Abstract

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that leads to the destruction of both soft and hard periodontal tissues. Complete periodontal regeneration in clinics using the currently available treatment approaches is still a challenge. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have shown promising potential to regenerate periodontal tissue in various preclinical and clinical studies. The poor survival rate of MSCs during in vivo transplantation and host immunogenic reaction towards MSCs are the main drawbacks of direct use of MSCs in periodontal tissue regeneration. Autologous MSCs have limited sources and possess patient morbidity during harvesting. Direct use of allogenic MSCs could induce host immune reaction. Therefore, the MSC-based indirect treatment approach could be beneficial for periodontal regeneration in clinics. MSC culture conditioned medium (CM) contains secretomes that had shown immunomodulatory and tissue regenerative potential in pre-clinical and clinical studies. MSC-CM contains a cocktail of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, and exosomes, extracellular vesicles, etc. MSC-CM-based indirect treatment has the potential to eliminate the drawbacks of direct use of MSCs for periodontal tissue regeneration. MSC-CM holds the tremendous potential of bench-to-bed translation in periodontal regeneration applications. This review focuses on the accumulating evidence indicating the therapeutic potential of the MSC-CM in periodontal regeneration-related pre-clinical and clinical studies. Recent advances on MSC-CM-based periodontal regeneration, existing challenges, and prospects are well summarized as guidance to improve the effectiveness of MSC-CM on periodontal regeneration in clinics.

Keywords: Periodontal tissue regeneration, Mesenchymal stem cells conditioned medium, Osteogenesis, Immunomodulation, Angiogenesis, Chemotaxis

Background

Periodontitis is a complicated chronic inflammatory oral disease, which is globally prevalent and has direct involvement of vast oral microbiome, oral tissues and immune cells [1, 2]. Periodontitis could cause irreversible destruction of periodontal tissues, including periodontal ligament (PDL), cementum, and alveolar bone [3]. Disrupted microbial homeostasis in oral cavity may increase the risk of occurrence of various systemic diseases, including colitis, myocardial infraction, and Alzheimer’s diseases [4–9]. Therefore, the effective treatment of periodontitis and periodontal regeneration is crucial for human health.

Periodontal tissue regeneration involves the regeneration of the gingiva, alveolar bone, PDL and cementum. Among them, the regeneration and natural alignment of PDL is so far one of the most challenging tasks in the field of tissue engineering [10]. To regenerate lost periodontal tissue, numerous procedures and products have been developed such as guided tissue regeneration (GTR), application of platelet-rich plasma, natural graft tissues and synthetic biomaterials [11–16]. However, most of the current or emerging paradigms have either proven to have limited and variable outcomes or have not been developed for clinical use [17].

Stem cell-based periodontal regeneration is currently at the center of attention [18]. Different cell types such as bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs), periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), dental pulp stem cells (DPSC) are key stem cells used in stem cell-based periodontal regeneration [19]. However, stem cell-based therapies have some serious limitations, including dedifferentiation during MSCs amplification, reduction of regeneration efficiency after administration, inconsistent quality control in large-scale cell production, and the invasive procedure of MSCs isolation [20–24]. In addition, it has been reported that in vivo monitoring of transplanted MSCs in an acute myocardial infarction tracked only 4.4% of MSCs in the transplanted site after 1 week, which indicated the poor survival rate of transplanted MSCs. Interestingly, the MSCs grafting promotes the functional improvement of the infarcted heart suggesting the role of MSCs released trophic factors on native cardiac and vascular cells’ function [25]. This suggests the role of stem cell-released signaling molecules and factors on tissue regeneration.

Shreds of evidence suggest that MSCs enhance immune responses during early-stage inflammation through the paracrine and autocrine manners, and subsequent tissue regeneration by producing a spectrum of protective bioactive factors [26, 27]. The factors are broadly defined as secretome or conditioned medium (CM), and usually classified as cytokines, chemokines, cell adhesion molecules, lipid mediators, interleukins, growth factors, hormones, exosomes, microvesicles, etc. [28]. The CM from stem cells can play a major role in tissue repair and regeneration [29]. As a cell-free technique, MSC-CM transplantation is more convenient and safer to apply and has greater potential for clinical translation than direct MSCs transplantation [30, 31]. MSC-CM provides several key advantages over cell-based applications: (a) MSC-CM employs the administration of proteins instead of whole cells that avoids the risk of host immune reactions; (b) MSC-CM can be stored for a relatively long period without any toxic cryopreservatives such as DMSO; (c) MSC-CM is cost-effective; (d) Evaluation of CM for safety and efficacy is much simpler compared to conventional pharmaceutical agents or MSCs [32]. Moreover, MSC-CM has immunomodulatory and tissue regenerative potential [33, 34]. Therefore, the use of MSC-CM could be an effective approach to regenerate periodontal tissue in the inflammatory environment of periodontitis. The therapeutic use of MSC-CM in periodontal regeneration is still a new frontier. The present review discusses the current understanding of the use of CM for periodontal tissues regeneration in preclinical and clinical studies, existing challenges, and prospects.

Periodontal tissue regeneration

Periodontitis results from oral microbial dysbiosis, which disrupts the ecologically balanced biofilm associated with periodontal tissue homeostasis and finally causes destruction of the tooth-attachment apparatus, including gingiva, alveolar bone, root cementum, and PDL [6]. The dysbiotic microbes induce host immune response recruiting mucosal epithelial cells and gingival fibroblasts, and immune cells such as mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs), antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and specific T cell subsets (type 17 helper T cells, Th17 cells) in the periodontal region. The interaction between dysbiotic microbes and the host cells leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines [35]. The main components of these cytokines are interleukin-1 (IL-1) [36], IL-6 [37], and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family [38]. These are key pro-inflammatory cytokines that promote tissue destruction. Secondly, cytokines secreted by MNPs, APCs, and local lymphocytes lead to the differentiation of a specific subset of inflammatory lymphocytes. The stimulation of IL-1 and IL-6 family cytokines induces osteoclast formation and activity in the bony niche [35].

The true regeneration of periodontium includes alveolar bone, PDL, and cementum, which is characterized by newly formed alveolar bone and cementum connected by regenerated periodontal ligament fibers aligned in certain direction [10]. It has been reported that the regeneration of periodontium may occur simultaneously, although the osteogenic process may be slightly prior to the differentiation of cementum and fibers [39]. Therefore, the structural and interactive complexity of periodontal tissue is the key challenge for effective and functional regeneration.

The purpose of periodontal therapy is to control the infection and reconstruct the structure and function of periodontal tissues. The effectiveness of traditional treatments in periodontal tissue regeneration is still limited and unpredictable [10]. Tissue engineering is a new cutting-edge technology which involves stem cells, cytokines, and scaffolds. In recent years, the application of tissue engineering in periodontal tissue regeneration is increasing [7, 16, 19], the regeneration of alveolar bone [40–43], PDL [44–46], cementum [47, 48] and even the entire bone-PDL-cementum complex [39] has gained success to some extent.

Sources of MSCs

Stem cells are at the forefront of new therapies because of their ability to self-renew and differentiate towards various cell lineages [49]. Stem cells are mainly composed of embryonic stem cells and somatic stem cells. Somatic stem cells include both hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and MSCs [50]. Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy have proposed the minimal criteria to define human MSCs. [1] MSCs are plastic-adherent when maintained in standard culture conditions. [2] MSCs express CD105, CD73 and CD90, and lack expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79a or CD19 and HLA-DR surface molecules. [3] MSCs have osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic plasticity in vitro [51, 52]. A variety of studies have demonstrated that MSCs have great potential in bone and dental tissue regeneration. The most commonly used stem cells are BMSCs [53], periosteal stem cells (PSCs) [54], adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) [55], and dental tissue-derived stem cells (DSCs) [56], which include PDLSCs [57], dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) [58], gingival fibroblastic stem cells (GFSCs) [59], dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs) [60], stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs) [61], and stem cells from the apical papilla (SCAP) [62] (Fig. 1). In addition, the tissues harvested during dental implant are also an important source of DSCs [63, 64].

Fig. 1.

Sources of mesenchymal stem cells that are commonly used for tissue regeneration applications

MSCs from different sources display tissue reparative potential [65, 66]. MSCs have garnered significant interest in tissue engineering due to their immunomodulatory capacity [67]. MSCs express low-level MHC class II molecules and no co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 required for effector T cell induction to ensure allogeneic application [68]. The research related to the application of MSCs in bone and tooth regeneration is currently a hot topic in the field of tissue engineering [63, 69].

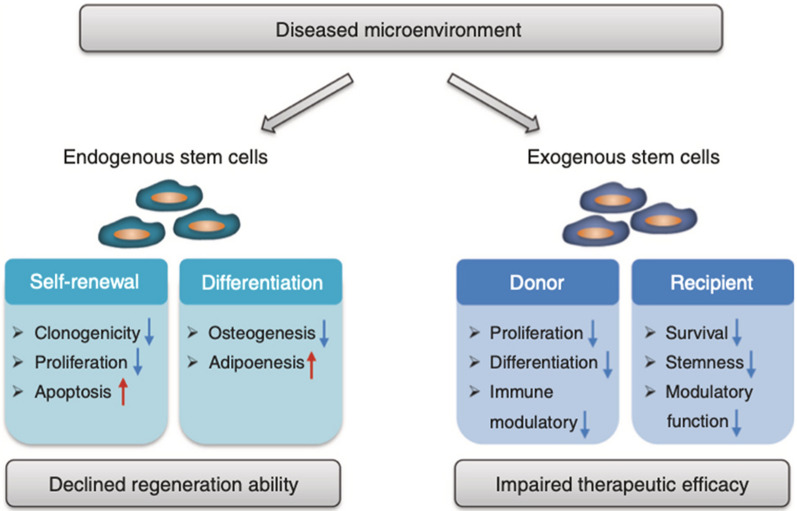

For exogenous stem cells therapies, various techniques have been developed to achieve periodontal tooth-supportive tissue regeneration. Two review articles by Park CH et al. and Xu et al. had well summarized recent advances on exogenous stem cell-based therapies for periodontal tissue regeneration [19, 70]. However, exogenous stem therapy requires a large number of cells and high technical expertise, which increases the cost of treatment. In addition, there are some risk factors in the use of stem cell therapy, such as immune reaction, disease transmission, stem cells survival, cancer risk, etc. More detail on stem cell-treatment-associated risk factors could be found in a review article by Herberts et al. [71]. Nevertheless, the efficacy of stem cell therapy is not always fulfilled according to the microenvironment. The efficacy of transplanted exogenous stem cells is compromised by diseased microenvironment of the donors and the recipients (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the self-renewal and differentiation ability of endogenous stem cells are reduced in the diseased microenvironment that leads to compromised tissue regeneration [63, 72, 73]. Therefore, use of stem cell-CM could be a better alternative to direct use stem cells for periodontal regeneration that gives similar results to stem cells but eliminate the risks associated with the direct use of stem cells.

Fig. 2.

Microenvironment affects the stem cell-based tissue regeneration. The diseased microenvironment impairs functions of endogenous and exogenous stem cells leading to declined self-renewal ability and disturbed differentiation potential [63] Reprinted with permission. Copyright (2019), Springer Nature

Conditioned medium from MSCs (MSC-CM) as cell-free therapeutic strategy

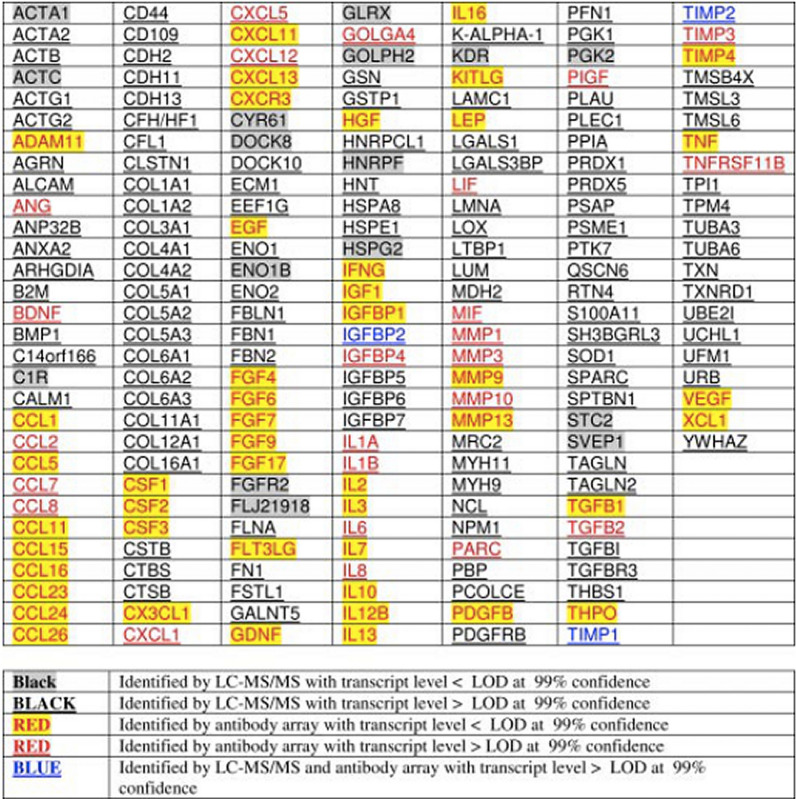

The function of MSCs appears not to be mediated through engraftment in the injured tissues but a ‘hit and run’ mechanism, which indicated that MSCs mainly act through the bio-active factors [25, 74]. The MSC-CM is a cocktail mixture of several hundred to thousands of different proteins, cytokines, growth factors, and enzymes. MSC-CM also contains extracellular vesicles (EVs) as a cargo of various proteins, coding and non-coding RNA, small RNAs, autophagosomes, mitophagosomes. EVs could be subdivided into apoptotic bodies, microparticles and exosomes [28]. Cytokine antibody array analysis revealed 201 unique gene products in human embryonic stem cell-derived MSC-CM (hESC-MSC-CM) (Fig. 3). These growth factors significantly drive the biological processes of metabolism, defense response, and tissue regeneration [75]. Shreds of literature had reported the concentration of different cytokines and growth factors in different MSC-derived CM. Some researchers have even proposed the possible role of certain growth factors or cytokines present in MSC-CM in tissue regeneration [24, 28, 75]. However, it is very difficult to claim the role of only a few growth factors or cytokines present in MSC-CM on tissue regeneration. All these cellular and biological products might play a role to give the cumulative results of tissue regeneration. Compared to cell-based therapies, CM may provide several advantages: (1) CM uses proteins rather than the whole cells to promote regeneration; (2) CM could be stored for a long time without using any toxic reagent such as DMSO; (3) The preparation of CM is more economical and CM can be mass produced; (4) The safety and efficacy evaluation of CM will be simpler, similar to traditional pharmaceutical preparations [28, 76].

Fig. 3.

Unique gene products of MSC-CM identified by LC–MS/MS and antibody array [75] Reprinted with permission. Copyright (2007), American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

CM from different MSCs for periodontal tissue regeneration

CM from different sources of MSCs has been identified to have beneficial effects on the recipient, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-scarring, and immunomodulatory [77]. In recent years, MSC-CM has been widely used in the field of tissue regeneration [78–80], and its application in periodontal tissue regeneration is also gradually increasing [81, 82]. Osteogenesis, angiogenesis, cementogenesis, periodontal ligament regeneration and inflammation alleviation are key events to address during periodontal tissue engineering. Reports from literature had unraveled the various biological activities of MSC-CM, including, osteoinductive, angioinductive, chemotactic, immunomodulatory, and cell growth and differentiation (Fig. 4). These entire biological activities of MSC-CM could facilitate the periodontal tissue regeneration.

Fig. 4.

Biological activities of MSC-CM that could facilitate periodontal regeneration

MSC-CM-based periodontal tissue regeneration

MSC-CM could promote the regeneration of periodontal tissues. It has been reported that after transplantation of MSC-CM for 4 weeks, periodontal ligament like structures were seen between regenerated cementum-like structure and bone [82]. PDLSC-CM contains various growth factors, cytokines, extracellular matrix proteins, and angiogenic factors. Study has shown that PDLSC-CM promoted periodontal regeneration in a concentration-dependent manner [83]. 4 weeks after CM transplantation, histological images showed higher bone levels and newly formed periodontal tissues were observed in PDLSC-moderate and PDLSC-high groups compared with other groups. Collagen bundles, which bridged tooth root and alveolar bone, were evident in periodontal space of all sections. Periodontal ligament and gingiva are both important sources of stem cells. Gingiva is more accessible than periodontal ligament. PDLSC-CM and GMSC-CM had demonstrated a significant effect on periodontal regeneration by alleviating TNF-α and IL-1β expression and inducing BSP-II and Runx2 expression. Moreover, IL-10 expression was significantly higher in the GMSC-CM group than in the PDLSC-CM group and the control groups [84]. PDLSCs and GMSCs co‐cultured with APTG‐CM could form cementum and PDL‐like structures [85]. The exosomes of ASCs has been reported to be used as adjunctive therapy to nonsurgical periodontal treatment, and organized proliferating periodontal ligament tissue could be seen in interdental periodontal ligament space [86]. It has been reported that CM from osteogenically induced human maxilla BMSCs for 15 days promoted osteogenesis of hPDLSCs, and produced cementum-like mineralized and PDL-like collagen fibers [87].

Apical tooth germ cell-CM (APTG-CM) had been reported to promote cementogenic differentiation of PDLSCs [48]. Another study has shown that dental follicle cell-CM could induce cementogenic differentiation of rat ASCs, in which Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway played a key role [88]. Odontoblast-CM has been reported to promote cementogenesis, which indicated the secreted products of odontoblasts could induce cementoblast differentiation [89]. Endogenous factors secreted by ASCs promote cementogenic differentiation of hPDLSCs [90]. MSC-CM had shown robust regeneration potential of alveolar bone and cementum in dog [91], indicating the possible application of MSC-CM on cementum regeneration.

Periodontal tissue regenerative potential of MSC-CM is mainly mediated by the cooperative effects of the cocktail of cytokines, growth factors, and enzymes such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) [92, 93], etc. Recent advances in MSC-CM-derived EVs including exosome-based periodontal tissue regeneration are well-reviewed in literature [94, 95]. Sakaguchi et al. prepared the cytokine cocktail (CC) by mixing insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) to mimic MSC-CM secretomes. After 8 weeks, the regenerative periodontal tissues showed greater osteogenesis and cementogenesis by CC than enamel matrix derivative (EMD) [81]. IGFBP6 present in ASCs-CM had been reported to promote periodontal regeneration [90].

The possible mechanism for MSC-CM-based periodontal tissue regeneration

MSC-CM-based angiogenesis

Studies have shown that the process of bone formation and tooth regeneration is coupled to angiogenesis [96, 97]. Osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling are crucial for bone regeneration [98, 99]. Type H vessels are specific types of blood vessels that promote osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling and bone regeneration [100]. MSC-CM is effective in the early phase of bone regeneration and angiogenesis in rabbit maxillary synovial floor elevation [101]. This study suggests that early vascularization facilitates the proliferation and migration of osteoprogenitor cells. MSC-CM increases angiogenesis via promoting migration and proliferation of endothelial cells [102]. VEGF [103] and FGF-2[104] in MSC-CM are proposed to be the main signaling factors that induce bone regeneration by promoting angiogenesis. However, the ability to promote angiogenesis could be relative to the type of stem cells. The proangiogenic potential of BMSC-CM is higher than DPSC-CM or even BMSC-derived EVs [97]. hBMSC-CM had been reported to promote matrigel tube formation and migration of human-derived lymphatic endothelial cells (HDLECs) [105]. Abundant numbers of literature had reported the angiogenic potential of MSC-CM [103, 106, 107]. The role of MSC-CM on type H vessel formation during bone regeneration has not been investigated yet. Future studies focusing on the role of MSC-CM in type H vessel formation are strongly recommended to further elucidate the mechanism of MSC-CM mediated osteogenesis-angiogenesis coupling and periodontal bone regeneration.

MSC-CM-based immunomodulation

Immune cells, including T cells, B cells, macrophages, and neutrophils play a vital role in the pathophysiology of periodontitis. Regulation of immune cells’ function to obtain the favorable immunomodulatory conditions for periodontal tissue regeneration is a challenging task. The immunomodulatory potential of MSC-CM can be utilized for periodontal tissue regeneration in clinics. MSC-CM had been reported to treat colitis by upregulating TGF-β, IL-10 and percentage of Treg cells, and downregulating IL-17 [108]. MSC-CM inhibits M0 macrophage apoptosis and induces M1 macrophage apoptosis. However, MSC-CM had no significant effect on macrophage proliferation and the expression of TNF-α and IL-10 [109]. M2 macrophages had anti-inflammatory properties that induce bone regeneration via the release of IL4, IL-10, and TGF- β). MSC-CM induces macrophage M2 polarization via NF-κB and STAT3 pathways [110]. Similarly, PDLSC-CM had shown M2 macrophage polarization potential by downregulating TNF-α and upregulating IL-10, Arg-1, and CD163 [111].

MSC-CM had been reported to induce neutrophil apoptosis in inflammatory conditions [112]. Human ASC-CM had shown potential to suppress inflammatory bone loss in the LPS-induced murine model [113]. MSC-CM increases the percentage of regulatory T (Treg) cells. Increased number of Treg cells alleviate periodontitis and induce periodontal bone regeneration [114]. MSCs cultured in hypoxic condition or in presence of anti-inflammatory agents such as IL-4 or IL-10 has shown better immunomodulatory properties [115, 116]. Therefore, MSC-CM obtained from optimized in vitro culture of MSC with improved immunomodulatory potential could be beneficial for periodontal tissue regeneration.

MSC-CM-based chemotaxis

The cytokines and growth factors in CM also play a key role in the chemotaxis of endogenous precursor cells. Chemotaxis of osteogenic and angiogenic precursor cells is essential for effective periodontal regeneration. It has been reported that MSC-CM could stimulate migration and proliferation of dog PDLSCs, which may enhance periodontal tissue regeneration [91]. MSC-CM could also promote the migration of endothelial cells and angiogenic differentiation [102, 117]. MSC-derived plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and tenascin-C significantly increase dermal fibroblast (DF) migration in vitro and improved wound healing in vivo by shortening the time for wound closure [118]. On the other hand, MSC-CM promotes macrophage chemotaxis via CCL2-CCR2 interaction [119]. MSC-CM induces higher chemotaxis of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) compared to VEGF-C and bFGF exogenous recombinant proteins [120].

MSCs could be harvested from different origins, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental tissues, and umbilical cord. CM from different MSC sources have different effects on cells migration. BMSCs expresse highest mRNA levels of SDF1 and VCAM-1, and TNF-α. Priming of ASCs gained a significant increase in IDO1 and CCL5. And HUCMSCs release higher protein levels of IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, ICAM1, HGF, MMP1 and CH3L1 [121]. MSC-CM (EVs-depleted) has higher chemotactic potential compared to MSC-EVs [97]. Therefore, the MSC-CM could be beneficial for endogenous precursor cells’ recruitment in the defect site during periodontal regeneration. The in vitro and in vivo effects of MSC-CM on bone regeneration, cementogenesis, angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and chemotaxis reported in literature are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Periodontal regeneration-related in vitro biological activities of MSC-CM

| S. No. | Source of MSC-CM | Cell type | Biological activity | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone regeneration | ||||

| 1 | hASCs | hPDLSCs | Upregulates osteoblastic gene expression in hPDLSCs | [90] |

| 2 | hBMSCs | hPDLSCs | Triggers osteogenesis of hPDLSCs | [87] |

| 3 | Healthy or inflamed PDLSCs | ‘Inflamed’ PDLSCs | Healthy PDLSCs-CM rescues impaired-differentiation of inflamed-PDLSCs | [122] |

| Cementum regeneration | ||||

| 1 | hMSCs | Dog MSCs and dog PDLSCs | Promotes dog MSCs and dog PDLSCs proliferation and migration | [91] |

| 2 | rAPTGs | hGMSCs | Promotes differentiation of hGMSCs along the cementoblastic lineage | [85] |

| 3 | rDFCs | ASCs | Promotes ASCs towards cementoblast-like cells | [88] |

| 4 | rAPTGs | hPDLSCs | Promotes hPDLSCs towards cementoblast-like cells | [123] |

| Angiogenesis | ||||

| 1 | hMSCs | rMSCs | Increases angiogenesis | [82] |

| 2 | hMSCs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) | Promotes angiogenesis and migration of HUVECs | [103] |

| 3 | equine-PB-MSCs | ECs | Induces angiogenesis in equine vascular ECs | [106] |

| 4 | mMSCs and hEPCs | HUVECs | Promotes cell adhesion and proliferation | [107] |

| Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory | ||||

| 1 | hPDLSCs | RAW 264.7 | Inhibits TNF-α expression | [83] |

| 2 | rPDLSCs | rBMDMs | Induces macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype | [111] |

| 3 | hPDLSCs | THP-1 | Induces M1 macrophage polarization | [124] |

| Chemotaxis | ||||

| 1 | hMSCs | Dog BMSCs and dog PDLSCs | Enhances migration and proliferation of dMSCs and dPDLCs | [91] |

| 2 | hBMSCs | HUVECs | Promotes functional angiogenic effects | [97] |

| 3 | hMSCs and canine MSCs | ECs | Increases EC migration, proliferation and the formation of tubule-like structures | [102] |

| 4 | mMSCs | Dermal fibroblast | Induces dermal fibroblast migration | [118] |

| 5 | mMSCs | RAW264.7 | Enhances the chemotaxis of RAW264 cells | [119] |

| 6 | hMSCs | Human dermal lymphatic ECs | Stimulates proliferation, migration, and tube formation of lymphatic ECs | [120] |

Table 2.

Summary of in vivo results showing the periodontal tissue regenerative potential of MSC-CM

| Source of CM | Factors in CM | Study model | Route of delivery | Dose | Duration | Outcomes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPDLSCs | Matrix proteins, enzymes, growth factors, cytokines, and angiogenic factors | Rat periodontal defect | Fibrin coated collagen sponge | 10 br | 4 weeks | Enhances periodontal regeneration | [83] |

| hPDLSCs and hGMSCs | – | Rat periodontal defect | Collagen scaffolds | 1, 2, and 4 weeks | Promotes periodontal regeneration | [84] | |

| hMSCs | IGF-1, VEGF, TGF-1, and HGF | Rat periodontal defect | Collagen sponge | 30 ll | 2 and 4 weeks | Enhances periodontal regeneration via promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis | [82] |

| hBMSCs | – | Ectopic transplantation in immunocompromised mice | Dentin block wrapped with hBMSC-CM-treated hPDLSC cell sheet | – | 8 weeks | Promotes regeneration of cementum and PDL-like structure | [87] |

| rAPTGs | – | Ectopic transplantation in immunocompromised mice | PDLSCs (induced by APTG-CM) + CBB | – | 6 weeks | Induces development of cementum and PDL-like structure | [48] |

| rAPTGs | – | Ectopic transplantation in immunocompromised mice | Cell sheet + dentin + CBB | – | 8 weeks | Induces development of cementum and PDL-like structure | [85] |

| dMSCs | IGF-1, VEGF, TGF-β1, and HGF | Critical-size one-wall intrabony mandibular defects in dog | Atelo-collagen sponge | 300 μL | 4 weeks | Promotes alveolar bone and cementum regeneration | [91] |

| Cytokine cocktail-mimicking MSC-CM secretomes | IGF-1, VEGF-A, TGF-β1 | Class II bifurcation premolar defect in dog | Hydroxypropyl cellulose | 100 μL | 8 weeks | Induces osteogenesis and cementogenesis | [81] |

| hMSCs | IGF-1, VEGF, TGF-β1, and HGF | Partially edentulous patients | MSC-CM + PLGA/β-TCP or MSC-C + ACS | 3 mL | 6 months | Promotes early bone formation and reduces inflammatory cell infiltration | [92] |

| hMSCs | IGF-1 VEGF TGF-b1 | Rabbit bilateral maxillary sinus floor elevation model | β-TCP + MSC-CM | – | 2, 4, 8 weeks | Promotes vascularization and early bone regeneration | [101] |

Summary and prospects

Recent studies have shown that stem cells are effective in tissue mainly via the paracrine effect [125]. The secreted molecules of stem cells play a key role in influencing the cross-talk communications between the cells and the surrounding tissues [29]. In this review, we summarized the regeneration of periodontal tissue by CM from different MSC sources, including BMSCs, PDLSCs, GMDCs, APTGs, DFGs, ADMPCs, ASCs, osteoblast, etc. Previous studies revealed that MSC-CM contains several cytokines, such as IGF-1, VEGF, TGF-β1, and HGF [82, 91, 126, 127]. These cytokines have been proved to regulate angiogenesis, cell migration, proliferation, and osteoblast differentiation to achieve the regeneration of periodontal tissue [127].

Although the applications of MSC-CM on periodontal regeneration have been proved useful in animal models from pre-clinical studies, much work needs to be done to apply it to clinics. The content of MSC-CM varies from cell type to culture condition and batch. It is impossible to get the MSC-CM containing similar secretomes in each treatment in clinics. Therefore MSC-CM cannot guarantee a similar effect in every treatment. The regenerative effect of MSC-CM is usually from the cumulative effect of a cocktail of cytokines and growth factors rather than a few factors present in elevated levels. Not having the worldwide consensus protocol for MSC-CM harvesting for tissue regeneration application is also one problem. So far, there is no data to illustrate that CM from which specific MSC origin is suitable for the specific tissue regeneration. This makes it difficult to choose the proper MSC origin for MSC-CM-based periodontal regeneration. Limited source and invasive procedures to harvest MSCs are key challenges of the use of autologous or allogenic MSC-CM for periodontal regeneration. CM from cell-sheet and co-culture of different cell types such as MSCs, ECs, monocytes, etc. could be more effective for periodontal regeneration compared to 2D expanded MSC-CM. Further in vitro, preclinical, and clinical studies are indispensable to improve the clinical efficacy of MSC-CM-based periodontal tissue regeneration.

Conclusion

The role of stem cells in promoting tissue regeneration mainly depends on their paracrine function. The use of MSC-CM is safer and effective for periodontal tissue regeneration compared to MSC transplantation. The MSC-CM can be tailored as required using different drugs or culture conditions during in vitro culture of MSC. Moreover, the concentration of effective components and growth factors in MSC-CM can be optimized as required. MSC-CM-based periodontal tissue regeneration has the potential to eliminate the use of autologous and allogeneic stem cells. Based on the aforementioned facts, MSC-CM-based periodontal tissue regeneration has tremendous potential for bench-to-bed translation.

Abbreviations

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- CM

Conditioned medium

- BOP

Bleeding on probing

- PDLSCs

Periodontal ligament stem cells

- DPSCs

Dental pulp stem cells

- BMSCs

Bone marrow MSCs

- MNPs

Mononuclear phagocytes

- APCs

Antigen-presenting cells

- PDL

Periodontal ligaments

- AB

Alveolar bone

- HSCs

Hematopoietic stem cells

- PSCs

Periosteal stem cells

- ASCs

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- DSCs

Dental tissue-derived stem cells

- GFSCs

Gingival fibroblastic stem cells

- DFSCs

Dental follicle stem cells

- SHEDs

Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth

- SCAP

Stem cells from the apical papilla

- EVs

Extracellular vesicles

- APTG

Apical tooth germ cell-CM

- HDLECs

Human-derived lymphatic endothelial cells

- DF

Dermal fibroblast

- LEC

Lymphatic endothelial cells

- HUVECs

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Authors’ contributions

HL conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. YS and LW revised the manuscript. HC, XZ, ZC, PZ, YT, YW and TD search for relevant literatures and provided the comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFE0108000), Medical Support Program of the Jilin University (No. 20170311032YY), Science and Technology Project of the Jilin Provincial Department of Finance (No. jcsz2020304-9 and No. jsz2018170-12), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81970946). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tonetti MS, Jepsen S, Jin L, Otomo-Corgel J. Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: a call for global action. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(5):456–462. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler CJ, Dobney K, Weyrich LS, Kaidonis J, Walker AW, Haak W, et al. Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):450–5 5e1. doi: 10.1038/ng.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJL, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fi C, Wo W. Periodontal disease and systemic diseases: an overview on recent progresses. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2021;35(1 Suppl. 1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plachokova AS, Andreu-Sanchez S, Noz MP, Fu J, Riksen NP. Oral microbiome in relation to periodontitis severity and systemic inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5876. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(1):30–44. doi: 10.1038/nri3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Ruan J, Weir MD, Ren K, Schneider A, Wang P, et al. Periodontal bone-ligament-cementum regeneration via scaffolds and stem cells. Cells. 2019;8(6):537. doi: 10.3390/cells8060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanz M, Marco Del Castillo A, Jepsen S, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, D'Aiuto F, Bouchard P, et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: consensus report. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(3):268–288. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liccardo D, Cannavo A, Spagnuolo G, Ferrara N, Cittadini A, Rengo C, et al. Periodontal disease: a risk factor for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1414. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosshardt DD, Sculean A. Does periodontal tissue regeneration really work? Periodontol. 2000;2009(51):208–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mlachkova AM, Popova CL. Efficiency of nonsurgical periodontal therapy in moderate chronic periodontitis. Folia Med. 2014;56(2):109–115. doi: 10.2478/folmed-2014-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villar CC, Cochran DL. Regeneration of periodontal tissues: guided tissue regeneration. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54(1):73–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anitua E, Troya M, Orive G. An autologous platelet-rich plasma stimulates periodontal ligament regeneration. J Periodontol. 2013;84(11):1556–1566. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.120556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno H, Hata KI, Kojima K, Bonassar LJ, Vacanti CA, Ueda M. A novel approach to regenerating periodontal tissue by grafting autologous cultured periosteum. Tissue Eng Larchmont. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Howell TH, Fiorellini JP, Paquette DW, Offenbacher S, Giannobile WV, Lynch SE. A phase I/II clinical trial to evaluate a combination of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB and recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1997;68(12):1186–1193. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.12.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh Z, Hamdan N, Ikeda Y, Grynpas M, Ganss B, Glogauer M. Natural graft tissues and synthetic biomaterials for periodontal and alveolar bone reconstructive applications: a review. Biomater Res. 2017;21:9. doi: 10.1186/s40824-017-0095-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen FM, Zhang J, Zhang M, An Y, Chen F, Wu ZF. A review on endogenous regenerative technology in periodontal regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2010;31(31):7892–7927. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen FM, Jin Y. Periodontal tissue engineering and regeneration: current approaches and expanding opportunities. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16(2):219–255. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2009.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu XY, Li X, Wang J, He XT, Sun HH, Chen FM. Concise review: periodontal tissue regeneration using stem cells: strategies and translational considerations. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8(4):392–403. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YG, Choi J, Kim K. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for effective cartilage tissue repair and treatment of osteoarthritis. Biotechnol J. 2020;15(12):e2000082. doi: 10.1002/biot.202000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mareschi K, Ferrero I, Rustichelli D, Aschero S, Gammaitoni L, Aglietta M, et al. Expansion of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from pediatric and adult donor bone marrow. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97(4):744–754. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vishnubalaji R, Al-Nbaheen M, Kadalmani B, Aldahmash A, Ramesh T. Comparative investigation of the differentiation capability of bone-marrow- and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by qualitative and quantitative analysis. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347(2):419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsuno T, Ozaki T, Saka Y, Furuhashi K, Kim H, Yasuda K, et al. Low serum cultured adipose tissue-derived stromal cells ameliorate acute kidney injury in rats. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(2):287–297. doi: 10.3727/096368912X655019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J, Perez-Fernandez R. Mesenchymal stem cell secretome: toward cell-free therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9):1852. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura Y, Wang X, Xu C, Asakura A, Yoshiyama M, From AH, et al. Xenotransplantation of long-term-cultured swine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(3):612–620. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(4):392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phinney DG, Di Giuseppe M, Njah J, Sala E, Shiva S, St Croix CM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells use extracellular vesicles to outsource mitophagy and shuttle microRNAs. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8472. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Praveen Kumar L, Kandoi S, Misra R, Vijayalakshmi S, Rajagopal K, Verma RS. The mesenchymal stem cell secretome: a new paradigm towards cell-free therapeutic mode in regenerative medicine. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2019;46:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madrigal M, Rao KS, Riordan NH. A review of therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell secretions and induction of secretory modification by different culture methods. J Transl Med. 2014;12:260. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0260-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikbakht MR, Zarif MN, Oubari F, Mansouri K, Miri AT. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation: immunobiology, therapeutic applications and challenges—a review article. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2015;20(3):113–139. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawitan JA. Prospect of stem cell conditioned medium in regenerative medicine. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:965849. doi: 10.1155/2014/965849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovach TK, Dighe AS, Lobo PI, Cui Q. Interactions between MSCs and immune cells: implications for bone healing. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:752510. doi: 10.1155/2015/752510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tokhanbigli S, Baghaei K, Asadirad A, Hashemi SM, Asadzadeh-Aghdaei H, Zali MR. Immunoregulatory impact of human mesenchymal-conditioned media and mesenchymal derived exosomes on monocytes. Mol Biol Res Commun. 2019;8(2):79–89. doi: 10.22099/mbrc.2019.33346.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrell CR, Jankovic MG, Fellabaum C, Volarevic A, Djonov V, Arsenijevic A, et al. Molecular mechanisms responsible for anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived factors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1084:187–206. doi: 10.1007/5584_2018_306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan W, Wang Q, Chen Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11(3):30. doi: 10.1038/s41368-019-0064-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantovani A, Dinarello CA, Molgora M, Garlanda C. Interleukin-1 and related cytokines in the regulation of inflammation and immunity. Immunity. 2019;50(4):778–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stadler AF, Angst PD, Arce RM, Gomes SC, Oppermann RV, Susin C. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of cytokines/chemokines in chronic periodontitis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(9):727–745. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Algate K, Haynes DR, Bartold PM, Crotti TN, Cantley MD. The effects of tumour necrosis factor-alpha on bone cells involved in periodontal alveolar bone loss; osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes. J Periodontal Res. 2016;51(5):549–566. doi: 10.1111/jre.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sowmya S, Mony U, Jayachandran P, Reshma S, Kumar RA, Arzate H, et al. Tri-layered nanocomposite hydrogel scaffold for the concurrent regeneration of cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(7):1601251. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201601251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahajan A, Kedige S. Periodontal bone regeneration in intrabony defects using osteoconductive bone graft versus combination of osteoconductive and osteostimulative bone graft: a comparative study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12(1):25–30. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.150307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou M, Geng YM, Li SY, Yang XB, Che YJ, Pathak JL, et al. Nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite-based scaffold adsorbs and gives sustained release of osteoinductive growth factor and facilitates bone regeneration in mice ectopic model. J Nanomater. 2019;2019:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen M, Xu Y, Zhang T, Ma Y, Liu J, Yuan B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell sheets: a new cell-based strategy for bone repair and regeneration. Biotechnol Lett. 2019;41(3):305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10529-019-02649-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acar AH, Alan H, Özgür C, Vardi N, Asutay F, Güler Ç. Is more cortical bone decortication effective on guided bone augmentation? J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(7):1879–1883. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi H, Zong W, Xu X, Chen J. Improved biphasic calcium phosphate combined with periodontal ligament stem cells may serve as a promising method for periodontal regeneration. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10(12):4030–4041. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du J, Shan Z, Ma P, Wang S, Fan Z. Allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for periodontal regeneration. J Dent Res. 2014;93(2):183–188. doi: 10.1177/0022034513513026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bottino MC, Thomas V, Schmidt G, Vohra YK, Chu TM, Kowolik MJ, et al. Recent advances in the development of GTR/GBR membranes for periodontal regeneration—a materials perspective. Dent Mater. 2012;28(7):703–721. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arzate H, Zeichner-David M, Mercado-Celis G. Cementum proteins: role in cementogenesis, biomineralization, periodontium formation and regeneration. Periodontol 2000. 2015;67(1):211–233. doi: 10.1111/prd.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang ZH, Zhang XJ, Dang NN, Ma ZF, Xu L, Wu JJ, et al. Apical tooth germ cell-conditioned medium enhances the differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells into cementum/periodontal ligament-like tissues. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44(2):199–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daley GQ. Stem cells and the evolving notion of cellular identity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1680):20140376. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dulak J, Szade K, Szade A, Nowak W, Józkowicz A. Adult stem cells: hopes and hypes of regenerative medicine. Acta Biochim Pol. 2015;62(3):329–337. doi: 10.18388/abp.2015_1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, et al. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: the international society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7(5):393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galipeau J, Krampera M, Barrett J, Dazzi F, Deans RJ, DeBruijn J, et al. International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective on immune functional assays for mesenchymal stromal cells as potency release criterion for advanced phase clinical trials. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee YC, Chan YH, Hsieh SC, Lew WZ, Feng SW. Comparing the osteogenic potentials and bone regeneration capacities of bone marrow and dental pulp mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit calvarial bone defect model. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(20):5015. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Debnath S, Yallowitz AR, McCormick J, Lalani S, Zhang T, Xu R, et al. Discovery of a periosteal stem cell mediating intramembranous bone formation. Nature. 2018;562(7725):133–139. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0554-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang GT, Al-Habib M, Gauthier P. Challenges of stem cell-based pulp and dentin regeneration: a clinical perspective. Endod Topics. 2013;28(1):51–60. doi: 10.1111/etp.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Botelho J, Cavacas MA, Machado V, Mendes JJ. Dental stem cells: recent progresses in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Ann Med. 2017;49(8):644–651. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2017.1347705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomokiyo A, Wada N, Maeda H. Periodontal ligament stem cells: regenerative potency in periodontium. Stem Cells Dev. 2019;28(15):974–985. doi: 10.1089/scd.2019.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tatullo M, Marrelli M, Shakesheff KM, White LJ. Dental pulp stem cells: function, isolation and applications in regenerative medicine. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;9(11):1205–1216. doi: 10.1002/term.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomasello L, Mauceri R, Coppola A, Pitrone M, Pizzo G, Campisi G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from inflamed dental pulpal and gingival tissue: a potential application for bone formation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):179. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0633-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J, Ding H, Liu X, Sheng Y, Liu X, Jiang C. Dental follicle stem cells: tissue engineering and immunomodulation. Stem Cells Dev. 2019;28(15):986–994. doi: 10.1089/scd.2019.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meng X, Peng H, Ding Y, Zhang L, Yang J, Han X. A transcriptomic regulatory network among miRNAs, piRNAs, circRNAs, lncRNAs and mRNAs regulates microcystin-leucine arginine (MC-LR)-induced male reproductive toxicity. Sci Total Environ. 2019;667:563–577. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang GT, Gronthos S, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: their biology and role in regenerative medicine. J Dent Res. 2009;88(9):792–806. doi: 10.1177/0022034509340867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng C, Chen J, Liu S, Jin Y. Stem cell-based bone and dental regeneration: a view of microenvironmental modulation. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11(3):23. doi: 10.1038/s41368-019-0060-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharpe PT. Dental mesenchymal stem cells. Development. 2016;143(13):2273–2280. doi: 10.1242/dev.134189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Macrin D, Joseph JP, Pillai AA, Devi A. Eminent sources of adult mesenchymal stem cells and their therapeutic imminence. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2017;13(6):741–756. doi: 10.1007/s12015-017-9759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spees JL, Lee RH, Gregory CA. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell function. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(9):726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsu PJ, Liu KJ, Chao YY, Sytwu HK, Yen BL. Assessment of the immunomodulatory properties of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) J Vis Exp. 2015;106:e53265. doi: 10.3791/53265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pajarinen J, Lin T, Gibon E, Kohno Y, Maruyama M, Nathan K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-macrophage crosstalk and bone healing. Biomaterials. 2019;196:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park CH, Kim KH, Lee YM, Seol YJ. Advanced engineering strategies for periodontal complex regeneration. Materials (Basel). 2016;9(1):57. doi: 10.3390/ma9010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Herberts CA, Kwa MS, Hermsen HP. Risk factors in the development of stem cell therapy. J Transl Med. 2011;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wagers AJ. The stem cell niche in regenerative medicine. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(4):362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lane SW, Williams DA, Watt FM. Modulating the stem cell niche for tissue regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):795–803. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.von Bahr L, Batsis I, Moll G, Hagg M, Szakos A, Sundberg B, et al. Analysis of tissues following mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in humans indicates limited long-term engraftment and no ectopic tissue formation. Stem Cells. 2012;30(7):1575–1578. doi: 10.1002/stem.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sze SK, de Kleijn DP, Lai RC, Khia Way Tan E, Zhao H, Yeo KS, et al. Elucidating the secretion proteome of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(10):1680–1689. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600393-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bermudez MA, Sendon-Lago J, Eiro N, Trevino M, Gonzalez F, Yebra-Pimentel E, et al. Corneal epithelial wound healing and bactericidal effect of conditioned medium from human uterine cervical stem cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):983–992. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harrell CR, Jovicic N, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes and other extracellular vesicles as new remedies in the therapy of inflammatory diseases. Cells. 2019;8(12):1605. doi: 10.3390/cells8121605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ando Y, Matsubara K, Ishikawa J, Fujio M, Shohara R, Hibi H, et al. Stem cell-conditioned medium accelerates distraction osteogenesis through multiple regenerative mechanisms. Bone. 2014;61:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wittig O, Diaz-Solano D, Cardier J. Viability and functionality of mesenchymal stromal cells loaded on collagen microspheres and incorporated into plasma clots for orthopaedic application: effect of storage conditions. Injury. 2018;49(6):1052–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Squecco R, Tani A, Chellini F, Garella R, Idrizaj E, Rosa I, et al. Bone marrow-mesenchymal stromal cell secretome as conditioned medium relieves experimental skeletal muscle damage induced by ex vivo eccentric contraction. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3645. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakaguchi K, Katagiri W, Osugi M, Kawai T, Sugimura-Wakayama Y, Hibi H. Periodontal tissue regeneration using the cytokine cocktail mimicking secretomes in the conditioned media from human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;484(1):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kawai T, Katagiri W, Osugi M, Sugimura Y, Hibi H, Ueda M. Secretomes from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells enhance periodontal tissue regeneration. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(4):369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nagata M, Iwasaki K, Akazawa K, Komaki M, Yokoyama N, Izumi Y, et al. Conditioned medium from periodontal ligament stem cells enhances periodontal regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23(9–10):367–377. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qiu J, Wang X, Zhou H, Zhang C, Wang Y, Huang J, et al. Enhancement of periodontal tissue regeneration by conditioned media from gingiva-derived or periodontal ligament-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a comparative study in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1546-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen Y, Liu H. The differentiation potential of gingival mesenchymal stem cells induced by apical tooth germ cellconditioned medium. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(4):3565–3572. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mohammed E, Khalil E, Sabry D. Effect of adipose-derived stem cells and their exo as adjunctive therapy to nonsurgical periodontal treatment: a histologic and histomorphometric study in rats. Biomolecules. 2018;8(4):167. doi: 10.3390/biom8040167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jin Z, Feng Y, Liu H. Conditioned media from differentiating craniofacial bone marrow stromal cells influence mineralization and proliferation in periodontal ligament stem cells. Hum Cell. 2016;29(4):162–175. doi: 10.1007/s13577-016-0144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu N, Gu B, Liu N, Nie X, Zhang B, Zhou X, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates cementogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-deprived stem cells in dental follicle cell-conditioned medium. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e93364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim HS, Lee DS, Lee JH, Kang MS, Lee NR, Kim HJ, et al. The effect of odontoblast conditioned media and dentin non-collagenous proteins on the differentiation and mineralization of cementoblasts in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sawada K, Takedachi M, Yamamoto S, Morimoto C, Ozasa M, Iwayama T, et al. Trophic factors from adipose tissue-derived multi-lineage progenitor cells promote cytodifferentiation of periodontal ligament cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464(1):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Inukai T, Katagiri W, Yoshimi R, Osugi M, Kawai T, Hibi H, et al. Novel application of stem cell-derived factors for periodontal regeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430(2):763–768. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Katagiri W, Osugi M, Kawai T, Hibi H. First-in-human study and clinical case reports of the alveolar bone regeneration with the secretome from human mesenchymal stem cells. Head Face Med. 2016;12:5. doi: 10.1186/s13005-016-0101-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Katagiri W, Watanabe J, Toyama N, Osugi M, Sakaguchi K, Hibi H. Clinical study of bone regeneration by conditioned medium from mesenchymal stem cells after maxillary sinus floor elevation. Implant Dent. 2017;26(4):607–612. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.He F, Li L, Fan R, Wang X, Chen X, Xu Y. Extracellular vesicles: an emerging regenerative treatment for oral disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:669011. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.669011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gholami L, Nooshabadi VT, Shahabi S, Jazayeri M, Tarzemany R, Afsartala Z, et al. Extracellular vesicles in bone and periodontal regeneration: current and potential therapeutic applications. Cell Biosci. 2021;11(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00527-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sivaraj KK, Adams RH. Blood vessel formation and function in bone. Development. 2016;143(15):2706–2715. doi: 10.1242/dev.136861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Merckx G, Hosseinkhani B, Kuypers S, Deville S, Irobi J, Nelissen I, et al. Angiogenic effects of human dental pulp and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells and their extracellular vesicles. Cells. 2020;9(2):312. doi: 10.3390/cells9020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kusumbe AP, Ramasamy SK, Adams RH. Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature. 2014;507(7492):323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, Wang L, Adams RH. Endothelial Notch activity promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis in bone. Nature. 2014;507(7492):376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peng Y, Wu S, Li Y, Crane JL. Type H blood vessels in bone modeling and remodeling. Theranostics. 2020;10(1):426–436. doi: 10.7150/thno.34126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Katagiri W, Osugi M, Kinoshita K, Hibi H. Conditioned medium from mesenchymal stem cells enhances early bone regeneration after maxillary sinus floor elevation in rabbits. Implant Dent. 2015;24(6):657–663. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Delfi I, Wood CR, Johnson LDV, Snow MD, Innes JF, Myint P, et al. An in vitro comparison of the neurotrophic and angiogenic activity of human and canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): translating MSC-based therapies for spinal cord injury. Biomolecules. 2020;10(9):1301. doi: 10.3390/biom10091301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Katagiri W, Kawai T, Osugi M, Sugimura-Wakayama Y, Sakaguchi K, Kojima T, et al. Angiogenesis in newly regenerated bone by secretomes of human mesenchymal stem cells. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;39(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s40902-017-0106-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jin S, Yang C, Huang J, Liu L, Zhang Y, Li S, et al. Conditioned medium derived from FGF-2-modified GMSCs enhances migration and angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-1584-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhan J, Li Y, Yu J, Zhao Y, Cao W, Ma J, et al. Culture medium of bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells effects lymphatic endothelial cells and tumor lymph vessel formation. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1221–1226. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bussche L, Van de Walle GR. Peripheral blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells promote angiogenesis via paracrine stimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secretion in the equine model. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(12):1514–1525. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Burlacu A, Grigorescu G, Rosca AM, Preda MB, Simionescu M. Factors secreted by mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells have complementary effects on angiogenesis in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(4):643–653. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Heidari M, Pouya S, Baghaei K, Aghdaei HA, Namaki S, Zali MR, et al. The immunomodulatory effects of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells-conditioned medium in chronic colitis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(11):8754–8766. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chen B, Ni Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Yan F. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells exert diverse effects on different macrophage subsets. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:8348121. doi: 10.1155/2018/8348121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gao S, Mao F, Zhang B, Zhang L, Zhang X, Wang M, et al. Mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce macrophage M2 polarization through the nuclear factor-kappaB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathways. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2014;239(3):366–375. doi: 10.1177/1535370213518169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu J, Chen B, Bao J, Zhang Y, Lei L, Yan F. Macrophage polarization in periodontal ligament stem cells enhanced periodontal regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):320. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1409-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Su VY, Lin CS, Hung SC, Yang KY. Mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium induces neutrophil apoptosis associated with inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway in endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2208. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li Y, Gao X, Wang J. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned media suppresses inflammatory bone loss in a lipopolysaccharide-induced murine model. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(2):1839–1846. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Figueredo CM, Lira-Junior R, Love RM. T and B cells in periodontal disease: new functions in a complex scenario. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(16):3949. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Seo Y, Shin TH, Kim HS. Current strategies to enhance adipose stem cell function: an update. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3827. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yu X, Li Z, Wan Q, Cheng X, Zhang J, Pathak JL, et al. Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 signaling suppresses bone marrow stromal cells proliferation and osteogenic differentiation, and impairs bone defect healing. Biol Chem. 2018;399(11):1313–1323. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gnecchi M, Danieli P, Malpasso G, Ciuffreda MC. Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cells in tissue repair. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1416:123–146. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3584-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Harman RM, He MK, Zhang S, VanDeWalle GR. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and tenascin-C secreted by equine mesenchymal stromal cells stimulate dermal fibroblast migration in vitro and contribute to wound healing in vivo. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(8):1061–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sumi K, Abe T, Kunimatsu R, Oki N, Tsuka Y, Awada T, et al. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells on chemotaxis of osteoclast precursor cells. J Oral Sci. 2018;60(2):221–225. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.17-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Robering JW, Weigand A, Pfuhlmann R, Horch RE, Beier JP, Boos AM. Mesenchymal stem cells promote lymphangiogenic properties of lymphatic endothelial cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:2740. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Burja B, Barlic A, Erman A, Mrak-Poljsak K, Tomsic M, Sodin-Semrl S, et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells from different tissues exhibit unique responses to different inflammatory stimuli. Curr Res Transl Med. 2020;68(4):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.retram.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Xia Y, Tang HN, Wu RX, Yu Y, Gao LN, Chen FM. Cell responses to conditioned media produced by patient-matched stem cells derived from healthy and inflamed periodontal ligament tissues. J Periodontol. 2016;87(5):e53–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yang Z, Jin F, Zhang X, Ma D, Han C, Huo N, et al. Tissue engineering of cementum/periodontal-ligament complex using a novel three-dimensional pellet cultivation system for human periodontal ligament stem cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;15(4):571–581. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kang H, Lee MJ, Park SJ, Lee MS. Lipopolysaccharide-preconditioned periodontal ligament stem cells induce M1 polarization of macrophages through extracellular vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3843. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lee JK, Jin HK, Endo S, Schuchman EH, Carter JE, Bae JS. Intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduces amyloid-beta deposition and rescues memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease mice by modulation of immune responses. Stem Cells. 2010;28(2):329–343. doi: 10.1002/stem.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Katagiri W, Osugi M, Kawai T, Ueda M. Novel cell-free regeneration of bone using stem cell-derived growth factors. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2013;28(4):1009–1016. doi: 10.11607/jomi.3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Osugi M, Katagiri W, Yoshimi R, Inukai T, Hibi H, Ueda M. Conditioned media from mesenchymal stem cells enhanced bone regeneration in rat calvarial bone defects. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18(13–14):1479–1489. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.