Key Points

Question

Are melanomas diagnosed through routine skin checks (a proxy for skin cancer screening) associated with reduced melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality?

Findings

This population-based cohort study included 2452 patients, each with 1 diagnosed melanoma, 35% of which were detected during a routine skin check. In multivariable analyses, routine skin-check detection was associated with a subhazard ratio of 0.68 for melanoma-specific mortality and 0.75 for all-cause mortality compared with patient-detected melanomas after a mean follow-up of 11.9 years.

Meaning

Melanomas diagnosed through routine skin checks were associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality, but not melanoma-specific mortality, after adjustment for patient, sociodemographic, and clinicopathologic factors.

This cohort study investigates the association between melanomas diagnosed during routine skin checks and melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality.

Abstract

Importance

Early melanoma diagnosis is associated with better health outcomes, but there is insufficient evidence that screening, such as having routine skin checks, reduces mortality.

Objective

To assess melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality associated with melanomas detected through routine skin checks, incidentally or patient detected. A secondary aim was to examine patient, sociodemographic, and clinicopathologic factors associated with different modes of melanoma detection.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective, population-based, cohort study included patients in New South Wales, Australia, who were diagnosed with melanoma over 1 year from October 23, 2006, to October 22, 2007, in the Melanoma Patterns of Care Study and followed up until 2018 (mean [SD] length of follow-up, 11.9 [0.3] years) by using linked mortality and cancer registry data. All patients who had invasive melanomas recorded at the cancer registry were eligible for the study, but the number of in situ melanomas was capped. The treating doctors recorded details of melanoma detection and patient and clinical characteristics in a baseline questionnaire. Histopathologic variables were obtained from pathology reports. Of 3932 recorded melanomas, data were available and analyzed for 2452 (62%; 1 per patient) with primary in situ (n = 291) or invasive (n = 2161) cutaneous melanoma. Data were analyzed from March 2020 to January 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Melanoma-specific mortality and all-cause mortality.

Results

A total of 2452 patients were included in the analyses. The median age at diagnosis was 65 years (range, 16-98 years), and 1502 patients (61%) were men. A total of 858 patients (35%) had their melanoma detected during a routine skin check, 1148 (47%) self-detected their melanoma, 293 (12%) had their melanoma discovered incidentally when checking another skin lesion, and 153 (6%) reported “other” presentation. Routine skin-check detection of invasive melanomas was associated with 59% lower melanoma-specific mortality (subhazard ratio, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.28-0.60; P < .001) and 36% lower all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.76; P < .001), adjusted for age and sex, compared with patient-detected melanomas. After adjusting for prognostic factors including ulceration and mitotic rate, the associations were 0.68 (95% CI, 0.44-1.03; P = .13), and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.63-0.90; P = .006), respectively. Factors associated with higher odds of routine skin-check melanoma detection included being male (female vs male, odds ratio [OR], 0.73; 95% CI, 0.60-0.89; P = .003), having previous melanoma (vs none, OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.77-3.15; P < .001), having many moles (vs not, OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.10-1.77; P = .02), being 50 years or older (eg, 50-59 years vs <40 years, OR, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.92-4.34; P < .001), and living in nonremote areas (eg, remote or very remote vs major cities, OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.05-1.04; P = .003).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, melanomas diagnosed through routine skin checks were associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality, but not melanoma-specific mortality, after adjustment for patient, sociodemographic, and clinicopathologic factors.

Introduction

The costs, morbidity, and mortality associated with melanoma diagnosis place a high burden on health care systems in many countries.1,2,3 Diagnosis of melanoma at an earlier stage is associated with better survival,4 and observational studies have shown that whole-body clinical skin examination is associated with lower melanoma mortality and fewer thick (ie, higher stage) melanomas,5,6,7,8 although the observed mortality decline in the Schleswig-Holstein region of Germany was not replicated after the introduction of population-wide screening in Germany.9 Apart from Germany, no country has an organized population-based melanoma screening program because of insufficient evidence that screening reduces melanoma mortality; uncertainty about possible harms, such as overdiagnosis and unnecessary biopsy10,11,12; and limited evidence for cost-effectiveness.1,13,14

Over the last decade, there has been renewed interest in melanoma screening,10,15,16,17 driven by the changing landscape of melanoma care. Changes include the increasing health system costs for new therapies,18,19 better diagnostic technologies,20 more accurate risk-stratification algorithms,21 and better understanding of high-risk melanoma features.10,16 There may also be benefits from the inevitably associated early detection of the much more numerous nonpigmented skin cancers (keratinocyte carcinomas) and enhanced prevention education.16,17

In addition to cancer-specific mortality, the effect of cancer screening on all-cause mortality is also of interest, as reducing deaths from a particular cancer type should translate to an improvement in all-cause mortality unless investigation of positive screening results leads to deaths from other causes.22

Using population-based data, we aimed to assess melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality associated with melanoma identified through routine skin checks (as a proxy for skin cancer screening), incidentally, or through patient detection. A secondary aim was to examine patient, sociodemographic, and clinicopathologic factors associated with different modes of melanoma detection.

Methods

Study Sample

The Melanoma Patterns of Care Study cohort comprised patients diagnosed with a histopathologically confirmed primary in situ or invasive cutaneous melanoma in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, compulsorily reported to the NSW Cancer Registry between October 23, 2006, and October 22, 2007.23 Based on available resources, the study prioritized the collection of invasive melanomas (for the full year of data collection) over in situ melanomas (limited to the first 450 diagnoses, collected over 2-3 months), as invasive melanomas were most relevant to clinical practice guidelines and patient outcomes. The treating physician at diagnosis was asked to complete a questionnaire about the patient’s risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Race and ethnicity were not routinely measured in clinical practice and so were not collected as part of this study. If the patient was referred to another physician, that physician was also sent a questionnaire; otherwise, it was assumed that all of the patient’s care had been provided by the notifying physician. Rates of discrepancy between questionnaires were low and were handled by keeping any value where a characteristic was reported as present (vs absent) or by keeping data from the most appropriate source (eg, pathology data from pathology report, diagnosis-related data from the diagnosing physician). Questionnaires were completed for 2758 of 3869 patients (71%). Trained field workers assisted with the completion of 1298 of 4057 questionnaires (32%).

Ethics approval was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee and the Australian Capital Territory Health Human Research Ethics Committee, and governance approvals were received for each linked data set. A waiver of patient consent was approved by the ethics committee, in line with national ethical regulations, as data were collected directly from clinicians and administrative sources. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was used to guide this report.24

Data Collection

The questionnaire asked “How did this melanoma present? (tick one only)” with 5 responses: “patient reported this skin lesion,” “found incidentally when checking another skin lesion,” “found in a routine skin check,” “other (specify),” and “don’t know.” The questionnaire asked if the patient had a personal or family history of melanoma and if they had “lots of moles.” Postcode of residence was used to estimate patients’ socioeconomic status25 and their Accessibility/Remoteness Index.26 Histopathologic data were extracted from pathology reports held by the NSW Cancer Registry. If melanoma subtype was coded as “not otherwise specified” in the Registry, the pathology report was checked for these details. We also cross-checked missing histopathologic details with a linked database from Melanoma Institute Australia, which is the largest melanoma referral and treatment center in NSW.

Patients were followed up for diagnosis of new primary melanomas and death from any cause for a mean (SD) of 11.9 (0.3) years. Dates and cause of death from October 23, 2006, to December 31, 2018, were identified through linkage of patients’ identities with the Cause of Death Unit Record File and Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages in NSW and the Australian Capital Territory. Data sources for the Australian Capital Territory were used because this geographically small, population-dense area is completely enclosed within NSW. Physicians or coroners completed the death certificates, recording multiple causes of death where applicable. The Australian Bureau of Statistics then checked and coded the information using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. The incidence of other in situ and invasive melanomas that occurred in the Melanoma Patterns of Care Study cohort both before and after the 2006 to 2007 study period were identified from the NSW and Australian Capital Territory Cancer Registries from 1972 to 2018. Pathological and clinical data were also obtained from the Melanoma Institute Australia research database from October 23, 2006, to December 31, 2018.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis data set included 2452 melanomas (1 per patient), of which 291 (12%) were in situ and 2161 (88%) were invasive (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). To calculate differences in proportions, χ2 tests were used, and multinomial logistic regression models were used to estimate multivariable odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. To evaluate potential interactions between patient factors (age, sex, number of moles, family history, and previous melanoma) and different modes of melanoma detection, we tested the inclusion of interaction terms in the multivariable models and stratified analyses.

Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality were estimated from Cox regression models. Subhazard ratios for melanoma-specific mortality were estimated from Fine and Gray competing risk regression models with death from other causes as the competing risk.27 Minimally adjusted models were adjusted for age (continuous) and sex. Multivariable-adjusted model 1 was further adjusted for previous melanoma, family history, moles, socioeconomic status,25 residential remoteness,26 anatomic site, and melanoma subtype; and multivariable-adjusted model 2 was adjusted for these variables plus ulceration and mitotic rate. Explanatory variables were selected a priori based on known or expected confounders. An assessment of confounding is shown in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. We also conducted mortality analyses stratified by Breslow thickness categories.

Unknown responses for variables were kept as separate categories in the multivariable models to maintain a constant sample size. Regression models excluded melanomas detected by “other” presentation because of its heterogeneous representation. Analyses for mortality outcomes were conducted with and without the inclusion of patients with in situ melanoma only and also after excluding patients who developed another (thicker or thinner) invasive melanoma (15%) or another thicker invasive melanoma (8%) either before or after the study period (identified using linked data). All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Figures were made using R, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation). All P values were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed from March 2020 to January 2021.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of 3932 recorded melanomas, data were available and analyzed for 2452 (62%; 1 per patient). Of the 2452 patients included in the analysis, 858 (35%) had their melanoma detected at a routine skin check, 1148 (47%) self-detected their melanoma, 293 (12%) had their melanoma discovered incidentally when checking another skin lesion, and 153 (6%) reported “other” presentation (Table 1). The median patient age at diagnosis was 65 years (range, 16-98 years); 1502 patients were men (61%), and 950 were women (39%).

Table 1. Detection of Melanomas by Demographic, Clinical, and Melanoma Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How the melanoma was detected | Total (N = 2452) | |||||

| Patient detected (n = 1148 [47%]) | Found incidentally (n = 293 [12%]) | Routine skin check (n = 858 [35%]) | Other (n = 153 [6%]) | |||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 636 (42) | 199 (13) | 579 (39) | 88 (6) | 1502 (100) | <.001 |

| Female | 512 (54) | 94 (10) | 279 (29) | 65 (7) | 950 (100) | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| <40 | 163 (76) | 6 (3) | 41 (19) | 4 (2) | 214 (100) | <.001 |

| 40-49 | 177 (66) | 17 (6) | 60 (22) | 15 (6) | 269 (100) | |

| 50-59 | 213 (46) | 50 (11) | 166 (36) | 33 (7) | 462 (100) | |

| 60-69 | 236 (43) | 81 (15) | 206 (38) | 26 (5) | 549 (100) | |

| 70-79 | 217 (39) | 73 (13) | 230 (41) | 40 (7) | 560 (100) | |

| ≥80 | 142 (36) | 66 (17) | 155 (39) | 35 (9) | 398 (100) | |

| Socioeconomic statusb | ||||||

| 1st Quintile (lowest) | 123 (48) | 34 (13) | 82 (32) | 18 (7) | 257 (100) | .37 |

| 2nd Quintile | 233 (51) | 54 (12) | 147 (32) | 25 (5) | 459 (100) | |

| 3rd Quintile | 296 (47) | 84 (13) | 218 (34) | 35 (6) | 633 (100) | |

| 4th Quintile | 199 (47) | 50 (12) | 145 (34) | 31 (7) | 425 (100) | |

| 5th Quintile (highest) | 297 (44) | 71 (10) | 266 (39) | 44 (6) | 678 (100) | |

| Residential remotenessc | ||||||

| Major cities | 490 (47) | 120 (11) | 367 (35) | 68 (7) | 1045 (100) | .003 |

| Inner regional | 439 (44) | 125 (12) | 386 (38) | 58 (6) | 1008 (100) | |

| Outer regional | 205 (54) | 46 (12) | 103 (27) | 27 (7) | 381 (100) | |

| Remote or very remote | 14 (78) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) | 0 | 18 (100) | |

| Previous melanoma | ||||||

| No | 1006 (50) | 227 (11) | 650 (32) | 123 (6) | 2006 (100) | <.001 |

| Yes | 93 (27) | 57 (17) | 183 (53) | 11 (3) | 344 (100) | |

| Family history of melanoma | ||||||

| No | 794 (48) | 191 (12) | 572 (35) | 95 (6) | 1652 (100) | .25 |

| Yes | 99 (50) | 15 (8) | 75 (38) | 8 (4) | 197 (100) | |

| Many moles | ||||||

| No | 750 (47) | 196 (12) | 537 (34) | 111 (7) | 1594 (100) | <.001 |

| Yes | 223 (42) | 62 (12) | 225 (42) | 21 (4) | 531 (100) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Change in color, size, elevation or shape of lesion | ||||||

| No | 224 (20) | 192 (17) | 619 (55) | 96 (8) | 1131 (100) | <.001 |

| Yes | 924 (70) | 101 (8) | 239 (18) | 57 (4) | 1321 (100) | |

| Itch | ||||||

| No | 1086 (46) | 287 (12) | 849 (36) | 150 (6) | 2372 (100) | <.001 |

| Yes | 62 (78) | 6 (8) | 9 (11) | 3 (4) | 80 (100) | |

| Bleeding or ulceration | ||||||

| No | 1036 (45) | 282 (12) | 840 (37) | 142 (6) | 2300 (100) | <.001 |

| Yes | 112 (74) | 11 (7) | 18 (12) | 11 (7) | 152 (100) | |

| Observed lesion for a period before biopsy | ||||||

| No | 1059 (47) | 278 (12) | 792 (35) | 145 (6) | 2274 (100) | .10 |

| Yes | 51 (42) | 12 (10) | 55 (45) | 4 (3) | 122 (100) | |

| Clinical melanoma | ||||||

| No | 228 (53) | 48 (11) | 129 (30) | 23 (5) | 428 (100) | <.001 |

| Suspicious | 317 (53) | 68 (11) | 163 (27) | 51 (9) | 599 (100) | |

| Yes | 572 (42) | 176 (13) | 555 (40) | 74 (5) | 1377 (100) | |

| Practice setting | ||||||

| General practice | 514 (55) | 107 (11) | 243 (26) | 75 (8) | 939 (100) | <.001 |

| Skin cancer clinic | 146 (33) | 35 (8) | 252 (57) | 6 (1) | 439 (100) | |

| Dermatology | 188 (30) | 113 (18) | 283 (46) | 36 (6) | 620 (100) | |

| Surgery | 300 (66) | 38 (8) | 80 (18) | 36 (8) | 454 (100) | |

| Melanoma characteristics | ||||||

| Breslow thickness, mm | ||||||

| In situ | 103 (35) | 31 (11) | 132 (45) | 25 (9) | 291 (100) | <.001 |

| 0.01-0.79 | 452 (39) | 158 (14) | 492 (42) | 62 (5) | 1164 (100) | |

| 0.80-1.0 | 125 (49) | 31 (12) | 85 (33) | 15 (6) | 256 (100) | |

| 1.01-2.00 | 210 (56) | 44 (12) | 95 (26) | 23 (6) | 372 (100) | |

| 2.01-4.00 | 164 (70) | 21 (9) | 34 (15) | 15 (6) | 234 (100) | |

| >4.00 | 89 (71) | 8 (6) | 17 (13) | 12 (10) | 126 (100) | |

| Mean (median) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | |

| Melanoma subtype (invasive) | ||||||

| Superficial spreading | 529 (47) | 128 (11) | 408 (36) | 57 (5) | 1122 (100) | <.001 |

| Nodular | 208 (70) | 24 (8) | 43 (14) | 23 (8) | 298 (100) | |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 67 (31) | 38 (18) | 92 (43) | 17 (8) | 214 (100) | |

| Otherd | 64 (51) | 16 (13) | 34 (27) | 11 (9) | 125 (100) | |

| Not otherwise specified | 177 (44) | 56 (14) | 149 (37) | 20 (5) | 402 (100) | |

| Melanoma subtype (in situ) | ||||||

| Superficial spreading | 28 (40) | 5 (7) | 29 (41) | 8 (11) | 70 (100) | .05 |

| Lentigo maligna | 41 (32) | 14 (11) | 65 (50) | 10 (8) | 130 (100) | |

| Not otherwise specified, or otherd | 34 (37) | 12 (13) | 38 (42) | 7 (8) | 91 (100) | |

| Anatomic site | ||||||

| Head or neck | 254 (51) | 66 (13) | 141 (28) | 37 (7) | 498 (100) | <.001 |

| Anterior trunk (front) | 91 (51) | 20 (11) | 55 (31) | 11 (6) | 177 (100) | |

| Posterior trunk (back) | 264 (34) | 100 (13) | 356 (46) | 58 (7) | 778 (100) | |

| Upper limb | 276 (51) | 66 (12) | 171 (32) | 28 (5) | 541 (100) | |

| Lower limb | 255 (58) | 40 (9) | 128 (29) | 18 (4) | 441 (100) | |

| Ulceration | ||||||

| No | 817 (46) | 218 (12) | 636 (36) | 106 (6) | 1777 (100) | <.001 |

| Yes | 173 (65) | 29 (11) | 48 (18) | 15 (6) | 265 (100) | |

| Mitotic rate per mm | ||||||

| <1 | 292 (39) | 101 (13) | 317 (42) | 46 (6) | 756 (100) | <.001 |

| 1-2 | 249 (51) | 64 (13) | 156 (32) | 20 (4) | 489 (100) | |

| 3-10 | 234 (62) | 40 (11) | 76 (20) | 25 (7) | 375 (100) | |

| >10 | 64 (70) | 6 (7) | 11 (12) | 11 (12) | 92 (100) | |

Nonreported or missing values are excluded from percentage and P value calculations.

Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage, based on postcode of residence.

Residential remoteness is based on 2006 Census data matched to patients’ postcode of residence.

Other category includes rarer subtypes.

Among the male patients, 579 of 1502 melanomas (39%) were detected on a routine skin check, compared with 279 of 950 (29%) for female patients (Table 1). Female patients’ melanomas were more likely to be patient detected (512 of 950 [54%] vs 94 [10%] found incidentally, 279 [29%] found on routine skin check, or 65 [7%] found by other means). Younger people were more likely to detect their melanomas than older people (eg, for age <40 years, 163 of 214 patients [76%] self-detected melanoma, whereas for age >80 years, 142 of 398 patients [36%] self-detected melanoma). Patients with many moles (yes, 225 of 531 [42%] vs no, 537 of 1594 [34%]) or a previous melanoma (yes, 183 of 344 [53%] vs no, 650 of 2006 [32%]) were more likely to have their melanoma detected at a routine skin check than those without these risk factors, but family history was not associated with mode of detection. People living in outer regional and remote areas were less likely to have their melanoma detected during a routine skin check (outer regional, 103 of 381 [27%]; remote, 2 of 18 [11%]) and more likely to be patient detected (outer regional, 205 of 381 [54%]; remote, 14 of 18 [78%]) compared with people living in major cities (routine skin check, 367 of 1045 [35%]; patient detected, 490 of 1045 [47%]) and inner regional areas (routine skin check, 386 of 1008 [38%]; patient detected, 439 of 1008 [44%]), but mode of detection did not differ by area-based socioeconomic status.

The same associations were apparent in the multivariable multinomial logistic regression model (Table 2). Compared with patient detection, there was a higher odds of melanoma being detected during a routine skin check for men (women vs men, OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.60-0.89; P = .003), those aged 50 years or older (eg, 50-59 years vs <40 years, OR, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.92-4.34; P < .001), those with a previous melanoma (vs none, OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.77-3.15; P < .001), those with many moles (vs without, OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.10-1.77; P = .02), or living in nonremote areas (eg, remote or very remote vs major cities, OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.05-1.04; P = .003). Family history of melanoma and socioeconomic status were not significantly associated with melanoma detection. Similar results were found for incidental detection, although the CIs were wider owing to fewer patients in this subgroup. The results were similar in a sensitivity analysis that excluded predictors with “don’t know” or missing values. There were no significant interactions between patient factors and melanoma detection.

Table 2. Multivariable Analysis of Patient Characteristics Associated With Melanoma Detection on a Routine Skin Check or Found Incidentally, Compared With Patient-Detected Presentationa.

| Patient characteristic | Patient detected (referent group), No. | Found incidentally | Routine skin check | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Odds ratio (95% CI)c | No. | Odds ratio (95% CI)c | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 636 | 199 | 1 [Reference] | 579 | 1 [Reference] | .003 |

| Female | 512 | 94 | 0.74 (0.55-0.98) | 279 | 0.73 (0.60-0.89) | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| <40 | 163 | 6 | 1 [Reference] | 41 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| 40-49 | 177 | 17 | 2.50 (0.96-6.53) | 60 | 1.29 (0.81-2.04) | |

| 50-59 | 213 | 50 | 5.74 (2.39-13.80) | 166 | 2.89 (1.92-4.34) | |

| 60-69 | 236 | 81 | 8.20 (3.47-19.38) | 206 | 3.26 (2.18-4.88) | |

| 70-79 | 217 | 73 | 7.56 (3.18-18.00) | 230 | 3.78 (2.52-5.67) | |

| ≥80 | 142 | 66 | 10.33 (4.30-24.8) | 155 | 3.94 (2.57-6.05) | |

| Previous melanoma | ||||||

| No | 1006 | 227 | 1 [Reference] | 650 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 93 | 57 | 2.06 (1.41-3.03) | 183 | 2.36 (1.77-3.15) | |

| Unknown | 49 | 9 | 0.68 (0.31-1.47) | 25 | 0.78 (0.46-1.34) | |

| Family history of melanoma | ||||||

| No | 794 | 191 | 1 [Reference] | 572 | 1 [Reference] | .35 |

| Yes | 99 | 15 | 0.77 (0.42-1.38) | 75 | 1.13 (0.80-1.59) | |

| Unknown | 255 | 87 | 1.26 (0.91-1.73) | 211 | 1.02 (0.80-1.29) | |

| Many moles | ||||||

| No | 750 | 196 | 1 [Reference] | 537 | 1 [Reference] | .02 |

| Yes | 223 | 62 | 1.17 (0.82-1.65) | 225 | 1.39 (1.10-1.77) | |

| Unknown | 175 | 35 | 0.80 (0.53-1.22) | 96 | 0.81 (0.61-1.09) | |

| Socioeconomic statusd | ||||||

| 1st Quintile (lowest) | 123 | 34 | 1 [Reference] | 82 | 1 [Reference] | .36 |

| 2nd Quintile | 233 | 54 | 0.80 (0.48-1.32) | 147 | 0.90 (0.62-1.30) | |

| 3rd Quintile | 296 | 84 | 0.93 (0.58-1.49) | 218 | 1.00 (0.70-1.41) | |

| 4th Quintile | 199 | 50 | 0.90 (0.54-1.50) | 145 | 1.02 (0.70-1.49) | |

| 5th Quintile (highest) | 297 | 71 | 0.88 (0.53-1.44) | 266 | 1.32 (0.93-1.89) | |

| Residential remoteness | ||||||

| Major cities | 490 | 120 | 1 [Reference] | 367 | 1 [Reference] | .003 |

| Inner regional | 439 | 125 | 1.17 (0.86-1.61) | 386 | 1.34 (1.07-1.67) | |

| Outer regional | 205 | 46 | 0.88 (0.57-1.37) | 103 | 0.79 (0.57-1.09) | |

| Remote or very remote | 14 | 2 | 0.57 (0.12-2.66) | 2 | 0.23 (0.05-1.04) | |

This analysis was based on 2299 patients, as it excluded 153 patients with “other” recorded for how the melanoma presented.

P value from Wald χ2 test for overall association between predictor variable and 3-level outcome, ie, compares the odds ratios across the 3 modes of detection.

From multinomial logistic regression model, adjusted for all other variables in the table.

Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage, based on postcode of residence.

Clinical Characteristics

A total of 1321 of the 2452 melanomas (54%) were reported to have a change in color, size, elevation or shape, and these were more likely to be patient detected (n = 924 [70%]), whereas melanomas without these changes were more likely to be detected during a routine skin check (619 of 1131 [55%]) (Table 1). Other symptoms included itch (n = 80 [3%]) and bleeding or ulceration (n = 152 [6%]); melanomas with these symptoms were also more likely to be patient detected (itch, 62 of 80 [78%]; bleeding or ulceration, 112 of 152 [74%]). Four hundred twenty-eight melanomas (17%) did not appear clinically suspicious, and this was more common for patient-detected melanomas (228 of 428 [53%]). Only 122 lesions (5%) were observed clinically for a period before biopsy, and this was more likely to occur for melanomas detected during a routine skin check (55 of 122 [45%]).

Melanomas detected in general practice (community-based primary care) were more likely to be patient detected (514 of 939 [55%]), but those detected in dedicated skin cancer clinics (run by general practitioners) and specialist dermatology clinics were more likely to be detected on a routine skin check (252 of 439 [57%] and 283 of 620 [46%], respectively). Of the 858 melanomas detected on a routine skin check, 243 (28%) were in general practice settings, 252 (29%) in skin cancer clinics, 283 (33%) in dermatology clinics, and 80 (9%) in surgical settings.

Melanoma Characteristics

In situ and thin invasive melanomas were more frequently detected at routine skin checks (in situ, 132 of 291 [45%]; thin invasive 0.01-0.79 mm, 492 of 1164 [42%]), than thicker melanomas (>4.00 mm, 17 of 126 [13%]) (Table 1). Routine skin checks detected a higher proportion of all lentigo maligna melanomas (92 of 214 [43%]) than nodular melanomas (43 of 298 [14%]). A total of 208 of 298 nodular melanomas (70%) were patient detected. Melanomas detected during a routine skin check were more frequently located on the back (356 of 858 [41%]) and more likely to have good prognostic features (nonulcerated, 636 of 858 [74%]; low mitotic rate <1 per mm2, 317 of 858 [37%]).

Associations Between Mode of Melanoma Detection and Melanoma-Specific and All-Cause Mortality

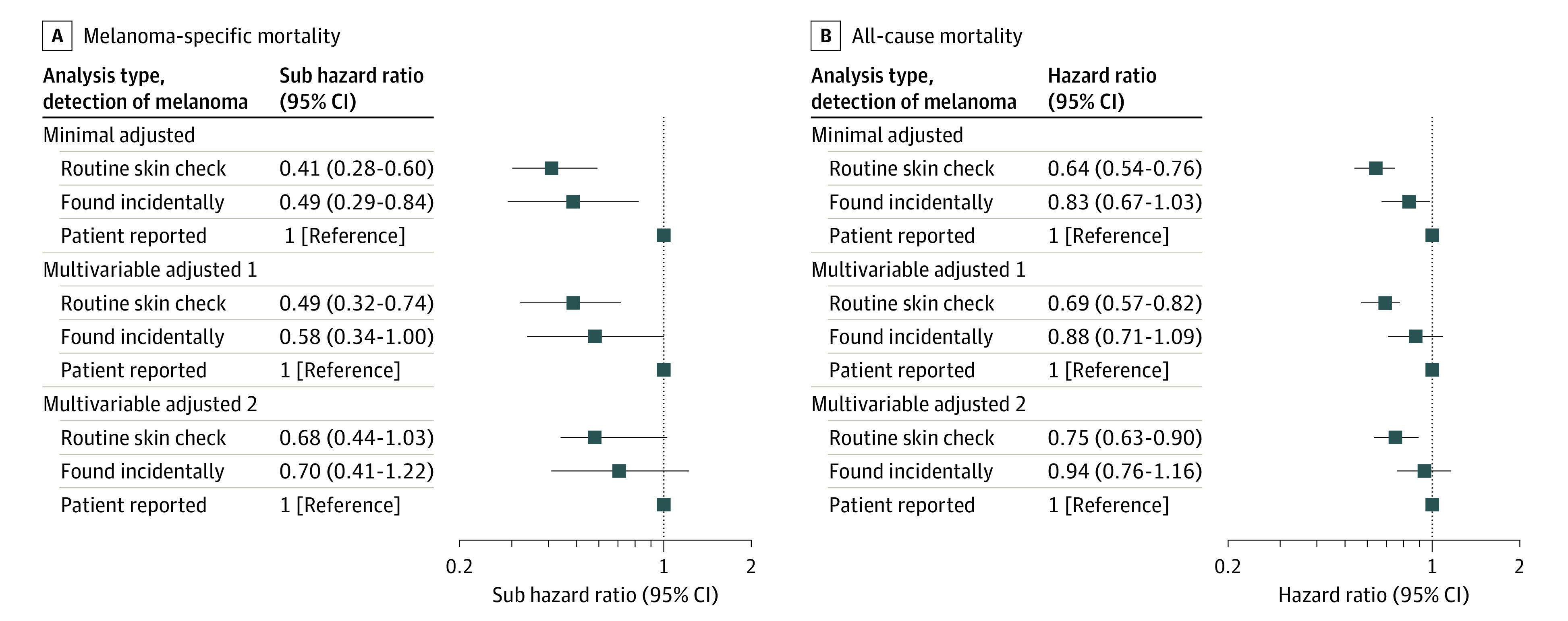

Over a mean (SD) follow-up of 11.9 (0.3) years, there were 162 deaths (7%) from melanoma and 604 deaths (26%) from other causes from the 2299 patients who were included in the survival analysis. Detection of invasive melanoma at a routine skin check was associated with 59% lower melanoma-specific mortality (subhazard ratio, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.28-0.60) and 36% lower all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.76) compared with patient-detected melanomas in regression models adjusted for age and sex (Table 3 and Figure). The results were similar when the analyses were stratified by patient characteristics. Incidentally found melanomas were associated with lower melanoma-specific mortality (subhazard ratio, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.29-0.84) and lower all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.67-1.03) in the minimally adjusted models (Table 3).

Table 3. Hazard Ratios for All-Cause Mortality and Subhazard Ratios for Melanoma Mortality Associated With Different Modes of Melanoma Detection.

| Melanoma detectiona | Alive | Died from melanoma | Died from other causes | Melanoma-specific mortality, subhazard ratio (95% CI)b | All-cause mortality, hazard ratio (95% CI)c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimally adjustedd | Multivariable adjusted 1e | Multivariable adjusted 2f | Minimally adjustedd | Multivariable adjusted 1e | Multivariable adjusted 2f | ||||

| Invasive melanoma only (excludes patients with in situ primary melanoma only)g | |||||||||

| Patient detected | 707 | 103 | 235 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Found incidentally | 152 | 16 | 94 | 0.49 (0.29-0.84) | 0.58 (0.34-1.00) | 0.70 (0.41-1.22) | 0.83 (0.67-1.03) | 0.88 (0.71-1.09) | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) |

| Routine skin check | 496 | 36 | 194 | 0.41 (0.28-0.60) | 0.49 (0.32-0.74) | 0.68 (0.44-1.03) | 0.64 (0.54-0.76) | 0.69 (0.57-0.82) | 0.75 (0.63-0.90) |

| P value | NA | NA | NA | <.001 | .001 | .13 | <.001 | <.001 | .006 |

| All patients (with either invasive or in situ primary melanoma)h | |||||||||

| Patient detected | 778 | 103 | 267 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Found incidentally | 171 | 17 | 105 | 0.53 (0.31-0.89) | 0.62 (0.36-1.05) | 0.74 (0.44-1.27) | 0.83 (0.68-1.01) | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | 0.94 (0.77-1.15) |

| Routine skin check | 584 | 42 | 232 | 0.45 (0.32-0.65) | 0.55 (0.37-0.82) | 0.76 (0.51-1.14) | 0.65 (0.55-0.75) | 0.70 (0.59-0.82) | 0.76 (0.64-0.90) |

| P value | NA | NA | NA | .01 | .007 | .30 | <.001 | <.001 | .02 |

| Single or thickest invasive melanoma (excludes patients with in situ melanoma only or with another thicker invasive melanoma diagnosed before or after 2006-2007 study)i | |||||||||

| Patient detected | 682 | 97 | 220 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Found incidentally | 134 | 12 | 85 | 0.42 (0.23-0.78) | 0.53 (0.28-0.99) | 0.67 (0.36-1.24) | 0.83 (0.67-1.04) | 0.88 (0.70-1.10) | 0.94 (0.75-1.18) |

| Routine skin check | 439 | 25 | 175 | 0.33 (0.21-0.52) | 0.43 (0.26-0.69) | 0.62 (0.38-1.02) | 0.64 (0.54-0.76) | 0.68 (0.56-0.82) | 0.75 (0.62-0.91) |

| P value | NA | NA | NA | <.001 | .001 | .11 | <.001 | <.001 | .01 |

| Single invasive melanoma only (excludes patients with in situ melanoma only or with another invasive melanoma of any thickness diagnosed before or after 2006-2007 study)j | |||||||||

| Patient detected | 652 | 92 | 205 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Found incidentally | 123 | 11 | 72 | 0.43 (0.23-0.82) | 0.56 (0.29-1.07) | 0.75 (0.39-1.44) | 0.81 (0.64-1.03) | 0.85 (0.67-1.08) | 0.94 (0.74-1.20) |

| Routine skin check | 393 | 22 | 160 | 0.32 (0.20-0.51) | 0.41 (0.25-0.67) | 0.62 (0.37-1.03) | 0.66 (0.55-0.79) | 0.67 (0.56-0.82) | 0.76 (0.62-0.92) |

| P value | NA | NA | NA | <.001 | .001 | .16 | <.001 | <.001 | .02 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Excludes patients with “other” recorded for how the melanoma was detected.

Subhazard ratios for melanoma-specific mortality are estimated from competing risk regression models with death from other causes as the competing risk.

Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality are estimated from Cox regression models.

Adjusted for age (continuous) and sex.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, previous melanoma, family history, moles, socioeconomic status, residential remoteness, anatomic site, and melanoma subtype.

Additionally adjusted for ulceration and mitotic rate.

Analysis based on 2033 patients.

Analysis based on 2299 patients.

Analysis based on 1869 patients.

Analysis based on 1730 patients.

Figure. Subhazard and Hazard Ratios for Mortality Associated With Different Modes of Detection of Invasive Melanoma.

Subhazard ratios for melanoma-specific mortality (A) and hazard ratios for all-cause mortality (B). Minimally adjusted analyses were adjusted for age (continuous) and sex. Multivariable-adjusted model 1 was further adjusted for previous melanoma, family history, moles, socioeconomic status, residential remoteness, anatomic site, and melanoma subtype; and multivariable-adjusted model 2 was adjusted for these variables plus ulceration and mitotic rate.

The melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality associations with routine skin check were slightly attenuated but remained statistically significant after adjusting for patient, sociodemographic, and some clinicopathologic prognostic factors (multivariable-adjusted model 1). After further adjustment for mitotic rate and ulceration, the association was no longer statistically significant for melanoma-specific mortality (subhazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.44-1.03) but remained statistically significant for all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.90) (multivariable-adjusted model 2). Adjustment for mitotic rate led to the largest change to the hazard ratios, followed by melanoma subtype and ulceration.

The subhazard ratios for melanoma-specific mortality were higher when the analyses also included patients with in situ melanoma and were lower after excluding patients who developed another invasive melanoma either before or after the study period (Table 3). When the multivariable-adjusted mortality analyses were stratified by Breslow thickness categories, the subhazard ratios for melanoma-specific mortality and routine skin-check detection appeared greater for lower Breslow thickness (subhazard ratio, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.15-0.91 for thickness 0.01-0.79 mm; 0.88; 95% CI, 0.41-1.93 for 0.8-2.0 mm; 1.56; 95% CI, 0.61-3.96 for 2.01-4.0 mm; and 0.97; 95% CI, 0.27-3.46 for thickness >4.0 mm), but the association was not significant.

Discussion

In this population-based prospective cohort study with a mean 11.9 years follow-up, we found that melanomas discovered in asymptomatic individuals through routine skin checks were thinner, less likely to have been noted to exhibit recent change, and associated with lower all-cause mortality than thicker lesions discovered initially by patients. Melanoma-specific mortality was 59% lower for routine skin-check detection of invasive melanoma in minimally adjusted models, and this was attenuated to a nonsignificant 32% lower (with CIs that slightly overlapped with 1) after multivariable adjustment including for mitotic rate and ulceration, suggesting that the association was partly explained by patient, sociodemographic, and clinicopathologic prognostic factors associated with routine skin-check detection. The fact that routine skin-check melanoma detection was significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality but not melanoma-specific mortality in the fully adjusted analyses may reflect residual or unmeasured confounding from sociodemographic characteristics (such as education level), medical access, and health-seeking behaviors (such as physical activity) that are independently associated with both routine skin checks and overall mortality.28 Organized cancer screening programs for breast, bowel, and lung cancer have been shown to reduce cancer-specific mortality by approximately 20% to 30%,29,30,31 but there is limited evidence of an association with all-cause mortality owing to sample size constraints, possible harms, and length of follow-up.32,33 In addition, the lower number of melanoma deaths than overall deaths would have contributed to wider CIs for melanoma-specific mortality.

Approximately half (47%) of melanomas were physician detected, either by a routine skin check (35%) or incidentally (12%), compared with 47% patient detected and 6% “other.” In previous Australian34 and international35,36,37 studies, 16% to 27% of melanomas were physician detected, 27% to 44% were patient detected, and 15% to 31% were detected by a partner or family member. We did not ask separately about partner or family member detection in our study questionnaire. Physician-detected melanomas were more likely to be thinner, which is consistent with previous studies.7,34,35

Slower-growing melanomas (low mitotic rate and lentigo subtype) were more likely to be detected at a routine skin check and be thinner at diagnosis, whereas faster-growing melanomas (high mitotic rate and nodular subtype) were more likely to be patient detected and thicker. This phenomenon (a type of length-time bias) is a common limitation of cancer screening programs38 and increases concerns about overdiagnosis; it also helps to explain the observed lack of screening-associated reduction in population melanoma mortality rates.11,12,39,40,41 A rapid patient-driven diagnosis (eg, mobile phone referral) may be a useful adjunct to a melanoma screening program.

Some studies have shown that population-based skin cancer screening programs would not be cost-effective for the health system,13,42,43 whereas other studies suggest that screening may be cost-effective as a single intervention44 or for high-risk groups.14,45 One US study46 of a large-scale melanoma screening program found increased melanoma diagnoses but little impact on subsequent skin surgeries or dermatology visits. The cost-effectiveness of a population melanoma screening program should be reassessed in light of (1) the availability of new and effective, but expensive, therapies for advanced and high-risk melanomas, (2) new diagnostic technologies including artificial intelligence algorithms, and (3) the ability to tailor screening to high-risk groups.2,10,16,17,20,45,47

In the organized skin cancer screening program in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, the participation rate was only 19%.48 In the absence of a structured national melanoma screening program, the prevalence of clinical skin checks conducted opportunistically in Australia is relatively high, with a 2016 to 2017 national survey finding that 37% of Australians aged 45 to 69 years reported a whole-body skin check in the previous 12 months.49 This might be due to Australia’s high melanoma incidence rates and widespread skin cancer prevention and awareness campaigns.50,51,52 We observed a higher odds of melanoma being detected at a routine skin check among men, those with a previous melanoma, those with many moles, patients aged 50 years or older, or those living in nonremote areas. The national survey found similarly higher prevalence of whole-body skin checks in these subgroups, except that skin checks were slightly more prevalent among women.49 A Spanish study found that more melanomas were self-detected among women but that men had more melanomas on locations that were not easily visible (such as the back) than women.35 Worse outcomes for people living in rural areas have been noted previously53 and may reflect barriers to health service access, such as distance from medical services, higher out-of-pocket costs, and fewer dermatology services.54 Although training and confidence in melanoma detection and management varies by clinical practice setting,55 many melanomas in Australia are detected in primary care (56% in this study); therefore, awareness of typical and atypical melanoma features56 is essential for both specialist and generalist physicians as well as the community.

Strengths and Limitations

Although it is known from other studies that melanomas identified on routine skin checks tend to be thinner and result in a better prognosis, the novel aspects of our study are the prospective population-based cohort design, large sample size, and more than 10 years of linked follow-up data that included other primary melanomas and melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality outcomes. The prevalence of risk factors such as many moles, family history, and previous melanoma in our study population of patients with melanoma are similar to other Australian studies57,58,59 and reflect Australia’s high skin cancer incidence.3,60 Another strength is the comprehensive collection of patient, clinical, and histopathologic information enabling adjustment for important confounders. Compared with single-site studies, population-based studies are more generalizable and less subject to referral bias.61

Our study had some limitations. First, our results may be less generalizable to countries with lower skin cancer incidence. Second, because of the observational design of our study, causality could not be confirmed. Further, for people who developed multiple primary melanomas during the follow-up period, we did not have information on how the other melanomas were detected. We could not distinguish whether any patient-detected or incidentally detected melanomas were interval cancers in patients undergoing routine skin checks. Follow-up data for some patients may not have been captured if they moved interstate or overseas.62,63 Because several patient characteristics were associated with mode of detection, and because other factors were associated with each other (such as socioeconomic status with residential remoteness and mitotic rate with Breslow thickness), it is possible that the multivariable models were overadjusted, leading to more conservative estimates of effect and wider CIs.

Conclusions

In this population-based cohort study, we found that melanomas diagnosed through routine skin checks were associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality, but not melanoma-specific mortality, after adjustment for patient, sociodemographic, and clinicopathologic factors. A large randomized clinical trial is needed to provide definitive evidence that screening for skin cancer reduces melanoma-specific and all-cause mortality among people invited (vs not invited) to screen,38 but there are concerns about feasibility.15,64 Our findings could be used to estimate the sample size for a future trial.

eFigure 1. Flowchart Showing Creation of the Analysis Data Set

eFigure 2. Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) Showing Relationships Between Variables and Assessment of Confounding

eReferences

References

- 1.Gordon L, Youl PH, Elwood M, et al. Diagnosis and management costs of suspicious skin lesions from a population-based melanoma screening programme. J Med Screen. 2007;14(2):98-102. doi: 10.1258/096914107781261963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott TM, Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, Gordon LG. Estimated healthcare costs of melanoma in Australia over 3 years post-diagnosis. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(6):805-816. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0341-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. ; for members of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform . Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):472-492. doi: 10.3322/caac.21409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstock MA. Reducing death from melanoma and standards of evidence. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(5):1311-1312. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider JS, Moore DH II, Mendelsohn ML. Screening program reduced melanoma mortality at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 1984 to 1996. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):741-749. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, Youl P, English D. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):450-458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives?: an observational study comparing trends in melanoma mortality in regions with and without screening. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5395-5402. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stang A, Jöckel KH. Does skin cancer screening save lives? a detailed analysis of mortality time trends in Schleswig-Holstein and Germany. Cancer. 2016;122(3):432-437. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janda M, Cust AE, Neale RE, et al. Early detection of melanoma: a consensus report from the Australian Skin and Skin Cancer Research Centre Melanoma Screening Summit. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2020;44(2):111-115. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(4):429-435. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welch HG, Mazer BL, Adamson AS. The rapid rise in cutaneous melanoma diagnoses. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):72-79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2019760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon L, Olsen C, Whiteman DC, Elliott TM, Janda M, Green A. Prevention versus early detection for long-term control of melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas: a cost-effectiveness modelling study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034388. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson ECF, Usher-Smith JA, Emery J, Corrie P, Walter FM. A modeling study of the cost-effectiveness of a risk-stratified surveillance program for melanoma in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2018;21(6):658-668. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cust AE, Aitken JF, Baade PD, Whiteman DC, Soyer HP, Janda M. Why a randomized melanoma screening trial may be a good idea. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(5):1227-1228. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4(1):13-37. doi: 10.2217/mmt-2016-0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Kim CC, Swetter SM, et al. ; Melanoma Prevention Working Group—Pigmented Skin Lesion Sub-Committee . Survival is not the only valuable end point in melanoma screening. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(5):1332-1337. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. ; CheckMate 238 Collaborators . Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824-1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poklepovic AS, Luke JJ. Considering adjuvant therapy for stage II melanoma. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1166-1174. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried L, Tan A, Bajaj S, Liebman TN, Polsky D, Stein JA. Technological advances for the detection of melanoma: advances in diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):983-992. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vuong K, Armstrong BK, Weiderpass E, et al. ; Australian Melanoma Family Study Investigators . Development and external validation of a melanoma risk prediction model based on self-assessed risk factors. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(8):889-896. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeGregori J, Pharoah P, Sasieni P, Swanton C. Cancer screening, surrogates of survival, and the soma. Cancer Cell. 2020;38(4):433-437. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madronio CM, Armstrong BK, Watts CG, et al. Doctors’ recognition and management of melanoma patients’ risk: an Australian population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;45:32-39. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. ; STROBE Initiative . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2033.0.55.001—Census of population and housing: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. March 27, 2018. Accessed April 15, 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~SEIFA%20Basics~5

- 26.Australian Government Department of Health . Australian statistical geography standard - remoteness area. Accessed April 15, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/health-workforce/health-workforce-classifications/australian-statistical-geography-standard-remoteness-area

- 27.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, King SC, Guy GP Jr. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group . Breast-cancer screening—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2353-2358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1504363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576-2594. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steele RJ, Brewster DH. Should we use total mortality rather than cancer specific mortality to judge cancer screening programmes? no. BMJ. 2011;343:d6397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heijnsdijk EAM, Csanádi M, Gini A, et al. All-cause mortality versus cancer-specific mortality as outcome in cancer screening trials: a review and modeling study. Cancer Med. 2019;8(13):6127-6138. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McPherson M, Elwood M, English DR, Baade PD, Youl PH, Aitken JF. Presentation and detection of invasive melanoma in a high-risk population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5):783-792. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avilés-Izquierdo JA, Molina-López I, Rodríguez-Lomba E, Marquez-Rodas I, Suarez-Fernandez R, Lazaro-Ochaita P. Who detects melanoma? impact of detection patterns on characteristics and prognosis of patients with melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(5):967-974. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brady MS, Oliveria SA, Christos PJ, et al. Patterns of detection in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89(2):342-347. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koh HK, Miller DR, Geller AC, Clapp RW, Mercer MB, Lew RA. Who discovers melanoma? patterns from a population-based survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):914-919. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70132-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacklyn G, Bell K, Hayen A. Assessing the efficacy of cancer screening. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(3):2731727. doi: 10.17061/phrp2731727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrara G, Zalaudek I. Is histopathological overdiagnosis of melanoma a good insurance for the future? Melanoma Manag. 2015;2(1):21-25. doi: 10.2217/mmt.14.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, Youl PH, Ring IT, Lowe JB. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):105-114. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(8):903-910. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon LG, Brynes J, Baade PD, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a skin awareness intervention for early detection of skin cancer targeting men older than 50 years. Value Health. 2017;20(4):593-601. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon LG, Rowell D. Health system costs of skin cancer and cost-effectiveness of skin cancer prevention and screening: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(2):141-149. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Losina E, Walensky RP, Geller A, et al. Visual screening for malignant melanoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(1):21-28. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.1.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watts CG, Cust AE, Menzies SW, Mann GJ, Morton RL. Cost-effectiveness of skin surveillance through a specialized clinic for patients at high risk of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):63-71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.4308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinstock MA, Ferris LK, Saul MI, et al. Downstream consequences of melanoma screening in a community practice setting: first results. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3152-3156. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hübner J, Waldmann A, Eisemann N, et al. Association between risk factors and detection of cutaneous melanoma in the setting of a population-based skin cancer screening. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2018;27(6):563-569. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):201-211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reyes-Marcelino G, Tabbakh T, Espinoza D, et al. Prevalence of skin examination behaviours among Australians over time. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;70:101874. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montague M, Borland R, Sinclair C. Slip! slop! slap! and SunSmart, 1980-2000: skin cancer control and 20 years of population-based campaigning. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(3):290-305. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabbakh T, Volkov A, Wakefield M, Dobbinson S. Implementation of the SunSmart program and population sun protection behaviour in Melbourne, Australia: results from cross-sectional summer surveys from 1987 to 2017. PLoS Med. 2019;16(10):e1002932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez D, Kite J, Dunlop SM, et al. Exposure to the ‘Dark Side of Tanning’ skin cancer prevention mass media campaign and its association with tanning attitudes in New South Wales, Australia. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(2):336-346. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coory M, Smithers M, Aitken J, Baade P, Ring I. Urban-rural differences in survival from cutaneous melanoma in Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30(1):71-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2006.tb00089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swerissen H, Duckett S, Moran G. Mapping Primary Care in Australia. Grattan Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith AL, Watts CG, Robinson S, et al. ; Australian Melanoma Centre of Research Excellence Study Group . GPs’ involvement in diagnosing, treating, and referring patients with suspected or confirmed primary cutaneous melanoma: a qualitative study. BJGP Open. 2020;4(2):bjgpopen20X101028. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mar VJ, Chamberlain AJ, Kelly JW, Murray WK, Thompson JF. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of melanoma: melanomas that lack classical clinical features. Med J Aust. 2017;207(8):348-350. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cust AE, Drummond M, Bishop DT, et al. Associations of pigmentary and naevus phenotype with melanoma risk in two populations with comparable ancestry but contrasting levels of ambient sun exposure. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(10):1874-1885. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cust AE, Schmid H, Maskiell JA, et al. Population-based, case-control-family design to investigate genetic and environmental influences on melanoma risk: Australian Melanoma Family Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(12):1541-1554. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Youlden DR, Youl PH, Soyer HP, Aitken JF, Baade PD. Distribution of subsequent primary invasive melanomas following a first primary invasive or in situ melanoma Queensland, Australia, 1982-2010. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(5):526-534. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.9852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Skin Cancer in Australia. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2016.

- 61.Leeflang MMG, Bossuyt PMM, Irwig L. Diagnostic test accuracy may vary with prevalence: implications for evidence-based diagnosis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(1):5-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagle CM, Purdie DM, Webb PM, Green AC, Bain CJ. Searching for cancer deaths in Australia: National Death Index vs. cancer registries. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7(1):41-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lawrence G, Dinh I, Taylor L. The Centre for Health Record Linkage: a new resource for health services research and evaluation. Health Inf Manag. 2008;37(2):60-62. doi: 10.1177/183335830803700208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halvorsen JA, Løberg M, Gjersvik P, et al. Why a randomized melanoma screening trial is not a good idea. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):532-533. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flowchart Showing Creation of the Analysis Data Set

eFigure 2. Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) Showing Relationships Between Variables and Assessment of Confounding

eReferences