Abstract

Purpose

Many studies identified that the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (PNLR) was associated with patient prognosis in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). We hypothesized that PNLR could be prognostic in patients with histological variants of NMIBC (VH-NMIBC).

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study included patients with VH-NMIBC admitted at our center between January 2009 and May 2019. The best cut-off value of NLR was measured by the receiver operating characteristic curve and Youden index. The Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazard regression models were employed to evaluate the association between PNLR and disease prognosis, including recurrence-free survival (RFS), progression-free survival (PFS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), and overall survival (OS).

Results

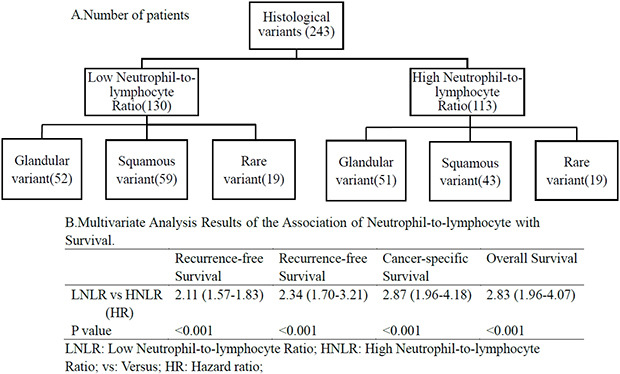

A total of 243 patients with VH-NMIBC were enrolled in our study. According to the Kaplan-Meier method results, patients with PNLR ≥2.2 were associated with poor RFS (p<0.001), PFS (p<0.001), CSS (p<0.001), and OS (p<0.001). Multivariable analyses indicated that PNLR ≥ 2.2 was an independent prognostic factor of RFS (hazard ratio [HR], 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI, 1.57–1.83; p<0.001), PFS (HR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.70–3.21; p<0.001), CCS (HR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.96–4.18; p< 0.001), and OS (HR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.96–4.07; p<0.001).

Conclusions

This study identified that PNLR ≥2.2 was usually associated with a poor prognosis for patients with VH-NMIBC.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Histology, Lymphocyte, Neutrophil, Prognosis

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer (BC) is the 10th most common form of cancer worldwide and the second most common urologic malignancy [1]. Of these, non-muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC) usually accounts for 70% to 75% of patients with BC at the time of the initial diagnosis [2,3]. Histologically, BC with variant histology accounted for approximately 15% to 25% of all patients who underwent transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) [3,4]. Of all histopathologic subtypes, squamous variant (SV) and glandular variant (GV) are the two most common histological variants. The remaining variants with significantly low incidence are collectively designated as rare histological variant (RV) [5]. Previous studies reported that most of the VH-NMIBC were more aggressive and associated with a poor response to treatment compared with pure transitional cell carcinoma (PTC) [6,7,8,9]. Consequently, urologists are striving to establish key predictors for risk stratification and therapeutic decision-making [10]. Despite identifying many prognostic factors, such as T stage, World Health Organization (WHO) grade, tumor number, BCG response, and so on, the effectiveness of some makers was under discussing in patients with VH-NMIBC [11,12].

Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (PNLR) has been discussed widely since Gondo et al. [13] reported the prognostic value of PNLR in BC. Subsequently, many studies focused on the correlation between PNLR and BC. Kaynar et al. [14] first identified that PNLR could predict the prognosis of patients with NMIBC. Although many studies reported this finding, different outcomes appeared were observed [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Meanwhile, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that PNLR can be an independent prognostic factor in patients with VH-NMIBC. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the prognostic value of PNLR in patients with VH-NMIBC by collecting information from our center.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patient selection and data collection

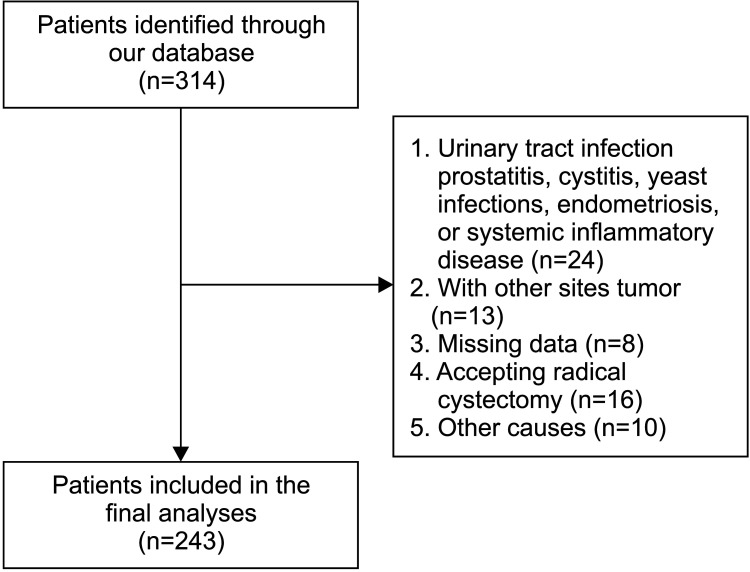

With Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the West China Hospital, Sichuan University approval (approval number: 20201045), patients with VH-NMIBC were included from January 2009 to May 2019 (Fig. 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. To avoid bias, we only included patients whose PNLR was determined 2 weeks before surgery. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with a diagnosis of prostatitis or cystitis, urinary tract infection, yeast infections, endometriosis, systemic inflammatory disease; those with missing data, other sites tumor; or those with a need for preforming radical cystectomy (RC) without muscle invasion. All patients in this study were classified for total group and subgroup analyses, including those with SV categorized as the SV group; with GV categorized as the GV group, and those with RV categorized as the RV group.

Fig. 1. Patient selection. The number of patients who were included and excluded in the present study is shown.

All specimens with VH were diagnosed by experienced pathologists according to the 2016 WHO BC classification [19]. VH-NMIBC was defined as any VH appearing in the specimen and a sample with mixed-variant would be classified as the VH with the highest proportion. Tumor stage, and carcinoma in situ were evaluated by the 2016 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). In the TNM staging system, the tumor was graded as per the 2016 WHO grading system [19,20]. Demographic, clinical and pathologic outcomes were determined in this study.

2. Management and follow-up

Intravesical therapies (IVTs), including bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) and chemotherapeutic drugs, were utilized in patients with T1 stage unless patients refused or their physical status did not permit. Chemotherapeutic drugs, including epirubicin and gemcitabine, were administered for 12 cycles after TURBT. Under the recommendation of the European Association of Urology guidelines, patients would receive a 6-week course of intravesical BCG induction followed by a standard maintenance regimen [11].

Follow-up was performed according to the European Association of Urology guidelines, including cystoscopy every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months 2 to 5 years after TURBT, and then annually [11]. A phone or face-to-face interview was used for patient follow-up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to local or distant recurrence. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as an increase in the stage to MIBC and/or metastasis. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to death from BC. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of TURBT to death due to any cause.

3. Statistical analysis

Chi-square and Student's t-tests were used for analyzing the associations between categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Fisher's exact test was applied to estimate categorical variables in the RV group due to the limited number of patients. The best cut-off value of PNLR was calculated by the receiver operating characteristic curve and Youden index. The cut-off value of body mass index was 23.4 kg/m2 [21]. The survival of patients with VH-NMIBC was validated using the Kaplan-Meier method and comparisons between groups were performed by log-rank tests. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were employed to evaluate the association of PNLR with RFS, PFS, CSS, and OS. We did not perform multivariable survival analysis in subgroups because of the limited number of patients. A p<0.05 was considered significant for all analyses, which were performed using SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

1. Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics

Based on the results of the receiver operating characteristic curve and Youden index, the best cut-off values of PNLR were 2.2 for all groups. The median follow-up time was 50.7 months (interquartile range [IQR], 30.0–68.0 mo), 50.4 months (IQR, 30.0–67.5 mo), 54.2 months (IQR, 35.3–68.8 mo), and 43.0 months (IQR, 23.3–56.8 mo) in the total, GV, SV, and RV groups, respectively. The median follow-up time of high NLR (HNLR) and low NLR (LNLR) were 46.5 months (IQR, 28.0–58.8 mo) and 49.0 months (IQR, 31.0–78.3 mo), respectively. According to the cut-off value, patients were divided into LNLR and HNLR groups. Among 38 patients in the RV group, 13 patients were diagnosed with the sarcomatoid variant, 12 with the micropapillary variant, 5 with the plasmacytoid variant, 4 with the nested variant and 4 with the neuroendocrine variant. The detailed baseline clinicopathologic data of the patients are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. The clinical characteristics of patients with histological variants of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

| Variable | Total group | p-value | GV group | p-value | SV group | p-value | RV group | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNLR (n=130) | HNLR (n=113) | LNLR (n=52) | HNLR (n=51) | LNLR (n=59) | HNLR (n=43) | LNLR (n=19) | HNLR (n=19) | ||||||

| Sex (female) | 25 | 18 | 0.508 | 9 | 8 | 0.825 | 10 | 7 | >0.999 | 6 | 3 | 0.447 | |

| Age (y) | 65.0 (59–71) | 68.5 (62–77) | 0.852 | 66.5 (50–71) | 69.6 (62–76) | 0.699 | 63.0 (58–72) | 70.0 (62–75) | 0.609 | 65.0 (62–70) | 64.0 (59–77) | 0.529 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5 (20.3–24.3) | 21.6 (1.5–24.2) | 0.686 | 22.7 (20.8–24.2) | 21.9 (19.2–21.9) | 0.102 | 22.3 (19.8–24.2) | 21.9 (19.7–23.4) | 0.176 | 23.2 (20.6–27.5) | 23.2 (20.0–25.0) | 0.867 | |

| Smoking history | 0.649 | 0.267 | 0.321 | 0.517 | |||||||||

| Yes | 59 | 48 | 25 | 19 | 23 | 21 | 11 | 8 | |||||

| No | 71 | 65 | 27 | 32 | 36 | 22 | 8 | 11 | |||||

| Hypertension | 0.361 | 0.862 | 0.069 | >0.999 | |||||||||

| Yes | 28 | 30 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 6 | 5 | |||||

| No | 102 | 83 | 39 | 39 | 50 | 30 | 13 | 14 | |||||

| Diabetes | 0.666 | 0.343 | 0.003 | 0.660 | |||||||||

| Yes | 21 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 16 | 4 | 2 | |||||

| No | 109 | 97 | 40 | 43 | 54 | 37 | 15 | 17 | |||||

| Gross hematuria | 0.905 | >0.999 | 0.884 | - | |||||||||

| Yes | 119 | 103 | 47 | 46 | 53 | 39 | 19 | 19 | |||||

| No | 11 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| T stage | 0.528 | 0.616 | 0.929 | >0.999 | |||||||||

| a | 18 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 1 | 118 | 101 | 43 | 44 | 52 | 39 | 17 | 18 | |||||

| Multifocality | 0.784 | 0.921 | 0.350 | 0.495 | |||||||||

| Single | 59 | 64 | 26 | 26 | 22 | 20 | 8 | 5 | |||||

| Multiple | 71 | 72 | 26 | 25 | 37 | 23 | 11 | 14 | |||||

| Tumor size (cm)a | 0.493 | 0.195 | 0.696 | 0.737 | |||||||||

| <3 | 53 | 51 | 27 | 20 | 20 | 13 | 6 | 8 | |||||

| >3 | 77 | 62 | 25 | 31 | 39 | 30 | 13 | 11 | |||||

| WHO grade | 0.313 | 0.846 | 0.681 | 0.180 | |||||||||

| Low | 26 | 17 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 1 | |||||

| High | 104 | 96 | 41 | 41 | 49 | 37 | 14 | 18 | |||||

| CIS | 0.353 | 0.680 | 0.530 | 0.604 | |||||||||

| Yes | 33 | 23 | 13 | 11 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| No | 97 | 90 | 39 | 40 | 42 | 33 | 16 | 18 | |||||

| Treatment | 0.604 | 0.122 | 0.116 | 0.029 | |||||||||

| IVT | 82 | 67 | 39 | 31 | 34 | 18 | 10 | 17 | |||||

| Only TURBT | 48 | 45 | 13 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 9 | 2 | |||||

| Recurrence | 111 | 109 | 0.003 | 47 | 49 | 0.449 | 46 | 41 | 0.014 | 17 | 19 | 0.243 | |

| Progression | 84 | 101 | <0.001 | 34 | 48 | <0.001 | 37 | 36 | 0.020 | 13 | 17 | 0.232 | |

| Cancer-related death | 50 | 82 | <0.001 | 16 | 34 | <0.001 | 25 | 33 | 0.011 | 9 | 15 | 0.091 | |

| Overall death | 53 | 86 | <0.001 | 18 | 35 | 0.001 | 26 | 36 | 0.002 | 9 | 15 | 0.091 | |

Values are presented as number only or median (interquartile range).

LNLR, low neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; HNLR, high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; GV, glandular variant; SV, squamous variant; RV, rare histological variants; BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; CIS, carcinoma in situ; IVT, intravesical therapy; TURBT, transurethral resection of bladder tumor.

a:For multiple tumors, the diameter of the largest tumor was regarded as tumor size.

2. The relationship of PNLR and recurrence

Overall, 111/130 (85.4%) patients with LNLR compared with 109/113 (96.5%) patients with HNLR had cancer recurrence during the study. Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that the HNLR group was associated with a higher recurrence rate (p<0.001) (Fig. 2A) compared to the LNLR group. Multivariable survival analyses revealed that PNLR (hazard ratio [HR], 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.57–1.83; p<0.001) was an independent predictor of RFS (Table 2).

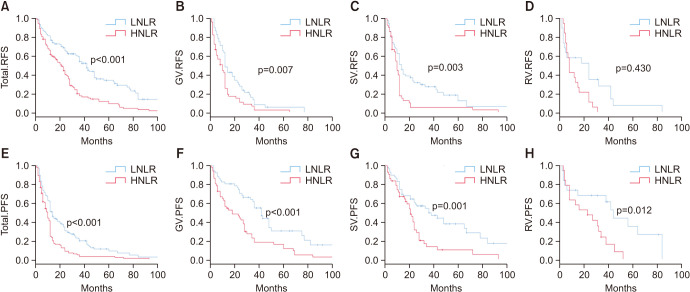

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier plots depicting RFS and PFS according to the preoperative NLR. (A) RFS, total group. (B) RFS, GV group. (C) RFS, SV group. (D) RFS, RV group. (E) PFS, total group. (F) PFS, GV group. (G) PFS, SV group. (H) PFS, RV group. RFS, recurrence-free survival; PFS, progression-free survival; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; LNLR, low NLR; HNLR, high NLR; GV, glandular variant; SV, squamous variant; RV, rare histological variant.

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of the association of different factors with recurrence-free and progression-free survival.

| Variable | Recurrence-free survival | Progression-free survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

| Age (>60 years old) | 0.90 (0.67–1.21) | 0.500 | 1.05 (0.75–1.47) | 0.783 |

| Sex (reference female) | 1.26 (0.85–1.86) | 0.255 | 1.08 (0.68–1.69) | 0.752 |

| Smoker | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) | 0.950 | 1.05 (0.76–1.45) | 0.768 |

| BMI (≥24.3 kg/m2) | 0.83 (0.62–1.11) | 0.215 | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 0.617 |

| Diabetes | 1.31 (0.88–1.95) | 0.178 | 1.47 (0.92–2.12) | 0.062 |

| Hypertension | 1.02 (0.72–1.45) | 0.908 | 0.76 (0.51–1.14) | 0.181 |

| Multifocality | 1.01 (0.76–1.34) | 0.963 | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 0.882 |

| Tumor size (≥3 cm)a | 1.26 (0.94–1.68) | 0.121 | 1.37 (1.01–1.88) | 0.047 |

| T1 vs. Ta | 9.10 (2.68–30.93) | <0.001 | 3.44 (1.31–9.03) | 0.012 |

| WHO high grade | 1.43 (0.96–2.12) | 0.076 | 1.63 (1.08–2.46) | 0.200 |

| CIS (no vs. yes) | 1.79 (1.28–2.49) | 0.001 | 1.28 (0.90–1.83) | 0.171 |

| IVT (yes vs. no) | 1.25 (0.93–1.66) | 0.135 | 0.94 (0.69–1.28) | 0.689 |

| PNLR >2.2 | 2.11 (1.57–1.83) | <0.001 | 2.34 (1.70–3.21) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; CIS, carcinoma in situ; IVT, intravesical therapy; PNLR, preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

a:For multiple tumors, the diameter of the largest tumor was regarded as tumor size.

Further, 49/51 (96.1%) of the HNLR patients and 47/52 (90.4%) of the LNLR patients experienced cancer recurrence in the GV group, and the former was correlated with a higher recurrence rate than the latter (p=0.007) (Fig. 2B). In the SV group, 41/43 (95.3%) of the HNLR patients and 37/41 (90.2%) of the LNLR patients experienced cancer recurrence and the former was correlated with a lower RFS than the latter (p=0.003) (Fig. 2C). In the RV group, 19/19 (100%) of the HNLR patients and 17/19 (89.5%) of the LNLR patients experienced cancer recurrence. Similarly, patients with HNLR were correlated with higher recurrence than the LNLR (p=0.430) (Fig. 2D).

3. The relationship of PNLR and progression

Overall, disease progression was identified in 101/113 (89.4%) of the HNLR patients and 84/130 (64.6%) of the LNLR patients. Patients with HNLR had an obviously higher rate of progression (p<0.001) (Fig. 2E) compared to patients with LNLR. HNLR was associated with an inferior PFS compared with LNLR (HR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.70–3.21; p<0.001) (Table 2).

In the subgroup analyses, progression occurred in 48/51 (94.1%) of the HNLR patients and 34/52 (65.4%) of the LNLR patients in the GV group, confirming that the former was associated with an inferior PFS (p<0.001) (Fig. 2F) than the latter. For the SV group, progression occurred in 36/43 (83.7%) of the HNLR patients and 37/59 (62.7%) of the LNLR patients, identifying the former had an inferior PFS than the latter (p=0.001) (Fig. 2G). In the RV group, progression occurred in 17/19 (89.5%) of the HNLR patients and 13/19 (68.4%) of the LNLR patients, where the former was associated with an inferior PFS than the latter (p=0.012) (Fig. 2H).

4. The relationship of PNLR and survival

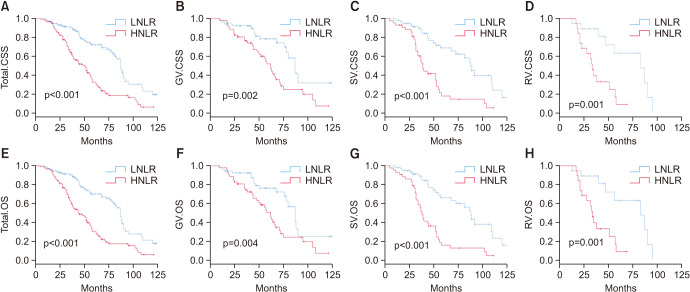

During the follow-up period, 86/113 (76.1%) patients with HNLR compared with 53/130 (40.8%) patients with LNLR had died. Additionally, patients with HNLR had a shorter survival than patients with LNLR, both in CSS (p<0.001) and OS (p<0.001) (Fig. 3A, Fig. 3E; respectively). Based the outcome of multivariable survival analyses, HNLR was an independent risk predictor of CSS (HR, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.96–4.18]; p<0.001, Table 3) and OS (HR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.96–4.07; p<0.001, Table 3).

Fig. 3. Kaplan-Meier plots depicting CSS and OS according to the preoperative NLR. (A) CSS, total group. (B) CSS, GV group. (C) CSS, SV group. (D) CSS, RV group. (E) OS, total group. (F) OS, GV group. (G) OS, SV group. (H) OS, RV group. CSS, cancer-specific survival; OS, overall survival; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; LNLR, low NLR; HNLR, high NLR; GV, glandular variant; SV, squamous variant; RV, rare histological variant.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of the association of different factors and survival.

| Variable | Cancer-specific survival | Overall survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

| Age (>60 years old) | 1.01 (0.69–1.49) | 0.955 | 1.02 (0.70–1.49) | 0.923 |

| Sex (reference female) | 1.17 (0.69–2.00) | 0.565 | 1.26 (0.75–2.12) | 0.379 |

| Smoker | 1.16 (0.77–1.75) | 0.471 | 1.24 (0.84–1.85) | 0.282 |

| BMI (≥24.3 kg/m2) | 1.17 (0.80–1.70) | 0.432 | 1.14 (0.79–1.65) | 0.491 |

| Diabetes | 1.47 (0.86–2.51) | 0.164 | 1.40 (0.83–1.85) | 0.282 |

| Hypertension | 0.56 (0.35–0.89) | 0.015 | 0.60 (0.38–0.94) | 0.027 |

| Multifocality | 1.12 (0.77–1.62) | 0.561 | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | 0.713 |

| Tumor size (≥3 cm)a | 1.07 (0.73–1.56) | 0.722 | 1.13 (0.78–1.63) | 0.521 |

| T1 vs. Ta | 3.19 (1.09–9.28) | 0.034 | 3.43 (1.18–9.95) | 0.023 |

| WHO high grade | 1.20 (0.75–1.92) | 0.440 | 1.26 (0.79–2.00) | 0.336 |

| CIS (no vs. yes) | 0.87 (0.57–1.35) | 0.539 | 0.87 (0.57–1.33) | 0.519 |

| IVT (no vs. yes) | 1.02 (0.70–1.49) | 0.918 | 1.06 (0.73–1.54) | 0.753 |

| PNLR >2.2 | 2.87 (1.96–4.18) | <0.001 | 2.83 (1.96–4.07) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; CIS, carcinoma in situ; IVT, Intravesical therapy; PNLR, preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

a:For multiple tumors, the diameter of the largest tumor was regarded as tumor size.

In the GV group, 35/51 (68.6%) of the HNLR patients and 18/52 (34.6%) of the LNLR patients had died. Benefits in CCS (p=0.002) and OS (p=0.004) were observed in patients with LNLR (Fig. 3B, Fig. 3F; respectively). In the SV group, 36/43 (83.7%) of the HNLR patients and 26/59 (44.1%) of LNLR patients had died, while patients with HNLR had a lower survival rate than those with LNLR, both in CSS (p<0.001) and OS (p<0.001) (Fig. 3C, Fig. 3G; respectively). In the RV group, 15/19 (78.9%) of the HNLR patients and 9/19 (47.4%) of the LNLR patients had died. Patients with LNLR had a higher survival rate than those with HNLR, both in CSS (p=0.001) and OS (p=0.001) (Fig. 3D, Fig. 3H; respectively). Further prognostic information was shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Several studies indicated that PNLR was associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence, progression and survival in patients with NMIBC [17,18,22]. However, none of these studies focused on the effectiveness of PNLR in VH-NMIBC. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prognostic value of PNLR in VH-NMIBC. Finally, the present study for the first time identified that patients with HNLR have a worse prognosis, including RFS, PFS, CSS and OS, than of patients with LNLR.

Many studies indicated that the appearance of VH in NMIBC usually meant advent disease and poor prognosis, prompting surgeons to perform early RC [22]. Urologists sought to determine what patient subset has aggressive properties and discover the useful biomarkers for identifying a higher risk population, especially in patients with VH-NMIBC. Hence, prognostic factors, such as gene, RNA, protein, and clinicopathological parameters, were validated. Of these, inflammatory markers were widely discussed and reported. Through cell–cell contact and/or secretion of inhibitory factors, immune cells could create a pro-tumor inflammatory state, leading an active role of systemic inflammation in tumor growth, recurrence, and progression [23]. As significant immune cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes have inhibitory and activating function, respectively, where in the former is usually associated with a poor prognosis [24]. After being identified in other tumors, the prognostic function of PNLR was increasingly appreciated by urologists. The cut-off value of PNLR in NMIBC usually ranged from 2 to 3; however, Yuk et al. [21] reported a value of 1.5. In addition, Buisan et al. [25] believed 5 was the optimal cut-off value in SV-MIBC before performing RC because they believed that the SV was linked to chronic inflammation. Similar to most studies, the optimal cut-off value in the present study was 2.2, but this difference might be explained by sample size and disease stage.

According to the results of multivariable analyses, most studies demonstrated that HNLR was associated with worse prognosis [14,15,18,26]. Recently, a meta-analysis indicated that HNLR was associated with an increased risk of disease recurrence. Similarly, the prognostic effect of PNLR in RFS was proved in this study. Some discrepancy existed in the risk of progression and many studies identified that HNLR could predict an inferior PFS, but this has been challenged by some studies. Of note, all of the studies, opposing PNLR as a predictor excluded patients with VH-NMIBC in their patient selection criteria [16,17,21,27]. Conversely, studies that confirmed the statistical significance of PNLR included VH-NMIBC patients in the final analysis [14,15,16,26,28]. This difference maybe the cause of the discrepancy and supports the prognostic value of PNLR in VH-NMIBC. In this study on VH-NMIBC, data on progression validated the independent prognostic value of PNLR. Due to the long survival time, only a few studies have analyzed survival status. A multi-institutional study reported that HNLR only predicted inferior CSS, but a significant difference regarding OS was not noted [18]. The remaining two studies found an association between PNLR and the survival of NMIBC both in CSS and OS [21,29]. The present study also identified that HNLR was associated with worse CSS and OS. Therefore, the PNLR level could assist with therapeutic decision-making and identify appropriate candidates for more aggressive therapy, such as early RC for high-risk VH-NMIBC.

This study has some limitations, including those inherent to the retrospective design of the study. The bias of data might be noticed because the study data was derived from a hospital information system. Additionally, due to sample size limitations for different subgroups, multivariable survival analyses could not be performed. However, of the prognostic value of the PNLR in VH-NMIBC was identified.

CONCLUSIONS

PNLR level was correlated with the prognosis of patients with VH-NMIBC, which could assist with therapeutic decision-making and identify appropriate candidates for more aggressive therapy. Prospective clinical trials are warranted to provide a higher level of evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the Pillar Program from Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (2018SZ0219) and the 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZY2016104).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

- Research conception and design: Deng-xiong Li, Yin Tang, and Fa-cai Zhang.

- Data acquisition: Deng-xiong Li, Xiao-ming Wang, Yun-jin Bai, and Yu-bo Yang.

- Statistical analysis: Deng-xiong Li.

- Data analysis and interpretation: Deng-xiong Li.

- Drafting of the manuscript: Deng-xiong Li and Yin Tang.

- Critical revision of the manuscript: Yun-jin Bai, Yu-bo Yang, Fa-cai Zhang, and Ping Han.

- Obtaining funding: Ping Han.

- Administrative, technical, or material support: Ao Li and De-chao Feng.

- Supervision: Ping Han.

- Approval of the final manuscript: Ping Han.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.20210278.

Kaplan-Meier plots depicting (A) RFS, (B) PFS, (C) CSS, and (D) OS according to the different histological subtypes (RV group, GV group, and SV group).

The p-value of PNLR according to the classification of clinicopathological characteristics

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen ME, Smith AB, Meyer AM, Kuo TM, Tyree S, Kim WY, et al. Trends in stage-specific incidence rates for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder in the United States: 1988 to 2006. Cancer. 2014;120:86–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K, Mshs MD. Bladder cancer: a review. JAMA. 2020;324:1980–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonati C, Baumeister P, Ornaghi PI, Di Trapani E, De Cobelli O, Rink M, et al. EAU-YAU Urothelial Cancer Working Party. Accuracy of transurethral resection of the bladder in detecting variant histology of bladder cancer compared with radical cystectomy. Eur Urol Focus. 2021 Apr 15; doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2021.04.005. [Epub] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Li A, Yang Y, Feng D, Zhang F, Wang X, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of rare histological variants of bladder cancer: a single-center retrospective study from China. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:9635–9641. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S269065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yorozuya W, Nishiyama N, Shindo T, Kyoda Y, Itoh N, Sugita S, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin may have clinical benefit for glandular or squamous differentiation in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients: retrospective multicenter study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:661–666. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li G, Yu J, Song H, Zhu S, Sun L, Shang Z, et al. Squamous differentiation in patients with superficial bladder urothelial carcinoma is associated with high risk of recurrence and poor survival. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:530. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3520-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Hu J, Niu Y. Squamous differentiation in pT1 bladder urothelial carcinoma predicts poor response for intravesical chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 2017;9:217–223. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gofrit ON, Yutkin V, Shapiro A, Pizov G, Zorn KC, Hidas G, et al. The response of variant histology bladder cancer to intravesical immunotherapy compared to conventional cancer. Front Oncol. 2016;6:43. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferro M, Di Mauro M, Cimino S, Morgia G, Lucarelli G, Abu Farhan AR, et al. Systemic combining inflammatory score (SCIS): a new score for prediction of oncologic outcomes in patients with high-risk non-muscle-invasive urothelial bladder cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2021;10:626–635. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2021. Arnhem: European Association of Urology; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferro M, Di Lorenzo G, Buonerba C, Lucarelli G, Russo GI, Cantiello F, et al. Predictors of residual T1 high grade on retransurethral resection in a large multi-institutional cohort of patients with primary T1 high-grade/Grade 3 bladder cancer. J Cancer. 2018;9:4250–4254. doi: 10.7150/jca.26129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gondo T, Nakashima J, Ohno Y, Choichiro O, Horiguchi Y, Namiki K, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and establishment of novel preoperative risk stratification model in bladder cancer patients treated with radical cystectomy. Urology. 2012;79:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaynar M, Goktas S. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts progression and recurrence of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:497. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Andrea D, Moschini M, Gust K, Abufaraj M, Ozsoy M, Özsoy R, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e755–e764. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Favilla V, Castelli T, Urzì D, Reale G, Privitera S, Salici A, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, a biomarker in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a single-institutional longitudinal study. Int Braz J Urol. 2016;42:685–693. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozyalvacli ME, Ozyalvacli G, Kocaaslan R, Cecen K, Uyeturk U, Kemahlı E, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of recurrence and progression in patients with high-grade pT1 bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:E126–E131. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vartolomei MD, Ferro M, Cantiello F, Lucarelli G, Di Stasi S, Hurle R, et al. Validation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in a multi-institutional cohort of patients with T1G3 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part B: prostate and bladder tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th ed. Cham: Springer; 2016. pp. 1402–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuk HD, Jeong CW, Kwak C, Kim HH, Ku JH. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients: initial intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin treatment after transurethral resection of bladder tumor setting. Front Oncol. 2019;8:642. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yonekura S, Terauchi F, Hoshi K, Yamaguchi T, Kawai S. Optimal body mass index cut-point for predicting recurrence-free survival in patients with non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of bladder. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:4049–4056. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider AK, Chevalier MF, Derré L. The multifaceted immune regulation of bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2019;16:613–630. doi: 10.1038/s41585-019-0226-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fridman WH, Zitvogel L, Sautès-Fridman C, Kroemer G. The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:717–734. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buisan O, Orsola A, Oliveira M, Martinez R, Etxaniz O, Areal J, et al. Role of inflammation in the perioperative management of urothelial bladder cancer with squamous-cell features: impact of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on outcomes and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e697–e706. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao SY, Huang TB, Xiong DD, Liu MN, Cai KK, Yao XD. Prognostic value of preoperative systemic inflammatory responses in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:5799–5810. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang M, Jeong CW, Kwak C, Kim HH, Ku JH. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio can significantly predict mortality outcomes in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12891–12901. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogihara K, Kikuchi E, Yuge K, Yanai Y, Matsumoto K, Miyajima A, et al. The preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a novel biomarker for predicting worse clinical outcomes in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer patients with a previous history of smoking. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(Suppl 5):1039–1047. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma C, Lu B, Diao C, Zhao K, Wang X, Ma B, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and fibrinogen level in patients distinguish between muscle-invasive bladder cancer and non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4917–4922. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S107445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Kaplan-Meier plots depicting (A) RFS, (B) PFS, (C) CSS, and (D) OS according to the different histological subtypes (RV group, GV group, and SV group).

The p-value of PNLR according to the classification of clinicopathological characteristics