Abstract

Introduction

A third of new HIV infections occur among young people and the majority of young people living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa. We examined the strength of Nigerian youth preferences related to HIV testing and HIV self-testing.

Methods

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) were conducted among Nigerian youth (age 14-24 years). Participants completed one of two DCEs: 1) preferred qualities of HIV testing (cost, location of test, type of test, person who conducts the test and availability of HIV medicine at the testing site); 2) preferred qualities of HIVST kits (cost, test quality, type of test, extra items and support if tested positive). A random parameters logit (RPL) model measured the strength of preferences.

Results

A total of 504 youth participated: mean age 21 (SD 2) years, 38% men, and 35% had higher than secondary school education. There was a strong preference overall to test given the scenarios presented, although males were less likely to test for HIV or use HIVST kits. Youth preferred HIV testing services (with attributes in order of importance) that are free, blood-based testing, available in private/public hospitals or home, for HIV medications to be available in the same location as testing, and a doctor conducts the test. Participants preferred HIVST kits (with attributes in order of importance) that are available from community health centers, free, approved by the WHO, include other sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, have the option of an online chat and oral-based HIVST.

Conclusions

HIV home testing was equally preferred to testing in a hospital, suggesting a viable market for HIVST if kits account for youth preferences. Male youth were less likely to choose to test for HIV or use HIVST kits, underscoring the need for further efforts to encourage HIV testing among young males.

Keywords: HIV, adolescent, health services, Nigeria, health preference research, HIV self-testing

1). INTRODUCTION

HIV is the leading cause of death among young people (age 10-24 years) living in Africa and the second highest cause of death in young people globally.(1) Yet they have lower rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing compared to adults. Increasing the demand and coverage for HIV testing is a critical entry point into the HIV prevention and care continuum. Improved HIV testing coverage ensures people with unrecognized infection have the opportunity to link to care and treatment, in order to decrease onward HIV transmission and extend life to a near-normal life expectancy.(2) However, beyond diagnosis there are ongoing known challenges of linking people diagnosed with HIV to care.(3, 4) Nigeria has one of the world’s highest HIV burdens (i.e. 1.9 million people living with HIV),(5) yet less than 25% of Nigerians age 15-24 years have ever tested for HIV.(6, 7) HIV self-testing (HIVST), recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO),(8) is the process in which a person collects his or her own specimen, performs the test, and interprets the results. As of July 2019, 77 countries had HIVST policies,(9) but there is a need for country-specific evidence for optimal pricing and distribution strategies for HIVST. In particular, HIVST could be appealing to young people living in Africa.(10, 11) Also in 2019 the Nigeria Ministry of Health launched the operational guidelines for HIVST kit in the country to promote HIVST as a strategy to increase HIV testing in the country. Given that scaling up HIVST among young people is relatively new in Nigeria, data on what young people prefer would inform the optimization of HIVST implementation. For resource-limited contexts, it is critical that the most cost-effective services are funded to optimize uptake and ensure an efficient allocation of resources.

As it may not be possible to provide the ideal testing service with every desirable attribute, trade-offs are often made to select the attributes that will achieve the highest uptake. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) is a preference elicitation survey method based on Lancaster’s Theory of Demand which conceptualised demand for a good or service as the sum of the utility delivered by its different attributes.(12) A DCE can identify the characteristics of HIV testing services youths prefer, estimate the relative importance of each HIV test attribute, observe how they trade-off between these attributes, and evaluate how preferences might differ between subgroups of youth (i.e. market segments). DCEs are particularly valuable when there are limited observed market behaviours, for example when new technologies or goods or services are not yet widely accessible, like HIVST in Nigeria.(12) Although DCEs on HIV testing have been reported in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs),(13-23) only a couple have focused on young people.(15, 22) Given the potential for heterogeneity and uniqueness of the HIV epidemics in Malawi and Zimbabwe(15, 22) compared to Nigeria, there is value to gather country-specific data.

This study aims to use two DCEs to identify which components of HIV testing (DCETest) and self-testing (DCEKits) are most appealing to Nigerian youth and to explore preference heterogeneity among different groups of youth. The analysis could inform HIV testing and self-testing service configurations to maximize youth uptake of HIV testing.

2). METHODS

2.1. Development and piloting of choice tasks, attributes and levels

The development of the DCE followed a standard guideline.(24) A literature review of published studies around HIV testing and young people in sub-Saharan Africa was undertaken to identify key attributes influencing young people to test for HIV. This was used to create the topic guide for individual in-depth interviews and inform the design of the DCEs. We conducted a series of semi-structured in-depth interviews aimed at identifying factors that may influence young people’s decisions for choosing HIV testing services and uptake of HIVST in Nigeria. Participants for the in-depth interviews were recruited from technical colleges, institutional campuses, and open community settings in Lagos State. The in-depth interviews which lasted between 30 and 45 minutes were conducted by trained interviewers, in a closed room at a convenient location. In addition, real-time debriefing sessions with the qualitative field team provided further insights that informed the selection of the DCE attributes. In October 2018, a total of 65 youth (mean age=21 years, 56% females) were interviewed. The research team identified themes and domains related to preferences and factors influencing the use of HIV self-testing. Findings from the interviews are summarized here and reported in detail elsewhere.(25)

From the interviews, four salient themes emerged as important characteristics that influenced young people’s preferences for HIV self-testing. The four themes were cost, testing modality, access, and post-test support. The cost of services was an important driver of choice as the majority of participants noted that they would be willing to pay between 500 to 1,500 Naira (USD1.38 to 4.14) for oral HIV self-testing kits. In selecting a type of HIV testing modality, blood-based sample kits were more popular than saliva-based kits, but some preferred the saliva-based option due to their phobia of needles. Access location for HIVST kits was identified as a factor influencing choice. Some participants suggested they preferred to obtain the kits from youth-friendly centers, pharmacies, private health facilities, and online stores. In terms of the provision of post-test support, participants highlighted the importance of linkage to care with trained youth health workers for positive or linkage to HIV prevention services for negative test results and a toll-free helpline.

We developed a final list of attributes and levels based on the preliminary results from the interview. Using a think-aloud approach, 10 respondents were interviewed while completing the DCE choice tasks to discuss the overall framing of the survey (framing, complexity, and understandability), and attributes (terminology, appropriateness, interconnectedness). A revised second version of the DCEs, based on input from the first round of pilot testing, was administered among 20 respondents. We made minor alterations in wording to improve the comprehensibility of the questions.

2.2. Experimental design

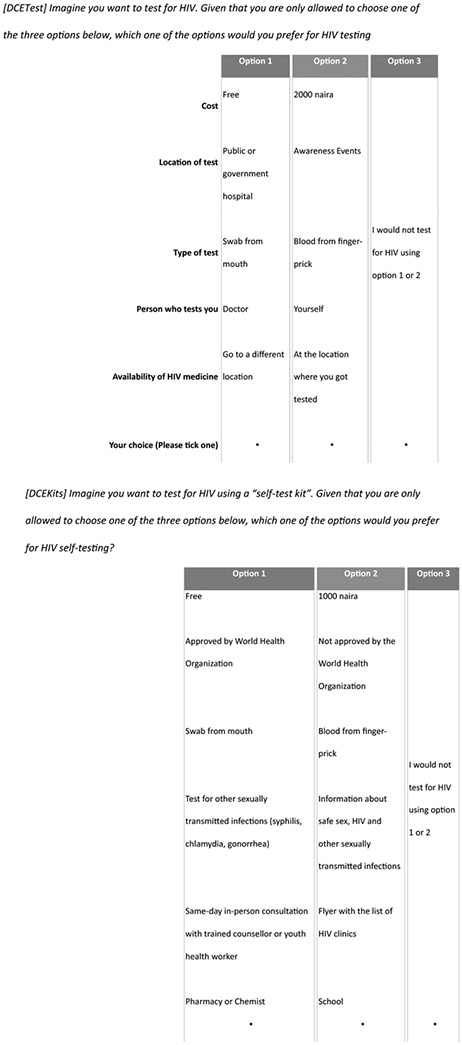

Attributes and levels were chosen that were meaningful to Nigerian youth and could be realistically influenced by policy changes. The final attributes chosen are shown in Table 1, and sample choice tasks are presented in Figure 1. Participants chose between two unlabeled alternatives with different combinations of attributes. Participants could also opt-out if none of the alternatives were preferred by the participant. The experimental designs for both DCEs were generated using NGENE (Version 1.2.1, Choicemetrics, USA) to identify a D-efficient statistical design of 24 choice tasks, allocated as two blocks of 12 tasks each. We reviewed each choice set to remove implausible combinations (the only one was the combination of person who conducts the test (yourself) and mode of testing (venepuncture). This may have decreased the d-optimality of the design but made the attribute levels more feasible. Parameter estimates from conditional logit analyses of the pilot data were used as priors with a normal distribution. To reduce cognitive burden (i.e. having to answer too many choice sets), participants were randomly assigned to complete one of two DCEs: DCETest evaluated the preferences for HIVST relative to other HIV testing modalities, and DCEKits evaluated the preferences for the type of HIVST kit.

Table 1.

Attributes and levels of the discrete choice experiment.

| Attributes | Levels |

|---|---|

| DCETest: HIV testing preferences | |

| Out of pocket cost (Naira) | Free |

| 500 | |

| 1000 | |

| 2000 | |

| Location of Test | Private hospital |

| Public/government hospital | |

| Community health centres | |

| Non-profit organizations | |

| Sexual Health Clinic | |

| Awareness Events | |

| Pharmacy or Chemist | |

| Home or self-testing | |

| Type of test | Blood test from arm (venipuncture) |

| Blood from finger-prick | |

| Swab from mouth | |

| Person who tests you | Doctor |

| Nurse | |

| Trained healthcare volunteer | |

| Yourself | |

| Availability of HIV Medicine | At location of testing |

| Go to different location | |

| DCEKits: HIVST kit characteristics | |

| Out of pocket cost (Naira) | Free |

| 500 | |

| 1000 | |

| 2000 | |

| Test quality | Not approved by the World Health Organization |

| Approved by the World Health Organization | |

| Type of Test | Blood from finger-prick |

| Swab from mouth | |

| Extra items | Test for other sexually transmitted infections (STI) (syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhoea) |

| Pregnancy test, condoms and/or contraceptive pill | |

| Information about safe sex, HIV and other STIs | |

| Malaria or tuberculosis test | |

| Support if test positive | Flyer with list of HIV clinics |

| Online-chat with trained counsellor or youth health worker | |

| Same-day in-person consultation with trained counsellor or youth health worker | |

| Same-day in-person consultation with doctor |

Figure 1.

Example choice sets

2.3. Data Collection and sampling strategy

From December 2018 to February 2019, participants between the ages of 14 to 24 years were recruited and enrolled from geographic clusters of venues in Lagos, Nigeria where youth frequented: technical colleges, universities, and open community settings such as community event centers. An outreach team that consisted of trained interviewers and HIV testing counselors from the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) visited the various sites and received permission to recruit and enroll participants. Potential participants were approached and were provided with detailed information about the study objectives and consent form. The trained interviewers administered the survey in a closed room at a convenient location in the recruitment site. The OraQuick® HIV Self-Test kit and a pictorial description on how to use the HIVST kit were shown to the participants but were not offered for testing. The survey was available in English only. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four sets of choice scenarios (i.e. two blocks of the DCETest and two blocks of DCEKits) using a paper-based survey containing 12 choice tasks. Upon completion of the survey, participants received a raffle ticket for a chance to win a portable tablet computer as compensation for their time.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the sociodemographic characteristics of participants. We compared the two groups using chi-square for categorical variables and a nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. We analyzed preference data using random parameters logit models (RPL) and RPL models with interaction terms to explore heterogeneity dependent on participant characteristics. The RPL model was chosen because of the panel nature of data (i.e. to account for correlation introduced by repeated observations from each participant), and to relax the assumptions of the independence from irrelevant alternatives (IIA) and that error terms are independently and identically distributed (IID). The models were estimated using a maximum likelihood approach with 500 Halton draws. Parameters were set to have an underlying normal distribution. We calculated the Akaike information criteria to assess model fit. Coefficients were effects coded.(26) In the tables for RPL model results, the coefficients represent the strength of preference for the attribute level (higher magnitude of a positive coefficient represents a higher positive preference (utility) for that attribute level whilst a higher magnitude of a negative coefficient represents a relatively higher negative preference (disutility) for that attribute level.

The degree to which respondent preferences were heterogeneous, i.e. the extent to which preferences vary in the sample, is described by the estimated standard deviation around each mean preference estimate and observed heterogeneity through interaction effects. We present the results from RPL models with interactions (age, gender, education level, ever had sex, and ever tested for HIV) in the Appendix. We only included interaction terms for attribute levels when the coefficient and standard deviation had a p value <0.10. Model estimations were performed using NLOGIT 6 (version 6, Econometric Software Inc, USA). Using the simulation function in NLOGIT,(27) we estimated the probabilities of people choosing to test for HIV (DCE1) or choosing to use an HIVST kit (DCE2) when presented with a status quo scenario, most and least preferred combinations of attribute levels using data from the RPL models.

3). RESULTS

A total of 504 youth completed the survey: 270 for DCETest and 234 for DCEKits. Table 2 summarizes their sociodemographic characteristics. Though there was an unequal distribution of completed surveys, Table 2 showed that observable sociodemographic characteristics were similar except for education level. For those who completed the DCETest survey, their median age was 21 (IQR 19-23), the proportion of males was 39%, proportion identifying as heterosexuals was 97%, and proportion of those who reported being sexually active in the last six months was 16%. For those who completed the DCEKits survey, their median age was 21 (IQR 20-23), the proportion of males was 37%, proportion identifying as heterosexuals was 97%, and proportion of those who reported being sexually active in the last six months was 18%. A total of 12% of participants reported it was hard or very hard to choose an option for the DCE.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of Nigerian youth (N=504)

| DCETest (N=270) n (%) |

DCEKits (N=234) n (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR), years | 21 (19-23) | 21 (20-23) | 0.15 |

| Mean age (SD), years | 20·7 (2·4) | 21·0 (2·1) | 0.13 |

| Male gender | 104 (39) | 87 (37) | 0.79 |

| Ethnicity | 0.74 | ||

| - Igbo | 31 (11) | 34 (15) | |

| - Yoruba | 201 (74) | 170 (73) | |

| - Other | 38 (14) | 29 (12) | |

| Education level | 0.02 | ||

| - Primary education or below | 17 (6) | 2 (1) | |

| - Secondary education | 169 (63) | 142 (61) | |

| - Polytechnic or National certificate of education | 30 (11) | 34 (15) | |

| - Tertiary education | 51 (19) | 53 (23) | |

| - Other | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Employment status | 0.41 | ||

| - Student | 187 (69) | 162 (69) | |

| - Full-time | 10 (4) | 4 (2) | |

| - Part-time | 9 (3) | 6 (3) | |

| - Self-employed | 23 (9) | 15 (6) | |

| - Unemployed | 7 (3) | 7 (3) | |

| Living with: | 0.88 | ||

| - Spouse | 8 (3) | 5 (2) | |

| - Parents | 164 (61) | 126 (54) | |

| - Relatives | 21 (8) | 23 (10) | |

| - Boy/girlfriend | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| - Friend | 22 (8) | 24 (10) | |

| - Alone | 19 (7) | 14 (6) | |

| - Other | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | |

| Sexual identity | 0.29 | ||

| - Heterosexual | 262 (97) | 227 (97) | |

| - Gay or other | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Sexually active in the last 6 months | 42 (16) | 42 (18) | 0.47 |

| Ever tested for HIV | 134 (50) | 135 (58) | 0.06 |

| Location of last HIV testing* | 0.47 | ||

| - Private hospital | 11 (8) | 13 (10) | |

| - Public/government hospital | 47 (35) | 36 (27) | |

| - Community health centre | 16 (12) | 20 (15) | |

| - Not-for-profit organizations | 8 (6) | 5 (4) | |

| - Sexual health clinic | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| - Awareness events | 36 (27) | 32 (24) | |

| - Pharmacy/Chemist | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| - Self-testing | 2 (1) | 8 (6) | |

| Self-perception that is likely or very likely to be infected with HIV | 17 (6) | 17 (7) | 0.59 |

| Heard of HIV self-testing | 87 (32) | 101 (43) | 0.01 |

IQR = interquartile range, SD = standard deviation

Numerators may not add up to the full sample size due to missing data.

The denominator is among those who ever tested (N=134 for DCETest; N=135 for DCEKits)

3.1. Preferences for HIV testing in general

Table 3 summarize preferences for HIV testing services. The large negative coefficient for opt-out indicate that most people will choose to test for HIV given the choice sets presented. The most influential attribute related to HIV testing was the cost of testing, and the least influential attribute related to who conducted the test. Youth preferred HIV testing services (with attributes in order of importance) that are free, blood-based testing, available in private/public hospitals or home, for HIV medications to be available in the same location as testing, and a doctor conducts the test.

Table 3.

Preferences for HIV testing service among Nigerian youth using a random parameter logit model (N=270)

| Attribute | Coefficient | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | ||

| - No cost (reference) | 0.75 *** | 0.70 *** |

| - 500 Naira ($USD1.38) | 0.16 *** | 0.23 ** |

| - 1000 Naira ($USD2.76) | −0.21 *** | 0.36 *** |

| - 2000 Naira ($USD5.52) | −0.70 *** | 0.55 *** |

| Location | ||

| - Private hospital (reference) | 0.11 * | 0.61 |

| - Public/government hospital | 0.15 * | 0.04 |

| - Community health centres | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| - Non-profit organizations | −.26 *** | 0.01 |

| - Sexual health clinic | −0.16 ** | 0.01 |

| - Awareness events | 0.08 | 0.41 *** |

| - Pharmacy or chemist | −0.21 ** | 0.21 |

| - Home (i.e. self testing) | 0.16 * | 0.39 ** |

| Mode of testing | ||

| - Venepuncture (reference) | −0.19 *** | 0.38 *** |

| - Blood from finger-prick | 0.24 *** | 0.16 * |

| - Swab from mouth | −0.05 | 0.35 *** |

| Person who conducts test | ||

| - Doctor (reference) | 0.17 *** | 0.54 *** |

| - Nurse | −0.08 * | 0.03 |

| - Trained healthcare volunteer | −0.01 | 0.19 * |

| - Yourself | −0.08 | 0.50 *** |

| Availability of HIV medicine | ||

| - Same location as testing (reference) | 0.19 *** | 0.30 *** |

| - Go to different location | −0.19 *** | 0.30 *** |

| Opt out | −1.59 *** |

p value <0.1

p value <0.05

p value <0.01, AIC/N = 1.706

There was significant heterogeneity among individuals in out-of-pocket costs for HIV testing, testing at home, use of finger-prick testing, and the need to go to a different location to access HIV medications. We explored associations of heterogeneity related to age, gender, education level, sexual or testing behaviors (see Appendix and Table 4). In terms of the likelihood to opt-out of HIV testing, we found that those with secondary education or higher (compared with primary school or lower) and those who never had sex (compared with sexually active) were more likely to opt out of HIV testing (Table S2, S3, S4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with heterogeneous preferences for Nigerian youth

| HIV testing | Subpopulation | Coefficient (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Out of pocket costs | 500 Naira | Younger people | −0.09 (0.05) |

| Men | −0.11 (0.05) | ||

| 1000 Naira | Younger people | 0.10 (0.06) | |

| 2000 Naira | Men | 0.13 (0.06) | |

| Higher than secondary education level | −0.17 (0.06) | ||

| Location of testing | Home testing | Higher than secondary education | 0.41 (0.16) |

| Mode of testing | Finger-prick sample | Sexually active | 0.12 (0.07) |

| Opt-out | Higher than secondary education | 0.16 (0.07) | |

| Sexually active | 0.23 (0.11) | ||

| HIV self testing | |||

| Test quality | Approved by WHO | Ever tested for HIV | 0.07 (0.04) |

| Opt-out | Males | 0.41 (0.07) | |

| Sexually active | −0.30 (0.07) | ||

| Ever Tested for HIV | −0.27 (0.07) |

SE = standard error, WHO = World Health Organization

In the status quo scenario (Cost: 2000 Naira; Location: community health centre; Mode: blood from fingerprick; Person: trained healthcare volunteer; HIV Medicine: available in same location), the predicted uptake was 87.9%. The most preferred combination of attribute levels improved this to 96.6%, whilst the least preferred combination of attribute levels decreased this to 69%.

3.2. Preferences for how to access HIVST kits

Table 5 summarize preferences for HIVST kits. The large negative coefficient for opt-out indicate that most people will choose to test using an HIVST kit given the choice sets presented. The most influential attribute to use an HIVST kit was related to the location to access the kits, and least influential attribute was the type of specimen needed for HIVST. In general, Nigerian youth preferred HIVST kits that are available from community health centers, free, approved by the WHO, oral-based HIVST, include other STI testing and have the option of an online chat.

Table 5.

Preferences for testing for HIV using HIV self-testing kits among Nigerian youth, 2019 (N=234)

| Attribute | Coefficient | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | ||

| - No cost (reference) | 0.29 *** | 0.47 |

| - 500 Naira ($USD1.38) | 0.25 * | 0.02 |

| - 1000 Naira ($USD2.76) | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| - 2000 Naira ($USD5.52) | −0.52 *** | 0.47 *** |

| Test quality | ||

| - Not approved by WHO (ref) | −0.36 *** | 0.38 *** |

| - Approved by WHO | 0.36 *** | 0.38 *** |

| Type of test | ||

| - Blood from finger-prick (ref) | −0.11 *** | 0.02 |

| - Swab from mouth | 0.11 ** | 0.02 |

| Extra items in kit1 | ||

| - Test for other STIs (syphilis/chlam/gono) | 0.32 *** | 0.24 |

| - Pregnancy test, condoms, and/or contraceptive pill | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| - Information about safe sex, HIV and other STIs | −0.28 *** | 0.24 ** |

| - Malaria or TB test | −0.16 | 0.02 |

| Support if test positive | ||

| - Flyer with list of HIV clinics (ref) | −0.25 *** | 0.20 |

| - Online chat with trained counsellors or youth health worker | 0.28 ** | 0.01 |

| - Same-day in-person consultation with trained counsellor or youth health worker | 0.12 | 0.20 ** |

| - Same-day in-person consultation with doctor | −0.15 | 0.02 |

| Location | ||

| - Private hospital (ref) | −0.19 | 0.22 |

| - Public/government hospital | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| - Community health centres | 0.38 *** | 0.20 |

| - Non-profit organizations | −0.49 *** | 0.05 |

| - Sexual health clinic | 0.27 | 0.03 |

| - Awareness events | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| - Pharmacy or chemist | −0.30 * | 0.03 |

| - Online ordering with home delivery | −0.14 | 0.05 |

| Opt out | −1.82 *** |

p value <0.1

p value <0.05

p value <0.01, AIC/N = 1.681

This attribute tested whether youth preferred additional items in the HIVST package they would receive related to: 1) other STI testing; 2) reproductive health related products; 3) extra information; and 4) testing for other diseases.

There was significant heterogeneity among individuals’ preference for out-of-pocket costs related to the HIVST kit, approval by WHO, and information about safe sex, HIV and other STIs. We explored associations of heterogeneity related to age, gender, education level, sexual or testing behaviors (see Appendix and Table 4). In terms of the likelihood to opt-out of choosing to use an HIVST kit, we found that males (compared with females), those who never had sex (compared with sexually active) and those who had never tested for HIV before (compared with those who had previously tested) were more likely to opt out of using an HIVST kit (Table S7, S9, S10).

In the status quo scenario (Cost: 2000 Naira; Test quality: not approved by WHO; Type: Swab from mouth; Extra items: information about safe sex; Support: flyer; Location: non-profit organizations), the predicted uptake was 32.7%. The most preferred combination of attribute levels improved this to 76.8%, and the least preferred combination of attribute levels decreased this to 27.6%.

4). DISCUSSION

Global scale-up of HIVST services could help meet UNAIDS ambitious target for eliminating HIV/AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.(28) HIVST services should be informed by robust testing preference data to ensure that services are desirable to youth. To our best knowledge, this is the first study among Nigerian youth to quantitatively measure preferences for HIV testing and HIV-self testing, and explore how preferences varied according to age, gender, education level, sexual and HIV testing behaviours. We add to the limited health preference literature of HIV testing preferences in youth,(15, 22) and demonstrate how this type of analysis can aid policymakers and health service providers to better understand and incorporate the drivers of choice into their programs so that the uptake of testing services can be optimized.

When presented with all available HIV testing options, we found that youth equally preferred HIV home testing with testing at a public or private hospital (all other attributes being equal). However, the higher educated were more strongly in favour of home testing, possibly because of greater opportunity cost. Whilst youth may prefer a doctor to take the specimen, all other things being equal, we found that the strength of preference for doctor testing (ß=0.17) is similar to the convenience of home (self-testing) (ß=0.16). This underscores the opportunities to promote HIVST among Nigerian youth; other studies have reported that young people favoured home-testing compared to facility-based testing in Malawi, Zimbabwe(22), and South Africa.(10) HIVST can circumvent barriers in facility-based testing identified by youth such as perceived lack of confidentiality and inconvenience.(22) Consistent with other HIV testing preference studies among youth,(15, 22) our findings confirm that youth in general were price-sensitive, and preferred HIV medicines to be available in the same location as testing. These common attributes are important to consider when designing a HIV testing service that targets youth.

When asked about how youth preferred to access HIVST kits, they preferred decentralized locations, such as community health centers, but did not prefer access from not-for-profit organizations or pharmacists/chemists, all other attributes being equal. This is consistent with community-based HIVST distribution models used in Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, which was reported to be acceptable to testers, although their data was not disaggregated by age.(11) Interestingly we found a discrepancy between our qualitative results (showing a preference for blood-based HIVST kits) compared with the results from the DCE (showing a preference for oral-based HIVST kits). Other reviews have also found mixed preferences for the method of testing, even within the same population.(29, 30) Together, the data implies that improving access to both oral- and blood-based HIVST kits could cater for different subpopulation of youth.

We found that youth had a similar preference to pay a small fee up to 500 Naira ($USD1.38) or have free HIVST kits. This was a surprising finding and contrasts with other literature suggesting a strong preference from youth for free testing.(10, 22) This suggests the opportunity for new entrepreneurial models that charge small fees to ensure the sustainability of HIV testing programs. There are several innovative financing models to consider that are untested among youth to improve HIV testing. For example, for Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM), a community-based organization used a refundable deposit system to improve access to HIVST.(31) Another example is to use a pay-it-forward strategy, tested among Chinese MSM to improve testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea.(32) Further research is warranted to explore other sustainable models to finance HIVST distribution programs for youth. It was concerning to observe that males were less likely to use HIVST kits, but this is consistent with extant research reporting poor HIV testing among youth, especially in males.(33) This is compounded by our observation that those who had never tested for HIV were also less likely to use HIVST kits. This underscores the need to focus efforts on improving HIV testing among young males and normalizing HIV testing among all youth.

In addition, participants in the study preferred HIVST kits that were integrated with other STI testing. This is a new finding that has not been explored in other health preference research of HIVST in youth.(10, 22) Our observation might reflect an aversion of Nigerian youth to attend sexual health clinics, and would need further exploration to understand this finding. Currently, simultaneous HIV and syphilis self-testing using the same diagnostic platform is possible,(34) however rapid testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea is still unavailable in resource-limited settings.(35) Integrating HIV and STI testing increases economies of scope as the same individuals at risk for HIV are also at risk for other STIs. Improved testing and timely treatment for both HIV and other STIs among youth would reduce the economic and health burden from these infections.(36)

Altogether, there are several strengths to this study. This is the first health preference study in Nigeria that evaluated HIV testing and HIVST among youth. We use a relatively novel method in HIV research (i.e. DCE) to elicit preferences to measure how participants trade-off between attributes, mimicking real life decision-making. We explored heterogeneity using RPL models with interaction effects, providing a more nuanced understanding of preferences that could differ according to individual characteristics. These findings are pertinent to create demand for and increase HIVST among young people in Nigeria in line with the goals of the 2019 Nigeria operational guidelines for the delivery of HIVST. The understanding of youth preferences may inform ways in which the government and programs develop tailored HIVST delivery services to meet unique needs of the different youth segments.

Our study should be read in light of some limitations. First, we used venue-based sampling from one region of Nigeria, albeit including Lagos as the most populous city, so our findings may not be generalizable to all Nigerian youth. In addition, males were underrepresented in our survey; we suggest that future research may consider quota sampling to improve generalizability. Second, there is potential sampling bias as all participants had to be literate to understand the survey. Third, though 3% of the population did not identify as heterosexual, the numbers were too small to accurately determine the preferences of sexual minorities. A future study to focus on the preferences of sexual minorities who have a higher risk for HIV is worthwhile. Fourth, most youth had not used HIVST before so preferences may change after personal use. Fifth, besides face validity, we did not perform any other validity tests. Last, there remained significant unexplained heterogeneity in preferences, providing guidance for areas of focus in future qualitative interviews to further explore and better understand the underlying drivers of choice for HIV testing.

5). CONCLUSION

There is a need to incorporate youth preferences into the global scale-up of HIV testing services. Our data suggest that male youth were less likely to choose to test for HIV or use HIVST kits, cost was the most important attribute for Nigerian youth to test for HIV, and both cost and the location of accessing HIVST were the most important attributes to use HIVST kits.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Nigerian youth equally preferred to test for HIV either in public/private hospitals or at home (i.e. self-testing), all other attributes being equal.

Youth preferred HIVST kits that are accessed from community health centers, free, quality-assured, integrated with other sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, able to have online chat and oral-based.

Most youths would choose to use a HIVST kit if their preferences can be incorporated, although males were less likely

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research for their support of the project and the young people who participated.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), grant number: UG3HD096929. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

All authors state that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approvals for the study were granted by the Saint Louis University and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research Institutional Review Boards.

Consent to participate

Written informed consents were obtained from all the study participants. This is in accordance to the Nigerian guidelines for sexual and reproductive health research, such that young people who are 13 years and over can provide informed consent for sexual and reproductive health research.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript and approved this for publication.

Availability of data and material

All relevant data is presented in the manuscript. Further data may be accessed by writing to the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable

6) REFERENCES

- 1.Avert. Young people, HIV and AIDS [Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/key-affected-populations/young-people.

- 2.Allen E, Gordon A, Krakower D, Hsu K HIV preexposure prophylaxis for adolescents and young adults. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(4):399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS data 2020. [Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/unaids-data.

- 4.Oladele EA, Badejo OA, Obanubi C, Okechukwu EF, James E, Owhonda G, et al. Bridging the HIV treatment gap in Nigeria: examining community antiretroviral treatment models. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(4):e25108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS. Nigeria [Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria.

- 6.Somefun OD, Wandera SO, Odimegwu C Media Exposure and HIV Testing Among Youth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence From Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). SAGE Open. 2019;9(2):2158244019851551. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demographic N Health Survey 2013. National Population Commission (NPC)[Nigeria] and ICF International. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification [Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/vct/hiv-self-testing-guidelines/en/.

- 9.Global AIDS Monitoring (UNAIDS/WHO/UNICEF) and WHO Country Intelligence Tool, 2019. Status of HIV self-testing (HIVST) in national policies (situation as of July 2019). [Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/self-testing/HIVST-policy_map-jul2019-a.png?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchwood TD, Selin A, Pettifor A, Lippman SA, Gilmore H, Kimaru L, et al. HIV self-testing: South African young adults' recommendations for ease of use, test kit contents, accessibility, and supportive resources. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatzold K, Gudukeya S, Mutseta MN, Chilongosi R, Nalubamba M, Nkhoma C, et al. HIV self-testing: breaking the barriers to uptake of testing among men and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, experiences from STAR demonstration projects in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 1:e25244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancaster K A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy. 1966;74(2):132–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibanda EL, d'Elbee M, Maringwa G, Ruhode N, Tumushime M, Madanhire C, et al. Applying user preferences to optimize the contribution of HIV self-testing to reaching the "first 90" target of UNAIDS Fast-track strategy: results from discrete choice experiments in Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 1:e25245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostermann J, Njau B, Mtuy T, Brown DS, Muhlbacher A, Thielman N One size does not fit all: HIV testing preferences differ among high-risk groups in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2015;27(5):595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaels-Igbokwe C, Lagarde M, Cairns J, Integra I, Terris-Prestholt F Designing a package of sexual and reproductive health and HIV outreach services to meet the heterogeneous preferences of young people in Malawi: results from a discrete choice experiment. Health Econ Rev. 2015;5:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bristow CC, Kojima N, Lee SJ, Leon SR, Ramos LB, Konda KA, et al. HIV and syphilis testing preferences among men who have sex with men and among transgender women in Lima, Peru. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss M, George G, Lansdell E, Mantell JE, Govender K, Romo M, et al. HIV testing preferences among long distance truck drivers in Kenya: a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Care. 2018;30(1):72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanolini A, Chipungu J, Vinikoor MJ, Bosomprah S, Mafwenko M, Holmes CB, et al. HIV Self-Testing in Lusaka Province, Zambia: Acceptability, Comprehension of Testing Instructions, and Individual Preferences for Self-Test Kit Distribution in a Population-Based Sample of Adolescents and Adults. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018;34(3):254–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss M, George GL, Rhodes BD Determining Preferences Related to HIV Counselling and Testing Services Among High School Learners in KwaZulu-Natal: A Discrete Choice Experiment. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(1):64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss M, George G, Mantell JE, Romo ML, Mwai E, Nyaga EN, et al. Stated and revealed preferences for HIV testing: can oral self-testing help to increase uptake amongst truck drivers in Kenya? BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostermann J, Njau B, Brown DS, Muhlbacher A, Thielman N Heterogeneous HIV testing preferences in an urban setting in Tanzania: results from a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Indravudh PP, Sibanda EL, d'Elbee M, Kumwenda MK, Ringwald B, Maringwa G, et al. 'I will choose when to test, where I want to test': investigating young people's preferences for HIV self-testing in Malawi and Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2017;31 Suppl 3:S203–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan SW, Durvasula M, Ong JJ, Liu C, Tang W, Fu H, et al. No Place Like Home? Disentangling Preferences for HIV Testing Locations and Services Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in China. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(4):847–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B How to do (or not to do) … Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(2):151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbajabiamila T, Ezechi O, Nwaozuru U, Ong JJ, Idigbe I, et al. Young people's preferences for HIV self-testing services in Nigeria: a qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bech M, Gyrd-Hansen D Effects coding in discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2005;14(10):1079–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH Applied Choice Analysis. 2 ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong V, Jenkins E, Ford N, Ingold H To thine own test be true: HIV self-testing and the global reach for the undiagnosed. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 1:e25256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Indravudh PP, Choko AT, Corbett EL Scaling up HIV self-testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of technology, policy and evidence. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31(1):14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens DR, Vrana CJ, Dlin RE, Korte JE A Global Review of HIV Self-testing: Themes and Implications. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(2):497–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong F, Tang W, Cheng W, Lin P, Wu Q, Cai Y, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a social entrepreneurship testing model to promote HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 2017;18(5):376–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li KT, Tang W, Wu D, Huang W, Wu F, Lee A, et al. Pay-it-forward strategy to enhance uptake of dual gonorrhea and chlamydia testing among men who have sex with men in China: a pragmatic, quasi-experimental study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ajayi AI, Awopegba OE, Adeagbo OA, Ushie BA Low coverage of HIV testing among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria: Implication for achieving the UNAIDS first 95. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Prequalification of In Vitro Diagnostics Public Report. Product: First response HIV1+2/syphilis Combo Card test [Available from: https://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/evaluations/pq-list/190625_pqdx_0364_010_00_final_pqpr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. The Point-of-care Diagnostic Landscape for STIs October 2019. [Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/rtis/pocts/en/.

- 36.Chesson HW, Mayaud P, Aral SO Sexually Transmitted Infections: Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Prevention. In: rd, Holmes KK, Bertozzi S, Bloom BR, Jha P, editors. Major Infectious Diseases. Washington (DC)2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.