Abstract

Quantitative evaluation of analgesic efficacy improves understanding of the antinociceptive mechanisms of new analgesics and provides important guidance for their development. Lappaconitine (LA), a potent analgesic drug extracted from the root of natural Aconitum species, has been clinically used for years because of its effective analgesic and non-addictive properties. However, being limited to ethological experiments, previous studies have mainly investigated the analgesic effect of LA at the behavioral level, and the associated antinociceptive mechanisms are still unclear. In this study, electrocorticogram (ECoG) technology was used to investigate the analgesic effects of two homologous derivatives of LA, Lappaconitine hydrobromide (LAH) and Lappaconitine trifluoroacetate (LAF), on Sprague-Dawley rats subjected to nociceptive laser stimuli, and to further explore their antinociceptive mechanisms. We found that both LAH and LAF were effective in reducing pain, as manifested in the remarkable reduction of nocifensive behaviors and laser-evoked potentials (LEPs) amplitudes (N2 and P2 waves, and gamma-band oscillations), and significantly prolonged latencies of the LEP-N2/P2. These changes in LEPs reflect the similar antinociceptive mechanism of LAF and LAH, i.e., inhibition of the fast signaling pathways. In addition, there were no changes in the auditory-evoked potential (AEP-N1 component) before and after LAF or LAH treatment, suggesting that neither drug had a central anesthetic effect. Importantly, compared with LAH, LAF was superior in its effects on the magnitudes of gamma-band oscillations and the resting-state spectra, which may be associated with their differences in the octanol/water partition coefficient, degree of dissociation, toxicity, and glycine receptor regulation. Altogether, jointly applying nociceptive laser stimuli and ECoG recordings in rats, we provide solid neural evidence for the analgesic efficacy and antinociceptive mechanisms of derivatives of LA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12264-021-00774-w.

Keywords: Electrocorticogram, Analgesic effect, Lappaconitine derivatives, Antinociceptive mechanisms, Laser-evoked potentials

Introduction

Pain is one of the most common clinical symptoms [1, 21]. Millions of people around the world suffer from various kinds of pain, and some even become suicidal because of the suffering from long-term pain and the unmet medical needs [2–4, 16]. Currently-available analgesics, and in particular opioids, are normally accompanied by many side-effects, such as addiction, lethargy, mental fog, and nausea [5, 19]. The long-term use and overuse of analgesics has a negative impact on the health-related quality of life of pain patients [6, 46]. Therefore, the development of effective and non-addictive analgesics is needed.

Many successful analgesics, such as morphine, triptolide, and menthol, have been derived from certain plants [7, 53]. Among them, Lappaconitine (LA), a potent analgesic drug extracted from the root of Aconitum sinomontanum Nakai, and its representative derivative (LA hydrobromide, LAH), prepared for the first time by our group, has been in clinical use for many years due to its effective analgesic action and non-addictive properties [8–11, 51]. In our recent study, LA trifluoroacetate (LAF), a new derivative of LA, was obtained by introducing fluorine-containing group into LA [12, 48]. Compared with LAH, LAF has demonstrated some advantages, such as lower toxicity, higher solubility, and a longer half-life. However, previous studies on the analgesic effects of the derivatives of LA have been limited to behavioral assessments in ethological experiments. The neural mechanisms associated with their analgesic effects have rarely been investigated based on in vivo electrophysiological assessment [13, 14].

Self-reports and behavioral assessments are the traditional gold standards for the evaluation of pain perception in humans and animals, respectively [15, 16]. However, since pain is a subjective first-person experience, individual differences are unavoidable [17]. Coupled with the behavioral assessments, the availability of a physiology-based and objective evaluation of the analgesic effects would not only be conducive to a more accurate evaluation of drug performance but also helpful to promote the understanding of the neural mechanisms associated with the analgesic effects [18, 19].

Cortical responses elicited by nociceptive laser stimuli that selectively excite cutaneous nociceptors and elicit pure painful perception [20], are commonly used to investigate pain-specific neural processing in both humans and animals [21, 24]. Compared to electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings that collect neural activity at the surface of the scalp, brain responses sampled using epidural electrocorticographic (ECoG) recordings from electrodes placed directly on the exposed surface of the animal cortex are more robust to various artifacts. Based on these technical characteristics, EEG and ECoG signals may offer a practical technology for assessing acute and chronic pain. As the sampled brain responses are characterized by a high signal-to-noise ratio, the combination of ECoG technology and nociceptive laser stimuli provide more accurate objective evaluation of pain perception and analgesic effects [22].

In this study, we delivered nociceptive laser stimuli to Sprague-Dawley rats, and recorded laser-evoked potentials (LEPs) using epidural ECoG to explore the analgesic effects and neural mechanisms of LAH and LAF. In addition, we delivered auditory stimuli to the rats to elicit auditory-evoked potentials (AEPs), which were used to verify the specific effect of both LAH and LAF on the nociceptive system.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and Subjects

LAH and LAF were synthesized in the laboratory based on our previous studies [12, 23]. The preparation, purification, and characterization of LAH and LAF were performed in the College of Life Science, Northwest Normal University (Lanzhou, China). Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 250 and 300 g were used for the experiments. They were housed in separate cages in a humidity- and temperature-controlled environment under a 12-h day-night cycle (lights on from 19:00 to 07:00) and received food and water ad libitum. The experiments were performed in the CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology (Beijing, China). All surgical and experimental procedures adhered to the guidelines for animal experimentation and were approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China).

Surgical Procedures

Throughout the surgery, rats were anesthetized with 2%–3% isoflurane (v/v) at a flow rate of 0.5 L/min. During the surgery, the head was secured in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). As previously described, after the dorsal aspect of the scalp was shaved, the skull was exposed by a midline incision [24]. Fourteen holes were drilled into the skull based on the pre-defined locations on the standard stereotaxic reference system [25]. Stainless-steel screws (diameter, 1 mm) were inserted into the holes without penetrating the underlying dura mater. Twelve of the screws acted as active electrodes, and their coordinates with respect to bregma were as Table 1. The reference and ground electrodes were respectively placed at 2 and 4 mm caudal to lambda, on the midline. The wires from the electrodes were held together with a connector module fixed on the skull with dental cement. To prevent post-surgical infection, rats were injected with penicillin (50,000 U, i.p.) immediately after the surgery. Then, they were kept in individual cages for at least 7 days before ECoG recording.

Table 1.

The electrodes coordinates with respect to bregma (mm)

| Electrodes | X axis | Y axis |

|---|---|---|

| FL1 | − 1.5 | 4.5 |

| FR1 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| FL2 | − 1.5 | 1.5 |

| FR2 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| LFL | − 4.5 | 0 |

| RFR | 4.5 | 0 |

| PL1 | − 1.5 | − 1.5 |

| PR1 | 1.5 | − 1.5 |

| LPL | − 4.5 | − 3 |

| RPR | 4.5 | − 3 |

| PL2 | − 1.5 | − 4.5 |

| PR2 | 1.5 | − 4.5 |

Positive X and Y axis values indicate right and anterior locations, respectively.

Experimental Paradigm

Sensory Stimuli

Nociceptive stimuli were generated using an infrared neodymium yttrium aluminum perovskite (Nd:YAP) laser with a wavelength of 1.34 µm (DEKA Stimul 1340, Italy). Nd:YAP laser pulses directly activate nociceptive terminals in the most superficial skin layers [21, 26]. The laser beam was transmitted via an optic fiber, and its diameter was set at ~ 4 mm (~ 13 mm2) by focusing lenses. The stimulus intensity was set at 3.00 J, and the pulse duration was 4 ms. A He-Ne laser pointed to the stimulated area on the rat’s forepaw. The interstimulus interval was never shorter than 40 s. To avoid activation of the auditory system by the laser-generated ultrasound [27], ECoG data were recorded during ongoing white noise. This procedure allowed selective recording of LEPs related to the activation of the nociceptive system [24].

Auditory stimuli were brief, 5000-Hz pure tones generated by a buzzer positioned at the top of the ECoG recording cage. The intensity was set at 80 dB, the duration was 30 ms, and the interstimulus interval was never shorter than 30 s.

To ensure that the recorded neural activity was minimally contaminated by movement-related artifacts, laser and auditory stimuli were manually delivered when the rats were spontaneously still.

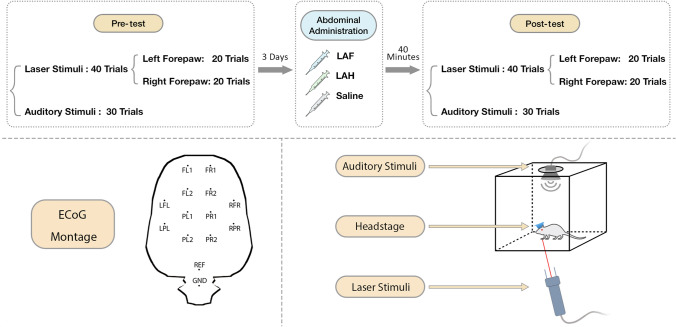

Drug Administration and Experimental Design

All rats were divided into three groups, and in each group (n = 8), the rats were given either LAH, LAF, or normal saline via intraperitoneal injection (a single dose of 6 mg/kg, normal saline as solvent). As illustrated in Fig. 1, the experiment consisted of four recording blocks: two blocks before (Pre-test) and two blocks after drug administration (Post-test). The two pairs of blocks were identical except for the order of laser and auditory stimuli: laser before sound in one block, and sound before laser in the other. To minimize the influence of sensory stimuli before drug administration on brain responses after drug administration, rats were rested in individual cages for at least 3 days between Pre-test and Post-test blocks. In the Post-test blocks, ECoG recordings were started 40 min after the drug injection, which was based the action time of the drugs assessed in preliminary experiments (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental paradigm of ECoG experiments.

In each block, 40 laser stimuli were delivered to the left and right forepaws (20 to each forepaw) and 30 auditory stimuli. To avoid nociceptor fatigue or sensitization, the target point was moved after each laser stimulus [24, 28].

ECoG Recording

ECoG data were recorded at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz using a wireless amplifier (Multi Channel Systems MCS Gmbh, Reutlingen, Germany). Rats were placed in the recording cage (30 × 30 × 30 cm3) for 1 h before ECoG recording to adapt to the recording environment. During data collection, rats could freely move in the cage. The floor of the cage had a regular series of holes (~ 5 mm in diameter), through which the laser pulses were delivered to the rats’ forepaws. At the top of the cage was a large hole (15 cm in diameter) where the buzzer was placed. Rats were video-recorded throughout the experiment to identify the nocifensive behaviors elicited by the laser stimuli. Stimulus-induced nociceptive behaviors were quantified after each laser stimulus using the following criteria: score 0, no movement, score 1, head-turning (including elevating or shaking the head;); score 2, flinching (a small abrupt body-jerking movement;); score 3, withdrawal (paw withdrawal from the laser stimulus;); and score 4, licking and whole body movement [24].

ECoG Data Analysis

Data Pre-processing and Time-Domain Analysis

ECoG data were pre-processed using EEGLAB, an open source toolbox running in the MatLab environment [29, 37, 41]. Continuous ECoG data were first down-sampled to 1000 Hz, then bandpass-filtered from 1 to 100 Hz and notch-filtered from 49 to 51 Hz. ECoG epochs were extracted using a window analysis time of 3000 ms (1000 ms before and 2000 ms after the stimulus), and baseline-corrected using the pre-stimulus interval. Epochs contaminated by gross artifacts (exceeding ± 500 µV at any time point and at any electrode) were automatically rejected [30, 31].

Single-trial LEP and AEP waveforms were averaged across trials for each rat and experimental condition (as well as the site for laser stimuli). Peak latencies and amplitudes of the N2 and P2 waves in LEPs [34, 36], as well as the N1 wave in AEPs [32], were measured from single-subject average waveforms. According to previous studies [20, 33], the N2 and P2 waves in LEPs are optimally detected from four central electrodes (FL2, FR2, PL1, and PR1) and two frontal electrodes (FL1 and FR1), respectively. Due to the central electrodes contributed the most both in LEP-N2 and AEP-N1, the four central electrodes (FL2, FR2, PL1, and PR1) were also used to measure the parameters of the N1 wave in AEPs. Single-subject average waveforms were subsequently averaged to obtain group-level LEP and AEP waveforms. Group-level scalp topographies of these waves were computed by spline interpolation. The boundaries of scalp topographies were determined based on a stereotaxic atlas [34].

Time-Frequency Analysis

Time-frequency distributions (TFDs) of single-trial ECoG responses were calculated using a windowed Fourier transform with a 200-ms Hanning window [35]. This yielded, for each trial, a complex time-frequency spectral estimate F(t, f) at each time-frequency point, extending from − 1000 to 2000 ms (in steps of 1 ms) in time, and from 1 to 100 Hz (in steps of 1 Hz) in frequency [36]. The spectrogram, P(t, fz) = |F(t, f)|2, represents the power spectral density as a joint function of time and frequency at each time-frequency point [37]. For each rat, session, and experimental condition (as well as site for laser stimulation), single-trial TFDs were averaged across trials and normalized using the power spectral density in the baseline interval (− 800 to − 200 ms relative to stimulus onset) for each frequency. To quantify gamma-band oscillations elicited by nociceptive laser stimuli (gamma event-related synchronization; γ-ERS), a region of interest ranging from 150 to 350 ms and from 51 to 99 Hz was defined to measure the magnitude of γ-ERS from single-subject baseline-corrected TFDs [26, 36, 38, 63]. Single-subject baseline-corrected TFDs were subsequently averaged to obtain group-level TFDs.

Power Spectral Analyses of Resting-State ECoG Signals

Pre-stimulus ECoG signals were extracted from a time window ranging from − 3000 to − 2000 ms relative to the laser stimulus. For each rat, session, and experimental condition, pre-stimulus ECoG signals were transformed to the frequency domain using the fast Fourier transform, yielding a power spectrum ranging from 1 to 99 Hz for each electrode. Single-subject power spectra were subsequently averaged to obtain group-level ECoG spectra.

Statistical Analysis

To assess the analgesic effects of different drugs, two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed with a between-subject factor (“drug”: LAH, LAF, and Saline) and a within-subject factor (“test”: Pre-test and Post-test). The analyses were performed on all extracted measures: nocifensive behavior scores, latencies and amplitudes of the N2 and P2 waves in LEPs as well as the N1 wave in AEPs, magnitudes of γ-ERS, and resting-state spectral power. When the interaction between two factors or any of the main effects was significant, post hoc independent-sample t-tests were applied to compare different drugs separately for Pre-test and Post-test. In addition, post hoc paired-sample t-tests were used to compare Pre-test and Post-test separately for each drug. In the meantime, point-by-point two-way ANOVAs with the same factors were also performed on the time-domain waveforms (− 0.5 s to 1.5 s of LEP waveforms). Point-by-point paired sample t-tests were performed on the LEP–N2/P2, AEP–N1, and frequency-domain spectra (i.e., resting-state power spectra). To account for multiple comparisons across time- or frequency-points, a false discovery rate (FDR) procedure was used to correct the significance level (P value). All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 7.03, except for the point-by-point analyses that were carried out using MatLab.

Results

Behavioral Results

The proportions of nociceptive behavioral scores induced by laser stimulation on the forepaws of rats, and the statistical results are shown in Fig. 2 and listed in Table S1, respectively. They showed that the scores of pain-related behaviors were significantly affected by intraperitoneal administration of LAF and LAH. The proportional values of the nociceptive behavioral scores showed differences among the three groups. In the Pre-test, all three groups showed similar proportional values in response to the laser stimulus, mainly with a high percentage of score 4 (~ 70% trials). But for the Post-test, the LAF and LAH groups showed a lower percentage of score 4 (3%–4% of trials with LAF and 8%–9% with LAH), whereas the Saline group maintained a high percentage at this score (~ 70%–72% of trials). In addition, the LAF and LAH groups showed a lower proportion of scores 3 and 4 (~ 15%–20%) and higher proportion of scores 0 and 1 (> 50%) in the Post-test, indicating that LAF and LAH administration significantly reduced the behavioral scores. Statistically, the mean scores were significantly modulated by the main effects of “drug” and “test” and their interactions in both left and right paw behavioral scores (Fig. 2 and Table S1). For the left paw: “drug”, F2,42 = 91.01, P < 0.0001; “test ”, F1,42 = 341.70, P < 0.0001, “interaction”, F2,42 = 84.71, P < 0.0001. For the right paw: “drug”, F2,42 = 109.00, P < 0.0001; “test”, F1,42 = 438.60, P < 0.0001, “interaction”, F2, 42 = 106.40, P < 0.0001. The post hoc t-tests indicated that both LAF and LAH groups had lower behavioral scores than the saline group in the Post-test (P < 0.0001, both corrected), but not in the Pre-test, suggesting that both drugs had a significant analgesic effect against laser stimulation, which was not affected by the stimulus location.

Fig. 2.

Effects of laser stimulation on the behavioral scores of rats before and after treatment. Upper panels: pie charts showing the proportions of behavioral scores (0–4) with laser stimulation in the LAF, LAH, and Saline groups. Lower panels: histograms showing behavioral scores (*P < 0.05, **P <0.01 ***P < 0.001, Pre-test vs Post-test for the same group or between groups, two-way ANOVA and post hoc t-tests.

Time Domain Results

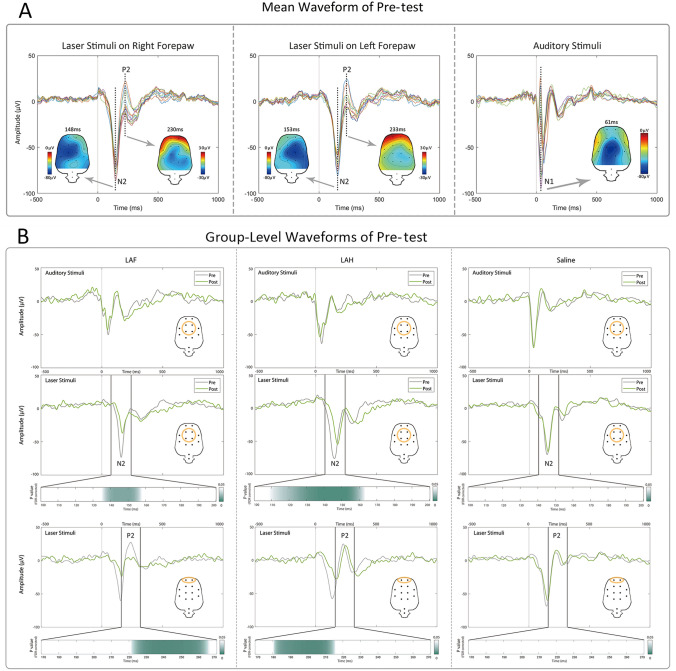

The group-level averaged waveforms of responses to laser and auditory stimuli in the Pre-test are shown in Fig. 3A. Laser stimuli evoked a clear negative wave (N2) followed by a clear positive wave (P2), while auditory stimuli evoked a clear negative wave (N1). We found that the amplitudes of the N2/P2 components were modulated by both of the factors “test” and “drug” between 100 and 500 ms at all electrodes (Fig. S2). In detail, the significant results at 100–300 ms corresponded to the LEP-N2 component at the central electrodes (FL2, FR2, PL1, and PR1), and the LEP-P2 component at the frontal electrodes (FL1, FR1). The group-level average LEP and AEP waveforms from central and frontal electrodes in the Pre-test and Post-test, together with point-by-point paired-sample t-tests in the time domain are shown in Fig. 3B, and the statistical comparisons for the latency and amplitude of AEP-N1, LEP-N2, and LEP-P2 are shown in Fig. 4, Table S2, and Table S3. There were no differences in the latency and amplitude of the AEP-N1 component in the LAF, LAH, and Saline groups (Figs. 3B, 4C, F, Tables S2 and S3). Compared with the Pre-test, the Post-test of the LAF and LAH groups showed significantly longer latencies and decreased amplitudes of the N2 and P2 components (Fig. 3B). The LEP-N2 and LEP-P2 latencies both had a significant “drug” effect (F2,42 = 10.67, P = 0.0002 and F2,42 = 6.53, P = 0.003), and “test” effect (F1,42 = 29.54, P < 0.0001 and F1,42 = 8.55, P = 0.006, respectively, Table S2). There were also significant interaction effects for N2 latency (F2,42 = 4.045, P = 0.025, Table S2), and P2 amplitude (F2,42 = 11.20, P = 0.0001, Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Mean waveform of Pre-test and Group-level waveforms of Pre- and Post-test for the amplitude and latency of LEP–N2/P2 and AEP–N1 components. (A) Pre-test waveforms of group-level LEPs and AEPs recorded from all 12 electrodes (reference electrode 2 mm caudal to lambda; colors indicate averages from all animals at each electrode). (B) Group-level LEP and AEP waveforms in Pre-test and Post-test, and point-by-point paired sample t-tests on LEP time-domain waveforms. Among them, the response amplitude to laser stimulation is the average of all trials of the left and right forepaws [green: the significant portion of the Pre-test to the Post-test point-by-point paired sample t-test (in steps of 1 ms) for LEP-N2 (100–200 ms) and LEP-P2 (170–270 ms) after stimulation (p values are FDR-corrected)].

Fig. 4.

Two-way ANOVA and post hoc t-tests results for the amplitude and latency of LEP–N2/P2 and AEP–N1 components (each column represents the mean value, and the bar represents SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, post hoc t-tests; values are listed in Table S5 in supplementary information).

The post hoc t-tests showed no significant difference of N2 and P2 amplitude and latency between the three groups in the Pre-test, while the N2 latencies in the LAF and LAH groups were longer in the Post-test (P = 0.005 and 0.0004 respectively, Fig. 4D and Table S2). In the Post-test, the N2 latencies in the LAF and LAH groups were also longer than in the Saline group (P = 0.0003 and 0.007 respectively, Fig. 4D and Table S2), while the P2 amplitude in the LAF group was strikingly higher than that in the Saline group (P = 0.001, Fig. 4B and Table S3). Furthermore, the P2 amplitude was smaller and its latency was longer in the Post-test LAF group than in the LAH group (P = 0.002 and 0.013, respectively, Figs. 4B, E, Tables S2 and S3).

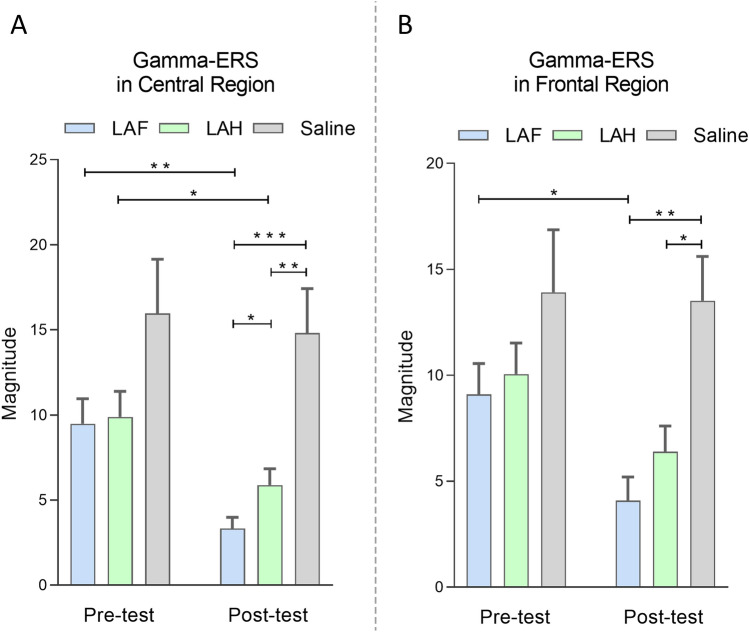

Time-Frequency Distribution Results

In the time-frequency domain, γ-ERS reflects the pain sensitivity of different individuals [38, 39]. Hence, we analyzed γ-ERS in the central region (γCR, extracted from FL2, FR2, PL1, and PR1) and in the frontal region (γFR, extracted from FL1 and FR1) (Figs. 5 and 6, Table S4). The magnitude of both γCR and γFR were modulated by the main effects of “drug”, F2,42 = 12.21, P < 0.0001 and F2,42 = 8.33, P = 0.001, as well as “test”, F1,42 = 5.63, P = 0.022 and F2,42 = 8.33, P = 0.001, respectively. Post hoc t-tests showed that both γCR and γFR in the Post-test were strikingly lower than in the Pre-test for LAF (P = 0.017 and 0.044 respectively, Fig. 6, Table S4), while only γCR showed a significant difference for LAH (P = 0.015, Fig. 6A, Table S4). Besides, in the Post-test, the significance of both γCR and γFR for the LAF and LAH groups were remarkably higher than in the Saline group (P = 0.001 and 0.007 in γCR, Fig. 6A; P = 0.009 and 0.011 respectively in γFR, Fig. 6B, Table S4). In addition, the γCR of LAF in the Post-test was more significant than that of LAH (P = 0.046, Fig. 6A, Table S4).

Fig. 5.

Time-frequency distributions (TFDs) of group-averaged ECoG responses elicited by nociceptive laser stimulation. Displayed signals were measured from the four central electrodes (FL2, FR2, PL1, and PR1) and the two frontal electrodes (FL1 and FR1). The color scale represents the increase or decrease of oscillation magnitude relative to the pre-stimulus interval (800–100 ms). The region of interest ranging from 150 to 350 ms and 70–99 Hz after stimulation is highlighted with solid red lines. Baseline correction used the ΔE/Ebaseline method.

Fig. 6.

Two-way ANOVA and post hoc t-tests results for γ-ERS in the central and frontal regions in time-frequency distribution (each column represents the mean value, and the bar represents the SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, post hoc t-tests; values are listed in Table S6 in supplementary information).

Resting-State Spectra

Resting-state ECoG, in which electrical signals are generated spontaneously, has been extensively studied and used to evaluate individual cerebral states [40]. Changes in resting ECoG are considered to reflect the regulatory effect of internal brain functions and serve as neurophysiological indicators in various brain disorders [41]. Resting EEG has been reported to occur predominantly in the frontal lobe [42], and this was clearly present in all scalp topographies of the LAF, LAH, and Saline groups in this experiment (Fig. S3). Therefore, the four electrodes of the frontal lobe (FL1, FR1, FL2, and FR2) were analyzed as representative of resting-state spectra (Fig. 7). We found that both LAF and LAH groups showed an increase at low frequencies in the Post-test, especially at 5 Hz in the LAF group, and at 12 and 28 Hz in the LAH group. In addition, the LAH group showed a significant decrease in the high gamma band, especially between 82 and 98 Hz. The resting-state results suggested that both drugs affect the cerebral state, and LAH has a greater impact on the resting-state ECoG than LAF.

Fig. 7.

Resting state ECoG spectra and point-by-point t-tests in rats before and after drug administration. Displayed signals are from the FL1, FR1, FL2, and FR2 electrodes. Point-by-point t-tests are the matching sample t-tests of the results of Pre-test and Post-test from the average values of the four electrodes from 1 to 99 Hz (step size, 1 Hz), and are FDR-corrected.

Discussion

Quantitative evaluation of the efficacy of analgesics is a necessary means of assessing drug performance, and provides guidance for the rational management of pain. Lacking quantifiable indicators to assess their analgesic effect objectively and reveal the potential mechanisms, the traditional evaluation of new analgesics has mainly focused on animal behaviors. EEG technology has been widely used in chronic pain patients, and obtained different neural markers for pain relief [43, 44]. In this study, ECoG technology was applied to quantitatively assess the efficacy of the homologous analgesic derivatives LAH and LAF, and the changes of spontaneous cerebral activity and nociceptive evoked potentials reflected the similarities and differences of these derivatives in rats. The results showed that both LAF and LAH caused: (1) a significant reduction of the behavioral scores induced by laser stimulation (Fig. 2 and Table S1); (2) a significant increase in the pain threshold of thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. S1); (3) no change in the AEP-N1 component, and a significant reduction of the amplitude and increase of the latency of the LEP-N2/P2 components (Figs. 3 and 4, Tables S2 and S3); and (4) a reduction of γ-ERS in the time-frequency distribution (Figs. 5 and 6, Table S4), and an increase at low frequencies in the resting-state spectra (Fig. 7). Besides, the LAF had stronger effects on LEP-P2 and γCR, but had less influence on the resting-state spectra (Figs. 4, 6, and 7, Tables S2, S3, and S4). These neurophysiological characteristics together may help to understand the analgesic mechanisms of LAF and LAH.

Changes in Laser Evoked Potentials Reflect Similar Antinociceptive Mechanisms of Actions of LAF and LAH

The average latencies of LEP-N2/P2 were lengthened and the amplitude of LEP-P2 declined significantly after intraperitoneal injection of LAF and LAH (Fig. 4). The LEP-N2 is speculated to be generated bilaterally in secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) and the insula, and LEP-P2 is mainly generated in the anterior cingulate cortex, which is a key part of the emotional response to pain [45, 46]. All these regions receive information from the spinothalamic tract (STT). Similar changes induced by the two drugs in the LEPs suggest that they influence the STT to suppress the transmission of nociceptive information, which may be related to the possible analgesic mechanism of their parent LA. LAF and LAH were prepared by the reaction of CF3COOH and HBr with lappaconitine, respectively, and can be dissociated into LA cation and CF3COO (for LAF) or Br anion (for LAH) in aqueous solution (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

The reaction and dissociation equations of LAF and LAH.

As for the specific mechanism of action of LA, previous research has reported several possible analgesic mechanisms such as inhibition of Na+ channels [47, 48] (e.g., Nav1.7 [49]) or substance P [50]. Meanwhile, recently Sun et al. showed that LA plays an analgesic role mainly by stimulating dynorphin A in spinal microglia rather than blocking Na+ channels [51]. All these mechanisms can be sorted into two classes. One is to affect fast signal pathways such as those using amino-acidergic neurons and ion channels, and another is to have effects on slower signal pathways such as those using neuropeptides. According to the change of N2 latency, the conduction of pain information became slower after injection of LAF or LAH. Therefore, it can be presumed that LA inhibited the fast pathway such as via Na+ channels [52]. From the AEP results, no changes were found before and after drug administration, indicating that neither drug has an anesthetic effect on the central nervous system [62]. It has been reported that the C-4 of the O-aromatic esters of lappaconitine have the highest local anesthetic activity with duration even greater than cocaine [53]. Besides, the effects on P2 amplitude and latency of LAF in the Post-test were greater than those of LAH. The source of P2 is mainly regarded to be the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with negative emotion [46]. The differences in the P2 component indicate that LAF has a better effect on the emotional response to pain, which is a potential advantage.

Thermal Hyperalgesia and Laser-Induced γ-ERS Reflect Different Degrees of Antinociception by LAF and LAH

Although both LAF and LAH had significant analgesic effects against laser stimulation, there were several differences between the two drugs: (1) the thermal hyperalgesia results showed that the analgesic effect of LAF occurred earlier than that of LAH (Fig. S1); (2) the γ-ERS of the LAF group in the Post-test was less than that of the LAH group (p <0.05, Figs. 5, 6); and (3) the LAF group showed an overall decrease in the low γ-band compared with the LAH group (Fig. 7).

The superior solubility of LAF may result in its acting more rapidly than LAH. As one of the important physical and chemical properties of weakly acidic and weakly basic compounds, the dissociation constant (pKa) determines the solubility and absorption of drug molecules. According to the pKa (HBr) = –9 and pKa (CF3COOH) = 0.25 [54], LAF could release much more [LA]+, which would ensure a high plasma concentration of LA after injection, and therefore would be conducive to its analgesic activity. Furthermore, the octanol/water partition coefficient, logP, is generally considered to be one of the principal parameters to evaluate the lipophilicity of chemical compounds that, to a large degree, determines the quantitative structure-activity relationship of drugs [55]. From our previous work, the logP of LAF and LAH were 0.96 and 0.48, respectively [12], which means that LAF has a higher permeability and bioavailability, which may also be a major reason why LAF has a more pronounced analgesic effect than LAH [56].

The laser-evoked γ-ERS can be regarded as a potential marker of pain sensitivity [57]. The magnitude of γ-ERS in the LAF group was lower than that of the LAH group, indicating that LAF has a better analgesic effect than LAH, which may be caused by the presence of trifluoroacetic ions in LAF. After injection of LAF in vivo, the anion of trifluoroacetic acid released by dissociation has the action of up-regulating the binding rate of glycine and its receptor [58]. In the spinal cord, glycine is involved in inhibiting the processing of sensory information including pain signals [59, 60]. Therefore, LAF inhibits the transfer of pain sensation by affecting glycine in the spinal cord, which is the main difference from the analgesic effect of LAH, and accounts for the significant analgesic activity.

Resting-State Spectra Reflect the Toxicity of LAF and LAH

The resting-state spectra with LAF and LAH showed the characteristic of increased power at low frequencies and decreased power at high frequencies (Fig. 7) that is similar to the central anesthetic state [61], while the results of AEP demonstrated that the rats were not under central anesthesia, because the AEP amplitude decreases in subjects under anesthesia [62]. Thus, changes in the resting state may indicate side-effects on individual consciousness and state [63], which may be due to drug neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity [64]. The effect of LAF on resting-state ECoG was less than that of LAH, especially between 60 and 100 Hz, indicating that the acute toxicity of LAF is lower than that of LAH. A possible reason is that the Br– of LAH has an inhibitory effect on the nervous system [65]. Besides, our previous work has verified that the LD50 of LAF is higher than that of LAH, and no abnormal changes in the organs (such as liver, kidney, and heart) occur in rats after a lethal dose [12]. The differences in the resting-state spectra of the two drugs indicated that the toxicity of the new derivative LAF was significantly lower than that of LAH, consistent with our previous results [12].

Conclusion

In this study, ECoG technology was used to quantify the analgesic effects of LAF and LAH in addition to their effects on behavioral scores. We evaluated the features of brain activity, LEPs and resting-state spectra. On this basis, the analgesic effects of the two homologous derivatives were compared in detail, and the analgesic mechanisms were further investigated. The results showed that both drugs had significant analgesic effects, which may be attributed to their parent ingredient, LA. The changes of the LEP, but not the AEP induced by LAF and LAH revealed the common mechanism of the two drugs, i.e., inhibition of the fast signaling pathway. Besides, the superior effects of LAF in the thermal hyperalgesia test, the resting state ECoG, and the γ-ERS were related to its degree of dissociation, octanol/water partition coefficient, toxicity, and glycine receptor regulation. This study confirms that ECoG is a reliable way to evaluate drug performance, which is conducive to converting experimental results into effective clinical analgesics, and provides a technical methodology for the development and application of natural analgesics.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51873175) and the Special Fund of Guiding Scientific and Technological Innovation and Development in Gansu Province, China (2019ZX-05).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Guixiang Teng and Fengrui Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lupeng Yue, Email: yuelp@psych.ac.cn.

Ji Zhang, Email: zhangj@nwnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: Evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391:2368–2383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh M, Morrison TG, McGuire BE. Chronic pain in adults with an intellectual disability: Prevalence, impact, and health service use based on caregiver report. PAIN. 2011;152:1951–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouhassira D, Attal N. Emerging therapies for neuropathic pain: New molecules or new indications for old treatments? PAIN. 2018;159:576–582. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Academy of Cognitive Disorders of China (ACDC) Han YL, Jia JJ, Li X, Lv Y, Sun X, et al. Expert consensus on the care and management of patients with cognitive impairment in China. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:307–320. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00444-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Negus SS. Core outcome measures in preclinical assessment of candidate analgesics. Pharmacol Rev. 2019;71:225–266. doi: 10.1124/pr.118.017210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, Nartey L, Wandel S, Jüni P, et al. RETRACTED: Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:2093–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaudioso C, Hao JZ, Martin-Eauclaire MF, Gabriac M, Delmas P. Menthol pain relief through cumulative inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels. PAIN. 2012;153:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu XC, Ge CT, Wang P, Zhang JL, Fu CY. Analgesic effects of lappaconitine in leukemia bone pain in a mouse model. PeerJ. 2015;3:e936. doi: 10.7717/peerj.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun WX, Zhang S, Wang H, Wang YP. Synthesis, characterization and antinociceptive properties of the lappaconitine salts. Med Chem Res. 2015;24:3474–3482. doi: 10.1007/s00044-015-1402-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang L, Liu CY, Gong GH, Quan ZS. Synthesis, in vitro and in vivo biological evaluation of novel lappaconitine derivatives as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:628–645. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun W, Saldaña MD, Fan L, Zhao Y, Dong T, Jin Y, et al. Sulfated polysaccharide heparin used as carrier to load hydrophobic lappaconitine. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;84:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teng GX, Zhang XF, Zhang C, Chen LL, Sun WX, Qiu T, et al. Lappaconitine trifluoroacetate contained polyvinyl alcohol nanofibrous membranes: Characterization, biological activities and transdermal application. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;108:110515. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YZ, Xiao YQ, Zhang C, Sun XM. Study of analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of lappaconitine gelata. J Tradit Chin Med. 2009;29:141–145. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(09)60051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada K, Ohkoshi E, Morris-Natschke SL, Bastow KF, Lee KH. Cytotoxic esterified diterpenoid alkaloid derivatives with increased selectivity against a drug-resistant cancer cell line. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labus JS, Keefe FJ, Jensen MP. Self-reports of pain intensity and direct observations of pain behavior: When are they correlated? PAIN. 2003;102:109–124. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirsch E, Lukas A, Drebenstedt C, Gnass I, Laekeman M, Kopke K, et al. Pain assessment for older persons in nursing home care: An evidence-based practice guideline. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancini F, Nash T, Iannetti GD, Haggard P. Pain relief by touch: A quantitative approach. PAIN. 2014;155:635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruccu G, Pennisi E, Truini A, Iannetti GD, Romaniello A, Le Pera D, et al. Unmyelinated trigeminal pathways as assessed by laser stimuli in humans. Brain. 2003;126:2246–2256. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross J, Schnitzler A, Timmermann L, Ploner M. Gamma oscillations in human primary somatosensory cortex reflect pain perception. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:1168–1173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu L, Valentini E, Zhang ZG, Liang M, Iannetti GD. The primary somatosensory cortex contributes to the latest part of the cortical response elicited by nociceptive somatosensory stimuli in humans. Neuroimage. 2014;84:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sikandar S, Ronga I, Iannetti GD, Dickenson AH. Neural coding of nociceptive stimuli-from rat spinal neurones to human perception. PAIN. 2013;154:1263–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang SY, Seymour B. Technology for chronic pain. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R930–R935. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun WX, Wang YP, Zhang J, Yu K. X-ray structure analysis of lappaconitine. Nat Prod Res. 2009;23:960–962. doi: 10.1080/14786410902975616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia XL, Peng WW, Iannetti GD, Hu L. Laser-evoked cortical responses in freely-moving rats reflect the activation of C-fibre afferent pathways. Neuroimage. 2016;128:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw FZ, Chen RF, Tsao HW, Yen CT. Comparison of touch- and laser heat-evoked cortical field potentials in conscious rats. Brain Res. 1999;824:183–196. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iannetti GD, Zambreanu L, Tracey I. Similar nociceptive afferents mediate psychophysical and electrophysiological responses to heat stimulation of glabrous and hairy skin in humans. J Physiol. 2006;577:235–248. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu L, Xia XL, Peng WW, Su WX, Luo F, Yuan H, et al. Was it a pain or a sound? Across-species variability in sensory sensitivity. PAIN. 2015;156:2449–2457. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valentini E, Koch K, Nicolardi V, Aglioti SM. Mortality salience modulates cortical responses to painful somatosensory stimulation: Evidence from slow wave and delta band activity. Neuroimage. 2015;120:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao ZM, Wang JY, Han JS, Luo F. Dynamic processing of nociception in cortical network in conscious rats: A laser-evoked field potential study. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:671–687. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw FZ, Chen RF, Yen CT. Dynamic changes of touch- and laser heat-evoked field potentials of primary somatosensory cortex in awake and pentobarbital-anesthetized rats. Brain Res. 2001;911:105–115. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson GV, Knight RT. Multiple brain systems generating the rat auditory evoked potential. I. Characterization of the auditory cortex response. Brain Res. 1993;602:240–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90689-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valentini E, Hu L, Chakrabarti B, Hu Y, Aglioti SM, Iannetti GD. The primary somatosensory cortex largely contributes to the early part of the cortical response elicited by nociceptive stimuli. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1571–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates: Hard. Cover. London: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang ZG, Hu L, Hung YS, Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Gamma-band oscillations in the primary somatosensory cortex——a direct and obligatory correlate of subjective pain intensity. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7429–7438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5877-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng WW, Xia XL, Yi M, Huang G, Zhang ZG, Iannetti G, et al. Brain oscillations reflecting pain-related behavior in freely moving rats. PAIN. 2018;159:106–118. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Across-trial averaging of event-related EEG responses and beyond. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu L, Xiao P, Zhang ZG, Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Single-trial time-frequency analysis of electrocortical signals: Baseline correction and beyond. Neuroimage. 2014;84:876–887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu L, Zhang ZG, Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Multiple linear regression to estimate time-frequency electrophysiological responses in single trials. Neuroimage. 2015;111:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lomas T, Ivtzan I, Fu CH. A systematic review of the neurophysiology of mindfulness on EEG oscillations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Babiloni C, Pistoia F, Sarà M, Vecchio F, Buffo P, Conson M, et al. Resting state eyes-closed cortical rhythms in patients with locked-in-syndrome: An EEG study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:1816–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zinn MA, Zinn ML, Valencia I, Jason LA, Montoya JG. Cortical hypoactivation during resting EEG suggests central nervous system pathology in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Biol Psychol. 2018;136:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telkes L, Hancu M, Paniccioli S, Grey R, Briotte M, McCarthy K, et al. Differences in EEG patterns between tonic and high frequency spinal cord stimulation in chronic pain patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131:1731–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Vries M, Wilder-Smith OH, Jongsma ML, van den Broeke EN, Arns M, van Goor H, et al. Altered resting state EEG in chronic pancreatitis patients: Toward a marker for chronic pain. J Pain Res. 2013;6:815–824. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S50919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayhew SD, Iannetti GD, Woolrich MW, Wise RG. Automated single-trial measurement of amplitude and latency of laser-evoked potentials (LEPs) using multiple linear regression. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1331–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science. 1997;277:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ameri A. The effects of Aconitum alkaloids on the central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:211–235. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li YF, Zheng YM, Yu Y, Gan Y, Gao ZB. Inhibitory effects of lappaconitine on the neuronal isoforms of voltage-gated sodium channels. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019;40:451–459. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0067-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright SN. Irreversible block of human heart (hH1) sodium channels by the plant alkaloid lappaconitine. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:183–192. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ren MY, Yu QT, Shi CY, Luo JB. Anticancer activities of C18-, C19-, C20-, and bis-diterpenoid alkaloids derived from genus Aconitum. Molecules. 2017;22:E267. doi: 10.3390/molecules22020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun ML, Ao JP, Wang YR, Huang Q, Li TF, Li XY, et al. Lappaconitine, a C18-diterpenoid alkaloid, exhibits antihypersensitivity in chronic pain through stimulation of spinal dynorphin A expression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018;235:2559–2571. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4948-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tommaso MD, Santostasi R, Devitofrancesco V, Franco G, Vecchio E, Delussi M, et al. A comparative study of cortical responses evoked by transcutaneous electrical vs CO2 laser stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:2482–2487. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ur Rashid M, Alamzeb M, Ali S, Ullah Z, Shah ZA, Naz I, et al. The chemistry and pharmacology of alkaloids and allied nitrogen compounds from Artemisia species: A review. Phytother Res. 2019;33:2661–2684. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Munegumi T. Where is the border line between strong acids and weak acids? World J Chem Educ. 2013;1:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tetko IV, Bruneau P. Application of ALOGPS to predict 1-octanol/water distribution coefficients, logP, and logD, of AstraZeneca in-house database. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:3103–3110. doi: 10.1002/jps.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zakeri-Milani P, Tajerzadeh H, Islambolchilar Z, Barzegar S, Valizadeh H. The relation between molecular properties of drugs and their transport across the intestinal membrane. Daru. 2006;14:164–171. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valentini E, Betti V, Hu L, Aglioti SM. Hypnotic modulation of pain perception and of brain activity triggered by nociceptive laser stimuli. Cortex. 2013;49:446–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tipps ME, Iyer SV, John Mihic S. Trifluoroacetate is an allosteric modulator with selective actions at the glycine receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang X, Shaffer PL, Ayube S, Bregman H, Chen H, Lehto SG, et al. Crystal structures of human glycine receptor α3 bound to a novel class of analgesic potentiators. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:108–113. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi YQ, Chen YY, Wang Y. Kir2.1 channel regulation of glycinergic transmission selectively contributes to dynamic mechanical allodynia in a mouse model of spared nerve injury. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:301–314. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0285-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ní Mhuircheartaigh R, Warnaby C, Rogers R, Jbabdi S, Tracey I. Slow-wave activity saturation and thalamocortical isolation during propofol anesthesia in humans. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:208ra148. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weber F, Zimmermann M, Bein T. The impact of acoustic stimulation on the AEP monitor/2 derived composite auditory evoked potential index under awake and anesthetized conditions. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:435–439. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000158470.34024.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang FR, Wang FX, Yue LP, Zhang HJ, Peng WW, Hu L. Cross-species investigation on resting state electroencephalogram. Brain Topogr. 2019;32:808–824. doi: 10.1007/s10548-019-00723-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li M, Cai ZW. Simultaneous determination of aconitine, mesaconitine, hypaconitine, bulleyaconitine and lappaconitine in human urine by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Methods. 2013;5:4034–4038. doi: 10.1039/c3ay40328a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goldstein DB. Sodium bromide and sodium valproate: Effective suppressants of ethanol withdrawal reactions in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1979;208:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.