and Photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 32: 3139–3154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T, Mei S, Shi C, Yang Y, Peng Y, Ma L, Wang F, Li X, Huang X, Yin Y, Liu H (2018) UVR8 interacts with BES1 and BIM1 to regulate transcription and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell 44: 512–523 e515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T, Shi C, Peng Y, Tan H, Xin P, Yang Y, Wang F, Li X, Chu J, Huang J, et al. (2020) Brassinosteroid-activated BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR 1 inhibits flavonoid biosynthesis and coordinates growth and UV-B stress responses in plants. Plant Cell 32: 3224–3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Jiang Y, Li J, Yan T, Fan L, Liang J, Chen ZJ, Xu D, Deng XW (2018) B-BOX DOMAIN PROTEIN28 negatively regulates photomorphogenesis by repressing the activity of transcription factor HY5 and undergoes COP1-mediated degradation. Plant Cell 30: 2006–2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam KH, Li J (2002) BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110: 203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oravecz A, Baumann A, Mate Z, Brzezinska A, Molinier J, Oakeley EJ, Adam E, Schafer E, Nagy F, Ulm R (2006) CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 is required for the UV-B response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 1975–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolec R, Ulm R (2018) Photoreceptor-mediated regulation of the COP1/SPA E3 ubiquitin ligase. Curr Opin Plant Biol 45: 18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C, Chen Z, Liu Q, Mao W, Chen Y, Tian W, Liu Y, Han J, Ouyang X, Huang X (2020) Coordinated transcriptional regulation by the UV-B photoreceptor and multiple transcription factors for plant UV-B responses. Mol Plant 13: 777–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C, Mao W, Liu Y, Ren H, Lau OS, Ouyang X, Huang X (2016) Dual-source nuclear monomers of UV-B light receptor direct photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 9: 1671–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai N, Neugart S, Yan Y, Wang F, Siipola SM, Lindfors AV, Winkler JB, Albert A, Brosche M, Lehto T, et al. (2019) How do cryptochromes and UVR8 interact in natural and simulated sunlight? J Exp Bot 70: 4975–4990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai N, O'Hara A, Farkas D, Safronov O, Ratanasopa K, Wang F, Lindfors AV, Jenkins GI, Lehto T, Salojarvi J, et al. (2020) The photoreceptor UVR8 mediates the perception of both UV-B and UV-A wavelengths up to 350 nm of sunlight with responsivity moderated by cryptochromes. Plant Cell Environ 43: 1513–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Han J, Yang P, Mao W, Liu X, Qiu L, Qian C, Liu Y, Chen Z, Ouyang X, et al. (2019) Two E3 ligases antagonistically regulate the UV-B response in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 4722–4731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzini L, Favory JJ, Cloix C, Faggionato D, O'Hara A, Kaiserli E, Baumeister R, Schafer E, Nagy F, Jenkins GI, et al. (2011) Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science 332: 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MC, Petersen M, Mundy J (2010) Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 621–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S (2004) Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 39–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Sharma B, Hayes S, Kerner K, Hoecker U, Jenkins GI,Franklin KA (2019) UVR8 disrupts stabilisation of PIF5 by COP1 to inhibit plant stem elongation in sunlight. Nature Communications 10: 4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Ram H, Abbas N, Chattopadhyay S (2012) Molecular interactions of GBF1 with HY5 and HYH proteins during light-mediated seedling development in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 287: 25995–26009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R, Favory JJ, Gruber H, Bartelniewoehner L, Bartels S, Binkert M, Funk M, Weisshaar B, Ulm R (2010) The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Cell Environ 33: 88–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R, Ishihara H, Huep G, Barsch A, Mehrtens F, Niehaus K, Weisshaar B (2007) Differential regulation of closely related R2R3-MYB transcription factors controls flavonol accumulation in different parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. Plant J 50: 660–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztatelman O, Grzyb J, Gabrys H, Banas AK (2015) The effect of UV-B on Arabidopsis leaves depends on light conditions after treatment. BMC Plant Biol 15: 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavridou E, Pireyre M, Ulm R (2020) Degradation of the transcription factors PIF4 and PIF5 under UV-B promotes UVR8-mediated inhibition of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J 101: 507–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook K, Arongaus AB, Binkert M, Heijde M, Yin R, Ulm R (2013) The UVR8 UV-B photoreceptor: perception, signaling and response. Arabidopsis Book 11: e0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissot N, Ulm R (2020) Cryptochrome-mediated blue-light signalling modulates UVR8 photoreceptor activity and contributes to UV-B tolerance in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 11: 1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R (2003) Molecular genetics of genotoxic stress signalling in plants. Topics Curr Genet 4: 217–240 [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Baumann A, Oravecz A, Mate Z, Adam E, Oakeley EJ, Schafer E, Nagy F (2004) Genome-wide analysis of gene expression reveals function of the bZIP transcription factor HY5 in the UV-B response of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 1397–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Peck SC, Zhu T, Wang X, Shinozaki K, Paszkowski J (2002) Distinct regulation of salinity and genotoxic stress responses by Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1. Embo J 21: 6483–6493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Revenkova E, di Sansebastiano GP, Bechtold N, Paszkowski J (2001) Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase is required for genotoxic stress relief in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 699–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Chory J (2006) Downstream nuclear events in brassinosteroid signalling. Nature 441: 96–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zuo Z, Wang X, Gu L, Yoshizumi T, Yang Z, Yang L, Liu Q, Liu W, Han YJ, et al. (2016) Photoactivation and inactivation of Arabidopsis cryptochrome 2. Science 354: 343–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargent JJ, Gegas VC, Jenkins GI, Doonan JH, Paul ND (2009) UVR8 in Arabidopsis thaliana regulates multiple aspects of cellular differentiation during leaf development in response to ultraviolet B radiation. New Phytol 183: 315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Hu Q, Yan Z, Chen W, Yan C, Huang X, Zhang J, Yang P, Deng H, Wang J, et al. (2012) Structural basis of ultraviolet-B perception by UVR8. Nature 484: 214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D (2020) COP1 and BBXs-HY5-mediated light signal transduction in plants. New Phytol 228: 1748–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav A, Singh D, Lingwan M, Yadukrishnan P, Masakapalli SK, Datta S (2020) Light signaling and UV-B-mediated plant growth regulation. J Integr Plant Biol 62: 1270–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Marquardt K, Indorf M, Jutt D, Kircher S, Neuhaus G, Rodriguez-Franco M (2011) Nuclear localization and interaction with COP1 are required for STO/BBX24 function during photomorphogenesis. Plant Physiol 156: 1772–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Liang T, Zhang L, Shao K, Gu X, Shang R, Shi N, Li X, Zhang P, Liu H (2018) UVR8 interacts with WRKY36 to regulate HY5 transcription and hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants 4: 98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhang L, Chen P, Liang T, Li X, Liu H (2020) UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 interacts with MYB73/MYB77 to regulate auxin responses and lateral root development. EMBO J 39: e101928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JW, Ma Z, Ma YQ, Zhu Y, Lei MQ, Hao CY, Chen LY, Xu ZQ, Huang X (2021) Role of melatonin in UV-B signaling pathway and UV-B stress resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ 44: 114–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Wang P, Li M, Ke X, Li C, Liang D, Wu S, Ma X, Li C, Zou Y, et al. (2013) Exogenous melatonin improves Malus resistance to Marssonina apple blotch. J Pineal Res 54: 426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R, Arongaus AB, Binkert M, Ulm R (2015) Two distinct domains of the UVR8 photoreceptor interact with COP1 to initiate UV-B signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27: 202–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R, Skvortsova MY, Loubery S, Ulm R (2016) COP1 is required for UV-B-induced nuclear accumulation of the UVR8 photoreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: E4415–E4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Vafeados D, Tao Y, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J (2005) A new class of transcription factors mediates brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Cell 120: 249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Huai J, Shang F, Xu G, Tang W, Jing Y, Lin R (2017) A PIF1/PIF3-HY5-BBX23 Transcription factor cascade affects photomorphogenesis. Plant Physiol 174: 2487–2500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Zhou H, Lin F, Zhao X, Jiang Y, Xu D, Deng XW (2020) COLD-REGULATED GENE27 integrates signals from light and the circadian clock to promote hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 32: 3155–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]