Abstract

This quality improvement study evaluates the sustainability of Clean Cut, a surgical infection prevention program implemented at hospitals in Ethiopia.

Surgical infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries.1 Recently, a number of infection prevention and control programs have been implemented in low-income countries with subsequent reduction in surgical site infections.2,3 Clean Cut is one such adaptive, multimodal quality improvement intervention developed in Ethiopia. High compliance with perioperative infection prevention practices was associated with a 35% relative risk reduction in surgical site infections in the postintervention period compared with baseline.4 The persistence of practice changes after quality improvement interventions is rarely assessed,5 and whether many surgical infection prevention and control quality improvement programs in low- and middle-income countries provide short-term solutions only or result in long-term cultural and behavioral shifts is unclear.6 We aimed to measure the sustainability of improvements made in infection prevention practices after introduction of the Clean Cut program.

Methods

This quality improvement study was conducted at 8 hospitals in Ethiopia that completed the Clean Cut program between September 1, 2015, and November 15, 2019. Through surveillance of infection prevention practices, process mapping, training, and action planning, surgical teams improved behaviors in 6 key areas of infection prevention: (1) surgical safety checklist use, (2) skin antisepsis, (3) antibiotic prophylaxis, (4) surgical linen sterility and integrity, (5) instrument sterility, and (6) gauze counting. We conducted a 14-day assessment of perioperative practices through direct observation 6 to 18 months after completion of the program. Seven hospitals were included in the sustainability assessment; the eighth facility had transitioned leadership and did not participate. Data collectors observed all operations in the same operating theaters involved in the initial program during a 14-day period using the same Clean Cut data collection tool. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethiopian National Institutional Review Board through the Africa Health Research Institute. Informed consent was waived because this study was part of a quality improvement program. Data analysis was performed using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC). Compliance was defined as correctly performing 100% of expected behaviors in each of the 6 key areas. A 2-side P = .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study cohort included 3385 patients (2384 [70.4%] female; median age, 27 years [IQR, 20-36 years]), including 738 before implementation of the program, 2178 after implementation, and 469 during the sustainability audit (Table). The case urgency was similar between groups; the sustainability group had slightly fewer comorbidities and included more obstetric and surgical specialty procedures.

Table. Patient Characteristics and Perioperative Infection Prevention Practices in the Phases of Clean Cut Program Implementationa.

| Factor | Baseline (n = 738) | After implementation (n = 2178) | Sustainability audit (n = 469) | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 26 (1-35) | 28 (22-37) | 26 (16-32) | <.001c |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 493 (66.8) | 1539 (70.7) | 352 (75.1) | .056d |

| Male | 254 (33.2) | 639 (29.3) | 117 (24.9) | |

| Diabetes | 14 (1.9) | 46 (2.1) | 2 (0.4) | <.001d |

| Hypertension | 25 (3.4) | 54 (2.5) | 12 (2.6) | <.001d |

| Case urgency | ||||

| Elective | 270 (36.6) | 881 (40.4) | 171 (36.5) | .25d |

| Emergency | 344 (46.6) | 1169 (53.7) | 257 (54.8) | |

| Unknown | 124 (16.8) | 128 (5.9) | 41 (8.7) | |

| Hospital | ||||

| 1 | 76 (10.3) | 414 (19.0) | 30 (6.4) | <.001d |

| 2 | 36 (4.9) | 117 (5.4) | 15 (3.2) | |

| 3 | 36 (4.9) | 379 (17.4) | 37 (7.9) | |

| 4 | 268 (36.3) | 192 (8.8) | 176 (37.5) | |

| 5 | 69 (9.3) | 512 (23.5) | 14 (3.0) | |

| 6 | 56 (7.6) | 230 (10.6) | 83 (17.7) | |

| 7 | 197 (26.7) | 334 (15.3) | 114 (24.3) | |

| Procedure type | ||||

| Obstetric | 285 (38.6) | 934 (42.9) | 256 (54.6) | <.001d |

| General surgery | 335 (45.4) | 1090 (50.0) | 121 (25.8) | |

| Other | 118 (16.0) | 154 (7.1) | 92 (19.6) | |

| Infection prevention process measures | ||||

| Surgical safety checklist | 194 (26.3) | 1089 (50.0) | 274 (58.4) | .02d |

| Hand and skin antisepsis | 339 (45.9) | 1254 (57.6) | 351 (74.8) | <.001d |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | 388 (52.6) | 1279 (58.7) | 308 (65.7) | <.001d |

| Surgical linen sterility and integrity | 46 (6.2) | 1002 (46.0) | 183 (39.0) | <.001d |

| Instrument sterility | 57 (7.7) | 1192 (54.7) | 196 (41.8) | <.001d |

| Gauze counting | 630 (85.4) | 2046 (93.9) | 444 (94.7) | .04d |

Data are presented as number (percentage) of the patients unless otherwise indicated.

P value indicates after implementation vs sustainability audit.

Indicates Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Indicates Pearson χ2 test.

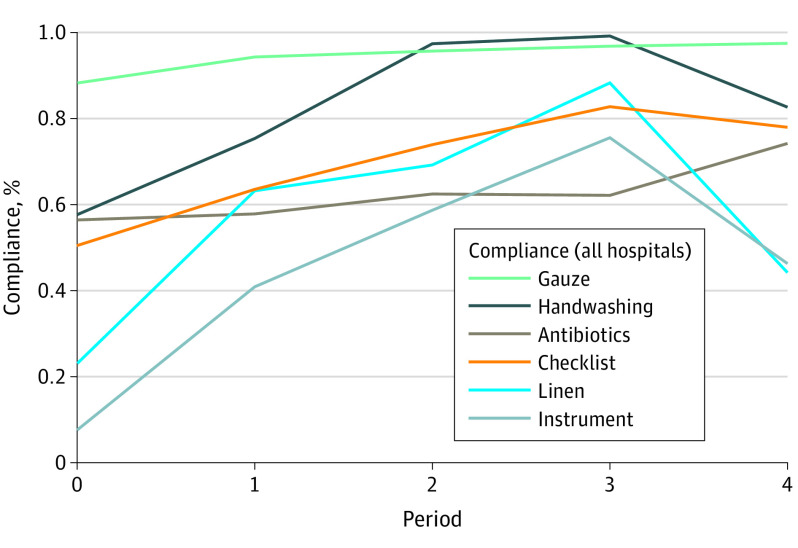

Compared with the postimplementation period, the sustainability audit period showed further improvement in compliance with the surgical safety checklist use (1089 [50.0%] vs 274 [58.4%]), skin antisepsis (1254 [57.6%] vs 351 [74.8%%]), antibiotic prophylaxis (1279 [58.7%] vs 308 [65.7%]), and gauze counting (2046 [93.9%] vs 444 [94.7%]). Some attrition in compliance occurred with surgical linen integrity and sterility (1002 [46.0%] vs 183 [39.0%]) and instrument sterility (1192 [54.7%] vs 196 [41.8%]), but performance in these 2 areas remained above baseline (46 [6.2%] and 57 [7.7%], respectively). Multivariate logistic regression confirmed that these findings were not associated with differences in case volume by hospital, age, or procedure type. When performance was measured during more granular periods, all areas had peak performance in the final third of program implementation and a decrease in performance by the sustainability evaluation except antibiotic administration and gauze counting, which continued to improve (Figure).

Figure. Compliance With Perioperative Infection Prevention Standards Through Phases of Clean Cut Implementation and at the Sustainability Audit Time Point.

Period 0 indicates before implementation; 1, beginning of the program; 2, middle of the program; 3, end of the program; and 4, sustainability audit.

Discussion

In this quality improvement study, behavior changes associated with a multimodal surgical quality improvement program were persistent and, in some cases, continued to improve. This study has limitations. Other initiatives focused on surgical quality improvement in Ethiopia may have supported persistent improvement in practices at the 7 hospitals. Furthermore, ensuring linen and instrument sterility requires not only correct behaviors but also the availability of sterility indicators and functioning autoclaves, which rely on biomedical engineering expertise and purchasing decisions at the management level. These elements are not always under the control of surgical teams but are cohesive to the operating room environment.

Despite demonstrable improvement in practices and infectious complications associated with surgical quality improvement programs, the long-term success of most interventions has not been measured, to our knowledge. This study suggests that strategic interventions to improve surgical quality and infection prevention behaviors are worthwhile investments that may provide improved patient safety over time.

References

- 1.GlobalSurg Collaborative . Surgical site infection after gastrointestinal surgery in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: a prospective, international, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(5):516-525. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30101-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allegranzi B, Aiken AM, Zeynep Kubilay N, et al. A multimodal infection control and patient safety intervention to reduce surgical site infections in Africa: a multicentre, before-after, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(5):507-515. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30107-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins KJ, Castañeda AR, Cherian KM, et al. Reducing mortality and infections after congenital heart surgery in the developing world. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1422-e1430. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrester JA, Starr N, Negussie T, Schaps D, Adem M, Alemu S, et al. Clean Cut (adaptive, multimodal surgical infection prevention programme) for low-resource settings: a prospective quality improvement study. Br J Surg. Published online September 21, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariyo P, Zayed B, Riese V, et al. Implementation strategies to reduce surgical site infections: A systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(3):287-300. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim RY, Kwakye G, Kwok AC, et al. Sustainability and long-term effectiveness of the WHO surgical safety checklist combined with pulse oximetry in a resource-limited setting: two-year update from Moldova. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(5):473-479. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]