Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are the key effector cells mediating the occurrence and development of liver fibrosis, while aerobic glycolysis is an important metabolic characteristic of HSC activation. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) induces aerobic glycolysis and is a driving factor for metabolic reprogramming. The occurrence of glycolysis depends on a high glucose uptake level. Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) is the most widely distributed glucose transporter in the body and mainly participates in the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism, thus affecting cell proliferation and growth. However, little is known about the relationship between TGF-β1 and GLUT1 in the process of liver fibrosis and the molecular mechanism underlying the promotion of aerobic glycolysis in HSCs.

AIM

To investigate the mechanisms of action of GLUT1, TGF-β1 and aerobic glycolysis in the process of HSC activation during liver fibrosis.

METHODS

Immunohistochemical staining and immunofluorescence assays were used to examine GLUT1 expression in fibrotic liver tissue. A Seahorse extracellular flux (XF) analyzer was used to examine changes in aerobic glycolytic flux, lactate production levels and glucose consumption levels in HSCs upon TGF-β1 stimulation. The mechanism by which TGF-β1 induces GLUT1 protein expression in HSCs was further explored by inhibiting/promoting the TGF-β1/mothers-against-decapentaplegic-homolog 2/3 (Smad2/3) signaling pathway and inhibiting the p38 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathways. In addition, GLUT1 expression was silenced to observe changes in the growth and proliferation of HSCs. Finally, a GLUT1 inhibitor was used to verify the in vivo effects of GLUT1 on a mouse model of liver fibrosis.

RESULTS

GLUT1 protein expression was increased in both mouse and human fibrotic liver tissues. In addition, immunofluorescence staining revealed colocalization of GLUT1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin proteins, indicating that GLUT1 expression was related to the development of liver fibrosis. TGF-β1 caused an increase in aerobic glycolysis in HSCs and induced GLUT1 expression in HSCs by activating the Smad, p38 MAPK and P13K/AKT signaling pathways. The p38 MAPK and Smad pathways synergistically affected the induction of GLUT1 expression. GLUT1 inhibition eliminated the effect of TGF-β1 on HSC proliferation and migration. A GLUT1 inhibitor was administered in a mouse model of liver fibrosis, and GLUT1 inhibition reduced the degree of liver inflammation and liver fibrosis.

CONCLUSION

TGF-β1 induces GLUT1 expression in HSCs, a process related to liver fibrosis progression. In vitro experiments revealed that TGF-β1-induced GLUT1 expression might be one of the mechanisms mediating the metabolic reprogramming of HSCs. In addition, in vivo experiments also indicated that the GLUT1 protein promotes the occurrence and development of liver fibrosis.

Keywords: Gene regulation, Glycolysis, Liver fibrosis, Glucose transporter 1, Transforming growth factor-β1

Core Tip: Liver fibrosis is a repair response of the liver to various chronic injuries. However, fibrosis may eventually evolve into liver cirrhosis or even liver cancer if it progresses. Hepatic stellate cell activation is the initiating factor for liver fibrosis. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is a pleiotropic cytokine that induces aerobic glycolysis. Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) regulates glucose metabolism. This study examined the effects of TGF-β1-mediated pathways on GLUT1 expression in vivo and in vitro, explored the relationship between GLUT1 and TGF-β1 and further investigated the potential underlying mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Liver fibrosis is the inevitable result of chronic liver inflammation caused by various etiologies. With progressive destruction of liver parenchymal cells, liver fibrosis eventually develops into liver cirrhosis and even liver cancer[1,2]. Although liver cirrhosis and liver cancer are irreversible, liver fibrosis can be reversed. Therefore, the mechanism of and clinical studies on liver fibrosis have always been the focus of liver disease research. The main pathological feature of liver fibrosis is the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), while the key initiating factors are activation of quiescent hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and transformation of their phenotypes and functions[3]. The transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) pathway is the key fibrogenic pathway that drives HSC activation and induces ECM production. HSC activation requires metabolic reprogramming and a continuous energy supply[4,5]. Aerobic glycolysis is an important metabolic characteristic of the transdifferentiation of quiescent stellate cells, a process similar to the Warburg effect in tumor cells, and the core metabolic changes include a transition from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis[6]. Dysregulated glycolysis has been implicated in experimental models of lung and liver fibrosis, and inhibition of glycolysis reduces ECM accumulation[7]. In view of the mechanisms involved, targeting and inhibiting the metabolic reprogramming of activated HSCs during liver fibrosis may be a promising anti-liver fibrosis strategy.

TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine and a major profibrotic cytokine that regulates cell differentiation, cell proliferation and ECM production and directly regulates multiple cellular signal transduction networks[8]. In the canonical TGF-β1/mothers-against-decapentaplegic-homolog 2/3 (Smad2/3) pathway, ligands induce the assembly of the TGF-β1 receptor I (TβRI)/TGF-β1 receptor II (TβRII) heterocomplex, which targets Smad4 via Smad2 and Smad3 proteins to form the Smad complex, leading to phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Smad2/3; this R-Smad/Co-Smad4 complex translocates to the nucleus where it binds to DNA either directly or in association with other DNA-binding proteins[9-11]. Phosphorylated Smad2/3 binds to specific Smad binding elements (SBEs) in gene promoter regions to activate/suppress the expression of target genes[12,13]. In addition to Smads, TGF-β1 also triggers other protein-mediated signaling pathways, e.g., p38, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). Some functions of TGF-β1 have been studied in depth, such as the mediation of cell differentiation and proliferation. However, TGF-β1 has recently been reported to induce aerobic glycolysis and is considered a driving factor in metabolic reprogramming[14]. TGF-β is also a strong activator of glycolysis in mesenchymal cells[15]. Extracellular accumulation of lactic acid induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by directly reconstituting the ECM and releasing activated TGF-β1. EMT induced by TGF-β in hepatocellular carcinoma cells reprograms lipid metabolism to sustain the elevated energy requirements associated with this process[16]. Research on the mechanism of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis has shown that TGF-β1-induced aerobic glycolysis causes lactic acid accumulation and changes the cellular microenvironment, thereby activating latent TGF-β1 in the ECM and eventually forming a positive feedback loop to promote the effects of TGF-β1[17].

Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) is a member of the GLUT transporter family, the most conserved and most widely distributed glucose transporter in mammals and the main transporter regulating glucose uptake[18]. An increasing number of studies have found that GLUT1 plays an important role in accelerated metabolism. Research on the mechanism of neurodegenerative diseases has revealed that GLUT1 controls the activation of microglia by promoting aerobic glycolysis[19]. GLUT1 enhances the stimulating effect of TGF-β1 on mesangial cells, breast cancer cells and pancreatic cancer cells. As glucose uptake increases during TGF-β1-induced EMT of breast cancer cells, GLUT1 expression also increases and is correlated with EMT markers (including E-cadherin and vimentin). GLUT1 is the key mediator of the aerobic glycolysis phenotype in ovarian cancer and is required to maintain a high level of basic aerobic glycolysis. In models of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, GLUT1-dependent aerobic glycolysis has been reported to be essential for pulmonary parenchymal fibrosis[20-23]. Certain signaling molecules (such as cAMP, p53, PI3K and AKT) reduce alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) protein expression in primary mouse fibroblasts by inhibiting GLUT1 expression. Exosomes secreted by activated HSCs affect the metabolic switch of liver nonparenchymal cells through delivery of the glycolysis-related proteins GLUT1 and PKM2; GLUT1 is involved in metabolic reprogramming of HSCs[24]. TGF-β1 and GLUT1 play important regulatory roles in metabolic reprogramming. To date, however, researchers have not explored whether the increases in TGF-β1 and GLUT1 Levels during HSC activation are related. Therefore, this study investigated the effect of the TGF-β1 signaling pathway on the regulation of GLUT1 and aerobic glycolysis. We hypothesized that TGF-β1 drives HSC activation and aerobic glycolysis by inducing GLUT1 expression, thereby promoting liver fibrosis progression. As shown in the present study, GLUT1 expression was significantly increased in mouse and human fibrotic liver tissue samples. Further in vitro experiments showed that the aerobic glycolysis capacity of HSCs was enhanced and GLUT1 expression increased with increasing TGF-β1 Levels. Inhibition/ promotion of the Smad2/3 signaling pathway and inhibition of the p38 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways confirmed that TGF-β1 induced GLUT1 expression by targeting the pSmad2/3, p38 and PI3K/AKT pathways, thus promoting HSC activation. Finally, administration of a specific GLUT1 inhibitor in a mouse model of liver fibrosis resulted in a significant reduction in liver fibrosis. Based on these findings, the TGF-β1 signaling pathway enhances aerobic glycolysis by promoting GLUT1 expression, thereby promoting the development of liver fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

The TGF-β1 antibody was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, United States); antibodies against GLUT1, p-Smad2/3, Smad2/3, p-P38, p-AKT and desmin were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, United States), and the tubulin antibody was purchased from Research Diagnostics (Flanders, NJ, United States). The anti-α-SMA antibody, carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), corn oil, OptiPrep and other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States) and Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, United States). A TβRI/II inhibitor (APExBIO Technology, United States) was used at 2 μmol/L. Inhibitors of p38 MAPK and PI3K, namely, SB203580 and LY294002, respectively, were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, United States). The Smad3 inhibitors SIS3 and phloretin were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, United States).

Generation of a mouse model of liver fibrosis

The animal protocol was designed to minimize pain or discomfort to the animals. The animals were acclimated to laboratory conditions (22 °C, 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle, 50% humidity, ad libitum access to food and water) for 1 wk prior to experimentation. The methods and experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Mice (C57BL6, eight to ten weeks old) were housed in standard conditions, and sex-matched mice were treated with 2.0 μL/g body weight CCl4 [diluted 1:10 (v/v) with corn oil] or corn oil as a control by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections three times per week for 4 wk[25]. Mice were challenged with CCl4 or corn oil (control), followed by an i.p. injection of phloretin (10 mg/kg, three times per week for 2 wk) or 0.9% saline (vehicle). Mice were sacrificed at 48 h after the experiment ended, and tissues were harvested.

Patient liver samples

Normal and liver fibrosis tissue samples were obtained from patients treated at the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (Guiyang, China). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Western blot analysis

Immunoblotting was performed using whole-liver tissue lysates or whole-cell lysates prepared in buffer containing 1% NP-40 as described previously[26]. Total proteins were extracted and quantified using Bradford protein quantification kits. Protein samples (40 μg each) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. On the next day, signals were developed with an electrochemiluminescence detection kit after incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies.

Cells and cell culture

Primary mouse HSCs were isolated and cultured as described previously[26]. Briefly, cells were isolated from livers through in situ liver perfusion with pronase, Liberase and collagenase followed by density gradient centrifugation. The dispersed cell suspension was filtered and gradiently centrifuged for 2 min to remove hepatocytes. The remaining cell fraction was washed and resuspended in 11.5% OptiPrep and then gently transferred to a tube containing 15% OptiPrep at the bottom, followed by PBS addition as the top layer. The cell fraction was then centrifuged at 1400 rpm/min for 20 min. The HSC fraction layer was obtained at the interface between the top and intermediate layers. The purity of the HSC fraction was estimated based on autofluorescence 1 d after isolation and was always greater than 97%. Flow cytometry was used to identify the purity of primary cells. In brief, the cells were digested with trypsin, centrifuged at 1000 rpm/min for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in EP tubes (100 μL/tube) and centrifuged at 2000 rpm/min for 6 min. Then, the supernatant was discarded, 100 μL of PBS was added, and the cells were resuspended and dispersed. A mouse monoclonal antibody against desmin (desmin is a typical molecular marker of HSCs) was added, and the cells were incubated at 1:100 for 1.5 h and centrifuged at 2000 rpm/min for 6 min. Centrifugation was repeated twice. The cells were resuspended and dispersed by adding 100 μL of PBS. Fluorescence-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000) was added, followed by incubation at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark. Next, 1 mL of PBS was added to each tube, followed by centrifugation at 2000 rpm/min for 6 min, which was repeated twice. Finally, 0.5 mL of PBS was added to resuspend the cells, and then the cells were subjected to flow cytometry measurements. HSCs were also confirmed to lack E-cadherin expression. Cell viability was also examined, and HSCs were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics as described previously[26]. Cells were starved or treated on day 2 after isolation, and the duration of starvation or treatment is described in each figure legend. The duration of the whole experiment was 5-7 d after HSC isolation, and cells at passages 1-2 were used (as cells were passaged from regular culture flasks to experimental cell culture wells for some experiments).

Histological and immunohistochemical studies

Liver samples were fixed with formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and processed routinely for Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red staining. Antibodies used for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of GLUT1 and α-SMA were purchased from Abcam Technology, United States.

RNA interference

Cells were transfected with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The siRNAs used were an siRNA mix targeting sequences in Smad2 and Smad3 purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (siRNA Smad2/3) and siRNAs targeting four different sequences of Smad4 purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. GLUT1 siRNA was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The sequences of the siRNAs used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Small interfering RNA sequences

|

|

Forward

|

Reverse

|

| siGlut1-1 | 5′-CACCGGGAGTGACAAAGACTTTGTTCAAGCA-3′ | 5′-GATCCAAAAAAGGGAGTGACAAAGACTTCTC-3′ |

| Negative control | 5′-ATCCGACTTCATAAGGCGCATGCT-3′ | 5′-AGTATTCCGCGTACGAAGTTCTGC-3′ |

| siRNA Smad4 targeting four different sequences1 | ||

| GCAAUUGAAAGUUUGGUAA, CCCACAACCUUUAGACUGA, GAAUCCAUAUCACUACGAA and GUACAGAGUUACUACUUAG | ||

| siRNA Smad2/31 | Sense | Antisense |

| sc-37239A | CUUGCUGGAUUGAACUUCAtt | UGAAGUUCAAUCCAGCAAGtt |

| sc-37239B | CCGUCGUAGUAUUCAUGUAtt | UACAUGAAUACUACGACGGtt |

| sc-37239C | CUGACUCCUUGUUUAAUGAtt | UCAUUAAACAAGGAGUCAGtt |

| sc-37239D | GGAAGCUGAGAGUUAUAGAtt | UCUAUAACUCUCAGCUUCCtt |

Purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. sc-37239: Smad2/3 siRNA (m) is a pool of four different siRNA duplexes.

Glycolytic function assay and lactate measurements

Primary mouse HSCs were plated on XF96 cell culture microplates. The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), a glycolytic flux parameter, was measured with a Seahorse XF96 bioanalyzer using the XF Glycolysis Stress Test kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (102194-100, Seahorse Bioscience). Lactate levels were measured spectrophotometrically in 700 μL of supernatants from cells receiving the corresponding treatment using standard enzymatic methods.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

Primary mouse HSCs were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 3000 cells per well. CCK-8 reagent was added to each well every 24 h, and the plates were incubated for an additional 1 h at 37 °C and measured by recording the absorbance at 450 nm with an Elx800™ spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, United States).

Biochemical function analysis

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels in mouse serum samples and the supernatant of cell culture medium were detected using an automatic biochemical analyzer (Siemens Advia 1650; Siemens, Bensheim, Germany).

RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction

GLUT1, hexokinase 2 (HK-2), pyruvate kinase 2 (PKM-2) and α-SMA mRNA levels were determined using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with a SYBR Green Master Mix Kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, United States). The primer sequences used are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primer sequences for real-time polymerase chain reaction

|

Gene

|

Forward sequence

|

Reverse sequence

|

| HK2 | 5’-GGGTAGCCACGGAGTACAAA-3’ | 5’-TGGATTGAAAGCCAACTTCC-3’ |

| GLUT1 | 5’-GCTTCTCCAACTGGACCTC-3’ | 5’-AAGAAGAGCACGAGGAGCAC-3’ |

| PKM2 | 5’-TGGGATGGAAACTGTGAAGAG-3’ | 5’-CGGAGTTCCTCGAATAGCTG-3’ |

| α-SMA | 5’-AAGAGCATCCGACACTGCTGAC-3’ | 5’-AGCACAGCCTGAATAGCCACATAC-3’ |

Transwell migration assay

The migratory properties of HSCs were assessed using a Transwell assay. Cells were seeded at a density of 4 × 105 cells/well in the upper compartment of Transwell chambers with serum-free medium, and the lower compartment contained 700 μL of 5% glucose-containing medium per well. Migration was subsequently observed and measured.

Tissue immunofluorescence staining

Tissue sections were placed at room temperature for 10 min and deparaffinized in water for further antigen retrieval. After the sections were dried slightly, a histochemical pen was used to draw circles around the tissue, and 3%-5% BSA was added dropwise inside the circle for blocking, followed by incubation for 30 min. The primary antibody was added dropwise at the recommended ratio to the sections, and the sections were placed in a refrigerator (4 °C) and incubated overnight. After 3 washes, the sections were incubated with a FITC (CK-18)-labeled secondary antibody at room temperature for 45 min, and nuclei were stained with DAPI (300 nmol/L) for 1-5 min. After 3 washes, an antifluorescence quencher was added, and the sections were sealed with resin. Photographs of random fields were taken under an upright fluorescence microscope (ZEISS Axiovert).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Student’s t test (SigmaPlot, SPSS 17.0, United States) to determine differences between two groups and are presented as the mean ± SE. For comparisons between multiple groups, three-way analysis of variance was performed, followed by t tests with Bonferroni correction using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). In addition, a log-rank test was used for survival analysis. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 (aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01).

RESULTS

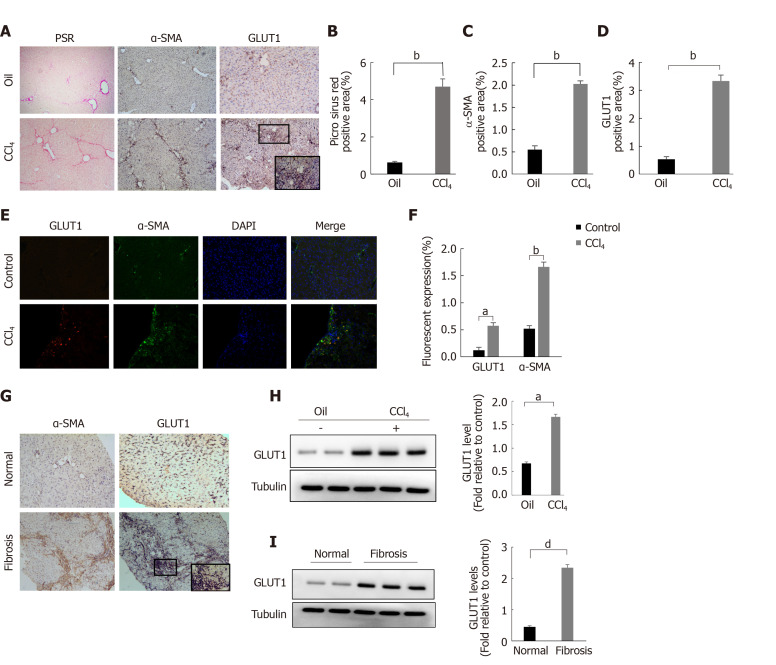

GLUT1 expression is correlated with liver fibrosis progression

The classic mouse model of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis was used to first clarify whether GLUT1 is related to liver fibrosis. Successful establishment of the liver fibrosis model was confirmed by Sirius red staining and α-SMA IHC staining (Figure 1A-C). Notably, a significant increase in GLUT1 expression was detected in the liver tissue specimens from the model group (Figure 1A and D). Subsequently, tissue immunofluorescence staining was performed, and the results showed significantly increased GLUT1 expression in liver tissue samples from the CCl4 liver fibrosis model. More importantly, GLUT1 colocalized with α-SMA, indicating a correlation between GLUT1 and liver fibrosis (Figure 1E). IHC staining for GLUT1 and α-SMA was performed using human liver fibrosis specimens and liver specimens from a healthy control group; as expected, GLUT1 expression was significantly higher in the human liver fibrosis specimens (Figure 1F). Finally, whole-liver lysates were prepared from human liver tissue specimens and specimens from the mouse liver fibrosis model, and GLUT1 protein expression was analyzed. The results were consistent with the IHC data (Figure 1G-H). In summary, these results indicate that GLUT1 expression is related to liver fibrosis progression.

Figure 1.

Glucose transporter 1 expression is correlated with liver fibrosis progression. A-D: The classic mouse model of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis was used to first clarify whether glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) is related to liver fibrosis. Sirius red staining and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) immunohistochemical (IHC) staining were used to confirm that the liver fibrosis model was successfully established, and then the mice were randomly divided into the CCl4 group and the control oil group (n = 6-10 mice/group) (A); Evaluation of liver fibrosis using Sirius red staining (B); Determination of the area ratio of positive IHC staining for α-SMA in the mouse CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model (C); GLUT1 expression was more abundant in the liver tissue samples from the model group (D); E and F: Immunofluorescence staining for GLUT1 (red) and α-SMA (green) in the CCl4 model. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar for immunofluorescence staining, 200 μm; scale bars for IHC staining and Sirius red staining, 200 μm; G: IHC staining for α-SMA and GLUT1 in the healthy control and liver fibrosis groups (scale bar, 100 μm); H: Western blot analysis of changes in GLUT1 protein levels in the oil group and the CCl4 model group; I: Western blot analysis of GLUT1 protein expression in human liver tissues from the healthy control group and the liver fibrosis group. Data in B-D, G and H are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistically significant differences were detected (compared with the oil group, aP < 0.05 and bP < 0.01; compared with the healthy control group, dP < 0.05). GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1; α-SMA: Alpha-smooth muscle actin.

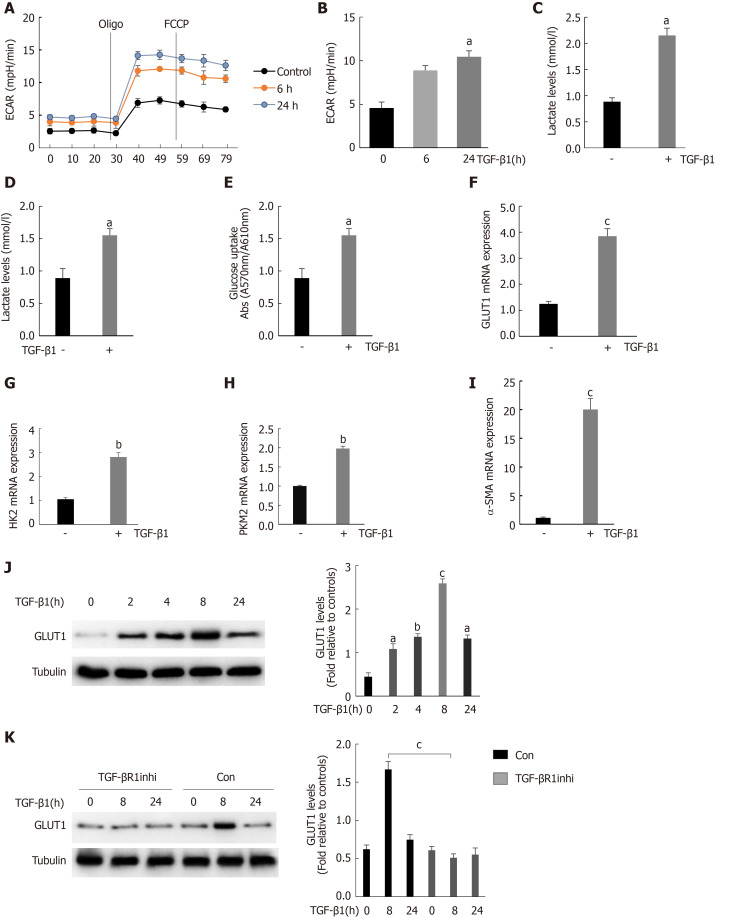

TGF-β1 stimulates HSC activation by inducing GLUT1 expression and promoting aerobic glycolysis

We found that GLUT1 colocalized with α-SMA, indicating that GLUT1 expression was increased mainly in activated HSCs because α-SMA is a major marker of HSC transdifferentiation. TGF-β1 is a very important profibrotic factor and regulates metabolic reprogramming in pulmonary fibrosis[27], as reported in some studies. Therefore, we questioned whether the increase in GLUT1 expression in liver fibrosis and TGF-β1 are related. This study first determined the effect of TGF-β1 on glycolysis in HSCs. To assess the dose responses to TGF-β1, we incubated HSCs with different TGF-β1 concentrations ranging from 3 ng/mL to 5 ng/mL, and the results showed similar effects on GLUT1 protein levels (Supplementary Figure 1). Therefore, a TGF-β1 concentration of 3 ng/mL was used for subsequent experiments. Mouse primary HSCs were isolated and cultured, and the cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 for 24 h prior to the experiments. TGF-β1 stimulation led to an early and continuous increase in the ECAR (an indicator of extracellular acid production) in HSCs, indicating that glycolysis was enhanced in these cells (Figure 2A and B). In addition, the intracellular and extracellular levels (in the medium) of lactic acid were examined to further confirm the glycolytic changes in HSCs. Both intracellular and extracellular lactic acid levels were significantly increased. Consistent with the increase in glycolysis, the level of glucose consumption also increased in these cells (Figure 2C and D). Therefore, TGF-β1 induces glycolysis during the process of HSC transdifferentiation. The expression levels of key glycolytic enzymes in these cells were evaluated; the expression levels of HK-2, PKM-2 and GLUT1 were upregulated, and the increase in GLUT1 expression was particularly significant (Figure 2F-H). Based on these findings, the increase in glycolysis during HSC transdifferentiation is related to the upregulation of key glycolysis enzymes. Similarly, the expression of α-SMA, a marker of transdifferentiation, also increased during the TGF-β1-mediated activation of HSCs (Figure 2I). GLUT1 protein expression was examined at various time points after stimulating HSCs with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) to determine whether TGF-β1 stimulates GLUT1 expression in a time-dependent manner, and the results showed that GLUT1 expression increased 2 h after stimulation with TGF-β1 and peaked at 8 h. These results indicate a time-dependent relationship between the increase in GLUT1 expression and TGF-β1 stimulation, which is consistent with the early increase in aerobic glycolysis in HSCs (Figure 2J). Finally, the addition of an inhibitor of the type 1 TGF-β1 receptor inhibited TGF-β1-induced GLUT1 expression in HSCs, suggesting that GLUT1 induction was mediated by TGF-β1 (Figure 2K). Based on these data, TGF-β1 is involved in glycolysis during HSC transdifferentiation and mediates GLUT1 expression, thereby promoting HSC transdifferentiation.

Figure 2.

Stimulation of hepatic stellate cells with transforming growth factor-β1 induces glucose transporter 1 expression and promotes glycolysis. A: Serum-starved (for 20 h) primary mouse hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) were seeded into Seahorse XF-24 cell culture microplates (5 × 104 cells/well). The cells were first treated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (3 ng/mL) for 0, 6 or 24 h, followed by sequential treatment with oligomycin (Oligo) and carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP). The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) was recorded in real time; B: The basic ECAR. n = 6; the mean ± SE; aP < 0.05 compared to the level before TGF-β1 treatment (0 h); unpaired t test; C and D: Mouse HSCs were treated with or without TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 24 h. The cells were then lysed, and the lactic acid contents in the cell lysate (C) and the culture medium (D) were examined; E: Determination of glucose consumption in the culture medium; F-I: Mouse HSCs were treated with or without TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 24 h. RNA was purified, and RT-PCR was performed to examine the expression levels of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) (F), HK-2 (G), PKM-2 (H) and α-SMA (I), n = 5, the mean ± SE; aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 and cP < 0.001 compared with those at 0 h or those in the TGF-β1-untreated group; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); J: Western blot analysis of the expression levels of GLUT1 and tubulin at various time points after HSCs were treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL); K: Examination of the changes in GLUT1 and tubulin levels after sequential treatment with a type 1 TGF-β receptor inhibitor (LY2109761, 2 μm) for 1 h and then with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 0, 8 or 24 h. All experiments shown in A-E and F-I were performed 2-3 times. Inhi: Inhibitor; Con: Control; FCCP: Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; ECAR: Extracellular acidification rate; GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor-β1.

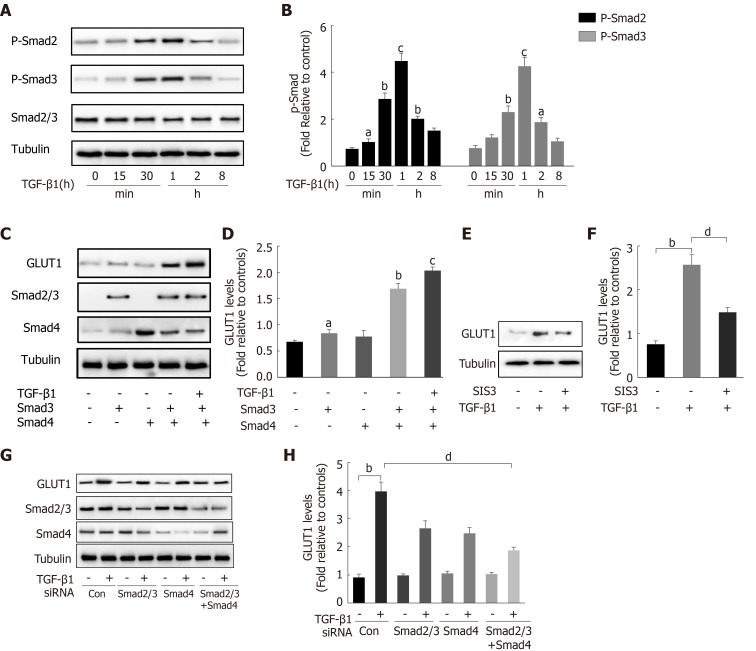

TGF-β1 induces GLUT1 expression through the Smad pathway

After finding that TGF-β1 stimulation induces GLUT1 expression, the specific mechanism by which TGF-β1 induces GLUT1 expression was further explored. Changes in the expression levels of Smad proteins in the canonical pathway activated by TGF-β1 stimulation were first examined. Western blot analysis revealed a time-dependent relationship between Smad2/Smad3 phosphorylation and TGF-β1 stimulation (Figure 3A and B), and phosphorylation occurred at time points close to when GLUT1 expression increased. Next, the direct role of Smads in GLUT1 induction was explored. Smad3 or Smad4 overexpression plasmids were first transiently transfected into HSCs, and then certain groups of HSCs were induced with TGF-β1 for 4 h. Smad3 or Smad4 overexpression promoted GLUT1 expression, and TGF-β1 addition amplified these effects, resulting in a further increase in GLUT1 expression (Figure 3C and D). Smad2/3 and/or Smad4 siRNAs were used to silence their expression levels and to better understand the roles of Smads in the relationship between TGF-β1 and GLUT1 expression, and the analysis performed at 48 h after the transfection of Smad2/3 and/or Smad4 siRNAs showed that TGF-β1-mediated GLUT1 expression was significantly reduced. This change was more significant and the decrease in GLUT1 expression was more substantial when the cells were transfected simultaneously with both siRNAs (Figure 3G and H). Finally, HSCs were sequentially treated with the Smad inhibitor SIS3 for 2 h and then with TGF-β1 for 4 h, resulting in a significant decrease in GLUT1 protein expression (Figure 3E and F). These results preliminarily indicate the important regulatory role of Smad proteins in TGF-β1-mediated GLUT1 expression and suggest that Smad proteins directly participate in the regulation of GLUT1 by TGF-β1.

Figure 3.

Transforming growth factor-β1 induces glucose transporter 1 expression through the Smad pathway. A and B: Serum-starved (for 20 h) primary mouse hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) were treated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (3 ng/mL) and examined at various time points. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (A). Quantitative analysis of the levels of the p-Smad2 and p-Smad3 proteins in five independent experiments (B); C and D: After transiently transfecting HSCs with 2 μg of Smad3 and/or Smad4 expression plasmids, the cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 4 h. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used as a transfection control. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (C). Quantitative analysis of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) protein expression in five independent experiments (D); E and F: HSCs were first pretreated with a Smad3 inhibitor (SIS3, 20 μm) for 1 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 4 h. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (E). Quantitative analysis of the GLUT1 protein level in five independent experiments (F); G and H: Mouse primary HSCs were transfected with 20 μmol/L control small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or siRNAs targeting Smad2/3 and Smad4. After transfection in serum-free medium for 48 h, the cells were treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 4 h. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (G). Quantitative analysis of the GLUT1 protein level in five independent experiments (H) (the mean ± SE; aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 and cP < 0.001 compared with that in the group of cells without TGF-β1; dP < 0.05 for the comparison of the groups treated with TGF-β1 and the groups treated with TGF-β1 and different additional reagents; Student’s t test). GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor-β1; Con: Control; siRNAs: Small interfering RNAs.

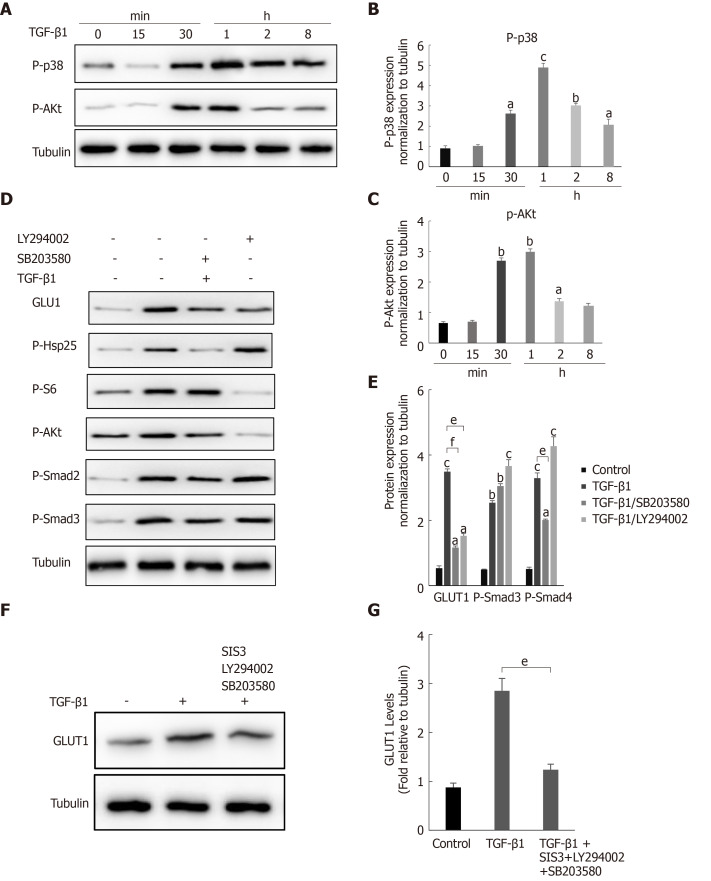

The noncanonical p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways are also involved in TGF-β1-mediated GLUT1 induction

During fibrosis development, TGF-β1 activates not only the canonical Smad pathway but also noncanonical pathways (such as the PI3K/AKT and p38 MAPK signaling pathways). In addition, the Smad pathway and non-Smad pathways are mutually dependent[28]. Therefore, we questioned whether a non-Smad pathway is involved in the TGF-β1-mediated induction of GLUT1. Changes in the phosphorylation levels of p38 and AKT in HSCs after TGF-β1 stimulation were examined to answer this question. Western blot analyses showed increased levels of phosphorylated p38 and AKT in HSCs after TGF-β1 treatment (Figure 4A-C). HSCs were pretreated with the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 1 h and then induced with TGF-β1 to understand the bridging role of p38 MAPK and AKT in TGF-β1-mediated GLUT1 expression. Western blot analyses showed that p-AKT activity was significantly inhibited and that GLUT1 protein expression was significantly reduced (Figure 4D). S6 ribosomal protein and heat shock protein 25 (Hsp25) are downstream proteins in the PI3K/AKT and p38 MAPK pathways, and their phosphorylation was also inhibited. Addition of the p38 inhibitor reduced the phosphorylation of the S6 protein, and the phosphorylation level of Smad2 was also affected; however, Smad3 was not significantly affected (Figure 4D and E). The above results indicate that (1) GLUT1 expression in HSCs did not rely solely on the TGF-β1-mediated Smad pathway, i.e., the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways were also involved in TGF-β1-mediated GLUT1 expression, and (2) TGF-β1-mediated pathways did not act independently, as mutual restrictions and interactions between the pathways were observed. Based on the results described above, the effects of inhibiting the Smad3, p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways on GLUT1 expression were analyzed, and the simultaneous addition of inhibitors of the Smad3, p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways significantly reduced TGF-β1-mediated GLUT1 expression (Figure 4F and G). In summary, TGF-β1 requires the participation of non-Smad pathways to induce GLUT1 expression during HSC activation.

Figure 4.

The noncanonical p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways are also involved in transforming growth factor-β1-mediated glucose transporter 1 expression. A-C: Serum-starved (for 20 h) primary mouse hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) were treated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (3 ng/mL) and examined at different time points. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (A). Five independent experiments were performed to quantitatively analyze the levels of phosphorylated p38 (B) MAPK and AKT (C); D and E: HSCs cultured in serum-free medium were pretreated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μm) or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μm) for 1 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 4 h. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (D). Quantitative analysis of the levels of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 proteins (E); F and G: HSCs cultured in serum-free medium were pretreated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μm), the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μm) and the Smad inhibitor SIS3 (20 μm) for 1 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 4 h. Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (F). Quantitative analysis of the GLUT1 protein level (G) (the mean ± SE; aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 and cP < 0.001 compared with the TGF-β1-treated group or the TGF-β1-untreated group, dP < 0.05, eP < 0.01 and fP < 0.001 for the comparison of the group treated with TGF-β1 and the groups treated with TGF-β1 and the corresponding inhibitors; Student’s t test). GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor-β1.

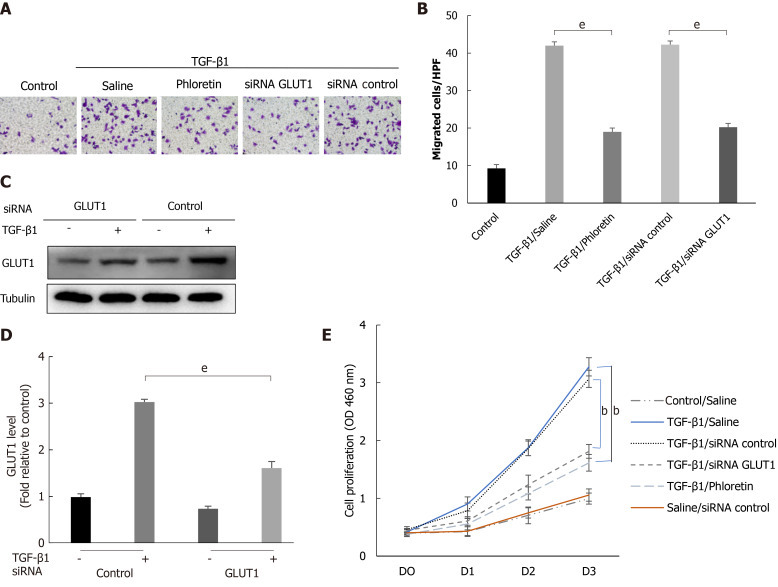

The effect of GLUT1 on HSC migration and proliferation

Cells were first treated with phloretin (a specific inhibitor of GLUT1) for 30 min or transfected with an siRNA targeting GLUT1, followed by treatment with TGF-β1 for 4 h. The targeted inhibition of GLUT1 by phloretin and the siRNA suppressed the effect of TGF-β1 on the migration and proliferation of HSCs (Figure 5A, B and E). Western blot analyses also showed that siRNA transfection effectively inhibited TGF-β1-induced GLUT1 expression (Figure 5C and D). Therefore, inhibition of GLUT1 expression reverses the effect of TGF-β1 on the migration and proliferation of HSCs and delays the process of HSC transdifferentiation into myofibroblasts. No noticeable effect of the control siRNA on proliferation was identified between TGF-β1-treated cells and TGF-β1/siRNA-control-treated cells or between control/saline-treated cells and saline/siRNA-control-treated cells (Figure 5E). In addition, no obvious effect of siRNA interference on cell viability (Supplementary Figure 2) or the expression of TGF-β receptors was found (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 5.

The effect of glucose transporter 1 on the growth and proliferation of hepatic stellate cell. Mouse primary hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) were 1) pretreated with the glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) inhibitor phloretin (50 μm) for 30 min and then treated with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (3 ng/mL) for 4 h or 2) transiently transfected with small interfering RNAs that inhibited GLUT1 expression, cultured in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with TGF-β1 (3 ng/mL) for 4 h. A: Cells were seeded in serum-free medium (4 × 105 cells/well) in the upper chambers of a Transwell system. The lower chambers were filled with 5% glucose medium (700 μL per well). Changes in cell migration were observed. Representative images of crystal violet staining are shown; B: Quantitative data showing the number of migrating cells in each group; C: Western blot analysis using specific antibodies; D: Quantitative analysis of GLUT1 protein expression in three independent experiments; E: The effect of GLUT1 inhibition on the growth/proliferation of HSCs (mean ± SE; bP < 0.01 and cP < 0.001 compared with the group without TGF-β1; eP < 0.01 for the comparison of the TGF-β1-treated group with the groups subjected to TGF-β1 treatment and different interventions; Student’s t test). GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor-β1; siRNAs: Small interfering RNAs.

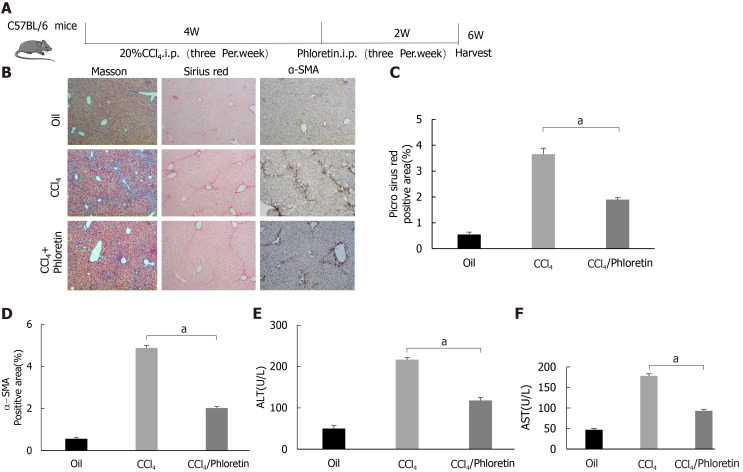

GLUT1 inhibition delays the development of liver fibrosis in a mouse model of liver fibrosis

In vitro experiments confirmed the importance of GLUT1 in liver fibrosis. Next, we examined whether inhibition of GLUT1 expression suppressed liver fibrosis in vivo. Phloretin, a specific inhibitor of GLUT1, was used, and its effect on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis was examined. After successful establishment of the CCl4-induced model, an i.p. injection of phloretin was administered three times a week; the intervention was discontinued after 2 wk. A simple technical roadmap is shown in Figure 6A. Compared with those in the model group, the areas of collagen fiber deposition were significantly reduced in the liver tissues from mice in the drug intervention group; these findings were confirmed by Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red staining (Figure 6B-D). The degree of liver inflammation was determined by performing serological assessments of changes in ALT and AST levels, and the results indicated that the degree of inflammation was significantly reduced in the drug intervention group (Figure 6E and F). Therefore, the in vivo results revealed that GLUT1 inhibition reduces CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.

Figure 6.

Glucose transporter 1 inhibition delays the development of liver fibrosis in a mouse model of liver fibrosis. A: Schematic diagram of the experiment. C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with CCl4 to induce liver fibrosis. The model was successfully established after 4 wk. Among the treatment groups, the CCl4 + phloretin group was intraperitoneally injected with phloretin (10 mg/kg) three times a week, and the CCl4 group was injected with normal saline as a control. The treatments were discontinued after 2 wk; B: Mouse livers were collected, and liver tissue sections were prepared. The sections were subjected to Masson’s trichrome staining, Sirius red staining and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (original magnification, × 10); C: The positive area ratio detected using Sirius red staining; D: The positive area ratio for α-SMA IHC staining; E and F: Serological analysis of ALT (E) and AST (F) levels (n = 5-7; the mean ± SE; scale bar, 100 μm; aP < 0.05 for the comparison between the CCl4 group and the CCl4 + phloretin group; Student’s t test). α-SMA: Alpha-smooth muscle actin.

DISCUSSION

In normal liver tissues, quiescent HSCs express TGF-β1 at low levels, while TGF-β1 is immediately upregulated after acute or chronic liver injury and interacts with multiple signaling pathways to induce HSC activation and proliferation and extensive ECM production[29,30]. TGF-β1 enhances aerobic glycolysis, amino acid uptake and lactic acid production in Ras- and Myc-transformed cells. TGF-β1 contributes to the metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells and tumor-associated stromal cells[31]. When used to replace a peritoneal dialysis solution, TGF-β1 stimulates glycolysis and inhibits mitochondrial respiration of mesothelial cells, thus promoting the development of peritoneal fibrosis[32]. Preliminary yet strong evidence supporting the importance of metabolic reprogramming in the activation of fibroblasts is steadily accumulating. Research on the mechanism of organ fibrosis also shows that TGF-β1 is related to the occurrence of aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial dysfunction. The transdifferentiation of resting HSCs into hepatic fibroblasts has been confirmed to be related to mutual transformation between glycolytic enzymes and gluconeogenic enzymes triggered by Hedgehog signaling[33]. Glycolysis is an important pathway of glucose metabolism, and GLUT1 is the most widely expressed glucose transporter in mammals; its expression is regulated by changes in metabolic status and oxidative stress. GLUT1 is also an important marker of liver carcinogenesis and metabolic liver diseases[34]. GLUT1-dependent glycolysis exacerbates lung fibrogenesis during Streptococcus pneumoniae infection via AIM2 inflammasome activation[35]. In the pathogenesis of diabetic glomerulosclerosis, TGF-β1 triggers GLUT1 activation by stretching glomerular mesangial cells. In breast cancer cells, long-term exposure to TGF-β1 restores GLUT1 expression and results in stable EMT and unlimited cell proliferation[36,37]. Therefore, we questioned whether TGF-β1 and GLUT1 are related to liver fibrosis.

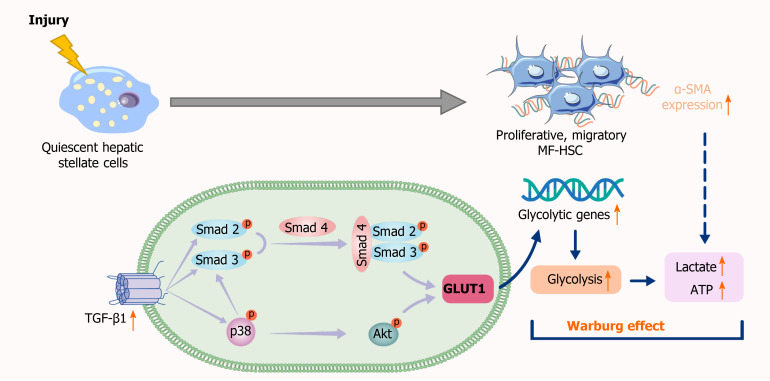

This study showed a significant increase in GLUT1 expression in human and mouse fibrotic liver tissues, which is consistent with the research results of Wan et al[24]. With the increase in TGF-β1 Levels, the gene expression levels of key enzymes, including GLUT1, in the glycolytic pathway are elevated, glucose consumption and intracellular lactate production are also increased, and glycolytic flux by HSCs is enhanced. As expected, the results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies assessing the mechanism of metabolic reprogramming of pulmonary fibrotic fibroblasts[38], indicating that TGF-β1 induces aerobic glycolysis and drives the occurrence of metabolic reprogramming during the process of stromal cell transdifferentiation. Increased GLUT1 expression also contributes to an elevated glycolytic rate, increased lactic acid production and enhanced glucose-dependent metabolic pathways in cells. In contrast, GLUT1 expression decreased significantly after the addition of a TGF-β1 receptor inhibitor, indicating that GLUT1 expression is related to TGF-β1 signaling. Experiments involving Smad overexpression, siRNA-mediated knockout and Smad inhibitors showed that the response of GLUT1 to TGF-β1 was at least partially dependent on the Smad pathway. Studies have identified a cascade of related pathways activated by TGF-β1. Therefore, this study attempted to verify whether non-Smad pathways were also involved in the induction of GLUT1 expression in HSCs. The noncanonical PI3K/AKT and p38 MAPK pathways activated by TGF-β1 were examined. In colorectal cancer (CRC) cells, silencing GLUT1 expression inactivates the TGF-β1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, inhibits the proliferation of CRC cells and promotes apoptosis. MAPK activation by TGF-β1 may trigger GLUT1 synthesis[39,40]. Based on the results of the present study, the simultaneous addition of specific inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT and p38 pathways, i.e., SB203580 and LY294002, respectively, reduced TGF-β1-induced GLUT1 protein expression. The addition of the p38 pathway inhibitor resulted in a decrease in Smad2 protein phosphorylation, changes in the phosphorylated AKT level and changes in the phosphorylation level of a protein downstream of PI3K/AKT signaling (namely, S6); therefore, we speculated that the p38 MAPK pathway acted as a bridge between the TGF-β1-mediated Smad and AKT pathways in HSCs and that reduced activation of the p38 MAPK pathway would inhibit the latter two pathways. In addition, the p38 MAPK pathway might limit Smad pathway-mediated GLUT1 expression to a certain extent. These results are consistent with the previously reported crosstalk between Smad and p38 MAPK in TGF-β1 signal transduction in human glioblastoma cells[41]. However, the specific mechanism underlying the interaction among TGF-β1 pathways in the induction of aerobic glycolysis in stellate cells requires further study. The significant reduction in GLUT1 protein expression was related to the simultaneous inhibition of the Smad3, p38 MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways, indicating that GLUT1 protein expression during stellate cell activation requires the activation and signaling of these three pathways. Moreover, activation of the p38 MAPK pathway might result in a certain synergistic effect with the Smad2/3 pathway (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the mechanisms implicated in canonical and noncanonical transforming growth factor-β pathways regulating glucose transporter 1 expression. TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor-β1; GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1; MF-HSC: Myofibroblasts-hepatic stellate cells; α-SMA: Alpha-smooth muscle actin.

TGF-β1 is a pleiotropic cytokine with an important role in the occurrence of liver fibrosis. According to previous studies, TGF-β1 signaling clearly promotes cell migration, matrix synthesis and HSC differentiation toward myofibroblasts. Moreover, the effect of TGF-β1 on fibroblast migration and proliferation depends on changes in the microenvironment[42]. As shown in the present study, TGF-β1 promoted the proliferative and migratory capabilities of HSCs, functions that are hallmarks of cell transformation. The addition of a pharmacological inhibitor of GLUT1 activity (phloretin, an effective GLUT1 inhibitor capable of inhibiting bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in vivo[43]) and silencing of the GLUT1 gene eliminated TGF-β1-induced proliferation, growth and migration. Finally, a GLUT1 inhibitor was used in in vivo experiments, and the degree of mouse liver fibrosis improved, collagen fiber deposition decreased, and the degree of inflammation decreased. Given the importance of GLUT1, the experimental results revealed that GLUT1 is involved in aerobic glycolysis during HSC activation and that aerobic glycolysis is a response to TGF-β1 signaling mediated by the Smad, PI3K/AKT and p38 MAPK pathways.

CONCLUSION

In summary, TGF-β1-induced GLUT1 expression may be one of the mechanisms involved in the reprogramming of HSCs, providing an expanded basis and new insights for the mechanism of action of TGF-β1 in metabolic reprogramming during liver fibrosis. GLUT1 plays an important role in aerobic glycolysis in HSCs and in promoting cell proliferation and transformation. GLUT1 inhibition may be an alternative therapy to the current traditional treatments for liver fibrosis. However, the extent to which GLUT1 inhibition contributes to elimination of the profibrotic effect of TGF-β1 and the specific molecular mechanisms of the interaction between the two may require verification using approaches combining proteomics and single-cell sequencing, which may be an attractive research direction in the future.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Liver fibrosis is a refractory disease that develops progressively and eventually evolves into liver cirrhosis or even liver cancer. Hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation is the initiating factor for liver fibrosis, while aerobic glycolysis is one of the main metabolic characteristics. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is the most important profibrotic factor in HSCs, and TGF-β1 drives metabolic reprogramming. Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) is the most widely distributed glucose transporter in mammals and is related to glycolytic metabolism. However, the role of GLUT1 in liver fibrosis and the relationship between GLUT1 and TGF-β1 remain unclear and require further investigation.

Research motivation

The results of this study might provide a basis for the application of GLUT1 in the treatment of liver fibrosis and provide an expanded basis for understanding the mechanism of action of TGF-β1 in metabolic reprogramming during liver fibrosis.

Research objectives

This study examined changes in GLUT1 expression in human and mouse fibrotic liver tissues and differences in extracellular acid production and in the expression levels of key glycolytic enzymes and GLUT1 during HSC activation induced by TGF-β1-related pathways. In addition, this study further explored the relationship between TGF-β1 pathways and GLUT1 expression and the potential underlying molecular mechanisms.

Research methods

IHC was employed to examine changes in GLUT1 expression in human and mouse fibrotic liver tissues. Immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine changes in GLUT1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression in mouse fibrotic liver tissue. Primary mouse stellate cells were isolated. After activation of the cells by TGF-β1 stimulation, changes in extracellular acid production, key glycolytic enzymes and glucose consumption were examined. In addition, changes in GLUT1 expression were explored by activating/inhibiting the Smad2/3 pathway and inhibiting the expression of proteins related to the p38 and PI3K/AKT pathways. Finally, in mice with liver fibrosis, the effect of a GLUT1 inhibitor on liver fibrosis was investigated by performing Masson’s trichrome staining and Sirius red staining and analyzing serological inflammatory markers.

Research results

The expression of the GLUT1 protein was increased in both mouse and human fibrotic liver tissue.immunofluorescence staining revealed the colocalization of GLUT1 and α-SMA proteins, indicating that GLUT1 expression was related to the development of liver fibrosis. TGF-β1 induced an increase in aerobic glycolysis in HSCs and induced GLUT1 expression in HSCs by activating the canonical and noncanonical signaling pathways. The p38 MAPK pathway and the Smad pathway synergistically affected the induction of GLUT1 expression. GLUT1 inhibition eliminated the effect of TGF-β1 on the proliferation and migration of HSCs. A GLUT1 inhibitor was administered to a mouse model of liver fibrosis, and GLUT1 inhibition reduced the degree of liver inflammation.

Research conclusions

GLUT1 expression was upregulated in liver fibrosis, and the underlying mechanism was related to activation of the Smad2/3, p38 and PI3K/AKT pathways by TGF-β1, which directly induced GLUT1 expression and promoted glycolysis. GLUT1 inhibition eliminated TGF-β1-induced HSC activation, proliferation and migration, and GLUT1 inhibition exerted an antifibrotic effect.

Research perspectives

The results of this study reveal that the TGF-β1 pathway directly induces GLUT1 expression and aerobic glycolysis, thus promoting liver fibrosis. This study preliminarily clarified the mechanism underlying the interaction between TGF-β1 and GLUT1 in liver fibrosis, thus providing a deeper understanding of the mechanism of liver fibrosis and providing guidance for the selection of targets to treat liver fibrosis. The results from this study indicate that GLUT1 inhibitors may have certain prospective applications as therapeutic drugs for liver fibrosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Ding Q for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University.

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: All animal experiments conformed to the internationally accepted principles for the care and use of laboratory animals (license No. 2000719). All animal interventions were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Guizhou Medical University.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE Guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE Guidelines.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 30, 2021

First decision: July 2, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rojas A, Vela D, Wang Z S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Ming-Yu Zhou, Department of Internal Medicine, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550001, Guizhou Province, China; Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Ming-Liang Cheng, Department of Internal Medicine, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550001, Guizhou Province, China; Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Tao Huang, Department of Internal Medicine, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550001, Guizhou Province, China.

Rui-Han Hu, Department of Internal Medicine, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550001, Guizhou Province, China.

Gao-Liang Zou, Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Hong Li, Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Bao-Fang Zhang, Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Juan-Juan Zhu, Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Yong-Mei Liu, Clinical Laboratory Center, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Yang Liu, Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China.

Xue-Ke Zhao, Department of Internal Medicine, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550001, Guizhou Province, China; Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550004, Guizhou Province, China. zhaoxueke1@163.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ni Y, Li JM, Liu MK, Zhang TT, Wang DP, Zhou WH, Hu LZ, Lv WL. Pathological process of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7666–7677. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i43.7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higashi T, Friedman SL, Hoshida Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Vallée JN. Thermodynamic Aspects and Reprogramming Cellular Energy Metabolism during the Fibrosis Process. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18122537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Choi SS, Michelotti GA, Chan IS, Swiderska-Syn M, Karaca GF, Xie G, Moylan CA, Garibaldi F, Premont R, Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA, Diehl AM. Hedgehog controls hepatic stellate cell fate by regulating metabolism. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1319–1329.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson NC, Rieder F, Wynn TA. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature. 2020;587:555–566. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2938-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syed V. TGF-β Signaling in Cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:1279–1287. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang YE. Non-Smad Signaling Pathways of the TGF-β Family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derynck R, Budi EH. Specificity, versatility, and control of TGF-β family signaling. Sci Signal. 2019;12 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aav5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Signaling Receptors for TGF-β Family Members. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Wieser R, Ventura F, Massagué J. Mechanism of activation of the TGF-beta receptor. Nature. 1994;370:341–347. doi: 10.1038/370341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J. 1998;17:3091–3100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dewidar B, Meyer C, Dooley S, Meindl-Beinker AN. TGF-β in Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrogenesis-Updated 2019. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8111419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao X, Kwan JYY, Yip K, Liu PP, Liu FF. Targeting metabolic dysregulation for fibrosis therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:57–75. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soukupova J, Malfettone A, Bertran E, Hernández-Alvarez MI, Peñuelas-Haro I, Dituri F, Giannelli G, Zorzano A, Fabregat I. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Induced by TGF-β in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Reprograms Lipid Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22115543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kottmann RM, Kulkarni AA, Smolnycki KA, Lyda E, Dahanayake T, Salibi R, Honnons S, Jones C, Isern NG, Hu JZ, Nathan SD, Grant G, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. Lactic acid is elevated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and induces myofibroblast differentiation via pH-dependent activation of transforming growth factor-β. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:740–751. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0084OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LQ, Cheung LS, Feng L, Tanner W, Frommer WB. Transport of sugars. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:865–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-033904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Pavlou S, Du X, Bhuckory M, Xu H, Chen M. Glucose transporter 1 critically controls microglial activation through facilitating glycolysis. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14:2. doi: 10.1186/s13024-019-0305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hua W, Ten Dijke P, Kostidis S, Giera M, Hornsveld M. TGFβ-induced metabolic reprogramming during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:2103–2123. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03398-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu M, Quek LE, Sultani G, Turner N. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induction is associated with augmented glucose uptake and lactate production in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Metab. 2016;4:19. doi: 10.1186/s40170-016-0160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W, Wei Z, Liu Y, Li H, Ren R, Tang Y. Increased 18F-FDG uptake and expression of Glut1 in the EMT transformed breast cancer cells induced by TGF-beta. Neoplasma. 2010;57:234–240. doi: 10.4149/neo_2010_03_234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoki K, Haneda M, Maeda S, Koya D, Kikkawa R. TGF-beta 1 stimulates glucose uptake by enhancing GLUT1 expression in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1704–1712. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wan L, Xia T, Du Y, Liu J, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Guan F, Wu J, Wang X, Shi C. Exosomes from activated hepatic stellate cells contain GLUT1 and PKM2: a role for exosomes in metabolic switch of liver nonparenchymal cells. FASEB J. 2019;33:8530–8542. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802675R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao XK, Yu L, Cheng ML, Che P, Lu YY, Zhang Q, Mu M, Li H, Zhu LL, Zhu JJ, Hu M, Li P, Liang YD, Luo XH, Cheng YJ, Xu ZX, Ding Q. Focal Adhesion Kinase Regulates Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4032. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou GL, Zuo S, Lu S, Hu RH, Lu YY, Yang J, Deng KS, Wu YT, Mu M, Zhu JJ, Zeng JZ, Zhang BF, Wu X, Zhao XK, Li HY. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 represses hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis via regulation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4222–4234. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i30.4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K. TGF-β and the TGF-β Family: Context-Dependent Roles in Cell and Tissue Physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu F, Liu C, Zhou D, Zhang L. TGF-β/SMAD Pathway and Its Regulation in Hepatic Fibrosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2016;64:157–167. doi: 10.1369/0022155415627681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simeone DM, Zhang L, Graziano K, Nicke B, Pham T, Schaefer C, Logsdon CD. Smad4 mediates activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by TGF-beta in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C311–C319. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan W, Liu T, Chen W, Hammad S, Longerich T, Hausser I, Fu Y, Li N, He Y, Liu C, Zhang Y, Lian Q, Zhao X, Yan C, Li L, Yi C, Ling Z, Ma L, Xu H, Wang P, Cong M, You H, Liu Z, Wang Y, Chen J, Li D, Hui L, Dooley S, Hou J, Jia J, Sun B. ECM1 Prevents Activation of Transforming Growth Factor β, Hepatic Stellate Cells, and Fibrogenesis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1352–1367.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson N, Piek E, Sundström M, ten Dijke P, Nilsson G. Transforming growth factor-beta-mediated mast cell migration depends on mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Cell Signal. 2001;13:483–490. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Si M, Wang Q, Li Y, Lin H, Luo D, Zhao W, Dou X, Liu J, Zhang H, Huang Y, Lou T, Hu Z, Peng H. Inhibition of hyperglycolysis in mesothelial cells prevents peritoneal fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nigdelioglu R, Hamanaka RB, Meliton AY, O'Leary E, Witt LJ, Cho T, Sun K, Bonham C, Wu D, Woods PS, Husain AN, Wolfgeher D, Dulin NO, Chandel NS, Mutlu GM. Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β Promotes de Novo Serine Synthesis for Collagen Production. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:27239–27251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho SJ, Moon JS, Nikahira K, Yun HS, Harris R, Hong KS, Huang H, Choi AMK, Stout-Delgado H. GLUT1-dependent glycolysis regulates exacerbation of fibrosis via AIM2 inflammasome activation. Thorax. 2020;75:227–236. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chadt A, Al-Hasani H. Glucose transporters in adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle in metabolic health and disease. Pflugers Arch. 2020;472:1273–1298. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang L, Deberardinis R, Boothman DA. The cancer cell 'energy grid': TGF-β1 signaling coordinates metabolism for migration. Mol Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e981994. doi: 10.4161/23723556.2014.981994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilchian A, Giotopoulou N, Sun W, Fuxe J. Different Regulation of Glut1 Expression and Glucose Uptake during the Induction and Chronic Stages of TGFβ1-Induced EMT in Breast Cancer Cells. Biomolecules. 2020;10 doi: 10.3390/biom10121621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie N, Tan Z, Banerjee S, Cui H, Ge J, Liu RM, Bernard K, Thannickal VJ, Liu G. Glycolytic Reprogramming in Myofibroblast Differentiation and Lung Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:1462–1474. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0780OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujishiro M, Gotoh Y, Katagiri H, Sakoda H, Ogihara T, Anai M, Onishi Y, Ono H, Funaki M, Inukai K, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. MKK6/3 and p38 MAPK pathway activation is not necessary for insulin-induced glucose uptake but regulates glucose transporter expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19800–19806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Koh M, Suga J, Masuzaki H, Ogawa Y, Hosoda K, Nishimura H, Watanabe Y, Inoue G, Nakao K. Constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase increases GLUT1 expression and recruits both GLUT1 and GLUT4 at the cell surface in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2000;49:332–339. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dziembowska M, Danilkiewicz M, Wesolowska A, Zupanska A, Chouaib S, Kaminska B. Cross-talk between Smad and p38 MAPK signalling in transforming growth factor beta signal transduction in human glioblastoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:1101–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Y, Jiang F, Zheng X, Katakowski M, Buller B, To SS, Chopp M. TGF-β1 promotes motility and invasiveness of glioma cells through activation of ADAM17. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1329–1335. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho SJ, Moon JS, Lee CM, Choi AM, Stout-Delgado HW. Glucose Transporter 1-Dependent Glycolysis Is Increased during Aging-Related Lung Fibrosis, and Phloretin Inhibits Lung Fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56:521–531. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0225OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.